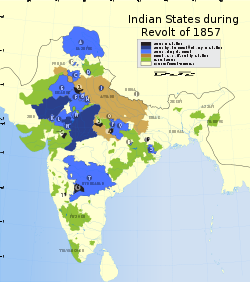

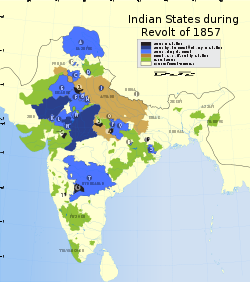

Indian Rebellion of 1857

Encyclopedia

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 began as a mutiny

of sepoy

s of the British East India Company

's army on 10 May 1857, in the town of Meerut, and soon escalated into other mutinies and civilian rebellions largely in the upper Gangetic plain

and central India, with the major hostilities confined to present-day Uttar Pradesh

, Bihar

, northern Madhya Pradesh

, and the Delhi

region. The rebellion posed a considerable threat to Company power in that region, and it was contained only with the fall of Gwalior

on 20 June 1858. The rebellion is also known as the 1857 War of Independence, India's First War of Independence

, the Great Rebellion, the Indian Mutiny, the Revolt of 1857, the Uprising of 1857, the Sepoy Rebellion, and the Sepoy Mutiny.

Other regions of Company-controlled India – such as Bengal

, the Bombay Presidency

, and the Madras Presidency

– remained largely calm. In Punjab, the Sikh

princes backed the Company by providing both soldiers and support. The large princely states of Hyderabad

, Mysore

, Travancore

, and Kashmir

, as well as the smaller ones of Rajputana

, did not join the rebellion. In some regions, such as Oudh

, the rebellion took on the attributes of a patriotic revolt against European presence. Rebel leaders, such as the Lakshmibai, the Rani of Jhansi

, became folk heroes in the nationalist movement in India

half a century later; however, they themselves "generated no coherent ideology" for a new order. The rebellion led to the dissolution of the East India Company in 1858. It also led the British to reorganise the army, the financial system and the administration in India. India was thereafter directly governed by the crown

as the new British Raj

.

had earlier administered the factory areas established for trading purposes, its victory in the Battle of Plassey

in 1757 marked the beginning of its firm foothold in Eastern India. The victory was consolidated in 1764 at the Battle of Buxar

(in Bihar

), when the defeated Mughal

emperor, Shah Alam II

, granted the Company the right for "collection of Revenue" in the provinces of Bengal

, Bihar, and Orissa

. The Company soon expanded its territories around its bases in Bombay and Madras; the Anglo-Mysore Wars

(1766–1799) and the Anglo-Maratha Wars

(1772–1818) led to control of the vast region of India south of the Narmada River

.

The expansion did not occur without resistance. In 1806 the Vellore Mutiny

was sparked due to new uniform regulations that created resentment amongst both Hindu and Muslim sepoys.

After the turn of the 19th century, Governor-General Wellesley

began what became two decades of accelerated expansion of Company territories. This was achieved either by subsidiary alliance

s between the Company and local rulers or by direct military annexation. The subsidiary alliances created the princely states (or native states) of the Hindu maharaja

s and the Muslim nawab

s. Punjab

, North-West Frontier Province

, and Kashmir

were annexed after the Second Anglo-Sikh War

in 1849; however, Kashmir was immediately sold under the Treaty of Amritsar

(1850) to the Dogra Dynasty of Jammu

and thereby became a princely state. The border dispute between Nepal and British India, which sharpened after 1801, had caused the Anglo-Nepalese War of 1814–16 and brought the Gurkhas under British influence. In 1854, Berar

was annexed, and the state of Oudh was added two years later. For practical purposes, the Company was the government of much of India.

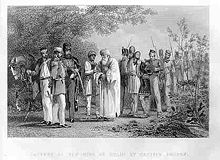

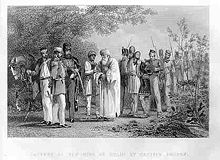

The sepoy

s were Indian soldiers, both Hindu and Muslim, that were recruited into the Company's army. Just before the Rebellion there were over 200,000 Indians in the army, compared to about 50,000 British. The forces were divided into three presidency armies

: Bombay

, Madras

, and Bengal

. The Bengal Army

recruited higher castes

, such as "Rajput

s and Brahmins", mostly from the Awadh

(near Lucknow

) and Bihar

regions and even restricted the enlistment of lower castes in 1855. In contrast, the Madras Army

and Bombay Army

were "more localized, caste-neutral armies" that "did not prefer high-caste men." The domination of higher castes in the Bengal Army has been blamed in part for initial mutinies that led to the rebellion. In fact, the role of castes had become so important that men were no longer “selected on account of the most important qualities in a soldier, i.e., physical fitness, willingness and strength, docility and courage, but because he belonged to a certain caste or sect”.

In 1772, when Warren Hastings

was appointed India's first Governor-General

, one of his first undertakings was the rapid expansion of the Company’s army. Since the sepoys from Bengal – many of whom had fought against the Company in the Battles of Plassey and Buxar – were now suspect in British eyes, Hastings recruited farther west from the high-caste rural Rajputs and Brahmins of Awadh and Bihar, a practice that continued for the next 75 years. However, in order to forestall any social friction, the Company also took pains to adapt its military practices to the requirements of their religious rituals. Consequently, these soldiers dined in separate facilities; in addition, overseas service, considered polluting to their caste, was not required of them, and the army soon came officially to recognize Hindu festivals. “This encouragement of high caste ritual status, however, left the government vulnerable to protest, even mutiny, whenever the sepoys detected infringement of their prerogatives.”

It has been suggested that after the annexation of Oudh by the East India Company in 1856, many sepoys were disquieted both from losing their perquisites, as landed gentry, in the Oudh courts and from the anticipation of any increased land-revenue payments that the annexation might bring about. Others have stressed that by 1857, some Indian soldiers, reading the presence of missionaries as a sign of official intent, were convinced that the Company was masterminding mass conversions of Hindus and Muslims to Christianity. Although earlier in the 1830s, evangelists such as William Carey and William Wilberforce

had successfully clamored for the passage of social reform such as the abolition of sati

and allowing the remarriage of Hindu widows, there is little evidence that the sepoys' allegiance was affected by this.

However, changes in the terms of their professional service may have created resentment. As the extent of the East India Company's jurisdiction expanded with victories in wars or with annexation, the soldiers were now not only expected to serve in less familiar regions (such as in Burma in the Anglo-Burmese Wars in 1856), but also make do without the "foreign service" remuneration that had previously been their due. Another financial grievance stemmed from the general service act, which denied retired sepoys a pension; whilst this only applied to new recruits, it was suspected that it would also apply to those already in service. In addition, the Bengal Army was paid less than the Madras and Bombay Armies, which compounded the fears over pensions.

A major cause of resentment that arose ten months prior to the outbreak of the Rebellion was the General Service Enlistment Act of 25 July 1856. As noted above, men of the Bengal Army had been exempted from overseas service. Specifically they were enlisted only for service in territories to which they could march. Governor-General Lord Dalhousie

saw this as an anomaly, since all sepoys of the Madras and Bombay Armies (plus six "General Service" battalions of the Bengal Army) had accepted an obligation to serve overseas if required. As a result the burden of providing contingents for active service in Burma (readily accessible only by sea) and China

had fallen disproportionately on the two smaller Presidency Armies. As signed into effect by Lord Canning

, Dalhousie's successor as Governor-General, the Act required only new recruits to the Bengal Army to accept a commitment for general (that is overseas) service. However, serving high-caste sepoys were fearful that it would be eventually extended to them, as well as preventing sons following fathers into an Army with a strong tradition of family service.

There were also grievances over the issue of promotions, based on seniority. This, as well as the increasing number of European officers in the battalions, made promotion a slow progress, and many Indian officers did not reach commissioned rank until they were too old to be effective.

Rifle. These rifles had a tighter fit, and used paper cartridge

s that came pre-greased. To load the rifle, sepoys had to bite the cartridge

open to release the powder. Now, the grease used on these cartridges included tallow

, which if derived from pork would be offensive to Muslims, and if derived from beef would be offensive to Hindus. At least one British official pointed out the difficulties this may cause:

However, in August 1856, greased cartridge production was initiated at Fort William

, Calcutta, following British design. The grease used included tallow supplied by the Indian firm of Gangadarh Banerji & Co. By January, the rumours were abroad that the Enfield cartridges were greased with animal fat.

