Indian independence movement

Encyclopedia

The term Indian independence movement encompasses a wide area of political organisations, philosophies, and movements which had the common aim of ending first British East India Company

rule, and then British imperial authority

, in parts of South Asia

. The independence movement saw various national and regional campaigns, agitations and efforts of both nonviolent

and militant

philosophy.

During the first quarter of the 19th century, Raja Rammohan Roy introduced modern education into India. Swami Vivekananda

was the chief architect who profoundly projected the rich culture of India to the west at the end of 19th century. Many of the country's political leaders of the 19th and 20th century, including Mahatma Gandhi

and Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, were influenced by the teachings of Swami Vivekananda

.

The first organized militant movements were in Bengal

, but they later took to the political stage in the form of a mainstream movement in the then newly formed Indian National Congress

(INC), with prominent moderate leaders seeking only their basic right to appear for civil service examinations, as well as more rights, economic in nature, for the people of the soil. The early part of the 20th century saw a more radical approach towards political independence proposed by leaders such as the Lal Bal Pal

and Sri Aurobindo

. Militant nationalism also emerged in the first decades, culminating in the failed Indo-German Pact and the Ghadar Conspiracy during the First World War

.

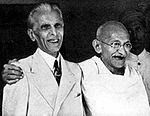

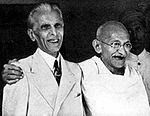

The last stages of the freedom struggle from the 1920s onwards saw Congress adopt Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi's policy of nonviolence and civil resistance, Muhammad Ali Jinnah

's constitutional struggle for the rights of minorities in India, and several other campaigns. Legendary figures, such as Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose, later came to adopt a military approach to the movement, and others like Swami Sahajanand Saraswati

wanted both political and economic freedom

for India's peasant

s and toiling masses. Poets like Rabindranath Tagore

used literature, poetry and speech as a tool for political awareness. The period of the Second World War

saw the peak of movements such as the Quit India movement

(led by Mahatma Gandhi) and the Indian National Army

(INA) movement (led by Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose) and that eventually result freedom for India.

These various movements led ultimately to the Indian Independence Act 1947

, which created the independent dominion

s of India

and Pakistan

. India remained a Dominion of the Crown

until 26 January 1950, when the Constitution of India

came into force, establishing the Republic of India.

The Indian independence movement was a mass-based movement that encompassed various sections of society at the time. It also underwent a process of constant ideological evolution. Although the basic ideology of the movement was anti-colonial, it was supported by a vision of independent capitalist economic development coupled with a secular, democratic, republican, and civil-libertarian political structure. After the 1930s, the movement took on a strong socialist orientation, due to the increasing influence of left-wing elements in the INC as well as the rise and growth of the Communist Party of India

. On the other hand, due to INC's policies, Muslim League was formed to protect the rights of Muslims in Indian Sub-continent against INC and to present its voice to the British government.

explorer Vasco da Gama

in 1498 at the port of Calicut

, in search of the lucrative spice

trade. Just over a century later, the Dutch and English established trading outposts on the subcontinent, with the first English trading post set up at Surat

in 1612. Over the course of the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, the British defeated militarily the Portuguese and Dutch, but remained in conflict with the French, who had by then sought to establish themselves in the subcontinent. The decline of the Mughal empire

in the first half of the eighteenth century provided the British with a firm foothold in Indian politics. After the Battle of Plassey

in 1757, during which a British East India Company

army under Robert Clive defeated Siraj-ud-Daula (the Nawab of Bengal

), the Company established itself as a major player in Indian affairs, and soon after gained administrative rights over the regions of Bengal

, Bihar

, and Orissa

following the Battle of Buxar

in 1765. After the defeat of Tipu Sultan

, most of South India was now either under the Company's direct rule, or under its indirect political control as part of one of the princely state

s. The Company subsequently gained control of regions ruled by the Maratha Empire

, after defeating them in a series of wars. Punjab

was annexed in 1849 after the defeat of the Sikh armies in the First

(1845–46) and Second

(1848–49) Anglo-Sikh Wars.

In 1835 English

In 1835 English

was made the medium of instruction in India's schools. Western-educated Hindu elites sought to rid Hinduism

of controversial social practices, including the varna

(caste) system, child marriage, and sati

. Literary and debating societies initiated in Calcutta

(Kolkata) and Bombay

(Mumbai) became forums for open political discourse.

Even while these modernising trends influenced Indian society, Indians increasingly despised British rule. With the British now dominating most of the subcontinent, they grew increasingly abusive of local customs by, for example, staging parties in mosque

s, dancing to the music of regimental bands on the terrace of the Taj Mahal

, using whips to force their way through crowded bazaar

s (as recounted by General Henry Blake), and mistreating Indians (including the sepoy

s). In the years after the annexation of Punjab

in 1849, several mutinies broke out among the sepoys; these were put down by force.

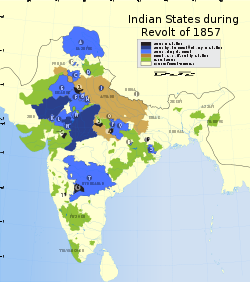

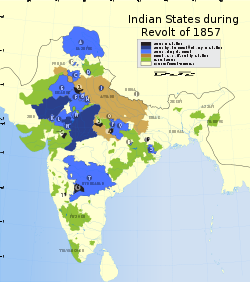

The Indian rebellion of 1857 was a period of uprising

The Indian rebellion of 1857 was a period of uprising

in northern and central India

against the British East India Company

's rule. The conditions of service in the Company's army and cantonment

s increasingly came into conflict with the religious beliefs and prejudices of the sepoy

s. The predominance of members from the upper castes in the army, perceived loss of caste due to overseas travel, and rumours of secret designs of the Government to convert them to Christianity

led to deep discontentment among the sepoys. The sepoys were also disillusioned by their low salaries and the racial discrimination practised by British officers in matters of promotion and privileges. The indifference of the British towards leading native Indian rulers such as the Mughals and ex-Peshwa

s and the annexation of Oudh were political factors triggering dissent amongst Indians. The Marquess of Dalhousie

's policy of annexation, the doctrine of lapse

(or escheat) applied by the British, and the projected removal of the descendants of the Great Mughal from their ancestral palace at Red Fort

to the Qutb (near Delhi

) also angered some people.

The final spark was provided by the rumoured use of cow

and pig fat

in the newly introduced Pattern 1853 Enfield

rifle cartridges. Soldiers had to bite the cartridge

s with their teeth before loading them into their rifles, and the reported presence of cow and pig fat was offensive to both Hindu and Muslim soldiers. On 10 May 1857, the sepoys at Meerut broke rank and turned on their commanding officers, killing some of them. They then reached Delhi on May 11, set the Company's toll house afire, and marched into the Red Fort, where they asked the Mughal emperor

, Bahadur Shah II

, to become their leader and reclaim his throne. The emperor was reluctant at first, but eventually agreed and was proclaimed Shehenshah-e-Hindustan by the rebels. The rebels also murdered much of the European, Eurasian

, and Christian population of the city. David, S (202) The India Mutiny, Penguin P122

Revolts broke out in other parts of Oudh and the North-Western Provinces

as well, where civil rebellion followed the mutinies, leading to popular uprisings. The British were initially caught off-guard and were thus slow to react, but eventually responded with force. The lack of effective organisation among the rebels, coupled with the military superiority of the British, brought a rapid end to the rebellion. The British fought the main army of the rebels near Delhi, and after prolonged fighting and a siege, defeated them and retook the city on 20 September 1857. Subsequently, revolts in other centres were also crushed. The last significant battle was fought in Gwalior on 17 June 1858, during which Rani Lakshmi Bai was killed. Sporadic fighting and guerrilla warfare

, led by Tantia Tope, continued until 1859, but most of the rebels were eventually subdued.

