Charles Tupper

Encyclopedia

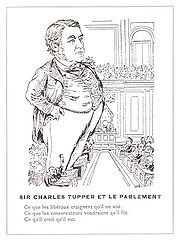

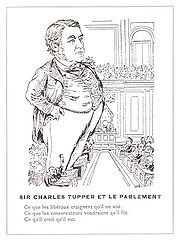

Sir Charles Tupper, 1st Baronet, GCMG

, CB

, PC

(July 2, 1821 – October 30, 1915) was a Canadian father of Confederation: as the Premier of Nova Scotia

from 1864 to 1867, he led Nova Scotia

into Confederation

. He later went on to serve as the sixth Prime Minister of Canada

, sworn in to office on May 1, 1896, seven days after parliament had been dissolved. He would go on to lose the June 23 election, resigning on July 8, 1896. His 69-day term as prime minister is currently the shortest in Canadian history. At age 74, in May 1896, he was also the oldest person to serve as Prime Minister of Canada.

Born in Amherst, Nova Scotia

in 1821, Tupper was trained as a physician

and practiced medicine periodically throughout his political career (and served as the first president of the Canadian Medical Association

). He entered Nova Scotian politics in 1855 as a protege of James William Johnston

. During Johnston's tenure as premier of Nova Scotia in 1857–59 and 1863–64, Tupper served as provincial secretary

. Tupper replaced Johnston as premier in 1864. As premier, Tupper established public education

in Nova Scotia. He also worked to expand Nova Scotia's railway network in order to promote industry.

By 1860, Tupper supported a union of all the colonies of British North America

. Believing that immediate union of all the colonies was impossible, in 1864, he proposed a Maritime Union

. However, representatives of the Province of Canada

asked to be allowed to attend the meeting in Charlottetown

scheduled to discuss Maritime Union in order to present a proposal for a wider union, and the Charlottetown Conference

thus became the first of the three conferences that secured Canadian Confederation

. Tupper also represented Nova Scotia at the other two conferences, the Quebec Conference

(1864) and the London Conference of 1866

. In Nova Scotia, Tupper organized a Confederation Party

to combat the activities of the Anti-Confederation Party

organized by Joseph Howe

and successfully led Nova Scotia into Confederation.

Following the passage of the British North America Act in 1867, Tupper resigned as premier of Nova Scotia and began a career in federal politics. He held multiple cabinet

positions under Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald

, including President of the Queen's Privy Council for Canada

(1870–72), Minister of Inland Revenue

(1872–73), Minister of Customs

(1873–74), Minister of Public Works

(1878–79), and Minister of Railways and Canals

(1879–84). Initially groomed as Macdonald's successor, Tupper had a falling out with Macdonald, and by the early 1880s, he asked Macdonald to appoint him as Canadian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom. Tupper took up his post in London

in 1883, and would remain High Commissioner until 1895, although in 1887–88, he served as Minister of Finance

without relinquishing the High Commissionership.

In 1895, the government of Sir Mackenzie Bowell

floundered over the Manitoba Schools Question

; as a result, several leading members of the Conservative Party of Canada

demanded the return of Tupper to serve as prime minister. Tupper accepted this invitation and returned to Canada, becoming prime minister in May 1896. An election was called

, just before he was sworn in as prime minister, which his party subsequently lost to Wilfrid Laurier

and the Liberals

. Tupper served as Leader of the Opposition from July 1896 until 1900, at which point he returned to London, where he lived until his death in 1915.

to Charles Tupper, Sr. and Miriam Lowe Lockhart Buckner. His father was the co-pastor

of the local Baptist church. Beginning in 1837, at age 16, Tupper attended the Horton Academy in Wolfville, Nova Scotia

, where he learned Latin

, Greek

, and some French

. After graduating in 1839, he spent some time in New Brunswick

working as a teacher, before moving to Windsor, Nova Scotia

to spend 1839–40 studying medicine

with Dr. Ebenezer Fitch Harding. Borrowing money, he then moved to Scotland

to study at the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh

at the University of Edinburgh

: he received his MD

in 1843. During his time in Edinburgh

, Tupper's commitment to his Baptist faith faltered, and he drank Scotch whisky

for the first time.

Returning to Nova Scotia, in 1846, he broke off an engagement that he had contracted with the daughter of a wealthy Halifax merchant when he was 17 years old and instead married Frances Morse

(1826–1912), the granddaughter of Col. Joseph Morse, one of the founders of Amherst, Nova Scotia

. The Tuppers had three sons (Orin Stewart, Charles Hibbert

, and William Johnston

) and three daughters (Emma, Elizabeth Stewart (Lilly), and Sophy Almon). The Tupper children were raised in Frances' Anglican denomination and John and Frances regularly worshipped in an Anglican church, though on the campaign trail, Tupper often found time to visit Baptist meetinghouses.

Tupper set himself up as a physician in Amherst, Nova Scotia and opened a drugstore

.

, James William Johnston

, a fellow Baptist and family friend of the Tuppers, encouraged Charles Tupper to enter politics. As such, in 1855, Tupper ran against the prominent Liberal politician Joseph Howe

for the Cumberland County

seat in the Nova Scotia House of Assembly

. Joseph Howe would be a frequent political opponent of Tupper the years to come.

Although Tupper won his seat, the 1855 election was an overall disaster for the Nova Scotia Conservatives, with the Liberals, led by William Young

, winning a large majority. Young consequently became Premier of Nova Scotia

.

At a caucus

meeting in January 1856, Tupper recommended a new direction for the Conservative party: they should begin actively courting Nova Scotia's Roman Catholic minority and should eagerly embrace railroad construction. Having just led his party into a disastrous election campaign, Johnston decided to basically cede control of the party to Tupper, though Johnston remained the party's leader. In the course of 1856, Tupper led Conservative attacks on the government, leading to Joseph Howe dubbing Tupper "the wicked wasp of Cumberland." In early 1857, Tupper succeeded in convincing a number of Roman Catholic Liberal members to cross the floor to join the Conservatives, reducing Young's government to the status of a minority government

. As a result, Young was forced to resign in February 1857, and the Conservatives formed a government with Johnston as premier. Tupper became the provincial secretary

.

In Tupper's first speech to the House of Assembly as provincial secretary, he set forth an ambitious plan of railroad construction. Thus, Tupper had embarked on the major theme of his political life: that Nova Scotians (and later Canadians) should downplay their ethnic and religious differences, and instead focus on developing the land's natural resources

. He argued that with Nova Scotia's "inexhaustible mines", it could become "a vast manufacturing mart" for the east coast of North America. He quickly persuaded Johnston to end the General Mining Association's monopoly over Nova Scotia minerals.

In June 1857, Tupper initiated discussions with New Brunswick

and the Province of Canada

about an intercolonial railway

. He traveled to London

in 1858 to attempt to secure imperial

backing for this project. During these discussions, Tupper found that the Canadians were more interested in discussing federal union, while the British (with the Earl of Derby

in his second term as Prime Minister

) were too absorbed in their own immediate interests. As such, nothing came of the 1858 discussions for an intercolonial railway.

An election was held in May 1859, with sectarian conflict playing a large role, with the Catholics largely supporting the Conservatives and the Protestants now shifting towards the Liberals. Tupper barely managed to retain his seat. The Conservatives were barely re-elected and lost a confidence vote later that year. Johnston asked the Governor of Nova Scotia, Lord Mulgrave

, for a dissolution

, but Mulgrave refused and invited William Young to form a government. Tupper was outraged and petitioned the British government, asking them to recall Mulgrave.

