Seacliff Lunatic Asylum

Encyclopedia

Psychiatric hospital

Psychiatric hospitals, also known as mental hospitals, are hospitals specializing in the treatment of serious mental disorders. Psychiatric hospitals vary widely in their size and grading. Some hospitals may specialise only in short-term or outpatient therapy for low-risk patients...

in Seacliff

Seacliff, New Zealand

Seacliff is a small village located north of Dunedin in the Otago region of New Zealand's South Island. The village lies roughly half way between the estuary of Blueskin Bay and the mouth of the Waikouaiti River at Karitane, on the eastern slopes of Kilmog hill...

, New Zealand

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

. When built in the late 19th century, it was the largest building in the country, noted for its scale and extravagant architecture. It would also become infamous for construction faults resulting in partial collapse, as well as a 1942 fire which destroyed a wooden outbuilding, claiming 37 lives (39 in other sources), because the victims were trapped in a locked ward.

The asylum was located less than 20 miles north of Dunedin

Dunedin

Dunedin is the second-largest city in the South Island of New Zealand, and the principal city of the Otago Region. It is considered to be one of the four main urban centres of New Zealand for historic, cultural, and geographic reasons. Dunedin was the largest city by territorial land area until...

and close to the county centre of Palmerston

Palmerston, New Zealand

The town of Palmerston, in New Zealand's South Island lies 50 kilometres to the north of the city of Dunedin. It is the largest town in the Waihemo Ward of the Waitaki District with a population of 890 residents...

, in an isolated coastal spot within a forested reserve. The site is now divided between the Truby King Recreation Reserve, where most of the old buildings have been demolished and most of the area still remains dense woodland, and The Asylum backpacker hostel

Backpacking (travel)

Backpacking is a term that has historically been used to denote a form of low-cost, independent international travel. Terms such as independent travel and/or budget travel are often used...

, which uses some remaining hospital buildings.

History

Planning

The need for a new asylum in the Dunedin area was created by the Otago gold rush expansion of the city, and triggered by the inadequacy of the Littlebourne Mental Asylum. In 1875, the Provincial Council decided to build a new structure on "a reserve of fine land at Brinn's Point, north of Port ChalmersPort Chalmers

Port Chalmers is a suburb and the main port of the city of Dunedin, New Zealand, with a population of 3,000. Port Chalmers lies ten kilometres inside Otago Harbour, some 15 kilometres northeast from Dunedin's city centre....

". Initial work was begun in the "dense trackless forest" in 1878, though the Director of the Geological Survey criticised the site location, because he felt that the hillside was unstable.

Seacliff Asylum was one of the most important works of Robert Lawson

Robert Lawson (architect)

Robert Arthur Lawson was one of New Zealand's pre-eminent 19th century architects. It has been said he did more than any other designer to shape the face of the Victorian era architecture of the city of Dunedin...

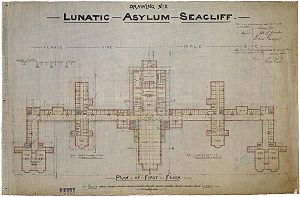

, a New Zealand architect of the 19th century. Known for designing in a range of styles, including the Gothic Revival, he started work on the new asylum in 1874, and was involved with it until the completion of the main block in 1884. At that time, it was New Zealand's largest building, and was to house 500 patients and 50 staff. It had cost £78,000 to construct.

Architecturally, Lawson's work on the asylum was very exuberant, making some of his previous designs look comparatively tame. The asylum had turret

Turret

In architecture, a turret is a small tower that projects vertically from the wall of a building such as a medieval castle. Turrets were used to provide a projecting defensive position allowing covering fire to the adjacent wall in the days of military fortification...

s on corbel

Corbel

In architecture a corbel is a piece of stone jutting out of a wall to carry any superincumbent weight. A piece of timber projecting in the same way was called a "tassel" or a "bragger". The technique of corbelling, where rows of corbels deeply keyed inside a wall support a projecting wall or...

s projecting from nearly every corner, with the gable

Gable

A gable is the generally triangular portion of a wall between the edges of a sloping roof. The shape of the gable and how it is detailed depends on the structural system being used and aesthetic concerns. Thus the type of roof enclosing the volume dictates the shape of the gable...

d roof line dominated by a large tower complete with further turrets and a spire. The building contained four and a half million bricks made of local clay on the site and was 225 metres long by 67 metres wide. The great central tower of 50 m height, an essential element of many revivalist designs, was also proposed to double as an observation tower if inmates should try to escape.