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major turning point in the history of modern India. While affirming the military and political power of the British, it led to significant change in how India was to be controlled by them. Under the Government of India Act 1858

, the Company was deprived of its involvement in ruling India, with its territory being transferred to the direct authority of the British government. At the apex of the new system was a Cabinet minister, the Secretary of State for India

, who was to be formally advised by a statutory council

; the Governor-General of India

(Viceroy) was made responsible to him, while he in turn was responsible to the British Parliament

for British rule. In a royal proclamation made to the people of India, Queen Victoria

promised equal opportunity of public service under British law, and also pledged to respect the rights of the native princes. The British stopped the policy of seizing land from the princes, decreed religious tolerance, and began to admit Indians into the civil service (albeit mainly as subordinates). However, they also increased the number of British soldiers in relation to native Indian ones, and only allowed British soldiers to handle artillery. Bahadur Shah

was exiled to Rangoon

(Yangon), Burma (Myanmar), where he died in 1862.

In 1876, Queen Victoria

took the additional title of Empress of India.

formed the East India Association in 1867, and Surendranath Banerjee founded the Indian National Association

in 1876.

Inspired by a suggestion made by A. Hume

, a retired British civil servant, seventy-three Indian delegates met in Bombay

in 1885 and founded the Indian National Congress

. They were mostly members of the upwardly mobile and successful western-educated provincial elites, engaged in professions such as law, teaching, and journalism. At its inception, the Congress had no well-defined ideology and commanded few of the resources essential to a political organization. Instead, it functioned more as a debating society that met annually to express its loyalty to the British Raj, and passed numerous resolutions on less controversial issues such as civil rights or opportunities in government (especially in the civil service). These resolutions were submitted to the Viceroy's government and occasionally to the British Parliament, but the Congress's early gains were meagre. Despite its claim to represent all India, the Congress voiced the interests of urban elites; the number of participants from other social and economic backgrounds remained negligible.

The influence of socio-religious groups such as Arya Samaj

(started by Swami Dayanand Saraswati) and Brahmo Samaj

(founded by Raja Ram Mohan Roy and others) became evident in pioneering reforms of Indian society. The work of men like Swami Vivekananda

, Ramakrishna Paramhansa, Sri Aurobindo

, Subramanya Bharathy

, Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, Sir Syed Ahmed Khan

, Rabindranath Tagore

, and Dadabhai Naoroji

, as well as women such as the Scots–Irish Sister Nivedita

, spread the passion for rejuvenation and freedom. The rediscovery of India's indigenous history by several European and Indian scholars also fed into the rise of nationalism among Indians.

s, who felt that their representation in government service was inadequate. Attacks by Hindu reformers against religious conversion, cow slaughter, and the preservation of Urdu in Arabic

script deepened their concerns of minority status and denial of rights if the Congress alone were to represent the people of India. Sir Syed Ahmed Khan

launched a movement for Muslim regeneration that culminated in the founding in 1875 of the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College at Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh (renamed Aligarh Muslim University in 1920). Its objective was to educate wealthy students by emphasizing the compatibility of Islam

with modern western knowledge. The diversity among India's Muslims, however, made it impossible to bring about uniform cultural and intellectual regeneration.

The nationalistic sentiments among Congress members led to the movement to be represented in the bodies of government, to have a say in the legislation and administration of India. Congressmen saw themselves as loyalists, but wanted an active role in governing their own country, albeit as part of the Empire. This trend was personified by Dadabhai Naoroji

, who went as far as contesting, successfully, an election to the British House of Commons

, becoming its first Indian member.

Bal Gangadhar Tilak

was the first Indian nationalist to embrace Swaraj

as the destiny of the nation. Tilak deeply opposed the then British education system that ignored and defamed India's culture, history and values. He resented the denial of freedom of expression for nationalists, and the lack of any voice or role for ordinary Indians in the affairs of their nation. For these reasons, he considered Swaraj

as the natural and only solution. His popular sentence "Swaraj is my birthright, and I shall have it" became the source of inspiration for Indians.

In 1907, the Congress was split into two factions. The radicals led by Tilak advocated civil agitation and direct revolution to overthrow the British Empire and the abandonment of all things British. The moderates led by leaders like Dadabhai Naoroji and Gopal Krishna Gokhale

on the other hand wanted reform within the framework of British rule. Tilak was backed by rising public leaders like Bipin Chandra Pal

and Lala Lajpat Rai

, who held the same point of view. Under them, India's three great states - Maharashtra

, Bengal

and Punjab

shaped the demand of the people and India's nationalism. Gokhale criticized Tilak for encouraging acts of violence and disorder. But the Congress of 1906 did not have public membership, and thus Tilak and his supporters were forced to leave the party.

But with Tilak's arrest, all hopes for an Indian offensive were stalled. The Congress lost credit with the people. A Muslim deputation met with the Viceroy, Minto

(1905–10), seeking concessions from the impending constitutional reforms, including special considerations in government service and electorates. The British recognized some of the Muslim League's petitions by increasing the number of elective offices reserved for Muslims in the Indian Councils Act 1909. The Muslim League insisted on its separateness from the Hindu-dominated Congress, as the voice of a "nation within a nation."

supposedly for improvements in administrative efficiency in the huge and populous region. It also had justifications due to increasing conflicts between Muslims and dominant Hindu regimes in Bengal. However the Indians viewed the partition as an attempt by the British to disrupt the growing national movement in Bengal and divide the Hindus and Muslims of the region. The Bengali Hindu intelligentsia exerted considerable influence on local and national politics. The partition outraged Bengalis. Not only had the government failed to consult Indian public opinion, but the action appeared to reflect the British resolve to divide and rule

. Widespread agitation ensued in the streets and in the press, and the Congress advocated boycotting British products under the banner of swadeshi. Hindus showed unity by tying Rakhi on each other's wrists and observing Arandhan (not cooking any food). During this time Bengali Hindu nationalists begin writing virulent newspaper articles and were charged with sedition. Brahmabhandav Upadhyay, a Hindu newspaper editor who helped Tagore establish his school at Shantiniketan, was imprisoned and the first martyr to die in British custody in the 20th century struggle for independence.

at Dhaka

(now Bangladesh

), in 1906, in the context of the circumstances that were generated over the partition of Bengal in 1905. Being a political party to secure the interests of the Muslim diaspora in British India

, the Muslim League played a decisive role during the 1940s in the Indian independence movement and developed into the driving force behind the creation of Pakistan

in the Indian subcontinent

.

In 1906, Muhammad Ali Jinnah

joined the Indian National Congress

, which was the largest Indian political organization. Like most of the Congress at the time, Jinnah did not favour outright independence, considering British influences on education, law, culture and industry as beneficial to India. Jinnah became a member on the sixty-member Imperial Legislative Council

. The council had no real power or authority, and included a large number of un-elected pro-Raj loyalists and Europeans. Nevertheless, Jinnah was instrumental in the passing of the Child Marriages Restraint Act, the legitimization of the Muslim waqf

(religious endowments) and was appointed to the Sandhurst committee, which helped establish the Indian Military Academy

at Dehra Dun. During World War I

, Jinnah joined other Indian moderates in supporting the British war effort, hoping that Indians would be rewarded with political freedoms.

began with an unprecedented outpouring of loyalty and goodwill towards the United Kingdom from within the mainstream political leadership, contrary to initial British fears of an Indian revolt. India contributed massively to the British war effort by providing men and resources. About 1.3 million Indian soldiers and labourers served in Europe

, Africa

, and the Middle East

, while both the Indian government and the princes sent large supplies of food, money, and ammunition. However, Bengal

and Punjab

remained hotbeds of anti colonial activities

. Nationalism in Bengal, increasingly closely linked with the unrests in Punjab, was significant enough to nearly paralyse the regional administration. Also from the beginning of the war, expatriate Indian population, notably from United States, Canada, and Germany, headed by the Berlin Committee

and the Ghadar Party

, attempted to trigger insurrections in India on the lines of the 1857 uprising with Irish Republican, German and Turkish help in a massive conspiracy that has since come to be called the Hindu–German Conspiracy

This conspiracy also attempted to rally Afghanistan against British India. A number of failed attempts were made at mutiny, of which the February mutiny plan and the Singapore mutiny

remains most notable. This movement was suppressed by means of a massive international counter-intelligence operation and draconian political acts (including the Defence of India act 1915

) that lasted nearly ten years.

