Treaty of Devol

Encyclopedia

The Treaty of Devol was an agreement made in 1108 between Bohemond I of Antioch

and Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos

, in the wake of the First Crusade

. It is named after the Byzantine fortress of Devol

in Macedonia

(in modern Albania

). Although the treaty was not immediately enforced, it was intended to make the Principality of Antioch

a vassal

state of the Byzantine Empire

.

At the beginning of the First Crusade

, Crusader armies assembled at Constantinople

and promised to return to the Byzantine Empire any land they might conquer. However, Bohemond, the son of Alexios' former enemy Robert Guiscard

, claimed the Principality of Antioch

for himself. Alexios did not recognize the legitimacy of the Principality, and Bohemond went to Europe looking for reinforcements. He launched into open warfare against Alexios, but he was soon forced to surrender and negotiate with Alexios at the imperial camp at Diabolis (Devol), where the Treaty was signed.

Under the terms of the Treaty, Bohemond agreed to become a vassal of the Emperor and to defend the Empire whenever needed. He also accepted the appointment of a Greek Patriarch. In return, he was given the titles of sebastos

and doux

(duke) of Antioch, and he was guaranteed the right to pass on to his heirs the County of Edessa

. Following this, Bohemond retreated to Apulia

and died there. His nephew, Tancred

, who was regent in Antioch, refused to accept the terms of the Treaty. Antioch came temporarily under Byzantine sway in 1137, but it was not until 1158 that it truly became a Byzantine vassal.

The Treaty of Devol is viewed as a typical example of the Byzantine tendency to settle disputes through diplomacy

rather than warfare, and was both a result of and a cause for the distrust between the Byzantines and their Western Europe

an neighbors.

In 1097, the Crusader armies assembled at Constantinople having traveled in groups eastward through Europe. Alexios I, who had requested only some western knights to serve as mercenaries

In 1097, the Crusader armies assembled at Constantinople having traveled in groups eastward through Europe. Alexios I, who had requested only some western knights to serve as mercenaries

to help fight the Seljuk Turks, blockaded these armies in the city and would not permit them to leave until their leaders swore oath

s promising to restore to the Empire any land formerly belonging to it that they might conquer on the way to Jerusalem. The Crusaders eventually swore these oaths, individually rather than as a group; some, such as Raymond IV

of Toulouse

, were probably sincere, but others, such as Bohemond, probably never intended to honor their promise. In return, Alexios gave them guides and a military escort. The Crusaders were however exasperated by Byzantine tactics, such as negotiating the surrender of Nicaea

from the Seljuks while it was still under siege

by the Crusaders, who hoped to plunder it to help finance their journey. The Crusaders, feeling betrayed by Alexios, who was able to recover a number of important cities and islands, and in fact much of western Asia Minor, continued on their way without Byzantine aid. In 1098, when Antioch

had been captured after a long siege and the Crusaders were in turn themselves besieged in the city, Alexios marched out to meet them, but, hearing from Stephen of Blois

that the situation was hopeless, he returned to Constantinople. The Crusaders, who had unexpectedly withstood the siege, believed Alexios had abandoned them and considered the Byzantines completely untrustworthy. Therefore, they regarded their oaths as invalidated.

By 1100, there were several Crusader states

, including the Principality of Antioch, founded by Bohemond in 1098. It was argued that Antioch should be returned to the Byzantines, despite Alexios's supposed betrayals, but Bohemond claimed it for himself. Alexios, of course, disagreed; Antioch had an important port, was a trade hub with Asia and a stronghold of the Eastern Orthodox Church

, with an important Greek Patriarch. It had only been captured from the empire a few decades previously, unlike Jerusalem, which was much farther away and had not been in Byzantine hands for centuries. Alexios therefore did not recognize the legitimacy of the Principality, believing it should be returned to the Empire according to the oaths Bohemond had sworn in 1097. He therefore set about trying to evict Bohemond from Antioch.

Bohemond added a further insult to both Alexios and the Orthodox Church in 1100 when he appointed Bernard of Valence as the Latin Patriarch

, and the same time expelled the Greek Patriarch, John the Oxite

, who fled to Constantinople. Soon after, Bohemond was captured by the Danishmends

of Syria and was imprisoned for three years, during which the Antiochenes chose his nephew Tancred

as regent

. After Bohemond was released, he was defeated by the Seljuks at the Battle of Harran

in 1104; this defeat led to renewed pressure on Antioch from both the Seljuks and the Byzantines. Bohemond left Tancred in control of Antioch and returned in the West, touring Italy and France for reinforcements. He won the backing of Pope Paschal II

and the support of the French King Philip I

, whose daughter he married. It is unclear whether his expedition qualified as a crusade.

Bohemond's Norman

relatives in Sicily

had been in conflict with the Byzantine Empire for over 30 years; his father Robert Guiscard

was one of the Empire's most formidable enemies. While Bohemond was away, Alexios sent an army to reoccupy Antioch and the cities of Cilicia

. In 1107, having organized a new army for his planned crusade against the Muslims in Syria, Bohemond instead launched into open warfare against Alexios, crossing the Adriatic to besiege Dyrrhachium

, the westernmost city of the Empire. Like his father however, Bohemond was unable to make any significant advances into the Empire's interior; Alexios avoided a pitched battle and Bohemond's siege failed, partly due to a plague among his army. Bohemond soon found himself in an impossible position, isolated in front of Dyrrhachium: his escape by sea was cut off by the Venetians

, and Paschal II withdrew his support.

