UK General Strike of 1926

Encyclopedia

General strike

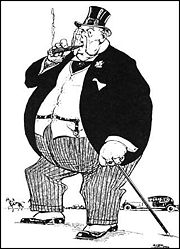

A general strike is a strike action by a critical mass of the labour force in a city, region, or country. While a general strike can be for political goals, economic goals, or both, it tends to gain its momentum from the ideological or class sympathies of the participants...

that lasted nine days, from 4 May 1926 to 13 May 1926. It was called by the general council of the Trades Union Congress

Trades Union Congress

The Trades Union Congress is a national trade union centre, a federation of trade unions in the United Kingdom, representing the majority of trade unions...

(TUC) in an unsuccessful attempt to force the British government to act to prevent wage reduction and worsening conditions for coal miners

Coal mining

The goal of coal mining is to obtain coal from the ground. Coal is valued for its energy content, and since the 1880s has been widely used to generate electricity. Steel and cement industries use coal as a fuel for extraction of iron from iron ore and for cement production. In the United States,...

.

Causes of the 1926 conflict

- The First World War: The heavy domestic use of coal in the war meant that rich seams were depleted. Britain exported less coal in the war than it would have done in peacetime, allowing other countries to fill the gap. The United StatesUnited StatesThe United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, PolandPolandPoland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

and GermanyGermanyGermany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

and their strong coal industries benefited in particular. - Productivity, which was at its lowest ebb. Output per man had fallen to just 199 tonnes in 1920–4, from 247 tonnes in the four years before the war, and a peak of 310 tons in the early 1880s. Total coal output had been falling since 1914.

- The fall in prices resulting from the 1925 Dawes PlanDawes PlanThe Dawes Plan was an attempt in 1924, following World War I for the Triple Entente to collect war reparations debt from Germany...

that, among other things, allowed Germany to re-enter the international coal market by exporting "free coal" to FranceFranceThe French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

and ItalyItalyItaly , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

as part of their reparations for the First World War. - The reintroduction of the gold standardGold standardThe gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is a fixed mass of gold. There are distinct kinds of gold standard...

in 1925 by Winston ChurchillWinston ChurchillSir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

: this made the British pound too strong for effective exporting to take place from Britain, and also (because of the economic processes involved in maintaining a strong currency) raised interest rateInterest rateAn interest rate is the rate at which interest is paid by a borrower for the use of money that they borrow from a lender. For example, a small company borrows capital from a bank to buy new assets for their business, and in return the lender receives interest at a predetermined interest rate for...

s, hurting all businesses. - Mine owners wanted to normalise profits even during times of economic instability — which often took the form of wage reductions for miners in their employ. Coupled with the prospect of longer working hoursWorking timeWorking time is the period of time that an individual spends at paid occupational labor. Unpaid labors such as personal housework are not considered part of the working week...

, the industry was thrown into disarray.

Mine owners therefore announced that their intention was to reduce miners' wages, the MFGB rejected the terms: "Not a penny off the pay, not a minute on the day." and the TUC responded to this news by promising to support the miners in their dispute. The Conservative government

Conservative Party (UK)

The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

under Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, KG, PC was a British Conservative politician, who dominated the government in his country between the two world wars...

decided to intervene, declaring that they would provide a nine-month subsidy to maintain the miners' wages and that a Royal Commission

Royal Commission

In Commonwealth realms and other monarchies a Royal Commission is a major ad-hoc formal public inquiry into a defined issue. They have been held in various countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and Saudi Arabia...

under the chairmanship of Sir Herbert Samuel

Herbert Samuel, 1st Viscount Samuel

Herbert Louis Samuel, 1st Viscount Samuel GCB OM GBE PC was a British politician and diplomat.-Early years:...

would look into the problems of the mining industry.

This decision became known as "Red Friday" because it was seen as a victory for working-class solidarity and Socialism

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system characterized by social ownership of the means of production and cooperative management of the economy; or a political philosophy advocating such a system. "Social ownership" may refer to any one of, or a combination of, the following: cooperative enterprises,...

