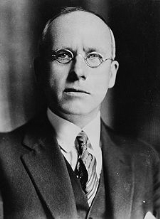

Peter Fraser

Encyclopedia

Peter Fraser was a New Zealand

political figure who served as the 24th Prime Minister

from 27 March 1940 until 13 December 1949. He assumed the office nearly seven months after the outbreak of World War II

and remained as head of government

for almost ten years. Considered by historians as a major figure in the history of New Zealand Labour Party

, he was in office longer than any other New Zealand Labour Prime Minister and is to date the fourth longest serving Prime Minister.

, Peter Fraser was born in Hill of Fearn

, a small village near the town of Tain

in the Highland

area of Easter Ross

. He received a basic education, but had to leave school due to his family's poor financial state. Though apprenticed to a carpenter

, he eventually abandoned this trade due to extremely poor eyesight – later in life, faced with difficulty reading official documents, he would insist on spoken reports rather than written ones. Before the deterioration of his vision, however, he read extensively – with socialist

activists such as Keir Hardie

and Robert Blatchford

among his favourites.

Becoming politically active in his early teens, he was 16 years old upon attaining the post of secretary of the local Liberal Association, and, eight years later, in 1908, joined the Independent Labour Party.

, Fraser decided to move to New Zealand

, having apparently chosen the country in the belief that it possessed a strong progressive spirit.

Arriving in Auckland

, he gained employment as a wharfie

and, upon joining the New Zealand Socialist Party

, became involved in union politics. When Michael Joseph Savage

who, nearly twenty-five years later, in 1935–40, was his predecessor in office as the nation's first Labour Prime Minister, stood as the Socialist candidate for Auckland Central electorate, Fraser worked as his campaign manager and also became involved in the New Zealand Federation of Labour, which he represented at Waihi

during the Waihi miners' strike

of 1912. Shortly afterwards, he moved to the country's capital, Wellington

.

In 1913, he participated in the founding of the Social Democratic Party and, during the year, within the scope of his union activities, found himself under arrest for breaches of the peace. While the arrest led to no serious repercussions, it did prompt a change of strategy – he moved away from direct action

and began to promote a parliamentary route to power.

Upon Britain's entry into World War I

, he strongly opposed New Zealand participation since, sharing the belief of many leftist thinkers, Fraser considered the conflict an "imperialist

war", fought for reasons of national interest rather than of principle.

, which absorbed much of the moribund Social Democratic Party's membership. The members selected Harry Holland

as the Labour Party's leader. Michael Joseph Savage, Fraser's old ally from the New Zealand Socialist Party, also participated.

Later in 1916, the government had Fraser and several other members of the new Labour Party arrested on charges of sedition

. This resulted from their outspoken opposition to the war, and particularly their call to abolish conscription

. Fraser received a sentence of one year in jail. He always rejected the verdict, claiming he would only have committed subversion had he taken active steps to undermine conscription, rather than merely voicing his disapproval.

After his release from prison, Fraser worked as a journalist for the official Labour Party newspaper. He also resumed his activities within the Labour Party, initially in the role of campaign manager for Harry Holland.

In a 1918 by-election, Fraser himself gained election to Parliament, winning the electorate of Wellington Central

. He soon distinguished himself through his work to counter the influenza epidemic of 1918–19

.

One year after his election to parliament Fraser married Janet Henderson Munro, also a political activist. The couple would remain together until Janet Munro's death in 1945, five years before Fraser's own passing. They had no children.

of 1917 and its Bolshevik

leaders, he rejected them soon afterwards, and eventually became one of the strongest advocates of excluding communist

s from the Labour Party. His commitment to parliamentary politics rather than to direct action became firmer, and he had a moderating influence on many Labour Party policies.

Fraser's views clashed considerably with those of Harry Holland, still serving as leader, but the party gradually shifted its policies away from the more extreme left of the spectrum. In 1933, however, Holland died, leaving the leadership vacant. Fraser contested it, but eventually lost to Michael Joseph Savage, Holland's deputy. Fraser became the new deputy leader.

While Savage represented perhaps less moderate views than Fraser, he lacked the extreme ideology of Holland. With Labour now possessing a "softer" image and the existing conservative coalition struggling with the effects of the Great Depression

, Savage's party succeeded in winning the 1935 elections

and forming a government.

, Minister of Education, Minister of Marine, and Minister of Police. He showed himself extremely active as a minister, often working seventeen hours a day, seven days a week. He had a particular interest in education, which he considered vital for social reform. His appointment of C.E. Beeby to the Education Department provided him with a valuable ally for these reforms. Fraser also became the driving force behind the 1938 Social Security Act

.

When the Second World War broke out in 1939, Fraser had already taken over most of the functions of national leadership

. Michael Joseph Savage had been ill for some time and was near death, although the authorities concealed this from the public. Fraser had to assume most of the Prime Minister's duties in addition to his own ministerial ones.

