Rafle du Vel'd'Hiv

Encyclopedia

The Vel' d'Hiv Roundup was a major paramilitary organization under Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party. Built upon the Nazi ideology, the SS under Heinrich Himmler's command was responsible for many of the crimes against humanity during World War II...

captain who commanded the German police in France, said: "This filing system subdivided it into files alphabetically classed, Jews with French nationality and foreign Jews having files of different colours, and the files were also classed, according to profession, nationality and street." These files were then handed to section IV J of the Gestapo

Gestapo

The Gestapo was the official secret police of Nazi Germany. Beginning on 20 April 1934, it was under the administration of the SS leader Heinrich Himmler in his position as Chief of German Police...

, in charge of the "Jewish problem."

The Vel' d'Hiv roundup was not the first such roundup in World War II. Nearly 4,000 Jewish men were arrested on 10 May 1941 and taken to the Gare d'Austerlitz

Gare d'Austerlitz

Paris Austerlitz is one of the six large terminus railway stations in Paris. It is situated on the left bank of the Seine in the southeastern part of the city, in the XIIIe arrondissement...

and then to camps at Pithiviers

Pithiviers

Pithiviers is a commune in the Loiret department in north-central France. It is twinned with Ashby-de-la-Zouch in Leicestershire, England....

and Beaune-La-Rolande

Beaune-la-Rolande

Beaune-la-Rolande is a commune in the Loiret department in north-central France.On 28 November 1870 it was the site of a battle during the Franco-Prussian War, in which the noted French impressionist painter Frédéric Bazille was killed....

. Women and families followed in July 1942.

What became known as the "Vel' d'Hiv roundup" was to be more important. To plan it, René Bousquet

René Bousquet

René Bousquet was a high-ranking French civil servant, who served as secretary general to the Vichy regime police from May 1942 to 31 December 1943.-Biography:...

, secretary-general of the national police, and Louis Darquier de Pellepoix

Louis Darquier de Pellepoix

Louis Darquier, better known under his assumed name Louis Darquier de Pellepoix was Commissioner for Jewish Affairs under the Vichy Régime....

, head of the "Jewish Question", travelled on 4 July 1942 to Gestapo

Gestapo

The Gestapo was the official secret police of Nazi Germany. Beginning on 20 April 1934, it was under the administration of the SS leader Heinrich Himmler in his position as Chief of German Police...

headquarters to meet Dannecker and Helmut Knochen

Helmut Knochen

Helmut Knochen was the senior commander of the Sicherheitspolizei and Sicherheitsdienst in Paris during the Nazi occupation of France during the World War II.- Early life :...

of the SS. A further meeting took place in Dannecker's office in the avenue Foch

Avenue Foch

Avenue Foch is a street in Paris, France, named after Ferdinand Foch in 1929. It was previously named Avenue du Bois de Boulogne. It is one of the most prestigious streets in Paris, and one of the most expensive addresses in the world, home to many grand palaces, including ones belonging to the...

on 7 July. Also present were Jean Leguay

Jean Leguay

Jean Leguay was a high-ranking French civil servant complicit in the deportation of Jews from France.During the Vichy regime, Leguay was second-in-command to René Bousquet, general secretary of the National police in Paris. After the war he became president of Warner Lambert, Inc...

, Bousquet's deputy, a man called François who was director of the general police, Émile Hennequin, the head of Paris police, André Tulard, and others from the French police.

Dannecker met Adolf Eichmann

Adolf Eichmann

Adolf Otto Eichmann was a German Nazi and SS-Obersturmbannführer and one of the major organizers of the Holocaust...

on 10 July 1942, and another meeting took place the same day at the General Commission for the Jewish Question (CGQJ) attended by Dannecker, Heinz Röthke, Ernst Heinrichsohn, Jean Leguay, Gallien, deputy to Darquier de Pellepoix (head of the CGQJ), several police officials and representatives of the French railway service, the SNCF

SNCF

The SNCF , is France's national state-owned railway company. SNCF operates the country's national rail services, including the TGV, France's high-speed rail network...

. The roundup was delayed because the Germans wanted to avoid holding it before Bastille Day

Bastille Day

Bastille Day is the name given in English-speaking countries to the French National Day, which is celebrated on 14 July of each year. In France, it is formally called La Fête Nationale and commonly le quatorze juillet...

on 14 July. The national holiday was not celebrated in the occupied zone but there was a wish to avoid civil uprisings.

Dannecker declared: "The French police, apart from [malgré] a few considerations of pure form, have only to carry out orders!"

The roundup was aimed at Jews from Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

, Austria

Austria

Austria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

, Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

, Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

, the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

and those whose origins couldn't be determined, all aged from 16 to 50. There were to be exceptions for women "in advanced state of pregnancy" or who were breast-feeding, but "to save time, the sorting will be made not at home but at the first assembly centre".