In September 1108, Alexios requested that Bohemond negotiate with him at the imperial camp at Diabolis (Devol). Bohemond had no choice but to accept, now that his disease-stricken army would no longer be able to defeat Alexios in battle. He admitted that he had violated the oath sworn in 1097, but refused to acknowledge that it had any bearing on the present circumstances, as Alexios, in Bohemond's eyes, had also violated the agreement by turning back from the siege of Antioch in 1098. Alexios agreed to consider the oaths of 1097 invalid. The specific terms of the treaty were negotiated by the general Nikephoros Bryennios, and were recorded by Anna Komnene

In September 1108, Alexios requested that Bohemond negotiate with him at the imperial camp at Diabolis (Devol). Bohemond had no choice but to accept, now that his disease-stricken army would no longer be able to defeat Alexios in battle. He admitted that he had violated the oath sworn in 1097, but refused to acknowledge that it had any bearing on the present circumstances, as Alexios, in Bohemond's eyes, had also violated the agreement by turning back from the siege of Antioch in 1098. Alexios agreed to consider the oaths of 1097 invalid. The specific terms of the treaty were negotiated by the general Nikephoros Bryennios, and were recorded by Anna Komnene

:

The terms were negotiated according to Bohemond's western understanding, so that he saw himself as a feudal

vassal of Alexios, a "liege man" (homo ligius or ) with all the obligations this implied, as customary in the West: he was obliged to bring military assistance to the Emperor, except in wars in which he was involved, and to serve him against all his enemies, in Europe and in Asia.

Anna Komnene described the proceedings with very repetitive details, with Bohemond frequently pointing out his own mistakes and praising the benevolence of Alexios and the Empire; the proceedings must have been rather humiliating for Bohemond. On the other hand, Anna's work was meant to praise her father and the terms of the treaty may not be entirely accurate.

The oral agreement was written down in two copies, one given to Alexios, and the other given to Bohemond. According to Anna, the witnesses from Bohemond's camp who signed his copy of the treaty were Maurus, bishop of Amalfi and papal legate

, Renard, bishop of Tarentum, and the minor clergy accompanying them; the abbot of the monastery of St. Andrew in Brindisi

, along with two of his monks; and a number of unnamed "pilgrims" (probably soldiers in Bohemond's army). From Alexios' imperial court, the treaty was witnessed by the sebastos Marinos of Naples

, Roger son of Dagobert

, Peter Aliphas, William of Gand, Richard of the Principate, Geoffrey of Mailli, Hubert son of Raoul

, Paul the Roman, the ambassadors Peres and Simon from Hungary, and the ambassadors Basil the Eunuch and Constantine. Many of Alexios' witnesses were themselves Westerners, who held high positions in the Byzantine army

and at the imperial court; Basil and Constantine were ambassadors in the service of Bohemond's relatives in Sicily

.

Neither copy survives. It may have been written in Latin

, Greek

, or both. Both languages are equally likely given the number of westerners present, many of whom would have known Latin. It is not clear how far Bohemond's concessions were known across Latin Europe

as only a few chroniclers mention the treaty at all; Fulcher of Chartres

simply says

that Bohemond and Alexios were reconciled.

The Treaty was weighted in Alexios' favor and provided for the eventual absorption of Antioch and its territory into the Empire. Alexios, recognizing the impossibility of driving Bohemond out of Antioch, tried to absorb him into the structure of Byzantine rule, and put him work for the Empire's benefit. Bohemond was to retain Antioch until his death with the title of doux, unless the emperor (either Alexios or, in the future, John) chose for any reason to renege on the deal. The principality would revert to direct Byzantine rule on Bohemond's death. Bohemond therefore could not set up a dynasty in Antioch, although he was guaranteed the right to pass on to his heirs the County of Edessa, and any other territories he managed to acquire in the Syrian interior.

The Treaty was weighted in Alexios' favor and provided for the eventual absorption of Antioch and its territory into the Empire. Alexios, recognizing the impossibility of driving Bohemond out of Antioch, tried to absorb him into the structure of Byzantine rule, and put him work for the Empire's benefit. Bohemond was to retain Antioch until his death with the title of doux, unless the emperor (either Alexios or, in the future, John) chose for any reason to renege on the deal. The principality would revert to direct Byzantine rule on Bohemond's death. Bohemond therefore could not set up a dynasty in Antioch, although he was guaranteed the right to pass on to his heirs the County of Edessa, and any other territories he managed to acquire in the Syrian interior.

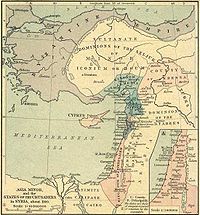

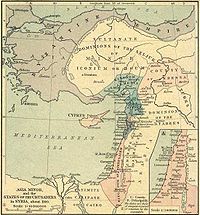

Bohemond's lands were to include St Simeon and the coast, the towns of Baghras and Artah, and the Latin possessions in the Jebel as-Summaq. Latakia

and Cilicia

, however, were to revert to direct Byzantine rule. As Thomas Asbridge

points out, much of what the Emperor granted to Bohemond (including Aleppo itself) was still in Muslim hands (e.g. neither Bohemond nor Alexios controlled Edessa, although at the time Tancred was regent there as well as in Antioch), which contradicts Lilie's assessment that Bohemond did well out of the Treaty. René Grousset

calls the Treaty a "Diktat

", but Jean Richard underscores that the rules of feudal law to which Bohemond had to submit "were in no way humiliating." According to John W. Birkenmeier, the Treaty marked the point at which Alexios had developed a new army

, and new tactical doctrines with which to use it, but it was not a Byzantine political success; "it traded Bohemond's freedom for a titular overlordship of Southern Italy that could never be effective, and for an occupation of Antioch that could never be carried out."

The terms of the Treaty have been interpreted in various ways. According to Paul Magdalino and Ralph-Johannes Lilie, "the Treaty as reproduced by Anna Komnene shows an astonishing familiarity with western feudal custom; whether it was drafted by a Greek or by a Latin in imperial service, it had a sensitive regard for the western view of the status quo

in the East Mediterranean." So too did the diplomatic initiatives Alexios undertook, in order to enforce the Treaty on Tancred (such as the treaty he concluded with Pisa in 1110–1111, and the negotiations for Church union with Pascal II in 1112). In contrast, Asbridge has recently argued that the Treaty derived from Greek as well as western precedents, and that Alexios wished to regard Antioch as falling under the umbrella of pronoia

arrangements.

