Religion in the Soviet Union

Encyclopedia

The Soviet Union

was the first state to have as an ideological objective the elimination of religion

and its replacement with atheism

. To that end, the communist regime confiscated religious property, ridiculed religion, harassed believers, and propagated atheism in schools. The confiscation of religious assets was often based on accusations of illegal accumulation of wealth.

State atheism in the Soviet Union was known as gosateizm, and was based on the ideology of Marxism–Leninism. As the founder of the Soviet state, V. I. Lenin, put it:

Marxism–Leninism has consistently advocated the control, suppression, and eventual elimination of religion. Within about a year of the revolution, the state expropriated all church property, including the churches themselves, and in the period from 1922 to 1926, 28 Russian Orthodox bishop

s and more than 1,200 priest

s were killed. Many more were persecuted.

Christians belonged to various churches: Orthodox

(which had the largest number of followers), Catholic

, and Baptist

and various other Protestant sects. The majority of the Muslims in the Soviet Union were Sunni. Judaism

also had many followers. Other religions, practiced by a relatively small number of believers, included Buddhism

and Shamanism

.

, the Georgian Orthodox Church, and the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church

(AOC). They were members of the major confederation of Orthodox churches in the world, generally referred to as the Eastern Orthodox Church. The first two functioned openly and were tolerated by the regime, but the Ukrainian AOC was not permitted to function openly. Parishes of the Belarusian Autocephalous Orthodox Church

reappeared in Belarus only after the dissolution of the Soviet Union

, but they did not receive recognition from the Belarusian Exarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church

, which controls Belarusian eparchies.

). The distribution of the six monasteries and ten convents of the Russian Orthodox Church was equally disproportionate. Only two of the monasteries were located in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

. Another two were in Ukraine and there was one each in Belarus and Lithuania. Seven convents were located in the Ukraine one each in the Moldova

, Estonia, and Latvia.

. Nevertheless, the Russian Orthodox Church did not officially recognize its independence until 1943.

From its inception, the Ukrainian AOC faced the hostility of the Russian Orthodox Church in the Ukrainian Republic. In the late 1920s, Soviet authorities accused it of nationalist tendencies. In 1930 the government forced the church to reorganize as the "Ukrainian Orthodox Church", and few of its parishes survived until 1936. Nevertheless, the Ukrainian AOC continued to function outside the borders of the Soviet Union, and it was revived on Ukrainian territory under the German occupation during World War II

. In the late 1980s, some of the Orthodox faithful in the Ukrainian Republic appealed to the Soviet government to reestablish the Ukrainian AOC.

is an independent Oriental Orthodox church. In the 1980s it had about 4 million adherents – almost the entire population of Armenia. It was permitted 6 bishops, between 50 and 100 priests, and between 20 and 30 churches, and it had one theological seminary and six monasteries.

in 1939 and the Baltic republics in 1940. Catholics in the Soviet Union were divided between those belonging to the Roman Catholic Church

, which was recognized by the government, and those remaining loyal to the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church

, banned since 1946.

, but was Eastern Rite Catholic. After the Second World War, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church

identified closely with the nationalist aspirations of the region, arousing the hostility of the Soviet government, which was in combat with Ukrainian Insurgency. In 1945, Soviet authorities arrested the church's Metropolitan Josyf Slipyj, nine bishops and hundreds of clergy and leading lay activists, and deported them to forced labor camps in Siberia and elsewhere. The nine bishops and many of the clergy died in prisons, concentration camps, internal exile, or soon after their release during the post-Stalin thaw, but after 18 years of imprisonment and persecution, Metropolitan Slipyj was released when Pope John XXIII

intervened on his behalf. Slipyj went to Rome, where he received the title of Major Archbishop of Lviv, and became a cardinal in 1965.

In 1946 a synod was called in Lviv

, where, despite being uncanonical in both Catholic and Orthodox understanding, the Union of Brest

was annulled, and the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church was officially annexed to the Russian Orthodox Church. St. George's Cathedral

in Lviv became the throne of Russian Orthodox Archbishop Makariy.

For the clergy that joined the Russian Orthodox Church, the Soviet authorities refrained from the large-scale persecution seen elsewhere. In Lviv only one church was closed. In fact, the western dioceses of Lviv-Ternopil and Ivano-Frankivsk were the largest in the USSR. Canon law was also relaxed, allowing the clergy to shave their beards (a practice uncommon in Orthodoxy) and to conduct services in Ukrainian instead of Slavonic.

In 1989 the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church was officially re-established after a catacomb period of more than 40 years. There followed conflicts between Orthodox and Catholic Christians regarding the ownership of church buildings, conflicts which continued into the 1990s, after the Independence of Ukraine.

Many Protestants fell victim to communist persecution, including imprisonment and execution. Vladimir Shelkov

(1895–1980), the leader of the unregistered Seventh-day Adventist

movement in the Soviet Union, spent almost all his life from 1931 on in prison; he died in Yakutia camp. Large numbers of Pentecostals were imprisoned, and many died there, including Ivan Voronaev

, one of their leaders.

In the period after the Second World War, Protestants in the USSR (Baptists, Pentecostals, Adventists and others) were sent to mental hospitals or tried and imprisoned, often for refusal to enter military service. Some were deprived of their parental rights.

The Lutheran Church in different regions of the country was persecuted during the Soviet era, and church property was confiscated. Many of its members and pastors were oppressed, and some were forced to emigrate.

According to western sources, various Protestant religious groups collectively had as many as 5 million followers in the 1980s. Evangelical Christian Baptists constituted the largest Protestant group. Spread throughout the Soviet Union, some congregations were registered with the government and functioned with official approval. Many other unregistered congregations carried on religious activity without such approval.

Lutherans, the second largest Protestant group, lived for the most part in the Latvian and Estonian republics. In the 1980s, Lutheran churches in these republics identified to some extent with nationality issues in the two republics. The regime's attitude toward Lutherans was generally benign.

, and other regions.

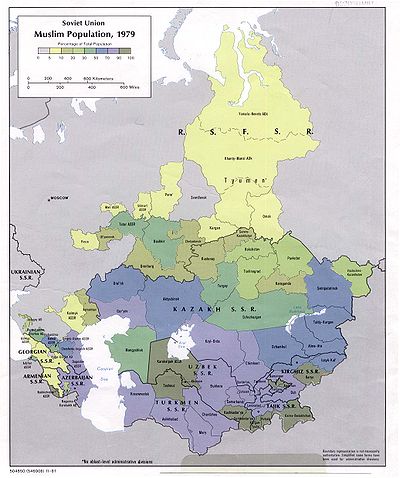

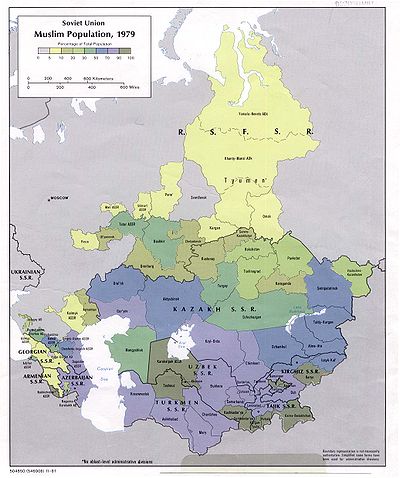

In the late 1980s, Islam had the second largest following in the Soviet Union: between 45 and 50 million people identified themselves as Muslims. But the Soviet Union had only about 500 working mosque

In the late 1980s, Islam had the second largest following in the Soviet Union: between 45 and 50 million people identified themselves as Muslims. But the Soviet Union had only about 500 working mosque

s, a fraction of the number in prerevolutionary Russia, and Soviet law forbade Islamic religious activity outside working mosques and Islamic schools.

