Polish-Ukrainian War

Encyclopedia

The Polish–Ukrainian War of 1918 and 1919 was a conflict between the forces of the Second Polish Republic

and West Ukrainian People's Republic for the control over Eastern Galicia after the dissolution of Austria-Hungary

.

monarchy (see: Austria-Hungary

) was the perfect ground for the development of both Polish and Ukrainian national movements.

During 1848 revolution

, the Austrians concerned by Polish demands for greater autonomy within the province, gave support to a small group of Ruthenians (the name of the East Slavic people who would later adopt the self-identifcation of "Ukrainians") whose goal was to be recognized as a distinct nationality. After that, "Ruthenian language" schools were established, Ruthenian political parties formed, and the Ruthenians began attempts to develop their national culture. This came as a surprise to Poles, who until the revolution believed, along with most of the politically aware Ruthenians, that Ruthenians were part of the Polish nation (which, at that time, was defined in political rather than ethnographic terms). In the late 1890s and the first decades of the next century, the populist Ruthenian intelligentsia adopted the term Ukrainians to describe their nationality. Beginning with 20th century national conscience reached large number of Ruthenian peasants.

Multiple incidents between the two nations occurred throughout the latter 19th century and early 20th century. For example, in 1897 the Polish administration opposed the Ukrainians in parliamentary elections. Another conflict developed in the years 1901–1908 around Lviv University

, where Ukrainian students demanded a separate Ukrainian university, while Polish students and faculty attempted to suppress the movement. In 1903 both Poles and Ukrainians held separate conferences in Lviv (the Poles in May and Ukrainians in August). Afterwards, the two national movements developed with contradictory goals, leading towards the later clash.

The ethnic composition of Galicia underlay the conflict between the Poles and Ukrainians there. The Austrian province of Galicia consisted of territory seized from Poland in 1772, during the first partition

. This land, which included territory of historical importance to Poland, including the ancient capital of Kraków

, had a majority Polish population, although the eastern part of Galicia included the heartland of the historic territory of Galicia-Volhynia and had a Ukrainian majority.

In eastern Galicia, Ukrainians made up approximately 65% of the population while Poles made up only 22% of the population. Of the 44 administrative divisions of Austrian eastern Galicia, Lviv

, the biggest and capital city of the province, was the only one in which Poles made up a majority of the population. In Lviv, the population in 1910 was approximately 60% Polish and 17% Ukrainian. This city with its Polish inhabitants was considered one of Poland's cultural capitals. For many Poles, including Lviv's Polish population, it was unthinkable that their city should not be under Polish control.

The religious and ethnic divisions corresponded to social stratification. Galicia's leading social class were Polish nobles or descendants of Rus' gentry who had become polonized in the past, whereas, in the eastern part of the province Ruthenians (Ukrainians) constituted the majority of the peasant population. Poles and Jews were responsible for most of the commercial and industrial development in Galicia in the late 19th century.

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries the local Ukrainians attempted to persuade the Austrians to divide Galicia into Western (Polish) and Eastern (Ukrainian) provinces. These efforts were resisted and thwarted by those local Poles who feared losing control of Lviv and East Galicia. The Austrians eventually agreed in principle to divide the province of Galicia, but the onset of World War I prevented them from implementing this major change; in October 1916 the Austrian Emperor Karl I

promised to do so once the war had ended.

Due to the intervention of Archduke Wilhelm of Austria, who adopted a Ukrainian identity and considered himself a Ukrainian patriot, in October 1918 two regiments of mostly Ukrainian troops were garrisoned in Lemberg (modern Lviv). As the Austro-Hungarian

Due to the intervention of Archduke Wilhelm of Austria, who adopted a Ukrainian identity and considered himself a Ukrainian patriot, in October 1918 two regiments of mostly Ukrainian troops were garrisoned in Lemberg (modern Lviv). As the Austro-Hungarian

government collapsed, on October 18, 1918, the Ukrainian National Council (Rada), consisting of Ukrainian members of the Austrian parliament and regional Galician and Bukovynan

diets as well as leaders of Ukrainian political parties, was formed. The Council announced the intention to unite the West Ukrainian lands into a single state. As the Poles were taking their own steps to take over Lviv and Eastern Galicia, Captain Dmytro Vitovsky

of the Sich Riflemen

led the group of young Ukrainian officers in a decisive action and during the night of October 31 –- November 1, the Ukrainian military units took control over Lviv

. The West Ukrainian National Republic

was proclaimed on November 1, 1918 with Lviv as its capital.

The timing of proclamation of the Republic caught the Polish ethnic population and administration by surprise. The new Ukrainian Republic claimed sovereignty over Eastern Galicia, including the Carpathians

up to the city of Nowy Sącz

in the West, as well as Volhynia

, Carpathian Ruthenia

and Bukovina

(the last two territories were claimed also by Hungary

and Romania

respectively. Although the majority of the population of the Western-Ukrainian People's Republic were Ukrainians, large parts of the claimed territory, mostly urban settlements, had Polish majorities. In Lviv the Ukrainian residents enthusiastically supported the proclamation, the city's significant Jewish minority accepted or remained neutral towards the Ukrainian proclamation, while the city's Polish majority was shocked to find themselves in a proclaimed Ukrainian state. Because the West Ukrainian People's Republic was not internationally recognized and Poland's boundaries had not yet been defined, the issue of ownership of the disputed territory was reduced to a question of military control.

were opposed by local self-defence units formed mostly of World War I veterans, students and children. However, skill-full command, good tactics and high morale allowed Poles to resist the badly planned Ukrainian attacks. In addition, the Poles were able to skillfully buy time and wait for reinforcements through the arrangement of cease-fires with the Ukrainians.

While Poles could count on widespread support from the civilian population, the Ukrainian side was largely dependent on help from outside the city. Other uprisings against Ukrainian rule erupted in Drohobych

, Przemyśl

, Sambir

and Jarosław. In Przemyśl, local Ukrainian soldiers quickly dispersed to their homes and Poles seized the bridges over the River San and the railroad to Lviv, enabling the Polish forces in that city to obtain significant reinforcements.

After two weeks of heavy fighting within Lviv, an armed unit under the command of Lt. Colonel Michał Karaszewicz-Tokarzewski of the renascent Polish Army broke through the Ukrainian siege on November 21 and arrived in the city. The Ukrainians were repelled. Immediately after capturing the city, elements of the Polish forces as well as common criminals looted the Jewish and Ukrainian quarters of the city

, killing approximately 340 civilians. The Poles also interned a number of Ukrainian activists in detention camps. The Ukrainian government provided financial assistance to the Jewish victims of the Polish pogrom and were able to recruit a Jewish battalion into their army.

Some factions accuse these atrocities on the Blue Army of General Haller. This is unlikely as this French trained and supported fighting force did not leave France and the Western Front until April 1919, well after the rioting.

On November 9 Polish forces attempted to seize the Drohobych oil fields by surprise but, outnumbered by the Ukrainians, they were driven back. The Ukrainians would retain control over the oil fields until May 1919.

On November 11–12 Romanian troops seized Northern Bucovina without any resistance.

By the end of November 1918, Polish forces controlled Lviv and the railroad linking Lviv to central Poland through Przmysl, while Ukrainians controlled the rest of Eastern Galicia east of the river San, including the areas south and north of the railroad into Lviv. Lviv was thus surrounded on three sides by Ukrainian forces.

between Poland and the non-Galician forces of the Ukrainian People's Republic, based in Kiev

. As Polish units tried to seize control of the region, the forces of the Ukrainian People's Republic

under Symon Petlura

tried to expand their territory westwards, towards the city of Chełm .

The first major pogrom in this region took place in January 1919 in the town of Ovruch, where Jews were robbed and killed by regiments of affiliated with Petlura ataman

, Kozyr-Zyrka. Armed units of the Ukrainian People's Republic were also responsible for rapes, looting, and massacres in Zhytomir, in which 500-700 Jews lost their lives.