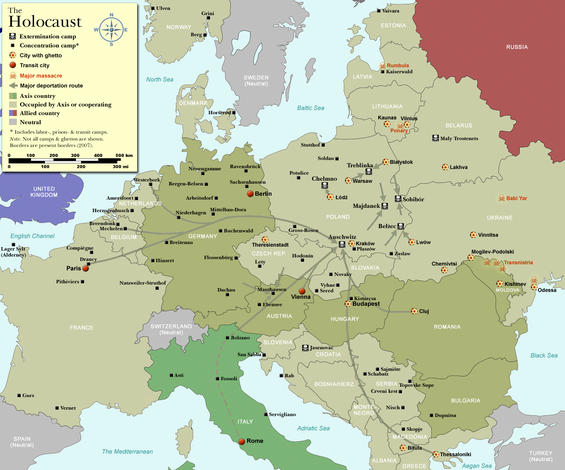

The Germans planned for the French police to arrest 22,000 Jews in Greater Paris. The Jews would then be taken to internment camps at Drancy

Drancy internment camp

The Drancy internment camp of Paris, France, was used to hold Jews who were later deported to the extermination camps. 65,000 Jews were deported from Drancy, of whom 63,000 were murdered including 6,000 children...

, Compiègne

Compiègne

Compiègne is a city in northern France. It is designated municipally as a commune within the département of Oise.The city is located along the Oise River...

, Pithiviers

Pithiviers

Pithiviers is a commune in the Loiret department in north-central France. It is twinned with Ashby-de-la-Zouch in Leicestershire, England....

and Beaune-la-Rolande

Beaune-la-Rolande

Beaune-la-Rolande is a commune in the Loiret department in north-central France.On 28 November 1870 it was the site of a battle during the Franco-Prussian War, in which the noted French impressionist painter Frédéric Bazille was killed....

. André Tulard "will obtain from the head of the municipal police the files of Jews to be arrested... Children of less than 15 or 16 years will be sent to the Union Générale des Israélites de France, which will place them in foundations. The sorting of children will be done in the first assembly centres."

Police complicity

The position of the French police was complicated by the sovereignty of the Vichy governmentVichy France

Vichy France, Vichy Regime, or Vichy Government, are common terms used to describe the government of France that collaborated with the Axis powers from July 1940 to August 1944. This government succeeded the Third Republic and preceded the Provisional Government of the French Republic...

, which nominally administered France while accepting occupation of the north. Although in practice the Germans ran the north and had a strong and later total domination in the south, the formal position was that France and the Germans were separate. The position of Vichy and its leader, Philippe Pétain

Philippe Pétain

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Joseph Pétain , generally known as Philippe Pétain or Marshal Pétain , was a French general who reached the distinction of Marshal of France, and was later Chief of State of Vichy France , from 1940 to 1944...

, was recognised throughout the war by many foreign governments.

The independence, however fictional, had to be preserved. German interference in internal policing, says the historian Julian T. Jackson

Julian T. Jackson

Julian T. Jackson is a prominent British historian. He is a Fellow of the British Academy and of the Royal Historical Society. Professor of History at Queen Mary, University of London Julian Jackson is one of the leading authorities on twentieth-century France.He was educated at the University of...

, "would further erode that sovereignty which Vichy was so committed to preserving. This could only be avoided by reassuring Germany that the French would carry out the necessary measures."

On 2 July 1942, René Bousquet

René Bousquet

René Bousquet was a high-ranking French civil servant, who served as secretary general to the Vichy regime police from May 1942 to 31 December 1943.-Biography:...

attended a planning meeting in which he raised no objection to the arrests and worried only about the "embarrassing [gênant]" fact that the French police would carry them out. Bousquet succeeded in a compromise that the police would round up only foreign Jews. Vichy ratified that agreement the following day.

Although the police have been blamed for rounding up children of less than 16 – the age was set to preserve a fiction that workers were needed in the east – the order was given by Pétain's minister, Pierre Laval

Pierre Laval

Pierre Laval was a French politician. He was four times President of the council of ministers of the Third Republic, twice consecutively. Following France's Armistice with Germany in 1940, he served twice in the Vichy Regime as head of government, signing orders permitting the deportation of...

, supposedly as a "humanitarian" measure to keep families together. This too was a fiction, given that the parents of these children had already been deported, and documents of the period have revealed that the anti-semitic Laval's principal concern was what to do with Jewish children once their parents had been deported. The youngest child sent to Auschwitz under Laval's orders was 18 months old.

Three former SS officers testified in 1980 that Vichy officials had been enthusiastic about deportation of Jews from France. The investigator Serge Klarsfeld found minutes in German archives of meetings with senior Vichy officials and Bousquet's proposal that the roundup should cover non-French Jews throughout the country.

