Universal jurisdiction

Encyclopedia

Universal jurisdiction or universality principle is a principle in public international law

(as opposed to private international law) whereby state

s claim criminal jurisdiction

over persons whose alleged crime

s were committed outside the boundaries of the prosecuting state, regardless of nationality, country of residence, or any other relation with the prosecuting country. The state backs its claim on the grounds that the crime committed is considered a crime against all, which any state is authorized to punish, as it is too serious to tolerate jurisdictional arbitrage

.

The concept of universal jurisdiction is therefore closely linked to the idea that certain international norms are erga omnes

, or owed to the entire world community, as well as the concept of jus cogens – that certain international law obligations are binding on all states and cannot be modified by treaty

.

According to critics, the principle justifies a unilateral act of wanton disregard of the sovereignty of a nation or the freedom of an individual concomitant to the pursuit of a vendetta or other ulterior motives, with the obvious assumption that the person or state thus disenfranchised is not in a position to bring retaliation to the state applying this principle.

The concept received a great deal of prominence with Belgium's 1993 "law of universal jurisdiction", which was amended in 2003 in order to reduce its scope following a case before the International Court of Justice

regarding an arrest warrant

issued under the law, entitled Case Concerning the Arrest Warrant of 11 April 2000 (Democratic Republic of the Congo v. Belgium). The creation of the International Criminal Court

(ICC) in 2002 reduced the perceived need to create universal jurisdiction laws, although the ICC is not entitled to judge crimes committed before 2002.

According to Amnesty International

, a proponent of universal jurisdiction, certain crimes pose so serious a threat to the international community as a whole, that states have a logical and moral duty to prosecute an individual responsible for it; no place should be a safe haven for those who have committed genocide

, crimes against humanity

, extrajudicial executions, war crime

s, torture

and forced disappearance

s.

Opponents, such as Henry Kissinger

, argue that universal jurisdiction is a breach on each state's sovereignty

: all states being equal in sovereignty, as affirmed by the United Nations Charter

, "Widespread agreement that human rights violations and crimes against humanity must be prosecuted has hindered active consideration of the proper role of international courts. Universal jurisdiction risks creating universal tyranny — that of judges." According to Kissinger, as a practical matter, since any number of states could set up such universal jurisdiction tribunals, the process could quickly degenerate into politically-driven show trial

s to attempt to place a quasi-judicial

stamp on a state's enemies or opponents.

The United Nations Security Council Resolution 1674

, adopted by the United Nations Security Council

on April 28, 2006, "Reaffirm[ed] the provisions of paragraphs 138 and 139 of the 2005 World Summit

Outcome Document regarding the responsibility to protect populations from genocide

, war crime

s, ethnic cleansing

and crimes against humanity

" and commits the Security Council to action to protect civilians in armed conflict.

, argues that universal jurisdiction has been around for a long time and gives examples that include American municipal legislation on aircraft

hijacking dating from 1970, and that the concept of universal jurisdiction allowed Israel to try Adolf Eichmann

in Jerusalem in 1961. Roth also argues that given the wide acceptance of clauses in treaties such as the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and the United Nations Convention Against Torture

of 1984, which requires signatory states to pass municipal law

s that are based on the concept of universal jurisdiction, it follows that such concepts are more than fifty years old. Henry Kissinger argues that it is a new one, citing the absence of the term universal jurisdiction from the sixth edition of Black's Law Dictionary

, published in 1990. Furthermore,

In 2003 Charles Taylor, the former president of Liberia

, was served with an arrest warrant by the Special Court for Sierra Leone

(SCSL) that was set up under the auspices of a treaty that binds only the United Nations and the Government of Sierra Leone. This is different from the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia

and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda

(that were specifically mentioned in the ICJ Arrest Warrant Case), that were set up under the UN Security Council, acting under Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter

that grant powers to the Security Council that are binding on all UN member states. In this respect the SCSL is more like the International Criminal Court

that although it denies immunity to Heads of State, States that are parties to the Rome Statute would be in violation of the ICJ ruling if they handed over a visiting head of state of a non-party State to the ICC. In examining the status of the SCSL Cesare Romano and André Nollkaemper argue that:

), even if the act the national committed was not illegal under the law of the territory in which an act has been committed. As an example, the American PROTECT Act of 2003

asserts jurisdiction over American citizens traveling abroad.

States can also in certain circumstances exercise jurisdiction over acts committed by foreign nationals on foreign territory. This form of jurisdiction tends to be much more controversial. Bases on which a state can exercise jurisdiction in this way:

, established in 2002, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda

(1994) and International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia

(1993), or the Nuremberg Trials

(1945–49). In these cases criminal jurisdiction is exercised by an international organization

, not by a state. The legal jurisdiction of an international tribunal is dependent on powers granted to it by the states that established it. In the case of the Nuremberg Trials, the legal basis for the tribunal was that the Allied powers were exercising German sovereign powers transferred to them by the German Instrument of Surrender

.

Established in The Hague

Established in The Hague

in 2002, the International Criminal Court (ICC) is an international tribunal empowered with the right to prosecute state-members' citizens for genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes, as defined by several international agreements, most prominently the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court

signed in 1998. It provides for ICC jurisdiction over-state party or on the territory of a non-state party where that non-state party has entered into an agreement with the court providing for it to have such jurisdiction in a particular case.

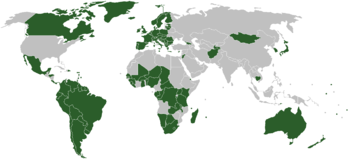

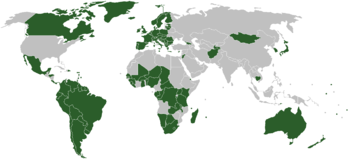

However, Amnesty International argues that since the end of the Second World War more than a dozen states have conducted investigations, commenced prosecutions and completed trials based on universal jurisdiction for the crimes or arrested people with a view to extraditing the persons to a state seeking to prosecute them. These states include: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Israel

, Mexico, Netherlands, Senegal

, Spain, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States.

. There was quickly an explosion of suits:

Confronted with this sharp increase in deposed suits, Belgium established the condition that the accused person must be Belgian or present in Belgium. An arrest warrant was issued in 2000 under this law against the then Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Democratic Republic of the Congo was challenged before the International Court of Justice

in the case entitled ICJ Arrest Warrant Case. The ICJ's decision issued on 14 February 2002 found that it did not have jurisdiction to consider the question of universal jurisdiction, instead deciding the question on the basis of immunity of high ranking State officials. However, the matter was addressed in separate and dissenting opinions, such as the separate opinion of President Guillaume who concluded that universal jurisdiction exists only in relation to piracy; and the dissenting opinion of Judge Oda who recognised piracy, hijacking, terrorism and genocide as crimes subject to universal jurisdiction.

