Charles Edward Magoon

Encyclopedia

Charles Edward Magoon was an American lawyer

, judge

, diplomat

, and administrator who is best remembered as a governor

of the Panama Canal Zone

, Minister to Panama, and an occupation governor of Cuba

. He was also the subject of several small scandals during his career.

As a legal advisor working for the United States Department of War

, he drafted recommendations and reports that were used by Congress

and the executive branch in governing the United States' new territories following the Spanish–American War. These reports were collected as a published book in 1902, then considered the seminal work on the subject. During his time as a governor, Magoon worked to put these recommendations into practice.

, Steele County

, Minnesota

. His family moved with him to Nebraska

when he was still a small child. In 1876, he enrolled in the "prep" program at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln

and studied there for two years before officially enrolling in 1878. He left school in 1879 to study law

independently with a prominent law firm. In 1882, he was admitted to the bar

and practiced law in Lincoln

, Nebraska

. Eventually, he was made a partner in the firm. He also became the judge advocate of the Nebraska National Guard

and continued to use the title of "Judge" throughout the remainder of his career.

, in the U.S. Department of War under Secretary of War

Russell A. Alger

.

Legal and political controversy had arisen regarding whether the people of the newly acquired territories were automatically granted the same rights under the United States Constitution

as American citizens. Magoon prepared a report to Alger in May 1899 that would have established the official departmental policy as "the Constitution follows the flag."

Under this view, the moment the treaty transferring the territories to U.S. sovereignty was signed, the residents of Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and other territories became subject to all the rights granted by the Constitution. For the new territories following the Spanish–American War, this would have been from the signing of the Treaty of Paris

on December 10, 1898. With the resignation of Secretary Alger, this incomplete report was not released to Congress.

In August 1899, Elihu Root

became the new secretary of war, and the unreleased report was scrapped. Magoon drafted a new report which came to precisely the opposite conclusion from the first: the Constitution did not apply in new territories until the United States Congress specifically passed legislation to authorize it. It argued that precedent was set when Congress passed legislation to apply the Constitution to the Northwest Territory

and the Louisiana Purchase

. This revised report was dated February 12, 1900, and released to Congress as a policy document expressing the Department's official stance on the issue. This view was largely adopted by the Supreme Court of the United States

beginning in 1901 in the so-called "Insular Cases

."

During this period, Congress was debating a Puerto Rico Tariff Act that would have been unconstitutional had the first definition been kept. This was a largely partisan issue at the time—the Republicans

were in favor of this Act, but it was strongly denounced by Democrats

. During the ensuing debate, the existence of the original report was discovered by the Democrats, who requested that the War Department release the earlier report to them so they could be compared "side by side". The request was refused, but a copy of the report was leaked, allowing Minority Leader

James D. Richardson

to read it aloud on the Senate

floor, prior to the vote. These efforts failed; the vote remained along party lines and the measure was passed.

This small scandal, with Magoon at the center, was termed the "Magoon Incident" by the Chicago Tribune

and resulted in harsh words against him from both parties. Fellow Republicans urged that Magoon was only a "subordinate clerk", with no right to express any opinion except the opinion of the Department, and therefore the first report should carry no weight. Democrats similarly were against the second version of the report. It is unclear which version, if any, actually represented Magoon's personal views rather than the views of the current secretary of war.

After this incident, Magoon remained with the Department of War. In 1902, his work on the legal foundations of the new civil governments was released to the public as a book, Reports on The Law of Civil Government in Territory Subject to Military Occupation by the Military Forces of the United States, etc. It was reprinted several times and was considered the seminal text on the subject.

in June 1904 to be the general counsel

for the Isthmian Canal Commission

, the group working toward what would eventually become the Panama Canal

. In this role, he would be working under Chairman John G. Walker, but would not be a commissioner. According to President Roosevelt, Magoon deserved the position because he had "won his spurs" working in the War Department and was well respected. Although Magoon was working for the Canal project, his office and residence remained in Washington, DC.