For the next three years, Tupper was ferocious in his denunciations of the Liberal government, first Young, and then Joseph Howe, who took over from Young later in 1860. This came to a head in 1863 when the Liberals introduced legislation to restrict the Nova Scotia franchise

, a move which Johnston and Tupper successfully blocked.

Tupper continued practicing medicine throughout this period. He established a successful medical practice in Halifax, rising to become the city medical officer. In 1863, he was elected president of the Medical Society of Nova Scotia.

In the June 1863 election, the Conservatives campaigned on a platform of railroad construction and expanded access to public education. The Conservatives won a huge majority, with 44 of the House of Assembly's 55 seats. Johnston resumed his duties as premier and Tupper again became provincial secretary. As a further sign of the Conservatives' commitment to non-sectarianism, in 1863, after a 20-year hiatus, Dalhousie College was re-opened as a non-denominational institution of higher learning.

In May 1864, Johnston retired from politics, accepting an appointment as a judge

, and Tupper was chosen as his successor as premier of Nova Scotia.

Tupper introduced ambitious education legislation in 1864 creating a system of state-subsidized common schools. The next year, he introduced a bill providing for compulsory local taxation to fund these schools. Although these public schools were non-denominational (whch resulted in Protestants sharply criticizing Tupper), they did include a program of Christian education. However, many Protestants, particularly fellow Baptists, felt that Tupper had sold them out. In an attempt to regain their trust, he appointed Baptist educator Theodore Harding Rand

Tupper introduced ambitious education legislation in 1864 creating a system of state-subsidized common schools. The next year, he introduced a bill providing for compulsory local taxation to fund these schools. Although these public schools were non-denominational (whch resulted in Protestants sharply criticizing Tupper), they did include a program of Christian education. However, many Protestants, particularly fellow Baptists, felt that Tupper had sold them out. In an attempt to regain their trust, he appointed Baptist educator Theodore Harding Rand

as Nova Scotia's first superintendent of education. This in turn aroused concern among Catholics, led by Archbishop Thomas-Louis Connolly

, who demanded state-funded Catholic schools. Tupper reached a compromise with Archbishop Connolly whereby Catholic-run schools could receive public funding, so long as they provided their religious instruction after hours.

Making good on his promise for expanded railroad construction, in 1864, Tupper appointed Sandford Fleming

as the chief engineer of the Nova Scotia Railway

in order to expand the line from Truro

to Pictou Landing

. He would later (Jan. 1866) award Fleming the contract to complete the line after local contractors proved too slow. Though this decision was controversial, it did result in the line from being successfully completed by May 1867. A second proposed line, from Annapolis Royal

to Windsor

initially faltered, but was eventually completed by 1869 by the privately owned Windsor & Annapolis Railway

.

entitled "The Political Condition of British North America." The title of the lecture was an homage to Lord Durham

's 1838 Report on the Affairs of British North America and served as an assessment of the condition of British North America in the two decades following Lord Durham's famous report. Although Tupper was interested in the potential economic consequences of a union with the other colonies, the bulk of his lecture addressed the place of British North America within the wider British Empire

. Having been convinced by his 1858 trip to London that British politicians were unwilling to pay attention to a small colony like Nova Scotia, Tupper argued that Nova Scotia and the other Maritime

colonies "could never hope to occupy a position of influence or importance except in connection with their larger sister Canada." As such, Tupper proposed to create a "British America", which "stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific, would in a few years exhibit to the world a great and powerful organization, with British Institutions, British sympathies, and British feelings, bound indissolubly to the throne of England

."

With the commencement of the American Civil War

With the commencement of the American Civil War

in 1861, Tupper worried that a victorious North

would turn northward and conquer the British North American provinces. This caused him to redouble his commitment to union, which he now saw as essential to protecting the British colonies against American aggression. Since he thought that full union among the British North American colonies would be unachievable for many years, on March 28, 1864, Tupper instead proposed a Maritime Union

which would unite the Maritime provinces in advance of a projected future union with the Province of Canada. A conference to discuss the proposed union of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick

and Prince Edward Island

was scheduled to be held in Charlottetown

in September 1864.

Tupper was pleasantly surprised when the Premier of the Province of Canada, John A. Macdonald

, asked to be allowed to attend the Charlottetown Conference

. The Conference, which was co-chaired by Tupper and New Brunswick Premier Samuel Leonard Tilley

, welcomed the Canadian delegation and asked them to join the conference. The conference proved to be a smashing success, and resulted in an agreement-in-principle to form a union of the four colonies.

was held on October 10, as a follow-up to the Charlottetown Conference, with Newfoundland only attending to observe. Tupper headed the Nova Scotia delegation to the Quebec Conference. He supported a legislative union of the colonies (which would mean that there would be only one legislature for the united colonies). However, the French Canadian

delegates to the conference, notably George-Étienne Cartier

and Hector-Louis Langevin

, strongly opposed the idea of a legislative union. As such, Tupper threw his weight behind Macdonald's proposal for a federal

union, which would see each colony retain its own legislature, with a central legislature in charge of common interests. Tupper argued in favour of a strong central government as a second best to a pure legislative union. However, Tupper felt that the local legislatures should retain the ability to levy duties on their natural resources.

Concerned that a united legislature would be dominated by the Province of Canada, Tupper pushed for regional representation in the upper house of the confederated colonies (a goal which would be achieved in the makeup of the Senate of Canada).

On the topic of which level of government would control customs

in the union, Tupper ultimately agreed to accept the formula by which the federal government controlled customs in exchange for an annual subsidy of 80 cents a year for each Nova Scotian. This deal was ultimately not good for Nova Scotia, which had historically received most of its government revenue from customs, and as a result, Nova Scotia entered Confederation with a deficit.

was the only member of the Liberal caucus to support Confederation. Former premier Joseph Howe now organized an Anti-Confederation Party

and anti-Confederation sentiments were so strong that Tupper decided to postpone a vote of the legislature on the question of Confederation for a full year. Tupper now organized supporters of Confederation into a Confederation Party

to push for the union.

Finally, in April 1866, Tupper secured a motion of the Nova Scotia legislature in favour of union by promising that he would renegotiate the Seventy-two Resolutions

at the upcoming conference in London Conference.

Although Tupper did attempt to renegotiate the 72 Resolutions as he had promised, he was ineffective in securing any major changes. The only major change agreed to at the London Conference was one that arguably did not benefit Nova Scotia - responsibility for the fisheries, which was going to be a joint federal-provincial responsibility under the Quebec agreement, became solely a federal concern.

.

In honour of the role he played in securing Confederation, Tupper was made a Companion in The Most Honourable Order of the Bath in 1867. As such, he was now entitled to use the postnomial letters "CB".

for the new Canadian House of Commons

were held in August–September 1867. Tupper ran as a member for the new federal riding of Cumberland

and won his seat. However, Tupper was the only pro-Confederation candidate to win a seat from Nova Scotia in the 1st Canadian Parliament

, with Joseph Howe and the Anti-Confederates winning every other seat.