In the aftermath of the World War I

, high casualty rates, soaring inflation compounded by heavy taxation, a widespread influenza

epidemic, and the disruption of trade during the war escalated human suffering in India. The Indian soldiers smuggled arms into India to overthrow the British rule. The pre-war nationalist movement revived as moderate and extremist groups within the Congress submerged their differences in order to stand as a unified front. In 1916, the Congress succeeded in forging the Lucknow Pact

, a temporary alliance with the Muslim League over the issues of devolution of political power and the future of Islam in the region.

The British themselves adopted a "carrot and stick" approach in recognition of India's support during the war and in response to renewed nationalist demands. In August 1917, Edwin Montagu

, the secretary of state for India, made the historic announcement in Parliament that the British policy for India was "increasing association of Indians in every branch of the administration and the gradual development of self-governing institutions with a view to the progressive realization of responsible government in India as an integral part of the British Empire." The means of achieving the proposed measure were later enshrined in the Government of India Act 1919

, which introduced the principle of a dual mode of administration, or diarchy, in which both elected Indian legislators and appointed British officials shared power. The act also expanded the central and provincial legislatures and widened the franchise considerably. Diarchy set in motion certain real changes at the provincial level: a number of non-controversial or "transferred" portfolios, such as agriculture

, local government, health

, education

, and public works, were handed over to Indians, while more sensitive matters such as finance

, taxation, and maintaining law and order were retained by the provincial British administrators.

), had been a prominent leader of the anti-Apartheid movement in South Africa

, and had been a vocal opponent of basic discrimination and abusive labour treatment as well as suppressive police control such as the Rowlatt Acts. During these protests, Gandhi had perfected the concept of satyagraha

, which had been inspired by the philosophy of Baba Ram Singh

(famous for leading the Kuka

Movement in the Punjab

in 1872). The end of the protests in South Africa saw oppressive legislation repealed and the release of political prisoners by General Jan Smuts

, head of the South African Government of the time.

Gandhi returned to India, on 6 January 1915 and initially entered the political fray not with calls for a nation-state, but in support of the unified commerce-oriented territory that the Congress Party had been asking for. Gandhi believed that the industrial development and educational development that the Europeans had brought with them were required to alleviate many of India's problems. Gopal Krishna Gokhale

, a veteran Congressman and Indian leader, became Gandhi's mentor. Gandhi's ideas and strategies of non-violent civil disobedience

initially appeared impractical to some Indians and Congressmen. In Gandhi's own words, "civil disobedience is civil breach of unmoral statutory enactments." It had to be carried out non-violently by withdrawing cooperation with the corrupt state. Gandhi's ability to inspire millions of common people became clear when he used satyagraha

during the anti-Rowlatt Act protests in Punjab. Gandhi had great respect to Lokmanya Tilak. His programmes were all inspired by Tilak's "Chatusutri" programme.

Gandhi’s vision would soon bring millions of regular Indians into the movement, transforming it from an elitist struggle to a national one. The nationalist cause was expanded to include the interests and industries that formed the economy of common Indians. For example, in Champaran, Bihar

, the Congress Party championed the plight of desperately poor sharecroppers and landless farmers who were being forced to pay oppressive taxes and grow cash crops at the expense of the subsistence crops which formed their food supply. The profits from the crops they grew were insufficient to provide for their sustenance.

The positive impact of reform was seriously undermined in 1919 by the Rowlatt Act

, named after the recommendations made the previous year to the Imperial Legislative Council

by the Rowlatt Commission, which had been appointed to investigate what was termed the "seditious conspiracy" and the German and Bolshevik

involvement in the militant movements in India. The Rowlatt Act, also known as the Black Act, vested the Viceroy's government with extraordinary powers to quell sedition by silencing the press, detaining the political activists without trial, and arresting any individuals suspected of sedition or treason without a warrant. In protest, a nationwide cessation of work (hartal

) was called, marking the beginning of widespread, although not nationwide, popular discontent.

The agitation unleashed by the acts culminated on 13 April 1919, in the Jallianwala Bagh massacre

(also known as the Amritsar Massacre) in Amritsar

, Punjab. The British military commander, Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer

, blocked the main entrance-cum-exit, and ordered his soldiers to fire into an unarmed and unsuspecting crowd of some 5,000 men, women and children. They had assembled at Jallianwala Bagh, a walled courtyard in defiance of the ban. A total of 1,651 rounds were fired, killing 379 people (as according to an official British commission; Indian estimates ranged as high as 1,499) and wounding 1,137 in the episode, which dispelled wartime hopes of home rule and goodwill in a frenzy of post-war reaction.

and Indian material as alternatives to those shipped from Britain

. It also urged people to boycott British educational institutions and law courts; resign from government employment; refuse to pay taxes; and forsake British titles and honours. Although this came too late to influence the framing of the new Government of India Act 1919

, the movement enjoyed widespread popular support, and the resulting unparalleled magnitude of disorder presented a serious challenge to foreign rule. However, Gandhi called off the movement following the Chauri Chaura

incident, which saw the death of twenty-two policemen at the hands of an angry mob.

Membership in the party was opened to anyone prepared to pay a token fee, and a hierarchy of committees was established and made responsible for discipline and control over a hitherto amorphous and diffuse movement. The party was transformed from an elite organization to one of mass national appeal and participation.

Gandhi was sentenced in 1922 to six years of prison, but was released after serving two. On his release from prison, he set up the Sabarmati Ashram

in Ahmedabad

, on the banks of river Sabarmati

, established the newspaper Young India, and inaugurated a series of reforms aimed at the socially disadvantaged within Hindu society — the rural poor, and the untouchables.

This era saw the emergence of new generation of Indians from within the Congress Party, including C. Rajagopalachari

, Jawaharlal Nehru

, Vallabhbhai Patel, Subhash Chandra Bose

and others- who would later on come to form the prominent voices of the Indian independence movement, whether keeping with Gandhian Values, or diverging from it

.

The Indian political spectrum was further broadened in the mid-1920s by the emergence of both moderate and militant parties, such as the Swaraj Party

, Hindu Mahasabha, Communist Party of India

and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh

. Regional political organizations also continued to represent the interests of non-Brahmin

s in Madras, Mahar

s in Maharashtra

, and Sikh

s in Punjab. However, people like Mahakavi Subramanya Bharathi, Vanchinathan

and Neelakanda Brahmachari played a major role from Tamil Nadu in both freedom struggle and fighting for equality for all castes and communities.

by Indians, an all-party conference was held at Bombay in May 1928. This was meant to instill a sense of resistance among people. The conference appointed a drafting committee under Motilal Nehru

to draw up a constitution for India. The Calcutta session of the Indian National Congress asked the British government to accord dominion status to India by December 1929, or a countrywide civil disobedience movement would be launched. By 1929, however, in the midst of rising political discontent and increasingly violent regional movements, the call for complete independence from Britain began to find increasing grounds within the Congress leadership. Under the presidency of Jawaharlal Nehru

at its historic Lahore

session in December 1929, The Indian National Congress adopted a resolution calling for complete independence from the British. It authorised the Working Committee to launch a civil disobedience movement throughout the country. It was decided that 26 January 1930 should be observed all over India as the Purna Swaraj

(total independence) Day. Many Indian political parties and Indian revolutionaries of a wide spectrum united to observe the day with honour and pride.

