The Great Game

Encyclopedia

Cold war (general term)

A cold war or cold warfare is a state of conflict between nations that does not involve direct military action but is pursued primarily through economic and political actions, propaganda, acts of espionage or proxy wars waged by surrogates...

between the British Empire

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

and the Russian Empire

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

for supremacy in Central Asia

Central Asia

Central Asia is a core region of the Asian continent from the Caspian Sea in the west, China in the east, Afghanistan in the south, and Russia in the north...

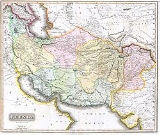

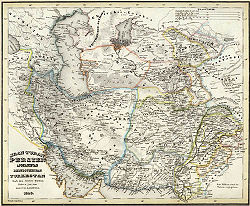

. The classic Great Game period is generally regarded as running approximately from the Russo-Persian Treaty of 1813 to the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907. A second, less intensive phase followed the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. The Great Game dwindled after the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

and the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

became Allies

Allies of World War II

The Allies of World War II were the countries that opposed the Axis powers during the Second World War . Former Axis states contributing to the Allied victory are not considered Allied states...

during World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

.

The term "The Great Game" is usually attributed to Arthur Conolly

Arthur Conolly

Arthur Conolly was a British intelligence officer, explorer and writer. He was a captain of the 1st Bengal Light Cavalry in the service of the British East India Company...

(1807–1842), an intelligence officer

Intelligence officer

An intelligence officer is a person employed by an organization to collect, compile and/or analyze information which is of use to that organization...

of the British East India Company

British East India Company

The East India Company was an early English joint-stock company that was formed initially for pursuing trade with the East Indies, but that ended up trading mainly with the Indian subcontinent and China...

's Sixth Bengal Light Cavalry. It was introduced into mainstream consciousness by British

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

novelist Rudyard Kipling

Rudyard Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling was an English poet, short-story writer, and novelist chiefly remembered for his celebration of British imperialism, tales and poems of British soldiers in India, and his tales for children. Kipling received the 1907 Nobel Prize for Literature...

in his novel Kim

Kim (novel)

Kim is a picaresque novel by Rudyard Kipling. It was first published serially in McClure's Magazine from December 1900 to October 1901 as well as in Cassell's Magazine from January to November 1901, and first published in book form by Macmillan & Co. Ltd in October 1901...

(1901).

British-Russian rivalry in Afghanistan

British India (disambiguation)

The Presidencies and provinces of British India, collectively known as "British India", were the administrative units of the territories of India between 1612 and 1947...

. The British feared that Afghanistan

Emirate of Afghanistan

The Emirate of Afghanistan began with the end of the Durrani Empire and the reign of Dost Mohammad Khan in 1823 and ended when Amir Amanullah Khan became Shah in 1926. This period was characterized by the expansion of European colonial interests in Central Asia...

would become a staging post for a Russian invasion of India, after the Tsar's troops would subdue the Central Asian khanate

Khanate

Khanate, or Chanat, is a Turco-Mongol-originated word used to describe a political entity ruled by a Khan. In modern Turkish, the word used is kağanlık, and in modern Azeri of the republic of Azerbaijan, xanlıq. In Mongolian the word khanlig is used, as in "Khereidiin Khanlig" meaning the Khanate...

s (Khiva, Bokhara, Khokand) one after another.

It was with these thoughts in mind that in 1838 the British launched the First Anglo-Afghan War

First Anglo-Afghan War

The First Anglo-Afghan War was fought between British India and Afghanistan from 1839 to 1842. It was one of the first major conflicts during the Great Game, the 19th century competition for power and influence in Central Asia between the United Kingdom and Russia, and also marked one of the worst...

and attempted to impose a puppet regime on Afghanistan under Shuja Shah. The regime was short lived and proved unsustainable without British military support. By 1842, mobs were attacking the British on the streets of Kabul

Kabul

Kabul , spelt Caubul in some classic literatures, is the capital and largest city of Afghanistan. It is also the capital of the Kabul Province, located in the eastern section of Afghanistan...

and the British garrison was forced to abandon the city due to constant civilian attacks.

