Miles Davis

Encyclopedia

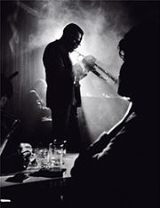

Miles Dewey Davis III was an American jazz

musician, trumpeter, bandleader

, and composer. Widely considered one of the most influential musicians of the 20th century, Miles Davis was, with his musical groups, at the forefront of several major developments in jazz music, including bebop

, cool jazz

, hard bop

, modal jazz

, and jazz fusion

.

On October 7, 2008, his 1959 album Kind of Blue

received its fourth platinum

certification from the Recording Industry Association of America

(RIAA), for shipments of at least four million copies in the United States. Miles Davis was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

in 2006. Davis was noted as "one of the key figures in the history of jazz".

On November 5, 2009, Rep. John Conyers

of Michigan sponsored a measure in the US House of Representatives to recognize and commemorate the album Kind of Blue

on its 50th anniversary. The measure also affirms jazz

as a national treasure and "encourages the United States government to preserve and advance the art form of jazz music." It passed, unanimously, with a vote of 409–0 on December 15, 2009.

, Illinois. His father, Dr. Miles Henry Davis

, was a dentist. In 1927 the family moved to East St. Louis, Illinois

. They also owned a substantial ranch in northern Arkansas

, where Davis learned to ride horses as a boy.

Davis' mother, Cleota Mae (Henry) Davis, wanted her son to learn the piano; she was a capable blues pianist but kept this fact hidden from her son. His musical studies began at 13, when his father gave him a trumpet and arranged lessons with local musician Elwood Buchanan

. Davis later suggested that his father's instrument choice was made largely to irk his wife, who disliked the trumpet's sound. Against the fashion of the time, Buchanan stressed the importance of playing without vibrato

; he was reported to have slapped Davis' knuckles every time he started using heavy vibrato

. Davis would carry his clear signature tone throughout his career. He once remarked on its importance to him, saying, "I prefer a round sound with no attitude in it, like a round voice with not too much tremolo

and not too much bass. Just right in the middle. If I can’t get that sound I can’t play anything." Clark Terry

was another important early influence.

By age 16, Davis was a member of the music society and playing professionally when not at school. At 17, he spent a year playing in Eddie Randle's band, the Blue Devils. During this time, Sonny Stitt

tried to persuade him to join the Tiny Bradshaw band, then passing through town, but Davis' mother insisted that he finish his final year of high school.

In 1944, the Billy Eckstine

band visited East St. Louis. Dizzy Gillespie

and Charlie Parker

were members of the band, and Davis was brought in on third trumpet for a couple of weeks because the regular player, Buddy Anderson, was out sick. Even after this experience, once Eckstine's band left town, Davis' parents were still keen for him to continue formal academic studies.

of Music.

Upon arriving in New York, he spent most of his first weeks in town trying to get in contact with Charlie Parker

, despite being advised against doing so by several people he met during his quest, including saxophonist

Coleman Hawkins

.

Finally locating his idol, Davis became one of the cadre of musicians who held nightly jam session

s at two of Harlem

's nightclubs, Minton's Playhouse

and Monroe's. The group included many of the future leaders of the bebop

revolution: young players such as Fats Navarro

, Freddie Webster

, and J. J. Johnson. Established musicians including Thelonious Monk

and Kenny Clarke

were also regular participants.

Davis dropped out of Juilliard, after asking permission from his father. In his autobiography, Davis criticized the Juilliard classes for centering too much on the classical European and "white" repertoire. However, he also acknowledged that Juilliard helped give him a grounding in music theory that would prove valuable in later years.

Davis began playing professionally, performing in several 52nd Street clubs with Coleman Hawkins and Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis. In 1945, he entered a recording studio for the first time, as a member of Herbie Fields

's group. This was the first of many recordings to which Davis contributed in this period, mostly as a sideman

. He finally got the chance to record as a leader in 1946, with an occasional group called the Miles Davis Sextet plus Earl Coleman and Ann Hathaway—one of the rare occasions when Davis, by then a member of the groundbreaking Charlie Parker Quintet, can be heard accompanying singers. In these early years, recording sessions where Davis was the leader were the exception rather than the rule; his next date as leader would not come until 1947.

Around 1945, Dizzy Gillespie

parted ways with Parker, and Davis was hired as Gillespie's replacement in his quintet, which also featured Max Roach

on drums, Al Haig

(replaced later by Sir Charles Thompson and Duke Jordan

) on piano, and Curley Russell

(later replaced by Tommy Potter

and Leonard Gaskin

) on bass.

With Parker's quintet, Davis went into the studio several times, already showing hints of the style for which he would become known. On an oft-quoted take of Parker's signature song, "Now's the Time", Davis takes a melodic solo, whose unbop-like quality anticipates the "cool jazz

" period that would follow. The Parker quintet also toured widely. During a stop in Los Angeles, Parker had a nervous breakdown

that landed him in the Camarillo State Mental Hospital

for several months, and Davis found himself stranded. He roomed and collaborated for some time with bassist Charles Mingus

, before getting a job on Billy Eckstine

's California tour, which eventually brought him back to New York. In 1948, Parker returned to New York, and Davis rejoined his group.

The relationships within the quintet, however, were growing tense. Parker's erratic behavior (attributable to his well-known drug addiction) and artistic choices (both Davis and Roach objected to having Duke Jordan as a pianist and would have preferred Bud Powell

) became sources of friction. In December 1948, disputes over money (Davis claims he was not being paid) began to strain their relationship even further. Davis finally left the group following a confrontation with Parker at the Royal Roost.

For Davis, his departure from Parker's group marked the beginning of a period in which he worked mainly as a freelancer and as a sideman in some of the most important combos on the New York jazz scene.

. Evans' basement apartment had become the meeting place for several young musicians and composers (including Davis, Roach, pianist John Lewis

, and baritone sax player Gerry Mulligan

) unhappy with the increasingly virtuoso instrumental techniques that dominated the bebop scene of the time. Evans had been the arranger for the Claude Thornhill

orchestra, and it was the sound of this group, as well as Duke Ellington

's example, that suggested the creation of an unusual line-up: a nonet

including a French horn and a tuba

(this accounts for the "tuba band" moniker that was to be associated with the combo).

Davis took an active role in the project, so much so that it soon became "his project". The objective was to achieve a sound similar to the human voice, through carefully arranged compositions and by emphasizing a relaxed, melodic approach to the improvisations.

The nonet debuted in the summer of 1948, with a two-week engagement at the Royal Roost. The sign announcing the performance gave a surprising prominence to the role of the arrangers: "Miles Davis Nonet. Arrangements by Gil Evans

, John Lewis and Gerry Mulligan

". It was, in fact, so unusual that Davis had to persuade the Roost's manager, Ralph Watkins, to allow the sign to be worded in this way; he prevailed only with the help of Monte Kay

, the club's artistic director.

The nonet was active until the end of 1949, along the way undergoing several changes in personnel: Roach and Davis were constantly featured, along with Mulligan, tuba player Bill Barber

, and alto saxophonist Lee Konitz

, who had been preferred to Sonny Stitt

(whose playing was considered too bop-oriented). Over the months, John Lewis alternated with Al Haig on piano, Mike Zwerin

with Kai Winding

on trombone (Johnson was touring at the time), Junior Collins

with Sandy Siegelstein and Gunther Schuller

on French horn, and Al McKibbon

with Joe Shulman

on bass. Singer Kenny Hagood

was added for one track during the recording

The presence of white musicians in the group angered some black jazz players, many of whom were unemployed at the time, but Davis rebuffed their criticisms.

A contract with Capitol Records

granted the nonet several recording sessions between January 1949 and April 1950. The material they recorded was released in 1956 on an album whose title, Birth of the Cool

, gave its name to the "cool jazz

" movement that developed at the same time and partly shared the musical direction begun by Davis' group.

For his part, Davis was fully aware of the importance of the project, which he pursued to the point of turning down a job with Duke Ellington

's orchestra.

The importance of the nonet experience would become clear to critics and the larger public only in later years, but, at least commercially, the nonet was not a success. The liner notes

of the first recordings of the Davis Quintet for Columbia Records

call it one of the most spectacular failures of the jazz club scene. This was bitterly noted by Davis, who claimed the invention of the cool style and resented the success that was later enjoyed—in large part because of the media's attention—by white "cool jazz" musicians (Mulligan and Dave Brubeck

in particular).

