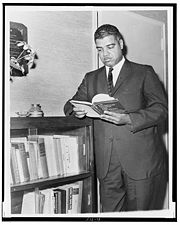

Whitney Young

Encyclopedia

Whitney Moore Young Jr. was an American civil rights

leader.

He spent most of his career working to end employment discrimination in the United States

and turning the National Urban League

from a relatively passive civil rights

organization into one that aggressively fought for equitable access to socioeconomic opportunity for the historically disenfranchised.

, Kentucky

, on July 31, 1921 to educated parents. His father was the president of the Lincoln Institute, which was where Whitney was raised and educated. Whitney's mother, Laura Young, was the first female postmistress in Kentucky, the first African-American postmistress in Kentucky, and the second in the United States.

Young earned a bachelor of science degree from Kentucky State University

, a historically black institution. At Kentucky State, Young was a member of Alpha Phi Alpha

fraternity.

During World War II

, Young was trained in electrical engineering at MIT

. He was then assigned to a road construction crew of black soldiers supervised by Southern white officers. After just three weeks, he was promoted from private to first sergeant, creating hostility on both sides. Despite the tension, Young was able to mediate effectively between his white officers and black soldiers angry at their poor treatment. This situation propelled Young into a career in race relations.

After the war, Young joined his wife, Margaret, at the University of Minnesota

, where he earned a Masters Degree in social work in 1947 and volunteered for the St. Paul

branch of the National Urban League

. He was then appointed to a leadership position in that branch.

In 1950, Young became president of the National Urban League's Omaha, Nebraska

chapter. In that position, he helped get black workers into jobs previously reserved for whites. Under his leadership, the chapter tripled its number of paying members.

In his next position as dean of social work at Atlanta University

, Young supported alumni in their boycott

of the Georgia Conference of Social Welfare. The organization had a poor record of placing African Americans in good jobs. In 1960, Young was awarded a Rockefeller Foundation

grant for a postgraduate year at Harvard University

. In the same year, he joined the NAACP and rose to become state president.

Young was a close friend of Roy Wilkins

, who was the executive director

for the NAACP in the 1960s.

. Within four years he expanded the organization from 38 employees to 1,600 employees; and from an annual budget of $325,000 to one of $6,100,000. He was President of the National Urban League

from 1961 until his death in 1971.

The Urban League had traditionally been a cautious and moderate organization with many white members. During Young's ten-year tenure at the League, he brought the organization to the forefront of the American Civil Rights Movement. He both greatly expanded its mission and kept the support of influential white business and political leaders. As part of the League's new mission, Young initiated programs like "Street Academy", an alternative education system to prepare high school dropouts for college, and "New Thrust", an effort to help local black leaders identify and solve community problems.

Young also pushed for federal aid to cities, proposing a domestic "Marshall Plan

". This plan, which called for $145 billion in spending over 10 years, was partially incorporated into President

Lyndon B. Johnson's

War on Poverty

. Young described his proposals for integration, social programs, and affirmative action in his two books, To Be Equal (1964) and Beyond Racism (1969).

As executive director of the League, Young pushed major corporations to hire more blacks. In doing so, he fostered close relationships with CEOs such as Henry Ford II

, leading some blacks to charge that Young had sold out to the white establishment. Young denied these charges and stressed the importance of working within the system to effect change. Still, Young was not afraid to take a bold stand in favor of civil rights. For instance, in 1963, Young was one of the organizers of the March on Washington

despite the opposition of many white business leaders.

Despite his reluctance to enter politics himself, Young was an important advisor to Presidents Kennedy

Despite his reluctance to enter politics himself, Young was an important advisor to Presidents Kennedy

, Johnson

, and Nixon

. In 1968, representatives of President-elect Richard Nixon

tried to interest Young in a Cabinet

post, but Young refused, believing that he could accomplish more through the Urban League.

Young had a particularly close relationship with President Johnson

, and in 1969, Johnson

honored Young with the highest civilian award, the Presidential Medal of Freedom

. Young, in turn, was impressed by Johnson's commitment to civil rights.