Karachi congress session-1931

A special session was held to endorse the Gandhi-Irwin or Delhi Pact.

The goal of Purna swaraj was reiterated.

Two resolutions were adopted-one on Fundamental rights and other on National Economic programme. which made the session perticularly memmorable.

This was the first time the congress spelt out what swaraj would mean for the masses.

to Dandi

, on the coast of Gujarat between 11 March and 6 April 1930. The march is usually known as the Dandi March or the Salt Satyagraha. At Dandi, in protest against British taxes on salt, he and thousands of followers broke the law by making their own salt from seawater. It took 24 days for him to complete this march. Every day he covered 10 miles and gave many speeches.

In April 1930 there were violent police-crowd clashes in Calcutta. Approximately 100,000 people were imprisoned in the course of the Civil disobedience movement (1930–31), while in Peshawar

unarmed demonstrators were fired upon in the Qissa Khwani bazaar massacre

. The latter event catapulted the then newly formed Khudai Khidmatgar

movement (founder Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan

, the Frontier Gandhi) onto the National scene. While Gandhi was in jail, the first Round Table Conference was held in London in November 1930, without representation from the Indian National Congress. The ban upon the Congress was removed because of economic hardships caused by the satyagraha. Gandhi, along with other members of the Congress Working Committee, was released from prison in January 1931.

In March 1931, the Gandhi-Irwin Pact

was signed, and the government agreed to set all political prisoners free (Although, some of the key revolutionaries were not set free and the death sentence for Bhagat Singh and his two comrades was not taken back which further intensified the agitation against Congress not only outside it but with in the Congress itself). In return, Gandhi agreed to discontinue the civil disobedience movement and participate as the sole representative of the Congress in the second Round Table Conference, which was held in London in September 1931. However, the conference ended in failure in December 1931. Gandhi returned to India and decided to resume the civil disobedience movement in January 1932.

For the next few years, the Congress and the government were locked in conflict and negotiations until what became the Government of India Act 1935

could be hammered out. By then, the rift between the Congress and the Muslim League had become unbridgeable as each pointed the finger at the other acrimoniously. The Muslim League disputed the claim of the Congress to represent all people of India, while the Congress disputed the Muslim League's claim to voice the aspirations of all Muslims.

The Government of India Act 1935

The Government of India Act 1935

, the voluminous and final constitutional effort at governing British India, articulated three major goals: establishing a loose federal structure, achieving provincial autonomy, and safeguarding minority interests through separate electorates. The federal provisions, intended to unite princely state

s and British India at the centre, were not implemented because of ambiguities in safeguarding the existing privileges of princes. In February 1937, however, provincial autonomy became a reality when elections were held; the Congress emerged as the dominant party with a clear majority in five provinces and held an upper hand in two, while the Muslim League performed poorly.

In 1939, the Viceroy Linlithgow declared India's entrance into World War II

without consulting provincial governments. In protest, the Congress asked all of its elected representatives to resign from the government. Jinnah, the president of the Muslim League, persuaded participants at the annual Muslim League session at Lahore

in 1940 to adopt what later came to be known as the Lahore Resolution

, demanding the division of India into two separate sovereign states, one Muslim

, the other Hindu

; sometimes referred to as Two Nation Theory. Although the idea of Pakistan

had been introduced as early as 1930, very few had responded to it. However, the volatile political climate and hostilities between the Hindus and Muslims transformed the idea of Pakistan into a stronger demand.

Apart from a few stray incidents, the armed rebellion against the British rulers was not organized before the beginning of the 20th century. The Indian revolutionary underground began gathering momentum through the first decade of 1900s, with groups arising in Bengal

, Maharastra, Orissa

, Bihar

, Uttar Pradesh

, Punjab

, and the then Madras Presidency

including what is now called South India

. More groups were scattered around India

. Particularly notable movements arose in Bengal

, especially around the Partition of Bengal

in 1905, and in Punjab

. In the former case, it was the educated, intelligent and

dedicated youth of the urban Middle Class

Bhadralok

community that came to form the "Classic" Indian revolutionary, while the latter had an immense support base in the rural and Military society of the Punjab. Organisations like Jugantar

and Anushilan Samiti

had emerged in the 1900s. The revolutionary philosophies and movement made their presence felt during the 1905 Partition of Bengal. Arguably, the initial steps to organize the revolutionaries were taken by Aurobindo Ghosh, his brother Barin Ghosh, Bhupendranath Datta etc. when they formed the Jugantar

party in April 1906. Jugantar

was created as an inner circle of the Anushilan Samiti

which was already present in Bengal

mainly as a revolutionary society in the guise of a fitness club.

The Anushilan Samiti and Jugantar opened several branches throughout Bengal

and other parts of India

and recruited young men and women to participate in the revolutionary activities. Several murders and looting were done, with many revolutionaries being captured and imprisoned. The Jugantar

party leaders like Barin Ghosh and Bagha Jatin

initiated making of explosives. Amongst a number of notable events of political terrorism were the Alipore bomb case

, the Muzaffarpur killing tried several activists and many were sentenced to deportation for life, while Khudiram Bose

was hanged. The founding of the India House

and The Indian Sociologist

under Shyamji Krishna Varma

in London

in 1905 took the radical movement to Britain itself. On 1 July 1909, Madan Lal Dhingra

, an Indian student closely identified with India House in London shot dead William Hutt Curzon Wylie, a British M.P. in London

. 1912 saw the Delhi-Lahore Conspiracy planned under Rash Behari Bose

, an erstwhile Jugantar

member, to assassinate the then Viceroy of India Charles Hardinge. The conspiracy culminated in an attempt to Bomb the Viceregal procession on 23 December 1912, on the occasion of transferring the Imperial Capital from Calcutta to Delhi

. In the aftermath of this event, concentrated police and intelligence efforts were made by the British Indian police to destroy the Bengali and Punabi revolutionary underground, which came under intense pressure for sometime. Rash Behari successfully evaded capture for nearly three years. However, by the time that World War I

opened in Europe, the revolutionary movement in Bengal (and Punjab) had revived and was strong enough to nearly paralyse the local administration. in 1914, Indian revolutionaries made conspiracies against British rule but the plan was failed and many revolutionaries sacrificed their life and others were arrested and sent to the Cellular Jail (Kalapani) in Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

During the First World War, the revolutionaries planned to import arms and ammunitions from Germany

and stage an armed revolution against the British.

The Ghadar Party

operated from abroad and cooperated with the revolutionaries in India. This party was instrumental in helping revolutionaries inside India catch hold of foreign arms.

After the First World War, the revolutionary activities began to slowly wane as it suffered major setbacks due to the arrest of prominent leaders. In the 1920s, some revolutionary activists began to reorganize.

and Ashfaqullah Khan who belonged to the Hindustan Republican Association (HRA, which became HSRA or Hindustan Socialist Republican Association in 1928) that was created to carry out revolutionary

activities against the British Empire in India

. The objective of the HRA was to conduct an armed revolution against the British government. The organization needed money for the supply of weapon

ry, and thus Bismil decided to loot a train on one of the Northern Railway lines. The robbery plan was executed by Ram Prasad Bismil

, Ashfaqulla Khan

, Rajendra Lahiri

, Chandrasekhar Azad

, Sachindra Bakshi

, Keshab Chakravarthy

(fake name of K.B. Hedgewar), Manmathnath Gupta, Murari Sharma

(fake name of Murari Lal Gupta), Mukundi Lal (Mukundi Lal Gupta),. In this historical event 40 persons belonging to HRA were arrested and a Conspiracy case was filed in which 4 were sentenced to death and 16 others were given imprisonment varying from 2 years to life importation.