This experience also marked the beginning of the lifelong friendship between Davis and Gil Evans, an alliance that would bear important results in the years to follow.

, Kenny Clarke

(who remained in Europe after the tour), and James Moody

. Davis was fascinated by Paris and its cultural environment, where black jazz musicians, and African Americans in general, often felt better respected than they did in their homeland. While in Paris, Davis began a relationship with French actress and singer Juliette Gréco

.

Many of his new and old friends (Davis, in his autobiography, mentions Clarke) tried to persuade him to stay in France, but Davis decided to return to New York. Back in the States, he began to feel deeply depressed. The depression was due in part to his separation from Gréco, in part to his feeling underappreciated by the critics (who were hailing Davis' former collaborators as leaders of the cool jazz movement), and in part to the unraveling of his liaison with a former St. Louis schoolmate who was living with him in New York and with whom he had two children.

These are the factors to which Davis traces a heroin habit that deeply affected him for the next four years. Though Davis denies it in his autobiography, it is also likely that the environment in which he was living played a role. Most of Davis' associates at the time, some of them perhaps in imitation of Charlie Parker, had drug addictions of their own (among them, sax players Sonny Rollins

and Dexter Gordon

, trumpeters Fats Navarro

and Freddie Webster

, and drummer Art Blakey

). For the next four years, Davis supported his habit partly with his music and partly by living the life of a hustler. By 1953, his drug addiction was beginning to impair his ability to perform. Heroin had killed some of his friends (Navarro and Freddie Webster). He himself had been arrested for drug possession while on tour in Los Angeles, and his drug habit had been made public in a devastating interview that Cab Calloway

gave to Down Beat.

Realizing his precarious condition, Davis tried several times to end his drug addiction, finally succeeding in 1954 after returning to his father's home in St. Louis for several months and literally locking himself in a room until he had gone through a painful withdrawal. During this period he avoided New York and played mostly in Detroit and other midwestern towns, where drugs were then harder to come by. A widely-related story, attributed to Richard (Prophet) Jennings was that Davis, while in Detroit playing at the Blue Bird club as a guest soloist in Billy Mitchell

's house band along with Tommy Flanagan

, Elvin Jones

, Betty Carter

, Yusef Lateef

, Barry Harris

, Thad Jones

, Curtis Fuller

and Donald Byrd

stumbled into Baker's Keyboard Lounge

out of the rain, soaking wet and carrying his trumpet in a paper bag under his coat, walked to the bandstand and interrupted Max Roach

and Clifford Brown

in the midst of performing Sweet Georgia Brown

by beginning to play My Funny Valentine

, and then, after finishing the song, stumbled back into the rainy night. Davis was supposedly embarrassed into getting clean by this incident. In his autobiography, Davis disputed this account, stating that Roach had requested that Davis play with him that night, and that the details of the incident, such as carrying his horn in a paper bag and interrupting Roach and Brown, were fictional and that his decision to quit heroin was unrelated to the incident.

Despite all the personal turmoil, the 1950–54 period was actually quite fruitful for Davis artistically. He made quite a number of recordings and had several collaborations with other important musicians. He got to know the music of Chicago pianist Ahmad Jamal

, whose elegant approach and use of space influenced him deeply. He also definitively severed his stylistic ties with bebop.

In 1951, Davis met Bob Weinstock

, the owner of Prestige Records

, and signed a contract with the label. Between 1951 and 1954, he released many records on Prestige, with several different combos. While the personnel of the recordings varied, the lineup often featured Sonny Rollins

and Art Blakey

. Davis was particularly fond of Rollins and tried several times, in the years that preceded his meeting with John Coltrane

, to recruit him for a regular group. He never succeeded, however, mostly because Rollins was prone to make himself unavailable for months at a time. In spite of the casual occasions that generated these recordings, their quality is almost always quite high, and they document the evolution of Davis' style and sound. During this time he began using the Harmon mute, held close to the microphone

, in a way that grew to be his signature, and his phrasing, especially in ballad

s, became spacious, melodic, and relaxed. This sound was to become so characteristic that the use of the Harmon mute by any jazz trumpet player since immediately conjures up Miles Davis.

The most important Prestige recordings of this period (Dig

, Blue Haze

, Bags' Groove

, Miles Davis and the Modern Jazz Giants, and Walkin'

) originated mostly from recording sessions in 1951 and 1954, after Davis' recovery from his addiction. Also of importance are his five Blue Note

recordings, collected in the Miles Davis Volume 1

album.

With these recordings, Davis assumed a central position in what is known as hard bop

. In contrast with bebop, hard bop used slower tempos and a less radical approach to harmony and melody, often adopting popular tunes and standards from the American songbook as starting points for improvisation. Hard bop also distanced itself from cool jazz by virtue of a harder beat and by its constant reference to the blues

, both in its traditional form and in the form made popular by rhythm and blues

. A few critics go as far as to call Walkin the album that created hard bop, but the point is debatable, given the number of musicians who were working along similar lines at the same time (and of course many of them recorded or played with Davis).

Also in this period Davis gained a reputation for being distant, cold, and withdrawn and for having a quick temper. Among the several factors that contributed to this reputation were his contempt for the critics and specialized press and some well-publicized confrontations with the public and with fellow musicians. (One occasion, in which he had a near fight with Thelonious Monk

during the recording of Bags' Groove, received wide exposure in the specialized press.)

The "nocturnal" quality of Davis' playing and his somber reputation, along with his whispering voice, earned him the lasting moniker of "prince of darkness", adding a patina of mystery to his public persona.

, where his performance (and especially his solo on "'Round Midnight

") was greatly admired and prompted the critics to hail the "return of Miles Davis". At the same time, Davis recruited the players for a formation that became known as his "first great quintet": John Coltrane

on tenor saxophone, Red Garland

on piano, Paul Chambers

on bass, and Philly Joe Jones

on drums.

None of these musicians, with the exception of Davis, had received a great deal of exposure before that time; Chambers, in particular, was very young (19 at the time), a Detroit player who had been on the New York scene for only about a year, working with the bands of Bennie Green

, Paul Quinichette

, George Wallington

, J. J. Johnson, and Kai Winding

. Coltrane was little known at the time, in spite of earlier collaborations with Dizzy Gillespie

, Earl Bostic

, and Johnny Hodges

. Davis hired Coltrane as a replacement for Sonny Rollins, after unsuccessfully trying to recruit alto saxophonist Julian "Cannonball" Adderley.

The repertoire included many bebop mainstays, standards

from the Great American Songbook

and the pre-bop era, and some traditional tunes. The prevailing style of the group was a development of the Davis experience in the previous years—Davis playing long, legato

, and essentially melodic lines, while Coltrane, who during these years emerged as a leading figure on the musical scene, contrasted by playing high-energy solos.

With the new formation also came a new recording contract. In Newport

, Davis had met Columbia Records

producer George Avakian

, who persuaded him to sign with his label. The quintet made its debut on record with the extremely well received 'Round About Midnight

. Before leaving Prestige, however, Davis had to fulfill his obligations during two days of recording sessions in 1956. Prestige released these recordings in the following years as four albums: Relaxin' with the Miles Davis Quintet

, Steamin' with the Miles Davis Quintet

, Workin' with the Miles Davis Quintet

, and Cookin' with the Miles Davis Quintet

. While the recording took place in a studio, each record of this series has the structure and feel of a live performance, with several first takes on each album. The records became almost instant classics and were instrumental in establishing Davis' quintet as one of the best on the jazz scene.

The quintet was disbanded for the first time in 1957, following a series of personal problems that Davis blames on the drug addiction of the other musicians. Davis played some gigs at the Cafe Bohemia with a short-lived formation that included Sonny Rollins and drummer Art Taylor

, and then traveled to France, where he recorded the score to Louis Malle

's film Ascenseur pour l'échafaud

. With the aid of French session musicians Barney Wilen

, Pierre Michelot

, and René Urtreger

, and American drummer Kenny Clarke

, he recorded the entire soundtrack with an innovative procedure, without relying on written material: starting from sparse indication of the harmony and a general feel of a given piece, the group played by watching the movie on a screen in front of them and improvising.

