Platonic Academy

Encyclopedia

The Academy was founded by Plato

in ca. 387 BC in Athens

. Aristotle

studied there for twenty years (367 BC - 347 BC) before founding his own school, the Lyceum

. The Academy persisted throughout the Hellenistic period

as a skeptical

school, until coming to an end after the death of Philo of Larissa

in 83 BC. Although philosophers continued to teach Plato's philosophy in Athens during the Roman era, it was not until AD 410 that a revived Academy was re-established as a center for Neoplatonism

, persisting until 529 AD when it was finally closed down by Justinian I

.

Before the Akademia was a school, and even before Cimon enclosed its precincts with a wall, it

Before the Akademia was a school, and even before Cimon enclosed its precincts with a wall, it

contained a sacred grove of olive trees dedicated to Athena

, the goddess of wisdom

, outside the city walls of ancient Athens

. The archaic name for the site was Hekademia (Ἑκαδήμεια), which by classical times evolved into Akademia and was explained, at least as early as the beginning of the 6th century BC, by linking it to an Athenian hero

, a legendary "Akademos

".

The site of the Academy was sacred to Athena

and other immortals; it had sheltered her religious cult since the Bronze Age

, a cult that was perhaps also associated with the hero-gods

the Dioscuri (Castor and Polydeuces), for the hero Akademos associated with the site was credited with revealing to the Divine Twins where Theseus

had hidden Helen. Out of respect for its long tradition and the association with the Dioscuri, the Sparta

ns would not ravage these original "groves of Academe" when they invaded Attica, a piety not shared by the Roman Sulla

, who axed the sacred olive trees of Athena in 86 BC to build siege engine

s.

Among the religious observations that took place at the Akademeia was a torchlit night race from altars within the city to Prometheus' altar in the Akademeia. Funeral games

Among the religious observations that took place at the Akademeia was a torchlit night race from altars within the city to Prometheus' altar in the Akademeia. Funeral games

also took place in the area as well as a Dionysiac procession from Athens to the Hekademeia and then back to the polis. The road to Akademeia was lined with the gravestones of Athenians.

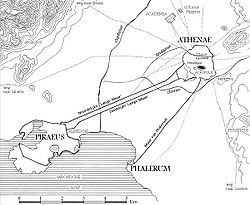

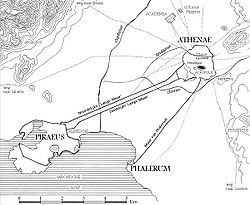

The site of the Academy was located near Colonus

. The walk from Athens to the Academy was 6 stadia

(1 mile) from the Dipylon gates (Kerameikos).

The site was rediscovered in the 20th century, in modern Akadimia Platonos

; considerable excavation has been accomplished and visiting the site is free.

gatherings which included Theaetetus of Sunium

, Archytas

of Tarentum, Leodamas of Thasos

, and Neoclides. According to Debra Nails, Speusippus

"joined the group in about 390." She claims, "It is not until Eudoxus of Cnidos

arrives in the mid-380s that Eudemus

recognizes a formal Academy." There is no historical record of the exact time the school was officially founded, but modern scholars generally agree that the time was the mid-380s, probably sometime after 387, when Plato is thought to have returned from his first visit to Italy and Sicily. Originally, the location of the meetings was Plato's property as often as it was the nearby Academy gymnasium; this remained so throughout the fourth century.

Though the Academic club was exclusive, not open to the public, it did not, during at least Plato's time, charge fees for membership. Therefore, there was probably not at that time a "school" in the sense of a clear distinction between teachers and students, or even a formal curriculum. There was, however, a distinction between senior and junior members.

In at least Plato's time, the school did not have any particular doctrine to teach; rather, Plato (and probably other associates of his) posed problems to be studied and solved by the others. There is evidence of lectures given, most notably Plato's lecture "On the Good"; but probably the use of dialectic

was more common. Above the entrance to the Academy was inscribed the phrase "Let None But Geometers Enter Here."

Many have imagined that the Academic curriculum would have closely resembled the one canvassed in Plato's Republic. Others, however, have argued that such a picture ignores the obvious peculiar arrangements of the ideal society envisioned in that dialogue. The subjects of study almost certainly included mathematics as well as the philosophical topics with which the Platonic dialogues deal, but there is little reliable evidence. There is some evidence for what today would be considered strictly scientific research: Simplicius

reports that Plato had instructed the other members to discover the simplest explanation of the observable, irregular motion of heavenly bodies: "by hypothesizing what uniform and ordered motions is it possible to save the appearances relating to planetary motions." (According to Simplicius, Plato's colleague Eudoxus was the first to have worked on this problem.)

Plato's Academy is often said to have been a school for would-be politicians in the ancient world, and to have had many illustrious alumni. In a recent survey of the evidence, Malcolm Schofield, however, has argued that it is difficult to know to what extent the Academy was interested in practical (i.e., non-theoretical) politics since much of our evidence "reflects ancient polemic for or against Plato."

Diogenes Laërtius

Diogenes Laërtius

divided the history of the Academy into three: the Old, the Middle, and the New. At the head of the Old he put Plato, at the head of the Middle Academy, Arcesilaus

, and of the New, Lacydes

. Sextus Empiricus

enumerated five divisions of the followers of Plato. He made Plato founder of the first Academy; Arcesilaus of the second; Carneades

of the third; Philo

and Charmadas

of the fourth; Antiochus

of the fifth. Cicero

recognised only two Academies, the Old and New, and made the latter commence with Arcesilaus.

" of the Academy were Speusippus

(347-339 BC), Xenocrates

(339-314 BC), Polemo

(314-269 BC), and Crates

(c. 269-266 BC). Other notable members of the Academy include Aristotle

, Heraclides

, Eudoxus

, Philip of Opus

, and Crantor

.

became scholarch. Under Arcesilaus (c. 266-241 BC), the Academy strongly emphasized Academic skepticism

. Arcesilaus was followed by Lacydes of Cyrene

(241-215 BC), Evander

and Telecles

(jointly) (205-c. 165 BC), and Hegesinus

(c. 160 BC).

, in 155 BC, the fourth scholarch in succession from Arcesilaus. It was still largely skeptical, denying the possibility of knowing an absolute truth. Carneades was followed by Clitomachus (129-c. 110 BC) and Philo of Larissa

("the last undisputed head of the Academy," c. 110-84 BC). According to Jonathan Barnes

, "It seems likely that Philo was the last Platonist geographically connected to the Academy."

Around 90 BC, Philo's student Antiochus of Ascalon

began teaching his own rival version of Platonism rejecting Skepticism and advocating Stoicism

, which began a new phase known as Middle Platonism

.

began in 88 BC, Philo of Larissa left Athens, and took refuge in Rome

, where he seems to have remained until his death. In 86 BC, Lucius Cornelius Sulla

laid siege to Athens, and conquered the city, causing much destruction. It was during the siege that he laid waste to the Academy, for "he laid hands upon the sacred groves, and ravaged the Academy, which was the most wooded of the city's suburbs, as well as the Lyceum

."

The destruction of the Academy seems to have been so severe as to make the reconstruction and re-opening of the Academy impossible. When Antiochus returned to Athens from Alexandria

, c. 84 BC, he resumed his teaching but not in the Academy. Cicero

, who studied under him in 79/8 BC, refers to Antiochus teaching in a gymnasium called Ptolemy. Cicero describes a visit to the site of the Academy one afternoon, which was "quiet and deserted at that hour of the day"

Philosophers continued to teach platonism

Philosophers continued to teach platonism

in Athens during the Roman era, but it was not until the early 5th century (c. 410) that a revived Academy was established by some leading Neoplatonists

. The origins of Neoplatonist teaching in Athens are uncertain, but when Proclus

arrived in Athens in the early 430's, he found Plutarch of Athens

and his colleague Syrianus

teaching in an Academy there. The Neoplatonists in Athens called themselves "successors" (diadochoi, but of Plato) and presented themselves as an uninterrupted tradition reaching back to Plato, but there cannot have actually been any geographical, institutional, economic or personal continuity with the original Academy. The school seems to have been a private foundation, conducted in a large house which Proclus eventually inherited from Plutarch and Syrianus. The heads of the Neoplatonic Academy were Plutarch of Athens, Syrianus, Proclus, Marinus

, Isidore

, and finally Damascius

. The Neoplatonic Academy reached its apex under Proclus (died 485).

The last "Greek" philosophers of the revived Academy in the 6th century were drawn from various parts of the Hellenistic cultural world and suggest the broad syncretism

of the common culture (see koine): Five of the seven Academy philosophers mentioned by Agathias

were Syriac in their cultural origin: Hermias and Diogenes (both from Phoenicia), Isidorus of Gaza, Damascius of Syria, Iamblichus of Coele-Syria and perhaps even Simplicius of Cilicia

.

At a date often cited as the end of Antiquity

, the emperor

Justinian

closed the school in 529 A.D. (Justinian actually closing the school has come under some recent scrutiny). The last Scholarch of the Academy was Damascius

(d. 540).

According to the sole witness, the historian Agathias

, its remaining members looked for protection under the rule of Sassanid king Khosrau I in his capital at Ctesiphon

, carrying with them precious scrolls of literature and philosophy, and to a lesser degree of science. After a peace treaty between the Persian and the Byzantine empire in 532, their personal security (an early document in the history of freedom of religion

) was guaranteed.

It has been speculated that the Academy did not altogether disappear. After his exile, Simplicius (and perhaps some others), may have travelled to Harran

, near Edessa

. From there, the students of an Academy-in-exile could have survived into the 9th century, long enough to facilitate the Arabic revival of the Neoplatonist commentary tradition in Baghdad

.

One of the earliest academies established in the east was the 7th century Academy of Gundishapur

in Sassanid Persia.

Plato

Plato , was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Along with his mentor, Socrates, and his student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the...

in ca. 387 BC in Athens

Classical Athens

The city of Athens during the classical period of Ancient Greece was a notable polis of Attica, Greece, leading the Delian League in the Peloponnesian War against Sparta and the Peloponnesian League. Athenian democracy was established in 508 BC under Cleisthenes following the tyranny of Hippias...

. Aristotle

Aristotle

Aristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology...

studied there for twenty years (367 BC - 347 BC) before founding his own school, the Lyceum

Lyceum (Classical)

The Lyceum was a gymnasium and public meeting place in Classical Athens named after the god of the grove that housed the Lyceum, Apollo Lyceus...

. The Academy persisted throughout the Hellenistic period

Hellenistic period

The Hellenistic period or Hellenistic era describes the time which followed the conquests of Alexander the Great. It was so named by the historian J. G. Droysen. During this time, Greek cultural influence and power was at its zenith in Europe and Asia...

as a skeptical

Academic skepticism

Academic skepticism refers to the skeptical period of ancient Platonism dating from around 266 BC, when Arcesilaus became head of the Platonic Academy, until around 90 BC, when Antiochus of Ascalon rejected skepticism. Like their fellow Pyrrhonists, they maintained that knowledge of things is...

school, until coming to an end after the death of Philo of Larissa

Philo of Larissa

Philo of Larissa, was a Greek philosopher. He was a pupil of Clitomachus, whom he succeeded as head of the Academy. During the Mithradatic wars which would see the destruction of the Academy, he travelled to Rome where Cicero heard him lecture. None of his writings survive...

in 83 BC. Although philosophers continued to teach Plato's philosophy in Athens during the Roman era, it was not until AD 410 that a revived Academy was re-established as a center for Neoplatonism

Neoplatonism

Neoplatonism , is the modern term for a school of religious and mystical philosophy that took shape in the 3rd century AD, based on the teachings of Plato and earlier Platonists, with its earliest contributor believed to be Plotinus, and his teacher Ammonius Saccas...

, persisting until 529 AD when it was finally closed down by Justinian I

Justinian I

Justinian I ; , ; 483– 13 or 14 November 565), commonly known as Justinian the Great, was Byzantine Emperor from 527 to 565. During his reign, Justinian sought to revive the Empire's greatness and reconquer the lost western half of the classical Roman Empire.One of the most important figures of...

.

Site

contained a sacred grove of olive trees dedicated to Athena

Athena

In Greek mythology, Athena, Athenê, or Athene , also referred to as Pallas Athena/Athene , is the goddess of wisdom, courage, inspiration, civilization, warfare, strength, strategy, the arts, crafts, justice, and skill. Minerva, Athena's Roman incarnation, embodies similar attributes. Athena is...

, the goddess of wisdom

Wisdom

Wisdom is a deep understanding and realization of people, things, events or situations, resulting in the ability to apply perceptions, judgements and actions in keeping with this understanding. It often requires control of one's emotional reactions so that universal principles, reason and...

, outside the city walls of ancient Athens

Athens

Athens , is the capital and largest city of Greece. Athens dominates the Attica region and is one of the world's oldest cities, as its recorded history spans around 3,400 years. Classical Athens was a powerful city-state...

. The archaic name for the site was Hekademia (Ἑκαδήμεια), which by classical times evolved into Akademia and was explained, at least as early as the beginning of the 6th century BC, by linking it to an Athenian hero

Greek hero cult

Hero cults were one of the most distinctive features of ancient Greek religion. In Homeric Greek, "hero" refers to a man who was fighting on either side during the Trojan War...

, a legendary "Akademos

Akademos

Akademos was an Attic hero in Greek mythology. The tale traditionally told of him is that when Castor and Polydeuces invaded Attica to liberate their sister Helen, he betrayed to them that she was kept concealed at Aphidnae...

".

The site of the Academy was sacred to Athena

Athena

In Greek mythology, Athena, Athenê, or Athene , also referred to as Pallas Athena/Athene , is the goddess of wisdom, courage, inspiration, civilization, warfare, strength, strategy, the arts, crafts, justice, and skill. Minerva, Athena's Roman incarnation, embodies similar attributes. Athena is...

and other immortals; it had sheltered her religious cult since the Bronze Age

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a period characterized by the use of copper and its alloy bronze as the chief hard materials in the manufacture of some implements and weapons. Chronologically, it stands between the Stone Age and Iron Age...

, a cult that was perhaps also associated with the hero-gods

Greek hero cult

Hero cults were one of the most distinctive features of ancient Greek religion. In Homeric Greek, "hero" refers to a man who was fighting on either side during the Trojan War...

the Dioscuri (Castor and Polydeuces), for the hero Akademos associated with the site was credited with revealing to the Divine Twins where Theseus

Theseus

For other uses, see Theseus Theseus was the mythical founder-king of Athens, son of Aethra, and fathered by Aegeus and Poseidon, both of whom Aethra had slept with in one night. Theseus was a founder-hero, like Perseus, Cadmus, or Heracles, all of whom battled and overcame foes that were...

had hidden Helen. Out of respect for its long tradition and the association with the Dioscuri, the Sparta

Sparta

Sparta or Lacedaemon, was a prominent city-state in ancient Greece, situated on the banks of the River Eurotas in Laconia, in south-eastern Peloponnese. It emerged as a political entity around the 10th century BC, when the invading Dorians subjugated the local, non-Dorian population. From c...

ns would not ravage these original "groves of Academe" when they invaded Attica, a piety not shared by the Roman Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix , known commonly as Sulla, was a Roman general and statesman. He had the rare distinction of holding the office of consul twice, as well as that of dictator...

, who axed the sacred olive trees of Athena in 86 BC to build siege engine

Siege engine

A siege engine is a device that is designed to break or circumvent city walls and other fortifications in siege warfare. Some have been operated close to the fortifications, while others have been used to attack from a distance. From antiquity, siege engines were constructed largely of wood and...

s.

Funeral Games

Funeral Games is a 1981 historical novel by Mary Renault, dealing with the death of Alexander the Great and its aftermath, the gradual disintegration of his empire...

also took place in the area as well as a Dionysiac procession from Athens to the Hekademeia and then back to the polis. The road to Akademeia was lined with the gravestones of Athenians.

The site of the Academy was located near Colonus

Colonus

In classical Greece Hippeios Colonus was a deme about to the northwest of Athens, near Plato's Academy. There is also the Agoraios Kolonos , a hillock by the Athens Agora on which the temple of Hephaestus still stands.Hippeios Colonus held a temple of Poseidon and a sacred grove to the...

. The walk from Athens to the Academy was 6 stadia

Stadia

Stadium or stadion has the plural stadia in both Latin and Greek. The anglicized term is stade in the singular.Stadium may refer to:* Stadium, a building type...

(1 mile) from the Dipylon gates (Kerameikos).

The site was rediscovered in the 20th century, in modern Akadimia Platonos

Akadimia Platonos

Akademia Platonos is a subdivision located 3 km west-northwest of the downtown part of the Greek capital of Athens. The area is named after the Plato's Academy. The area are is densely populated, with people mainly living in eight to ten storey buildings...

; considerable excavation has been accomplished and visiting the site is free.

Plato's Academy

What was later to be known as Plato's school probably originated around the time Plato acquired inherited property at the age of thirty, with informalgatherings which included Theaetetus of Sunium

Theaetetus (mathematician)

Theaetetus, Theaitētos, of Athens, possibly son of Euphronius, of the Athenian deme Sunium, was a classical Greek mathematician...

, Archytas

Archytas

Archytas was an Ancient Greek philosopher, mathematician, astronomer, statesman, and strategist. He was a scientist of the Pythagorean school and famous for being the reputed founder of mathematical mechanics, as well as a good friend of Plato....

of Tarentum, Leodamas of Thasos

Leodamas of Thasos

Leodamas of Thasos was a Greek mathematician and a contemporary of Plato, about whom little is known.There are two references to Leodamas in Proclus's Commentary on Euclid:...

, and Neoclides. According to Debra Nails, Speusippus

Speusippus

Speusippus was an ancient Greek philosopher. Speusippus was Plato's nephew by his sister Potone. After Plato's death, Speusippus inherited the Academy and remained its head for the next eight years. However, following a stroke, he passed the chair to Xenocrates. Although the successor to Plato...

"joined the group in about 390." She claims, "It is not until Eudoxus of Cnidos

Eudoxus of Cnidus

Eudoxus of Cnidus was a Greek astronomer, mathematician, scholar and student of Plato. Since all his own works are lost, our knowledge of him is obtained from secondary sources, such as Aratus's poem on astronomy...

arrives in the mid-380s that Eudemus

Eudemus of Rhodes

Eudemus of Rhodes was an ancient Greek philosopher, and first historian of science who lived from ca. 370 BC until ca. 300 BC. He was one of Aristotle's most important pupils, editing his teacher's work and making it more easily accessible...

recognizes a formal Academy." There is no historical record of the exact time the school was officially founded, but modern scholars generally agree that the time was the mid-380s, probably sometime after 387, when Plato is thought to have returned from his first visit to Italy and Sicily. Originally, the location of the meetings was Plato's property as often as it was the nearby Academy gymnasium; this remained so throughout the fourth century.

Though the Academic club was exclusive, not open to the public, it did not, during at least Plato's time, charge fees for membership. Therefore, there was probably not at that time a "school" in the sense of a clear distinction between teachers and students, or even a formal curriculum. There was, however, a distinction between senior and junior members.

In at least Plato's time, the school did not have any particular doctrine to teach; rather, Plato (and probably other associates of his) posed problems to be studied and solved by the others. There is evidence of lectures given, most notably Plato's lecture "On the Good"; but probably the use of dialectic

Dialectic

Dialectic is a method of argument for resolving disagreement that has been central to Indic and European philosophy since antiquity. The word dialectic originated in Ancient Greece, and was made popular by Plato in the Socratic dialogues...

was more common. Above the entrance to the Academy was inscribed the phrase "Let None But Geometers Enter Here."

Many have imagined that the Academic curriculum would have closely resembled the one canvassed in Plato's Republic. Others, however, have argued that such a picture ignores the obvious peculiar arrangements of the ideal society envisioned in that dialogue. The subjects of study almost certainly included mathematics as well as the philosophical topics with which the Platonic dialogues deal, but there is little reliable evidence. There is some evidence for what today would be considered strictly scientific research: Simplicius

Simplicius of Cilicia

Simplicius of Cilicia, was a disciple of Ammonius Hermiae and Damascius, and was one of the last of the Neoplatonists. He was among the pagan philosophers persecuted by Justinian in the early 6th century, and was forced for a time to seek refuge in the Persian court, before being allowed back into...

reports that Plato had instructed the other members to discover the simplest explanation of the observable, irregular motion of heavenly bodies: "by hypothesizing what uniform and ordered motions is it possible to save the appearances relating to planetary motions." (According to Simplicius, Plato's colleague Eudoxus was the first to have worked on this problem.)

Plato's Academy is often said to have been a school for would-be politicians in the ancient world, and to have had many illustrious alumni. In a recent survey of the evidence, Malcolm Schofield, however, has argued that it is difficult to know to what extent the Academy was interested in practical (i.e., non-theoretical) politics since much of our evidence "reflects ancient polemic for or against Plato."

Later history of the Academy

Diogenes Laertius

Diogenes Laertius was a biographer of the Greek philosophers. Nothing is known about his life, but his surviving Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers is one of the principal surviving sources for the history of Greek philosophy.-Life:Nothing is definitively known about his life...

divided the history of the Academy into three: the Old, the Middle, and the New. At the head of the Old he put Plato, at the head of the Middle Academy, Arcesilaus

Arcesilaus

Arcesilaus was a Greek philosopher and founder of the Second or Middle Academy—the phase of Academic skepticism. Arcesilaus succeeded Crates as the sixth head of the Academy c. 264 BC. He did not preserve his thoughts in writing, so his opinions can only be gleaned second-hand from what is...

, and of the New, Lacydes

Lacydes of Cyrene

Lacydes of Cyrene, Greek philosopher, was head of the Academy at Athens in succession to Arcesilaus from 241 BC. He was forced to resign c. 215 BC due to ill-health, and he died c. 205 BC. Nothing survives of his works.-Life:...

. Sextus Empiricus

Sextus Empiricus

Sextus Empiricus , was a physician and philosopher, and has been variously reported to have lived in Alexandria, Rome, or Athens. His philosophical work is the most complete surviving account of ancient Greek and Roman skepticism....

enumerated five divisions of the followers of Plato. He made Plato founder of the first Academy; Arcesilaus of the second; Carneades

Carneades

Carneades was an Academic skeptic born in Cyrene. By the year 159 BC, he had started to refute all previous dogmatic doctrines, especially Stoicism, and even the Epicureans whom previous skeptics had spared. As head of the Academy, he was one of three philosophers sent to Rome in 155 BC where his...

of the third; Philo

Philo of Larissa

Philo of Larissa, was a Greek philosopher. He was a pupil of Clitomachus, whom he succeeded as head of the Academy. During the Mithradatic wars which would see the destruction of the Academy, he travelled to Rome where Cicero heard him lecture. None of his writings survive...

and Charmadas

Charmadas

Charmadas, was an Academic philosopher and a disciple of Clitomachus at the Academy in Athens. He was a friend and companion of Philo of Larissa. He was teaching in Athens by 110 BC, and was clearly an important philosopher. He was still alive in 103 BC, but was dead by 91 BC...

of the fourth; Antiochus

Antiochus of Ascalon

Antiochus , of Ascalon, , was an Academic philosopher. He was a pupil of Philo of Larissa at the Academy, but he diverged from the Academic skepticism of Philo and his predecessors...

of the fifth. Cicero

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero , was a Roman philosopher, statesman, lawyer, political theorist, and Roman constitutionalist. He came from a wealthy municipal family of the equestrian order, and is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.He introduced the Romans to the chief...

recognised only two Academies, the Old and New, and made the latter commence with Arcesilaus.

Old Academy

Plato's immediate successors as "scholarchScholarch

A scholarch is the head of a school. The term was especially used for the heads of schools of philosophy in ancient Athens, such as the Platonic Academy, whose first scholarch was Plato himself...

" of the Academy were Speusippus

Speusippus

Speusippus was an ancient Greek philosopher. Speusippus was Plato's nephew by his sister Potone. After Plato's death, Speusippus inherited the Academy and remained its head for the next eight years. However, following a stroke, he passed the chair to Xenocrates. Although the successor to Plato...

(347-339 BC), Xenocrates

Xenocrates

Xenocrates of Chalcedon was a Greek philosopher, mathematician, and leader of the Platonic Academy from 339/8 to 314/3 BC. His teachings followed those of Plato, which he attempted to define more closely, often with mathematical elements...

(339-314 BC), Polemo

Polemon (scholarch)

Polemon of Athens was an eminent Platonist philosopher and Plato's third successor as scholarch or head of the Academy from 314/313 to 270/269 BC...

(314-269 BC), and Crates

Crates of Athens

Crates of Athens was the son of Antigenes of the Thriasian deme, the pupil and eromenos of Polemo, and his successor as scholarch of the Platonic Academy, in 270/69 BC...

(c. 269-266 BC). Other notable members of the Academy include Aristotle

Aristotle

Aristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology...

, Heraclides

Heraclides Ponticus

Heraclides Ponticus , also known as Herakleides and Heraklides of Pontus, was a Greek philosopher and astronomer who lived and died at Heraclea Pontica, now Karadeniz Ereğli, Turkey. He is best remembered for proposing that the earth rotates on its axis, from west to east, once every 24 hours...

, Eudoxus

Eudoxus of Cnidus

Eudoxus of Cnidus was a Greek astronomer, mathematician, scholar and student of Plato. Since all his own works are lost, our knowledge of him is obtained from secondary sources, such as Aratus's poem on astronomy...

, Philip of Opus

Philip of Opus

Philip of Opus, Greece, was a philosopher and a member of the Academy during Plato's lifetime. Philip was the editor of Plato's Laws...

, and Crantor

Crantor

Crantor was a Greek philosopher of the Old Academy, probably born around the middle of the 4th century BC, at Soli in Cilicia.-Life:Crantor moved to Athens in order to study philosophy, where he became a pupil of Xenocrates and a friend of Polemo, and one of the most distinguished supporters of...

.

Middle Academy

Around 266 BC ArcesilausArcesilaus

Arcesilaus was a Greek philosopher and founder of the Second or Middle Academy—the phase of Academic skepticism. Arcesilaus succeeded Crates as the sixth head of the Academy c. 264 BC. He did not preserve his thoughts in writing, so his opinions can only be gleaned second-hand from what is...

became scholarch. Under Arcesilaus (c. 266-241 BC), the Academy strongly emphasized Academic skepticism

Academic skepticism

Academic skepticism refers to the skeptical period of ancient Platonism dating from around 266 BC, when Arcesilaus became head of the Platonic Academy, until around 90 BC, when Antiochus of Ascalon rejected skepticism. Like their fellow Pyrrhonists, they maintained that knowledge of things is...

. Arcesilaus was followed by Lacydes of Cyrene

Lacydes of Cyrene

Lacydes of Cyrene, Greek philosopher, was head of the Academy at Athens in succession to Arcesilaus from 241 BC. He was forced to resign c. 215 BC due to ill-health, and he died c. 205 BC. Nothing survives of his works.-Life:...

(241-215 BC), Evander

Evander (philosopher)

Evander , born in Phocis or Phocaea, was the pupil and successor of Lacydes, and was joint leader of the Academy at Athens together with Telecles....

and Telecles

Telecles

Telecles , of Phocis or Phocaea, was the pupil and successor of Lacydes, and was joint leader of the Academy at Athens together with Evander....

(jointly) (205-c. 165 BC), and Hegesinus

Hegesinus of Pergamon

Hegesinus , of Pergamon, an Academic philosopher, the successor of Evander and the immediate predecessor of Carneades as the leader of the Academy. He was scholarch for a period around 160 BC. Nothing else is known about him.-References:...

(c. 160 BC).

New Academy

The New or Third Academy begins with CarneadesCarneades

Carneades was an Academic skeptic born in Cyrene. By the year 159 BC, he had started to refute all previous dogmatic doctrines, especially Stoicism, and even the Epicureans whom previous skeptics had spared. As head of the Academy, he was one of three philosophers sent to Rome in 155 BC where his...

, in 155 BC, the fourth scholarch in succession from Arcesilaus. It was still largely skeptical, denying the possibility of knowing an absolute truth. Carneades was followed by Clitomachus (129-c. 110 BC) and Philo of Larissa

Philo of Larissa

Philo of Larissa, was a Greek philosopher. He was a pupil of Clitomachus, whom he succeeded as head of the Academy. During the Mithradatic wars which would see the destruction of the Academy, he travelled to Rome where Cicero heard him lecture. None of his writings survive...

("the last undisputed head of the Academy," c. 110-84 BC). According to Jonathan Barnes

Jonathan Barnes

Jonathan Barnes is a British philosopher, translator and historian of ancient philosophy.-Education and career:He was educated at the City of London School and Balliol College, Oxford University....

, "It seems likely that Philo was the last Platonist geographically connected to the Academy."

Around 90 BC, Philo's student Antiochus of Ascalon

Antiochus of Ascalon

Antiochus , of Ascalon, , was an Academic philosopher. He was a pupil of Philo of Larissa at the Academy, but he diverged from the Academic skepticism of Philo and his predecessors...

began teaching his own rival version of Platonism rejecting Skepticism and advocating Stoicism

Stoicism

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy founded in Athens by Zeno of Citium in the early . The Stoics taught that destructive emotions resulted from errors in judgment, and that a sage, or person of "moral and intellectual perfection," would not suffer such emotions.Stoics were concerned...

, which began a new phase known as Middle Platonism

Middle Platonism

Middle Platonism is the modern name given to a stage in the development of Plato's philosophy, lasting from about 90 BC, when Antiochus of Ascalon rejected the scepticism of the New Academy, until the development of Neoplatonism under Plotinus in the 3rd century. Middle Platonism absorbed many...

.

The Destruction of the Academy

When the First Mithridatic WarFirst Mithridatic War

The First Mithridatic War was a war challenging Rome's expanding Empire and rule over the Greek world. In this conflict, the Kingdom of Pontus and many Greek cities rebelling against Rome were led by Mithridates VI of Pontus against the Roman Republic and the Kingdom of Bithynia...

began in 88 BC, Philo of Larissa left Athens, and took refuge in Rome

Rome

Rome is the capital of Italy and the country's largest and most populated city and comune, with over 2.7 million residents in . The city is located in the central-western portion of the Italian Peninsula, on the Tiber River within the Lazio region of Italy.Rome's history spans two and a half...

, where he seems to have remained until his death. In 86 BC, Lucius Cornelius Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix , known commonly as Sulla, was a Roman general and statesman. He had the rare distinction of holding the office of consul twice, as well as that of dictator...

laid siege to Athens, and conquered the city, causing much destruction. It was during the siege that he laid waste to the Academy, for "he laid hands upon the sacred groves, and ravaged the Academy, which was the most wooded of the city's suburbs, as well as the Lyceum

Lyceum

The lyceum is a category of educational institution defined within the education system of many countries, mainly in Europe. The definition varies between countries; usually it is a type of secondary school.-History:...

."

The destruction of the Academy seems to have been so severe as to make the reconstruction and re-opening of the Academy impossible. When Antiochus returned to Athens from Alexandria

Alexandria

Alexandria is the second-largest city of Egypt, with a population of 4.1 million, extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea in the north central part of the country; it is also the largest city lying directly on the Mediterranean coast. It is Egypt's largest seaport, serving...

, c. 84 BC, he resumed his teaching but not in the Academy. Cicero

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero , was a Roman philosopher, statesman, lawyer, political theorist, and Roman constitutionalist. He came from a wealthy municipal family of the equestrian order, and is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.He introduced the Romans to the chief...

, who studied under him in 79/8 BC, refers to Antiochus teaching in a gymnasium called Ptolemy. Cicero describes a visit to the site of the Academy one afternoon, which was "quiet and deserted at that hour of the day"

Neoplatonic Academy

Middle Platonism

Middle Platonism is the modern name given to a stage in the development of Plato's philosophy, lasting from about 90 BC, when Antiochus of Ascalon rejected the scepticism of the New Academy, until the development of Neoplatonism under Plotinus in the 3rd century. Middle Platonism absorbed many...

in Athens during the Roman era, but it was not until the early 5th century (c. 410) that a revived Academy was established by some leading Neoplatonists

Neoplatonism

Neoplatonism , is the modern term for a school of religious and mystical philosophy that took shape in the 3rd century AD, based on the teachings of Plato and earlier Platonists, with its earliest contributor believed to be Plotinus, and his teacher Ammonius Saccas...

. The origins of Neoplatonist teaching in Athens are uncertain, but when Proclus

Proclus

Proclus Lycaeus , called "The Successor" or "Diadochos" , was a Greek Neoplatonist philosopher, one of the last major Classical philosophers . He set forth one of the most elaborate and fully developed systems of Neoplatonism...

arrived in Athens in the early 430's, he found Plutarch of Athens

Plutarch of Athens

Plutarch of Athens was a Greek philosopher and Neoplatonist who taught at Athens at the beginning of the 5th century. He reestablished the Platonic Academy there and became its leader...

and his colleague Syrianus

Syrianus

Syrianus ; died c. 437) was a Greek Neoplatonist philosopher, and head of Plato's Academy in Athens, succeeding his teacher Plutarch of Athens in 431/432. He is important as the teacher of Proclus, and, like Plutarch and Proclus, as a commentator on Plato and Aristotle. His best-known extant work...

teaching in an Academy there. The Neoplatonists in Athens called themselves "successors" (diadochoi, but of Plato) and presented themselves as an uninterrupted tradition reaching back to Plato, but there cannot have actually been any geographical, institutional, economic or personal continuity with the original Academy. The school seems to have been a private foundation, conducted in a large house which Proclus eventually inherited from Plutarch and Syrianus. The heads of the Neoplatonic Academy were Plutarch of Athens, Syrianus, Proclus, Marinus

Marinus of Neapolis

Marinus was a Neoplatonist philosopher born in Flavia Neapolis , Palestine in around 450 AD. He was probably a Samaritan, or possibly a Jew....

, Isidore

Isidore of Alexandria

Isidore of Alexandria was an Egyptian or Greek philosopher and one of the last of the Neoplatonists. He lived in Athens and Alexandria toward the end of the 5th century AD. He became head of the school in Athens in succession to Marinus, who followed Proclus.-Life:Isidore was born in Alexandria...

, and finally Damascius

Damascius

Damascius , known as "the last of the Neoplatonists," was the last scholarch of the School of Athens. He was one of the pagan philosophers persecuted by Justinian in the early 6th century, and was forced for a time to seek refuge in the Persian court, before being allowed back into the empire...

. The Neoplatonic Academy reached its apex under Proclus (died 485).

The last "Greek" philosophers of the revived Academy in the 6th century were drawn from various parts of the Hellenistic cultural world and suggest the broad syncretism

Syncretism

Syncretism is the combining of different beliefs, often while melding practices of various schools of thought. The term means "combining", but see below for the origin of the word...

of the common culture (see koine): Five of the seven Academy philosophers mentioned by Agathias

Agathias

Agathias or Agathias Scholasticus , of Myrina , an Aeolian city in western Asia Minor , was a Greek poet and the principal historian of part of the reign of the Roman emperor Justinian I between 552 and 558....

were Syriac in their cultural origin: Hermias and Diogenes (both from Phoenicia), Isidorus of Gaza, Damascius of Syria, Iamblichus of Coele-Syria and perhaps even Simplicius of Cilicia

Simplicius of Cilicia

Simplicius of Cilicia, was a disciple of Ammonius Hermiae and Damascius, and was one of the last of the Neoplatonists. He was among the pagan philosophers persecuted by Justinian in the early 6th century, and was forced for a time to seek refuge in the Persian court, before being allowed back into...