All working mosques, religious schools, and Islamic publications were supervised by four "spiritual directorates" established by Soviet authorities to provide government control. The Spiritual Directorate for Central Asia and Kazakhstan

, the Spiritual Directorate for the European Soviet Union and Siberia, and the Spiritual Directorate for the Northern Caucasus and Dagestan

oversaw the religious life of Sunni Muslims. The Spiritual Directorate for Transcaucasia dealt with both Sunni Muslims and Shia Muslims. The overwhelming majority of the Muslims were Sunnis.

Soviet Muslims differed linguistically and culturally from each other, speaking about fifteen Turkic languages

, ten Iranian languages

, and thirty Caucasian languages. Hence, communication between different Muslim groups was difficult. Although in 1989 Russian often served as a lingua franca among some educated Muslims, few were fluent in Russian.

Culturally, some Muslim groups had highly developed urban traditions, whereas others were recently nomadic. Some lived in industrialized environments, others in isolated mountainous regions. In sum, Muslims were not a homogeneous group with a common national identity and heritage, although they shared the same religion and the same country.

In the late 1980s, unofficial Muslim congregations, meeting in tea houses and private homes with their own mullah

s, greatly outnumbered those in the officially sanctioned mosques. The unofficial mullahs were either self-taught or informally trained by other mullahs. In the late 1980s, unofficial Islam appeared to split into fundamentalist congregations and groups that emphasized Sufism

.

, which made atheism the official doctrine of the Communist Party. However, "the Soviet law and administrative practice through most of the 1920s extended some tolerance to religion and forbade the arbitrary closing or destruction of some functioning churches", and each successive Soviet constitution granted freedom of belief. As the founder of the Soviet state, Lenin, put it:

Marxism-Leninism advocates the suppression and ultimately the disappearance of religious beliefs, considering them to be "unscientific" and "superstitious". In the 1920s and 1930s, such organizations as the League of the Militant Godless were active in anti-religious propaganda. Atheism was the norm in schools, communist organizations (such as the Young Pioneer Organization

), and the media.

The regime's efforts to eradicate religion in the Soviet Union, however, varied over the years with respect to particular religions and were affected by higher state interests. In 1923, a New York Times correspondent saw Christians observing Easter peacefully in Moscow despite violent anti-religious actions in previous years. Official policies and practices not only varied with time, but also differed in their application from one nationality to another and from one religion to another.

Although all Soviet leaders had the same long-range goal of developing a cohesive Soviet people, they pursued different policies to achieve it. For the Soviet regime, questions of nationality and religion were always closely linked. Therefore their attitude toward religion also varied from a total ban on some religions to official support of others.

Twenty-two nationalities lived in autonomous republics with a degree of local self-government and representation in the Council of Nationalities in the Supreme Soviet. Eighteen more nationalities had territorial enclaves (autonomous oblast

s and autonomous okrug

s) but had very few powers of self-government. The remaining nationalities had no right of self-government at all. Joseph Stalin

's 1913 definition of a nation as "a historically constituted and stable community of people formed on the basis of common language, territory, economic life, and psychological makeup revealed in a common culture" was retained by Soviet authorities throughout the 1980s. However, in granting nationalities union republic status, three additional factors were considered: a population of at least 1 million, territorial compactness, and location on the borders of the Soviet Union.

Although Lenin believed that eventually all nationalities would merge into one, he insisted that the Soviet Union be established as a federation of formally equal nations. In the 1920s, genuine cultural concessions were granted to the nationalities. Communist elites of various nationalities were permitted to flourish and to have considerable self-government. National cultures, religions, and languages were not merely tolerated but, in areas with Muslim populations, encouraged.

Demographic changes in the 1960s and 1970s whittled down the overall Russian majority, but they also caused two nationalities (the Kazakhs and Kirgiz) to become minorities in their own republics at the time of the 1979 census, and considerably reduced the majority of the titular nationalities in other republics. This situation led Leonid Brezhnev

to declare at the 24th Communist Party Congress in 1971 that the process of creating a unified Soviet people had been completed, and proposals were made to abolish the federative system and replace it with a single state. In the 1970s, however, a broad movement of national dissent began to spread throughout the Soviet Union. It manifestated itself in many ways: Jews insisted on their right to emigrate to Israel; Crimean Tatars

demanded to be allowed to return to Crimea; Lithuanians called for the restoration of the rights of the Catholic Church; and Helsinki Watch

groups were established in the Georgian, Lithuanian, and Ukrainian republics. Petitions, literature, and occasional public demonstrations voiced public demands for the human rights of all nationalities. By the end of the 1970s, however, massive and concerted efforts by the KGB

had largely suppressed the national dissent movement. Nevertheless, Brezhnev had learned his lesson. Proposals to dismantle the federative system were abandoned in favour of a policy of drawing the nationalities together more gradually.

Soviet officials identified religion closely with nationality. The implementation of policy toward a particular religion, therefore, depended on the regime's perception of the bond between that religion and the nationality practicing it, the size of the religious community, the extent to which the religion accepted outside authority, and the nationality's willingness to subordinate itself to political authority. Thus the smaller the religious community and the more closely it identified with a particular nationality, the more restrictive were the regime's policies, especially if the religion also recognized a foreign authority such as the pope.

As for the Russian Orthodox Church, Soviet authorities sought to control it and, in times of national crisis, to exploit it for the regime's own purposes; but their ultimate goal was to eliminate it. During the first five years of Soviet power, the Bolsheviks executed 28 Russian Orthodox bishops and over 1,200 Russian Orthodox priests. Many others were imprisoned or exiled. Believers were harassed and persecuted. Most seminaries were closed, and the publication of most religious material was prohibited. By 1941 only 500 churches remained open out of about 54,000 in existence prior to World War I.

As for the Russian Orthodox Church, Soviet authorities sought to control it and, in times of national crisis, to exploit it for the regime's own purposes; but their ultimate goal was to eliminate it. During the first five years of Soviet power, the Bolsheviks executed 28 Russian Orthodox bishops and over 1,200 Russian Orthodox priests. Many others were imprisoned or exiled. Believers were harassed and persecuted. Most seminaries were closed, and the publication of most religious material was prohibited. By 1941 only 500 churches remained open out of about 54,000 in existence prior to World War I.

Such crackdowns related to many people's dissatisfaction with the church in pre-revolutionary Russia. The close ties between the church and the state led to the perception of the church as corrupt and greedy by many members of the intelligentsia

. Many peasant

s, while highly religious, also viewed the church unfavorably. Respect for religion did not extend to the local priests. The church owned a significant portion of Russia's land, and this was a bone of contention – land ownership was a big factor in the Russian Revolution of 1917

.

The Nazi

attack on the Soviet Union in 1941 forced Stalin to enlist the Russian Orthodox Church as an ally to arouse Russian patriotism against foreign aggression. Russian Orthodox religious life experienced a revival: thousands of churches were reopened; there were 22,000 by the time Nikita Khrushchev

came to power. The regime permitted religious publications, and church membership grew.

Khrushchev reversed the regime's policy of cooperation with the Russian Orthodox Church. Although it remained officially sanctioned, in 1959 Khrushchev launched an antireligious

campaign that was continued in a less stringent manner by his successor, Brezhnev. By 1975 the number of active Russian Orthodox churches was reduced to 7,000. Some of the most prominent members of the Russian Orthodox hierarchy and some activists were jailed or forced to leave the church. Their place was taken by docile clergy who were obedient to the state and who were sometimes infiltrated by KGB agents, making the Russian Orthodox Church useful to the regime. It espoused and propagated Soviet foreign policy and furthered the russification of non-Russian Christians, such as Orthodox Ukrainians and Belarusians.

The regime applied a different policy toward the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church and the Belarusian Autocephalous Orthodox Church. Viewed by the government as very nationalistic, both were suppressed, first at the end of the 1920s and again in 1944 after they had renewed themselves under German occupation. The leadership of both churches was decimated; large numbers of priests were shot or sent to labor camps, and members of their congregations were harassed and persecuted.