As an ally of Sir John A. Macdonald and the Liberal-Conservative Party

As an ally of Sir John A. Macdonald and the Liberal-Conservative Party

, it was widely believed that Tupper would have a place in the first Cabinet of Canada

. However, when Macdonald ran into difficulties in organizing this cabinet, Tupper stepped aside in favour of Edward Kenny

. Instead, Tupper set up a medical practice in Ottawa

and was elected as the first president of the new Canadian Medical Association

, a position he held until 1870.

In November 1867, in provincial elections in Nova Scotia, the pro-Confederation Hiram Blanchard was defeated by the leader of the Anti-Confederation Party, William Annand

. Given the unpopularity of Confederation within Nova Scotia, Joseph Howe traveled to London in 1868 to attempt to persuade the British government (headed by the earl of Derby, and then after February 1868 by Benjamin Disraeli) to allow Nova Scotia to secede from Confederation. Tupper followed Howe to London where he successfully lobbied British politicians against allowing Nova Scotia to secede.

Following his victory in London, Tupper proposed a reconciliation with Howe: in exchange for Howe's agreeing to stop fighting against the union, Tupper and Howe would be allies in the fight to protect Nova Scotia's interests within Confederation. Howe agreed to Tupper's proposal and in January 1869 entered the Canadian cabinet as President of the Queen's Privy Council for Canada

.

With the outbreak of the Red River Rebellion

in 1869, Tupper was distressed to find that his daughter Emma's husband was being held hostage by Louis Riel

and the rebels. He rushed to the northwest to rescue his son-in-law.

The next year was dominated by a dispute with the U.S. regarding American access to the Atlantic fisheries. Tupper thought that the British should restrict American access to these fisheries so that they could negotiate from a position of strength. When Prime Minister Macdonald traveled to represent Canada's interests at the negotiations leading up to the Treaty of Washington (1871)

, Tupper served as Macdonald's liaison with the federal cabinet.

.

Tupper led the Nova Scotia campaign for the Liberal-Conservative party during the Canadian federal election of 1872

. His efforts paid off when Nova Scotia returned not a single Anti-Confederate Member of Parliament

to the 2nd Canadian Parliament

, and 20 of Nova Scotia's 21 MPs were Liberal-Conservatives. (The Liberal-Conservative Party changed its name to the Conservative Party

in 1873.)

In February 1873, Tupper was shifted from Inland Revenue to become Minister of Customs

In February 1873, Tupper was shifted from Inland Revenue to become Minister of Customs

, and in this position he was successful in having British weights and measures

adopted as the uniform standard for the united colonies.

He would not hold this post for long, however, as Macdonald's government was rocked by the Pacific Scandal

throughout 1873. In November 1873, the 1st Canadian Ministry was forced to resign and was replaced by the 2nd Canadian Ministry headed by Liberal

Alexander Mackenzie

.

. The 1874 election was disastrous for the Conservatives, and in Nova Scotia, Tupper was one of only two Conservative MPs returned to the 3rd Canadian Parliament

.

Though Macdonald stayed on as Conservative leader, Tupper now assumed a more prominent role in the Conservative Party and was widely seen as Macdonald's heir apparent. He led Conservative attacks on the Mackenzie government throughout the 3rd Parliament. The Mackenzie government attempted to negotiate a new free trade agreement with the United States to replace the Canadian-American Reciprocity Treaty

which the U.S. had abrogated in 1864. When Mackenzie proved unable to achieve reciprocity, Tupper began shifting towards protectionism

and became a proponent of the National Policy

which became a part of the Conservative platform

in 1876. The sincerity of Tupper's conversion to the protectionist cause was doubted at the time, however: according to one apocryphal story, when Tupper came to the 1876 debate on Finance Minister

Richard John Cartwright

's budget, he was prepared to advocate free trade

if Cartwright had announced that the Liberals had shifted their position and were now supporting protectionism.

Tupper was also deeply critical of Mackenzie's approach to railways, arguing that the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway

, which would link British Columbia

(which entered Confederation in 1871) with the rest of Canada, should be a stronger government priority than it was for Mackenzie. This position also became an integral part of the Conservative platform.

As on previous occasions when he was not in cabinet, Tupper was active in practicing medicine during the 1874–78 stint in Opposition, though he was dedicating less and less of his time to medicine during this period.

Tupper was a councillor of the Oxford Military College

in Cowley and Oxford

Oxfordshire

from 1876–1896.

Tupper again led the Conservative campaign in Nova Scotia. The Conservatives under Macdonald won a resounding majority in the election, in the process capturing 16 of Nova Scotia's 21 seats in the 4th Canadian Parliament

.

With the formation of the 3rd Canadian Ministry in October 1878, Tupper became Minister of Public Works

. His top priority was completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway, which he saw as "an Imperial Highway across the Continent of America entirely on British soil." This marked a shift in Tupper's position: although he had long argued that completion of the railway should be a major government priority, while Tupper was in Opposition, he argued that the railway should be privately constructed; he now argued that the railway ought to be completed as a public work, partly because he believed that the private sector could not complete the railroad given the recession

which gripped the country throughout the 1870s.

.

Tupper's motto as Minister of Railways and Canals was "Develop our resources." He stated "I have always supposed that the great object, in every country, and especially in a new country, was to draw as [many] capitalists into it as possible."

Tupper traveled to London in summer 1879 to attempt to persuade the British government (then headed by the earl of Beaconsfield in his second term as prime minister) to guarantee a bond

sale to be used to construct the railway. He was not successful, though he did manage to purchase 50,000 tons of steel rails at a bargain price. Tupper's old friend Sandford Fleming oversaw the railway construction, but his inability to keep costs down led to political controversy, and Tupper was forced to remove Fleming as Chief Engineer in May 1880.

1879 also saw Tupper made a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George, and thus entitled to use the postnominal letters "KCMG".

In 1880, George Stephen

In 1880, George Stephen

approached Tupper on behalf of a syndicate

and asked to be allowed to take over construction of the railway. Convinced that Stephen's syndicate was up to the task, Tupper convinced the cabinet to back the plan at a meeting in June 1880 and, together with Macdonald, negotiated a contract with the syndicate in October. The syndicate successfully created the Canadian Pacific Railway Company

in February 1881 and assumed construction of the railway shortly thereafter.

In the next years, Tupper would be a vocal supporter of the CPR during its competition with the Grand Trunk Railway

. In December 1883, he worked out a rescue plan for the CPR after it faced financial difficulties and persuaded his party and Parliament to accept the plan.

In addition to his support for completion of the CPR, Tupper also actively managed the existing railways in the colonies. Shortly after becoming minister in 1879, he forced the Intercolonial Railway to lower its freight rates, which had been a major grievance of Maritime business interests. He then forced the Grand Trunk Railway to sell its Rivière-du-Loup

line to the Intercolonial Railway to complete a link between Halifax and the St. Lawrence Seaway. Furthermore, he refused to give the CPR running rights over the Intercolonial Railway, though he did convince the CPR to build the Short Line from Halifax to Saint John.

In terms of canals, Tupper's time as Minister of Railways and Canals is notable for large expenditures on widening the Welland Canal

and deepening the Saint Lawrence Seaway

.

in London. Macdonald initially refused, and Alexander Tilloch Galt

retained the High Commissioner's post.

During the 1882 election

, Tupper campaigned only in Nova Scotia (he normally campaigned throughout the country): he was again successful, with the Conservatives winning 14 of Nova Scotia's 21 seats in the 5th Canadian Parliament

. The 1882 election was personally significant for Tupper because it saw his son, Charles Hibbert Tupper

, elected as MP for Pictou

.

