Roman abacus

Encyclopedia

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome was a thriving civilization that grew on the Italian Peninsula as early as the 8th century BC. Located along the Mediterranean Sea and centered on the city of Rome, it expanded to one of the largest empires in the ancient world....

developed the Roman hand abacus

Abacus

The abacus, also called a counting frame, is a calculating tool used primarily in parts of Asia for performing arithmetic processes. Today, abaci are often constructed as a bamboo frame with beads sliding on wires, but originally they were beans or stones moved in grooves in sand or on tablets of...

, a portable, but less capable, base-10 version of the previous Babylonia

Babylonia

Babylonia was an ancient cultural region in central-southern Mesopotamia , with Babylon as its capital. Babylonia emerged as a major power when Hammurabi Babylonia was an ancient cultural region in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq), with Babylon as its capital. Babylonia emerged as...

n abacus. It was the first portable calculating device for engineers, merchants and presumably tax collectors. It greatly reduced the time needed to perform the basic operations of arithmetic using Roman numerals

Roman numerals

The numeral system of ancient Rome, or Roman numerals, uses combinations of letters from the Latin alphabet to signify values. The numbers 1 to 10 can be expressed in Roman numerals as:...

.

As Karl Menninger

Karl Menninger (mathematics)

Karl Menninger was a German teacher of and writer about mathematics. His major work was Zahlwort und Ziffer , about non-academic mathematics in much of the world...

says on page 315 of his book, "For more extensive and complicated calculations, such as those involved in Roman land surveys, there was, in addition to the hand abacus, a true reckoning board with unattached counters or pebbles. The Etruscan cameo and the Greek predecessors, such as the Salamis

Salamis Island

Salamis , is the largest Greek island in the Saronic Gulf, about 1 nautical mile off-coast from Piraeus and about 16 km west of Athens. The chief city, Salamina , lies in the west-facing core of the crescent on Salamis Bay, which opens into the Saronic Gulf...

Tablet

Salamis Tablet

The Salamis Tablet was an early counting device dating from around 300 B.C. that was discovered on the island of Salamis in 1846. A precursor to the abacus, it is thought that it represents a Babylonian means of performing mathematical calculations common in the ancient world...

and the Darius Vase, give us a good idea of what it must have been like, although no actual specimens of the true Roman counting board are known to be extant. But language, the most reliable and conservative guardian of a past culture, has come to our rescue once more. Above all, it has preserved the fact of the unattached counters so faithfully that we can discern this more clearly than if we possessed an actual counting board. What the Greeks called psephoi, the Romans called calculi. The Latin word calx means 'pebble' or 'gravel stone'; calculi are thus little stones (used as counters)."

Both the Roman abacus and the Chinese

China

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

suanpan have been used since ancient times. With one bead above and four below the bar, the systematic configuration of the Roman abacus is coincident to the modern Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

ese Soroban, although the soroban is historically derived from the suanpan.

Layout

The Late RomanRoman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

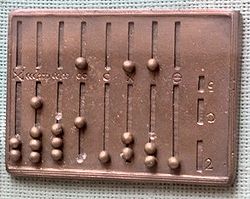

hand abacus shown here as a reconstruction contains seven longer and seven shorter grooves used for whole number counting, the former having up to four beads in each, and the latter having just one. The rightmost two grooves were for fractional counting. The abacus was made of a metal plate where the beads ran in slots. The size was such that it could fit in a modern shirt pocket.

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

|O| |O| |O| |O| |O| |O| |O| |O|

MM CM XM M C X I Ө Ɛ

--- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- ---

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | Ɔ

|O| |O| |O| |O| |O| |O| |O| |O| | |

|O| |O| |O| |O| |O| |O| |O| |O| | |

|O| |O| |O| |O| |O| |O| |O| |O| | |

|O| |O| |O| |O| |O| |O| |O| |O| |O| 2

|O| |O|

The diagram is based on the Roman hand abacus at the London Science Museum.

The lower groove marked I indicates units, X tens, and so on up to millions. The beads in the upper shorter grooves denote fives—five units, five tens, etc., essentially in a bi-quinary coded decimal

Bi-quinary coded decimal

Bi-quinary coded decimal is a numeral encoding scheme used in many abacuses and in some early computers, including the Colossus. The term bi-quinary indicates that the code comprises both a two-state and a five-state component...

place value system.