Bohemond never returned to Antioch (he went to Sicily where he died in 1111), and the carefully constructed clauses of the Treaty were never implemented. Bohemond's nephew, Tancred, refused to honor the Treaty. In his mind, Antioch was his by right of conquest

Bohemond never returned to Antioch (he went to Sicily where he died in 1111), and the carefully constructed clauses of the Treaty were never implemented. Bohemond's nephew, Tancred, refused to honor the Treaty. In his mind, Antioch was his by right of conquest

. He saw no reason to hand it over to someone who had not been involved in the Crusade, and had indeed actively worked against it (as the Crusaders believed). The Crusaders seem to have felt Alexios had tricked Bohemond into giving him Antioch; they already believed Alexios was devious and untrustworthy and this may have confirmed their beliefs. The treaty referred to Tancred as the illegal holder of Antioch, and Alexios had expected Bohemond to expel him or somehow control him. Tancred also did not allow a Greek Patriarch to enter the city; instead, Greek Patriarchs were appointed in Constantinople and nominally held power there.

The question of the status of Antioch and the adjacent Cilician cities troubled the Empire for many years afterwards. Although the Treaty of Devol never came into effect, it provided the legal basis for Byzantine negotiations with the crusaders for the next thirty years, and for imperial claims to Antioch during the reigns of John II

and Manuel I

. Therefore, John II attempted to impose his authority, traveling to Antioch himself in 1137 with his army and besieging the city. The citizens of Antioch tried to negotiate, but John demanded the unconditional surrender of the city. After asking the permission of the King of Jerusalem, Fulk, which he received, Raymond

, the Prince of Antioch, agreed to surrender the city to John. The agreement, by which Raymond swore homage to John, was explicitly based on the Treaty of Devol, but went beyond it: Raymond, who was recognized as an imperial vassal for Antioch, promised the Emperor free entry to Antioch, and undertook to hand over the city in return for investiture with Aleppo, Shaizar

, Homs

and Hama

as soon as these were conquered from the Muslims. Then, Raymond would rule the new conquests and Antioch would revert to direct imperial rule. The campaign finally failed, however, partly because Raymond and Joscelin II, Count of Edessa

, who had been obliged to join John as his vassals, did not pull their weight. When, on their return to Antioch, John insisted on taking possession of the city, the two princes organized a riot. John found himself besieged in the city, and was forced to leave in 1138, recalled to Constantinople. He diplomatically accepted Raymond's and Joscelin's insistence that they had nothing to do with the rebellion. John repeated his operation in 1142, but he unexpectedly died, and the Byzantine army retired.

It was not until 1158, during the reign of Manuel I, that Antioch truly became a vassal of the empire, after Manuel forced Prince Raynald of Châtillon

to swear fealty

to him in punishment for Raynald's attack on Byzantine Cyprus

. The Greek Patriarch was restored, and ruled simultaneously with the Latin Patriarch. Antioch, weakened by powerless regents after Raynald's capture by the Muslims in 1160, remained a Byzantine vassal state until 1182 when internal divisions following Manuel's death in 1180 hindered the Empire's ability to enforce its claim.

In the Balkan frontier, the Treaty of Devol marked the end of the Norman threat to the southern Adriatic littoral during Alexios' reign and later; the efficacy of the frontier defenses deterred any further invasions through Dyrrachium for most of the 12th century.

Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes was an ancient city on the eastern side of the Orontes River. It is near the modern city of Antakya, Turkey.Founded near the end of the 4th century BC by Seleucus I Nicator, one of Alexander the Great's generals, Antioch eventually rivaled Alexandria as the chief city of the...

and Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos

Alexios I Komnenos

Alexios I Komnenos, Latinized as Alexius I Comnenus , was Byzantine emperor from 1081 to 1118, and although he was not the founder of the Komnenian dynasty, it was during his reign that the Komnenos family came to full power. The title 'Nobilissimus' was given to senior army commanders,...

, in the wake of the First Crusade

First Crusade

The First Crusade was a military expedition by Western Christianity to regain the Holy Lands taken in the Muslim conquest of the Levant, ultimately resulting in the recapture of Jerusalem...

. It is named after the Byzantine fortress of Devol

Devol (Albania)

Devol , also Deabolis or Diabolis) was a medieval fortress and bishopric in western Macedonia, located south of Lake Ohrid in what is today the south-eastern corner of Albania . Its precise location is unknown today, but it is thought to have been located by the river of the same name , and on...

in Macedonia

Macedonia (region)

Macedonia is a geographical and historical region of the Balkan peninsula in southeastern Europe. Its boundaries have changed considerably over time, but nowadays the region is considered to include parts of five Balkan countries: Greece, the Republic of Macedonia, Bulgaria, Albania, Serbia, as...

(in modern Albania

Albania

Albania , officially known as the Republic of Albania , is a country in Southeastern Europe, in the Balkans region. It is bordered by Montenegro to the northwest, Kosovo to the northeast, the Republic of Macedonia to the east and Greece to the south and southeast. It has a coast on the Adriatic Sea...

). Although the treaty was not immediately enforced, it was intended to make the Principality of Antioch

Principality of Antioch

The Principality of Antioch, including parts of modern-day Turkey and Syria, was one of the crusader states created during the First Crusade.-Foundation:...

a vassal

Vassal

A vassal or feudatory is a person who has entered into a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. The obligations often included military support and mutual protection, in exchange for certain privileges, usually including the grant of land held...

state of the Byzantine Empire

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire was the Eastern Roman Empire during the periods of Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, centred on the capital of Constantinople. Known simply as the Roman Empire or Romania to its inhabitants and neighbours, the Empire was the direct continuation of the Ancient Roman State...

