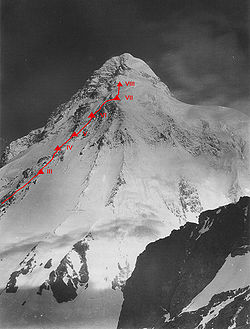

Third American Karakoram Expedition

Encyclopedia

Mountaineering

Mountaineering or mountain climbing is the sport, hobby or profession of hiking, skiing, and climbing mountains. While mountaineering began as attempts to reach the highest point of unclimbed mountains it has branched into specialisations that address different aspects of the mountain and consists...

expedition to K2

K2

K2 is the second-highest mountain on Earth, after Mount Everest...

, at 8,611 metres the second highest mountain on Earth

Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun, and the densest and fifth-largest of the eight planets in the Solar System. It is also the largest of the Solar System's four terrestrial planets...

. It was the fifth expedition to attempt K2, and the first since the Second World War. Led by Charles Houston

Charles Snead Houston

-References:-External links:* - Daily Telegraph obituary* Independent obituary, 1 October 2009.-Notes:...

, a mainly American

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

team attempted the mountain's South-East Spur

Spur (mountain)

A spur is a subsidiary summit of a hill or mountain. By definition, spurs have low topographic prominence, as they are lower than their parent summit and are closely connected to them on the same ridgeline...

(commonly known as the Abruzzi Spur) in a style which was unusually lightweight for the time. The team reached a high point of 7750 m, but were trapped by a storm in their high camp, where a team member, Art Gilkey

Art Gilkey

Art Gilkey was an American geologist and mountaineer. He explored Alaska in 1950 and 1952. He died during a 1953 American expedition to K2. Approaching the summit of the peak, he suffered from thrombophlebitis or possibly deep venous thrombosis, followed by pulmonary embolism...

, became seriously ill. A desperate retreat down the mountain followed, during which all but one of the climbers were nearly killed in a fall arrested by Pete Schoening

Pete Schoening

Peter K. Schoening was an American mountaineer. Schoening was one of two Americans to first successfully climb the Pakistani peak Gasherbrum I in 1958, and was one of the first to summit Mount Vinson in Antarctica in 1966. He was born July 30, 1927, in Seattle, Washington, and grew up in...

, and Gilkey later died in an apparent avalanche

Avalanche

An avalanche is a sudden rapid flow of snow down a slope, occurring when either natural triggers or human activity causes a critical escalating transition from the slow equilibrium evolution of the snow pack. Typically occurring in mountainous terrain, an avalanche can mix air and water with the...

. The expedition has been widely praised for the courage shown by the climbers in their attempt to save Gilkey, and for the team spirit and the bonds of friendship it fostered.

Background

By 1953, four expeditions had attempted to climb K2. Oscar EckensteinOscar Eckenstein

Oscar Johannes Ludwig Eckenstein was an English rock climber and mountaineer, and a pioneer in the sport of bouldering...

and Luigi Amedeo, Duke of the Abruzzi

Luigi Amedeo, Duke of the Abruzzi

Prince Luigi Amedeo Giuseppe Maria Ferdinando Francesco di Savoia-Aosta , Duke of the Abruzzi , was an Italian nobleman, mountaineer and explorer of the royal House of Savoy...

had led expeditions in 1902 and 1909 respectively, neither of which had made substantial progress, and the Duke of the Abruzzi had declared after his attempt that the mountain would never be climbed. However, two American expeditions in 1938 and 1939 had come closer to success. Charles Houston's 1938 expedition had established the feasibility of the Abruzzi Spur as a route to the summit, reaching the Shoulder at 8000m, before retreating due to diminishing supplies and the threat of bad weather. Fritz Wiessner

Fritz Wiessner

Fritz Wiessner was a pioneer of free climbing. Born in Dresden, Germany, he emigrated to New York City in 1929. He became a U.S. citizen in 1935.-Early days:...