However, internal disputes within the Labour Party made Fraser's position more difficult. John A. Lee

, a notable socialist within the Party, vehemently disapproved of the party's perceived drift towards the political centre, and strongly criticised Savage and Fraser. Lee's attacks, however, became strong enough that even many of his supporters denounced them. Fraser and his allies successfully moved to expel Lee from the Party on 25 March 1940.

Savage died two days later, on 27 March, and Fraser successfully contested the leadership against Gervan McMillan

Savage died two days later, on 27 March, and Fraser successfully contested the leadership against Gervan McMillan

and Clyde Carr

. He had, however, to give the party's caucus

the right to elect people to Cabinet

without the Prime Minister's approval – a practice which has continued as a feature of the Labour Party .

, wage control

s, and conscription, proved unpopular with the party. In particular, conscription provoked strong opposition, especially since Fraser himself had opposed it during the First World War. Fraser replied that fighting in the Second World War, unlike in the First World War, had indeed a worthy cause, making conscription a necessary evil. Despite opposition from within the Labour Party, enough of the general public supported conscription to allow its acceptance.

During the war, Fraser attempted to build support for an understanding between Labour and its main rival, the National Party

. However, opposition within both parties prevented reaching an agreement, and Labour continued to govern alone. Fraser did, however, work closely with Gordon Coates

, a former Prime Minister and now a National-Party rebel - Fraser praised Coates for his willingness to set aside his party loyalty, and appears to have believed that National leader Sidney Holland

placed "party advantage before national unity".

In terms of the war effort itself, Fraser had a particular concern with ensuring that New Zealand retained control over its own forces. He believed that the more populous countries, particularly Britain

, viewed New Zealand's military as a mere extension of their own, rather than as the armed forces of a sovereign nation. After particularly serious New Zealand losses in the Greek campaign in 1941, Fraser determined to retain a say as to where to deploy New Zealand troops. Fraser insisted to British leaders that Bernard Freyberg, commander of the 2nd New Zealand Expeditionary Force, should report to the New Zealand government just as extensively as to the British authorities. When Japan

entered the war, Fraser had to choose between recalling New Zealand's forces to the Pacific (as Australia

had done) or keeping them in the Middle East

(as Winston Churchill

requested). Fraser eventually opted for the latter course.

Fraser had a very rocky relationship with U.S. Secretary of State

Fraser had a very rocky relationship with U.S. Secretary of State

Cordell Hull

, particularly over the Canberra Pact

in January 1944. Hull gave Fraser a sharp and rather demeaning dressing-down when Fraser visited Washington D.C. in mid-1944, which resulted in New Zealand's military becoming sidelined to some extent in the conduct of the Pacific War

.

After the war ended in 1945, Fraser worked with his newly-created Department of External Affairs, headed by Alister McIntosh

, and devoted much of his attention to the formation of the United Nations

. He became particularly noteworthy for his strong opposition to vesting powers of veto

in permanent members of the United Nations Security Council

, and often spoke unofficially for smaller states. Many historians consider Fraser's performance "on the world stage" show him at his best.

Fraser had a particularly close working relationship with McIntosh, who also acted as head of the Prime Minister's department during most of Fraser's premiership. McIntosh privately described his frustration with Fraser's workaholism, and with Fraser's insensitivity towards officials' needs for private lives; but the two men had a genuinely affectionate relationship.

Fraser also took up the role of Minister of Native Affairs

(which he renamed Māori Affairs) in 1947. Fraser had had an interest in Māori concerns for some time, and he implemented a number of measures designed to reduce inequality.

in its Speech from the Throne

in 1944 (two years after Australia adopted the Act), in order to gain greater constitutional independence. During the Address-In-Reply debate, the opposition passionately opposed the proposed adoption, claiming the Government was being disloyal to the United Kingdom. National MP for Tauranga

, Frederick Doidge

, argued "With us, loyalty is an instinct as deep as religion".

The proposal was buried. Ironically, the National opposition prompted the adoption of the Statute in 1947 when its leader and future Prime Minister Sidney Holland

introduced a private members' bill to abolish the New Zealand Legislative Council

. Because New Zealand required the consent of the Parliament of the United Kingdom

to amend the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852

, Fraser decided to adopt the Statute.

The adoption of the Statute of Westminster was soon followed by the debate on the future of the British Commonwealth

in its transformation into the Commonwealth of Nations. In April 1949 Éire

, formerly the Irish Free State

declared itself the Republic of Ireland

and left the Commonwealth. Fraser's government reacted by passing the Republic of Ireland Act 1949, which treated the new state as if it were still a member of the Commonwealth. Meanwhile, newly independent India

would have to leave the Commonwealth on becoming a republic also, although it was the Indian Prime Minister's view that India should remain a member of the Commonwealth as a republic. Fraser believed that the Commonwealth could as a group address the evils of colonialism and maintain the solidarity of common defence.

