Aegean Macedonians

Encyclopedia

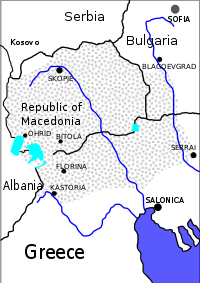

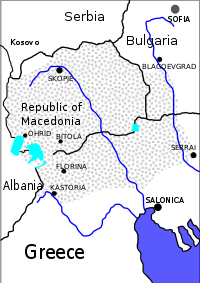

Slavic speakers are a linguistic minority population in the northern Greek region

of Macedonia who are mostly concentrated in certain parts of the peripheries

of West

and Central Macedonia

, adjacent to the territory of the Republic of Macedonia

. A smaller group exists in East Macedonia adjacent to the territory of Bulgaria

. Some members have formed their own emigrant communities in the neighbouring countries, as well as further abroad.

Predominantly identified as Macedonian Bulgarians until the early 1940s, since the formation of a Macedonian nation state, many of the migrant population in the diaspora (Australia, America and Canada) have a strong Macedonian identity and have followed the consolidation of the Macedonian

ethnicity.

However, those who remain in Greece, now mainly identify nationally as ethnic Greeks, although, it should be noted, that though the Macedonian region is overwhelmingly inhabited by Greeks including descendants of Pontians

, it is ethnically diverse (including Albanians

, Aromanians

and Slavs).

The second group in today's Greece

is made up of those who seem to reject any national identity, but have distinct regional ethnic identity, which they may call “indigenous” - dopia -, Slavomacedonian, or Macedonian, and the smallest group is made up of those who have a clear ethnic Macedonian national identity

. They speak East South Slavic dialects that can be linguistically classified as either Macedonian

or Bulgarian

, but which are locally often referred to simply as "Slavic" or "'the local language". Today all speakers are also bilingual in Greek.

A crucial element of that controversy is the very name Macedonian, as it is also used by a much more numerous group of people with a Greek national identity to indicate their regional identity. The term "Aegean Macedonians" is associated with those parts of the population that have an ethnic Macedonian identity. Speakers who identify as Greeks or have distinct regional ethnic identity, often speak of themselves simply as "locals" , to distinguish themselves from native Greek speakers from the rest of Greece and Greek refugees from Asia Minor who entered the area in the 1920s and after.

Slavic speakers will also use the term "Macedonians" or "Slavomacedonians", though in a regional rather than an ethnic sense. People of Greek persuasion are sometimes called by the pejorative term "Grecomans

" by the other side. Greek sources, which usually avoid the identification of the group with the nation of the Republic of Macedonia, and also reject the use of the name "Macedonian" for the latter, will most often refer only to so called "Slavophones" or "Slavophone Greeks".

"Slavic-speakers" or "Slavophones" is also used as a cover term for people across the different ethnic orientations. The exact number of the linguistic minority remaining in Greece today, together with its members' choice of ethnic identification, is difficult to ascertain; most maximum estimates range around 180,000-200,000 with those of an ethnic Macedonian national consciousness numbering possibly 10,000 to 30,000. However, as per leading experts on this issue, the number of this people has decreased in the last decades, because of the intermeriages and the urbanization and they number nowadays between 50,000 and 70,000 people with around 10,000 of them identifying as Macedonians.

The Slavs

The Slavs

took advantage of the desolation left by the nomadic tribes and in the 6th century settled the Balkan Peninsula. Aided by the Avars

and the Bulgars

, the Slavic tribes started in the 6th century a gradual invasion into the Byzantine lands.

They invaded Macedonia and reached as far south as Thessaly and the Peloponnese

, settling in isolated regions that were called by the Byzantines Sclavinias, until they were gradually pacified.

At the beginning of the 9th century, the Slavic Bulgarian Empire

conquered Northern Byzantine lands, including most of Macedonia. Those regions remained under Bulgarian rule for two centuries, until conquest of Bulgaria by the Byzantine Emperor of the Macedonian dynasty Basil II

in 1018.

In the 13th and the 14th century, Macedonia was contested by the Byzantine Empire, the Latin Empire

, Bulgaria and Serbia but the frequent shift of borders did not result in any major population changes. In 1338, it was conquered by the Serbian Empire

, but after the Battle of Maritsa

in 1371 most of the Macedonian Serbian lords would accept supreme Ottoman rule.

During the Middle Ages Slavs in South Macedonia were mostly defined as Bulgarians, and this continued also during 16th and 17th centuries by Ottoman historians and travellers like Hoca Sadeddin Efendi

, Mustafa Selaniki

, Hadji Khalfa and Evliya Celebi

. Nevertheless, most of the Slavic-speakers had not formed a national identity

in modern sense and were instead identified through its religious affiliations.

Some Slavic-speakers have also converted to Islam

. This conversion appears to have been a gradual and voluntary process. Economic and social gain was an incentive to become a Muslim. Muslims also enjoyed some legal privileges.

Nevertheless the rise of European nationalism in the 18th century led to the expansion of the Hellenic idea in Macedonia and under the influence of the Greek schools and the Patriarchate of Constantinople, and part from the urban Christian population of Slavic origin started to view itself more as Greek.

In the Bulgarian Archbishopric of Ohrid

the Slavonic liturgy was preserved on the lower levels until its abolition in 1767. This led to the first literary work in vernacular modern Bulgarian, History of Slav-Bulgarians

in 1762. Its author was a Macedonia-born monk Paisius of Hilendar

, who wrote it in the Bulgarian Orthodox

Zograf Monastery

, on Mount Athos

.

Nevertheless it took almost a century for the Bulgarian idea to regain ascendancy in the region. Paisius was the first ardent call for a national awakening and urged his compatriots to throw off the subjugation to the Greek language and culture. The example of Paissiy was followed also by other Bulgarian awakeners in 18th century Macedonia.

The Macedonian Bulgarians took active part in the long struggle for independent Bulgarian Patriarchate and Bulgarian schools during the 19th century. The foundation of the Bulgarian Exarchate (1870) aimed specifically at differentiating the Bulgarian from the Greek population on an ethnic and linguistic basis, hence providing the conditions for the open assertion of a Bulgarian national identity.

On the other hand the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization (IMARO) was founded in 1893 in Ottoman Thessaloniki

by several Bulgarian Exarchate teachers and professionals who sought to create a militant movement dedicated to the autonomy of Macedonia and Thrace within the Ottoman Empire. Many Bulgarian exarchists

participated in the Ilinden Uprising in 1903 with hope of liberation from the Porte.

From 1900 onwards, the danger of Bulgarian control had upset the Greeks. The Bishop of Kastoria

, Germanos Karavangelis

, realised that it was time to act in a more efficient way and started organising Greek opposition. Germanos animated the Greek population against the IMORO and formed committees to promote the Greek interests.

Taking advantage of the internal political and personal disputes in IMORO, Karavangelis succeeded to organize guerrilla groups. Fierce conflicts between the Greeks and Bulgarians started in the area of Kastoria, in the Giannitsa

Lake and elsewhere; both parties committed cruel crimes.

Both guerrilla groups had also to confront the Turkish army. These conflicts ended after the revolution of "Young Turks

" in 1908, as they promised to respect all ethnicities and religions and generally to provide a constitution.

After the Balkan Wars

in 1913, Greece took control of southern Macedonia and began an official policy of forced assimilation

which included the settlement of Greeks from other provinces into southern Macedonia, as well as the linguistic and cultural Hellenization

of Slav speakers. which continued even after World War I

.

The Greeks expelled Exarchist churchmen and teachers and closed Bulgarian schools and churches. Bulgarian language (including the Macedonian dialects) was prohibited, and its surreptitious use, whenever detected, was ridiculed or punished.

Bulgaria's entry into World War I on the side of the Central Powers

signified a dramatic shift in the way European public opinion viewed the Bulgarian population of Macedonia. The ultimate victory of the Allies

in 1918 led to the victory of the vision of the Slavic population of Macedonia as an amorphous mass, without a developed national consciousness.

Within Greece, the ejection of the Bulgarian church, the closure of Bulgarian schools, and the banning of publication in Bulgarian language, together with the expulsion or flight to Bulgaria of a large proportion of the Macedonian Bulgarian intelligentsia, served as the prelude to campaigns of forcible cultural and linguistic assimilation.