Hindustan Socialist Republican Association

was formed under the leadership of Chandrasekhar Azad

. Bhagat Singh and Batukeshwar Dutt

threw a bomb inside the Central Legislative Assembly

on 8 April 1929 protesting against the passage of the Public Safety Bill and the Trade Disputes Bill. Following the trial (Central Assembly Bomb Case), Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev

and Rajguru were hanged in 1931. Allama Mashriqi founded Khaksar Tehreek

in order to direct particularly the Muslims towards the independence movement.

Surya Sen

, along with other activists, raided the Chittagong

armoury on 18 April 1930 to capture arms and ammunition and to destroy government communication system to establish a local governance. Pritilata Waddedar

led an attack on a European club in Chittagong

in 1932, while Bina Das

attempted to assassinate Stanley Jackson

, the Governor of Bengal

inside the convocation hall of Calcutta University. Following the Chittagong armoury raid

case, Surya Sen

was hanged and several others were deported for life to the Cellular Jail

in Andaman

. The Bengal Volunteers

started operating in 1928. On 8 December 1930, the Benoy

-Badal

-Dinesh

trio of the party entered the secretariat Writers' Building

in Kolkata

and murdered Col. N. S. Simpson, the Inspector General of Prisons.

On 13 March 1940, Udham Singh

shot Michael O'Dwyer

, generally held responsible for the Amritsar Massacre, in London. However, as the political scenario changed in the late 1930s — with the mainstream leaders considering several options offered by the British and with religious politics coming into play — revolutionary activities gradually declined. Many past revolutionaries joined mainstream politics by joining Congress

and other parties, especially communist ones, while many of the activists were kept under hold in different jails across the country.

, as Linlithgow

, without consulting the Indian representatives had unilaterally declared India a belligerent on the side of the allies

. In opposition to Linlithgow's action, the entire Congress leadership resigned from the local government councils. However, many wanted to support the British war effort, and indeed the British Indian Army

was one of the largest volunteer forces, numbering 205,000 men during the war. Especially during the Battle of Britain

, Gandhi resisted calls for massive civil disobedience movements that came from within as well as outside his party, stating he did not seek India's freedom out of the ashes of a destroyed Britain. However, like the changing fortunes of the war itself, the movement for freedom saw the rise of three movements that formed the climax of the 100-year struggle for independence.

The first of these, the Kakori conspiracy (9 August 1925) was done by the Indian youth under the leadership of Pandit Ram Prasad Bismil, second was the Azad Hind movement led by Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose, saw its inception early in the war and sought help from the Axis Powers. And the third one after 17 years of the first from the same date (9) saw its inception in August

1942 which was led by Lal Bahadur Shastri

and the common man resulting the failure of the Cripps' mission

to reach a consensus with the Indian political leadership over the transfer of power after the war.

movement in India

launched on 9 August 1942 in response to Gandhi's call for immediate independence of India and against sending Indians to World War II. He asked all the teachers to leave their school, and other Indians to leave away their respective jobs and take part in this movement. Due to Gandhi's political influence, request was followed on a massive proportion of the population.

At the outbreak of war, the Congress Party had during the Wardha meeting of the working-committee in September 1939, passed a resolution conditionally supporting the fight against fascism, but were rebuffed when they asked for independence in return. In March 1942, faced with an increasingly dissatisfied sub-continent only reluctantly participating in the war, and deteriorations in the war situation in Europe

and South East Asia, and with growing dissatisfactions among Indian troops- especially in Europe- and among the civilian population in the sub-continent, the British government sent a delegation to India under Stafford Cripps

, in what came to be known as the Cripps' Mission

. The purpose of the mission was to negotiate with the Indian National Congress

a deal to obtain total co-operation during the war, in return of progressive devolution and distribution of power from the crown and the Viceroy

to elected Indian legislature. However, the talks failed, having failed to address the key demand of a timeframe towards self-government, and of definition of the powers to be relinquished, essentially portraying an offer of limited dominion-status that was wholly unacceptable to the Indian movement. To force the Raj to meet its demands and to obtain definitive word on total independence, the Congress took the decision to launch the Quit India Movement.

The aim of the movement was to bring the British Government

to the negotiating table by holding the Allied War Effort hostage. The call for determined but passive resistance that signified the certitude that Gandhi foresaw for the movement is best described by his call to Do or Die, issued on 8 August at the Gowalia Tank Maidan

in Bombay, since re-named August Kranti Maidan (August Revolution Ground). However, almost the entire Congress leadership, and not merely at the national level, was put into confinement less than twenty-four hours after Gandhi's speech, and the greater number of the Congress khiland were to spend the rest of the war in jail.

On 8 August 1942, the Quit India resolution was passed at the Bombay session of the All India Congress Committee (AICC). The draft proposed that if the British did not accede to the demands, a massive Civil Disobedience would be launched. However, it was an extremely controversial decision. At Gowalia Tank, Mumbai

, Gandhi urged Indians to follow a non-violent civil disobedience. Gandhi told the masses to act as an independent nation and not to follow the orders of the British. The British, already alarmed by the advance of the Japanese army to the India–Burma border, responded the next day by imprisoning Gandhi at the Aga Khan Palace

in Pune

. The Congress Party's Working Committee, or national leadership was arrested all together and imprisoned at the Ahmednagar Fort. They also banned the party altogether. Large-scale protests and demonstrations were held all over the country. Workers remained absent en masse and strikes were called. The movement also saw widespread acts of sabotage

, Indian under-ground organisation carried out bomb attacks on allied supply convoys, government buildings were set on fire, electricity lines were disconnected and transport and communication lines were severed. The Congress had lesser success in rallying other political forces, including the Muslim League under a single mast and movement. It did however, obtain passive support from a substantial Muslim population at the peak of the movement.The movement soon became a leaderless act of defiance, with a number of acts that deviated from Gandhi's principle of non-violence. In large parts of the country, the local underground organisations took over the movement. However, by 1943, Quit India had petered out.

. In 1940, a year after war broke out, the British had put Bose under house arrest in Calcutta. However, he escaped and made his way through Afghanistan

to Germany to seek Axis help to raise an army to fight the British. Here, he raised with Rommel

's Indian POWs what came to be known as the Free India Legion. Bose made his way ultimately to Japanese South Asia, where he formed what came to be known as the Azad Hind Government, a Provisional Free Indian Government in exile, and organized the Indian National Army

with Indian POWs and Indian expatriates in South-East Asia, with the help of the Japan

ese. Its aim was to reach India as a fighting force that would build on public resentment to inspire revolts among Indian soldiers to defeat the British raj.

The INA was to see action against the allies, including the British Indian Army, in the forests of Arakan, Burma and in Assam

The INA was to see action against the allies, including the British Indian Army, in the forests of Arakan, Burma and in Assam

, laying siege on Imphal and Kohima

with the Japanese 15th Army. During the war, the Andaman and Nicobar islands were captured by the Japanese

and handed over by them to the INA. Bose renamed them Shahid (Martyr) and Swaraj (Independence).

The INA would ultimately fail, owing to disrupted logistics, poor arms and supplies from the Japanese, and lack of support and training. http://mondediplo.com/2005/05/13wwiiasia The supposed death

of Bose is seen as culmination of the entire Azad Hind Movement. Following the surrender of Japan, the troops of the INA were brought to India and a number of them charged with treason. However, Bose's actions had captured the public imagination and also turned the inclination of the native soldiers of the British Indian Forces from one of loyalty to the crown to support for the soldiers that the Raj deemed as collaborators.

