Medical community of ancient Rome

Encyclopedia

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

and the Roman Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

.

Background

Medical services of the late Roman RepublicRoman Republic

The Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

and early Roman Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

were mainly imports from the civilization of Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

, at first through Greek-influenced Etruscan

Etruscan civilization

Etruscan civilization is the modern English name given to a civilization of ancient Italy in the area corresponding roughly to Tuscany. The ancient Romans called its creators the Tusci or Etrusci...

society and Greek colonies

Magna Graecia

Magna Græcia is the name of the coastal areas of Southern Italy on the Tarentine Gulf that were extensively colonized by Greek settlers; particularly the Achaean colonies of Tarentum, Crotone, and Sybaris, but also, more loosely, the cities of Cumae and Neapolis to the north...

placed directly in Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

, and then through Greeks enslaved

Slavery in ancient Rome

The institution of slavery in ancient Rome played an important role in society and the Roman economy. Besides manual labor on farms and in mines, slaves performed many domestic services and a variety of other tasks, such as accounting...

during the Roman conquest of Greece, Greeks invited to Rome, or Greek knowledge imparted to Roman citizens visiting or being educated in Greece. A perusal of the names of Roman physicians will show that the majority are wholly or partly Greek and that many of the physicians were of servile origin.

The servility stigma came from the accident of a more medically advanced society being conquered by a lesser. One of the cultural ironies of these circumstances is that free men sometimes found themselves in service to the enslaved professional or dignitary, or the power of the state was entrusted to foreigners who had been conquered in battle and were technically slaves. In Greek society, physicians tended to be regarded as noble. Asclepius

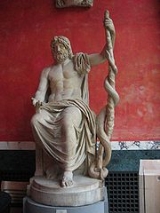

Asclepius

Asclepius is the God of Medicine and Healing in ancient Greek religion. Asclepius represents the healing aspect of the medical arts; his daughters are Hygieia , Iaso , Aceso , Aglæa/Ægle , and Panacea...

in the Iliad is noble.

Public medicine

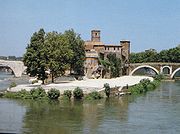

Tiber Island

The Tiber Island , is a boat-shaped island which has long been associated with healing. It is an ait, and is one of the two islands in the Tiber river, which runs through Rome; the other one, much larger, is near the mouth. The island is located in the southern bend of the Tiber. It is...

. In 293 BCE some officials consulted the Sibylline Books

Sibylline Books

The Sibylline Books or Libri Sibyllini were a collection of oracular utterances, set out in Greek hexameters, purchased from a sibyl by the last king of Rome, Tarquinius Superbus, and consulted at momentous crises through the history of the Republic and the Empire...

concerning measures to be taken against the plague and were advised to bring Aesculapius from Epidaurus

Epidaurus

Epidaurus was a small city in ancient Greece, at the Saronic Gulf. Two modern towns bear the name Epidavros : Palaia Epidavros and Nea Epidavros. Since 2010 they belong to the new municipality of Epidavros, part of the peripheral unit of Argolis...

to Rome. The sacred serpent from Epidaurus was conferred ritually on the new temple, or, in some accounts, the serpent escaped from the ship and swam to the island. Baths have been found there as well as votive offerings (donaria) in the shape of specific organs.

In classical times the center covered the entire island and included a long-term recovery center. The emperor Claudius

Claudius

Claudius , was Roman Emperor from 41 to 54. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, he was the son of Drusus and Antonia Minor. He was born at Lugdunum in Gaul and was the first Roman Emperor to be born outside Italy...

had a law passed granting freedom to slaves who had been sent to the institution for cure but were abandoned there. This law probably facilitated state disposition of the patients and recovery of the beds they occupied. The details are not available.

Apollo

Apollo is one of the most important and complex of the Olympian deities in Greek and Roman mythology...

medicus (“the healer”).. There was also a temple to salus (“health”) on the Mons Salutaris, a spur of the Quirinal. There is no record that these earlier temples possessed the medical facilities associated with an Aesculapium; in that case, the later decision to bring them in presupposes a new understanding that scientific measures could be taken against plague. The memorable description of plague at Athens during the Peloponnesian War

Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War, 431 to 404 BC, was an ancient Greek war fought by Athens and its empire against the Peloponnesian League led by Sparta. Historians have traditionally divided the war into three phases...