Company officers became aware of the rumours through reports of an altercation between a high-caste sepoy and a low-caste labourer at Dum Dum

. The labourer had taunted the sepoy that by biting the cartridge, he had himself lost caste, although at this time such cartridges had been issued only at Meerut and not at Dum Dum.

On 27 January, Colonel Richard Birch, the Military Secretary, ordered that all cartridges issued from depots were to be free from grease, and that sepoys could grease them themselves using whatever mixture "they may prefer". A modification was also made to the drill for loading so that the cartridge was torn with the hands and not bitten. This however, merely caused many sepoys to be convinced that the rumours were true and that their fears were justified. Additional rumours started that the paper in the new cartridges, which was glazed and stiffer than the previously used paper, was impregnated with grease.

, which refused to recognize the adopted children of princes as legal heirs, felt that the Company had interfered with a traditional system of inheritance. Rebel leaders such as Nana Sahib and the Rani of Jhansi belonged to this group; the latter, for example, was prepared to accept East India Company supremacy if her adopted son was recognized as her late husband's heir. In other areas of central India, such as Indore

and Saugar, where such loss of privilege had not occurred, the princes remained loyal to the Company even in areas where the sepoys had rebelled. The second group, the taluqdars, had lost half their landed estates to peasant farmers as a result of the land reforms that came in the wake of annexation of Oudh. As the rebellion gained ground, the taluqdars quickly reoccupied the lands they had lost, and paradoxically, in part due to ties of kinship and feudal loyalty, did not experience significant opposition from the peasant farmers, many of whom joined the rebellion, to the great dismay of the British. It has also been suggested that heavy land-revenue assessment in some areas by the British resulted in many landowning families either losing their land or going into great debt with money lenders, and providing ultimately a reason to rebel; money lenders, in addition to the Company, were particular objects of the rebels' animosity. The civilian rebellion was also highly uneven in its geographic distribution, even in areas of north-central India that were no longer under British control. For example, the relatively prosperous Muzaffarnagar

district, a beneficiary of a Company irrigation scheme, and next door to Meerut, where the upheaval began, stayed mostly calm throughout.

Image:Charles Canning, 1st Earl Canning - Project Gutenberg eText 16528.jpg|Charles Canning

, the Governor-General of India

during the rebellion.

Image:Dalhousie.jpg|Lord Dalhousie

, the Governor-General of India from 1848 to 1856, who devised the Doctrine of Lapse

.

File:Rani of jhansi.jpg|Lakshmibai, The Rani of Jhansi

, one of the principal leaders of the rebellion who earlier had lost her kingdom as a result of the Doctrine of Lapse

.

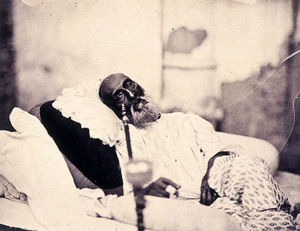

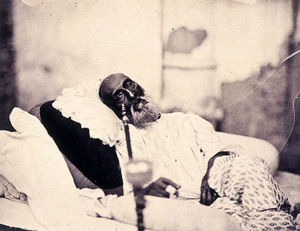

Image:Bahadur Shah II - aka Zafar - Project Gutenberg eText 17711.jpg|Bahadur Shah Zafar the last Mughal Emperor, crowned Emperor of India, by the Indian troops, he was deposed by the British, and died in exile in Burma

Much of the resistance to the Company came from the old aristocracy, who were seeing their power steadily eroded. The company had annexed several states under the Doctrine of Lapse, according to which land belonging to a feudal ruler became the property of the East India Company if on his death, the ruler did not leave a male heir through natural process. It had long been the custom for a childless landowner to adopt an heir, but the East India Company ignored this tradition. Nobility, feudal landholders, and royal armies found themselves unemployed and humiliated due to Company expansionism. Even the jewels of the royal family of Nagpur

were publicly auctioned in Calcutta, a move that was seen as a sign of abject disrespect by the remnants of the Indian aristocracy. Lord Dalhousie

, the Governor-General of India, had asked the Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar and his successors to leave the Red Fort, the palace in Delhi

. Later, Lord Canning, the next Governor-General of India, announced in 1856 that Bahadur Shah's successors would not even be allowed to use the title of 'king'. Such discourtesies were resented by the deposed Indian rulers.

"Utilitarian and evangelical

"Utilitarian and evangelical

-inspired social reform", including the abolition of sati and the legalisation of widow remarriage were considered by many—especially the British themselves—to have caused suspicion that Indian religious traditions were being "interfered with", with the ultimate aim of conversion. Recent historians, including Chris Bayly, have preferred to frame this as a "clash of knowledges", with proclamations from religious authorities before the revolt and testimony after it including on such issues as the "insults to women", the rise of "low persons

under British tutelage", the "pollution" caused by Western medicine and the persecuting and ignoring of traditional astrological authorities. European-run schools were also a problem: according to recorded testimonies, anger had spread because of stories that mathematics was replacing religious instruction, stories were chosen that would "bring contempt" upon Indian religions, and because girl children were exposed to "moral danger" by education.

The justice system was considered to be inherently unfair to the Indians. The official Blue Books, East India (Torture) 1855–1857, laid before the House of Commons

during the sessions of 1856 and 1857 revealed that Company officers were allowed an extended series of appeals if convicted or accused of brutality or crimes against Indians.

The economic policies of the East India Company were also resented by many Indians..

s (the native Indian soldiers) were therefore affected to a large degree by the concerns of the landholding and traditional members of Indian society. In the early years of the Company rule, they tolerated and even encouraged the caste privileges and customs within the Bengal Army, which recruited its regular soldiers almost exclusively amongst the landowning Bhumihar

Brahmin

s and Rajput

s of the Ganges Valley. By the time these customs and privileges came to be threatened by modernizing regimes in Calcutta from the 1840s onwards, the sepoys had become accustomed to very high ritual status, and were extremely sensitive to suggestions that their caste might be polluted.

The sepoys also gradually became dissatisfied with various other aspects of army life. Their pay was relatively low and after Awadh

and the Punjab

were annexed, the soldiers no longer received extra pay (batta or bhatta) for service there, because they were no longer considered "foreign missions". The junior European officers were increasingly estranged from their soldiers, in many cases treating them as their racial inferiors. Officers of an evangelical persuasion in the Company's Army (such as Herbert Edwardes and Colonel S.G. Wheler of the 34th Bengal Infantry) had taken to preaching to their sepoys in the hope of converting them to Christianity. In 1856, a new Enlistment Act was introduced by the Company, which in theory made every unit in the Bengal Army liable to service overseas. (Although it was intended to apply to new recruits only, the sepoys feared that the Act might be applied retrospectively to them as well. It was argued that a high-caste Hindu who traveled in the cramped, squalid conditions of a troop ship would find it impossible to avoid losing caste through ritual pollution.)

(BNI) regiment became concerned that new cartridges they had been issued were wrapped in paper greased with cow and pig fat, which had to be opened by mouth thus affecting their religious sensibilities. Their Colonel confronted them supported by artillery and cavalry on the parade ground, but after some negotiation withdrew the artillery, and cancel the next morning's parade.

On 29 March 1857 at the Barrackpore (now Barrackpur) parade ground, near Calcutta (now Kolkata

On 29 March 1857 at the Barrackpore (now Barrackpur) parade ground, near Calcutta (now Kolkata

), 29-year-old Mangal Pandey

of the 34th BNI, angered by the recent actions by the East India Company, declared that he would rebel against his commanders. Informed about Pandey's apparently drug induced behaviour Sergeant-Major James Hewson went to investigate only to have Pandey shoot at him. Hewson raised the alarm. When his adjutant

Lt. Henry Baugh came out to investigate the unrest, Pandey opened fire but hit his horse instead.

General John Hearsey came out to see him on the parade ground, and claimed later that Mangal Pandey was in some kind of "religious frenzy". He ordered the Indian commander of the quarter guard

Jemadar

Ishwari Prasad to arrest Mangal Pandey, but the Jemadar refused. The quarter guard and other sepoys present, with the single exception of a soldier called Shaikh Paltu

, drew back from restraining or arresting Mangal Pandey. Shaikh Paltu restrained Pandey from continuing his attack.