The Georgian Orthodox Church was subject to a somewhat different policy and fared far worse than the Russian Orthodox Church. During World War II, however, it was allowed greater autonomy in running its affairs in return for calling its members to support the war effort, although it did not achieve the kind of accommodation with the authorities that the Russian Orthodox Church had. The government reimposed tight control over it after the war. Out of some 2,100 churches in 1917, only 200 were still open in the 1980s, and it was forbidden to serve its adherents outside the Georgian Republic. In many cases, the regime forced the Georgian Orthodox Church to conduct services in Old Church Slavonic instead of in the Georgian language.

, the Byelorussian SSR

and the Ukrainian SSR

, Catholicism and nationalism were closely linked. Although the Roman Catholic Church was tolerated in Lithuania, large numbers of the clergy were imprisoned, many seminaries were closed, and police agents infiltrated the remainder. The anti-Catholic campaign in Lithuania abated after Stalin's death, but harsh measures against the church were resumed in 1957 and continued through the Brezhnev era.

Soviet policy was particularly harsh toward the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church. Ukrainian Greek-Catholics came under Soviet rule in 1939, when western Ukraine was incorporated into the Soviet Union as part of the Nazi-Soviet Nonaggression Pact. Although the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church was permitted to function, it was almost immediately subjected to intense harassment. Retreating before the German army in 1941, Soviet authorities arrested large numbers of Ukrainian Greek Catholic priests, who were either killed or deported to Siberia. After the Red Army reoccupied western Ukraine in 1944, the Soviet regime liquidated the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church by arresting its metropolitan, all of its bishops, hundreds of clergy, and the more active church members, killing some and sending the rest to labor camps. At the same time, Soviet authorities forced the remaining clergy to abrogate the union with Rome and subordinate themselves to the Russian Orthodox Church.

Before World War II, there were fewer Protestants in the Soviet Union than adherents of other faiths, but they showed remarkable growth since then. In 1944 the Soviet government established the All-Union Council of Evangelical Christian Baptists (now the Union of Evangelical Christians-Baptists of Russia

) to gain some control over the various Protestant sects. Many congregations refused to join this body, however, and others that initially joined it subsequently left. All found that the state, through the council, was interfering in church life.

Jehovah's Witnesses were banned from practicing their religion. Under Operation North

, the personal property of over eight-thousand members was confiscated, and they (along with underage children) were exiled to Siberia from 1951 until repeal in 1965. All were asked to sign a declaration of resignation as a Jehovah's Witness in order to not be deported. There is no existing record of any having signed this declaration. While in Siberia, some men, women, and children were forced to work as lumberjacks for a fixed wage. Victims reported living conditions to be very poor. From 1951 to 1991, Jehovah's Witnesses within and outside Siberia were incarcerated – and then rearrested after serving their terms. Some were forced to work in concentration camps, others forcibly enrolled in Marxist reeducation

programs. KGB officials infiltrated the Jehovah's Witnesses organization in the Soviet Union, mostly to seek out hidden caches of theological literature. Soviet propaganda

films depicted Jehovah's Witnesses as a cult

, extremist, and engaging in mind control

. Jehovah's Witnesses were legalized in the Soviet Union in 1991; victims were given social benefits equivalent to those of war veterans.

Early in the Bolshevik period, predominantly before the end of the Russian Civil War

and the emergence of the Soviet Union, Russian Mennonite communities were harassed; several Mennonites were killed or imprisoned, and women were raped. Anarcho-Communist Nestor Makhno

was responsible for most of the bloodshed, which caused the normally pacifist Mennonites to take up arms in defensive militia units. This marked the beginning of a mass exodus of Mennonites to Germany, the United States, and elsewhere. Mennonites were branded as kulaks by the Soviets. Their colonies' farms were collectivized under the Soviet Union's communal farming policy. Being predominantly German settlers, the Russian Mennonites in World War II saw the German forces invading Russia as liberators. Many were allowed passage to Germany as Volksdeutsche

. Soviet officials began exiling Mennonite settlers in the eastern part of Russia to Siberia. After the war, the remaining Russian Mennonites were branded as Nazi conspirators and exiled to Kazakhstan and Siberia, sometimes being imprisoned or forced to work in concentration camps. In the 1990s the Russian government gave the Mennonites in Kazakhstan and Siberia the opportunity to emigrate.

abhorrent, the regime was hostile toward Judaism

from the beginning. In 1919 the Soviet authorities abolished Jewish community councils, which were traditionally responsible for maintaining synagogues. They created a special Jewish section of the party

, whose tasks included propaganda against Jewish clergy and religion. To offset Jewish national and religious aspirations, and to reflect the Zionist heritage within the Jewish intelligentsia of the Russian Empire (for example, Trotsky was first a member of the Jewish Bund, not the Social Democratic Labour Party

), an alternative to the Land of Israel

was established in 1934.

The Jewish Autonomous Oblast

, created in 1928 by Stalin, with Birobidzhan

in the Russian Far East

as its administratice center, was to become a "Soviet Zion". Yiddish

, rather than "reactionary" Hebrew

, would be the national language, and proletarian socialist literature and arts

would replace Judaism as the quintessence of its culture. Despite a massive domestic and international state propaganda campaign, the Jewish population there never reached 30% (as of 2003 it was only about 1.2%). The experiment ended in the mid-1930s, during Stalin's first campaign of purges. Jewish leaders were arrested and executed, and Yiddish schools were shut down. Further persections and purges followed.

The training of rabbis became impossible, and until the late 1980s only one Yiddish periodical was published. Because of its identification with Zionism, Hebrew was taught only in schools for diplomats. Most of the 5,000 synagogues functioning prior to the Bolshevik Revolution were closed under Stalin, and others were closed under Khrushchev. The practice of Judaism became very difficult, intensifying the desire of Jews to leave the Soviet Union.

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

was the first state to have as an ideological objective the elimination of religion

State atheism

State atheism is the official "promotion of atheism" by a government, sometimes combined with active suppression of religious freedom and practice...

and its replacement with atheism

Atheism

Atheism is, in a broad sense, the rejection of belief in the existence of deities. In a narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there are no deities...

. To that end, the communist regime confiscated religious property, ridiculed religion, harassed believers, and propagated atheism in schools. The confiscation of religious assets was often based on accusations of illegal accumulation of wealth.

State atheism in the Soviet Union was known as gosateizm, and was based on the ideology of Marxism–Leninism. As the founder of the Soviet state, V. I. Lenin, put it:

Religion is the opium of the peopleOpium of the People"Religion is the opium of the people" is one of the most frequently paraphrased statements of Karl Marx. It was translated from the German original, "Die Religion .....

: this saying of Marx is the cornerstone of the entire ideology of Marxism about religion. All modern religions and churches, all and of every kind of religious organizations are always considered by Marxism as the organs of bourgeois reaction, used for the protection of the exploitation and the stupefaction of the working class.

Marxism–Leninism has consistently advocated the control, suppression, and eventual elimination of religion. Within about a year of the revolution, the state expropriated all church property, including the churches themselves, and in the period from 1922 to 1926, 28 Russian Orthodox bishop

Bishop

A bishop is an ordained or consecrated member of the Christian clergy who is generally entrusted with a position of authority and oversight. Within the Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox Churches, in the Assyrian Church of the East, in the Independent Catholic Churches, and in the...

s and more than 1,200 priest

Priest

A priest is a person authorized to perform the sacred rites of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particular, rites of sacrifice to, and propitiation of, a deity or deities...

s were killed. Many more were persecuted.

Christians belonged to various churches: Orthodox

Orthodoxy

The word orthodox, from Greek orthos + doxa , is generally used to mean the adherence to accepted norms, more specifically to creeds, especially in religion...

(which had the largest number of followers), Catholic

Catholicism

Catholicism is a broad term for the body of the Catholic faith, its theologies and doctrines, its liturgical, ethical, spiritual, and behavioral characteristics, as well as a religious people as a whole....

