Modern Scots

Encyclopedia

Modern Scots describes the varieties

of (Lowland) Scots

traditionally spoken in Lowland

Scotland

and parts of Ulster

from 1700.

Throughout its history, Modern Scots has been undergoing a process of language attrition

, whereby successive generations of speakers have adopted more and more features from Standard English. This process of language contact

has accelerated rapidly since widespread access to mass media

in English and increased population mobility became available after the Second World War. It has recently taken on the nature of wholesale language shift

towards Scottish English

, sometimes also termed language change

, convergence

or merger. By the end of the twentieth century Scots was at an advanced stage of language death

over much of Lowland Scotland. Residual features of Scots are often regarded as slang

.

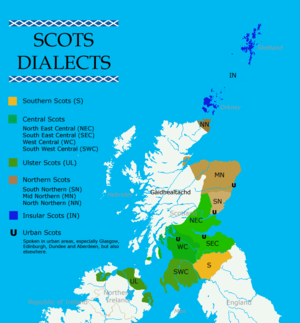

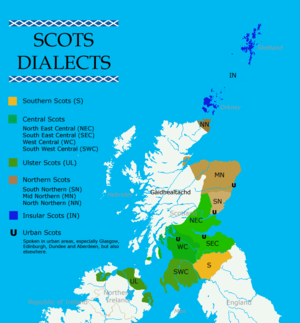

The varieties of Modern Scots are generally divided into five dialect groups:

The varieties of Modern Scots are generally divided into five dialect groups:

The southern extent of Scots may be identified by the range of a number of pronunciation features which set Scots apart from neighbouring English dialects. The Scots pronunciation of come [kʌm] contrasts with [kʊm] in Northern English

. The Scots realisation [kʌm] reaches as far south as the mouth of the north Esk

in north Cumbria

, crossing Cumbria and skirting the foot of the Cheviots before reaching the east coast at Bamburgh

some 12 miles north of Alnwick

. The Scots x–English [∅]/f cognate group (micht-might, eneuch-enough, etc.) can be found in a small portion of north Cumbria with the southern limit stretching from Bewcastle

to Longtown

and Gretna. The Scots pronunciation of wh as ʍ becomes English w south of Carlisle but remains in Northumberland

, but Northumberland realises “r” as ʁ, often called the burr

, which is not a Scots realisation. Thus the greater part of the valley of the Esk and the whole of Liddesdale

can be considered to be northern English dialects rather than Scots ones. From the nineteenth century onwards influence from the South

through education and increased mobility have caused Scots features to retreat northwards so that for all practical purposes the political and linguistic boundaries may be considered to coincide.

As well as the main dialects, Edinburgh

, Dundee

and Glasgow

(see Glasgow patter

) have local variations on an Anglicised form of Central Scots. In Aberdeen

, Mid Northern Scots is spoken by a minority. Due to them being roughly near the border between the two dialects, places like Dundee

and Perth

can contain elements and influences of both Northern and Central Scots.

was generally adopted as the literary language from the late seventeenth century, the eighteenth century Scots revival saw the introduction of a new literary language

descended from the old court Scots, but with an orthography that had abandonded some of the more distinctive old Scots spellings, adopted many standard English spellings, although from the rhymes it was clear that a Scots pronunciation was intended, and introduced what came to be known as the apologetic apostrophe

, generally occurring where a consonant

exists in the Standard English cognate

. This Written Scots drew not only on the vernacular but also on the King James Bible and was also heavily influenced by the norms an conventions of Augustan English poetry

. Consequently this written Scots looked very similar to contemporary Standard English, suggesting a somewhat modified version of that, rather than a distinct speech form with a phonological system which had been developing independently for many centuries. This modern literary dialect, ‘Scots of the book’ or Standard Scots once again gave Scots an orthography of its own, lacking neither “authority nor author.” This literary language used throughout Lowland Scotland and Ulster, embodied by writers such as Allan Ramsay

, Robert Fergusson

, Robert Burns

, Sir Walter Scott, Charles Murray

, David Herbison, James Orr

, James Hogg

and William Laidlaw

among others, is well described in the 1921 Manual of Modern Scots.

Other authors developed dialect writing, preferring to represent their own speech in a more phonological manner rather than following the pan-dialect conventions of modern literary Scots, especially for the northern and insular dialects of Scots.

During the first half of the twentieth century, knowledge of eighteenth and nineteenth century literary norms waned and currently there is no institutionalised standard literary form. The later literary variety referred to as ‘synthetic Scots’ or Lallans

also shows the marked influence of Standard English its grammar and spelling, more so that other Scots dialects.

In the second half of the twentieth century a number of proposals for spelling reform were presented. Commenting on this, John Corbett (2003: 260) writes that "devising a normative orthography for Scots has been one of the greatest linguistic hobbies of the past century." Most proposals entailed regularising the use of established eighteenth and nineteenth century conventions, in particular the avoidance of the apologetic apostrophe

which supposedly represented "missing" English letters. Such letters were never actually missing in Scots. For example, in the fourteenth century, Barbour spelt the Scots cognate

of 'taken' as tane. Since there has been no k in the word for over 700 years, representing its omission with an apostrophe seems pointless. The current spelling is usually taen.

Through the twentieth century, with the decline of spoken Scots and knowledge of the literary tradition, phonetic (often humorous) representations became more common.

The vowel system of Scots:

In Scots, vowel length

is usually conditioned by the Scottish Vowel Length Rule

. Words which differ only slightly in pronunciation from Scottish English

are generally spelled as in English. Other words may be spelt the same but differ in pronunciation, for example: aunt, swap, want and wash with /a/, bull, full v. and pull with /ʌ/, bind, find and wind v., etc. with /ɪ/.

Nouns of measure and quantity unchanged in the plural: fower fit (four feet), twa mile (two miles), five pund (five pounds), three hunderwecht (three hundredweight).

Regular plurals include laifs (loaves), leafs (leaves), shelfs (shelves) and wifes (wives).

A third adjective/adverb yon/yonder, thon/thonder indicating something at some distance D'ye see yon/thon hoose ower yonder/thonder? Also thae (those) and thir (these), the plurals of that and this respectively.

In Northern Scots this and that are also used where "these" and "those" would be in Standard English.

), are no longer used much in Scots but occurred historically and are still found in anglicised literary Scots. Can, shoud/shud (should), and will/wull are the preferred Scots forms.

Scots employs double modal constructions He'll no can come the day (He won't be able to come today), A micht coud come the morn (I may be able to come tomorrow), A uised tae coud dae it, but no nou (I used to be able to do it, but not now).

Negation occurs by using the adverb no, in the North East nae, as in A'm no comin (I'm not coming), A'll no learn ye (I will not teach you), or by using the suffix -na sometimes spelled nae , as in A dinna ken (I don't know), Thay canna come (They can't come), We coudna hae telt him (We couldn't have told him), and A hivna seen her (I haven't seen her).

The usage with no is preferred to that with -na with contractable auxiliary verbs like -ll for will, or in yes/no questions with any auxiliary He'll no come and Did he no come?

whereby verbs end in -s in all persons and numbers except when a single personal pronoun is next to the verb, Thay say he's ower wee, Thaim that says he's ower wee, Thir lassies says he's ower wee (They say he's too small), etc. Thay're comin an aw but Five o thaim's comin, The lassies? Thay'v went but Ma brakes haes went. Thaim that comes first is serred first (Those who come first are served first). The trees growes green in the simmer (The trees grow green in summer).

Wis 'was' may replace war 'were', but not conversely: You war/wis thare.

or regular

verbs is -it, -t or -ed, according to the preceding consonant or vowel: The -ed ending can be written -'d if the e is silent or has no purpose.

Many verbs have (strong

or irregular

) forms which are distinctive from Standard English (two forms connected with ~ means that they are variants):

in are now usually /ən/ but may still be differentiated /ən/ and /in/ in Southern Scots and, /ən/ and /ɪn/ North Northern Scots.

Adverbs are also formed with -s, -lies, lins, gate(s)and wey(s) -wey, whiles/whyls (at times), mebbes (perhaps), brawlies (splendidly), geylies (pretty well), aiblins (perhaps), airselins (backwards), hauflins (partly), hidlins (secretly), maistlins (almost), awgates (always, everywhere), ilkagate (everywhere), onygate/oniegate (anyhow), ilkawey (everywhere), onywey/oniewey (anyhow, anywhere), endweys (straight ahead), whit wey (how, why).

In the North East, the 'wh' in the above words is pronounced /f/.

Certain verbs are often used progressively He wis thinkin he wad tell her, He wis wantin tae tell her.