(430 BCE) by Thucydides

Thucydides

Thucydides was a Greek historian and author from Alimos. His History of the Peloponnesian War recounts the 5th century BC war between Sparta and Athens to the year 411 BC...

does not mention any measures at all to relieve those stricken with it. The dying were allowed to accumulate at the wells, which they contaminated, and the deceased to pile up there. At Rome, Cicero

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero , was a Roman philosopher, statesman, lawyer, political theorist, and Roman constitutionalist. He came from a wealthy municipal family of the equestrian order, and is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.He introduced the Romans to the chief...

criticized the worship of evil powers, such as Febris (“Fever”), Dea Mefitis (“Malaria”), Dea Angerona (“Sore Throat”) and Dea Scabies (“Rash”).

The medical art in early Rome was the responsibility of the pater familias, or patriarch. The last known public advocate of this point of view were the railings of Marcus Cato

Cato the Elder

Marcus Porcius Cato was a Roman statesman, commonly referred to as Censorius , Sapiens , Priscus , or Major, Cato the Elder, or Cato the Censor, to distinguish him from his great-grandson, Cato the Younger.He came of an ancient Plebeian family who all were noted for some...

against Greek physicians and his insistence on passing on home remedies to his son.

The importation of the Aesculapium established medicine in the public domain. There is no record of fees being collected for a stay at one of them, at Rome or elsewhere. The expense of an Aesculapium must have been defrayed in the same way as all temple expenses: individuals vowed to perform certain actions or contribute a certain amount if certain events happened, some of which were healings. Such a system amounts to gradated contributions by income, as the contributor could only vow what he could provide. The building of a temple and its facilities on the other hand was the responsibility of the magistrates. The funds came from the state treasury or from taxes.

Private medicine

A second signal act marked the start of sponsorship of private medicine by the state as well. In the year 219 BCE (Lucius Aemilius PaullusLucius Aemilius Paullus

Lucius Aemilius Paullus was the name of several ancient Romans of the patrician gens Aemilia.Notable men with this name include:* Lucius Aemilius Paullus * Lucius Aemilius Paulus Macedonicus, his son...

and Marcus Livius Salinator

Marcus Livius Salinator

Marcus Livius Drusus Salinator , the son of Marcus , was a Roman consul who fought in both the First Punic wars and Second Punic wars most notably during the Battle of Zama....

were consuls), a vulnerarius, or surgeon, Archagathus, visited Rome from the Peloponnesus and was asked to stay. The state conferred citizenship on him and purchased him a taberna, or shop, near the compitium Acilii (a crossroads), which became the first officina medica.

The doctor necessarily had many assistants. Some prepared and vended medicines and tended the herb garden. There were pharmacopolae (note the female ending), unguentarii and aromatarii, all of which names are easily understood by the English reader. Others attended the doctor when required (the capsarii; they prepared and carried the doctor’s capsa, or bag.). Jerome Carcopino

Jérôme Carcopino

Jérôme Carcopino was a French historian and author. He was the fifteen member elected to occupy seat 3 of the Académie française in 1955.-Biography:...

’s study of occupational names in the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum

The Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum is a comprehensive collection of ancient Latin inscriptions. It forms an authoritative source for documenting the surviving epigraphy of classical antiquity. Public and personal inscriptions throw light on all aspects of Roman life and history...

turned up 51 medici, 4 medicae (female doctors), an obstetrix (“midwife”) and a nutrix (“nurse”) in the city of Rome. These numbers, of course, are at best proportional to the true populations, which were many times greater.

At the bottom of the scale were the ubiquitous discentes (“those learning”), or medical apprentices. Roman doctors of any stature combed the population for persons in any social setting who had an interest in and ability for practicing medicine. On the one hand the doctor used their services unremittingly. On the other they were treated like members of the family; i.e., they came to stay with the doctor and when they left they were themselves doctors. The best doctors were the former apprentices of the Aesculapia, who, in effect, served residencies there.

Medical values

The Romans valued a state of valetudo, salus or sanitas. They began their correspondence with the salutation si vales valeo, “if you are well, I am” and ended it with salve, “be healthy.” The Indo-EuropeanProto-Indo-European language

The Proto-Indo-European language is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European languages, spoken by the Proto-Indo-Europeans...

roots are *wal-, “be strong”, and *sol-, “whole”.

They understood generally that conditions of strength and wholeness were to some degree perpetuated by right living. The Hippocratic oath obliges doctors to live rightly (setting an example). The first cause thought of when people got sick was that they did not live rightly. Vegetius

Vegetius

Publius Flavius Vegetius Renatus, commonly referred to simply as Vegetius, was a writer of the Later Roman Empire. Nothing is known of his life or station beyond what he tells us in his two surviving works: Epitoma rei militaris , and the lesser-known Digesta Artis Mulomedicinae, a guide to...