.

At the beginning of the First Crusade

First Crusade

The First Crusade was a military expedition by Western Christianity to regain the Holy Lands taken in the Muslim conquest of the Levant, ultimately resulting in the recapture of Jerusalem...

, Crusader armies assembled at Constantinople

Constantinople

Constantinople was the capital of the Roman, Eastern Roman, Byzantine, Latin, and Ottoman Empires. Throughout most of the Middle Ages, Constantinople was Europe's largest and wealthiest city.-Names:...

and promised to return to the Byzantine Empire any land they might conquer. However, Bohemond, the son of Alexios' former enemy Robert Guiscard

Robert Guiscard

Robert d'Hauteville, known as Guiscard, Duke of Apulia and Calabria, from Latin Viscardus and Old French Viscart, often rendered the Resourceful, the Cunning, the Wily, the Fox, or the Weasel was a Norman adventurer conspicuous in the conquest of southern Italy and Sicily...

, claimed the Principality of Antioch

Principality of Antioch

The Principality of Antioch, including parts of modern-day Turkey and Syria, was one of the crusader states created during the First Crusade.-Foundation:...

for himself. Alexios did not recognize the legitimacy of the Principality, and Bohemond went to Europe looking for reinforcements. He launched into open warfare against Alexios, but he was soon forced to surrender and negotiate with Alexios at the imperial camp at Diabolis (Devol), where the Treaty was signed.

Under the terms of the Treaty, Bohemond agreed to become a vassal of the Emperor and to defend the Empire whenever needed. He also accepted the appointment of a Greek Patriarch. In return, he was given the titles of sebastos

Sebastos

Sebastos was an honorific used by the ancient Greeks to render the Roman imperial title of Augustus. From the late 11th century on, during the Komnenian period, it and variants derived from it formed the basis of a new system of court titles for the Byzantine Empire. The female form of the title...

and doux

Dux

Dux is Latin for leader and later for Duke and its variant forms ....

(duke) of Antioch, and he was guaranteed the right to pass on to his heirs the County of Edessa

County of Edessa

The County of Edessa was one of the Crusader states in the 12th century, based around Edessa, a city with an ancient history and an early tradition of Christianity....

. Following this, Bohemond retreated to Apulia

Apulia

Apulia is a region in Southern Italy bordering the Adriatic Sea in the east, the Ionian Sea to the southeast, and the Strait of Òtranto and Gulf of Taranto in the south. Its most southern portion, known as Salento peninsula, forms a high heel on the "boot" of Italy. The region comprises , and...

and died there. His nephew, Tancred

Tancred, Prince of Galilee

Tancred was a Norman leader of the First Crusade who later became Prince of Galilee and regent of the Principality of Antioch...

, who was regent in Antioch, refused to accept the terms of the Treaty. Antioch came temporarily under Byzantine sway in 1137, but it was not until 1158 that it truly became a Byzantine vassal.

The Treaty of Devol is viewed as a typical example of the Byzantine tendency to settle disputes through diplomacy

Byzantine diplomacy

Byzantine diplomacy concerns the principles, methods, mechanisms, ideals, and techniques that the Byzantine Empire espoused and used in order to negotiate with other states and to promote the goals of its foreign policy...

rather than warfare, and was both a result of and a cause for the distrust between the Byzantines and their Western Europe

Western Europe

Western Europe is a loose term for the collection of countries in the western most region of the European continents, though this definition is context-dependent and carries cultural and political connotations. One definition describes Western Europe as a geographic entity—the region lying in the...

an neighbors.

Background

Mercenary

A mercenary, is a person who takes part in an armed conflict based on the promise of material compensation rather than having a direct interest in, or a legal obligation to, the conflict itself. A non-conscript professional member of a regular army is not considered to be a mercenary although he...

to help fight the Seljuk Turks, blockaded these armies in the city and would not permit them to leave until their leaders swore oath

Oath

An oath is either a statement of fact or a promise calling upon something or someone that the oath maker considers sacred, usually God, as a witness to the binding nature of the promise or the truth of the statement of fact. To swear is to take an oath, to make a solemn vow...

s promising to restore to the Empire any land formerly belonging to it that they might conquer on the way to Jerusalem. The Crusaders eventually swore these oaths, individually rather than as a group; some, such as Raymond IV

Raymond IV of Toulouse

Raymond IV of Toulouse , sometimes called Raymond of St Gilles, was Count of Toulouse, Duke of Narbonne, and Margrave of Provence and one of the leaders of the First Crusade. He was a son of Pons of Toulouse and Almodis de La Marche...

of Toulouse

Toulouse

Toulouse is a city in the Haute-Garonne department in southwestern FranceIt lies on the banks of the River Garonne, 590 km away from Paris and half-way between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea...

, were probably sincere, but others, such as Bohemond, probably never intended to honor their promise. In return, Alexios gave them guides and a military escort. The Crusaders were however exasperated by Byzantine tactics, such as negotiating the surrender of Nicaea

Iznik

İznik is a city in Turkey which is primarily known as the site of the First and Second Councils of Nicaea, the first and seventh Ecumenical councils in the early history of the Church, the Nicene Creed, and as the capital city of the Empire of Nicaea...

from the Seljuks while it was still under siege

Siege of Nicaea

The Siege of Nicaea took place from May 14 to June 19, 1097, during the First Crusade.-Background:Nicaea , located on the eastern shore of Lake İznik, had been captured from the Byzantine Empire by the Seljuk Turks in 1081, and formed the capital of the Sultanate of Rüm...

by the Crusaders, who hoped to plunder it to help finance their journey. The Crusaders, feeling betrayed by Alexios, who was able to recover a number of important cities and islands, and in fact much of western Asia Minor, continued on their way without Byzantine aid. In 1098, when Antioch

Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes was an ancient city on the eastern side of the Orontes River. It is near the modern city of Antakya, Turkey.Founded near the end of the 4th century BC by Seleucus I Nicator, one of Alexander the Great's generals, Antioch eventually rivaled Alexandria as the chief city of the...

had been captured after a long siege and the Crusaders were in turn themselves besieged in the city, Alexios marched out to meet them, but, hearing from Stephen of Blois

Stephen II, Count of Blois

Stephen II Henry , Count of Blois and Count of Chartres, was the son of Theobald III, count of Blois, and Garsinde du Maine. He married Adela of Normandy, a daughter of William the Conqueror around 1080 in Chartres...

that the situation was hopeless, he returned to Constantinople. The Crusaders, who had unexpectedly withstood the siege, believed Alexios had abandoned them and considered the Byzantines completely untrustworthy. Therefore, they regarded their oaths as invalidated.