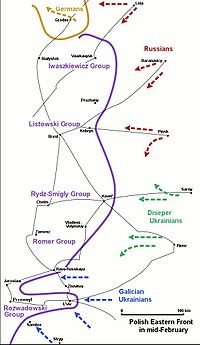

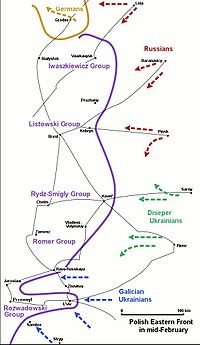

After two months of heavy fighting the conflict was resolved in March 1919 by fresh and well-equipped Polish units under General Edward Rydz-Śmigły.

Ukrainian forces continued to control most of eastern Galicia and were a threat to Lviv itself until May 1919. During this time, according to Italian and Polish reports, Ukrainian forces enjoyed high morale (an Italian observor behind Galician lines stated that the Ukrainians were fighting with the "courage of the doomed") while many of the Polish soldiers, particularly from what had been Congress Poland

, wanted to return home because they saw no reason to fight against Ruthenians over Ruthenian lands; the Polish forces were outnumbered by two to one and lacked ammunition. Despite being initally outnumbered, the Poles had certain advantages. Their forces had many more and better trained officers resulting in a better disciplined and more mobile force; the Poles also enjoyed excellent intelligence and, due to their control of railroads behind their lines, were able to move their soldiers quite quickly. As a result, although the Poles had fewer total troops than did the Ukrainians, in particularly important battles they were able to bring in as many soldiers as did the Ukrainians.

On December 9th, 1918 Ukrainian forces broke through the outer defences of Przmysl in the hope of capturing the city and thus cutting off Polish-controlled Lviv from entral Poland. However, the Poles were able to quickly send relief troops and by December 17th the Ukrainians were forced back. On December 27th, bolstered by peaant troops sent to Galicia from Eastern Ukraine in the hopes that the Western Ukrainians would be able to form a disciplined force out fo them, a general offense against Lviv began. Lviv's defences held, and the eastern Ukrainian troops mutinied.

From January 6-January 11th 1919 a Polish attack by 5,000 newly recruited forces from formerly Russian Poland

commanded by Jan Romer

was repulsed by Western Ukrainian forces near Rava-Ruska

, north of Lviv. Only a small number of troops together with Romer were able to break through to Lviv after suffering heavy losses. Between January 11th and January 13th, Polish forces attempted to dislodge Ukrainian troops besieging Lviv from the south while Ukrainian troops attempted another general assault on Lviv. Both efforts failed. In February 1919, Polish troops attempting to capture Sambir

were defeated by the Ukrainian defenders with heavy losses, although the poor mobility of the Ukrainian troops prevented them from taking advantage of this victory.

On February 14th, Ukrainian forces began another assault on Lviv. By February 20th, they were able to succesfully cut off the rail links between Lviv and Przmysl, leaving Lviv surrounded and the Ukrainian forces in a good position to take the city. However, a French-led mission from the Entente arrived at the Ukrainian headquarters in February 22nd and demanded that the Ukrainian cease hostilities under threat of breaking all diplomatic ties between the Entente and the Ukrainian government. On February 25th the Ukrainian military suspended its offensive. The Allied demands, which included the loss of significant amount of Ukrainian-held and inhabited territory, were however deemed to excessively favor the Poles by the Ukrainians, who resumed their offensive on March 4th. On March 5th Ukrainian artillery blew up the Polish forces' ammunition dump in Lviv; the resultant explosion caused a panic among Polish forces. The Ukrainains, however, failed to take advantage of this. During the time of the cease fire, the Poles had been able to organize a relief force of 8,000-10,000 troops which by March 12th reached Przmysl and by March 18th had driven the Ukrainian forces from the Lviv-Przmysl railroad, permanently securing Lviv.

On January 6–11 of 1919 a small part of the Ukrainian Galician Army invaded Transcarpathia

to spread pro-Ukrainian sentiments among residents (the region was occupied by Hungarians and Czechoslovaks). Ukrainian troops fought with Czechoslovak and Hungarian local police. They succeeded in capturing some Hungarian-controlled Ukrainian settlements. After some clashes with Czechoslovaks, the Ukrainians retreated because Czechoslovakia (instead of Ukrainian People's Republic

) was the only country that traded with the Western Ukrainian People's Republic and that supported it politically. Further conflict with Czech the authorities would have led to the complete economical and political isolation of the Western Ukrainian People's Republic.

. This army, numbering 60,000 troops, was well equipped by the Western allies and partially staffed with experienced French officers specifically in order to fight the Bolsheviks and not the forces of the Western Ukrainian People's Republic

. Despite this, the Poles dispatched Haller's army against the Ukrainians in order to break the stalemate in eastern Galicia. The allies sent several telegrams ordering the Poles to halt their offensive as using of the French-equipped army against the Ukrainian specifically contradicted the conditions of the French help, but these were ignored with Poles claiming that "all Ukrainians were Bolsheviks or something close to it".

At the same time, on May 23 Romania

opened a second front against Ukrainian forces, demanding their withdrawal from the southern sections of eastern Galicia including from the temporary capital of Stanislaviv

. This resulted in a loss of territory, ammunition and further isolation from the outside world.

The Ukrainian lines were broken, mostly due to the withdrawal of the elite Sich Riflemen

. On May 27 the Polish forces reached the Złota Lipa–Berezhany

-Jezierna-Radziwiłłów line. Following the demands of the Entente

, the Polish offensive was halted and the troops of General Haller adopted defensive positions.

, a former general in the Russian army, started a counter-offensive, and after three weeks advanced to Hnyla Lypa and the upper Styr river, defeating five Polish divisions. Although the Polish forces had been forced to withdraw, they were able to prevent their forces from collapsing and avoided being encircled and captured. Thus, in spite of their victories, the Ukrainian forces were unable to obtain significant amounts of arms and ammunition. By June 27th the Ukrainian forces had advanced 120 km. along the Dnister river and on another they had advanced 150 km, past the town of Brody

. They came to within two days' march of Lviv.

The successful Chortkiv offensive halted primarily because of a lack of arms - there were only 5-10 bullets for each Ukrainian soldier. The West Ukrainian government controlled the Drohobych

oil fields with which it planned to purchase arms for the struggle, but for political and diplomatic reasons weapons and ammunition could only be sent to Ukraine through Czechoslovakia. Although the Ukrainian forces managed to push the Poles back approximately 120-150 km. they failed to secure a route to Czechoslovakia. This meant that they were unable to replenish their supply of arms and ammunition, and the resulting lack of supplies forced Hrekov to end his campaign.

Józef Piłsudski assumed the command of the Polish forces on June 27 and started yet another offensive, helped by two fresh Polish divisions. On June 28, the Polish offensive began. Short of ammunition and facing an enemy now twice its size, the Ukrainians were pushed back to the line of the river Zbruch

by mid-July 1919. Although the Ukrainian infantry had run out of ammunition, its artillery had not. This provided the Ukrainian forces with cover for an orderly retreat. Approximately 100,000 civilian refugees and 60,000 troops, 20,000 of whom were combat ready, were able to escape across the Zbruch River into Eastern Ukraine.

that ended the first world war was based on the principle of national self-determination

. Accordingly, the diplomats of the West Ukrainian People's Republic hoped that the West would compel Poland to withdraw from territories with a Ukrainian demographic majority.

