Reform Act 1867

Encyclopedia

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

and Wales

Wales

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and the island of Great Britain, bordered by England to its east and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population of three million, and a total area of 20,779 km²...

.

Before the Act, only one million of the five million adult males in England and Wales could vote; the act doubled that number. In its final form, the Reform Act of 1867 enfranchised all male householders and compounding was also subsequently abolished in the process. However, there was little redistribution of seats; and what there was had been intended to help the Conservative Party

Conservative Party (UK)

The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

.

Background

For many years after the Great Reform Act of 1832Reform Act 1832

The Representation of the People Act 1832 was an Act of Parliament that introduced wide-ranging changes to the electoral system of England and Wales...

, governments had resisted attempts to push through further reform, and in particular in rejecting the claims of the Chartist

Chartism

Chartism was a movement for political and social reform in the United Kingdom during the mid-19th century, between 1838 and 1859. It takes its name from the People's Charter of 1838. Chartism was possibly the first mass working class labour movement in the world...

movement. After 1848, this movement declined rapidly , and elite opinion began to change . It was quite a number of years later that it was thought prudent to introduce further electoral reform. Lord John Russell

John Russell, 1st Earl Russell

John Russell, 1st Earl Russell, KG, GCMG, PC , known as Lord John Russell before 1861, was an English Whig and Liberal politician who served twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in the mid-19th century....

attempted this in 1860, but the Prime Minister Lord Palmerston

Henry Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, KG, GCB, PC , known popularly as Lord Palmerston, was a British statesman who served twice as Prime Minister in the mid-19th century...

was against any further electoral reform. When Palmerston died in 1865, however, the floodgates for reform were opened.

The Union victory in the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

in 1865 emboldened the forces in Britain that demanded more democracy and public input into the political system, to the dismay of the upper class landed gentry who identified more with the Southern planters and feared this might happen. Influential commentators included Walter Bagehot

Walter Bagehot

Walter Bagehot was an English businessman, essayist, and journalist who wrote extensively about literature, government, and economic affairs.-Early years:...

, Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle was a Scottish satirical writer, essayist, historian and teacher during the Victorian era.He called economics "the dismal science", wrote articles for the Edinburgh Encyclopedia, and became a controversial social commentator.Coming from a strict Calvinist family, Carlyle was...

, John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill was a British philosopher, economist and civil servant. An influential contributor to social theory, political theory, and political economy, his conception of liberty justified the freedom of the individual in opposition to unlimited state control. He was a proponent of...

, and Anthony Trollope

Anthony Trollope

Anthony Trollope was one of the most successful, prolific and respected English novelists of the Victorian era. Some of his best-loved works, collectively known as the Chronicles of Barsetshire, revolve around the imaginary county of Barsetshire...

.

In 1866, Prime Minister Earl Russell (as he became) introduced a Reform Bill. It was a cautious measure, which proposed to enfranchise "respectable" working men, excluding unskilled workers and what was known as the "residuum," that is, seen by MPs as the "feckless and criminal" poor. This was ensured by a £7 householder qualification, which had been calculated to require an income of 26 shillings a week (£765.00 in 2011). There were also two "fancy franchises," originating from measures of 1854, a £10 lodger qualification for the boroughs, and a £50 savings qualification in the counties. Liberals claimed that 'the middle classes, strengthened by the best of the artisans, would still have the preponderance of power'.

When it came to the vote, however, this bill split the Liberal Party

Liberal Party (UK)

The Liberal Party was one of the two major political parties of the United Kingdom during the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a third party of negligible importance throughout the latter half of the 20th Century, before merging with the Social Democratic Party in 1988 to form the present day...

: this was partly engineered by Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, KG, PC, FRS, was a British Prime Minister, parliamentarian, Conservative statesman and literary figure. Starting from comparatively humble origins, he served in government for three decades, twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom...

, who incited those threatened by the bill to rise up against it. On one side were the reactionary-conservative Liberals, known as the Adullamites

Adullamites

The Adullamites were a short-lived anti-reform faction within the UK Liberal Party in 1866. The name is based on a biblical reference to the cave of Adullam where David and his allies sought refuge from Saul....