By 1100, there were several Crusader states

Crusader states

The Crusader states were a number of mostly 12th- and 13th-century feudal states created by Western European crusaders in Asia Minor, Greece and the Holy Land , and during the Northern Crusades in the eastern Baltic area...

, including the Principality of Antioch, founded by Bohemond in 1098. It was argued that Antioch should be returned to the Byzantines, despite Alexios's supposed betrayals, but Bohemond claimed it for himself. Alexios, of course, disagreed; Antioch had an important port, was a trade hub with Asia and a stronghold of the Eastern Orthodox Church

Eastern Orthodox Church

The Orthodox Church, officially called the Orthodox Catholic Church and commonly referred to as the Eastern Orthodox Church, is the second largest Christian denomination in the world, with an estimated 300 million adherents mainly in the countries of Belarus, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Georgia, Greece,...

, with an important Greek Patriarch. It had only been captured from the empire a few decades previously, unlike Jerusalem, which was much farther away and had not been in Byzantine hands for centuries. Alexios therefore did not recognize the legitimacy of the Principality, believing it should be returned to the Empire according to the oaths Bohemond had sworn in 1097. He therefore set about trying to evict Bohemond from Antioch.

Bohemond added a further insult to both Alexios and the Orthodox Church in 1100 when he appointed Bernard of Valence as the Latin Patriarch

Latin Patriarch of Antioch

The Latin Patriarch of Antioch was an office created in 1098 by Bohemund, founder of the Principality of Antioch, one of the crusader states....

, and the same time expelled the Greek Patriarch, John the Oxite

John the Oxite

John VII the Oxite was the Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch at the time of the Siege of Antioch in 1097 in front of the besieging army of the First Crusade. He was imprisoned by the Turkish governor, Yaghi-Siyan, who suspected his loyalty. On occasion he was hung from the walls and his feet were hit...

, who fled to Constantinople. Soon after, Bohemond was captured by the Danishmends

Danishmends

The Danishmend dynasty was a Turcoman dynasty that ruled in north-central and eastern Anatolia in the 11th and 12th centuries. The centered originally around Sivas, Tokat, and Niksar in central-northeastern Anatolia, they extended as far west as Ankara and Kastamonu for a time, and as far south as...

of Syria and was imprisoned for three years, during which the Antiochenes chose his nephew Tancred

Tancred, Prince of Galilee

Tancred was a Norman leader of the First Crusade who later became Prince of Galilee and regent of the Principality of Antioch...

as regent

Regent

A regent, from the Latin regens "one who reigns", is a person selected to act as head of state because the ruler is a minor, not present, or debilitated. Currently there are only two ruling Regencies in the world, sovereign Liechtenstein and the Malaysian constitutive state of Terengganu...

. After Bohemond was released, he was defeated by the Seljuks at the Battle of Harran

Battle of Harran

The Battle of Harran took place on May 7, 1104 between the Crusader states of the Principality of Antioch and the County of Edessa, and the Seljuk Turks. It was the first major battle against the newfound Crusader states in the aftermath of the First Crusade marking a key turning point against...

in 1104; this defeat led to renewed pressure on Antioch from both the Seljuks and the Byzantines. Bohemond left Tancred in control of Antioch and returned in the West, touring Italy and France for reinforcements. He won the backing of Pope Paschal II

Pope Paschal II

Pope Paschal II , born Ranierius, was Pope from August 13, 1099, until his death. A monk of the Cluniac order, he was created cardinal priest of the Titulus S...

and the support of the French King Philip I

Philip I of France

Philip I , called the Amorous, was King of France from 1060 to his death. His reign, like that of most of the early Direct Capetians, was extraordinarily long for the time...

, whose daughter he married. It is unclear whether his expedition qualified as a crusade.

Bohemond's Norman

Normans

The Normans were the people who gave their name to Normandy, a region in northern France. They were descended from Norse Viking conquerors of the territory and the native population of Frankish and Gallo-Roman stock...

relatives in Sicily

Sicily

Sicily is a region of Italy, and is the largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Along with the surrounding minor islands, it constitutes an autonomous region of Italy, the Regione Autonoma Siciliana Sicily has a rich and unique culture, especially with regard to the arts, music, literature,...

had been in conflict with the Byzantine Empire for over 30 years; his father Robert Guiscard

Robert Guiscard

Robert d'Hauteville, known as Guiscard, Duke of Apulia and Calabria, from Latin Viscardus and Old French Viscart, often rendered the Resourceful, the Cunning, the Wily, the Fox, or the Weasel was a Norman adventurer conspicuous in the conquest of southern Italy and Sicily...

was one of the Empire's most formidable enemies. While Bohemond was away, Alexios sent an army to reoccupy Antioch and the cities of Cilicia

Cilicia

In antiquity, Cilicia was the south coastal region of Asia Minor, south of the central Anatolian plateau. It existed as a political entity from Hittite times into the Byzantine empire...