Opinion among the allies was divided. Britain, under the leadership of prime minister David Lloyd George

, and to a lesser extent Italy were opposed to Polish expansion. Their representatives maintained that granting the territory of the Western Ukrainian People's Republic to Poland would violate the principle of national self-determination and that hostile national minorities would undermine the Polish state. In reality, the British policy was dictated by unwillingness to harm Russian interests in the region and alienate the future Russian state through preventing possible union of Eastern Galicia with Russia. In addition, Britain was interested in Western Ukraine's oil fields. Czechoslovakia, itself involved in a conflict with Poland

, was friendly towards the Ukrainian government and sold it weapons in exhange for oil. France, on the other hand, strongly supported Poland in the conflict. The French hoped that a large, powerful Polish state would serve as a counterbalance to Germany and would isolate Germany from Bolshevik Russia. French diplomats consistently supported Polish claims to territories also claimed by Germany, Lithuania and Ukraine. The French also provided large numbers of arms and ammunition, and French officers, to Polish forces that were used against the western Ukrainian military.

The successful defence by the Ukrainian Galician Army of most of the Western Ukrainian People's Republic territory in winter 1918-1919 prompted a diplomatic offensive by the Poles which sought to portray Ukrainian forces as Bolshevik, pro-German, or both, and which claimed that Ukrainians were illiterate, anarchic and unable to administer their own state. Polish diplomats declared that Ukrainians "were very ripe for Bolshevism, because they are very much under German influence...and the Ukrainian people are led by a gang very similar to the Bolshevists..."

In attempt to end the war, in January 1919 an Allied commission led by a French general was sent to negotiate a peace treaty between the two sides, prompting a ceasefire. In February it recommended that the Western Ukrainian People's Republic surrender a third of its territory, including the city of Lviv

and the Drohobych

oil fields. The Ukrainians refused and broke diplomatic ties with Poland. In mid-March 1919, the French marshal Ferdinand Foch

, who wanted to use Poland as a operational base for an offensive against the Red Army, brought the issue of Polish-Ukrainian war before the Supreme Council

and appealed for large-scale Polish-Romanian military operation which would be conducted with Allied support, as well as sending Haller's divisions to Poland immediately to relieve Lviv from Ukrainian siege.

Another Allied commission, led by South African General Louis Botha

, proposed an armistice in May that would involve the Ukrainians keeping the Drohobych oil fields and the Poles keeping Lviv. The Ukrainian side agreed to this proposal but it was rejected by the Poles on the grounds that it didn't take into consideration the overall military situation of Poland and the circumstances on the eastern front. The Bolshevik army broke through the UNR

forces and was advancing to Podolia and Volhynia. The Poles argued that they need military control over whole Eastern Galicia to secure the Russian front in its southern part and strengthen it by a junction with Romania. The Poles launched an attack soon afterward using a large force equipped by the French (Haller's Army), which captured most of the territory of the West Ukrainian People's Republic. Urgent telegrams by the Western allies to halt this offensive were ignored. In late June 1919, the Allied Council approved the resolution allowing the Polish army (including Haller's troops) to advance through Eastern Galicia to the River Zbruch.

Czechoslovakia, which had inherited seven oil refinaries from prewar Austrian times and which was dependent on its contracts for oil with the Ukrainian government, demanded that the Poles send the Czechs the oil that had been paid for to the Ukrainian government. The Poles refused, stating that the oil was paid for with ammunition that had been used against Polish soldiers. Although the Czechs did not retaliate, according to Polish reports the Czechs considered seizing the oil fields from the Poles and returning them to the Ukrainians who would honor their contracts.

On November 21, 1919, the Highest Council of the Paris Peace Conference

granted Eastern Galicia to Poland for a period of 25 years, after which a plebiscite was to be held there. On April 21, 1920, Józef Piłsudski and Symon Petliura signed an alliance

, in which Poland promised the Ukrainian People's Republic

the military help in the Kiev Offensive

against the Red Army

in exchange for the acceptance of Polish-Ukrainian border on the river Zbruch

.

Following this agreement, the government of the West Ukrainian National Republic

went into exile in Vienna, where it enjoyed the support of various Western Ukrainian political emigrees as well as soldiers of the Galician army interned in Bohemia. Although not officially recognized by any state as the government of western Ukraine, it engaged in diplomatic activity with the French and British governments in the hopes of obtaining a favourable settlement at Versailles. As a result of its efforts, the council of the League of Nations declared on February 23, 1921 that Galicia lay outside the territory of Poland and that Poland did not have the mandate to establish administrative control in that country, and that Poland was merely the occupying military power of eastern Galicia, whose fate would be determined by the Council of Ambassadors at the League of Nations. However, the Conference of Ambassadors

in Paris stated on July 8, 1921 that so called "West Ukrainian Government" of Yevhen Petrushevych

did not constitute a government either the facto or de jure and did not have the right to represent any of the territories formerly belonging to the Austrian empire.

After a long series of negotiations, on March 14, 1923 it was decided that eastern Galicia would be incorporated into Poland "taking into consideration that Poland has recognized that in regard to the eastern part of Galicia ethnographic conditions fully deserve its autonomous status." The government of the West Ukrainian National Republic then disbanded, while Poland reneged on its promise of autonomy for eastern Galicia.

was signed. Ukrainian POWs were kept in ex-Austrian POW camps in Dąbie (Kraków), Łańcut, Pikulice

, Strzałków, and Wadowice

.

Following the war, the French, who had supported Poland diplomatically and militarily, obtained control over the eastern Galician oil fields under conditions that were very unfavorable to Poland.

In the beginning of Second World War

, the area was annexed by the Soviet Union

and attached to Ukraine, which at that time was a republic of the Soviet Union. According to the Yalta Conference

decisions, while Polish population of Eastern Galicia was resettled to Poland which borders were shifted westwards, the region itself remained within the Soviet Ukraine after the war and currently forms the westernmost part of now independent Ukraine

.

lost their war, and their territory was annexed by Poland, the experience of proclaiming a Ukrainian state and fighting for it significantly intensified and deepened the patriotic Ukrainian orientation within Galicia. Since the interwar era, Galicia has been the center of Ukrainian nationalism

.

According to a noted interwar Polish publicist, the Polish-Ukrainian war was the principal cause for the failure to establish a Ukrainian state in Kiev in late 1918 and early 1919. During that critical time the Galician forces, large, well-disciplined and immune to Communist subversion, could have tilted the balance of power in favor of a Ukrainian state. Instead, it focused all of its resources on defending its Galician homeland. By the time the western Ukrainian forces did transfer East in the summer of 1919 after having been overwehlmed by the Poles, the Russian forces had grown significantly and the impact of the Galicians was not decisive.

After the war the Ukrainian soldiers who fought in this war became the subject of folk songs and their graves a site of annual pilgrimages in western Ukraine which persisted into Soviet times despite persecution by the Soviet authorities of those honoring the Ukrainian troops.

Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, Second Commonwealth of Poland or interwar Poland refers to Poland between the two world wars; a period in Polish history in which Poland was restored as an independent state. Officially known as the Republic of Poland or the Commonwealth of Poland , the Polish state was...

and West Ukrainian People's Republic for the control over Eastern Galicia after the dissolution of Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary , more formally known as the Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Imperial Council and the Lands of the Holy Hungarian Crown of Saint Stephen, was a constitutional monarchic union between the crowns of the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary in...

.

Background

The origins of the conflict lie in the complex nationality situation in Galicia at the turn of the 20th century. As a result of its relative leniency toward national minorities, the HabsburgHabsburg

The House of Habsburg , also found as Hapsburg, and also known as House of Austria is one of the most important royal houses of Europe and is best known for being an origin of all of the formally elected Holy Roman Emperors between 1438 and 1740, as well as rulers of the Austrian Empire and...

monarchy (see: Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary , more formally known as the Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Imperial Council and the Lands of the Holy Hungarian Crown of Saint Stephen, was a constitutional monarchic union between the crowns of the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary in...