Tupper remained committed to leaving Ottawa, however, and in May 1883, he moved to London to become unpaid High Commissioner, though he did not surrender his ministerial position at the time. Soon, however, he was facing criticism that the two posts were incompatible, and in May 1884, he resigned from cabinet and the House of Commons and became full-time paid High Commissioner.

Tupper remained committed to leaving Ottawa, however, and in May 1883, he moved to London to become unpaid High Commissioner, though he did not surrender his ministerial position at the time. Soon, however, he was facing criticism that the two posts were incompatible, and in May 1884, he resigned from cabinet and the House of Commons and became full-time paid High Commissioner.

During his time as High Commissioner, Tupper sought to vigorously defend Canada's rights. Thus, although he was not a full plenipotentiary

, he represented Canada at a Paris

conference in 1883, where he openly disagreed with the British delegation; and in 1884 was allowed to conduct negotiations for a Canadian commercial treaty with Spain

.

Tupper was concerned with promoting immigration to Canada

and made several tours of various countries in Europe

to encourage immigrants to move to Canada. A report in 1883 acknowledges the work of Sir Charles Tupper:

In 1883, Tupper convinced William Ewart Gladstone

's government to exempt Canadian cattle

from the general British ban on importing American cattle by demonstrating that Canadian cattle was free of disease.

His other duties as High Commissioner included: putting Canadian exporters in contact with British importers; negotiating loans for the Canadian government and the CPR; helping to organize the Colonial and Indian Exhibition

of 1886; arranging for a subsidy for the mail ship from Vancouver, British Columbia to the Orient

; and lobbying on behalf of a British-Pacific cable along the lines of the transatlantic telegraph cable

and for a faster transatlantic steam ship.

Tupper was also present at the founding meeting of the Imperial Federation League

in July 1884, where he argued against a resolution which said that the only options open to the British Empire were Imperial Federation

or disintegration. Tupper believed that a form of limited federation was possible and desirable.

as Premier of Nova Scotia after Fielding campaigned on a platform of leading Nova Scotia out of Confederation. As such, throughout 1886, Macdonald begged Tupper to return to Canada to fight the Anti-Confederates. In January 1887, Tupper returned to Canada to rejoin the 3rd Canadian Ministry as Minister of Finance of Canada

, all the while retaining his post as High Commissioner.

During the 1887 federal election

, Tupper again presented the pro-Confederation argument to the people of Nova Scotia, and again the Conservatives won 14 of Nova Scotia's 21 seats in the 6th Canadian Parliament

.

During his year as finance minister, Tupper retained the government's commitment to protectionism, even extending it to the iron and steel industry. By this point, Tupper was convinced that Canada was ready to move on to its second stage of industrial development

. In part, he held out the prospect of the development of a great iron industry as an inducement to keep Nova Scotia from seceding.

Tupper's unique position of being both Minister of Finance and High Commissioner to London served him well in an emerging crisis in American-Canadian relations: in 1885, the U.S. abrogated the fisheries clause of the Treaty of Washington (1871), and the Canadian government retaliated against American fishermen with a narrow reading of the Treaty of 1818

. Acting as High Commissioner, Tupper pressured the British government (then led by Lord Salisbury

) to stand firm in defending Canada's rights. The result was the appointment of a Joint Commission in 1887, with Tupper serving as one of the three British commissioners to negotiate with the Americans. Salisbury selected Joseph Chamberlain

as one of the British commissioners. John Thompson served as the British delegation's legal counsel. During the negotiations, U.S. Secretary of State Thomas F. Bayard

complained that "Mr. Chamberlain has yielded the control of the negotiations over to Sir Charles Tupper, who subjects the questions to the demands of Canadian politics." The result of the negotiations was a treaty (the Treaty of Washington of 1888) that made such concessions to Canada that it was ultimately rejected by the American Senate in February 1888. However, although the treaty was rejected, the Commission had managed to temporarily resolve the dispute.

Following the conclusion of these negotiations, Tupper decided to return to London to become High-Commissioner full-time. Macdonald attempted to persuade Tupper to stay in Ottawa: during the political crisis surrounding the 1885 North-West Rebellion

, Macdonald had pledged to nominate Sir Hector-Louis Langevin as his successor; Macdonald now told Tupper that he would break this promise and nominate Tupper as his successor. Tupper was not convinced, however, and resigned as Minister of Finance on May 23, 1888, and moved back to London.

For Tupper's work on the Joint Commission, Joseph Chamberlain arranged for Tupper to become a baronet of the United Kingdom, and the Tupper Baronetcy was created on September 13, 1888.

For Tupper's work on the Joint Commission, Joseph Chamberlain arranged for Tupper to become a baronet of the United Kingdom, and the Tupper Baronetcy was created on September 13, 1888.

In 1889, tensions were high between the U.S. and Canada when the U.S. banned Canadians from engaging in the seal hunt in the Bering Sea

as part of the ongoing Bering Sea Dispute between the U.S. and Britain. Tupper traveled to Washington, D.C.

to represent Canadian interests during the negotiations and was something of an embarrassment to the British diplomats.

When, in 1890, the provincial secretary of Newfoundland, Robert Bond

, negotiated a fisheries treaty with the U.S. that Tupper felt was not in Canada's interest, Tupper successfully persuaded the British government (then under Lord Salisbury's second term) to reject the treaty.

As noted above, Tupper remained an active politician during his time as High Commissioner, which was controversial because diplomats are traditionally expected to be nonpartisan. (Tupper's successor as High Commissioner, Donald Smith

would succeed in turning the High Commissioner's office into a nonpartisan office.) As such, Tupper returned to Canada to campaign on behalf of the Conservatives' National Policy during the 1891 election

.

Tupper continued to be active in the Imperial Federation League, though after 1887, the League was split over the issue of regular colonial contribution to imperial defense. As a result, the League was ultimately dissolved in 1893, for which some people blamed Tupper.

Tupper continued to be active in the Imperial Federation League, though after 1887, the League was split over the issue of regular colonial contribution to imperial defense. As a result, the League was ultimately dissolved in 1893, for which some people blamed Tupper.

With respect to the British Empire, Tupper advocated a system of mutual preferential trading. In a series of articles in Nineteenth Century

in 1891 and 1892, Tupper denounced the position that Canada should unilaterally reduce its tariff on British goods. Rather, he argued that any such tariff reduction should only come as part of a wider trade agreement in which tariffs on Canadian goods would also be reduced at the same time.

Sir John A. Macdonald's death in 1891 opened the possibility of Tupper replacing him as prime minister of Canada

, but Tupper enjoyed life in London and decided against returning to Canada. He recommended that his son support Sir John Thompson's prime ministerial bid.

, Lord Aberdeen

, to invite Tupper to return to Canada to become prime minister. However, Lord Aberdeen disliked Tupper and instead invited Sir Mackenzie Bowell to replace Thompson as prime minister.

The greatest challenge facing Bowell as prime minister was the Manitoba Schools Question

The greatest challenge facing Bowell as prime minister was the Manitoba Schools Question

. The Conservative Party was bitterly divided as to how to handle the Manitoba Schools Question, and as a result, on January 4, 1896, seven cabinet ministers resigned, demanding the return of Tupper. As a result, Bowell and Aberdeen were forced to invite Tupper to join the 6th Canadian Ministry

and on January 15 Tupper became Secretary of State for Canada

, with the understanding that he would become prime minister following the dissolution of the 7th Canadian Parliament

.