. In 1107, having organized a new army for his planned crusade against the Muslims in Syria, Bohemond instead launched into open warfare against Alexios, crossing the Adriatic to besiege Dyrrhachium

Durrës

Durrës is the second largest city of Albania located on the central Albanian coast, about west of the capital Tirana. It is one of the most ancient and economically important cities of Albania. Durres is situated at one of the narrower points of the Adriatic Sea, opposite the Italian ports of Bari...

, the westernmost city of the Empire. Like his father however, Bohemond was unable to make any significant advances into the Empire's interior; Alexios avoided a pitched battle and Bohemond's siege failed, partly due to a plague among his army. Bohemond soon found himself in an impossible position, isolated in front of Dyrrhachium: his escape by sea was cut off by the Venetians

Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice or Venetian Republic was a state originating from the city of Venice in Northeastern Italy. It existed for over a millennium, from the late 7th century until 1797. It was formally known as the Most Serene Republic of Venice and is often referred to as La Serenissima, in...

, and Paschal II withdrew his support.

Settlements

Anna Komnene

Anna Komnene, Latinized as Comnena was a Greek princess and scholar and the daughter of Emperor Alexios I Komnenos of Byzantium and Irene Doukaina...

:

- Bohemond agreed to become a vassal of the emperor, and also of Alexios' son and heir John;

- He agreed to help defend the empire, wherever and whenever he was required to do so, and agreed to an annual payment of 200 talentsTalent (weight)The "talent" was one of several ancient units of mass, as well as corresponding units of value equivalent to these masses of a precious metal. It was approximately the mass of water required to fill an amphora. A Greek, or Attic talent, was , a Roman talent was , an Egyptian talent was , and a...

in return for this service; - He was given the title of sebastosSebastosSebastos was an honorific used by the ancient Greeks to render the Roman imperial title of Augustus. From the late 11th century on, during the Komnenian period, it and variants derived from it formed the basis of a new system of court titles for the Byzantine Empire. The female form of the title...

, as well as douxDuxDux is Latin for leader and later for Duke and its variant forms ....

(duke) of Antioch; - He was granted as imperial fiefs Antioch and AleppoAleppoAleppo is the largest city in Syria and the capital of Aleppo Governorate, the most populous Syrian governorate. With an official population of 2,301,570 , expanding to over 2.5 million in the metropolitan area, it is also one of the largest cities in the Levant...

(the latter of which neither the Crusaders nor the Byzantines controlled, but it was understood that Bohemond should try to conquer it); - He agreed to return LaodiceaLatakiaLatakia, or Latakiyah , is the principal port city of Syria, as well as the capital of the Latakia Governorate. In addition to serving as a port, the city is a manufacturing center for surrounding agricultural towns and villages...

and other Cilician territories to Alexios; - He agreed to let Alexios appoint a Greek patriarch "among the disciples of the great church of Constantinople" (The restoration of the Greek Patriarch marked the acceptance of submission to the empire, but posed canonical questionsCanon lawCanon law is the body of laws & regulations made or adopted by ecclesiastical authority, for the government of the Christian organization and its members. It is the internal ecclesiastical law governing the Catholic Church , the Eastern and Oriental Orthodox churches, and the Anglican Communion of...

, which were difficult to resolve).

The terms were negotiated according to Bohemond's western understanding, so that he saw himself as a feudal

Feudalism

Feudalism was a set of legal and military customs in medieval Europe that flourished between the 9th and 15th centuries, which, broadly defined, was a system for ordering society around relationships derived from the holding of land in exchange for service or labour.Although derived from the...

vassal of Alexios, a "liege man" (homo ligius or ) with all the obligations this implied, as customary in the West: he was obliged to bring military assistance to the Emperor, except in wars in which he was involved, and to serve him against all his enemies, in Europe and in Asia.

Anna Komnene described the proceedings with very repetitive details, with Bohemond frequently pointing out his own mistakes and praising the benevolence of Alexios and the Empire; the proceedings must have been rather humiliating for Bohemond. On the other hand, Anna's work was meant to praise her father and the terms of the treaty may not be entirely accurate.

| "I swear to thee, our most powerful and holy Emperor, the Lord Alexios Komnenos, and to thy fellow-Emperor, the much-desired Lord John Porphyrogenitos that I will observe all the conditions to which I have agreed and spoken by my mouth and will keep them inviolate for all time and the things that are for the good of your Empire I care for now and will for ever care for and I will never harbor even the slightest thought of hatred or treachery towards you [...] and everything that is for the benefit and honor of the Roman rule that I will both think of and execute. Thus may I enjoy the help of God, and of the Cross and of the holy Gospels." |

| Oath sworn by Bohemond, concluding the Treaty of Devol, as recorded by Anna Komnene Anna Komnene Anna Komnene, Latinized as Comnena was a Greek princess and scholar and the daughter of Emperor Alexios I Komnenos of Byzantium and Irene Doukaina... |

The oral agreement was written down in two copies, one given to Alexios, and the other given to Bohemond. According to Anna, the witnesses from Bohemond's camp who signed his copy of the treaty were Maurus, bishop of Amalfi and papal legate

Papal legate

A papal legate – from the Latin, authentic Roman title Legatus – is a personal representative of the pope to foreign nations, or to some part of the Catholic Church. He is empowered on matters of Catholic Faith and for the settlement of ecclesiastical matters....

, Renard, bishop of Tarentum, and the minor clergy accompanying them; the abbot of the monastery of St. Andrew in Brindisi

Brindisi

Brindisi is a city in the Apulia region of Italy, the capital of the province of Brindisi, off the coast of the Adriatic Sea.Historically, the city has played an important role in commerce and culture, due to its position on the Italian Peninsula and its natural port on the Adriatic Sea. The city...