, and Baptist

Baptist

Baptists comprise a group of Christian denominations and churches that subscribe to a doctrine that baptism should be performed only for professing believers , and that it must be done by immersion...

and various other Protestant sects. The majority of the Muslims in the Soviet Union were Sunni. Judaism

Judaism

Judaism ) is the "religion, philosophy, and way of life" of the Jewish people...

also had many followers. Other religions, practiced by a relatively small number of believers, included Buddhism

Buddhism

Buddhism is a religion and philosophy encompassing a variety of traditions, beliefs and practices, largely based on teachings attributed to Siddhartha Gautama, commonly known as the Buddha . The Buddha lived and taught in the northeastern Indian subcontinent some time between the 6th and 4th...

and Shamanism

Shamanism

Shamanism is an anthropological term referencing a range of beliefs and practices regarding communication with the spiritual world. To quote Eliade: "A first definition of this complex phenomenon, and perhaps the least hazardous, will be: shamanism = technique of ecstasy." Shamanism encompasses the...

.

Orthodox

Orthodox Christians constituted a majority of believers in the Soviet Union. In the late 1980s, three Orthodox churches claimed substantial memberships there: the Russian Orthodox ChurchRussian Orthodox Church

The Russian Orthodox Church or, alternatively, the Moscow Patriarchate The ROC is often said to be the largest of the Eastern Orthodox churches in the world; including all the autocephalous churches under its umbrella, its adherents number over 150 million worldwide—about half of the 300 million...

, the Georgian Orthodox Church, and the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church

Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church

The Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church is one of the three major Orthodox Churches in Ukraine. Close to ten percent of the Christian population claim to be members of the UAOC. The other Churches are the Ukrainian Orthodox Church-Kiev Patriarchate and the Ukrainian Russophile Orthodox...

(AOC). They were members of the major confederation of Orthodox churches in the world, generally referred to as the Eastern Orthodox Church. The first two functioned openly and were tolerated by the regime, but the Ukrainian AOC was not permitted to function openly. Parishes of the Belarusian Autocephalous Orthodox Church

Belarusian Autocephalous Orthodox Church

The Belarusian Autocephalous Orthodox Church, which has sometimes abbreviated its name as the "B.A.O. Church" or the "BAOC," aspires to be the self-governing national church of an independent Belarus, but it has operated mostly in exile since its formation, and even some publications of the church...

reappeared in Belarus only after the dissolution of the Soviet Union

Dissolution of the Soviet Union

The dissolution of the Soviet Union was the disintegration of the federal political structures and central government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , resulting in the independence of all fifteen republics of the Soviet Union between March 11, 1990 and December 25, 1991...

, but they did not receive recognition from the Belarusian Exarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church

Russian Orthodox Church

The Russian Orthodox Church or, alternatively, the Moscow Patriarchate The ROC is often said to be the largest of the Eastern Orthodox churches in the world; including all the autocephalous churches under its umbrella, its adherents number over 150 million worldwide—about half of the 300 million...

, which controls Belarusian eparchies.

Russian Orthodox Church

According to both Soviet and Western sources, in the late 1980s the Russian Orthodox Church had over 50 million believers but only about 7,000 registered active churches. Over 4,000 of these churches were located in the Ukrainian Republic (almost half of them in western UkraineUkraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It has an area of 603,628 km², making it the second largest contiguous country on the European continent, after Russia...

). The distribution of the six monasteries and ten convents of the Russian Orthodox Church was equally disproportionate. Only two of the monasteries were located in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic , commonly referred to as Soviet Russia, Bolshevik Russia, or simply Russia, was the largest, most populous and economically developed republic in the former Soviet Union....

. Another two were in Ukraine and there was one each in Belarus and Lithuania. Seven convents were located in the Ukraine one each in the Moldova

Moldova

Moldova , officially the Republic of Moldova is a landlocked state in Eastern Europe, located between Romania to the West and Ukraine to the North, East and South. It declared itself an independent state with the same boundaries as the preceding Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1991, as part...

, Estonia, and Latvia.

Georgian Orthodox Church

The Georgian Orthodox Church, another autocephalous member of Eastern Orthodoxy, was headed by a Georgian patriarch. In the late 1980s it had 15 bishops, 180 priests, 200 parishes, and an estimated 2.5 million followers. In 1811 the Georgian Orthodox Church was incorporated into the Russian Orthodox Church, but it regained its independence in 1917, after the fall of the TsarTsar

Tsar is a title used to designate certain European Slavic monarchs or supreme rulers. As a system of government in the Tsardom of Russia and Russian Empire, it is known as Tsarist autocracy, or Tsarism...

. Nevertheless, the Russian Orthodox Church did not officially recognize its independence until 1943.

Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church

The Ukrainian AOC separated from the Russian Orthodox Church in 1919, when the short-lived Ukrainian state adopted a decree declaring autocephaly from the Ukrainian Orthodox Church. Its independence was reaffirmed by the Bolsheviks in the Ukrainian Republic, and by 1924 it had 30 bishops, almost 1,500 priests, nearly 1,100 parishes, and between 3 and 6 million members.From its inception, the Ukrainian AOC faced the hostility of the Russian Orthodox Church in the Ukrainian Republic. In the late 1920s, Soviet authorities accused it of nationalist tendencies. In 1930 the government forced the church to reorganize as the "Ukrainian Orthodox Church", and few of its parishes survived until 1936. Nevertheless, the Ukrainian AOC continued to function outside the borders of the Soviet Union, and it was revived on Ukrainian territory under the German occupation during World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

. In the late 1980s, some of the Orthodox faithful in the Ukrainian Republic appealed to the Soviet government to reestablish the Ukrainian AOC.

Armenian Apostolic

The Armenian Apostolic ChurchArmenian Apostolic Church

The Armenian Apostolic Church is the world's oldest National Church, is part of Oriental Orthodoxy, and is one of the most ancient Christian communities. Armenia was the first country to adopt Christianity as its official religion in 301 AD, in establishing this church...

is an independent Oriental Orthodox church. In the 1980s it had about 4 million adherents – almost the entire population of Armenia. It was permitted 6 bishops, between 50 and 100 priests, and between 20 and 30 churches, and it had one theological seminary and six monasteries.

Catholic

Catholics formed a substantial and active religious constituency in the Soviet Union. Their number increased dramatically with the annexation of territories of the Second Polish RepublicPolish areas annexed by the Soviet Union

Immediately after the German invasion of Poland in 1939, which marked the beginning of World War II, the Soviet Union invaded the eastern regions of the Second Polish Republic, which Poles referred to as the "Kresy," and annexed territories totaling 201,015 km² with a population of 13,299,000...

in 1939 and the Baltic republics in 1940. Catholics in the Soviet Union were divided between those belonging to the Roman Catholic Church

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

, which was recognized by the government, and those remaining loyal to the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church

Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church

The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church , Ukrainska Hreko-Katolytska Tserkva), is the largest Eastern Rite Catholic sui juris particular church in full communion with the Holy See, and is directly subject to the Pope...

, banned since 1946.