) was the perfect ground for the development of both Polish and Ukrainian national movements.

During 1848 revolution

Revolutions of 1848

The European Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Spring of Nations, Springtime of the Peoples or the Year of Revolution, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe in 1848. It was the first Europe-wide collapse of traditional authority, but within a year reactionary...

, the Austrians concerned by Polish demands for greater autonomy within the province, gave support to a small group of Ruthenians (the name of the East Slavic people who would later adopt the self-identifcation of "Ukrainians") whose goal was to be recognized as a distinct nationality. After that, "Ruthenian language" schools were established, Ruthenian political parties formed, and the Ruthenians began attempts to develop their national culture. This came as a surprise to Poles, who until the revolution believed, along with most of the politically aware Ruthenians, that Ruthenians were part of the Polish nation (which, at that time, was defined in political rather than ethnographic terms). In the late 1890s and the first decades of the next century, the populist Ruthenian intelligentsia adopted the term Ukrainians to describe their nationality. Beginning with 20th century national conscience reached large number of Ruthenian peasants.

Multiple incidents between the two nations occurred throughout the latter 19th century and early 20th century. For example, in 1897 the Polish administration opposed the Ukrainians in parliamentary elections. Another conflict developed in the years 1901–1908 around Lviv University

Lviv University

The Lviv University or officially the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv is the oldest continuously operating university in Ukraine...

, where Ukrainian students demanded a separate Ukrainian university, while Polish students and faculty attempted to suppress the movement. In 1903 both Poles and Ukrainians held separate conferences in Lviv (the Poles in May and Ukrainians in August). Afterwards, the two national movements developed with contradictory goals, leading towards the later clash.

The ethnic composition of Galicia underlay the conflict between the Poles and Ukrainians there. The Austrian province of Galicia consisted of territory seized from Poland in 1772, during the first partition

Partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland or Partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth took place in the second half of the 18th century and ended the existence of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland for 123 years...

. This land, which included territory of historical importance to Poland, including the ancient capital of Kraków

Kraków

Kraków also Krakow, or Cracow , is the second largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in the Lesser Poland region, the city dates back to the 7th century. Kraków has traditionally been one of the leading centres of Polish academic, cultural, and artistic life...

, had a majority Polish population, although the eastern part of Galicia included the heartland of the historic territory of Galicia-Volhynia and had a Ukrainian majority.

In eastern Galicia, Ukrainians made up approximately 65% of the population while Poles made up only 22% of the population. Of the 44 administrative divisions of Austrian eastern Galicia, Lviv

Lviv

Lviv is a city in western Ukraine. The city is regarded as one of the main cultural centres of today's Ukraine and historically has also been a major Polish and Jewish cultural center, as Poles and Jews were the two main ethnicities of the city until the outbreak of World War II and the following...

, the biggest and capital city of the province, was the only one in which Poles made up a majority of the population. In Lviv, the population in 1910 was approximately 60% Polish and 17% Ukrainian. This city with its Polish inhabitants was considered one of Poland's cultural capitals. For many Poles, including Lviv's Polish population, it was unthinkable that their city should not be under Polish control.

The religious and ethnic divisions corresponded to social stratification. Galicia's leading social class were Polish nobles or descendants of Rus' gentry who had become polonized in the past, whereas, in the eastern part of the province Ruthenians (Ukrainians) constituted the majority of the peasant population. Poles and Jews were responsible for most of the commercial and industrial development in Galicia in the late 19th century.

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries the local Ukrainians attempted to persuade the Austrians to divide Galicia into Western (Polish) and Eastern (Ukrainian) provinces. These efforts were resisted and thwarted by those local Poles who feared losing control of Lviv and East Galicia. The Austrians eventually agreed in principle to divide the province of Galicia, but the onset of World War I prevented them from implementing this major change; in October 1916 the Austrian Emperor Karl I

Karl I of Austria

Charles I of Austria or Charles IV of Hungary was the last ruler of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He was the last Emperor of Austria, the last King of Hungary, the last King of Bohemia and Croatia and the last King of Galicia and Lodomeria and the last monarch of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine...

promised to do so once the war had ended.

Prelude

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary , more formally known as the Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Imperial Council and the Lands of the Holy Hungarian Crown of Saint Stephen, was a constitutional monarchic union between the crowns of the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary in...

government collapsed, on October 18, 1918, the Ukrainian National Council (Rada), consisting of Ukrainian members of the Austrian parliament and regional Galician and Bukovynan

Bukovina

Bukovina is a historical region on the northern slopes of the northeastern Carpathian Mountains and the adjoining plains.-Name:The name Bukovina came into official use in 1775 with the region's annexation from the Principality of Moldavia to the possessions of the Habsburg Monarchy, which became...

diets as well as leaders of Ukrainian political parties, was formed. The Council announced the intention to unite the West Ukrainian lands into a single state. As the Poles were taking their own steps to take over Lviv and Eastern Galicia, Captain Dmytro Vitovsky

Dmytro Vitovsky

Dmytro Vitovsky was a Ukrainian politician and military leader....

of the Sich Riflemen

Sich Riflemen

The Sich Riflemen Halych-Bukovyna Kurin were one of the first regular military units of the Army of the Ukrainian People's Republic. The unit operated from 1917 to 1919 and was formed from Ukrainian soldiers of the Austro-Hungarian army, local population and former commanders of the Ukrainian Sich...

led the group of young Ukrainian officers in a decisive action and during the night of October 31 –- November 1, the Ukrainian military units took control over Lviv

Lviv

Lviv is a city in western Ukraine. The city is regarded as one of the main cultural centres of today's Ukraine and historically has also been a major Polish and Jewish cultural center, as Poles and Jews were the two main ethnicities of the city until the outbreak of World War II and the following...

. The West Ukrainian National Republic

West Ukrainian National Republic

The West Ukrainian People's Republic was a short-lived republic that existed in late 1918 and early 1919 in eastern Galicia, that claimed parts of Bukovina and Carpathian Ruthenia and included the cities of Lviv , Przemyśl , Kolomyia , and Stanislaviv...

was proclaimed on November 1, 1918 with Lviv as its capital.

The timing of proclamation of the Republic caught the Polish ethnic population and administration by surprise. The new Ukrainian Republic claimed sovereignty over Eastern Galicia, including the Carpathians

Carpathian Mountains

The Carpathian Mountains or Carpathians are a range of mountains forming an arc roughly long across Central and Eastern Europe, making them the second-longest mountain range in Europe...

up to the city of Nowy Sącz

Nowy Sacz

Nowy Sącz is a town in the Lesser Poland Voivodeship in southern Poland. It is the district capital of Nowy Sącz County, but is not included within the powiat.-Names:...

in the West, as well as Volhynia

Volhynia

Volhynia, Volynia, or Volyn is a historic region in western Ukraine located between the rivers Prypiat and Southern Bug River, to the north of Galicia and Podolia; the region is named for the former city of Volyn or Velyn, said to have been located on the Southern Bug River, whose name may come...

, Carpathian Ruthenia

Carpathian Ruthenia

Carpathian Ruthenia is a region in Eastern Europe, mostly located in western Ukraine's Zakarpattia Oblast , with smaller parts in easternmost Slovakia , Poland's Lemkovyna and Romanian Maramureş.It is...

and Bukovina

Bukovina

Bukovina is a historical region on the northern slopes of the northeastern Carpathian Mountains and the adjoining plains.-Name:The name Bukovina came into official use in 1775 with the region's annexation from the Principality of Moldavia to the possessions of the Habsburg Monarchy, which became...