. In practice, the subsidy gave the mine owners and the government time to prepare for a major labour dispute. Herbert Smith (a leader of the Miners' Federation of Great Britain) said of this event: "We have no need to glorify about victory. It is only an armistice."

The Samuel Commission published a report on March 10, 1926 recommending that in the future, national agreements, the nationalisation

Nationalization

Nationalisation, also spelled nationalization, is the process of taking an industry or assets into government ownership by a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to private assets, but may also mean assets owned by lower levels of government, such as municipalities, being...

of royalties and sweeping reorganisation and improvement should be considered for the mining industry. It also recommended a reduction by 13.5% of miners' wages along with the withdrawal of the government subsidy. Two weeks later, the prime minister announced that the government would accept the report provided other parties also did. A previous royal commission, the Sankey Commission, had recommended nationalisation a few years earlier to deal with the problems of productivity and profitability in the industry, but Lloyd George

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor OM, PC was a British Liberal politician and statesman...

, then prime minister, had rejected its report.

After the Samuel Commission's report, the mine owners declared that, on penalty of lock out from 1 May, miners would have to accept new terms of employment that included lengthening the work day and reducing wages between 10% and 25%, depending on various factors. The Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB) refused the wage reduction and regional negotiation.

The general strike, May 1926

General strike

A general strike is a strike action by a critical mass of the labour force in a city, region, or country. While a general strike can be for political goals, economic goals, or both, it tends to gain its momentum from the ideological or class sympathies of the participants...

"in defence of miners' wages and hours" was to begin on 3 May.

The leaders of the Labour Party were terrified by the revolutionary elements within the union movement or at least worried about the damage association with them would do to their newly established reputation as a more moderate party of government and were unhappy about the proposed general strike. During the next two days, frantic efforts were made to reach an agreement with the government and the mine owners. However, these efforts failed, mainly owing to an eleventh-hour decision by printers of the Daily Mail

Daily Mail

The Daily Mail is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper owned by the Daily Mail and General Trust. First published in 1896 by Lord Northcliffe, it is the United Kingdom's second biggest-selling daily newspaper after The Sun. Its sister paper The Mail on Sunday was launched in 1982...

to refuse to print an editorial ("For King and Country") condemning the general strike. They objected to the following passage: "A general strike is not an industrial dispute. It is a revolutionary move which can only succeed by destroying the government and subverting the rights and liberties of the people". When Baldwin heard of this, he called off the negotiations with the TUC, saying that the printers' action was interfering with the liberty of the press.

King George V

George V of the United Kingdom

George V was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 through the First World War until his death in 1936....

took exception to suggestions that the strikers were 'revolutionaries' saying, "Try living on their wages before you judge them."

The TUC feared that an all-out general strike would bring revolutionary elements to the fore and limited the participants to railwaymen

National Union of Railwaymen

The National Union of Railwaymen was a trade union of railway workers in the United Kingdom. It an industrial union founded in 1913 by the merger of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants , the United Pointsmen and Signalmen's Society and the General Railway Workers' Union .The NUR...

, transport workers

National Transport Workers' Federation

The National Transport Workers' Federation was an association of British trade unions. It was formed in 1910 to co-ordinate the activities of various organisations catering for dockers, seamen, tramwaymen and road transport workers...

, printer

Printer (publisher)

In publishing, printers are both companies providing printing services and individuals who directly operate printing presses. With the invention of the moveable type printing press by Johannes Gutenberg around 1450, printing—and printers—proliferated throughout Europe.Today, printers are found...

s, dockers

Transport and General Workers' Union

The Transport and General Workers' Union, also known as the TGWU and the T&G, was one of the largest general trade unions in the United Kingdom and Ireland - where it was known as the Amalgamated Transport and General Workers' Union - with 900,000 members...

, ironworker

Ironworker

Ironworker is a class of machines that can shear, notch, and punch holes in steel plate. Ironworkers generate force using mechanical advantage or hydraulic systems. Modern systems use hydraulic rams powered by a heavy alternating current electric motor. High strength carbon steel blades and dies...

s and steelworkers, as these were regarded as pivotal in the dispute.

