The

March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (or

"The Great March on Washington,

" as styled in a sound recording released after the event) was the largest

political rallyA demonstration or street protest is action by a mass group or collection of groups of people in favor of a political or other cause; it normally consists of walking in a mass march formation and either beginning with or meeting at a designated endpoint, or rally, to hear speakers.Actions such as...

for human rights in United States history and called for civil and economic rights for

African AmericanAfrican Americans are citizens or residents of the United States who have at least partial ancestry from any of the native populations of Sub-Saharan Africa and are the direct descendants of enslaved Africans within the boundaries of the present United States...

s. It took place in

Washington, D.C.Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

on Wednesday, August 28, 1963.

Martin Luther King, Jr.Martin Luther King, Jr. was an American clergyman, activist, and prominent leader in the African-American Civil Rights Movement. He is best known for being an iconic figure in the advancement of civil rights in the United States and around the world, using nonviolent methods following the...

delivered his historic "

I Have a Dream"I Have a Dream" is a 17-minute public speech by Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered on August 28, 1963, in which he called for racial equality and an end to discrimination...

" speech advocating racial harmony at the

Lincoln MemorialThe Lincoln Memorial is an American memorial built to honor the 16th President of the United States, Abraham Lincoln. It is located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. The architect was Henry Bacon, the sculptor of the main statue was Daniel Chester French, and the painter of the interior...

during the march.

The march was organized by a group of civil rights, labor, and religious organizations, under the theme "jobs, and freedom." Estimates of the number of participants varied from 200,000 (police) to over 300,000 (leaders of the march). Observers estimated that 75–80% of the marchers were black and the rest were

whiteWhite Americans are people of the United States who are considered or consider themselves White. The United States Census Bureau defines White people as those "having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa...

and other minorities.

The march is widely credited with helping to pass the

Civil Rights Act (1964)The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a landmark piece of legislation in the United States that outlawed major forms of discrimination against African Americans and women, including racial segregation...

and the

Voting Rights Act (1965)The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of national legislation in the United States that outlawed discriminatory voting practices that had been responsible for the widespread disenfranchisement of African Americans in the U.S....

.

Background and Organization

The march was planned and initiated by

A. Philip RandolphAsa Philip Randolph was a leader in the African American civil-rights movement and the American labor movement. He organized and led the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first predominantly Negro labor union. In the early civil-rights movement, Randolph led the March on Washington...

, the president of the

Brotherhood of Sleeping Car PortersThe Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was, in 1925, the first labor organization led by blacks to receive a charter in the American Federation of Labor . It merged in 1978 with the Brotherhood of Railway and Airline Clerks , now known as the Transportation Communications International Union.The...

, president of the Negro American Labor Council, and vice president of the

AFL-CIOThe American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations, commonly AFL–CIO, is a national trade union center, the largest federation of unions in the United States, made up of 56 national and international unions, together representing more than 11 million workers...

. Randolph had planned a similar march in 1941. The threat of the earlier march had convinced

PresidentThe President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

RooseveltFranklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

to establish the

Committee on Fair Employment PracticeExecutive Order 8802 was signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on June 25, 1941, to prohibit racial discrimination in the national defense industry...

and ban discriminatory hiring in the defense industry.

The 1963 march was an important part of the rapidly expanding Civil Rights Movement. It also marked the 100th anniversary of the signing of the

Emancipation ProclamationThe Emancipation Proclamation is an executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War using his war powers. It proclaimed the freedom of 3.1 million of the nation's 4 million slaves, and immediately freed 50,000 of them, with nearly...

by

Abraham LincolnAbraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

.

In the political sense, the march was organized by a coalition of organizations and their leaders including: Randolph who was chosen as the titular head of the march,

James FarmerJames Leonard Farmer, Jr. was a civil rights activist and leader in the American Civil Rights Movement. He was the initiator and organizer of the 1961 Freedom Ride, which eventually led to the desegregation of inter-state transportation in the United States.In 1942, Farmer co-founded the Committee...

(president of the

Congress of Racial EqualityThe Congress of Racial Equality or CORE was a U.S. civil rights organization that originally played a pivotal role for African-Americans in the Civil Rights Movement...

),

John LewisJohn Robert Lewis is the U.S. Representative for , serving since 1987. He was a leader in the American Civil Rights Movement and chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee , playing a key role in the struggle to end segregation...

(president of the

Student Nonviolent Coordinating CommitteeThe Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee ' was one of the principal organizations of the American Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. It emerged from a series of student meetings led by Ella Baker held at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina in April 1960...

),

Martin Luther King, Jr.Martin Luther King, Jr. was an American clergyman, activist, and prominent leader in the African-American Civil Rights Movement. He is best known for being an iconic figure in the advancement of civil rights in the United States and around the world, using nonviolent methods following the...