Verbs of motion may be dropped before an adverb or adverbial phrase of motion A'm awa tae ma bed, That's me awa hame, A'll intae the hoose an see him.

s in -ie, burnie small burn (stream), feardie/feartie (frightened person, coward), gamie (gamekeeper), kiltie (kilted soldier), postie (postman), wifie (woman, also used in Geordie

dialect), rhodie (rhododendron), and also in -ock, bittock (little bit), playock (toy, plaything), sourock (sorrel) and Northern –ag, bairnag (little), bairn (child, common in Geordie dialect), Cheordag (Geordie), -ockie, hooseockie (small house), wifeockie (little woman), both influenced by the Scottish Gaelic diminutive -ag (-óg in Irish Gaelic).

Ae /eː/, /jeː/ is used as an adjective before a noun such as : The Ae Hoose (The One House), Ae laddie an twa lassies (One boy and two girls). Ane is pronounced variously, depending on dialect, /en/, /jɪn/ in many Central

and Southern varieties, /in/ in some Northern

and Insular

varieties, and /wan/, often written yin, een and wan in dialect writing.

The impersonal form of 'one' is a body as in A body can niver bide wi a body's sel (One can never live by oneself).

and Robert Fergusson

, and later continued by writers such as Robert Burns

and Sir Walter Scott

. Scott introduced vernacular dialogue to his novels. Other well-known authors like Robert Louis Stevenson

, William Alexander, George MacDonald

, J. M. Barrie

and other members of the Kailyard school

like Ian Maclaren

also wrote in Scots or used it in dialogue, as did George Douglas Brown

whose writing is regarded as a useful corrective to the more roseate presentations of the kailyard school.

In the Victorian era

popular Scottish newspapers regularly included articles and commentary in the vernacular, often of unprecedented proportions.

In the early twentieth century, a renaissance

in the use of Scots occurred, its most vocal figure being Hugh MacDiarmid

whose benchmark poem A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle

(1926) did much to demonstrate the power of Scots as a modern idiom. Other contemporaries were Douglas Young

, John Buchan

, Sidney Goodsir Smith, Robert Garioch

and Robert McLellan

. The revival extended to verse and other literature.

In 1983 William Laughton Lorimer

's translation of the New Testament from the original Greek was published.

From The Maker to Posterity (Robert Louis Stevenson 1850–1894)

From The House with the Green Shutters (George Douglas Brown 1869–1902)

From Embro to the Ploy (Robert Garioch 1909 - 1981)

From The New Testament in Scots (William Laughton Lorimer 1885- 1967)

Mathew:1:18ff

Variety (linguistics)

In sociolinguistics a variety, also called a lect, is a specific form of a language or language cluster. This may include languages, dialects, accents, registers, styles or other sociolinguistic variation, as well as the standard variety itself...

of (Lowland) Scots

Scots language

Scots is the Germanic language variety spoken in Lowland Scotland and parts of Ulster . It is sometimes called Lowland Scots to distinguish it from Scottish Gaelic, the Celtic language variety spoken in most of the western Highlands and in the Hebrides.Since there are no universally accepted...

traditionally spoken in Lowland

Scottish Lowlands

The Scottish Lowlands is a name given to the Southern half of Scotland.The area is called a' Ghalldachd in Scottish Gaelic, and the Lawlands ....

Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

and parts of Ulster

Ulster

Ulster is one of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the north of the island. In ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial...

from 1700.

Throughout its history, Modern Scots has been undergoing a process of language attrition

Language attrition

Language attrition is the loss of a first or second language or a portion of that language by individuals. Speakers who routinely use more than one language may not use either of their languages in ways which are exactly like that of a monolingual speaker...

, whereby successive generations of speakers have adopted more and more features from Standard English. This process of language contact

Language contact

Language contact occurs when two or more languages or varieties interact. The study of language contact is called contact linguistics.Multilingualism has likely been common throughout much of human history, and today most people in the world are multilingual...

has accelerated rapidly since widespread access to mass media

Mass media

Mass media refers collectively to all media technologies which are intended to reach a large audience via mass communication. Broadcast media transmit their information electronically and comprise of television, film and radio, movies, CDs, DVDs and some other gadgets like cameras or video consoles...

in English and increased population mobility became available after the Second World War. It has recently taken on the nature of wholesale language shift

Language shift

Language shift, sometimes referred to as language transfer or language replacement or assimilation, is the progressive process whereby a speech community of a language shifts to speaking another language. The rate of assimilation is the percentage of individuals with a given mother tongue who speak...

towards Scottish English

Scottish English

Scottish English refers to the varieties of English spoken in Scotland. It may or may not be considered distinct from the Scots language. It is always considered distinct from Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic language....

, sometimes also termed language change

Language change

Language change is the phenomenon whereby phonetic, morphological, semantic, syntactic, and other features of language vary over time. The effect on language over time is known as diachronic change. Two linguistic disciplines in particular concern themselves with studying language change:...

, convergence

Language convergence

Language convergence is a type of contact-induced change whereby languages with many bilingual speakers mutually borrow morphological and syntactic features, making their typology more similar....

or merger. By the end of the twentieth century Scots was at an advanced stage of language death

Language death

In linguistics, language death is a process that affects speech communities where the level of linguistic competence that speakers possess of a given language variety is decreased, eventually resulting in no native and/or fluent speakers of the variety...

over much of Lowland Scotland. Residual features of Scots are often regarded as slang

Slang

Slang is the use of informal words and expressions that are not considered standard in the speaker's language or dialect but are considered more acceptable when used socially. Slang is often to be found in areas of the lexicon that refer to things considered taboo...

.

Dialects

- Insular ScotsInsular ScotsInsular Scots comprises varieties of Lowland Scots generally subdivided into:*Shetlandic*OrcadianBoth dialects share much Norn vocabulary, Shetlandic more so, than does any other Scots dialect, perhaps because they both were under strong Scandinavian influence in their recent past.It should not be...

– spoken in Orkney and Shetland. - Northern ScotsNorthern ScotsNorthern Scots refers to the dialects of Modern Scots traditionally spoken in eastern parts of the north of Scotland.The dialect is generally divided into:*North Northern spoken in Caithness, Easter Ross and the Black Isle....

– Spoken north of the Firth of TayFirth of TayThe Firth of Tay is a firth in Scotland between the council areas of Fife, Perth and Kinross, the City of Dundee and Angus, into which Scotland's largest river in terms of flow, the River Tay, empties....

.- North NorthernNorth Northern ScotsNorth Northern Scots refers to the dialects of Scots spoken in Caithness, the Black Isle and Easter Ross.-Caithness:The dialect of Caithness is generally spoken in the lowlying land to the east of a line drawn from Clyth Ness to some 4 miles west of Thurso. To the west of that Scottish Gaelic used...

– spoken in CaithnessCaithnessCaithness is a registration county, lieutenancy area and historic local government area of Scotland. The name was used also for the earldom of Caithness and the Caithness constituency of the Parliament of the United Kingdom . Boundaries are not identical in all contexts, but the Caithness area is...

, Easter RossEaster RossEaster Ross is a loosely defined area in the east of Ross, Highland, Scotland.The name is used in the constituency name Caithness, Sutherland and Easter Ross, which is the name of both a British House of Commons constituency and a Scottish Parliament constituency...

and the Black IsleBlack IsleThe Black Isle is an eastern area of the Highland local government council area of Scotland, within the county of Ross and Cromarty. The name nearly always includes the article "the"....

. - Mid Northern (also called North East and popularly known as the Doric) – spoken in MorayMorayMoray is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland. It lies in the north-east of the country, with coastline on the Moray Firth, and borders the council areas of Aberdeenshire and Highland.- History :...

, BuchanBuchanBuchan is one of the six committee areas and administrative areas of Aberdeenshire Council, Scotland. These areas were created by the council in 1996, when the Aberdeenshire unitary council area was created under the Local Government etc Act 1994...

and AberdeenshireAberdeenshireAberdeenshire is one of the 32 unitary council areas in Scotland and a lieutenancy area.The present day Aberdeenshire council area does not include the City of Aberdeen, now a separate council area, from which its name derives. Together, the modern council area and the city formed historic...

. - South Northern – spoken in east AngusAngusAngus is one of the 32 local government council areas of Scotland, a registration county and a lieutenancy area. The council area borders Aberdeenshire, Perth and Kinross and Dundee City...

and the MearnsKincardineshireThe County of Kincardine, also known as Kincardineshire or The Mearns was a local government county on the coast of northeast Scotland...

.

- North Northern

- Central ScotsCentral ScotsCentral Scots is a group of dialects of Scots language. It was spoken by Robert Burns.Central Scots is spoken from Fife and Perthshire to the Lothians and Wigtownshire, often split into North East Central Scots and South East Central Scots , West Central Scots and South West Central Scots ....