Returning to Canada, Tupper was elected to the 7th Canadian Parliament as member for Cape Breton

during a by-election

held on February 4, 1896. At this point, Tupper was the de facto prime minister, though legally Bowell was still prime minister.

Tupper's position on the Manitoba Schools Act was that French Catholics in Manitoba had been promised the right to separate state-funded French-language Catholic schools in the Manitoba Act

of 1870. Thus, even though he personally opposed French-language Catholic schools in Manitoba, he believed that the government should stand by its promise and therefore oppose Dalton McCarthy

's Manitoba Schools Act. He maintained this position even after the Manitoba Schools Act was upheld by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council

.

In 1895, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council had also ruled that the Canadian federal government could pass remedial legislation to overrule the Manitoba Schools Act (see Disallowance and reservation

). Thus, in February 1896, Tupper introduced this remedial legislation in the House of Commons. The bill was filibustered by a combination of extreme Protestants led by McCarthy and Liberals led by Wilfrid Laurier

. This filibuster resulted in Tupper abandoning the bill and asking for a dissolution.

Parliament was dissolved on April 24, 1896, and the 7th Canadian Ministry

Parliament was dissolved on April 24, 1896, and the 7th Canadian Ministry

with Tupper as prime minister was sworn in on May 1 making him, with John Turner

and Kim Campbell

, the only Prime Ministers to never sit in Parliament as Prime Minister. Tupper remains the oldest person ever to become Canadian prime minister, at 74.

Throughout the 1896 election

campaign, Tupper argued that the real issue of the election was the future of Canadian industry, and insisted that Conservatives needed to unite to defeat the Patrons of Industry

. However, the Conservatives were so bitterly divided over the Manitoba Schools Question that wherever he spoke, he was faced with a barrage of criticism, most notably at a two-hour address he gave at Massey Hall

in Toronto

, which was constantly interrupted by the crowd.

Wilfrid Laurier, on the other hand, modified the traditional Liberal stance on free trade and embraced aspects of the National Policy.

In the end, the Conservatives won the most votes in the 1896 election (48.2% of the votes, in comparison to 41.4% for the Liberals). However, they captured only about half of the seats in English Canada

, while Laurier's Liberals won a landslide victory in Quebec

, where Tupper's reputation as an ardent imperialist was a major handicap. Tupper's inability to persuade Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau

to return to active politics as his Quebec lieutenant

was the nail in the coffin for the Conservatives' campaign in Quebec.

Although Laurier had clearly won the election on June 24, Tupper initially refused to cede power, insisting that Laurier would be unable to form a government. However, when Tupper attempted to make appointments as prime minister, Lord Aberdeen stepped in, dismissing Tupper and inviting Laurier to form a government. Tupper maintained that Lord Aberdeen's actions were unconstitutional.

Tupper's 68 days is the shortest term of all prime ministers. His government never faced a Parliament.

As Leader of the Opposition during the 8th Canadian Parliament

As Leader of the Opposition during the 8th Canadian Parliament

, Tupper attempted to regain the loyalty of those Conservatives who had deserted the party over the Manitoba Schools Question

. He played up loyalty to the British Empire. Tupper strongly supported Canadian participation in the Second Boer War

, which broke out in 1899, and criticized Laurier for not doing enough to support Britain in the war.

The 1900 election

saw the Conservatives pick up 17 Ontario seats in the 9th Canadian Parliament

. This was a small consolation, however, as Laurier and the Liberals won a definitive majority and had a clear mandate for a second term. What was worse for Tupper, for the first time ever, was the fact he had failed to carry his own seat, losing the Cape Breton seat to Liberal Alexander Johnston

. In November 1900, two weeks after the election, Tupper stepped down as leader of the Conservative Party of Canada and Leader of the Opposition - the caucus chose as his successor fellow Nova Scotian Robert Laird Borden.

in southeast London. He continued to make frequent trips to Canada to visit his sons Charles Hibbert Tupper

and William Johnston Tupper

, both of whom were Canadian politicians.

On November 9, 1907, Tupper became a member of the British Privy Council. He was also promoted to the rank of Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George, which made him entitled to use the postnominal letters "GCMG".

On November 9, 1907, Tupper became a member of the British Privy Council. He was also promoted to the rank of Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George, which made him entitled to use the postnominal letters "GCMG".

Tupper remained interested in imperial politics, and particularly with promoting Canada's place within the British Empire. He sat on the executive committee of the British Empire League

and advocated closer economic ties between Canada and Britain, while continuing to oppose Imperial Federation and requests for Canada to make a direct contribution to imperial defense costs (though he supported Borden's decision to voluntarily make an emergency contribution of dreadnoughts to the Royal Navy

in 1912).

In his retirement, Tupper wrote his memoirs, entitled Recollections of Sixty Years in Canada, which were published in 1914. He also gave a series of interviews to journalist W. A. Harkin which formed the basis of a second book published in 1914, entitled Political Reminiscences of the Right Honourable Sir Charles Tupper.

Tupper's wife, Lady Tupper

died in May 1912. His eldest son Orin died in April 1915 .

On October 30, 1915, in Bexleyheath, Tupper died of heart failure. He was the last of the original Fathers of Confederation

to die, and had lived the longest life of any Canadian prime minister, at 94 years, four months.

His body was returned to Canada on board the HMS Blenheim

(the same vessel that had carried the body of Tupper's colleague, Sir John Thompson to Halifax when Thompson died in England in 1894) and he was buried in St. John's Cemetery, Halifax

in Halifax following a state funeral

with a mile-long procession.

from 1864 to 1867, he led Nova Scotia

into Confederation

and persuaded Joseph Howe

to join the new federal government, bringing an end to the anti-Confederation movement in Nova Scotia.

In their 1999 study of the Canadian Prime Ministers through Jean Chrétien

, J.L. Granatstein and Norman Hillmer

included the results of a survey of Canadian historians ranking the Prime Ministers. Tupper ranked #16 out of the 20 up to that time, due to his extremely short tenure in which he was unable to accomplish anything of significance. Historians noted that despite Tupper's elderly age, he showed a determination and spirit during his brief time as Prime Minister that almost beat Laurier in the 1896 election

Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is an order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George, Prince Regent, later George IV of the United Kingdom, while he was acting as Prince Regent for his father, George III....

, CB

Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate mediæval ceremony for creating a knight, which involved bathing as one of its elements. The knights so created were known as Knights of the Bath...

, PC

Queen's Privy Council for Canada

The Queen's Privy Council for Canada ), sometimes called Her Majesty's Privy Council for Canada or simply the Privy Council, is the full group of personal consultants to the monarch of Canada on state and constitutional affairs, though responsible government requires the sovereign or her viceroy,...

(July 2, 1821 – October 30, 1915) was a Canadian father of Confederation: as the Premier of Nova Scotia

Premier of Nova Scotia

The Premier of Nova Scotia is the first minister for the Canadian province of Nova Scotia who presides over the Executive Council of Nova Scotia. Following the Westminster system, the premier is normally the leader of the political party which has the most seats in the Nova Scotia House of Assembly...

from 1864 to 1867, he led Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is one of Canada's three Maritime provinces and is the most populous province in Atlantic Canada. The name of the province is Latin for "New Scotland," but "Nova Scotia" is the recognized, English-language name of the province. The provincial capital is Halifax. Nova Scotia is the...

into Confederation

Canadian Confederation

Canadian Confederation was the process by which the federal Dominion of Canada was formed on July 1, 1867. On that day, three British colonies were formed into four Canadian provinces...

