Labor history of the United States

Encyclopedia

Corporation

A corporation is created under the laws of a state as a separate legal entity that has privileges and liabilities that are distinct from those of its members. There are many different forms of corporations, most of which are used to conduct business. Early corporations were established by charter...

, efforts by employers and private agencies to limit

Union busting

Union busting is a wide range of activities undertaken by employers, their proxies, and governments, which attempt to prevent the formation or expansion of trade unions...

or control

Labor spies

Labor spies are persons recruited or employed for the purpose of gathering intelligence, committing sabotage, sowing dissent, or engaging in other similar activities, typically within the context of an employer/labor organization relationship....

unions

Trade union

A trade union, trades union or labor union is an organization of workers that have banded together to achieve common goals such as better working conditions. The trade union, through its leadership, bargains with the employer on behalf of union members and negotiates labour contracts with...

, and U.S. labor law. As a response, organized unions and labor federations have competed, evolved, merged, and split against a backdrop of changing social philosophies

Social philosophy

Social philosophy is the philosophical study of questions about social behavior . Social philosophy addresses a wide range of subjects, from individual meanings to legitimacy of laws, from the social contract to criteria for revolution, from the functions of everyday actions to the effects of...

and periodic federal

Federal government of the United States

The federal government of the United States is the national government of the constitutional republic of fifty states that is the United States of America. The federal government comprises three distinct branches of government: a legislative, an executive and a judiciary. These branches and...

intervention. As commentator E. J. Dionne

E. J. Dionne

Eugene Joseph "E.J." Dionne, Jr. is an American journalist and political commentator, and a long-time op-ed columnist for The Washington Post...

has noted, the union movement has traditionally espoused a set of values—solidarity being the most important, the sense that each should look out for the interests of all. From this followed commitments to mutual assistance, to a rough-and-ready sense of equality, to a disdain for elitism, and to a belief that democracy and individual rights did not stop at the plant gate or the office reception room. Dionne notes that these values are "increasingly foreign to American culture".

The history of organized labor

Labor history (discipline)

Labor history is a broad field of study concerned with the development of the labor movement and the working class. The central concerns of labor historians include the development of labor unions, strikes, lockouts and protest movements, industrial relations, and the progress of working class and...

has been a specialty of scholars

Labour economics

Labor economics seeks to understand the functioning and dynamics of the market for labor. Labor markets function through the interaction of workers and employers...

since the 1890s, and has produced a large amount of scholarly literature. In the 1960s, as social history

Social history

Social history, often called the new social history, is a branch of History that includes history of ordinary people and their strategies of coping with life. In its "golden age" it was a major growth field in the 1960s and 1970s among scholars, and still is well represented in history departments...

gained popularity, a new emphasis emerged on the history of workers, with special regard to gender

Gender studies

Gender studies is a field of interdisciplinary study which analyses race, ethnicity, sexuality and location.Gender study has many different forms. One view exposed by the philosopher Simone de Beauvoir said: "One is not born a woman, one becomes one"...

and race. This is called "the new labor history

New labor history

New labor history is a branch of labor history which focuses on the experiences of workers, women, and minorities in the study of history. It is heavily influenced by social history....

". Much scholarship has attempted to bring the social history perspectives into the study of organized labor.

Early unions

The first local trade unionTrade union

A trade union, trades union or labor union is an organization of workers that have banded together to achieve common goals such as better working conditions. The trade union, through its leadership, bargains with the employer on behalf of union members and negotiates labour contracts with...

s of men in the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

formed in the late 18th century, and women began organizing in the 1820s. However, the movement came into its own after the Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, when the short-lived National Labor Union

National Labor Union

The National Labor Union was the first national labor federation in the United States. Founded in 1866 and dissolved in 1873, it paved the way for other organizations, such as the Knights of Labor and the AF of L . It was led by William H...

(NLU) became the first federation of American unions.

Women working under sweat shop conditions organized the first union in the early 19th century. According to the book American Labor, in 1834–1836 women worked 16–17 hours a day to earn $1.25 to $2.00 a week. A girl weaver in a non-union mill would receive $4.20 a week versus $12.00 for the same work in a union mill. The workers had to buy their own needles and thread from the proprietor. They were fined for being a few minutes late for work. Women carried their own foot treadle machines or were held in the shops until the entire shop had completed an immediate delivery order. Their pay was often shorted, but a protest might result in immediate dismissal. Sometimes whole families worked from sun up to midnight. Pulmonary ailments were common due to dust accumulation on the floors and tables. Some shops had leaks or openings in the roofs, and workers worked in inclement weather.

Despite the odds, some women challenged the employers. Their first organization was as an auxiliary, the Daughters of Liberty in 1765. In 1825, the women organized and called themselves the United Tailoresses of New York. Strikes occurred over the years, and some were successful.

Lowell, Massachusetts

Some of the earliest organizing by women occurred in Lowell, MassachusettsLowell, Massachusetts

Lowell is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, USA. According to the 2010 census, the city's population was 106,519. It is the fourth largest city in the state. Lowell and Cambridge are the county seats of Middlesex County...

. In 1845, the trade union of the Lowell mills

Lowell mills

Francis Cabot Lowell invented the first factory system "where people and machines were all under one roof." Also, a series of mills and factories were built along the Merrimack River by the Boston Manufacturing Company, an organization founded in years prior by the man for whom the resulting city...

sent representatives to speak to the Massachusetts legislature about conditions in the factories, leading to the first governmental investigation into working conditions. The mill strikes of 1834 and 1836, while largely unsuccessful, involved upwards of 2,000 workers and represented a substantial organizational effort.

National Labor Union

The National Labor Union (NLU), founded in 1866, was the first national labor federation in the United States. It was dissolved in 1872.Order of the Knights of St. Crispin

The regional Order of the Knights of St. Crispin was founded in the northeast in 1867 and claimed 50,000 members by 1870, by far the largest union in the country. A closely associated union of women, the Daughters of St. CrispinDaughters of St. Crispin

The Daughters of St. Crispin was an American labor union of women shoemakers, and the first national women's labor union in the United States.The union began with a strike of over a thousand female workers in 1860 in Massachusetts. By the end of 1869, it had a total of 24 local lodges across the...

, formed in 1870. In 1879 the Knights formally admitted women, who by 1886 comprised 10% of the union's membership, but it was poorly organized and soon declined. They fought encroachments of machinery and unskilled labor on autonomy of skilled shoe workers. One provision in the Crispin constitution explicitly sought to limit the entry of "green hands" into the trade, but this failed because the new machines could be operated by semi-skilled workers and produce more shoes than hand sewing.

Railroad brotherhoods

With the rapid growth and consolidation of large railroad systems after 1870, union organizations sprang up, covering the entire nation. By 1901, 17 major railway brotherhoods were in operation; they generally worked amicably with management, which recognized their usefulness. Key unions included the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers (BLE), the Order of Railway Conductors, the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, and the Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen. Their main goal was building insurance and medical packages for their members, and negotiating bureaucratic work rules that favored their membership, such as seniority and grievance procedures. They were not members of the AFL, and fought off more radical rivals such as the Knights of LaborKnights of Labor

The Knights of Labor was the largest and one of the most important American labor organizations of the 1880s. Its most important leader was Terence Powderly...

in the 1880s and the American Railroad Union in the 1890s. They consolidated their power in 1916, after threatening a national strike, by securing the Adamson Act

Adamson Act

The Adamson Act was a United States federal law passed in 1916 that established an eight-hour workday, with additional pay for overtime work, for interstate railroad workers....