The government had prepared for the strike over the nine months in which it had provided a subsidy, creating organizations such as the Organization for the maintenance of supplies, and did whatever it could to keep the country moving. It rallied support by emphasizing the revolutionary nature of the strikers. The armed forces and volunteer workers helped maintain basic services. The government's Emergency Powers Act

Emergency Powers Act 1920

The Emergency Powers Act 1920 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that gave the Sovereign power, in certain circumstances, to declare a state of emergency by proclamation...

—an act to maintain essential supplies—had been passed in 1920.

On 4 May 1926, the number of strikers was about 1.5 - 1.75 million. There were strikers "from John o' Groats to Land's End

Land's End to John o' Groats

Land's End to John o' Groats is the traversal of the whole length of the island of Great Britain between two extremities; in the southwest and northeast. The traditional distance by road is and takes most cyclists ten to fourteen days; the record for running the route is nine days. Off-road...

". Workers' reaction to the strike call was immediate and overwhelming, and surprised both the government and the TUC; the latter not being in control of the strike. On this first day, there were no major initiatives and no dramatic events, except for the nation's transport being at a standstill.

On 5 May 1926, both sides gave their views. Churchill (at that time Chancellor of the Exchequer

Chancellor of the Exchequer

The Chancellor of the Exchequer is the title held by the British Cabinet minister who is responsible for all economic and financial matters. Often simply called the Chancellor, the office-holder controls HM Treasury and plays a role akin to the posts of Minister of Finance or Secretary of the...

) commented as editor of the government newspaper British Gazette

British Gazette

The British Gazette was a short-lived British newspaper published by the Government during the General Strike of 1926.One of the first groups of workers called out by the Trades Union Congress when the general strike began on 3 May were the printers, and consequently most newspapers appeared only...

: "I do not agree that the TUC have as much right as the Government to publish their side of the case and to exhort their followers to continue action. It is a very much more difficult task to feed the nation than it is to wreck it". In the British Worker

British Worker

The British Worker was a newspaper produced by the TUC General Council for the duration of the 1926 United Kingdom General Strike. The first of eleven issues was printed on 5 May and publication stopped on 17 May after the official cessation of the strike...

, the TUC's newspaper: "We are not making war on the people. We are anxious that the ordinary members of the public shall not be penalized for the unpatriotic conduct of the mine owners and the government". In the meantime, the government put in place a "militia

Militia

The term militia is commonly used today to refer to a military force composed of ordinary citizens to provide defense, emergency law enforcement, or paramilitary service, in times of emergency without being paid a regular salary or committed to a fixed term of service. It is a polyseme with...

" of special constable

Special constable

A Special Constable is a law enforcement officer who is not a regular member of a police force. Some like the Royal Canadian Mounted Police carry the same law enforcement powers as regular members, but are employed in specific roles, such as explosive disposal technicians, court security, campus...

s, called the Organisation for the Maintenance of Supplies

Organisation for the Maintenance of Supplies

Organisation for the Maintenance of Supplies was a British right-wing movement established in 1925 to provide volunteers in the event of a general strike...

(OMS). They were volunteers to maintain order in the street. A special constable said: "It was not difficult to understand the strikers' attitude toward us. After a few days I found my sympathy with them rather than with the employers. For one thing, I had never realized the appalling poverty which existed. If I had been aware of all the facts, I should not have joined up as a special constable". It was decided that Fascists would not be allowed to enlist in the OMS without first giving up their political beliefs, as the government feared a right-wing backlash, so the fascists formed Q Division under Rotha Lintorn-Orman

Rotha Lintorn-Orman

-Early life:Born as Rotha Beryl Orman in Kensington London, she was the daughter of Charles Edward Orman, a Major from the Essex Regiment, and her maternal grandfather was Field Marshal Sir John Lintorn Arabin Simmons...

to combat the strikers.