The remaining Macedonian Bulgarians were classified as "Slavophones". After the Ilinden Uprising, the Balkan Wars and especially after the First World War more than 100,000 Bulgarians from Aegean Macedonia moved to Bulgaria.

There was agreement in 1919 between Bulgaria and Greece which provided opportunities to expatriate the Bulgarians from Greece. Until the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922) and the Population exchange between Greece and Turkey

in 1923 there were also some Pomak communities in the region.

During the Balkan Wars IMRO members joined the Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Volunteer Corps

During the Balkan Wars IMRO members joined the Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Volunteer Corps

and fought with the Bulgarian Army. Others with their bands assisted the Bulgarian army with its advance and still others penetrated as far as the region of Kastoria, southwestern Macedonia.

In the Second Balkan War IMRO bands fought the Greeks behind the front lines but were subsequently routed and driven out. The result of the Balkan Wars was that the Macedonian region was partitioned between Bulgaria, Greece, Serbia. IMARO maintained its existence in Bulgaria, where it played a role in politics by playing upon Bulgarian irredentism

and urging a renewed war.

During the First World War in Macedonia

(1915–1918) the organization supported Bulgarian army and joined to Bulgarian war-time authorities. Bulgarian army, supported by the organization's forces, was successful in the first stages of this conflict, came into positions on the line of the pre-war Greek-Serbian border.

The Bulgarian advance into Greek held Eastern Macedonia, precipitated internal Greek crisis. The government ordered its troops in the area not to resist, and most of the Corps was forced to surrender. However the post-war Treaty of Neuilly

again denied Bulgaria what it felt was its share of Macedonia. From 1913 to 1926 there were large-scale changes in the population structure due to ethnic migrations.

During and after the Balkan Wars about 15,000 Slavs left the new Greek territories for Bulgaria but more significant was the Greek–Bulgarian convention 1919 in which some 72,000 Slavs-speakers left Greece for Bulgaria, mostly from Eastern Macedonia, which from then remained almost Slav free.

IMRO began sending armed bands into Greek Macedonia to assassinate officials. In 1920s in the region of Greek Macedonia 24 chetas and 10 local reconnaissance detachments were active. Many locals were repressed by the Greek authorities on suspicions of contacts with the revolutionary movement.

In this period the combined Macedonian-Adrianopolitan revolutionary movement separated into Internal Thracian Revolutionary Organization and Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization. ITRO was a revolutionary organization active in the Greek regions of Thrace

and Eastern Macedonia to the river Strymon

. The reason for the establishment of ITRO was the transfer of the region from Bulgaria to Greece in May 1920.

At the end of 1922, the Greek government started to expel large numbers of Thracian Bulgarians

into Bulgaria and the activity of ITRO grew into an open rebellion. Meanwhile, the left-wing did form the new organisation called IMRO (United) in 1925 in Vienna

. However, it did not have real popular support and remained based abroad with, closely linked to the Comintern

and the Balkan Communist Federation

.

IMRO's and ITRO's constant fratricidal killings and assassinations abroad provoked some within Bulgarian military after the coup of 19 May 1934 to take control and break the power of the organizations, which had come to be seen as a gangster organizations inside Bulgaria and a band of assassins outside it.

and Petrich incidents

triggered heavy protests in Bulgaria and international outcry against Greece. The Common Greco-Bulgarian committee for emigration investigated the incident and presented its conclusions to League of Nations

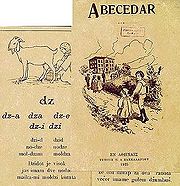

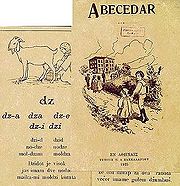

in Geneva. As a result a bilateral Bulgarian-Greek agreement was signed in Geneva on September 29, 1925 known as Politis-Kalfov protocol after the demand of the League of Nations, recognizing Greek slavophones as Bulgarians and guaranteeing their protection. Next month a Slavic language primer textbook in Latin known as Abecedar

published by the Greek ministry for education, was introduced to Greek schools of Aegean Macedonia. On February 2, 1925, the Greek parliament, under pressure from Serbia

, rejected ratification of the 1913 Greek-Serbian Coalition Treaty. Agreement lasted 9 months until June 10, 1925 when League of Nations annulled it.

During the 1920s the Comintern developed a new policy for the Balkans, about collaboration between the communists and the Macedonian movement. The idea for a new unified organization was supported by the Soviet Union

, which saw a chance for using this well developed revolutionary movement to spread revolution in the Balkans. In the so-called May Manifesto of 6 May 1924, for first time the objectives of the unified Slav Macedonian liberation movement were presented: "independence and unification of partitioned Macedonia, fighting all the neighbouring Balkan monarchies, forming a Balkan Communist Federation

". In 1934 the Comintern issued also a resolution about the recognition of the Slav Macedonian ethnicity. In this period Slavic Macedonian nationalism began to arise. This decision was supported by the Greek Communist Party.

The Situation for Slav-speakers became unbearable when the Metaxas regime

took power in 1936. Metaxas was firmly opposed to the irredentist factions of the Slavophones of northern Greece mainly in Macedonia and Thrace, some of whom underwent political persecution due to advocacy of irredentism with regard to neighboring countries. Place names and surnames were officially Hellenized and the native Slavic dialects were banned even in personal use. It was during this time that many Slavic-speakers fled their homes and immigrated to the United States

, Canada

and Australia

. The name changes took place across other neighbouring states, according to the predominant language.

Ohrana were armed detachments organized by the Bulgarian army, composed of pro-Bulgarian oriented part of the Slavic population in occupied Greek Macedonia during World War II

Ohrana were armed detachments organized by the Bulgarian army, composed of pro-Bulgarian oriented part of the Slavic population in occupied Greek Macedonia during World War II

, led by Bulgarian officers.

In 1941 Greek Macedonia was occupied by German, Italian and Bulgarian troops. The Bulgarian troops occupied the whole of Eastern Macedonia and Western Thrace, where it was greeted from the greater part of a Slav-speakers as liberators. At the beginning of the occupation in Greece most of the Slavic-speakers in the area felt themselves to be Bulgarians. Only a small part espoused a pro-Hellenic feelings.

Unlike Germany and Italy, Bulgaria officially annexed the occupied territories, which had long been a target of Bulgarian irridentism

. A massive campaign of "Bulgarisation

" was launched, which saw all Greek officials deported. This campaign was successful especially in Eastern and later in Central Macedonia, when Bulgarians entered the area in 1943, after Italian withdrawal from Greece.

All Slav-speakers there were regarded as Bulgarians and not so effective in German-occupied Western Macedonia. A ban was placed on the use of the Greek language, the names of towns and places changed to the forms traditional in Bulgarian.

In addition, the Bulgarian government tried to alter the ethnic composition of the region, by expropriating land and houses from Greeks in favour of Bulgarian settlers. The same year, the German High Command approved the foundation of a Bulgarian military club in Thessaloníki.

The Bulgarians organized supplying of food and provisions for the Slavic population in Central and Western Macedonia, aiming to gain the local population that was in the German and Italian occupied zones. The Bulgarian clubs soon started to gain support among parts of the population.

Many Communist political prisoners were released with the intercession of Bulgarian Club in Thessaloniki, which had made representations to the German occupation authorities. They all declared Bulgarian ethnicity.

In 1942, the Bulgarian club asked assistance from the High command in organizing armed units among the Slavic-speaking population in northern Greece. For this purpose, the Bulgarian army, under the approval of the German forces in the Balkans sent a handful of officers from the Bulgarian army, to the zones occupied by the Italian and German troops to be attached to the German occupying forces as "liaison officers". All the Bulgarian officers brought into service were locally born Macedonians who had immigrated to Bulgaria with their families during the 1920s and 1930s as part of the Greek-Bulgarian Treaty of Neuilly which saw 90,000 Bulgarians migrating to Bulgaria from Greece.