Returning to New York in 1958, Davis successfully recruited Cannonball Adderley for his standing group. Coltrane, who in the meantime had freed himself from his drug habits, was available after a highly fruitful experience with Thelonious Monk and was hired back, as was Philly Joe Jones. With the quintet re-formed as a sextet, Davis recorded Milestones, an album anticipating the new directions he was preparing to give to his music.

Almost immediately after the recording of Milestones, Davis fired Garland and, shortly afterward, Jones, again for behavioral problems; he replaced them with Bill Evans

——a young white pianist with a strong classical background——and drummer Jimmy Cobb

. With this revamped formation, Davis began a year during which the sextet performed and toured extensively and produced a record (1958 Miles, also known as 58 Sessions). Evans had a unique, impressionistic approach to the piano, and his musical ideas had a strong influence on Davis. But after only eight months on the road with the group, he was burned out and left. He was soon replaced by Wynton Kelly

, a player who brought to the sextet a swinging

, bluesy approach that contrasted with Evans' more delicate playing.

, often playing flugelhorn

as well as trumpet. The first, Miles Ahead

(1957), showcased his playing with a jazz big band

and a horn section arranged by Evans. Songs included Dave Brubeck

's "The Duke," as well as Léo Delibes

's "The Maids of Cadiz," the first piece of European classical music Davis had recorded. Another distinctive feature of the album was the orchestral passages that Evans had devised as transitions between the different tracks, which were joined together with the innovative use of editing

in the post-production phase, turning each side of the album into a seamless piece of music.

In 1958, Davis and Evans were back in the studio to record Porgy and Bess

, an arrangement of pieces from George Gershwin

's opera of the same name

. The lineup included three members of the sextet: Paul Chambers, Philly Joe Jones, and Julian "Cannonball" Adderley. Davis called the album one of his favorites.

Sketches of Spain

(1959–1960) featured songs by contemporary Spanish composer Joaquin Rodrigo

and also Manuel de Falla

, as well as Gil Evans originals with a Spanish flavor. Miles Davis at Carnegie Hall (1961) includes Rodrigo's Concierto de Aranjuez

, along with other compositions recorded in concert with an orchestra under Evans' direction.

Sessions with Davis and Evans in 1962 resulted in the album Quiet Nights

, a short collection of bossa nova

s that was released against the wishes of both artists: Evans stated it was only half an album, and blamed the record company; Davis blamed producer Teo Macero, whom he didn't speak to for more than two years. This was the last time Evans and Davis made a full album together; despite the professional separation, however, Davis noted later that "my best friend is Gil Evans."

, Kind of Blue

. He called back Bill Evans, months away from forming what would become his own seminal trio, for the album sessions, as the music had been planned around Evans' piano style. Both Davis and Evans were personally acquainted with the ideas of pianist George Russell regarding modal jazz

, Davis from discussions with Russell and others before the Birth of the Cool

sessions, and Evans from study with Russell in 1956. Davis, however, had neglected to inform current pianist Kelly of Evans' role in the recordings; Kelly subsequently played only on the track "Freddie Freeloader

" and was not present at the April dates for the album. "So What" and "All Blues

" had been played by the sextet at performances prior to the recording sessions, but for the other three compositions, Davis and Evans prepared skeletal harmonic frameworks that the other musicians saw for the first time on the day of recording, to allow a fresher approach to their improvisation

s. The resulting album has proven to be both highly popular and enormously influential. According to the RIAA, Kind of Blue is the best-selling jazz album of all time, having been certified as quadruple platinum (4 million copies sold). In December 2009, the US House of Representatives voted 409–0 to pass a resolution honoring the album as a national treasure.

The trumpet Davis used on the recording is currently displayed in the music building on the campus of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro

. It was donated to the school by Arthur "Buddy" Gist, who met Davis in 1949 and became a close friend. The gift was the reason why the jazz program at UNCG is named the "Miles Davis Jazz Studies Program."

In 1959, the Miles Davis Quintet

was appearing at the famous Birdland

nightclub in New York City. After finishing a 27 minute recording for the armed services

, Davis took a break outside the club. As he was escorting an attractive blonde woman across the sidewalk to a taxi, Davis was told by Patrolman Gerald Kilduff to "move on." Davis explained that he worked at the nightclub and refused to move. The officer said that he would arrest Davis and grabbed him as Davis protected himself. Witnesses said that Kilduff punched Davis in the stomach with his nightstick without provocation. Two nearby detectives held the crowd back as a third detective, Don Rolker, approached Davis from behind and beat him about the head. Davis was then arrested and taken to jail where he was charged with feloniously assaulting an officer. He was then taken to St. Clary Hospital where he received five stitches for a wound on his head. Davis attempted to pursue the case in the courts, before eventually dropping the proceedings in a plea bargain

in order to recover his suspended Cabaret Card, enabling him to return to work in New York clubs.

Davis persuaded Coltrane to play with the group on one final European tour in the spring of 1960. Coltrane then departed to form his classic quartet, although he returned for some of the tracks on Davis' 1961 album Someday My Prince Will Come. After Coltrane, Davis tried various saxophonists, including Jimmy Heath

, Sonny Stitt

, and Hank Mobley

. The quintet with Hank Mobley was recorded in the studio and on several live engagements at Carnegie Hall

and the Black Hawk jazz club

in San Francisco. Stitt's playing with the group is found on a recording made in Olympia

, Paris (where Davis and Coltrane had played a few months before) and the Live in Stockholm album.

In 1963, Davis' longtime rhythm section of Kelly, Chambers, and Cobb departed. He quickly got to work putting together a new group, including tenor saxophonist

George Coleman

and bassist Ron Carter

. Davis, Coleman, Carter and a few other musicians recorded half the tracks for an album in the spring of 1963. A few weeks later, seventeen-year-old drummer Tony Williams and pianist Herbie Hancock

joined the group, and soon afterward Davis, Coleman, and the new rhythm section recorded the rest of Seven Steps to Heaven

.

The rhythm players melded together quickly as a section and with the horns. The group's rapid evolution can be traced through the Seven Steps to Heaven album, In Europe (July 1963), My Funny Valentine

(February 1964), and Four and More (also February 1964). The quintet played essentially the same repertoire of bebop tunes and standards that earlier Davis bands had played, but they tackled them with increasing structural and rhythmic freedom and, in the case of the up-tempo material, breakneck speed.

Coleman left in the spring of 1964, to be replaced by avant-garde

saxophonist Sam Rivers

, on the suggestion of Tony Williams. Rivers remained in the group only briefly, but was recorded live with the quintet in Japan; this configuration can be heard on Miles in Tokyo! (July 1964).

By the end of the summer, Davis had persuaded Wayne Shorter

to leave Art Blakey

's Jazz Messengers and join the quintet. Shorter became the group's principal composer, and some of his compositions of this era (including "Footprints" and "Nefertiti") have become standards

. While on tour in Europe, the group quickly made their first official recording, Miles in Berlin (September 1964). On returning to the United States later that year, ever the musical entrepreneur, Davis (at Jackie DeShannon

's urging) was instrumental in getting The Byrds

signed to Columbia Records

.

By the time of E.S.P.

(1965), Davis' lineup consisted of Wayne Shorter

, Herbie Hancock

(piano), Ron Carter

(bass), and Tony Williams (drums). The last of his acoustic bands, this group is often referred to as the second great quintet.

A two-night Chicago performance in late 1965 is captured on The Complete Live at the Plugged Nickel 1965

, released in 1995. Unlike their studio albums, the live engagement shows the group still playing primarily standards and bebop tunes. It is reasonable to point out, though, that while some of the titles remain the same as the tunes employed by the 1950s quintet, the speed and distance of departure from the framework of the standards bears no comparison. It could even be said that the listening experience to these standards as live performances is as much of a radical take on the jazz of the time as the new compositions of the studio albums listed below.