, a federal law that provided 10 hours pay for an eight hour day. At the end World War I, they promoted nationalization of the railroads, and conducted a national strike in 1919. Both programs failed, and the brotherhoods were largely stagnant in the 1920s. They generally were independent politically, but supported the third party campaign of Robert LaFollette

Robert M. La Follette, Sr.

Robert Marion "Fighting Bob" La Follette, Sr. , was an American Republican politician. He served as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, was the Governor of Wisconsin, and was also a U.S. Senator from Wisconsin...

in 1924.

Knights of Labor

The first effective labor organization that was more than regional in membership and influence was the Knights of Labor, organized in 1869. The Knights believed in the unity of the interests of all producing groups and sought to enlist in their ranks not only all laborers but everyone who could be truly classified as a producer. The acceptance of all producers led to explosive growth after 1880. Under the leadership of Terence PowderlyTerence V. Powderly

Terence Vincent "Terry" Powderly was born in Carbondale, Pennsylvania, the son of Irish Catholic immigrants. He was a highly visible national spokesman for the working man as head of the Knights of Labor from 1879 until 1893...

they championed a variety of causes, sometimes through political or cooperative

Cooperative

A cooperative is a business organization owned and operated by a group of individuals for their mutual benefit...

ventures. Powderly hoped to gain their ends through politics and education rather than through economic coercion. The Knights were especially successful in developing a working class culture, involving women, families, sports, and leisure activities and educational projects for the membership. The Knights strongly promoted their version of republicanism

Republicanism in the United States

Republicanism is the political value system that has been a major part of American civic thought since the American Revolution. It stresses liberty and inalienable rights as central values, makes the people as a whole sovereign, supports activist government to promote the common good, rejects...

that stressed the centrality of free labor, preaching harmony and cooperation among producers, as opposed to parasites and speculators.

One of the earliest railroad strikes was also one of the most successful. In 1885, the Knights of Labor led railroad workers to victory against Jay Gould

Jay Gould

Jason "Jay" Gould was a leading American railroad developer and speculator. He has long been vilified as an archetypal robber baron, whose successes made him the ninth richest American in history. Condé Nast Portfolio ranked Gould as the 8th worst American CEO of all time...

and his entire Southwestern Railway system. In early 1886, the Knights were trying to coordinate 1400 strikes involving over 600,000 workers spread over much of the country. The tempo had doubled over 1885, and involved peaceful as well as violent confrontations in many sectors, such as railroads, street railroads, coal mining, and the McCormick Reaper Factory in Chicago, with demands usually focused on the eight hour day. Suddenly, it all collapsed, largely because the Knights were unable to handle so much on their plate at once, and because they took a smashing blow in the aftermath of the Haymarket Riot in May 1886 in Chicago. As strikers rallied against the McCormick plant, a team of political anarchists, who were not Knights, tried to piggyback support among striking Knights workers. A bomb exploded as police were dispersing a peaceful rally, killing seven policemen and wounding many others. The anarchists were blamed, and their spectacular trial gained national attention. The Knights of Labor were seriously injured by the false accusation that the Knights promoted anarchistic violence. Many Knights locals transferred to the less radical and more respectable AFL unions or railroad brotherhoods.

American Federation of Labor

The Federation of Organized Trades and Labor UnionsFederation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions

The Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions of the United States and Canada was a federation of labor unions created on November 15, 1881, in Pittsburgh...

began in 1881 under the leadership of Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers was an English-born American cigar maker who became a labor union leader and a key figure in American labor history. Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor , and served as that organization's president from 1886 to 1894 and from 1895 until his death in 1924...

. Like the National Labor Union

National Labor Union

The National Labor Union was the first national labor federation in the United States. Founded in 1866 and dissolved in 1873, it paved the way for other organizations, such as the Knights of Labor and the AF of L . It was led by William H...

, it was a federation of different unions and did not directly enroll workers. Its original goals were to encourage the formation of trade unions and to obtain legislation, such as prohibition of child labor, a national eight hour day, and exclusion of foreign contract workers. The Federation made some efforts to obtain favorable legislation, but had little success in organizing or chartering new unions. It came out in support of the proposal, traditionally attributed to Peter J. McGuire of the Carpenters Union, for a national Labor Day holiday on the first Monday in September, and threw itself behind the eight hour movement, which sought to limit the workday by either legislation or union organizing.

In 1886, as the relations between the trade union movement and the Knights of Labor worsened, McGuire and other union leaders called for a convention to be held at Columbus, Ohio on December 8. The Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions merged with the new organization, known as the American Federation of Labor or AFL, formed at that convention.

The AFL was formed in large part because of the dissatisfaction of many trade union leaders with the Knights of Labor, an organization that contained many trade unions and that had played a leading role in some of the largest strikes of the era. The new AFL distinguished itself from the Knights by emphasizing the autonomy of each trade union affiliated with it and limiting membership to workers and organizations made up of workers, unlike the Knights which, because of its producerist focus, welcomed some who were not wage workers.

The AFL grew steadily in the late 19th century while the Knights all but disappeared. Although Gompers at first advocated something like industrial unionism

Industrial unionism

Industrial unionism is a labor union organizing method through which all workers in the same industry are organized into the same union—regardless of skill or trade—thus giving workers in one industry, or in all industries, more leverage in bargaining and in strike situations...

, he retreated from that in the face of opposition from the craft unions

Craft unionism

Craft unionism refers to organizing a union in a manner that seeks to unify workers in a particular industry along the lines of the particular craft or trade that they work in by class or skill level...

that made up most of the AFL.

The unions of the AFL were composed primarily of skilled men; unskilled workers, African-Americans, and women were generally excluded. The AFL saw women as threatening the jobs of men, since they often worked for lower wages. The AFL provided little to no support for women's attempts to unionize.

Western Federation of Miners

The Western Federation of Miners (WFM) was created in 1893. Frequently in competition with the American Federation of Labor, the WFM spawned several new federations, including the Western Labor UnionWestern Labor Union

The Western Labor Union was a labor federation created by the Western Federation of Miners after the disastrous Leadville strike of 1896-97. The WLU was conceived in November, 1897 in a proclamation of the State Trades and Labor Council of Montana, and gained support from the WFM's executive...

, the American Labor Union

American Labor Union

When the Western Labor Union , a labor federation formed by the Western Federation of Miners, decided to overtly challenge the American Federation of Labor in 1902, it changed its name to the American Labor Union . The ALU was created because the WFM wanted a class-wide labor body with which to...

, and the Industrial Workers of the World

Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World is an international union. At its peak in 1923, the organization claimed some 100,000 members in good standing, and could marshal the support of perhaps 300,000 workers. Its membership declined dramatically after a 1924 split brought on by internal conflict...