After the war, the stories of the Azad Hind movement and its army that came into public limelight during the trials of soldiers of the INA in 1945 were seen as so inflammatory that, fearing mass revolts and uprisings — not just in India, but across its empire — the British Government forbade the BBC

from broadcasting their story. Newspapers reported the summary execution of INA soldiers held at Red Fort. During and after the trial, mutinies broke out in the British Indian Armed forces, most notably in the Royal Indian Navy

which found public support throughout India

, from Karachi

to Mumbai

and from Vizag to Kolkata

. Many historians have argued that the INA, and the mutinies it inspired, were strong driving forces behind the transfer of power in 1947.

in late February and early March 1942 relations between the British officers and their Indian troops broke down. On the night of 10 March the Indian troops led by a Sikh policemen mutinied killing the five British soldiers and the imprisoning of the remaining 21 Europeans on the island. Later on 31 March, a Japanese fleet arrived at the island and the Indians surrendered.

. This movement marked the last major campaign in which the forces of the Congress and the Muslim League aligned together; the Congress tricolor and the green flag of the League were flown together at protests. In spite of this aggressive and widespread opposition, the court martial was carried out, and all three defendants were sentenced to deportation for life. This sentence, however, was never carried out, as the immense public pressure of the demonstrations forced Claude Auchinleck, Commander-in-Chief of the Indian Army, to release all three defendants.

During the trial, mutiny broke out in the Royal Indian Navy

, incorporating ships and shore establishments of the RIN throughout India, from Karachi to Bombay and from Vizag to Calcutta. The most significant, if disconcerting factor for the British, was the significant militant public support that the mutiny received. At some places, NCOs in the Indian Army started ignoring orders from their British officers. In Madras and Pune, the British garrisons had to face revolts within the ranks of the Army.

Another Army mutiny took place at Jabalpur during the last week of February 1946, soon after the Navy mutiny at Bombay. This was suppressed by force, including the use of the bayonet by British troops. It lasted about two weeks. After the mutiny, about 45 persons were tried by court martial. 41 were sentenced to varying terms of imprisonment or dismissal. In addition, a large number were discharged on administrative grounds. While the participants of the Naval Mutiny were given the freedom fighters' pension, the Jabalpur mutineers got nothing. They even lost their service pension.

Reflecting on the factors that guided the British decision to quit India, Clement Attlee, the then British prime minister, cited several reasons, the most important of which were the INA activities of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, which weakened the Indian Army - the foundation of the British Empire in India- and the RIN Mutiny that made the British realise that the Indian armed forces could no longer be trusted to prop up their rule. Although at the time of the Cripps mission in 1942 Britain had made a commitment to grant dominion status to India after the war, this suggests that, contrary to the usual narrative of India's independence struggle, which generally focuses on Congress and Mahatma Gandhi, the INA and the revolts, mutinies, and public resentment it germinated were an important factor in the complete withdrawal of the British from India.

Most of the INA. soldiers were set free after cashiering and forfeiture of pay and allowance. On the recommendation of Lord Mountbatten of Burma, and agreed by Nehru, as a precondition for Independence the INA soldiers were not reinducted into the Indian Army.

Whether as a measure of the pain that the allies suffered in Imphal and Burma or as an act of vengeance, Mountbatten, Head of Southeast Asia Command, ordered the INA Memorial to its fallen soldiers destroyed when the Singapore was recaptured in 1945. It has been suggested later that Mountbatten's actions may have been to erase completely the records of INA's existence, to prevent the seeds of the idea of a revolutionary socialist liberation force from spreading into the vestiges of its colonies amidst the spectre of cold-war politics already taking shape at the time, and had haunted the Colonial powers before the war. In 1995, the National Heritage Board of Singapore marked the place as a historical site. A Cenotaph has since been erected at the site where the memorial stood.

After the war ended, the story of the INA and the Free India Legion was seen as so inflammatory that, fearing mass revolts and uprisings—not just in India, but across its empire—the British Government forbid the BBC from broadcasting their story. However, the stories of the trials at the Red Fort filtered through. Newspapers reported at the time of the trials that some of the INA soldiers held at Red Fort had been executed, which only succeeded in causing further protests.

by the Indian sailors of the Royal Indian Navy

on board ship and shore establishments at Mumbai

(Bombay) harbour on 18 February 1946. From the initial flashpoint in Mumbai

, the mutiny

spread and found support through India

, from Karachi

to Calcutta and ultimately came to involve 78 ships, 20 shore establishments and 20,000 sailors.

The RIN Mutiny started as a strike by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy on the 18th February in protest against general conditions. The immediate issues of the mutiny were conditions and food, but there were more fundamental matters such as racist behaviour by British officers of the Royal Navy

personnel towards Indian sailors, and disciplinary measures being taken against anyone demonstrating pro-nationalist sympathies. By dusk on 19 February, a Naval Central Strike committee was elected. Leading Signalman M.S Khan and Petty Officer Telegraphist Madan Singh were unanimously elected President and Vice-President respectively. The strike found immense support among the Indian population already in grips with the stories of the Indian National Army

. The actions of the mutineers were supported by demonstrations which included a one-day general strike in Mumbai

, called by the Bolshevik-Leninist Party of India, Ceylon and Burma

. The strike spread to other cities, and was joined by the Air Force

and local police forces

. Naval officers and men began calling themselves the Indian National Navy and offered left-handed salutes to British officers. At some places, NCOs in the British Indian Army

ignored and defied orders from British superiors. In Chennai

and Pune

, the British garrisons had to face revolts within the ranks of the British Indian Army

. Widespread rioting took place from Karachi

to Calcutta. Famously the ships hoisted three flags tied together — those of the Congress

, Muslim League, and the Red Flag of the Communist Party of India

(CPI), signifying the unity and demarginalisation of communal issues among the mutineers.

The true judgment of contributions of each of these individual events and revolts to India’s eventual independence, and the relative success or failure of each, remains open to historians. Some historians claim that the Quit India Movement was ultimately a failure and ascribe more to the destabilisation of the pillar of British power in India the British Indian Armed forces. Certainly the British Prime Minister

at the time of Independence, Clement Attlee

, deemed the contribution of Quit India as minimal, ascribing stupendous importance to the revolts and growing dissatisfaction among Royal Indian Armed Forces as the driving force behind the Raj’s decision to leave India

Some Indian historians, however, argue that, in fact, it was Quit India that succeeded. In support of the latter view, without doubt, the war had sapped a lot of the economic, political and military life-blood of the Empire, and the powerful Indian resistance had shattered the spirit and will of the British government. However, such historians effectively ignore the contributions of the radical

movements to transfer of power in 1947. Regardless of whether it was the powerful common call for resistance among Indians that shattered the spirit and will of the British Raj

to continue ruling India, or whether it was the ferment of rebellion and resentment among the British Indian Armed Forces what is beyond doubt, is that a population of millions had been motivated as it never had been before to say ultimately that independence was a non-negotiable goal, and every act of defiance and rebel only stoked this fire. In addition, the British people and the British Army seemed unwilling to back a policy of repression in India and other parts of the Empire even as their own country was recovering from war.

, announced the partitioning of British India into India

and Pakistan

. With the speedy passage through the British Parliament of the Indian Independence Act 1947

, at 11:57 on 14 August 1947 Pakistan was declared a separate nation, and at 12:02, just after midnight, on 15 August 1947

, India also became an independent nation. Violent clashes between Hindu

s, Sikh

s and Muslim

s followed. Prime Minister Nehru and Deputy Prime Minister Sardar

Vallabhbhai Patel invited Mountbatten to continue as Governor General of India. He was replaced in June 1948 by Chakravarti Rajagopalachari. Patel took on the responsibility of bringing into the Indian Union 565 princely states, steering efforts by his “iron fist in a velvet glove” policies, exemplified by the use of military force to integrate Junagadh

and Hyderabad state

(Operation Polo

) into India. On the other hand Pandit Jawahar Lal Nehru kept the issue of Kashmir

in his hands. The problem of Kashmir has become a permanent cancer in the geographical head of independent India

.