. He later went on to serve as the sixth Prime Minister of Canada

Prime Minister of Canada

The Prime Minister of Canada is the primary minister of the Crown, chairman of the Cabinet, and thus head of government for Canada, charged with advising the Canadian monarch or viceroy on the exercise of the executive powers vested in them by the constitution...

, sworn in to office on May 1, 1896, seven days after parliament had been dissolved. He would go on to lose the June 23 election, resigning on July 8, 1896. His 69-day term as prime minister is currently the shortest in Canadian history. At age 74, in May 1896, he was also the oldest person to serve as Prime Minister of Canada.

Born in Amherst, Nova Scotia

Amherst, Nova Scotia

Amherst is a Canadian town in northwestern Cumberland County, Nova Scotia.Located at the northeast end of the Cumberland Basin, an arm of the Bay of Fundy, Amherst is strategically situated on the eastern boundary of the Tantramar Marshes 3 kilometres east of the interprovincial border with New...

in 1821, Tupper was trained as a physician

Physician

A physician is a health care provider who practices the profession of medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring human health through the study, diagnosis, and treatment of disease, injury and other physical and mental impairments...

and practiced medicine periodically throughout his political career (and served as the first president of the Canadian Medical Association

Canadian Medical Association

The Canadian Medical Association , with more than 70,000 members, is the largest association of doctors in Canada and works to represent their interests nationally. It formed in 1867, three months after Confederation...

). He entered Nova Scotian politics in 1855 as a protege of James William Johnston

James William Johnston

James W. Johnston was a Nova Scotia lawyer and politician. He served as Premier of the colony from 1857 to 1860 and again from 1864. He was also Government Leader prior to the granting of responsible government in 1848. He was a Conservative and supporter of Confederation...

. During Johnston's tenure as premier of Nova Scotia in 1857–59 and 1863–64, Tupper served as provincial secretary

Provincial Secretary

The Provincial Secretary was a senior position in the executive councils of British North America's colonial governments, and was retained by the Canadian provincial governments for at least a century after Canadian Confederation was proclaimed in 1867...

. Tupper replaced Johnston as premier in 1864. As premier, Tupper established public education

Public education

State schools, also known in the United States and Canada as public schools,In much of the Commonwealth, including Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and the United Kingdom, the terms 'public education', 'public school' and 'independent school' are used for private schools, that is, schools...

in Nova Scotia. He also worked to expand Nova Scotia's railway network in order to promote industry.

By 1860, Tupper supported a union of all the colonies of British North America

British North America

British North America is a historical term. It consisted of the colonies and territories of the British Empire in continental North America after the end of the American Revolutionary War and the recognition of American independence in 1783.At the start of the Revolutionary War in 1775 the British...

. Believing that immediate union of all the colonies was impossible, in 1864, he proposed a Maritime Union

Maritime Union

Maritime Union is a proposed political union of the three Maritime provinces of Canada to form a single new province which would be the fifth-largest in Canada by population...

. However, representatives of the Province of Canada

Province of Canada

The Province of Canada, United Province of Canada, or the United Canadas was a British colony in North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham in the Report on the Affairs of British North America following the Rebellions of...

asked to be allowed to attend the meeting in Charlottetown

Charlottetown

Charlottetown is a Canadian city. It is both the largest city on and the provincial capital of Prince Edward Island, and the county seat of Queens County. Named after Queen Charlotte, the wife of George III, Charlottetown was first incorporated as a town in 1855 and designated as a city in 1885...

scheduled to discuss Maritime Union in order to present a proposal for a wider union, and the Charlottetown Conference

Charlottetown Conference

The Charlottetown Conference was held in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island for representatives from the colonies of British North America to discuss Canadian Confederation...

thus became the first of the three conferences that secured Canadian Confederation

Canadian Confederation

Canadian Confederation was the process by which the federal Dominion of Canada was formed on July 1, 1867. On that day, three British colonies were formed into four Canadian provinces...

. Tupper also represented Nova Scotia at the other two conferences, the Quebec Conference

Quebec Conference, 1864

The Quebec Conference was the second meeting held in 1864 to discuss Canadian Confederation.The 16 delegates from the Province of Canada, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island had agreed at the close of the Charlottetown Conference to meet again at Quebec City October 1864...

(1864) and the London Conference of 1866

London Conference of 1866

The London Conference was held in the United Kingdom and began on 4 December 1866, and it was the final in a series of conferences or debates that led to Canadian confederation in 1867. Sixteen delegates from the Province of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick gathered with officials of the...

. In Nova Scotia, Tupper organized a Confederation Party

Confederation Party

Confederation Party was a term for the parties supporting Canadian confederation in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland in the 1860s when politics became polarised between supporters and opponents of Confederation. The Confederation parties were accordingly opposed by Anti-Confederation...

to combat the activities of the Anti-Confederation Party

Anti-Confederation Party

Anti-Confederation was the name used in what is now Atlantic Canada by several parties opposed to Canadian confederation.-Nova Scotia:In Nova Scotia, the "Anti-Confederates" were led by Joseph Howe. They attempted to reverse the colony's decision to join Confederation, which was initially highly...

organized by Joseph Howe

Joseph Howe

Joseph Howe, PC was a Nova Scotian journalist, politician, and public servant. He is one of Nova Scotia's greatest and best-loved politicians...

and successfully led Nova Scotia into Confederation.

Following the passage of the British North America Act in 1867, Tupper resigned as premier of Nova Scotia and began a career in federal politics. He held multiple cabinet

Cabinet of Canada

The Cabinet of Canada is a body of ministers of the Crown that, along with the Canadian monarch, and within the tenets of the Westminster system, forms the government of Canada...

positions under Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald

John A. Macdonald

Sir John Alexander Macdonald, GCB, KCMG, PC, PC , QC was the first Prime Minister of Canada. The dominant figure of Canadian Confederation, his political career spanned almost half a century...

, including President of the Queen's Privy Council for Canada

President of the Queen's Privy Council for Canada

In the Canadian cabinet, the President of The Queen's Privy Council for Canada is nominally in charge of the Privy Council Office. The President of the Privy Council also has the largely ceremonial duty of presiding over meetings of the Queen's Privy Council for Canada, a body which only convenes...

(1870–72), Minister of Inland Revenue

Minister of Inland Revenue (Canada)

The Minister of Inland Revenue was a portfolio in the Canadian Cabinet from 1867 until 1918 when it became the Minister of Customs and Inland Revenue. In 1927, the portfolio became the Minister of National Revenue.-Ministers and Controllers of Customs:...

(1872–73), Minister of Customs

Minister of Customs

The office of Minister of Customs was a position in the Cabinet of the Government of Canada responsible for the administration of customs revenue collection. This position was originally created by Statute 31 Vict., c...

(1873–74), Minister of Public Works

Minister of Public Works (Canada)

The position of Minister of Public Works existed as part of the Cabinet of Canada from Confederation to 1995.As part of substantial governmental reorganization, the position was merged with that of the Minister of Supply and Services to create the position of Minister of Public Works and Government...

