Black Death in England

Encyclopedia

The pandemic

known to history as the Black Death entered England in 1348, and killed between a third and more than half of the nation's inhabitants. The Black Death

was the first and most severe manifestation of the Second Pandemic, probably caused by the Yersinia pestis

bacteria

. Originating in Central Asia

, it arrived on the British Isles from the English province of Gascony

. Its first point of entry was the port of Weymouth, where it was reported in June 1348.

Many believed that The Black Plague was brought to England with assistance from vessels that traveled into English ports. One such vessel was one which traveled from France, to a port identified as Melcombe, in Dorsetshire. Ships that traveled from French towns such as Calais, which was acquired in 1347 by Edward III, brought the plague through hosts namely infected rats and fleas. “Edward III’s triumph over the French at Crecy was followed in 1347 by the capture of Calais, and when he landed at Sandwich in October 1347 he was greeted with the greatest enthusiasm.” These ships were at first seen as saviors, due to the fact that they allowed England to flourish through the use of new trade methods. It reached London in the autumn of that year, and by the next summer it had covered the entire country. By December 1349 the outbreak was mostly over. Though accurate estimates of mortality are difficult to make, the recent trend has been to adjust the estimates upwards. This is the result of recent scholarship's focus on the peasant society which made up around 90% of the population rather than the greater landowners and the clergy. While it was previously assumed that one third or less of the population died, a number of around half is generally accepted, though some have suggested an even higher mortality.

The Black Death struck a prosperous and internationally ascendant nation. Though the loss of life was great, the English government handled the crisis well. The most immediate consequence was a halt to the campaigns of the Hundred Years' War

. England did not experience the extreme forms of religious fervour (flagellant

s, and persecution of Jews to name a couple) that were seen in other areas of Europe, such as France. In the long term the plague would have great social consequences though. The decrease in population caused a shortage of labour, with subsequent rise in wages. The landowning classes tried to curb this development through legislation and punitive measure, leading to deep resentment among the lower classes. The Peasants' Revolt

of 1381 was largely a result of this resentment, and even though the rebellion was suppressed, in the long term serfdom

was ended in England. The Black Death also affected artistic and cultural efforts, and may have helped advance the use of the vernacular

.

In 1361–62 the plague returned to England, this time causing the death of around 20% of the population. After this the plague continued to return intermittently throughout the 14th and 15th centuries, in local or national outbreaks. From this point on its impact became less severe, much due to conscious government efforts. One of the last outbreaks of the plague in England was the Great Plague of London

in 1665-66.

at the eve of the Black Death

, and estimates range from 3 to 7 million. The number is probably in the higher end, and an estimate of around 6 million inhabitants seems likely. Earlier demographic crises in particular the Great Famine of 1315–1317

had resulted in great numbers of deaths, but there is no evidence of any significant decrease in the population prior to 1348. England was still a predominantly rural and agrarian society; close to 90% of the population lived on the countryside. Of the major cities, London

was in a class of its own, with perhaps as many as 70,000 inhabitants. Further down the scale were Norwich

, with around 12,000 people, and York

with around 10,000. The main export, and the source of the nation's wealth, was wool. Until the middle of the century the export had consisted primarily of raw wool to cloth makers in Flanders

. Gradually though, the technology for cloth making used on the Continent was appropriated by English manufacturers, and around mid-century started an export of cloths that would boom over the following decades.

Politically, the kingdom was evolving into a major European power, through the youthful and energetic kingship of Edward III

. In 1346, the English had won a decisive battle over the Scots

at the Battle of Neville's Cross

. Though in the long run it was not to be, it seemed at the time that Edward III would realise his grandfather Edward I

's ambition of bringing the Scots under the suzerainty

of the English crown. Also on the continent the English were experiencing military success. Less than two months before Neville's Cross a numerically inferior English army, led by the king himself, won a spectacular victory over the French royal forces at the Battle of Crécy

. The victory was immediately followed by Edward laying siege to the port city of Calais

. When the city fell the next year, this provided the English with a strategically important enclave that would remain in their possession for over two centuries.

The term "Black Death" which refers to the first and most serious outbreak of the Second Pandemic was not used by contemporaries, who preferred such names as the "Great Pestilence" or the "Great Mortality". It was not until the seventeenth century that the term under which we know the outbreak today became common, probably derived from Scandinavian languages. It is generally agreed today that the disease in question was plague, caused by Yersinia pestis

The term "Black Death" which refers to the first and most serious outbreak of the Second Pandemic was not used by contemporaries, who preferred such names as the "Great Pestilence" or the "Great Mortality". It was not until the seventeenth century that the term under which we know the outbreak today became common, probably derived from Scandinavian languages. It is generally agreed today that the disease in question was plague, caused by Yersinia pestis

bacteria

. These bacteria are carried by flea

s, which can be transferred to humans through contact with rat

s. Flea bites carry the disease into the lymphatic system

, through which it makes its way to the lymph node

s. Here the bacteria multiply and form swellings called bubo

es, from which the term bubonic plague

is derived. After three or four days the bacteria enter the bloodstream, and infect organs such as the spleen

and the lung

s. The patient will then normally die after a few days. A different strand of the disease is pneumonic plague

, where the bacteria become airborne and enters directly into the patient's lungs. This strand is far more virulent, as it spreads directly from person to person. These types of infection probably both played a significant part in the Black Death, while a third strand was more rare. This is the septicaemic

plague, where the flea bite carries the bacteria directly into the blood stream, and death occurs very rapidly.

Though most authorities agree that the Black Death was caused by Yersinia pestis, there have been several alternatives presented. Graham Twigg, in The Black Death: A Biological Reappraisal (1984), suggested anthrax

as the cause of the epidemic. This theory was at least partially supported by Norman Cantor

as late as 2002. In his In the Wake of the Plague: The Black Death and the World it Made, he presents evidence that anthrax and bubonic plague coexisted in fourteenth-century Europe. A 2004 study by Susan Scott and Christopher Duncan theorises that a filovirus

, similar to the Ebola

virus, may have been behind the disease.

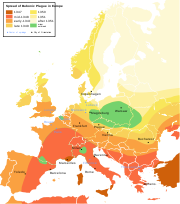

The Black Death most likely originated in Central Asia

, where the disease is endemic in the rodent

population. It is unknown exactly what caused the outbreak, but probably a series of natural disasters brought humans into contact with the infected rodents. The epidemic reached Constantinople in the late spring of 1347, through Genoese

merchants trading in the Black Sea

. From here it reached Sicily

in October that same year, and by early 1348 it had spread all over the Italian mainland. It spread rapidly through France, and had reached as far north as Paris in June 1348. Moving simultaneously westward, it arrived in the English province of Gascony

around the same time.

at King's Lynn

, the plague arrived by ship from Gascony

to Melcombe

in Dorset today normally referred to as Weymouth shortly before "the Feast of St. John The Baptist" or 24 June 1348. Other sources mention different points of arrival, including Bristol and Southampton. Though the plague might have arrived independently at Bristol at a later point, the Grey Friars' Chronicle is considered the most authoritative account. If it is assumed that the chronicle reports the first outbreak of the plague, rather than its actual arrival, then the arrival most likely happened around 8 May.