On 1 August 2003, Belgium repealed the law on universal jurisdiction, and introduced a new law on extraterritorial jurisdiction

similar to or more restrictive than that of most other European countries. However, some cases that had already started continued. These included those concerning the Rwandan genocide, and complaints filed against the Chadian ex-President Hissène Habré

(dubbed the "African Pinochet

"). In September 2005, Habré was indicted for crimes against humanity, torture, war crimes and other human rights violations by a Belgian court. Arrested in Senegal

following requests from Senegalese courts, he is now under house arrest and waiting for (an improbable) extradition to Belgium.

. Michael Byers

, a University of British Columbia

law professor, has argued that these laws go further than the Rome Statute, providing Canadian courts with jurisdiction over acts pre-dating the ICC and occurring in territories outside of ICC member-states; “as a result, anyone who is present in Canada and alleged to have committed genocide, torture [...] anywhere, at any time, can be prosecuted [in Canada].”

, along with Kenneth Roth, has cited Israel

's prosecution of Adolf Eichmann

in 1961 as an assertion of universal jurisdiction. He claims that while Israel did invoke a statute specific to Nazi crimes against Jews

, its Supreme Court

claimed universal jurisdiction over crimes against humanity.

under Article 23.4 to cases in which Spaniards are victims, there is a relevant link to Spain, or the alleged perpetrators are in Spain. The law still has to pass the Senate, the high chamber, but passage is expected because it is supported by both major parties.

In 1999, Nobel peace prize

winner Rigoberta Menchú

brought a case against the Guatemala

n military leadership in a Spanish Court. Six officials, among them Efraín Ríos Montt

and Óscar Humberto Mejía, were formally charged on 7 July 2006 to appear in the Spanish National Court after Spain's Constitutional Court ruled in September 2005, the Spanish Constitutional Court declaration that the "principle of universal jurisdiction prevails over the existence of national interests", following the Menchu suit brought against the officials for atrocities committed in the Guatemalan Civil War

In June 2003, Spanish judge Baltasar Garzón

jailed Ricardo Miguel Cavallo, a former Argentine

naval officer, who was extradited from England to Spain pending his trial on charges of genocide and terrorism relating to the years of Argentina's military dictatorship.

On 11 January 2006 the Spanish High Court accepted to investigate a case in which seven former Chinese officials, including the former President of China Jiang Zemin

and former Prime Minister Li Peng

were alleged to have participated in a genocide in Tibet

. This investigation follows a Spanish Constitutional Court (26 September 2005) ruling that Spanish courts could try genocide cases even if they did not involve Spanish nationals. China denounced the investigation as an interference in its internal affairs and dismissed the allegations as "sheer fabrication". The case was shelved in 2010, because of a law passed in 2009 that restricted High Court investigations to those "involving Spanish victims, suspects who are in Spain, or some other obvious link with Spain".

Complaints were lodged against former Israeli Defense Forces chief of General Staff Lt.-Gen. (res.) Dan Halutz

and other six other senior Israeli political and military officials by pro-Palestinian organizations, who sought to prosecute them in Spain under the principle of universal jurisdiction. On 29 January 2009, Fernando Andreu

, a judge of the Audiencia Nacional, opened preliminary investigations into claims that a targeted killing

attack in Gaza

in 2002 warranted the prosecution of Halutz, the former Israeli defence minister Binyamin Ben-Eliezer

, the former defence chief-of-staff Moshe Ya'alon

, and four others, for crimes against humanity

. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu

strongly criticized the decision, and Israeli officials refused to provide information requested by the Spanish court. The attack had killed the founder and leader of the military wing of the Islamic terrorist organisation Hamas

, Salah Shehade, who Israel said was responsible for hundreds of civilian deaths. The attack also killed 14 others (including his wife and 9 children). It had targeted the building in which Shahade was hiding in Gaza City. It also wounded some 150 Palestinians, according to the complaint (or 50, according to other reports). The Israeli chief of operations and prime minister apologized officially, saying they were unaware, due to faulty intelligence, that civilians would be in the house. A regretful Ya'alon also mentioned that the army had passed up on several earlier opportunities to kill Shehade, because he was with his wife or children, and that each time Shehadeh went on to direct more suicide bombings against Israel. The investigation in the case was halted on 30 June 2009 by a decision of a panel of 18 judges of the Audiencia Nacional. The Spanish Court of Appeals rejected the lower court's decision, and on appeal in April 2010 the Supreme Court of Spain upheld the Court of Appeals decision against conducting an official inquiry into the IDF's targeted killing of Shehadeh.

case of 1991. It is illegal for any Australian citizen or resident to engage in sexual relations with anyone under 16 years of age, anywhere in the world, and such an act is treated as an instance of child sex tourism

, a severe crime punishable by a term of imprisonment of up to 17 years; this applies even in jurisdictions where such acts are legal because the age of consent

is lower than 16.

In December 2009 a court in London issued an arrest warrant for Tzipi Livni

in connection with accusations of war crimes in the Gaza Strip during Operation Cast Lead (2008–2009). The warrant was issued on 12 December and revoked on 14 December 2009 after it was revealed that Livni had not entered British territory. The warrant was later denounced as "cynical" by the Israeli foreign ministry, while Livni's office said she was "proud of all her decisions in Operation Cast Lead". Livni herself called the arrest warrant "an abuse of the British legal system".

Similarly a January visit to Britain by a team of Israel Defense Force (IDF) was cancelled over concerns that arrest warrants would be sought by pro-Palestinian advocates in connection with allegations of war crimes under laws of universal jurisdiction.

International law

Public international law concerns the structure and conduct of sovereign states; analogous entities, such as the Holy See; and intergovernmental organizations. To a lesser degree, international law also may affect multinational corporations and individuals, an impact increasingly evolving beyond...

(as opposed to private international law) whereby state

Sovereign state

A sovereign state, or simply, state, is a state with a defined territory on which it exercises internal and external sovereignty, a permanent population, a government, and the capacity to enter into relations with other sovereign states. It is also normally understood to be a state which is neither...

s claim criminal jurisdiction

Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction is the practical authority granted to a formally constituted legal body or to a political leader to deal with and make pronouncements on legal matters and, by implication, to administer justice within a defined area of responsibility...

over persons whose alleged crime

Crime

Crime is the breach of rules or laws for which some governing authority can ultimately prescribe a conviction...

s were committed outside the boundaries of the prosecuting state, regardless of nationality, country of residence, or any other relation with the prosecuting country. The state backs its claim on the grounds that the crime committed is considered a crime against all, which any state is authorized to punish, as it is too serious to tolerate jurisdictional arbitrage

Jurisdictional arbitrage

Jurisdictional arbitrage is the practice of taking advantage of the discrepancies between competing legal jurisdictions. It takes its name from arbitrage, the practice in finance of purchasing a good at a lower price in one market and selling it at a higher price in another...