To Fraser the acceptance of India as a republican member would threaten the political unity of the Commonwealth. Fraser knew his domestic audience and was tough on republicanism or defence weakness to deflect criticism from the loyalist and imperialist-minded opposition National Party. Labour had been in office for fourteen years and faced an uphill battle to retain power against National at the general election, which would come just months after the high profile April 1949 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting

. In March 1949 Fraser wrote to the Canadian Prime Minister, Louis St Laurent, stating his frustration and unease over India's position. Saint Laurent had indicated that he would not be able to attend the meeting where the issue of India's republican status would dominate. Fraser argued:

Fraser left little doubt New Zealand was opposed to India's membership as a republic when he stated to his colleagues at Downing Street:

The conference quashed a proposal of a two-tier structure that would have had the traditional Commonwealth realms, perhaps with defence pacts, on one tier, and the new members which opted for a republic, on the second tier. The final compromise is perhaps best seen from the title finally accepted for The King, as Head of the Commonwealth

.

Fraser argued that the compromise allowed the Commonwealth dynamism, that would in the future allow former colonies of Africa to join as republics and be stalwarts of this New Commonwealth. It also allowed New Zealand the freedom to maintain its individual status of loyalty to the Crown and to pursue collective defence. Indeed, Fraser cabled a senior minister, Walter Nash, after the decision was taken to accept India that "while the Declaration is not as I would have wished, it is on the whole acceptable and maximum possible, and does not at any rate leave our position unimpaired".

early in his term as Prime Minister, he and Walter Nash

continued to have an active role in developing educational policy with C. E. Beeby

. In 1946

, Fraser moved to the Wellington seat of Brooklyn

, which he held until his death.

Fraser's other domestic policies, however, came under criticism. His slow speed in removing war-time rationing and his support for compulsory military training during peacetime particularly damaged him politically. With dwindling support from traditional Labour voters, and a population weary of war-time measures, Fraser's popularity declined. In the 1949 elections

the National Party defeated his government.

, but declining health prevented him from playing a significant role. He died in Wellington at the age of 66 and was buried in the city's Karori

cemetery. His successor as leader of the Labour Party was Walter Nash

.

, without a Scottish accent.

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

political figure who served as the 24th Prime Minister

Prime Minister of New Zealand

The Prime Minister of New Zealand is New Zealand's head of government consequent on being the leader of the party or coalition with majority support in the Parliament of New Zealand...

from 27 March 1940 until 13 December 1949. He assumed the office nearly seven months after the outbreak of World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

and remained as head of government

Head of government

Head of government is the chief officer of the executive branch of a government, often presiding over a cabinet. In a parliamentary system, the head of government is often styled prime minister, chief minister, premier, etc...

for almost ten years. Considered by historians as a major figure in the history of New Zealand Labour Party

New Zealand Labour Party

The New Zealand Labour Party is a New Zealand political party. It describes itself as centre-left and socially progressive and has been one of the two primary parties of New Zealand politics since 1935....

, he was in office longer than any other New Zealand Labour Prime Minister and is to date the fourth longest serving Prime Minister.

In Scotland until 1910

A native of ScotlandScotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

, Peter Fraser was born in Hill of Fearn

Hill of Fearn

Hill of Fearn is a small village near Tain in Easter Ross, in the Scottish council area of Highland.-Geography:The village is on the B9165 road, between the A9 trunk road and the smaller hamlet of Fearn to the southeast. The parish church of Fearn Abbey stands a few minutes walk to the south-east...

, a small village near the town of Tain

Tain

Tain is a royal burgh and post town in the committee area of Ross and Cromarty, in the Highland area of Scotland.-Etymology:...

in the Highland

Scottish Highlands

The Highlands is an historic region of Scotland. The area is sometimes referred to as the "Scottish Highlands". It was culturally distinguishable from the Lowlands from the later Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland Scots replaced Scottish Gaelic throughout most of the Lowlands...

area of Easter Ross

Easter Ross

Easter Ross is a loosely defined area in the east of Ross, Highland, Scotland.The name is used in the constituency name Caithness, Sutherland and Easter Ross, which is the name of both a British House of Commons constituency and a Scottish Parliament constituency...

. He received a basic education, but had to leave school due to his family's poor financial state. Though apprenticed to a carpenter

Carpentry

A carpenter is a skilled craftsperson who works with timber to construct, install and maintain buildings, furniture, and other objects. The work, known as carpentry, may involve manual labor and work outdoors....

, he eventually abandoned this trade due to extremely poor eyesight – later in life, faced with difficulty reading official documents, he would insist on spoken reports rather than written ones. Before the deterioration of his vision, however, he read extensively – with socialist

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system characterized by social ownership of the means of production and cooperative management of the economy; or a political philosophy advocating such a system. "Social ownership" may refer to any one of, or a combination of, the following: cooperative enterprises,...

activists such as Keir Hardie

Keir Hardie

James Keir Hardie, Sr. , was a Scottish socialist and labour leader, and was the first Independent Labour Member of Parliament elected to the Parliament of the United Kingdom...

and Robert Blatchford

Robert Blatchford

Robert Peel Glanville Blatchford was a socialist campaigner, journalist and author in the United Kingdom. He was a prominent atheist and opponent of eugenics. He was also an English patriot...

among his favourites.