From Weymouth the disease spread rapidly across the south-west. The first major city to be struck was Bristol

. London was reached in the autumn of 1348, before most of the surrounding countryside. This had certainly happened by November, though according to some accounts as early as 29 September. Arrival in London happened by three principal roads: overland from Weymouth through Salisbury

and Winchester

overland from Gloucester

, and along the coast by ship. The full effect of the plague was felt in the capital early the next year. Conditions in London were ideal for the plague: the streets were narrow and flowing with sewage, and houses were overcrowded and poorly ventilated. By March 1349 the disease was spreading in a haphazard way across all of southern England.

During the first half of 1349 the Black Death spread northwards. A second front opened up when the plague arrived by ship at the Humber

, wherefrom it spread both south and north. In May it reached York

, and during the summer months of June, July and August, it ravaged the north. Certain northern counties, like Durham

and Cumberland

, had been the victim of violent incursions from the Scots, and were therefore left particularly vulnerable to the devastations of the plague. Pestilence is less virulent during the winter months, and spreads less rapidly. The Black Death in England had survived the winter of 1348-49, but during the following winter it gave in, and by December 1349 conditions were returning to relative normalcy. It had taken the disease approximately 500 days to traverse the entire country.

, bloodletting

, forced vomiting, and glister. Within the initial phase of the disease, bloodletting

was performed on the same side of where the physical manifestations of the buboes or risings appeared. For instance, if a rising appeared on the right side of the groin the physician would bleed a vein in the ankle on the same side. In the case of sweating

, it was achieved with such medicines as Mithridate, Venice-Treacle, Matthiolus, Bezoar-Water, Serpentary Roots and Electuarium de Ovo. Sweating

was used when measures were desperate; if a patient had tokens, a severe version of risings, the physician would wrap the naked patient in a blanket drenched in cold water. This measure was only performed while the patient still had natural heat in his system. The desired effect was to make the patient sweat violently and thus purge all corruption from the blood which was caused by the disease.

Another practice was the use of pigeons when treating swellings. Swellings which were white in appearance and deep were unlikely to break and must be anointed with Oil of Lillies or Camomil. Once the swelling rises to a head and is red in appearance and not deep in the flesh, it can be broken with the use of a feather from a young pigeon's tail. The feather's fundament was held to the swelling and would draw out the venom. However, if the swelling dropped and became black in appearance since it had taken in coldness, the physician had to be cautious when drawing the cold from the swelling. If it was too late to prevent, the physician would take the young pigeon, cut her open from breast to back, break her open and apply the pigeon (while still alive) over the cold swelling. The cupping-glass was an alternative method which was heated and then placed over the swellings. Once the sore was broken, the physician would apply Mellilot Plaister with Linimentum Arcei and heal the sore with diligence.

The pioneering work in the field was made by Josiah William Russell in his 1948 British Medieval Population. Russell looked at inquisitions post mortem (IPMs) taken by the crown to assess the wealth of the greatest landowners after their death to assess the mortality caused by the Black Death, and from this arrived at an estimate of 23.6% of the entire population. He also looked at episcopal registers for the death toll among the clergy, where the result was between 30–40%. Russell believed the clergy was at particular risk of contagion, and eventually concluded with a low mortality level of only 20%.

The pioneering work in the field was made by Josiah William Russell in his 1948 British Medieval Population. Russell looked at inquisitions post mortem (IPMs) taken by the crown to assess the wealth of the greatest landowners after their death to assess the mortality caused by the Black Death, and from this arrived at an estimate of 23.6% of the entire population. He also looked at episcopal registers for the death toll among the clergy, where the result was between 30–40%. Russell believed the clergy was at particular risk of contagion, and eventually concluded with a low mortality level of only 20%.

Several of Russell's assumptions have been challenged, and the tendency since has been to adjust the assessment upwards. Philip Ziegler

, in 1969, estimated the death rate to be at around one third of the population. Jeremy Goldberg

, in 1996, believed a number closer to 45% would be more realistic. A 2004 study by Ole Jørgen Benedictow

suggests the exceptionally high mortality level of 62.5%. Assuming a population of 6 million, this estimate would correspond to 3,750,000 deaths. Such a high percentage would place England above the average that Benedictow estimates for Western Europe as a whole, of 60%. A death rate at such a high level has not been universally accepted in the historical community.

rolls have returned much higher rates. This could be a consequence of the elite's ability to avoid infection by escaping plague-infected areas. It could also result from lower post-infection mortality among those more affluent, due to better access to care and nursing. If so, this would also mean that the mortality rates for the clergy who were normally better off than the general population were no higher than the average.

The manorial records offer a good opportunity to study the geographical distribution of the plague. Its impact seems to have been about the same all over England, though a place like East Anglia

, which had frequent contact with the Continent, was severely affected. On a local level, however, there were great variations. A study of the Bishop of Worcester

's estates reveal that, while his manors of Hartlebury and Hambury had a mortality of only 19%, the manor of Aston lost as much as 80% of its population. The manor rolls are less useful for studying the demographic distribution of the mortality, since the rolls only record the heads of households, normally an adult male. Here the IPMs show us that the most vulnerable to the disease were infants and the elderly.

There seem to have been very few victims of the Black Death at higher levels of society. The only member of the royal family who can be said with any certainty to have died from the Black Death was in France at the time of her infection. Edward III's daughter Joan

was residing in Bordeaux

on her way to marry Pedro of Castile

in the summer of 1348. When the plague broke out in her household she was moved to a small village nearby, but she could not avoid infection, and died there on 2 September. It is possible that the popular religious author Richard Rolle

, who died on 30 September 1349, was another victim of the Black Death. The English philosopher William of Ockham

has been mentioned as a plague victim. This, however, is an impossibility. Ockham was living in Munich

at the time of his death, on 10 April 1347, two years before the Black Death reached that city.

, fixing wages at pre-plague levels. The ordinance was reinforced by parliament's passing of the Statute of Labourers in 1351. The labour laws were enforced with ruthless determination over the following decades.

These legislative measures proved largely inefficient at regulating the market, but the government's repressive measures to enforce them caused public resentment. These conditions were contributing factors to the Peasants' Revolt

These legislative measures proved largely inefficient at regulating the market, but the government's repressive measures to enforce them caused public resentment. These conditions were contributing factors to the Peasants' Revolt

in 1381. The revolt started in Kent and Essex in late May, and once the rebels reached London they burnt down John of Gaunt's Savoy Palace

, and killed both the Chancellor

and the Treasurer

. They then demanded the complete abolition of serfdom

, and were not pacified until the young King Richard II

personally intervened. The rebellion was eventually suppressed, but the social changes it promoted were already irreversible. By around 1400 serfdom was virtually extinct in England, replaced by the form of tenure called copyhold

.

