Senate of the Roman Empire

Encyclopedia

The Senate of the Roman Empire was a political institution in the ancient Roman Empire

. After the fall of the Roman Republic

, the constitutional balance of power shifted from the "Roman Senate

" to the "Roman Emperor

". Beginning with the first emperor, Augustus

, the Emperor and the Senate were technically two co-equal branches of government. In practice, however the actual authority of the imperial Senate was negligible, as the Emperor held the true power of the state. As such, membership in the Senate became sought after by individuals seeking prestige and social standing, rather than actual authority. During the reigns of the first Emperors, legislative, judicial, and electoral powers were all transferred from the "Roman assemblies

" to the Senate. However, since the control that the Emperor held over the senate was absolute, the Senate acted as a vehicle through which the Emperor exercised his autocratic powers.

" Julius Caesar

. Augustus sought to reduce the size of the Senate, and did so through three revisions to the list of senators. By the time that these revisions had been completed, the Senate had been reduced to 600 members, and after this point, the size of the Senate was never again drastically altered. To reduce the size of the senate, Augustus expelled senators who were of low birth, and then he reformed the rules which specified how an individual could become a senator. Under Augustus' reforms, a senator had to be a citizen of free birth, and have property worth at least 1,000,000 sesterces.

Under the Empire, as was the case during the late Republic, one could become a senator by being elected "Quaestor

" (a magistrate with financial duties). Under the Empire, however, one could only stand for election to the Quaestor

ship if one was of senatorial rank, and to be of senatorial rank, one had to be the son of a senator. If an individual was not of senatorial rank, there were two ways for that individual to become a senator. Under the first method, the Emperor granted that individual the authority to stand for election to the Quaestorship, while under the second method, the Emperor appointed that individual to the senate by issuing a decree (the adlectio).

Beginning in 9 BC, an official list of senators (the album senatorium) was maintained and revised each year. Individuals were added to the list if they had recently satisfied the requirements for entry into the Senate, and were removed from the list if they no longer satisfied the requirements necessary to maintain senate membership. The list named each senator by order of rank. The Emperor always outranked all of his fellow senators, and was followed by "Roman Consul

Beginning in 9 BC, an official list of senators (the album senatorium) was maintained and revised each year. Individuals were added to the list if they had recently satisfied the requirements for entry into the Senate, and were removed from the list if they no longer satisfied the requirements necessary to maintain senate membership. The list named each senator by order of rank. The Emperor always outranked all of his fellow senators, and was followed by "Roman Consul

s" (the highest ranking magistrate) and former Consuls, then by "Praetor

s" (the next highest ranking magistrate) and former Praetors, and so on. A senator's tenure in elective office was considered when determining rank, while senators who had been elected to an office did not necessarily outrank senators who had been appointed to that same office by the Emperor

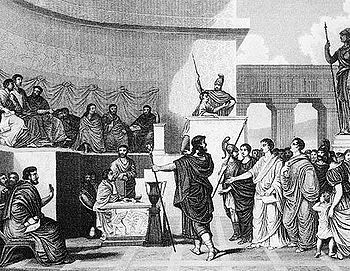

Under the Empire, the power that the Emperor held over the Senate was absolute, which was due, in part, to the fact that the Emperor held office for life. During senate meetings, the Emperor sat between the two Consuls, and usually acted as the presiding officer. Senators of the early Empire could ask extraneous questions or request that a certain action be taken by the Senate. Higher ranking senators spoke before lower ranking senators, although the Emperor could speak at any time. Besides the Emperor, Consuls and Praetors could also preside over the senate.

The Senate ordinarily met in the Curia Julia

, usually on either the Kalends

(the first day of the month), or the Ides

(around the fifteenth day of the month), although scheduled meetings occurred more frequently in September and October. Other meetings were held on an ad hoc

basis. Under Augustus, a quorum

was set at 400 senators, although eventually excessive absenteeism forced the senate to lower the number of senators necessary for a quorum, and, on some matters, to revoke the quorum rules altogether. Most of the bills that came before the Senate were presented by the Emperor, who had usually appointed a committee to draft each bill before presenting it. Since no senator could stand for election to a magisterial office without the Emperor's approval, senators usually did not vote against bills that had been presented by the Emperor. If a senator disapproved of a bill, he usually showed his disapproval by not attending the Senate meeting on the day that the bill was to be voted on. Each Emperor selected a Quaestor to compile the proceedings of the Senate into a document (the acta senatus), which included proposed bills, official documents, and a summary of speeches that had been presented before the Senate. The document was archived, while parts of it were published (in a document called the acta diurna

or "daily doings") and then distributed to the public.