(1878–79), and Minister of Railways and Canals

Minister of Railways and Canals (Canada)

The portfolio of Minister of Railways and Canals was created by Statute 42 Victoria, c. 7, assented to May 15, 1879 and proclaimed in force May 20, 1879. The Minister was the member of the Canadian Cabinet responsible for the administration of the Department of Railways and Canals...

(1879–84). Initially groomed as Macdonald's successor, Tupper had a falling out with Macdonald, and by the early 1880s, he asked Macdonald to appoint him as Canadian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom. Tupper took up his post in London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

in 1883, and would remain High Commissioner until 1895, although in 1887–88, he served as Minister of Finance

Minister of Finance (Canada)

The Minister of Finance is the Minister of the Crown in the Canadian Cabinet who is responsible each year for presenting the federal government's budget...

without relinquishing the High Commissionership.

In 1895, the government of Sir Mackenzie Bowell

Mackenzie Bowell

Sir Mackenzie Bowell, PC, KCMG was a Canadian politician who served as the fifth Prime Minister of Canada from December 21, 1894 to April 27, 1896.-Early life:Bowell was born in Rickinghall, Suffolk, England to John Bowell and Elizabeth Marshall...

floundered over the Manitoba Schools Question

Manitoba Schools Question

The Manitoba Schools Question was a political crisis in the Canadian Province of Manitoba that occurred late in the 19th century, involving publicly funded separate schools for Roman Catholics and Protestants...

; as a result, several leading members of the Conservative Party of Canada

Conservative Party of Canada (historical)

The Conservative Party of Canada has gone by a variety of names over the years since Canadian Confederation. Initially known as the "Liberal-Conservative Party", it dropped "Liberal" from its name in 1873, although many of its candidates continued to use this name.As a result of World War I and the...

demanded the return of Tupper to serve as prime minister. Tupper accepted this invitation and returned to Canada, becoming prime minister in May 1896. An election was called

Canadian federal election, 1896

The Canadian federal election of 1896 was held on June 23, 1896 to elect members of the Canadian House of Commons of the 8th Parliament of Canada. Though the Conservative Party won a plurality of the popular vote, the Liberal Party, led by Wilfrid Laurier, won the majority of seats to form the...

, just before he was sworn in as prime minister, which his party subsequently lost to Wilfrid Laurier

Wilfrid Laurier

Sir Wilfrid Laurier, GCMG, PC, KC, baptized Henri-Charles-Wilfrid Laurier was the seventh Prime Minister of Canada from 11 July 1896 to 6 October 1911....

and the Liberals

Liberal Party of Canada

The Liberal Party of Canada , colloquially known as the Grits, is the oldest federally registered party in Canada. In the conventional political spectrum, the party sits between the centre and the centre-left. Historically the Liberal Party has positioned itself to the left of the Conservative...

. Tupper served as Leader of the Opposition from July 1896 until 1900, at which point he returned to London, where he lived until his death in 1915.

Early life, 1821–1855

Tupper was born in Amherst, Nova ScotiaAmherst, Nova Scotia

Amherst is a Canadian town in northwestern Cumberland County, Nova Scotia.Located at the northeast end of the Cumberland Basin, an arm of the Bay of Fundy, Amherst is strategically situated on the eastern boundary of the Tantramar Marshes 3 kilometres east of the interprovincial border with New...

to Charles Tupper, Sr. and Miriam Lowe Lockhart Buckner. His father was the co-pastor

Pastor

The word pastor usually refers to an ordained leader of a Christian congregation. When used as an ecclesiastical styling or title, this role may be abbreviated to "Pr." or often "Ps"....

of the local Baptist church. Beginning in 1837, at age 16, Tupper attended the Horton Academy in Wolfville, Nova Scotia

Wolfville, Nova Scotia

Wolfville is a small town in the Annapolis Valley, Kings County, Nova Scotia, Canada, located about northwest of the provincial capital, Halifax. As of 2006, the population was 3,772....

, where he learned Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

, Greek

Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek is the stage of the Greek language in the periods spanning the times c. 9th–6th centuries BC, , c. 5th–4th centuries BC , and the c. 3rd century BC – 6th century AD of ancient Greece and the ancient world; being predated in the 2nd millennium BC by Mycenaean Greek...

, and some French

French language

French is a Romance language spoken as a first language in France, the Romandy region in Switzerland, Wallonia and Brussels in Belgium, Monaco, the regions of Quebec and Acadia in Canada, and by various communities elsewhere. Second-language speakers of French are distributed throughout many parts...

. After graduating in 1839, he spent some time in New Brunswick

New Brunswick

New Brunswick is one of Canada's three Maritime provinces and is the only province in the federation that is constitutionally bilingual . The provincial capital is Fredericton and Saint John is the most populous city. Greater Moncton is the largest Census Metropolitan Area...

working as a teacher, before moving to Windsor, Nova Scotia

Windsor, Nova Scotia

Windsor is a town located in Hants County, Mainland Nova Scotia at the junction of the Avon and St. Croix Rivers. It is the largest community in western Hants County with a 2001 population of 3,779 and was at one time the shire town of the county. The region encompassing present day Windsor was...

to spend 1839–40 studying medicine

Medicine

Medicine is the science and art of healing. It encompasses a variety of health care practices evolved to maintain and restore health by the prevention and treatment of illness....

with Dr. Ebenezer Fitch Harding. Borrowing money, he then moved to Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

to study at the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh

Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh

The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh is an organisation dedicated to the pursuit of excellence and advancement in surgical practice, through its interest in education, training and examinations, its liaison with external medical bodies and representation of the modern surgical workforce...

at the University of Edinburgh

University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh, founded in 1583, is a public research university located in Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland, and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The university is deeply embedded in the fabric of the city, with many of the buildings in the historic Old Town belonging to the university...

: he received his MD

Doctor of Medicine

Doctor of Medicine is a doctoral degree for physicians. The degree is granted by medical schools...

in 1843. During his time in Edinburgh

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland, the second largest city in Scotland, and the eighth most populous in the United Kingdom. The City of Edinburgh Council governs one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas. The council area includes urban Edinburgh and a rural area...

, Tupper's commitment to his Baptist faith faltered, and he drank Scotch whisky

Scotch whisky

Scotch whisky is whisky made in Scotland.Scotch whisky is divided into five distinct categories: Single Malt Scotch Whisky, Single Grain Scotch Whisky, Blended Malt Scotch Whisky , Blended Grain Scotch Whisky, and Blended Scotch Whisky.All Scotch whisky must be aged in oak barrels for at least three...

for the first time.

Returning to Nova Scotia, in 1846, he broke off an engagement that he had contracted with the daughter of a wealthy Halifax merchant when he was 17 years old and instead married Frances Morse

Frances Tupper

Frances Amélia, Lady Tupper was the wife of Sir Charles Tupper, the sixth Prime Minister of Canada. They had six children together, three boys and three girls. Two of their sons, Charles Hibbert Tupper and William Johnston Tupper, also had careers in politics...

(1826–1912), the granddaughter of Col. Joseph Morse, one of the founders of Amherst, Nova Scotia

Amherst, Nova Scotia

Amherst is a Canadian town in northwestern Cumberland County, Nova Scotia.Located at the northeast end of the Cumberland Basin, an arm of the Bay of Fundy, Amherst is strategically situated on the eastern boundary of the Tantramar Marshes 3 kilometres east of the interprovincial border with New...