It is conspicuous how well the English government handled the crisis of the mid-fourteenth century, without descending into chaos and total collapse in the manner of the Valois government of France. To a large extent this was the accomplishment of administrators such as Treasurer

William de Shareshull

and Chief Justice

William Edington, whose highly competent leadership guided the governance of the nation through the crisis. The plague's greatest effect on the government was probably in the field of war, where no major campaigns were launched in France until 1355.

Another notable consequence of the black death was the raising of the real wage of England (due to the shortage of labour as a result of the reduction in population), a trait shared across Western Europe, which in general led to a real wage in 1450 that was unmatched in most countries until the 19th or 20th century.

colleges were founded during or shortly after the Black Death. England did not experience the same trend of roving bands of flagellant

s, common on the continent. Neither were there any pogrom

s against the Jews, since the Jews had been expelled by Edward I

in 1290. In the long run, however, the increase in public participation may have served to challenge the absolute authority of the church hierarchy, and thus possibly helped pave the way for the Protestant Reformation

.

The high rate of mortality among the clergy naturally led to a shortage of priests in many parts of the country. The clergy were seen to have an elevated status among ordinary people and this was partly due to their closeness with god, being his envoys on earth. However, as the church itself had given the cause of the black death to be the impropriety of the behaviour of men, the higher death rate among the clergy lead the people to lose faith in the Church as an institution - it had proved as ineffectual against the horror of Y. Pestis as every other medieval institution. But they didn't lose their Christian faith, if anything it was renewed; they began to long for a more personal relationship with god - around the time after the black death many Chantries (private chapels) began to spread in use from not just the nobility, but to among the well to do. This change in the power of the papacy in England is demonstrated by the statutes of Praemunire

.

The Black Death also had a great impact on arts and culture. It was inevitable that a catastrophe of such proportions would have an impact on some of the greater building projects, as the amount of available labour fell sharply. The building of the cathedrals of Ely

and Exeter

was temporarily halted in the years immediately following the first outbreak of the plague. The shortage of labour also helped advance the transition from the Decorated style of building to the less elaborate Perpendicular style. The Black Death may also have promoted the use of vernacular English

, as the number of teachers proficient in French dwindled. This, in turn, would have contributed to the late-fourteenth century flowering of English literature, represented by writers such as Geoffrey Chaucer

and John Gower

.

The Black Death was the first occurrence of the Second Pandemic, which would continue to strike England and the rest of Europe more or less regularly until the seventeenth century. The first serious recurrence in England came in the years 1361-62. We know less about the death rates caused by these later outbreaks, but this so-called pestis secunda may have had a mortality of around 20%. This epidemic was also particularly devastating for the population's ability to recover, since it disproportionately affected infants and young men. This was also the case with the next occurrence, in 1369, where the death rate was around 10-15%.

The Black Death was the first occurrence of the Second Pandemic, which would continue to strike England and the rest of Europe more or less regularly until the seventeenth century. The first serious recurrence in England came in the years 1361-62. We know less about the death rates caused by these later outbreaks, but this so-called pestis secunda may have had a mortality of around 20%. This epidemic was also particularly devastating for the population's ability to recover, since it disproportionately affected infants and young men. This was also the case with the next occurrence, in 1369, where the death rate was around 10-15%.

Over the following decades the plague would return on a national or a regional level at intervals of five to twelve years, with gradually dwindling death tolls. Then, in the decades from 1430 to 1480, the disease returned in force. An outbreak in 1471 took as much as 10-15% of the population, while the death rate of the plague of 1479-80 could have been as high as 20%. From this point on outbreaks became fewer and more manageable. This was to a large extent the result of conscious efforts by central and local governments from the late fifteenth century onwards to curtail the disease. By the seventeenth century the Second Pandemic was over. One of its last occurrences in England was the famous Great Plague of London

in 1665-66.

Pandemic

A pandemic is an epidemic of infectious disease that is spreading through human populations across a large region; for instance multiple continents, or even worldwide. A widespread endemic disease that is stable in terms of how many people are getting sick from it is not a pandemic...

known to history as the Black Death entered England in 1348, and killed between a third and more than half of the nation's inhabitants. The Black Death

Black Death

The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, peaking in Europe between 1348 and 1350. Of several competing theories, the dominant explanation for the Black Death is the plague theory, which attributes the outbreak to the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Thought to have...

was the first and most severe manifestation of the Second Pandemic, probably caused by the Yersinia pestis

Yersinia pestis

Yersinia pestis is a Gram-negative rod-shaped bacterium. It is a facultative anaerobe that can infect humans and other animals....

bacteria

Bacteria

Bacteria are a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria have a wide range of shapes, ranging from spheres to rods and spirals...

. Originating in Central Asia

Central Asia

Central Asia is a core region of the Asian continent from the Caspian Sea in the west, China in the east, Afghanistan in the south, and Russia in the north...

, it arrived on the British Isles from the English province of Gascony

Duke of Gascony

The Duchy of Vasconia , later known as Gascony, was a Merovingian creation: a frontier duchy on the Garonne, in the border with the rebel Basque tribes...

. Its first point of entry was the port of Weymouth, where it was reported in June 1348.

Many believed that The Black Plague was brought to England with assistance from vessels that traveled into English ports. One such vessel was one which traveled from France, to a port identified as Melcombe, in Dorsetshire. Ships that traveled from French towns such as Calais, which was acquired in 1347 by Edward III, brought the plague through hosts namely infected rats and fleas. “Edward III’s triumph over the French at Crecy was followed in 1347 by the capture of Calais, and when he landed at Sandwich in October 1347 he was greeted with the greatest enthusiasm.” These ships were at first seen as saviors, due to the fact that they allowed England to flourish through the use of new trade methods. It reached London in the autumn of that year, and by the next summer it had covered the entire country. By December 1349 the outbreak was mostly over. Though accurate estimates of mortality are difficult to make, the recent trend has been to adjust the estimates upwards. This is the result of recent scholarship's focus on the peasant society which made up around 90% of the population rather than the greater landowners and the clergy. While it was previously assumed that one third or less of the population died, a number of around half is generally accepted, though some have suggested an even higher mortality.

The Black Death struck a prosperous and internationally ascendant nation. Though the loss of life was great, the English government handled the crisis well. The most immediate consequence was a halt to the campaigns of the Hundred Years' War

Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War was a series of separate wars waged from 1337 to 1453 by the House of Valois and the House of Plantagenet, also known as the House of Anjou, for the French throne, which had become vacant upon the extinction of the senior Capetian line of French kings...