(IWW). The WFM took a conservative turn in the aftermath of the Colorado Labor Wars

Colorado Labor Wars

Colorado's most significant battles between labor and capital occurred primarily between miners and mine operators. In these battles the state government, with one clear exception, always took the side of the mine operators....

and the trials of its president, Charles Moyer

Charles Moyer

Charles Moyer was an American labor leader and president of the Western Federation of Miners from 1902 to 1926. He led the union through the Colorado Labor Wars, was kidnapped and accused of murdering an ex-governor of the state of Idaho, and shot in the back during a bitter copper mine strike...

, and its secretary treasurer, Big Bill Haywood, for the conspiratorial assassination of Idaho's former governor. Although both were found innocent, the WFM, headed by Moyer, separated itself from the IWW, which was launched by Haywood and other labor radicals, socialist, and anarchists, just a few years after that organization's founding convention

First Convention of the Industrial Workers of the World

When Bill Haywood used a board to gavel to order the first convention of the Industrial Workers of the World , he announced, "this is the Continental Congress of the working class...

. In 1916 the WFM became the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers, which was eventually absorbed by the United Steelworkers of America.

Pullman Strike

During the major economic depression of the early 1890s, the Pullman Palace Car Company cut wages in its factories. Discontented workers joined the American Railway UnionAmerican Railway Union

The American Railway Union , was the largest labor union of its time, and one of the first industrial unions in the United States. It was founded on June 20, 1893, by railway workers gathered in Chicago, Illinois, and under the leadership of Eugene V...

(ARU), led by Eugene V. Debs

Eugene V. Debs

Eugene Victor Debs was an American union leader, one of the founding members of the International Labor Union and the Industrial Workers of the World , and several times the candidate of the Socialist Party of America for President of the United States...

, which supported their strike by launching a boycott of all Pullman cars on all railroads. ARU members across the nation refused to switch Pullman cars onto trains. When these switchmen were disciplined, the entire ARU struck the railroads on June 26, 1894. Within four days, 125,000 workers on twenty-nine railroads had quit work rather than handle Pullman cars.

The railroads were able to get Edwin Walker, general counsel for the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railway, appointed as a special federal attorney with responsibility for dealing with the strike. Walker went to federal court and obtained an injunction barring union leaders from supporting the boycott in any way. The court injunction was based on the Sherman Anti-Trust Act which prohibited "Every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States". Debs and other leaders of the ARU ignored the injunction, and federal troops were called into action.

The strike was broken up by United States Marshals and some 2,000 United States Army

United States Army

The United States Army is the main branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for land-based military operations. It is the largest and oldest established branch of the U.S. military, and is one of seven U.S. uniformed services...

troops, commanded by Nelson Miles, sent in by President Grover Cleveland

Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States. Cleveland is the only president to serve two non-consecutive terms and therefore is the only individual to be counted twice in the numbering of the presidents...

on the premise that the strike interfered with the delivery of U.S. Mail

United States Postal Service

The United States Postal Service is an independent agency of the United States government responsible for providing postal service in the United States...

. During the course of the strike, 13 strikers were killed and 57 were wounded. An estimated $340,000 worth of property damage occurred during the strike. Debs went to prison for six months for violating the federal court order, and the ARU disintegrated.

Organized labor 1900–1920

From 1890 to 1914 the unionized wages in manufacturing rose from $17.63 a week to $21.37, and the average work week fell from 54.4 to 48.8 hours a week. The pay for all factory workers was $11.94 and $15.84 because unions reached only the more skilled factory workers.Coal strikes, 1900–1902

The United Mine Workers was successful in its strike against soft coal (bituminous) mines in the Midwest in 1900, but its strike against the hard coal (anthracite) mines of Pennsylvania turned into a national political crisis in 1902. President Theodore RooseveltTheodore Roosevelt

Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt was the 26th President of the United States . He is noted for his exuberant personality, range of interests and achievements, and his leadership of the Progressive Movement, as well as his "cowboy" persona and robust masculinity...

brokered a compromise solution that kept the flow of coal going, and higher wages and shorter hours, but did not include recognition of the union as a bargaining agent.

Women's Trade Union League

The Women's Trade Union LeagueWomen's Trade Union League

The Women's Trade Union League was a U.S. organization of both working class and more well-off women formed in 1903 to support the efforts of women to organize labor unions and to eliminate sweatshop conditions...

was a support group that did not organize locals. It formed at the 1903 AFL convention in Boston and was loosely tied to the AFL. It was composed of both workingwomen and middle-class reformers, and provided financial assistance, moral support, and training in work skills and social refinement for blue collar women. Most active in 1907–1922 under Margaret Dreier Robins

Margaret Dreier Robins

Margaret Dreier Robins was an American labor leader. Born in Brooklyn to prosperous German immigrants in 1868, in her teens Robins suffered from physical ailments which left her depressed and weak. She was privately educated. At age nineteen, she began doing charity work at Brooklyn Hospital and...

, it publicized the cause and lobbied for minimum wages and restrictions on hours of work and child labor.

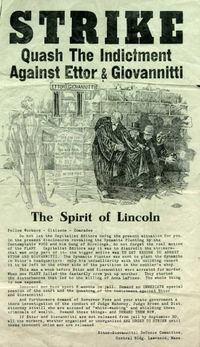

Industrial Workers of the World

Bill Haywood

William Dudley Haywood , better known as "Big Bill" Haywood, was a founding member and leader of the Industrial Workers of the World , and a member of the Executive Committee of the Socialist Party of America...

. The IWW pioneered creative tactics, and organized along the lines of industrial unionism

Industrial unionism

Industrial unionism is a labor union organizing method through which all workers in the same industry are organized into the same union—regardless of skill or trade—thus giving workers in one industry, or in all industries, more leverage in bargaining and in strike situations...

rather than craft unionism; in fact, they went even further, pursuing the goal of "One Big Union" and the abolition of the wage system. Many, though not all, Wobblies favored anarcho-syndicalism

Anarcho-syndicalism

Anarcho-syndicalism is a branch of anarchism which focuses on the labour movement. The word syndicalism comes from the French word syndicat which means trade union , from the Latin word syndicus which in turn comes from the Greek word σύνδικος which means caretaker of an issue...

. Much of the IWW's organizing took place in the West, and most of its early members were miners, lumbermen, cannery, and dock workers. In 1912 the IWW organized a strike of more than twenty thousand textile workers

Lawrence textile strike

The Lawrence Textile Strike was a strike of immigrant workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts in 1912 led by the Industrial Workers of the World. Prompted by one mill owner's decision to lower wages when a new law shortening the workweek went into effect in January, the strike spread rapidly through the...

, and by 1917 the Agricultural Worker's Organization (AWO) of the IWW claimed a hundred thousand itinerant farm workers in the heartland of North America. Eventually the concept of One Big Union spread from dock workers to maritime workers, and thus was communicated to many different parts of the world. Dedicated to workplace

Workplace democracy

Workplace democracy is the application of democracy in all its forms to the workplace....

and economic democracy

Economic democracy

Economic democracy is a socioeconomic philosophy that suggests a shift in decision-making power from a small minority of corporate shareholders to a larger majority of public stakeholders...

, the IWW allowed men and women as members, and organized workers of all races and nationalities, without regard to current employment status. At its peak it had 150,000 members (with 200,000 membership cards issued between 1905 and 1916), but it was fiercely repressed during, and especially after, World War I with many of its members killed, about 10,000 organizers imprisoned, and thousands more deported as foreign agitators. The IWW proved that unskilled workers could be organized and gave unskilled workers a sense of dignity and self-worth. The IWW exists today with about 2,000 members, but its most significant impact was during its first two decades of existence.