On March 29, 1905, President Roosevelt unexpectedly called for the simultaneous resignations of all members of the Canal Commission and the governor of the Panama Canal Zone, George Whitefield Davis

. According to Secretary of War William Howard Taft

, this clean sweep was due to the "inherent clumsiness" of the Commission, especially as related to sanitary problems in the Zone, as well as the difficulty of reaching consensus between the current seven commissioners. Several days later, replacement appointments were announced: Magoon was appointed both governor and a member of the Commission, with railroad entrepreneur Theodore P. Shonts made chairman of the Commission. The new Commission had seven commissioners, as required by the act of Congress that created the body, but responsibilities were to be split such that only Magoon, Shonts, and the chief engineer had any real authority. The remaining four members of the commission were appointed only to fulfil the letter of the law. Congress had already rejected a request by the President to formally make the Commission a three-member body; restructuring the organization was an end-run by the President around that restriction. In order to assume his new duties, Magoon relocated to the Canal Zone the following month.

Magoon's primary responsibilities within the Canal Zone were to improve sanitation and to deal with the all-too-common outbreaks of yellow fever

Magoon's primary responsibilities within the Canal Zone were to improve sanitation and to deal with the all-too-common outbreaks of yellow fever

and malaria

. At first, he refused to believe that the diseases were carried by mosquitos because, he reasoned, the native population would have been more affected. At this time, the nature of human acquired immunity to diseases was not well understood. The Chicago Tribune, in an article about conditions in the canal, referred to the notion that yellow fever was carried by mosquitos as "bugaboo". However, by January 1906, Magoon had long come to understand the role of misquitos in the transmission of dieases, as evidenced in a New York Times article wherein Magoon addressed criticisms of his administration in detail; by then he had undertaken a vigorous and ambitious plan to eliminate the swamps that bred misquitos.

While governor, he worked with translators in the War Department to publish an English edition of the complete Civil Code

of Panama

, which he codified as the law of the Canal Zone on May 9, 1904. This was the first time that the complete civil code of a Spanish

-speaking country not a U.S. territory had been translated into English. It was significant that he did not make changes to these laws when "importing" them into the legal system of the territory that he governed.

On July 2, 1905, President Roosevelt further consolidated power in Panama by appointing Magoon Minister to Panama

, to replace John Barrett

. This put Magoon in the unique position of being both a governor of a U.S. territory and a diplomat to the country of which that territory was an enclave. During the tenure of Governor Davis, there had been friction between him and Minister Barrett. This double appointment would ensure that the two roles could not work at cross-purposes. Magoon would draw two salaries in the arrangement, an issue which would come up later to haunt him. With influential posts in both Panama proper and the Canal Zone, Magoon was an exceptionally powerful man on the Isthmus.

, a lecturer and writer for the American Geographical Society

, who wrote a scathing report on progress in the Canal Zone—a report that was well-publicized in the States. This report criticized the efficiency of the work being performed as well as the quality of its management. Magoon countered this negative press by stressing that Bigelow had visited the Zone for less than two days, one of which was Thanksgiving Day, and that work was naturally lax on the holiday.

In February, Magoon was called to testify before the Senate Committee responsible for Canal administration, including responding to Bigelow's report. He was criticized now for the earlier adoption of Panama's penal system in the Zone. One major point of contention was that it did not allow for trial by jury

for American citizens arrested there. They raised questions as to the quality of the judges in the territory and other issues.

There was no official outcome from these hearings, but Congress subsequently passed a Consular Reform Bill which included a provision that specifically would not allow a diplomat, such as Magoon, to hold a separate administrative position. Rather than remove Magoon from one of his positions, he was named to become vice governor-general of the Philippines

. Ultimately, this offer was rescinded before it could take effect, and he was instead appointed governor of Cuba.

The best coverage of Magoon's work in Panama can be found in: Mellander, Gustavo A.; Nelly Maldonado Mellander (1999). Charles Edward Magoon: The Panama Years. Río Piedras, Puerto Rico: Editorial Plaza Mayor. ISBN 1-56328-155-4. OCLC 42970390

of 1901, a bill stipulating the degree of United States intervention in Cuba, which was negotiated with the Cubans during the U.S. occupation of 1899–1902. After a brief period of stabilization by Secretary Taft, Magoon was appointed governor under the Constitution of Cuba, effectively with absolute authority and backed by the U.S. military.