. England did not experience the extreme forms of religious fervour (flagellant

Flagellant

Flagellants are practitioners of an extreme form of mortification of their own flesh by whipping it with various instruments.- History :Flagellantism was a 13th and 14th centuries movement, consisting of radicals in the Catholic Church. It began as a militant pilgrimage and was later condemned by...

s, and persecution of Jews to name a couple) that were seen in other areas of Europe, such as France. In the long term the plague would have great social consequences though. The decrease in population caused a shortage of labour, with subsequent rise in wages. The landowning classes tried to curb this development through legislation and punitive measure, leading to deep resentment among the lower classes. The Peasants' Revolt

Peasants' Revolt

The Peasants' Revolt, Wat Tyler's Rebellion, or the Great Rising of 1381 was one of a number of popular revolts in late medieval Europe and is a major event in the history of England. Tyler's Rebellion was not only the most extreme and widespread insurrection in English history but also the...

of 1381 was largely a result of this resentment, and even though the rebellion was suppressed, in the long term serfdom

Serfdom

Serfdom is the status of peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to Manorialism. It was a condition of bondage or modified slavery which developed primarily during the High Middle Ages in Europe and lasted to the mid-19th century...

was ended in England. The Black Death also affected artistic and cultural efforts, and may have helped advance the use of the vernacular

Vernacular

A vernacular is the native language or native dialect of a specific population, as opposed to a language of wider communication that is not native to the population, such as a national language or lingua franca.- Etymology :The term is not a recent one...

.

In 1361–62 the plague returned to England, this time causing the death of around 20% of the population. After this the plague continued to return intermittently throughout the 14th and 15th centuries, in local or national outbreaks. From this point on its impact became less severe, much due to conscious government efforts. One of the last outbreaks of the plague in England was the Great Plague of London

Great Plague of London

The Great Plague was a massive outbreak of disease in the Kingdom of England that killed an estimated 100,000 people, 20% of London's population. The disease is identified as bubonic plague, an infection by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, transmitted through a flea vector...

in 1665-66.

Background

England in 1348

It is impossible to establish with any certainty the exact number of inhabitants in EnglandEngland

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

at the eve of the Black Death

Black Death

The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, peaking in Europe between 1348 and 1350. Of several competing theories, the dominant explanation for the Black Death is the plague theory, which attributes the outbreak to the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Thought to have...

, and estimates range from 3 to 7 million. The number is probably in the higher end, and an estimate of around 6 million inhabitants seems likely. Earlier demographic crises in particular the Great Famine of 1315–1317

Great Famine of 1315–1317

The Great Famine of 1315–1317 was the first of a series of large scale crises that struck Northern Europe early in the fourteenth century...

had resulted in great numbers of deaths, but there is no evidence of any significant decrease in the population prior to 1348. England was still a predominantly rural and agrarian society; close to 90% of the population lived on the countryside. Of the major cities, London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

was in a class of its own, with perhaps as many as 70,000 inhabitants. Further down the scale were Norwich

Norwich

Norwich is a city in England. It is the regional administrative centre and county town of Norfolk. During the 11th century, Norwich was the largest city in England after London, and one of the most important places in the kingdom...

, with around 12,000 people, and York

York

York is a walled city, situated at the confluence of the Rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. The city has a rich heritage and has provided the backdrop to major political events throughout much of its two millennia of existence...

with around 10,000. The main export, and the source of the nation's wealth, was wool. Until the middle of the century the export had consisted primarily of raw wool to cloth makers in Flanders

Flanders

Flanders is the community of the Flemings but also one of the institutions in Belgium, and a geographical region located in parts of present-day Belgium, France and the Netherlands. "Flanders" can also refer to the northern part of Belgium that contains Brussels, Bruges, Ghent and Antwerp...

. Gradually though, the technology for cloth making used on the Continent was appropriated by English manufacturers, and around mid-century started an export of cloths that would boom over the following decades.

Politically, the kingdom was evolving into a major European power, through the youthful and energetic kingship of Edward III

Edward III of England

Edward III was King of England from 1327 until his death and is noted for his military success. Restoring royal authority after the disastrous reign of his father, Edward II, Edward III went on to transform the Kingdom of England into one of the most formidable military powers in Europe...

. In 1346, the English had won a decisive battle over the Scots

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

at the Battle of Neville's Cross

Battle of Neville's Cross

The Battle of Neville's Cross took place to the west of Durham, England on 17 October 1346.-Background:In 1346, England was embroiled in the Hundred Years' War with France. In order to divert his enemy Philip VI of France appealed to David II of Scotland to attack the English from the north in...

. Though in the long run it was not to be, it seemed at the time that Edward III would realise his grandfather Edward I

Edward I of England

Edward I , also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England from 1272 to 1307. The first son of Henry III, Edward was involved early in the political intrigues of his father's reign, which included an outright rebellion by the English barons...

's ambition of bringing the Scots under the suzerainty

Suzerainty

Suzerainty occurs where a region or people is a tributary to a more powerful entity which controls its foreign affairs while allowing the tributary vassal state some limited domestic autonomy. The dominant entity in the suzerainty relationship, or the more powerful entity itself, is called a...

of the English crown. Also on the continent the English were experiencing military success. Less than two months before Neville's Cross a numerically inferior English army, led by the king himself, won a spectacular victory over the French royal forces at the Battle of Crécy

Battle of Crécy

The Battle of Crécy took place on 26 August 1346 near Crécy in northern France, and was one of the most important battles of the Hundred Years' War...

. The victory was immediately followed by Edward laying siege to the port city of Calais

Calais

Calais is a town in Northern France in the department of Pas-de-Calais, of which it is a sub-prefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's capital is its third-largest city of Arras....

. When the city fell the next year, this provided the English with a strategically important enclave that would remain in their possession for over two centuries.

The Black Death

Yersinia pestis

Yersinia pestis is a Gram-negative rod-shaped bacterium. It is a facultative anaerobe that can infect humans and other animals....

bacteria

Bacteria

Bacteria are a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria have a wide range of shapes, ranging from spheres to rods and spirals...

. These bacteria are carried by flea

Flea

Flea is the common name for insects of the order Siphonaptera which are wingless insects with mouthparts adapted for piercing skin and sucking blood...

s, which can be transferred to humans through contact with rat

Rat

Rats are various medium-sized, long-tailed rodents of the superfamily Muroidea. "True rats" are members of the genus Rattus, the most important of which to humans are the black rat, Rattus rattus, and the brown rat, Rattus norvegicus...

s. Flea bites carry the disease into the lymphatic system

Lymphatic system

The lymphoid system is the part of the immune system comprising a network of conduits called lymphatic vessels that carry a clear fluid called lymph unidirectionally toward the heart. Lymphoid tissue is found in many organs, particularly the lymph nodes, and in the lymphoid follicles associated...