.

The concept of universal jurisdiction is therefore closely linked to the idea that certain international norms are erga omnes

Erga omnes

In legal terminology, erga omnes rights or obligations are owed toward all. For instance a property right is an erga omnes entitlement, and therefore enforceable against anybody infringing that right...

, or owed to the entire world community, as well as the concept of jus cogens – that certain international law obligations are binding on all states and cannot be modified by treaty

Treaty

A treaty is an express agreement under international law entered into by actors in international law, namely sovereign states and international organizations. A treaty may also be known as an agreement, protocol, covenant, convention or exchange of letters, among other terms...

.

According to critics, the principle justifies a unilateral act of wanton disregard of the sovereignty of a nation or the freedom of an individual concomitant to the pursuit of a vendetta or other ulterior motives, with the obvious assumption that the person or state thus disenfranchised is not in a position to bring retaliation to the state applying this principle.

The concept received a great deal of prominence with Belgium's 1993 "law of universal jurisdiction", which was amended in 2003 in order to reduce its scope following a case before the International Court of Justice

International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice is the primary judicial organ of the United Nations. It is based in the Peace Palace in The Hague, Netherlands...

regarding an arrest warrant

Arrest warrant

An arrest warrant is a warrant issued by and on behalf of the state, which authorizes the arrest and detention of an individual.-Canada:Arrest warrants are issued by a judge or justice of the peace under the Criminal Code of Canada....

issued under the law, entitled Case Concerning the Arrest Warrant of 11 April 2000 (Democratic Republic of the Congo v. Belgium). The creation of the International Criminal Court

International Criminal Court

The International Criminal Court is a permanent tribunal to prosecute individuals for genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression .It came into being on 1 July 2002—the date its founding treaty, the Rome Statute of the...

(ICC) in 2002 reduced the perceived need to create universal jurisdiction laws, although the ICC is not entitled to judge crimes committed before 2002.

According to Amnesty International

Amnesty International

Amnesty International is an international non-governmental organisation whose stated mission is "to conduct research and generate action to prevent and end grave abuses of human rights, and to demand justice for those whose rights have been violated."Following a publication of Peter Benenson's...

, a proponent of universal jurisdiction, certain crimes pose so serious a threat to the international community as a whole, that states have a logical and moral duty to prosecute an individual responsible for it; no place should be a safe haven for those who have committed genocide

Genocide

Genocide is defined as "the deliberate and systematic destruction, in whole or in part, of an ethnic, racial, religious, or national group", though what constitutes enough of a "part" to qualify as genocide has been subject to much debate by legal scholars...

, crimes against humanity

Crime against humanity

Crimes against humanity, as defined by the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court Explanatory Memorandum, "are particularly odious offenses in that they constitute a serious attack on human dignity or grave humiliation or a degradation of one or more human beings...

, extrajudicial executions, war crime

War crime

War crimes are serious violations of the laws applicable in armed conflict giving rise to individual criminal responsibility...

s, torture

Torture

Torture is the act of inflicting severe pain as a means of punishment, revenge, forcing information or a confession, or simply as an act of cruelty. Throughout history, torture has often been used as a method of political re-education, interrogation, punishment, and coercion...

and forced disappearance

Forced disappearance

In international human rights law, a forced disappearance occurs when a person is secretly abducted or imprisoned by a state or political organization or by a third party with the authorization, support, or acquiescence of a state or political organization, followed by a refusal to acknowledge the...

s.

Opponents, such as Henry Kissinger

Henry Kissinger

Heinz Alfred "Henry" Kissinger is a German-born American academic, political scientist, diplomat, and businessman. He is a recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize. He served as National Security Advisor and later concurrently as Secretary of State in the administrations of Presidents Richard Nixon and...

, argue that universal jurisdiction is a breach on each state's sovereignty

Sovereignty

Sovereignty is the quality of having supreme, independent authority over a geographic area, such as a territory. It can be found in a power to rule and make law that rests on a political fact for which no purely legal explanation can be provided...

: all states being equal in sovereignty, as affirmed by the United Nations Charter

United Nations Charter

The Charter of the United Nations is the foundational treaty of the international organization called the United Nations. It was signed at the San Francisco War Memorial and Performing Arts Center in San Francisco, United States, on 26 June 1945, by 50 of the 51 original member countries...

, "Widespread agreement that human rights violations and crimes against humanity must be prosecuted has hindered active consideration of the proper role of international courts. Universal jurisdiction risks creating universal tyranny — that of judges." According to Kissinger, as a practical matter, since any number of states could set up such universal jurisdiction tribunals, the process could quickly degenerate into politically-driven show trial

Show trial

The term show trial is a pejorative description of a type of highly public trial in which there is a strong connotation that the judicial authorities have already determined the guilt of the defendant. The actual trial has as its only goal to present the accusation and the verdict to the public as...

s to attempt to place a quasi-judicial

Quasi-judicial body

A quasi-judicial body is an individual or organization which has powers resembling those of a court of law or judge and is able to remedy a situation or impose legal penalties on a person or organization.-Powers:...

stamp on a state's enemies or opponents.

The United Nations Security Council Resolution 1674

United Nations Security Council Resolution 1674

United Nations Security Council Resolution 1674, adopted unanimously on April 28, 2006, after reaffirming resolutions 1265 and 1296 concerning the protection of civilians in armed conflict and Resolution 1631 on co-operation between the United Nations and regional organisations, the Council...

, adopted by the United Nations Security Council

United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council is one of the principal organs of the United Nations and is charged with the maintenance of international peace and security. Its powers, outlined in the United Nations Charter, include the establishment of peacekeeping operations, the establishment of...

on April 28, 2006, "Reaffirm[ed] the provisions of paragraphs 138 and 139 of the 2005 World Summit

2005 World Summit

The 2005 World Summit, 14–16 September 2005, was a follow-up summit meeting to the United Nations' 2000 Millennium Summit, which led to the Millennium Declaration of the Millennium Development Goals...

Outcome Document regarding the responsibility to protect populations from genocide

Genocide

Genocide is defined as "the deliberate and systematic destruction, in whole or in part, of an ethnic, racial, religious, or national group", though what constitutes enough of a "part" to qualify as genocide has been subject to much debate by legal scholars...

, war crime

War crime

War crimes are serious violations of the laws applicable in armed conflict giving rise to individual criminal responsibility...

s, ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is a purposeful policy designed by one ethnic or religious group to remove by violent and terror-inspiring means the civilian population of another ethnic orreligious group from certain geographic areas....

and crimes against humanity

Crime against humanity

Crimes against humanity, as defined by the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court Explanatory Memorandum, "are particularly odious offenses in that they constitute a serious attack on human dignity or grave humiliation or a degradation of one or more human beings...