Becoming politically active in his early teens, he was 16 years old upon attaining the post of secretary of the local Liberal Association, and, eight years later, in 1908, joined the Independent Labour Party.

Move to New Zealand

In another two years, at the age of 26, after unsuccessfully seeking employment in LondonLondon

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, Fraser decided to move to New Zealand

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

, having apparently chosen the country in the belief that it possessed a strong progressive spirit.

Arriving in Auckland

Auckland

The Auckland metropolitan area , in the North Island of New Zealand, is the largest and most populous urban area in the country with residents, percent of the country's population. Auckland also has the largest Polynesian population of any city in the world...

, he gained employment as a wharfie

Stevedore

Stevedore, dockworker, docker, dock labourer, wharfie and longshoreman can have various waterfront-related meanings concerning loading and unloading ships, according to place and country....

and, upon joining the New Zealand Socialist Party

New Zealand Socialist Party

The New Zealand Socialist Party was founded in 1901, promoting the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. The group, despite being relatively moderate when compared with many other socialists, met with little tangible success, but it nevertheless had considerable impact on the development of New...

, became involved in union politics. When Michael Joseph Savage

Michael Joseph Savage

Michael Joseph Savage was the first Labour Prime Minister of New Zealand.- Early life :Born in Tatong, Victoria, Australia, Savage first became involved in politics while working in that state. He emigrated to New Zealand in 1907. There he worked in a variety of jobs, as a miner, flax-cutter and...

who, nearly twenty-five years later, in 1935–40, was his predecessor in office as the nation's first Labour Prime Minister, stood as the Socialist candidate for Auckland Central electorate, Fraser worked as his campaign manager and also became involved in the New Zealand Federation of Labour, which he represented at Waihi

Waihi

Waihi is a town in Hauraki District in the North Island of New Zealand, especially notable for its history as a gold mine town. It had a population of 4,503 at the 2006 census....

during the Waihi miners' strike

Waihi miners' strike

The Waihi miners' strike was a major strike action in 1912 by gold miners in the New Zealand town of Waihi. It is widely regarded as the most significant industrial action in the history of New Zealand's labour movement...

of 1912. Shortly afterwards, he moved to the country's capital, Wellington

Wellington

Wellington is the capital city and third most populous urban area of New Zealand, although it is likely to have surpassed Christchurch due to the exodus following the Canterbury Earthquake. It is at the southwestern tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Rimutaka Range...

.

In 1913, he participated in the founding of the Social Democratic Party and, during the year, within the scope of his union activities, found himself under arrest for breaches of the peace. While the arrest led to no serious repercussions, it did prompt a change of strategy – he moved away from direct action

Direct action

Direct action is activity undertaken by individuals, groups, or governments to achieve political, economic, or social goals outside of normal social/political channels. This can include nonviolent and violent activities which target persons, groups, or property deemed offensive to the direct action...

and began to promote a parliamentary route to power.

Upon Britain's entry into World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, he strongly opposed New Zealand participation since, sharing the belief of many leftist thinkers, Fraser considered the conflict an "imperialist

Imperialism

Imperialism, as defined by Dictionary of Human Geography, is "the creation and/or maintenance of an unequal economic, cultural, and territorial relationships, usually between states and often in the form of an empire, based on domination and subordination." The imperialism of the last 500 years,...

war", fought for reasons of national interest rather than of principle.

Co-founder of New Zealand Labour Party

In 1916, Fraser became involved in the foundation of the New Zealand Labour PartyNew Zealand Labour Party

The New Zealand Labour Party is a New Zealand political party. It describes itself as centre-left and socially progressive and has been one of the two primary parties of New Zealand politics since 1935....

, which absorbed much of the moribund Social Democratic Party's membership. The members selected Harry Holland

Harry Holland

Henry Edmund Holland was a New Zealand politician and unionist. He was the first leader of the New Zealand Labour Party.-Early life:...

as the Labour Party's leader. Michael Joseph Savage, Fraser's old ally from the New Zealand Socialist Party, also participated.

Later in 1916, the government had Fraser and several other members of the new Labour Party arrested on charges of sedition

Sedition

In law, sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that is deemed by the legal authority to tend toward insurrection against the established order. Sedition often includes subversion of a constitution and incitement of discontent to lawful authority. Sedition may include any...

. This resulted from their outspoken opposition to the war, and particularly their call to abolish conscription

Conscription

Conscription is the compulsory enlistment of people in some sort of national service, most often military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and continues in some countries to the present day under various names...

. Fraser received a sentence of one year in jail. He always rejected the verdict, claiming he would only have committed subversion had he taken active steps to undermine conscription, rather than merely voicing his disapproval.

After his release from prison, Fraser worked as a journalist for the official Labour Party newspaper. He also resumed his activities within the Labour Party, initially in the role of campaign manager for Harry Holland.

In a 1918 by-election, Fraser himself gained election to Parliament, winning the electorate of Wellington Central

Wellington Central

rightWellington Central is a suburb of New Zealand's capital, Wellington, consisting of the flat, mostly reclaimed land, west of Lambton Harbour and the part of The Terrace immediately above it. It is bounded on the north by the suburb Pipitea and extends as far south as Civic Square...