, through which it makes its way to the lymph node

Lymph node

A lymph node is a small ball or an oval-shaped organ of the immune system, distributed widely throughout the body including the armpit and stomach/gut and linked by lymphatic vessels. Lymph nodes are garrisons of B, T, and other immune cells. Lymph nodes are found all through the body, and act as...

s. Here the bacteria multiply and form swellings called bubo

Bubo

Bubo may refer to:* A bubo, a rounded swelling on the skin of a person afflicted by the bubonic plague.* Bubo, the horned owl and eagle-owl genus.* Bubo, a mechanical owl in the 1981 film Clash of the Titans...

es, from which the term bubonic plague

Bubonic plague

Plague is a deadly infectious disease that is caused by the enterobacteria Yersinia pestis, named after the French-Swiss bacteriologist Alexandre Yersin. Primarily carried by rodents and spread to humans via fleas, the disease is notorious throughout history, due to the unrivaled scale of death...

is derived. After three or four days the bacteria enter the bloodstream, and infect organs such as the spleen

Spleen

The spleen is an organ found in virtually all vertebrate animals with important roles in regard to red blood cells and the immune system. In humans, it is located in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen. It removes old red blood cells and holds a reserve of blood in case of hemorrhagic shock...

and the lung

Lung

The lung is the essential respiration organ in many air-breathing animals, including most tetrapods, a few fish and a few snails. In mammals and the more complex life forms, the two lungs are located near the backbone on either side of the heart...

s. The patient will then normally die after a few days. A different strand of the disease is pneumonic plague

Pneumonic plague

Pneumonic plague, a severe type of lung infection, is one of three main forms of plague, all of which are caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis. It is more virulent and rare than bubonic plague...

, where the bacteria become airborne and enters directly into the patient's lungs. This strand is far more virulent, as it spreads directly from person to person. These types of infection probably both played a significant part in the Black Death, while a third strand was more rare. This is the septicaemic

Sepsis

Sepsis is a potentially deadly medical condition that is characterized by a whole-body inflammatory state and the presence of a known or suspected infection. The body may develop this inflammatory response by the immune system to microbes in the blood, urine, lungs, skin, or other tissues...

plague, where the flea bite carries the bacteria directly into the blood stream, and death occurs very rapidly.

Though most authorities agree that the Black Death was caused by Yersinia pestis, there have been several alternatives presented. Graham Twigg, in The Black Death: A Biological Reappraisal (1984), suggested anthrax

Anthrax

Anthrax is an acute disease caused by the bacterium Bacillus anthracis. Most forms of the disease are lethal, and it affects both humans and other animals...

as the cause of the epidemic. This theory was at least partially supported by Norman Cantor

Norman Cantor

Norman Frank Cantor was a historian who specialized in the medieval period. Known for his accessible writing and engaging narrative style, Cantor's books were among the most widely-read treatments of medieval history in English...

as late as 2002. In his In the Wake of the Plague: The Black Death and the World it Made, he presents evidence that anthrax and bubonic plague coexisted in fourteenth-century Europe. A 2004 study by Susan Scott and Christopher Duncan theorises that a filovirus

Filoviridae

The family Filoviridae is the taxonomic home of several related viruses that form filamentous virions. Two members of the family that are commonly known are Ebola virus and Marburg virus. Both viruses, and some of their lesser known relatives, cause severe disease in humans and nonhuman primates in...

, similar to the Ebola

Ebola

Ebola virus disease is the name for the human disease which may be caused by any of the four known ebolaviruses. These four viruses are: Bundibugyo virus , Ebola virus , Sudan virus , and Taï Forest virus...

virus, may have been behind the disease.

The Black Death most likely originated in Central Asia

Central Asia

Central Asia is a core region of the Asian continent from the Caspian Sea in the west, China in the east, Afghanistan in the south, and Russia in the north...

, where the disease is endemic in the rodent

Rodent

Rodentia is an order of mammals also known as rodents, characterised by two continuously growing incisors in the upper and lower jaws which must be kept short by gnawing....

population. It is unknown exactly what caused the outbreak, but probably a series of natural disasters brought humans into contact with the infected rodents. The epidemic reached Constantinople in the late spring of 1347, through Genoese

Genoa

Genoa |Ligurian]] Zena ; Latin and, archaically, English Genua) is a city and an important seaport in northern Italy, the capital of the Province of Genoa and of the region of Liguria....

merchants trading in the Black Sea

Black Sea

The Black Sea is bounded by Europe, Anatolia and the Caucasus and is ultimately connected to the Atlantic Ocean via the Mediterranean and the Aegean seas and various straits. The Bosphorus strait connects it to the Sea of Marmara, and the strait of the Dardanelles connects that sea to the Aegean...

. From here it reached Sicily

Sicily

Sicily is a region of Italy, and is the largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Along with the surrounding minor islands, it constitutes an autonomous region of Italy, the Regione Autonoma Siciliana Sicily has a rich and unique culture, especially with regard to the arts, music, literature,...

in October that same year, and by early 1348 it had spread all over the Italian mainland. It spread rapidly through France, and had reached as far north as Paris in June 1348. Moving simultaneously westward, it arrived in the English province of Gascony

Gascony

Gascony is an area of southwest France that was part of the "Province of Guyenne and Gascony" prior to the French Revolution. The region is vaguely defined and the distinction between Guyenne and Gascony is unclear; sometimes they are considered to overlap, and sometimes Gascony is considered a...

around the same time.

Progress of the plague

According to the chronicle of the grey friarsFranciscan

Most Franciscans are members of Roman Catholic religious orders founded by Saint Francis of Assisi. Besides Roman Catholic communities, there are also Old Catholic, Anglican, Lutheran, ecumenical and Non-denominational Franciscan communities....

at King's Lynn

King's Lynn

King's Lynn is a sea port and market town in the ceremonial county of Norfolk in the East of England. It is situated north of London and west of Norwich. The population of the town is 42,800....

, the plague arrived by ship from Gascony

Gascony

Gascony is an area of southwest France that was part of the "Province of Guyenne and Gascony" prior to the French Revolution. The region is vaguely defined and the distinction between Guyenne and Gascony is unclear; sometimes they are considered to overlap, and sometimes Gascony is considered a...

to Melcombe

Melcombe Regis

Melcombe Regis is an area of Weymouth in Dorset, England.Situated on the north shore of Weymouth Harbour and originally part of the waste of Radipole, it seems only to have developed as a significant settlement and seaport in the 13th century...

in Dorset today normally referred to as Weymouth shortly before "the Feast of St. John The Baptist" or 24 June 1348. Other sources mention different points of arrival, including Bristol and Southampton. Though the plague might have arrived independently at Bristol at a later point, the Grey Friars' Chronicle is considered the most authoritative account. If it is assumed that the chronicle reports the first outbreak of the plague, rather than its actual arrival, then the arrival most likely happened around 8 May.