After failing to incite his comrades into an open and active rebellion, Mangal Pandey tried to take his own life by placing his musket to his chest, and pulling the trigger with his toe. He only managed to wound himself, and was court-martialled on 6 April. He was hanged on 8 April.

The Jemadar Ishwari Prasad was sentenced to death and hanged on 22 April. The regiment was disbanded and stripped of their uniforms because it was felt that they harboured ill-feelings towards their superiors, particularly after this incident. Shaikh Paltu was promoted to the rank of Jemadar

in the Bengal Army.

Sepoys in other regiments thought this as a very harsh punishment. The show of disgrace while disbanding contributed to the extent of the rebellion in view of some historians, as disgruntled ex-sepoys returned home to Awadh with a desire to inflict revenge, as and when the opportunity arose.

, Allahabad

and Ambala

. At Ambala in particular, which was a large military cantonment where several units had been collected for their annual musketry practice, it was clear to General Anson, Commander-in-Chief of the Bengal Army, that some sort of riot over the cartridges was imminent. Despite the objections of the civilian Governor-General's staff, he agreed to postpone the musketry practice, and allow a new drill by which the soldiers tore the cartridges with their fingers rather than their teeth. However, he issued no general orders making this standard practice throughout the Bengal Army and, rather than remain at Ambala to defuse or overawe potential trouble, he then proceeded to Simla

, the cool "hill station" where many high officials spent the summer.

Although there was no open revolt at Ambala, there was widespread arson during late April. Barrack buildings (especially those belonging to soldiers who had used the Enfield cartridges) and European officers' bungalows were set on fire.

At Meerut was another large military cantonment. 2,357 Indian sepoys and 2,038 British troops with 12 British-manned guns were stationed there. Meerut was the station for one of the largest concentrations of British troops in India and this was later to be cited as evidence that the original rising was a spontaneous outbreak rather than a pre-planned plot.

At Meerut was another large military cantonment. 2,357 Indian sepoys and 2,038 British troops with 12 British-manned guns were stationed there. Meerut was the station for one of the largest concentrations of British troops in India and this was later to be cited as evidence that the original rising was a spontaneous outbreak rather than a pre-planned plot.

Although the state of unrest within the Bengal Army was well known, on 24 April Lieutenant Colonel George Carmichael-Smyth, the unsympathetic commanding officer of the 3rd Bengal Light Cavalry, ordered 90 of his men to parade and perform firing drills. All except five of the men on parade refused to accept their cartridges. On 9 May, the remaining 85 men were court martialled, and most were sentenced to 10 years' imprisonment with hard labour. Eleven comparatively young soldiers were given five years' imprisonment. The entire garrison was paraded and watched as the condemned men were stripped of their uniforms and placed in shackles. As they were marched off to jail, the condemned soldiers berated their comrades for failing to support them.

The next day was Sunday, the Christian day of rest and worship. Some Indian soldiers warned off-duty junior European officers (including Hugh Gough

, then a lieutenant of horse) that plans were afoot to release the imprisoned soldiers by force, but the senior officers to whom this was reported in turn took no action. There was also unrest in the city of Meerut itself, with angry protests in the bazaar and some buildings being set on fire. In the evening, most European officers were preparing to attend church, while many of the European soldiers were off duty and had gone into canteens or into the bazaar in Meerut. The Indian troops, led by the 3rd Cavalry, broke into revolt. European junior officers who attempted to quell the first outbreaks were killed by their own men. European officers' and civilians' quarters were attacked, and four civilian men, eight women and eight children were killed. Crowds in the bazaar attacked the off-duty soldiers there. About 50 Indian civilians (some of whom were officers' servants who tried to defend or conceal their employers) were also killed by the sepoys.

Within the city of Meerut, the Kotwal

(holder of the fort) Dhan Singh Gurjar

opened the gate of the jail. A total of about 50 European men (including soldiers), women and children were killed in Meerut by sepoys and crowds. on the evening of 10 May. The sepoys freed their 85 imprisoned comrades from the jail, along with 800 other prisoners (debtors and criminals).

Some sepoys (especially from the 11th Bengal Native Infantry) escorted trusted British officers and women and children to safety before joining the revolt. Some officers and their families escaped to Rampur

, where they found refuge with the Nawab.

The senior Company officers, in particular Major General Hewitt, the commander of the division (who was nearly 70 years old and in poor health), were slow to react. The British troops (mainly the 1st Battalion of the 60th Rifles

, the 6th Dragoon Guards and two European-manned batteries of the Bengal Artillery) rallied, but received no orders to engage the rebellious sepoys and could only guard their own headquarters and armouries. On the following morning when they prepared to attack, they found Meerut was quiet and that the rebels had marched off to Delhi.

The British historian Philip Mason notes that it was inevitable that most of the sepoys and sowars from Meerut should have made for Delhi on the night of 10 May. It was a strong walled city located only forty miles away, it was the ancient capital and present seat of the Mughal Emperor and finally there were no British troops in garrison there (by contrast with the relatively strong concentration at Meerut). What no-one could have anticipated was that no effort was made to pursue them.

s from Chandrawal

, led by Chaudhry Daya Ram, destroyed the house of Chief Magistrate Theophilus Metcalfe. European officials and dependents, Indian Christians and shop keepers within the city were killed, some by sepoys and others by crowds of rioters.

There were three battalions of Bengal Native Infantry stationed in or near the city. Some detachments quickly joined the rebellion, while others held back but also refused to obey orders to take action against the rebels. In the afternoon, a violent explosion in the city was heard for several miles. Fearing that the arsenal, which contained large stocks of arms and ammunition, would fall intact into rebel hands, the nine British Ordnance officers there had opened fire on the sepoys, including the men of their own guard. When resistance appeared hopeless, they blew up the arsenal. Although six of the nine officers survived, the blast killed many in the streets and nearby houses and other buildings. The news of these events finally tipped the sepoys stationed around Delhi into open rebellion. The sepoys were later able to salvage at least some arms from the arsenal, and a magazine two miles (3 km) outside Delhi, containing up to 3,000 barrels of gunpowder, was captured without resistance.

There were three battalions of Bengal Native Infantry stationed in or near the city. Some detachments quickly joined the rebellion, while others held back but also refused to obey orders to take action against the rebels. In the afternoon, a violent explosion in the city was heard for several miles. Fearing that the arsenal, which contained large stocks of arms and ammunition, would fall intact into rebel hands, the nine British Ordnance officers there had opened fire on the sepoys, including the men of their own guard. When resistance appeared hopeless, they blew up the arsenal. Although six of the nine officers survived, the blast killed many in the streets and nearby houses and other buildings. The news of these events finally tipped the sepoys stationed around Delhi into open rebellion. The sepoys were later able to salvage at least some arms from the arsenal, and a magazine two miles (3 km) outside Delhi, containing up to 3,000 barrels of gunpowder, was captured without resistance.

Many fugitive European officers and civilians had congregated at the Flagstaff Tower on the ridge north of Delhi, where telegraph operators were sending news of the events to other British stations. When it became clear that the help expected from Meerut was not coming, they made their way in carriages to Karnal

. Those who became separated from the main body or who could not reach the Flagstaff Tower also set out for Karnal on foot. Some were helped by villagers on the way, others were robbed or murdered.

The next day, Bahadur Shah held his first formal court for many years. It was attended by many excited or unruly sepoys. The King was alarmed by the turn events had taken, but eventually accepted the sepoys' allegiance and agreed to give his countenance to the rebellion. On 16 May, up to 50 Europeans who had been held prisoner in the palace or had been discovered hiding in the city were said to have been killed by some of the King's servants under a peepul tree in a courtyard outside the palace.