The historians Antony Beevor

Antony Beevor

Antony James Beevor, FRSL is a British historian, educated at Winchester College and Sandhurst. He studied under the famous military historian John Keegan. Beevor is a former officer with the 11th Hussars who served in England and Germany for five years before resigning his commission...

and Artemis Cooper

Artemis Cooper

The Hon. Alice Clare Antonia Opportune Cooper Beevor is a British writer known as Artemis Cooper.Known as Artemis, a nickname which honours her paternal grandmother, she is the only daughter of the 2nd Viscount Norwich and his first wife, the former Anne Clifford, and a granddaughter of the...

record:

- "Klarsfeld also revealed the telegrams Bousquet had sent to Prefects of départements in the occupied zone, ordering them to deport not only Jewish adults but children whose deportation had not even been requested by the Nazis."

The roundup

Émile Hennequin, director of the city police, ordered on 12 July 1942 that "the operations must be effected with the maximum speed, without pointless speaking and without comment."Beginning at 4:00 a.m. on 16 July 1942, 13,152 Jews were arrested according to records of the Préfecture de police, of which 5,802 (44%) were women and 4,051 (31%) were children. An unknown number of people, warned by the French Resistance

French Resistance

The French Resistance is the name used to denote the collection of French resistance movements that fought against the Nazi German occupation of France and against the collaborationist Vichy régime during World War II...

or hidden by neighbors or benefiting from a lack of zeal, deliberate or accidental, of some policemen, escaped being rounded up. Conditions for the arrested were harsh: they could take only a blanket, a sweater, a pair of shoes and two shirts with them. Most families were split up and never reunited.

After arrest, some Jews were taken by bus to an internment camp in an incomplete complex of apartments and apartment towers in the northern suburb of Drancy

Drancy internment camp

The Drancy internment camp of Paris, France, was used to hold Jews who were later deported to the extermination camps. 65,000 Jews were deported from Drancy, of whom 63,000 were murdered including 6,000 children...

. Others were taken to the Vélodrome d'hiver

Vélodrome d'hiver

The Vélodrome d'Hiver , colloquially Vel' d'Hiv, was an indoor bicycle racing cycle track and stadium on rue Nélaton, not far from the Eiffel Tower in Paris. As well as track cycling, it was used for ice hockey, wrestling, boxing, roller-skating, circuses, spectaculars, and demonstrations...

in the 15th arrondissement

Arrondissement

Arrondissement is any of various administrative divisions of France, certain other Francophone countries, and the Netherlands.-France:The 101 French departments are divided into 342 arrondissements, which may be translated into English as districts. The capital of an arrondissement is called a...

, which had already been used as a prison in a roundup in the summer of 1941.

The Vel' d'Hiv

The Vel' d'Hiv was available for hire to whoever wanted it. Among those who had booked was Jacques DoriotJacques Doriot

Jacques Doriot was a French politician prior to and during World War II. He began as a Communist but then turned Fascist.-Early life and politics:...

, a stocky, round-faced man who led France's largest fascist party, the PPF. It was at the Vel' d'Hiv among other venues that Doriot, with his Hitler-like salute, roused crowds to join his cause. Among those who helped in the Rafle du Vel' d'hiv were 3,400 young members of Doriot's PPF.

The Germans demanded the keys of the Vel' d'Hiv from its owner, Jacques Goddet

Jacques Goddet

Jacques Goddet was a French sports journalist and director of the Tour de France from 1936 to 1986....

, who had taken over from his father Victor and from Henri Desgrange. The circumstances in which Goddet surrendered the keys remain a mystery and the episode is given only a few lines in his autobiography.

The Vel' d'Hiv had a glass roof, which had been painted dark blue to avoid attracting bomber navigators. The glass raised the heat when combined with windows screwed shut for security. The numbers held there vary according to accounts but one established figure is 7,500 of a final figure of 13,152. They had no lavatories: of the 10 available, five were sealed because their windows offered a way out and the others were blocked. The arrested Jews were kept there with only water and food brought by Quakers, the Red Cross and a few doctors and nurses allowed to enter. There was only one water tap. Those who tried to escape were shot on the spot. Some took their own lives.

After five days, the prisoners were taken to the internment camps of Drancy, Beaune-la-Rolande and Pithiviers, and later to extermination camps.

After the roundup

Roundups were conducted in both the northern and southern zones of France, but public outrage was greatest in Paris because of the numbers involved in a concentrated area. The Vel' d'Hiv was a landmark in the city centre. The Roman Catholic church was among the protesters. Public reaction obliged Laval to ask the Germans on 2 September not to demand more Jews. Handing them over, he said, was not like buying items in a discount store. Laval managed to limit deportations mainly to foreign Jews and he and his defenders argued after the war that allowing the French police to conduct the roundup had been a bargain to ensure the life of Jews of French nationality.In reality, "Vichy shed no tears over the fate of the foreign Jews in France, who were seen as a nuisance, 'dregs (déchets)' in Laval's words. Laval told an American diplomat that he was "happy" to get rid of them.