's attempt the following year went even higher, but ended in disaster when four men disappeared high on the mountain. In spite of the tragedy, the expeditions had shown that climbing K2 was a realistic goal, and further attempts would almost certainly have been made sooner had the Second World War and the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947

Indo-Pakistani War of 1947

The India-Pakistan War of 1947-48, sometimes known as the First Kashmir War, was fought between India and Pakistan over the princely state of Kashmir and Jammu from 1947 to 1948. It was the first of four wars fought between the two newly independent nations...

not made travel to Kashmir

Kashmir

Kashmir is the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term Kashmir geographically denoted only the valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal mountain range...

impossible during the 1940s.

Expedition planning

In spite of the political difficulties they faced, Charles Houston and Robert BatesRobert Bates (mountaineer)

Robert Hicks Bates was an American mountaineer, author and teacher, who is best remembered for his parts in the first ascent of Mount Lucania and the American expeditions to K2 in 1938 and 1953.-Early life:...

had harboured hopes of returning to K2 since their initial attempt in 1938, and in 1952 Houston, with the aid of his friend Avra M. Warren

Avra M. Warren

Avra M. Warren served as the United States Ambassador to 4 countries and minister to 3 ....

, the U.S. Ambassador to Pakistan

United States Ambassador to Pakistan

The U.S. embassy in Karachi was established August 15, 1947 with Edward W. Holmes as Chargé d'Affaires ad interim, pending the appointment of an ambassador. The first ambassador, Paul H. Alling, was appointed on September 20, 1947. Anne W. Patterson was nominated as United States Ambassador to...

, obtained permission for an expedition the following year.

Houston and Bates planned the expedition as a lightweight one, incorporating many elements of what would later become known as the Alpine style

Alpine style

Alpine style refers to mountaineering in a self-sufficient manner, thereby carrying all of one's food, shelter, equipment etc. as one climbs, as opposed to expedition style mountaineering which involves setting up a fixed line of stocked camps on the mountain which can be accessed at one's leisure...

. There were practical reasons for this as well as stylistic ones. Since partition

Partition of India

The Partition of India was the partition of British India on the basis of religious demographics that led to the creation of the sovereign states of the Dominion of Pakistan and the Union of India on 14 and 15...

, the Indian Sherpa

Sherpa people

The Sherpa are an ethnic group from the most mountainous region of Nepal, high in the Himalayas. Sherpas migrated from the Kham region in eastern Tibet to Nepal within the last 300–400 years.The initial mountainous migration from Tibet was a search for beyul...

s who had traditionally served as porter

Porter (carrier)

A porter, also called a bearer, is a person who shifts objects for others.-Historical meaning:Human adaptability and flexibility early led to the use of humans for shifting gear...

s on Himalayan expeditions were unwelcome in Pakistan

Pakistan

Pakistan , officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan is a sovereign state in South Asia. It has a coastline along the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Oman in the south and is bordered by Afghanistan and Iran in the west, India in the east and China in the far northeast. In the north, Tajikistan...

, and few of the Hunza porters who would replace them had genuine mountaineering skills. Given the technical difficulty of the Abruzzi Spur it was therefore impractical to use porters to carry loads high on the mountain, so it was planned to use them only as far as Camp II. Additionally the steepness of the Abruzzi Spur meant there was limited flat space for tents, and camp sites to accommodate large numbers of climbers would be difficult to find. Houston and Bates therefore planned to assemble a small team of eight climbers and no high-altitude porters. The size of the team ruled out the use of supplemental oxygen

Oxygen

Oxygen is the element with atomic number 8 and represented by the symbol O. Its name derives from the Greek roots ὀξύς and -γενής , because at the time of naming, it was mistakenly thought that all acids required oxygen in their composition...

as there would not be enough manpower to carry the extra weight up the mountain, but Houston was confident from his own wartime experiments, as well as the experience of the pre-war British Everest

Mount Everest

Mount Everest is the world's highest mountain, with a peak at above sea level. It is located in the Mahalangur section of the Himalayas. The international boundary runs across the precise summit point...

expeditions, that it would be possible to climb K2 without it.