Despite their close personal relationship, Young was frustrated by Johnson's attempts to use him to balance Martin Luther King's

opposition to the increasingly unpopular Vietnam War

. Young publicly supported Johnson's war policy, but came to oppose the war after the end of Johnson's presidency.

In 1968, Herman B. Furguson and Arthur Harris were convicted of conspiring to murder Young as part of what was described as a "black revolutionary plot." The trial took place in the New York State Supreme Court, with Justice Paul Balsam

presiding.

Mr. Young spent his tenure as President of NASW ensuring that the profession kept pace with the troubling social and human challenges it was facing. NASW News articles document his call to action for social workers to address social welfare through poverty reduction, race reconciliation, and putting an end to the War in Vietnam. In the NASW News, July 1970, he challenged his professional social work organization to take leadership in the national struggle for social welfare:

The NASW News, May 1971, tribute to Young noted that “As usual Whitney Young was preparing to do battle on the major issues and programs facing the association and the nation. And he was doing it with his usual aplomb-dapper, self-assured, ready to deal with the “power” people to bring about change for the powerless.”

Mr. Young was also well known in the profession of Social Work for being the Dean of the school of Social Work at Clark Atlanta University

, which now bears his name. The school has a solid history of Social work, graduating leaders in the profession and having created and founded the "Afro-Centric" prospective of Social Work, a frequently used theory practice in urban areas.

In his last column as President for NASW, Young wrote, “whatever we do we should tell the public what we are doing and why. They have to hear from social workers as much as they hear from reporters and government officials.”

, Nigeria

, where he was attending a conference sponsored by the African-American Institute. President

Nixon

sent a plane to Nigeria to collect Young's body and traveled to Kentucky

to deliver the eulogy

at Young's funeral.

Hundreds of schools and other sites are named for Young. For instance, in 1973, the East Capitol Street Bridge in Washington, D.C.

, was renamed the Whitney Young Memorial Bridge

in his honor.

Clark Atlanta University

named its School of Social Work, where Whitney Young served as Dean, in Young's honor. The Whitney M. Young School of Social Work is well-known for founding the "Afro-Centric" prospective of social work.

The Boy Scouts of America

created the Whitney M. Young Jr. Service Award to recognize outstanding services by an adult individual or an organization for demonstrated involvement in the development and implementation of Scouting opportunities for youth from rural or low-income urban backgrounds.

Whitney Young High School in Chicago

was named after him. Whitney M. Young High School

in Cleveland

, Ohio

was also named after him.

Young's birthplace (Whitney Young Birthplace and Museum

) in Shelby County, Kentucky is a designated National Historic Landmark

, with a museum dedicated to Young's life and achievements.

Young was honored on a United States Postage stamp as part of its on-going Black Heritage series.

In 1973, The African American MBA Association at The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania held its first Annual Whitney M. Young Jr. Memorial Conference. After 38 years, the Whitney M. Young Jr. Memorial Conference is the longest student-run conference held at The Wharton School.

"I am not anxious to be the loudest voice or the most popular. But I would like to think that at a crucial moment, I was an effective voice of the voiceless, an effective hope of the hopeless."

"You can holler, protest, march, picket and demonstrate, but somebody must be able to sit in on the strategy conferences and plot a course. There must be strategies, the researchers, the professionals to carry out the program. That's our role."

"Black Power simply means: Look at me, I'm here. I have dignity. I have pride. I have roots. I insist, I demand that I participate in those decisions that affect my life and the lives of my children. It means that I am somebody."

"Liberalism seems to be related to the distance people are from the problem."

"I'd rather be prepared for an opportunity that never comes than have an opportunity come and I am not prepared."

, Ossie Davis

, Julian Bond

, Roy Innis

, Vernon Jordan, Donald Rumsfeld

, and Dorothy Height

.

Civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from unwarranted infringement by governments and private organizations, and ensure one's ability to participate in the civil and political life of the state without discrimination or repression.Civil rights include...

leader.