When a Protestant leader accused Laval of murdering Jews, Laval insisted they had been sent to build an agricultural colony in the East. "I talked to him about murder, he answered me with gardening."

Drancy camp and deportation

Drancy internment camp

The Drancy internment camp of Paris, France, was used to hold Jews who were later deported to the extermination camps. 65,000 Jews were deported from Drancy, of whom 63,000 were murdered including 6,000 children...

– which is now the subsidised housing that it was intended to be – was easily defended because it was built of tower blocks in the shape of a horseshoe. It was guarded by French gendarmes. The camp's operation was under the Gestapo's section of Jewish affairs. Theodor Dannecker

Theodor Dannecker

Theodor Dannecker was an SS Hauptsturmführer and one of Adolf Eichmann's associates....

, a key figure both in the roundup and in the operation of Drancy, was described by Maurice Rajsfus in his history of the camp as "a violent psychopath... It was he who ordered the internees to starve, who banned them from moving about within the camp, to smoke, to play cards etc."

In December 1941, forty prisoners from Drancy were executed in retaliation for a French attack on German police officers.

Immediate control of the camp was by Heinz Röthke. It was under his direction from August 1942 to June 1943 that almost two-thirds of those deported in SNCF box car transports requisitioned by the Nazis from Drancy were sent to Auschwitz. Drancy is also the location where Klaus Barbie

Klaus Barbie

Nikolaus 'Klaus' Barbie was an SS-Hauptsturmführer , Gestapo member and war criminal. He was known as the Butcher of Lyon.- Early life :...

transported Jewish children that he captured in a raid of a children's home, before shipping them to Auschwitz where they were killed. Most of the initial victims, including those of the Vel' d'Hiv, were crammed in sealed wagons and died enroute due to lack of food and water. Those who survived the passage died in the gas chambers.

At the Liberation in 1944, the camp was run by the Resistance

French Resistance

The French Resistance is the name used to denote the collection of French resistance movements that fought against the Nazi German occupation of France and against the collaborationist Vichy régime during World War II...

– "to the frustration of the authorities; the Prefect of Police had no control at all and visitors were not welcome." – which used it to house not Jews but those it considered had collaborated with the Germans. When a pastor was allowed in on 15 September, he discovered cells 3.5m by 1.75m that had held six Jewish internees with two mattresses between them. The prison returned to the conventional prison service on 20 September.

Aftermath

The roundup accounted for more than a quarter of the Jews sent from France to Auschwitz in 1942, of whom only 811 returned to France at the end of the war.Pierre Laval

Pierre Laval

Pierre Laval was a French politician. He was four times President of the council of ministers of the Third Republic, twice consecutively. Following France's Armistice with Germany in 1940, he served twice in the Vichy Regime as head of government, signing orders permitting the deportation of...

's trial opened on 3 October 1945, his first defence being that he had been obliged to sacrifice foreign Jews to save the French. Uproar broke out in the court, with supposedly neutral jurors shouting abuse at Laval, threatening "a dozen bullets in his hide". It was, said the historians Antony Beevor and Artemis Cooper, "a cross between an auto-de-fé and a tribunal during the Paris Terror

Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror , also known simply as The Terror , was a period of violence that occurred after the onset of the French Revolution, incited by conflict between rival political factions, the Girondins and the Jacobins, and marked by mass executions of "enemies of...

. From 6 October, Laval refused to take part in the proceedings, hoping that the jurors' interventions would lead to a new trial. Laval was sentenced to death, and tried to commit suicide by swallowing a cyanide capsule. Revived by doctors, he was executed by firing squad on 15 October 1945. at Fresnes on 15 October.

Jean Leguay

Jean Leguay

Jean Leguay was a high-ranking French civil servant complicit in the deportation of Jews from France.During the Vichy regime, Leguay was second-in-command to René Bousquet, general secretary of the National police in Paris. After the war he became president of Warner Lambert, Inc...

survived the war and its aftermath and became president of Warner Lambert, Inc. from London (now merged with Pfizer), and later president of Substantia Laboratories in Paris. In 1979, he was accused in connection with the roundup but killed himself before his trial.

Louis Darquier was sentenced to death in absentia

In absentia

In absentia is Latin for "in the absence". In legal use, it usually means a trial at which the defendant is not physically present. The phrase is not ordinarily a mere observation, but suggests recognition of violation to a defendant's right to be present in court proceedings in a criminal trial.In...

in 1947 for collaboration. However, he had fled to Spain, where the Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco y Bahamonde was a Spanish general, dictator and head of state of Spain from October 1936 , and de facto regent of the nominally restored Kingdom of Spain from 1947 until his death in November, 1975...

regime protected him. France never asked for his extradition. He died on 29 August 1980, near Málaga

Málaga

Málaga is a city and a municipality in the Autonomous Community of Andalusia, Spain. With a population of 568,507 in 2010, it is the second most populous city of Andalusia and the sixth largest in Spain. This is the southernmost large city in Europe...