The retreating British army consisted of approximately 4,500 troops (of which only 690 were European) and 12,000 camp follower

Camp follower

Camp-follower is a term used to identify civilians and their children who follow armies. There are two common types of camp followers; first, the wives and children of soldiers, who follow their spouse or parent's army from place to place; the second type of camp followers have historically been...

s. During a series of attacks by Afghan warriors, all Europeans but one, William Brydon

William Brydon

William Brydon CB was an assistant surgeon in the British East India Company Army during the First Anglo-Afghan War and is famous for being the only member of an army of 4,500 men to reach safety in Jalalabad at the end of the long retreat from Kabul.He was born in London of Scottish descent...

, were killed on the march back to India

Massacre of Elphinstone's Army

The Massacre of Elphinstone's Army was the destruction by Afghan forces, led by Akbar Khan, the son of Dost Mohammad Khan, of a combined British and Indian force of the British East India Company, led by Major General William Elphinstone, in January 1842....

; a few Indian soldiers survived also and crossed into India later. The British curbed their ambitions in Afghanistan following this humiliating retreat from Kabul.

After the Indian rebellion of 1857

Indian Rebellion of 1857

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 began as a mutiny of sepoys of the British East India Company's army on 10 May 1857, in the town of Meerut, and soon escalated into other mutinies and civilian rebellions largely in the upper Gangetic plain and central India, with the major hostilities confined to...

, successive British governments saw Afghanistan as a buffer state

Buffer state

A buffer state is a country lying between two rival or potentially hostile greater powers, which by its sheer existence is thought to prevent conflict between them. Buffer states, when authentically independent, typically pursue a neutralist foreign policy, which distinguishes them from satellite...

. The Russians, led by Konstantin Kaufman, Mikhail Skobelev

Mikhail Skobelev

Mikhail Dmitrievich Skobelev was a Russian general famous for his conquest of Central Asia and heroism during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78. Dressed in white uniform and mounted on a white horse, and always in the thickest of the fray, he was known and adored by his soldiers as the "White...

, and Mikhail Chernyayev

Mikhail Chernyayev

Mikhail Grigorievich Chernyayev was a Russian general, who, together with Konstantin Kaufman and Mikhail Skobelev, led the Russian conquest of Central Asia under Alexander II....

, continued to advance steadily southward through Central Asia towards Afghanistan, and by 1865 Tashkent

Tashkent

Tashkent is the capital of Uzbekistan and of the Tashkent Province. The officially registered population of the city in 2008 was about 2.2 million. Unofficial sources estimate the actual population may be as much as 4.45 million.-Early Islamic History:...

had been formally annexed

Annexation

Annexation is the de jure incorporation of some territory into another geo-political entity . Usually, it is implied that the territory and population being annexed is the smaller, more peripheral, and weaker of the two merging entities, barring physical size...

.

Samarkand

Samarkand

Although a Persian-speaking region, it was not united politically with Iran most of the times between the disintegration of the Seleucid Empire and the Arab conquest . In the 6th century it was within the domain of the Turkic kingdom of the Göktürks.At the start of the 8th century Samarkand came...

became part of the Russian Empire in 1868, and the independence of Bukhara

Emirate of Bukhara

The Emirate of Bukhara was a Central Asian state that existed from 1785 to 1920. It occupied the land between the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers, known formerly as Transoxiana. Its core territory was the land along the lower Zarafshan River, and its urban centres were the ancient cities of...

was virtually stripped away in a peace treaty the same year. Russian control now extended as far as the northern bank of the Amu Darya

Amu Darya

The Amu Darya , also called Oxus and Amu River, is a major river in Central Asia. It is formed by the junction of the Vakhsh and Panj rivers...

river.

In a letter to Queen Victoria, Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli proposed "to clear Central Asia of Muscovites and drive them into the Caspian

Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the largest enclosed body of water on Earth by area, variously classed as the world's largest lake or a full-fledged sea. The sea has a surface area of and a volume of...

". He introduced the Royal Titles Act 1876

Royal Titles Act 1876

The Royal Titles Act of 1876 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which officially recognized Queen Victoria as "Empress of India". This title had been assumed by her in 1876, under the encouragement of the Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli...