(president of the

Southern Christian Leadership ConferenceThe Southern Christian Leadership Conference is an African-American civil rights organization. SCLC was closely associated with its first president, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr...

),

Roy WilkinsRoy Wilkins was a prominent civil rights activist in the United States from the 1930s to the 1970s. Wilkins' most notable role was in his leadership of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People ....

(president of the

NAACPThe National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, usually abbreviated as NAACP, is an African-American civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909. Its mission is "to ensure the political, educational, social, and economic equality of rights of all persons and to...

),

Whitney YoungWhitney Moore Young Jr. was an American civil rights leader.He spent most of his career working to end employment discrimination in the United States and turning the National Urban League from a relatively passive civil rights organization into one that aggressively fought for equitable access to...

(president of the

National Urban LeagueThe National Urban League , formerly known as the National League on Urban Conditions Among Negroes, is a nonpartisan civil rights organization based in New York City that advocates on behalf of African Americans and against racial discrimination in the United States. It is the oldest and largest...

).

The mobilization and logistics of the actual march itself was administered by deputy director

Bayard RustinBayard Rustin was an American leader in social movements for civil rights, socialism, pacifism and non-violence, and gay rights.In the pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation , Rustin practiced nonviolence...

, a civil rights veteran and organizer of the 1947

Journey of ReconciliationThe Journey of Reconciliation was a form of non-violent direct action to challenge segregation laws on interstate buses in the Southern United States....

, the first of the Freedom Rides to test the

Supreme CourtThe Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

ruling that banned racial discrimination in interstate travel. Rustin was a long-time associate of both Randolph and Dr. King. With Randolph concentrating on building the march's political coalition, Rustin built and led the team of activists and organizers who publicized the march and recruited the marchers, coordinated the buses and trains, provided the marshals, and set up and administered all of the logistic details of a mass march in the nation's capital.

The march was not universally supported among civil rights activists. Some were concerned that it might turn violent, which could undermine pending legislation and damage the international image of the movement. The march was condemned by

Malcolm XMalcolm X , born Malcolm Little and also known as El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz , was an African American Muslim minister and human rights activist. To his admirers he was a courageous advocate for the rights of African Americans, a man who indicted white America in the harshest terms for its...

, spokesperson for the

Nation of IslamThe Nation of Islam is a mainly African-American new religious movement founded in Detroit, Michigan by Wallace D. Fard Muhammad in July 1930 to improve the spiritual, mental, social, and economic condition of African-Americans in the United States of America. The movement teaches black pride and...

, who termed it the "farce on Washington".

March organizers themselves disagreed over the purpose of the march. The NAACP and Urban League saw it as a gesture of support for a civil rights bill that had been introduced by the

KennedyJohn Fitzgerald "Jack" Kennedy , often referred to by his initials JFK, was the 35th President of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963....

Administration. Randolph, King, and the

Southern Christian Leadership ConferenceThe Southern Christian Leadership Conference is an African-American civil rights organization. SCLC was closely associated with its first president, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr...

(SCLC) saw it as a way of raising both civil rights and economic issues to national attention beyond the Kennedy bill.

Student Nonviolent Coordinating CommitteeThe Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee ' was one of the principal organizations of the American Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. It emerged from a series of student meetings led by Ella Baker held at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina in April 1960...

(SNCC) and

Congress of Racial EqualityThe Congress of Racial Equality or CORE was a U.S. civil rights organization that originally played a pivotal role for African-Americans in the Civil Rights Movement...

(CORE) saw it as a way of challenging and condemning the Kennedy administration's inaction and lack of support for civil rights for African Americans.

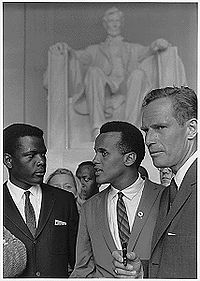

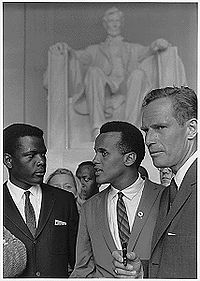

The March

On August 28, more than 2,000

busA bus is a road vehicle designed to carry passengers. Buses can have a capacity as high as 300 passengers. The most common type of bus is the single-decker bus, with larger loads carried by double-decker buses and articulated buses, and smaller loads carried by midibuses and minibuses; coaches are...

es, 21 special

trainA train is a connected series of vehicles for rail transport that move along a track to transport cargo or passengers from one place to another place. The track usually consists of two rails, but might also be a monorail or maglev guideway.Propulsion for the train is provided by a separate...

s, 10 chartered airliners, and uncounted cars converged on Washington. All regularly scheduled planes, trains, and buses were also filled to capacity.