The news of the events at Delhi spread rapidly, provoking uprisings among sepoys and disturbances in many districts. In many cases, it was the behaviour of British military and civilian authorities themselves which precipitated disorder. Learning of the fall of Delhi by telegraph, many Company administrators hastened to remove themselves, their families and servants to places of safety. At Agra

The news of the events at Delhi spread rapidly, provoking uprisings among sepoys and disturbances in many districts. In many cases, it was the behaviour of British military and civilian authorities themselves which precipitated disorder. Learning of the fall of Delhi by telegraph, many Company administrators hastened to remove themselves, their families and servants to places of safety. At Agra

, 160 miles (257.5 km) from Delhi, no less than 6,000 assorted non-combatants converged on the Fort

. The haste with which many civilians left their posts encouraged rebellions in the areas they left, although others remained at their posts until it was clearly impossible to maintain any sort of order. Several were murdered by rebels or lawless gangs.

The military authorities also reacted in disjointed manner. Some officers trusted their sepoys, but others tried to disarm them to forestall potential uprisings. At Benares

and Allahabad

, the disarmings were bungled, also leading to local revolts.

Although rebellion became widespread, there was little unity among the rebels. While Bahadur Shah Zafar was restored to the imperial throne there was a faction that wanted the Maratha

rulers to be enthroned also, and the Awadh

is wanted to retain the powers that their Nawab used to have.

There were calls for jihad

by Muslim leaders like Maulana Fazl-e-Haq Khairabadi

and the millenarian Ahmedullah Shah, which were taken up by Muslims, particularly artisans, which caused the British to think that the Muslims were the main force behind this event. The Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah, resisted these calls for jihad because, it has been suggested, he feared outbreaks of communal violence. In Awadh

, Sunni Muslims did not want to see a return to Shiite rule, so they often refused to join what they perceived to be a Shia rebellion. However, some Muslims like the Aga Khan

supported the British. The British rewarded him by formally recognizing his title.

Although most of the rebellious sepoys in Delhi were Hindus, a significant proportion of the insurgents were Muslims. The proportion of ghazis grew to be about a quarter of the local fighting force by the end of the siege, and included a regiment of suicide ghazis from Gwalior who had vowed never to eat again and to fight until they met certain death at the hands of British troops.

In Thana Bhawan

, the Sunnis declared Haji Imdadullah their Ameer

. In May 1857 the Battle of Shamli took place between the forces of Haji Imdadullah and the British.

The Sikhs and Pathans of the Punjab

and North-West Frontier Province

supported the British and helped in the recapture of Delhi. Historian John Harris has asserted that the Sikhs wanted to avenge the annexation of the Sikh Empire eight years earlier by the Company with the help of Purabias ('Easterners'); Biharis and those from the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh

who had formed part of the East India Company's armies in the First

and Second

Anglo-Sikh Wars. He has also suggested that Sikhs felt insulted by the attitude of sepoys who (in their view) had only beaten the Khalsa

with British help; they resented and despised them far more than they did the British.

According to Hugh K. Trevaskis, Sikh support for the British resulted from grievances surrounding Sepoys' perceived conduct during and after the Anglo-Sikh Wars. Firstly, many Sikhs resented that Hindustanis in service of the Sikh state had been foremost in urging the wars which lost them their independence. Sikh soldiers also recalled that the bloodiest battles of the war, Chillianwala

and Ferozeshah

, were won by British troops, and they believed that the Hindustani sepoys had refused to meet them in battle. These feelings were compounded when Hindustani Sepoys were assigned a very visible role as garrison troops in Punjab and awarded profit-making civil posts in Punjab.

In 1857, the Bengal Army had 86,000 men of which 12,000 were European, 16,000 Sikh and 1,500 Gurkha soldiers, out of a total of (for the three Indian armies) 311,000 native troops, and 40,160 European troops as well as 5,362 officers. Fifty-four of the Bengal Army's 75 regular Native Infantry Regiments rebelled, although some were immediately destroyed or broke up with their sepoys drifting away to their homes. A number of the remaining 21 regiments were disarmed or disbanded to prevent or forestall rebellion. In total only twelve of the original Bengal Native Infantry regiments survived to pass into the new Indian Army All ten of the Bengal Light Cavalry regiments rebelled.

The Bengal Army also included 29 Irregular Cavalry and 42 Irregular Infantry regiments. These included a substantial contingent from the recently annexed state of Awadh, which rebelled en masse. Another large contingent from Gwalior also rebelled, even though that state's ruler remained allied to the British. The remainder of the Irregular units were raised from a wide variety of sources and were less affected by the concerns of mainstream Indian society. Three bodies in particular actively supported the Company; three Gurkha and five of six Sikh infantry units, and the six infantry and six cavalry units of the recently raised Punjab Irregular Force.

On 1 April 1858, the number of Indian soldiers in the Bengal army loyal to the Company was 80,053. This total included a large number of soldiers hastily raised in the Punjab and North-West Frontier after the outbreak of the Rebellion. The Bombay army had three mutinies in its 29 regiments whilst the Madras army had no mutinies, though elements of one of its 52 regiments refused to volunteer for service in Bengal. Most of southern India remained passive with only sporadic and haphazard outbreaks of violence. Most of the states did not take part in the war as many parts of the region were ruled by the Nizam

s or the Mysore royalty and were thus not directly under British rule.

was proclaimed the Emperor of the whole of India. Most contemporary and modern accounts suggest that he was coerced by the sepoys and his courtiers to sign the proclamation against his will. In spite of the significant loss of power that the Mughal dynasty had suffered in the preceding centuries, their name still carried great prestige across northern India. The civilians, nobility and other dignitaries took the oath of allegiance to the Emperor. The British, who had long ceased to take the authority of the Mughal Emperor seriously were astonished at how the ordinary people responded to Zafar's call for war. The Emperor issued coins in his name, one of the oldest ways of asserting Imperial status, and his name was added to the acceptance by Muslims that he is their King. This proclamation, however, turned the Sikh

s of Punjab

away from the rebellion, as they did not want to return to Islamic rule, having fought many wars against the Mughal

rulers. The province of Bengal

was largely quiet throughout the entire period.

Initially, the Indian soldiers were able to significantly push back Company forces, and captured several important towns in Haryana

, Bihar, Central Provinces

and the United Provinces

. When the European troops were reinforced and began to counterattack, the sepoys who mutinied were especially handicapped by their lack of a centralised command and control system. Although they produced some natural leaders such as Bakht Khan

(whom the Emperor later nominated as commander-in-chief after his son Mirza Mughal

proved ineffectual), for the most part they were forced to look for leadership to rajahs and princes. Some of these were to prove dedicated leaders, but others were self-interested or inept.

In the countryside around Meerut, a general Gurjar uprising posed the largest threat to the British. In Parikshitgarh

near Meerut, Gurjars declared Choudhari Kadam Singh (Kuddum Singh) their leader, and expelled Company police. Kadam Singh Gurjar led a large army of men, estimates varying from 2,000 to 10,000. Bulandshahr and Bijnor

also came under the control of Gurjars under the leaders Walidad Khan and Maho Singh respectively. Contemporary sources report that nearly all the Gurjar villages in the area between Meerut and Delhi

participated in the revolt, in some cases accompanied by mutinying sepoys from Jullundur

, and it was not until late July that, with the help of the Jats of the area, the British managed to regain control of the area.

The Imperial Gazetteer of India

states that throughout the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the Gurjars and Ranghars (Muslim rajpoots) proved the "most irreconcilable enemies" of the British in the Bulandshahr

area.

Mufti

Nizamuddin, a renowned scholar of Rewari

, issued a Fatwa

against the British forces and called upon the local population to support the forces of Rao Tula Ram

. Many people were killed in the fight at Narnaul (Nasibpur). After the defeat of Rao Tula Ram on 16 November 1857, Mufti Nizamuddin was arrested, and his brother Mufti Yaqinuddin and brother-in-law Abdur Rahman (alias Nabi Baksh) were arrested in Tijara

. They were taken to Delhi and hanged. Having lost the fight at Nasibpur, Rao Tula Ram and Pran Sukh Yadav

went to obtain arms from Russia

which had just been engaged against Britain in the Crimean War

.

from the Crimean War

, and some regiments already en route for China were diverted to India.

It took time to organize the European troops already in India into field forces, but eventually two columns left Meerut and Simla

. They proceeded slowly towards Delhi and fought, killed, and hanged numerous Indians along the way. Two months after the first outbreak of rebellion at Meerut, the two forces met near Karnal

. The combined force (which included two Gurkha

units serving in the Bengal Army under contract from the Kingdom of Nepal

), fought the main army of the rebels at Badli-ke-Serai

and drove them back to Delhi.