, which added to Victoria's titles that of Empress of India, putting her at the same level as the Russian Emperor.

Diplomatic mission

A diplomatic mission is a group of people from one state or an international inter-governmental organisation present in another state to represent the sending state/organisation in the receiving state...

to Kabul in 1878, Britain demanded that the ruler of Afghanistan, Sher Ali

Sher Ali Khan

Sher Ali Khan was Amir of Afghanistan from 1863 to 1866 and from 1868 until his death in 1879. He was the third son of Dost Mohammed Khan, founder of the Barakzai Dynasty in Afghanistan....

, accept a British diplomatic mission. The mission was turned back, and in retaliation a force of 40,000 men was sent across the border, launching the Second Anglo-Afghan War

Second Anglo-Afghan War

The Second Anglo-Afghan War was fought between the United Kingdom and Afghanistan from 1878 to 1880, when the nation was ruled by Sher Ali Khan of the Barakzai dynasty, the son of former Emir Dost Mohammad Khan. This was the second time British India invaded Afghanistan. The war ended in a manner...

. The war's conclusion left Abdur Rahman Khan

Abdur Rahman Khan

Abdur Rahman Khan was Emir of Afghanistan from 1880 to 1901.The third son of Mohammad Afzal Khan, and grandson of Dost Mohammad Khan, Abdur Rahman Khan was considered a strong ruler who re-established the writ of the Afghan government in Kabul after the disarray that followed the second...

on the throne, and he agreed to let the British control Afghanistan's foreign affairs, while he consolidated his position on the throne. He managed to suppress internal rebellions with ruthless efficiency and brought much of the country under central control.

In 1884, Russian expansionism brought about another crisis — the Panjdeh Incident

Panjdeh Incident

The Panjdeh Incident or Panjdeh Scare was a battle that occurred in 1885 when Russian forces seized Afghan territory south of the Oxus River around an oasis at Panjdeh . The incident created a diplomatic crisis between Russia and Great Britain...

— when they seized the oasis

Oasis

In geography, an oasis or cienega is an isolated area of vegetation in a desert, typically surrounding a spring or similar water source...

of Merv

Merv

Merv , formerly Achaemenid Satrapy of Margiana, and later Alexandria and Antiochia in Margiana , was a major oasis-city in Central Asia, on the historical Silk Road, located near today's Mary in Turkmenistan. Several cities have existed on this site, which is significant for the interchange of...

. The Russians claimed all of the former ruler's territory and fought with Afghan troops over the oasis of Panjdeh. On the brink of war between the two great powers, the British decided to accept the Russian possession of territory north of the Amu Darya as a fait accompli

Fait Accompli

Fait accompli is a French phrase which means literally "an accomplished deed". It is commonly used to describe an action which is completed before those affected by it are in a position to query or reverse it...

.

Without any Afghan say in the matter, between 1885 and 1888 the Joint Anglo-Russian Boundary Commission agreed the Russians would relinquish the farthest territory captured in their advance, but retain Panjdeh. The agreement delineated a permanent northern Afghan frontier at the Amu Darya, with the loss of a large amount of territory, especially around Panjdeh.

This left the border east of Zorkul

Zorkul

Zorkul is a lake in the Pamir Mountains that runs along the border between Afghanistan and Tajikistan. It extends east to west for about 25 km. The Afghan-Tajik border runs along the lake from east to west, turning south towards Concord Peak , about 15 km south of the lake. The lake's northern...

lake in the Wakhan

Wakhan

Wakhan or "the Wakhan" is a very mountainous and rugged part of the Pamir and Karakoram regions of Afghanistan. Wakhan District is a district in Badakshan Province.-Geography:...

. Territory in this area was claimed by Russia, Afghanistan and China

Qing Dynasty

The Qing Dynasty was the last dynasty of China, ruling from 1644 to 1912 with a brief, abortive restoration in 1917. It was preceded by the Ming Dynasty and followed by the Republic of China....