Roman Catholic Church

The majority of the 5.5 million Roman Catholics in the Soviet Union lived in the Lithuanian, Belarusian, and Latvian republics, with a sprinkling in the Moldavian, Ukrainian, and Russian republics. Since World War II, the most active Roman Catholic Church in the Soviet Union was in the Lithuanian Republic, where the majority of people are Catholics. The Roman Catholic Church there has been viewed as an institution that both fosters and defends Lithuanian national interests and values. Since 1972 a Catholic underground publication, The Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania, has spoken not only for Lithuanians' religious rights but also for their national rights.Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church

Western Ukraine, which included largely the historic region of Galicia, became part of the Soviet Union in 1939. Although Ukrainian, its population was never part of the Russian EmpireRussian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

, but was Eastern Rite Catholic. After the Second World War, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church

Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church

The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church , Ukrainska Hreko-Katolytska Tserkva), is the largest Eastern Rite Catholic sui juris particular church in full communion with the Holy See, and is directly subject to the Pope...

identified closely with the nationalist aspirations of the region, arousing the hostility of the Soviet government, which was in combat with Ukrainian Insurgency. In 1945, Soviet authorities arrested the church's Metropolitan Josyf Slipyj, nine bishops and hundreds of clergy and leading lay activists, and deported them to forced labor camps in Siberia and elsewhere. The nine bishops and many of the clergy died in prisons, concentration camps, internal exile, or soon after their release during the post-Stalin thaw, but after 18 years of imprisonment and persecution, Metropolitan Slipyj was released when Pope John XXIII

Pope John XXIII

-Papal election:Following the death of Pope Pius XII in 1958, Roncalli was elected Pope, to his great surprise. He had even arrived in the Vatican with a return train ticket to Venice. Many had considered Giovanni Battista Montini, Archbishop of Milan, a possible candidate, but, although archbishop...

intervened on his behalf. Slipyj went to Rome, where he received the title of Major Archbishop of Lviv, and became a cardinal in 1965.

In 1946 a synod was called in Lviv

Lviv

Lviv is a city in western Ukraine. The city is regarded as one of the main cultural centres of today's Ukraine and historically has also been a major Polish and Jewish cultural center, as Poles and Jews were the two main ethnicities of the city until the outbreak of World War II and the following...

, where, despite being uncanonical in both Catholic and Orthodox understanding, the Union of Brest

Union of Brest

Union of Brest or Union of Brześć refers to the 1595-1596 decision of the Church of Rus', the "Metropolia of Kiev-Halych and all Rus'", to break relations with the Patriarch of Constantinople and place themselves under the Pope of Rome. At the time, this church included most Ukrainians and...

was annulled, and the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church was officially annexed to the Russian Orthodox Church. St. George's Cathedral

St. George's Cathedral, Lviv

St. George's Cathedral is a baroque-rococo cathedral located in the city of Lviv, the historic capital of western Ukraine. It was constructed between 1744-1760 on a hill overlooking the city. This is the third manifestation of a church to inhabit the site since the 13th century, and its prominence...

in Lviv became the throne of Russian Orthodox Archbishop Makariy.

For the clergy that joined the Russian Orthodox Church, the Soviet authorities refrained from the large-scale persecution seen elsewhere. In Lviv only one church was closed. In fact, the western dioceses of Lviv-Ternopil and Ivano-Frankivsk were the largest in the USSR. Canon law was also relaxed, allowing the clergy to shave their beards (a practice uncommon in Orthodoxy) and to conduct services in Ukrainian instead of Slavonic.

In 1989 the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church was officially re-established after a catacomb period of more than 40 years. There followed conflicts between Orthodox and Catholic Christians regarding the ownership of church buildings, conflicts which continued into the 1990s, after the Independence of Ukraine.

Protestantism

By 1950 it was estimated that there were 2 million Baptists in the Soviet Union, with the largest number in Ukraine.Many Protestants fell victim to communist persecution, including imprisonment and execution. Vladimir Shelkov

Vladimir Shelkov

Vladimir Shelkov was a Christian preacher and Seventh-day Adventist leader in the former Soviet Union. He headed the Church of True and Free Seventh-day Adventists, which rejected any government interference in the activities....

(1895–1980), the leader of the unregistered Seventh-day Adventist

Seventh-day Adventist Church

The Seventh-day Adventist Church is a Protestant Christian denomination distinguished by its observance of Saturday, the original seventh day of the Judeo-Christian week, as the Sabbath, and by its emphasis on the imminent second coming of Jesus Christ...

movement in the Soviet Union, spent almost all his life from 1931 on in prison; he died in Yakutia camp. Large numbers of Pentecostals were imprisoned, and many died there, including Ivan Voronaev

Ivan Voronaev

Ivan Yefimovitch Voronaev – leader and founder of Pentecostal movement in Russia, Ukraine and the former USSR. He was born about 1885 in Orenburg....

, one of their leaders.

In the period after the Second World War, Protestants in the USSR (Baptists, Pentecostals, Adventists and others) were sent to mental hospitals or tried and imprisoned, often for refusal to enter military service. Some were deprived of their parental rights.

The Lutheran Church in different regions of the country was persecuted during the Soviet era, and church property was confiscated. Many of its members and pastors were oppressed, and some were forced to emigrate.

According to western sources, various Protestant religious groups collectively had as many as 5 million followers in the 1980s. Evangelical Christian Baptists constituted the largest Protestant group. Spread throughout the Soviet Union, some congregations were registered with the government and functioned with official approval. Many other unregistered congregations carried on religious activity without such approval.

Lutherans, the second largest Protestant group, lived for the most part in the Latvian and Estonian republics. In the 1980s, Lutheran churches in these republics identified to some extent with nationality issues in the two republics. The regime's attitude toward Lutherans was generally benign.

Other Christian groups

A number of congregations of Russian Mennonites, Jehovah's Witnesses, and other Christian groups existed in the Soviet Union. Nearly 9000 Jehovah's Witnesses were deported to Siberia in 1951 (numbers of those missed in deportation unknown). The number of Jehovah's Witnesses increased greatly over this period, with a KGB estimate of around 20,000 in 1968. Russian Mennonites began to emigrate from the Soviet Union in the face of increasing violence and persecution, state restrictions on freedom of religion, and biased allotments of communal farmland. They emigrated to Germany, Britain, The United States, parts of South AmericaSouth America

South America is a continent situated in the Western Hemisphere, mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere. The continent is also considered a subcontinent of the Americas. It is bordered on the west by the Pacific Ocean and on the north and east...

, and other regions.

Islam

Mosque

A mosque is a place of worship for followers of Islam. The word is likely to have entered the English language through French , from Portuguese , from Spanish , and from Berber , ultimately originating in — . The Arabic word masjid literally means a place of prostration...

s, a fraction of the number in prerevolutionary Russia, and Soviet law forbade Islamic religious activity outside working mosques and Islamic schools.

All working mosques, religious schools, and Islamic publications were supervised by four "spiritual directorates" established by Soviet authorities to provide government control. The Spiritual Directorate for Central Asia and Kazakhstan

Spiritual Administration of the Muslims of Central Asia and Kazakhstan

The Spiritual Administration of the Muslims of Central Asia and Kazakhstan , abbreviated as SADUM was the official governing body for Islamic activities in the five Central Asian republics of the Soviet Union. Under strict state control, SADUM was charged with training clergy and publishing...

, the Spiritual Directorate for the European Soviet Union and Siberia, and the Spiritual Directorate for the Northern Caucasus and Dagestan

Dagestan

The Republic of Dagestan is a federal subject of Russia, located in the North Caucasus region. Its capital and the largest city is Makhachkala, located at the center of Dagestan on the Caspian Sea...

oversaw the religious life of Sunni Muslims. The Spiritual Directorate for Transcaucasia dealt with both Sunni Muslims and Shia Muslims. The overwhelming majority of the Muslims were Sunnis.

Soviet Muslims differed linguistically and culturally from each other, speaking about fifteen Turkic languages

Turkic languages

The Turkic languages constitute a language family of at least thirty five languages, spoken by Turkic peoples across a vast area from Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean to Siberia and Western China, and are considered to be part of the proposed Altaic language family.Turkic languages are spoken...

, ten Iranian languages

Iranian languages

The Iranian languages form a subfamily of the Indo-Iranian languages which in turn is a subgroup of Indo-European language family. They have been and are spoken by Iranian peoples....

, and thirty Caucasian languages. Hence, communication between different Muslim groups was difficult. Although in 1989 Russian often served as a lingua franca among some educated Muslims, few were fluent in Russian.