These officers were given the objective to form armed Bulgarian militias. Bulgaria was interested in acquiring the zones under Italian and German occupation and hopped to sway the allegiance of the 80,000 Slavs who lived there at the time. The appearance of Greek partisans in those areas persuaded the Italians to allow the formation of these collaborationist detachments. Following the defeat of the Axis powers and the evacuation of the Nazi occupation forces many members of the Ohrana joined the SNOF where they could still pursue their goal of secession.

The advance of the Red Army

into Bulgaria in September 1944, the withdrawal of the German armed forces from Greece in October, meant that the Bulgarian Army had to withdraw from Greek Macedonia and Thrace. There was a rapprochement between the Greek Communist Party and the Ohrana collaborationist units.

Further collaboration between the Bulgarian-controlled Ohrana and the EAM controlled SNOF followed when it was agreed that Greek Macedonia would be allowed to secede. Finally it is estimated that entire Ohrana units had joined the SNOF which began to press the ELAS leadership to allow it autonomous action in Greek Macedonia.

There had been also a larger flow of refugees into Bulgaria as the Bulgarian Army pulled out of the Drama-Serres region in late 1944. A large proportion of Bulgarians and Slavic speakers emigrated there. In 1944 the declarations of Bulgarian nationality were estimated by the Greek authorities, on the basis of monthly returns, to have reached 16,000 in the districts of German-occupied Greek Macedonia, but according to British sources, declarations of Bulgarian nationality throughout Western Macedonia reached 23,000.

During the beginning of the Second World War, Greek Slavic-speaking citizens fought within the Greek army until the country was overrun in 1941. The Greek communists had already been influenced by the Comintern and it was the only political party in Greece to recognize Macedonian national identity. As result many Slavic-speakers joined the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) and participated in partisan activities. The KKE expressed its intent to "fight for the national self-determination of the repressed Macedonians".

During the beginning of the Second World War, Greek Slavic-speaking citizens fought within the Greek army until the country was overrun in 1941. The Greek communists had already been influenced by the Comintern and it was the only political party in Greece to recognize Macedonian national identity. As result many Slavic-speakers joined the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) and participated in partisan activities. The KKE expressed its intent to "fight for the national self-determination of the repressed Macedonians".

In 1943, the Slavic-Macedonian National Liberation Front (SNOF) was set up by ethnic Macedonian members of the KKE. The main aim of the SNOF was to obtain the entire support of the local population and to mobilize it, through SNOF, for the aims of the National Liberation Front (EAM). Another major aim was to fight against the Bulgarian organisation Ohrana

and Bulgarian authorities.

During this time, the ethnic Macedonians in Greece were permitted to publish newspapers in the Macedonian language and run schools. In late 1944 after the German and Bulgarian withdrawal from Greece, the Josip Broz Tito

's Partisans

movement hardly concealed its intention of expanding.

It was from this period that Slav-speakers in Greece who had previously referred to themselves as "Bulgarians" increasingly began to identify as "Macedonians".

By 1945 World War II had ended and Greece was in open civil war. It has been estimated that after the end of the Second World War over 20,000 people fled from Greece to Bulgaria. To an extent the collaboration of the peasants with the Germans, Italians, Bulgarians or ELAS

was determined by the geopolitical position of each village.

Depending upon whether their village was vulnerable to attack by the Greek communist guerrillas or the occupation forces, the peasants would opt to support the side in relation to which they were most vulnerable. In both cases, the attempt was to promise "freedom" (autonomy or independence) to the formerly persecuted Slavic minority as a means of gaining its support.

The National Liberation Front (NOF) was organized by the political and military groups of the Slavic minority in Greece, active from 1945-1949. The interbellum was the time when part of them came to the conclusion that they are Macedonians. Greek hostility to the Slavic minority produced tensions that rose to separatism.

After the recognition in 1934 from the Comintern

of the Macedonian ethnicity, the Greek communists also recognized Macedonian national identity. That separatism was reinforced by Communist Yugoslavia's support, since Yugoslavia's new authorities after 1944 encouraged the growth of Macedonian national consciousness.

Following World War II, the population of Yugoslav Macedonia did begin to feel themselves to be Macedonian, assisted and pushed by a government policy. Communist Bulgaria also began a policy of making Macedonia connecting link for the establishment of new Balkan Federative Republic and stimulating in Bulgarian Macedonia a development of distinct Slav Macedonian consciousness. This inconsistent Bulgarian policy has thrown most independent observers ever since into a state of confusion as to the real origin of the population in Bulgarian Macedonia.

At first, the NOF organized meetings, street and factory protests and published illegal underground newspapers. Soon after it founding, members began forming armed partisan detachments. In 1945, 12 such groups were formed in Kastoria, 7 in Florina, and 11 in Edessa

and the Gianitsa region. Many Aromanians

also joined the Macedonians in NOF, especially in the Kastoria region. The NOF merged with the Democratic Army of Greece

(DSE) which was the main armed unit supporting the Communist Party.

Owing to the KKE's equal treatment of ethnic Macedonians and Greeks, many ethnic Macedonians enlisted as volunteers in the DSE (60% of the DSE was composed of Slavic Macedonians). It was during this time that books written in the Macedonian dialect (the official language was in process of codifying) were published and Macedonians cultural organizations theatres were opened.

According to information announced by Paskal Mitrovski on the I plenum of NOF on August 1948, about 85% of the Slavic-speaking population in Greek Macedonia had an ethnic Macedonian self-identity. It has been estimated that out of DSE's 20,000 fighters, 14,000 were Slavic Macedonians from Greek Macedonia.

Given their important role in the battle, the KKE changed its policy towards them. At the fifth Plenum of KKE on January 31, 1949, a resolution was passed declaring that after KKE's victory, the Slavic Macedonians would find their national restoration as they wish

The DSE was slowly driven back and eventually defeated. Thousands of Slavic-speakers were expelled and fled to the newly established Socialist Republic of Macedonia

The DSE was slowly driven back and eventually defeated. Thousands of Slavic-speakers were expelled and fled to the newly established Socialist Republic of Macedonia

, while thousands more children took refuge in other Eastern Bloc

countries.

They are known as Децата бегалци/Decata begalci. Many of them made their way to the US, Canada and Australia. Other estimates claim that 5,000 were sent to Romania, 3,000 to Czechoslovakia, 2,500 to Bulgaria, Poland and Hungary and a further 700 to East Germany.

There are also estimations that 52,000 - 72,000 people in total (incl. Greeks) were evacuated from Greece, whereas Macedonian

sources claim up to 213,000 Slavic speakers fled Greece at the end of the Civil War.

However a 1951 document from the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

states the total number of ethnic Macedonian and Greeks arriving from Greece between the years 1941–1951 is 28,595.

From 1941 until 1944 500 found refuge in the People's Republic of Macedonia, in 1944 4,000 people, in 1945 5,000 , in 1946 8,000, in 1947 6,000, in 1948 3,000, in 1949 2,000, in 1950 80, and in 1951 15 people. About 4,000 left Yugoslavia and moved to other Socialist countries (and very few went also to western countries).

So in 1951 at Yugoslavia were 24,595 refuges from Greek Macedonia. 19,000 lived in Yugoslav Macedonia, 4,000 in Serbia (mainly in Gakovo-Krusevlje) and 1595 in other Yugoslav republics.

This data is confirmed by the KKE

, which claims that the total number of political refugees from Greece (incl. Greeks) was 55,881.

This was brought to a forefront shortly after the independence of the Republic of Macedonia in 1991. Many ethnic Macedonians have been refused entry to Greece because their documentation listed the Slavic names of the places of birth as opposed to the now-official new Greek names, despite the child refugees, now elderly, only knowing their village by the local Macedonian name. These measures were even extended to Australian and Canadian citizens. Despite this, there have been sporadic periods of free entry most of which have only ever lasted a few days.

Despite the removal of official recognition to those identifying as ethnic Macedonians after the end of the Greek Civil War

, a 1954 letter from the Prefect of Florina

, K. Tousildis, reported that people were still affirming that the language they spoke was Macedonian in forms relating to personal documents, birth and marriage registries, etc.