– spoken in the Central LowlandsCentral LowlandsThe Central Lowlands or Midland Valley is a geologically defined area of relatively low-lying land in southern Scotland. It consists of a rift valley between the Highland Boundary Fault to the north and the Southern Uplands Fault to the south...

and South west Scotland.- North East Central – spoken north of the ForthRiver ForthThe River Forth , long, is the major river draining the eastern part of the central belt of Scotland.The Forth rises in Loch Ard in the Trossachs, a mountainous area some west of Stirling...

, in south east PerthshirePerthshirePerthshire, officially the County of Perth , is a registration county in central Scotland. It extends from Strathmore in the east, to the Pass of Drumochter in the north, Rannoch Moor and Ben Lui in the west, and Aberfoyle in the south...

and west Angus. - South East Central – spoken in the Lothians, PeeblesshirePeeblesshirePeeblesshire , the County of Peebles or Tweeddale was a county of Scotland. Its main town was Peebles, and it bordered Midlothian to the north, Selkirkshire to the east, Dumfriesshire to the south, and Lanarkshire to the west.After the local government reorganisation of 1975 the use of the name...

and BerwickshireBerwickshireBerwickshire or the County of Berwick is a registration county, a committee area of the Scottish Borders Council, and a lieutenancy area of Scotland, on the border with England. The town after which it is named—Berwick-upon-Tweed—was lost by Scotland to England in 1482... - West Central – spoken in DunbartonshireDunbartonshireDunbartonshire or the County of Dumbarton is a lieutenancy area and registration county in the west central Lowlands of Scotland lying to the north of the River Clyde. Until 1975 it was a county used as a primary unit of local government with its county town and administrative centre at the town...

, LanarkshireLanarkshireLanarkshire or the County of Lanark ) is a Lieutenancy area, registration county and former local government county in the central Lowlands of Scotland...

, RenfrewshireRenfrewshireRenfrewshire is one of 32 council areas used for local government in Scotland. Located in the west central Lowlands, it is one of three council areas contained within the boundaries of the historic county of Renfrewshire, the others being Inverclyde to the west and East Renfrewshire to the east...

, AyrshireAyrshireAyrshire is a registration county, and former administrative county in south-west Scotland, United Kingdom, located on the shores of the Firth of Clyde. Its principal towns include Ayr, Kilmarnock and Irvine. The town of Troon on the coast has hosted the British Open Golf Championship twice in the...

, on the Isle of ButeIsle of ButeBute is an island in the Firth of Clyde in Scotland. Formerly part of the county of Buteshire, it now constitutes part of the council area of Argyll and Bute. Its resident population was 7,228 in April 2001.-Geography:...

and to the southern extremity of KintyreKintyreKintyre is a peninsula in western Scotland, in the southwest of Argyll and Bute. The region stretches approximately 30 miles , from the Mull of Kintyre in the south, to East Loch Tarbert in the north...

. - South West Central – spoken in west DumfriesshireDumfriesshireDumfriesshire or the County of Dumfries is a registration county of Scotland. The lieutenancy area of Dumfries has similar boundaries.Until 1975 it was a county. Its county town was Dumfries...

, KirkcudbrightshireKirkcudbrightshireThe Stewartry of Kirkcudbright or Kirkcudbrightshire was a county of south-western Scotland. It was also known as East Galloway, forming the larger Galloway region with Wigtownshire....

and WigtownshireWigtownshireWigtownshire or the County of Wigtown is a registration county in the Southern Uplands of south west Scotland. Until 1975, the county was one of the administrative counties used for local government purposes, and is now administered as part of the council area of Dumfries and Galloway...

.

- North East Central – spoken north of the Forth

- Southern ScotsSouth ScotsSouthern Scots is one of the names given to the dialect of Scots spoken in the Scottish Borders counties of mid and east Dumfriesshire, Roxburghshire and Selkirkshire, with the notable exception of Berwickshire and Peeblesshire, which are, like Edinburgh, part of the SE Central Scots dialect area...

– spoken in mid and east DumfriesshireDumfriesshireDumfriesshire or the County of Dumfries is a registration county of Scotland. The lieutenancy area of Dumfries has similar boundaries.Until 1975 it was a county. Its county town was Dumfries...

and the Scottish BordersScottish BordersThe Scottish Borders is one of 32 local government council areas of Scotland. It is bordered by Dumfries and Galloway in the west, South Lanarkshire and West Lothian in the north west, City of Edinburgh, East Lothian, Midlothian to the north; and the non-metropolitan counties of Northumberland...

counties SelkirkshireSelkirkshireSelkirkshire or the County of Selkirk is a registration county of Scotland. It borders Peeblesshire to the west, Midlothian to the north, Berwickshire to the north-east, Roxburghshire to the east, and Dumfriesshire to the south...

and RoxburghshireRoxburghshireRoxburghshire or the County of Roxburgh is a registration county of Scotland. It borders Dumfries to the west, Selkirk to the north-west, and Berwick to the north. To the south-east it borders Cumbria and Northumberland in England.It was named after the Royal Burgh of Roxburgh...

, in particular the valleys of the AnnanRiver AnnanThe River Annan is a river in southwest Scotland. It rises at the foot of Hart Fell, five miles north of Moffat. A second fork rises on Annanhead Hill and flows through the Devil's Beef Tub before joining at the Hart Fell fork north of Moffat.From there it flows past the town of Lockerbie, and...

, the EskRiver Esk, Dumfries and GallowayThe River Esk is a river in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland, that flows into the Solway Firth. It also flows for a small way through the English county of Cumbria before entering the Solway....

, the Liddel WaterLiddel WaterLiddel Water is a river running through southern Scotland and northern England, for much of its course forming the border between the two countries, and was formerly one of the boundaries of the Debatable Lands....

, the TeviotRiver TeviotThe River Teviot, or Teviot Water, is a river of the Scottish Borders area of Scotland, and a tributary of the River Tweed.It rises in the western foothills of Comb Hill on the border of Dumfries and Galloway...

and the Yarrow Water. It is also known as the "border tongue" or "border Scots". - Ulster Scots – spoken primarily by the descendants of Scottish settlers in UlsterUlsterUlster is one of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the north of the island. In ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial...

, particularly counties AntrimCounty AntrimCounty Antrim is one of six counties that form Northern Ireland, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland. Adjoined to the north-east shore of Lough Neagh, the county covers an area of 2,844 km², with a population of approximately 616,000...

, DownCounty Down-Cities:*Belfast *Newry -Large towns:*Dundonald*Newtownards*Bangor-Medium towns:...

and DonegalCounty DonegalCounty Donegal is a county in Ireland. It is part of the Border Region and is also located in the province of Ulster. It is named after the town of Donegal. Donegal County Council is the local authority for the county...

. Also known as "Ullans".

The southern extent of Scots may be identified by the range of a number of pronunciation features which set Scots apart from neighbouring English dialects. The Scots pronunciation of come [kʌm] contrasts with [kʊm] in Northern English

Northern English

Northern English is a group of dialects of the English language. It includes the North East England dialects, which are similar in some respects to Scots....

. The Scots realisation [kʌm] reaches as far south as the mouth of the north Esk

River Esk, Cumbria

The River Esk is a river in the Lake District in Cumbria, England. It is one of two River Esks in Cumbria, and not to be confused with the River Esk which flows on the Scottish side of the border....

in north Cumbria

Cumbria

Cumbria , is a non-metropolitan county in North West England. The county and Cumbria County Council, its local authority, came into existence in 1974 after the passage of the Local Government Act 1972. Cumbria's largest settlement and county town is Carlisle. It consists of six districts, and in...

, crossing Cumbria and skirting the foot of the Cheviots before reaching the east coast at Bamburgh

Bamburgh

Bamburgh is a large village and civil parish on the coast of Northumberland, England. It has a population of 454.It is notable for two reasons: the imposing Bamburgh Castle, overlooking the beach, seat of the former Kings of Northumbria, and at present owned by the Armstrong family ; and its...

some 12 miles north of Alnwick

Alnwick

Alnwick is a small market town in north Northumberland, England. The town's population was just over 8000 at the time of the 2001 census and Alnwick's district population was 31,029....

. The Scots x–English [∅]/f cognate group (micht-might, eneuch-enough, etc.) can be found in a small portion of north Cumbria with the southern limit stretching from Bewcastle

Bewcastle

Bewcastle is a large civil parish in the City of Carlisle district of Cumbria, England.According to the 2001 census the parish had a population of 411. The parish is large and includes the settlements of Roadhead, Shopford, Blackpool Gate, Roughsike and The Flatt. To the north the parish extends...

to Longtown

Longtown, Cumbria

Longtown is a small town in northern Cumbria, England, with a population of around 3,000. It is in the parish of Arthuret and on the River Esk, not far from the Anglo-Scottish border. Nearby was the Battle of Arfderydd....

and Gretna. The Scots pronunciation of wh as ʍ becomes English w south of Carlisle but remains in Northumberland

Northumberland

Northumberland is the northernmost ceremonial county and a unitary district in North East England. For Eurostat purposes Northumberland is a NUTS 3 region and is one of three boroughs or unitary districts that comprise the "Northumberland and Tyne and Wear" NUTS 2 region...