He spent most of his career working to end employment discrimination in the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

and turning the National Urban League

National Urban League

The National Urban League , formerly known as the National League on Urban Conditions Among Negroes, is a nonpartisan civil rights organization based in New York City that advocates on behalf of African Americans and against racial discrimination in the United States. It is the oldest and largest...

from a relatively passive civil rights

Civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from unwarranted infringement by governments and private organizations, and ensure one's ability to participate in the civil and political life of the state without discrimination or repression.Civil rights include...

organization into one that aggressively fought for equitable access to socioeconomic opportunity for the historically disenfranchised.

Early Life and career

Young was born in Shelby CountyShelby County, Kentucky

Shelby County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of 2010, the population was 42,074. Its name is in honor of Isaac Shelby, the first Governor of Kentucky. Its county seat is Shelbyville...

, Kentucky

Kentucky

The Commonwealth of Kentucky is a state located in the East Central United States of America. As classified by the United States Census Bureau, Kentucky is a Southern state, more specifically in the East South Central region. Kentucky is one of four U.S. states constituted as a commonwealth...

, on July 31, 1921 to educated parents. His father was the president of the Lincoln Institute, which was where Whitney was raised and educated. Whitney's mother, Laura Young, was the first female postmistress in Kentucky, the first African-American postmistress in Kentucky, and the second in the United States.

Young earned a bachelor of science degree from Kentucky State University

Kentucky State University

Kentucky State University is a four-year institution of higher learning, located in Frankfort, Kentucky, United States, the Commonwealth's capital. The school is an historically black university, which desegregated in 1954...

, a historically black institution. At Kentucky State, Young was a member of Alpha Phi Alpha

Alpha Phi Alpha

Alpha Phi Alpha is the first Inter-Collegiate Black Greek Letter fraternity. It was founded on December 4, 1906 at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. Its founders are known as the "Seven Jewels". Alpha Phi Alpha developed a model that was used by the many Black Greek Letter Organizations ...

fraternity.

During World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, Young was trained in electrical engineering at MIT

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology is a private research university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts. MIT has five schools and one college, containing a total of 32 academic departments, with a strong emphasis on scientific and technological education and research.Founded in 1861 in...

. He was then assigned to a road construction crew of black soldiers supervised by Southern white officers. After just three weeks, he was promoted from private to first sergeant, creating hostility on both sides. Despite the tension, Young was able to mediate effectively between his white officers and black soldiers angry at their poor treatment. This situation propelled Young into a career in race relations.

After the war, Young joined his wife, Margaret, at the University of Minnesota

University of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota, Twin Cities is a public research university located in Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota, United States. It is the oldest and largest part of the University of Minnesota system and has the fourth-largest main campus student body in the United States, with 52,557...

, where he earned a Masters Degree in social work in 1947 and volunteered for the St. Paul

Saint Paul, Minnesota

Saint Paul is the capital and second-most populous city of the U.S. state of Minnesota. The city lies mostly on the east bank of the Mississippi River in the area surrounding its point of confluence with the Minnesota River, and adjoins Minneapolis, the state's largest city...

branch of the National Urban League

National Urban League

The National Urban League , formerly known as the National League on Urban Conditions Among Negroes, is a nonpartisan civil rights organization based in New York City that advocates on behalf of African Americans and against racial discrimination in the United States. It is the oldest and largest...

. He was then appointed to a leadership position in that branch.

In 1950, Young became president of the National Urban League's Omaha, Nebraska

Omaha, Nebraska

Omaha is the largest city in the state of Nebraska, United States, and is the county seat of Douglas County. It is located in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about 20 miles north of the mouth of the Platte River...

chapter. In that position, he helped get black workers into jobs previously reserved for whites. Under his leadership, the chapter tripled its number of paying members.

In his next position as dean of social work at Atlanta University

Clark Atlanta University

Clark Atlanta University is a private, historically black university in Atlanta, Georgia. It was formed in 1988 with the consolidation of Clark College and Atlanta University...