On 6 May 1926, there was a change of atmosphere. Baldwin said: "The general strike is a challenge to the parliament and is the road to anarchy

Anarchy

Anarchy , has more than one colloquial definition. In the United States, the term "anarchy" typically is meant to refer to a society which lacks publicly recognized government or violently enforced political authority...

". The government newspaper British Gazette

British Gazette

The British Gazette was a short-lived British newspaper published by the Government during the General Strike of 1926.One of the first groups of workers called out by the Trades Union Congress when the general strike began on 3 May were the printers, and consequently most newspapers appeared only...

suggested that means of transport began to improve with volunteers and blackleg

Blackleg

Blackleg may refer to:* Strikebreaker* Card sharp* Appalousa tribe* Operation Blackleg, dive operation on warship HMS Coventry * Blackleg , in sheep and cattle* Scurvy, deficiency in primates & some other animals...

workers, stating on the front page that there were '200 buses on the streets'. These were, however, figures of propaganda as there were in fact only 86 buses running.

On 7 May 1926, the TUC met with Sir Herbert Samuel

Herbert Samuel, 1st Viscount Samuel

Herbert Louis Samuel, 1st Viscount Samuel GCB OM GBE PC was a British politician and diplomat.-Early years:...

and worked out a set of proposals designed to end the dispute. The Miners' Federation rejected the proposals. The British Worker was increasingly difficult to operate because Churchill had requisitioned the bulk of the supply of the paper's newsprint so reduced its size from eight pages to four. In the meantime, the government took action to protect the men who decided to return to work.

On 8 May 1926, there was a dramatic moment on the London Docks. Lorries were protected by the army. They broke the picket line and transported food to Hyde Park. This episode showed that the government was in greater control of the situation. It was also a measure of Baldwin's rationalism in place of Churchill's more reactionary stance. Churchill had wanted, in a move that would have proved unnecessarily antagonistic to the strikers, to arm the soldiers. Baldwin, however, had insisted they not be armed.

On 11 May 1926, the Flying Scotsman

Flying Scotsman (train)

The Flying Scotsman is an express passenger train service that has been running between London and Edinburgh—the capitals of England and Scotland respectively—since 1862...

was derailed by strikers near Newcastle

Newcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne is a city and metropolitan borough of Tyne and Wear, in North East England. Historically a part of Northumberland, it is situated on the north bank of the River Tyne...

.

The British Worker, alarmed at the fears of the General Council of the TUC that there was to be a mass drift back to work, claimed: "The number of strikers has not diminished; it is increasing. There are more workers out today than there have been at any moment since the strike began."

However, the National Sailors' and Firemen's Union applied for an injunction in the Chancery Division of the High Court, to enjoin the General-Secretary of its Tower Hill

Tower Hill

Tower Hill is an elevated spot northwest of the Tower of London, just outside the limits of the City of London, in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. Formerly it was part of the Tower Liberty under the direct administrative control of Tower...

branch from calling its members out on strike. Mr Justice Astbury

John Meir Astbury

Sir John Meir Astbury was a British judge and politician. Astbury was born at Grove House, Broughton near Manchester, the son of Frederick James Astbury and Margaret née Munn...

granted the injunction, ruling that no trade dispute could exist between the TUC and "the government of the nation" and that, save for strike in the coal industry, the general strike was not protected by Trade Disputes Act 1906

Trade Disputes Act 1906

The Trade Disputes Act 1906 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed under the Liberal government of Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman...

. In addition, he ruled that the strike in the plaintiff union had been called in contravention of its own rules. As a result, the unions involved became liable at common law for incitement to breach of contract, and faced potential sequestration

Sequestration (law)

Sequestration is the act of removing, separating, or seizing anything from the possession of its owner under process of law for the benefit of creditors or the state.-Etymology:...

of their assets by employers.

On 12 May 1926, the TUC General Council visited 10 Downing Street

10 Downing Street

10 Downing Street, colloquially known in the United Kingdom as "Number 10", is the headquarters of Her Majesty's Government and the official residence and office of the First Lord of the Treasury, who is now always the Prime Minister....

to announce their decision to call off the strike, provided that the proposals worked out by the Samuel Commission were adhered to and that the Government offered a guarantee that there would be no victimization of strikers. The Government stated that it had "no power to compel employers to take back every man who had been on strike." Thus the TUC agreed to end the dispute without such an agreement.