" and commits the Security Council to action to protect civilians in armed conflict.

Novelty

There is disagreement over whether universal jurisdiction is an old or new concept. Kenneth Roth, the executive director of Human Rights WatchHuman Rights Watch

Human Rights Watch is an international non-governmental organization that conducts research and advocacy on human rights. Its headquarters are in New York City and it has offices in Berlin, Beirut, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo,...

, argues that universal jurisdiction has been around for a long time and gives examples that include American municipal legislation on aircraft

Aircraft

An aircraft is a vehicle that is able to fly by gaining support from the air, or, in general, the atmosphere of a planet. An aircraft counters the force of gravity by using either static lift or by using the dynamic lift of an airfoil, or in a few cases the downward thrust from jet engines.Although...

hijacking dating from 1970, and that the concept of universal jurisdiction allowed Israel to try Adolf Eichmann

Adolf Eichmann

Adolf Otto Eichmann was a German Nazi and SS-Obersturmbannführer and one of the major organizers of the Holocaust...

in Jerusalem in 1961. Roth also argues that given the wide acceptance of clauses in treaties such as the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and the United Nations Convention Against Torture

United Nations Convention Against Torture

The United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment is an international human rights instrument, under the review of the United Nations, that aims to prevent torture around the world....

of 1984, which requires signatory states to pass municipal law

Municipal law

Municipal law is the national, domestic, or internal law of a sovereign state defined in opposition to international law. Municipal law includes not only law at the national level, but law at the state, provincial, territorial, regional or local levels...

s that are based on the concept of universal jurisdiction, it follows that such concepts are more than fifty years old. Henry Kissinger argues that it is a new one, citing the absence of the term universal jurisdiction from the sixth edition of Black's Law Dictionary

Black's Law Dictionary

Black's Law Dictionary is the most widely used law dictionary in the United States. It was founded by Henry Campbell Black. It is the reference of choice for definitions in legal briefs and court opinions and has been cited as a secondary legal authority in many U.S...

, published in 1990. Furthermore,

Immunity for state officials

On 14 February 2002 the International Court of Justice in the ICJ Arrest Warrant Case concluded that State officials did have immunity under international law while serving in office. The court also concluded that immunity was not granted to State officials for their own benefit, but instead to ensure the effective performance of their functions on behalf of their respective States. The court stated that when abroad, State officials enjoy full immunity from arrest in another State on criminal charges, including charges of war crimes or crimes against humanity. The ICJ did qualify its conclusions, stating that State officers "may be subject to criminal proceedings before certain international criminal courts, where they have jurisdiction. Examples include the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda . . . , and the future International Criminal Court."In 2003 Charles Taylor, the former president of Liberia

Liberia

Liberia , officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Sierra Leone on the west, Guinea on the north and Côte d'Ivoire on the east. Liberia's coastline is composed of mostly mangrove forests while the more sparsely populated inland consists of forests that open...

, was served with an arrest warrant by the Special Court for Sierra Leone

Special Court for Sierra Leone

The Special Court for Sierra Leone is an independent judicial body set up to "try those who bear greatest responsibility" for the war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in Sierra Leone after 30 November 1996 during the Sierra Leone Civil War...

(SCSL) that was set up under the auspices of a treaty that binds only the United Nations and the Government of Sierra Leone. This is different from the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia

International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia

The International Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of the Former Yugoslavia since 1991, more commonly referred to as the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia or ICTY, is a...

and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda

International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda is an international court established in November 1994 by the United Nations Security Council in Resolution 955 in order to judge people responsible for the Rwandan Genocide and other serious violations of international law in Rwanda, or by Rwandan...

(that were specifically mentioned in the ICJ Arrest Warrant Case), that were set up under the UN Security Council, acting under Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter

United Nations Charter

The Charter of the United Nations is the foundational treaty of the international organization called the United Nations. It was signed at the San Francisco War Memorial and Performing Arts Center in San Francisco, United States, on 26 June 1945, by 50 of the 51 original member countries...

that grant powers to the Security Council that are binding on all UN member states. In this respect the SCSL is more like the International Criminal Court

International Criminal Court

The International Criminal Court is a permanent tribunal to prosecute individuals for genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression .It came into being on 1 July 2002—the date its founding treaty, the Rome Statute of the...

that although it denies immunity to Heads of State, States that are parties to the Rome Statute would be in violation of the ICJ ruling if they handed over a visiting head of state of a non-party State to the ICC. In examining the status of the SCSL Cesare Romano and André Nollkaemper argue that:

Extraterritorial jurisdiction

International jurisdiction differs from "territorial jurisdiction", where justice is exercised by a state in relation to crimes committed on its territory (territorial jurisdiction). States can also exercise jurisdiction on crimes committed by their nationals abroad (extraterritorial jurisdictionExtraterritorial jurisdiction

Extraterritorial jurisdiction is the legal ability of a government to exercise authority beyond its normal boundaries.Any authority can, of course, claim ETJ over any external territory they wish...

), even if the act the national committed was not illegal under the law of the territory in which an act has been committed. As an example, the American PROTECT Act of 2003

PROTECT Act of 2003

The PROTECT Act of 2003 is a United States law with the stated intent of preventing child abuse. "PROTECT" is a "backronym" which stands for "Prosecutorial Remedies and Other Tools to end the Exploitation of Children Today"....

asserts jurisdiction over American citizens traveling abroad.

States can also in certain circumstances exercise jurisdiction over acts committed by foreign nationals on foreign territory. This form of jurisdiction tends to be much more controversial. Bases on which a state can exercise jurisdiction in this way:

- The least controversial basis is that under which a state can exercise jurisdiction over acts that affect the fundamental interests of the state, such as spyingEspionageEspionage or spying involves an individual obtaining information that is considered secret or confidential without the permission of the holder of the information. Espionage is inherently clandestine, lest the legitimate holder of the information change plans or take other countermeasures once it...

, even if the act was committed by foreign nationals on foreign territory. The Information Technology Act 2000 of India largely supports the extraterritoriality of the said Act. The law states that a contravention of the Act that affects any computer or computer network situated in India will be punishable by India – irrespective of the culprits location and nationality.

- Also relatively non-controversial is the ability of a state to try its own nationals from crimes committed abroad. Some nations such as France as a matter of law will refuse to extradite its own citizens, but will instead try them for crimes committed abroad.