Computations are made by means of beads which would probably have been slid up and down the grooves to indicate the value of each column.

The upper slots contained a single bead while the lower slots contained four beads, the only exceptions being the two rightmost columns, column 2 marked Ө and column 3 with three symbols down the side of a single slot or beside three separate slots with Ɛ, 3 or S or a symbol like the £ sign but without the horizontal bar beside the top slot, a backwards C beside the middle slot and a 2 symbol beside the bottom slot, depending on the example abacus and the source which could be Friedlein, Menninger or Ifrah. These latter two slots are for mixed-base math, a development unique to the Roman hand abacus described in following sections.

The longer slot with five beads below the Ө position allowed for the counting of 1/12 of a whole unit called an uncia (from which the English words inch and ounce are derived), making the abacus useful for Roman measures and Roman currency

Roman currency

The Roman currency during most of the Roman Republic and the western half of the Roman Empire consisted of coins including the aureus , the denarius , the sestertius , the dupondius , and the as...

. The first column was either a single slot with 4 beads or 3 slots with one, one and two beads respectively top to bottom. In either case, three symbols were included beside the single slot version or one symbol per slot for the three slot version. Many measures were aggregated by twelfths. Thus the Roman pound ('libra'), consisted of 12 ounces (unciae) (1 uncia = 28 grams). A measure of volume, congius

Congius

In Ancient Roman measurement, congius was a liquid measure, which contained six sextarii, or the eighth-part of the amphora; that is about 3.25 litres...

, consisted of 12 heminae (1 hemina = 0.273 litre

Litre

pic|200px|right|thumb|One litre is equivalent to this cubeEach side is 10 cm1 litre water = 1 kilogram water The litre is a metric system unit of volume equal to 1 cubic decimetre , to 1,000 cubic centimetres , and to 1/1,000 cubic metre...

s). The Roman foot (pes), was 12 inches (unciae) (1 uncia = 2.43 cm). The actus, the standard furrow length when plowing, was 120 pedes. There were however other measures in common use - for example the sextarius was two heminae.

The as

As (coin)

The , also assarius was a bronze, and later copper, coin used during the Roman Republic and Roman Empire.- Republican era coinage :...

, the principal copper coin in Roman currency, was also divided into 12 unciae

Uncia (coin)

The uncia was a Roman unit of length and of weight .-Republican coin:...

. Again, the abacus was ideally suited for counting currency.

Symbols and usage

The first column was arranged either as a single slot with three different symbols or as three separate slots with one, one and two beads or counters respectively and a distinct symbol for each slot. It is most likely that the rightmost slot or slots were used to enumerate fractions of an uncia and these were from top to bottom, 1/2 s , 1/4 s and 1/12 s of an uncia. The upper character in this slot (or the top slot where the righmost column is three separate slots) is the character most closely resembling that used to denote a semuncia or 1/24. The name semuncia denotes 1/2 of an uncia or 1/24 of the base unit, the As. Likewise the next character is that used to indicate a sicilicus or 1/48 th of an As which is 1/4 of an uncia. These two characters are to be found in the table of Roman Fractions on P75 of Graham Flegg's book. Finally, the last or lower character is most similar but not identical to the character in Flegg's table to denote 1/144 of an As, the dimidio sextula which is the same as 1/12 of an uncia.This is however even more strongly supported by Gottfried Friedlein in the table at the end of the book which summarizes the use of a very extensive set of alternative formats for different values including that of fractions. In the entry in this table numbered 14 referring back to (Zu) 48, he lists different symbols for the semuncia (1/24), the sicilicus (1/48), the sextula (1/72), the dimidia sextula (1/144), and the scriptulum (1/288). Of prime importance, he specifically notes the formats of the semuncia, sicilicus and sextula as used on the Roman bronze abacus, "auf dem chernan abacus". The semuncia is the symbol resembling a capital "S", but he also includes the symbol that resembles a numeral three with horizontal line at the top, the whole rotated 180 degrees. It is these two symbols that appear on samples of abacus in different museums. The symbol for the sicilicus is that found on the abacus and resembles a large right single quotation mark spanning the entire line height.

The most important symbol is that for the sextula, which resembles very closely a cursive digit 2. Now, as stated by Friedlein, this symbol indicates the value of 1/72 of an As. However, he stated specifically in the penultimate sentence of section 32 on page 23, the two beads in the bottom slot each have a value of 1/72. This would allow this slot to represent only 1/72 (i.e. 1/6 × 1/12 with one bead) or 1/36 (i.e. 2/6 × 1/12 = 1/3 × 1/12 with two beads) of an uncia respectively. This contradicts all existing documents that state this lower slot was used to count thirds of an uncia (i.e. 1/3 and 2/3 × 1/12 of an As.

This results in two opposing interpretations of this slot, that of Friedlein and that of many other experts such as Ifrah and Menninger who propose the one and two thirds usage. There is however a third possibility.

If this symbol refers to the total value of the slot (i.e. 1/72th of an as), then each of the two counters can only have a value of half this or 1/144th of an as or 1/12th of an uncia. This then suggests that these two counters did in fact count twelfths of an uncia and not thirds of an uncia. Likewise, for the top and upper middle, the symbols for the semuncia and sicilicus could also indicate the value of the slot itself and since there is only one bead in each, would be the value of the bead also. This would allow the symbols for all three of these slots to represent the slot value without involving any contradictions.

A further argument which suggests the lower slot represents twelfths rather than thirds of an uncia is best described by the figure below. The diagram below assumes for ease that we are talking about fractions of an uncia as a unit value equal to one (1). If the beads in the lower slot of column I represent thirds, then the beads in the three slots for fractions of 1/12 of an uncia cannot show all values from 1/12 of an uncia to 11/12 of an uncia. In particular, it would not be possible to represent 1/12, 2/12 and 5/12. Furthermore this arrangement would allow for seemingly unnecessary values of 13/12, 14/12 and 17/12. Even more significant is the fact that there would not be a rational progression of arrangements of the beads in step with increasing values of twelfths. Likewise, if the each of the beads in the lower slot are assumed to have a value of 1/6 of an uncia, there is again an irregular series of values available to the user, no possible value of 1/12 and an extraneous value of 13/12. It is only by employing a value of 1/12 for each of the beads in the lower slot that all values of twelfths from 1/12 to 11/12 can be represented and in a logical ternary, binary, binary progression for the slots from bottom to top. This can be best appreciated by reference to the figure below.

It can be argued that the beads in this first column could have been used as originally believed and widely stated, i.e. as ½, ¼ and ⅓ and ⅔, completely independently of each other. However this is more difficult to support in the case where this first column is a single slot with the three inscribed symbols. To complete the known possibilities, it must be noted that in one example found by the author, the first and second columns were transposed. It is left to the reader to ponder upon this and put forward their own interpretations of the use of these devices. It would not be unremarkable if the makers of these instruments produced output with minor differences, since the vast number of variations in modern calculators provide a compelling example.

What can be deduced from these Roman abacuses, is the undeniable proof that Romans were using a device that exhibited a decimal, place value system, and the inferred knowledge of a zero value as represented by a column with no beads in a counted position. Furthermore, the bi-quinay nature of the integer portion allowed for direct transcription from and to the written Roman numerals. No matter what the true usage was, what cannot be denied is that these instruments provide very strong arguments in favour of far greater facility with practical mathematics known and practised by the Romans.

The reconstruction of a Roman hand abacus in the Cabinet des Médailles, Bibliothèque nationale, supports this. The replica Roman hand abacus at Landesinstitut für Lehrerbildung und Schulentwicklung, shown alone here Replica Roman Hand Abacus, provides even more evidence.

Inference of zero and negative numbers

When using a counting board or abacus the rows or columns often represent nothing, or zero0 (number)

0 is both a numberand the numerical digit used to represent that number in numerals.It fulfills a central role in mathematics as the additive identity of the integers, real numbers, and many other algebraic structures. As a digit, 0 is used as a placeholder in place value systems...

. Since the Romans used Roman numerals to record results, and since Roman numerals were all positive, there was no need for a zero notation. But the Romans clearly knew the concept of zero occurring in any place value, row or column.

It may be also possible to infer that they were familiar with the concept of a negative number as Roman merchants needed to understand and manipulate liabilities against assets and loans versus investments.