Aftermath of the conflict

The miners maintained resistance for a few months before being forced by their own economic needs to return to the mines. By the end of November most miners were back at work. However, many remained unemployed for many years. Those that were employed were forced to accept longer hours, lower wages, and district wage agreements. The strikers felt as though they had achieved nothing.The effect on the British coal-mining industry was profound. By the late 1930s, employment in mining had fallen by more than one-third from its pre-strike peak of 1.2 million miners, but productivity had rebounded from under 200 tons produced per miner to over 300 tons by the outbreak of the Second World War.

The Trade Disputes and Trade Unions Act of 1927, among other things, forbade sympathetic strikes

Sympathy strike

Secondary action is industrial action by a trade union in support of a strike initiated by workers in another, separate enterprise...

and mass picketing.

The 1926 general strike in popular culture

- The poet Hugh MacDiarmidHugh MacDiarmidHugh MacDiarmid is the pen name of Christopher Murray Grieve , a significant Scottish poet of the 20th century. He was instrumental in creating a Scottish version of modernism and was a leading light in the Scottish Renaissance of the 20th century...

composed an ultimately pessimistic lyrical response to the general strike, which he incorporated into his long modernist poem of the same year, "A Drunk Man Looks at the ThistleA Drunk Man Looks at the ThistleA Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle is a long poem by Hugh MacDiarmid written in Scots and published in 1926. It is composed as a form of monologue with influences from stream of consciousness genres of writing...

". His imagisticImagismImagism was a movement in early 20th-century Anglo-American poetry that favored precision of imagery and clear, sharp language. The Imagists rejected the sentiment and discursiveness typical of much Romantic and Victorian poetry. This was in contrast to their contemporaries, the Georgian poets,...

depiction of how events unfolded occurs in the extended passage beginning "I saw a rose come loupinJumpingJumping or leaping is a form of locomotion or movement in which an organism or non-living mechanical system propels itself through the air along a ballistic trajectory...

oot..." (line 1119). - The strike functions as the 'endpiece' of the satirical novel, The Apes of GodThe Apes of GodThe Apes of God is a 1930 novel by the British artist and writer Wyndham Lewis. It is a satire of London's contemporary literary and artistic scene....

, by Wyndham LewisWyndham LewisPercy Wyndham Lewis was an English painter and author . He was a co-founder of the Vorticist movement in art, and edited the literary magazine of the Vorticists, BLAST...

. In that novel, the half-hearted nature of the strike, and its eventual collapse, represents the political and moral stagnation of 1920s Britain. - The failure of the strike inspired Idris DaviesIdris DaviesIdris Davies was a Welsh poet. He was born in Rhymney, near Caerphilly in South Wales, the Welsh-speaking son of colliery chief winderman Evan Davies and his wife Elizabeth Ann. Davies became a poet, originally writing in Welsh, but later writing exclusively in English...

to write "Bells of RhymneyRhymneyRhymney is a town and a community located in the county borough of Caerphilly in south-east Wales, within the historic boundaries of Monmouthshire. Along with the villages of Pontlottyn, Fochriw, Abertysswg, Deri and New Tredegar, Rhymney is designated as the 'Upper Rhymney Valley' by the local...

" (published 1938), which Pete Seeger made into the song "The Bells of RhymneyThe Bells of Rhymney"The Bells of Rhymney" is a song first recorded by folk singer Pete Seeger, using words written by Welsh poet Idris Davies. The lyrics to the song were drawn from part of Davies' poetic work Gwalia Deserta, which was first published in 1938...

" (recorded 1958). - In the 1945 novel, Brideshead RevisitedBrideshead RevisitedBrideshead Revisited, The Sacred & Profane Memories of Captain Charles Ryder is a novel by English writer Evelyn Waugh, first published in 1945. Waugh wrote that the novel "deals with what is theologically termed 'the operation of Grace', that is to say, the unmerited and unilateral act of love by...