From Weymouth the disease spread rapidly across the south-west. The first major city to be struck was Bristol

Bristol

Bristol is a city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, with an estimated population of 433,100 for the unitary authority in 2009, and a surrounding Larger Urban Zone with an estimated 1,070,000 residents in 2007...

. London was reached in the autumn of 1348, before most of the surrounding countryside. This had certainly happened by November, though according to some accounts as early as 29 September. Arrival in London happened by three principal roads: overland from Weymouth through Salisbury

Salisbury

Salisbury is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England and the only city in the county. It is the second largest settlement in the county...

and Winchester

Winchester

Winchester is a historic cathedral city and former capital city of England. It is the county town of Hampshire, in South East England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government district, and is located at the western end of the South Downs, along the course of...

overland from Gloucester

Gloucester

Gloucester is a city, district and county town of Gloucestershire in the South West region of England. Gloucester lies close to the Welsh border, and on the River Severn, approximately north-east of Bristol, and south-southwest of Birmingham....

, and along the coast by ship. The full effect of the plague was felt in the capital early the next year. Conditions in London were ideal for the plague: the streets were narrow and flowing with sewage, and houses were overcrowded and poorly ventilated. By March 1349 the disease was spreading in a haphazard way across all of southern England.

During the first half of 1349 the Black Death spread northwards. A second front opened up when the plague arrived by ship at the Humber

Humber

The Humber is a large tidal estuary on the east coast of Northern England. It is formed at Trent Falls, Faxfleet, by the confluence of the tidal River Ouse and the tidal River Trent. From here to the North Sea, it forms part of the boundary between the East Riding of Yorkshire on the north bank...

, wherefrom it spread both south and north. In May it reached York

York

York is a walled city, situated at the confluence of the Rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. The city has a rich heritage and has provided the backdrop to major political events throughout much of its two millennia of existence...

, and during the summer months of June, July and August, it ravaged the north. Certain northern counties, like Durham

County Durham

County Durham is a ceremonial county and unitary district in north east England. The county town is Durham. The largest settlement in the ceremonial county is the town of Darlington...

and Cumberland

Cumberland

Cumberland is a historic county of North West England, on the border with Scotland, from the 12th century until 1974. It formed an administrative county from 1889 to 1974 and now forms part of Cumbria....

, had been the victim of violent incursions from the Scots, and were therefore left particularly vulnerable to the devastations of the plague. Pestilence is less virulent during the winter months, and spreads less rapidly. The Black Death in England had survived the winter of 1348-49, but during the following winter it gave in, and by December 1349 conditions were returning to relative normalcy. It had taken the disease approximately 500 days to traverse the entire country.

Medical Practices

In order to treat patients infected with the plague, various methods were used including sweatingSweating

Perspiration is the production of a fluid consisting primarily of water as well as various dissolved solids , that is excreted by the sweat glands in the skin of mammals...

, bloodletting

Bloodletting

Bloodletting is the withdrawal of often little quantities of blood from a patient to cure or prevent illness and disease. Bloodletting was based on an ancient system of medicine in which blood and other bodily fluid were considered to be "humors" the proper balance of which maintained health...

, forced vomiting, and glister. Within the initial phase of the disease, bloodletting

Bloodletting

Bloodletting is the withdrawal of often little quantities of blood from a patient to cure or prevent illness and disease. Bloodletting was based on an ancient system of medicine in which blood and other bodily fluid were considered to be "humors" the proper balance of which maintained health...

was performed on the same side of where the physical manifestations of the buboes or risings appeared. For instance, if a rising appeared on the right side of the groin the physician would bleed a vein in the ankle on the same side. In the case of sweating

Sweating

Perspiration is the production of a fluid consisting primarily of water as well as various dissolved solids , that is excreted by the sweat glands in the skin of mammals...

, it was achieved with such medicines as Mithridate, Venice-Treacle, Matthiolus, Bezoar-Water, Serpentary Roots and Electuarium de Ovo. Sweating

Sweating

Perspiration is the production of a fluid consisting primarily of water as well as various dissolved solids , that is excreted by the sweat glands in the skin of mammals...

was used when measures were desperate; if a patient had tokens, a severe version of risings, the physician would wrap the naked patient in a blanket drenched in cold water. This measure was only performed while the patient still had natural heat in his system. The desired effect was to make the patient sweat violently and thus purge all corruption from the blood which was caused by the disease.

Another practice was the use of pigeons when treating swellings. Swellings which were white in appearance and deep were unlikely to break and must be anointed with Oil of Lillies or Camomil. Once the swelling rises to a head and is red in appearance and not deep in the flesh, it can be broken with the use of a feather from a young pigeon's tail. The feather's fundament was held to the swelling and would draw out the venom. However, if the swelling dropped and became black in appearance since it had taken in coldness, the physician had to be cautious when drawing the cold from the swelling. If it was too late to prevent, the physician would take the young pigeon, cut her open from breast to back, break her open and apply the pigeon (while still alive) over the cold swelling. The cupping-glass was an alternative method which was heated and then placed over the swellings. Once the sore was broken, the physician would apply Mellilot Plaister with Linimentum Arcei and heal the sore with diligence.

Death toll

Although historical records for England were more extensive than those of any other European country, it is still extremely difficult to establish the death toll with any degree of certainty. Difficulties involve uncertainty about the size of the total population, as described above, but also issues regarding the proportion of the population that died from the plague. Contemporary accounts are often grossly inflated, stating numbers as high as 90%. Modern historians give estimates of death rates ranging from around 25% to over 60% of the total population.

Several of Russell's assumptions have been challenged, and the tendency since has been to adjust the assessment upwards. Philip Ziegler

Philip Ziegler

-Background:Born in Ringwood, Ziegler was educated at St Cyprian's School, Eastbourne, and went with the school when it merged with Summer Fields School, Oxford. He was afterwards at Eton College and New College, Oxford...

, in 1969, estimated the death rate to be at around one third of the population. Jeremy Goldberg

Jeremy Goldberg

Peter Jeremy Piers Goldberg is an English historian. He is Reader in Medieval History at the University of York. Goldberg was educated at the University of York and at the University of Cambridge. His main interest lies within the social and cultural history of late medieval England, in particular...

, in 1996, believed a number closer to 45% would be more realistic. A 2004 study by Ole Jørgen Benedictow

Ole Jørgen Benedictow

Ole Jørgen Benedictow is a Norwegian historian. Having spent his entire professional career at the University of Oslo, he is especially known for his work on plagues, especially the Black Death.-Career:...

suggests the exceptionally high mortality level of 62.5%. Assuming a population of 6 million, this estimate would correspond to 3,750,000 deaths. Such a high percentage would place England above the average that Benedictow estimates for Western Europe as a whole, of 60%. A death rate at such a high level has not been universally accepted in the historical community.