, but Northumberland realises “r” as ʁ, often called the burr

Guttural R

In linguistics, guttural R refers to pronunciation of a rhotic consonant as a guttural consonant. These consonants are usually uvular, but can also be realized as a velar, pharyngeal, or glottal rhotic...

, which is not a Scots realisation. Thus the greater part of the valley of the Esk and the whole of Liddesdale

Liddesdale

Liddesdale, the valley of the Liddel Water, in the County of Roxburgh, southern Scotland, extends in a south-westerly direction from the vicinity of Peel Fell to the River Esk, a distance of...

can be considered to be northern English dialects rather than Scots ones. From the nineteenth century onwards influence from the South

Southern England

Southern England, the South and the South of England are imprecise terms used to refer to the southern counties of England bordering the English Midlands. It has a number of different interpretations of its geographic extents. The South is considered by many to be a cultural region with a distinct...

through education and increased mobility have caused Scots features to retreat northwards so that for all practical purposes the political and linguistic boundaries may be considered to coincide.

As well as the main dialects, Edinburgh

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland, the second largest city in Scotland, and the eighth most populous in the United Kingdom. The City of Edinburgh Council governs one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas. The council area includes urban Edinburgh and a rural area...

, Dundee

Dundee

Dundee is the fourth-largest city in Scotland and the 39th most populous settlement in the United Kingdom. It lies within the eastern central Lowlands on the north bank of the Firth of Tay, which feeds into the North Sea...

and Glasgow

Glasgow

Glasgow is the largest city in Scotland and third most populous in the United Kingdom. The city is situated on the River Clyde in the country's west central lowlands...

(see Glasgow patter

Glasgow patter

Glaswegian or The Glasgow Patter is a dialect spoken in and around Glasgow, Scotland. In addition to local West Mid Scots, the dialect has Highland English and Hiberno-English influences, owing to the speech of Highlanders and Irish people, who migrated in large numbers to the Glasgow area in the...

) have local variations on an Anglicised form of Central Scots. In Aberdeen

Aberdeen

Aberdeen is Scotland's third most populous city, one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas and the United Kingdom's 25th most populous city, with an official population estimate of ....

, Mid Northern Scots is spoken by a minority. Due to them being roughly near the border between the two dialects, places like Dundee

Dundee

Dundee is the fourth-largest city in Scotland and the 39th most populous settlement in the United Kingdom. It lies within the eastern central Lowlands on the north bank of the Firth of Tay, which feeds into the North Sea...

and Perth

Perth, Scotland

Perth is a town and former city and royal burgh in central Scotland. Located on the banks of the River Tay, it is the administrative centre of Perth and Kinross council area and the historic county town of Perthshire...

can contain elements and influences of both Northern and Central Scots.

Orthography

Although southern Modern EnglishModern English

Modern English is the form of the English language spoken since the Great Vowel Shift in England, completed in roughly 1550.Despite some differences in vocabulary, texts from the early 17th century, such as the works of William Shakespeare and the King James Bible, are considered to be in Modern...

was generally adopted as the literary language from the late seventeenth century, the eighteenth century Scots revival saw the introduction of a new literary language

Literary language

A literary language is a register of a language that is used in literary writing. This may also include liturgical writing. The difference between literary and non-literary forms is more marked in some languages than in others...

descended from the old court Scots, but with an orthography that had abandonded some of the more distinctive old Scots spellings, adopted many standard English spellings, although from the rhymes it was clear that a Scots pronunciation was intended, and introduced what came to be known as the apologetic apostrophe

Apologetic apostrophe

The apologetic or parochial apostrophe is the distinctive use of apostrophes in Modern Scots orthography. Apologetic apostrophes generally occurred where a consonant exists in the Standard English cognate, as in a , gi'e and wi .The practice, unknown in Older Scots, was introduced in the 18th...

, generally occurring where a consonant

Consonant

In articulatory phonetics, a consonant is a speech sound that is articulated with complete or partial closure of the vocal tract. Examples are , pronounced with the lips; , pronounced with the front of the tongue; , pronounced with the back of the tongue; , pronounced in the throat; and ,...

exists in the Standard English cognate

Cognate

In linguistics, cognates are words that have a common etymological origin. This learned term derives from the Latin cognatus . Cognates within the same language are called doublets. Strictly speaking, loanwords from another language are usually not meant by the term, e.g...

. This Written Scots drew not only on the vernacular but also on the King James Bible and was also heavily influenced by the norms an conventions of Augustan English poetry

Augustan literature

Augustan literature is a style of English literature produced during the reigns of Queen Anne, King George I, and George II on the 1740s with the deaths of Pope and Swift...

. Consequently this written Scots looked very similar to contemporary Standard English, suggesting a somewhat modified version of that, rather than a distinct speech form with a phonological system which had been developing independently for many centuries. This modern literary dialect, ‘Scots of the book’ or Standard Scots once again gave Scots an orthography of its own, lacking neither “authority nor author.” This literary language used throughout Lowland Scotland and Ulster, embodied by writers such as Allan Ramsay

Allan Ramsay (poet)

Allan Ramsay was a Scottish poet , playwright, publisher, librarian and wig-maker.-Life and career:...

, Robert Fergusson

Robert Fergusson

Robert Fergusson was a Scottish poet. After formal education at the University of St Andrews, Fergusson followed an essentially bohemian life course in Edinburgh, the city of his birth, then at the height of intellectual and cultural ferment as part of the Scottish enlightenment...

, Robert Burns

Robert Burns

Robert Burns was a Scottish poet and a lyricist. He is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland, and is celebrated worldwide...

, Sir Walter Scott, Charles Murray

Charles Murray (poet)

Charles Murray was a poet who wrote in the Doric dialect of Scots. He was born and raised in Alford in north east Scotland. However he wrote much of his poetry while living in South Africa where he spent most of his working life as a successful civil engineer...

, David Herbison, James Orr

James Orr (poet)

James Orr was a poet or rhyming weaver from Ulster also known as the Bard of Ballycarry, who wrote in English and Ulster Scots. He was the foremost of the Ulster Weaver Poets, and was writing contemporaneously with Robert Burns...

, James Hogg

James Hogg

James Hogg was a Scottish poet and novelist who wrote in both Scots and English.-Early life:James Hogg was born in a small farm near Ettrick, Scotland in 1770 and was baptized there on 9 December, his actual date of birth having never been recorded...

and William Laidlaw

William Laidlaw

William Laidlaw , poet, son of a border farmer, becamesteward and amanuensis to Sir Walter Scott, and was the author of thebeautiful and well-known ballad, Lucy's Flittin....

among others, is well described in the 1921 Manual of Modern Scots.

Other authors developed dialect writing, preferring to represent their own speech in a more phonological manner rather than following the pan-dialect conventions of modern literary Scots, especially for the northern and insular dialects of Scots.

During the first half of the twentieth century, knowledge of eighteenth and nineteenth century literary norms waned and currently there is no institutionalised standard literary form. The later literary variety referred to as ‘synthetic Scots’ or Lallans

Lallans

Lallans , a variant of the Modern Scots word lawlands meaning the lowlands of Scotland, was also traditionally used to refer to the Scots language as a whole...

also shows the marked influence of Standard English its grammar and spelling, more so that other Scots dialects.

In the second half of the twentieth century a number of proposals for spelling reform were presented. Commenting on this, John Corbett (2003: 260) writes that "devising a normative orthography for Scots has been one of the greatest linguistic hobbies of the past century." Most proposals entailed regularising the use of established eighteenth and nineteenth century conventions, in particular the avoidance of the apologetic apostrophe

Apologetic apostrophe

The apologetic or parochial apostrophe is the distinctive use of apostrophes in Modern Scots orthography. Apologetic apostrophes generally occurred where a consonant exists in the Standard English cognate, as in a , gi'e and wi .The practice, unknown in Older Scots, was introduced in the 18th...

which supposedly represented "missing" English letters. Such letters were never actually missing in Scots. For example, in the fourteenth century, Barbour spelt the Scots cognate

Cognate

In linguistics, cognates are words that have a common etymological origin. This learned term derives from the Latin cognatus . Cognates within the same language are called doublets. Strictly speaking, loanwords from another language are usually not meant by the term, e.g...

of 'taken' as tane. Since there has been no k in the word for over 700 years, representing its omission with an apostrophe seems pointless. The current spelling is usually taen.

Through the twentieth century, with the decline of spoken Scots and knowledge of the literary tradition, phonetic (often humorous) representations became more common.

Consonants

Most consonants are usually pronounced much as in English but:- c: /k/ or /s/, much as in English.