The march began at the

Washington MonumentThe Washington Monument is an obelisk near the west end of the National Mall in Washington, D.C., built to commemorate the first U.S. president, General George Washington...

and ended at the

Lincoln MemorialThe Lincoln Memorial is an American memorial built to honor the 16th President of the United States, Abraham Lincoln. It is located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. The architect was Henry Bacon, the sculptor of the main statue was Daniel Chester French, and the painter of the interior...

with a program of music and speakers. The march failed to start on time because its leaders were meeting with members of

CongressThe United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

. To the leaders' surprise, the assembled group began to march from the

Washington MonumentThe Washington Monument is an obelisk near the west end of the National Mall in Washington, D.C., built to commemorate the first U.S. president, General George Washington...

to the

Lincoln MemorialThe Lincoln Memorial is an American memorial built to honor the 16th President of the United States, Abraham Lincoln. It is located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. The architect was Henry Bacon, the sculptor of the main statue was Daniel Chester French, and the painter of the interior...

without them.

The 1963 March also spurred anniversary marches that occur every five years, with the 20th and 25th being some of the most well known. The 25th Anniversary theme was "We Still have a Dream...Jobs*Peace*Freedom."

Speakers

Representatives from each of the sponsoring organizations addressed the crowd from the podium at the Lincoln Memorial. Speakers included all six civil-rights leaders of the so called, "

Big SixThe chairmen, presidents, or co-founders of some of the civil rights organizations active during the height of the American Civil Rights movement, likely mockingly named the "Big Six" by Malcolm X, include:* Martin Luther King, Jr...

"; Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish religious leaders; and labor leader

Walter ReutherWalter Philip Reuther was an American labor union leader, who made the United Automobile Workers a major force not only in the auto industry but also in the Democratic Party in the mid 20th century...

. The one female speaker was

Josephine BakerJosephine Baker was an American dancer, singer, and actress who found fame in her adopted homeland of France. She was given such nicknames as the "Bronze Venus", the "Black Pearl", and the "Créole Goddess"....

.

Floyd McKissickFloyd Bixler McKissick was born in Asheville, North Carolina on March 9, 1922. He became the first African American student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill's Law School. In 1966 he became leader of CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality, taking over from James L. Farmer, Jr. A...

read James Farmer's speech because Farmer had been arrested during a protest in

LouisianaLouisiana is a state located in the southern region of the United States of America. Its capital is Baton Rouge and largest city is New Orleans. Louisiana is the only state in the U.S. with political subdivisions termed parishes, which are local governments equivalent to counties...

; Farmer had written that the protests would not stop "until the dogs stop biting us in the South and the rats stop biting us in the

NorthNorthern United States, also sometimes the North, may refer to:* A particular grouping of states or regions of the United States of America. The United States Census Bureau divides some of the northernmost United States into the Midwest Region and the Northeast Region...

."

Controversy over John Lewis' speech

Although one of the officially stated purposes of the march was to support the civil rights bill introduced by the Kennedy Administration, several of the speakers criticized the proposed law as insufficient.

John Lewis of

SNCCThe Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee ' was one of the principal organizations of the American Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. It emerged from a series of student meetings led by Ella Baker held at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina in April 1960...

was the youngest speaker at the event. His speech—which a number of SNCC activists had helped write—took the Administration to task for how little it had done to protect southern blacks and civil rights workers under attack in the Deep South. Cut from his original speech at the insistence of more conservative and pro-Kennedy leaders were phrases such as:

In good conscience, we cannot support wholeheartedly the administration's civil rights bill, for it is too little and too late. ...

I want to know, which side is the federal government on?...

The revolution is a serious one. Mr. Kennedy is trying to take the revolution out of the streets and put it into the courts. Listen, Mr. Kennedy. Listen, Mr. Congressman. Listen, fellow citizens. The black masses are on the march for jobs and freedom, and we must say to the politicians that there won't be a "cooling-off" period.

...We will march through the South, through the heart of Dixie, the way Sherman did. We shall pursue our own scorched earthA scorched earth policy is a military strategy or operational method which involves destroying anything that might be useful to the enemy while advancing through or withdrawing from an area...

policy and burn Jim Crow to the ground—nonviolently...

Many activists from SNCC, CORE, and even SCLC were angry at what they considered censorship of his speech. A. Philip Randolph also spoke with an inspirational speech.

Singers

Gospel legend

Mahalia JacksonMahalia Jackson – January 27, 1972) was an African-American gospel singer. Possessing a powerful contralto voice, she was referred to as "The Queen of Gospel"...

sang "

How I Got OverHow I Got Over is a Gospel hymn composed and published in 1951 by Clara Ward . Notable recordings of this work have been made by Mahalia Jackson , Aretha Franklin , and the Blind Boys of Alabama How I Got Over is a Gospel hymn composed and published in 1951 by Clara Ward (1924-1973). Notable...