, Spain.

Helmut Knochen

Helmut Knochen

Helmut Knochen was the senior commander of the Sicherheitspolizei and Sicherheitsdienst in Paris during the Nazi occupation of France during the World War II.- Early life :...

was sentenced to death by a British Military Tribunal in 1946 for the murder of British pilots. The sentence was never carried out. He was extradited to France in 1954 and again sentenced to death. The sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment. In 1962, the president, Charles de Gaulle

Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle was a French general and statesman who led the Free French Forces during World War II. He later founded the French Fifth Republic in 1958 and served as its first President from 1959 to 1969....

, pardon

Pardon

Clemency means the forgiveness of a crime or the cancellation of the penalty associated with it. It is a general concept that encompasses several related procedures: pardoning, commutation, remission and reprieves...

ed him and he was sent back to Germany, where he retired to Baden-Baden

Baden-Baden

Baden-Baden is a spa town in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is located on the western foothills of the Black Forest, on the banks of the Oos River, in the region of Karlsruhe...

and died in 2003.

Émile Hennequin, head of Paris police, was condemned to eight years' penal labour in June 1947.

René Bousquet

René Bousquet

René Bousquet was a high-ranking French civil servant, who served as secretary general to the Vichy regime police from May 1942 to 31 December 1943.-Biography:...

was last to be tried, in 1949. He was acquitted of "compromising the interests of the national defence", but declared guilty of for involvement in the Vichy government. He was given five years of Dégradation nationale

Dégradation nationale

The dégradation nationale was a sentence introduced in France after the Liberation. It was applied during the épuration légale which followed the fall of the Vichy regime....

, a measure immediately lifted for "having actively and sustainably participated in the resistance against the occupier". Bousquet's position was always ambiguous; there were times he worked with the Germans and others when he worked against them. After the war he worked at the Banque d'Indochine and in newspapers.

In 1957, the Conseil d'État gave back his Legion of Honour, and he was given an amnesty on 17 January 1958, after which he stood for election that same year as a candidate for the Marne

Marne

Marne is a department in north-eastern France named after the river Marne which flows through the department. The prefecture of Marne is Châlons-en-Champagne...

. He was supported by the Democratic and Socialist Union of the Resistance

Democratic and Socialist Union of the Resistance

The Democratic and Socialist Union of the Resistance was a French political party found at the Liberation and in activity during the Fourth Republic...

; his second was Hector Bouilly, a radical-socialist general councillor. In 1974, Bousquet helped finance François Mitterrand

François Mitterrand

François Maurice Adrien Marie Mitterrand was the 21st President of the French Republic and ex officio Co-Prince of Andorra, serving from 1981 until 1995. He is the longest-serving President of France and, as leader of the Socialist Party, the only figure from the left so far elected President...

's presidential campaign against Valéry Giscard d'Estaing

Valéry Giscard d'Estaing

Valéry Marie René Georges Giscard d'Estaing is a French centre-right politician who was President of the French Republic from 1974 until 1981...

. In 1986, as accusations cast on Bousquet grew more credible, particularly after he was named by Louis Darquier, he and Mitterrand stopped seeing each other. The parquet général de Paris

Parquet (legal)

The parquet is the office of the prosecution, in some countries, responsible for presenting legal cases at criminal trials against individuals or parties suspected of breaking the law....

closed the case by sending it to a court that no longer existed. Lawyers for the International Federation of Human Rights

International Federation of Human Rights

The International Federation for Human Rights is a non-governmental federation for human rights organizations. Founded in 1922, FIDH is the oldest international human rights organisation worldwide and today brings together 164 member organisations in over 100 countries.FIDH is nonpartisan,...

spoke of a "political decision at the highest levels to prevent the Bousquet affair from developing". In 1989, Serge Klarsfeld and his , the and the filed a complaint against Bousquet for Crime against humanity

Crime against humanity

Crimes against humanity, as defined by the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court Explanatory Memorandum, "are particularly odious offenses in that they constitute a serious attack on human dignity or grave humiliation or a degradation of one or more human beings...

, for the deportation of 194 children. Bousquet was committed to trial but on 8 June 1993 a 55-year-old mental patient named Christian Didier entered his flat and shot him dead.

Theodor Dannecker

Theodor Dannecker

Theodor Dannecker was an SS Hauptsturmführer and one of Adolf Eichmann's associates....

was interned by the United States Army

United States Army

The United States Army is the main branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for land-based military operations. It is the largest and oldest established branch of the U.S. military, and is one of seven U.S. uniformed services...

in December 1945 and a few days later committed suicide

Suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Suicide is often committed out of despair or attributed to some underlying mental disorder, such as depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, alcoholism, or drug abuse...