The Company established a base on the Delhi ridge to the north of the city and the Siege of Delhi

began. The siege lasted roughly from 1 July to 21 September. However, the encirclement was hardly complete, and for much of the siege the Company forces were outnumbered and it often seemed that it was the Company forces and not Delhi that was under siege, as the rebels could easily receive resources and reinforcements. For several weeks, it seemed that disease, exhaustion and continuous sorties by rebels from Delhi would force the Company forces to withdraw, but the outbreaks of rebellion in the Punjab

were forestalled or suppressed, allowing the Punjab Movable Column of British, Sikh and Pakhtun soldiers under John Nicholson

to reinforce the besiegers on the Ridge on 14 August. On 30 August the rebels offered terms, which were refused.

Image:1857 ruins jantar mantar observatory2.jpg|The Jantar Mantar observatory in Delhi in 1858, damaged in the fighting

Image:1857 cashmeri gate delhi2.jpg|Mortar damage to Kashmiri Gate

, Delhi, 1858

Image:1857 hindu raos house2.jpg|Hindu Rao

's house in Delhi, now a hospital, was extensively damaged in the fighting

Image:1857 bank of delhi2.jpg|Bank of Delhi was attacked by mortar and gunfire

An eagerly awaited heavy siege train joined the besieging force, and from 7 September, the siege guns battered breaches in the walls and silenced the rebels' artillery. An attempt to storm the city through the breaches and the Kashmiri Gate

was launched on 14 September. The attackers gained a foothold within the city but suffered heavy casualties, including John Nicholson. The British commander wished to withdraw, but was persuaded to hold on by his junior officers. After a week of street fighting, the British reached the Red Fort. Bahadur Shah Zafar had already fled to Humayun's tomb

. The British had retaken the city.

The troops of the besieging force proceeded to loot and pillage the city. A large number of the citizens were killed in retaliation for the Europeans and Indian civilians that had been killed by the rebel sepoys. During the street fighting, artillery had been set up in the main mosque in the city and the neighbourhoods within range were bombarded. These included the homes of the Muslim nobility from all over India, and contained innumerable cultural, artistic, literary and monetary riches.

The troops of the besieging force proceeded to loot and pillage the city. A large number of the citizens were killed in retaliation for the Europeans and Indian civilians that had been killed by the rebel sepoys. During the street fighting, artillery had been set up in the main mosque in the city and the neighbourhoods within range were bombarded. These included the homes of the Muslim nobility from all over India, and contained innumerable cultural, artistic, literary and monetary riches.

The British soon arrested Bahadur Shah, and the next day British officer William Hodson

shot his sons Mirza Mughal, Mirza Khazir Sultan, and grandson Mirza Abu Bakr under his own authority at the Khooni Darwaza

(the bloody gate) near Delhi Gate. On hearing the news Zafar reacted with shocked silence while his wife Zinat Mahal was happy as she believed her son was now Zafar's heir.

Shortly after the fall of Delhi, the victorious attackers organised a column which relieved another besieged Company force in Agra

, and then pressed on to Cawnpore, which had also recently been recaptured. This gave the Company forces a continuous, although still tenuous, line of communication from the east to west of India.

In June, sepoys under General Wheeler

In June, sepoys under General Wheeler

in Cawnpore (present day Kanpur) rebelled and besieged the European entrenchment. Wheeler was not only a veteran and respected soldier, but also married to a high-caste Indian lady. He had relied on his own prestige, and his cordial relations with the Nana Sahib to thwart rebellion, and took comparatively few measures to prepare fortifications and lay in supplies and ammunition.

The besieged endured three weeks of the Siege of Cawnpore

with little water or food, suffering continuous casualties to men, women and children. On 25 June Nana Sahib made an offer of safe passage to Allahabad. With barely three days' food rations remaining, the British agreed provided they could keep their small arms and that the evacuation should take place in daylight on the morning of the 27th (the Nana Sahib wanted the evacuation to take place on the night of the 26th). Early in the morning of 27 June, the European party left their entrenchment and made their way to the river where boats provided by the Nana Sahib were waiting to take them to Allahabad

. Several sepoys who had stayed loyal to the Company were removed by the mutineers and killed, either because of their loyalty or because "they had become Christian." A few injured British officers trailing the column were also apparently hacked to death by angry sepoys. After the European party had largely arrived at the dock, which was surrounded by sepoys positioned on both banks of the Ganges, with clear lines of fire, firing broke out and the boats were abandoned by their crew, and caught or were set on fire using pieces of red hot charcoal. The British party tried to push the boats off but all except three remained stuck. One boat with over a dozen wounded men initially escaped, but later grounded, was caught by mutineers and pushed back down the river towards the carnage at Cawnpore. Towards the end rebel cavalry rode into the water to finish off any survivors. After the firing ceased the survivors were rounded up and the men shot. By the time the massacre was over, most of the male members of the party were dead while the surviving women and children were removed and held hostage (and later killed in The Bibigarh massacre). Only four men eventually escaped alive from Cawnpore on one of the boats: two private soldiers (both of whom died later during the Rebellion), a lieutenant, and Captain Mowbray Thomson

, who wrote a first-hand account of his experiences entitled The Story of Cawnpore (London, 1859).

Whether the firing was planned or accidental remains unresolved. Most early histories assume it was planned either by the Nana Sahib (Kaye and Malleson) or that Tantia Tope and Brigadier Jwala Pershad planned it without the Nana Sahib's knowledge (G W Forrest). The stated reasons for the planned nature are: the speed with which the Nana Sahib agreed to the British conditions (Mowbray Thomson); and the firepower arranged around the ghat which was far in excess of what was necessary to guard the European troops (most histories agree on this). During his trial, Tatya Tope

denied the existence of any such plan and described the incident in the following terms: the Europeans had already boarded the boats and he (Tatya Tope) raised his right hand to signal their departure. That very moment someone from the crowd blew a loud bugle which created disorder and in the ongoing bewilderment, the boatmen jumped off the boats. The rebels started shooting indiscriminately. Nana Sahib, who was staying in Savada Kothi (Bungalow

) nearby, was informed about what was happening and immediately came to stop it. Some British histories allow that it might well have been the result of accident or error; someone accidentally or maliciously fired a shot, the panic-stricken British opened fire, and it became impossible to stop the massacre.

The surviving women and children were taken to the Nana Sahib and then confined first to the Savada Kothi and then to the home of the local magistrate's clerk (The Bibigarh) where they were joined by refugees from Fatehgarh. Overall five men and two hundred and six women and children were confined in The Bibigarh for about two weeks. In one week 25 were brought out dead, due to dysentery and cholera. Meanwhile a Company relief force that had advanced from Allahabad defeated the Indians and by 15 July it was clear that the Nana Sahib would not be able to hold Cawnpore and a decision was made by the Nana Sahib and other leading rebels that the hostages must be killed. After the sepoys refused to carry out this order, two Muslim butchers, two Hindu peasants and one of Nana's bodyguards went into The Bibigarh. Armed with knives and hatchets they murdered the women and children. After the massacre the walls were covered in bloody hand prints, and the floor littered with fragments of human limbs. The dead and the dying were thrown down a nearby well, when the well was full, the 50 feet (15.2 m) deep well was filled with remains to within 6 feet (1.8 m) of the top, the remainder were thrown into the Ganges.

Historians have given many reasons for this act of cruelty. With Company forces approaching Cawnpore and some believing that they would not advance if there were no hostages to save, their murders were ordered. Or perhaps it was to ensure that no information was leaked after the fall of Cawnpore. Other historians have suggested that the killings were an attempt to undermine Nana Sahib's relationship with the British. Perhaps it was due to fear, the fear of being recognized by some of the prisoners for having taken part in the earlier firings.

Image:1857_hospital_wheeler_cawnpore2.jpg|Photograph entitled, "The Hospital in General Wheeler's entrenchment, Cawnpore." (1858) The hospital was the site of the first major loss of European lives in Cawnpore (Kanpur)

Image:1857_sutter_ghat_cawnpore2.jpg|1858 picture of Sati Chaura Ghat on the banks of the Ganges River, where on 27 June 1857 many British men lost their lives and the surviving women and children were taken prisoner by the rebels.