The recording of Live at the Plugged Nickel was not issued anywhere in the 1960s, first appearing as a Japan-only partial issue in the late 1970s, then as a double-LP in the USA and Europe in 1982. It was followed by a series of studio recordings: Miles Smiles (1966), Sorcerer (1967), Nefertiti (1967), Miles in the Sky

(1968), and Filles de Kilimanjaro

(1968). The quintet's approach to improvisation came to be known as "time no changes" or "freebop," because they abandoned the more conventional chord-change

-based approach of bebop for a modal approach. Through Nefertiti, the studio recordings consisted primarily of originals composed by Shorter, with occasional compositions by the other sidemen. In 1967, the group began to play their live concerts in continuous sets, each tune flowing into the next, with only the melody indicating any sort of demarcation. Davis's bands would continue to perform in this way until his retirement in 1975.

Miles in the Sky and Filles de Kilimanjaro, on which electric bass, electric piano, and electric guitar were tentatively introduced on some tracks, pointed the way to the subsequent fusion

phase of Davis' career. Davis also began experimenting with more rock-oriented rhythms on these records. By the time the second half of Filles de Kilimanjaro had been recorded, bassist Dave Holland

and pianist Chick Corea

had replaced Carter and Hancock in the working band, though both Carter and Hancock would occasionally contribute to future recording sessions. Davis soon began to take over the compositional duties of his sidemen.

and funk

artists such as Sly and the Family Stone, James Brown, and Jimi Hendrix

, many of whom he met through Betty Mabry

(later Betty Davis), a young model and songwriter Davis married in September 1968 and divorced a year later. The musical transition required that Davis and his band adapt to electric instrument

s in both live performances and the studio. By the time In a Silent Way

had been recorded in February 1969, Davis had augmented his quintet with additional players. At various times Hancock or Joe Zawinul

was brought in to join Corea on electric keyboards

, and guitarist John McLaughlin

made the first of his many appearances with Davis. By this point, Shorter was also doubling on soprano saxophone. After recording this album, Williams left to form his group Lifetime and was replaced by Jack DeJohnette

.

Six months later an even larger group of musicians, including Jack DeJohnette

, Airto Moreira

, and Bennie Maupin

, recorded the double LP Bitches Brew

, which became a huge seller, reaching gold status by 1976. This album and In a Silent Way were among the first fusions of jazz and rock that were commercially successful, building on the groundwork laid by Charles Lloyd, Larry Coryell, and others who pioneered a genre that would become known as jazz-rock fusion. During this period, Davis toured with Shorter, Corea, Holland, and DeJohnette. The group's repertoire included material from Bitches Brew, In a Silent Way, and the 1960s quintet albums, along with an occasional standard.

In 1972, Davis was introduced to the music of Karlheinz Stockhausen

by Paul Buckmaster

, leading to a period of new creative exploration. Biographer J. K. Chambers wrote that "the effect of Davis' study of Stockhausen could not be repressed for long... Davis' own 'space music' shows Stockhausen's influence compositionally." His recordings and performances during this period were described as "space music" by fans, by music critic Leonard Feather

, and by Buckmaster, who described it as "a lot of mood changes—heavy, dark, intense—definitely space music." Both Bitches Brew

and In a Silent Way

feature "extended" (more than 20 minutes each) compositions that were never actually "played straight through" by the musicians in the studio. Instead, Davis and producer Teo Macero

selected musical motifs

of various lengths from recorded extended improvisations and edited them together into a musical whole that exists only in the recorded version. Bitches Brew

made use of such electronic effects as multi-tracking

, tape loop

s, and other editing techniques. Both records, especially Bitches Brew, proved to be big sellers. Starting with Bitches Brew, Davis' albums began to often feature cover art

much more in line with psychedelic

art or black power

movements than that of his earlier albums. He took significant cuts in his usual performing fees in order to open for rock groups like the Steve Miller Band

, the Grateful Dead

, Neil Young

, and Santana

. Several live albums were recorded during the early 1970s at these performances: Live at the Fillmore East, March 7, 1970: It's About That Time

(March 1970), Black Beauty

(April 1970), and Miles Davis at Fillmore: Live at the Fillmore East

(June 1970).

By the time of Live-Evil in December 1970, Davis' ensemble had transformed into a much more funk-oriented group. Davis began experimenting with wah-wah effects on his horn. The ensemble with Gary Bartz

, Keith Jarrett

, and Michael Henderson

, often referred to as the "Cellar Door band" (the live portions of Live-Evil were recorded at a Washington, DC, club by that name

), never recorded in the studio, but is documented in the six-CD box set The Cellar Door Sessions, which was recorded over four nights in December 1970. In 1970, Davis contributed extensively to the soundtrack of a documentary

about the African-American boxer heavyweight champion Jack Johnson

. Himself a devotee of boxing, Davis drew parallels between Johnson, whose career had been defined by the fruitless search for a Great White Hope to dethrone him, and Davis' own career, in which he felt the musical establishment of the time had prevented him from receiving the acclaim and rewards that were due him. The resulting album, 1971's A Tribute to Jack Johnson

, contained two long pieces that featured musicians (some of whom were not credited on the record) including guitarists John McLaughlin

and Sonny Sharrock

, Herbie Hancock

on a Farfisa

organ, and drummer Billy Cobham

. McLaughlin and Cobham went on to become founding members of the Mahavishnu Orchestra in 1971.

As Davis stated in his autobiography, he wanted to make music for the young African-American audience. On the Corner

(1972) blended funk elements with the traditional jazz styles he had played his entire career. The album was highlighted by the appearance of saxophonist Carlos Garnett

. Critics were not kind to the album; in his autobiography, Davis stated that critics could not figure out how to categorize it, and he complained that the album was not promoted by the "traditional" jazz radio stations. After recording On the Corner, Davis put together a new group, with only Michael Henderson

, Carlos Garnett

, and percussionist Mtume

returning from the previous band. It included guitarist Reggie Lucas

, tabla player Badal Roy

, sitarist Khalil Balakrishna, and drummer Al Foster

. It was unusual in that none of the sidemen were major jazz instrumentalists; as a result, the music emphasized rhythmic density and shifting textures instead of individual solos. This group, which recorded in the Philharmonic Hall

for the album In Concert

(1972), was unsatisfactory to Davis. Through the first half of 1973, he dropped the tabla

and sitar

, took over keyboard duties, and added guitarist Pete Cosey

. The Davis/Cosey/Lucas/Henderson/Mtume/Foster ensemble would remain virtually intact over the next two years. Initially, Dave Liebman

played saxophones and flute with the band; in 1974, he was replaced by Sonny Fortune

.

Big Fun (1974) was a double album containing four long improvisations, recorded between 1969 and 1972. Similarly, Get Up With It

(1974) collected recordings from the previous five years. Get Up With It included "He Loved Him Madly", a tribute to Duke Ellington, as well as one of Davis' most lauded pieces from this era, "Calypso Frelimo". It was his last studio album of the 1970s. In 1974 and 1975, Columbia recorded three double-LP live Davis albums: Dark Magus

, Agharta

, and Pangaea

. Dark Magus captures a 1974 New York concert; the latter two are recordings of consecutive concerts from the same February 1975 day in Osaka

. At the time, only Agharta was available in the US; Pangaea and Dark Magus were initially released only by CBS/Sony Japan. All three feature at least two electric guitarists (Reggie Lucas and Pete Cosey, deploying an array of Hendrix-inspired electronic distortion devices; Dominique Gaumont is a third guitarist on Dark Magus), electric bass, drums, reeds, and Davis on electric trumpet and organ. These albums were the last he was to record for five years. Davis was troubled by osteoarthritis (which led to a hip replacement operation in 1976, the first of several), sickle-cell anemia, depression, bursitis

, ulcers

, and a renewed dependence on alcohol and drugs (primarily cocaine), and his performances were routinely panned by critics throughout late 1974 and early 1975. By the time the group reached Japan in February 1975, Davis was nearing a physical breakdown and required copious amounts of alcohol and narcotics to make it through his engagements. Nonetheless, as noted by Richard Cook and Brian Morton, during these concerts his trumpet playing "is of the highest and most adventurous order."