; on the other were pro-reform Liberals who supported the Government. The Adullamites, though, were supported by Tories and the liberal Whigs were supported by radicals and reformists.

The bill was thus defeated and the Liberal government of Russell resigned.

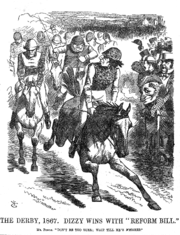

Birth of the Act

The Conservatives formed a ministry on June 26, 1866, led by Lord DerbyEdward Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby

Edward George Geoffrey Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby, KG, PC was an English statesman, three times Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, and to date the longest serving leader of the Conservative Party. He was known before 1834 as Edward Stanley, and from 1834 to 1851 as Lord Stanley...

as Prime Minister

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and...

and Disraeli as Chancellor of the Exchequer

Chancellor of the Exchequer

The Chancellor of the Exchequer is the title held by the British Cabinet minister who is responsible for all economic and financial matters. Often simply called the Chancellor, the office-holder controls HM Treasury and plays a role akin to the posts of Minister of Finance or Secretary of the...

. They were faced with the challenge of reviving Conservatism: Palmerston, the powerful Liberal leader, was dead and the Liberal Party split and defeated. Thanks to manoeuvring by Disraeli, the Conservatives had this one chance to prove that they were a viable party of government. However, there was still a Liberal majority in the Commons.

The Adullamites, led by Robert Lowe

Robert Lowe, 1st Viscount Sherbrooke

Robert Lowe, 1st Viscount Sherbrooke PC , British and Australian statesman, was a pivotal but often forgotten figure who shaped British politics in the latter half of the 19th century. He held office under William Ewart Gladstone as Chancellor of the Exchequer between 1868 and 1873 and as Home...

, had already been working closely with the Conservative Party

Conservative Party (UK)

The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

. The Adullamites were anti-reform, as were the Conservatives, but the Adullamites declined the invitation to enter into Government with the Conservatives as they thought that they could have more influence from an independent position. Despite the fact that he had blocked the Liberal Reform Bill, in February 1867, Disraeli introduced his own Reform Bill into the House of Commons.

By this time the attitude of many in the country had ceased to be apathetic regarding Reform. Huge meetings held by the radical MP John Bright

John Bright

John Bright , Quaker, was a British Radical and Liberal statesman, associated with Richard Cobden in the formation of the Anti-Corn Law League. He was one of the greatest orators of his generation, and a strong critic of British foreign policy...

, the 'Hyde Park riots' and the feeling that many of the skilled working class were respectable had persuaded many that there should be a Reform Bill. The Conservative Lord Cranborne resigned in disgust.

The Reform League

Reform League

The Reform League was established in 1865 to press for manhood suffrage and the ballot in Great Britain. It collaborated with the more moderate and middle class Reform Union and gave strong support to the abortive Reform Bill 1866 and the successful Reform Act 1867...

, agitating for universal suffrage

Universal suffrage

Universal suffrage consists of the extension of the right to vote to adult citizens as a whole, though it may also mean extending said right to minors and non-citizens...

, became much more active and organized demonstrations of hundreds of thousands of people in Manchester

Manchester

Manchester is a city and metropolitan borough in Greater Manchester, England. According to the Office for National Statistics, the 2010 mid-year population estimate for Manchester was 498,800. Manchester lies within one of the UK's largest metropolitan areas, the metropolitan county of Greater...

, Glasgow

Glasgow

Glasgow is the largest city in Scotland and third most populous in the United Kingdom. The city is situated on the River Clyde in the country's west central lowlands...

and other towns. Though these movements did not normally use revolutionary language like some Chartists had in the 1840s, they were powerful movements. The high point came when a demonstration in May 1867 in Hyde Park

Hyde Park, London

Hyde Park is one of the largest parks in central London, United Kingdom, and one of the Royal Parks of London, famous for its Speakers' Corner.The park is divided in two by the Serpentine...

was banned by the government. Thousands of troops and policemen were prepared, but the crowds were so huge that the government did not dare to attack. The Home Secretary, Spencer Walpole

Spencer Horatio Walpole

Spencer Horatio Walpole, QC, LLD was a British Conservative politician who served three times as Home Secretary in the administrations of Lord Derby.-Background and education:...