- More controversial is the exercise of jurisdiction where the victim of the crime is a national of the state exercising jurisdiction. In the past some states have claimed this jurisdiction (e.g., Mexico), while others have been strongly opposed to it (e.g., the United States, except in cases in which an American citizen is a victim). In more recent years however, a broad global consensus has emerged in permitting its use in the case of torture, "forced disappearances" or terrorist offences (due in part to it being permitted by the various United NationsUnited NationsThe United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

conventions on terrorism); but its application in other areas is still highly controversial. For example, former dictator of Chile Augusto PinochetAugusto PinochetAugusto José Ramón Pinochet Ugarte, more commonly known as Augusto Pinochet , was a Chilean army general and dictator who assumed power in a coup d'état on 11 September 1973...

was arrested in London in 1998, on Spanish judge Baltazar Garzon's demand, on charges of human rights abuses, not on the grounds of universal jurisdiction but rather on the grounds that some of the victims of the abuses committed in Chile were Spanish citizens. Spain then sought his extraditionExtraditionExtradition is the official process whereby one nation or state surrenders a suspected or convicted criminal to another nation or state. Between nation states, extradition is regulated by treaties...

from Britain, again, not on the grounds of universal jurisdiction, but by invoking the law of the European UnionEuropean UnionThe European Union is an economic and political union of 27 independent member states which are located primarily in Europe. The EU traces its origins from the European Coal and Steel Community and the European Economic Community , formed by six countries in 1958...

regarding extradition; and he was finally released on grounds of health. Argentinian Alfredo AstizAlfredo AstizAlfredo Ignacio Astiz was a Commander, intelligence office and maritime commando in the Argentine Navy during the dictatorial rule of Jorge Rafael Videla in the Proceso de Reorganización Nacional...

's sentence is part of this juridical frame.

International tribunals

Universal jurisdiction asserted by a state must also be distinguished from the jurisdiction of an international tribunal, such as the International Criminal CourtInternational Criminal Court

The International Criminal Court is a permanent tribunal to prosecute individuals for genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression .It came into being on 1 July 2002—the date its founding treaty, the Rome Statute of the...

, established in 2002, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda

International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda is an international court established in November 1994 by the United Nations Security Council in Resolution 955 in order to judge people responsible for the Rwandan Genocide and other serious violations of international law in Rwanda, or by Rwandan...

(1994) and International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia

International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia

The International Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of the Former Yugoslavia since 1991, more commonly referred to as the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia or ICTY, is a...

(1993), or the Nuremberg Trials

Nuremberg Trials

The Nuremberg Trials were a series of military tribunals, held by the victorious Allied forces of World War II, most notable for the prosecution of prominent members of the political, military, and economic leadership of the defeated Nazi Germany....

(1945–49). In these cases criminal jurisdiction is exercised by an international organization

International organization

An intergovernmental organization, sometimes rendered as an international governmental organization and both abbreviated as IGO, is an organization composed primarily of sovereign states , or of other intergovernmental organizations...

, not by a state. The legal jurisdiction of an international tribunal is dependent on powers granted to it by the states that established it. In the case of the Nuremberg Trials, the legal basis for the tribunal was that the Allied powers were exercising German sovereign powers transferred to them by the German Instrument of Surrender

German Instrument of Surrender, 1945

The German Instrument of Surrender was the legal instrument that established the armistice ending World War II in Europe. It was signed by representatives of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht and the Allied Expeditionary Force together with the Soviet High Command, French representative signing as...

.

The Hague

The Hague is the capital city of the province of South Holland in the Netherlands. With a population of 500,000 inhabitants , it is the third largest city of the Netherlands, after Amsterdam and Rotterdam...

in 2002, the International Criminal Court (ICC) is an international tribunal empowered with the right to prosecute state-members' citizens for genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes, as defined by several international agreements, most prominently the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court

Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court

The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court is the treaty that established the International Criminal Court . It was adopted at a diplomatic conference in Rome on 17 July 1998 and it entered into force on 1 July 2002. As of 13 October 2011, 119 states are party to the statute...

signed in 1998. It provides for ICC jurisdiction over-state party or on the territory of a non-state party where that non-state party has entered into an agreement with the court providing for it to have such jurisdiction in a particular case.

However, Amnesty International argues that since the end of the Second World War more than a dozen states have conducted investigations, commenced prosecutions and completed trials based on universal jurisdiction for the crimes or arrested people with a view to extraditing the persons to a state seeking to prosecute them. These states include: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Israel

Israel

The State of Israel is a parliamentary republic located in the Middle East, along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea...

, Mexico, Netherlands, Senegal

Senegal

Senegal , officially the Republic of Senegal , is a country in western Africa. It owes its name to the Sénégal River that borders it to the east and north...

, Spain, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States.

All states parties to the Convention against Torture and the Inter-American ConventionInter-American Convention to Prevent and Punish TortureThe Inter-American Convention to Prevent and Punish Torture is an international human rights instrument, created in 1985 within the Western Hemisphere Organization of American States and intended to prevent torture and other similar activities....

are obliged whenever a person suspected of torture is found in their territory to submit the case to their prosecuting authorities for the purposes of prosecution, or to extradite that person. In addition, it is now widely recognized that states, even those that are not states parties to these treaties, may exercise universal jurisdiction over torture under customary international law.

France

The article 689 of the code de procédure pénale states the infractions that can be judged in France when they were committed outside French territory either by French citizens or foreigners. The following infractions may be prosecuted :- Torture

- Terrorism

- Nuclear smuggling

- Naval piracy

- Airplanes hijacking

Belgium

In 1993, Belgium's Parliament voted a "law of universal jurisdiction" (sometimes referred to as "Belgium's genocide law"), allowing it to judge people accused of war crimes, crimes against humanity or genocide. In 2001, four Rwandan citizens were convicted and given sentences from 12 to 20 years' imprisonment for their involvement in 1994 Rwandan genocideRwandan Genocide

The Rwandan Genocide was the 1994 mass murder of an estimated 800,000 people in the small East African nation of Rwanda. Over the course of approximately 100 days through mid-July, over 500,000 people were killed, according to a Human Rights Watch estimate...