(the last two territories were claimed also by Hungary

Hungary

Hungary , officially the Republic of Hungary , is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Carpathian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The...

and Romania

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeastern Europe, on the Lower Danube, within and outside the Carpathian arch, bordering on the Black Sea...

respectively. Although the majority of the population of the Western-Ukrainian People's Republic were Ukrainians, large parts of the claimed territory, mostly urban settlements, had Polish majorities. In Lviv the Ukrainian residents enthusiastically supported the proclamation, the city's significant Jewish minority accepted or remained neutral towards the Ukrainian proclamation, while the city's Polish majority was shocked to find themselves in a proclaimed Ukrainian state. Because the West Ukrainian People's Republic was not internationally recognized and Poland's boundaries had not yet been defined, the issue of ownership of the disputed territory was reduced to a question of military control.

The War

Initial Stages

Fighting between Ukrainian and Polish forces was concentrated around the declared Ukrainian capital of Lviv and the approaches to that city. In Lviv, the Ukrainian forcesUkrainian Galician Army

Ukrainian Galician Army , was the Ukrainian military of the West Ukrainian National Republic during and after the Polish-Ukrainian War. -Military equipment:...

were opposed by local self-defence units formed mostly of World War I veterans, students and children. However, skill-full command, good tactics and high morale allowed Poles to resist the badly planned Ukrainian attacks. In addition, the Poles were able to skillfully buy time and wait for reinforcements through the arrangement of cease-fires with the Ukrainians.

While Poles could count on widespread support from the civilian population, the Ukrainian side was largely dependent on help from outside the city. Other uprisings against Ukrainian rule erupted in Drohobych

Drohobych

Drohobych is a city located at the confluence of the Tysmenytsia River and Seret, a tributary of the former, in the Lviv Oblast , in western Ukraine...

, Przemyśl

Przemysl

Przemyśl is a city in south-eastern Poland with 66,756 inhabitants, as of June 2009. In 1999, it became part of the Podkarpackie Voivodeship; it was previously the capital of Przemyśl Voivodeship....

, Sambir

Sambir

Sambir is a city in the Lviv Oblast, Ukraine. Serving as the administrative center of the Sambir Raion , the city itself is also designated as a separate raion within the oblast. It is located at around , close to the border with Poland.-History:...

and Jarosław. In Przemyśl, local Ukrainian soldiers quickly dispersed to their homes and Poles seized the bridges over the River San and the railroad to Lviv, enabling the Polish forces in that city to obtain significant reinforcements.

After two weeks of heavy fighting within Lviv, an armed unit under the command of Lt. Colonel Michał Karaszewicz-Tokarzewski of the renascent Polish Army broke through the Ukrainian siege on November 21 and arrived in the city. The Ukrainians were repelled. Immediately after capturing the city, elements of the Polish forces as well as common criminals looted the Jewish and Ukrainian quarters of the city

Lwów pogrom (1918)

The Lwów pogrom of the Jewish population of Lwów took place on November 21–23, 1918 during the Polish-Ukrainian War. In the course of the three days of unrest in the city, an estimated 52-150 Jewish residents were murdered and hundreds injured, with widespread looting carried out by Polish...

, killing approximately 340 civilians. The Poles also interned a number of Ukrainian activists in detention camps. The Ukrainian government provided financial assistance to the Jewish victims of the Polish pogrom and were able to recruit a Jewish battalion into their army.

Some factions accuse these atrocities on the Blue Army of General Haller. This is unlikely as this French trained and supported fighting force did not leave France and the Western Front until April 1919, well after the rioting.

On November 9 Polish forces attempted to seize the Drohobych oil fields by surprise but, outnumbered by the Ukrainians, they were driven back. The Ukrainians would retain control over the oil fields until May 1919.

On November 11–12 Romanian troops seized Northern Bucovina without any resistance.

By the end of November 1918, Polish forces controlled Lviv and the railroad linking Lviv to central Poland through Przmysl, while Ukrainians controlled the rest of Eastern Galicia east of the river San, including the areas south and north of the railroad into Lviv. Lviv was thus surrounded on three sides by Ukrainian forces.

Battles over Volhynia

In December 1918 fighting started in VolhyniaVolhynia

Volhynia, Volynia, or Volyn is a historic region in western Ukraine located between the rivers Prypiat and Southern Bug River, to the north of Galicia and Podolia; the region is named for the former city of Volyn or Velyn, said to have been located on the Southern Bug River, whose name may come...

between Poland and the non-Galician forces of the Ukrainian People's Republic, based in Kiev

Kiev

Kiev or Kyiv is the capital and the largest city of Ukraine, located in the north central part of the country on the Dnieper River. The population as of the 2001 census was 2,611,300. However, higher numbers have been cited in the press....

. As Polish units tried to seize control of the region, the forces of the Ukrainian People's Republic

Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic or Ukrainian National Republic was a republic that was declared in part of the territory of modern Ukraine after the Russian Revolution, eventually headed by Symon Petliura.-Revolutionary Wave:...

under Symon Petlura

Symon Petlura

Symon Vasylyovych Petliura was a publicist, writer, journalist, Ukrainian politician, statesman, and national leader who led Ukraine's struggle for independence following the Russian Revolution of 1917....

tried to expand their territory westwards, towards the city of Chełm .

The first major pogrom in this region took place in January 1919 in the town of Ovruch, where Jews were robbed and killed by regiments of affiliated with Petlura ataman

Ataman

Ataman was a commander title of the Ukrainian People's Army, Cossack, and haidamak leaders, who were in essence the Cossacks...

, Kozyr-Zyrka. Armed units of the Ukrainian People's Republic were also responsible for rapes, looting, and massacres in Zhytomir, in which 500-700 Jews lost their lives.

After two months of heavy fighting the conflict was resolved in March 1919 by fresh and well-equipped Polish units under General Edward Rydz-Śmigły.

Stalemate in Eastern Galicia

Thanks to fast and effective mobilization in December 1918, the Ukrainians possessed a large numerical advantage until February 1919, and pushed the Poles into defensive positions. According to an American report from the period of January 13 - February 1 1919, Ukrainians eventually managed to surround Lviv on three sides. The city's inhabitants were deprived of water supply and electricity. Ukrainian army also held villages on both sidelines of the railway leading to Przemyśl.Ukrainian forces continued to control most of eastern Galicia and were a threat to Lviv itself until May 1919. During this time, according to Italian and Polish reports, Ukrainian forces enjoyed high morale (an Italian observor behind Galician lines stated that the Ukrainians were fighting with the "courage of the doomed") while many of the Polish soldiers, particularly from what had been Congress Poland

Congress Poland

The Kingdom of Poland , informally known as Congress Poland , created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna, was a personal union of the Russian parcel of Poland with the Russian Empire...

, wanted to return home because they saw no reason to fight against Ruthenians over Ruthenian lands; the Polish forces were outnumbered by two to one and lacked ammunition. Despite being initally outnumbered, the Poles had certain advantages. Their forces had many more and better trained officers resulting in a better disciplined and more mobile force; the Poles also enjoyed excellent intelligence and, due to their control of railroads behind their lines, were able to move their soldiers quite quickly. As a result, although the Poles had fewer total troops than did the Ukrainians, in particularly important battles they were able to bring in as many soldiers as did the Ukrainians.

On December 9th, 1918 Ukrainian forces broke through the outer defences of Przmysl in the hope of capturing the city and thus cutting off Polish-controlled Lviv from entral Poland. However, the Poles were able to quickly send relief troops and by December 17th the Ukrainians were forced back. On December 27th, bolstered by peaant troops sent to Galicia from Eastern Ukraine in the hopes that the Western Ukrainians would be able to form a disciplined force out fo them, a general offense against Lviv began. Lviv's defences held, and the eastern Ukrainian troops mutinied.