’ brief section on the health of a Roman legion

Roman legion

A Roman legion normally indicates the basic ancient Roman army unit recruited specifically from Roman citizens. The organization of legions varied greatly over time but they were typically composed of perhaps 5,000 soldiers, divided into maniples and later into "cohorts"...

states only that a legion can avoid disease by staying out of malarial swamps, working out regularly and living a healthy life.

Despite their best efforts people from time to time did become aeger, “sick”. They languished, had nausea (words of Roman extraction) or “fell” (incidere) in morbum. They were vexed and dolorous. At that point they were in need of the medica res, the men skilled in the ars medicus, who would curare morbum, “have a care for the disease”, who went by the name of medicus or medens. The root is *med-, “measure”. The medicus prescribed medicina or regimina as measures against the disease.

The physician

The next step was to secure the cura of a medicus. If the patient was too sick to move one sent for a clinicus, who went to the clinum or couch of the patient. Of higher status were the chirurgii (which became the English word surgeonSurgeon

In medicine, a surgeon is a specialist in surgery. Surgery is a broad category of invasive medical treatment that involves the cutting of a body, whether human or animal, for a specific reason such as the removal of diseased tissue or to repair a tear or breakage...

), from Greek cheir (hand) and ourgon (work). In addition were the eye doctor, ocularius, the ear doctor, auricularius, and the doctor of snakebites, the marsus.

Fees

That the poor paid a minimal fee for the visit of a medicus is indicated by a wisecrack in PlautusPlautus

Titus Maccius Plautus , commonly known as "Plautus", was a Roman playwright of the Old Latin period. His comedies are the earliest surviving intact works in Latin literature. He wrote Palliata comoedia, the genre devised by the innovator of Latin literature, Livius Andronicus...

: "It was less than a nummus

Roman currency

The Roman currency during most of the Roman Republic and the western half of the Roman Empire consisted of coins including the aureus , the denarius , the sestertius , the dupondius , and the as...

." Many anecdotes exist of doctors negotiating fees with wealthy patients and refusing to prescribe a remedy if agreement was not reached. Pliny says

- ”I will not accuse the medical art of the avarice even of its professors, the rapacious bargains made with their patients while their fate is trembling in the balance, …”

The fees charged were on a sliding scale according to assets. The physicians of the rich were themselves rich. For example, Antonius Musa treated Augustus

Augustus

Augustus ;23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14) is considered the first emperor of the Roman Empire, which he ruled alone from 27 BC until his death in 14 AD.The dates of his rule are contemporary dates; Augustus lived under two calendars, the Roman Republican until 45 BC, and the Julian...

’ nervous symptoms with cold baths and drugs. He was not only set free but he became Augustus’ physician. He received a salary of 300,000 sesterces. There is no evidence that he was other than a private physician; that is, he was not working for the Roman government.

Legal responsibility

Doctors were generally exempt from prosecution for their mistakes. Some writers complain of legal murder. However, holding the powerful up to exorbitant fees ran the risk of retaliation. Pliny reports that the emperor ClaudiusClaudius

Claudius , was Roman Emperor from 41 to 54. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, he was the son of Drusus and Antonia Minor. He was born at Lugdunum in Gaul and was the first Roman Emperor to be born outside Italy...

fined a physician, Alcon, 180 million sesterces and exiled him to Gaul, but that on his return he made the money back in just a few years. Pliny does not say why the physician was exiled, but the blow against the man was struck on his pocketbook. He could make no such income in Gaul.

This immunity applied only to mistakes made in the treatment of free men. By chance a law existed at Rome, the Lex Aquilia

Lex Aquilia

The lex Aquilia was a Roman law which provided compensation to the owners of property injured by someone's fault.- The provisions of the Lex Aquilia :...

, passed about 286 BCE, which allowed the owners of slaves and animals to seek remedies for damage to their property, either malicious or negligent. Litigants used this law to proceed against the negligence of medici, such as the performance of an operation on a slave by an untrained surgeon resulting in death or other damage.

Social position

While encouraging and supporting the public and private practice of medicine, the Roman government tended to suppress organizations of medici in society. The constitution provided for the formation of occupational collegia, or guilds. The consuls and the emperors treated these ambivalently. Sometimes they were permitted; more often they were made illegal and were suppressed. The medici formed collegia, which had their own centers, the Scholae Medicorum, but they never amounted to a significant social force. They were regarded as subversive along with all the other collegia.Doctors were nevertheless very influential. They liked to write. Compared to the number of books written, not many have survived; for example, Tiberius Claudius Menecrates composed 150 medical works, of which only a few fragments remain. Some that did remain almost in entirety are the works of Galen

Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus , better known as Galen of Pergamon , was a prominent Roman physician, surgeon and philosopher...

, Celsus

Aulus Cornelius Celsus

Aulus Cornelius Celsus was a Roman encyclopedist, known for his extant medical work, De Medicina, which is believed to be the only surviving section of a much larger encyclopedia. The De Medicina is a primary source on diet, pharmacy, surgery and related fields, and it is one of the best sources...

, Hippocrates

Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Cos or Hippokrates of Kos was an ancient Greek physician of the Age of Pericles , and is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history of medicine...

and the herbal expert, Pedanius Dioscorides

Pedanius Dioscorides

Pedanius Dioscorides was a Greek physician, pharmacologist and botanist, the author of a 5-volume encyclopedia about herbal medicine and related medicinal substances , that was widely read for more than 1,500 years.-Life:...

. The Natural History (Naturalis Historia

Naturalis Historia

The Natural History is an encyclopedia published circa AD 77–79 by Pliny the Elder. It is one of the largest single works to have survived from the Roman Empire to the modern day and purports to cover the entire field of ancient knowledge, based on the best authorities available to Pliny...

, typically abbreviated to NH) of Pliny the Elder

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus , better known as Pliny the Elder, was a Roman author, naturalist, and natural philosopher, as well as naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and personal friend of the emperor Vespasian...

became a paradigm for all subsequent works like it and gave its name to the topic, although Pliny was not a physician himself.

Republican

The state of the military medical corps before AugustusAugustus

Augustus ;23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14) is considered the first emperor of the Roman Empire, which he ruled alone from 27 BC until his death in 14 AD.The dates of his rule are contemporary dates; Augustus lived under two calendars, the Roman Republican until 45 BC, and the Julian...

is unclear. Corpsmen certainly existed at least for the administration of first aid and were enlisted soldiers rather than civilians. The commander of the legion was held responsible for removing the wounded from the field and insuring that they got sufficient care and time to recover. He could quarter troops in private domiciles if he thought necessary. Authors who have written of Roman military activities before Augustus, such as Livy

Livy

Titus Livius — known as Livy in English — was a Roman historian who wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people. Ab Urbe Condita Libri, "Chapters from the Foundation of the City," covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome well before the traditional foundation in 753 BC...

, mention that wounded troops retired to population centers to recover.

Imperial

The army of the early empire was sharply and qualitatively different. Augustus defined a permanent professional army by setting the enlistment at 16 years (with an additional 4 for reserve obligations), and establishing a special military fund, the aerarium militare, imposing a 5% inheritance tax and 1% auction sales tax to pay for it. From it came bonus payments to retiring soldiers amounting to several years’ salary. It could also have been used to guarantee regular pay. Previously legions had to rely on booty.If military careers were now possible, so were careers for military specialists, such as medici. Under Augustus for the first time occupational names of officers and functions began to appear in inscriptions. The valetudinaria, or military versions of the aesculapia (the names mean the same thing) became features of permanent camps. Caches of surgical instruments have been found in some of them. From this indirect evidence it is possible to conclude to the formation of an otherwise unknown permanent medical corps.

In the early empire one finds milites medici who were immunes (“exempt”) from other duties. Some were staff of the hospital, which Pseudo-Hyginus

Pseudo-Hyginus

De Munitionibus Castrorum is a work by an unknown author. Due to this work formerly being attributed to Hyginus Gromaticus, its author is conventionally called "Pseudo-Hyginus". This work is the most detailed description that survives about Roman military camps De Munitionibus Castrorum (About the...

mentions as being set apart from other buildings so that the patients can rest. The hospital administrator was an optio valetudinarii. The orderlies aren’t generally mentioned, but they must have existed, as the patients needed care and the doctors had more important duties. Perhaps they were servile or civilians, not worth mentioning. There were some noscomi, male nurses not in the army. Or, they could have been the milites medici. The latter term might be any military medic or it might be orderlies detailed from the legion. There were also medici castrorum. Not enough information survives in the sources to say for certain what distinctions existed, if any.