, the main character, Charles Ryder, returns from France to London to fight against the workers on strike. - The 1967 BBC television adaptation of John GalsworthyJohn GalsworthyJohn Galsworthy OM was an English novelist and playwright. Notable works include The Forsyte Saga and its sequels, A Modern Comedy and End of the Chapter...

's novel The Forsyte SagaThe Forsyte SagaThe Forsyte Saga is a series of three novels and two interludes published between 1906 and 1921 by John Galsworthy. They chronicle the vicissitudes of the leading members of an upper-middle-class British family, similar to Galsworthy's own...

and its sequel trilogy, A Modern Comedy alludes to the general strike. - The KinksThe KinksThe Kinks were an English rock band formed in Muswell Hill, North London, by brothers Ray and Dave Davies in 1964. Categorised in the United States as a British Invasion band, The Kinks are recognised as one of the most important and influential rock acts of the era. Their music was influenced by a...

' 1974 album, Preservation Act 2Preservation Act 2Preservation Act 2 is a 1974 concept album by British rock band The Kinks. It was not well-received by critics and sold poorly , though the live performances of the material were much better received...

, features a song called "Nobody Gives", which makes several references to the general strike of 1926. - The LWT series, Upstairs, DownstairsUpstairs, DownstairsUpstairs, Downstairs is a British drama television series originally produced by London Weekend Television and revived by the BBC. It ran on ITV in 68 episodes divided into five series from 1971 to 1975, and a sixth series shown on the BBC on three consecutive nights, 26–28 December 2010.Set in a...

, devoted an episode entitled "The Nine Days Wonder" (original airing date, 2 November 1975) to the general strike. The house is divided over the strike, with Lord Richard Bellamy and family siding with the government, and several of their servants supporting the miners—especially Ruby Finch, whose Uncle Len is a miner and has travelled to London as part of a miners' delegation from Barnsley. - Touchstone, a 2007 novel by Laurie R. KingLaurie R. KingLaurie R. King is an American author best known for her detective fiction. Among her books are the Mary Russell series of historical mysteries, featuring Sherlock Holmes as her mentor and later partner, and a series featuring Kate Martinelli, a fictional lesbian San Francisco, California, police...

, is set in the final weeks before the strike. The issues and factions involved, and an attempt to forestall the strike are key plot points. - A cozy mystery by Catriona McPherson, "Dandy Gilver and the Proper Care of Bloodstains," features a well-to-do investigator posing as a ladies' maid. Although her purpose is to solve a crime, Dandy also gets a downstairs view of the other servants' opinions on labor and the general strike in Edinburgh.

- A BBC series entitled The House of EliottThe House of EliottThe House of Eliott is a British television series produced and broadcast by the BBC in three series between 1991 and 1994. The series starred Stella Gonet and Louise Lombard as two sisters in 1920s London who establish a dressmaking business and eventually their own haute couture fashion house...

included an episode depicting the general strike. Season 2 Episode 9 has some of the seamstresses considering joining the strike because the Eliot sisters have lowered their pay. Madge is torn between her loyalty to the Eliots and to her father, who is a miner involved in the strike. Bea's husband, Jack Maddox, films several real-life scenes from the strike for a movie.

Footnotes

The 1975 BBC series Days of Hope depicts events that lead up to the 1926 strike.External links

- The General Strike at Spartacus Educational

- Ten Days in the Class War - Merseyside and the 1926 General Strike in Autumn 2006 issue of Nerve magazine, LiverpoolLiverpoolLiverpool is a city and metropolitan borough of Merseyside, England, along the eastern side of the Mersey Estuary. It was founded as a borough in 1207 and was granted city status in 1880...

- The General Strike Overview and reproductions of original documents at The Union Makes Us Strong, History of Trades Union CongressTrades Union CongressThe Trades Union Congress is a national trade union centre, a federation of trade unions in the United Kingdom, representing the majority of trade unions...

- General Strike 1926 at Sheffield City Council.