, along with two of his monks; and a number of unnamed "pilgrims" (probably soldiers in Bohemond's army). From Alexios' imperial court, the treaty was witnessed by the sebastos Marinos of Naples

Naples

Naples is a city in Southern Italy, situated on the country's west coast by the Gulf of Naples. Lying between two notable volcanic regions, Mount Vesuvius and the Phlegraean Fields, it is the capital of the region of Campania and of the province of Naples...

, Roger son of Dagobert

Roger (son of Dagobert)

Roger, the son of Dagobert , was a Norman magnate who deserted to the Byzantine Empire where he entered the service of Emperor Alexios I Komnenos . He is the founder of the noble Byzantine family of Rogerios.- Life :...

, Peter Aliphas, William of Gand, Richard of the Principate, Geoffrey of Mailli, Hubert son of Raoul

Raoul (Byzantine family)

The Raoul was a Byzantine aristocratic family of Norman origin, prominent during the Palaiologan period. From the 14th century on, they were also known as Ralles . The feminine form of the name was Raoulaina ....

, Paul the Roman, the ambassadors Peres and Simon from Hungary, and the ambassadors Basil the Eunuch and Constantine. Many of Alexios' witnesses were themselves Westerners, who held high positions in the Byzantine army

Byzantine army

The Byzantine army was the primary military body of the Byzantine armed forces, serving alongside the Byzantine navy. A direct descendant of the Roman army, the Byzantine army maintained a similar level of discipline, strategic prowess and organization...

and at the imperial court; Basil and Constantine were ambassadors in the service of Bohemond's relatives in Sicily

Sicily

Sicily is a region of Italy, and is the largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Along with the surrounding minor islands, it constitutes an autonomous region of Italy, the Regione Autonoma Siciliana Sicily has a rich and unique culture, especially with regard to the arts, music, literature,...

.

Neither copy survives. It may have been written in Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

, Greek

Greek language

Greek is an independent branch of the Indo-European family of languages. Native to the southern Balkans, it has the longest documented history of any Indo-European language, spanning 34 centuries of written records. Its writing system has been the Greek alphabet for the majority of its history;...

, or both. Both languages are equally likely given the number of westerners present, many of whom would have known Latin. It is not clear how far Bohemond's concessions were known across Latin Europe

Latin Europe

Latin Europe is a loose term for the region of Europe with an especially strong Latin cultural heritage inherited from the Roman Empire.-Application:...

as only a few chroniclers mention the treaty at all; Fulcher of Chartres

Fulcher of Chartres

Fulcher of Chartres was a chronicler of the First Crusade. He wrote in Latin.- Life :His appointment as chaplain of Baldwin of Boulogne in 1097 suggests that he had been trained as a priest, most likely at the school in Chartres...

simply says

that Bohemond and Alexios were reconciled.

Analysis

Bohemond's lands were to include St Simeon and the coast, the towns of Baghras and Artah, and the Latin possessions in the Jebel as-Summaq. Latakia

Latakia

Latakia, or Latakiyah , is the principal port city of Syria, as well as the capital of the Latakia Governorate. In addition to serving as a port, the city is a manufacturing center for surrounding agricultural towns and villages...

and Cilicia

Cilicia

In antiquity, Cilicia was the south coastal region of Asia Minor, south of the central Anatolian plateau. It existed as a political entity from Hittite times into the Byzantine empire...

, however, were to revert to direct Byzantine rule. As Thomas Asbridge

Thomas Asbridge

Thomas Asbridge is a University of London medieval history scholar. He is the author of The First Crusade: A New History, a book which describes the background, events, and consequences of the First Crusade, "The Crusades: The War for the Holy Land", a book providing a view on the crusading...

points out, much of what the Emperor granted to Bohemond (including Aleppo itself) was still in Muslim hands (e.g. neither Bohemond nor Alexios controlled Edessa, although at the time Tancred was regent there as well as in Antioch), which contradicts Lilie's assessment that Bohemond did well out of the Treaty. René Grousset

René Grousset

René Grousset was a French historian, curator of both the Cernuschi and Guimet Museums in Paris, and a member of the prestigious Académie française...

calls the Treaty a "Diktat

Diktat

A diktat is a harsh penalty or settlement imposed upon a defeated party by the victor, or a dogmatic decree. Historically, it was particularly used in Germany to refer to the Treaty of Versailles....

", but Jean Richard underscores that the rules of feudal law to which Bohemond had to submit "were in no way humiliating." According to John W. Birkenmeier, the Treaty marked the point at which Alexios had developed a new army

Komnenian army

The Komnenian Byzantine army or Komnenian army was the force established by Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos during the late 11th/early 12th century, and perfected by his successors John II Komnenos and Manuel I Komnenos during the 12th century. Alexios constructed a new army from the ground...

, and new tactical doctrines with which to use it, but it was not a Byzantine political success; "it traded Bohemond's freedom for a titular overlordship of Southern Italy that could never be effective, and for an occupation of Antioch that could never be carried out."

The terms of the Treaty have been interpreted in various ways. According to Paul Magdalino and Ralph-Johannes Lilie, "the Treaty as reproduced by Anna Komnene shows an astonishing familiarity with western feudal custom; whether it was drafted by a Greek or by a Latin in imperial service, it had a sensitive regard for the western view of the status quo

Status quo

Statu quo, a commonly used form of the original Latin "statu quo" – literally "the state in which" – is a Latin term meaning the current or existing state of affairs. To maintain the status quo is to keep the things the way they presently are...

in the East Mediterranean." So too did the diplomatic initiatives Alexios undertook, in order to enforce the Treaty on Tancred (such as the treaty he concluded with Pisa in 1110–1111, and the negotiations for Church union with Pascal II in 1112). In contrast, Asbridge has recently argued that the Treaty derived from Greek as well as western precedents, and that Alexios wished to regard Antioch as falling under the umbrella of pronoia

Pronoia

Pronoia refers to a system of land grants in the Byzantine Empire.-The Early Pronoia System:...

arrangements.