File:1858 Kanpur well monument.jpg|Bibigurh house where European women and children were killed and the well where their bodies were found, 1858.

Image:1857_outside_well_cawnpore2.jpg|The Bibigurh Well site where a memorial had been built. Samuel Bourne

, 1860.

The killing of the women and children proved to be a mistake. The British public was aghast and the anti Imperial and pro-Indian proponents lost all their support. Cawnpore became a war cry for the British and their allies for the rest of the conflict. The Nana Sahib disappeared near the end of the Rebellion and it is not known what happened to him.

Other British accounts state that indiscriminate punitive measures were taken in early June, two weeks before the murders at the Bibi-Ghar (but after those at both Meerut and Delhi), specifically by Lieutenant Colonel James George Smith Neill

of the Madras Fusiliers (a European unit), commanding at Allahabad

while moving towards Cawnpore. At the nearby town of Fatehpur, a mob had attacked and murdered the local European population. On this pretext, Neill ordered all villages beside the Grand Trunk Road to be burned and their inhabitants to be hanged. Neill's methods were "ruthless and horrible" and far from intimidating the population, may well have induced previously undecided sepoys and communities to revolt.

Neill was killed in action at Lucknow on 26 September and was never called to account for his punitive measures, though contemporary British sources lionised him and his "gallant blue caps". By contrast with the actions of soldiers under Neill, the behaviour of most rebel soldiers was creditable. "Our creed does not permit us to kill a bound prisoner", one of the matchlockmen explained, "though we can slay our enemy in battle."

When the British retook Cawnpore, the soldiers took their sepoy prisoners to The Bibigarh and forced them to lick the bloodstains from the walls and floor. They then hanged or "blew from the cannon" (the traditional Mughal punishment for mutiny) the majority of the sepoy prisoners. Although some claimed the sepoys took no actual part in the killings themselves, they did not act to stop it and this was acknowledged by Captain Thompson after the British departed Cawnpore for a second time.

Very soon after the events in Meerut, rebellion erupted in the state of Awadh

Very soon after the events in Meerut, rebellion erupted in the state of Awadh

(also known as Oudh, in modern-day Uttar Pradesh

), which had been annexed barely a year before. The British Commissioner resident at Lucknow

, Sir Henry Lawrence

, had enough time to fortify his position inside the Residency compound. The Company forces numbered some 1700 men, including loyal sepoys. The rebels' assaults were unsuccessful, and so they began a barrage of artillery and musket fire into the compound. Lawrence was one of the first casualties. The rebels tried to breach the walls with explosives and bypass them via underground tunnels that led to underground close combat. After 90 days of siege, numbers of Company forces were reduced to 300 loyal sepoys, 350 British soldiers and 550 non-combatants.

On 25 September a relief column under the command of Sir Henry Havelock and accompanied by Sir James Outram

(who in theory was his superior) fought its way from Cawnpore to Lucknow in a brief campaign in which the numerically small column defeated rebel forces in a series of increasingly large battles. This became known as 'The First Relief of Lucknow', as this force was not strong enough to break the siege or extricate themselves, and so was forced to join the garrison. In October another, larger, army under the new Commander-in-Chief, Sir Colin Campbell

, was finally able to relieve the garrison and on 18 November, they evacuated the defended enclave within the city, the women and children leaving first. They then conducted an orderly withdrawal to Cawnpore, where they defeated an attempt by Tantya Tope to recapture the city in the Second Battle of Cawnpore

.

Early in 1858, Campbell once again advanced on Lucknow with a large army, this time seeking to suppress the rebellion in Awadh. He was aided by a large Nepal

ese contingent advancing from the north under Jang Bahadur

, who decided to side with the Company in December 1857. Campbell's advance was slow and methodical, and drove the large but disorganised rebel army from Lucknow with few casualties to his own troops. This nevertheless allowed large numbers of the rebels to disperse into Awadh, and Campbell was forced to spend the summer and autumn dealing with scattered pockets of resistance while losing men to heat, disease and guerrilla actions.

was a Maratha

-ruled princely state

in Bundelkhand

. When the Raja of Jhansi died without a biological male heir in 1853, it was annexed to the British Raj

by the Governor-General of India

under the doctrine of lapse

. His widow, Rani Lakshmi Bai, protested against the denial of rights of their adopted son.

When war broke out, Jhansi quickly became a centre of the rebellion. A small group of Company officials and their families took refuge in Jhansi

When war broke out, Jhansi quickly became a centre of the rebellion. A small group of Company officials and their families took refuge in Jhansi

's fort, and the Rani negotiated their evacuation. However, when they left the fort they were massacred by the rebels over whom the Rani had no control; the Europeans suspected the Rani of complicity, despite her repeated denials.

By the end of June 1857, the Company had lost control of much of Bundelkhand

and eastern Rajasthan

. The Bengal Army units in the area, having rebelled, marched to take part in the battles for Delhi and Cawnpore. The many princely states which made up this area began warring amongst themselves. In September and October 1857, the Rani led the successful defence of Jhansi against the invading armies of the neighbouring rajas of Datia

and Orchha

.

On 3 February Rose broke the 3-month siege of Saugor. Thousands of local villagers welcomed him as a liberator, freeing them from rebel occupation.

In March 1858, the Central India Field Force, led by Sir Hugh Rose

, advanced on and laid siege to Jhansi. The Company forces captured the city, but the Rani fled in disguise.

After being driven from Jhansi and Kalpi

, on 1 June 1858 Rani Lakshmi Bai and a group of Maratha rebels captured the fortress city of Gwalior from the Scindia rulers, who were British allies. This might have reinvigorated the rebellion but the Central India Field Force very quickly advanced against the city. The Rani died on 17 June, the second day of the Battle of Gwalior probably killed by a carbine shot from the 8th Hussars, according to the account of three independent Indian representatives. The Company forces recaptured Gwalior within the next three days. In descriptions of the scene of her last battle, she was compared to Joan Of Arc

by some commentators.

Indore

Colonel Henry Durand

, the then Company resident at Indore

had brushed away any possibility of uprising in Indore. However, on 1 July, sepoys in Holkar's army revolted and opened fire on the pickets of Bhopal Cavalry. When Colonel Travers rode forward to charge, Bhopal Cavalry refused to follow. The Bhopal Infantry also refused orders and instead leveled their guns at European sergeants and officers. Since all possibility of mounting an effective deterrent was lost, Durand decided to gather up all the European residents and escape, although 39 European residents of Indore were killed.

. It included not only the present-day Indian and Pakistani Punjabi regions but also the North West Frontier districts bordering Afghanistan.

Much of the region had been the Sikh Empire, ruled by Ranjit Singh

until his death in 1839. The kingdom had then fallen into disorder, with court factions and the Khalsa

(the Sikh army) contending for power at the Lahore Durbar (court). After two Anglo-Sikh Wars, the entire region was annexed by the East India Company in 1849. In 1857, the region still contained the highest numbers of both European and Indian troops.

The inhabitants of the Punjab were not as sympathetic to the sepoys as they were elsewhere in India, which limited many of the outbreaks in the Punjab to disjointed uprisings by regiments of sepoys isolated from each other. In some garrisons, notably Ferozepore, indecision on the part of the senior European officers allowed the sepoys to rebel, but the sepoys then left the area, mostly heading for Delhi. At the most important garrison, that of Peshawar

close to the Afghan frontier, many comparatively junior officers ignored their nominal commander (the elderly General Reed) and took decisive action. They intercepted the sepoys' mail, thus preventing their coordinating an uprising, and formed a force known as the "Punjab Movable Column" to move rapidly to suppress any revolts as they occurred. When it became clear from the intercepted correspondence that some of the sepoys at Peshawar were on the point of open revolt, the four most disaffected Bengal Native regiments were disarmed by the two British infantry regiments in the cantonment, backed by artillery, on 22 May. This decisive act induced many local chieftains to side with the British.

Jhelum in Punjab

Jhelum in Punjab

was also a centre of resistance against the British. Here 35 British soldiers of HM XXIV regiment (South Wales Borderers), died on 7 July 1857. To commemorate this victory St. John's Church Jhelum

was built and the names of those 35 British soldiers are carved on a marble lectern

present in that church.