Government and labor

In 1908 the U.S. Supreme Court decided Loewe v. LawlorLoewe v. Lawlor

Loewe v. Lawlor, is a United States Supreme Court case concerning the application of antitrust laws to labor unions. The Court's decision had the effect of outlawing secondary boycotts as violative of the Sherman Antitrust Act, in the face of labor union protests that their actions affected only...

(the Danbury Hatters' Case). In 1902 the Hatters' Union instituted a nationwide boycott of the hats made by a nonunion company in Connecticut. Owner Dietrich Loewe brought suit against the union for unlawful combinations to restrain trade in violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act

Sherman Antitrust Act

The Sherman Antitrust Act requires the United States federal government to investigate and pursue trusts, companies, and organizations suspected of violating the Act. It was the first Federal statute to limit cartels and monopolies, and today still forms the basis for most antitrust litigation by...

. The Court ruled that the union was subject to an injunction and liable for the payment of triple damages. In 1915 Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1902 to 1932...

, speaking for the Court, again decided in favor of Loewe, upholding a lower federal court ruling ordering the union to pay damages of $252,130. (The cost of lawyers had already exceeded $100,000, paid by the AFL). This was not a typical case in which a few union leaders were punished with short terms in jail; specifically, the life savings of several hundreds of the members were attached. The lower court ruling established a major precedent, and became a serious issue for the unions. The Clayton Act of 1914

Clayton Antitrust Act

The Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914 , was enacted in the United States to add further substance to the U.S. antitrust law regime by seeking to prevent anticompetitive practices in their incipiency. That regime started with the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, the first Federal law outlawing practices...

presumably exempted unions from the antitrust prohibition and established for the first time the Congressional principle that "the labor of a human being is not a commodity or article of commerce." However, judicial interpretation so weakened it that prosecutions of labor under the antitrust acts continued until the enactment of the Norris-La Guardia Act in 1932.

- Loewe v. LawlorLoewe v. LawlorLoewe v. Lawlor, is a United States Supreme Court case concerning the application of antitrust laws to labor unions. The Court's decision had the effect of outlawing secondary boycotts as violative of the Sherman Antitrust Act, in the face of labor union protests that their actions affected only...

, 208 U.S. 274 (1908), 235 U.S. 522 (1915)

State legislation 1912–1918: 36 states adopted the principle of workmen's compensation for all industrial accidents. Also: prohibition of the use of an industrial poison, several states require one day's rest in seven, the beginning of effective prohibition of night work, of maximum limits upon the length of the working day, and of minimum wage laws for women.

Railroad brotherhoods

The Great Railroad Strike of 1922Great Railroad Strike of 1922

The Great Railroad Strike of 1922 was a nationwide railroad shop workers strike in the United States. The action began on July 1 and was the largest railroad work stoppage since 1894.-History:...

, a nationwide railroad shop workers strike, began on July 1. The immediate cause of the strike was the Railroad Labor Board's announcement that hourly wages would be cut by seven cents on July 1, which prompted a shop workers vote on whether or not to strike. The operators' union did not join in the strike, and the railroads employed strikebreakers to fill three-fourths of the roughly 400,000 vacated positions, increasing hostilities between the railroads and the striking workers. On September 1, a federal judge issued the sweeping "Daugherty Injunction" against striking, assembling, and picketing. Unions bitterly resented the injunction; a few sympathy strikes shut down some railroads completely. The strike eventually died out as many shopmen made deals with the railroads on the local level. The often unpalatable concessions — coupled with memories of the violence and tension during the strike — soured relations between the railroads and the shopmen for years.

World War I

During World War I Gompers and the AFL were strong supporters of the war effort. They minimized strikes as wages soared and full employment was reached. The AFL unions strongly encouraged their young men to enlist in the military, and fiercely opposed efforts to reduce recruiting and slow war production by the anti-war IWW and left-wing Socialists. President Wilson appointed Gompers to the powerful Council of National DefenseCouncil of National Defense

The Council of National Defense was a United States organization formed during World War I to coordinate resources and industry in support of the war effort, including the coordination of transportation, industrial and farm production, financial support for the war, and public...

, where he set up the War Committee on Labor.

The AFL membership reached 2.4 million in 1917.

Boston Telephone Strike of 1919

Moved to action by the rising cost of living, the president of the Boston Telephone Operator's Union, Julia O'Connor, proposed a new wage scale to the general manager of the New England TelephoneNew England Telephone

The New England Telephone and Telegraph Company, more commonly known as New England Telephone, was a Bell Operating Company that served most of the New England area of the United States as a part of the original AT&T for seven decades, from the creation of the national monopoly in 1907 until...

Company, William E. Driver. While telephone rates had increased, the rates of telephone operators averaged half that of a government clerk and "65 percent of the average for a female worker in manufacturing". When Driver rejected the new wage scale on April 11, 1919, due to lack of governmental permission, the union ordered a strike to begin on April 15. Not only did the 6,000 Boston operators and union members walk out, but over 3,000 operators in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Maine, Vermont, and Rhode Island walked out as well. The strike effectively shut down all the telephone service in New England

New England

New England is a region in the northeastern corner of the United States consisting of the six states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut...

. In a show of unity, most of the male union members working in the plant department also struck on behalf of the operators. In response, the New England Telephone Company collaborated with Harvard University

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States, established in 1636 by the Massachusetts legislature. Harvard is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States and the first corporation chartered in the country...

and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology is a private research university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts. MIT has five schools and one college, containing a total of 32 academic departments, with a strong emphasis on scientific and technological education and research.Founded in 1861 in...

to employ college students as strikebreakers. The students were not welcomed by the strikers and were attacked upon arrival. The Cooks and Waiters Union also supported the striking operators by refusing to serve the injured strikebreakers who were taken to local hotels for food. On April 20, an agreement was reached by strikers and company officials to accept the proposed wage raises. The men who struck out of sympathy for the female operators also received a 30 cent a day increase. After the strike, Julia O'Connor began a tour organizing women operators nationwide. Her tour resulted in settlements "on the Pacific Coast, in the South, and in the Midwest ... modeled after the New England Agreement".

Coal Strike of 1919

The United Mine WorkersUnited Mine Workers

The United Mine Workers of America is a North American labor union best known for representing coal miners and coal technicians. Today, the Union also represents health care workers, truck drivers, manufacturing workers and public employees in the United States and Canada...

under John L. Lewis

John L. Lewis

John Llewellyn Lewis was an American leader of organized labor who served as president of the United Mine Workers of America from 1920 to 1960...

announced a strike for November 1, 1919. They had agreed to a wage agreement to run until the end of World War I and now sought to capture some of their industry's wartime gains. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer invoked the Lever Act

Food and Fuel Control Act

The Food and Fuel Control Act, , also called the Lever Act or the Lever Food Act was a World War I era US law that among other things created the United States Food Administration and the Federal Fuel Administration.-Legislative history:...