. He soon distinguished himself through his work to counter the influenza epidemic of 1918–19

Spanish flu

The 1918 flu pandemic was an influenza pandemic, and the first of the two pandemics involving H1N1 influenza virus . It was an unusually severe and deadly pandemic that spread across the world. Historical and epidemiological data are inadequate to identify the geographic origin...

.

One year after his election to parliament Fraser married Janet Henderson Munro, also a political activist. The couple would remain together until Janet Munro's death in 1945, five years before Fraser's own passing. They had no children.

Early parliamentary career

During his early years in parliament, Fraser developed a clearer sense of his political beliefs. Although initially enthusiastic about the Russian October RevolutionOctober Revolution

The October Revolution , also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution , Red October, the October Uprising or the Bolshevik Revolution, was a political revolution and a part of the Russian Revolution of 1917...

of 1917 and its Bolshevik

Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, originally also Bolshevists , derived from bol'shinstvo, "majority") were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party which split apart from the Menshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903....

leaders, he rejected them soon afterwards, and eventually became one of the strongest advocates of excluding communist

Communism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

s from the Labour Party. His commitment to parliamentary politics rather than to direct action became firmer, and he had a moderating influence on many Labour Party policies.

Fraser's views clashed considerably with those of Harry Holland, still serving as leader, but the party gradually shifted its policies away from the more extreme left of the spectrum. In 1933, however, Holland died, leaving the leadership vacant. Fraser contested it, but eventually lost to Michael Joseph Savage, Holland's deputy. Fraser became the new deputy leader.

While Savage represented perhaps less moderate views than Fraser, he lacked the extreme ideology of Holland. With Labour now possessing a "softer" image and the existing conservative coalition struggling with the effects of the Great Depression

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

, Savage's party succeeded in winning the 1935 elections

New Zealand general election, 1935

The 1935 New Zealand general election was a nationwide vote to determine the shape of the New Zealand Parliament's 25th term. It resulted in the Labour Party's first electoral victory, with Michael Joseph Savage becoming the first Labour Prime Minister...

and forming a government.

Cabinet minister

In the new administration, Fraser became Minister of HealthNew Zealand Ministry of Health

The Ministry of Health , formerly the Department of Health from 1903 to 1993, is a department of the New Zealand government. This is the channel through which the government channels its funding for health services, VOTE: Health.The ministry is overseen by the Minister of Health in the New Zealand...

, Minister of Education, Minister of Marine, and Minister of Police. He showed himself extremely active as a minister, often working seventeen hours a day, seven days a week. He had a particular interest in education, which he considered vital for social reform. His appointment of C.E. Beeby to the Education Department provided him with a valuable ally for these reforms. Fraser also became the driving force behind the 1938 Social Security Act

Social Security Act 1938

The Social Security Act 1938 is a New Zealand Act of Parliament concerning unemployment insurance. After winning the 1935 election the newly elected First Labour government immediately issued a Christmas bonus to the unemployed...

.

When the Second World War broke out in 1939, Fraser had already taken over most of the functions of national leadership

Leadership

Leadership has been described as the “process of social influence in which one person can enlist the aid and support of others in the accomplishment of a common task". Other in-depth definitions of leadership have also emerged.-Theories:...

. Michael Joseph Savage had been ill for some time and was near death, although the authorities concealed this from the public. Fraser had to assume most of the Prime Minister's duties in addition to his own ministerial ones.

However, internal disputes within the Labour Party made Fraser's position more difficult. John A. Lee

John A. Lee

John Alfred Alexander Lee DCM was a New Zealand politician and writer. He is one of the more prominent avowed socialists in New Zealand's political history.-Early life:...

, a notable socialist within the Party, vehemently disapproved of the party's perceived drift towards the political centre, and strongly criticised Savage and Fraser. Lee's attacks, however, became strong enough that even many of his supporters denounced them. Fraser and his allies successfully moved to expel Lee from the Party on 25 March 1940.

Prime minister

Gervan McMillan

Dr. David Gervan McMillan was a New Zealand politician of the Labour Party, and a medical practitioner.He represented the Dunedin West electorate from 1935 to 1943, when he retired...

and Clyde Carr

Clyde Carr

Rev Clyde Leonard Carr was a New Zealand politician of the Labour Party, and was a minister of the Congregational Church.Ordained as a minister in 1915, he was on the Christchurch City Council between 1923 and 1927 and the Hospital Board in the 1920s, after working in commerce and banking.He...

. He had, however, to give the party's caucus

Caucus

A caucus is a meeting of supporters or members of a political party or movement, especially in the United States and Canada. As the use of the term has been expanded the exact definition has come to vary among political cultures.-Origin of the term:...

the right to elect people to Cabinet

New Zealand Cabinet

The Cabinet of New Zealand functions as the policy and decision-making body of the executive branch within the New Zealand government system...

without the Prime Minister's approval – a practice which has continued as a feature of the Labour Party .