Culturally, some Muslim groups had highly developed urban traditions, whereas others were recently nomadic. Some lived in industrialized environments, others in isolated mountainous regions. In sum, Muslims were not a homogeneous group with a common national identity and heritage, although they shared the same religion and the same country.

In the late 1980s, unofficial Muslim congregations, meeting in tea houses and private homes with their own mullah

Mullah

Mullah is generally used to refer to a Muslim man, educated in Islamic theology and sacred law. The title, given to some Islamic clergy, is derived from the Arabic word مَوْلَى mawlā , meaning "vicar", "master" and "guardian"...

s, greatly outnumbered those in the officially sanctioned mosques. The unofficial mullahs were either self-taught or informally trained by other mullahs. In the late 1980s, unofficial Islam appeared to split into fundamentalist congregations and groups that emphasized Sufism

Sufism

Sufism or ' is defined by its adherents as the inner, mystical dimension of Islam. A practitioner of this tradition is generally known as a '...

.

Policy toward religions in practice

Soviet policy toward religion was based on the ideology of Marxism-LeninismMarxism-Leninism

Marxism–Leninism is a communist ideology, officially based upon the theories of Marxism and Vladimir Lenin, that promotes the development and creation of a international communist society through the leadership of a vanguard party over a revolutionary socialist state that represents a dictatorship...

, which made atheism the official doctrine of the Communist Party. However, "the Soviet law and administrative practice through most of the 1920s extended some tolerance to religion and forbade the arbitrary closing or destruction of some functioning churches", and each successive Soviet constitution granted freedom of belief. As the founder of the Soviet state, Lenin, put it:

Religion is the opium of the people: this saying of Marx is the cornerstone of the entire ideology of Marxism about religion. All modern religions and churches, all and of every kind of religious organizations are always considered by Marxism as the organs of bourgeois reaction, used for the protection of the exploitation and the stupefaction of the working class.

Marxism-Leninism advocates the suppression and ultimately the disappearance of religious beliefs, considering them to be "unscientific" and "superstitious". In the 1920s and 1930s, such organizations as the League of the Militant Godless were active in anti-religious propaganda. Atheism was the norm in schools, communist organizations (such as the Young Pioneer Organization

Young Pioneer organization of the Soviet Union

The Young Pioneer Organization of the Soviet Union, also Vladimir Lenin All-Union Pioneer Organization The Young Pioneer Organization of the Soviet Union, also Vladimir Lenin All-Union Pioneer Organization The Young Pioneer Organization of the Soviet Union, also Vladimir Lenin All-Union Pioneer...

), and the media.

The regime's efforts to eradicate religion in the Soviet Union, however, varied over the years with respect to particular religions and were affected by higher state interests. In 1923, a New York Times correspondent saw Christians observing Easter peacefully in Moscow despite violent anti-religious actions in previous years. Official policies and practices not only varied with time, but also differed in their application from one nationality to another and from one religion to another.

In 1929, with the onset of the Cultural Revolution in the Soviet Union and an upsurge of radical militancy in the Party and KomsomolKomsomolThe Communist Union of Youth , usually known as Komsomol , was the youth division of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The Komsomol in its earliest form was established in urban centers in 1918. During the early years, it was a Russian organization, known as the Russian Communist Union of...

, a powerful "hard line" in favor of mass closing of churches and arrests of priests became dominant and evidently won Stalin's approval. Secret "hard line" instructions were issued to local party organizations, but not published. When the anti-religious drive inflamed the anger of the rural population, not to mention that of the Pope and other Western church spokesmen, the regime was able to back off from a policy that it had never publicly endorsed anyway.

Although all Soviet leaders had the same long-range goal of developing a cohesive Soviet people, they pursued different policies to achieve it. For the Soviet regime, questions of nationality and religion were always closely linked. Therefore their attitude toward religion also varied from a total ban on some religions to official support of others.

Policy towards nationalities and religion

In theory, the Soviet Constitution described the regime's position regarding nationalities and religions. It stated that every Soviet citizen also had a particular nationality, and every Soviet passport carried these two entries. The constitution granted a large degree of local autonomy, but this autonomy was subordinated to central authority. In addition, because local and central administrative structures were often not clearly divided, local autonomy was further weakened. Although under the Constitution all nationalities were equal, in practice they were not treated so. Only fifteen nationalities had union republic status, which granted them, in principle, many rights, including the right to secede from the union.Twenty-two nationalities lived in autonomous republics with a degree of local self-government and representation in the Council of Nationalities in the Supreme Soviet. Eighteen more nationalities had territorial enclaves (autonomous oblast

Oblast

Oblast is a type of administrative division in Slavic countries, including some countries of the former Soviet Union. The word "oblast" is a loanword in English, but it is nevertheless often translated as "area", "zone", "province", or "region"...

s and autonomous okrug

Okrug

Okrug is an administrative division of some Slavic states. The word "okrug" is a loanword in English, but it is nevertheless often translated as "area", "district", or "region"....

s) but had very few powers of self-government. The remaining nationalities had no right of self-government at all. Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

's 1913 definition of a nation as "a historically constituted and stable community of people formed on the basis of common language, territory, economic life, and psychological makeup revealed in a common culture" was retained by Soviet authorities throughout the 1980s. However, in granting nationalities union republic status, three additional factors were considered: a population of at least 1 million, territorial compactness, and location on the borders of the Soviet Union.

Although Lenin believed that eventually all nationalities would merge into one, he insisted that the Soviet Union be established as a federation of formally equal nations. In the 1920s, genuine cultural concessions were granted to the nationalities. Communist elites of various nationalities were permitted to flourish and to have considerable self-government. National cultures, religions, and languages were not merely tolerated but, in areas with Muslim populations, encouraged.

Demographic changes in the 1960s and 1970s whittled down the overall Russian majority, but they also caused two nationalities (the Kazakhs and Kirgiz) to become minorities in their own republics at the time of the 1979 census, and considerably reduced the majority of the titular nationalities in other republics. This situation led Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev – 10 November 1982) was the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union , presiding over the country from 1964 until his death in 1982. His eighteen-year term as General Secretary was second only to that of Joseph Stalin in...

to declare at the 24th Communist Party Congress in 1971 that the process of creating a unified Soviet people had been completed, and proposals were made to abolish the federative system and replace it with a single state. In the 1970s, however, a broad movement of national dissent began to spread throughout the Soviet Union. It manifestated itself in many ways: Jews insisted on their right to emigrate to Israel; Crimean Tatars

Crimean Tatars

Crimean Tatars or Crimeans are a Turkic ethnic group that originally resided in Crimea. They speak the Crimean Tatar language...

demanded to be allowed to return to Crimea; Lithuanians called for the restoration of the rights of the Catholic Church; and Helsinki Watch

Helsinki Watch

Helsinki Watch was a private American NGO devoted to monitoring Helsinki implementation throughout the Soviet bloc. It was created in 1978 to monitor compliance to the Helsinki Final Act...

groups were established in the Georgian, Lithuanian, and Ukrainian republics. Petitions, literature, and occasional public demonstrations voiced public demands for the human rights of all nationalities. By the end of the 1970s, however, massive and concerted efforts by the KGB

KGB

The KGB was the commonly used acronym for the . It was the national security agency of the Soviet Union from 1954 until 1991, and was the premier internal security, intelligence, and secret police organization during that time.The State Security Agency of the Republic of Belarus currently uses the...

had largely suppressed the national dissent movement. Nevertheless, Brezhnev had learned his lesson. Proposals to dismantle the federative system were abandoned in favour of a policy of drawing the nationalities together more gradually.

Soviet officials identified religion closely with nationality. The implementation of policy toward a particular religion, therefore, depended on the regime's perception of the bond between that religion and the nationality practicing it, the size of the religious community, the extent to which the religion accepted outside authority, and the nationality's willingness to subordinate itself to political authority. Thus the smaller the religious community and the more closely it identified with a particular nationality, the more restrictive were the regime's policies, especially if the religion also recognized a foreign authority such as the pope.