, was forced to resign.

William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone FRS FSS was a British Liberal statesman. In a career lasting over sixty years, he served as Prime Minister four separate times , more than any other person. Gladstone was also Britain's oldest Prime Minister, 84 years old when he resigned for the last time...

. An amendment tabled by the opposition trebled the new number eligible to vote under the bill, yet Disraeli simply accepted it. The bill enfranchised most men who lived in urban areas. The final proposals were as follows: a borough franchise for all who paid rates in person (that is, not compounders), and extra votes for graduates, professionals and those with over £50 savings. These last "fancy franchises" were seen by Conservatives as a weapon against a mass electorate.

However, Gladstone attacked the bill; a series of sparkling parliamentary debates with Disraeli, resulted in the bill being much more radical. Ironically, having been given his chance by the belief that Gladstone's bill had gone too far in 1866, Disraeli had now gone further.

Disraeli was able to persuade his party to vote for the bill on the basis that the newly enfranchised electorate would be grateful and vote Conservative at the next election. Despite this prediction, in 1868, the Conservatives lost the first general election

United Kingdom general election, 1868

The 1868 United Kingdom general election was the first after passage of the Reform Act 1867, which enfranchised many male householders, thus greatly increasing the number of men who could vote in elections in the United Kingdom...

in which the newly enfranchised voted.

The bill ultimately aided the rise of the radical wing of the Liberal Party and helped Gladstone to victory. The Act was tidied up with many further Acts to alter the electoral boundaries.

Disenfranchised and rotten boroughsRotten boroughA "rotten", "decayed" or pocket borough was a parliamentary borough or constituency in the United Kingdom that had a very small electorate and could be used by a patron to gain undue and unrepresentative influence within Parliament....

Two electoral boroughs were completely disenfranchised by the Act:- TotnesTotnesTotnes is a market town and civil parish at the head of the estuary of the River Dart in Devon, England within the South Devon Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty...

, Devon - Great YarmouthGreat YarmouthGreat Yarmouth, often known to locals as Yarmouth, is a coastal town in Norfolk, England. It is at the mouth of the River Yare, east of Norwich.It has been a seaside resort since 1760, and is the gateway from the Norfolk Broads to the sea...

, Norfolk

Other disenfranchisements

Although not part of the Act, these are listed for continuity.The following were disenfranchised individually for corruption:

- LancasterLancaster, LancashireLancaster is the county town of Lancashire, England. It is situated on the River Lune and has a population of 45,952. Lancaster is a constituent settlement of the wider City of Lancaster, local government district which has a population of 133,914 and encompasses several outlying towns, including...

, 1867 - ReigateReigateReigate is a historic market town in Surrey, England, at the foot of the North Downs, and in the London commuter belt. It is one of the main constituents of the Borough of Reigate and Banstead...

, 1867

Seven English boroughs were disenfranchised by the Representation of the People (Scotland) Act 1868

Representation of the People (Scotland) Act 1868

The Representation of the People Act 1868 was an Act of Parliament in the United Kingdom. It carried on from the Representation of the People Act 1867, and created seven additional Scottish seats in the House of Commons at the expense of seven English borough constituencies, which were...

the subsequent year:

- ArundelArundelArundel is a market town and civil parish in the South Downs of West Sussex in the south of England. It lies south southwest of London, west of Brighton, and east of the county town of Chichester. Other nearby towns include Worthing east southeast, Littlehampton to the south and Bognor Regis to...

, Sussex - Ashburton, Devon

- DartmouthDartmouth, DevonDartmouth is a town and civil parish in the English county of Devon. It is a tourist destination set on the banks of the estuary of the River Dart, which is a long narrow tidal ria that runs inland as far as Totnes...

, Devon - HonitonHonitonHoniton is a town and civil parish in East Devon, situated close to the River Otter, north east of Exeter in the county of Devon. The town's name is pronounced in two ways, and , each pronunciation having its adherents...

, Devon - Lyme RegisLyme RegisLyme Regis is a coastal town in West Dorset, England, situated 25 miles west of Dorchester and east of Exeter. The town lies in Lyme Bay, on the English Channel coast at the Dorset-Devon border...

, Dorset - ThetfordThetfordThetford is a market town and civil parish in the Breckland district of Norfolk, England. It is on the A11 road between Norwich and London, just south of Thetford Forest. The civil parish, covering an area of , has a population of 21,588.-History:...

, Norfolk - WellsWellsWells is a cathedral city and civil parish in the Mendip district of Somerset, England, on the southern edge of the Mendip Hills. Although the population recorded in the 2001 census is 10,406, it has had city status since 1205...

, Somerset

Halved representation

The following boroughs were reduced from electing two MPs to one:- AndoverAndover, HampshireAndover is a town in the English county of Hampshire. The town is on the River Anton some 18.5 miles west of the town of Basingstoke, 18.5 miles north-west of the city of Winchester and 25 miles north of the city of Southampton...

, Hampshire - BodminBodminBodmin is a civil parish and major town in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is situated in the centre of the county southwest of Bodmin Moor.The extent of the civil parish corresponds fairly closely to that of the town so is mostly urban in character...

, Cornwall - BridgnorthBridgnorthBridgnorth is a town in Shropshire, England, along the Severn Valley. It is split into Low Town and High Town, named on account of their elevations relative to the River Severn, which separates the upper town on the right bank from the lower on the left...

, Shropshire - BridportBridportBridport is a market town in Dorset, England. Located near the coast at the western end of Chesil Beach at the confluence of the River Brit and its Asker and Simene tributaries, it originally thrived as a fishing port and rope-making centre...

, Dorset - BuckinghamBuckinghamBuckingham is a town situated in north Buckinghamshire, England, close to the borders of Northamptonshire and Oxfordshire. The town has a population of 11,572 ,...

, Buckinghamshire - ChichesterChichester (district)Chichester is a largely rural local government district in West Sussex, England. Its council is based in the city of Chichester.-History:The district was formed on 1 April 1974, under the Local Government Act 1972, as a merger of the municipal borough of Chichester and the Rural Districts of...

, Sussex - ChippenhamChippenham, WiltshireChippenham is a market town in Wiltshire, England, located east of Bath and west of London. In the 2001 census the population of the town was recorded as 28,065....

, Wiltshire - CirencesterCirencesterCirencester is a market town in east Gloucestershire, England, 93 miles west northwest of London. Cirencester lies on the River Churn, a tributary of the River Thames, and is the largest town in the Cotswold District. It is the home of the Royal Agricultural College, the oldest agricultural...

, Gloucestershire - CockermouthCockermouth-History:The Romans created a fort at Derventio, now the adjoining village of Papcastle, to protect the river crossing, which had become located on a major route for troops heading towards Hadrian's Wall....

, Cumberland - DevizesDevizesDevizes is a market town and civil parish in Wiltshire, England. The town is about southeast of Chippenham and about east of Trowbridge.Devizes serves as a centre for banks, solicitors and shops, with a large open market place where a market is held once a week...

, Wiltshire - Dorchester, Dorset

- Evesham, Worcestershire

- GuildfordGuildfordGuildford is the county town of Surrey. England, as well as the seat for the borough of Guildford and the administrative headquarters of the South East England region...

, Surrey - HarwichHarwichHarwich is a town in Essex, England and one of the Haven ports, located on the coast with the North Sea to the east. It is in the Tendring district. Nearby places include Felixstowe to the northeast, Ipswich to the northwest, Colchester to the southwest and Clacton-on-Sea to the south...

, Essex - HertfordHertfordHertford is the county town of Hertfordshire, England, and is also a civil parish in the East Hertfordshire district of the county. Forming a civil parish, the 2001 census put the population of Hertford at about 24,180. Recent estimates are that it is now around 28,000...

, Hertfordshire - HuntingdonHuntingdonHuntingdon is a market town in Cambridgeshire, England. The town was chartered by King John in 1205. It is the traditional county town of Huntingdonshire, and is currently the seat of the Huntingdonshire district council. It is known as the birthplace in 1599 of Oliver Cromwell.-History:Huntingdon...

, Huntingdonshire - KnaresboroughKnaresboroughKnaresborough is an old and historic market town, spa town and civil parish in the Borough of Harrogate, North Yorkshire, England, located on the River Nidd, four miles east of the centre of Harrogate.-History:...

, West Riding of Yorkshire - LeominsterLeominsterLeominster is a market town in Herefordshire, England, located approximately north of the city of Hereford and south of Ludlow, at...

, Herefordshire - LewesLewesLewes is the county town of East Sussex, England and historically of all of Sussex. It is a civil parish and is the centre of the Lewes local government district. The settlement has a history as a bridging point and as a market town, and today as a communications hub and tourist-oriented town...

, Sussex - LichfieldLichfieldLichfield is a cathedral city, civil parish and district in Staffordshire, England. One of eight civil parishes with city status in England, Lichfield is situated roughly north of Birmingham...

, Staffordshire - LudlowLudlowLudlow is a market town in Shropshire, England close to the Welsh border and in the Welsh Marches. It lies within a bend of the River Teme, on its eastern bank, forming an area of and centred on a small hill. Atop this hill is the site of Ludlow Castle and the market place...

, Shropshire - LymingtonLymingtonLymington is a port on the west bank of the Lymington River on the Solent, in the New Forest district of Hampshire, England. It is to the east of the South East Dorset conurbation, and faces Yarmouth on the Isle of Wight which is connected to it by a car ferry, operated by Wightlink. The town...

, Hampshire - MaldonMaldon, EssexMaldon is a town on the Blackwater estuary in Essex, England. It is the seat of the Maldon district and starting point of the Chelmer and Blackwater Navigation.Maldon is twinned with the Dutch town of Cuijk...

, Essex - MarlowMarlow, BuckinghamshireMarlow is a town and civil parish within Wycombe district in south Buckinghamshire, England...

, Buckinghamshire - MaltonMalton, North YorkshireMalton is a market town and civil parish in North Yorkshire, England. The town is the location of the offices of Ryedale District Council and has a population of around 4,000 people....

, North Riding of Yorkshire - Marlborough, Wiltshire

- NewportNewport, Isle of WightNewport is a civil parish and a county town of the Isle of Wight, an island off the south coast of England. Newport has a population of 23,957 according to the 2001 census...

, Isle of Wight - PoolePoolePoole is a large coastal town and seaport in the county of Dorset, on the south coast of England. The town is east of Dorchester, and Bournemouth adjoins Poole to the east. The Borough of Poole was made a unitary authority in 1997, gaining administrative independence from Dorset County Council...

, Dorset - RichmondRichmond, North YorkshireRichmond is a market town and civil parish on the River Swale in North Yorkshire, England and is the administrative centre of the district of Richmondshire. It is situated on the edge of the Yorkshire Dales National Park, and serves as the Park's main tourist centre...

, North Riding of Yorkshire - RiponRiponRipon is a cathedral city, market town and successor parish in the Borough of Harrogate, North Yorkshire, England, located at the confluence of two streams of the River Ure in the form of the Laver and Skell. The city is noted for its main feature the Ripon Cathedral which is architecturally...

, West Riding of Yorkshire - StamfordStamford, LincolnshireStamford is a town and civil parish within the South Kesteven district of the county of Lincolnshire, England. It is approximately to the north of London, on the east side of the A1 road to York and Edinburgh and on the River Welland...

, Lincolnshire - Tavistock, Devon

- TewkesburyTewkesburyTewkesbury is a town in Gloucestershire, England. It stands at the confluence of the River Severn and the River Avon, and also minor tributaries the Swilgate and Carrant Brook...

, Gloucestershire - WindsorWindsor, BerkshireWindsor is an affluent suburban town and unparished area in the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead in Berkshire, England. It is widely known as the site of Windsor Castle, one of the official residences of the British Royal Family....

, Berkshire - WycombeHigh WycombeHigh Wycombe , commonly known as Wycombe and formally called Chepping Wycombe or Chipping Wycombe until 1946,is a large town in Buckinghamshire, England. It is west-north-west of Charing Cross in London; this figure is engraved on the Corn Market building in the centre of the town...

, Buckinghamshire

Enfranchisements

The Act created a number of new boroughs in Parliament. The following boroughs were enfranchised with one MP:- BurnleyBurnleyBurnley is a market town in the Burnley borough of Lancashire, England, with a population of around 73,500. It lies north of Manchester and east of Preston, at the confluence of the River Calder and River Brun....

, Lancashire - DarlingtonDarlingtonDarlington is a market town in the Borough of Darlington, part of the ceremonial county of County Durham, England. It lies on the small River Skerne, a tributary of the River Tees, not far from the main river. It is the main population centre in the borough, with a population of 97,838 as of 2001...

, County Durham - DewsburyDewsburyDewsbury is a minster town in the Metropolitan Borough of Kirklees, in West Yorkshire, England. It is to the west of Wakefield, east of Huddersfield and south of Leeds...

, West Riding of Yorkshire - GravesendGravesend, KentGravesend is a town in northwest Kent, England, on the south bank of the Thames, opposite Tilbury in Essex. It is the administrative town of the Borough of Gravesham and, because of its geographical position, has always had an important role to play in the history and communications of this part of...

, Kent - HartlepoolHartlepoolHartlepool is a town and port in North East England.It was founded in the 7th century AD, around the Northumbrian monastery of Hartlepool Abbey. The village grew during the Middle Ages and developed a harbour which served as the official port of the County Palatine of Durham. A railway link from...

, County Durham - MiddlesbroughMiddlesbroughMiddlesbrough is a large town situated on the south bank of the River Tees in north east England, that sits within the ceremonial county of North Yorkshire...

, North Riding of Yorkshire - StalybridgeStalybridgeStalybridge is a town in the Metropolitan Borough of Tameside in Greater Manchester, England, with a population of 22,568. Historically a part of Cheshire, it is east of Manchester city centre and northwest of Glossop. With the construction of a cotton mill in 1776, Stalybridge became one of...

, Cheshire - StocktonStockton-on-TeesStockton-on-Tees is a market town in north east England. It is the major settlement in the unitary authority and borough of Stockton-on-Tees. For ceremonial purposes, the borough is split between County Durham and North Yorkshire as it also incorporates a number of smaller towns including...

, County Durham - WednesburyWednesburyWednesbury is a market town in England's Black Country, part of the Sandwell metropolitan borough in West Midlands, near the source of the River Tame. Similarly to the word Wednesday, it is pronounced .-Pre-Medieval and Medieval times:...

, Staffordshire

The following boroughs were enfranchised with two MPs:

- ChelseaChelsea, LondonChelsea is an area of West London, England, bounded to the south by the River Thames, where its frontage runs from Chelsea Bridge along the Chelsea Embankment, Cheyne Walk, Lots Road and Chelsea Harbour. Its eastern boundary was once defined by the River Westbourne, which is now in a pipe above...

, Middlesex - HackneyLondon Borough of HackneyThe London Borough of Hackney is a London borough of North/North East London, and forms part of inner London. The local authority is Hackney London Borough Council....

, Middlesex

In addition, the Act adjusted the representation of several existing boroughs. Salford

County Borough of Salford

Salford was, from 1844 to 1974, a local government district in the northwest of England, coterminate with Salford. It was granted city status in 1926.-Free Borough and Police Commissioners:...

and Merthyr Tydfil

Merthyr Tydfil

Merthyr Tydfil is a town in Wales, with a population of about 30,000. Although once the largest town in Wales, it is now ranked as the 15th largest urban area in Wales. It also gives its name to a county borough, which has a population of around 55,000. It is located in the historic county of...

were given two MPs instead of one.