While the Roman assemblies

While the Roman assemblies

continued to meet after the founding of the Empire, their powers were all transferred to the Senate, and so senatorial decrees (senatus consulta) acquired the full force of law. The legislative powers of the Imperial Senate were principally of a financial and an administrative nature, although the senate did retain a range of powers over the provinces. The Senate could also regulate festivals and religious cults, grant special honors, excuse an individual (usually the Emperor) from legal liability, manage temples and public games, and even enact tax laws (but only with the acquiescence of the Emperor). However, it had no real authority over either the state religion or over public lands.

During the early Roman Empire, all judicial powers that had been held by the Roman assemblies were also transferred to the Senate. For example, the senate now held jurisdiction over criminal trials. In these cases, a Consul presided, the senators constituted the jury, and the verdict was handed down in the form of a decree (senatus consultum), and, while a verdict could not be appealed, the Emperor could pardon a convicted individual through a veto. Each province that was under the jurisdiction of the Senate had its own court, and, upon the recommendation of a Consul, decisions of these provincial courts could be appealed to the Senate.

In theory, the Senate elected new emperors, while in conjunction with the popular assemblies, it would then confer upon the new emperor his command powers (imperium

). After an emperor had died or abdicated his office, the Senate would often deify him, although sometimes it would pass a decree (damnatio memoriae

or "damnation from memory") which would attempt to cancel every trace of that emperor from the life of Rome, as if he had never existed. The emperor Tiberius

transferred all electoral powers from the assemblies to the Senate, and, while theoretically the Senate elected new magistrates, the approval of the Emperor was always needed before an election could be finalized. Despite this fact, however, elections remained highly contested and vigorously fought.

Around 300 AD, the emperor Diocletian

enacted a series of constitutional reforms. In one such reform, Diocletian asserted the right of the Emperor to take power without the theoretical consent of the Senate, thus depriving the Senate of its status as the ultimate depository of supreme power. Diocletian's reforms also ended whatever illusion had remained that the Senate had independent legislative, judicial, or electoral powers. The Senate did, however, retain its legislative powers over public games in Rome, and over the senatorial order. The Senate also retained the power to try treason cases, and to elect some magistrates, but only with the permission of the Emperor. In the final years of the Empire, the Senate would sometimes try to appoint their own emperor, such as in case of Eugenius

who was later defeated by forces loyal to Theodosius I

. The Senate remained the last stronghold of the traditional Roman religion in the face of the spreading Christianity, and several times attempted to facilitate the return of the Altar of Victory

(first removed by Constantius II

) to the senatorial curia.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the Senate continued to function under the barbarian chieftain Odoacer

, and then under Theoderic the Great who founded the Ostrogothic Kingdom

. The authority of the Senate rose considerably under barbarian leaders who sought to protect the Senate. This period was characterized by the rise of prominent Roman senatorial families such as the Anicii, while the Senate's leader, the princeps senatus

, often served as the right hand of the barbarian leader. It is known that the Senate succeeded to install as pope Laurentius

in 498

despite the fact that both king Theodoric and Emperor Anastasius supported the other pretender, Symmachus

.

The peaceful co-existence of senatorial and barbarian rule continued until the Ostrogothic leader Theodahad

began an uprising against Emperor Justinian I

and took the senators as hostages. Several senators were executed in 552 as a revenge for the death of the Ostrogothic king Totila

. After Rome was recaptured by the Imperial (Byzantine

) army, the Senate was restored, but the institution (like classical Rome itself) had been mortally weakened by the long war between the Byzantines and the Ostrogoths. Many senators had been killed and many of those who had fled to the East chose to remain there thanks to favorable legislation passed by emperor Justinian, who however abolished virtually all senatorial offices in Italy. The importance of the Roman Senate thus declined rapidly. In 578 and again in 580, the Senate sent envoys to Constantinople which delivered 3000 pounds of gold as gift to the new emperor Tiberius II Constantinus along with a plea for help against the Langobards who had invaded Italy ten years earlier. Pope Gregory I, in a sermon from 593 (Senatus deest, or.18), lamented the almost complete disappearance of the senatorial order and the decline of the prestigious institution. It is not clearly known when the Roman Senate disappeared in the West, but it is known from Gregorian register that the Senate acclaimed new statues of Emperor Phocas

and Empress Leontia

in 603. The institution must have vanished by 630 when the Curia was transformed into a church by Pope Honorius I

. The Senate did continue to exist in the Eastern Roman Empire's capital Constantinople

, however, having been instituted there too during the reign of Constantine I

, and existed at least up to the mid-14th century before the ancient institution finally vanished from history.