. There was quickly an explosion of suits:

- Prime Minister Ariel SharonAriel SharonAriel Sharon is an Israeli statesman and retired general, who served as Israel’s 11th Prime Minister. He has been in a permanent vegetative state since suffering a stroke on 4 January 2006....

was accused of involvement in the 1982 Sabra-Shatila massacre in Lebanon, conducted by a Christian militia - Israelis deposed a suit against Yasser ArafatYasser ArafatMohammed Yasser Abdel Rahman Abdel Raouf Arafat al-Qudwa al-Husseini , popularly known as Yasser Arafat or by his kunya Abu Ammar , was a Palestinian leader and a Laureate of the Nobel Prize. He was Chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization , President of the Palestinian National Authority...

for his responsibility for terrorist actions - In 2003, Iraqi victims of a 1991 Bagdad bombingGulf WarThe Persian Gulf War , commonly referred to as simply the Gulf War, was a war waged by a U.N.-authorized coalition force from 34 nations led by the United States, against Iraq in response to Iraq's invasion and annexation of Kuwait.The war is also known under other names, such as the First Gulf...

deposed a suit against George H.W. Bush, Colin PowellColin PowellColin Luther Powell is an American statesman and a retired four-star general in the United States Army. He was the 65th United States Secretary of State, serving under President George W. Bush from 2001 to 2005. He was the first African American to serve in that position. During his military...

and Dick CheneyDick CheneyRichard Bruce "Dick" Cheney served as the 46th Vice President of the United States , under George W. Bush....

.

Confronted with this sharp increase in deposed suits, Belgium established the condition that the accused person must be Belgian or present in Belgium. An arrest warrant was issued in 2000 under this law against the then Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Democratic Republic of the Congo was challenged before the International Court of Justice

International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice is the primary judicial organ of the United Nations. It is based in the Peace Palace in The Hague, Netherlands...

in the case entitled ICJ Arrest Warrant Case. The ICJ's decision issued on 14 February 2002 found that it did not have jurisdiction to consider the question of universal jurisdiction, instead deciding the question on the basis of immunity of high ranking State officials. However, the matter was addressed in separate and dissenting opinions, such as the separate opinion of President Guillaume who concluded that universal jurisdiction exists only in relation to piracy; and the dissenting opinion of Judge Oda who recognised piracy, hijacking, terrorism and genocide as crimes subject to universal jurisdiction.

On 1 August 2003, Belgium repealed the law on universal jurisdiction, and introduced a new law on extraterritorial jurisdiction

Extraterritorial jurisdiction

Extraterritorial jurisdiction is the legal ability of a government to exercise authority beyond its normal boundaries.Any authority can, of course, claim ETJ over any external territory they wish...

similar to or more restrictive than that of most other European countries. However, some cases that had already started continued. These included those concerning the Rwandan genocide, and complaints filed against the Chadian ex-President Hissène Habré

Hissène Habré

Hissène Habré , also spelled Hissen Habré, was the leader of Chad from 1982 until he was deposed in 1990.-Early life:...

(dubbed the "African Pinochet

Augusto Pinochet

Augusto José Ramón Pinochet Ugarte, more commonly known as Augusto Pinochet , was a Chilean army general and dictator who assumed power in a coup d'état on 11 September 1973...

"). In September 2005, Habré was indicted for crimes against humanity, torture, war crimes and other human rights violations by a Belgian court. Arrested in Senegal

Senegal

Senegal , officially the Republic of Senegal , is a country in western Africa. It owes its name to the Sénégal River that borders it to the east and north...

following requests from Senegalese courts, he is now under house arrest and waiting for (an improbable) extradition to Belgium.

Canada

To implement the Rome Statute, Canada passed the Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes ActCrimes Against Humanity and War Crimes Act

The Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes Act is a statute of the Parliament of Canada. The Act implements Canada's obligations under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court...

. Michael Byers

Michael Byers (Canadian author)

Michael Byers is a Canadian legal scholar and non-fiction author.- Academic background :Byers was educated at the University of Saskatchewan, where he received his BA with majors in English literature and political studies. He then studied at McGill University, achieving his LLB and BCL degrees. He...

, a University of British Columbia

University of British Columbia

The University of British Columbia is a public research university. UBC’s two main campuses are situated in Vancouver and in Kelowna in the Okanagan Valley...

law professor, has argued that these laws go further than the Rome Statute, providing Canadian courts with jurisdiction over acts pre-dating the ICC and occurring in territories outside of ICC member-states; “as a result, anyone who is present in Canada and alleged to have committed genocide, torture [...] anywhere, at any time, can be prosecuted [in Canada].”

Czech Republic

According to § 6 (Personality principle) of the Czech penal code, the Czech law is applied to every criminal offense committed abroad by a Czech citizen or by a stateless person who has granted permanent residence on the territory of the Czech Republic.Israel

The moral philosopher Peter SingerPeter Singer

Peter Albert David Singer is an Australian philosopher who is the Ira W. DeCamp Professor of Bioethics at Princeton University and Laureate Professor at the Centre for Applied Philosophy and Public Ethics at the University of Melbourne...

, along with Kenneth Roth, has cited Israel

Israel

The State of Israel is a parliamentary republic located in the Middle East, along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea...

's prosecution of Adolf Eichmann

Adolf Eichmann

Adolf Otto Eichmann was a German Nazi and SS-Obersturmbannführer and one of the major organizers of the Holocaust...

in 1961 as an assertion of universal jurisdiction. He claims that while Israel did invoke a statute specific to Nazi crimes against Jews

Jews

The Jews , also known as the Jewish people, are a nation and ethnoreligious group originating in the Israelites or Hebrews of the Ancient Near East. The Jewish ethnicity, nationality, and religion are strongly interrelated, as Judaism is the traditional faith of the Jewish nation...

, its Supreme Court

Supreme Court of Israel

The Supreme Court is at the head of the court system and highest judicial instance in Israel. The Supreme Court sits in Jerusalem.The area of its jurisdiction is all of Israel and the Israeli-occupied territories. A ruling of the Supreme Court is binding upon every court, other than the Supreme...

claimed universal jurisdiction over crimes against humanity.

Spain

Spanish law recognizes the principle of the universal jurisdiction. Article 23.4 of the Judicial Power Organization Act (LOPJ), enacted on 1 July 1985, establishes that Spanish courts have jurisdiction over crimes committed by Spaniards or foreign citizens outside Spain when such crimes can be described according to Spanish criminal law as genocide, terrorism, or some other, as well as any other crime that, according to international treaties or conventions, must be prosecuted in Spain. On 25 July 2009 the Spanish Congress passed a law that limits the competence of the Audiencia NacionalAudiencia Nacional of Spain

The Audiencia Nacional is a a special and exceptional high court in Spain. It has its seat in Madrid and jurisdiction over all of Spain and international crimes which come under the competence of Spanish courts....

under Article 23.4 to cases in which Spaniards are victims, there is a relevant link to Spain, or the alleged perpetrators are in Spain. The law still has to pass the Senate, the high chamber, but passage is expected because it is supported by both major parties.