It was later said of the building, and its (forlorn) location, that: "The Victorians might not have wanted their lunatics living with them, but they liked to house them grandly.".

The asylum was progressively added to in later years as it was transformed to function as a working farm, though most of the newer buildings were much simpler wooden structures. Staff lived in separate accommodation close to the wards, though they were also able to socialise in nearby Dunedin.

Faults

Structural problems began to manifest themselves even before the first building was completed, and in 1887, only 3 years after the opening of the main block, a major landslide occurred - as predicted as a risk by the surveyors - and affected a temporary building. The main block did however survive until 1959, when it was demolished because of further earth movement.Still, the problems with the design's stability could no longer be ignored even at the time, and in 1888 an enquiry into the collapse was set up. In February of that year, realising that he could be in legal trouble, Lawson applied to the enquiry to be allowed counsel to defend him. During the enquiry all involved in the construction - including the contractor, the head of the Public Works Department, the projects clerk of works and Lawson himself - gave evidence to support their competence. The enquiry however decided that it was the architect who carried the ultimate responsibility, and Lawson was found both 'negligent and incompetent'. This may be considered an unreasonable finding as the nature of the site's underlying bentonite

Bentonite

Bentonite is an absorbent aluminium phyllosilicate, essentially impure clay consisting mostly of montmorillonite. There are different types of bentonite, each named after the respective dominant element, such as potassium , sodium , calcium , and aluminum . Experts debate a number of nomenclatorial...

clays was beyond contemporary knowledge of soil mechanics, with Lawson singled out to bear the blame (this would however disregard the fact that the site's problems had been pointed out by the surveyors). As New Zealand was at this time suffering an economic recession, Lawson found himself virtually unemployable.

Treatment

Treatment of the patients at Seacliff, whether truly insaneInsanity

Insanity, craziness or madness is a spectrum of behaviors characterized by certain abnormal mental or behavioral patterns. Insanity may manifest as violations of societal norms, including becoming a danger to themselves and others, though not all such acts are considered insanity...

, mentally retarded

Mental retardation

Mental retardation is a generalized disorder appearing before adulthood, characterized by significantly impaired cognitive functioning and deficits in two or more adaptive behaviors...

or held in the institution for what would today be classed as simply being difficult, was often very callous, or even outright cruel, a feature of many mental asylums of the times. Janet Frame

Janet Frame

Janet Paterson Frame, ONZ, CBE was a New Zealand author. She wrote eleven novels, four collections of short stories, a book of poetry, an edition of juvenile fiction, and three volumes of autobiography during her lifetime. Since her death, a twelfth novel, a second volume of poetry, and a handful...

, a famous New Zealand writer, was held at the asylum during the 1940s and wrongly diagnosed as a schizophrenic

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a mental disorder characterized by a disintegration of thought processes and of emotional responsiveness. It most commonly manifests itself as auditory hallucinations, paranoid or bizarre delusions, or disorganized speech and thinking, and it is accompanied by significant social...

. In her autobiography, she recalled that:

- "The attitude of those in charge, who unfortunately wrote the reports and influenced the treatment, was that of reprimand and punishment, with certain forms of medical treatment being threatened as punishment for failure to ‘co-operate’ and where ‘not co-operate’ might mean a refusal to obey an order, say, to go to the doorless lavatories with six others and urinate in public while suffering verbal abuse by the nurse for being unwilling. ‘Too fussy are we? Well, Miss Educated, you’ll learn a thing or two here."

Frame also describes other patients being beaten for bedwetting

Bedwetting

Nocturnal enuresis, commonly called bedwetting, is involuntary urination while asleep after the age at which bladder control usually occurs. Nocturnal enuresis is considered primary when a child has not yet had a prolonged period of being dry...