, Young supported alumni in their boycott

Boycott

A boycott is an act of voluntarily abstaining from using, buying, or dealing with a person, organization, or country as an expression of protest, usually for political reasons...

of the Georgia Conference of Social Welfare. The organization had a poor record of placing African Americans in good jobs. In 1960, Young was awarded a Rockefeller Foundation

Rockefeller Foundation

The Rockefeller Foundation is a prominent philanthropic organization and private foundation based at 420 Fifth Avenue, New York City. The preeminent institution established by the six-generation Rockefeller family, it was founded by John D. Rockefeller , along with his son John D. Rockefeller, Jr...

grant for a postgraduate year at Harvard University

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States, established in 1636 by the Massachusetts legislature. Harvard is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States and the first corporation chartered in the country...

. In the same year, he joined the NAACP and rose to become state president.

Young was a close friend of Roy Wilkins

Roy Wilkins

Roy Wilkins was a prominent civil rights activist in the United States from the 1930s to the 1970s. Wilkins' most notable role was in his leadership of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People ....

, who was the executive director

Executive director

Executive director is a term sometimes applied to the chief executive officer or managing director of an organization, company, or corporation. It is widely used in North American non-profit organizations, though in recent decades many U.S. nonprofits have adopted the title "President/CEO"...

for the NAACP in the 1960s.

Executive Director of National Urban League

In 1961, at age 40, Young became Executive Director of the National Urban LeagueNational Urban League

The National Urban League , formerly known as the National League on Urban Conditions Among Negroes, is a nonpartisan civil rights organization based in New York City that advocates on behalf of African Americans and against racial discrimination in the United States. It is the oldest and largest...

. Within four years he expanded the organization from 38 employees to 1,600 employees; and from an annual budget of $325,000 to one of $6,100,000. He was President of the National Urban League

National Urban League

The National Urban League , formerly known as the National League on Urban Conditions Among Negroes, is a nonpartisan civil rights organization based in New York City that advocates on behalf of African Americans and against racial discrimination in the United States. It is the oldest and largest...

from 1961 until his death in 1971.

The Urban League had traditionally been a cautious and moderate organization with many white members. During Young's ten-year tenure at the League, he brought the organization to the forefront of the American Civil Rights Movement. He both greatly expanded its mission and kept the support of influential white business and political leaders. As part of the League's new mission, Young initiated programs like "Street Academy", an alternative education system to prepare high school dropouts for college, and "New Thrust", an effort to help local black leaders identify and solve community problems.

Young also pushed for federal aid to cities, proposing a domestic "Marshall Plan

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan was the large-scale American program to aid Europe where the United States gave monetary support to help rebuild European economies after the end of World War II in order to combat the spread of Soviet communism. The plan was in operation for four years beginning in April 1948...

". This plan, which called for $145 billion in spending over 10 years, was partially incorporated into President

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

Lyndon B. Johnson's

Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson , often referred to as LBJ, was the 36th President of the United States after his service as the 37th Vice President of the United States...

War on Poverty

War on Poverty

The War on Poverty is the unofficial name for legislation first introduced by United States President Lyndon B. Johnson during his State of the Union address on January 8, 1964. This legislation was proposed by Johnson in response to a national poverty rate of around nineteen percent...

. Young described his proposals for integration, social programs, and affirmative action in his two books, To Be Equal (1964) and Beyond Racism (1969).

As executive director of the League, Young pushed major corporations to hire more blacks. In doing so, he fostered close relationships with CEOs such as Henry Ford II

Henry Ford II

Henry Ford II , commonly known as "HF2" and "Hank the Deuce", was the son of Edsel Ford and grandson of Henry Ford...

, leading some blacks to charge that Young had sold out to the white establishment. Young denied these charges and stressed the importance of working within the system to effect change. Still, Young was not afraid to take a bold stand in favor of civil rights. For instance, in 1963, Young was one of the organizers of the March on Washington

March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom was the largest political rally for human rights in United States history and called for civil and economic rights for African Americans. It took place in Washington, D.C. on Wednesday, August 28, 1963. Martin Luther King, Jr...

despite the opposition of many white business leaders.