In 1999, Nobel peace prize

Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes bequeathed by the Swedish industrialist and inventor Alfred Nobel.-Background:According to Nobel's will, the Peace Prize shall be awarded to the person who...

winner Rigoberta Menchú

Rigoberta Menchú

Rigoberta Menchú Tum is an indigenous Guatemalan, of the K'iche' ethnic group. Menchú has dedicated her life to publicizing the plight of Guatemala's indigenous peoples during and after the Guatemalan Civil War , and to promoting indigenous rights in the country...

brought a case against the Guatemala

Guatemala

Guatemala is a country in Central America bordered by Mexico to the north and west, the Pacific Ocean to the southwest, Belize to the northeast, the Caribbean to the east, and Honduras and El Salvador to the southeast...

n military leadership in a Spanish Court. Six officials, among them Efraín Ríos Montt

Efraín Ríos Montt

José Efraín Ríos Montt is a former de facto President of Guatemala, dictator, army general, and former president of Congress. In the 2003 presidential elections, he unsuccessfully ran as the candidate of the ruling Guatemalan Republican Front .Huehuetenango-born Ríos Montt remains one of the most...

and Óscar Humberto Mejía, were formally charged on 7 July 2006 to appear in the Spanish National Court after Spain's Constitutional Court ruled in September 2005, the Spanish Constitutional Court declaration that the "principle of universal jurisdiction prevails over the existence of national interests", following the Menchu suit brought against the officials for atrocities committed in the Guatemalan Civil War

Guatemalan Civil War

The Guatemalan Civil War ran from 1960-1996. The thirty-six-year civil war began as a grassroots, popular response to the rightist and military usurpation of civil government , and the President's disrespect for the human and civil rights of the majority of the population...

In June 2003, Spanish judge Baltasar Garzón

Baltasar Garzón

Baltasar Garzón Real is a Spanish jurist who served on Spain's central criminal court, the Audiencia Nacional. He was the examining magistrate of the Juzgado Central de Instrucción No...

jailed Ricardo Miguel Cavallo, a former Argentine

Argentina

Argentina , officially the Argentine Republic , is the second largest country in South America by land area, after Brazil. It is constituted as a federation of 23 provinces and an autonomous city, Buenos Aires...

naval officer, who was extradited from England to Spain pending his trial on charges of genocide and terrorism relating to the years of Argentina's military dictatorship.

On 11 January 2006 the Spanish High Court accepted to investigate a case in which seven former Chinese officials, including the former President of China Jiang Zemin

Jiang Zemin

Jiang Zemin is a former Chinese politician, who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of China from 1989 to 2002, as President of the People's Republic of China from 1993 to 2003, and as Chairman of the Central Military Commission from 1989 to 2005...

and former Prime Minister Li Peng

Li Peng

Li Peng served as the fourth Premier of the People's Republic of China, between 1987 and 1998, and the Chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress, China's top legislative body, from 1998 to 2003. For much of the 1990s Li was ranked second in the Communist Party of China ...

were alleged to have participated in a genocide in Tibet

Tibet

Tibet is a plateau region in Asia, north-east of the Himalayas. It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people as well as some other ethnic groups such as Monpas, Qiang, and Lhobas, and is now also inhabited by considerable numbers of Han and Hui people...

. This investigation follows a Spanish Constitutional Court (26 September 2005) ruling that Spanish courts could try genocide cases even if they did not involve Spanish nationals. China denounced the investigation as an interference in its internal affairs and dismissed the allegations as "sheer fabrication". The case was shelved in 2010, because of a law passed in 2009 that restricted High Court investigations to those "involving Spanish victims, suspects who are in Spain, or some other obvious link with Spain".

Complaints were lodged against former Israeli Defense Forces chief of General Staff Lt.-Gen. (res.) Dan Halutz

Dan Halutz

' is an Israeli Air Force Lt. General and former Chief of Staff of the Israel Defense Forces and commander of the Israeli Air Force. Halutz was appointed as Chief of Staff on June 1, 2005. On January 17, 2007 he announced his resignation. He has a degree in economics. He was born to a Mizrahi...

and other six other senior Israeli political and military officials by pro-Palestinian organizations, who sought to prosecute them in Spain under the principle of universal jurisdiction. On 29 January 2009, Fernando Andreu

Fernando Andreu

Fernando Andreu is a judge of the National Audience in Spain. He plays a leading role especially in humanitarian law and in pursuing war-crime and similar issues ....

, a judge of the Audiencia Nacional, opened preliminary investigations into claims that a targeted killing

Targeted killing

Targeted killing is the deliberate, specific targeting and killing, by a government or its agents, of a supposed terrorist or of a supposed "unlawful combatant" who is not in that government's custody...

attack in Gaza

Gaza Strip

thumb|Gaza city skylineThe Gaza Strip lies on the Eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea. The Strip borders Egypt on the southwest and Israel on the south, east and north. It is about long, and between 6 and 12 kilometres wide, with a total area of...

in 2002 warranted the prosecution of Halutz, the former Israeli defence minister Binyamin Ben-Eliezer

Binyamin Ben-Eliezer

Binyamin Fuad Ben-Eliezer , , born 12 February 1936) is an Israeli politician and former military officer of Iraqi origin. He currently serves as a member of the Knesset for the Labor Party, and has held several ministerial posts, including Minister of Industry, Trade and Labour, Minister of...

, the former defence chief-of-staff Moshe Ya'alon

Moshe Ya'alon

Moshe "Bogie" Ya'alon is an Israeli politician and former Chief of Staff of the Israel Defense Forces. He currently serves as a member of the Knesset for Likud, as well as the country's Vice Prime Minister and Minister of Strategic Affairs.-Early life:...

, and four others, for crimes against humanity

Crime against humanity

Crimes against humanity, as defined by the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court Explanatory Memorandum, "are particularly odious offenses in that they constitute a serious attack on human dignity or grave humiliation or a degradation of one or more human beings...

. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu

Benjamin Netanyahu

Benjamin "Bibi" Netanyahu is the current Prime Minister of Israel. He serves also as the Chairman of the Likud Party, as a Knesset member, as the Health Minister of Israel, as the Pensioner Affairs Minister of Israel and as the Economic Strategy Minister of Israel.Netanyahu is the first and, to...

strongly criticized the decision, and Israeli officials refused to provide information requested by the Spanish court. The attack had killed the founder and leader of the military wing of the Islamic terrorist organisation Hamas

Hamas

Hamas is the Palestinian Sunni Islamic or Islamist political party that governs the Gaza Strip. Hamas also has a military wing, the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades...

, Salah Shehade, who Israel said was responsible for hundreds of civilian deaths. The attack also killed 14 others (including his wife and 9 children). It had targeted the building in which Shahade was hiding in Gaza City. It also wounded some 150 Palestinians, according to the complaint (or 50, according to other reports). The Israeli chief of operations and prime minister apologized officially, saying they were unaware, due to faulty intelligence, that civilians would be in the house. A regretful Ya'alon also mentioned that the army had passed up on several earlier opportunities to kill Shehade, because he was with his wife or children, and that each time Shehadeh went on to direct more suicide bombings against Israel. The investigation in the case was halted on 30 June 2009 by a decision of a panel of 18 judges of the Audiencia Nacional. The Spanish Court of Appeals rejected the lower court's decision, and on appeal in April 2010 the Supreme Court of Spain upheld the Court of Appeals decision against conducting an official inquiry into the IDF's targeted killing of Shehadeh.