Houston and Bates considered many climbers, and selected them for their compatibility as a team and all-round experience rather than individual brilliance. Houston was aware that personality clashes between team members had been detrimental to other Karakoram

Karakoram

The Karakoram, or Karakorum , is a large mountain range spanning the borders between Pakistan, India and China, located in the regions of Gilgit-Baltistan , Ladakh , and Xinjiang region,...

expeditions, most notable Wiessner's, and was keen to avoid them. The six climbers selected were Robert Craig, a ski instructor from Seattle, Art Gilkey

Art Gilkey

Art Gilkey was an American geologist and mountaineer. He explored Alaska in 1950 and 1952. He died during a 1953 American expedition to K2. Approaching the summit of the peak, he suffered from thrombophlebitis or possibly deep venous thrombosis, followed by pulmonary embolism...

, a geologist

Geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the solid and liquid matter that constitutes the Earth as well as the processes and history that has shaped it. Geologists usually engage in studying geology. Geologists, studying more of an applied science than a theoretical one, must approach Geology using...

from Iowa

Iowa

Iowa is a state located in the Midwestern United States, an area often referred to as the "American Heartland". It derives its name from the Ioway people, one of the many American Indian tribes that occupied the state at the time of European exploration. Iowa was a part of the French colony of New...

, Dee Molenaar

Dee Molenaar

Dee Molenaar is an American mountaineer, author and artist from Burley, Washington. He is best known as the author of The Challenge of Rainier, first published in 1971 and considered the definitive work on the climbing history of Mount Rainier....

, a geologist and artist

Artist

An artist is a person engaged in one or more of any of a broad spectrum of activities related to creating art, practicing the arts and/or demonstrating an art. The common usage in both everyday speech and academic discourse is a practitioner in the visual arts only...

from Seattle, Pete Schoening

Pete Schoening

Peter K. Schoening was an American mountaineer. Schoening was one of two Americans to first successfully climb the Pakistani peak Gasherbrum I in 1958, and was one of the first to summit Mount Vinson in Antarctica in 1966. He was born July 30, 1927, in Seattle, Washington, and grew up in...

, also from Seattle and at 25 the youngest of the party, and George Bell

George Irving Bell

George Irving Bell was an American physicist, biologist and mountaineer, and a grandson of John Joseph Seerley. He died from complications of leukemia after surgery.-Education:...

, a nuclear scientist from Los Alamos

Los Alamos National Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory is a United States Department of Energy national laboratory, managed and operated by Los Alamos National Security , located in Los Alamos, New Mexico...

. The eighth member of the team was Tony Streather, an English

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

army officer who was initially appointed Transport Officer, but showed sufficient prowess to become a full member of the climbing team. The biggest disappointment was that William House, who had played a major role in the 1938 expedition, was unable to return for business reasons. Other talented climbers, such as Willi Unsoeld, Paul Petzoldt

Paul Petzoldt

Paul Kiesow Petzoldt was one of America's most accomplished mountaineers. He is perhaps best known for establishing the National Outdoor Leadership School in 1965. Paul made his first ascent of the Grand Teton in 1924 at the age of 16, becoming the youngest person at the time to have done so...

and Fritz Wiessner himself were controversially not included because it was not felt that they would gel with the rest of the team.

The expedition was privately funded, receiving no grants from either the government or American mountaineering bodies. The budget of $32,000 came from the team members themselves, some gifts, advances paid by the National Broadcasting Corporation and the Saturday Evening Post for a film and a series of newspaper articles, as well as significant loans. Some corporate sponsorship was also obtained, but mainly in the form of equipment and food rather than money.

Climbing, storm and illness

Rawalpindi

Rawalpindi , locally known as Pindi, is a city in the Pothohar region of Pakistan near Pakistan's capital city of Islamabad, in the province of Punjab. Rawalpindi is the fourth largest city in Pakistan after Karachi, Lahore and Faisalabad...

at the end of May, flew on to Skardu

Skardu

Skardu , is the main town of the region Baltistan and the capital of Skardu District, one of the districts making up Pakistan's Gilgit Baltistan....