, a wartime measure that made it a crime to interfere with the production or transportation of necessities. The law, meant to punish hoarding and profiteering, had never been used against a union. Certain of united political backing and with the perception of public support, Palmer obtained an injunction on October 31 and 400,000 coal workers struck the next day.

Gompers as head of the AFL at first attempted to mediate between Palmer and Lewis, but after several days called the injunction "so autocratic as to stagger the human mind". The coal operators smeared the strikers with charges that Lenin and Trotsky had ordered the strike and were financing it, and some of the press echoed that language. Others used words like "insurrection" and "Bolshevik revolution". Eventually Lewis, facing criminal charges and sensitive to the propaganda campaign, withdrew his strike call, though many strikers ignored his action. As the strike dragged on into its third week, coal supplies were running low and public sentiment was calling for ever stronger government action. Final agreement came on December 10.

Organized labor 1920–1929

The 1920s1920s

File:1920s decade montage.png|From left, clockwise: Third Tipperary Brigade Flying Column No. 2 under Sean Hogan during the Irish Civil War; Prohibition agents destroying barrels of alcohol in accordance to the 18th amendment, which made alcoholic beverages illegal throughout the entire decade; In...

marked a period of decline for the labor movement. In 1919, more than 4 million workers (or 21 percent of the labor force) participated in about 3,600 strikes. In contrast, 1929 witnessed about 289,000 workers (or 1.2 percent of the labor force) stage only 900 strikes. Union membership and activities fell sharply in the face of economic prosperity, a lack of leadership within the movement, and anti-union sentiments from both employers and the government.

However, among the Filipino farm worker population in California there was a noticeable increase in unionizing activities prompted by a decline in wages, and in the face of increasing hostility against immigrant workers organizing for improved living conditions. In the 1920s, anti-Filipino sentiment was fueled by the California Department of Industrial Relations statistician Louis Bloch, publisher of a bulletin on Filipino immigration into California. Additionally, Will J. French, the director of the California Department of Industrial Relations, supported the report, to which he wrote an introduction, describing a "third wave of Filipino immigration", the rapidity of which he characterized as being too great. French also implied the wrong kind of Filipinos were coming in. This heavily influenced the American Federation of Labor, which expounded upon anti-Filipino sentiment in equating Filipinos with the increase of "ethnic" labor, associated with declining field wages and increasing strikes. In this way, the traditional labor unions framed Filipino organizing attempts as detrimental to white workers' wages.

The authorities and other whites often harassed Filipinos when they attempted to leave their segregated neighborhoods, and this created significant tension and resentment among the primarily male Filipino community, whose members regarded themselves as Americans' equals, but who were regarded as threats to white females and who were rarely valued for anything outside of farm and other menial labor. Filipinos possessed a very sophisticated sense of organizing and once they dominated a labor market would immediately begin negotiating for improved living conditions and wages, which created resentment and fear among whites in regard to wage control and concerns about wage devaluation for them – concerns the traditional labor unions pandered to. The stereotyping of Filipinos into farm labor, coupled with authoritarian attempts by law enforcement and the Associated Farmers – (who represented agri-business) - to terrorize and contain Filipinos created much hatred, conflicts, and occasional race riots, and it intensified Filipino determination to unionize – something they regarded as the only effective means of counteracting racism and exploitation.

One of the earliest Filipino labor strikes by Sons of the Farm occurred in 1928, and forced wage increases and better living conditions. Because Filipinos were rejected by traditional labor unions, they had to form their own unions. They formed seven different unions, a number of which were formed in response to "agricultural violence". Additionally, the Filipino Labor Union was the only one to strike effectively in the fields of California in the early 1930s. There were sporadic wildcat strikes from 1924 to 1927 and when wages dropped enormously due to the Depression in 1929, Filipino union activism noticeably increased, according to DeWitt.

Economic prosperity and a lack of leadership

The economic prosperity of the decade led to stable prices, eliminating one major incentive to join unions. Unemployment rarely dipped below 5 percent in the 1920s and few workers feared real wage losses.The 1920s also saw a lack of strong leadership within the labor movement. Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers was an English-born American cigar maker who became a labor union leader and a key figure in American labor history. Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor , and served as that organization's president from 1886 to 1894 and from 1895 until his death in 1924...

of the American Federation of Labor

American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor was one of the first federations of labor unions in the United States. It was founded in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions disaffected from the Knights of Labor, a national labor association. Samuel Gompers was elected president of the Federation at its...

died in 1924 after serving as the organization's president for 37 years. Observers said successor William Green, who was the secretary-treasurer of the United Mine Workers

United Mine Workers

The United Mine Workers of America is a North American labor union best known for representing coal miners and coal technicians. Today, the Union also represents health care workers, truck drivers, manufacturing workers and public employees in the United States and Canada...

, "lacked the aggressiveness and the imagination of the AFL's first president". The AFL was down to less than 3 million members in 1925 after hitting a peak of 4 million members in 1920.

Employers across the nation led a successful campaign against unions known as the "American Plan", which sought to depict unions as "alien" to the nation's individualistic spirit. In addition, some employers, like the National Association of Manufacturers

National Association of Manufacturers

The National Association of Manufacturers is an advocacy group headquartered in Washington, D.C. with 10 additional offices across the country...

, used Red Scare

Red Scare

Durrell Blackwell Durrell Blackwell The term Red Scare denotes two distinct periods of strong Anti-Communism in the United States: the First Red Scare, from 1919 to 1920, and the Second Red Scare, from 1947 to 1957. The First Red Scare was about worker revolution and...

tactics to discredit unionism by linking them to Communist activities.

U.S. courts were less hospitable to union activities during the 1920s than in the past. In this decade, corporations used twice as many court injunctions against strikes than any comparable period. In addition, the practice of forcing employees (by threat of termination) to sign yellow-dog contract

Yellow-dog contract

A yellow-dog contract is an agreement between an employer and an employee in which the employee agrees, as a condition of employment, not to be a member of a labor union...

s that said they would not join a union was not outlawed until 1932.

Although the labor movement fell in prominence during the 1920s, the Great Depression

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

would ultimately bring it back to life.

Organized labor 1929–1955

The Great Depression and organized labor

The stock market crashed in October 1929, and ushered in the Great DepressionGreat Depression

The Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

. By the winter of 1932–33, the economy was so perilous that the unemployment rate hit the 25 percent mark. Unions lost members during this time because laborers could not afford to pay their dues and furthermore, numerous strikes against wage cuts left the unions impoverished: "... one might have expected a reincarnation of organizations seeking to overthrow the capitalistic system that was now performing so poorly. Some workers did indeed turn to such radical movements as Communism

Communism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

, but, in general, the nation seemed to have been shocked into inaction."

Though unions were not acting yet, cities across the nation witnessed local and spontaneous marches by frustrated relief applicants. In March 1930, hundreds of thousands of unemployed workers marched through New York City, Detroit, Washington, San Francisco and other cities in a mass protest organized by the Communist Party's Unemployed Councils. In 1931, more than 400 relief protests erupted in Chicago and that number grew to 550 in 1932. The leadership behind these organizations often came from radical groups like Communists and Socialists, who wanted to organize "unfocused neighborhood militancy into organized popular defense organizations". Workers turned to these radical groups until organized labor became more active in 1932, with the passage of the Norris-La Guardia Act.