World War II

Despite the concession, Fraser remained in command, occasionally alienating colleagues due to a governing style described by some as "authoritarian". Some of his determination to exercise control may have come about due to the war, on which Fraser focused almost exclusively. Nevertheless, certain measures he implemented, such as censorshipCensorship

thumb|[[Book burning]] following the [[1973 Chilean coup d'état|1973 coup]] that installed the [[Military government of Chile |Pinochet regime]] in Chile...

, wage control

Wage regulation

-Minimum wage:Minimum wage regulation attempts to set an hourly, or other periodic monetary standard for pay at work. A recent example was the U.K. National Minimum Wage Act 1998...

s, and conscription, proved unpopular with the party. In particular, conscription provoked strong opposition, especially since Fraser himself had opposed it during the First World War. Fraser replied that fighting in the Second World War, unlike in the First World War, had indeed a worthy cause, making conscription a necessary evil. Despite opposition from within the Labour Party, enough of the general public supported conscription to allow its acceptance.

During the war, Fraser attempted to build support for an understanding between Labour and its main rival, the National Party

New Zealand National Party

The New Zealand National Party is the largest party in the New Zealand House of Representatives and in November 2008 formed a minority government with support from three minor parties.-Policies:...

. However, opposition within both parties prevented reaching an agreement, and Labour continued to govern alone. Fraser did, however, work closely with Gordon Coates

Gordon Coates

Joseph Gordon Coates, MC and bar served as the 21st Prime Minister of New Zealand from 1925 to 1928.- Early life :Born on the Hukatere Peninsula in Kaipara Harbour where his family ran a farm, Coates took on significant responsibility at a relatively early age because his father suffered from...

, a former Prime Minister and now a National-Party rebel - Fraser praised Coates for his willingness to set aside his party loyalty, and appears to have believed that National leader Sidney Holland

Sidney Holland

Sir Sidney George Holland, GCMG, CH was the 25th Prime Minister of New Zealand from 13 December 1949 to 20 September 1957.-Early life:...

placed "party advantage before national unity".

In terms of the war effort itself, Fraser had a particular concern with ensuring that New Zealand retained control over its own forces. He believed that the more populous countries, particularly Britain

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

, viewed New Zealand's military as a mere extension of their own, rather than as the armed forces of a sovereign nation. After particularly serious New Zealand losses in the Greek campaign in 1941, Fraser determined to retain a say as to where to deploy New Zealand troops. Fraser insisted to British leaders that Bernard Freyberg, commander of the 2nd New Zealand Expeditionary Force, should report to the New Zealand government just as extensively as to the British authorities. When Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

entered the war, Fraser had to choose between recalling New Zealand's forces to the Pacific (as Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

had done) or keeping them in the Middle East

Middle East

The Middle East is a region that encompasses Western Asia and Northern Africa. It is often used as a synonym for Near East, in opposition to Far East...

(as Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

requested). Fraser eventually opted for the latter course.

Secretary of State

Secretary of State or State Secretary is a commonly used title for a senior or mid-level post in governments around the world. The role varies between countries, and in some cases there are multiple Secretaries of State in the Government....

Cordell Hull

Cordell Hull

Cordell Hull was an American politician from the U.S. state of Tennessee. He is best known as the longest-serving Secretary of State, holding the position for 11 years in the administration of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt during much of World War II...

, particularly over the Canberra Pact

Canberra Pact

The Canberra Pact was a treaty of mutual defense between the governments of Australia and New Zealand, signed on 21 January 1944. This Pact was not a military alliance; its focus was on working together on issues of mutual interest. New Zealand and Australia signed the pact so they could have a...

in January 1944. Hull gave Fraser a sharp and rather demeaning dressing-down when Fraser visited Washington D.C. in mid-1944, which resulted in New Zealand's military becoming sidelined to some extent in the conduct of the Pacific War

Pacific War

The Pacific War, also sometimes called the Asia-Pacific War refers broadly to the parts of World War II that took place in the Pacific Ocean, its islands, and in East Asia, then called the Far East...

.

After the war ended in 1945, Fraser worked with his newly-created Department of External Affairs, headed by Alister McIntosh

Alister McIntosh

Sir Alister Donald Miles McIntosh, KCMG , was a New Zealand diplomat. McIntosh was New Zealand's first secretary of foreign affairs, and is widely considered to be the father of New Zealand's independent foreign policy and architect of the ministry of Foreign Affairs in New Zealand.-Early...

, and devoted much of his attention to the formation of the United Nations

United Nations

The United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

. He became particularly noteworthy for his strong opposition to vesting powers of veto

Veto

A veto, Latin for "I forbid", is the power of an officer of the state to unilaterally stop an official action, especially enactment of a piece of legislation...

in permanent members of the United Nations Security Council

United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council is one of the principal organs of the United Nations and is charged with the maintenance of international peace and security. Its powers, outlined in the United Nations Charter, include the establishment of peacekeeping operations, the establishment of...

, and often spoke unofficially for smaller states. Many historians consider Fraser's performance "on the world stage" show him at his best.