.

Jacques Doriot

Jacques Doriot

Jacques Doriot was a French politician prior to and during World War II. He began as a Communist but then turned Fascist.-Early life and politics:...

, whose French right-wing followers helped in the round-up, fled to Sigmaringen

Sigmaringen

Sigmaringen is a town in southern Germany, in the state of Baden-Württemberg. Situated on the upper Danube, it is the capital of the Sigmaringen district....

, Germany, and became a member of the exile Vichy government there. He died in February 1945 when his car was strafed by Allied

Allies of World War II

The Allies of World War II were the countries that opposed the Axis powers during the Second World War . Former Axis states contributing to the Allied victory are not considered Allied states...

fighters while he was travelling from Mainau

Mainau

Mainau is an island in Lake Constance . It is maintained as a garden island and a model of excellent environmental practices...

to Sigmaringen. He was buried in Mengen.

Action against the police

The court ruled on 22 March 1947, that the seven were found guilty but that most had rehabilitated themselves "by active participation, useful and sustained, offered to the Resistance against the enemy." Two others were jailed for two years and condemned to dégradation nationale

Dégradation nationale

The dégradation nationale was a sentence introduced in France after the Liberation. It was applied during the épuration légale which followed the fall of the Vichy regime....

for five years. A year later they were reprieved.

Apology

For decades the French government declined to apologise for the role of French policemen in the roundup or for any other state complicity. It was argued that the French Republic had been dismantled when Philippe PétainPhilippe Pétain

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Joseph Pétain , generally known as Philippe Pétain or Marshal Pétain , was a French general who reached the distinction of Marshal of France, and was later Chief of State of Vichy France , from 1940 to 1944...

instituted a new French State during the war and that the Republic had been re-established when the war was over. It was not for the Republic, therefore, to apologise for events that happened while it had not existed and which had been carried out by a state which it did not recognise.

On 16 July 1995, the President, Jacques Chirac

Jacques Chirac

Jacques René Chirac is a French politician who served as President of France from 1995 to 2007. He previously served as Prime Minister of France from 1974 to 1976 and from 1986 to 1988 , and as Mayor of Paris from 1977 to 1995.After completing his studies of the DEA's degree at the...

, ruled it was time that France faced up to its past and he acknowledged the role that the state had played in the persecution of Jews and other victims of the German occupation. He said:

- "These black hours will stain our history for ever and are an injury to our past and our traditions. Yes, the criminal madness of the occupant was assisted('secondée') by the French, by the French state. Fifty-three years ago, on 16 July 1942, 450 policemen and gendarmes, French, under the authority of their leaders, obeyed the demands of the Nazis. That day, in the capital and the Paris region, nearly 10,000 Jewish men, women and children were arrested at home, in the early hours of the morning, and assembled at police stations... France, home of the EnlightenmentAge of EnlightenmentThe Age of Enlightenment was an elite cultural movement of intellectuals in 18th century Europe that sought to mobilize the power of reason in order to reform society and advance knowledge. It promoted intellectual interchange and opposed intolerance and abuses in church and state...

and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the CitizenDeclaration of the Rights of Man and of the CitizenThe Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen is a fundamental document of the French Revolution, defining the individual and collective rights of all the estates of the realm as universal. Influenced by the doctrine of "natural right", the rights of man are held to be universal: valid...

, land of welcome and asylum, France committed that day the irreparable. Breaking its word, it delivered those it protected to their executioners."

Memorials and monuments – Paris

A fire destroyed part of the Vélodrome d'Hiver in 1959 and the rest was demolished. A block of flats and a building belonging to the Ministry of the Interior now stand on the site. A plaque marking the Vel' d'Hiv Roundup was placed on the track building and moved to 8 boulevard de Grenelle in 1959. On 3 February 1993, the President, François MitterrandFrançois Mitterrand

François Maurice Adrien Marie Mitterrand was the 21st President of the French Republic and ex officio Co-Prince of Andorra, serving from 1981 until 1995. He is the longest-serving President of France and, as leader of the Socialist Party, the only figure from the left so far elected President...

, commissioned a monument to be erected on the site.

It stands now on a curved base, to represent the cycle track, on the edge of the quai de Grenelle. It is the work of the Polish sculptor Walter Spitzer and the architect Mario Azagury. Spitzer's family were survivors of deportation to Auschwitz. The statue represents all deportees but especially those of the Vel' d'Hiv. The sculpture includes children, a pregnant woman and a sick man. The words on the monument are: "The French Republic in homage to victims of racist and antisemitic persecutions and of crimes against humanity committed under the authority of the so-called 'Government of the State of France.'"