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald "Jack" Kennedy , often referred to by his initials JFK, was the 35th President of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963....

, Johnson

Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson , often referred to as LBJ, was the 36th President of the United States after his service as the 37th Vice President of the United States...

, and Nixon

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon was the 37th President of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. The only president to resign the office, Nixon had previously served as a US representative and senator from California and as the 36th Vice President of the United States from 1953 to 1961 under...

. In 1968, representatives of President-elect Richard Nixon

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon was the 37th President of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. The only president to resign the office, Nixon had previously served as a US representative and senator from California and as the 36th Vice President of the United States from 1953 to 1961 under...

tried to interest Young in a Cabinet

United States Cabinet

The Cabinet of the United States is composed of the most senior appointed officers of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States, which are generally the heads of the federal executive departments...

post, but Young refused, believing that he could accomplish more through the Urban League.

Young had a particularly close relationship with President Johnson

Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson , often referred to as LBJ, was the 36th President of the United States after his service as the 37th Vice President of the United States...

, and in 1969, Johnson

Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson , often referred to as LBJ, was the 36th President of the United States after his service as the 37th Vice President of the United States...

honored Young with the highest civilian award, the Presidential Medal of Freedom

Presidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is an award bestowed by the President of the United States and is—along with thecomparable Congressional Gold Medal bestowed by an act of U.S. Congress—the highest civilian award in the United States...

. Young, in turn, was impressed by Johnson's commitment to civil rights.

Despite their close personal relationship, Young was frustrated by Johnson's attempts to use him to balance Martin Luther King's

Martin Luther King, Jr.

Martin Luther King, Jr. was an American clergyman, activist, and prominent leader in the African-American Civil Rights Movement. He is best known for being an iconic figure in the advancement of civil rights in the United States and around the world, using nonviolent methods following the...

opposition to the increasingly unpopular Vietnam War

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War was a Cold War-era military conflict that occurred in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. This war followed the First Indochina War and was fought between North Vietnam, supported by its communist allies, and the government of...

. Young publicly supported Johnson's war policy, but came to oppose the war after the end of Johnson's presidency.

In 1968, Herman B. Furguson and Arthur Harris were convicted of conspiring to murder Young as part of what was described as a "black revolutionary plot." The trial took place in the New York State Supreme Court, with Justice Paul Balsam

Paul Balsam

Paul Balsam was a justice on the New York State Supreme Court from January 1, 1965 until his death in 1972. He was born, and lived throughout his life, in Ozone Park, Queens...

presiding.

Leadership at the National Association of Social Workers (NASW)

Young served as President of the National Association of Social Workers, (NASW) from 1969-71. He took office at a time of fiscal instability in the association and uncertainty about President Nixon’s continuing commitment to the “War on Poverty” and to ending the war in Vietnam. At the 1969 NASW Delegate Assembly Young stated,- “First of all, I think the country is in deep trouble. We, as a country have blazed unimagined trails technologically and industrially. We have not yet begun to pioneer in those things that are human and social… I think that social work is uniquely equipped to play a major role in this social and human renaissance of our society, which will, if successful, lead to its survival, and if it is unsuccessful, will lead to its justifiable death.” (NASW News, May 1969).

Mr. Young spent his tenure as President of NASW ensuring that the profession kept pace with the troubling social and human challenges it was facing. NASW News articles document his call to action for social workers to address social welfare through poverty reduction, race reconciliation, and putting an end to the War in Vietnam. In the NASW News, July 1970, he challenged his professional social work organization to take leadership in the national struggle for social welfare:

- “The crisis in health and welfare services in our nation today highlights for NASW what many of us have been stressing for a long time: inherent in the responsibility for leadership in social welfare is responsibility for professional action. They are not disparate aspects of social work but merely two faces of the same coin to be spent on more and better services for the people who need our help. It is out of our belief in this broad definition of responsibility for social welfare that NASW is taking leadership in the efforts to reorder our nation’s priorities and future direction, and is calling on social workers everywhere to do the same.”