.

At a date often cited as the end of Antiquity

Classical antiquity

Classical antiquity is a broad term for a long period of cultural history centered on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ancient Greece and ancient Rome, collectively known as the Greco-Roman world...

, the emperor

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire was the Eastern Roman Empire during the periods of Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, centred on the capital of Constantinople. Known simply as the Roman Empire or Romania to its inhabitants and neighbours, the Empire was the direct continuation of the Ancient Roman State...

Justinian

Justinian I

Justinian I ; , ; 483– 13 or 14 November 565), commonly known as Justinian the Great, was Byzantine Emperor from 527 to 565. During his reign, Justinian sought to revive the Empire's greatness and reconquer the lost western half of the classical Roman Empire.One of the most important figures of...

closed the school in 529 A.D. (Justinian actually closing the school has come under some recent scrutiny). The last Scholarch of the Academy was Damascius

Damascius

Damascius , known as "the last of the Neoplatonists," was the last scholarch of the School of Athens. He was one of the pagan philosophers persecuted by Justinian in the early 6th century, and was forced for a time to seek refuge in the Persian court, before being allowed back into the empire...

(d. 540).

According to the sole witness, the historian Agathias

Agathias

Agathias or Agathias Scholasticus , of Myrina , an Aeolian city in western Asia Minor , was a Greek poet and the principal historian of part of the reign of the Roman emperor Justinian I between 552 and 558....

, its remaining members looked for protection under the rule of Sassanid king Khosrau I in his capital at Ctesiphon

Ctesiphon

Ctesiphon, the imperial capital of the Parthian Arsacids and of the Persian Sassanids, was one of the great cities of ancient Mesopotamia.The ruins of the city are located on the east bank of the Tigris, across the river from the Hellenistic city of Seleucia...

, carrying with them precious scrolls of literature and philosophy, and to a lesser degree of science. After a peace treaty between the Persian and the Byzantine empire in 532, their personal security (an early document in the history of freedom of religion

Freedom of religion

Freedom of religion is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance; the concept is generally recognized also to include the freedom to change religion or not to follow any...

) was guaranteed.

It has been speculated that the Academy did not altogether disappear. After his exile, Simplicius (and perhaps some others), may have travelled to Harran

Harran

Harran was a major ancient city in Upper Mesopotamia whose site is near the modern village of Altınbaşak, Turkey, 24 miles southeast of Şanlıurfa...

, near Edessa

Edessa, Mesopotamia

Edessa is the Greek name of an Aramaic town in northern Mesopotamia, as refounded by Seleucus I Nicator. For the modern history of the city, see Şanlıurfa.-Names:...

. From there, the students of an Academy-in-exile could have survived into the 9th century, long enough to facilitate the Arabic revival of the Neoplatonist commentary tradition in Baghdad

Baghdad

Baghdad is the capital of Iraq, as well as the coterminous Baghdad Governorate. The population of Baghdad in 2011 is approximately 7,216,040...

.

One of the earliest academies established in the east was the 7th century Academy of Gundishapur

Academy of Gundishapur

The Academy of Gondishapur , also Jondishapur , was a renowned academy of learning in the city of Gundeshapur during late antiquity, the intellectual center of the Sassanid empire. It offered training in medicine, philosophy, theology and science. The faculty were versed in the Zoroastrian and...

in Sassanid Persia.

See also

- Academy of Athens (modern)Academy of Athens (modern)The Academy of Athens is Greece's national academy, and the highest research establishment in the country. It was established in 1926, and operates under the supervision of the Ministry of Education...

- Hellenistic philosophyHellenistic philosophyHellenistic philosophy is the period of Western philosophy that was developed in the Hellenistic civilization following Aristotle and ending with the beginning of Neoplatonism.-Pythagoreanism:...

- PlatonismPlatonismPlatonism is the philosophy of Plato or the name of other philosophical systems considered closely derived from it. In a narrower sense the term might indicate the doctrine of Platonic realism...

- Peripatetic school

- StoicismStoicismStoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy founded in Athens by Zeno of Citium in the early . The Stoics taught that destructive emotions resulted from errors in judgment, and that a sage, or person of "moral and intellectual perfection," would not suffer such emotions.Stoics were concerned...

- EpicureanismEpicureanismEpicureanism is a system of philosophy based upon the teachings of Epicurus, founded around 307 BC. Epicurus was an atomic materialist, following in the steps of Democritus. His materialism led him to a general attack on superstition and divine intervention. Following Aristippus—about whom...

- NeoplatonismNeoplatonismNeoplatonism , is the modern term for a school of religious and mystical philosophy that took shape in the 3rd century AD, based on the teachings of Plato and earlier Platonists, with its earliest contributor believed to be Plotinus, and his teacher Ammonius Saccas...