Australia

The High Court of Australia confirmed the authority of the Australian Parliament, under the Australian Constitution, to exercise universal jurisdiction over War Crimes in the Polyukhovich v CommonwealthPolyukhovich v Commonwealth

Polyukovich v The Commonwealth [1991] HCA 32; 172 CLR 501, commonly referred to as the War Crimes Act Case, was a significant case decided in the High Court of Australia regarding the scope of the external affairs power in section 51 of the Constitution and the judicial power of the...

case of 1991. It is illegal for any Australian citizen or resident to engage in sexual relations with anyone under 16 years of age, anywhere in the world, and such an act is treated as an instance of child sex tourism

Child sex tourism

Child sex tourism is tourism for the purpose of engaging in the prostitution of children, that is commercially-facilitated child sexual abuse...

, a severe crime punishable by a term of imprisonment of up to 17 years; this applies even in jurisdictions where such acts are legal because the age of consent

Age of consent

While the phrase age of consent typically does not appear in legal statutes, when used in relation to sexual activity, the age of consent is the minimum age at which a person is considered to be legally competent to consent to sexual acts. The European Union calls it the legal age for sexual...

is lower than 16.

United Kingdom

An offence is generally only triable in the jurisdiction where the offence took place, unless a specific statute enables the UK to exercise extraterritorial jurisdiction. This is the case for:- Sexual offences against children (s. 72 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003Sexual Offences Act 2003The Sexual Offences Act 2003 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland that was passed in 2003 and became law on 1 May 2004.It replaced older sexual offences laws with more specific and explicit wording...

) - Murder and manslaughter (ss. 9 and 10 of the Offences Against the Person Act 1861Offences Against The Person Act 1861The Offences against the Person Act 1861 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It consolidated provisions related to offences against the person from a number of earlier statutes into a single Act...

) - Fraud and dishonesty (Criminal Justice Act 1993Criminal Justice Act 1993The Criminal Justice Act 1993 is a United Kingdom Act of Parliament that set out new rules regarding drug trafficking, proceeds and profit of crime, financing of terrorism and insider dealing.-External links:**...

Part 1) - Terrorism (ss. 59, 62-63 of the Terrorism Act 2000Terrorism Act 2000The Terrorism Act 2000 is the first of a number of general Terrorism Acts passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It superseded and repealed the Prevention of Terrorism Act 1989 and the Northern Ireland Act 1996...

) - Bribery (s. 109 of the Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001The Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 was formally introduced into the Parliament of the United Kingdom on 19 November 2001, two months after the terrorist attacks on New York on 11 September. It received royal assent and came into force on 14 December 2001...

)

In December 2009 a court in London issued an arrest warrant for Tzipi Livni

Tzipi Livni

Tzipporah Malkah "Tzipi" Livni is an Israeli lawyer and politician. She is the current Israeli Opposition Leader and leader of Kadima, the largest party in the Knesset. Raised an ardent nationalist, Livni has become one of her nation's leading voices for the two-state solution. In Israel she has...

in connection with accusations of war crimes in the Gaza Strip during Operation Cast Lead (2008–2009). The warrant was issued on 12 December and revoked on 14 December 2009 after it was revealed that Livni had not entered British territory. The warrant was later denounced as "cynical" by the Israeli foreign ministry, while Livni's office said she was "proud of all her decisions in Operation Cast Lead". Livni herself called the arrest warrant "an abuse of the British legal system".

Similarly a January visit to Britain by a team of Israel Defense Force (IDF) was cancelled over concerns that arrest warrants would be sought by pro-Palestinian advocates in connection with allegations of war crimes under laws of universal jurisdiction.

Further reading

- Köchler, HansHans KöchlerHans Köchler is a professor of philosophy at the University of Innsbruck, Austria, and president of the International Progress Organization, a non-governmental organization in consultative status with the United Nations...

, Global Justice or Global Revenge? International Criminal Justice at the CrossroadsGlobal Justice or Global RevengeGlobal Justice or Global Revenge? International Criminal Justice at the Crossroads is a book by Austrian philosopher Hans Köchler, who was appointed by the United Nations as observer of the Lockerbie bombing trial in the Netherlands...

(2003) - Lyal S. Sunga, The Emerging System of International Criminal Law: Developments in Codification and Implementation. Kluwer, 1997, 508 pp. ISBN 90-411-0472-0

- Lyal S. Sunga, Individual Responsibility in International Law for Serious Human Rights Violations. Nijhoff, 1992, 252 pp. ISBN 0-7923-1453-0

- Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs Diane Morrison and Justus Reid Weiner Curbing the Manipulation of Universal Jurisdiction

See also

- Actio popularisActio popularisAn actio popularis was an action in Roman penal law brought by a member of the public in the interest of public order.The action exists in some modern legal systems. For example, in Spain, an actio popularis was accepted by Judge Garzón in June 1996 which charged that certain Argentine military...

- Rule of Law in Armed Conflicts Project (RULAC)Rule of Law in Armed Conflicts Project (RULAC)The Rule of Law in Armed Conflicts Project is an initiative of the to support the application and implementation of the international law of armed conflict.-Overview:...

- Targeted killingTargeted killingTargeted killing is the deliberate, specific targeting and killing, by a government or its agents, of a supposed terrorist or of a supposed "unlawful combatant" who is not in that government's custody...

External links

- Macedo, Stephen (project chair and editor). The Princeton principles on Universal Jurisdiction, The Princeton Project on Universal Jurisdiction, Princeton UniversityPrinceton UniversityPrinceton University is a private research university located in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. The school is one of the eight universities of the Ivy League, and is one of the nine Colonial Colleges founded before the American Revolution....

, 2001, ISBN 0-9711859-0-5 - Legal Remedies for Victims of "International Crimes": Fostering an EU Approach To Extraterritorial Jurisdiction The Redress Trust and the International Federation of Human RightsInternational Federation of Human RightsThe International Federation for Human Rights is a non-governmental federation for human rights organizations. Founded in 1922, FIDH is the oldest international human rights organisation worldwide and today brings together 164 member organisations in over 100 countries.FIDH is nonpartisan,...

, March 2004 - Kissinger, Henry, The Pitfalls of Universal Jurisdiction: Risking Judicial Tyranny –, Foreign Affairs, July/August 2001.

- The AU-EU Expert Report on the Principle of Universal Jurisdiction, 16 April 2009.