On October 13, 1906, Magoon officially became Cuban governor. Magoon declined to have an official inauguration ceremony, and, instead, news of the appointment was announced to the Cuban public via the newspapers. In his written appointment address to the country, Magoon indicated that he would "perform the duties provided for by the ... constitution of Cuba for the preservation of Cuban independence". He was there, in short, to restore order and not to colonize.

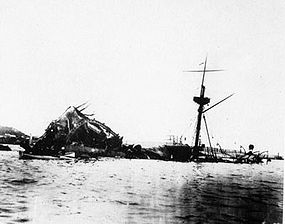

During Magoon's time as governor, the remaining revolutionaries were defeated, and his attention was turned inward to infrastructure. He coordinated the construction of two hundred kilometers of highway. He called for the reorganization of the Cuban military into a formal army, rather than a Mexican

During Magoon's time as governor, the remaining revolutionaries were defeated, and his attention was turned inward to infrastructure. He coordinated the construction of two hundred kilometers of highway. He called for the reorganization of the Cuban military into a formal army, rather than a Mexican

-style "rural guard". More controversially, he called for the removal of the sunken USS Maine

, the ship whose destruction led to the Spanish–American War, because it was interfering with traffic in Havana

's harbor. In his yearly report to the secretary of war, Magoon reported that many Cubans held the popular belief that neither the United States nor the US-backed Cuban government had explored the wreckage because evidence might be found to suggest that the ship was not sunk by a torpedo

, as was the official report—something that would cast doubt on the justification for the United States' war against Spain. The removal of the ship would not happen while Magoon was in office; it was to be authorized by Congress in 1910.

While he was well regarded in the United States, Magoon was not popular amongst Cubans. He reaped a vast number of lurid accusations at the hands of Cuban writers who described him as a "man of wax", who was "gross in character, rude in manners, of a profound ambition and greedy for despoilment". The Cuban scholar Carlos Manuel Trelles later wrote that Magoon "profoundly corrupted the Cuban nation, and on account of his venality was looked upon with contempt." Other Cuban historians point to the fiscal wastefulness of Magoon's tenure, which "left a bad memory and a bad example to the country" and returned Cuba to the corrupt practices of colonial times.

On January 29, 1909, the fully sovereign government of Cuba was restored, and José Miguel Gómez

became president. No explicit evidence of Magoon's corruption ever surfaced, but his parting gesture of issuing lucrative Cuban contracts to U.S. firms was a continued point of contention. Several months later, Magoon received an official commendation from President Taft for his excellent service in Cuba.

Following his service in Cuba, Magoon retired from public service and vacationed for a year in Europe before returning to the United States. Speculation at the time pointed to him taking a position as ambassador to China, a special commission on stability in Central America, or a Cabinet position. Ultimately Magoon did not take up any of those new responsibilities and formally entered retirement. He died in Washington, D.C., in 1920 after complications from surgery for acute appendicitis.

Lawyer

A lawyer, according to Black's Law Dictionary, is "a person learned in the law; as an attorney, counsel or solicitor; a person who is practicing law." Law is the system of rules of conduct established by the sovereign government of a society to correct wrongs, maintain the stability of political...

, judge

Judge

A judge is a person who presides over court proceedings, either alone or as part of a panel of judges. The powers, functions, method of appointment, discipline, and training of judges vary widely across different jurisdictions. The judge is supposed to conduct the trial impartially and in an open...

, diplomat

Diplomat

A diplomat is a person appointed by a state to conduct diplomacy with another state or international organization. The main functions of diplomats revolve around the representation and protection of the interests and nationals of the sending state, as well as the promotion of information and...

, and administrator who is best remembered as a governor

Governor

A governor is a governing official, usually the executive of a non-sovereign level of government, ranking under the head of state...

of the Panama Canal Zone

Panama Canal Zone

The Panama Canal Zone was a unorganized U.S. territory located within the Republic of Panama, consisting of the Panama Canal and an area generally extending 5 miles on each side of the centerline, but excluding Panama City and Colón, which otherwise would have been partly within the limits of...