", musician

Bob DylanBob Dylan is an American singer-songwriter, musician, poet, film director and painter. He has been a major and profoundly influential figure in popular music and culture for five decades. Much of his most celebrated work dates from the 1960s when he was an informal chronicler and a seemingly...

performed several songs, including "

Only a Pawn in Their Game"Only a Pawn in their Game" is a song written by Bob Dylan about the assassination of civil rights activist Medgar Evers. It was released on Dylan's The Times They Are a-Changin album of 1964...

", about the culturally fed racial hatred amongst Southern whites that led to the assassination of

Medgar EversMedgar Wiley Evers was an African American civil rights activist from Mississippi involved in efforts to overturn segregation at the University of Mississippi...

; and "

When the Ship Comes In"When the Ship Comes In" is a folk music song by Bob Dylan, released on his third album, The Times They Are a-Changin, in 1964.Joan Baez states in the documentary film No Direction Home that the song was, more or less, inspired by a hotel clerk who refused to allow Dylan a room due to his...

", during which he was joined by fellow folk singer

Joan BaezJoan Chandos Baez is an American folk singer, songwriter, musician and a prominent activist in the fields of human rights, peace and environmental justice....

, who earlier had led the crowds in several verses of "

We Shall Overcome"We Shall Overcome" is a protest song that became a key anthem of the African-American Civil Rights Movement . The title and structure of the song are derived from an early gospel song by African-American composer Charles Albert Tindley...

" and "Oh Freedom".

Peter, Paul and MaryPeter, Paul and Mary were an American folk-singing trio whose nearly 50-year career began with their rise to become a paradigm for 1960s folk music. The trio was composed of Peter Yarrow, Paul Stookey and Mary Travers...

sang "

If I Had a Hammer"If I Had a Hammer " is a song written by Pete Seeger and Lee Hays. It was written in 1949 in support of the progressive movement, and was first recorded by The Weavers, a folk music quartet composed of Seeger, Hays, Ronnie Gilbert and Fred Hellerman, and then by Peter, Paul and Mary.- Early...

" and Dylan's "

Blowin' In The Wind"Blowin' in the Wind" is a song written by Bob Dylan and released on his album The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan in 1963. Although it has been described as a protest song, it poses a series of questions about peace, war and freedom...

".

Marian AndersonMarian Anderson was an African-American contralto and one of the most celebrated singers of the twentieth century...

sang at the march as well.

King gave his famous

I Have a Dream"I Have a Dream" is a 17-minute public speech by Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered on August 28, 1963, in which he called for racial equality and an end to discrimination...

speech, which was carried live by TV stations.

Media coverage

Media attention gave the march national exposure, carrying the organizers' speeches and offering their own commentary. In his section

The March on Washington and Television News, William Thomas notes: "Over five hundred cameramen, technicians, and correspondents from the major networks were set to cover the event. More cameras would be set up than had filmed the last Presidential inauguration. One camera was positioned high in the Washington Monument, to give dramatic vistas of the marchers".

Criticism

Black nationalistBlack nationalism advocates a racial definition of indigenous national identity, as opposed to multiculturalism. There are different indigenous nationalist philosophies but the principles of all African nationalist ideologies are unity, and self-determination or independence from European society...

Malcolm XMalcolm X , born Malcolm Little and also known as El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz , was an African American Muslim minister and human rights activist. To his admirers he was a courageous advocate for the rights of African Americans, a man who indicted white America in the harshest terms for its...

, in his

Message to the Grass Roots"Message to the Grass Roots" is the name of a public speech by Malcolm X at the Northern Negro Grass Roots Leadership Conference on November 10, 1963, in King Solomon Baptist Church in Detroit, Michigan...

speech, criticized the march, describing it as "a picnic" and "a circus". He said the civil rights leaders had diluted the original purpose of the march, which had been to show the strength and anger of black people, by allowing white people and organizations to help plan and participate in the march.

See also

External links

- The March, 1963, from the National Archives YouTube Channel

- March on Washington – King Encyclopedia, Stanford University

The Leland Stanford Junior University, commonly referred to as Stanford University or Stanford, is a private research university on an campus located near Palo Alto, California. It is situated in the northwestern Santa Clara Valley on the San Francisco Peninsula, approximately northwest of San...

- March on Washington August 28, 1963 ~ Civil Rights Movement Veterans

- March on Washington, WDAS History

- The 1963 March on Washington - slideshow by Life magazine

- Original Program for the March on Washington

- Martin Luther King Jr.'s speech at the March

- Bob Dylan, accompanied by Joan Baez, performing When the Ship Comes in at the March – from YouTube

- YouTube clip of Bob Dylan performing Only a Pawn in Their Game at the March

The source of this article is

wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. The text of this article is licensed under the

GFDL.