After a Newport Jazz Festival

performance at Avery Fisher Hall

in New York on July 1, 1975, Davis withdrew almost completely from the public eye for six years. As Gil Evans said, "His organism is tired. And after all the music he's contributed for 35 years, he needs a rest." In his memoirs, Davis is characteristically candid about his wayward mental state during this period, describing himself as a hermit, his house as a wreck, and detailing his drug and sex addictions. In 1976, Rolling Stone

reported rumors of his imminent demise. Although he stopped practicing trumpet on a regular basis, Davis continued to compose intermittently and made three attempts at recording during his exile from performing; these sessions (one with the assistance of Paul Buckmaster and Gil Evans, who left after not receiving promised compensation) bore little fruit and remain unreleased. In 1979, he placed in the yearly top-ten trumpeter poll of Down Beat

. Columbia continued to issue compilation album

s and records of unreleased vault material to fulfill contractual obligations. During his period of inactivity, Davis saw the fusion music that he had spearheaded over the past decade enter into the mainstream. When he emerged from retirement, Davis' musical descendants would be in the realm of New Wave

rock, and in particular the styling of Prince

.

By 1979, Davis had rekindled his relationship with actress Cicely Tyson

By 1979, Davis had rekindled his relationship with actress Cicely Tyson

. With Tyson, Davis would overcome his cocaine addiction and regain his enthusiasm for music. As he had not played trumpet for the better part of three years, regaining his famed embouchure

proved to be particularly arduous. While recording The Man with the Horn

(sessions were spread sporadically over 1979–1981), Davis played mostly wahwah with a younger, larger band.

The initial large band was eventually abandoned in favor of a smaller combo featuring saxophonist Bill Evans

and bass player Marcus Miller

, both of whom would be among Davis' most regular collaborators throughout the decade. He married Tyson in 1981; they would divorce in 1988. The Man with the Horn was finally released in 1981 and received a poor critical reception despite selling fairly well. In May, the new band played two dates as part of the Newport Jazz Festival

. The concerts, as well as the live recording We Want Miles

from the ensuing tour, received positive reviews.

By late 1982, Davis' band included French percussionist Mino Cinelu

By late 1982, Davis' band included French percussionist Mino Cinelu

and guitarist John Scofield

, with whom he worked closely on the album Star People

. In mid-1983, while working on the tracks for Decoy

, an album mixing soul music

and electronica

that was released in 1984, Davis brought in producer, composer and keyboardist Robert Irving III

, who had earlier collaborated with him on The Man with the Horn. With a seven-piece band, including Scofield, Evans, keyboardist and music director Irving, drummer Al Foster

and bassist Darryl Jones

(later of The Rolling Stones

), Davis played a series of European gigs to positive receptions. While in Europe, he took part in the recording of Aura

, an orchestral tribute to Davis composed by Danish trumpeter Palle Mikkelborg

.

You're Under Arrest, Davis' next album, was released in 1985 and included another brief stylistic detour. Included on the album were his interpretations of Cyndi Lauper

's ballad "Time After Time

", and "Human Nature

" from Michael Jackson

. Davis considered releasing an entire album of pop songs and recorded dozens of them, but the idea was scrapped. Davis noted that many of today's accepted jazz standards were in fact pop songs from Broadway theater, and that he was simply updating the "standards" repertoire with new material. 1985 also saw Davis guest-star on the TV show Miami Vice

as pimp

and minor criminal Ivory Jones in the episode titled "Junk Love" (first aired November 8, 1985).

You're Under Arrest also proved to be Davis' final album for Columbia. Trumpeter Wynton Marsalis

publicly dismissed Davis' more recent fusion recordings as not being "'true' jazz", comments Davis initially shrugged off, calling Marsalis "a nice young man, only confused". This changed after Marsalis appeared, unannounced, onstage in the midst of Davis' performance at the inaugural Vancouver International Jazz Festival

in 1986. Marsalis whispered into Davis' ear that "someone" had told him to do so; Davis responded by ordering him off the stage.

Davis grew irritated at Columbia's delay releasing Aura. The breaking point in the label-artist relationship appears to have come when a Columbia jazz producer requested Davis place a goodwill birthday call to Marsalis. Davis signed with Warner Brothers

shortly thereafter.

Davis collaborated with a number of figures from the British new wave

movement during this period, including Scritti Politti

. At the invitation of producer Bill Laswell

, Davis recorded some trumpet parts during sessions for Public Image Ltd.

's Album, according to Public Image's John Lydon

in the liner notes of their Plastic Box box set. In Lydon's words, however, "strangely enough, we didn't use (his contributions)." (Also according to Lydon in the Plastic Box notes, Davis favorably compared Lydon's singing voice to his trumpet sound.)

Having first taken part in the Artists United Against Apartheid

recording, Davis signed with Warner Brothers records and reunited with Marcus Miller

. The resulting record, Tutu

(1986), would be his first to use modern studio tools—programmed synthesizers, samples

and drum loops—to create an entirely new setting for his playing. Ecstatically reviewed on its release, the album would frequently be described as the modern counterpart of Sketches of Spain and won a Grammy in 1987.

He followed Tutu with Amandla

, another collaboration with Miller and George Duke

, plus the soundtracks to four movies: Street Smart

, Siesta

, The Hot Spot

(with bluesman John Lee Hooker

), and Dingo. He continued to tour with a band of constantly rotating personnel and a critical stock at a level higher than it had been for 15 years. His last recordings, both released posthumously, were the hip hop

-influenced studio album Doo-Bop

and Miles & Quincy Live at Montreux

, a collaboration with Quincy Jones

for the 1991 Montreux Jazz Festival

in which Davis performed the repertoire from his 1940s and 1950s recordings for the first time in decades.

In 1988 he had a small part as a street musician in the film Scrooged

, starring Bill Murray

. In 1989, Davis was interviewed on 60 Minutes

by Harry Reasoner. He received the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award

in 1990.

In early 1991, he appeared in the Rolf de Heer

film Dingo

as a jazz musician. In the film's opening sequence, Davis and his band unexpectedly land on a remote airstrip in the Australian outback and proceed to perform for the stunned locals. The performance was one of Davis' last on film.

Miles Davis died on September 28, 1991 from the combined effects of a stroke, pneumonia

and respiratory failure

in Santa Monica, California

at the age of 65. He is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx.

is the best-selling album in the history of jazz music and was praised by the United States House of Representatives

to "pass a symbolic resolution honoring the masterpiece and reaffirming jazz as a national treasure."

Many well-known musicians rose to prominence as members of Davis' ensembles, including saxophonists Gerry Mulligan

, John Coltrane

, Cannonball Adderley, George Coleman

, Wayne Shorter

, Dave Liebman

, Branford Marsalis

and Kenny Garrett

; trombonist J. J. Johnson; pianists Horace Silver

, Red Garland

, Wynton Kelly

, Bill Evans

, Herbie Hancock

, Joe Zawinul

, Chick Corea

, Keith Jarrett

and Kei Akagi

; guitarists John McLaughlin

, Pete Cosey

, John Scofield

and Mike Stern

; bassists Paul Chambers

, Ron Carter

, Dave Holland

, Marcus Miller

and Darryl Jones

; and drummers Elvin Jones

, Philly Joe Jones

, Jimmy Cobb

, Tony Williams, Billy Cobham

, Jack DeJohnette

, and Al Foster

.

As an innovative bandleader and composer, Miles Davis has influenced many notable musicians and bands from diverse genres. These include Wayne Shorter

, Cannonball Adderley, Herbie Hancock

, Cassandra Wilson

, Lalo Schifrin

, Tangerine Dream

, Brand X

, Mtume

, Benny Bailey

, Joe Bonner

, Don Cherry

, Urszula Dudziak

, Sugizo

, Bill Evans

, Bill Hardman

, The Lounge Lizards

, Hugh Masekela

, John McLaughlin

, King Crimson

, Steely Dan

, Frank Zappa

, Duane Allman

, Radiohead

, The Flaming Lips

, Lydia Lunch

, Talk Talk

, Michael Franks, Sting, Lonnie Liston Smith

, Jiří Stivín

, Tim Hagans

, Julie Christensen

, Jerry Garcia

, David Grisman

, Vassar Clements

, Snooky Young

, Prince

, and Christian Scott

.

Miles' influence on the people who played with him has been described by music writer and author Christopher Smith as follows:

His approach, owing largely to the African American performance tradition that focused on individual expression, emphatic interaction, and creative response to shifting contents, had a profound impact on generations of jazz musicians.

In 1986, the New England Conservatory awarded Miles Davis an Honorary Doctorate

for his extraordinary contributions to music. Since 1960 the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences

(NARAS) has honored him with eight Grammy Awards, a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, and three Grammy Hall of Fame Awards.

In 2010, Moldejazz

premiered a play called Driving Miles which focused on a landmark concert Davis performed in Molde

, Norway, in 1984.

Jazz

Jazz is a musical style that originated at the beginning of the 20th century in African American communities in the Southern United States. It was born out of a mix of African and European music traditions. From its early development until the present, jazz has incorporated music from 19th and 20th...

musician, trumpeter, bandleader

Bandleader

A bandleader is the leader of a band of musicians. The term is most commonly, though not exclusively, used with a group that plays popular music as a small combo or a big band, such as one which plays jazz, blues, rhythm and blues or rock and roll music....

, and composer. Widely considered one of the most influential musicians of the 20th century, Miles Davis was, with his musical groups, at the forefront of several major developments in jazz music, including bebop

Bebop

Bebop differed drastically from the straightforward compositions of the swing era, and was instead characterized by fast tempos, asymmetrical phrasing, intricate melodies, and rhythm sections that expanded on their role as tempo-keepers...

, cool jazz

Cool jazz

Cool is a style of modern jazz music that arose following the Second World War. It is characterized by its relaxed tempos and lighter tone, in contrast to the bebop style that preceded it...

, hard bop

Hard bop

Hard bop is a style of jazz that is an extension of bebop music. Journalists and record companies began using the term in the mid-1950s to describe a new current within jazz which incorporated influences from rhythm and blues, gospel music, and blues, especially in the saxophone and piano...

, modal jazz

Modal jazz

Modal jazz is jazz that uses musical modes rather than chord progressions as a harmonic framework. Originating in the late 1950s and 1960s, modal jazz is characterized by Miles Davis's "Milestones" Kind of Blue and John Coltrane's classic quartet from 1960–64. Other important performers include...

, and jazz fusion

Jazz fusion

Jazz fusion is a musical fusion genre that developed from mixing funk and R&B rhythms and the amplification and electronic effects of rock, complex time signatures derived from non-Western music and extended, typically instrumental compositions with a jazz approach to lengthy group improvisations,...

.

On October 7, 2008, his 1959 album Kind of Blue

Kind of Blue

Kind of Blue is a studio album by American jazz musician Miles Davis, released August 17, 1959, on Columbia Records in the United States. Recording sessions for the album took place at Columbia's 30th Street Studio in New York City on March 2 and April 22, 1959...

received its fourth platinum

RIAA certification

In the United States, the Recording Industry Association of America awards certification based on the number of albums and singles sold through retail and other ancillary markets. Other countries have similar awards...

certification from the Recording Industry Association of America

Recording Industry Association of America

The Recording Industry Association of America is a trade organization that represents the recording industry distributors in the United States...

(RIAA), for shipments of at least four million copies in the United States. Miles Davis was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum is a museum located on the shore of Lake Erie in downtown Cleveland, Ohio, United States. It is dedicated to archiving the history of some of the best-known and most influential artists, producers, engineers and others who have, in some major way,...

in 2006. Davis was noted as "one of the key figures in the history of jazz".

On November 5, 2009, Rep. John Conyers

John Conyers

John Conyers, Jr. is the U.S. Representative for , serving since 1965 . He is a member of the Democratic Party...

of Michigan sponsored a measure in the US House of Representatives to recognize and commemorate the album Kind of Blue

Kind of Blue

Kind of Blue is a studio album by American jazz musician Miles Davis, released August 17, 1959, on Columbia Records in the United States. Recording sessions for the album took place at Columbia's 30th Street Studio in New York City on March 2 and April 22, 1959...

on its 50th anniversary. The measure also affirms jazz

Jazz

Jazz is a musical style that originated at the beginning of the 20th century in African American communities in the Southern United States. It was born out of a mix of African and European music traditions. From its early development until the present, jazz has incorporated music from 19th and 20th...

as a national treasure and "encourages the United States government to preserve and advance the art form of jazz music." It passed, unanimously, with a vote of 409–0 on December 15, 2009.

Early life (1926–44)

Miles Dewey Davis was born on May 26, 1926, to an affluent African American family in AltonAlton, Illinois

Alton is a city on the Mississippi River in Madison County, Illinois, United States, about north of St. Louis, Missouri. The population was 27,865 at the 2010 census. It is a part of the Metro-East region of the Greater St. Louis metropolitan area in Southern Illinois...

, Illinois. His father, Dr. Miles Henry Davis

Miles Henry Davis

Miles Henry Davis was a prominent American dentist and father of jazz legend Miles Davis.-Biography:Davis was born on March 1, 1898 in Noble Lake, Arkansas. He was a son of Miles D. and Mary Davis...

, was a dentist. In 1927 the family moved to East St. Louis, Illinois

East St. Louis, Illinois

East St. Louis is a city located in St. Clair County, Illinois, USA, directly across the Mississippi River from St. Louis, Missouri in the Metro-East region of Southern Illinois. As of the 2010 census, the city had a total population of 27,006, less than one-third of its peak of 82,366 in 1950...

. They also owned a substantial ranch in northern Arkansas

Arkansas

Arkansas is a state located in the southern region of the United States. Its name is an Algonquian name of the Quapaw Indians. Arkansas shares borders with six states , and its eastern border is largely defined by the Mississippi River...

, where Davis learned to ride horses as a boy.

Davis' mother, Cleota Mae (Henry) Davis, wanted her son to learn the piano; she was a capable blues pianist but kept this fact hidden from her son. His musical studies began at 13, when his father gave him a trumpet and arranged lessons with local musician Elwood Buchanan

Elwood Buchanan

Elwood C. Buchanan, Sr was an American jazz trumpeter and teacher who became an early mentor of Miles Davis.Buchanan was born in St Louis, Missouri on January 26, 1907, and was trained in music by Joseph Gustat, the principal trumpeter with the St Louis Symphony Orchestra...

. Davis later suggested that his father's instrument choice was made largely to irk his wife, who disliked the trumpet's sound. Against the fashion of the time, Buchanan stressed the importance of playing without vibrato

Vibrato

Vibrato is a musical effect consisting of a regular, pulsating change of pitch. It is used to add expression to vocal and instrumental music. Vibrato is typically characterised in terms of two factors: the amount of pitch variation and the speed with which the pitch is varied .-Vibrato and...

; he was reported to have slapped Davis' knuckles every time he started using heavy vibrato

Vibrato

Vibrato is a musical effect consisting of a regular, pulsating change of pitch. It is used to add expression to vocal and instrumental music. Vibrato is typically characterised in terms of two factors: the amount of pitch variation and the speed with which the pitch is varied .-Vibrato and...

. Davis would carry his clear signature tone throughout his career. He once remarked on its importance to him, saying, "I prefer a round sound with no attitude in it, like a round voice with not too much tremolo

Tremolo

Tremolo, or tremolando, is a musical term that describes various trembling effects, falling roughly into two types. The first is a rapid reiteration...

and not too much bass. Just right in the middle. If I can’t get that sound I can’t play anything." Clark Terry

Clark Terry

Clark Terry is an American swing and bop trumpeter, a pioneer of the fluegelhorn in jazz, educator, NEA Jazz Masters inductee, and recipient of the 2010 Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award...

was another important early influence.

By age 16, Davis was a member of the music society and playing professionally when not at school. At 17, he spent a year playing in Eddie Randle's band, the Blue Devils. During this time, Sonny Stitt

Sonny Stitt

Edward "Sonny" Stitt was an American jazz saxophonist of the bebop/hard bop idiom. He was also one of the best-documented saxophonists of his generation, recording over 100 albums in his lifetime...

tried to persuade him to join the Tiny Bradshaw band, then passing through town, but Davis' mother insisted that he finish his final year of high school.

In 1944, the Billy Eckstine

Billy Eckstine

William Clarence Eckstine was an American singer of ballads and a bandleader of the swing era. Eckstine's smooth baritone and distinctive vibrato broke down barriers throughout the 1940s, first as leader of the original bop big-band, then as the first romantic black male in popular...

band visited East St. Louis. Dizzy Gillespie

Dizzy Gillespie

John Birks "Dizzy" Gillespie was an American jazz trumpet player, bandleader, singer, and composer dubbed "the sound of surprise".Together with Charlie Parker, he was a major figure in the development of bebop and modern jazz...

and Charlie Parker

Charlie Parker

Charles Parker, Jr. , famously called Bird or Yardbird, was an American jazz saxophonist and composer....

were members of the band, and Davis was brought in on third trumpet for a couple of weeks because the regular player, Buddy Anderson, was out sick. Even after this experience, once Eckstine's band left town, Davis' parents were still keen for him to continue formal academic studies.

New York and the bebop years begin (1944–48)

In the fall of 1944, following graduation from high school, Davis moved to New York City to study at the Juilliard SchoolJuilliard School

The Juilliard School, located at the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts in New York City, United States, is a performing arts conservatory which was established in 1905...

of Music.

Upon arriving in New York, he spent most of his first weeks in town trying to get in contact with Charlie Parker

Charlie Parker

Charles Parker, Jr. , famously called Bird or Yardbird, was an American jazz saxophonist and composer....

, despite being advised against doing so by several people he met during his quest, including saxophonist

Saxophone

The saxophone is a conical-bore transposing musical instrument that is a member of the woodwind family. Saxophones are usually made of brass and played with a single-reed mouthpiece similar to that of the clarinet. The saxophone was invented by the Belgian instrument maker Adolphe Sax in 1846...

Coleman Hawkins

Coleman Hawkins

Coleman Randolph Hawkins was an American jazz tenor saxophonist. Hawkins was one of the first prominent jazz musicians on his instrument. As Joachim E. Berendt explained, "there were some tenor players before him, but the instrument was not an acknowledged jazz horn"...

.

Finally locating his idol, Davis became one of the cadre of musicians who held nightly jam session

Jam session

Jam sessions are often used by musicians to develop new material, find suitable arrangements, or simply as a social gathering and communal practice session. Jam sessions may be based upon existing songs or forms, may be loosely based on an agreed chord progression or chart suggested by one...

s at two of Harlem

Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in the New York City borough of Manhattan, which since the 1920s has been a major African-American residential, cultural and business center. Originally a Dutch village, formally organized in 1658, it is named after the city of Haarlem in the Netherlands...

's nightclubs, Minton's Playhouse

Minton's Playhouse

Minton’s Playhouse is a jazz club and bar located on the first floor of the Cecil Hotel at 210 West 118th Street in Harlem. Minton’s was founded by tenor saxophonist Henry Minton in 1938...

and Monroe's. The group included many of the future leaders of the bebop

Bebop

Bebop differed drastically from the straightforward compositions of the swing era, and was instead characterized by fast tempos, asymmetrical phrasing, intricate melodies, and rhythm sections that expanded on their role as tempo-keepers...

revolution: young players such as Fats Navarro

Fats Navarro

Theodore "Fats" Navarro was an American jazz trumpet player. He was a pioneer of the bebop style of jazz improvisation in the 1940s. He had a strong stylistic influence on many other players, most notably Clifford Brown.-Life:Navarro was born in Key West, Florida, to Cuban-Black-Chinese parentage...

, Freddie Webster

Freddie Webster

Freddie Webster was a jazz trumpeter who, Dizzy Gillespie once said, "had the best sound on trumpet since the trumpet was invented--just alive and full of life." He is perhaps best known for being cited by Miles Davis as an early influence.Webster was born in Cleveland, Ohio...

, and J. J. Johnson. Established musicians including Thelonious Monk

Thelonious Monk

Thelonious Sphere Monk was an American jazz pianist and composer considered "one of the giants of American music". Monk had a unique improvisational style and made numerous contributions to the standard jazz repertoire, including "Epistrophy", "'Round Midnight", "Blue Monk", "Straight, No Chaser"...

and Kenny Clarke

Kenny Clarke

Kenny Clarke , born Kenneth Spearman Clarke, nicknamed "Klook" and later known as Liaqat Ali Salaam, was a jazz drummer and an early innovator of the bebop style of drumming...

were also regular participants.

Davis dropped out of Juilliard, after asking permission from his father. In his autobiography, Davis criticized the Juilliard classes for centering too much on the classical European and "white" repertoire. However, he also acknowledged that Juilliard helped give him a grounding in music theory that would prove valuable in later years.

Davis began playing professionally, performing in several 52nd Street clubs with Coleman Hawkins and Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis. In 1945, he entered a recording studio for the first time, as a member of Herbie Fields

Herbie Fields

Herbie Fields was a jazz musician. He attended New York's famed Juilliard School of Music and served in the U.S. Army from 1941–1943.-Career:...

's group. This was the first of many recordings to which Davis contributed in this period, mostly as a sideman

Sideman

A sideman is a professional musician who is hired to perform or record with a group of which he or she is not a regular member. They often tour with solo acts as well as bands and jazz ensembles. Sidemen are generally required to be adaptable to many different styles of music, and so able to fit...

. He finally got the chance to record as a leader in 1946, with an occasional group called the Miles Davis Sextet plus Earl Coleman and Ann Hathaway—one of the rare occasions when Davis, by then a member of the groundbreaking Charlie Parker Quintet, can be heard accompanying singers. In these early years, recording sessions where Davis was the leader were the exception rather than the rule; his next date as leader would not come until 1947.

Around 1945, Dizzy Gillespie

Dizzy Gillespie

John Birks "Dizzy" Gillespie was an American jazz trumpet player, bandleader, singer, and composer dubbed "the sound of surprise".Together with Charlie Parker, he was a major figure in the development of bebop and modern jazz...

parted ways with Parker, and Davis was hired as Gillespie's replacement in his quintet, which also featured Max Roach

Max Roach

Maxwell Lemuel "Max" Roach was an American jazz percussionist, drummer, and composer.A pioneer of bebop, Roach went on to work in many other styles of music, and is generally considered alongside the most important drummers in history...

on drums, Al Haig

Al Haig

Alan Warren Haig was an American jazz pianist, best known as one of the pioneers of bebop.Haig was born in Newark, New Jersey...

(replaced later by Sir Charles Thompson and Duke Jordan

Duke Jordan

Irving Sidney "Duke" Jordan was an American jazz pianist.-Biography:An imaginative and gifted pianist, Jordan was a regular member of Charlie Parker's so-called "classic quintet" , featuring Miles Davis...

) on piano, and Curley Russell

Curley Russell

Dillon "Curley" Russell was an American jazz double-bassist, who played bass on many bebop recordings.A member of the Tadd Dameron Sextet, in his heyday he was in demand for his ability to play at the rapid tempos typical of bebop, and appears on several key recordings of the period...

(later replaced by Tommy Potter

Tommy Potter

Charles Thomas Potter, born in Philadelphia on September 21, 1918, died March 1, 1988, was a jazz double bass player.Potter is known for having been a member of Charlie Parker's "classic quintet", with Miles Davis, between 1947 and 1950; he had first played with Parker in 1944, in Billy Eckstine's...

and Leonard Gaskin

Leonard Gaskin

Leonard Gaskin was an American jazz bassist born in New York City.Gaskin played on the early bebop scene at Minton's and Monroe's in New York in the early 1940s...

) on bass.

With Parker's quintet, Davis went into the studio several times, already showing hints of the style for which he would become known. On an oft-quoted take of Parker's signature song, "Now's the Time", Davis takes a melodic solo, whose unbop-like quality anticipates the "cool jazz

Cool jazz

Cool is a style of modern jazz music that arose following the Second World War. It is characterized by its relaxed tempos and lighter tone, in contrast to the bebop style that preceded it...

" period that would follow. The Parker quintet also toured widely. During a stop in Los Angeles, Parker had a nervous breakdown

Nervous breakdown

Mental breakdown is a non-medical term used to describe an acute, time-limited phase of a specific disorder that presents primarily with features of depression or anxiety.-Definition:...

that landed him in the Camarillo State Mental Hospital

Camarillo State Mental Hospital

Camarillo State Mental Hospital, also known as Camarillo State Hospital, was a psychiatric hospital for both developmentally disabled and mentally ill patients in Camarillo, California. The hospital closed in 1997. The site has been redeveloped as the California State University, Channel Islands...

for several months, and Davis found himself stranded. He roomed and collaborated for some time with bassist Charles Mingus

Charles Mingus

Charles Mingus Jr. was an American jazz musician, composer, bandleader, and civil rights activist.Mingus's compositions retained the hot and soulful feel of hard bop and drew heavily from black gospel music while sometimes drawing on elements of Third stream, free jazz, and classical music...