, and that all patients tended to continually look for the possibility to run away from the institution. She herself only escaped lobotomy

Lobotomy

Lobotomy "; τομή – tomē: "cut/slice") is a neurosurgical procedure, a form of psychosurgery, also known as a leukotomy or leucotomy . It consists of cutting the connections to and from the prefrontal cortex, the anterior part of the frontal lobes of the brain...

at Seacliff by fact of her new-found public success (she had won a literary prize while in the institution). Others were not so lucky, being forced to submit to what today would be considered barbaric procedures like the 'unsexing' operation (removal of fallopian tube

Fallopian tube

The Fallopian tubes, also known as oviducts, uterine tubes, and salpinges are two very fine tubes lined with ciliated epithelia, leading from the ovaries of female mammals into the uterus, via the utero-tubal junction...

s, ovaries

Ovary

The ovary is an ovum-producing reproductive organ, often found in pairs as part of the vertebrate female reproductive system. Ovaries in anatomically female individuals are analogous to testes in anatomically male individuals, in that they are both gonads and endocrine glands.-Human anatomy:Ovaries...

and clitoris

Clitoris

The clitoris is a sexual organ that is present only in female mammals. In humans, the visible button-like portion is located near the anterior junction of the labia minora, above the opening of the urethra and vagina. Unlike the penis, which is homologous to the clitoris, the clitoris does not...

) of Annemarie Anon [sic] in what was at the time considered a 'successful' treatment. Electroconvulsive therapy

Electroconvulsive therapy

Electroconvulsive therapy , formerly known as electroshock, is a psychiatric treatment in which seizures are electrically induced in anesthetized patients for therapeutic effect. Its mode of action is unknown...

was also widely used, a procedure whose use is nowadays very contested.

At the same time, Seacliff was also groundbreaking in some parts of its treatment programme, with noted medical reformer Truby King

Truby King

thumb|Sir Frederic Truby KingSir Frederic Truby King CMG , generally known as Truby King, was a New Zealand health reformer and Director of Child Welfare. He is best known as the founder of the Plunket Society....

appointed Medical Superintendent in 1889, a position he held for 30 years. Patients were 'prescribed' fresh air, exercise, good nutrition and productive work (for example, in on-site laundries, gardens, and a forge) as part of their therapeutic regime . King

Truby King

thumb|Sir Frederic Truby KingSir Frederic Truby King CMG , generally known as Truby King, was a New Zealand health reformer and Director of Child Welfare. He is best known as the founder of the Plunket Society....

is credited as having turned what was essentially conceived as a prison

Prison

A prison is a place in which people are physically confined and, usually, deprived of a range of personal freedoms. Imprisonment or incarceration is a legal penalty that may be imposed by the state for the commission of a crime...

into an efficient working farm. Another of King's

Truby King

thumb|Sir Frederic Truby KingSir Frederic Truby King CMG , generally known as Truby King, was a New Zealand health reformer and Director of Child Welfare. He is best known as the founder of the Plunket Society....

innovations, was his implementation of small dormitories housed in buildings adjacent to the larger asylum. This style of accommodation has been considered the forerunner to the villa system later adopted by all mental health institutions in New Zealand.

A nurse working at the hospital in the later years of its operation also describes the situation much less critically than Janet Frame, noting that while many patients at Seacliff during her time (1940s) would not have been confined in modern days, the atmosphere was more like that of a large working community. Patients capable of working were asked to help with various duties, partly because of staff shortages in the World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

years. Unless considered dangerous, patients were also allowed some liberties, such as being allowed to go fishing - an activity that provided patients with leisure time, while also helping the fishing business Truby King had long ago established at nearby Karitane

Karitane

The seaside settlement of Karitane is located within the limits of the city of Dunedin in New Zealand, 35 kilometres to the north of the city centre....

.

Fatal fire

Around 9:45 pm, on the 8th of December 1942, a fire broke out in Ward 5 of the hospital (also called the 'Simla' building). Ward 5 was a two-story wooden structure added onto the original construction, holding 39 (41 according to some sources) female patients. All patients had been locked into their rooms or into the 20-bed dormitoryDormitory

A dormitory, often shortened to dorm, in the United States is a residence hall consisting of sleeping quarters or entire buildings primarily providing sleeping and residential quarters for large numbers of people, often boarding school, college or university students...

, partially because World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

had caused a nursing staff shortage. Checks were also only made once an hour.