The NASW News, May 1971, tribute to Young noted that “As usual Whitney Young was preparing to do battle on the major issues and programs facing the association and the nation. And he was doing it with his usual aplomb-dapper, self-assured, ready to deal with the “power” people to bring about change for the powerless.”

Mr. Young was also well known in the profession of Social Work for being the Dean of the school of Social Work at Clark Atlanta University

Clark Atlanta University

Clark Atlanta University is a private, historically black university in Atlanta, Georgia. It was formed in 1988 with the consolidation of Clark College and Atlanta University...

, which now bears his name. The school has a solid history of Social work, graduating leaders in the profession and having created and founded the "Afro-Centric" prospective of Social Work, a frequently used theory practice in urban areas.

In his last column as President for NASW, Young wrote, “whatever we do we should tell the public what we are doing and why. They have to hear from social workers as much as they hear from reporters and government officials.”

Death

On March 11, 1971, Whitney Young drowned while swimming with friends in LagosLagos

Lagos is a port and the most populous conurbation in Nigeria. With a population of 7,937,932, it is currently the third most populous city in Africa after Cairo and Kinshasa, and currently estimated to be the second fastest growing city in Africa...

, Nigeria

Nigeria

Nigeria , officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a federal constitutional republic comprising 36 states and its Federal Capital Territory, Abuja. The country is located in West Africa and shares land borders with the Republic of Benin in the west, Chad and Cameroon in the east, and Niger in...

, where he was attending a conference sponsored by the African-American Institute. President

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

Nixon

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon was the 37th President of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. The only president to resign the office, Nixon had previously served as a US representative and senator from California and as the 36th Vice President of the United States from 1953 to 1961 under...

sent a plane to Nigeria to collect Young's body and traveled to Kentucky

Kentucky

The Commonwealth of Kentucky is a state located in the East Central United States of America. As classified by the United States Census Bureau, Kentucky is a Southern state, more specifically in the East South Central region. Kentucky is one of four U.S. states constituted as a commonwealth...

to deliver the eulogy

Eulogy

A eulogy is a speech or writing in praise of a person or thing, especially one recently deceased or retired. Eulogies may be given as part of funeral services. However, some denominations either discourage or do not permit eulogies at services to maintain respect for traditions...

at Young's funeral.

Legacy

Whitney Young's legacy, as President Nixon stated in his eulogy, was that "he knew how to accomplish what other people were merely for." Young's work was instrumental in breaking down the barriers of segregation and inequality that held back African Americans.Hundreds of schools and other sites are named for Young. For instance, in 1973, the East Capitol Street Bridge in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

, was renamed the Whitney Young Memorial Bridge

Whitney Young Memorial Bridge

The Whitney Young Memorial Bridge is a bridge that carries East Capitol Street across the Anacostia River in Washington, D.C. Finished in 1955, it was originally called the East Capitol Street Bridge. It was renamed for civil rights activist Whitney Young in early 1974...

in his honor.

Clark Atlanta University

Clark Atlanta University

Clark Atlanta University is a private, historically black university in Atlanta, Georgia. It was formed in 1988 with the consolidation of Clark College and Atlanta University...

named its School of Social Work, where Whitney Young served as Dean, in Young's honor. The Whitney M. Young School of Social Work is well-known for founding the "Afro-Centric" prospective of social work.

The Boy Scouts of America

Boy Scouts of America

The Boy Scouts of America is one of the largest youth organizations in the United States, with over 4.5 million youth members in its age-related divisions...

created the Whitney M. Young Jr. Service Award to recognize outstanding services by an adult individual or an organization for demonstrated involvement in the development and implementation of Scouting opportunities for youth from rural or low-income urban backgrounds.

Whitney Young High School in Chicago

Chicago

Chicago is the largest city in the US state of Illinois. With nearly 2.7 million residents, it is the most populous city in the Midwestern United States and the third most populous in the US, after New York City and Los Angeles...

was named after him. Whitney M. Young High School

Whitney M. Young High School

Whitney M. Young Gifted & Talented Leadership Academy, , is a selective-enrollment public school in Cleveland, Ohio, notable as the city's first public gifted and talented school.. Named after Whitney M...

in Cleveland

Cleveland, Ohio

Cleveland is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and is the county seat of Cuyahoga County, the most populous county in the state. The city is located in northeastern Ohio on the southern shore of Lake Erie, approximately west of the Pennsylvania border...