- ch: /x/, also gh. Medial 'cht' may be /ð/ in Northern dialects. loch (fjord or lake), nicht (night), dochter (daughter), dreich (dreary), etc. Similar to the German "Nacht".

- ch: word initial or where it follows 'r' /tʃ/. airch (arch), mairch (march), etc.

- gn: /n/. In Northern dialects /ɡn/ may occur.

- kn: /n/. In Northern dialects /kn/ or /tn/ may occur. knap (talk), knee, knowe (knoll), etc.

- ng: is always /ŋ/.

- nch: usually /nʃ/. brainch (branch), dunch (push), etc.

- r: /r/ or /ɹ/ is pronounced in all positions, i.e. rhoticallyRhotic consonantIn phonetics, rhotic consonants, also called tremulants or "R-like" sounds, are liquid consonants that are traditionally represented orthographically by symbols derived from the Greek letter rho, including "R, r" from the Roman alphabet and "Р, p" from the Cyrillic alphabet...

. - s or se: /s/ or /z/.

- t: may be a glottal stop between vowels or word final. In Ulster dentalised pronunciations may also occur, also for 'd'.

- th: /ð/ or /θ/ much as is English. In Mid Northern varieties an intervocallic /ð/ may be realised /d/. Initial 'th' in thing, think and thank, etc. may be /h/.

- wh: usually /ʍ/, older /xʍ/. Northern dialects also have /f/.

- wr: /wr/ more often /r/ but may be /vr/ in Northern dialects. wrack (wreck), wrang (wrong), write, wrocht (worked), etc.

- z: /jɪ/ or /ŋ/, may occur in some words as a substitute for the older <> (yoghYoghThe letter yogh , was used in Middle English and Older Scots, representing y and various velar phonemes. It was derived from the Old English form of the letter g.In Middle English writing, tailed z came to be indistinguishable from yogh....

). For example: brulzie (broil), gaberlunzie (a beggar) and the names MenziesMenziesMenzies is a Scottish surname probably derived, like its Gaelic form Méinnearach, from the Norman name Mesnières.The name is historically pronounced , since the was a surrogate for the letter . Today it is often given its spelling pronunciation...

, FinzeanFinzeanFinzean is a rural community, electoral polling district, community council area and former ecclesiastical parish, which forms the southern part of the Parish of Birse, Aberdeenshire, Scotland...

, Culzean, MackenzieMackenzie (surname)Mackenzie, MacKenzie, and McKenzie, are Scottish surnames. Originally pronounced in Scots, the z representing the old Middle Scots letter, yogh. The names are Anglicised forms of the Scottish Gaelic MacCoinnich, which is a patronymic form of the personal name Coinneach. The personal name means...

etc. (As a result of the lack of education in Scots, Mackenzie is now generally pronounced with a /z/ following the perceived realisation of the written form, as more controversially is sometimes Menzies.)

Silent letters

- The word final 'd' in nd and ld but often pronounced in derived forms. Sometimes simply 'n' and 'l' or 'n'' and 'l'' e.g. auld (old) and haund (hand) etc.

- 't' in medial cht ('ch' = /x/) and st and before final en e.g. fochten (fought), thristle (thistle) and also the 't' in aften (often) etc.

- 't' in word final ct and pt but often pronounced in derived forms e.g. respect and accept etc.

Vowels

For a historical overview see the Phonological history of Scots.The vowel system of Scots:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8a | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 1. Generally merges with vowels 2, 4 or 8. 2. Merges with vowels 1 and 8. in central dialects and vowel 2 in Northern dialects. Also /(j)u/ or /(j)ʌ/ before /k/ and /x/ depending on dialect. 3. Vocalisation to /o/ may occur before /k/. 4. Some mergers with vowel 5. |

| short /əi/ long /aɪ/ |

/i/ | /e, i/1 | /e/ | /o/ | /u/ | /ø/2 | /eː/ | /əi/ | /oe/ | /əi/ | /iː/ | /ɑː, ɔː/ | /ʌu/3 | /ju/ | /ɪ/ | /ɛ/ | /ɑ, a/ | /ɔ/4 | /ʌ/ |

In Scots, vowel length

Vowel length

In linguistics, vowel length is the perceived duration of a vowel sound. Often the chroneme, or the "longness", acts like a consonant, and may etymologically be one, such as in Australian English. While not distinctive in most dialects of English, vowel length is an important phonemic factor in...

is usually conditioned by the Scottish Vowel Length Rule

Scottish Vowel Length Rule

The Scottish vowel length rule, also known as Aitken's law after Professor A.J. Aitken, who formulated it, describes how vowel length in Scots, Scottish English, and to some extent Mid Ulster English, is conditioned by environment.- Phonemes :...

. Words which differ only slightly in pronunciation from Scottish English

Scottish English

Scottish English refers to the varieties of English spoken in Scotland. It may or may not be considered distinct from the Scots language. It is always considered distinct from Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic language....

are generally spelled as in English. Other words may be spelt the same but differ in pronunciation, for example: aunt, swap, want and wash with /a/, bull, full v. and pull with /ʌ/, bind, find and wind v., etc. with /ɪ/.

- The unstressed vowel /ə/ may be represented by any vowel letter.

- a (vowel 17): usually /ɑ/, often /ɑː/ in south west and Ulster dialects, but /aː/ in Northern dialects. Note final a (vowel 12) in awa (away), twa (two) and wha (who) may also be /ɑː/, /ɔː/, /aː/ or /eː/ depending on dialect.

- au, aw (vowel 12) /ɑː/ or /ɔː/ in Southern, Central and Ulster dialects but /aː/ in Northern dialects, with au usually occurring in medial positions and aw in final positions. Sometimes a or a' representing L-vocalisation. The digraph aa also occurs, especially in written representations of the (/aː/) realisation im Northern and Insular dialects. The cluster 'auld' may also be /ʌul/ in Ulster, e.g. aw (all), cauld (cold), braw (handsome), faw (fall), snaw (snow), etc.

- ai (vowel 8) in initial and medial positions and a(consonant)e (vowel 4). The graphemes ae (vowel 4) and ay (vowel 8) generally occur in final positions. All generally /e(ː)/. Often /ɛ/ before /r/. The merger of vowel 8 with 4 has resulted in the digraph ai occurring in some words with vowel 4 and a(consonant)e occurring in some words with vowel 8, e.g. saip (soap), hale (whole), ane (one), ance (once), bane (bone), etc. and word final brae (slope) and day etc. The digraph ae also occurs for vowel 7 in dae (do), tae (too) and shae (shoe). In Northern dialects the vowel in the cluster 'ane' is often /i/ and after /w/ and dark /l/ the realisation /əi/ may occur. In Southern Scots and many Central and Ulster varieties ae, ane and ance may be realised /jeː/, /jɪn/ and /jɪns/ often written yae, yin and yince in dialect writing.

- ea, ei (vowel 3), has generally merged with /i(ː)/ (vowel 2) or /e(ː)/ (vowel 4 or 8) depending on dialect. /ɛ/ may occur before /r/. In Northern varieties the realisation may be /əi/ after /w/ and /ʍ/ and in the far north /əi/ may occur in all environments. deid (dead), heid (head), meat (food), clear etc.

- ee (vowels 2 and 11), e(Consonant)e (vowel 2). Occasionally ei and ie with ei generally before ch (/x/), but also in a few other words, and ie generally occurring before l and v. The realisation is generally /i(ː)/ but in Northen varieties may be /əi/ after /w/ and /ʍ/. Final vowel 11 (/iː/) may be /əi/ in Southern dialects. e.g. ee (eye), een (eyes), speir (enquire), steek (shut), here, etc. The digraph ea also occurs in a few words such as sea and tea.

- e (vowel 16): /ɛ/. bed, het (heated), yett (gate), etc.

- eu (vowel 7 before /k/ and /x/ see ui): /(j)u/ or /(j)ʌ/ depending on dialect. Sometimes u(consonant)e. Sometimes u phonetically and oo after Standard English also occur, e.g. beuk (book), eneuch (enough), ceuk (cook), leuk (look), teuk (took) etc.

- ew (vowel 14): /ju/. In Northern dialects a root final 'ew' may be /jʌu/. few, new, etc.

- i (Vowel 15): /ɪ/, but often varies between /ɪ/ and /ʌ/ especially after 'w' and 'wh'. /æ/ also occurs in Ulster before voiceless consonants. big, fit (foot), wid (wood), etc.

- i(consonant)e, y(consonant)e, ey (vowels 1, 8a and 10): /əi/ or /aɪ/. 'ay' is usually /e/ but /əi/ in ay (yes) and aye (always). In Dundee it is noticeably /ɛ/.

- o (vowel 18): /ɔ/ but often merging with vowel 5 (/o/) often spelled phonetically oa in dialect spellings such as boax (box), coarn (corn), Goad (God)joab (job) and oan (on) etc.