In January 1994, Rainbow was founded as the political party to represent the ethnic Macedonian minority. At the 1994 European Parliament election the party received 7,263 votes and polled 5.7% in the Florina district. The party opened its offices in Florina on September 6, 1995. The opening of the office faced strong hostility and that night the offices had been ransacked. In 1997 the "Zora" first began to published and the following year, the Second All-Macedonian congress was held in Florina. Soon after the "Makedoniko" magazine also began to be published.

In January 1994, Rainbow was founded as the political party to represent the ethnic Macedonian minority. At the 1994 European Parliament election the party received 7,263 votes and polled 5.7% in the Florina district. The party opened its offices in Florina on September 6, 1995. The opening of the office faced strong hostility and that night the offices had been ransacked. In 1997 the "Zora" first began to published and the following year, the Second All-Macedonian congress was held in Florina. Soon after the "Makedoniko" magazine also began to be published.

In 2001 the first Macedonian Orthodox Church

In 2001 the first Macedonian Orthodox Church

in Greece was founded in the Aridaia

region, which was followed in 2002 with the election of Rainbow Candidate, Petros Dimtsis, to office in the Florina prefecture

. The year also saw the "Loza" magazine go into print. In the following years several Macedonian language radio stations were established, however many including "Makedonski Glas" , were shut down by Greek authorities. During this period ethnic Macedonians such as Kostas Novakis

, began to record and distribute music in the native Macedonian dialects. Ethnic Macedonian activists reprinted the language primer Abecedar , in attempt to encourage further use of the Macedonian language. However, the lack of Macedonian language literature has left many young ethnic Macedonian students dependant on textbooks from the Republic of Macedonia. In 2008 hundreds of ethnic Macedonians from the villages of Lofoi, Meliti

, Kella and Vevi

protested against the presence of the Greek military in the Florina region.

Another ethnic Macedonian organisation, the Educational and Cultural Movement of Edessa , was formed in 2009. Based in Edessa

, the group focuses on promoting ethnic Macedonian culture, through the publication of books and CD's, whilst also running Macedonian language courses and teaching the Macedonian Cyrillic alphabet. Since then Macedonian language courses have been extended to include Florina

and Salonika. Later that year Rainbow officially opened its second office in the town of Edessa

.

In early 2010 several Macedonian language newspapers were put into print for the first time. In early 2010 the Zadruga newspapers was first published, This was shortly followed by the publication of the "Nova Zora" newspaper in May 2010. The estimated readership of Nova Zora is 20,000, whilst that of Zadrgua is considerably smaller. The "Krste Petkov Misirkov Foundation" was established in 2009, which aims to establish a museum dedicated to ethnic Macedonians of Greece, whilst also cooperating with other Macedonian minorities in neighbouring countries. The foundations aims at catalouging ethnic Macedonian culture in Greece along with promoting the Macedonian language.

In 2010 another group of ethnic Macedonians were elected to office, including the outspoken mayor of Meliti

, Pando Ašlakov. Ethnic Macedonians have also been elected as mayors in the towns of Vevi

, Pappagiannis, Neochoraki and Achlada

. Later that year the first Macedonian-Greek dictionary was launched by ethnic Macedonian activits in both Brussels and Athens.

with personal and topographic names forcibly changed to Greek versions

and Cyrillic inscriptions across Northern Greece being removed from gravestones and churches.

Under the regime of Ioannis Metaxas

the situation for Slavic speakers became intolerable, causing many to emigrate. A law was passed banning local Macedonian language. Many people who broke the rule were deported to the islands of Thasos

and Cephalonia. Others were arrested, fined, beaten and forced to drink castor oil., or even deported to the border regions in Yugoslavia

following a staunch government policy of chasing minorities.

During the Greek Civil War

, areas under Communist control freely taught the newly codified Macedonian language

. Throughout this period it is claimed that the ethnic Macedonian culture and language flourished. Over 10,000 children went to 87 schools, Macedonian language newspapers were printed and theatres opened. As the National forces approached, these facilities were either shut down or destroyed. People feared oppression and the loss of their rights under the rule of the National government, which in turn caused many people to flee Greece. However, the Greek Communists were defeated in the civil war, their Provisional Government was exiled, and tens of thousands of Slavic-speakers were expelled from Greece. Many fled in order to avoid persecution from the ensuing National army. Those who fled during the Greek Civil War were stripped of their Greek Citizenship and property. Although these refugees have been classed as political refugees, there have been claims that they were also targeted due to their ethnic and cultural identities.

During the Cold War cases of discrimination against people who identified as ethnic Macedonians and the Macedonian language had been reported by Human Rights Watch/Helsinki. In 1959 it was reported that the inhabitants of three villages adopted a 'language oath', renouncing their Slavic dialect. According to Riki Van Boeschoten, this "peculiar ritual" took place "probably on the initiative of local government officials."

Greece has blocked attempts by ethnic Macedonians to establish a Home of Macedonian Culture despite being convicted for a violation of freedom of association by the European Court of Human Rights.

language, depending on the origin of the song. However, this was not always the case an in 1993 the Greek Helsink Monitor found that the Greek government refused in "the recent past to permit the performance of [ethnic] Macedonian songs and dances". In recent years however these restrictions have been lifted and once again Macedonian songs are performed freely at festivals and gatherings across Greece.

Many songs originating Greek Macedonia such as "Filka Moma" have become popular in the neighbouring Republic of Macedonia

. Whilst likewise many songs composed by artists from the Republic of Macedonia such as "Egejska Maka" by Suzana Spasovska, "Makedonsko devojče" by Jonče Hristovski

, and "Kade ste Makedončinja?" are also widely sung in Greece. In recent years many ethnic Macedonian performers including Elena Velevska

, Suzana Spasovska, Ferus Mustafov

, Group Synthesis

and Vaska Ilieva

, have all been invited to perform in amongst ethnic Macedonians in Greece. Likewise ethnic Macedonian performers from Greece such as Kostas Novakis

also perform in the Republic of Macedonia. Many performers who live in the diaspora often return to Greece to perform Macedonian songs, including Marija Dimkova.

The first Macedonian language in Greece media emerged in the 1940s. The "Crvena Zvezda" newspaper first published in 1942 in the local Solun-Voden dialect

The first Macedonian language in Greece media emerged in the 1940s. The "Crvena Zvezda" newspaper first published in 1942 in the local Solun-Voden dialect

, is often credited as the first Macedonian language newspaper to be published in Greece. This was soon followed by the publication of many others including, "Edinstvo" (Unity), "Sloveno-Makedonski Glas", "Nova Makedonka", "Freedom" (Freedom), "Pobeda" (Victory), "Prespanski Glas", "Iskra" (Spark), "Stražar" and others. Most of these newspapers were written in the codified Macedonian language

or the local Macedonian dialects. The Nepokoren newspaper was issued from May 1, 1947 until August 1949, and served as a later example of Macedonian language

media in Greece. It was affiliated with the National Liberation Front, which was the military organisation of the Ethnic Macedonian minority in Greece. The Bilten magazine , is another example of Greek Civil War era Macedonian media.

After the Greek Civil War a ban was placed on public use of the Macedonian language, and this was reflect in the decline of all Macedonian language media. The 1990s saw a resurgence of Macedonian languge print including the publication of the "Ta Moglena", Loza, Zora and Makedoniko newspapers. This was followed with the publication of the Zadruga magazine in early 2010. Soon afterwards in May 2010 the monthly newspaper Nova Zora in May 2010, went to print. Both Zadruga and Nova Zora are published in both Macedonian and Greek, and it estimated that over 20,000 copies of Nova Zora are printed every issue.

Several Macedonian language radio stations have recently been set up in Greek Macedonia to cater for the Macedonian speaking population. These stations however, like other Macedonian language institutions in Greece have faced fierce opposition from the authorities, with one of these radio stations, "Macedonian Voice" , being shut down by authorities.

Various dialects linguistically considered to be dialects of Macedonian are spoken across Northern Greece. These dialects include the Upper

and Lower Prespa dialect

s, the Kostur

, Nestram-Kostenar

, and Solun-Voden

dialects. The Prilep-Bitola dialect

is widely spoken in the Florina

region, and forms the basis of the Standard Macedonian

language. The Ser-Drama-Lagadin-Nevrokop dialect

dialect is considered to be transitional between Macedonian and Bulgarian. The majority of the speakers also speak Greek, this trend is more prounounced amongst younger persons.

Speakers employ various terms to refer to the language which they speak. These terms include Makedonski , Slavomakedonika , Entopia , Naše , Starski and Slavika .

According to Peter Trudgill

,

During the late 19th and early 20th century Bulgarian was taught in the Bulgarian Exarchate's schools. The Abecedar language primer originally printed in 1925 was designed for speakers in using the Prilep-Bitola dialect

in the Florina area. Although the book used a latin script, it was printed in the locally Prilep-Bitola dialect

. In the 1930s the Metaxas regime banned the use of the Slavomacedonian language in public and private use. Laws were enacted banning the language, and speakers faced harsh penalties including being arrested, fined, beaten and forced to drink castor oil.

During the Axis occupation of Greece during World War II however these penalties were lifted. The Macedonian language was employed in widespread use, with Macedonian language newspapers appearing from 1942. During the period 1941-1944 within the The Bulgarian occupation zone the Bulgarian language was taught.

During the Greek Civil War

During the Greek Civil War

, the codified Macedonian language was taught in 87 schools with 10,000 students in areas of northern Greece under the control of Communist-led forces, until their defeat by the National Army

in 1949. After the war, all of these Macedonian language schools were closed down.

More recently there have been attempts to once again begin education in Macedonian. In 2009 the Educational and Cultural Movement of Edessa began to run Macedonian language courses, teaching the Macedonian Cyrillic alphabet. Macedonian language courses have also begun in Salonika, as a way of further encouraging use of the Macedonian language. These courses have since been extended to include Macedonian speakers in Florina

and Edessa

.

In 2006 the Macedonian language primer Abecedar was reprinted in an informal attempt to reintroduce Macedonian language education The Abecedar primer was reprinted in 2006 by the Rainbow, Political Party

, it was printed in Macedonian, Greek and English. In the absence of greater Macedonian language books printed in Greece, young ethnic Macedonians living in Greece use books originating from the Republic of Macedonia

Today Macedonian dialects are freely spoken in Greece however there are serious fears for the loss the language among the younger generations due to the lack of exposure to their native language. It appears however that reports of the demise of the use of the Macedonian language in Greece have been premature, with linguists such as Christian Voss asserting that the language has a "stable future" in Greece, and that the language is undergoing a "revival" amongst younger speakers. The Rainbow Party

has called for the introduction of the language in schools and for official purposes. They have been joined by others such as Pande Ašlakov, mayor of Meliti

, in calling for the language to be officially introduced into the education system.

Certain characteristics of the these dialects, along with most varieties of Spoken Macedonian

, include the changing of the suffix ovi to oj creating the words лебови> лебој (lebovi> leboj/ bread). Often the intervocalic consonants of /v/, /g/ and /d/ are lost, changing words from polovina > polojna (a half) and sega > sea (now), which also features strongly in dialects spoken in the neighbouring Republic of Macedonia

. In other phonological and morphological characteristics, they remain similar to the other South-Eastern dialects spoken in the Republic of Macedonia

and Albania

.

, former Eastern Bloc countries such as Bulgaria, as well as in other European and overseas countries.

countries. The refugees were primarily settled in deserted villages and areas across the Republic of Macedonia. A large proportion went to the Tetovo

and Gostivar

areas. Another large group was to settle in Bitola

and the surrounding areas, while refugee camps were established in Kumanovo

and Strumica

. Large enclaves of Greek refugees and their descendants can be found in the suburbs of Topansko Pole and Avtokamanda in Skopje

. Many Aegean Macedonians hold prominent positions in the Republic of Macedonia, including prime minister Nikola Gruevski

and Dimitar Dimitrov

, the former Minister of Education.

and 370 from Kastoria

resident in Australia. The group was a key supporter of the Macedonian-Australian People's League

, and since then has formed numerous emigrant organisations. There are Aegean Macedonian communities in Richmond

, Melbourne

, Manjimup

, Shepparton

, Wanneroo

and Queanbeyan

. These immigrants have established numerous cultural and social groups including the The Church of St George and the Lerin Community Centre in Shepparton and the Aegean Macedonian hall - Kotori built in Richmond along with other churches and halls being built in Queanbeyan in Manjimup. The "Macedonian Aegean Association of Australia" is the uniting body for this community in Australia. It has been estimated by scholar Peter Hill that over 50,000 Aegean Macedonians and their descendants can be found in Australia.

region. A further 6,000 ethnic Macedonians are estimated to have arrived as refugees, following the aftermath of the Greek Civil War. One of the many cultural and benevolent societies established included the "The Association of Refugee Children from Aegean Macedonia" (ARCAM) founded in 1979. The association aimed to unite former child refugees from all over the world, with branches soon established in Toronto

, Melbourne, Perth

, the Republic of Macedonia

, Slovakia

, Czech Republic

and Poland

.

were displace to Romania. An estimated 8,500 Child refugees joined by 4,000 was sent to Romania during 1948-1949. The largest of the evacuation camps was set up in the town of Tulgheş

, and here the refugees were schooled in Macedonian, Romanian, Greek and Russian.

Regions of Greece

The traditional geographic divisions of Greece were also the official administrative subdivisions of Greece until the 1987 administrative reform )...

of Macedonia who are mostly concentrated in certain parts of the peripheries

Peripheries of Greece

The current official regional administrative divisions of Greece were instituted in 1987. Although best translated into English as "regions", the transcription peripheries is sometimes used, perhaps to distinguish them from the traditional regions which they replaced. The English word 'periphery'...

of West

West Macedonia

West Macedonia is one of the thirteen regions of Greece, consisting of the western part of Greek Macedonia. It is divided into the regional units of Florina, Grevena, Kastoria, and Kozani.-Geography:...

and Central Macedonia

Central Macedonia

Central Macedonia is one of the thirteen regions of Greece, consisting of the central part of the region of Macedonia. With a population of over 1.8 million, it is the second most populous in Greece after Attica.- Administration :...

, adjacent to the territory of the Republic of Macedonia

Republic of Macedonia

Macedonia , officially the Republic of Macedonia , is a country located in the central Balkan peninsula in Southeast Europe. It is one of the successor states of the former Yugoslavia, from which it declared independence in 1991...

. A smaller group exists in East Macedonia adjacent to the territory of Bulgaria

Bulgaria

Bulgaria , officially the Republic of Bulgaria , is a parliamentary democracy within a unitary constitutional republic in Southeast Europe. The country borders Romania to the north, Serbia and Macedonia to the west, Greece and Turkey to the south, as well as the Black Sea to the east...

. Some members have formed their own emigrant communities in the neighbouring countries, as well as further abroad.

Ethnic and linguistic affiliations

Members of this group have had a number of conflicting ethnic identifications.Predominantly identified as Macedonian Bulgarians until the early 1940s, since the formation of a Macedonian nation state, many of the migrant population in the diaspora (Australia, America and Canada) have a strong Macedonian identity and have followed the consolidation of the Macedonian

Macedonians (ethnic group)

The Macedonians also referred to as Macedonian Slavs: "... the term Slavomacedonian was introduced and was accepted by the community itself, which at the time had a much more widespread non-Greek Macedonian ethnic consciousness...

ethnicity.

However, those who remain in Greece, now mainly identify nationally as ethnic Greeks, although, it should be noted, that though the Macedonian region is overwhelmingly inhabited by Greeks including descendants of Pontians

Pontic Greeks

The Pontians are an ethnic group traditionally living in the Pontus region, the shores of Turkey's Black Sea...

, it is ethnically diverse (including Albanians

Albanians

Albanians are a nation and ethnic group native to Albania and neighbouring countries. They speak the Albanian language. More than half of all Albanians live in Albania and Kosovo...

, Aromanians

Aromanians

Aromanians are a Latin people native throughout the southern Balkans, especially in northern Greece, Albania, the Republic of Macedonia, Bulgaria, and as an emigrant community in Serbia and Romania . An older term is Macedo-Romanians...

and Slavs).

The second group in today's Greece

Greece

Greece , officially the Hellenic Republic , and historically Hellas or the Republic of Greece in English, is a country in southeastern Europe....

is made up of those who seem to reject any national identity, but have distinct regional ethnic identity, which they may call “indigenous” - dopia -, Slavomacedonian, or Macedonian, and the smallest group is made up of those who have a clear ethnic Macedonian national identity

National identity

National identity is the person's identity and sense of belonging to one state or to one nation, a feeling one shares with a group of people, regardless of one's citizenship status....

. They speak East South Slavic dialects that can be linguistically classified as either Macedonian

Macedonian language

Macedonian is a South Slavic language spoken as a first language by approximately 2–3 million people principally in the region of Macedonia but also in the Macedonian diaspora...

or Bulgarian

Bulgarian language

Bulgarian is an Indo-European language, a member of the Slavic linguistic group.Bulgarian, along with the closely related Macedonian language, demonstrates several linguistic characteristics that set it apart from all other Slavic languages such as the elimination of case declension, the...

, but which are locally often referred to simply as "Slavic" or "'the local language". Today all speakers are also bilingual in Greek.

A crucial element of that controversy is the very name Macedonian, as it is also used by a much more numerous group of people with a Greek national identity to indicate their regional identity. The term "Aegean Macedonians" is associated with those parts of the population that have an ethnic Macedonian identity. Speakers who identify as Greeks or have distinct regional ethnic identity, often speak of themselves simply as "locals" , to distinguish themselves from native Greek speakers from the rest of Greece and Greek refugees from Asia Minor who entered the area in the 1920s and after.

Slavic speakers will also use the term "Macedonians" or "Slavomacedonians", though in a regional rather than an ethnic sense. People of Greek persuasion are sometimes called by the pejorative term "Grecomans

Grecomans

The term Grecomans is a pejorative used in Bulgaria, Republic of Macedonia, Romania and Albania to characterize Arvanitic, Aromanian, and Slavic-speaking Greeks. The term generally means "pretending to be a Greek" and implies a non-Greek origin...

" by the other side. Greek sources, which usually avoid the identification of the group with the nation of the Republic of Macedonia, and also reject the use of the name "Macedonian" for the latter, will most often refer only to so called "Slavophones" or "Slavophone Greeks".

"Slavic-speakers" or "Slavophones" is also used as a cover term for people across the different ethnic orientations. The exact number of the linguistic minority remaining in Greece today, together with its members' choice of ethnic identification, is difficult to ascertain; most maximum estimates range around 180,000-200,000 with those of an ethnic Macedonian national consciousness numbering possibly 10,000 to 30,000. However, as per leading experts on this issue, the number of this people has decreased in the last decades, because of the intermeriages and the urbanization and they number nowadays between 50,000 and 70,000 people with around 10,000 of them identifying as Macedonians.

History

Slavic peoples

The Slavic people are an Indo-European panethnicity living in Eastern Europe, Southeast Europe, North Asia and Central Asia. The term Slavic represents a broad ethno-linguistic group of people, who speak languages belonging to the Slavic language family and share, to varying degrees, certain...

took advantage of the desolation left by the nomadic tribes and in the 6th century settled the Balkan Peninsula. Aided by the Avars

Eurasian Avars

The Eurasian Avars or Ancient Avars were a highly organized nomadic confederacy of mixed origins. They were ruled by a khagan, who was surrounded by a tight-knit entourage of nomad warriors, an organization characteristic of Turko-Mongol groups...

and the Bulgars

Bulgars

The Bulgars were a semi-nomadic who flourished in the Pontic Steppe and the Volga basin in the 7th century.The Bulgars emerge after the collapse of the Hunnic Empire in the 5th century....

, the Slavic tribes started in the 6th century a gradual invasion into the Byzantine lands.

They invaded Macedonia and reached as far south as Thessaly and the Peloponnese

Peloponnese

The Peloponnese, Peloponnesos or Peloponnesus , is a large peninsula , located in a region of southern Greece, forming the part of the country south of the Gulf of Corinth...

, settling in isolated regions that were called by the Byzantines Sclavinias, until they were gradually pacified.

At the beginning of the 9th century, the Slavic Bulgarian Empire

First Bulgarian Empire

The First Bulgarian Empire was a medieval Bulgarian state founded in the north-eastern Balkans in c. 680 by the Bulgars, uniting with seven South Slavic tribes...

conquered Northern Byzantine lands, including most of Macedonia. Those regions remained under Bulgarian rule for two centuries, until conquest of Bulgaria by the Byzantine Emperor of the Macedonian dynasty Basil II

Basil II

Basil II , known in his time as Basil the Porphyrogenitus and Basil the Young to distinguish him from his ancestor Basil I the Macedonian, was a Byzantine emperor from the Macedonian dynasty who reigned from 10 January 976 to 15 December 1025.The first part of his long reign was dominated...

in 1018.

In the 13th and the 14th century, Macedonia was contested by the Byzantine Empire, the Latin Empire

Latin Empire

The Latin Empire or Latin Empire of Constantinople is the name given by historians to the feudal Crusader state founded by the leaders of the Fourth Crusade on lands captured from the Byzantine Empire. It was established after the capture of Constantinople in 1204 and lasted until 1261...

, Bulgaria and Serbia but the frequent shift of borders did not result in any major population changes. In 1338, it was conquered by the Serbian Empire

Serbian Empire

The Serbian Empire was a short-lived medieval empire in the Balkans that emerged from the Serbian Kingdom. Stephen Uroš IV Dušan was crowned Emperor of Serbs and Greeks on 16 April, 1346, a title signifying a successorship to the Eastern Roman Empire...

, but after the Battle of Maritsa

Battle of Maritsa

The Battle of Maritsa, or Battle of Chernomen, took place at the Maritsa River near the village of Chernomen on September 26, 1371 between the forces of the Ottoman sultan Murad I's lieutenant Lala Şâhin Paşa and the...

in 1371 most of the Macedonian Serbian lords would accept supreme Ottoman rule.

During the Middle Ages Slavs in South Macedonia were mostly defined as Bulgarians, and this continued also during 16th and 17th centuries by Ottoman historians and travellers like Hoca Sadeddin Efendi

Hoca Sadeddin Efendi

Hoca Sadeddin Efendi was an Ottoman scholar, official, and historian, a teacher of Ottoman sultan Murad III . His name is transcribed differently: Sa'd ad-Din, Sa'd al-Din, Sa’adeddin, Sadeddin, etc...

, Mustafa Selaniki

Mustafa Selaniki

Mustafa Selaniki was a Turkish scholar and chronicler, whose Tarih-i Selâniki described the Ottoman Empire of 1563–1599.- See also :*Salonica...

, Hadji Khalfa and Evliya Celebi

Evliya Çelebi

Evliya Çelebi was an Ottoman traveler who journeyed through the territory of the Ottoman Empire and neighboring lands over a period of forty years.- Life :...

. Nevertheless, most of the Slavic-speakers had not formed a national identity

National identity

National identity is the person's identity and sense of belonging to one state or to one nation, a feeling one shares with a group of people, regardless of one's citizenship status....

in modern sense and were instead identified through its religious affiliations.

Some Slavic-speakers have also converted to Islam

Islam

Islam . The most common are and . : Arabic pronunciation varies regionally. The first vowel ranges from ~~. The second vowel ranges from ~~~...

. This conversion appears to have been a gradual and voluntary process. Economic and social gain was an incentive to become a Muslim. Muslims also enjoyed some legal privileges.

Nevertheless the rise of European nationalism in the 18th century led to the expansion of the Hellenic idea in Macedonia and under the influence of the Greek schools and the Patriarchate of Constantinople, and part from the urban Christian population of Slavic origin started to view itself more as Greek.

In the Bulgarian Archbishopric of Ohrid

Bulgarian Archbishopric of Ohrid

The Archbishopric of Ochrid was an autonomous Orthodox Church under the tutelage of the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople between 1019 and 1767...

the Slavonic liturgy was preserved on the lower levels until its abolition in 1767. This led to the first literary work in vernacular modern Bulgarian, History of Slav-Bulgarians

Istoriya Slavyanobolgarskaya

Istoriya Slavyanobolgarskaya is a book by Bulgarian scholar and clergyman Saint Paisius of Hilendar...

in 1762. Its author was a Macedonia-born monk Paisius of Hilendar

Paisius of Hilendar

Saint Paisius of Hilendar or Paisiy Hilendarski was a Bulgarian clergyman and a key Bulgarian National Revival figure. He is most famous for being the author of Istoriya Slavyanobolgarskaya, the second modern Bulgarian history after the work of Petar Bogdan Bakshev from 1667, “History of Bulgaria”...

, who wrote it in the Bulgarian Orthodox

Bulgarian Orthodox Church

The Bulgarian Orthodox Church - Bulgarian Patriarchate is an autocephalous Eastern Orthodox Church with some 6.5 million members in the Republic of Bulgaria and between 1.5 and 2.0 million members in a number of European countries, the Americas and Australia...

Zograf Monastery

Zograf Monastery

The Saint George the Zograf Monastery or Zograf Monastery is a Bulgarian Orthodox monastery on Mount Athos in Greece...

, on Mount Athos

Mount Athos

Mount Athos is a mountain and peninsula in Macedonia, Greece. A World Heritage Site, it is home to 20 Eastern Orthodox monasteries and forms a self-governed monastic state within the sovereignty of the Hellenic Republic. Spiritually, Mount Athos comes under the direct jurisdiction of the...

.

Nevertheless it took almost a century for the Bulgarian idea to regain ascendancy in the region. Paisius was the first ardent call for a national awakening and urged his compatriots to throw off the subjugation to the Greek language and culture. The example of Paissiy was followed also by other Bulgarian awakeners in 18th century Macedonia.

The Macedonian Bulgarians took active part in the long struggle for independent Bulgarian Patriarchate and Bulgarian schools during the 19th century. The foundation of the Bulgarian Exarchate (1870) aimed specifically at differentiating the Bulgarian from the Greek population on an ethnic and linguistic basis, hence providing the conditions for the open assertion of a Bulgarian national identity.

On the other hand the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization (IMARO) was founded in 1893 in Ottoman Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki , historically also known as Thessalonica, Salonika or Salonica, is the second-largest city in Greece and the capital of the region of Central Macedonia as well as the capital of the Decentralized Administration of Macedonia and Thrace...

by several Bulgarian Exarchate teachers and professionals who sought to create a militant movement dedicated to the autonomy of Macedonia and Thrace within the Ottoman Empire. Many Bulgarian exarchists

Bulgarian Exarchate

The Bulgarian Exarchate was the official name of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church before its autocephaly was recognized by the Ecumenical See in 1945 and the Bulgarian Patriarchate was restored in 1953....

participated in the Ilinden Uprising in 1903 with hope of liberation from the Porte.

From 1900 onwards, the danger of Bulgarian control had upset the Greeks. The Bishop of Kastoria

Kastoria

Kastoria is a city in northern Greece in the periphery of West Macedonia. It is the capital of Kastoria peripheral unit. It is situated on a promontory on the western shore of Lake Orestiada, in a valley surrounded by limestone mountains...

, Germanos Karavangelis

Germanos Karavangelis

Germanos Karavangelis was born in Stipsi, Lesbos.He was a metropolitan bishop of Kastoria, in communion with the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, from 1900 until 1907, appointed in the name of the Greek state by the ambassador of Greece Nikolaos Mavrokordatos and was one of the main...

, realised that it was time to act in a more efficient way and started organising Greek opposition. Germanos animated the Greek population against the IMORO and formed committees to promote the Greek interests.

Taking advantage of the internal political and personal disputes in IMORO, Karavangelis succeeded to organize guerrilla groups. Fierce conflicts between the Greeks and Bulgarians started in the area of Kastoria, in the Giannitsa

Giannitsa

Giannitsa is the largest town and a former municipality in Pella regional unit, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Pella, of which it is a municipal unit...

Lake and elsewhere; both parties committed cruel crimes.

Both guerrilla groups had also to confront the Turkish army. These conflicts ended after the revolution of "Young Turks

Young Turks

The Young Turks , from French: Les Jeunes Turcs) were a coalition of various groups favouring reformation of the administration of the Ottoman Empire. The movement was against the absolute monarchy of the Ottoman Sultan and favoured a re-installation of the short-lived Kanûn-ı Esâsî constitution...

" in 1908, as they promised to respect all ethnicities and religions and generally to provide a constitution.

After the Balkan Wars

Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars were two conflicts that took place in the Balkans in south-eastern Europe in 1912 and 1913.By the early 20th century, Montenegro, Bulgaria, Greece and Serbia, the countries of the Balkan League, had achieved their independence from the Ottoman Empire, but large parts of their ethnic...

in 1913, Greece took control of southern Macedonia and began an official policy of forced assimilation

Forced assimilation

Forced assimilation is a process of forced cultural assimilation of religious or ethnic minority groups, into an established and generally larger community...

which included the settlement of Greeks from other provinces into southern Macedonia, as well as the linguistic and cultural Hellenization

Hellenization

Hellenization is a term used to describe the spread of ancient Greek culture, and, to a lesser extent, language. It is mainly used to describe the spread of Hellenistic civilization during the Hellenistic period following the campaigns of Alexander the Great of Macedon...

of Slav speakers. which continued even after World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

.

The Greeks expelled Exarchist churchmen and teachers and closed Bulgarian schools and churches. Bulgarian language (including the Macedonian dialects) was prohibited, and its surreptitious use, whenever detected, was ridiculed or punished.

Bulgaria's entry into World War I on the side of the Central Powers

Central Powers

The Central Powers were one of the two warring factions in World War I , composed of the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulgaria...

signified a dramatic shift in the way European public opinion viewed the Bulgarian population of Macedonia. The ultimate victory of the Allies

Allies of World War I

The Entente Powers were the countries at war with the Central Powers during World War I. The members of the Triple Entente were the United Kingdom, France, and the Russian Empire; Italy entered the war on their side in 1915...

in 1918 led to the victory of the vision of the Slavic population of Macedonia as an amorphous mass, without a developed national consciousness.

Within Greece, the ejection of the Bulgarian church, the closure of Bulgarian schools, and the banning of publication in Bulgarian language, together with the expulsion or flight to Bulgaria of a large proportion of the Macedonian Bulgarian intelligentsia, served as the prelude to campaigns of forcible cultural and linguistic assimilation.

The remaining Macedonian Bulgarians were classified as "Slavophones". After the Ilinden Uprising, the Balkan Wars and especially after the First World War more than 100,000 Bulgarians from Aegean Macedonia moved to Bulgaria.

There was agreement in 1919 between Bulgaria and Greece which provided opportunities to expatriate the Bulgarians from Greece. Until the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922) and the Population exchange between Greece and Turkey

Population exchange between Greece and Turkey

The 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey was based upon religious identity, and involved the Greek Orthodox citizens of Turkey and the Muslim citizens of Greece...

in 1923 there were also some Pomak communities in the region.

Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO)

Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Volunteer Corps

The Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Volunteer Corps was a volunteer corps of the Bulgarian Army during the Balkan Wars. It was formed on 23 September 1912 and consisted of Bulgarian volunteers from Macedonia and Thrace, regions still under Ottoman rule, and thus not subject to Bulgarian military...

and fought with the Bulgarian Army. Others with their bands assisted the Bulgarian army with its advance and still others penetrated as far as the region of Kastoria, southwestern Macedonia.

In the Second Balkan War IMRO bands fought the Greeks behind the front lines but were subsequently routed and driven out. The result of the Balkan Wars was that the Macedonian region was partitioned between Bulgaria, Greece, Serbia. IMARO maintained its existence in Bulgaria, where it played a role in politics by playing upon Bulgarian irredentism

Irredentism

Irredentism is any position advocating annexation of territories administered by another state on the grounds of common ethnicity or prior historical possession, actual or alleged. Some of these movements are also called pan-nationalist movements. It is a feature of identity politics and cultural...

and urging a renewed war.

During the First World War in Macedonia

Macedonian front (World War I)

The Macedonian Front resulted from an attempt by the Allied Powers to aid Serbia, in the autumn of 1915, against the combined attack of Germany, Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria. The expedition came too late and in insufficient force to prevent the fall of Serbia, and was complicated by the internal...

(1915–1918) the organization supported Bulgarian army and joined to Bulgarian war-time authorities. Bulgarian army, supported by the organization's forces, was successful in the first stages of this conflict, came into positions on the line of the pre-war Greek-Serbian border.

The Bulgarian advance into Greek held Eastern Macedonia, precipitated internal Greek crisis. The government ordered its troops in the area not to resist, and most of the Corps was forced to surrender. However the post-war Treaty of Neuilly

Treaty of Neuilly

The Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine, dealing with Bulgaria for its role as one of the Central Powers in World War I, was signed on 27 November 1919 at Neuilly-sur-Seine, France....

again denied Bulgaria what it felt was its share of Macedonia. From 1913 to 1926 there were large-scale changes in the population structure due to ethnic migrations.

During and after the Balkan Wars about 15,000 Slavs left the new Greek territories for Bulgaria but more significant was the Greek–Bulgarian convention 1919 in which some 72,000 Slavs-speakers left Greece for Bulgaria, mostly from Eastern Macedonia, which from then remained almost Slav free.

IMRO began sending armed bands into Greek Macedonia to assassinate officials. In 1920s in the region of Greek Macedonia 24 chetas and 10 local reconnaissance detachments were active. Many locals were repressed by the Greek authorities on suspicions of contacts with the revolutionary movement.

In this period the combined Macedonian-Adrianopolitan revolutionary movement separated into Internal Thracian Revolutionary Organization and Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization. ITRO was a revolutionary organization active in the Greek regions of Thrace

Western Thrace

Western Thrace or simply Thrace is a geographic and historical region of Greece, located between the Nestos and Evros rivers in the northeast of the country. Together with the regions of Macedonia and Epirus, it is often referred to informally as northern Greece...

and Eastern Macedonia to the river Strymon

Struma

The Struma was a ship chartered to carry Jewish refugees from Axis-allied Romania to British-controlled Palestine during World War II. On February 23, 1942, with its engine inoperable and its refugee passengers aboard, Turkish authorities towed the ship from Istanbul harbor through the Bosphorus...

. The reason for the establishment of ITRO was the transfer of the region from Bulgaria to Greece in May 1920.

At the end of 1922, the Greek government started to expel large numbers of Thracian Bulgarians

Thracian Bulgarians

Thracians or Thracian Bulgarians is a regional, ethnographic group of ethnic Bulgarians, inhabiting or originating from Thrace. Today, the larger part of this population is concentrated in Northern Thrace, but much is spread across the whole of Bulgaria and the diaspora...

into Bulgaria and the activity of ITRO grew into an open rebellion. Meanwhile, the left-wing did form the new organisation called IMRO (United) in 1925 in Vienna

Vienna

Vienna is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Austria and one of the nine states of Austria. Vienna is Austria's primary city, with a population of about 1.723 million , and is by far the largest city in Austria, as well as its cultural, economic, and political centre...

. However, it did not have real popular support and remained based abroad with, closely linked to the Comintern

Comintern

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern, also known as the Third International, was an international communist organization initiated in Moscow during March 1919...

and the Balkan Communist Federation

Balkan Communist Federation

The Balkan Federation was a project about the creation of a Balkan federation or confederation, based mainly on left political ideas.The concept of a Balkan federation emerged at the late 19th century from among left political forces in the region...

.

IMRO's and ITRO's constant fratricidal killings and assassinations abroad provoked some within Bulgarian military after the coup of 19 May 1934 to take control and break the power of the organizations, which had come to be seen as a gangster organizations inside Bulgaria and a band of assassins outside it.

Interwar period

The TarlisTarlis incident

The Tarlis incident is the name given to the killing of 17 ethnic-Bulgarian peasants by a Greek officer on July 27, 1924 at Tarlis , a mountainous village in the Drama region near the Greco-Bulgarian border.-Background:...

and Petrich incidents

Incident at Petrich

The incident at Petrich, or the War of the Stray Dog, was the short invasion of Bulgaria by Greece near the border town Petrich in 1925...

triggered heavy protests in Bulgaria and international outcry against Greece. The Common Greco-Bulgarian committee for emigration investigated the incident and presented its conclusions to League of Nations

League of Nations

The League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. It was the first permanent international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace...

in Geneva. As a result a bilateral Bulgarian-Greek agreement was signed in Geneva on September 29, 1925 known as Politis-Kalfov protocol after the demand of the League of Nations, recognizing Greek slavophones as Bulgarians and guaranteeing their protection. Next month a Slavic language primer textbook in Latin known as Abecedar

Abecedar

The Abecedar was a school book first published in Athens, Greece in 1925. The book became the subject of controversy with Bulgaria and Serbia when cited by Greece as proof it had fulfilled its international obligations towards Slavic-speaking minority, because it had been printed in the Latin...

published by the Greek ministry for education, was introduced to Greek schools of Aegean Macedonia. On February 2, 1925, the Greek parliament, under pressure from Serbia

Serbia

Serbia , officially the Republic of Serbia , is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeast Europe, covering the southern part of the Carpathian basin and the central part of the Balkans...

, rejected ratification of the 1913 Greek-Serbian Coalition Treaty. Agreement lasted 9 months until June 10, 1925 when League of Nations annulled it.

During the 1920s the Comintern developed a new policy for the Balkans, about collaboration between the communists and the Macedonian movement. The idea for a new unified organization was supported by the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

, which saw a chance for using this well developed revolutionary movement to spread revolution in the Balkans. In the so-called May Manifesto of 6 May 1924, for first time the objectives of the unified Slav Macedonian liberation movement were presented: "independence and unification of partitioned Macedonia, fighting all the neighbouring Balkan monarchies, forming a Balkan Communist Federation

Balkan Communist Federation

The Balkan Federation was a project about the creation of a Balkan federation or confederation, based mainly on left political ideas.The concept of a Balkan federation emerged at the late 19th century from among left political forces in the region...

". In 1934 the Comintern issued also a resolution about the recognition of the Slav Macedonian ethnicity. In this period Slavic Macedonian nationalism began to arise. This decision was supported by the Greek Communist Party.

The Situation for Slav-speakers became unbearable when the Metaxas regime

Metaxas

Metaxās is Greek for a silk grower or trader. It may refer to:* Metaxas Line, fortifications in northeastern Greece in 1935-1940* Metaxas, Greece, a village in the Greek region of Macedonia* Metaxa, a Greek brandy-based liqueur...

took power in 1936. Metaxas was firmly opposed to the irredentist factions of the Slavophones of northern Greece mainly in Macedonia and Thrace, some of whom underwent political persecution due to advocacy of irredentism with regard to neighboring countries. Place names and surnames were officially Hellenized and the native Slavic dialects were banned even in personal use. It was during this time that many Slavic-speakers fled their homes and immigrated to the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, Canada

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

and Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

. The name changes took place across other neighbouring states, according to the predominant language.

Ohrana and the Bulgarian annexation during WWII

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, led by Bulgarian officers.

In 1941 Greek Macedonia was occupied by German, Italian and Bulgarian troops. The Bulgarian troops occupied the whole of Eastern Macedonia and Western Thrace, where it was greeted from the greater part of a Slav-speakers as liberators. At the beginning of the occupation in Greece most of the Slavic-speakers in the area felt themselves to be Bulgarians. Only a small part espoused a pro-Hellenic feelings.

Unlike Germany and Italy, Bulgaria officially annexed the occupied territories, which had long been a target of Bulgarian irridentism

Greater Bulgaria

Greater Bulgaria is term to identify the territory associated with a historical national state and a modern Bulgarian irredentist nationalist movement which would include most of Macedonia, Thrace and Moesia...

. A massive campaign of "Bulgarisation

Bulgarisation

Bulgarisation is a term used to describe a cultural change of the spread of Bulgarian culture within various areas in the Balkans....

" was launched, which saw all Greek officials deported. This campaign was successful especially in Eastern and later in Central Macedonia, when Bulgarians entered the area in 1943, after Italian withdrawal from Greece.

All Slav-speakers there were regarded as Bulgarians and not so effective in German-occupied Western Macedonia. A ban was placed on the use of the Greek language, the names of towns and places changed to the forms traditional in Bulgarian.