The final large-scale military uprising in the Punjab took place on 9 July, when most of a brigade of sepoys at Sialkot

rebelled and began to move to Delhi. They were intercepted by John Nicholson

with an equal British force as they tried to cross the Ravi River

. After fighting steadily but unsuccessfully for several hours, the sepoys tried to fall back across the river but became trapped on an island. Three days later, Nicholson annihilated the 1,100 trapped sepoys in the Battle of Trimmu Ghat.

Some regiments in frontier garrisons subsequently rebelled, but became isolated among hostile Pakhtun villages and tribes. There were several mass executions, amounting to several hundred, of sepoys from units which rebelled or who deserted in the Punjab and North West Frontier provinces during June and July . The British had been recruiting irregular units from Sikh

and Pakhtun communities even before the first unrest among the Bengal units, and the numbers of these were greatly increased during the Rebellion, 34,000 fresh levies eventually being raised.

At one stage, faced with the need to send troops to reinforce the besiegers of Delhi, the Commissioner of the Punjab (Sir John Lawrence) suggested handing the coveted prize of Peshawar to Dost Mohammed Khan of Afghanistan in return for a pledge of friendship. The British Agents in Peshawar and the adjacent districts were horrified. Referring to the massacre of a retreating British army in 1840, Herbert Edwardes

wrote, "Dost Mahomed would not be a mortal Afghan ... if he did not assume our day to be gone in India and follow after us as an enemy. Europeans cannot retreat – Kabul would come again." In the event Lord Canning insisted on Peshawar being held, and Dost Mohammed, whose relations with Britain had been equivocal for over 20 years, remained neutral.

In September 1858 Rae Ahmed Nawaz Khan Kharal

, head of the Khurrul tribe, led an insurrection in the Neeli Bar

district, between the Sutlej, Ravi

and Chenab

rivers. The rebels held the jungles of Gogaira and had some initial successes against the British forces in the area, besieging Major Crawford Chamberlain at Chichawatni

. A squadron of Punjabi cavalry sent by Sir John Lawrence raised the siege. Ahmed Khan was killed but the insurgents found a new leader in Mir Bahawal Fatwanah, who maintained the uprising for three months until Government forces penetrated the jungle and scattered the rebel tribesmen.

; played a prominent part in the Rebellion. On hearing of the uprisings against British rule in the surrounding districts of Ghazipur, Azamgarh and Banaras, the Rajputs of Dobhi organised themselves into an armed force and attacked the Company all over the region. They also cut the Company communications along the Banaras-Azamgarh road and advanced towards the former Banaras State.

In the first encounter with the British regular troops, the Rajputs suffered heavy losses, but withdrew in order. Regrouping themselves, they made a bid to capture Banaras. In the meantime, Azamgarh had been besieged by another large force of rebels. The Company was unable to send reinforcement to Azamgarh due to the challenge posed by the Dobhi Rajputs. A clash became inevitable and the Company attacked the Rajputs with the help of the Sikhs and the Hindustani cavalry at the end of June 1857. The Rajputs were handicapped as the torrential monsoon rains soaked their supplies of gun-powder. The Rajputs, however, bitterly opposed the Company advance with swords and spears and the few serviceable guns and muskets that they had. The battle took place about 5 miles North of Banaras at a place called Pisnaharia-ka-Inar. The Rajputs were driven back with heavy losses across the Gomti river. The British army crossed the river and sacked every Rajput village in the area.

A few months later, Kunwar Singh of Jagdispur

(District Arrah

, Bihar), advanced and occupied Azamgarh

. The Banaras Army sent against him was defeated outside Azamgarh. The Company rushed reinforcements and there was a furious battle in which the Rajputs of Dobhi helped Kunwar Singh, their distant relative. Kunwar Singh had to withdraw and the Rajputs became the subject of cruel reprisals by the Company. The leaders of the Dobhi Rajputs were invited to a conference and treacherously arrested by the Company troops which had surrounded the place in Senapur village in May 1858. All were summarily executed by hanging from a mango tree, along with nine of their other followers. The dead bodies were further shot with muskets and left hanging from the trees. After few days, the bodies were taken down by the villagers and cremated.

, whose estate was in the process of being sequestrated by the Revenue Board, instigated and assumed the leadership of revolt in Bihar

.

On 25 July, rebellion erupted in the garrisons of Dinapur. The rebels quickly moved towards the cities of Arrah

and were joined by Kunwar Singh and his men. Mr. Boyle, a British railway engineer in Arrah, had already prepared his house for defense against such attacks-particular because he was a railway engineer. As the rebels approached Arrah, all European residents took refuge at Mr. Boyle's house. A siege soon ensued and 50 loyal sepoys defended the house against artillery and musketry fire from the rebels.

On 29 July 400 men were sent out from Dinapore to relieve Arrah, but this force was ambushed by the rebels around a mile away from the siege house, severely defeated, and driven back. On 30 July, Major Vincent Eyre, who was going up the river with his troops and guns, reached Buxar and heard about the siege. He immediately disembarked his guns and troops (the 5th Fusiliers) and started marching towards Arrah. On 2 August, some 16 miles (25.7 km) short of Arrah, the Major was ambushed by the rebels. After an intense fight, the 5th Fusiliers charged and stormed the rebel positions successfully. On 3 August, Major Eyre and his men reached the siege house and successfully ended the siege.

, and Trinidad

the annual Hosay processions were banned, riots broke out in penal settlements in Burma, and the Settlements, in Penang the loss of a musket provoked a near riot, and security was boosted especially in locations with an Indian convict population.

From the end of 1857, the British had begun to gain ground again. Lucknow was retaken in March 1858. On 8 July 1858, a peace treaty was signed and the rebellion ended. The last rebels were defeated in Gwalior on 20 June 1858. By 1859, rebel leaders Bakht Khan

From the end of 1857, the British had begun to gain ground again. Lucknow was retaken in March 1858. On 8 July 1858, a peace treaty was signed and the rebellion ended. The last rebels were defeated in Gwalior on 20 June 1858. By 1859, rebel leaders Bakht Khan

and Nana Sahib

had either been slain or had fled.

The rebels murder of women, children and wounded British soldiers at Cawnpore

, and the subsequent printing of the events in the British papers, left many British soldiers seeking revenge. As well as hanging mutineers, the British had some "blown from cannon

" (an old Mughal punishment adopted many years before in India). Sentenced rebels were tied over the mouths of cannons and blown to pieces when the gun was fired.

Most of the British press, outraged by the reports of rape and the killings of civilians and wounded British soldiers, did not advocate clemency of any kind. Governor General Canning

Most of the British press, outraged by the reports of rape and the killings of civilians and wounded British soldiers, did not advocate clemency of any kind. Governor General Canning

ordered moderation in dealing with native sensibilities and earned the scornful sobriquet "Clemency Canning" from the public.

In terms of sheer numbers, the casualties were much higher on the Indian side. A letter published after the fall of Delhi in the "Bombay Telegraph" and reproduced in the British press testified to the scale of the Indian casualties:

Edward Vibart, a 19-year-old officer, recorded his experience:

Some British troops adopted a policy of "no prisoners". One officer, Thomas Lowe, remembered how on one occasion his unit had taken 76 prisoners – they were just too tired to carry on killing and needed a rest, he recalled. Later, after a quick trial, the prisoners were lined up with a British soldier standing a couple of yards in front of them. On the order "fire", they were all simultaneously shot, "swept... from their earthly existence".

The aftermath of the rebellion has been the focus of new work using Indian sources and population studies. In The Last Mughal

The aftermath of the rebellion has been the focus of new work using Indian sources and population studies. In The Last Mughal

, historian William Dalrymple examines the effects on the Muslim population of Delhi after the city was retaken by the British and finds that intellectual and economic control of the city shifted from Muslim to Hindu hands because the British, at that time, saw an Islamic hand behind the mutiny.

The scale of the punishments handed out by the British "Army of Retribution" were considered largely appropriate and justified in a Britain shocked by reports of atrocities carried out on British and European civilians, and local Christians by the rebels Accounts of the time frequently reach the "hyperbolic register", according to Christopher Herbert, especially in the often-repeated claim that the "Red Year" of 1857 marked "a terrible break" in British experience. Such was the atmosphere – a national "mood of retribution and despair" that led to "almost universal approval" of the measures taken to pacify the revolt.