The Norris-La Guardia Anti-Injunction Act of 1932

On March 23, 1932, President Herbert HooverHerbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover was the 31st President of the United States . Hoover was originally a professional mining engineer and author. As the United States Secretary of Commerce in the 1920s under Presidents Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge, he promoted partnerships between government and business...

signed what became known as the Norris-La Guardia Act, marking the first of many pro-union bills that Washington would pass in the 1930s. Also known as the Anti-Injunction Bill, it offered procedural and substantive protections against the easy issuance of court injunctions during labor disputes, which had limited union behavior in the 1920s. Although the act only applied to federal courts

United States federal courts

The United States federal courts make up the judiciary branch of federal government of the United States organized under the United States Constitution and laws of the federal government.-Categories:...

, numerous states would pass similar acts in the future. Additionally, the act outlawed yellow-dog contract

Yellow-dog contract

A yellow-dog contract is an agreement between an employer and an employee in which the employee agrees, as a condition of employment, not to be a member of a labor union...

s, which were documents some employers forced their employees to sign to ensure they would not join a union; employees who refused to sign were terminated from their jobs.

The passage of the Norris-La Guardia Act signified a victory for the American Federation of Labor

American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor was one of the first federations of labor unions in the United States. It was founded in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions disaffected from the Knights of Labor, a national labor association. Samuel Gompers was elected president of the Federation at its...

, which had been lobbying Congress to pass it for slightly more than five years. It also marked a large change in public policy. Up until the passage of this act, the collective bargaining rights of workers were severely hampered by judicial control.

FDR and the National Industrial Recovery Act

President Franklin D. RooseveltFranklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

took office on March 4, 1933, and immediately began implementing programs to alleviate the economic crisis. In June, he passed the National Industrial Recovery Act

National Industrial Recovery Act

The National Industrial Recovery Act , officially known as the Act of June 16, 1933 The National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA), officially known as the Act of June 16, 1933 The National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA), officially known as the Act of June 16, 1933 (Ch. 90, 48 Stat. 195, formerly...

, which gave workers the right to organize into unions. Though it contained other provisions, like minimum wage and maximum hours, its most significant passage was, "Employees shall have the right to organize and bargain collectively through representative of their own choosing, and shall be free from the interference, restraint, or coercion of employers." This portion, which was known as Section 7(a), was symbolic to workers in the United States because it stripped employers of their rights to either coerce them or refuse to bargain with them. While no power of enforcement was written into the law, it "recognized the rights of the industrial working class in the United States".

Although the National Industrial Recovery Act was ultimately deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1935 and replaced by the Wagner Act two months after that, it fueled workers to join unions and strengthened those organizations.

In response to both the Norris-La Guardia Act and the NIRA, workers who were previously unorganized in a number of industries—such as rubber workers, oil and gas workers and service workers—began to look for organizations that would allow them to band together. The NIRA strengthened workers' resolve to unionize and instead of participating in unemployment or hunger marches, they started to participate in strikes for union recognition in various industries.” In 1933, the number of work stoppages jumped to 1,695, double its figure from 1932. In 1934, 1,865 strikes occurred, involving more than 1.4 million workers.

The elections of 1934 might have reflected the "radical upheaval sweeping the country", as Roosevelt won the greatest majority either party ever held in the Senate and 322 Democrats won seats in the United States House of Representatives

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is one of the two Houses of the United States Congress, the bicameral legislature which also includes the Senate.The composition and powers of the House are established in Article One of the Constitution...

versus 103 Republicans. It is possible that "the great social movement

Social movement

Social movements are a type of group action. They are large informal groupings of individuals or organizations focused on specific political or social issues, in other words, on carrying out, resisting or undoing a social change....

from below thus strengthened the independence of the executive branch of government."

Despite such claims of the impact of such changes on the United States' political structure and on workers'empowerment, scholars have criticized the impacts of these policies from a classical economic perspective. Cole and Ohanian (2004) find that the New Deal's pro-labor policies are an important factor in explaining the weak recovery from the Great Depression and the rise in real wages in some industrial sectors during this time.

The American Federation of Labor: craft unionism vs. industrial unionism

The AFL was growing rapidly, from 2.1 million members in 1933 to 3.4 million in 1936. But it was experiencing severe internal stresses regarding how to organize new members. Traditionally, the AFL organized unions by craft rather than industry, where electricians or stationary engineers would form their own skill-oriented unions, rather than join a large automobile-making union. Most AFL leaders, including president William GreenWilliam Green (labor leader)

William Green was an American trade union leader. Green is best remembered for serving as the President of the American Federation of Labor from 1924 to 1952.-Early years:...

, were reluctant to shift from the organization's longstanding craft unionism

Craft unionism

Craft unionism refers to organizing a union in a manner that seeks to unify workers in a particular industry along the lines of the particular craft or trade that they work in by class or skill level...

and started to clash with other leaders within the organization, such as John L. Lewis

John L. Lewis

John Llewellyn Lewis was an American leader of organized labor who served as president of the United Mine Workers of America from 1920 to 1960...

. The issue came up at the annual AFL convention in San Francisco in 1934 and 1935, but the majority voted against a shift to industrial unionism

Industrial unionism

Industrial unionism is a labor union organizing method through which all workers in the same industry are organized into the same union—regardless of skill or trade—thus giving workers in one industry, or in all industries, more leverage in bargaining and in strike situations...

both years. After the defeat at the 1935 convention, nine leaders from the industrial faction led by Lewis met and organized the Committee for Industrial Organization within the AFL to "encourage and promote organization of workers in the mass production industries" for "educational and advisory" functions. The CIO, which later changed its name to the Congress of Industrial Organizations

Congress of Industrial Organizations

The Congress of Industrial Organizations, or CIO, proposed by John L. Lewis in 1932, was a federation of unions that organized workers in industrial unions in the United States and Canada from 1935 to 1955. The Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 required union leaders to swear that they were not...

(CIO), formed unions with the hope of bringing them into the AFL, but the AFL refused to extend full membership privileges to CIO unions. In 1938, the AFL expelled the CIO and its million members, and they formed a rival federation.

John L. Lewis and the CIO

John Llewellyn Lewis (1880–1969) was the president of the United Mine Workers of America (UMW) from 1920 to 1960, and the driving force behind the founding of the Congress of Industrial OrganizationsCongress of Industrial Organizations

The Congress of Industrial Organizations, or CIO, proposed by John L. Lewis in 1932, was a federation of unions that organized workers in industrial unions in the United States and Canada from 1935 to 1955. The Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 required union leaders to swear that they were not...

(CIO). Using UMW organizers the new CIO established the United Steel Workers of America (USWA) and organized millions of other industrial workers in the 1930s.

Lewis threw his support behind Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

(FDR) at the outset of the New Deal

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of economic programs implemented in the United States between 1933 and 1936. They were passed by the U.S. Congress during the first term of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The programs were Roosevelt's responses to the Great Depression, and focused on what historians call...

. After the passage of the Wagner Act

National Labor Relations Act

The National Labor Relations Act or Wagner Act , is a 1935 United States federal law that limits the means with which employers may react to workers in the private sector who create labor unions , engage in collective bargaining, and take part in strikes and other forms of concerted activity in...

in 1935, Lewis traded on the tremendous appeal that Roosevelt had with workers in those days, sending organizers into the coal fields to tell workers "The President wants you to join the Union." His UMW was one of FDR's main financial supporters in 1936, contributing over $500,000.