Birmingham

Birmingham

Birmingham is a city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands of England. It is the most populous British city outside the capital London, with a population of 1,036,900 , and lies at the heart of the West Midlands conurbation, the second most populous urban area in the United Kingdom with a...

, Leeds

Leeds

Leeds is a city and metropolitan borough in West Yorkshire, England. In 2001 Leeds' main urban subdivision had a population of 443,247, while the entire city has a population of 798,800 , making it the 30th-most populous city in the European Union.Leeds is the cultural, financial and commercial...

, Liverpool

Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough of Merseyside, England, along the eastern side of the Mersey Estuary. It was founded as a borough in 1207 and was granted city status in 1880...

and Manchester

Manchester

Manchester is a city and metropolitan borough in Greater Manchester, England. According to the Office for National Statistics, the 2010 mid-year population estimate for Manchester was 498,800. Manchester lies within one of the UK's largest metropolitan areas, the metropolitan county of Greater...

now had three MPs instead of two.

Other changes

- The West Riding of YorkshireWest Riding of YorkshireThe West Riding of Yorkshire is one of the three historic subdivisions of Yorkshire, England. From 1889 to 1974 the administrative county, County of York, West Riding , was based closely on the historic boundaries...

was divided into three districts each returning two MPs. - CheshireCheshireCheshire is a ceremonial county in North West England. Cheshire's county town is the city of Chester, although its largest town is Warrington. Other major towns include Widnes, Congleton, Crewe, Ellesmere Port, Runcorn, Macclesfield, Winsford, Northwich, and Wilmslow...

, DerbyshireDerbyshireDerbyshire is a county in the East Midlands of England. A substantial portion of the Peak District National Park lies within Derbyshire. The northern part of Derbyshire overlaps with the Pennines, a famous chain of hills and mountains. The county contains within its boundary of approx...

, DevonDevonDevon is a large county in southwestern England. The county is sometimes referred to as Devonshire, although the term is rarely used inside the county itself as the county has never been officially "shired", it often indicates a traditional or historical context.The county shares borders with...

shire, EssexEssexEssex is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the East region of England, and one of the home counties. It is located to the northeast of Greater London. It borders with Cambridgeshire and Suffolk to the north, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent to the South and London to the south west...

, KentKentKent is a county in southeast England, and is one of the home counties. It borders East Sussex, Surrey and Greater London and has a defined boundary with Essex in the middle of the Thames Estuary. The ceremonial county boundaries of Kent include the shire county of Kent and the unitary borough of...

, LincolnshireLincolnshireLincolnshire is a county in the east of England. It borders Norfolk to the south east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south west, Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire to the west, South Yorkshire to the north west, and the East Riding of Yorkshire to the north. It also borders...

, NorfolkNorfolkNorfolk is a low-lying county in the East of England. It has borders with Lincolnshire to the west, Cambridgeshire to the west and southwest and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the North Sea coast and to the north-west the county is bordered by The Wash. The county...

, SomersetSomersetThe ceremonial and non-metropolitan county of Somerset in South West England borders Bristol and Gloucestershire to the north, Wiltshire to the east, Dorset to the south-east, and Devon to the south-west. It is partly bounded to the north and west by the Bristol Channel and the estuary of the...

, StaffordshireStaffordshireStaffordshire is a landlocked county in the West Midlands region of England. For Eurostat purposes, the county is a NUTS 3 region and is one of four counties or unitary districts that comprise the "Shropshire and Staffordshire" NUTS 2 region. Part of the National Forest lies within its borders...

and SurreySurreySurrey is a county in the South East of England and is one of the Home Counties. The county borders Greater London, Kent, East Sussex, West Sussex, Hampshire and Berkshire. The historic county town is Guildford. Surrey County Council sits at Kingston upon Thames, although this has been part of...

were now divided into three districts instead of two, each returning two MPs. - LancashireLancashireLancashire is a non-metropolitan county of historic origin in the North West of England. It takes its name from the city of Lancaster, and is sometimes known as the County of Lancaster. Although Lancaster is still considered to be the county town, Lancashire County Council is based in Preston...

was now divided into four two-member districts instead of a three-member district and a two-member district. - University of LondonUniversity of London-20th century:Shortly after 6 Burlington Gardens was vacated, the University went through a period of rapid expansion. Bedford College, Royal Holloway and the London School of Economics all joined in 1900, Regent's Park College, which had affiliated in 1841 became an official divinity school of the...

was given one seat. - Parliament was allowed to continue sitting through a Demise of the CrownDemise of the CrownIn relation to the shared monarchy of the Commonwealth realms and other monarchies, the demise of the Crown is the legal term for the end of a reign by a king, queen, or emperor, whether by death or abdication....

. - Cabinet ministers from the House of Commons were no longer required to undergo re-election when taking a different portfolio in the cabinet.

Reforms in Scotland and Ireland

The reforms for ScotlandScotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

and Ireland

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

were carried out by two subsequent acts, the Representation of the People (Ireland) Act 1868

Representation of the People (Ireland) Act 1868

The Representation of the People Act 1868 was an Act of Parliament in the United Kingdom.It did not alter the overall distribution of parliamentary seats in Ireland, but did alter their boundaries, including making the electoral constituency of a borough be the same as its municipal boundaries....

and the Representation of the People (Scotland) Act 1868

Representation of the People (Scotland) Act 1868

The Representation of the People Act 1868 was an Act of Parliament in the United Kingdom. It carried on from the Representation of the People Act 1867, and created seven additional Scottish seats in the House of Commons at the expense of seven English borough constituencies, which were...

.

In Scotland, five existing constituencies gained members, and three new constituencies were formed. Two existing county constituencies were merged into one, giving an overall increase of seven members; this was offset by seven English boroughs (listed above) being disenfranchised, leaving the House with the same number of members.

The representation of Ireland remained unchanged.

Direct effects of the Act

The unprecedented extension of the franchise to all householders effectively gave the vote to the working classes, a quite considerable change. JH Parry described this as a 'borough franchise revolution'; the traditional position of the landed gentry in parliament would no longer be assured by money, bribery and favours; but by the whims and wishes of the public. However, to blindly consider the de jure franchise extensions would be fallacious. The franchise provisions were flawed; the act did not address the issue of compounding. The compounding of rates and rents was made illegal, after it was abolished by G. Hodgkinson (although this meant that all tenants would have to pay rates directly and thus qualify for the vote). The preparation of the register was still left to easily manipulated party organisers who could remove opponents and add supporters at will. The sole qualification to vote was essentially being on the register itself.Unintended effects

- Increased amounts of party spending and political organisation at both a local and national level—politicians had to account themselves to the increased electorate.

- The redistribution of seats actually served to make the House of Commons increasingly dominated by the upper classes. Only they could afford to pay the huge campaigning costs and the abolition of certain rotten boroughs removed some of the middle-class planter merchants that had been able to obtain seats.

Extra pressure was added to the upper class and the lower and middle classes expected less. Also constituencies such as Leeds and Manchester became slightly more "lower class places."

See also

- Benjamin Disraeli

- ChartismChartismChartism was a movement for political and social reform in the United Kingdom during the mid-19th century, between 1838 and 1859. It takes its name from the People's Charter of 1838. Chartism was possibly the first mass working class labour movement in the world...

- Secret ballotSecret ballotThe secret ballot is a voting method in which a voter's choices in an election or a referendum are anonymous. The key aim is to ensure the voter records a sincere choice by forestalling attempts to influence the voter by intimidation or bribery. The system is one means of achieving the goal of...

- Official names of United Kingdom Parliamentary constituenciesOfficial names of United Kingdom Parliamentary ConstituenciesThe official names of United Kingdom Parliamentary constituencies are those given in the legal instrument creating the constituency or re-defining it at a re-distribution of seats.The purpose of this article is to set out official names, taken from official sources wherever possible, to provide a...

for names of constituencies provided for by this Act - The Parliamentary ArchivesParliamentary ArchivesThe Parliamentary Archives of the United Kingdom preserves and makes available to public the records of the House of Lords and House of Commons back to 1497, as well as some 200 other collections of Parliamentary interest...

holds the original of this historic record.