, before getting a job on Billy Eckstine

Billy Eckstine

William Clarence Eckstine was an American singer of ballads and a bandleader of the swing era. Eckstine's smooth baritone and distinctive vibrato broke down barriers throughout the 1940s, first as leader of the original bop big-band, then as the first romantic black male in popular...

's California tour, which eventually brought him back to New York. In 1948, Parker returned to New York, and Davis rejoined his group.

The relationships within the quintet, however, were growing tense. Parker's erratic behavior (attributable to his well-known drug addiction) and artistic choices (both Davis and Roach objected to having Duke Jordan as a pianist and would have preferred Bud Powell

Bud Powell

Earl Rudolph "Bud" Powell was an American Jazz pianist. Powell has been described as one of "the two most significant pianists of the style of modern jazz that came to be known as bop", the other being his friend and contemporary Thelonious Monk...

) became sources of friction. In December 1948, disputes over money (Davis claims he was not being paid) began to strain their relationship even further. Davis finally left the group following a confrontation with Parker at the Royal Roost.

For Davis, his departure from Parker's group marked the beginning of a period in which he worked mainly as a freelancer and as a sideman in some of the most important combos on the New York jazz scene.

Birth of the Cool (1948–49)

In 1948 Davis grew close to the Canadian composer and arranger Gil EvansGil Evans

Gil Evans was a jazz pianist, arranger, composer and bandleader, active in the United States...

. Evans' basement apartment had become the meeting place for several young musicians and composers (including Davis, Roach, pianist John Lewis

John Lewis (pianist)

John Aaron Lewis was an American jazz pianist and composer best known as the musical director of the Modern Jazz Quartet.- Early life:...

, and baritone sax player Gerry Mulligan

Gerry Mulligan

Gerald Joseph "Gerry" Mulligan was an American jazz saxophonist, clarinetist, composer and arranger. Though Mulligan is primarily known as one of the leading baritone saxophonists in jazz history – playing the instrument with a light and airy tone in the era of cool jazz – he was also...

) unhappy with the increasingly virtuoso instrumental techniques that dominated the bebop scene of the time. Evans had been the arranger for the Claude Thornhill

Claude Thornhill

Claude Thornhill was an American pianist, arranger, composer, and bandleader...

orchestra, and it was the sound of this group, as well as Duke Ellington

Duke Ellington

Edward Kennedy "Duke" Ellington was an American composer, pianist, and big band leader. Ellington wrote over 1,000 compositions...

's example, that suggested the creation of an unusual line-up: a nonet

Nonet (music)

In music, a nonet is a composition which requires nine musicians for a performance, or a musical group that consists of nine people. The standard nonet scoring is for wind quintet, violin, viola, cello, and contrabass, though other combinations are also found...

including a French horn and a tuba

Tuba

The tuba is the largest and lowest-pitched brass instrument. Sound is produced by vibrating or "buzzing" the lips into a large cupped mouthpiece. It is one of the most recent additions to the modern symphony orchestra, first appearing in the mid-19th century, when it largely replaced the...

(this accounts for the "tuba band" moniker that was to be associated with the combo).

Davis took an active role in the project, so much so that it soon became "his project". The objective was to achieve a sound similar to the human voice, through carefully arranged compositions and by emphasizing a relaxed, melodic approach to the improvisations.

The nonet debuted in the summer of 1948, with a two-week engagement at the Royal Roost. The sign announcing the performance gave a surprising prominence to the role of the arrangers: "Miles Davis Nonet. Arrangements by Gil Evans

Gil Evans

Gil Evans was a jazz pianist, arranger, composer and bandleader, active in the United States...

, John Lewis and Gerry Mulligan

Gerry Mulligan

Gerald Joseph "Gerry" Mulligan was an American jazz saxophonist, clarinetist, composer and arranger. Though Mulligan is primarily known as one of the leading baritone saxophonists in jazz history – playing the instrument with a light and airy tone in the era of cool jazz – he was also...

". It was, in fact, so unusual that Davis had to persuade the Roost's manager, Ralph Watkins, to allow the sign to be worded in this way; he prevailed only with the help of Monte Kay

Monte Kay

Monte Kay, September 18, 1924 – May 25, 1988 was a prominent figure of the New York jazz scene in the late 1940s and 1950s, producing - often in association with the disc jockey Symphony Sid - several young musicians and acting as musical director of several night clubs...

, the club's artistic director.

The nonet was active until the end of 1949, along the way undergoing several changes in personnel: Roach and Davis were constantly featured, along with Mulligan, tuba player Bill Barber

Bill Barber (musician)

John William Barber, known as Bill Barber or Billy Barber is considered by many to be the first person to play tuba in modern jazz. He is best known for his work with Miles Davis on albums such as Birth of the Cool, Sketches of Spain and Miles Ahead...

, and alto saxophonist Lee Konitz

Lee Konitz

Lee Konitz is an American jazz composer and alto saxophonist born in Chicago, Illinois.Generally considered one of the driving forces of Cool Jazz, Konitz has also performed successfully in bebop and avant-garde settings...

, who had been preferred to Sonny Stitt

Sonny Stitt

Edward "Sonny" Stitt was an American jazz saxophonist of the bebop/hard bop idiom. He was also one of the best-documented saxophonists of his generation, recording over 100 albums in his lifetime...

(whose playing was considered too bop-oriented). Over the months, John Lewis alternated with Al Haig on piano, Mike Zwerin

Mike Zwerin

Mike Zwerin was an American cool jazz musician and author. Zwerin as a musician played the trombone and bass trumpet within various jazz ensembles. He was active within the jazz and prog. jazz musical community as a session musician...

with Kai Winding

Kai Winding

Kai Chresten Winding was a popular Danish-born American trombonist and jazz composer. He is well known for a successful collaboration with fellow trombonist J. J. Johnson.-Biography:...

on trombone (Johnson was touring at the time), Junior Collins

Junior Collins

Addison Collins, Jr. was an American French horn player.A member of Glenn Miller's Army Air Force band, and Claude Thornhill's orchestra, he went on to play with Charlie Parker, Gerry Mulligan and others....

with Sandy Siegelstein and Gunther Schuller

Gunther Schuller

Gunther Schuller is an American composer, conductor, horn player, author, historian, and jazz musician.- Biography and works :...

on French horn, and Al McKibbon

Al McKibbon

Al McKibbon was an American jazz double bassist, known for his work in bop, hard bop, and Latin jazz.In 1947, after working with Lucky Millinder, Tab Smith, J. C. Heard, and Coleman Hawkins, he replaced Ray Brown in Dizzy Gillespie's band, in which he played until 1950...

with Joe Shulman

Joe Shulman

Joseph "Joe" Shulman was an American jazz bassist.Shulman's first professional experience was with Scat Davis in 1940, which he followed with a stint alongside Les Brown in 1942. He joined the military in 1943, and recorded with Django Reinhardt while a member of Glenn Miller's wartime band...

on bass. Singer Kenny Hagood

Kenny Hagood

Kenny "Pancho" Hagood was an American jazz vocalist.-Biography:Hagood was born in Detroit, Michigan and first sang at age 17 with Benny Carter. He sang with the Dizzy Gillespie Orchestra from 1946 to 1948 and then with Tadd Dameron later in 1948...

was added for one track during the recording

The presence of white musicians in the group angered some black jazz players, many of whom were unemployed at the time, but Davis rebuffed their criticisms.

A contract with Capitol Records

Capitol Records

Capitol Records is a major United States based record label, formerly located in Los Angeles, but operating in New York City as part of Capitol Music Group. Its former headquarters building, the Capitol Tower, is a major landmark near the corner of Hollywood and Vine...

granted the nonet several recording sessions between January 1949 and April 1950. The material they recorded was released in 1956 on an album whose title, Birth of the Cool

Birth of the Cool