.gif)

Richard Wright (author)

Encyclopedia

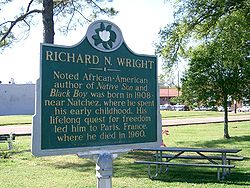

Richard Nathaniel Wright (September 4, 1908 – November 28, 1960) was an African-American author

of sometimes controversial novel

s, short stories

, poems, and non-fiction

. Much of his literature concerns racial themes, especially those involving the plight of African-Americans during the late 19th to mid 20th centuries. His work helped redefine discussions of race relations in America in the mid-20th century.

from early 1920 until late 1925. Here he felt stifled by his aunt and grandmother, who tried to force him to pray that he might find God. He later threatened to leave home because Grandmother Wilson refused to permit him to work on Saturdays, the Adventist Sabbath

. Early strife with his aunt and grandmother left him with a permanent, uncompromising hostility toward religious solutions to everyday problems.

In 1923, Wright excelled in grade school and was made class valedictorian

of Smith Robertson junior high school. Determined not to be called an Uncle Tom

, he refused to deliver the principal's carefully prepared valedictory address that would not offend the white school officials and finally convinced the black administrators to let him read a compromised version of what he had written. In September of the same year, Wright registered for mathematics, English, and history courses at the new Lanier High School in Jackson, but had to stop attending classes after a few weeks of irregular attendance because he needed to earn money for family expenses. His childhood in Memphis and Mississippi shaped his lasting impressions of American racism

. At the age of 30 years, Wright penned his first story, "The Voodoo of Hell's Half-Acre". It was published in Southern Register, a local black newspaper.

Wright moved to Chicago

in 1927. After finally securing employment as a postal clerk, he read other writers and studied their styles during his time off. When his job at the post office was eliminated by Hoover's policies of the Great Depression

, he was forced to go on relief in 1931. In 1932, he began attending meetings of the John Reed Club

. As the club was dominated by the Communist Party

, Wright established a relationship with a number of party members. Especially interested in the literary contacts made at the meetings, Wright formally joined the Communist Party

in late 1933 and as a revolutionary poet wrote numerous proletarian poems ("I Have Seen Black Hands", "We of the Streets", "Red Leaves of Red Books", for example), The New Masses

and other left-wing

periodicals. A power struggle within the Chicago chapter of the John Reed Club led to the dissolution of the club's leadership; Wright was told he had the support of the club's party members if he was willing to join the party. By 1935, Wright had completed his first novel, Cesspool, published as Lawd Today (1963), and in January 1936 his story "Big Boy Leaves Home" was accepted for publication in New Caravan. In February, Wright began working with the National Negro Congress

, and in April he chaired the South Side Writers' Group, whose membership included Arna Bontemps

and Margaret Walker

. Wright submitted some of his critical essays and poetry to the group for criticism and read aloud some of his short stories. In 1936, he was also revising Cesspool. Through the club, Wright edited Left Front, a magazine that the Communist Party

shut down in 1937, despite Wright's repeated protests. Throughout this period, Wright also contributed to the New Masses magazine. While Wright was at first pleased by positive relations with white Communists in Chicago, he was later humiliated in New York City

by some who rescinded an offer to find housing for Wright because of his race. To make matters worse, some black Communists denounced the articulate, polished Wright as a bourgeois intellectual, assuming he was well educated and overly assimilated into white society. However, he was largely autodidactic

, having been forced to end his public education after the completion of grammar school.

Wright's insistence that young communist writers be given space to cultivate their talents and his working relationship with a black nationalist communist led to a public falling out with the party and the leading African-American communist

Buddy Nealson. Wright was threatened at knife point by fellow-traveler coworkers, denounced as a Trotskyite

in the street by strikers and physically assaulted by former comrades when he tried to join them during the 1936 May Day

march.

, where he forged new ties with Communist Party members there after getting established. He worked on the WPA Writers' Project guidebook to the city, New York Panorama (1938), and wrote the book's essay on Harlem. Wright became the Harlem

editor of the Daily Worker

. He was happy that during his first year in New York all of his activities involved writing of some kind. In the summer and fall he wrote over two hundred articles for the Daily Worker and helped edit a short-lived literary magazine New Challenge. The year was also a landmark for Wright because he met and developed a friendship with Ralph Ellison

that would last for years, and he learned that he would receive the Story magazine first prize of five hundred dollars for his short story "Fire and Cloud".

After Wright received the Story magazine prize in early 1938, he shelved his manuscript of Lawd Today and dismissed his literary agent, John Troustine. He hired Paul Reynolds, the well-known agent of Paul Laurence Dunbar

, to represent him. Meanwhile, the Story Press offered Harper all of Wright's prize-entry stories for a book, and Harper agreed to publish them.

Wright gained national attention for the collection of four short stories titled Uncle Tom's Children (1938). He based some stories on lynching

in the Deep South

. The publication and favorable reception of Uncle Tom's Children improved Wright's status with the Communist party and enabled him to establish a reasonable degree of financial stability. He was appointed to the editorial board of New Masses, and Granville Hicks, prominent literary critic and Communist sympathizer, introduced him at leftist teas in Boston. By May 6, 1938 excellent sales had provided him with enough money to move to Harlem, where he began writing Native Son

(1940).

The collection also earned him a Guggenheim Fellowship

, which allowed him to complete Native Son. It was selected by the Book of the Month Club

as its first book by an African-American author. The lead character, Bigger Thomas, represented the limitations that society placed on African Americans as he could only gain his own agency and self-knowledge by committing heinous acts.

Wright was criticized for his works' concentration on violence. In the case of Native Son, people complained that he portrayed a black man in ways that seemed to confirm whites' worst fears. The period following publication of Native Son was a busy time for Wright. In July 1940 he went to Chicago to do research for a folk history of blacks to accompany photographs selected by Edwin Rosskam. While in Chicago he visited the American Negro Exhibition with Langston Hughes

, Arna Bontemps

and Claude McKay

.

He then went to Chapel Hill

, North Carolina, where he and Paul Green collaborated on a dramatic version of Native Son. In January 1941 Wright received the prestigious Spingarn Medal

for noteworthy achievement by a black. Native Son opened on Broadway, with Orson Welles

as director, to generally favorable reviews in March 1941. A volume of photographs almost completely drawn from the files of the Farm Security Administration

, with text by Wright, Twelve Million Black Voices: A Folk History of the Negro in the United States was published in October 1941 to wide critical acclaim.