, and after the long trek through Askole

Askole

Askole or Askoly is a small town located in the Braldu Valley in the most remote region of Karakoram mountains in Northern Areas, Pakistan. It is the last settlement before the wilderness of the Karakoram. Askole is the gateway to four of the world's fourteen highest peaks known as Eight-thousanders...

and up the Baltoro Glacier

Baltoro Glacier

The Baltoro Glacier, at 62 kilometers long, is one of the longest glaciers outside the polar regions. It is located in Baltistan, in the Gilgit-Baltistan region of Pakistan, and runs through part of the Karakoram mountain range. The Baltoro Muztagh lies to the north and east of the glacier, while...

, arriving at the base of K2 on 20 June. The early stages of the climb proceeded smoothly, though progress was slow due to the expedition's tactics. The tragedies on Nanga Parbat

Nanga Parbat

Nanga Parbat is the ninth highest mountain on Earth, the second highest mountain in Pakistan and among the eight-thousanders with a summit elevation of 8,126 meters...

in 1934 and K2 in 1939 had convinced Houston of the importance of keeping all camps well stocked at all times in case the expedition had to retreat in bad weather. Doing this required the climbers to make extra journeys up and down the mountain carrying extra supplies, but was to prove crucial to their survival.

By 1 August the route had been pushed as far as Camp VIII, at the base of the Shoulder at around 7800m, and the next day the whole team assembled there to prepare for the final push for the summit. However, the weather had been gradually deteriorating for several days, and soon a severe storm broke. At first it did not dispirit the team, and a secret ballot

Secret ballot

The secret ballot is a voting method in which a voter's choices in an election or a referendum are anonymous. The key aim is to ensure the voter records a sincere choice by forestalling attempts to influence the voter by intimidation or bribery. The system is one means of achieving the goal of...

was held to decide which climbers should make the first summit attempt. However, as the storm continued for day after day their position became more serious. One of the tents collapsed on the fourth night, forcing Houston and Bell to crowd into other, already cramped tents. On August the 6th, with weather forecasts offering little hope of improvement, the party for the first time discussed retreating.

The next day the weather improved, but thoughts of attempting the summit were quickly abandoned when Art Gilkey collapsed just outside his tent. Houston diagnosed him as suffering from thrombophlebitis

Thrombophlebitis

Thrombophlebitis is phlebitis related to a thrombus . When it occurs repeatedly in different locations, it is known as "Thrombophlebitis migrans" or "migrating thrombophlebitis".-Signs and symptoms:...

- blood clots

Thrombus

A thrombus , or blood clot, is the final product of the blood coagulation step in hemostasis. It is achieved via the aggregation of platelets that form a platelet plug, and the activation of the humoral coagulation system...

which would be dangerous at sea level, but would almost certainly be fatal at 7800m. The whole team was now forced into a desperate attempt to save him. While they believed that there was little or no chance of saving him, the possibility of abandoning him was never discussed. However, the unacceptable avalanche

Avalanche

An avalanche is a sudden rapid flow of snow down a slope, occurring when either natural triggers or human activity causes a critical escalating transition from the slow equilibrium evolution of the snow pack. Typically occurring in mountainous terrain, an avalanche can mix air and water with the...

risk followed by a renewal of the storm prevented a descent at that time, and the team remained at Camp VIII for several more days in the hope that the weather would improve.

Attempted rescue and fall

By 10 August the situation had become critical: Gilkey was showing signs of pulmonary embolismPulmonary embolism

Pulmonary embolism is a blockage of the main artery of the lung or one of its branches by a substance that has travelled from elsewhere in the body through the bloodstream . Usually this is due to embolism of a thrombus from the deep veins in the legs, a process termed venous thromboembolism...

and deteriorating quickly, and the whole team was still trapped at an altitude that would have eventually killed them all. In spite of the continuing storm and avalanche risk the team decided they had no choice but to descend. On a makeshift stretcher made from canvas, ropes and a sleeping bag, Gilkey was pulled or lowered down steep terrain, until the team reached a point where they could traverse

Traverse (climbing)

A traverse is a lateral move or route when climbing; going mainly sideways rather than up or down. Traversing a climbing wall is a good warm-up exercise....

a difficult ice slope to their Camp VII, at around 7500m.