Aftermath

Right of conquest

The right of conquest is the right of a conqueror to territory taken by force of arms. It was traditionally a principle of international law which has in modern times gradually given way until its proscription after the Second World War when the crime of war of aggression was first codified in the...

. He saw no reason to hand it over to someone who had not been involved in the Crusade, and had indeed actively worked against it (as the Crusaders believed). The Crusaders seem to have felt Alexios had tricked Bohemond into giving him Antioch; they already believed Alexios was devious and untrustworthy and this may have confirmed their beliefs. The treaty referred to Tancred as the illegal holder of Antioch, and Alexios had expected Bohemond to expel him or somehow control him. Tancred also did not allow a Greek Patriarch to enter the city; instead, Greek Patriarchs were appointed in Constantinople and nominally held power there.

The question of the status of Antioch and the adjacent Cilician cities troubled the Empire for many years afterwards. Although the Treaty of Devol never came into effect, it provided the legal basis for Byzantine negotiations with the crusaders for the next thirty years, and for imperial claims to Antioch during the reigns of John II

John II Komnenos

John II Komnenos was Byzantine Emperor from 1118 to 1143. Also known as Kaloïōannēs , he was the eldest son of Emperor Alexios I Komnenos and Irene Doukaina...

and Manuel I

Manuel I Komnenos

Manuel I Komnenos was a Byzantine Emperor of the 12th century who reigned over a crucial turning point in the history of Byzantium and the Mediterranean....

. Therefore, John II attempted to impose his authority, traveling to Antioch himself in 1137 with his army and besieging the city. The citizens of Antioch tried to negotiate, but John demanded the unconditional surrender of the city. After asking the permission of the King of Jerusalem, Fulk, which he received, Raymond

Raymond of Antioch

Raymond of Poitiers was Prince of Antioch 1136–1149. He was the younger son of William IX, Duke of Aquitaine and his wife Philippa, Countess of Toulouse, born in the very year that his father the Duke began his infamous liaison with Dangereuse de Chatelherault.-Assumes control:Following the...

, the Prince of Antioch, agreed to surrender the city to John. The agreement, by which Raymond swore homage to John, was explicitly based on the Treaty of Devol, but went beyond it: Raymond, who was recognized as an imperial vassal for Antioch, promised the Emperor free entry to Antioch, and undertook to hand over the city in return for investiture with Aleppo, Shaizar

Shaizar

Shaizar, Shayzar or Saijar was a medieval town and fortress in Syria, ruled by the Banu Munqidh dynasty, which played an important part in the Christian and Muslim politics of the crusades.- Early history :...

, Homs

Homs

Homs , previously known as Emesa , is a city in western Syria and the capital of the Homs Governorate. It is above sea level and is located north of Damascus...

and Hama

Hama

Hama is a city on the banks of the Orontes River in west-central Syria north of Damascus. It is the provincial capital of the Hama Governorate. Hama is the fourth-largest city in Syria—behind Aleppo, Damascus, and Homs—with a population of 696,863...

as soon as these were conquered from the Muslims. Then, Raymond would rule the new conquests and Antioch would revert to direct imperial rule. The campaign finally failed, however, partly because Raymond and Joscelin II, Count of Edessa

Joscelin II, Count of Edessa

Joscelin II of Edessa was the fourth and last ruling count of Edessa.The young Joscelin was taken prisoner at the Battle of Azaz in 1125, but was ransomed by Baldwin II, king of Jerusalem. In 1131, his father Joscelin I was wounded in battle with the Danishmends, and Edessa passed to Joscelin II...

, who had been obliged to join John as his vassals, did not pull their weight. When, on their return to Antioch, John insisted on taking possession of the city, the two princes organized a riot. John found himself besieged in the city, and was forced to leave in 1138, recalled to Constantinople. He diplomatically accepted Raymond's and Joscelin's insistence that they had nothing to do with the rebellion. John repeated his operation in 1142, but he unexpectedly died, and the Byzantine army retired.

It was not until 1158, during the reign of Manuel I, that Antioch truly became a vassal of the empire, after Manuel forced Prince Raynald of Châtillon

Raynald of Chatillon

Raynald of Châtillon was a knight who served in the Second Crusade and remained in the Holy Land after its defeat...

to swear fealty

Fealty

An oath of fealty, from the Latin fidelitas , is a pledge of allegiance of one person to another. Typically the oath is made upon a religious object such as a Bible or saint's relic, often contained within an altar, thus binding the oath-taker before God.In medieval Europe, fealty was sworn between...

to him in punishment for Raynald's attack on Byzantine Cyprus

Cyprus

Cyprus , officially the Republic of Cyprus , is a Eurasian island country, member of the European Union, in the Eastern Mediterranean, east of Greece, south of Turkey, west of Syria and north of Egypt. It is the third largest island in the Mediterranean Sea.The earliest known human activity on the...

. The Greek Patriarch was restored, and ruled simultaneously with the Latin Patriarch. Antioch, weakened by powerless regents after Raynald's capture by the Muslims in 1160, remained a Byzantine vassal state until 1182 when internal divisions following Manuel's death in 1180 hindered the Empire's ability to enforce its claim.

In the Balkan frontier, the Treaty of Devol marked the end of the Norman threat to the southern Adriatic littoral during Alexios' reign and later; the efficacy of the frontier defenses deterred any further invasions through Dyrrachium for most of the 12th century.

Further reading

- Thomas S. Asbridge, The Creation of the Principality of Antioch, 1098–1130. The Boydell Press, 2000.

- Jonathan Harris, Byzantium and the Crusades. Hambledon and London, 2003.

- Ralph-Johannes Lilie, Byzantium and the Crusader States, 1096–1204. Trans. J.C. Morris and J.C. Ridings. Clarendon Press, 1993.

- Kenneth M. Setton, ed., A History of the Crusades, Vols. II and V. Madison, 1969–1989.