The Constituent Assembly completed the work of drafting the constitution on 26 November 1949; on 26 January 1950 the Republic of India was officially proclaimed. The Constituent Assembly elected Dr. Rajendra Prasad

as the first President of India

, taking over from Governor General Rajgopalachari. Subsequently India annexed Goa

and Portugal's other Indian enclaves

in 1961), the French ceded Chandernagore in 1951, and Pondicherry and its remaining Indian colonies in 1956, and Sikkim

voted to join the Indian Union in 1975.

East India Company

The East India Company was an early English joint-stock company that was formed initially for pursuing trade with the East Indies, but that ended up trading mainly with the Indian subcontinent and China...

rule, and then British imperial authority

British Raj

British Raj was the British rule in the Indian subcontinent between 1858 and 1947; The term can also refer to the period of dominion...

, in parts of South Asia

South Asia

South Asia, also known as Southern Asia, is the southern region of the Asian continent, which comprises the sub-Himalayan countries and, for some authorities , also includes the adjoining countries to the west and the east...

. The independence movement saw various national and regional campaigns, agitations and efforts of both nonviolent

Nonviolence

Nonviolence has two meanings. It can refer, first, to a general philosophy of abstention from violence because of moral or religious principle It can refer to the behaviour of people using nonviolent action Nonviolence has two (closely related) meanings. (1) It can refer, first, to a general...

and militant

Revolutionary movement for Indian independence

The Revolutionary movement for Indian independence is often a less-highlighted aspect of the Indian independence movement -- the underground revolutionary factions. The groups believing in armed revolution against the ruling British fall into this category. The revolutionary groups were...

philosophy.

During the first quarter of the 19th century, Raja Rammohan Roy introduced modern education into India. Swami Vivekananda

Swami Vivekananda

Swami Vivekananda , born Narendranath Dutta , was the chief disciple of the 19th century mystic Ramakrishna Paramahansa and the founder of the Ramakrishna Math and the Ramakrishna Mission...

was the chief architect who profoundly projected the rich culture of India to the west at the end of 19th century. Many of the country's political leaders of the 19th and 20th century, including Mahatma Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi , pronounced . 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948) was the pre-eminent political and ideological leader of India during the Indian independence movement...

and Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, were influenced by the teachings of Swami Vivekananda

Swami Vivekananda

Swami Vivekananda , born Narendranath Dutta , was the chief disciple of the 19th century mystic Ramakrishna Paramahansa and the founder of the Ramakrishna Math and the Ramakrishna Mission...

.

The first organized militant movements were in Bengal

Bengal

Bengal is a historical and geographical region in the northeast region of the Indian Subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal. Today, it is mainly divided between the sovereign land of People's Republic of Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal, although some regions of the previous...

, but they later took to the political stage in the form of a mainstream movement in the then newly formed Indian National Congress

Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress is one of the two major political parties in India, the other being the Bharatiya Janata Party. It is the largest and one of the oldest democratic political parties in the world. The party's modern liberal platform is largely considered center-left in the Indian...

(INC), with prominent moderate leaders seeking only their basic right to appear for civil service examinations, as well as more rights, economic in nature, for the people of the soil. The early part of the 20th century saw a more radical approach towards political independence proposed by leaders such as the Lal Bal Pal

Lal Bal Pal

Lal Bal Pal were the Swadeshit triumvirate who advocated the Swadeshi movement involving the boycott of all imported items and the use of Indian-made goods in 1907....

and Sri Aurobindo

Sri Aurobindo

Sri Aurobindo , born Aurobindo Ghosh or Ghose , was an Indian nationalist, freedom fighter, philosopher, yogi, guru, and poet. He joined the Indian movement for freedom from British rule and for a duration became one of its most important leaders, before developing his own vision of human progress...

. Militant nationalism also emerged in the first decades, culminating in the failed Indo-German Pact and the Ghadar Conspiracy during the First World War

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

.

The last stages of the freedom struggle from the 1920s onwards saw Congress adopt Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi's policy of nonviolence and civil resistance, Muhammad Ali Jinnah

Muhammad Ali Jinnah

Muhammad Ali Jinnah was a Muslim lawyer, politician, statesman and the founder of Pakistan. He is popularly and officially known in Pakistan as Quaid-e-Azam and Baba-e-Qaum ....

's constitutional struggle for the rights of minorities in India, and several other campaigns. Legendary figures, such as Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose, later came to adopt a military approach to the movement, and others like Swami Sahajanand Saraswati

Swami Sahajanand Saraswati

Swami Sahajanand Saraswati , born in a Jijhoutia Brahminfamily of Ghazipur of Uttar Pradesh state of India, was an ascetic of Dashnami Order of Adi Shankara Sampradaya as well as a nationalist and peasant leader of India...

wanted both political and economic freedom

Economic freedom

Economic freedom is a term used in economic and policy debates. As with freedom generally, there are various definitions, but no universally accepted concept of economic freedom...

for India's peasant

Peasant

A peasant is an agricultural worker who generally tend to be poor and homeless-Etymology:The word is derived from 15th century French païsant meaning one from the pays, or countryside, ultimately from the Latin pagus, or outlying administrative district.- Position in society :Peasants typically...

s and toiling masses. Poets like Rabindranath Tagore

Rabindranath Tagore

Rabindranath Tagore , sobriquet Gurudev, was a Bengali polymath who reshaped his region's literature and music. Author of Gitanjali and its "profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful verse", he became the first non-European Nobel laureate by earning the 1913 Prize in Literature...

used literature, poetry and speech as a tool for political awareness. The period of the Second World War

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

saw the peak of movements such as the Quit India movement

Quit India Movement

The Quit India Movement , or the August Movement was a civil disobedience movement launched in India in August 1942 in response to Mohandas Gandhi's call for immediate independence. Gandhi hoped to bring the British government to the negotiating table...

(led by Mahatma Gandhi) and the Indian National Army

Indian National Army

The Indian National Army or Azad Hind Fauj was an armed force formed by Indian nationalists in 1942 in Southeast Asia during World War II. The aim of the army was to overthrow the British Raj in colonial India, with Japanese assistance...

(INA) movement (led by Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose) and that eventually result freedom for India.

These various movements led ultimately to the Indian Independence Act 1947

Indian Independence Act 1947

The Indian Independence Act 1947 was as an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that partitioned British India into the two new independent dominions of India and Pakistan...

, which created the independent dominion

Dominion

A dominion, often Dominion, refers to one of a group of autonomous polities that were nominally under British sovereignty, constituting the British Empire and British Commonwealth, beginning in the latter part of the 19th century. They have included Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland,...

s of India

Dominion of India

The Dominion of India, also known as the Union of India or the Indian Union , was a predecessor to modern-day India and an independent state that existed between 15 August 1947 and 26 January 1950...

and Pakistan

Dominion of Pakistan

The Dominion of Pakistan was an independent federal Commonwealth realm in South Asia that was established in 1947 on the partition of British India into two sovereign dominions . The Dominion of Pakistan, which included modern-day Pakistan and Bangladesh, was intended to be a homeland for the...

. India remained a Dominion of the Crown

The Crown

The Crown is a corporation sole that in the Commonwealth realms and any provincial or state sub-divisions thereof represents the legal embodiment of governance, whether executive, legislative, or judicial...

until 26 January 1950, when the Constitution of India

Constitution of India

The Constitution of India is the supreme law of India. It lays down the framework defining fundamental political principles, establishes the structure, procedures, powers, and duties of government institutions, and sets out fundamental rights, directive principles, and the duties of citizens...

came into force, establishing the Republic of India.