Fraser had a particularly close working relationship with McIntosh, who also acted as head of the Prime Minister's department during most of Fraser's premiership. McIntosh privately described his frustration with Fraser's workaholism, and with Fraser's insensitivity towards officials' needs for private lives; but the two men had a genuinely affectionate relationship.

Fraser also took up the role of Minister of Native Affairs

Minister of Maori Affairs

The Minister of Māori Affairs is the minister of the New Zealand government with broad responsibility for government policy towards Māori, the first inhabitants of New Zealand. The current Minister of Māori Affairs is Dr. Pita Sharples.-Role:...

(which he renamed Māori Affairs) in 1947. Fraser had had an interest in Māori concerns for some time, and he implemented a number of measures designed to reduce inequality.

Statute of Westminster and the New Commonwealth

Fraser's Government had proposed to adopt the Statute of Westminster 1931Statute of Westminster 1931

The Statute of Westminster 1931 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Passed on 11 December 1931, the Act established legislative equality for the self-governing dominions of the British Empire with the United Kingdom...

in its Speech from the Throne

Speech from the Throne

A speech from the throne is an event in certain monarchies in which the reigning sovereign reads a prepared speech to a complete session of parliament, outlining the government's agenda for the coming session...

in 1944 (two years after Australia adopted the Act), in order to gain greater constitutional independence. During the Address-In-Reply debate, the opposition passionately opposed the proposed adoption, claiming the Government was being disloyal to the United Kingdom. National MP for Tauranga

Tauranga

Tauranga is the most populous city in the Bay of Plenty region, in the North Island of New Zealand.It was settled by Europeans in the early 19th century and was constituted as a city in 1963...

, Frederick Doidge

Frederick Doidge

Sir Frederick Widdowson Doidge, GCMG, was a journalist in New Zealand and England, then a National Party member in the New Zealand House of Representatives....

, argued "With us, loyalty is an instinct as deep as religion".

The proposal was buried. Ironically, the National opposition prompted the adoption of the Statute in 1947 when its leader and future Prime Minister Sidney Holland

Sidney Holland

Sir Sidney George Holland, GCMG, CH was the 25th Prime Minister of New Zealand from 13 December 1949 to 20 September 1957.-Early life:...

introduced a private members' bill to abolish the New Zealand Legislative Council

New Zealand Legislative Council

The Legislative Council of New Zealand was the upper house of the New Zealand Parliament from 1853 until 1951. Unlike the lower house, the New Zealand House of Representatives, the Legislative Council was appointed.-Role:...

. Because New Zealand required the consent of the Parliament of the United Kingdom

Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body in the United Kingdom, British Crown dependencies and British overseas territories, located in London...

to amend the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852

New Zealand Constitution Act 1852

The New Zealand Constitution Act 1852 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that granted self-government to the colony of New Zealand...

, Fraser decided to adopt the Statute.

The adoption of the Statute of Westminster was soon followed by the debate on the future of the British Commonwealth

Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, normally referred to as the Commonwealth and formerly known as the British Commonwealth, is an intergovernmental organisation of fifty-four independent member states...

in its transformation into the Commonwealth of Nations. In April 1949 Éire

Éire

is the Irish name for the island of Ireland and the sovereign state of the same name.- Etymology :The modern Irish Éire evolved from the Old Irish word Ériu, which was the name of a Gaelic goddess. Ériu is generally believed to have been the matron goddess of Ireland, a goddess of sovereignty, or...

, formerly the Irish Free State

Irish Free State

The Irish Free State was the state established as a Dominion on 6 December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty, signed by the British government and Irish representatives exactly twelve months beforehand...

declared itself the Republic of Ireland

Republic of Ireland

Ireland , described as the Republic of Ireland , is a sovereign state in Europe occupying approximately five-sixths of the island of the same name. Its capital is Dublin. Ireland, which had a population of 4.58 million in 2011, is a constitutional republic governed as a parliamentary democracy,...

and left the Commonwealth. Fraser's government reacted by passing the Republic of Ireland Act 1949, which treated the new state as if it were still a member of the Commonwealth. Meanwhile, newly independent India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

would have to leave the Commonwealth on becoming a republic also, although it was the Indian Prime Minister's view that India should remain a member of the Commonwealth as a republic. Fraser believed that the Commonwealth could as a group address the evils of colonialism and maintain the solidarity of common defence.

To Fraser the acceptance of India as a republican member would threaten the political unity of the Commonwealth. Fraser knew his domestic audience and was tough on republicanism or defence weakness to deflect criticism from the loyalist and imperialist-minded opposition National Party. Labour had been in office for fourteen years and faced an uphill battle to retain power against National at the general election, which would come just months after the high profile April 1949 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting

Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting

The Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting, , is a biennial summit meeting of the heads of government from all Commonwealth nations. Every two years the meeting is held in a different member state, and is chaired by that nation's respective Prime Minister or President, who becomes the...