Policy towards Orthodoxy

Such crackdowns related to many people's dissatisfaction with the church in pre-revolutionary Russia. The close ties between the church and the state led to the perception of the church as corrupt and greedy by many members of the intelligentsia

Intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a social class of people engaged in complex, mental and creative labor directed to the development and dissemination of culture, encompassing intellectuals and social groups close to them...

. Many peasant

Peasant

A peasant is an agricultural worker who generally tend to be poor and homeless-Etymology:The word is derived from 15th century French païsant meaning one from the pays, or countryside, ultimately from the Latin pagus, or outlying administrative district.- Position in society :Peasants typically...

s, while highly religious, also viewed the church unfavorably. Respect for religion did not extend to the local priests. The church owned a significant portion of Russia's land, and this was a bone of contention – land ownership was a big factor in the Russian Revolution of 1917

Russian Revolution of 1917

The Russian Revolution is the collective term for a series of revolutions in Russia in 1917, which destroyed the Tsarist autocracy and led to the creation of the Soviet Union. The Tsar was deposed and replaced by a provisional government in the first revolution of February 1917...

.

The Nazi

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

attack on the Soviet Union in 1941 forced Stalin to enlist the Russian Orthodox Church as an ally to arouse Russian patriotism against foreign aggression. Russian Orthodox religious life experienced a revival: thousands of churches were reopened; there were 22,000 by the time Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev led the Soviet Union during part of the Cold War. He served as First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964, and as Chairman of the Council of Ministers, or Premier, from 1958 to 1964...

came to power. The regime permitted religious publications, and church membership grew.

Khrushchev reversed the regime's policy of cooperation with the Russian Orthodox Church. Although it remained officially sanctioned, in 1959 Khrushchev launched an antireligious

Antireligion

Antireligion is opposition to religion. Antireligion is distinct from atheism and antitheism , although antireligionists may be atheists or antitheists...

campaign that was continued in a less stringent manner by his successor, Brezhnev. By 1975 the number of active Russian Orthodox churches was reduced to 7,000. Some of the most prominent members of the Russian Orthodox hierarchy and some activists were jailed or forced to leave the church. Their place was taken by docile clergy who were obedient to the state and who were sometimes infiltrated by KGB agents, making the Russian Orthodox Church useful to the regime. It espoused and propagated Soviet foreign policy and furthered the russification of non-Russian Christians, such as Orthodox Ukrainians and Belarusians.

The regime applied a different policy toward the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church and the Belarusian Autocephalous Orthodox Church. Viewed by the government as very nationalistic, both were suppressed, first at the end of the 1920s and again in 1944 after they had renewed themselves under German occupation. The leadership of both churches was decimated; large numbers of priests were shot or sent to labor camps, and members of their congregations were harassed and persecuted.

The Georgian Orthodox Church was subject to a somewhat different policy and fared far worse than the Russian Orthodox Church. During World War II, however, it was allowed greater autonomy in running its affairs in return for calling its members to support the war effort, although it did not achieve the kind of accommodation with the authorities that the Russian Orthodox Church had. The government reimposed tight control over it after the war. Out of some 2,100 churches in 1917, only 200 were still open in the 1980s, and it was forbidden to serve its adherents outside the Georgian Republic. In many cases, the regime forced the Georgian Orthodox Church to conduct services in Old Church Slavonic instead of in the Georgian language.

Policy towards Catholicism and Protestantism

The Soviet government's policies toward the Catholic Church were strongly influenced by Soviet Catholics' recognition of an outside authority as head of their church. As a result of World War II, millions of Catholics (including Greco-Catholics) became Soviet citizens and were subjected to new repression. Also, in the three republics where most of the Catholics lived, the Lithuanian SSRLithuanian SSR

The Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic , also known as the Lithuanian SSR, was one of the republics that made up the former Soviet Union...

, the Byelorussian SSR

Byelorussian SSR

The Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic was one of fifteen constituent republics of the Soviet Union. It was one of the four original founding members of the Soviet Union in 1922, together with the Ukrainian SSR, the Transcaucasian SFSR and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic...

and the Ukrainian SSR

Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic or in short, the Ukrainian SSR was a sovereign Soviet Socialist state and one of the fifteen constituent republics of the Soviet Union lasting from its inception in 1922 to the breakup in 1991...

, Catholicism and nationalism were closely linked. Although the Roman Catholic Church was tolerated in Lithuania, large numbers of the clergy were imprisoned, many seminaries were closed, and police agents infiltrated the remainder. The anti-Catholic campaign in Lithuania abated after Stalin's death, but harsh measures against the church were resumed in 1957 and continued through the Brezhnev era.

Soviet policy was particularly harsh toward the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church. Ukrainian Greek-Catholics came under Soviet rule in 1939, when western Ukraine was incorporated into the Soviet Union as part of the Nazi-Soviet Nonaggression Pact. Although the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church was permitted to function, it was almost immediately subjected to intense harassment. Retreating before the German army in 1941, Soviet authorities arrested large numbers of Ukrainian Greek Catholic priests, who were either killed or deported to Siberia. After the Red Army reoccupied western Ukraine in 1944, the Soviet regime liquidated the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church by arresting its metropolitan, all of its bishops, hundreds of clergy, and the more active church members, killing some and sending the rest to labor camps. At the same time, Soviet authorities forced the remaining clergy to abrogate the union with Rome and subordinate themselves to the Russian Orthodox Church.

Before World War II, there were fewer Protestants in the Soviet Union than adherents of other faiths, but they showed remarkable growth since then. In 1944 the Soviet government established the All-Union Council of Evangelical Christian Baptists (now the Union of Evangelical Christians-Baptists of Russia

Union of Evangelical Christians-Baptists of Russia

The Union of Evangelical Christians-Baptists of Russia is part of the large family of Evangelical Christian Baptists, a Protestant evangelical movement which began in the Russian Empire, in the midst of the Orthodox establishment. It originally attracted peasants, urban artisans, the lower...

) to gain some control over the various Protestant sects. Many congregations refused to join this body, however, and others that initially joined it subsequently left. All found that the state, through the council, was interfering in church life.

Policy Toward Other Christian Groups

A number of congregations of Russian Mennonites, Jehovah's Witnesses, and other Christian groups faced varying levels of persecution under Soviet rule.Jehovah's Witnesses were banned from practicing their religion. Under Operation North

Operation North

Operation North was the code name assigned by the USSR Ministry of State Security to massive deportation of the members of the Jehovah's Witnesses and their families to Siberia in the Soviet Union on 1–2 April 1951.-Background:...

, the personal property of over eight-thousand members was confiscated, and they (along with underage children) were exiled to Siberia from 1951 until repeal in 1965. All were asked to sign a declaration of resignation as a Jehovah's Witness in order to not be deported. There is no existing record of any having signed this declaration. While in Siberia, some men, women, and children were forced to work as lumberjacks for a fixed wage. Victims reported living conditions to be very poor. From 1951 to 1991, Jehovah's Witnesses within and outside Siberia were incarcerated – and then rearrested after serving their terms. Some were forced to work in concentration camps, others forcibly enrolled in Marxist reeducation

Reeducation through labor

Re-education through labor , abbreviated is a system of administrative detentions in the People's Republic of China which is generally used to detain persons for minor crimes such as petty theft, prostitution, and trafficking illegal drugs, as well as religious or political dissidents such as...

programs. KGB officials infiltrated the Jehovah's Witnesses organization in the Soviet Union, mostly to seek out hidden caches of theological literature. Soviet propaganda

Propaganda

Propaganda is a form of communication that is aimed at influencing the attitude of a community toward some cause or position so as to benefit oneself or one's group....

films depicted Jehovah's Witnesses as a cult

Cult

The word cult in current popular usage usually refers to a group whose beliefs or practices are considered abnormal or bizarre. The word originally denoted a system of ritual practices...