The Indian independence movement was a mass-based movement that encompassed various sections of society at the time. It also underwent a process of constant ideological evolution. Although the basic ideology of the movement was anti-colonial, it was supported by a vision of independent capitalist economic development coupled with a secular, democratic, republican, and civil-libertarian political structure. After the 1930s, the movement took on a strong socialist orientation, due to the increasing influence of left-wing elements in the INC as well as the rise and growth of the Communist Party of India

Communist Party of India

The Communist Party of India is a national political party in India. In the Indian communist movement, there are different views on exactly when the Indian communist party was founded. The date maintained as the foundation day by CPI is 26 December 1925...

. On the other hand, due to INC's policies, Muslim League was formed to protect the rights of Muslims in Indian Sub-continent against INC and to present its voice to the British government.

Early British colonialism in India

European traders first reached Indian shores with the arrival of the PortuguesePortugal

Portugal , officially the Portuguese Republic is a country situated in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula. Portugal is the westernmost country of Europe, and is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the West and South and by Spain to the North and East. The Atlantic archipelagos of the...

explorer Vasco da Gama

Vasco da Gama

Vasco da Gama, 1st Count of Vidigueira was a Portuguese explorer, one of the most successful in the Age of Discovery and the commander of the first ships to sail directly from Europe to India...

in 1498 at the port of Calicut

History of Kozhikode

Kozhikode , also known as Calicut, is a city in the southern Indian state of Kerala. It is the third largest city in Kerala and the headquarters of Kozhikode district....

, in search of the lucrative spice

Spice

A spice is a dried seed, fruit, root, bark, or vegetative substance used in nutritionally insignificant quantities as a food additive for flavor, color, or as a preservative that kills harmful bacteria or prevents their growth. It may be used to flavour a dish or to hide other flavours...

trade. Just over a century later, the Dutch and English established trading outposts on the subcontinent, with the first English trading post set up at Surat

Surat

Surat , also known as Suryapur, is the commercial capital city of the Indian state of Gujarat. Surat is India's Eighth most populous city and Ninth-most populous urban agglomeration. It is also administrative capital of Surat district and one of the fastest growing cities in India. The city proper...

in 1612. Over the course of the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, the British defeated militarily the Portuguese and Dutch, but remained in conflict with the French, who had by then sought to establish themselves in the subcontinent. The decline of the Mughal empire

Mughal Empire

The Mughal Empire , or Mogul Empire in traditional English usage, was an imperial power from the Indian Subcontinent. The Mughal emperors were descendants of the Timurids...

in the first half of the eighteenth century provided the British with a firm foothold in Indian politics. After the Battle of Plassey

Battle of Plassey

The Battle of Plassey , 23 June 1757, was a decisive British East India Company victory over the Nawab of Bengal and his French allies, establishing Company rule in South Asia which expanded over much of the Indies for the next hundred years...

in 1757, during which a British East India Company

East India Company

The East India Company was an early English joint-stock company that was formed initially for pursuing trade with the East Indies, but that ended up trading mainly with the Indian subcontinent and China...

army under Robert Clive defeated Siraj-ud-Daula (the Nawab of Bengal

Nawab of Bengal

The Nawabs of Bengal were the hereditary nazims or subadars of the subah of Bengal during the Mughal rule and the de-facto rulers of the province.-History:...

), the Company established itself as a major player in Indian affairs, and soon after gained administrative rights over the regions of Bengal

Bengal

Bengal is a historical and geographical region in the northeast region of the Indian Subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal. Today, it is mainly divided between the sovereign land of People's Republic of Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal, although some regions of the previous...

, Bihar

Bihar

Bihar is a state in eastern India. It is the 12th largest state in terms of geographical size at and 3rd largest by population. Almost 58% of Biharis are below the age of 25, which is the highest proportion in India....

, and Orissa

Orissa

Orissa , officially Odisha since Nov 2011, is a state of India, located on the east coast of India, by the Bay of Bengal. It is the modern name of the ancient nation of Kalinga, which was invaded by the Maurya Emperor Ashoka in 261 BC. The modern state of Orissa was established on 1 April...

following the Battle of Buxar

Battle of Buxar

The Battle of Buxar was fought on 22 October 1764 between the forces under the command of the British East India Company, and the combined armies of Mir Qasim, the Nawab of Bengal; Shuja-ud-Daula Nawab of Awadh; and Shah Alam II, the Mughal Emperor...

in 1765. After the defeat of Tipu Sultan

Tipu Sultan

Tipu Sultan , also known as the Tiger of Mysore, was the de facto ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore. He was the son of Hyder Ali, at that time an officer in the Mysorean army, and his second wife, Fatima or Fakhr-un-Nissa...

, most of South India was now either under the Company's direct rule, or under its indirect political control as part of one of the princely state

Princely state

A Princely State was a nominally sovereign entitity of British rule in India that was not directly governed by the British, but rather by an Indian ruler under a form of indirect rule such as suzerainty or paramountcy.-British relationship with the Princely States:India under the British Raj ...

s. The Company subsequently gained control of regions ruled by the Maratha Empire

Maratha Empire

The Maratha Empire or the Maratha Confederacy was an Indian imperial power that existed from 1674 to 1818. At its peak, the empire covered much of South Asia, encompassing a territory of over 2.8 million km²....

, after defeating them in a series of wars. Punjab

Punjab region

The Punjab , also spelled Panjab |water]]s"), is a geographical region straddling the border between Pakistan and India which includes Punjab province in Pakistan and the states of the Punjab, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Chandigarh and some northern parts of the National Capital Territory of Delhi...

was annexed in 1849 after the defeat of the Sikh armies in the First

First Anglo-Sikh War

The First Anglo-Sikh War was fought between the Sikh Empire and the British East India Company between 1845 and 1846. It resulted in partial subjugation of the Sikh kingdom.-Background and causes of the war:...

(1845–46) and Second

Second Anglo-Sikh War

The Second Anglo-Sikh War took place in 1848 and 1849, between the Sikh Empire and the British East India Company. It resulted in the subjugation of the Sikh Empire, and the annexation of the Punjab and what subsequently became the North-West Frontier Province by the East India Company.-Background...

(1848–49) Anglo-Sikh Wars.

English language

English is a West Germanic language that arose in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England and spread into what was to become south-east Scotland under the influence of the Anglian medieval kingdom of Northumbria...

was made the medium of instruction in India's schools. Western-educated Hindu elites sought to rid Hinduism

Hinduism

Hinduism is the predominant and indigenous religious tradition of the Indian Subcontinent. Hinduism is known to its followers as , amongst many other expressions...

of controversial social practices, including the varna

Varnas

Varnas is the masculine form of a Lithuanian family name. Its feminine forms are: Varnienė and Varnytė .The surname may refer to:* Adomas Varnas , Lithuanian artist...

(caste) system, child marriage, and sati

Sati (practice)

For other uses, see Sati .Satī was a religious funeral practice among some Indian communities in which a recently widowed woman either voluntarily or by use of force and coercion would have immolated herself on her husband’s funeral pyre...

. Literary and debating societies initiated in Calcutta

Kolkata

Kolkata , formerly known as Calcutta, is the capital of the Indian state of West Bengal. Located on the east bank of the Hooghly River, it was the commercial capital of East India...

(Kolkata) and Bombay

Mumbai

Mumbai , formerly known as Bombay in English, is the capital of the Indian state of Maharashtra. It is the most populous city in India, and the fourth most populous city in the world, with a total metropolitan area population of approximately 20.5 million...

(Mumbai) became forums for open political discourse.

Even while these modernising trends influenced Indian society, Indians increasingly despised British rule. With the British now dominating most of the subcontinent, they grew increasingly abusive of local customs by, for example, staging parties in mosque

Mosque

A mosque is a place of worship for followers of Islam. The word is likely to have entered the English language through French , from Portuguese , from Spanish , and from Berber , ultimately originating in — . The Arabic word masjid literally means a place of prostration...