Lewis expanded his base by organizing the so-called "captive mines", those held by the steel producers such as U.S. Steel

U.S. Steel

The United States Steel Corporation , more commonly known as U.S. Steel, is an integrated steel producer with major production operations in the United States, Canada, and Central Europe. The company is the world's tenth largest steel producer ranked by sales...

. That required in turn organizing the steel industry, which had defeated union organizing drives in 1892 and 1919 and which had resisted all organizing efforts since then fiercely. The task of organizing steelworkers, on the other hand, put Lewis at odds with the AFL, which looked down on both industrial workers and the industrial unions that represented all workers in a particular industry, rather than just those in a particular skilled trade or craft.

Lewis was the first president of the Committee of Industrial Organizations. Lewis, in fact, was the CIO: his UMWA provided the great bulk of the financial resources that the CIO poured into organizing drives by the United Automobile Workers (UAW), the USWA, the Textile Workers Union and other newly formed or struggling unions. Lewis hired back many of the people he had exiled from the UMWA in the 1920s to lead the CIO and placed his protégé Philip Murray

Philip Murray

Philip Murray was a Scottish born steelworker and an American labor leader. He was the first president of the Steel Workers Organizing Committee , the first president of the United Steelworkers of America , and the longest-serving president of the Congress of Industrial Organizations .-Early...

at the head of the Steel Workers Organizing Committee

Steel Workers Organizing Committee

The Steel Workers Organizing Committee was one of two precursor labor organizations to the United Steelworkers. It was formed by the CIO in 1936. It disbanded in 1942 to become the United Steel Workers of America....

. Lewis played the leading role in the negotiations that led to the successful conclusion of the Flint sit-down strike

Flint Sit-Down Strike

The 1936–1937 Flint Sit-Down Strike changed the United Automobile Workers from a collection of isolated locals on the fringes of the industry into a major labor union and led to the unionization of the domestic United States automobile industry....

conducted by the UAW in 1936–1937 and in the Chrysler sit-down strike that followed.

The CIO's actual membership (as opposed to publicity figures) was 2,850,000 for February 1942. This included 537,000 members of the UAW, just under 500,000 Steel Workers, almost 300,000 members of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers, about 180,000 Electrical Workers, and about 100,000 Rubber Workers. The CIO also included 550,000 members of the United Mine Workers, which did not formally withdraw from the CIO until later in the year. The remaining membership of 700,000 was scattered among thirty-odd smaller unions.

Upsurge in World War II

The war mobilization dramatically expanded union membership, from 8.7 million in 1940 to over 14.3 million in 1945, about 36% of the work force. For the first time large numbers of women factory workers were enrolled. Both the AFL and CIO supported Roosevelt in 1940 and 1944, with 75% or more of their votes, millions of dollars, and tens of thousands of precinct workers. However, Lewis opposed Roosevelt on foreign policy grounds in 1940. He took the Mine Workers out of the CIO and rejoined the AFL. All labor unions strongly supported the war effort after June 1941 (when Germany invaded the Soviet Union). Left-wing activists crushed wildcat strikes. Nonetheless, Lewis realized that he had enormous leverage. In 1943, the middle of the war, when the rest of labor was observing a policy against strikes, Lewis led the miners out on a twelve-day strike for higher wages. The Conservative coalitionConservative coalition

In the United States, the conservative coalition was an unofficial Congressional coalition bringing together the conservative majority of the Republican Party and the conservative, mostly Southern, wing of the Democratic Party...

in Congress passed anti-union legislation, leading to the Taft-Hartley Act

Taft-Hartley Act

The Labor–Management Relations Act is a United States federal law that monitors the activities and power of labor unions. The act, still effective, was sponsored by Senator Robert Taft and Representative Fred A. Hartley, Jr. and became law by overriding U.S. President Harry S...

of 1947.

Walter Reuther and UAW

The Flint Sit-Down StrikeFlint Sit-Down Strike

The 1936–1937 Flint Sit-Down Strike changed the United Automobile Workers from a collection of isolated locals on the fringes of the industry into a major labor union and led to the unionization of the domestic United States automobile industry....

of 1936–37 was the decisive event in the formation of the United Auto Workers Union (UAW).

During the war Walter Reuther

Walter Reuther

Walter Philip Reuther was an American labor union leader, who made the United Automobile Workers a major force not only in the auto industry but also in the Democratic Party in the mid 20th century...

took control of the UAW, and soon led major strikes in 1946. He ousted the Communists from the positions of power, especially at the Ford local. He was one of the most articulate and energetic leaders of the CIO, and of the merged AFL-CIO

AFL-CIO

The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations, commonly AFL–CIO, is a national trade union center, the largest federation of unions in the United States, made up of 56 national and international unions, together representing more than 11 million workers...

. Using brilliant negotiating tactics he leveraged high profits for the Big Three automakers into higher wages and superior benefits for UAW members.

PAC and politics of 1940s

New enemies appeared for the labor unions after 1935. Newspaper columnist Westbrook PeglerWestbrook Pegler

Francis James Westbrook Pegler was an American journalist and writer. He was a popular columnist in the 1930s and 1940s famed for his opposition to the New Deal and labor unions. Pegler criticized every president from Herbert Hoover to FDR to Harry Truman to John F. Kennedy...

was especially outraged by the New Deal's support for powerful labor unions that he considered morally and politically corrupt. Pegler saw himself a populist and muckraker whose mission was to warn the nation that dangerous leaders were in power. In 1941 Pegler became the first columnist ever to win a Pulitzer Prize

Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prize is a U.S. award for achievements in newspaper and online journalism, literature and musical composition. It was established by American publisher Joseph Pulitzer and is administered by Columbia University in New York City...

for reporting, for his work in exposing racketeering in Hollywood labor unions, focusing on the criminal career of William Morris Bioff

William Morris Bioff

William Morris Bioff was an American organized crime figure who operated as a labor leader in the movie production business from the 1920s through the 1940s...

. Pegler's popularity reflected a loss of support for unions and liberalism generally, especially as shown by the dramatic Republican gains in the 1946 elections, often using an anti-union theme.

With the end of the war in August 1945 came a wave of major strikes, mostly led by the CIO. In November, the UAW sent their 180,000 GM workers to the picket lines; they were joined in January 1946 by a half-million steelworkers, as well as over 200,000 electrical workers and 150,000 packinghouse workers. Combined with many smaller strikes a new record of strike activity was set. The results were mixed, with the unions making some gains, but the economy was disordered by the rapid termination of war contracts, the complex reconversion to peactime production, the return to the labor force of 12 million servicemen, and the return home of millions of women workers. The conservative control of Congress blocked liberal legislation, and "Operation Dixie", the CIO's efforts to expand massively into the South, failed.

Taft-Hartley Act

The Taft-Hartley Act in 1947 revised the Wagner Act to include restrictions on unions as well as management. It was a response to public demands for action after the wartime coal strikes and the postwar strikes in steel, autos and other industries that were perceived to have damaged the economy, as well as a threatened 1946 railroad strike that was called off at the last minute before it shut down the national economy. The Act was bitterly fought by unions, vetoed by President Harry S. TrumanHarry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman was the 33rd President of the United States . As President Franklin D. Roosevelt's third vice president and the 34th Vice President of the United States , he succeeded to the presidency on April 12, 1945, when President Roosevelt died less than three months after beginning his...