, extremist, and engaging in mind control

Mind control

Mind control refers to a process in which a group or individual "systematically uses unethically manipulative methods to persuade others to conform to the wishes of the manipulator, often to the detriment of the person being manipulated"...

. Jehovah's Witnesses were legalized in the Soviet Union in 1991; victims were given social benefits equivalent to those of war veterans.

Early in the Bolshevik period, predominantly before the end of the Russian Civil War

Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War was a multi-party war that occurred within the former Russian Empire after the Russian provisional government collapsed to the Soviets, under the domination of the Bolshevik party. Soviet forces first assumed power in Petrograd The Russian Civil War (1917–1923) was a...

and the emergence of the Soviet Union, Russian Mennonite communities were harassed; several Mennonites were killed or imprisoned, and women were raped. Anarcho-Communist Nestor Makhno

Nestor Makhno

Nestor Ivanovych Makhno or simply Daddy Makhno was a Ukrainian anarcho-communist guerrilla leader turned army commander who led an independent anarchist army in Ukraine during the Russian Civil War....

was responsible for most of the bloodshed, which caused the normally pacifist Mennonites to take up arms in defensive militia units. This marked the beginning of a mass exodus of Mennonites to Germany, the United States, and elsewhere. Mennonites were branded as kulaks by the Soviets. Their colonies' farms were collectivized under the Soviet Union's communal farming policy. Being predominantly German settlers, the Russian Mennonites in World War II saw the German forces invading Russia as liberators. Many were allowed passage to Germany as Volksdeutsche

Volksdeutsche

Volksdeutsche - "German in terms of people/folk" -, defined ethnically, is a historical term from the 20th century. The words volk and volkische conveyed in Nazi thinking the meanings of "folk" and "race" while adding the sense of superior civilization and blood...

. Soviet officials began exiling Mennonite settlers in the eastern part of Russia to Siberia. After the war, the remaining Russian Mennonites were branded as Nazi conspirators and exiled to Kazakhstan and Siberia, sometimes being imprisoned or forced to work in concentration camps. In the 1990s the Russian government gave the Mennonites in Kazakhstan and Siberia the opportunity to emigrate.

Policy towards Islam

Soviet policy toward Islam was affected, on the one hand by the large Muslim population, its close ties to national cultures, and its tendency to accept Soviet authority, and on the other hand by its susceptibility to foreign influence. Although actively encouraging atheism, Soviet authorities permitted some limited religious activity in all the Muslim republics, under the auspices of the regional branches of the Spiritual Administration of the Muslims of the USSR. Mosques functioned in most large cities of the Central Asian republics and the Azerbaijan Republic, but their number decreased from 25,000 in 1917 to 500 in the 1970s. Under Stalinist rule, Soviet authorities cracked down on Muslim clergy, closing many mosques or turning them into warehouses. In 1989, as part of the general relaxation of restrictions on religions, some additional Muslim religious associations were registered, and some of the mosques that had been closed by the government were returned to Muslim communities. The government also announced plans to permit the training of limited numbers of Muslim religious leaders in two- and five-year courses in Ufa and Baku, respectively.Policy towards Judaism

Although Lenin found ethnic anti-SemitismAnti-Semitism

Antisemitism is suspicion of, hatred toward, or discrimination against Jews for reasons connected to their Jewish heritage. According to a 2005 U.S...

abhorrent, the regime was hostile toward Judaism

Judaism

Judaism ) is the "religion, philosophy, and way of life" of the Jewish people...

from the beginning. In 1919 the Soviet authorities abolished Jewish community councils, which were traditionally responsible for maintaining synagogues. They created a special Jewish section of the party

Yevsektsiya

Yevsektsiya , , the abbreviation of the phrase "Еврейская секция" was the Jewish section of the Soviet Communist party. Yevsektsiya was established to popularize Marxism and encourage loyalty to the Soviet regime among Russian Jews. The founding conference of Yevsektsiya took place on October 20,...

, whose tasks included propaganda against Jewish clergy and religion. To offset Jewish national and religious aspirations, and to reflect the Zionist heritage within the Jewish intelligentsia of the Russian Empire (for example, Trotsky was first a member of the Jewish Bund, not the Social Democratic Labour Party

Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party , also known as Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party or Russian Social Democratic Party, was a revolutionary socialist Russian political party formed in 1898 in Minsk to unite the various revolutionary organizations into one party...

), an alternative to the Land of Israel

Land of Israel

The Land of Israel is the Biblical name for the territory roughly corresponding to the area encompassed by the Southern Levant, also known as Canaan and Palestine, Promised Land and Holy Land. The belief that the area is a God-given homeland of the Jewish people is based on the narrative of the...

was established in 1934.

The Jewish Autonomous Oblast

Jewish Autonomous Oblast

The Jewish Autonomous Oblast is a federal subject of Russia situated in the Russian Far East, bordering Khabarovsk Krai and Amur Oblast of Russia and Heilongjiang province of China. Its administrative center is the town of Birobidzhan....

, created in 1928 by Stalin, with Birobidzhan

Birobidzhan

Birobidzhan is a town and the administrative center of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast, Russia. It is located on the Trans-Siberian railway, close to the border with the People's Republic of China....

in the Russian Far East

Russian Far East

Russian Far East is a term that refers to the Russian part of the Far East, i.e., extreme east parts of Russia, between Lake Baikal in Eastern Siberia and the Pacific Ocean...

as its administratice center, was to become a "Soviet Zion". Yiddish

Yiddish language

Yiddish is a High German language of Ashkenazi Jewish origin, spoken throughout the world. It developed as a fusion of German dialects with Hebrew, Aramaic, Slavic languages and traces of Romance languages...

, rather than "reactionary" Hebrew

Hebrew language

Hebrew is a Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Culturally, is it considered by Jews and other religious groups as the language of the Jewish people, though other Jewish languages had originated among diaspora Jews, and the Hebrew language is also used by non-Jewish groups, such...

, would be the national language, and proletarian socialist literature and arts

Socialist realism

Socialist realism is a style of realistic art which was developed in the Soviet Union and became a dominant style in other communist countries. Socialist realism is a teleologically-oriented style having its purpose the furtherance of the goals of socialism and communism...

would replace Judaism as the quintessence of its culture. Despite a massive domestic and international state propaganda campaign, the Jewish population there never reached 30% (as of 2003 it was only about 1.2%). The experiment ended in the mid-1930s, during Stalin's first campaign of purges. Jewish leaders were arrested and executed, and Yiddish schools were shut down. Further persections and purges followed.

The training of rabbis became impossible, and until the late 1980s only one Yiddish periodical was published. Because of its identification with Zionism, Hebrew was taught only in schools for diplomats. Most of the 5,000 synagogues functioning prior to the Bolshevik Revolution were closed under Stalin, and others were closed under Khrushchev. The practice of Judaism became very difficult, intensifying the desire of Jews to leave the Soviet Union.

See also

-

- Index of Soviet Union-related articles

- Council for Religious AffairsCouncil for Religious AffairsThe Council for Religious Affairs was a government council in the Soviet Union that dealt with religious activity in the country. It was founded in 1965 though the union of the Council for the Affairs of the Russian Orthodox Church and the Council for the Affairs of Religious Cults...

- Culture of the Soviet UnionCulture of the Soviet UnionThe Culture of the Soviet Union passed through several stages during the 69 year existence of the Soviet Union. It was contributed by people of various nationalities from every of 15 union republics, although the majority of them were Russians...

- Demographics of the Soviet UnionDemographics of the Soviet UnionAccording to data from the 1989 Soviet census, the population of the Soviet Union was 70% East Slavs, 12% Turkic peoples, and all other ethnic groups below 10%. Alongside the atheist majority of 60% there were sizable minorities of Russian Orthodox followers and Muslims According to data from the...