, Minister to Panama, and an occupation governor of Cuba

Cuba

The Republic of Cuba is an island nation in the Caribbean. The nation of Cuba consists of the main island of Cuba, the Isla de la Juventud, and several archipelagos. Havana is the largest city in Cuba and the country's capital. Santiago de Cuba is the second largest city...

. He was also the subject of several small scandals during his career.

As a legal advisor working for the United States Department of War

United States Department of War

The United States Department of War, also called the War Department , was the United States Cabinet department originally responsible for the operation and maintenance of the United States Army...

, he drafted recommendations and reports that were used by Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

and the executive branch in governing the United States' new territories following the Spanish–American War. These reports were collected as a published book in 1902, then considered the seminal work on the subject. During his time as a governor, Magoon worked to put these recommendations into practice.

Early life

Magoon was born in OwatonnaOwatonna, Minnesota

Owatonna is a city in Steele County, Minnesota, United States. The population was 25,599 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Steele County. Owatonna is home to the Steele County Fairgrounds, which hosts the Steele County Free Fair in August....

, Steele County

Steele County, Minnesota

As of the census of 2000, there were 33,680 people, 12,846 households, and 9,082 families residing in the county. The population density was 78 people per square mile . There were 13,306 housing units at an average density of 31 per square mile...

, Minnesota

Minnesota

Minnesota is a U.S. state located in the Midwestern United States. The twelfth largest state of the U.S., it is the twenty-first most populous, with 5.3 million residents. Minnesota was carved out of the eastern half of the Minnesota Territory and admitted to the Union as the thirty-second state...

. His family moved with him to Nebraska

Nebraska

Nebraska is a state on the Great Plains of the Midwestern United States. The state's capital is Lincoln and its largest city is Omaha, on the Missouri River....

when he was still a small child. In 1876, he enrolled in the "prep" program at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln

University of Nebraska–Lincoln

The University of Nebraska–Lincoln is a public research university located in the city of Lincoln in the U.S. state of Nebraska...

and studied there for two years before officially enrolling in 1878. He left school in 1879 to study law

Law

Law is a system of rules and guidelines which are enforced through social institutions to govern behavior, wherever possible. It shapes politics, economics and society in numerous ways and serves as a social mediator of relations between people. Contract law regulates everything from buying a bus...

independently with a prominent law firm. In 1882, he was admitted to the bar

Admission to the bar in the United States

In the United States, admission to the bar is the granting of permission by a particular court system to a lawyer to practice law in that system. Each U.S. state and similar jurisdiction has its own court system and sets its own rules for bar admission , which can lead to different admission...

and practiced law in Lincoln

Lincoln, Nebraska

The City of Lincoln is the capital and the second-most populous city of the US state of Nebraska. Lincoln is also the county seat of Lancaster County and the home of the University of Nebraska. Lincoln's 2010 Census population was 258,379....

, Nebraska

Nebraska

Nebraska is a state on the Great Plains of the Midwestern United States. The state's capital is Lincoln and its largest city is Omaha, on the Missouri River....

. Eventually, he was made a partner in the firm. He also became the judge advocate of the Nebraska National Guard

Nebraska National Guard

The Nebraska National Guard consists of the:*Nebraska Army National Guard*Nebraska Air National Guard-External links:* compiled by the United States Army Center of Military History...

and continued to use the title of "Judge" throughout the remainder of his career.

War Department and the "Magoon Incident"

By 1899, Magoon was sought out to join the law office of the newly created Division of Customs and Insular Affairs, later renamed the Bureau of Insular AffairsBureau of Insular Affairs

The Bureau of Insular Affairs was a division of the United States War Department that oversaw United States administration of certain territories from 1902 until 1939....

, in the U.S. Department of War under Secretary of War

United States Secretary of War

The Secretary of War was a member of the United States President's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War," was appointed to serve the Congress of the Confederation under the Articles of Confederation...

Russell A. Alger

Russell A. Alger

Russell Alexander Alger was the 20th Governor and U.S. Senator from the state of Michigan and also U.S. Secretary of War during the Presidential administration of William McKinley...

.