The army of Augustus featured a standardized officer corps, described by Vegetius

Vegetius

Publius Flavius Vegetius Renatus, commonly referred to simply as Vegetius, was a writer of the Later Roman Empire. Nothing is known of his life or station beyond what he tells us in his two surviving works: Epitoma rei militaris , and the lesser-known Digesta Artis Mulomedicinae, a guide to...

. Among them were the Ordinarii, the officers of an Ordo or rank. In an acies triplex there were three such ordines, the centuries (companies) of which were commanded by centurions. The Ordinarii were therefore of the rank of a centurion but did not necessarily command one if they were staff.

The term medici ordinarii in the inscriptions must refer to the lowest ranking military physicians. No doctor was in any sense “ordinary”. They were to be feared and respected, just as they are today. During his reign, Augustus finally conferred the dignitas equestris, or social rank of knight, on all physicians, public or private. They were then full citizens (in case there were any Hellenic questions) and could wear the rings of knights. In the army there was at least one other rank of physician, the medicus duplicarius, “medic at double pay”, and, as the legion had milites sesquiplicarii, "soldiers at 1.5 pay", perhaps the medics had that pay grade as well.

Augustan posts were named according to a formula containing the name of the rank and the unit commanded in the genitive case; e.g., the commander of a legion, who was a legate; that is, an officer appointed by the emperor, was the legatus legionis

Legatus legionis

Legatus legionis was a title awarded to legion commanders in Ancient Rome.-History:By the time of the Roman Republic, the term legatus delegated authority...

, “the legate of the legion.” Those posts worked pretty much as today; a man on his way up the cursus honorum (“ladder of offices”, roughly) would command a legion for a certain term and then move on.

The posts of medicus legionis and a medicus cohortis were most likely to be commanders of the medici of the legion and its cohorts. They were all under the praetor or camp commander, who might be the legatus but more often was under the legatus himself. There was, then, a medical corps associated with each camp. The cavalry alae (“wings”) and the larger ships all had their medical officers, the medici alarum and the medici triremis respectively.

Practice

As far as can be determined, the medical corps in battle worked as follows. Trajan's ColumnTrajan's Column

Trajan's Column is a Roman triumphal column in Rome, Italy, which commemorates Roman emperor Trajan's victory in the Dacian Wars. It was probably constructed under the supervision of the architect Apollodorus of Damascus at the order of the Roman Senate. It is located in Trajan's Forum, built near...

depicts medics on the battlefield bandaging soldiers. They were located just behind the standards; i.e., near the field headquarters. This must have been a field aid station, not necessarily the first, as the soldiers or corpsmen among the soldiers would have administered first aid before carrying their wounded comrades to the station. Some soldiers were designated to ride along the line on a horse picking up the wounded. They were paid by the number of men they rescued. Bandaging was performed by capsarii, who carried bandages (fascia) in their capsae, or bags.

From the aid station the wounded went by horse-drawn ambulance to other locations, ultimately to the camp hospitals in the area. There they were seen by the medici vulnerarii, or surgeons, the main type of military doctor. They were given a bed in the hospital if they needed it and one was available. The larger hospitals could administer 400-500 beds. If these were insufficient the camp commander probably utilized civilian facilities in the region or quartered them in the vici, “villages”, as in the republic.

A base hospital was quadrangular with barracks-like wards surrounding a central courtyard. On the outside of the quadrangle were private rooms for the patients. Although unacquainted with bacteria, Roman medical doctors knew about contagion and did their best to prevent it. Rooms were isolated, running water carried the waste away, and the drinking and washing water was tapped up the slope from the latrines.

Within the hospital were operating rooms, kitchens, baths, a dispensary, latrines, a mortuary and herb gardens, as doctors relied heavily on herbs for drugs. The medici could treat any wound received in battle, as long as the patient was alive. They operated or otherwise treated with scalpel

Scalpel

A scalpel, or lancet, is a small and extremely sharp bladed instrument used for surgery, anatomical dissection, and various arts and crafts . Scalpels may be single-use disposable or re-usable. Re-usable scalpels can have attached, resharpenable blades or, more commonly, non-attached, replaceable...

s, hooks, levers, drills, probes, forceps, catheter

Catheter

In medicine, a catheter is a tube that can be inserted into a body cavity, duct, or vessel. Catheters thereby allow drainage, administration of fluids or gases, or access by surgical instruments. The process of inserting a catheter is catheterization...

s and arrow-extractors on patients anesthetized with morphine

Morphine

Morphine is a potent opiate analgesic medication and is considered to be the prototypical opioid. It was first isolated in 1804 by Friedrich Sertürner, first distributed by same in 1817, and first commercially sold by Merck in 1827, which at the time was a single small chemists' shop. It was more...