The statue was inaugurated on 17 July 1994. A ceremony is held there every year and it was during a ceremony that Jacques Chirac, successor to François Mitterrand, made his remarks, in 1995, about the guilt of the French police and gendarmerie in collaborating with the Germans. The statue was placed on land given by the city of Paris and paid for by the Ministère des Anciens Combattants (Veterans Administration [Am], Old Soldiers [Br]). The statue is cared for by the Defence Ministry.

A memorial plaque in memory of victims of the Vel' d'Hiv raid was placed at the Bir-Hakeim station

Bir-Hakeim (Paris Metro)

Bir-Hakeim is an elevated station of the Paris Métro serving line 6 in the Boulevard de Grenelle in the 15th arrondissement. It is situated on the left bank of the Bir-Hakeim bridge over the Seine....

of the Paris Métro

Paris Métro

The Paris Métro or Métropolitain is the rapid transit metro system in Paris, France. It has become a symbol of the city, noted for its density within the city limits and its uniform architecture influenced by Art Nouveau. The network's sixteen lines are mostly underground and run to 214 km ...

on 20 July 2008. The ceremony was led by Jean-Marie Bockel, Secretary of Defense and Veterans Affairs, and was attended by Simone Veil

Simone Veil

Simone Veil, DBE is a French lawyer and politician who served as Minister of Health under Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, President of the European Parliament and member of the Constitutional Council of France....

, a deportee and former minister, anti-Nazi activist Beate Klarsfeld, and numerous dignitaries.

The Shoah Memorial (Mémorial de la Shoah), located at 17 rue Geoffroy l'Asnier in the Marais district of Paris, holds significant documentation and photographs in its archives for researchers. Exhibits about the Holocaust in France and the "Vel' d'Hiv Roundup" on display in the memorial's museum are open to the public.

Memorials and monuments – Drancy

A memorial was also constructed in 1976 at DrancyDrancy

Drancy is a commune in the northeastern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located 10.8 km from the center of Paris.- Toponomy :...

, after a design competition won by Shelomo Selinger. It stands beside a rail wagon of the sort used to take prisoners to the death camps. It is three blocks forming the Hebrew letter Shin

Shin (letter)

Shin literally means "Sharp" ; It is the twenty-first letter in many Semitic abjads, including Phoenician , Aramaic/Hebrew , and Arabic ....

, traditionally written on the Mezuzah

Mezuzah

A mezuzah is usually a metal or wooden rectangular object that is fastened to a doorpost of a Jewish house. Inside it is a piece of parchment inscribed with specified Hebrew verses from the Torah...

at the door of houses occupied by Jews. Two other blocks represent the gates of death. Shelomo Selinger said of his work: "The central block is composed of 10 figures, the number needed for collective prayer (Minyan

Minyan

A minyan in Judaism refers to the quorum of ten Jewish adults required for certain religious obligations. According to many non-Orthodox streams of Judaism adult females count in the minyan....

). The two Hebrew letters Lamed and Vav

Vav

VAV as a three-letter abbreviation may refer to* A Volcanic Ash Victim meaning someone who has been left stranded by a volcanic ash cloud that is hindering air travel.* A variable air volume device, used in HVAC systems to control the flow of air...

are formed by the hair, the arm and the beard of two people at the top of the sculpture. These letters have the numeric 36, the number of Righteous thanks to whom the world exists according to Jewish tradition."

On 25 May 2001, the cité de la Muette – formal name of the Drancy apartment blocks – was declared a national monument by the culture minister, Catherine Tasca

Catherine Tasca

Catherine Tasca is a member of the Senate of France, representing the Yvelines department. She is a member of the Socialist Party; she currently serves as the Senate's vice-president. From 2000 to 2002 she was Minister of Culture in France. She is the daughter of Angelo Tasca a former italian...

.

The Holocaust researcher Serge Klarsfeld said in 2004: "Drancy is the best known place for everyone of the memory of the Shoah

Shoah

Shoah may refer to:*The Holocaust*Shoah , documentary directed by Claude Lanzmann * A Shoah Foundation...

in France; in the crypt of Yad Vashem

Yad Vashem

Yad Vashem is Israel's official memorial to the Jewish victims of the Holocaust, established in 1953 through the Yad Vashem Law passed by the Knesset, Israel's parliament....

(Jérusalem

Jérusalem

Jérusalem is a grand opera in four acts by Giuseppe Verdi, set to a French libretto by Alphonse Royer and Gustave Vaëz which was partly translated and adapted from Verdi's original 1843 Italian opera, I Lombardi alla prima crociata...

), where stones are engraved with the names of the most notorious Jewish concentration and extermination camps, Drancy is the only place of memory in France to feature."

Significance

The primary significance of the roundup was the killing of innocent people because of their religion. But there is a political and social significance because the Vel' d'Hiv has remained a symbol of national guilt and of national outrage.The wartime history of France differed from that of other occupied nations in that the country was socially and politically divided, until it was all finally occupied by the Germans after being divided into an occupied and non-occupied zone. The pre-war Republic disintegrated after the invasion and France looked for, and in the first-war hero Philippe Pétain found, a figurehead to give it hope.