From January 6-January 11th 1919 a Polish attack by 5,000 newly recruited forces from formerly Russian Poland

Congress Poland

The Kingdom of Poland , informally known as Congress Poland , created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna, was a personal union of the Russian parcel of Poland with the Russian Empire...

commanded by Jan Romer

Jan Romer

Jan Romer was an Austrian and Polish general. Studied in Mödling and joined the Austro-Hungarian Army. During the First World War fought at the battle of Limanowa and battle of Gorlice , was wounded twice. Later he joined the newly recreated Polish Army. During Polish-Ukrainian War he fought in...

was repulsed by Western Ukrainian forces near Rava-Ruska

Rava-Ruska

Rava-Ruska is a city in the Lviv Oblast of western Ukraine.It is located near the border with Poland, opposite the town of Hrebenne. It is located in the Zhovkva Raion at around . The current estimated population is 8,100 ....

, north of Lviv. Only a small number of troops together with Romer were able to break through to Lviv after suffering heavy losses. Between January 11th and January 13th, Polish forces attempted to dislodge Ukrainian troops besieging Lviv from the south while Ukrainian troops attempted another general assault on Lviv. Both efforts failed. In February 1919, Polish troops attempting to capture Sambir

Sambir

Sambir is a city in the Lviv Oblast, Ukraine. Serving as the administrative center of the Sambir Raion , the city itself is also designated as a separate raion within the oblast. It is located at around , close to the border with Poland.-History:...

were defeated by the Ukrainian defenders with heavy losses, although the poor mobility of the Ukrainian troops prevented them from taking advantage of this victory.

On February 14th, Ukrainian forces began another assault on Lviv. By February 20th, they were able to succesfully cut off the rail links between Lviv and Przmysl, leaving Lviv surrounded and the Ukrainian forces in a good position to take the city. However, a French-led mission from the Entente arrived at the Ukrainian headquarters in February 22nd and demanded that the Ukrainian cease hostilities under threat of breaking all diplomatic ties between the Entente and the Ukrainian government. On February 25th the Ukrainian military suspended its offensive. The Allied demands, which included the loss of significant amount of Ukrainian-held and inhabited territory, were however deemed to excessively favor the Poles by the Ukrainians, who resumed their offensive on March 4th. On March 5th Ukrainian artillery blew up the Polish forces' ammunition dump in Lviv; the resultant explosion caused a panic among Polish forces. The Ukrainains, however, failed to take advantage of this. During the time of the cease fire, the Poles had been able to organize a relief force of 8,000-10,000 troops which by March 12th reached Przmysl and by March 18th had driven the Ukrainian forces from the Lviv-Przmysl railroad, permanently securing Lviv.

On January 6–11 of 1919 a small part of the Ukrainian Galician Army invaded Transcarpathia

Transcarpathia

Transcarpathia may refer to:* Carpathian Ruthenia, a historic region* Zakarpattia Oblast, an administrative unit of Ukraine, roughly covering the same area as Carpathian Ruthenia...

to spread pro-Ukrainian sentiments among residents (the region was occupied by Hungarians and Czechoslovaks). Ukrainian troops fought with Czechoslovak and Hungarian local police. They succeeded in capturing some Hungarian-controlled Ukrainian settlements. After some clashes with Czechoslovaks, the Ukrainians retreated because Czechoslovakia (instead of Ukrainian People's Republic

Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic or Ukrainian National Republic was a republic that was declared in part of the territory of modern Ukraine after the Russian Revolution, eventually headed by Symon Petliura.-Revolutionary Wave:...

) was the only country that traded with the Western Ukrainian People's Republic and that supported it politically. Further conflict with Czech the authorities would have led to the complete economical and political isolation of the Western Ukrainian People's Republic.

Ukrainian Collapse

A Polish general offensive throughout Volhynia and Eastern Galicia began on May 14, 1919. It was carried out by units of the Polish Army aided by the newly-arrived Blue Army of General Józef Haller de HallenburgJózef Haller de Hallenburg

Józef Haller de Hallenburg was a Lieutenant General of the Polish Army, legionary in Polish Legions, harcmistrz , the President of The Polish Scouting and Guiding Association , political and social activist, Stanisław Haller de Hallenburg's cousin.Haller was born in Jurczyce...

. This army, numbering 60,000 troops, was well equipped by the Western allies and partially staffed with experienced French officers specifically in order to fight the Bolsheviks and not the forces of the Western Ukrainian People's Republic

Ukrainian Galician Army

Ukrainian Galician Army , was the Ukrainian military of the West Ukrainian National Republic during and after the Polish-Ukrainian War. -Military equipment:...

. Despite this, the Poles dispatched Haller's army against the Ukrainians in order to break the stalemate in eastern Galicia. The allies sent several telegrams ordering the Poles to halt their offensive as using of the French-equipped army against the Ukrainian specifically contradicted the conditions of the French help, but these were ignored with Poles claiming that "all Ukrainians were Bolsheviks or something close to it".

At the same time, on May 23 Romania

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeastern Europe, on the Lower Danube, within and outside the Carpathian arch, bordering on the Black Sea...

opened a second front against Ukrainian forces, demanding their withdrawal from the southern sections of eastern Galicia including from the temporary capital of Stanislaviv

Ivano-Frankivsk

Ivano-Frankivsk is a historic city located in the western Ukraine. It is the administrative centre of the Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast , and is designated as its own separate raion within the oblast, municipality....

. This resulted in a loss of territory, ammunition and further isolation from the outside world.

The Ukrainian lines were broken, mostly due to the withdrawal of the elite Sich Riflemen

Sich Riflemen

The Sich Riflemen Halych-Bukovyna Kurin were one of the first regular military units of the Army of the Ukrainian People's Republic. The unit operated from 1917 to 1919 and was formed from Ukrainian soldiers of the Austro-Hungarian army, local population and former commanders of the Ukrainian Sich...

. On May 27 the Polish forces reached the Złota Lipa–Berezhany

Berezhany

Berezhany is a city located in the Ternopil Oblast of western Ukraine. It is the administrative center of the Berezhanskyi Raion , and rests about 100 km from Lviv and 50 km from the oblast capital, Ternopil. The city has a population of about 20,000, and is about 400 m above sea level...

-Jezierna-Radziwiłłów line. Following the demands of the Entente

Triple Entente

The Triple Entente was the name given to the alliance among Britain, France and Russia after the signing of the Anglo-Russian Entente in 1907....

, the Polish offensive was halted and the troops of General Haller adopted defensive positions.

Chortkiv Offensive and Ultimate Polish Victory

On June 8, 1919, the Ukrainian forces under the new command of Oleksander HrekovOleksander Hrekov

Oleksander Petrovych Hrekov was a general of the Imperial Russian Army, Ukrainian People's Army, military professor and one of the most prominent personalities in the History of Ukraine...

, a former general in the Russian army, started a counter-offensive, and after three weeks advanced to Hnyla Lypa and the upper Styr river, defeating five Polish divisions. Although the Polish forces had been forced to withdraw, they were able to prevent their forces from collapsing and avoided being encircled and captured. Thus, in spite of their victories, the Ukrainian forces were unable to obtain significant amounts of arms and ammunition. By June 27th the Ukrainian forces had advanced 120 km. along the Dnister river and on another they had advanced 150 km, past the town of Brody

Brody

Brody is a city in the Lviv Oblast of western Ukraine. It is the administrative center of the Brody Raion , and is located in the valley of the upper Styr River, approximately 90 kilometres northeast of the oblast capital, Lviv...

. They came to within two days' march of Lviv.

The successful Chortkiv offensive halted primarily because of a lack of arms - there were only 5-10 bullets for each Ukrainian soldier. The West Ukrainian government controlled the Drohobych

Drohobych

Drohobych is a city located at the confluence of the Tysmenytsia River and Seret, a tributary of the former, in the Lviv Oblast , in western Ukraine...

oil fields with which it planned to purchase arms for the struggle, but for political and diplomatic reasons weapons and ammunition could only be sent to Ukraine through Czechoslovakia. Although the Ukrainian forces managed to push the Poles back approximately 120-150 km. they failed to secure a route to Czechoslovakia. This meant that they were unable to replenish their supply of arms and ammunition, and the resulting lack of supplies forced Hrekov to end his campaign.

Józef Piłsudski assumed the command of the Polish forces on June 27 and started yet another offensive, helped by two fresh Polish divisions. On June 28, the Polish offensive began. Short of ammunition and facing an enemy now twice its size, the Ukrainians were pushed back to the line of the river Zbruch

Zbruch River

Zbruch River is a river in Western Ukraine, a left tributary of the Dniester.It flows within the Podolia Upland starting from the Avratinian Upland. Zbruch is the namesake of the Zbruch idol, a sculpture of a Slavic deity in the form of a column with a head with four faces, discovered in 1848 by...

by mid-July 1919. Although the Ukrainian infantry had run out of ammunition, its artillery had not. This provided the Ukrainian forces with cover for an orderly retreat. Approximately 100,000 civilian refugees and 60,000 troops, 20,000 of whom were combat ready, were able to escape across the Zbruch River into Eastern Ukraine.

The Diplomatic Front

The Polish and Ukrainian forces struggled on the diplomatic as well as military fronts both during and after the war. The Ukrainians hoped that the western allies of World War I would support their cause because the Treaty of VersaillesTreaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was one of the peace treaties at the end of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The other Central Powers on the German side of...

that ended the first world war was based on the principle of national self-determination

Self-determination

Self-determination is the principle in international law that nations have the right to freely choose their sovereignty and international political status with no external compulsion or external interference...

. Accordingly, the diplomats of the West Ukrainian People's Republic hoped that the West would compel Poland to withdraw from territories with a Ukrainian demographic majority.

Opinion among the allies was divided. Britain, under the leadership of prime minister David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor OM, PC was a British Liberal politician and statesman...

, and to a lesser extent Italy were opposed to Polish expansion. Their representatives maintained that granting the territory of the Western Ukrainian People's Republic to Poland would violate the principle of national self-determination and that hostile national minorities would undermine the Polish state. In reality, the British policy was dictated by unwillingness to harm Russian interests in the region and alienate the future Russian state through preventing possible union of Eastern Galicia with Russia. In addition, Britain was interested in Western Ukraine's oil fields. Czechoslovakia, itself involved in a conflict with Poland

Polish–Czechoslovak War

The Poland–Czechoslovakia war, also known mostly in Czech sources as the Seven-day war was a military confrontation between Czechoslovakia and Poland over the territory of Cieszyn Silesia in 1919....

, was friendly towards the Ukrainian government and sold it weapons in exhange for oil. France, on the other hand, strongly supported Poland in the conflict. The French hoped that a large, powerful Polish state would serve as a counterbalance to Germany and would isolate Germany from Bolshevik Russia. French diplomats consistently supported Polish claims to territories also claimed by Germany, Lithuania and Ukraine. The French also provided large numbers of arms and ammunition, and French officers, to Polish forces that were used against the western Ukrainian military.

The successful defence by the Ukrainian Galician Army of most of the Western Ukrainian People's Republic territory in winter 1918-1919 prompted a diplomatic offensive by the Poles which sought to portray Ukrainian forces as Bolshevik, pro-German, or both, and which claimed that Ukrainians were illiterate, anarchic and unable to administer their own state. Polish diplomats declared that Ukrainians "were very ripe for Bolshevism, because they are very much under German influence...and the Ukrainian people are led by a gang very similar to the Bolshevists..."

In attempt to end the war, in January 1919 an Allied commission led by a French general was sent to negotiate a peace treaty between the two sides, prompting a ceasefire. In February it recommended that the Western Ukrainian People's Republic surrender a third of its territory, including the city of Lviv

Lviv

Lviv is a city in western Ukraine. The city is regarded as one of the main cultural centres of today's Ukraine and historically has also been a major Polish and Jewish cultural center, as Poles and Jews were the two main ethnicities of the city until the outbreak of World War II and the following...

and the Drohobych

Drohobych

Drohobych is a city located at the confluence of the Tysmenytsia River and Seret, a tributary of the former, in the Lviv Oblast , in western Ukraine...

oil fields. The Ukrainians refused and broke diplomatic ties with Poland. In mid-March 1919, the French marshal Ferdinand Foch

Ferdinand Foch

Ferdinand Foch , GCB, OM, DSO was a French soldier, war hero, military theorist, and writer credited with possessing "the most original and subtle mind in the French army" in the early 20th century. He served as general in the French army during World War I and was made Marshal of France in its...

, who wanted to use Poland as a operational base for an offensive against the Red Army, brought the issue of Polish-Ukrainian war before the Supreme Council

Supreme War Council

The Supreme War Council was a central command created by British Prime Minister David Lloyd George to coordinate Allied military strategy during World War I. It was founded in 1917, and was based in Versailles...

and appealed for large-scale Polish-Romanian military operation which would be conducted with Allied support, as well as sending Haller's divisions to Poland immediately to relieve Lviv from Ukrainian siege.

Another Allied commission, led by South African General Louis Botha

Louis Botha

Louis Botha was an Afrikaner and first Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa—the forerunner of the modern South African state...

, proposed an armistice in May that would involve the Ukrainians keeping the Drohobych oil fields and the Poles keeping Lviv. The Ukrainian side agreed to this proposal but it was rejected by the Poles on the grounds that it didn't take into consideration the overall military situation of Poland and the circumstances on the eastern front. The Bolshevik army broke through the UNR

Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic or Ukrainian National Republic was a republic that was declared in part of the territory of modern Ukraine after the Russian Revolution, eventually headed by Symon Petliura.-Revolutionary Wave:...

forces and was advancing to Podolia and Volhynia. The Poles argued that they need military control over whole Eastern Galicia to secure the Russian front in its southern part and strengthen it by a junction with Romania. The Poles launched an attack soon afterward using a large force equipped by the French (Haller's Army), which captured most of the territory of the West Ukrainian People's Republic. Urgent telegrams by the Western allies to halt this offensive were ignored. In late June 1919, the Allied Council approved the resolution allowing the Polish army (including Haller's troops) to advance through Eastern Galicia to the River Zbruch.

Czechoslovakia, which had inherited seven oil refinaries from prewar Austrian times and which was dependent on its contracts for oil with the Ukrainian government, demanded that the Poles send the Czechs the oil that had been paid for to the Ukrainian government. The Poles refused, stating that the oil was paid for with ammunition that had been used against Polish soldiers. Although the Czechs did not retaliate, according to Polish reports the Czechs considered seizing the oil fields from the Poles and returning them to the Ukrainians who would honor their contracts.

On November 21, 1919, the Highest Council of the Paris Peace Conference

Paris Peace Conference, 1919

The Paris Peace Conference was the meeting of the Allied victors following the end of World War I to set the peace terms for the defeated Central Powers following the armistices of 1918. It took place in Paris in 1919 and involved diplomats from more than 32 countries and nationalities...

granted Eastern Galicia to Poland for a period of 25 years, after which a plebiscite was to be held there. On April 21, 1920, Józef Piłsudski and Symon Petliura signed an alliance

Treaty of Warsaw (1920)

The Treaty of Warsaw of April 1920 was an alliance between the Second Polish Republic, represented by Józef Piłsudski, and the Ukrainian People's Republic, represented by Symon Petlura, against Bolshevik Russia...

, in which Poland promised the Ukrainian People's Republic

Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic or Ukrainian National Republic was a republic that was declared in part of the territory of modern Ukraine after the Russian Revolution, eventually headed by Symon Petliura.-Revolutionary Wave:...

the military help in the Kiev Offensive

Kiev Offensive

The 1920 Kiev Offensive , sometimes considered to have started the Soviet-Polish War, was an attempt by the newly re-emerged Poland, led by Józef Piłsudski, to seize central and eastern Ukraine, torn in the warring among various factions, both domestic and foreign, from Soviet control.The stated...

against the Red Army

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army started out as the Soviet Union's revolutionary communist combat groups during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1922. It grew into the national army of the Soviet Union. By the 1930s the Red Army was among the largest armies in history.The "Red Army" name refers to...

in exchange for the acceptance of Polish-Ukrainian border on the river Zbruch

Zbruch River

Zbruch River is a river in Western Ukraine, a left tributary of the Dniester.It flows within the Podolia Upland starting from the Avratinian Upland. Zbruch is the namesake of the Zbruch idol, a sculpture of a Slavic deity in the form of a column with a head with four faces, discovered in 1848 by...

.

Following this agreement, the government of the West Ukrainian National Republic

West Ukrainian National Republic

The West Ukrainian People's Republic was a short-lived republic that existed in late 1918 and early 1919 in eastern Galicia, that claimed parts of Bukovina and Carpathian Ruthenia and included the cities of Lviv , Przemyśl , Kolomyia , and Stanislaviv...

went into exile in Vienna, where it enjoyed the support of various Western Ukrainian political emigrees as well as soldiers of the Galician army interned in Bohemia. Although not officially recognized by any state as the government of western Ukraine, it engaged in diplomatic activity with the French and British governments in the hopes of obtaining a favourable settlement at Versailles. As a result of its efforts, the council of the League of Nations declared on February 23, 1921 that Galicia lay outside the territory of Poland and that Poland did not have the mandate to establish administrative control in that country, and that Poland was merely the occupying military power of eastern Galicia, whose fate would be determined by the Council of Ambassadors at the League of Nations. However, the Conference of Ambassadors

Conference of Ambassadors

The Conference of Ambassadors of the Principal Allied and Associated Powers was an inter-allied organization of the Entente in the period following the end of World War I. Formed in Paris in January 1920 it became a successor of the Supreme War Council and was later on de facto incorporated into...

in Paris stated on July 8, 1921 that so called "West Ukrainian Government" of Yevhen Petrushevych

Yevhen Petrushevych

Yevhen Petrushevych was a Ukrainian lawyer, politician, and president of the Western Ukrainian National Republic formed after the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian empire in 1918.-Biography:He was born on June 3, 1863, in the town of Busk, of Galicia in the clerical...

did not constitute a government either the facto or de jure and did not have the right to represent any of the territories formerly belonging to the Austrian empire.

After a long series of negotiations, on March 14, 1923 it was decided that eastern Galicia would be incorporated into Poland "taking into consideration that Poland has recognized that in regard to the eastern part of Galicia ethnographic conditions fully deserve its autonomous status." The government of the West Ukrainian National Republic then disbanded, while Poland reneged on its promise of autonomy for eastern Galicia.

Aftermath

Approximately 10,000 Poles and 15,000 Ukrainians, mostly soldiers, died during this war. On July 17 a ceasefireCeasefire

A ceasefire is a temporary stoppage of a war in which each side agrees with the other to suspend aggressive actions. Ceasefires may be declared as part of a formal treaty, but they have also been called as part of an informal understanding between opposing forces...

was signed. Ukrainian POWs were kept in ex-Austrian POW camps in Dąbie (Kraków), Łańcut, Pikulice

Pikulice

Pikulice is a village in the administrative district of Gmina Przemyśl, within Przemyśl County, Subcarpathian Voivodeship, in south-eastern Poland, close to the border with Ukraine. It lies approximately south of Przemyśl and south-east of the regional capital Rzeszów.-References:...

, Strzałków, and Wadowice

Wadowice

Wadowice is a town in southern Poland, 50 km from Kraków with 19,200 inhabitants , situated on the Skawa river, confluence of Vistula, in the eastern part of Silesian Plateau...

.

Following the war, the French, who had supported Poland diplomatically and militarily, obtained control over the eastern Galician oil fields under conditions that were very unfavorable to Poland.

In the beginning of Second World War

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, the area was annexed by the Soviet Union

Soviet annexation of Western Ukraine, 1939–1940

On the basis of a secret clause of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union , the Soviet Union invaded Poland on September 17, 1939, capturing the eastern regions of Poland , with Galicia and Volhynia, facing little Polish opposition and occupying the principal city of...

and attached to Ukraine, which at that time was a republic of the Soviet Union. According to the Yalta Conference

Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference, sometimes called the Crimea Conference and codenamed the Argonaut Conference, held February 4–11, 1945, was the wartime meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, represented by President Franklin D...

decisions, while Polish population of Eastern Galicia was resettled to Poland which borders were shifted westwards, the region itself remained within the Soviet Ukraine after the war and currently forms the westernmost part of now independent Ukraine

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It has an area of 603,628 km², making it the second largest contiguous country on the European continent, after Russia...

.

Legacy

Although the 70 to 75 thousand men who fought in the Ukrainian Galician ArmyUkrainian Galician Army

Ukrainian Galician Army , was the Ukrainian military of the West Ukrainian National Republic during and after the Polish-Ukrainian War. -Military equipment:...

lost their war, and their territory was annexed by Poland, the experience of proclaiming a Ukrainian state and fighting for it significantly intensified and deepened the patriotic Ukrainian orientation within Galicia. Since the interwar era, Galicia has been the center of Ukrainian nationalism

Ukrainian nationalism

Ukrainian nationalism refers to the Ukrainian version of nationalism.Although the current Ukrainian state emerged fairly recently, some historians, such as Mykhailo Hrushevskyi, Orest Subtelny and Paul Magosci have cited the medieval state of Kievan Rus' as an early precedents of specifically...

.

According to a noted interwar Polish publicist, the Polish-Ukrainian war was the principal cause for the failure to establish a Ukrainian state in Kiev in late 1918 and early 1919. During that critical time the Galician forces, large, well-disciplined and immune to Communist subversion, could have tilted the balance of power in favor of a Ukrainian state. Instead, it focused all of its resources on defending its Galician homeland. By the time the western Ukrainian forces did transfer East in the summer of 1919 after having been overwehlmed by the Poles, the Russian forces had grown significantly and the impact of the Galicians was not decisive.

After the war the Ukrainian soldiers who fought in this war became the subject of folk songs and their graves a site of annual pilgrimages in western Ukraine which persisted into Soviet times despite persecution by the Soviet authorities of those honoring the Ukrainian troops.

See also

- Battle of Lwów (1918)Battle of Lwów (1918)Battle of Lviv begun on 1 November 1918 and lasted till May 1919 and was a six months long conflict between the forces of the West Ukrainian People's Republic and local Polish civilian population assisted later by regular Polish Army forces for the control...

- Lwów EagletsLwów EagletsLwów Eaglets is a term of affection applied to the Polish teenagers who defended the city of Lviv in Eastern Galicia, during the Polish-Ukrainian War .-Background:...

- Ukrainian Galician ArmyUkrainian Galician ArmyUkrainian Galician Army , was the Ukrainian military of the West Ukrainian National Republic during and after the Polish-Ukrainian War. -Military equipment:...

- Treaty of Riga

- Komancza RepublicKomancza RepublicThe Komancza Republic was an association of 30 Lemkos villages, founded in eastern Lemkivshchyna in Komańcza on 4 November 1918. It had a Ukrainiophile orientation, and planned to unite with the West Ukrainian National Republic. It was suppressed by the Polish government on 23 January 1919 during...

- Romanian occupation of Pokucie (1919)

- Ukrainian-Soviet WarUkrainian-Soviet WarThe Ukrainian–Soviet War of 1917–21 was a military conflict between the Ukrainian People's Republic and pro-Bolshevik forces for the control of Ukraine after the dissolution of the Russian Empire.-Background:...