The scale of the punishments handed out by the British "Army of Retribution" were considered largely appropriate and justified in a Britain shocked by reports of atrocities carried out on British and European civilians, and local Christians by the rebels Accounts of the time frequently reach the "hyperbolic register", according to Christopher Herbert, especially in the often-repeated claim that the "Red Year" of 1857 marked "a terrible break" in British experience. Such was the atmosphere – a national "mood of retribution and despair" that led to "almost universal approval" of the measures taken to pacify the revolt.

The incidents of rape committed by Indian rebels against European women and girls appalled the British public. These atrocities were often used to justify the British reaction to the rebellion. British newspapers

printed various eyewitness accounts of the rape of English women and girls. One such account published by The Times

, regarding an incident where 48 English girls as young as 10 had been raped by Indian rebels in Delhi

. Karl Marx

later claimed that this was propaganda stating that the account was written by a clergyman in Bangalore

, far from the events of the rebellion, though he produced no evidence to support this. Individual incidents captured the public's interest and were heavily reported by the press. One such incident was that of General Wheeler's daughter Margaret being forced to live as her captor's concubine, though this was reported to the Victorian public as Margaret killing her rapist then herself. Another version of the story suggested that Margaret had been killed after her abductor had argued with his wife over her.

The poet Martin Tupper – "in a ferment of indignation" – played a major part in shaping the public's response. His poems, filled with calls for the razing of Delhi and the erection of "groves of gibbets" are telling:

Punch

, normally cynical and dispassionate where other periodicals were jingoistic, in August published a two-page cartoon depicting the British Lion attacking a Bengal Tiger that had attacked an English woman and child; the cartoon received considerable attention at the time, with the New York Times writing a piece about it in September as emblematic of a near-universal British desire for revenge. It was re-issued as a print, and made the career of John Tenniel

, later famous as the illustrator of Alice in Wonderland.

According to Victorianist Patrick Brantlinger, no event raised national hysteria in Britain to a higher pitch, and no event in the 19th century took a greater hold on the British imagination, so much so that "Victorian writing about the Mutiny expresses in concentrated form the racist ideology that Edward Said

According to Victorianist Patrick Brantlinger, no event raised national hysteria in Britain to a higher pitch, and no event in the 19th century took a greater hold on the British imagination, so much so that "Victorian writing about the Mutiny expresses in concentrated form the racist ideology that Edward Said

calls Orientalism

". Others note that this was just one of a number of colonial rebellions which had a cumulative effect on British public opinion

The term 'Sepoy' or 'Sepoyism' became a derogatory term for nationalists especially in Ireland.

Bahadur Shah was tried for treason by a military commission assembled at Delhi, and exiled to Rangoon where he died in 1862, bringing the Mughal dynasty to an end. In 1877 Queen Victoria took the title of Empress of India on the advice of Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli

Bahadur Shah was tried for treason by a military commission assembled at Delhi, and exiled to Rangoon where he died in 1862, bringing the Mughal dynasty to an end. In 1877 Queen Victoria took the title of Empress of India on the advice of Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli

.

The rebellion saw the end of the British East India Company

's rule in India. In August, by the Government of India Act 1858

, the company was formally dissolved and its ruling powers over India were transferred to the British Crown. A new British government department, the India Office

, was created to handle the governance of India, and its head, the Secretary of State for India

, was entrusted with formulating Indian policy. The Governor-General of India gained a new title (Viceroy of India), and implemented the policies devised by the India Office. The British colonial administration embarked on a program of reform, trying to integrate Indian higher castes and rulers into the government and abolishing attempts at Westernization

. The Viceroy stopped land grabs, decreed religious tolerance and admitted Indians into civil service, albeit mainly as subordinates.

Essentially the old East India Company bureaucracy remained, though there was a major shift in attitudes. In looking for the causes of the Mutiny the authorities alighted on two things: religion and the economy. On religion it was felt that there had been too much interference with indigenous traditions, both Hindu and Muslim. On the economy it was now believed that the previous attempts by the Company to introduce free market competition had undermined traditional power structures and bonds of loyalty placing the peasantry at the mercy of merchants and money-lenders. In consequence the new British Raj

was constructed in part around a conservative agenda, based on a preservation of tradition and hierarchy.

On a political level it was also felt that the previous lack of consultation between rulers and ruled had been yet another significant factor in contributing to the uprising. In consequence, Indians were drawn into government at a local level. Though this was on a limited scale a crucial precedent had been set, with the creation of a new 'white collar' Indian elite, further stimulated by the opening of universities at Calcutta, Bombay and Madras, a result of the Indian Universities Act. So, alongside the values of traditional and ancient India, a new professional middle class was starting to arise, in no way bound by the values of the past. Their ambition can only have been stimulated by Victoria's Proclamation of November 1858, in which it is expressly stated that "We hold ourselves bound to the natives of our Indian territories by the same obligations of duty which bind us to our other subjects...it is our further will that... our subjects of whatever race or creed, be freely and impartially admitted to offices in our service, the duties of which they may be qualified by their education, ability and integrity, duly to discharge."

Acting on these sentiments, Lord Ripon

, viceroy from 1880 to 1885, extended the powers of local self-government and sought to remove racial practices in the law courts by the Ilbert Bill

. But a policy at once liberal and progressive at one turn was reactionary and backward at the next, creating new elites and confirming old attitudes. The Ilbert Bill only had the effect of causing a White mutiny

, and the end of the prospect of perfect equality before the law. In 1886 measures were adopted to restrict Indian entry into the civil service.

The rebellion transformed both the "native" and European armies of British India. Of the 74 regular Bengal Native Infantry regiments in existence at the beginning of 1857 only twelve escaped mutiny or disbandment. All ten of the Bengal Light Cavalry regiments were lost. The old Bengal Army had accordingly almost completely vanished from the order of battle. These troops were replaced by new units recruited from castes hitherto under-utilised by the British and from the minority so-called "Martial Races", such as the Sikh

s and the Gurkha

s.

The inefficiencies of the old organisation, which had estranged sepoys from their British officers, were addressed, and the post-1857 units were mainly organised on the "irregular" system. Before the rebellion each Bengal Native Infantry regiment had 26 British officers, who held every position of authority down to the second-in-command of each company. In irregular units there were few European officers who associated themselves far more closely with their soldiers, while more responsibility was given to the Indian officers.

The British increased the ratio of British to Indian soldiers within India. From 1861 Indian artillery was replaced by British units, except for a few mountain batteries. The post-rebellion changes formed the basis of the military organisation of British India until the early 20th century.

In India and Pakistan it has been termed as the "War of Independence of 1857" or "First War of Indian Independence" but it is not uncommon to use terms such as the "Revolt of 1857". The concept of the Rebellion being "First War of Independence" is not without its critics in India.

The use of the term "Indian Mutiny" is considered by some Indian politicians as belittling what they see as a "First War of Independence" and therefore reflecting a imperialistic attitude. Others dispute this interpretation.

In the UK and parts of the Commonwealth

it is commonly called the "Indian Mutiny", but terms such as "Great Indian Mutiny", the "Sepoy Mutiny", the "Sepoy Rebellion", the "Sepoy War", the "Great Mutiny", the "Rebellion of 1857", "the Uprising", the "Mahomedan Rebellion",and the "Revolt of 1857" have also been used. "The Indian Insurrection" was a name used in the press of the UK and British colonies at the time.

Almost from the moment the first sepoys mutinied in Meerut, the nature and the scope of the Indian Rebellion of 1857 has been contested and argued over. Speaking in the House of Commons

in July 1857, Benjamin Disraeli labeled it a 'national revolt' while Lord Palmerston, the Prime Minister, tried to downplay the scope and the significance of the event as a 'mere military mutiny'. Reflecting this debate, the early historian of the rebellion, Charles Ball, sided with the mutiny in his title (using mutiny and sepoy insurrection) but labeled it a 'struggle for liberty and independence as a people' in the text. Historians remain divided on whether the rebellion can properly be considered a war of Indian independence or not, although it is popularly considered to be one in India. Arguments against include:

A second school of thought while acknowledging the validity of the above-mentioned arguments opines that this rebellion may indeed be called a war of India's independence. The reasons advanced are: