Old Latin

Encyclopedia

Old Latin refers to the Latin language in the period before the age of Classical Latin

; that is, all Latin

before 75 BC

. The term prisca Latinitas distinguishes it in New Latin

and Contemporary Latin from vetus Latina, in which "old" has another meaning.

The use of "old", "early" and "archaic" has been standard in publications of the corpus of Old Latin writings since at least the 18th century. The definition is not arbitrary but these terms refer to writings with spelling conventions and word forms not generally found in works written under the Roman Empire

. This article presents some of the major differences.

, both dating to at least as early as the late Roman republic

. In that time period Marcus Tullius Cicero, along with others, noted that the language he used every day, presumably the upper-class city Latin, included lexical items and phrases that were heirlooms from a previous time, which he called verborum vetustas prisca, translated as "the old age/time of language."

During the classical period, Prisca Latinitas, Prisca Latina and other expressions using the adjective always meant these remnants of a previous language, which, in the Roman philology, was taken to be much older in fact than it really was. Viri prisci, "old-time men," were the population of Latium

before the foundation of Rome.

period, when Classical Latin was behind them, the Latin- and Greek-speaking grammarians were faced with multiple phases, or styles, within the language. Isidore of Seville

reports a classification scheme that had come into existence in or before his time: "the four Latins" ("Latinas autem linguas quatuor esse quidam dixerunt"). They were Prisca, spoken before the founding of Rome, when Janus

and Saturn

ruled Latium

, to which he dated the Carmen Saliare

; Latina, dated from the time of king Latinus

, in which period he placed the laws of the Twelve Tables

; Romana, essentially equal to Classical Latin; and Mixta, "mixed" Classical Latin and Vulgar Latin

, which is known today as Late Latin

. The scheme persisted with little change for some thousand years after Isidore.

used the definition:

Although the differences are striking and can be easily identified by Latin readers, they are not such as to cause a language barrier. Latin speakers of the empire had no reported trouble understanding old Latin, except for the few texts that must date from the time of the kings

, mainly songs. Thus the laws of the twelve tables

, which began the republic, were comprehensible, but the Carmen Saliare

, probably written under Numa Pompilius

, was not entirely.

An opinion concerning Old Latin, of a Roman man of letters in the middle Republic, does survive: the historian, Polybius

, read "the first treaty between Rome and Carthage", which he says "dates from the consulship of Lucius Junius Brutus

and Marcus Horatius, the first consuls after the expulsion of the kings." Knowledge of the early consuls is somewhat obscure, but Polybius also states that the treaty was formulated 28 years after Xerxes I crossed into Greece; that is, in 452 BC, about the time of the Decemviri

, when the constitution of the Roman republic

was being defined. Polybius says of the language of the treaty: "...the ancient Roman language differs so much from the modern that it can only be partially made out, and that after much application by the most intelligent men."

There is no sharp distinction between Old Latin as it was spoken for most of the republic and classical Latin, but the earlier grades into the later. The end of the republic was too late a termination for compilers after Wordsworth; Charles Edwin Bennett

said:

Old Latin authored works began in the 3rd century BC. These are complete or nearly complete works under their own name surviving as manuscripts copied from other manuscripts in whatever script was current at the time. In addition are fragments of works quoted in other authors.

Old Latin authored works began in the 3rd century BC. These are complete or nearly complete works under their own name surviving as manuscripts copied from other manuscripts in whatever script was current at the time. In addition are fragments of works quoted in other authors.

Numerous inscriptions placed by various methods (painting, engraving, embossing) on their original media survive just as they were except for the ravages of time. Some of these were copied from other inscriptions. No inscription can be earlier than the introduction of the Greek alphabet into Italy

but none survive from that early date. The imprecision of archaeological dating makes precise dates impossible but the earliest survivals are probably from the 6th century BC. Some of the texts, however, surviving as fragments in the works of classical authors, had to have been composed earlier than the republic, in the monarchy

. These are listed below.

. The writing conventions varied by time and place until classical conventions prevailed. The works of authors in manuscript form were copied over into the scripts of other times. The original writing does not exist.

These differences did not necessarily run concurrently with each other and were not universal; that is, c was used for both c and g.

Phonological characteristics of older Latin:

Phonological characteristics of older Latin:

s are distinguished by grammatical case

, a word with a termination, or suffix, determining its use in the sentence, such as subject, predicate, etc. A case for a given word is formed by suffixing a case ending to a part of the word common to all its cases called a stem

. Stems are classified by their last letters as vowel or consonant. Vowel stems are formed by adding a suffix to a shorter and more ancient segment called a root

. Consonant stems are the root (roots end in consonants). The combination of the last letter of the stem and the case ending often results in an ending also called a case ending or termination. For example, the stem puella- receives a case ending -m to form the accusative case puellam in which the termination -am is evident.

In Classical Latin

textbooks the declensions are named from the letter ending the stem or First, Second, etc. to Fifth. A declension may be illustrated by a paradigm

, or listing of all the cases of a typical word. This method is less frequently applied to Old Latin, and with less validity. In contrast to Classical Latin, Old Latin reflects the evolution of the language from an unknown hypothetical ancestor spoken in Latium

. The endings are multiple. Their use depends on time and locality. Any paradigm selected would be subject to these constraints and if applied to the language universally would result in false constructs, hypothetical words not attested in the Old Latin corpus. Nevertheless the endings are illustrated below by quasi-classical paradigms. Alternative endings from different stages of development are given, but they may not be attested for the word of the paradigm. For example, in the Second Declension, *campoe "fields" is unattested, but poploe "peoples" is attested.

of noun

s of this declension

usually end in and are typically feminine.

A nominative case ending of –s in a few masculines indicates the nominative singular case ending may have been originally : paricidas for later paricida, but the tended to get lost. In the nominative plural, -ī replaced original -s as in the genitive singular.

In the genitive singular, the was replaced with from the second declension, the resulting diphthong shortening to subsequently becoming . In a few cases the replacement did not take place: pater familiās. Explanations of the late inscriptional are speculative. In the genitive plural, the regular ending is –āsōm (classical –ārum by rhotacism

and shortening of final o) but some nouns borrow –om (classical –um) from the second declension.

In the dative singular the final i is either long or short. The ending becomes –ae, –a (Feronia) or –e (Fortune).

In the accusative singular, Latin regularly shortens a vowel before final m.

In the ablative singular, –d was regularly lost after a long vowel. In the dative and ablative plural, the –abos descending from Indo-European *–ābhos is used for feminines only (deabus). *–ais > –eis > īs is adapted from –ois of the o-declension.

In the vocative singular, an original short a merged with the shortened a of the nominative.

The locative case would not apply to such a meaning as puella, so Roma, which is singular, and Syracusae, which is plural, have been substituted. The locative plural has already merged with the –eis form of the ablative.

. Classical Latin evidences the development ŏ > ŭ. Nouns of this declension are either masculine or neuter.

Nominative singulars ending in -ros or -ris syncopate

the -os: ager not ageros. The nominative plural masculine follows two lines of development, each leaving a trail of endings. Roman generalizes the Indo-European pronominal ending *-oi. The sequence is The "provincial texts" generalize from the Indo-European nominative plural ending *-ōs appearing in the Third Declension: *-ōs >-ēs, -eis, -īs, from 190 BC on.

In the genitive singular, –ī is earliest, alternating later with –ei: populi Romanei, "of the Roman In the genitive plural, -om and -um (or -ōm and -ūm) from Indo-European *-ōm survived in classical Latin "words for coins and measures"; otherwise classical has -ōrum by analogy with 1st declension .

In the dative singular, if the Praenestine Fibula is a fraud, Numasioi, the only instance of –ōi, does not count and the Old Latin ending must be –ō.

In the vocative singular, some nouns lose the –e, (0 ending) but not necessarily the same as in classical Latin. The -e alternates regularly with -us. The vocative plural was the same as the nominative plural. Except for some singular forms that were like the genitive, the locative was captured by the ablative case in all Italic languages prior to Old Latin.

For the consonant declension, in the nominative singular, the -s was affixed directly to the stem consonant, but the combination of the two consonants produced modified nominatives over the Old Latin period. The case appears in different stages of modification in different words diachronically. The nominative as rēgs instead of rēx is an orthographic feature of Old Latin; the letter x was seldom used alone (as in the classical period) to designate the /ks/ or /gs/ sound, but instead, was written as either 'ks', 'cs', or even 'xs'. Often a collapse or syncope/apocope

of the full nominative occurs: Old Latin nominus > Classical Latin nomen; hominus > homo; Caesarus > Caesar. The Latin neuter form (not shown) is the Indo-European nominative without stem ending; for example, cor < *cord "heart."

The genitive singular endings include -is < -es and -us < *-os. In the genitive plural, some forms appear to affix the case ending to the genitive singular rather than the stem:

In the dative singular, -ī succeeded -ēI and -ē after 200 BC.

In the accusative singular, -em < *-ṃ after a consonant.

In the ablative singular, the -d was lost after 200 BC. In the dative and ablative plural, the early poets sometimes used -būs.

In the locative singular, the earliest form is like the dative but over the period assimilated to the ablative.

While the commonest ending in the nominative in both the singular and plural forms is '-ēs' (i.e. 'rēs, rĕī'), there have been recorded a few instances of either a shortened 'e' with the addition of a consonantal 'i', as in 'reis', or the abandonment of the nature of the 'e-stem' declension (i.e. 'res, rei').

The genitive in the singular functions as the second declension: 'rĕī' (the breve above the 'e' is the result of a voiceless 'r' preceding a vowel that has no solid nature at the time of the Old Latin's use). The genitive plural, in a like manner to the second declension, is formed with an '-ēsōm', primarily.

The dative is generally formed with an unstressed '-ei' in the singular, and an '-ēbos' in the plural.

The accusative, like all the other declensions, keeps the final 'm' to shorten the inherently long vowel in the singular: 'rem', and elongates it again with a final 's' in the plural: 'rēs'.

The ablative singular is as the pronouns and the 3rd person practical: 'rēd', voiceless to keep the long 'e'. The plural is generally like the dative plural but sometimes formed with an '-rīs'.

The locative functions exactly in the singular as it does in the plural, with a short '-eis' as the 1st although there are no singular-based city names in the singular besides the occasional 'Athenseis'.

and Umbrian

.

Classical Latin

Classical Latin in simplest terms is the socio-linguistic register of the Latin language regarded by the enfranchised and empowered populations of the late Roman republic and the Roman empire as good Latin. Most writers during this time made use of it...

; that is, all Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

before 75 BC

75 BC

Year 75 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Octavius and Cotta...

. The term prisca Latinitas distinguishes it in New Latin

New Latin

The term New Latin, or Neo-Latin, is used to describe the Latin language used in original works created between c. 1500 and c. 1900. Among other uses, Latin during this period was employed in scholarly and scientific publications...

and Contemporary Latin from vetus Latina, in which "old" has another meaning.

The use of "old", "early" and "archaic" has been standard in publications of the corpus of Old Latin writings since at least the 18th century. The definition is not arbitrary but these terms refer to writings with spelling conventions and word forms not generally found in works written under the Roman Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

. This article presents some of the major differences.

The old-time language

The concept of Old Latin (Prisca Latinitas) is as old as the concept of Classical LatinClassical Latin

Classical Latin in simplest terms is the socio-linguistic register of the Latin language regarded by the enfranchised and empowered populations of the late Roman republic and the Roman empire as good Latin. Most writers during this time made use of it...

, both dating to at least as early as the late Roman republic

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

. In that time period Marcus Tullius Cicero, along with others, noted that the language he used every day, presumably the upper-class city Latin, included lexical items and phrases that were heirlooms from a previous time, which he called verborum vetustas prisca, translated as "the old age/time of language."

During the classical period, Prisca Latinitas, Prisca Latina and other expressions using the adjective always meant these remnants of a previous language, which, in the Roman philology, was taken to be much older in fact than it really was. Viri prisci, "old-time men," were the population of Latium

Latium

Lazio is one of the 20 administrative regions of Italy, situated in the central peninsular section of the country. With about 5.7 million residents and a GDP of more than 170 billion euros, Lazio is the third most populated and the second richest region of Italy...

before the foundation of Rome.

The four Latins of Isidore

In the Late LatinLate Latin

Late Latin is the scholarly name for the written Latin of Late Antiquity. The English dictionary definition of Late Latin dates this period from the 3rd to the 6th centuries AD extending in Spain to the 7th. This somewhat ambiguously defined period fits between Classical Latin and Medieval Latin...

period, when Classical Latin was behind them, the Latin- and Greek-speaking grammarians were faced with multiple phases, or styles, within the language. Isidore of Seville

Isidore of Seville

Saint Isidore of Seville served as Archbishop of Seville for more than three decades and is considered, as the historian Montalembert put it in an oft-quoted phrase, "le dernier savant du monde ancien"...

reports a classification scheme that had come into existence in or before his time: "the four Latins" ("Latinas autem linguas quatuor esse quidam dixerunt"). They were Prisca, spoken before the founding of Rome, when Janus

Janus

-General:*Janus , the two-faced Roman god of gates, doors, doorways, beginnings, and endings*Janus , a moon of Saturn*Janus Patera, a shallow volcanic crater on Io, a moon of Jupiter...

and Saturn

Saturn (mythology)

In ancient Roman religion and myth, Saturn was a major god presiding over agriculture and the harvest time. His reign was depicted as a Golden Age of abundance and peace by many Roman authors. In medieval times he was known as the Roman god of agriculture, justice and strength. He held a sickle in...

ruled Latium

Latium

Lazio is one of the 20 administrative regions of Italy, situated in the central peninsular section of the country. With about 5.7 million residents and a GDP of more than 170 billion euros, Lazio is the third most populated and the second richest region of Italy...

, to which he dated the Carmen Saliare

Carmen Saliare

The Carmen Saliare is a fragment of archaic Latin, which played a part in the rituals performed by the Salii of Ancient Rome.The rituals revolved around Mars and Quirinus, and were performed in March and October...

; Latina, dated from the time of king Latinus

Latinus

Latinus was a figure in both Greek and Roman mythology.-Greek mythology:In Hesiod's Theogony, Latinus was the son of Odysseus and Circe who ruled the Tyrsenoi, presumably the Etruscans, with his brothers Ardeas and Telegonus...

, in which period he placed the laws of the Twelve Tables

Twelve Tables

The Law of the Twelve Tables was the ancient legislation that stood at the foundation of Roman law. The Law of the Twelve Tables formed the centrepiece of the constitution of the Roman Republic and the core of the mos maiorum...

; Romana, essentially equal to Classical Latin; and Mixta, "mixed" Classical Latin and Vulgar Latin

Vulgar Latin

Vulgar Latin is any of the nonstandard forms of Latin from which the Romance languages developed. Because of its nonstandard nature, it had no official orthography. All written works used Classical Latin, with very few exceptions...

, which is known today as Late Latin

Late Latin

Late Latin is the scholarly name for the written Latin of Late Antiquity. The English dictionary definition of Late Latin dates this period from the 3rd to the 6th centuries AD extending in Spain to the 7th. This somewhat ambiguously defined period fits between Classical Latin and Medieval Latin...

. The scheme persisted with little change for some thousand years after Isidore.

Old Latin

In 1874 John WordsworthJohn Wordsworth

The Right Reverend John Wordsworth was an English prelate. He was born at Harrow on the Hill, to the Reverend Christopher Wordsworth, nephew of the poet William Wordsworth...

used the definition:

By Early Latin I understand Latin of the whole period of the Republic, which is separated very strikingly, both in tone and in outward form, from that of the Empire.

Although the differences are striking and can be easily identified by Latin readers, they are not such as to cause a language barrier. Latin speakers of the empire had no reported trouble understanding old Latin, except for the few texts that must date from the time of the kings

King of Rome

The King of Rome was the chief magistrate of the Roman Kingdom. According to legend, the first king of Rome was Romulus, who founded the city in 753 BC upon the Palatine Hill. Seven legendary kings are said to have ruled Rome until 509 BC, when the last king was overthrown. These kings ruled for...

, mainly songs. Thus the laws of the twelve tables

Twelve Tables

The Law of the Twelve Tables was the ancient legislation that stood at the foundation of Roman law. The Law of the Twelve Tables formed the centrepiece of the constitution of the Roman Republic and the core of the mos maiorum...

, which began the republic, were comprehensible, but the Carmen Saliare

Carmen Saliare

The Carmen Saliare is a fragment of archaic Latin, which played a part in the rituals performed by the Salii of Ancient Rome.The rituals revolved around Mars and Quirinus, and were performed in March and October...

, probably written under Numa Pompilius

Numa Pompilius

Numa Pompilius was the legendary second king of Rome, succeeding Romulus. What tales are descended to us about him come from Valerius Antias, an author from the early part of the 1st century BC known through limited mentions of later authors , Dionysius of Halicarnassus circa 60BC-...

, was not entirely.

An opinion concerning Old Latin, of a Roman man of letters in the middle Republic, does survive: the historian, Polybius

Polybius

Polybius , Greek ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic Period noted for his work, The Histories, which covered the period of 220–146 BC in detail. The work describes in part the rise of the Roman Republic and its gradual domination over Greece...

, read "the first treaty between Rome and Carthage", which he says "dates from the consulship of Lucius Junius Brutus

Lucius Junius Brutus

Lucius Junius Brutus was the founder of the Roman Republic and traditionally one of the first consuls in 509 BC. He was claimed as an ancestor of the Roman gens Junia, including Marcus Junius Brutus, the most famous of Caesar's assassins.- Background :...

and Marcus Horatius, the first consuls after the expulsion of the kings." Knowledge of the early consuls is somewhat obscure, but Polybius also states that the treaty was formulated 28 years after Xerxes I crossed into Greece; that is, in 452 BC, about the time of the Decemviri

Decemviri

Decemviri is a Latin term meaning "Ten Men" which designates any such commission in the Roman Republic...

, when the constitution of the Roman republic

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

was being defined. Polybius says of the language of the treaty: "...the ancient Roman language differs so much from the modern that it can only be partially made out, and that after much application by the most intelligent men."

There is no sharp distinction between Old Latin as it was spoken for most of the republic and classical Latin, but the earlier grades into the later. The end of the republic was too late a termination for compilers after Wordsworth; Charles Edwin Bennett

Charles Edwin Bennett

Charles Edwin Bennett was an American classical scholar and the Goldwin Smith Professor of Latin at Cornell University...

said:

'Early Latin' is necessarily a somewhat vague term ... Bell, De locativi in prisca Latinitate vi et usu, Breslau, 1889, sets the later limit at 75 B.C. A definite date is really impossible, since archaic Latin does not terminate abruptly, but continues even down to imperial times.Bennett's own date of 100 BC. did not prevail but rather Bell's 75 BC. became the standard as expressed in the four-volume Loeb Library and other major compendia. Over the 377 years from 452 BC to 75 BC Old Latin evolved from being partially comprehensible by classicists with study to being easily read by men of letters.

Corpus

Numerous inscriptions placed by various methods (painting, engraving, embossing) on their original media survive just as they were except for the ravages of time. Some of these were copied from other inscriptions. No inscription can be earlier than the introduction of the Greek alphabet into Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

but none survive from that early date. The imprecision of archaeological dating makes precise dates impossible but the earliest survivals are probably from the 6th century BC. Some of the texts, however, surviving as fragments in the works of classical authors, had to have been composed earlier than the republic, in the monarchy

Roman Kingdom

The Roman Kingdom was the period of the ancient Roman civilization characterized by a monarchical form of government of the city of Rome and its territories....

. These are listed below.

Fragments and inscriptions

Notable Old Latin fragments with estimated dates include:- The Carmen SaliareCarmen SaliareThe Carmen Saliare is a fragment of archaic Latin, which played a part in the rituals performed by the Salii of Ancient Rome.The rituals revolved around Mars and Quirinus, and were performed in March and October...

(chant put forward in classical times as having been sung by the salian brotherhoodSaliiIn ancient Roman religion, the Salii were the "leaping priests" of Mars supposed to have been introduced by King Numa Pompilius. They were twelve patrician youths, dressed as archaic warriors: an embroidered tunic, a breastplate, a short red cloak , a sword, and a spiked headdress called an apex...

formed by Numa PompiliusNuma PompiliusNuma Pompilius was the legendary second king of Rome, succeeding Romulus. What tales are descended to us about him come from Valerius Antias, an author from the early part of the 1st century BC known through limited mentions of later authors , Dionysius of Halicarnassus circa 60BC-...

, approximate date 700 BC) - The Praeneste fibulaPraeneste fibulaThe Praeneste fibula is a golden brooch bearing an inscription that was accepted nearly without question since its presentation to the public in 1887 by Wolfgang Helbig, an archaeologist, as the earliest surviving specimen of the Latin language. The origin of the fibula was not stated in the...

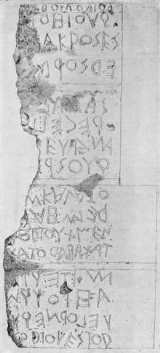

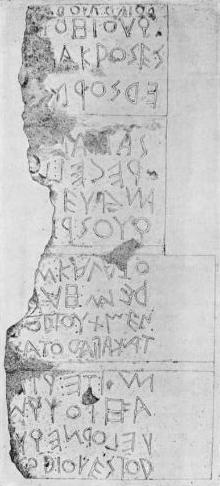

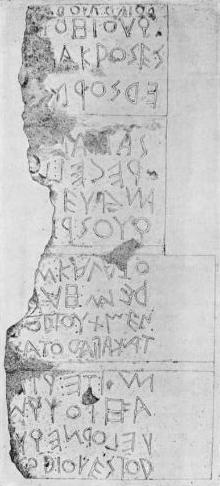

(formerly attributed to the 7th century BC, possibly a 19th century forgery) - The Forum inscription (illustration, right c. 550 BC under the monarchy)

- The Duenos inscriptionDuenos InscriptionThe Duenos Inscription is one of the earliest known Old Latin texts, dating from the 7th century BC. It is inscribed on the sides of a kernos, in this case a trio of small globular vases adjoined by three clay struts. It was found by Heinrich Dressel in 1880 on the Quirinal Hill in Rome. The kernos...

(c. 500 BC) - The Castor-Pollux dedication (c. 500 BC)

- The Garigliano BowlGarigliano BowlThe Garigliano bowl is a small impasto bowl with bucchero glaze likely to have been produced around 500 BC, with an early Latin inscript. It was found in the vicinity of ancient Minturnae ....

(c. 500 BC) - The Lapis SatricanusLapis SatricanusThe Lapis Satricanus, or, "stone of Satricum", was a yellow stone found in the ruins of the ancient Satricum, near Borgo Montello , a village of southern Lazio, dated late 6th to early 5th centuries BC. It was found in 1977 during excavations by C.M...

(early 5th century BC) - The preserved fragments of the laws of the Twelve TablesTwelve TablesThe Law of the Twelve Tables was the ancient legislation that stood at the foundation of Roman law. The Law of the Twelve Tables formed the centrepiece of the constitution of the Roman Republic and the core of the mos maiorum...

(traditionally, 449 BC449 BCYear 449 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time, it was known as the Third year of the decemviri and the Year of the Consulship of Potitus and Barbatus...

, attested much later) - The Tibur pedestal (c. 400 BC400 BCYear 400 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Tribunate of Esquilinus, Capitolinus, Vulso, Medullinus, Saccus and Vulscus...

) - The Scipionum Elogia

- Epitaph of Lucius Cornelius Scipio BarbatusLucius Cornelius Scipio BarbatusLucius Cornelius Scipio Barbatus was one of the two elected Roman consuls in 298 BC. He led the Roman army to victory against the Etruscans near Volterra...

(c. 280 BC) - Epitaph of Lucius Cornelius Scipio (consul 259 BC)Lucius Cornelius Scipio (consul 259 BC)Lucius Cornelius Scipio , consul in 259 BC during the First Punic War was a consul and censor of ancient Rome. He was the son of Lucius Cornelius Scipio Barbatus, himself consul and censor, and brother to Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio Asina, himself twice consul...

- Epitaph of Publius Cornelius Scipio P.f. P.n. AfricanusPublius Cornelius Scipio P.f. P.n. AfricanusPublius Cornelius Scipio P.f. P.n. AfricanusWith the Roman acronyms expanded, the full name is Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus Publii filius Publii nepos, translated as "Publius Cornelius Scipio son of Publius grandson of Publius." In modern times he is more popularly known as the flamen dialis...

(died about 170 BC)

- Epitaph of Lucius Cornelius Scipio Barbatus

- The Senatus consultum de BacchanalibusSenatus consultum de BacchanalibusThe senatus consultum de Bacchanalibus is a notable Old Latin inscription dating to AUC 568, or 186 BC. It was discovered in 1640 at Tiriolo, southern Italy...

(186 BC186 BCYear 186 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Albinus and Philippus...

) - The Vase Inscription from Ardea

- The Corcolle Altar fragments

- The Carmen ArvaleCarmen ArvaleThe Carmen Arvale is the preserved chant of the Arval priests or Fratres Arvales of ancient Rome.The Arval priests were devoted to the goddess Dea Dia, and offered sacrifices to her to ensure the fertility of ploughed fields . There were twelve Arval priests, chosen from patrician families. ...

- Altar to the Unknown Divinity (92 BC)

Works of literature

The authors are as follows:- Lucius Livius AndronicusLivius AndronicusLucius Livius Andronicus , not to be confused with the later historian Livy, was a Greco-Roman dramatist and epic poet of the Old Latin period. He began as an educator in the service of a noble family at Rome by translating Greek works into Latin, including Homer’s Odyssey. They were meant at...

(c. 280/260 BC — c. 200 BC), translator, founder of Roman drama - Gnaeus NaeviusGnaeus NaeviusGnaeus Naevius was a Roman epic poet and dramatist of the Old Latin period. He had a notable literary career at Rome until his satiric comments delivered in comedy angered the Metelli family, one of whom was consul. After a sojourn in prison he recanted and was set free by the tribunes...

(ca. 264 — 201 BC), dramatist, epic poet - Titus Maccius PlautusPlautusTitus Maccius Plautus , commonly known as "Plautus", was a Roman playwright of the Old Latin period. His comedies are the earliest surviving intact works in Latin literature. He wrote Palliata comoedia, the genre devised by the innovator of Latin literature, Livius Andronicus...

(c. 254 — 184 BC), dramatist, composer of comedies - Quintus EnniusEnniusQuintus Ennius was a writer during the period of the Roman Republic, and is often considered the father of Roman poetry. He was of Calabrian descent...

(239 BC — c. 169 BC), poet - Marcus PacuviusPacuviusMarcus Pacuvius was the greatest of the tragic poets of ancient Rome prior to Lucius Accius.He was the nephew and pupil of Ennius, by whom Roman tragedy was first raised to a position of influence and dignity...

(ca. 220 BC — 130 BC), tragic dramatist, poet - Statius Caecilius (220 BC — 168/166 BC), comic dramatist

- Publius Terentius AferTerencePublius Terentius Afer , better known in English as Terence, was a playwright of the Roman Republic, of North African descent. His comedies were performed for the first time around 170–160 BC. Terentius Lucanus, a Roman senator, brought Terence to Rome as a slave, educated him and later on,...

(195/185 BC — 159 BC), comic dramatist - Quintus Fabius PictorQuintus Fabius PictorQuintus Fabius Pictor was one of the earliest Roman historians and considered the first of the annalists. A member of the Fabii gens, he was the grandson of Gaius Fabius Pictor, a painter . He was a senator who fought against the Gauls in 225 BC, and against Carthage in the Second Punic War...

(3rd century BC), historian - Lucius Cincius AlimentusLucius Cincius AlimentusLucius Cincius Alimentus was a celebrated Roman annalist and jurist, who was praetor in Sicily in 209 BC, with the command of two legions. He wrote principally in Greek. He and Fabius Pictor are considered the first two Roman historians, though both wrote in Greek as a more conventionally...

(3rd century BC), military historian - Marcius Porcius CatoCato the ElderMarcus Porcius Cato was a Roman statesman, commonly referred to as Censorius , Sapiens , Priscus , or Major, Cato the Elder, or Cato the Censor, to distinguish him from his great-grandson, Cato the Younger.He came of an ancient Plebeian family who all were noted for some...

(234 BC — 149 BC), generalist, topical writer - Gaius AciliusGaius AciliusGaius Acilius was a senator and historian of ancient Rome.He knew Greek, and in 155 interpreted for Carneades, Diogenes, and Critolaus, who had come to the Roman Senate on an embassy from Athens....

(2nd century BC), historian - Lucius AcciusLucius AcciusLucius Accius , or Lucius Attius, was a Roman tragic poet and literary scholar. The son of a freedman, Accius was born at Pisaurum in Umbria, in 170 BC...

(170 BC — c. 86 BC), tragic dramatist, philologist - Gaius LuciliusGaius LuciliusGaius Lucilius , the earliest Roman satirist, of whose writings only fragments remain, was a Roman citizen of the equestrian class, born at Suessa Aurunca in Campania.-The Problem of his birthdate:...

(c. 160's BC — 103/2 BC), satirist - Quintus Lutatius CatulusQuintus Lutatius CatulusQuintus Lutatius Catulus was consul of the Roman Republic in 102 BC, and the leading public figure of the gens Lutatia of the time. His colleague in the consulship was Gaius Marius, but the two feuded and Catulus sided with Sulla in the civil war of 88–87 BC...

(2nd century BC), public officer, epigramatist - Aulus Furius AntiasAulus Furius AntiasFurius Antias was an ancient Roman poet, born in Antium.Following William Smith, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, , art. Bibaculus, his full name was Aulus Furius Antias and he was the poet A. Furius whose friendship with Quintus Lutatius Catulus, consul in 102 BC, is attested...

(2nd century BC), poet - Gaius Julius Caesar Strabo VopiscusGaius Julius Caesar Strabo VopiscusGaius Julius Caesar Strabo Vopiscus was the younger son to Lucius Julius Caesar II and his wife Poppilia and younger brother to Lucius Julius Caesar III...

(130 BC — 87 BC), public officer, tragic dramatist - Lucius PomponiusLucius PomponiusLucius Pomponius was a Roman dramatist. Called Bononiensis Lucius Pomponius (fl. ca. 90 BC or earlier) was a Roman dramatist. Called Bononiensis Lucius Pomponius (fl. ca. 90 BC or earlier) was a Roman dramatist. Called Bononiensis (“native of Bononia” (i.e. Bologna), Pomponius was a writer of...

Bononiensis (2nd century BC), comic dramatist, satirist - Lucius Cassius HeminaLucius Cassius HeminaLucius Cassius Hemina, Roman annalist, composed his annals in the period between the death of Terence and the revolution of the Gracchi.He wrote in Latin around 146 BC, including the earliest chronicle concerning the career of Mucius Scaevola....

(2nd century BC), historian - Lucius Calpurnius Piso FrugiLucius Calpurnius Piso FrugiLucius Calpurnius Piso Frugi was a Roman usurper, whose existence is questionable, as based only on the unreliable Historia Augusta....

(2nd century BC), historian - Manius ManiliusManius ManiliusManius Manilius was a Roman Republican orator and distinguished jurist who also had a long militarycareer. It is unclear if he was related to the Manius Manilius who was degraded by Cato the Censor for embracing his wife in broad daylight in Cato's censorship from 184 BC to 182 BC.Manilius was...

(2nd century BC), public officer, jurist - Lucius Coelius AntipaterLucius Coelius AntipaterLucius Coelius Antipater was a Roman jurist and historian. He is not to be confused with Coelius Sabinus, the Coelius of the Digest. He was a contemporary of C. Gracchus ; L...

(2nd century BC), jurist, historian - Publius Sempronius AsellioSempronius AsellioPublius Sempronius Asellio was an early Roman historian and one of the first writers of historiographic work in Latin. He was a military tribune of P. Scipio Aemilianus Africanus at the siege of Numantia in Hispania in 134 B.C. Later he joined the circle of writers centred around Scipio Aemilianus...

(158 BC — after 91 BC), military officer, historian - Gaius Sempronius TuditanusGaius Sempronius Tuditanus (consul 129 BC)Gaius Sempronius Tuditanus was a politician and historian of the Roman Republic. He was consul in 129 BC.- Biography :Gaius Sempronius Tuditanus was a member of the plebeian gens Sempronia. His father had the same name and was senator and in 146 BC member of a commission of ten men who had to...

(2nd century BC), jurist - Lucius AfraniusLucius Afranius (poet)Lucius Afranius was an ancient Roman comic poet, who lived at the beginning of the 1st century BC. His comedies described Roman scenes and manners and the subjects were mostly taken from the life of the lower classes...

(2nd & 1st centuries BC), comic dramatist - Titus AlbuciusTitus AlbuciusTitus Albucius, was a noted orator of the late Roman Republic.He finished his studies at Athens at the latter end of the 2nd century BC, and belonged to the Epicurean sect. He was well acquainted with Greek literature, or rather, says Cicero, was almost a Greek...

(2nd & 1st centuries BC), orator - Publius Rutilius RufusPublius Rutilius RufusPublius Rutilius Rufus was a Roman statesman, orator and historian of the Rutilius family, as well as great-uncle of Gaius Julius Caesar....

(158 BC — after 78 BC), jurist - Lucius Aelius Stilo PraeconinusLucius Aelius Stilo PraeconinusLucius Aelius Stilo Praeconinus , of Lanuvium, is the earliest philologist of the Roman Republic. He came from a distinguished family and belonged to the equestrian order....

(154 BC — 74 BC), philologist - Quintus Claudius QuadrigariusQuintus Claudius QuadrigariusQuintus Claudius Quadrigarius, Roman annalist, living probably in the 1st century BC, wrote a history, in at least twenty-three books, which began with the conquest of Rome by the Gauls and went on to the death of Sulla or perhaps later....

(2nd & 1st centuries BC), historian - Valerius AntiasValerius AntiasValerius Antias was an ancient Roman annalist whom Livy mentions as a source. No complete works of his survive but from the sixty-five fragments said to be his in the works of other authors it has been deduced that he wrote a chronicle of ancient Rome in at least seventy-five books...

(2nd & 1st centuries BC), historian - Lucius Cornelius SisennaLucius Cornelius SisennaLucius Cornelius Sisenna was a Roman soldier, historian, and annalist. He was killed in action during Pompey's campaign against pirates after the Third Mithridatic War. Sisenna had been commander of the forces on the coast of Greece....

(121 BC — 67 BC), soldier, historian - Quintus Cornificius (2nd & 1st centuries BC), rhetorician

Script

Old Latin surviving in inscriptions is written in various forms of the Etruscan alphabet as it evolved into the Latin alphabetLatin alphabet

The Latin alphabet, also called the Roman alphabet, is the most recognized alphabet used in the world today. It evolved from a western variety of the Greek alphabet called the Cumaean alphabet, which was adopted and modified by the Etruscans who ruled early Rome...

. The writing conventions varied by time and place until classical conventions prevailed. The works of authors in manuscript form were copied over into the scripts of other times. The original writing does not exist.

Orthography

Some differences between old and classical Latin were of spelling only; pronunciation is thought to be essentially as in classical Latin:- Single for double consonants: Marcelus for Marcellus

- Double vowels for long vowels: aara for āra

- q for c before u: pequnia for pecunia

- gs/ks/xs for x: e.g. regs for rex, saxsum for saxum

- c for g: Caius for Gaius

These differences did not necessarily run concurrently with each other and were not universal; that is, c was used for both c and g.

Phonology

- Preservation of original PIE thematic case endings -os and -om (later -us and -um).

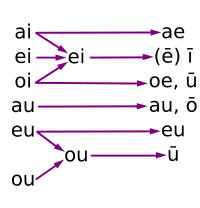

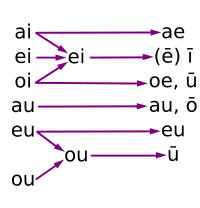

- Most original PIE diphthongs were preserved in stressed syllables, including /ai/ (later ae, but pronunciation unchanged); /ei/ (later ī); /oi/ (later ū, or sometimes oe); /ou/ (from PIE /eu/ and /ou/; later ū).

- Intervocalic /s/ preserved up through 350 BC or so, at which point it changed into /r/ (called rhotacismRhotacismRhotacism refers to several phenomena related to the usage of the consonant r :*the excessive or idiosyncratic use of the r;...

). This rhotacism had implications for declension: early classical Latin, honos, honoris (from honos, honoses); later Classical (by analogyMorphological levelingIn linguistics, morphological leveling is the generalization of an inflection across a paradigm or between words. For example, the extension of the form is to persons such as I is and they is in some dialects of English is leveling, by analogy with a more frequent form, as is the reanalysis of...

) honor, honoris ("honor"). Some Old Latin texts preserve /s/ in this position, such as the Carmen ArvaleCarmen ArvaleThe Carmen Arvale is the preserved chant of the Arval priests or Fratres Arvales of ancient Rome.The Arval priests were devoted to the goddess Dea Dia, and offered sacrifices to her to ensure the fertility of ploughed fields . There were twelve Arval priests, chosen from patrician families. ...

's lases for laresLaresLares , archaically Lases, were guardian deities in ancient Roman religion. Their origin is uncertain; they may have been guardians of the hearth, fields, boundaries or fruitfulness, hero-ancestors, or an amalgam of these....

. Later instances of /s/ are mostly due either to reduction of early /ss/ after long vowels or diphthongs; borrowings; or late reconstructions. - Many unreduced clusters, e.g. iouxmentom (later iūmentum, "beast of burden"); losna (later lūna, "moon") < *lousna < */leuksnā/; cosmis (later cōmis, "courteous"); stlocum, acc. (later locum, "place").

- /dw/ (later b): duenos (later bonus, "good"), in the famous Duenos inscriptionDuenos InscriptionThe Duenos Inscription is one of the earliest known Old Latin texts, dating from the 7th century BC. It is inscribed on the sides of a kernos, in this case a trio of small globular vases adjoined by three clay struts. It was found by Heinrich Dressel in 1880 on the Quirinal Hill in Rome. The kernos...

. - Final /d/ in ablatives (later lost) and in third-person secondary verbs (later t).

Nouns

Latin nounNoun

In linguistics, a noun is a member of a large, open lexical category whose members can occur as the main word in the subject of a clause, the object of a verb, or the object of a preposition .Lexical categories are defined in terms of how their members combine with other kinds of...

s are distinguished by grammatical case

Grammatical case

In grammar, the case of a noun or pronoun is an inflectional form that indicates its grammatical function in a phrase, clause, or sentence. For example, a pronoun may play the role of subject , of direct object , or of possessor...

, a word with a termination, or suffix, determining its use in the sentence, such as subject, predicate, etc. A case for a given word is formed by suffixing a case ending to a part of the word common to all its cases called a stem

Word stem

In linguistics, a stem is a part of a word. The term is used with slightly different meanings.In one usage, a stem is a form to which affixes can be attached. Thus, in this usage, the English word friendships contains the stem friend, to which the derivational suffix -ship is attached to form a new...

. Stems are classified by their last letters as vowel or consonant. Vowel stems are formed by adding a suffix to a shorter and more ancient segment called a root

Root (linguistics)

The root word is the primary lexical unit of a word, and of a word family , which carries the most significant aspects of semantic content and cannot be reduced into smaller constituents....

. Consonant stems are the root (roots end in consonants). The combination of the last letter of the stem and the case ending often results in an ending also called a case ending or termination. For example, the stem puella- receives a case ending -m to form the accusative case puellam in which the termination -am is evident.

In Classical Latin

Classical Latin

Classical Latin in simplest terms is the socio-linguistic register of the Latin language regarded by the enfranchised and empowered populations of the late Roman republic and the Roman empire as good Latin. Most writers during this time made use of it...

textbooks the declensions are named from the letter ending the stem or First, Second, etc. to Fifth. A declension may be illustrated by a paradigm

Paradigm

The word paradigm has been used in science to describe distinct concepts. It comes from Greek "παράδειγμα" , "pattern, example, sample" from the verb "παραδείκνυμι" , "exhibit, represent, expose" and that from "παρά" , "beside, beyond" + "δείκνυμι" , "to show, to point out".The original Greek...

, or listing of all the cases of a typical word. This method is less frequently applied to Old Latin, and with less validity. In contrast to Classical Latin, Old Latin reflects the evolution of the language from an unknown hypothetical ancestor spoken in Latium

Latium

Lazio is one of the 20 administrative regions of Italy, situated in the central peninsular section of the country. With about 5.7 million residents and a GDP of more than 170 billion euros, Lazio is the third most populated and the second richest region of Italy...

. The endings are multiple. Their use depends on time and locality. Any paradigm selected would be subject to these constraints and if applied to the language universally would result in false constructs, hypothetical words not attested in the Old Latin corpus. Nevertheless the endings are illustrated below by quasi-classical paradigms. Alternative endings from different stages of development are given, but they may not be attested for the word of the paradigm. For example, in the Second Declension, *campoe "fields" is unattested, but poploe "peoples" is attested.

First declension (a)

The 'A-Stem Declension'. The stemsWord stem

In linguistics, a stem is a part of a word. The term is used with slightly different meanings.In one usage, a stem is a form to which affixes can be attached. Thus, in this usage, the English word friendships contains the stem friend, to which the derivational suffix -ship is attached to form a new...

of noun

Noun

In linguistics, a noun is a member of a large, open lexical category whose members can occur as the main word in the subject of a clause, the object of a verb, or the object of a preposition .Lexical categories are defined in terms of how their members combine with other kinds of...

s of this declension

Declension

In linguistics, declension is the inflection of nouns, pronouns, adjectives, and articles to indicate number , case , and gender...

usually end in and are typically feminine.

A nominative case ending of –s in a few masculines indicates the nominative singular case ending may have been originally : paricidas for later paricida, but the tended to get lost. In the nominative plural, -ī replaced original -s as in the genitive singular.

| puellā, –āī girl, maiden f. |

||

|---|---|---|

| Singular Grammatical number In linguistics, grammatical number is a grammatical category of nouns, pronouns, and adjective and verb agreement that expresses count distinctions .... |

Plural | |

| Nominative | puellā | puellāī |

| Genitive | puell-ās/-āī/-ais | puell-om/-āsōm |

| Dative | puellāi | puell-eis/-abos |

| Accusative | puellam | puellās |

| Ablative | puellād | puell-eis/-abos |

| Vocative | puella | puellai |

| Locative | Romai | Syracuseis |

In the genitive singular, the was replaced with from the second declension, the resulting diphthong shortening to subsequently becoming . In a few cases the replacement did not take place: pater familiās. Explanations of the late inscriptional are speculative. In the genitive plural, the regular ending is –āsōm (classical –ārum by rhotacism

Rhotacism

Rhotacism refers to several phenomena related to the usage of the consonant r :*the excessive or idiosyncratic use of the r;...

and shortening of final o) but some nouns borrow –om (classical –um) from the second declension.

In the dative singular the final i is either long or short. The ending becomes –ae, –a (Feronia) or –e (Fortune).

In the accusative singular, Latin regularly shortens a vowel before final m.

In the ablative singular, –d was regularly lost after a long vowel. In the dative and ablative plural, the –abos descending from Indo-European *–ābhos is used for feminines only (deabus). *–ais > –eis > īs is adapted from –ois of the o-declension.

In the vocative singular, an original short a merged with the shortened a of the nominative.

The locative case would not apply to such a meaning as puella, so Roma, which is singular, and Syracusae, which is plural, have been substituted. The locative plural has already merged with the –eis form of the ablative.

Second declension (o)

The 'O-Stem Declension'. The stems of the nouns of the o-declension end in ŏ deriving from the o-grade of Indo-European ablautIndo-European ablaut

In linguistics, ablaut is a system of apophony in Proto-Indo-European and its far-reaching consequences in all of the modern Indo-European languages...

. Classical Latin evidences the development ŏ > ŭ. Nouns of this declension are either masculine or neuter.

Nominative singulars ending in -ros or -ris syncopate

Syncopation

In music, syncopation includes a variety of rhythms which are in some way unexpected in that they deviate from the strict succession of regularly spaced strong and weak but also powerful beats in a meter . These include a stress on a normally unstressed beat or a rest where one would normally be...

the -os: ager not ageros. The nominative plural masculine follows two lines of development, each leaving a trail of endings. Roman generalizes the Indo-European pronominal ending *-oi. The sequence is The "provincial texts" generalize from the Indo-European nominative plural ending *-ōs appearing in the Third Declension: *-ōs >-ēs, -eis, -īs, from 190 BC on.

| campos, –ī field, plain m. |

saxom, –ā rock, stone n. |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| Nominative | campos | camp-oe/-e/-ei/-ī /-ēs/-eis/-īs |

saxom | sax-ā/-ă |

| Genitive | camp-ī/-ei | camp-ōm/-ūm | saxī | sax-ōm/-ūm |

| Dative | campō | camp-ois/-oes/-eis/-īs | saxō | sax-ois/-oes/-eis/-īs |

| Accusative | campom | campōs | saxom | sax-ā/-ă |

| Ablative | campōd | camp-ois/-oes/-eis/-īs | saxōd | sax-ois/-oes/-eis/-īs |

| Vocative | camp-e/-us | camp-oe/-e/-ei/-ī /-ēs/-eis/-īs |

saxom | saxă |

| Locative | campī/-ei/-oi | camp-ois/-oes/-eis/-īs | saxī/-ei/-oi | sax-ois/-oes/-eis/-īs |

In the genitive singular, –ī is earliest, alternating later with –ei: populi Romanei, "of the Roman In the genitive plural, -om and -um (or -ōm and -ūm) from Indo-European *-ōm survived in classical Latin "words for coins and measures"; otherwise classical has -ōrum by analogy with 1st declension .

In the dative singular, if the Praenestine Fibula is a fraud, Numasioi, the only instance of –ōi, does not count and the Old Latin ending must be –ō.

In the vocative singular, some nouns lose the –e, (0 ending) but not necessarily the same as in classical Latin. The -e alternates regularly with -us. The vocative plural was the same as the nominative plural. Except for some singular forms that were like the genitive, the locative was captured by the ablative case in all Italic languages prior to Old Latin.

Third declension (c)

The Consonant Declension. This declension contains nouns that are masculine, feminine, and neuter. The stem ends in the root consonant, except in the special case where it ends in -i (i-stem declension). The i-stem, which is a vowel-stem, partially fused with the consonant-stem in the pre-Latin period and went further in Old Latin. I/y and u/w can be treated either as consonants or as vowels; hence their classification as semi-vowels. Mixed-stem declensions are partly like consonant-stem and partly like i-stem. Consonant-stem declensions vary slightly depending on which consonant is root-final: stop-, r-, n-, s-, etc. The paradigms below include a stop-stem (reg-) and an i-stem (igni-).| Rēgs –ēs king m. |

Ignis -ēs fire m. |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| Nominative | rēg/-s | rēg-eīs/-īs/-ēs/-ĕs | ign-is/-es | ign-eīs/-ēs/-īs/-ĕs |

| Genitive | rēg-es/-is/-os/-us | rēg-om/-um/-erum | ignis | ign-iom/-ium |

| Dative | rēg-ei/-ī/-ē/-ě | rēg-ebus/-ebūs /-ibos/-ibus |

ign-i/-eī/-ē | ign-ibus/-ibos |

| Accusative | rēgem | rēg-eīs/-īs/-ēs | ignim | ign-eīs/-ēs/-īs |

| Ablative | rēg-īd/-ĭd/-ī/-ē/-ĕ | rēg-ebus/-ebūs /-ibos/-ibus |

ign-īd/-ĭd /-ī/-ē/-ĕ |

ign-ebus/-ebūs /-ibos/-ibus |

| Vocative | rēg/-s | rēg-eīs/-īs/-ēs/-ĕs | ign-is/-es | ign-eīs/-ēs/-īs/-ĕs |

| Locative | rēgī | rēgebos | ignī | ignibos |

For the consonant declension, in the nominative singular, the -s was affixed directly to the stem consonant, but the combination of the two consonants produced modified nominatives over the Old Latin period. The case appears in different stages of modification in different words diachronically. The nominative as rēgs instead of rēx is an orthographic feature of Old Latin; the letter x was seldom used alone (as in the classical period) to designate the /ks/ or /gs/ sound, but instead, was written as either 'ks', 'cs', or even 'xs'. Often a collapse or syncope/apocope

Apocope

In phonology, apocope is the loss of one or more sounds from the end of a word, and especially the loss of an unstressed vowel.-Historical sound change:...

of the full nominative occurs: Old Latin nominus > Classical Latin nomen; hominus > homo; Caesarus > Caesar. The Latin neuter form (not shown) is the Indo-European nominative without stem ending; for example, cor < *cord "heart."

The genitive singular endings include -is < -es and -us < *-os. In the genitive plural, some forms appear to affix the case ending to the genitive singular rather than the stem:

In the dative singular, -ī succeeded -ēI and -ē after 200 BC.

In the accusative singular, -em < *-ṃ after a consonant.

In the ablative singular, the -d was lost after 200 BC. In the dative and ablative plural, the early poets sometimes used -būs.

In the locative singular, the earliest form is like the dative but over the period assimilated to the ablative.

Fourth declension (u)

The 'U-Stem' declension. The stems of the nouns of the u-declension end in ŭ and are masculine, feminine and neuter. In addition is a ū-stem declension, which contains only a few "isolated" words, such as sūs, "pig", and is not presented here.| senātus, –ūs senate m. |

||

|---|---|---|

| Singular Grammatical number In linguistics, grammatical number is a grammatical category of nouns, pronouns, and adjective and verb agreement that expresses count distinctions .... |

Plural | |

| Nominative | senātus | senātūs |

| Genitive | senāt-uos/-uis/-ī/-ous/-ūs | senāt-uom/-um |

| Dative | senātuī | senāt-ubus/-ibus |

| Accusative | senātum | senātūs |

| Ablative | senāt-ūd/-ud | senāt-ubus/-ibus |

| Vocative | senātus | senātūs |

| Locative | senāti |

Fifth declension (e)

The "E-Stem" declension functions in Old Latin much as it did in Classical Latin, with a few exceptions.While the commonest ending in the nominative in both the singular and plural forms is '-ēs' (i.e. 'rēs, rĕī'), there have been recorded a few instances of either a shortened 'e' with the addition of a consonantal 'i', as in 'reis', or the abandonment of the nature of the 'e-stem' declension (i.e. 'res, rei').

The genitive in the singular functions as the second declension: 'rĕī' (the breve above the 'e' is the result of a voiceless 'r' preceding a vowel that has no solid nature at the time of the Old Latin's use). The genitive plural, in a like manner to the second declension, is formed with an '-ēsōm', primarily.

The dative is generally formed with an unstressed '-ei' in the singular, and an '-ēbos' in the plural.

The accusative, like all the other declensions, keeps the final 'm' to shorten the inherently long vowel in the singular: 'rem', and elongates it again with a final 's' in the plural: 'rēs'.

The ablative singular is as the pronouns and the 3rd person practical: 'rēd', voiceless to keep the long 'e'. The plural is generally like the dative plural but sometimes formed with an '-rīs'.

The locative functions exactly in the singular as it does in the plural, with a short '-eis' as the 1st although there are no singular-based city names in the singular besides the occasional 'Athenseis'.

Personal pronouns

Personal pronouns are among the most common thing found in Old Latin inscriptions. In all three persons, the ablative singular ending is identical to the accusative singular.| Ego, I | Tu, You | Suī, Himself, Herself, Etc. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | ego | tu | - |

| Genitive | mis | tis | sei |

| Dative | mihei, mehei | tibei | sibei |

| Accusative | mēd | tēd | sēd |

| Ablative | mēd | tēd | sēd |

| Plural | |||

| Nominative | nōs | vōs | - |

| Genitive | nostrōm, -ōrum, -i |

vostrōm, -ōrum, -i |

sei |

| Dative | nōbeis, nis | vōbeis | sibei |

| Accusative | nōs | vōs | sēd |

| Ablative | nōbeis, nis | vōbeis | sēd |

Relative pronoun

In Old Latin, the relative pronoun is also another common concept, especially in inscriptions. The forms are quite inconsistent and leave much to be reconstructed by scholars.| queī, quaī, quod who, what | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | |

| Nominative | queī | quaī | quod |

| Genitive | quoius, quoios | quoia | quoium, quoiom |

| Dative | quoī, queī, quoieī, queī | ||

| Accusative | quem | quam | quod |

| Ablative | quī, quōd | quād | quōd |

| Plural | |||

| Nominative | ques, queis | quaī | qua |

| Genitive | quōm, quōrom | quōm, quārom | quōm, quōrom |

| Dative | queis, quīs | ||

| Accusative | quōs | quās | qua |

| Ablative | queis, quīs | ||

Old present and perfects

There is little evidence of the inflection of Old Latin verb forms and the few surviving inscriptions hold many inconsistencies between forms. Therefore, the forms below are ones that are both proven by scholars through Old Latin inscriptions, and recreated by scholars based on other early Indo-European languages such as Greek and Italic dialects such as OscanOscan language

Oscan is a term used to describe both an extinct language of southern Italy and the language group to which it belonged.The Oscan language was spoken by a number of tribes, including the Samnites, the Aurunci, the Sidicini, and the Ausones. The latter three tribes were often grouped under the name...

and Umbrian

Umbrian language

Umbrian is an extinct Italic language formerly spoken by the Umbri in the ancient Italian region of Umbria. Within the Italic languages it is closely related to the Oscan group and is therefore associated with it in the group of Osco-Umbrian languages...

.

| Indicative Present: Sum | Indicative Present: Facio | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old | Classical | Old | Classical | |||||

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| First Person | som, esom | somos, sumos | sum | sumus | fac(e/ī)o | fac(e)imos | faciō | facimus |

| Second Person | es | esteīs | es | estis | fac(e/ī)s | fac(e/ī)teis | facis | facitis |

| Third Person | est | sont | est | sunt | fac(e/ī)d/-(e/i)t | fac(e/ī)ont | facit | faciunt |

| Indicative Perfect: Sum | Indicative Perfect: Facio | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old | Classical | Old | Classical | |||||

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| First Person | fuei | fuemos | fuī | fuimus | (fe)fecei | (fe)fecemos | fēcī | fēcimus |

| Second Person | fuistei | fuisteīs | fuistī | fuistis | (fe)fecistei | (fe)fecisteis | fēcistī | fēcistis |

| Third Person | /fuit | fueront/-erom | fuit | fuērunt | (fe)feced/-et | (fe)feceront/-erom | fēcit | fēcērunt/-ēre |