After the fire was noticed by a male attendant, the hospital's firefighter

Firefighter

Firefighters are rescuers extensively trained primarily to put out hazardous fires that threaten civilian populations and property, to rescue people from car incidents, collapsed and burning buildings and other such situations...

s tried to extinguish the flames with water from a close-by hydrant, while two women were saved from rooms that did not have locked shutters. However, the flames were too strong, and after an hour the ward was reduced to ashes - though the fire could be kept from spreading to other buildings. All patients who remained in Ward 5 are thought to have died via suffocation

Suffocation

Suffocation is the process of Asphyxia.Suffocation may also refer to:* Suffocation , an American death metal band* "Suffocation", a song on Morbid Angel's debut album, Altars of Madness...

from smoke inhalation.

An inquiry into the fire criticised the lack of nursing staff, but praised the firefighters for their prompt and valiant actions, including the quick evacuation

Emergency evacuation

Emergency evacuation is the immediate and rapid movement of people away from the threat or actual occurrence of a hazard. Examples range from the small scale evacuation of a building due to a bomb threat or fire to the large scale evacuation of a district because of a flood, bombardment or...

of many other patients in nearby, threatened buildings. It also remarked on the critical absence of sprinkler systems (present in other new sections of the institution), and recommended their installation in all psychiatric institutions of the country. The cause of the fire was not found, though there was speculation about an electrical short circuit

Short circuit

A short circuit in an electrical circuit that allows a current to travel along an unintended path, often where essentially no electrical impedance is encountered....

due to shifting foundations. The disaster would remain New Zealand's worst loss of life in a fire until the Ballantyne's store disaster

Ballantyne's store disaster

The Ballantyne's fire on 18 November 1947 remains the deadliest fire in New Zealand history. Forty one people died in the blaze in the Christchurch Central City; all were employees who found themselves trapped by the fire or were overcome by smoke while evacuating the store complex without a fire...

in Christchurch

Christchurch

Christchurch is the largest city in the South Island of New Zealand, and the country's second-largest urban area after Auckland. It lies one third of the way down the South Island's east coast, just north of Banks Peninsula which itself, since 2006, lies within the formal limits of...

five years later.

Aftermath

Primarily as a result of worsening ground conditions which progressively affected many of the buildings, the hospital functions of Seacliff were progressively shut down and moved to Cherry Farm, with the hospital ceasing operation at its original location in 1973. The site was divided up, with the land surrounding the original building site later becoming Truby King Recreation Reserve, having passed into the ownership of Dunedin City in 1991. Around 80% of the reserve is densely wooded, with the area commonly called the 'Enchanted Forest'. The last remaining building in the reserve was demolished due to structural faults in 1992, after an initiative to establish a transport museumTransport museum

A transport museum is a museum that holds collections of transport items, which are often limited to land transport —including old cars, trains, trams/streetcars, buses, trolleybuses and coaches—but can also include air transport or waterborne transport items, along with educational displays and...

had failed.

The remaining area of hospital buildings outside the Reserve is privately owned and operated as the Asylum Backpackers / Asylum Lodge. In the summer of 2006-2007, regular guided tours of the hospital grounds were operated in conjunction with the Taieri Gorge Railway

Taieri Gorge Railway

The Taieri Gorge Railway is a railway line and tourist train operation based at Dunedin Railway Station in the South Island of New Zealand...

's Seasider tourist train service.

See also

- List of New Zealand disasters by death toll

- Janet FrameJanet FrameJanet Paterson Frame, ONZ, CBE was a New Zealand author. She wrote eleven novels, four collections of short stories, a book of poetry, an edition of juvenile fiction, and three volumes of autobiography during her lifetime. Since her death, a twelfth novel, a second volume of poetry, and a handful...

, the most famous of the asylum's patients / inmates - Truby KingTruby Kingthumb|Sir Frederic Truby KingSir Frederic Truby King CMG , generally known as Truby King, was a New Zealand health reformer and Director of Child Welfare. He is best known as the founder of the Plunket Society....

, medical reformer, administrator of the asylum for 30 years - Lionel TerryLionel TerryEdward Lionel Terry was a New Zealand white supremacist and murderer, incarcerated in psychiatric institutions after murdering a Chinese immigrant, Mr. Joe Kum Yung, in Wellington, New Zealand in 1905.-Early life:...

, a schizophrenic white supremacistWhite supremacyWhite supremacy is the belief, and promotion of the belief, that white people are superior to people of other racial backgrounds. The term is sometimes used specifically to describe a political ideology that advocates the social and political dominance by whites.White supremacy, as with racial...

murderer who died at Seacliff, after several escapes