, and passed over his veto. Repeated union efforts to repeal or modify it always failed, and it remains in effect today.

The Act, officially known as the Labor-Management Relations Act, was sponsored by Senator Robert Taft

Robert Taft

Robert Alphonso Taft , of the Taft political family of Cincinnati, was a Republican United States Senator and a prominent conservative statesman...

and Representative Fred Hartley

Fred A. Hartley, Jr.

Fred Allan Hartley, Jr. was an American Republican Party politician from New Jersey. Hartley served ten terms in the United States House of Representatives where he represented the New Jersey's 8th and New Jersey's 10th congressional districts...

, both Republicans. Congress overrode the veto on June 23, 1947, establishing the act as a law. Truman described the act as a "slave-labor bill" in his veto, but he did invoke it.

The Taft-Hartley Act amended the Wagner Act, officially known as the National Labor Relations Act

National Labor Relations Act

The National Labor Relations Act or Wagner Act , is a 1935 United States federal law that limits the means with which employers may react to workers in the private sector who create labor unions , engage in collective bargaining, and take part in strikes and other forms of concerted activity in...

, of 1935. The amendments added to the NLRA a list of prohibited actions, or "unfair labor practices", on the part of unions. The NLRA had previously prohibited only unfair labor practices committed by employers. It prohibited jurisdictional strikes, in which a union strikes in order to pressure an employer to assign particular work to the employees that union represents, and secondary boycotts and "common situs" picketing, in which unions picket, strike, or refuse to handle the goods of a business with which they have no primary dispute but which is associated with a targeted business. A later statute, the Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act

Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act

The Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act of 1959 , is a United States labor law that regulates labor unions' internal affairs and their officials' relationships with employers.-Background:...

, passed in 1959, tightened these restrictions on secondary boycotts still further.

The Act outlawed closed shop

Closed shop

A closed shop is a form of union security agreement under which the employer agrees to hire union members only, and employees must remain members of the union at all times in order to remain employed....

s, which were contractual agreements that required an employer to hire only union members. Union shop

Union shop

A union shop is a form of a union security clause under which the employer agrees to hire either labor union members or nonmembers but all non-union employees must become union members within a specified period of time or lose their jobs...

s, in which new recruits must join the union within a certain amount of time, are permitted, but only as part of a collective bargaining agreement and only if the contract allows the worker at least thirty days after the date of hire or the effective date of the contract to join the union. The National Labor Relations Board

National Labor Relations Board

The National Labor Relations Board is an independent agency of the United States government charged with conducting elections for labor union representation and with investigating and remedying unfair labor practices. Unfair labor practices may involve union-related situations or instances of...

and the courts have added other restrictions on the power of unions to enforce union security

Union security

A union security agreement is a contractual agreement, usually part of a union collective bargaining agreement, in which an employer and a trade or labor union agree on the extent to which the union may compel employees to join the union, and/or whether the employer will collect dues, fees, and...

clauses and have required them to make extensive financial disclosures to all members as part of their duty of fair representation

Duty of fair representation

The duty of fair representation is incumbent upon U.S. labor unions that are the exclusive bargaining representative of workers in a particular group. It is the obligation to represent all employees fairly, in good faith, and without discrimination...

. On the other hand, a few years after the passage of the Act Congress repealed the provisions requiring a vote by workers to authorize a union shop, when it became apparent that workers were approving them in virtually every case.

The amendments also authorized individual states to outlaw union security clauses entirely in their jurisdictions by passing "right-to-work" laws. Currently all of the states in the Deep South

Deep South

The Deep South is a descriptive category of the cultural and geographic subregions in the American South. Historically, it is differentiated from the "Upper South" as being the states which were most dependent on plantation type agriculture during the pre-Civil War period...

and a number of traditionally Republican states in the Midwest, Plains and Rocky Mountains regions have right-to-work law

Right-to-work law

Right-to-work laws are statutes enforced in twenty-two U.S. states, mostly in the southern or western U.S., allowed under provisions of the federal Taft–Hartley Act, which prohibit agreements between labor unions and employers that make membership, payment of union dues, or fees a condition of...

s.

The amendments required unions and employers to give sixty days' notice before they may undertake strikes or other forms of economic action in pursuit of a new collective bargaining agreement; it did not, on the other hand, impose any "cooling-off period" after a contract expired. Although the Act also authorized the President to intervene in strikes or potential strikes that create a national emergency, the President has used that power less and less frequently in each succeeding decade.

Fighting communism

The AFL and CIO unions supported the Cold War policies of the Truman administration, including the Truman DoctrineTruman Doctrine

The Truman Doctrine was a policy set forth by U.S. President Harry S Truman in a speech on March 12, 1947 stating that the U.S. would support Greece and Turkey with economic and military aid to prevent their falling into the Soviet sphere...

, the Marshall Plan

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan was the large-scale American program to aid Europe where the United States gave monetary support to help rebuild European economies after the end of World War II in order to combat the spread of Soviet communism. The plan was in operation for four years beginning in April 1948...

and NATO. Left wing elements in the CIO protested and were forced out of the main unions. Thus Walter Reuther

Walter Reuther

Walter Philip Reuther was an American labor union leader, who made the United Automobile Workers a major force not only in the auto industry but also in the Democratic Party in the mid 20th century...

of the United Automobile Workers purged the UAW of all Communist elements. He was active in the CIO umbrella as well, taking the lead in expelling eleven Communist-dominated unions from the CIO in 1949. As a prominent figure in the anti-Communist left, Reuther was a founder of the liberal umbrella group Americans for Democratic Action

Americans for Democratic Action

Americans for Democratic Action is an American political organization advocating progressive policies. ADA works for social and economic justice through lobbying, grassroots organizing, research and supporting progressive candidates.-History:...

in 1947. In 1949 he led the CIO delegation to the London conference that set up the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions

International Confederation of Free Trade Unions

The International Confederation of Free Trade Unions was an international trade union. It came into being on 7 December 1949 following a split within the World Federation of Trade Unions , and was dissolved on 31 October 2006 when it merged with the World Confederation of Labour to form the...

in opposition to the communist-dominated World Federation of Trade Unions

World Federation of Trade Unions

The World Federation of Trade Unions was established in 1945 to replace the International Federation of Trade Unions. Its mission was to bring together trade unions across the world in a single international organization, much like the United Nations...

. He had left the Socialist Party in 1939, and throughout the 1950s and 1960s was a leading spokesman for liberal interests in the CIO and in the Democratic Party.

AFL and CIO merger 1955

The friendly merger of the AFL and CIO marked an end not only to the acrimony and jurisdictional conflicts between the coalitions, it also signaled the end of the era of experimentation and expansion that began in the mid 1930s. Merger became politically possible because of the deaths of Green of the AFL and Murray of the CIO in late 1952, replaced by George MeanyGeorge Meany

William George Meany led labor union federations in the United States. As an officer of the American Federation of Labor, he represented the AFL on the National War Labor Board during World War II....