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

. After the fall of the Roman Republic

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

, the constitutional balance of power shifted from the "Roman Senate

Roman Senate

The Senate of the Roman Republic was a political institution in the ancient Roman Republic, however, it was not an elected body, but one whose members were appointed by the consuls, and later by the censors. After a magistrate served his term in office, it usually was followed with automatic...

" to the "Roman Emperor

Roman Emperor

The Roman emperor was the ruler of the Roman State during the imperial period . The Romans had no single term for the office although at any given time, a given title was associated with the emperor...

". Beginning with the first emperor, Augustus

Augustus

Augustus ;23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14) is considered the first emperor of the Roman Empire, which he ruled alone from 27 BC until his death in 14 AD.The dates of his rule are contemporary dates; Augustus lived under two calendars, the Roman Republican until 45 BC, and the Julian...

, the Emperor and the Senate were technically two co-equal branches of government. In practice, however the actual authority of the imperial Senate was negligible, as the Emperor held the true power of the state. As such, membership in the Senate became sought after by individuals seeking prestige and social standing, rather than actual authority. During the reigns of the first Emperors, legislative, judicial, and electoral powers were all transferred from the "Roman assemblies

Roman assemblies

The Legislative Assemblies of the Roman Republic were political institutions in the ancient Roman Republic. According to the contemporary historian Polybius, it was the people who had the final say regarding the election of magistrates, the enactment of new statutes, the carrying out of capital...

" to the Senate. However, since the control that the Emperor held over the senate was absolute, the Senate acted as a vehicle through which the Emperor exercised his autocratic powers.

Procedure

The first emperor, Augustus, inherited a Senate whose membership had been increased to 900 senators by his predecessor, the "Roman DictatorRoman dictator

In the Roman Republic, the dictator , was an extraordinary magistrate with the absolute authority to perform tasks beyond the authority of the ordinary magistrate . The office of dictator was a legal innovation originally named Magister Populi , i.e...

" Julius Caesar

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar was a Roman general and statesman and a distinguished writer of Latin prose. He played a critical role in the gradual transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire....

. Augustus sought to reduce the size of the Senate, and did so through three revisions to the list of senators. By the time that these revisions had been completed, the Senate had been reduced to 600 members, and after this point, the size of the Senate was never again drastically altered. To reduce the size of the senate, Augustus expelled senators who were of low birth, and then he reformed the rules which specified how an individual could become a senator. Under Augustus' reforms, a senator had to be a citizen of free birth, and have property worth at least 1,000,000 sesterces.

Under the Empire, as was the case during the late Republic, one could become a senator by being elected "Quaestor

Quaestor

A Quaestor was a type of public official in the "Cursus honorum" system who supervised financial affairs. In the Roman Republic a quaestor was an elected official whereas, with the autocratic government of the Roman Empire, quaestors were simply appointed....

" (a magistrate with financial duties). Under the Empire, however, one could only stand for election to the Quaestor

Quaestor

A Quaestor was a type of public official in the "Cursus honorum" system who supervised financial affairs. In the Roman Republic a quaestor was an elected official whereas, with the autocratic government of the Roman Empire, quaestors were simply appointed....

ship if one was of senatorial rank, and to be of senatorial rank, one had to be the son of a senator. If an individual was not of senatorial rank, there were two ways for that individual to become a senator. Under the first method, the Emperor granted that individual the authority to stand for election to the Quaestorship, while under the second method, the Emperor appointed that individual to the senate by issuing a decree (the adlectio).

Roman consul

A consul served in the highest elected political office of the Roman Republic.Each year, two consuls were elected together, to serve for a one-year term. Each consul was given veto power over his colleague and the officials would alternate each month...

s" (the highest ranking magistrate) and former Consuls, then by "Praetor

Praetor

Praetor was a title granted by the government of Ancient Rome to men acting in one of two official capacities: the commander of an army, usually in the field, or the named commander before mustering the army; and an elected magistratus assigned varied duties...

s" (the next highest ranking magistrate) and former Praetors, and so on. A senator's tenure in elective office was considered when determining rank, while senators who had been elected to an office did not necessarily outrank senators who had been appointed to that same office by the Emperor

Under the Empire, the power that the Emperor held over the Senate was absolute, which was due, in part, to the fact that the Emperor held office for life. During senate meetings, the Emperor sat between the two Consuls, and usually acted as the presiding officer. Senators of the early Empire could ask extraneous questions or request that a certain action be taken by the Senate. Higher ranking senators spoke before lower ranking senators, although the Emperor could speak at any time. Besides the Emperor, Consuls and Praetors could also preside over the senate.

The Senate ordinarily met in the Curia Julia

Curia Julia

The Curia Hostilia was one of the original senate houses or 'curia' of the Roman Republic. It is believed to have begun as an Etruscan temple where the warring tribes laid down their arms during the reign of Romulus . During the early kingdom, the temple was for the use of the Senators who acted as...

, usually on either the Kalends

Kalends

The Calends , correspond to the first days of each month of the Roman calendar. The Romans assigned these calends to the first day of the month, signifying the start of the new moon cycle...

(the first day of the month), or the Ides

Ides

Ides may refer to:* Ides , a day in the Roman calendar that marked the approximate middle of the month* Specifically, Ides of March* Ides, a being in Germanic paganism* Saint Ides, an Irish saint...

(around the fifteenth day of the month), although scheduled meetings occurred more frequently in September and October. Other meetings were held on an ad hoc

Ad hoc

Ad hoc is a Latin phrase meaning "for this". It generally signifies a solution designed for a specific problem or task, non-generalizable, and not intended to be able to be adapted to other purposes. Compare A priori....

basis. Under Augustus, a quorum

Quorum

A quorum is the minimum number of members of a deliberative assembly necessary to conduct the business of that group...

was set at 400 senators, although eventually excessive absenteeism forced the senate to lower the number of senators necessary for a quorum, and, on some matters, to revoke the quorum rules altogether. Most of the bills that came before the Senate were presented by the Emperor, who had usually appointed a committee to draft each bill before presenting it. Since no senator could stand for election to a magisterial office without the Emperor's approval, senators usually did not vote against bills that had been presented by the Emperor. If a senator disapproved of a bill, he usually showed his disapproval by not attending the Senate meeting on the day that the bill was to be voted on. Each Emperor selected a Quaestor to compile the proceedings of the Senate into a document (the acta senatus), which included proposed bills, official documents, and a summary of speeches that had been presented before the Senate. The document was archived, while parts of it were published (in a document called the acta diurna

Acta Diurna

Acta Diurna were daily Roman official notices, a sort of daily gazette. They were carved on stone or metal and presented in message boards in public places like the Forum of Rome...

or "daily doings") and then distributed to the public.

Powers

Roman assemblies

The Legislative Assemblies of the Roman Republic were political institutions in the ancient Roman Republic. According to the contemporary historian Polybius, it was the people who had the final say regarding the election of magistrates, the enactment of new statutes, the carrying out of capital...

continued to meet after the founding of the Empire, their powers were all transferred to the Senate, and so senatorial decrees (senatus consulta) acquired the full force of law. The legislative powers of the Imperial Senate were principally of a financial and an administrative nature, although the senate did retain a range of powers over the provinces. The Senate could also regulate festivals and religious cults, grant special honors, excuse an individual (usually the Emperor) from legal liability, manage temples and public games, and even enact tax laws (but only with the acquiescence of the Emperor). However, it had no real authority over either the state religion or over public lands.

During the early Roman Empire, all judicial powers that had been held by the Roman assemblies were also transferred to the Senate. For example, the senate now held jurisdiction over criminal trials. In these cases, a Consul presided, the senators constituted the jury, and the verdict was handed down in the form of a decree (senatus consultum), and, while a verdict could not be appealed, the Emperor could pardon a convicted individual through a veto. Each province that was under the jurisdiction of the Senate had its own court, and, upon the recommendation of a Consul, decisions of these provincial courts could be appealed to the Senate.

In theory, the Senate elected new emperors, while in conjunction with the popular assemblies, it would then confer upon the new emperor his command powers (imperium

Imperium

Imperium is a Latin word which, in a broad sense, translates roughly as 'power to command'. In ancient Rome, different kinds of power or authority were distinguished by different terms. Imperium, referred to the sovereignty of the state over the individual...

). After an emperor had died or abdicated his office, the Senate would often deify him, although sometimes it would pass a decree (damnatio memoriae

Damnatio memoriae

Damnatio memoriae is the Latin phrase literally meaning "condemnation of memory" in the sense of a judgment that a person must not be remembered. It was a form of dishonor that could be passed by the Roman Senate upon traitors or others who brought discredit to the Roman State...

or "damnation from memory") which would attempt to cancel every trace of that emperor from the life of Rome, as if he had never existed. The emperor Tiberius

Tiberius

Tiberius , was Roman Emperor from 14 AD to 37 AD. Tiberius was by birth a Claudian, son of Tiberius Claudius Nero and Livia Drusilla. His mother divorced Nero and married Augustus in 39 BC, making him a step-son of Octavian...

transferred all electoral powers from the assemblies to the Senate, and, while theoretically the Senate elected new magistrates, the approval of the Emperor was always needed before an election could be finalized. Despite this fact, however, elections remained highly contested and vigorously fought.

Around 300 AD, the emperor Diocletian

Diocletian

Diocletian |latinized]] upon his accession to Diocletian . c. 22 December 244 – 3 December 311), was a Roman Emperor from 284 to 305....

enacted a series of constitutional reforms. In one such reform, Diocletian asserted the right of the Emperor to take power without the theoretical consent of the Senate, thus depriving the Senate of its status as the ultimate depository of supreme power. Diocletian's reforms also ended whatever illusion had remained that the Senate had independent legislative, judicial, or electoral powers. The Senate did, however, retain its legislative powers over public games in Rome, and over the senatorial order. The Senate also retained the power to try treason cases, and to elect some magistrates, but only with the permission of the Emperor. In the final years of the Empire, the Senate would sometimes try to appoint their own emperor, such as in case of Eugenius

Eugenius

Flavius Eugenius was an usurper in the Western Roman Empire against Emperor Theodosius I. Though himself a Christian, he was the last Emperor to support Roman polytheism.-Life:...

who was later defeated by forces loyal to Theodosius I

Theodosius I

Theodosius I , also known as Theodosius the Great, was Roman Emperor from 379 to 395. Theodosius was the last emperor to rule over both the eastern and the western halves of the Roman Empire. During his reign, the Goths secured control of Illyricum after the Gothic War, establishing their homeland...

. The Senate remained the last stronghold of the traditional Roman religion in the face of the spreading Christianity, and several times attempted to facilitate the return of the Altar of Victory

Altar of Victory

The Altar of Victory was located in the Roman Senate House bearing a gold statue of the goddess Victory. The altar was established by Octavian in 29 BC in honor of the defeat of Antony and Cleopatra at Actium. The statue depicted a winged woman, holding a palm and descending to present a laurel...

(first removed by Constantius II

Constantius II

Constantius II , was Roman Emperor from 337 to 361. The second son of Constantine I and Fausta, he ascended to the throne with his brothers Constantine II and Constans upon their father's death....

) to the senatorial curia.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the Senate continued to function under the barbarian chieftain Odoacer

Odoacer

Flavius Odoacer , also known as Flavius Odovacer, was the first King of Italy. His reign is commonly seen as marking the end of the Western Roman Empire. Though the real power in Italy was in his hands, he represented himself as the client of Julius Nepos and, after Nepos' death in 480, of the...

, and then under Theoderic the Great who founded the Ostrogothic Kingdom

Ostrogothic Kingdom

The Kingdom established by the Ostrogoths in Italy and neighbouring areas lasted from 493 to 553. In Italy the Ostrogoths replaced Odoacer, the de facto ruler of Italy who had deposed the last emperor of the Western Roman Empire in 476. The Gothic kingdom reached its zenith under the rule of its...

. The authority of the Senate rose considerably under barbarian leaders who sought to protect the Senate. This period was characterized by the rise of prominent Roman senatorial families such as the Anicii, while the Senate's leader, the princeps senatus

Princeps senatus

The princeps senatus was the first member by precedence of the Roman Senate. Although officially out of the cursus honorum and owning no imperium, this office brought enormous prestige to the senator holding it.-Overview:...

, often served as the right hand of the barbarian leader. It is known that the Senate succeeded to install as pope Laurentius

Antipope Laurentius

Laurentius was an antipope of the Roman Catholic Church, from 498 to 506.-Biography:Archpriest of Santa Prassede, Laurentius was elected pope on 22 November 498, in opposition to Symmachus, by a dissenting faction...

in 498

498

Year 498 was a common year starting on Thursday of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Paulinus and Scytha...

despite the fact that both king Theodoric and Emperor Anastasius supported the other pretender, Symmachus

Pope Symmachus

Saint Symmachus was pope from 498 to 514. His tenure was marked by a serious schism over who was legitimately elected pope by the citizens of Rome....

.

The peaceful co-existence of senatorial and barbarian rule continued until the Ostrogothic leader Theodahad

Theodahad

Theodahad was the King of the Ostrogoths from 534 to 536 and a nephew of Theodoric the Great through his sister Amalafrida. He might have arrived in Italy with Theodoric and was an elderly man at the time of his succession...

began an uprising against Emperor Justinian I

Justinian I

Justinian I ; , ; 483– 13 or 14 November 565), commonly known as Justinian the Great, was Byzantine Emperor from 527 to 565. During his reign, Justinian sought to revive the Empire's greatness and reconquer the lost western half of the classical Roman Empire.One of the most important figures of...

and took the senators as hostages. Several senators were executed in 552 as a revenge for the death of the Ostrogothic king Totila

Totila

Totila, original name Baduila was King of the Ostrogoths from 541 to 552 AD. A skilled military and political leader, Totila reversed the tide of Gothic War, recovering by 543 almost all the territories in Italy that the Eastern Roman Empire had captured from his Kingdom in 540.A relative of...

. After Rome was recaptured by the Imperial (Byzantine

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire was the Eastern Roman Empire during the periods of Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, centred on the capital of Constantinople. Known simply as the Roman Empire or Romania to its inhabitants and neighbours, the Empire was the direct continuation of the Ancient Roman State...

) army, the Senate was restored, but the institution (like classical Rome itself) had been mortally weakened by the long war between the Byzantines and the Ostrogoths. Many senators had been killed and many of those who had fled to the East chose to remain there thanks to favorable legislation passed by emperor Justinian, who however abolished virtually all senatorial offices in Italy. The importance of the Roman Senate thus declined rapidly. In 578 and again in 580, the Senate sent envoys to Constantinople which delivered 3000 pounds of gold as gift to the new emperor Tiberius II Constantinus along with a plea for help against the Langobards who had invaded Italy ten years earlier. Pope Gregory I, in a sermon from 593 (Senatus deest, or.18), lamented the almost complete disappearance of the senatorial order and the decline of the prestigious institution. It is not clearly known when the Roman Senate disappeared in the West, but it is known from Gregorian register that the Senate acclaimed new statues of Emperor Phocas

Phocas

Phocas was Byzantine Emperor from 602 to 610. He usurped the throne from the Emperor Maurice, and was himself overthrown by Heraclius after losing a civil war.-Origins:...

and Empress Leontia

Leontia

Leontia was the Empress consort of Phocas of the Byzantine Empire.-Empress:Maurice reigned in the Byzantine Empire from 582 to 602. He led a series of Balkan campaigns and managed to successfully re-establish the Danube as a northern border for his state. By Winter 602, his strategic goals included...

in 603. The institution must have vanished by 630 when the Curia was transformed into a church by Pope Honorius I

Pope Honorius I

Pope Honorius I was pope from 625 to 638.Honorius, according to the Liber Pontificalis, came from Campania and was the son of the consul Petronius. He became pope on October 27, 625, two days after the death of his predecessor, Boniface V...

. The Senate did continue to exist in the Eastern Roman Empire's capital Constantinople

Constantinople

Constantinople was the capital of the Roman, Eastern Roman, Byzantine, Latin, and Ottoman Empires. Throughout most of the Middle Ages, Constantinople was Europe's largest and wealthiest city.-Names:...

, however, having been instituted there too during the reign of Constantine I

Constantine I

Constantine the Great , also known as Constantine I or Saint Constantine, was Roman Emperor from 306 to 337. Well known for being the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity, Constantine and co-Emperor Licinius issued the Edict of Milan in 313, which proclaimed religious tolerance of all...

, and existed at least up to the mid-14th century before the ancient institution finally vanished from history.

See also

Primary sources

- Cicero's De Re Publica, Book Two

- Rome at the End of the Punic Wars: An Analysis of the Roman Government; by Polybius