Legal and political controversy had arisen regarding whether the people of the newly acquired territories were automatically granted the same rights under the United States Constitution

United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It is the framework for the organization of the United States government and for the relationship of the federal government with the states, citizens, and all people within the United States.The first three...

as American citizens. Magoon prepared a report to Alger in May 1899 that would have established the official departmental policy as "the Constitution follows the flag."

Under this view, the moment the treaty transferring the territories to U.S. sovereignty was signed, the residents of Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and other territories became subject to all the rights granted by the Constitution. For the new territories following the Spanish–American War, this would have been from the signing of the Treaty of Paris

Treaty of Paris (1898)

The Treaty of Paris of 1898 was signed on December 10, 1898, at the end of the Spanish-American War, and came into effect on April 11, 1899, when the ratifications were exchanged....

on December 10, 1898. With the resignation of Secretary Alger, this incomplete report was not released to Congress.

In August 1899, Elihu Root

Elihu Root

Elihu Root was an American lawyer and statesman and the 1912 recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize. He was the prototype of the 20th century "wise man", who shuttled between high-level government positions in Washington, D.C...

became the new secretary of war, and the unreleased report was scrapped. Magoon drafted a new report which came to precisely the opposite conclusion from the first: the Constitution did not apply in new territories until the United States Congress specifically passed legislation to authorize it. It argued that precedent was set when Congress passed legislation to apply the Constitution to the Northwest Territory

Northwest Territory

The Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, more commonly known as the Northwest Territory, was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 13, 1787, until March 1, 1803, when the southeastern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state of Ohio...

and the Louisiana Purchase

Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase was the acquisition by the United States of America of of France's claim to the territory of Louisiana in 1803. The U.S...

. This revised report was dated February 12, 1900, and released to Congress as a policy document expressing the Department's official stance on the issue. This view was largely adopted by the Supreme Court of the United States

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

beginning in 1901 in the so-called "Insular Cases

Insular Cases

The Insular Cases are several U.S. Supreme Court cases concerning the status of territories acquired by the U.S. in the Spanish-American War . The name "insular" derives from the fact that these territories are islands and were administered by the War Department's Bureau of Insular Affairs...

."

During this period, Congress was debating a Puerto Rico Tariff Act that would have been unconstitutional had the first definition been kept. This was a largely partisan issue at the time—the Republicans

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

were in favor of this Act, but it was strongly denounced by Democrats

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

. During the ensuing debate, the existence of the original report was discovered by the Democrats, who requested that the War Department release the earlier report to them so they could be compared "side by side". The request was refused, but a copy of the report was leaked, allowing Minority Leader

Minority leader

In U.S. politics, the minority leader is the floor leader of the second largest caucus in a legislative body. Given the two-party nature of the U.S. system, the minority leader is almost inevitably either a Republican or a Democrat, with their counterpart being of the opposite party. The position...

James D. Richardson

James D. Richardson

James Daniel Richardson was an American politician and a Democrat from Tennessee. Richardson represented Tennessee's 5th congressional district in the United States House of Representatives from 1885 through 1905. He was among the earliest U.S...

to read it aloud on the Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

floor, prior to the vote. These efforts failed; the vote remained along party lines and the measure was passed.

This small scandal, with Magoon at the center, was termed the "Magoon Incident" by the Chicago Tribune

Chicago Tribune

The Chicago Tribune is a major daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, and the flagship publication of the Tribune Company. Formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper" , it remains the most read daily newspaper of the Chicago metropolitan area and the Great Lakes region and is...

and resulted in harsh words against him from both parties. Fellow Republicans urged that Magoon was only a "subordinate clerk", with no right to express any opinion except the opinion of the Department, and therefore the first report should carry no weight. Democrats similarly were against the second version of the report. It is unclear which version, if any, actually represented Magoon's personal views rather than the views of the current secretary of war.

After this incident, Magoon remained with the Department of War. In 1902, his work on the legal foundations of the new civil governments was released to the public as a book, Reports on The Law of Civil Government in Territory Subject to Military Occupation by the Military Forces of the United States, etc. It was reprinted several times and was considered the seminal text on the subject.

Panama

In late 1903, Secretary Root announced that he was retiring as secretary of war. Speculation followed in the media that Magoon would retire simultaneously and join the outgoing secretary in private practice. Instead, Magoon was appointed by President Theodore RooseveltTheodore Roosevelt

Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt was the 26th President of the United States . He is noted for his exuberant personality, range of interests and achievements, and his leadership of the Progressive Movement, as well as his "cowboy" persona and robust masculinity...

in June 1904 to be the general counsel

General Counsel

A general counsel is the chief lawyer of a legal department, usually in a corporation or government department. The term is most used in the United States...

for the Isthmian Canal Commission

Isthmian Canal Commission

The Isthmian Canal Commission was an American administration commission set up to oversee the construction of the Panama Canal in the early years of American involvement. Established in 1904, it was given control of the Panama Canal Zone over which the United States exercised sovereignty...

, the group working toward what would eventually become the Panama Canal

Panama Canal

The Panama Canal is a ship canal in Panama that joins the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean and is a key conduit for international maritime trade. Built from 1904 to 1914, the canal has seen annual traffic rise from about 1,000 ships early on to 14,702 vessels measuring a total of 309.6...

. In this role, he would be working under Chairman John G. Walker, but would not be a commissioner. According to President Roosevelt, Magoon deserved the position because he had "won his spurs" working in the War Department and was well respected. Although Magoon was working for the Canal project, his office and residence remained in Washington, DC.

On March 29, 1905, President Roosevelt unexpectedly called for the simultaneous resignations of all members of the Canal Commission and the governor of the Panama Canal Zone, George Whitefield Davis

George Whitefield Davis

George Whitefield Davis was an engineer and Major General in the United States Army. He also served as a military Governor of Puerto Rico and as the first military Governor of the Panama Canal Zone.-Civil War:...

. According to Secretary of War William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft was the 27th President of the United States and later the tenth Chief Justice of the United States...

, this clean sweep was due to the "inherent clumsiness" of the Commission, especially as related to sanitary problems in the Zone, as well as the difficulty of reaching consensus between the current seven commissioners. Several days later, replacement appointments were announced: Magoon was appointed both governor and a member of the Commission, with railroad entrepreneur Theodore P. Shonts made chairman of the Commission. The new Commission had seven commissioners, as required by the act of Congress that created the body, but responsibilities were to be split such that only Magoon, Shonts, and the chief engineer had any real authority. The remaining four members of the commission were appointed only to fulfil the letter of the law. Congress had already rejected a request by the President to formally make the Commission a three-member body; restructuring the organization was an end-run by the President around that restriction. In order to assume his new duties, Magoon relocated to the Canal Zone the following month.

Governor of Panama Canal Zone

Yellow fever

Yellow fever is an acute viral hemorrhagic disease. The virus is a 40 to 50 nm enveloped RNA virus with positive sense of the Flaviviridae family....

and malaria

Malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease of humans and other animals caused by eukaryotic protists of the genus Plasmodium. The disease results from the multiplication of Plasmodium parasites within red blood cells, causing symptoms that typically include fever and headache, in severe cases...

. At first, he refused to believe that the diseases were carried by mosquitos because, he reasoned, the native population would have been more affected. At this time, the nature of human acquired immunity to diseases was not well understood. The Chicago Tribune, in an article about conditions in the canal, referred to the notion that yellow fever was carried by mosquitos as "bugaboo". However, by January 1906, Magoon had long come to understand the role of misquitos in the transmission of dieases, as evidenced in a New York Times article wherein Magoon addressed criticisms of his administration in detail; by then he had undertaken a vigorous and ambitious plan to eliminate the swamps that bred misquitos.

While governor, he worked with translators in the War Department to publish an English edition of the complete Civil Code

Civil code

A civil code is a systematic collection of laws designed to comprehensively deal with the core areas of private law. A jurisdiction that has a civil code generally also has a code of civil procedure...

of Panama

Panama

Panama , officially the Republic of Panama , is the southernmost country of Central America. Situated on the isthmus connecting North and South America, it is bordered by Costa Rica to the northwest, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north and the Pacific Ocean to the south. The...

, which he codified as the law of the Canal Zone on May 9, 1904. This was the first time that the complete civil code of a Spanish

Spanish language

Spanish , also known as Castilian , is a Romance language in the Ibero-Romance group that evolved from several languages and dialects in central-northern Iberia around the 9th century and gradually spread with the expansion of the Kingdom of Castile into central and southern Iberia during the...

-speaking country not a U.S. territory had been translated into English. It was significant that he did not make changes to these laws when "importing" them into the legal system of the territory that he governed.

On July 2, 1905, President Roosevelt further consolidated power in Panama by appointing Magoon Minister to Panama

United States Ambassador to Panama

The United States has maintained diplomatic relations with Panama since its independence from Colombia in 1903. The rank of the US chief of mission to Panama was originally Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary, but it was upgraded to Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary in...

, to replace John Barrett

John Barrett (diplomat)

John Barrett was a United States diplomat and one of the most influential early directors general of the Pan American Union. On his death, the New York Times commented that he had "done more than any other person of his generation to promote closer relations among the American...

. This put Magoon in the unique position of being both a governor of a U.S. territory and a diplomat to the country of which that territory was an enclave. During the tenure of Governor Davis, there had been friction between him and Minister Barrett. This double appointment would ensure that the two roles could not work at cross-purposes. Magoon would draw two salaries in the arrangement, an issue which would come up later to haunt him. With influential posts in both Panama proper and the Canal Zone, Magoon was an exceptionally powerful man on the Isthmus.

Friction with Congress

The President was coming into increasing conflict with Congress on the handling of the Zone, including the unusual consolidation of power. In addition to not officially restructuring the Commission, Congress increasingly fought or raised questions about the appointments of replacement commissioners. In November 1905, Panama was visited by Poultney BigelowPoultney Bigelow

Poultney Bigelow was an American journalist and author.He was born in New York City, the fourth of eight children of John Bigelow, co-owner of the New York Evening Post, and his wife Jane Tunis Poultney....

, a lecturer and writer for the American Geographical Society

American Geographical Society

The American Geographical Society is an organization of professional geographers, founded in 1851 in New York City. Most fellows of the society are Americans, but among them have always been a significant number of fellows from around the world...

, who wrote a scathing report on progress in the Canal Zone—a report that was well-publicized in the States. This report criticized the efficiency of the work being performed as well as the quality of its management. Magoon countered this negative press by stressing that Bigelow had visited the Zone for less than two days, one of which was Thanksgiving Day, and that work was naturally lax on the holiday.

In February, Magoon was called to testify before the Senate Committee responsible for Canal administration, including responding to Bigelow's report. He was criticized now for the earlier adoption of Panama's penal system in the Zone. One major point of contention was that it did not allow for trial by jury

Trial by Jury

Trial by Jury is a comic opera in one act, with music by Arthur Sullivan and libretto by W. S. Gilbert. It was first produced on 25 March 1875, at London's Royalty Theatre, where it initially ran for 131 performances and was considered a hit, receiving critical praise and outrunning its...

for American citizens arrested there. They raised questions as to the quality of the judges in the territory and other issues.

There was no official outcome from these hearings, but Congress subsequently passed a Consular Reform Bill which included a provision that specifically would not allow a diplomat, such as Magoon, to hold a separate administrative position. Rather than remove Magoon from one of his positions, he was named to become vice governor-general of the Philippines

Philippines

The Philippines , officially known as the Republic of the Philippines , is a country in Southeast Asia in the western Pacific Ocean. To its north across the Luzon Strait lies Taiwan. West across the South China Sea sits Vietnam...

. Ultimately, this offer was rescinded before it could take effect, and he was instead appointed governor of Cuba.

The best coverage of Magoon's work in Panama can be found in: Mellander, Gustavo A.; Nelly Maldonado Mellander (1999). Charles Edward Magoon: The Panama Years. Río Piedras, Puerto Rico: Editorial Plaza Mayor. ISBN 1-56328-155-4. OCLC 42970390

Cuba

In 1906, Cuba was in the midst of a constitutional crisis as a result of a disputed election and an attempt by elected President Tomás Estrada Palma to stay in power after the conclusion of his term. This led to a revolt, and the U.S. military sent in 5,600 men to reassert control over the country. This was permitted under the Platt amendmentPlatt Amendment

The Platt Amendment of 1901 was a rider appended to the Army Appropriations Act presented to the U.S. Senate by Connecticut Republican Senator Orville H. Platt replacing the earlier Teller Amendment. Approved on May 22, 1903, it stipulated the conditions for the withdrawal of United States troops...

of 1901, a bill stipulating the degree of United States intervention in Cuba, which was negotiated with the Cubans during the U.S. occupation of 1899–1902. After a brief period of stabilization by Secretary Taft, Magoon was appointed governor under the Constitution of Cuba, effectively with absolute authority and backed by the U.S. military.

On October 13, 1906, Magoon officially became Cuban governor. Magoon declined to have an official inauguration ceremony, and, instead, news of the appointment was announced to the Cuban public via the newspapers. In his written appointment address to the country, Magoon indicated that he would "perform the duties provided for by the ... constitution of Cuba for the preservation of Cuban independence". He was there, in short, to restore order and not to colonize.

Mexico

The United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

-style "rural guard". More controversially, he called for the removal of the sunken USS Maine

USS Maine (ACR-1)

USS Maine was the United States Navy's second commissioned pre-dreadnought battleship, although she was originally classified as an armored cruiser. She is best known for her catastrophic loss in Havana harbor. Maine had been sent to Havana, Cuba to protect U.S. interests during the Cuban revolt...

, the ship whose destruction led to the Spanish–American War, because it was interfering with traffic in Havana

Havana

Havana is the capital city, province, major port, and leading commercial centre of Cuba. The city proper has a population of 2.1 million inhabitants, and it spans a total of — making it the largest city in the Caribbean region, and the most populous...

's harbor. In his yearly report to the secretary of war, Magoon reported that many Cubans held the popular belief that neither the United States nor the US-backed Cuban government had explored the wreckage because evidence might be found to suggest that the ship was not sunk by a torpedo

Torpedo

The modern torpedo is a self-propelled missile weapon with an explosive warhead, launched above or below the water surface, propelled underwater towards a target, and designed to detonate either on contact with it or in proximity to it.The term torpedo was originally employed for...

, as was the official report—something that would cast doubt on the justification for the United States' war against Spain. The removal of the ship would not happen while Magoon was in office; it was to be authorized by Congress in 1910.

While he was well regarded in the United States, Magoon was not popular amongst Cubans. He reaped a vast number of lurid accusations at the hands of Cuban writers who described him as a "man of wax", who was "gross in character, rude in manners, of a profound ambition and greedy for despoilment". The Cuban scholar Carlos Manuel Trelles later wrote that Magoon "profoundly corrupted the Cuban nation, and on account of his venality was looked upon with contempt." Other Cuban historians point to the fiscal wastefulness of Magoon's tenure, which "left a bad memory and a bad example to the country" and returned Cuba to the corrupt practices of colonial times.

On January 29, 1909, the fully sovereign government of Cuba was restored, and José Miguel Gómez

José Miguel Gómez

José Miguel Gómez y Gómez was a Cuban General in the Cuban War of Independence who went on to become President of Cuba.-Early career:...

became president. No explicit evidence of Magoon's corruption ever surfaced, but his parting gesture of issuing lucrative Cuban contracts to U.S. firms was a continued point of contention. Several months later, Magoon received an official commendation from President Taft for his excellent service in Cuba.

Following his service in Cuba, Magoon retired from public service and vacationed for a year in Europe before returning to the United States. Speculation at the time pointed to him taking a position as ambassador to China, a special commission on stability in Central America, or a Cabinet position. Ultimately Magoon did not take up any of those new responsibilities and formally entered retirement. He died in Washington, D.C., in 1920 after complications from surgery for acute appendicitis.

External links

- Inventory of the Charles Edward Magoon Papers, 1900-1914, 1998?, in the Southern Historical CollectionSouthern Historical CollectionThe Southern Historical Collection is a repository of distinct archival collections at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill which document the culture and history of the American South...

, UNC-Chapel HillUniversity of North Carolina at Chapel HillThe University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill is a public research university located in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, United States... - Magoon Family Crest and Name History