Pétain established a government at Vichy

Vichy France

Vichy France, Vichy Regime, or Vichy Government, are common terms used to describe the government of France that collaborated with the Axis powers from July 1940 to August 1944. This government succeeded the Third Republic and preceded the Provisional Government of the French Republic...

– because it had more hotels and better telephones than elsewhere – and he nominally ran the new French State in both the occupied and unoccupied zones. France became a neutral nation in fact however flimsy that status was in practice.

As the historian Julian Jackson points out, Pétain tried to maintain the independence of France and to stop its police force, among other organs of state, from becoming auxiliaries of the Germans. But if he did not agree to what the Germans demanded, as with the Vel' d'Hiv, the Germans would either do it themselves or take away command of the police. Pétain was left in the position of having the police do whatever the Germans wanted of them as a way of preserving their own supposed independence.

The guilt comes not only through this co-operation, if not outright collaboration, but through the zeal with which parts of the police force worked with the Germans. While some policemen tipped off Jews so they could escape, others were tried – if they didn't flee first – for their brutality. French policemen ensured their neighbours stayed behind bars, ready to be taken to their death, only because they were of a different religion.

The Vel' d'Hiv has remained a symbol of a wider disquiet, at the broadest level because of the Pétain government which France at first welcomed and then saw deteriorate into an organ of the occupation – often enthusiastically – and on a narrower level by individuals who profited from the occupation and furthered its cause or didn't raise what in retrospect seemed enough objection.

There were heroes of the Occupation and there were those who faced death through dishonour. In between were the millions who got on with their lives without the benefit of knowing how the war would turn out. It is they, examining their consciences and wondering whether they could have done more, who find the Vel' d'Hiv a disturbing symbol of what Julian Jackson calls The Dark Years.

Primary sources

- Instructions given by chief of police Hennequin for the raid.

Film documentaries and books

- William KarelWilliam KarelWilliam Karel is a French film director and author. He is known for his historical and political documentaries.- Biography :After studying in Paris, Karel emigrated to Israel where he lived for about 10 years in a kibbutz...

, 1992. La Rafle du Vel-d'Hiv, La Marche du siècle, France 3France 3France 3 is the second largest French public television channel and part of the France Télévisions group, which also includes France 2, France 4, France 5, and France Ô....

. - Tatiana de RosnayTatiana de RosnayTatiana de Rosnay, born on September 28, 1961 in Neuilly-sur-Seine, is a French Journalist, writer and screenwriter.-Biography:Tatiana de Rosnay was born on September 28th, 1961 in the suburbs of Paris. She is of English, French and Russian descent. Her father is French scientist Joël de Rosnay,...

, Sarah's KeySarah's KeySarah's Key is a French drama starring Kristin Scott-Thomas and follows an American journalist's present-day investigation into the Vel' d'Hiv Roundup Sarah's Key is a French drama starring Kristin Scott-Thomas and follows an American journalist's present-day investigation into the Vel' d'Hiv...

, book: St. Martin's Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0312370831 (also 2010 film)

The events form the framework of:

- Monsieur KleinMonsieur KleinMonsieur Klein is a 1976 French film directed by Joseph Losey, with Alain Delon starring in the title role.- Synopsis :It is 1942, the war is in full swing and France is occupied by the Nazis. To Robert Klein, however, these events are of little concern...

, 1976. French film directed by Joseph LoseyJoseph LoseyJoseph Walton Losey was an American theater and film director. After studying in Germany with Bertolt Brecht, Losey returned to the United States, eventually making his way to Hollywood...

, much of which was shot on location. The film won the 1977 César Awards in the categories of Best Film, Best Director, and Best Production Design. - The Round UpThe Round Up (film)The Round Up is a 2010 French film directed by Roselyne Bosch and produced by Alain Goldman. The film stars Mélanie Laurent, Jean Reno, Sylvie Testud and Gad Elmaleh...

, 2010. French film directed by Roselyne Bosch and produced by Alain Goldman - Sarah's KeySarah's KeySarah's Key is a French drama starring Kristin Scott-Thomas and follows an American journalist's present-day investigation into the Vel' d'Hiv Roundup Sarah's Key is a French drama starring Kristin Scott-Thomas and follows an American journalist's present-day investigation into the Vel' d'Hiv...

, 2010. French film directed by Gilles Paquet-Brenner and produced by Stéphane Marsil.

External links

- Online Encyclopedia of Mass Violence: Case Study: The Vélodrome d'Hiver Round-up: July 16 and 17, 1942

- Le monument commémoratif du quai de Grenelle à Paris

- Le site de la memoire des conflits contemporains en région parisienne

- Occupied France: Commemorating the Deportation

- additional photographs

- French government booklet

- 1995 speech of President Chirac