. In the 1880s the Afghans advanced north of the lake to the Alichur Pamir. In 1891, Russia sent a military force to the Wakhan and provoked a diplomatic incident by ordering the British Captain Francis Younghusband

Francis Younghusband

Lieutenant Colonel Sir Francis Edward Younghusband, KCSI, KCIE was a British Army officer, explorer, and spiritual writer...

to leave Bozai Gumbaz in the Little Pamir

Little Pamir

The Little Pamir is a broad U-shaped grassy valley or pamir in the eastern part of the Wakhan in north-eastern Afghanistan...

. This incident, and the report of an incursion by Russian Cossacks south of the Hindu Kush, led the British to suspect Russian involvement "with the Rulers of the petty States on the northern boundary of Kashmir and Jammu". This was the reason for the Hunza-Nagar Campaign in 1891, after which the British established control over Hunza and Nagar. In 1892 the British sent the Earl of Dunmore

Charles Murray, 7th Earl of Dunmore

Charles Adolphus Murray, 7th Earl of Dunmore VD , styled Viscount Fincastle from birth until 1845, was a Scottish peer and Conservative politician.-Background:...

to the Pamirs to investigate. Britain was concerned that Russia would take advantage of Chinese weakness in policing the area to gain territory, and in 1893 reached agreement with Russia to demarcate the rest of the border, a process completed in 1895.

Great Game moves eastward

By the 1890s, the Central Asian khanates of KhivaKhanate of Khiva

The Khanate of Khiva was the name of a Uzbek state that existed in the historical region of Khwarezm from 1511 to 1920, except for a period of Persian occupation by Nadir Shah between 1740–1746. It was the patrilineal descendants of Shayban , the fifth son of Jochi and grandson of Genghis Khan...

, Bukhara

Emirate of Bukhara

The Emirate of Bukhara was a Central Asian state that existed from 1785 to 1920. It occupied the land between the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers, known formerly as Transoxiana. Its core territory was the land along the lower Zarafshan River, and its urban centres were the ancient cities of...

and Kokand

Khanate of Kokand

The Khanate of Kokand was a state in Central Asia that existed from 1709–1883 within the territory of modern eastern Uzbekistan, southern Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan...

had fallen, becoming Russian vassals. With Central Asia in the Tsar's grip, the Great Game now shifted eastward to China, Mongolia and Tibet. In 1904, the British invaded Lhasa, a preemptive strike against Russian intrigues and secret meetings between the 13th Dalai Lama's envoy and Tsar Nicholas II. The Dalai Lama fled into exile to China and Mongolia. The British were petrified at the idea of a Russian invasion of their crown colony of India, though Russia – badly defeated by Japan in the Russo-Japanese war

Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War was "the first great war of the 20th century." It grew out of rival imperial ambitions of the Russian Empire and Japanese Empire over Manchuria and Korea...

and weakened by internal rebellion – could not realistically afford a showdown against Britain there. China, however, was another matter.

The Middle Kingdom had badly atrophied under the Manchus, the ruling ethnic caste of the Qing Dynasty

Qing Dynasty

The Qing Dynasty was the last dynasty of China, ruling from 1644 to 1912 with a brief, abortive restoration in 1917. It was preceded by the Ming Dynasty and followed by the Republic of China....

. Two-and-a-half centuries of decadent living, internecine feuds and imperviousness to a changing world had weakened the Empire. China’s weaponry and military tactics were outdated, even medieval. Modern factories, steel bridges, railways and telegraphs were almost nonexistent in most regions. Natural disasters, famine and internal rebellions had further enfeebled China. In the late 19th century, Japan and the Great Powers easily carved out trade and territorial concessions. These were humiliating submissions for the once all-powerful Manchus. Still, the central lesson of the war with Japan was not lost on the Russian General Staff: an Asian country using Western technology and industrial production methods could defeat a great European power.

In 1906, Tsar Nicholas II sent a secret agent to China to collect intelligence on the reform and modernization of the Qing Dynasty

Qing Dynasty

The Qing Dynasty was the last dynasty of China, ruling from 1644 to 1912 with a brief, abortive restoration in 1917. It was preceded by the Ming Dynasty and followed by the Republic of China....