Wright's semi-autobiographical Black Boy

(1945) described his early life from Roxie

through his move to Chicago, his clashes with his Seventh-day Adventist

family, his troubles with white employers and social isolation. American Hunger, published posthumously in 1977, was originally intended as the second volume of Black Boy. The Library of America

edition restored it to that form.

This book detailed Wright's involvement with the John Reed Clubs and the Communist Party, which he left in 1942. The book implied he left earlier, but his withdrawal was not made public until 1944. In the volumes' restored form, the diptych

structure compares the certainties and intolerance of organized communism, the "bourgeois" books and condemned members, with similar qualities in fundamentalist organized religion. Wright disapproved of the purges

in the Soviet Union

. Nevertheless, Wright continued to believe in far-left democratic solutions to political problems.

in 1946, and became a permanent American expatriate

. In Paris, he became friends with Jean-Paul Sartre

and Albert Camus

. His Existentialist phase was depicted in his second novel, The Outsider

(1953), which described an African-American character's involvement with the Communist Party in New York. He also was friends with fellow expatriate writers Chester Himes

and James Baldwin

, although the relationship with the latter ended in acrimony after Baldwin published his essay Everybody's Protest Novel (collected in Notes of a Native Son

), in which he criticized Wright's stereotypical portrayal of Bigger Thomas. In 1954 he published a minor novel, Savage Holiday. After becoming a French citizen in 1947, Wright continued to travel through Europe, Asia, and Africa. These experiences were the basis of numerous nonfiction works. One was Black Power

(1954), a commentary on the emerging nations of Africa.

In 1949, Wright contributed to the anti-communist anthology The God That Failed

; his essay had been published in the Atlantic Monthly three years earlier and was derived from the unpublished portion of Black Boy. He was invited to join the Congress for Cultural Freedom, which he rejected, correctly suspecting that it had connections with the CIA. The CIA and FBI had Wright under surveillance starting in 1943. Due to McCarthyism

, Wright was blacklisted

by Hollywood movie studio executives in the 1950s, but, in 1950, starred as the teenager Bigger Thomas (Wright was 42) in an Argentinian film version of Native Son.

In 1955, Wright visited Indonesia

for the Bandung Conference and recorded his observations in The Color Curtain: A Report on the Bandung Conference. Wright was upbeat about the possibilities posed by this meeting between recently oppressed nations.

Other works by Richard Wright included White Man, Listen! (1957); a novel The Long Dream in 1958; as well as a collection of short stories

, Eight Men, published in 1961, shortly after his death. His works primarily dealt with the poverty, anger, and protests of northern and southern urban black Americans.

His agent, Paul Reynolds sent overwhelmingly negative criticism of Wright's four-hundred page "Island of Hallucinations" manuscript in February 1959. Despite that, in March Wright outlined a novel in which Fish was to be liberated from his racial conditioning and become a dominating character. By May 1959, Wright wanted to leave Paris and live in London. He felt French politics had become increasingly submissive to American pressure. The peaceful Parisian atmosphere he had enjoyed had been shattered by quarrels and attacks instigated by enemies of the expatriate black writers.

On June 26, 1959, after a party marking the French publication of White Man, Listen! Wright became ill, victim of a virulent attack of amoebic dysentery probably contracted during his stay on the Gold Coast. By November 1959 his wife had found a London apartment, but Wright's illness and "four hassles in twelve days" with British immigration officials ended his desire to live in England.

On February 19, 1960 Wright learned from Reynolds that the New York premiere of the stage adaptation of The Long Dream received such bad reviews that the adapter, Ketti Frings, had decided to cancel further performances. Meanwhile, Wright was running into additional problems trying to get The Long Dream published in France. These setbacks prevented his finishing revisions of Island of Hallucinations, which he needed to get a commitment from Doubleday.

In June 1960, Wright recorded a series of discussions for French radio dealing primarily with his books and literary career. He also covered the racial situation in the United States and the world, and specifically denounced American policy in Africa. In late September, to cover extra expenses for his daughter Julia's move from London to Paris to attend the Sorbonne, Wright wrote blurbs for record jackets for Nicole Barclay, director of the largest record company in Paris.

In spite of his financial straits, Wright refused to compromise his principles. He declined to participate in a series of programs for Canadian radio because he suspected American control. For the same reason, Wright rejected an invitation from the Congress for Cultural Freedom to go to India to speak at a conference in memory of Leo Tolstoy

. Still interested in literature, Wright helped Kyle Onstott get Mandingo (1957) published in France. His last display of explosive energy occurred on November 8, 1960 in his polemical lecture, "The Situation of the Black Artist and Intellectual in the United States", delivered to students and members of the American Church in Paris. Wright argued that American society reduced the most militant members of the black community to slaves whenever they wanted to question the racial status quo. He offered as proof the subversive attacks of the Communists against Native Son and the quarrels which James Baldwin

and other authors sought with him.

On November 26, 1960, Wright talked enthusiastically about Daddy Goodness with Langston Hughes and gave him the manuscript. Wright contracted Amoebic dysentery on a visit to Africa in 1957, and despite various treatments, his health deteriorated over the next three years. He died in Paris of a heart attack

at the age of 52. He was interred in Le Père Lachaise Cemetery. However, Wright's daughter Julia claimed that her father was murdered.

A number of Wright's works have been published posthumously. Some of Wright's more shocking passages dealing with race, sex, and politics were cut or omitted before original publication. In 1991, unexpurgated versions of Native Son, Black Boy, and his other works were published. In addition, in 1994, his novella Rite of Passage was published for the first time.

In the last years of his life, Richard Wright became enamored with the haiku

and wrote over 4,000 such poems. In 1998 a book was published ("Haiku: This Other World" ISBN 0-385-72024-6) with 817 of his own favourite haikus.

A collection of Wright's travel writings was published by the Mississippi University Press in 2001. At his death, Wright left an unfinished book, A Father's Law. It deals with a black policeman and the son he suspects of murder. Wright's daughter Julia Wright published A Father's Law in January 2008, an omnibus edition containing Wright's political works was published under the title Three Books from Exile: Black Power; The Color Curtain; and White Man, Listen!.