A mass fall occurred as the climbers began the traverse. George Bell slipped and fell on a patch of hard ice, pulling off his rope-mate Tony Streather. As they fell their rope became tangled with those connecting Houston, Bell, Gilkey and Molenaar, pulling all these climbers off as well. Finally the strain came onto Pete Schoening, who had been belaying

Belaying

thumb|200px|right|A belayer is belaying behind a lead climberBelaying refers to a variety of techniques used in climbing to exert friction on a climbing rope so that a falling climber does not fall very far...

Gilkey and Molenaar. Quickly wrapping the rope around his shoulders and ice axe

Ice axe

An ice axe, is a multi-purpose ice and snow tool used by mountaineers both in the ascent and descent of routes which involve frozen conditions. It can be held and employed in a number of different ways, depending on the terrain encountered...

, Schoening held all six climbers, some of whom had by that point fallen over 100m. Had he not done so, the entire team, apart from Craig who was unroped, would have fallen around 2000m to the Godwin-Austen Glacier

Godwin-Austen Glacier

The Godwin-Austen Glacier is located near K2 in the Gilgit-Baltistan region of Pakistan. Its confluence with the Baltoro Glacier is called Concordia and is one of the most favorite spots for trekking in Pakistan since it provides excellent views of four of the five eight-thousanders in Pakistan.The...

.

After the climbers had recovered and made their way to the tent at Camp VII, Gilkey was lost. He had been anchored

Anchor (climbing)

In rock climbing, an anchor can be any way of attaching the climber, the rope, or a load to rock, ice, steep dirt, or a building by either permanent or temporary means...

to the ice slope as the exhausted climbers prepared the tent, and his muffled shouts were heard. When Bates and Streather returned to bring him to the tent, they found no sign of him. A faint groove in the snow suggested that an avalanche had taken place.

Authors such as Jim Curran have suggested that Gilkey's death, while tragic, undoubtedly saved the lives of the rest of the team, who were now free to concentrate on their own survival. Houston has agreed with this assessment, but Pete Schoening always believed, based on his other experiences of mountain rescue

Mountain rescue

Mountain rescue refers to search and rescue activities that occur in a mountainous environment, although the term is sometimes also used to apply to search and rescue in other wilderness environments. The difficult and remote nature of the terrain in which mountain rescue often occurs has resulted...

, that the team could have successfully completed the rescue, albeit with more frostbite

Frostbite

Frostbite is the medical condition where localized damage is caused to skin and other tissues due to extreme cold. Frostbite is most likely to happen in body parts farthest from the heart and those with large exposed areas...

than they eventually suffered. There is also controversy over the manner of Gilkey's death. Tom Hornbein

Tom Hornbein

Thomas "Tom" Hornbein is a well-known American mountaineer.Born in St. Louis, Missouri, Hornbein developed an interest in geology as a teenager. His study of geology led to a fascination with mountains. Eventually he also became interested in medicine; he studied and worked as an anesthesiologist...

and others have suggested that, realising his rescue was endangering the lives of the others, Gilkey might have managed to work himself loose from the mountainside. Charles Houston initially thought that this would not have been possible, believing that Gilkey, who was sedated with morphine

Morphine

Morphine is a potent opiate analgesic medication and is considered to be the prototypical opioid. It was first isolated in 1804 by Friedrich Sertürner, first distributed by same in 1817, and first commercially sold by Merck in 1827, which at the time was a single small chemists' shop. It was more...

would have been too weak to have removed the anchors. However, reviewing events for a documentary in 2003 he became convinced that Gilkey had indeed ended his own life. Others however, such as Robert Bates, remained convinced that Gilkey died as a result of an accident rather than suicide.