. The task was given to Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim

Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim

Baron Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim was the military leader of the Whites in the Finnish Civil War, Commander-in-Chief of Finland's Defence Forces during World War II, Marshal of Finland, and a Finnish statesman. He was Regent of Finland and the sixth President of Finland...

, at the time a colonel in the Russian army, who travelled to China with French sinologist Paul Pelliot

Paul Pelliot

Paul Pelliot was a French sinologist and explorer of Central Asia. Initially intending to enter the foreign service, Pelliot took up the study of Chinese and became a pupil of Sylvain Lévi and Édouard Chavannes....

. Mannerheim was disguised as an ethnographic collector, using a Finnish passport. For two years, Mannerheim proceeded through Xinjiang

Xinjiang

Xinjiang is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China. It is the largest Chinese administrative division and spans over 1.6 million km2...

, Gansu

Gansu

' is a province located in the northwest of the People's Republic of China.It lies between the Tibetan and Huangtu plateaus, and borders Mongolia, Inner Mongolia, and Ningxia to the north, Xinjiang and Qinghai to the west, Sichuan to the south, and Shaanxi to the east...

, Shaanxi

Shaanxi

' is a province in the central part of Mainland China, and it includes portions of the Loess Plateau on the middle reaches of the Yellow River in addition to the Qinling Mountains across the southern part of this province...

, Henan

Henan

Henan , is a province of the People's Republic of China, located in the central part of the country. Its one-character abbreviation is "豫" , named after Yuzhou , a Han Dynasty state that included parts of Henan...

, Shanxi

Shanxi

' is a province in Northern China. Its one-character abbreviation is "晋" , after the state of Jin that existed here during the Spring and Autumn Period....

and Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China, located in the northern region of the country. Inner Mongolia shares an international border with the countries of Mongolia and the Russian Federation...

to Beijing

Beijing

Beijing , also known as Peking , is the capital of the People's Republic of China and one of the most populous cities in the world, with a population of 19,612,368 as of 2010. The city is the country's political, cultural, and educational center, and home to the headquarters for most of China's...

. At the sacred Buddhist mountain of Wutai Shan

Wutai Shan

Mount Wutai , also known as Wutai Mountain or Qingliang Shan, is located in Shanxi, China. The mountain is home to many of China's most important monasteries and temples...

he even met the 13th Dalai Lama. However, while Mannerheim was in China in 1907, Russia and Britain brokered the Anglo-Russian Agreement, ending the Great Game.

Anglo-Russian Alliance

In the run-up to World War IWorld War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, both empires were alarmed by Germany

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

's increasing activity in the Middle East

Middle East

The Middle East is a region that encompasses Western Asia and Northern Africa. It is often used as a synonym for Near East, in opposition to Far East...

, notably the German project of the Baghdad Railway

Baghdad Railway

The Baghdad Railway , was built from 1903 to 1940 to connect Berlin with the Ottoman Empire city of Baghdad with a line through modern-day Turkey, Syria, and Iraq....

, which would open up Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a toponym for the area of the Tigris–Euphrates river system, largely corresponding to modern-day Iraq, northeastern Syria, southeastern Turkey and southwestern Iran.Widely considered to be the cradle of civilization, Bronze Age Mesopotamia included Sumer and the...

and Persia to German trade and technology. The ministers Alexander Izvolsky and Edward Grey

Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon

Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon KG, PC, FZL, DL , better known as Sir Edward Grey, Bt, was a British Liberal statesman. He served as Foreign Secretary from 1905 to 1916, the longest continuous tenure of any person in that office...

agreed to resolve their long-standing conflicts in Asia in order to make an effective stand against the German advance into the region. The Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907

Anglo-Russian Entente

Signed on August 31, 1907, in St. Petersburg, Russia, the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 brought shaky British-Russian relations to the forefront by solidifying boundaries that identified respective control in Persia, Afghanistan, and Tibet...

brought a close to the classic period of the Great Game.

The Russians accepted that the politics of Afghanistan were solely under British control as long as the British guaranteed not to change the regime. Russia agreed to conduct all political relations with Afghanistan through the British. The British agreed that they would maintain the current borders and actively discourage any attempt by Afghanistan to encroach on Russian territory. Persia was divided into three zones: a British zone in the south, a Russian zone in the north, and a narrow neutral zone serving as buffer in between.

In regards to Tibet, both powers agreed to maintain territorial integrity of this buffer state

Buffer state

A buffer state is a country lying between two rival or potentially hostile greater powers, which by its sheer existence is thought to prevent conflict between them. Buffer states, when authentically independent, typically pursue a neutralist foreign policy, which distinguishes them from satellite...

and "to deal with Lhasa

Lhasa

Lhasa is the administrative capital of the Tibet Autonomous Region in the People's Republic of China and the second most populous city on the Tibetan Plateau, after Xining. At an altitude of , Lhasa is one of the highest cities in the world...

only through China

China

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

, the suzerain power".

Criticism

Gerald Morgan’s Myth and Reality in the Great Game approached the subject by examining various departments of the Raj to determine if there ever existed a British intelligence network in Central Asia. Morgan wrote that evidence of such a network did not exist. At best, efforts to obtain information on Russian moves in Central Asia were rare, ad hoc adventures. At worst, intrigues resembling the adventures in Kim were baseless rumours and Morgan writes such rumours “were always common currency in Central Asia and they applied as much to Russia as to Britain.”In his lecture “The Legend of the Great Game”, Malcolm Yapp said that Britons had used the term “The Great Game” in the late 19th century to describe several different things in relation to its interests in Asia. Yapp believes that the primary concern of British authorities in India was control of the indigenous population, not preventing a Russian invasion.

According to Yapp, “reading the history of the British Empire in India and the Middle East one is struck by both the prominence and the unreality of strategic debates.”

British-Soviet rivalry in Afghanistan

The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 nullified existing treaties and a second phase of the Great Game began. The Third Anglo-Afghan WarThird Anglo-Afghan War

The Third Anglo-Afghan War began on 6 May 1919 and ended with an armistice on 8 August 1919. It was a minor tactical victory for the British. For the British, the Durand Line was reaffirmed as the political boundary between the Emirate of Afghanistan and British India and the Afghans agreed not to...

of 1919 was precipitated by the assassination of the then ruler Habibullah Khan. His son and successor Amanullah declared full independence and attacked British India's northern frontier. Although little was gained militarily, the stalemate was resolved with the Rawalpindi Agreement

Treaty of Rawalpindi

The Treaty of Rawalpindi was an armistice made between the United Kingdom and Afghanistan during the Third Anglo-Afghan War...

of 1919. Afghanistan re-established its self-determination

Self-determination

Self-determination is the principle in international law that nations have the right to freely choose their sovereignty and international political status with no external compulsion or external interference...

in foreign affairs.

In May 1921, Afghanistan and the Russian Soviet Republic signed a Treaty of Friendship. The Soviets provided Amanullah with aid in the form of cash, technology, and military equipment. British influence in Afghanistan waned, but relations between Afghanistan and the Russians remained equivocal, with many Afghans desiring to regain control of Merv and Panjdeh. The Soviets, for their part, desired to extract more from the friendship treaty than Amanullah was willing to give.

The United Kingdom imposed minor sanctions and diplomatic slights as a response to the treaty, fearing that Amanullah was slipping out of their sphere of influence and realising that the policy of the Afghanistan government was to have control of all of the Pashtun speaking groups on both sides of the Durand Line

Durand Line

The Durand Line refers to the porous international border between Pakistan and Afghanistan, which has divided the ethnic Pashtuns . This poorly marked line is approximately long...

. In 1923, Amanullah responded by taking the title padshah

Padishah

Padishah, Padshah, Padeshah, Badishah or Badshah is a superlative royal title, composed of the Persian pād "master" and the widespread shāh "king", which was adopted by several monarchs claiming the highest rank, roughly equivalent to the ancient Persian notion of "The Great" or "Great King", and...

– "king" – and by offering refuge for Muslims who fled the Soviet Union, and Indian nationalists in exile from the Raj.