Social distribution

Russell trusted the IPMs to give a true picture of the national average, because he assumed death rates to be relatively equal across the social spectrum. This assumption has later been proven wrong, and studies of peasant plague mortality from manorManorialism

Manorialism, an essential element of feudal society, was the organizing principle of rural economy that originated in the villa system of the Late Roman Empire, was widely practiced in medieval western and parts of central Europe, and was slowly replaced by the advent of a money-based market...

rolls have returned much higher rates. This could be a consequence of the elite's ability to avoid infection by escaping plague-infected areas. It could also result from lower post-infection mortality among those more affluent, due to better access to care and nursing. If so, this would also mean that the mortality rates for the clergy who were normally better off than the general population were no higher than the average.

The manorial records offer a good opportunity to study the geographical distribution of the plague. Its impact seems to have been about the same all over England, though a place like East Anglia

East Anglia

East Anglia is a traditional name for a region of eastern England, named after an ancient Anglo-Saxon kingdom, the Kingdom of the East Angles. The Angles took their name from their homeland Angeln, in northern Germany. East Anglia initially consisted of Norfolk and Suffolk, but upon the marriage of...

, which had frequent contact with the Continent, was severely affected. On a local level, however, there were great variations. A study of the Bishop of Worcester

Bishop of Worcester

The Bishop of Worcester is the Ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Worcester in the Province of Canterbury, England. He is the head of the Diocese of Worcester in the Province of Canterbury...

's estates reveal that, while his manors of Hartlebury and Hambury had a mortality of only 19%, the manor of Aston lost as much as 80% of its population. The manor rolls are less useful for studying the demographic distribution of the mortality, since the rolls only record the heads of households, normally an adult male. Here the IPMs show us that the most vulnerable to the disease were infants and the elderly.

There seem to have been very few victims of the Black Death at higher levels of society. The only member of the royal family who can be said with any certainty to have died from the Black Death was in France at the time of her infection. Edward III's daughter Joan

Joan of England (1335-1348)

Joan of England was a daughter of King Edward III of England and his Queen, Philippa of Hainault. Joan, also known as Joanna, was born perhaps in February 1333 in the Tower of London. As a child she was placed in the care of Marie de St Pol, wife of Aymer de Valence and foundress of Pembroke...

was residing in Bordeaux

Bordeaux

Bordeaux is a port city on the Garonne River in the Gironde department in southwestern France.The Bordeaux-Arcachon-Libourne metropolitan area, has a population of 1,010,000 and constitutes the sixth-largest urban area in France. It is the capital of the Aquitaine region, as well as the prefecture...

on her way to marry Pedro of Castile

Pedro of Castile

Peter , sometimes called "the Cruel" or "the Lawful" , was the king of Castile and León from 1350 to 1369. He was the son of Alfonso XI of Castile and Maria of Portugal, daughter of Afonso IV of Portugal...

in the summer of 1348. When the plague broke out in her household she was moved to a small village nearby, but she could not avoid infection, and died there on 2 September. It is possible that the popular religious author Richard Rolle

Richard Rolle

Rolle is honored in the Church of England on January 20 and in the Episcopal Church together with Walter Hilton and Margery Kempe on September 28.-Works in print:*English Prose Treatises of Richard Rolle of Hampole, Edited by George Perry...

, who died on 30 September 1349, was another victim of the Black Death. The English philosopher William of Ockham

William of Ockham

William of Ockham was an English Franciscan friar and scholastic philosopher, who is believed to have been born in Ockham, a small village in Surrey. He is considered to be one of the major figures of medieval thought and was at the centre of the major intellectual and political controversies of...

has been mentioned as a plague victim. This, however, is an impossibility. Ockham was living in Munich

Munich

Munich The city's motto is "" . Before 2006, it was "Weltstadt mit Herz" . Its native name, , is derived from the Old High German Munichen, meaning "by the monks' place". The city's name derives from the monks of the Benedictine order who founded the city; hence the monk depicted on the city's coat...

at the time of his death, on 10 April 1347, two years before the Black Death reached that city.

Economic, social and political consequences

Among the most immediate consequences of the Black Death in England was a shortage of farm labour, and a corresponding rise in wages. The medieval world-view was unable to interpret these changes in terms of socio-economic development, and it became common to blame degrading morals instead. The landowning classes saw the rise in wage levels as a sign of social upheaval and insubordination, and reacted with coercion. In 1349, King Edward III passed the Ordinance of LabourersOrdinance of Labourers

The Ordinance of Labourers 1349 is often considered to be the start of English labour law. Along with the Statute of Labourers , it made the employment contract different from other contracts and made illegal any attempt on the part of workers to bargain collectively...

, fixing wages at pre-plague levels. The ordinance was reinforced by parliament's passing of the Statute of Labourers in 1351. The labour laws were enforced with ruthless determination over the following decades.

Peasants' Revolt

The Peasants' Revolt, Wat Tyler's Rebellion, or the Great Rising of 1381 was one of a number of popular revolts in late medieval Europe and is a major event in the history of England. Tyler's Rebellion was not only the most extreme and widespread insurrection in English history but also the...

in 1381. The revolt started in Kent and Essex in late May, and once the rebels reached London they burnt down John of Gaunt's Savoy Palace

Savoy Palace

The Savoy Palace was considered the grandest nobleman's residence of medieval London, until it was destroyed in the Peasants' Revolt of 1381. It fronted the Strand, on the site of the present Savoy Theatre and the Savoy Hotel that memorialise its name...

, and killed both the Chancellor

Lord Chancellor

The Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, or Lord Chancellor, is a senior and important functionary in the government of the United Kingdom. He is the second highest ranking of the Great Officers of State, ranking only after the Lord High Steward. The Lord Chancellor is appointed by the Sovereign...

and the Treasurer

Lord High Treasurer

The post of Lord High Treasurer or Lord Treasurer was an English government position and has been a British government position since the Act of Union of 1707. A holder of the post would be the third highest ranked Great Officer of State, below the Lord High Chancellor and above the Lord President...

. They then demanded the complete abolition of serfdom

Serfdom

Serfdom is the status of peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to Manorialism. It was a condition of bondage or modified slavery which developed primarily during the High Middle Ages in Europe and lasted to the mid-19th century...

, and were not pacified until the young King Richard II

Richard II of England

Richard II was King of England, a member of the House of Plantagenet and the last of its main-line kings. He ruled from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. Richard was a son of Edward, the Black Prince, and was born during the reign of his grandfather, Edward III...

personally intervened. The rebellion was eventually suppressed, but the social changes it promoted were already irreversible. By around 1400 serfdom was virtually extinct in England, replaced by the form of tenure called copyhold

Copyhold

At its origin in medieval England, copyhold tenure was tenure of land according to the custom of the manor, the "title deeds" being a copy of the record of the manorial court....

.