The descent from Camp VII to Base Camp took a further five days and was itself gruelling; all the climbers were exhausted, George Bell had badly frostbitten feet and Charles Houston, who had suffered a head injury

Head injury

Head injury refers to trauma of the head. This may or may not include injury to the brain. However, the terms traumatic brain injury and head injury are often used interchangeably in medical literature....

, was dazed and concussed. Houston has said that while he is proud of the team's attempt to rescue Gilkey, he feels that making the remainder of the descent safely was an even greater achievement. During the descent the climbers saw a broken ice-axe and some bloodstained rocks, but no other trace of Art Gilkey was found.

On the team's descent to Base Camp, a memorial cairn

Cairn

Cairn is a term used mainly in the English-speaking world for a man-made pile of stones. It comes from the or . Cairns are found all over the world in uplands, on moorland, on mountaintops, near waterways and on sea cliffs, and also in barren desert and tundra areas...

was erected to Art Gilkey, and a service was held. The Gilkey Memorial has since become the burial place of other climbers who have died on K2, as well as a memorial to those whose bodies have not been found.

Aftermath and legacy

In spite of the trauma of the expedition, Charles Houston was keen to make another attempt on K2, and requested permission for further expedition in 1954. He was extremely disappointed that a large ItalianItaly

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

expedition had booked the mountain that year. The Italian expedition was successful, and while Houston had permission for 1955 he did not take it up, and gave up mountaineering in order to concentrate on his career researching high altitude medicine. Pete Schoening, however, returned to the Karakoram in 1958 and, with Andy Kauffman made the first ascent of Gasherbrum I

Gasherbrum I

Gasherbrum I , also known as Hidden Peak or K5, is the 11th highest peak on Earth, located on the Pakistan-China border in Gilgit-Baltistan region of Pakistan and Xinjiang region of China. Gasherbrum I is part of the Gasherbrum massif, located in the Karakoram region of the Himalaya...

; at 8080m the highest first ascent

First ascent

In climbing, a first ascent is the first successful, documented attainment of the top of a mountain, or the first to follow a particular climbing route...

ever made by an American team.

The account of the expedition, written by Bates and Houston with additional sections by the other climbers, was published in 1954 as K2 - The Savage Mountain. It received widespread acclaim, and is regarded as a mountaineering classic.

Jim Wickwire

Jim Wickwire is a retired attorney in Seattle, Washington, most famous as the first American to reach the top of K2, the world's second-highest mountain, and then for surviving the night in the open just below the summit....

, who made the first American ascent of K2 in 1978, described their courage and character as "one of the greatest mountaineering stories of all time", and wrote in a letter to Houston that to have climbed on the 1953 expedition would have been even better than climbing K2 in 1978. Many years after the expedition, Reinhold Messner

Reinhold Messner

Reinhold Messner is an Italian mountaineer and explorer from Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol "whose astonishing feats on Everest and on peaks throughout the world have earned him the status of the greatest climber in history." He is renowned for making the first solo ascent of Mount Everest without...

, the first man to climb all fourteen 8000m peaks said that while he had great respect for the Italian team which first climbed K2, he had even more respect for the American team, adding that while they failed, "they failed in the most beautiful way you can imagine."

In 1981 the American Alpine Club

American Alpine Club

The American Alpine Club, or AAC, was founded in 1902 by Charles Ernest Fay, and is the leading national organization in the United States devoted to mountaineering, climbing, and the multitude of issues facing climbers...

established the David A. Sowles Memorial Award

David A. Sowles Memorial Award

The David A. Sowles Memorial Award is the American Alpine Club's highest award for valour, bestowed at irregular intervals on mountaineers who have "distinguished themselves, with unselfish devotion at personal risk or sacrifice of a major objective, in going to the assistance of fellow climbers...

for "mountaineers who have distinguished themselves, with unselfish devotion at personal risk or sacrifice of a major objective, in going to the assistance of fellow climbers imperilled in the mountains." The surviving members of the Third American Karakoram Expedition were among the first recipients.

Schoening's action in arresting the mass fall has itself achieved iconic status, and is known in American climbing circles simply as "The Belay". Schoening himself, however, was always modest about his achievement, claiming that he was merely lucky.