Amanullah's programme of reform was, however, insufficient to strengthen the army quickly enough; in 1928 he abdicated under pressure. The individual who most benefited from the crisis was Mohammed Nadir Shah

Mohammed Nadir Shah

Mohammed Nadir Shah was King of Afghanistan from 15 October 1929 until his assassination in 1933. Previously, he served as Minister of War, Afghan Ambassador to France, and as a general in the military of Afghanistan...

, who reigned from 1929 to 1933. Both the Soviets and the British played the circumstances to their advantage: the Soviets getting aid in dealing with Uzbek rebellion in 1930 and 1931, while the British aided Afghanistan in creating a 40,000 man professional army.

With the advent of World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

came the temporary alignment of British and Soviet interests: in 1940, both governments pressured Afghanistan for the expulsion of a large German non-diplomatic contingent, which both governments believed to be engaging in espionage. Afghanistan complied in 1941. With this period of cooperation between the USSR and the UK, the Great Game between the two powers came to an end.

Twenty-first century

Recently there has been some use of the expression "the Great Game" to describe relations between the United StatesUnited States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, Russia

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

, the People's Republic of China

People's Republic of China

China , officially the People's Republic of China , is the most populous country in the world, with over 1.3 billion citizens. Located in East Asia, the country covers approximately 9.6 million square kilometres...

and other nations such as Pakistan

Pakistan

Pakistan , officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan is a sovereign state in South Asia. It has a coastline along the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Oman in the south and is bordered by Afghanistan and Iran in the west, India in the east and China in the far northeast. In the north, Tajikistan...

and Turkey

Turkey

Turkey , known officially as the Republic of Turkey , is a Eurasian country located in Western Asia and in East Thrace in Southeastern Europe...

, over influence with the Central Asian republics and access to energy resources and military bases. The accuracy of this comparison is debated.

While energy resources and military bases are mentioned as part of The Great Game, so is the continuing jostling for strategic advantage between great powers and between the regional powers in mountainous border regions in the Himalayas.

In popular culture

- KimKim (novel)Kim is a picaresque novel by Rudyard Kipling. It was first published serially in McClure's Magazine from December 1900 to October 1901 as well as in Cassell's Magazine from January to November 1901, and first published in book form by Macmillan & Co. Ltd in October 1901...

by Rudyard KiplingRudyard KiplingJoseph Rudyard Kipling was an English poet, short-story writer, and novelist chiefly remembered for his celebration of British imperialism, tales and poems of British soldiers in India, and his tales for children. Kipling received the 1907 Nobel Prize for Literature... - The Lotus and the WindThe Lotus and the WindThe Lotus and the Wind is a spy novel by John Masters. It continues his saga of the Savage family, who are part of the British Raj in India, and is set against the backdrop of the Great Game, the period of tension between Britain and Russia in Central Asia during the late nineteenth century.-Plot...

by John MastersJohn MastersLieutenant Colonel John Masters, DSO was an English officer in the British Indian Army and novelist. His works are noted for their treatment of the British Empire in India.-Life:... - FlashmanFlashman (novel)Flashman is a 1969 novel by George MacDonald Fraser. It is the first of the Flashman novels.-Plot introduction:Presented within the frame of the supposedly discovered historical Flashman Papers, this book describes the bully Flashman from Tom Brown's Schooldays...

by George MacDonald FraserGeorge MacDonald FraserGeorge MacDonald Fraser, OBE was an English-born author of Scottish descent, who wrote both historical novels and non-fiction books, as well as several screenplays.-Early life and military career:... - Flashman at the ChargeFlashman at the ChargeFlashman at the Charge is a 1973 novel by George MacDonald Fraser. It is the fourth of the Flashman novels. Playboy magazine serialized Flashman at the Charge in 1973 in their April, May and June issues...

by George MacDonald FraserGeorge MacDonald FraserGeorge MacDonald Fraser, OBE was an English-born author of Scottish descent, who wrote both historical novels and non-fiction books, as well as several screenplays.-Early life and military career:... - Flashman in the Great GameFlashman in the Great GameFlashman in the Great Game is a 1975 novel by George MacDonald Fraser. It is the fifth of the Flashman novels.-Plot introduction:Presented within the frame of the supposedly discovered historical Flashman Papers, this book describes the bully Flashman from Tom Brown's Schooldays...

by George MacDonald FraserGeorge MacDonald FraserGeorge MacDonald Fraser, OBE was an English-born author of Scottish descent, who wrote both historical novels and non-fiction books, as well as several screenplays.-Early life and military career:...