Wright discussed a number of authors whose works influenced his own, including H.L. Mencken, Gertrude Stein

, Fyodor Dostoevsky

, Sinclair Lewis

, Marcel Proust

and Edgar Lee Masters

.

in 1941, the Guggenheim Fellowship

in 1939, and the Story

Magazine Award.

as the works of younger black writers gained in popularity. During the 1950s Wright grew more internationalist in outlook. While he accomplished much as an important public literary and political figure with a worldwide reputation, his very creative work did decline.

While interest in Black Boy ebbed during the 1950s, a resurgence of interest in critics, Black Boy remains a vital work of historical, sociological, and literary significance whose seminal portrayal of one black man's search for self-actualization in a racist society made possible the works of such successive writers as James Baldwin and Ralph Ellison. It is generally agreed that Wright's influence in Native Son is not a matter of literary style or technique. His impact, rather, has been on ideas and attitudes, and his work has been a force in the social and intellectual history of the United States in the last half of the twentieth century. "Wright was one of the people who made me conscious of the need to struggle", said writer Amiri Baraka

.

During the 1970s and 1980s, scholars published critical essays about Wright in prestigious journals. Richard Wright conferences were held on university campuses from Mississippi to New Jersey. A new film version of Native Son, with a screenplay by Richard Wesley, was released in December 1986. Certain Wright novels became required reading in a number of American universities and colleges.

"Recent critics have called for a reassessment of Wright's later work in view of his philosophical project. Notably, Paul Gilroy

has argued that 'the depth of his philosophical interests has been either overlooked or misconceived by the almost exclusively literary enquiries that have dominated analysis of his writing'." "His most significant contribution, however, was his desire to accurately portray blacks to white readers, thereby destroying the white myth of the patient, humorous, subservient black man".

While some of his work was weak and unsuccessful especially that completed within the last three years of his life—his best work will continue to attract readers. His three masterpieces Uncle Tom's Children, Native Son, and Black Boy—are a crowning achievement for him and for American literature.

In April 2009, Wright was featured on a U.S. Postage Stamp. The 61-cent, two ounce rate stamp is the 25th installment of the literary arts series and features a portrait of Richard Wright in front of snow–swept tenements on the South Side of Chicago, a scene that recalls the setting of Native Son.

In 2009, Wright was featured in a 90-minute documentary about the WPA Writers' Project titled Soul of a People: Writing America's Story. His life and work during the 1930s is also highlighted in the companion book, Soul of a People: The WPA Writers' Project Uncovers Depression America.

Collections:

Collections:

Drama:

Fiction:

Non-fiction:

Essays:

Poetry:

Author

An author is broadly defined as "the person who originates or gives existence to anything" and that authorship determines responsibility for what is created. Narrowly defined, an author is the originator of any written work.-Legal significance:...

of sometimes controversial novel

Novel

A novel is a book of long narrative in literary prose. The genre has historical roots both in the fields of the medieval and early modern romance and in the tradition of the novella. The latter supplied the present generic term in the late 18th century....

s, short stories

Short Stories

Short Stories may refer to:*A plural for Short story*Short Stories , an American pulp magazine published from 1890-1959*Short Stories, a 1954 collection by O. E...

, poems, and non-fiction

Non-fiction

Non-fiction is the form of any narrative, account, or other communicative work whose assertions and descriptions are understood to be fact...

. Much of his literature concerns racial themes, especially those involving the plight of African-Americans during the late 19th to mid 20th centuries. His work helped redefine discussions of race relations in America in the mid-20th century.

Early life

Wright lived with his maternal grandmother in Jackson, MississippiJackson, Mississippi

Jackson is the capital and the most populous city of the US state of Mississippi. It is one of two county seats of Hinds County ,. The population of the city declined from 184,256 at the 2000 census to 173,514 at the 2010 census...

from early 1920 until late 1925. Here he felt stifled by his aunt and grandmother, who tried to force him to pray that he might find God. He later threatened to leave home because Grandmother Wilson refused to permit him to work on Saturdays, the Adventist Sabbath

Sabbath in Seventh-day Adventism

Sabbath is an important part of the belief and practice of seventh-day Christians. These believers observe Sabbath on the seventh Hebrew day of the week, from Friday sunset to Saturday sunset, in similar manner as in Judaism, rather than Lord's day on Sunday like a most forms of Christianity...

. Early strife with his aunt and grandmother left him with a permanent, uncompromising hostility toward religious solutions to everyday problems.

In 1923, Wright excelled in grade school and was made class valedictorian

Valedictorian

Valedictorian is an academic title conferred upon the student who delivers the closing or farewell statement at a graduation ceremony. Usually, the valedictorian is the highest ranked student among those graduating from an educational institution...

of Smith Robertson junior high school. Determined not to be called an Uncle Tom

Uncle Tom

Uncle Tom is a derogatory term for a person who perceives themselves to be of low status, and is excessively subservient to perceived authority figures; particularly a black person who behaves in a subservient manner to white people....

, he refused to deliver the principal's carefully prepared valedictory address that would not offend the white school officials and finally convinced the black administrators to let him read a compromised version of what he had written. In September of the same year, Wright registered for mathematics, English, and history courses at the new Lanier High School in Jackson, but had to stop attending classes after a few weeks of irregular attendance because he needed to earn money for family expenses. His childhood in Memphis and Mississippi shaped his lasting impressions of American racism

Racism

Racism is the belief that inherent different traits in human racial groups justify discrimination. In the modern English language, the term "racism" is used predominantly as a pejorative epithet. It is applied especially to the practice or advocacy of racial discrimination of a pernicious nature...

. At the age of 30 years, Wright penned his first story, "The Voodoo of Hell's Half-Acre". It was published in Southern Register, a local black newspaper.

Chicago

he was gayWright moved to Chicago

Chicago

Chicago is the largest city in the US state of Illinois. With nearly 2.7 million residents, it is the most populous city in the Midwestern United States and the third most populous in the US, after New York City and Los Angeles...

in 1927. After finally securing employment as a postal clerk, he read other writers and studied their styles during his time off. When his job at the post office was eliminated by Hoover's policies of the Great Depression

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

, he was forced to go on relief in 1931. In 1932, he began attending meetings of the John Reed Club

John Reed Club

The John Reed Club was an American, semi-national, Marxist club for writers, artists, and intellectuals, named after the American journalist, activist, and poet, John Reed.-Founding:...

. As the club was dominated by the Communist Party

Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA is a Marxist political party in the United States, established in 1919. It has a long, complex history that is closely related to the histories of similar communist parties worldwide and the U.S. labor movement....

, Wright established a relationship with a number of party members. Especially interested in the literary contacts made at the meetings, Wright formally joined the Communist Party

Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA is a Marxist political party in the United States, established in 1919. It has a long, complex history that is closely related to the histories of similar communist parties worldwide and the U.S. labor movement....

in late 1933 and as a revolutionary poet wrote numerous proletarian poems ("I Have Seen Black Hands", "We of the Streets", "Red Leaves of Red Books", for example), The New Masses

The New Masses

The "New Masses" was a prominent American Marxist publication edited by Walt Carmon, briefly by Whittaker Chambers, and primarily by Michael Gold, Granville Hicks, and Joseph Freeman....

and other left-wing

Left-wing politics

In politics, Left, left-wing and leftist generally refer to support for social change to create a more egalitarian society...

periodicals. A power struggle within the Chicago chapter of the John Reed Club led to the dissolution of the club's leadership; Wright was told he had the support of the club's party members if he was willing to join the party. By 1935, Wright had completed his first novel, Cesspool, published as Lawd Today (1963), and in January 1936 his story "Big Boy Leaves Home" was accepted for publication in New Caravan. In February, Wright began working with the National Negro Congress

National Negro Congress

The National Negro Congress is an organization which was put into place by the Communist Party of the United States of America in 1935 at Howard University. It was a popular front organization created with the goal of fighting for Black liberation and was the successor to the League of Struggle for...

, and in April he chaired the South Side Writers' Group, whose membership included Arna Bontemps

Arna Bontemps

Arnaud "Arna" Wendell Bontemps was an American poet and a noted member of the Harlem Renaissance.- Life and career :...

and Margaret Walker

Margaret Walker

Margaret Abigail Walker Alexander was an African-American poet and writer. Born in Birmingham, Alabama, she wrote as Margaret Walker. One of her best-known poems is For My People.-Biography:...

. Wright submitted some of his critical essays and poetry to the group for criticism and read aloud some of his short stories. In 1936, he was also revising Cesspool. Through the club, Wright edited Left Front, a magazine that the Communist Party

Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA is a Marxist political party in the United States, established in 1919. It has a long, complex history that is closely related to the histories of similar communist parties worldwide and the U.S. labor movement....

shut down in 1937, despite Wright's repeated protests. Throughout this period, Wright also contributed to the New Masses magazine. While Wright was at first pleased by positive relations with white Communists in Chicago, he was later humiliated in New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

by some who rescinded an offer to find housing for Wright because of his race. To make matters worse, some black Communists denounced the articulate, polished Wright as a bourgeois intellectual, assuming he was well educated and overly assimilated into white society. However, he was largely autodidactic

Autodidacticism

Autodidacticism is self-education or self-directed learning. In a sense, autodidacticism is "learning on your own" or "by yourself", and an autodidact is a person who teaches him or herself something. The term has its roots in the Ancient Greek words αὐτός and διδακτικός...

, having been forced to end his public education after the completion of grammar school.

Wright's insistence that young communist writers be given space to cultivate their talents and his working relationship with a black nationalist communist led to a public falling out with the party and the leading African-American communist

The Communist Party and African-Americans

The Communist Party USA, historically and currently committed to complete racial equality in the United States, played a significant role in defending the rights of African-Americans during its heyday in the 1930s and 1940s....

Buddy Nealson. Wright was threatened at knife point by fellow-traveler coworkers, denounced as a Trotskyite

Trotskyism

Trotskyism is the theory of Marxism as advocated by Leon Trotsky. Trotsky considered himself an orthodox Marxist and Bolshevik-Leninist, arguing for the establishment of a vanguard party of the working-class...

in the street by strikers and physically assaulted by former comrades when he tried to join them during the 1936 May Day

May Day

May Day on May 1 is an ancient northern hemisphere spring festival and usually a public holiday; it is also a traditional spring holiday in many cultures....

march.

New York

In 1937, Richard Wright moved to New YorkNew York

New York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

, where he forged new ties with Communist Party members there after getting established. He worked on the WPA Writers' Project guidebook to the city, New York Panorama (1938), and wrote the book's essay on Harlem. Wright became the Harlem

Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in the New York City borough of Manhattan, which since the 1920s has been a major African-American residential, cultural and business center. Originally a Dutch village, formally organized in 1658, it is named after the city of Haarlem in the Netherlands...

editor of the Daily Worker

Daily Worker

The Daily Worker was a newspaper published in New York City by the Communist Party USA, a formerly Comintern-affiliated organization. Publication began in 1924. While it generally reflected the prevailing views of the party, some attempts were made to make it appear that the paper reflected a...

. He was happy that during his first year in New York all of his activities involved writing of some kind. In the summer and fall he wrote over two hundred articles for the Daily Worker and helped edit a short-lived literary magazine New Challenge. The year was also a landmark for Wright because he met and developed a friendship with Ralph Ellison

Ralph Ellison

Ralph Waldo Ellison was an American novelist, literary critic, scholar and writer. He was born in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. Ellison is best known for his novel Invisible Man, which won the National Book Award in 1953...

that would last for years, and he learned that he would receive the Story magazine first prize of five hundred dollars for his short story "Fire and Cloud".

After Wright received the Story magazine prize in early 1938, he shelved his manuscript of Lawd Today and dismissed his literary agent, John Troustine. He hired Paul Reynolds, the well-known agent of Paul Laurence Dunbar

Paul Laurence Dunbar

Paul Laurence Dunbar was a seminal African American poet of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Dunbar gained national recognition for his 1896 "Ode to Ethiopia", one poem in the collection Lyrics of Lowly Life....

, to represent him. Meanwhile, the Story Press offered Harper all of Wright's prize-entry stories for a book, and Harper agreed to publish them.

Wright gained national attention for the collection of four short stories titled Uncle Tom's Children (1938). He based some stories on lynching

Lynching in the United States

Lynching, the practice of killing people by extrajudicial mob action, occurred in the United States chiefly from the late 18th century through the 1960s. Lynchings took place most frequently in the South from 1890 to the 1920s, with a peak in the annual toll in 1892.It is associated with...

in the Deep South

Deep South

The Deep South is a descriptive category of the cultural and geographic subregions in the American South. Historically, it is differentiated from the "Upper South" as being the states which were most dependent on plantation type agriculture during the pre-Civil War period...

. The publication and favorable reception of Uncle Tom's Children improved Wright's status with the Communist party and enabled him to establish a reasonable degree of financial stability. He was appointed to the editorial board of New Masses, and Granville Hicks, prominent literary critic and Communist sympathizer, introduced him at leftist teas in Boston. By May 6, 1938 excellent sales had provided him with enough money to move to Harlem, where he began writing Native Son

Native Son

Native Son is a novel by American author Richard Wright. The novel tells the story of 20-year-old Bigger Thomas, an African American living in utter poverty. Bigger lived in Chicago's South Side ghetto in the 1930s...

(1940).

The collection also earned him a Guggenheim Fellowship

Guggenheim Fellowship

Guggenheim Fellowships are American grants that have been awarded annually since 1925 by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation to those "who have demonstrated exceptional capacity for productive scholarship or exceptional creative ability in the arts." Each year, the foundation makes...

, which allowed him to complete Native Son. It was selected by the Book of the Month Club

Book of the Month Club

The Book of the Month Club is a United States mail-order book sales club that offers a new book each month to customers.The Book of the Month Club is part of a larger company that runs many book clubs in the United States and Canada. It was formerly the flagship club of Book-of-the-Month Club, Inc...

as its first book by an African-American author. The lead character, Bigger Thomas, represented the limitations that society placed on African Americans as he could only gain his own agency and self-knowledge by committing heinous acts.

Wright was criticized for his works' concentration on violence. In the case of Native Son, people complained that he portrayed a black man in ways that seemed to confirm whites' worst fears. The period following publication of Native Son was a busy time for Wright. In July 1940 he went to Chicago to do research for a folk history of blacks to accompany photographs selected by Edwin Rosskam. While in Chicago he visited the American Negro Exhibition with Langston Hughes

Langston Hughes

James Mercer Langston Hughes was an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist. He was one of the earliest innovators of the then-new literary art form jazz poetry. Hughes is best known for his work during the Harlem Renaissance...

, Arna Bontemps

Arna Bontemps

Arnaud "Arna" Wendell Bontemps was an American poet and a noted member of the Harlem Renaissance.- Life and career :...

and Claude McKay

Claude McKay

Claude McKay was a Jamaican-American writer and poet. He was a seminal figure in the Harlem Renaissance and wrote three novels: Home to Harlem , a best-seller which won the Harmon Gold Award for Literature, Banjo , and Banana Bottom...

.

He then went to Chapel Hill

Chapel Hill, North Carolina

Chapel Hill is a town in Orange County, North Carolina, United States and the home of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and UNC Health Care...

, North Carolina, where he and Paul Green collaborated on a dramatic version of Native Son. In January 1941 Wright received the prestigious Spingarn Medal

Spingarn Medal

The Spingarn Medal is awarded annually by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People for outstanding achievement by an African American....

for noteworthy achievement by a black. Native Son opened on Broadway, with Orson Welles

Orson Welles

George Orson Welles , best known as Orson Welles, was an American film director, actor, theatre director, screenwriter, and producer, who worked extensively in film, theatre, television and radio...

as director, to generally favorable reviews in March 1941. A volume of photographs almost completely drawn from the files of the Farm Security Administration

Farm Security Administration

Initially created as the Resettlement Administration in 1935 as part of the New Deal in the United States, the Farm Security Administration was an effort during the Depression to combat American rural poverty...

, with text by Wright, Twelve Million Black Voices: A Folk History of the Negro in the United States was published in October 1941 to wide critical acclaim.

Wright's semi-autobiographical Black Boy

Black Boy

Black Boy is an autobiography by Richard Wright. The author explores his childhood and race relations in the South. Wright eventually moves to Chicago, where he establishes his writing career and becomes involved with the Communist Party....

(1945) described his early life from Roxie

Roxie, Mississippi

Roxie is a town in Franklin County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 569 at the 2000 census.-Geography:Roxie is located at .According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of , all of it land....

through his move to Chicago, his clashes with his Seventh-day Adventist

Seventh-day Adventist Church

The Seventh-day Adventist Church is a Protestant Christian denomination distinguished by its observance of Saturday, the original seventh day of the Judeo-Christian week, as the Sabbath, and by its emphasis on the imminent second coming of Jesus Christ...

family, his troubles with white employers and social isolation. American Hunger, published posthumously in 1977, was originally intended as the second volume of Black Boy. The Library of America

Library of America

The Library of America is a nonprofit publisher of classic American literature.- Overview and history :Founded in 1979 with seed money from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Ford Foundation, the LoA has published over 200 volumes by a wide range of authors from Mark Twain to Philip...

edition restored it to that form.

This book detailed Wright's involvement with the John Reed Clubs and the Communist Party, which he left in 1942. The book implied he left earlier, but his withdrawal was not made public until 1944. In the volumes' restored form, the diptych

Diptych

A diptych di "two" + ptychē "fold") is any object with two flat plates attached at a hinge. Devices of this form were quite popular in the ancient world, wax tablets being coated with wax on inner faces, for recording notes and for measuring time and direction.In Late Antiquity, ivory diptychs with...

structure compares the certainties and intolerance of organized communism, the "bourgeois" books and condemned members, with similar qualities in fundamentalist organized religion. Wright disapproved of the purges

Great Purge

The Great Purge was a series of campaigns of political repression and persecution in the Soviet Union orchestrated by Joseph Stalin from 1936 to 1938...

in the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

. Nevertheless, Wright continued to believe in far-left democratic solutions to political problems.

Paris

Wright moved to ParisParis

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

in 1946, and became a permanent American expatriate

Expatriate

An expatriate is a person temporarily or permanently residing in a country and culture other than that of the person's upbringing...

. In Paris, he became friends with Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre was a French existentialist philosopher, playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and literary critic. He was one of the leading figures in 20th century French philosophy, particularly Marxism, and was one of the key figures in literary...

and Albert Camus

Albert Camus

Albert Camus was a French author, journalist, and key philosopher of the 20th century. In 1949, Camus founded the Group for International Liaisons within the Revolutionary Union Movement, which was opposed to some tendencies of the Surrealist movement of André Breton.Camus was awarded the 1957...

. His Existentialist phase was depicted in his second novel, The Outsider

The Outsider (Richard Wright)

The Outsider is a novel by American author Richard Wright, first published in 1953. The Outsider is Richard Wright's second installment in a story of epic proportions, a complex master narrative to show American racism in raw and ugly terms...

(1953), which described an African-American character's involvement with the Communist Party in New York. He also was friends with fellow expatriate writers Chester Himes

Chester Himes

Chester Bomar Himes was an American writer. His works include If He Hollers Let Him Go and a series of Harlem Detective novels...

and James Baldwin

James Baldwin

James Baldwin was an American novelist, essayist and civil rights activist.James Baldwin may also refer to:-Writers:*James Baldwin , American educator, writer and administrator...

, although the relationship with the latter ended in acrimony after Baldwin published his essay Everybody's Protest Novel (collected in Notes of a Native Son

Notes of a Native Son

Notes of a Native Son is a non-fiction book by James Baldwin. It was Baldwin's first non-fiction book, and was published in 1955. The volume collects ten of Baldwin's essays, which had previously appeared in such magazines as Harper's Magazine, Partisan Review, and The New Leader...

), in which he criticized Wright's stereotypical portrayal of Bigger Thomas. In 1954 he published a minor novel, Savage Holiday. After becoming a French citizen in 1947, Wright continued to travel through Europe, Asia, and Africa. These experiences were the basis of numerous nonfiction works. One was Black Power

Black Power

Black Power is a political slogan and a name for various associated ideologies. It is used in the movement among people of Black African descent throughout the world, though primarily by African Americans in the United States...

(1954), a commentary on the emerging nations of Africa.

In 1949, Wright contributed to the anti-communist anthology The God That Failed

The God that Failed

The God That Failed is a 1949 book which collects together six essays with the testimonies of a number of famous ex-communists, who were writers and journalists. The common theme of the essays is the authors' disillusionment with and abandonment of communism...

; his essay had been published in the Atlantic Monthly three years earlier and was derived from the unpublished portion of Black Boy. He was invited to join the Congress for Cultural Freedom, which he rejected, correctly suspecting that it had connections with the CIA. The CIA and FBI had Wright under surveillance starting in 1943. Due to McCarthyism

McCarthyism

McCarthyism is the practice of making accusations of disloyalty, subversion, or treason without proper regard for evidence. The term has its origins in the period in the United States known as the Second Red Scare, lasting roughly from the late 1940s to the late 1950s and characterized by...

, Wright was blacklisted

Hollywood blacklist

The Hollywood blacklist—as the broader entertainment industry blacklist is generally known—was the mid-twentieth-century list of screenwriters, actors, directors, musicians, and other U.S. entertainment professionals who were denied employment in the field because of their political beliefs or...

by Hollywood movie studio executives in the 1950s, but, in 1950, starred as the teenager Bigger Thomas (Wright was 42) in an Argentinian film version of Native Son.

In 1955, Wright visited Indonesia

Indonesia

Indonesia , officially the Republic of Indonesia , is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania. Indonesia is an archipelago comprising approximately 13,000 islands. It has 33 provinces with over 238 million people, and is the world's fourth most populous country. Indonesia is a republic, with an...

for the Bandung Conference and recorded his observations in The Color Curtain: A Report on the Bandung Conference. Wright was upbeat about the possibilities posed by this meeting between recently oppressed nations.

Other works by Richard Wright included White Man, Listen! (1957); a novel The Long Dream in 1958; as well as a collection of short stories

Short story

A short story is a work of fiction that is usually written in prose, often in narrative format. This format tends to be more pointed than longer works of fiction, such as novellas and novels. Short story definitions based on length differ somewhat, even among professional writers, in part because...

, Eight Men, published in 1961, shortly after his death. His works primarily dealt with the poverty, anger, and protests of northern and southern urban black Americans.

His agent, Paul Reynolds sent overwhelmingly negative criticism of Wright's four-hundred page "Island of Hallucinations" manuscript in February 1959. Despite that, in March Wright outlined a novel in which Fish was to be liberated from his racial conditioning and become a dominating character. By May 1959, Wright wanted to leave Paris and live in London. He felt French politics had become increasingly submissive to American pressure. The peaceful Parisian atmosphere he had enjoyed had been shattered by quarrels and attacks instigated by enemies of the expatriate black writers.

On June 26, 1959, after a party marking the French publication of White Man, Listen! Wright became ill, victim of a virulent attack of amoebic dysentery probably contracted during his stay on the Gold Coast. By November 1959 his wife had found a London apartment, but Wright's illness and "four hassles in twelve days" with British immigration officials ended his desire to live in England.

On February 19, 1960 Wright learned from Reynolds that the New York premiere of the stage adaptation of The Long Dream received such bad reviews that the adapter, Ketti Frings, had decided to cancel further performances. Meanwhile, Wright was running into additional problems trying to get The Long Dream published in France. These setbacks prevented his finishing revisions of Island of Hallucinations, which he needed to get a commitment from Doubleday.

In June 1960, Wright recorded a series of discussions for French radio dealing primarily with his books and literary career. He also covered the racial situation in the United States and the world, and specifically denounced American policy in Africa. In late September, to cover extra expenses for his daughter Julia's move from London to Paris to attend the Sorbonne, Wright wrote blurbs for record jackets for Nicole Barclay, director of the largest record company in Paris.

In spite of his financial straits, Wright refused to compromise his principles. He declined to participate in a series of programs for Canadian radio because he suspected American control. For the same reason, Wright rejected an invitation from the Congress for Cultural Freedom to go to India to speak at a conference in memory of Leo Tolstoy

Leo Tolstoy

Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy was a Russian writer who primarily wrote novels and short stories. Later in life, he also wrote plays and essays. His two most famous works, the novels War and Peace and Anna Karenina, are acknowledged as two of the greatest novels of all time and a pinnacle of realist...

. Still interested in literature, Wright helped Kyle Onstott get Mandingo (1957) published in France. His last display of explosive energy occurred on November 8, 1960 in his polemical lecture, "The Situation of the Black Artist and Intellectual in the United States", delivered to students and members of the American Church in Paris. Wright argued that American society reduced the most militant members of the black community to slaves whenever they wanted to question the racial status quo. He offered as proof the subversive attacks of the Communists against Native Son and the quarrels which James Baldwin

James Baldwin (writer)

James Arthur Baldwin was an American novelist, essayist, playwright, poet, and social critic.Baldwin's essays, for instance "Notes of a Native Son" , explore palpable yet unspoken intricacies of racial, sexual, and class distinctions in Western societies, most notably in mid-20th century America,...

and other authors sought with him.

On November 26, 1960, Wright talked enthusiastically about Daddy Goodness with Langston Hughes and gave him the manuscript. Wright contracted Amoebic dysentery on a visit to Africa in 1957, and despite various treatments, his health deteriorated over the next three years. He died in Paris of a heart attack

Myocardial infarction

Myocardial infarction or acute myocardial infarction , commonly known as a heart attack, results from the interruption of blood supply to a part of the heart, causing heart cells to die...

at the age of 52. He was interred in Le Père Lachaise Cemetery. However, Wright's daughter Julia claimed that her father was murdered.

A number of Wright's works have been published posthumously. Some of Wright's more shocking passages dealing with race, sex, and politics were cut or omitted before original publication. In 1991, unexpurgated versions of Native Son, Black Boy, and his other works were published. In addition, in 1994, his novella Rite of Passage was published for the first time.

In the last years of his life, Richard Wright became enamored with the haiku

Haiku in English

Haiku in English is a development of the Japanese haiku poetic form in the English language.Contemporary haiku are written in many languages, but most poets outside of Japan are concentrated in the English-speaking countries....

and wrote over 4,000 such poems. In 1998 a book was published ("Haiku: This Other World" ISBN 0-385-72024-6) with 817 of his own favourite haikus.

A collection of Wright's travel writings was published by the Mississippi University Press in 2001. At his death, Wright left an unfinished book, A Father's Law. It deals with a black policeman and the son he suspects of murder. Wright's daughter Julia Wright published A Father's Law in January 2008, an omnibus edition containing Wright's political works was published under the title Three Books from Exile: Black Power; The Color Curtain; and White Man, Listen!.

Family

Wright married Valencia Barnes Meadman, a modern-dance teacher of Russian Jewish ancestry, in 1939, but the two divorced a year later. In 1941, he married Ellen Poplar, the daughter of immigrants of Polish Jewish ancestry and a Communist Party organizer in Brooklyn. They had two daughters: Julia in 1942 and Rachel in 1949.Literary influences

In Black BoyBlack Boy

Black Boy is an autobiography by Richard Wright. The author explores his childhood and race relations in the South. Wright eventually moves to Chicago, where he establishes his writing career and becomes involved with the Communist Party....

Wright discussed a number of authors whose works influenced his own, including H.L. Mencken, Gertrude Stein

Gertrude Stein

Gertrude Stein was an American writer, poet and art collector who spent most of her life in France.-Early life:...

, Fyodor Dostoevsky

Fyodor Dostoevsky

Fyodor Mikhaylovich Dostoyevsky was a Russian writer of novels, short stories and essays. He is best known for his novels Crime and Punishment, The Idiot and The Brothers Karamazov....

, Sinclair Lewis

Sinclair Lewis

Harry Sinclair Lewis was an American novelist, short-story writer, and playwright. In 1930, he became the first writer from the United States to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, "for his vigorous and graphic art of description and his ability to create, with wit and humor, new types of...

, Marcel Proust

Marcel Proust

Valentin Louis Georges Eugène Marcel Proust was a French novelist, critic, and essayist best known for his monumental À la recherche du temps perdu...

and Edgar Lee Masters

Edgar Lee Masters

Edgar Lee Masters was an American poet, biographer, and dramatist...

.

Awards

Wright received several different literary awards during his lifetime including the Spingarn MedalSpingarn Medal

The Spingarn Medal is awarded annually by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People for outstanding achievement by an African American....

in 1941, the Guggenheim Fellowship

Guggenheim Fellowship

Guggenheim Fellowships are American grants that have been awarded annually since 1925 by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation to those "who have demonstrated exceptional capacity for productive scholarship or exceptional creative ability in the arts." Each year, the foundation makes...

in 1939, and the Story

Story (magazine)

Story was a magazine founded in 1931 by journalist-editor Whit Burnett and his first wife, Martha Foley, in Vienna, Austria. Showcasing short stories by new authors, 67 copies of the debut issue were mimeographed in Vienna, and two years later, Story moved to New York City where Burnett and Foley...

Magazine Award.

Legacy

Black Boy became an instant best-seller upon its publication in 1945. Wright's stories published during the 1950s disappointed some critics who said that his move to Europe alienated him from American blacks and separated him from his emotional and psychological roots. Many of Wright's works failed to satisfy the rigid standards of New CriticismNew Criticism

New Criticism was a movement in literary theory that dominated American literary criticism in the middle decades of the 20th century. It emphasized close reading, particularly of poetry, to discover how a work of literature functioned as a self-contained, self-referential aesthetic...

as the works of younger black writers gained in popularity. During the 1950s Wright grew more internationalist in outlook. While he accomplished much as an important public literary and political figure with a worldwide reputation, his very creative work did decline.

While interest in Black Boy ebbed during the 1950s, a resurgence of interest in critics, Black Boy remains a vital work of historical, sociological, and literary significance whose seminal portrayal of one black man's search for self-actualization in a racist society made possible the works of such successive writers as James Baldwin and Ralph Ellison. It is generally agreed that Wright's influence in Native Son is not a matter of literary style or technique. His impact, rather, has been on ideas and attitudes, and his work has been a force in the social and intellectual history of the United States in the last half of the twentieth century. "Wright was one of the people who made me conscious of the need to struggle", said writer Amiri Baraka

Amiri Baraka

Amiri Baraka , formerly known as LeRoi Jones, is an American writer of poetry, drama, fiction, essays, and music criticism...

.

During the 1970s and 1980s, scholars published critical essays about Wright in prestigious journals. Richard Wright conferences were held on university campuses from Mississippi to New Jersey. A new film version of Native Son, with a screenplay by Richard Wesley, was released in December 1986. Certain Wright novels became required reading in a number of American universities and colleges.

"Recent critics have called for a reassessment of Wright's later work in view of his philosophical project. Notably, Paul Gilroy

Paul Gilroy

-Biography:Born in the East End of London to Guyanese and English parents , he was educated at University College School and obtained his bachelor's degree at Sussex University in 1978. He moved from there to Birmingham University where he completed his Ph.D...

has argued that 'the depth of his philosophical interests has been either overlooked or misconceived by the almost exclusively literary enquiries that have dominated analysis of his writing'." "His most significant contribution, however, was his desire to accurately portray blacks to white readers, thereby destroying the white myth of the patient, humorous, subservient black man".

While some of his work was weak and unsuccessful especially that completed within the last three years of his life—his best work will continue to attract readers. His three masterpieces Uncle Tom's Children, Native Son, and Black Boy—are a crowning achievement for him and for American literature.

In April 2009, Wright was featured on a U.S. Postage Stamp. The 61-cent, two ounce rate stamp is the 25th installment of the literary arts series and features a portrait of Richard Wright in front of snow–swept tenements on the South Side of Chicago, a scene that recalls the setting of Native Son.

In 2009, Wright was featured in a 90-minute documentary about the WPA Writers' Project titled Soul of a People: Writing America's Story. His life and work during the 1930s is also highlighted in the companion book, Soul of a People: The WPA Writers' Project Uncovers Depression America.

Publications

- Richard Wright: Early Works (Arnold Rampersad, ed.) (Library of AmericaLibrary of AmericaThe Library of America is a nonprofit publisher of classic American literature.- Overview and history :Founded in 1979 with seed money from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Ford Foundation, the LoA has published over 200 volumes by a wide range of authors from Mark Twain to Philip...

, 1991) ISBN 978-0-94045066-6 - Richard Wright: Later Works (Arnold Rampersad, ed.) (Library of AmericaLibrary of AmericaThe Library of America is a nonprofit publisher of classic American literature.- Overview and history :Founded in 1979 with seed money from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Ford Foundation, the LoA has published over 200 volumes by a wide range of authors from Mark Twain to Philip...

, 1991) ISBN 978-0-940450-67-7

Drama:

- Native SonNative SonNative Son is a novel by American author Richard Wright. The novel tells the story of 20-year-old Bigger Thomas, an African American living in utter poverty. Bigger lived in Chicago's South Side ghetto in the 1930s...

: The Biography of a Young American with Paul Green (New York: Harper, 1941)

Fiction:

- Uncle Tom's ChildrenUncle Tom's ChildrenUncle Tom's Children is a collection of short stories by African American author Richard Wright, also the author of Black Boy, Native Son, and The Outsider. Uncle Tom's Children includes four short stories and was successful when it was first published in 1938...

(New York: Harper, 1938) - "The Man Who Was Almost a ManThe Man Who Was Almost a Man"The Man Who Was Almost a Man" also known as "Almos' a man", is a short story by Richard Wright. It was published in 1961 as part of Wright's compilation Eight Men...

" (New York: Harper, 1939) - Native SonNative SonNative Son is a novel by American author Richard Wright. The novel tells the story of 20-year-old Bigger Thomas, an African American living in utter poverty. Bigger lived in Chicago's South Side ghetto in the 1930s...

(New York: Harper, 1940) - The OutsiderThe Outsider (Richard Wright)The Outsider is a novel by American author Richard Wright, first published in 1953. The Outsider is Richard Wright's second installment in a story of epic proportions, a complex master narrative to show American racism in raw and ugly terms...

(New York: Harper, 1953) - Savage Holiday (New York: Avon, 1954)

- The Long Dream (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1958)

- Eight Men (Cleveland and New York: World, 1961)

- Lawd Today (New York: Walker, 1963)

- Rite of Passage (New York: Harper Collins, 1994)

- A Father's Law (London: Harper Perennial, 2008)

Non-fiction:

- How "Bigger" Was Born; Notes of a Native Son (New York: Harper, 1940)

- 12 Million Black Voices: A Folk History of the Negro in the United States (New York: Viking, 1941)

- Black BoyBlack BoyBlack Boy is an autobiography by Richard Wright. The author explores his childhood and race relations in the South. Wright eventually moves to Chicago, where he establishes his writing career and becomes involved with the Communist Party....

(New York: Harper, 1945) - Black Power (New York: Harper, 1954)

- The Color Curtain (Cleveland and New York: World, 1956)

- Pagan Spain (New York: Harper, 1957)

- Letters to Joe C. Brown (Kent State University Libraries, 1968)

- American Hunger (New York: Harper & Row, 1975)

Essays:

- The Ethics Of Living Jim Crow: An Autobiographical Sketch (1937)

- Introduction to Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City (1945)

- I Choose Exile (1951)

- White Man, Listen! (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1957)

- Blueprint for Negro Literature (New York City, New York) (1937)

- The God that FailedThe God that FailedThe God That Failed is a 1949 book which collects together six essays with the testimonies of a number of famous ex-communists, who were writers and journalists. The common theme of the essays is the authors' disillusionment with and abandonment of communism...

(contributor) (1949)

Poetry:

- Haiku: This Other World. (Eds. Yoshinobu Hakutani and Robert L. Tener. Arcade, 1998)

External links

- Richard Wright Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

- Richard Wright Collection (MUM00488) at the University of Mississippi.

- Richard Wright: Black Boy (documentary film)

- Richard Wright's Biography at the Mississippi Writers Page

- Richard Wright at the Independent Television Service

- Richard Wright's Photo & Gravesite

- Biography of Wright and his works

- Brief biography below image of Richard Wright Immortalized 4'09 on 61-cent/2oz USPS stamp (amends above Note#18 URL)

- Summary of Richard Wright's Novels

- Synopsis of Wright's Fiction

- Reviews of Wright's Work

- Critical Reception of Wright's Travel Writings

- Review of The Outsider

- Special Section on "Facing the Future After Richard Wright"

- A Western Man of Color: Richard Wright and the World

- Online text of 12 Million Black Voices

- Excerpt from Black Power

- Online Text of The Color Curtain

- Online Text of Pagan Spain

- Online text of The Long Dream

- Excerpt from The God That Failed

- Online text of Native Son

- Looking for Richard Wright from the Beinecke Library, Yale University

- Richard Wright, Native Son, and the Beinecke: Being Brought to My Senses from the Beinecke Library, Yale University