- oa (vowel 5): /o/.

- oi, oy (vowel 9)

- ow, owe (root final), seldom ou (vowel 13): /ʌu/. Before 'k' vocalisation to /o/ may occur especially in western and Ulster dialects. bowk (retch), bowe (bow), howe (hollow), knowe (knoll), cowp (overturn), yowe (ewe), etc.

- ou the general literary spelling of vowel 6. Also u(consonant)e in some words: /u/ the former often represented by oo, a 19th century borrowing from Standard English. Root final /ʌu/ may occur in Southern dialects. cou (cow), broun (brown), hoose (house), moose (mouse) etc.

- u (vowel 19): /ʌ/. but, cut, etc.

- ui, the usual literary spelling of vowel 7 (except before /k/ and /x/ see eu), the spelling u(consonant)e also occurred, especially before nasals, and oo from the spelling of Standard English cognates: /ø/ in conservative dialects. In parts of FifeFifeFife is a council area and former county of Scotland. It is situated between the Firth of Tay and the Firth of Forth, with inland boundaries to Perth and Kinross and Clackmannanshire...

, DundeeDundeeDundee is the fourth-largest city in Scotland and the 39th most populous settlement in the United Kingdom. It lies within the eastern central Lowlands on the north bank of the Firth of Tay, which feeds into the North Sea...

and north AntrimCounty AntrimCounty Antrim is one of six counties that form Northern Ireland, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland. Adjoined to the north-east shore of Lough Neagh, the county covers an area of 2,844 km², with a population of approximately 616,000...

/e/. In Northern dialects usually /i/ but /wi/ after /ɡ/ and /k/ often spelled ee in dialect writing, and also /u/ before /r/ in some areas e.g. fuird (ford). Mid Down and Donegal dialects have /i/. In central and north Down dialects merger with vowel 15 (/ɪ/) occurs when short and vowel 8 (/eː/) when long, often written ai in dialect writing, e.g. buird (board), buit (boot), cuit (ankle), fluir (floor), guid (good), schuil (school), etc. In central dialects uise v. and uiss n. (use) are [jeːz] and [jɪs].

Grammar

Not all of the following features are exclusive to Scots and may also occur in some varieties of English.Definite article

The is used before the names of seasons, days of the week, many nouns, diseases, trades and occupations, sciences and academic subjects. It is also often used in place of the indefinite article and instead of a possessive pronoun: the hairst (autumn), the Wadensday (Wednesday), awa tae the kirk (off to church), the nou (at the moment), the day (today), the haingles (influenza), the Laitin (Latin), The deuk ett the bit breid (The duck ate a piece of bread), the wife (my wife) etc.Nouns

Nouns usually form their plural in -(e)s but some irregular plurals occur: ee/een (eye/eyes), cauf/caur (calf/calves), horse/horse (horse/horses), cou/kye (cow/cows), shae/shuin (shoe/shoes).Nouns of measure and quantity unchanged in the plural: fower fit (four feet), twa mile (two miles), five pund (five pounds), three hunderwecht (three hundredweight).

Regular plurals include laifs (loaves), leafs (leaves), shelfs (shelves) and wifes (wives).

Personal and possessive pronouns

| English | Scots |

|---|---|

| I, me, myself, mine, my | A, me, masel, mines, ma |

| we, us, ourselves, our | we, (h)us, oorsels~wirsels, oor~wir |

| you (singular), you (plural), yourself, yours, your | you~ye, you(se)~ye(se), yoursel~yersel |

| they, them, themselves, theirs, their | thay, thaim, thaimsels~thairsels, thairs, thair |

Relative pronoun

The relative pronoun is that ('at is an alternative form borrowed from Norse but can also be arrived at by contraction) for all persons and numbers, but may be left out Thar's no monie fowk (that) byds in that glen (There aren't many people who live in that glen). The anglicised forms wha, wham, whase 'who, whom, whose', and the older whilk 'which' are literary affectations; whilk is only used after a statement He said he'd tint it, whilk wis no whit we wantit tae hear (he said he'd lost it, which is not what we wanted to hear". The possessive is formed by adding s or by using an appropriate pronoun The wifie that's hoose gat burnt (the woman whose house was burnt), the wumman that her dochter gat mairit (the woman whose daughter got married); the men that thair boat wis tint (the men whose boat was lost).A third adjective/adverb yon/yonder, thon/thonder indicating something at some distance D'ye see yon/thon hoose ower yonder/thonder? Also thae (those) and thir (these), the plurals of that and this respectively.

In Northern Scots this and that are also used where "these" and "those" would be in Standard English.

Other pronouns

| English | Scots |

|---|---|

| this, these | this, thir |

| that, those | that, thae |

| anyone | onybody~oniebodie |

| anything | onything~oniething |

| nothing | nocht |

| everyone | awbody~awbodie |

| everything | awthing, ilkathing |

| both | baith |

| each | ilk |

| every | ilka |

| other | ither |

Modal verbs

The modal verbs mey (may), ocht tae/ocht ti (ought to), and sall (shallShall and will

Shall and will are both modal verbs in English used to express propositions about the future.-Usage:These modal verbs have been used in the past for a variety of meanings...

), are no longer used much in Scots but occurred historically and are still found in anglicised literary Scots. Can, shoud/shud (should), and will/wull are the preferred Scots forms.

Scots employs double modal constructions He'll no can come the day (He won't be able to come today), A micht coud come the morn (I may be able to come tomorrow), A uised tae coud dae it, but no nou (I used to be able to do it, but not now).

Negation occurs by using the adverb no, in the North East nae, as in A'm no comin (I'm not coming), A'll no learn ye (I will not teach you), or by using the suffix -na sometimes spelled nae , as in A dinna ken (I don't know), Thay canna come (They can't come), We coudna hae telt him (We couldn't have told him), and A hivna seen her (I haven't seen her).

The usage with no is preferred to that with -na with contractable auxiliary verbs like -ll for will, or in yes/no questions with any auxiliary He'll no come and Did he no come?

| English | Scots |

|---|---|

| are, aren't | are~ar, arena~arna |

| can, can't | can, canna |

| could, couldn't | coud~cud, coudna~cudna |

| dare, daren't | daur, daurna |

| did, didn't | did, didna |

| do, don't | dae, daena~dinna |

| had, hadn't | haed, haedna |

| have, haven't | hae, haena~hinna~hivna |

| might, mightn't | micht, michtna |

| must, mustn't | maun, maunna |

| need, needn't | need, needna |

| should, shouldn't | shoud~shud, shoudna~shudna |

| was, wasn't | wis, wisna |

| were, weren't | war, warna |

| will, won't | will~wul, winna~wunna |

| would, wouldn't | wad, wadna |

Present tense of verbs

The present tense of verbs adhere to the Northern subject ruleNorthern subject rule

The Northern Subject Rule is a grammatical pattern inherited from Northern Middle English. Present tense verbs may take the verbal ‑s suffix, except when they are directly adjacent to one of the personal pronouns I, you, we, or they as their subject...

whereby verbs end in -s in all persons and numbers except when a single personal pronoun is next to the verb, Thay say he's ower wee, Thaim that says he's ower wee, Thir lassies says he's ower wee (They say he's too small), etc. Thay're comin an aw but Five o thaim's comin, The lassies? Thay'v went but Ma brakes haes went. Thaim that comes first is serred first (Those who come first are served first). The trees growes green in the simmer (The trees grow green in summer).

Wis 'was' may replace war 'were', but not conversely: You war/wis thare.

Past tense and past participle of verbs

The regular past form of the weakGermanic weak verb

In Germanic languages, including English, weak verbs are by far the largest group of verbs, which are therefore often regarded as the norm, though historically they are not the oldest or most original group.-General description:...

or regular

Regular verb

A regular verb is any verb whose conjugation follows the typical grammatical inflections of the language to which it belongs. A verb that cannot be conjugated like this is called an irregular verb. All natural languages, to different extents, have a number of irregular verbs...

verbs is -it, -t or -ed, according to the preceding consonant or vowel: The -ed ending can be written -'d if the e is silent or has no purpose.

- hurtit (hurted), skelpit (smacked), mendit (mended);

- traivelt (travelled), raxt (reached), telt (told), kent (knew/known);

- cleaned/claen'd, scrieved/skreiv'd (scribbled), speired/speir'd (asked), dee'd (died).

Many verbs have (strong

Germanic strong verb

In the Germanic languages, a strong verb is one which marks its past tense by means of ablaut. In English, these are verbs like sing, sang, sung...

or irregular

Irregular verb

In contrast to regular verbs, irregular verbs are those verbs that fall outside the standard patterns of conjugation in the languages in which they occur. The idea of an irregular verb is important in second language acquisition, where the verb paradigms of a foreign language are learned...

) forms which are distinctive from Standard English (two forms connected with ~ means that they are variants):

- bite/bate/bitten (bite/bit/bitten), drive/drave/driven~dreen (drive/drove/driven), ride/rade/ridden (ride/rode/ridden), rive/rave/riven (rive/rived/riven), rise/rase/risen (rise/rose/risen), slide/slade/slidden (slide/slid/slid), slite/slate/slitten (slit/slit/slit), write/wrate/written or Mid Northern vrit/vrat/vrutten (write/wrote/written);

- bind/band/bund (bind/bound/bound), clim/clam/clum (climb/climbed/climbed), finnd/fand/fund (find/found/found), fling/flang/flung (fling/flung/flung), hing/hang/hung (hang/hung/hung), rin/ran/run (run/ran/run), spin/span/spun (spin/spun/spun), stick/stack/stuck (stick/stuck/stuck), drink/drank/drucken~drunk (drink/drank/drunk);

- creep/crap/cruppen (creep/crept/crept), greet/grat/grutten (weep/wept/wept), sweit/swat/swutten (sweat/sweat/sweat), weet/wat/watten (wet/wet/wet), pit/pat/pitten (put/put/put), sit/sat/sitten (sit/sat/sat), spit/spat/sputten~spitten (spit/spat/spat);

- brek~brak/brak/brokken~brakken (break/broke/broken), get~git/gat/gotten (get/got/got[ten]), speak/spak/spoken (speak/spoke/spoken), fecht/focht/fochten (fight/fought/fought);

- beir/buir~bore/born(e) (bear/bore/borne), sweir/swuir~swore/sworn (swear/swore/sworne), teir/tuir~tore/torn (tear/tore/torn), weir/wuir~wore/worn (wear/wore/worn);

- cast/cuist/casten~cuisten (cast/cast/cast), lat/luit/latten~luitten (let/let/let), staund/stuid/stuiden (stand/stood/stood), fesh/fuish/feshen~fuishen (fetch/fetched), thrash/thruish/thrashen~thruishen (thresh/threshed/threshed), wash/wuish/washen~wuishen (wash/washed/washed);

- bake/bakit~beuk/bakken (bake/baked/baked), lauch/leuch/lauchen~leuchen (laugh/laughed/laughed), shak/sheuk/shakken~sheuken (shake/shook/shaken), tak/teuk/taen (take/took/taken);

- gae/gaed/gane (go/went/gone), gie/gied/gien (give/gave/given), hae/haed/haen (have/had/had);

- chuise/chuised/chosen (choose/chose/chosen), soum/soumed/soumed (swim/swam/swum), sell/selt~sauld/selt~sauld (sell/sold/sold), tell/telt~tauld/telt~tauld (tell/told/told), cut/cuttit/cuttit (cut/cut/cut), hurt/hurtit/hurtit (hurt/hurt/hurt), keep/keepit/keepit (keep/kept/kept), sleep/sleepit/sleepit (sleep/slept/slept).

Present participle

The present participle and gerundGerund

In linguistics* As applied to English, it refers to the usage of a verb as a noun ....

in are now usually /ən/ but may still be differentiated /ən/ and /in/ in Southern Scots and, /ən/ and /ɪn/ North Northern Scots.

Adverbs

Adverbs are usually of the same form as the verb root or adjective especially after verbs. Haein a real guid day (Having a really good day). She's awfu fauchelt (She's awfully tired).Adverbs are also formed with -s, -lies, lins, gate(s)and wey(s) -wey, whiles/whyls (at times), mebbes (perhaps), brawlies (splendidly), geylies (pretty well), aiblins (perhaps), airselins (backwards), hauflins (partly), hidlins (secretly), maistlins (almost), awgates (always, everywhere), ilkagate (everywhere), onygate/oniegate (anyhow), ilkawey (everywhere), onywey/oniewey (anyhow, anywhere), endweys (straight ahead), whit wey (how, why).

Prepositions

| English | Scots |

|---|---|

| above, upper, topmost | abuin, buiner, buinmaist |

| below, lower, lowest | ablo, nether, blomaist |

| along | alang |

| about | aboot |

| about (concerning) | anent |

| across | athort |

| before | afore |

| behind | ahint |

| beneath | aneath~anaith |

| beside | aside~asyd |

| between | atween~atwein~atweesh~atweish |

| beyond | ayont |

| from | f(r)ae |

| into | intae~inti~intil |

Interrogative words

| English | Scots |

|---|---|

| who? | wha? |

| what? | whit? |

| when? | whan? |

| where? | whaur? |

| why? | why/how? |

| which? | whilk? |

| how? | hou? |

In the North East, the 'wh' in the above words is pronounced /f/.

Word order

Scots prefers the word order He turnt oot the licht to 'He turned the light out' and Gie's it (Give us it) to 'Give it to me'.Certain verbs are often used progressively He wis thinkin he wad tell her, He wis wantin tae tell her.

Verbs of motion may be dropped before an adverb or adverbial phrase of motion A'm awa tae ma bed, That's me awa hame, A'll intae the hoose an see him.

Diminutives

DiminutiveDiminutive

In language structure, a diminutive, or diminutive form , is a formation of a word used to convey a slight degree of the root meaning, smallness of the object or quality named, encapsulation, intimacy, or endearment...

s in -ie, burnie small burn (stream), feardie/feartie (frightened person, coward), gamie (gamekeeper), kiltie (kilted soldier), postie (postman), wifie (woman, also used in Geordie

Geordie

Geordie is a regional nickname for a person from the Tyneside region of the north east of England, or the name of the English-language dialect spoken by its inhabitants...

dialect), rhodie (rhododendron), and also in -ock, bittock (little bit), playock (toy, plaything), sourock (sorrel) and Northern –ag, bairnag (little), bairn (child, common in Geordie dialect), Cheordag (Geordie), -ockie, hooseockie (small house), wifeockie (little woman), both influenced by the Scottish Gaelic diminutive -ag (-óg in Irish Gaelic).

Subordinate clauses

Verbless subordinate clauses introduced by an (and) express surprise or indignation. She haed tae walk the hale lenth o the road an her seiven month pregnant (and she seven months pregnant). He telt me tae rin an me wi ma sair leg (and me with my sore leg).Suffixes

- Negative na: /ɑ/, /ɪ/ or /e/ depending on dialect. Also 'nae' or 'y' e.g. canna (can't), dinna (don't) and maunna (mustn't).

- fu (ful): /u/, /ɪ/, /ɑ/ or /e/ depending on dialect. Also 'fu'', 'fie', 'fy', 'fae' and 'fa'.

- The word ending ae: /ɑ/, /ɪ/ or /e/ depending on dialect. Also 'a', 'ow' or 'y', for example: arrae (arrow), barrae (barrow) and windae (window), etc.

Numbers

Ordinal numbers end mostly in t: seicont, fowert, fift, saxt— (second, fourth, fifth, sixth) etc., but note also first, thrid/third— (first, third).| English | Scots |

|---|---|

| one, first | ane~ae, first |

| two, second | twa, seicont |

| three, third | three~thrie, thrid~third |

| four, fourth | fower, fowert |

| five, fifth | five, fift |

| six, sixth | sax, saxt |

| seven, seventh | seiven~seivin, seivent~seivint |

| eight, eighth | aicht~echt, aicht~echt |

| nine, ninth | nine~nyn, nint~nynt |

| ten, tenth | ten, tent |

| eleven, eleventh | eleiven~eleivin, eleivent~eleivint |

| twelve, twelfth | twal, tawlt |

Ae /eː/, /jeː/ is used as an adjective before a noun such as : The Ae Hoose (The One House), Ae laddie an twa lassies (One boy and two girls). Ane is pronounced variously, depending on dialect, /en/, /jɪn/ in many Central

Central Scots

Central Scots is a group of dialects of Scots language. It was spoken by Robert Burns.Central Scots is spoken from Fife and Perthshire to the Lothians and Wigtownshire, often split into North East Central Scots and South East Central Scots , West Central Scots and South West Central Scots ....

and Southern varieties, /in/ in some Northern

Northern Scots

Northern Scots refers to the dialects of Modern Scots traditionally spoken in eastern parts of the north of Scotland.The dialect is generally divided into:*North Northern spoken in Caithness, Easter Ross and the Black Isle....

and Insular

Insular Scots

Insular Scots comprises varieties of Lowland Scots generally subdivided into:*Shetlandic*OrcadianBoth dialects share much Norn vocabulary, Shetlandic more so, than does any other Scots dialect, perhaps because they both were under strong Scandinavian influence in their recent past.It should not be...

varieties, and /wan/, often written yin, een and wan in dialect writing.

The impersonal form of 'one' is a body as in A body can niver bide wi a body's sel (One can never live by oneself).

Times of day

| English | Scots |

|---|---|

| morning | forenuin |

| midday | twal-oors |

| afternoon | efternuin~eftirnuin |

| evening | forenicht |

| dusk, twilight | dayligaun, gloamin |

| midnight | midnicht |

| early morning | wee-oors |

Literature

The eighteenth century Scots revival was initiated by writers such as Allan RamsayAllan Ramsay (poet)

Allan Ramsay was a Scottish poet , playwright, publisher, librarian and wig-maker.-Life and career:...

and Robert Fergusson

Robert Fergusson

Robert Fergusson was a Scottish poet. After formal education at the University of St Andrews, Fergusson followed an essentially bohemian life course in Edinburgh, the city of his birth, then at the height of intellectual and cultural ferment as part of the Scottish enlightenment...

, and later continued by writers such as Robert Burns

Robert Burns

Robert Burns was a Scottish poet and a lyricist. He is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland, and is celebrated worldwide...

and Sir Walter Scott

Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet was a Scottish historical novelist, playwright, and poet, popular throughout much of the world during his time....

. Scott introduced vernacular dialogue to his novels. Other well-known authors like Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson was a Scottish novelist, poet, essayist and travel writer. His best-known books include Treasure Island, Kidnapped, and Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde....

, William Alexander, George MacDonald

George MacDonald

George MacDonald was a Scottish author, poet, and Christian minister.Known particularly for his poignant fairy tales and fantasy novels, George MacDonald inspired many authors, such as W. H. Auden, J. R. R. Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, E. Nesbit and Madeleine L'Engle. It was C.S...

, J. M. Barrie

J. M. Barrie

Sir James Matthew Barrie, 1st Baronet, OM was a Scottish author and dramatist, best remembered today as the creator of Peter Pan. The child of a family of small-town weavers, he was educated in Scotland. He moved to London, where he developed a career as a novelist and playwright...

and other members of the Kailyard school

Kailyard school

The Kailyard school of Scottish fiction was developed about the 1890s as a reaction against what was seen as increasingly coarse writing representing Scottish life complete with all its blemishes. It has been considered as being an overly sentimental representation of rural life, cleansed of real...

like Ian Maclaren

Ian Maclaren

Ian Maclaren was a Scottish author and theologian.He was the son of John Watson, a civil servant...

also wrote in Scots or used it in dialogue, as did George Douglas Brown

George Douglas Brown

George Douglas Brown was a Scottish novelist, best known for his highly influential realist novel The House with the Green Shutters , which was published the year before his death at the age of 33.-Life and work:...

whose writing is regarded as a useful corrective to the more roseate presentations of the kailyard school.

In the Victorian era

Victorian era

The Victorian era of British history was the period of Queen Victoria's reign from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. It was a long period of peace, prosperity, refined sensibilities and national self-confidence...

popular Scottish newspapers regularly included articles and commentary in the vernacular, often of unprecedented proportions.

In the early twentieth century, a renaissance

Scottish Renaissance

The Scottish Renaissance was a mainly literary movement of the early to mid 20th century that can be seen as the Scottish version of modernism. It is sometimes referred to as the Scottish literary renaissance, although its influence went beyond literature into music, visual arts, and politics...

in the use of Scots occurred, its most vocal figure being Hugh MacDiarmid

Hugh MacDiarmid

Hugh MacDiarmid is the pen name of Christopher Murray Grieve , a significant Scottish poet of the 20th century. He was instrumental in creating a Scottish version of modernism and was a leading light in the Scottish Renaissance of the 20th century...

whose benchmark poem A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle

A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle

A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle is a long poem by Hugh MacDiarmid written in Scots and published in 1926. It is composed as a form of monologue with influences from stream of consciousness genres of writing...

(1926) did much to demonstrate the power of Scots as a modern idiom. Other contemporaries were Douglas Young

Douglas Young (classicist)

Professor Douglas Young ; June 5, 1913 – October 23, 1973) was a Scottish poet, scholar, and translator. He was the leader of the Scottish National Party from 1942 to 1945.Young was born in Tayport, Fife...

, John Buchan

John Buchan, 1st Baron Tweedsmuir

John Buchan, 1st Baron Tweedsmuir was a Scottish novelist, historian and Unionist politician who served as Governor General of Canada, the 15th since Canadian Confederation....

, Sidney Goodsir Smith, Robert Garioch

Robert Garioch

Robert Garioch Sutherland, , was a Scottish poet and translator. His poetry was written almost exclusively in the Scots language, he was a key member in the literary revival of the language in the mid-20th century...

and Robert McLellan

Robert McLellan

Robert McLellan OBE was a Scottish dramatist and poet, mainly writing in the Scots language.-Early life and education:McLellan was born in 1907 at Linmill, a fruit farm in Kirkfieldbank in the Clyde valley, the home of his maternal grandparents. He was educated at Bearsden Academy in Glasgow...

. The revival extended to verse and other literature.

In 1983 William Laughton Lorimer

William Laughton Lorimer

William Laughton Lorimer was born at Strathmartine on the outskirts of Dundee, Scotland. He was educated at the High School of Dundee, Fettes College, and Trinity College, Oxford. He is best known for the translation of the New Testament into Lowland Scots...

's translation of the New Testament from the original Greek was published.

Sample texts

From Hallow-Fair (Robert Fergusson 1750–1774)- At Hallowmas, whan nights grow lang,

- And starnies shine fu' clear,

- Whan fock, the nippin cauld to bang,

- Their winter hap-warms wear,

- Near Edinbrough a fair there hads,

- I wat there's nane whase name is,

- For strappin dames an sturdy lads,

- And cap and stoup, mair famous

- Than it that day.

- Upo' the tap o' ilka lum

- The sun bagan to keek,

- And bad the trig made maidens come

- A sightly joe to seek

- At Hallow-fair, whare browsters rare

- Keep gude ale on the gantries,

- And dinna scrimp ye o' a skair

- O' kebbucks frae their pantries,

- Fu' saut that day.

From The Maker to Posterity (Robert Louis Stevenson 1850–1894)

- Far 'yont amang the years to be

- When a' we think, an' a' we see,

- An' a' we luve, `s been dung ajee

- By time's rouch shouther,

- An' what was richt and wrang for me

- Lies mangled throu'ther,

- It's possible - it's hardly mair -

- That some ane, ripin' after lear -

- Some auld professor or young heir,

- If still there's either -

- May find an' read me, an' be sair

- Perplexed, puir brither!

- "What tongue does your auld bookie speak?"

- He'll spier; an' I, his mou to steik:

- "No bein' fit to write in Greek,

- I write in Lallan,

- Dear to my heart as the peat reek,

- Auld as Tantallon.

- "Few spak it then, an' noo there's nane.

- My puir auld sangs lie a' their lane,

- Their sense, that aince was braw an' plain,

- Tint a'thegether,

- Like runes upon a standin' stane

- Amang the heather.

From The House with the Green Shutters (George Douglas Brown 1869–1902)

- He was born the day the brig on the Fleckie Road gaed down, in the year o' the great flood; and since the great flood it’s twelve year come Lammas. Rab Tosh o' Fleckie’s wife was heavy-footed at the time, and Doctor Munn had been a' nicht wi' her, and when he came to Barbie Water in the morning it was roaring wide frae bank to brae; where the brig should have been there was naething but the swashing o' the yellow waves. Munn had to drive a' the way round to the Fechars brig, and in parts of the road, the water was so deep that it lapped his horse’s bellyband.

- A' this time Mistress Gourlay was skirling in her pains an praying to God she micht dee. Gourlay had been a great cronie o' Munn’s, but he quarrelled him for being late; he had trysted him, ye see, for the occasion, and he had been twenty times at the yett to look for him-ye ken how little he would stomach that; he was ready to brust wi' anger. Munn, mad for the want o' sleep and wat to the bane, swüre back at him; and than Goulay wadna let him near his wife! Ye mind what an awful day it was; the thunder roared as if the heavens were tumbling on the world, and the lichtnin sent the trees daudin on the roads, and folk hid below their beds an prayed-they thocht it was the judgment! But Gourlay rammed his black stepper in the shafts and drave like the devil o' Hell to Skeighan Drone, where there was a young doctor. The lad was feared to come, but Gourlay swore by God that he should, and he gaired him. In a' the countryside, driving like his that day was never kenned or heard tell o'; they were back within the hour!

- I saw them gallop up Main Street; lichtin struck the ground before them; the young doctor covered his face wi' his hands, and the horse nichered wi' fear an tried to wheel, but Gourlay stood up in the gig and lashed him on though the fire. It was thocht for lang that Mrs. Gourlay would die, and she was never the same womman after. Atweel aye, sirs. Gorlay has that morning's work to blame for the poor wife he has now.

From Embro to the Ploy (Robert Garioch 1909 - 1981)