It is conspicuous how well the English government handled the crisis of the mid-fourteenth century, without descending into chaos and total collapse in the manner of the Valois government of France. To a large extent this was the accomplishment of administrators such as Treasurer

Lord High Treasurer

The post of Lord High Treasurer or Lord Treasurer was an English government position and has been a British government position since the Act of Union of 1707. A holder of the post would be the third highest ranked Great Officer of State, below the Lord High Chancellor and above the Lord President...

William de Shareshull

William de Shareshull

Sir William de Shareshull was an English lawyer, and Chief Justice of the King's Bench from 26 October 1350 to 5 July 1361.Shareshull came from relatively humble Staffordshire origins, rising to great prominence under the administration of Edward III of England; he was responsible for the 1351...

and Chief Justice

Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales

The Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales is the head of the judiciary and President of the Courts of England and Wales. Historically, he was the second-highest judge of the Courts of England and Wales, after the Lord Chancellor, but that changed as a result of the Constitutional Reform Act 2005,...

William Edington, whose highly competent leadership guided the governance of the nation through the crisis. The plague's greatest effect on the government was probably in the field of war, where no major campaigns were launched in France until 1355.

Another notable consequence of the black death was the raising of the real wage of England (due to the shortage of labour as a result of the reduction in population), a trait shared across Western Europe, which in general led to a real wage in 1450 that was unmatched in most countries until the 19th or 20th century.

Religious and cultural consequences

The omnipresence of death also inspired greater piety in the upper classes, which can be seen in the fact that three CambridgeUniversity of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public research university located in Cambridge, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest university in both the United Kingdom and the English-speaking world , and the seventh-oldest globally...

colleges were founded during or shortly after the Black Death. England did not experience the same trend of roving bands of flagellant

Flagellant

Flagellants are practitioners of an extreme form of mortification of their own flesh by whipping it with various instruments.- History :Flagellantism was a 13th and 14th centuries movement, consisting of radicals in the Catholic Church. It began as a militant pilgrimage and was later condemned by...

s, common on the continent. Neither were there any pogrom

Pogrom

A pogrom is a form of violent riot, a mob attack directed against a minority group, and characterized by killings and destruction of their homes and properties, businesses, and religious centres...

s against the Jews, since the Jews had been expelled by Edward I

Edward I of England

Edward I , also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England from 1272 to 1307. The first son of Henry III, Edward was involved early in the political intrigues of his father's reign, which included an outright rebellion by the English barons...

in 1290. In the long run, however, the increase in public participation may have served to challenge the absolute authority of the church hierarchy, and thus possibly helped pave the way for the Protestant Reformation

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led...

.

The high rate of mortality among the clergy naturally led to a shortage of priests in many parts of the country. The clergy were seen to have an elevated status among ordinary people and this was partly due to their closeness with god, being his envoys on earth. However, as the church itself had given the cause of the black death to be the impropriety of the behaviour of men, the higher death rate among the clergy lead the people to lose faith in the Church as an institution - it had proved as ineffectual against the horror of Y. Pestis as every other medieval institution. But they didn't lose their Christian faith, if anything it was renewed; they began to long for a more personal relationship with god - around the time after the black death many Chantries (private chapels) began to spread in use from not just the nobility, but to among the well to do. This change in the power of the papacy in England is demonstrated by the statutes of Praemunire

Praemunire

In English history, Praemunire or Praemunire facias was a law that prohibited the assertion or maintenance of papal jurisdiction, imperial or foreign, or some other alien jurisdiction or claim of supremacy in England, against the supremacy of the Monarch...

.

The Black Death also had a great impact on arts and culture. It was inevitable that a catastrophe of such proportions would have an impact on some of the greater building projects, as the amount of available labour fell sharply. The building of the cathedrals of Ely

Ely Cathedral

Ely Cathedral is the principal church of the Diocese of Ely, in Cambridgeshire, England, and is the seat of the Bishop of Ely and a suffragan bishop, the Bishop of Huntingdon...

and Exeter

Exeter Cathedral

Exeter Cathedral, the Cathedral Church of Saint Peter at Exeter, is an Anglican cathedral, and the seat of the Bishop of Exeter, in the city of Exeter, Devon in South West England....

was temporarily halted in the years immediately following the first outbreak of the plague. The shortage of labour also helped advance the transition from the Decorated style of building to the less elaborate Perpendicular style. The Black Death may also have promoted the use of vernacular English

English language

English is a West Germanic language that arose in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England and spread into what was to become south-east Scotland under the influence of the Anglian medieval kingdom of Northumbria...

, as the number of teachers proficient in French dwindled. This, in turn, would have contributed to the late-fourteenth century flowering of English literature, represented by writers such as Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer , known as the Father of English literature, is widely considered the greatest English poet of the Middle Ages and was the first poet to have been buried in Poet's Corner of Westminster Abbey...

and John Gower

John Gower

John Gower was an English poet, a contemporary of William Langland and a personal friend of Geoffrey Chaucer. He is remembered primarily for three major works, the Mirroir de l'Omme, Vox Clamantis, and Confessio Amantis, three long poems written in French, Latin, and English respectively, which...

.

Recurrences

Over the following decades the plague would return on a national or a regional level at intervals of five to twelve years, with gradually dwindling death tolls. Then, in the decades from 1430 to 1480, the disease returned in force. An outbreak in 1471 took as much as 10-15% of the population, while the death rate of the plague of 1479-80 could have been as high as 20%. From this point on outbreaks became fewer and more manageable. This was to a large extent the result of conscious efforts by central and local governments from the late fifteenth century onwards to curtail the disease. By the seventeenth century the Second Pandemic was over. One of its last occurrences in England was the famous Great Plague of London

Great Plague of London

The Great Plague was a massive outbreak of disease in the Kingdom of England that killed an estimated 100,000 people, 20% of London's population. The disease is identified as bubonic plague, an infection by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, transmitted through a flea vector...

in 1665-66.

See also

- Globalization and diseaseGlobalization and diseaseGlobalization, the flow of information, goods, capital and people across political and geographic boundaries, has helped to spread some of the deadliest infectious diseases known to humans. The spread of diseases across wide geographic scales has increased through history...

- Abandoned villageAbandoned villageAn abandoned village is a village that has, for some reason, been deserted. In many countries, and throughout history, thousands of villages were deserted for a variety of causes...

- Depopulation

- Medieval demographyMedieval demographyThis article discusses human demography in Europe during the Middle Ages, including population trends and movements. Demographic changes helped to shape and define the Middle Ages...

- Crisis of the Late Middle AgesCrisis of the Late Middle AgesThe Crisis of the Late Middle Ages refers to a series of events in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries that brought centuries of European prosperity and growth to a halt...

- Popular revolt in late medieval EuropePopular revolt in late medieval EuropePopular revolts in late medieval Europe were uprisings and rebellions by peasants in the countryside, or the bourgeois in towns, against nobles, abbots and kings during the upheavals of the 14th through early 16th centuries, part of a larger "Crisis of the Late Middle Ages"...

- List of Bubonic plague outbreaks

- List of epidemics