(opium poppy

Opium poppy

Opium poppy, Papaver somniferum, is the species of plant from which opium and poppy seeds are extracted. Opium is the source of many opiates, including morphine , thebaine, codeine, papaverine, and noscapine...

extract) and scopolamine (henbane

Henbane

Henbane , also known as stinking nightshade or black henbane, is a plant of the family Solanaceae that originated in Eurasia, though it is now globally distributed.-Toxicity and historical usage:...

extract). Instruments were boiled before use. Wounds were washed in vinegar and stitched. Broken bones were placed in traction. There is, however, evidence of wider concerns. A vaginal speculum suggests gynecology was practiced, and an anal speculum implies knowledge that the size and condition of internal organs accessible through the orifices was an indication of health. They could extract eye cataract

Cataract

A cataract is a clouding that develops in the crystalline lens of the eye or in its envelope, varying in degree from slight to complete opacity and obstructing the passage of light...

s with a special needle. Operating room amphitheaters indicate that medical education was ongoing. Many have proposed that the knowledge and practices of the medici were not exceeded until the 20th century CE.

Regulation of medicine

By the late empire the state had taken more of a hand in regulating medicine. The law codes of the 4th century CE, such as the Codex TheodosianusCodex Theodosianus

The Codex Theodosianus was a compilation of the laws of the Roman Empire under the Christian emperors since 312. A commission was established by Theodosius II in 429 and the compilation was published in the eastern half of the Roman Empire in 438...

, paint a picture of a medical system enforced by the laws and the state apparatus. At the top was the equivalent of a surgeon general of the empire. He was by law a noble, a dux (duke) or a vicarius (vicar) of the emperor. He held the title of comes archiatorum, “count of the chief healers.” The Greek word iatros, “healer”, was higher-status than the Latin medicus.

Under the comes were a number of officials called the archiatri

Archiater

An archiater was a chief physician of a monarch, who typically retained several. At the Roman imperial court, their chief held the high rank and specific title of Comes archiatrorum.The term has also been used of chief physicians in communities...

, or more popularly the protomedici, supra medicos, domini medicorum or superpositi medicorum. They were paid by the state. It was their function to supervise all the medici in their districts; i.e., they were the chief medical examiners. Their families were exempt from taxes. They could not be prosecuted nor could troops be quartered in their homes.

The archiatri were divided into two groups:

- Archiatri sancti palatii, who were palace physicians

- Archiatri populares. They were required to provide for the poor; presumably, the more prosperous still provided for themselves.

The archiatri settled all medical disputes. Rome had 14 of them; the number in other communities varied from 5 to 10 depending on the population.

See also

- Medicine in ancient RomeMedicine in ancient RomeMedicine in ancient Rome combined various techniques using different tools and rituals. Ancient Roman medicine included a number of specializations such as internal medicine, ophthalmology and urology...

- Medicine in ancient GreeceMedicine in Ancient GreeceThe first known Greek medical school opened in Cnidus in 700 BC. Alcmaeon, author of the first anatomical work, worked at this school, and it was here that the practice of observing patients was established. Ancient Greek medicine revolved around the theory of humours...

- History of medicineHistory of medicineAll human societies have medical beliefs that provide explanations for birth, death, and disease. Throughout history, illness has been attributed to witchcraft, demons, astral influence, or the will of the gods...

- CastraCastraThe Latin word castra, with its singular castrum, was used by the ancient Romans to mean buildings or plots of land reserved to or constructed for use as a military defensive position. The word appears in both Oscan and Umbrian as well as in Latin. It may have descended from Indo-European to Italic...

External links

- Aesculapius Scholarly article in Smith’s ‘’Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology’’

- The Etymology of Medicine, article by Thelma Charin in the Bulletin of the Medical Library Association 1951 July; 39(3): 216–221.

- Surgical Instruments from Ancient Rome, article on the University of Virginia Health System Website.

- Hippocrates, article on the physician by Ann Hanson on the ‘’Medicina Antiqua’’ website. Republished on Bill Thayer's LacusCurtius site. Republished on Bill Thayer's LacusCurtius site. A collection of online articles (some reprints) on ancient medicine.Antique medicine website