. In March 1949 Fraser wrote to the Canadian Prime Minister, Louis St Laurent, stating his frustration and unease over India's position. Saint Laurent had indicated that he would not be able to attend the meeting where the issue of India's republican status would dominate. Fraser argued:

Fraser left little doubt New Zealand was opposed to India's membership as a republic when he stated to his colleagues at Downing Street:

The conference quashed a proposal of a two-tier structure that would have had the traditional Commonwealth realms, perhaps with defence pacts, on one tier, and the new members which opted for a republic, on the second tier. The final compromise is perhaps best seen from the title finally accepted for The King, as Head of the Commonwealth

Head of the Commonwealth

The Head of the Commonwealth heads the Commonwealth of Nations, an intergovernmental organisation which currently comprises 54 sovereign states. The position is currently occupied by the individual who serves as monarch of each of the Commonwealth realms, but has no day-to-day involvement in the...

.

Fraser argued that the compromise allowed the Commonwealth dynamism, that would in the future allow former colonies of Africa to join as republics and be stalwarts of this New Commonwealth. It also allowed New Zealand the freedom to maintain its individual status of loyalty to the Crown and to pursue collective defence. Indeed, Fraser cabled a senior minister, Walter Nash, after the decision was taken to accept India that "while the Declaration is not as I would have wished, it is on the whole acceptable and maximum possible, and does not at any rate leave our position unimpaired".

Decline and defeat

Although he relinquished the role of Minister of EducationMinister of Education (New Zealand)

The Minister of Education is a minister in the government of New Zealand with responsibility for the country's schools, and is in charge of the Ministry of Education.The present Minister is Anne Tolley, a member of the National Party.-History:...

early in his term as Prime Minister, he and Walter Nash

Walter Nash

Sir Walter Nash, GCMG, CH served as the 27th Prime Minister of New Zealand in the Second Labour Government from 1957 to 1960, and was also highly influential in his role as Minister of Finance...

continued to have an active role in developing educational policy with C. E. Beeby

C. E. Beeby

Clarence Edward Beeby ONZ CMG , most commonly referred to as C.E. Beeby or simply Beeb, was a New Zealand educationalist, "described as the architect of our modern education system"...

. In 1946

New Zealand general election, 1946

The 1946 New Zealand general election was a nationwide vote to determine the shape of the New Zealand Parliament's 28th term. It saw the governing Labour Party re-elected, but by a substantially narrower margin than in the three previous elections...

, Fraser moved to the Wellington seat of Brooklyn

Brooklyn (New Zealand electorate)

Brooklyn was a New Zealand Parliamentary electorate in Wellington city from 1946 to 1954.-Population centres:The electorate was based on the southern suburbs of Wellington city, around the hill suburb of Brooklyn.-History:...

, which he held until his death.

Fraser's other domestic policies, however, came under criticism. His slow speed in removing war-time rationing and his support for compulsory military training during peacetime particularly damaged him politically. With dwindling support from traditional Labour voters, and a population weary of war-time measures, Fraser's popularity declined. In the 1949 elections

New Zealand general election, 1949

The 1949 New Zealand general election was a nationwide vote to determine the shape of the New Zealand Parliament's 29th term. It saw the governing Labour Party defeated by the opposition National Party...

the National Party defeated his government.

Leader of the Opposition

Fraser became Leader of the OppositionLeader of the Opposition (New Zealand)

The Leader of the Opposition in New Zealand is the politician who, at least in theory, commands the support of the non-government bloc of members in the New Zealand Parliament. In the debating chamber the Leader of the Opposition sits directly opposite the Prime Minister...

, but declining health prevented him from playing a significant role. He died in Wellington at the age of 66 and was buried in the city's Karori

Karori

Karori is a suburb located at the western edge of the urban area of Wellington, New Zealand, some 4 km from the city centre.Karori is significantly larger than most other Wellington suburbs, having a population of over 14,000 at the time of the 2006 census.-History:Before the arrival of...

cemetery. His successor as leader of the Labour Party was Walter Nash

Walter Nash

Sir Walter Nash, GCMG, CH served as the 27th Prime Minister of New Zealand in the Second Labour Government from 1957 to 1960, and was also highly influential in his role as Minister of Finance...

.

In Popular Culture

Fraser was portrayed in the 2011 New Zealand TV movie, Spies and Lies. Fraser was portrayed by the New Zealand actor Peter HambletonPeter Hambleton

Peter Hambleton is a New Zealand stage, film and television actor, and stage director. Well known in the Wellington theatre scene, he has played ornithologist Walter Buller in the 2006 play Dr Buller's Birds and Charles Darwin in the 2009 play Collapsing Creation. He has been cast as the Dwarf...

, without a Scottish accent.

External links

- Prime Minister's Office biography

- http://www.michaelbassett.co.nz/article_fraser.htmFraser as Prime Minister by Michael BassettMichael BassettMichael Edward Rainton Bassett, QSO is a former Labour Party member of the New Zealand House of Representatives and cabinet minister in the reformist fourth Labour government...

]

Sources

- Bassett, Michael (2004). Tomorrow Comes the Song: A Biography of Peter Fraser. Penguin

- McGibbon, I., ed. (1993). Undiplomatic Dialogue. Auckland