(1999) ISBN 0-00-651299-2 - The Game by Laurie R. KingLaurie R. KingLaurie R. King is an American author best known for her detective fiction. Among her books are the Mary Russell series of historical mysteries, featuring Sherlock Holmes as her mentor and later partner, and a series featuring Kate Martinelli, a fictional lesbian San Francisco, California, police...

(2004), a Sherlock HolmesSherlock HolmesSherlock Holmes is a fictional detective created by Scottish author and physician Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. The fantastic London-based "consulting detective", Holmes is famous for his astute logical reasoning, his ability to take almost any disguise, and his use of forensic science skills to solve...

pastichePasticheA pastiche is a literary or other artistic genre or technique that is a "hodge-podge" or imitation. The word is also a linguistic term used to describe an early stage in the development of a pidgin language.-Hodge-podge:...

, one of the Mary Russell series. ISBN 0-553-80194-5 - The song "Pink India" from musician Stephen MalkmusStephen MalkmusStephen Joseph Malkmus is an indie rock musician and icon, and a member of the band Pavement. He currently performs with Stephen Malkmus and the Jicks.-Early years:...

' self-titled albumStephen Malkmus (album)Stephen Malkmus is the debut album by the group Stephen Malkmus and the Jicks. It was released by Matador Records on February 13, 2001. Malkmus had planned to create the record by himself, or through a smaller, local label, but eventually accepted the offer Matador asked, and he released it. It...

. - The documentary The Devil's Wind by Iqbal Malhotra.

- Afuganisu-tan a Webcomic by Japanese manga artist, Timaking

- DeclareDeclareDeclare is a supernatural spy novel by Tim Powers. It presents a secret history of the Cold War in which an agent for a secret British spy organization learns the true nature of several beings living on Mount Ararat. In this he is opposed by real-life communist traitor Kim Philby, who did travel...

by Tim PowersTim PowersTimothy Thomas "Tim" Powers is an American science fiction and fantasy author. Powers has won the World Fantasy Award twice for his critically acclaimed novels Last Call and Declare... - The Far PavilionsThe Far PavilionsThe Far Pavilions is an epic novel of British-Indian history by M. M. Kaye, first published in 1978, which tells the story of an English officer during the Great Game. The novel, rooted deeply in the romantic epics of the 19th century, has been hailed as a masterpiece of storytelling...

by M. M. KayeM. M. KayeMary Margaret Kaye was a British writer. Her most famous book was The Far Pavilions .-Life:M. M. Kaye was born in Simla, India, and spent her early childhood and much of her early-married life there...

Viking Press, LLC, New York, 1978

See also

- Anglo-Russian relations

- Anglo-Soviet invasion of IranAnglo-Soviet invasion of IranThe Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran was the Allied invasion of the Imperial State of Iran during World War II, by British, Commonwealth, and Soviet armed forces. The invasion from August 25 to September 17, 1941, was codenamed Operation Countenance...

- Geostrategy in Central AsiaGeostrategy in Central AsiaCentral Asia has long been a geostrategic location because of its proximity to the interests of several great powers.-Strategic geography:...

- Iran-Britain relations

- Russian explorers

- The Great Game (book)The Great Game (book)The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia is a historical book by Peter Hopkirk.-Description:In this work, the author relates the story of a time best described by Captain Arthur Connolly, of the East India Company before he was beheaded in Bokhara for spying in 1842, as the "Great...

- Imperialism in AsiaImperialism in AsiaImperialism in Asia traces its roots back to the late 15th century with a series of voyages that sought a sea passage to India in the hope of establishing direct trade between Europe and Asia in spices. Before 1500 European economies were largely self-sufficient, only supplemented by minor trade...