, Ohio

Ohio

Ohio is a Midwestern state in the United States. The 34th largest state by area in the U.S.,it is the 7th‑most populous with over 11.5 million residents, containing several major American cities and seven metropolitan areas with populations of 500,000 or more.The state's capital is Columbus...

was also named after him.

Young's birthplace (Whitney Young Birthplace and Museum

Whitney Young Birthplace and Museum

The Whitney Young Birthplace and Museum was the birthplace and childhood home of Whitney M. Young, Jr., an American civil rights leader. The simple wooden house in Shelby County, Kentucky, near Louisville, is on the campus of the former Lincoln Institute, an all-black high school that Young...

) in Shelby County, Kentucky is a designated National Historic Landmark

National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark is a building, site, structure, object, or district, that is officially recognized by the United States government for its historical significance...

, with a museum dedicated to Young's life and achievements.

Young was honored on a United States Postage stamp as part of its on-going Black Heritage series.

In 1973, The African American MBA Association at The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania held its first Annual Whitney M. Young Jr. Memorial Conference. After 38 years, the Whitney M. Young Jr. Memorial Conference is the longest student-run conference held at The Wharton School.

Quotes

"Every man is our brother, and every man’s burden is our own. Where poverty exists, all are poorer. Where hate flourishes, all are corrupted. Where injustice reins, all are unequal.""I am not anxious to be the loudest voice or the most popular. But I would like to think that at a crucial moment, I was an effective voice of the voiceless, an effective hope of the hopeless."

"You can holler, protest, march, picket and demonstrate, but somebody must be able to sit in on the strategy conferences and plot a course. There must be strategies, the researchers, the professionals to carry out the program. That's our role."

"Black Power simply means: Look at me, I'm here. I have dignity. I have pride. I have roots. I insist, I demand that I participate in those decisions that affect my life and the lives of my children. It means that I am somebody."

"Liberalism seems to be related to the distance people are from the problem."

"I'd rather be prepared for an opportunity that never comes than have an opportunity come and I am not prepared."

In Movies

The upcoming documentary, One Handshake at a Time, chronicles Young's rise from segregated Kentucky to the national movement for civil rights. The film includes archival footage, photos and interviews compiled by Young's niece, award-winning journalist Bonnie Boswell Hamilton. Interviews include Henry Louis Gates, Jr.Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Henry Louis “Skip” Gates, Jr., is an American literary critic, educator, scholar, writer, editor, and public intellectual. He was the first African American to receive the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Fellowship. He has received numerous honorary degrees and awards for his teaching, research, and...

, Ossie Davis

Ossie Davis

Ossie Davis was an American film actor, director, poet, playwright, writer, and social activist.-Early years:...

, Julian Bond

Julian Bond

Horace Julian Bond , known as Julian Bond, is an American social activist and leader in the American civil rights movement, politician, professor, and writer. While a student at Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia, during the early 1960s, he helped found the Student Nonviolent Coordinating...

, Roy Innis

Roy Innis

Roy Emile Alfredo Innis is an African American civil rights activist. He has been National Chairman of the Congress of Racial Equality since his election to the position in 1968....

, Vernon Jordan, Donald Rumsfeld

Donald Rumsfeld

Donald Henry Rumsfeld is an American politician and businessman. Rumsfeld served as the 13th Secretary of Defense from 1975 to 1977 under President Gerald Ford, and as the 21st Secretary of Defense from 2001 to 2006 under President George W. Bush. He is both the youngest and the oldest person to...

, and Dorothy Height

Dorothy Height

Dorothy Irene Height was an American administrator, educator, and social activist. She was the president of the National Council of Negro Women for forty years, and was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1994, and the Congressional Gold Medal in 2004.-Early life:Height was born in...

.