. The Tuppers had three sons (Orin Stewart, Charles Hibbert

Charles Hibbert Tupper

Sir Charles Hibbert Tupper, KCMG, PC was a Canadian lawyer and politician.-Family, early career:Tupper was the second son of Sir Charles Tupper, a physician, leading Conservative politician, and Canadian diplomat...

, and William Johnston

William Johnston Tupper

William Johnston Tupper, was a politician and office holder in Manitoba, Canada. He served as the province's 12th Lieutenant Governor from 1934 to 1940....

) and three daughters (Emma, Elizabeth Stewart (Lilly), and Sophy Almon). The Tupper children were raised in Frances' Anglican denomination and John and Frances regularly worshipped in an Anglican church, though on the campaign trail, Tupper often found time to visit Baptist meetinghouses.

Tupper set himself up as a physician in Amherst, Nova Scotia and opened a drugstore

Pharmacy

Pharmacy is the health profession that links the health sciences with the chemical sciences and it is charged with ensuring the safe and effective use of pharmaceutical drugs...

.

Early years in Nova Scotia politics, 1855–1864

The leader of the Conservative Party of Nova ScotiaProgressive Conservative Association of Nova Scotia

The Progressive Conservative Association of Nova Scotia, registered under the Nova Scotia Elections Act as the "Progressive Conservative Party of Nova Scotia", is a moderate right-of-centre political party in Nova Scotia, Canada....

, James William Johnston

James William Johnston

James W. Johnston was a Nova Scotia lawyer and politician. He served as Premier of the colony from 1857 to 1860 and again from 1864. He was also Government Leader prior to the granting of responsible government in 1848. He was a Conservative and supporter of Confederation...

, a fellow Baptist and family friend of the Tuppers, encouraged Charles Tupper to enter politics. As such, in 1855, Tupper ran against the prominent Liberal politician Joseph Howe

Joseph Howe

Joseph Howe, PC was a Nova Scotian journalist, politician, and public servant. He is one of Nova Scotia's greatest and best-loved politicians...

for the Cumberland County

Cumberland County, Nova Scotia

Cumberland County is a county in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia.-History:The name Cumberland was applied by Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Monckton to the captured Fort Beauséjour on June 18, 1755 in honour of the third son of King George II, William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, victor at...

seat in the Nova Scotia House of Assembly

Nova Scotia House of Assembly

The Nova Scotia Legislature, consisting of Her Majesty The Queen represented by the Lieutenant Governor and the House of Assembly, is the legislative branch of the provincial government of Nova Scotia, Canada...

. Joseph Howe would be a frequent political opponent of Tupper the years to come.

Although Tupper won his seat, the 1855 election was an overall disaster for the Nova Scotia Conservatives, with the Liberals, led by William Young

William Young (politician)

Sir William Young, KCB was a Nova Scotia politician and jurist.Born in Falkirk, the son of John Young and Agnes Renny, Young was first elected to the Nova Scotia House of Assembly in 1836 as a Reformer and, as a lawyer, defended Reform journalists accused of libel...

, winning a large majority. Young consequently became Premier of Nova Scotia

Premier of Nova Scotia

The Premier of Nova Scotia is the first minister for the Canadian province of Nova Scotia who presides over the Executive Council of Nova Scotia. Following the Westminster system, the premier is normally the leader of the political party which has the most seats in the Nova Scotia House of Assembly...

.

At a caucus

Caucus

A caucus is a meeting of supporters or members of a political party or movement, especially in the United States and Canada. As the use of the term has been expanded the exact definition has come to vary among political cultures.-Origin of the term:...

meeting in January 1856, Tupper recommended a new direction for the Conservative party: they should begin actively courting Nova Scotia's Roman Catholic minority and should eagerly embrace railroad construction. Having just led his party into a disastrous election campaign, Johnston decided to basically cede control of the party to Tupper, though Johnston remained the party's leader. In the course of 1856, Tupper led Conservative attacks on the government, leading to Joseph Howe dubbing Tupper "the wicked wasp of Cumberland." In early 1857, Tupper succeeded in convincing a number of Roman Catholic Liberal members to cross the floor to join the Conservatives, reducing Young's government to the status of a minority government

Minority government

A minority government or a minority cabinet is a cabinet of a parliamentary system formed when a political party or coalition of parties does not have a majority of overall seats in the parliament but is sworn into government to break a Hung Parliament election result. It is also known as a...

. As a result, Young was forced to resign in February 1857, and the Conservatives formed a government with Johnston as premier. Tupper became the provincial secretary

Provincial Secretary

The Provincial Secretary was a senior position in the executive councils of British North America's colonial governments, and was retained by the Canadian provincial governments for at least a century after Canadian Confederation was proclaimed in 1867...

.

In Tupper's first speech to the House of Assembly as provincial secretary, he set forth an ambitious plan of railroad construction. Thus, Tupper had embarked on the major theme of his political life: that Nova Scotians (and later Canadians) should downplay their ethnic and religious differences, and instead focus on developing the land's natural resources

Natural Resources

Natural Resources is a soul album released by Motown girl group Martha Reeves and the Vandellas in 1970 on the Gordy label. The album is significant for the Vietnam War ballad "I Should Be Proud" and the slow jam, "Love Guess Who"...

. He argued that with Nova Scotia's "inexhaustible mines", it could become "a vast manufacturing mart" for the east coast of North America. He quickly persuaded Johnston to end the General Mining Association's monopoly over Nova Scotia minerals.

In June 1857, Tupper initiated discussions with New Brunswick

New Brunswick

New Brunswick is one of Canada's three Maritime provinces and is the only province in the federation that is constitutionally bilingual . The provincial capital is Fredericton and Saint John is the most populous city. Greater Moncton is the largest Census Metropolitan Area...

and the Province of Canada

Province of Canada

The Province of Canada, United Province of Canada, or the United Canadas was a British colony in North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham in the Report on the Affairs of British North America following the Rebellions of...

about an intercolonial railway

Intercolonial Railway of Canada

The Intercolonial Railway of Canada , also referred to as the Intercolonial Railway , was a historic Canadian railway that operated from 1872 to 1918, when it became part of Canadian National Railways...

. He traveled to London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

in 1858 to attempt to secure imperial

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

backing for this project. During these discussions, Tupper found that the Canadians were more interested in discussing federal union, while the British (with the Earl of Derby

Edward Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby

Edward George Geoffrey Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby, KG, PC was an English statesman, three times Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, and to date the longest serving leader of the Conservative Party. He was known before 1834 as Edward Stanley, and from 1834 to 1851 as Lord Stanley...

in his second term as Prime Minister

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and...

) were too absorbed in their own immediate interests. As such, nothing came of the 1858 discussions for an intercolonial railway.

An election was held in May 1859, with sectarian conflict playing a large role, with the Catholics largely supporting the Conservatives and the Protestants now shifting towards the Liberals. Tupper barely managed to retain his seat. The Conservatives were barely re-elected and lost a confidence vote later that year. Johnston asked the Governor of Nova Scotia, Lord Mulgrave

George Phipps, 2nd Marquess of Normanby

George Augustus Constantine Phipps, 2nd Marquess of Normanby, GCB, GCMG, PC , styled Viscount Normanby between 1831 and 1838 and Earl of Mulgrave between 1838 and 1863, was a British Liberal politician and colonial governor.-Background:Normanby was born in London, the son of Constantine Phipps, 1st...

, for a dissolution

Dissolution of parliament

In parliamentary systems, a dissolution of parliament is the dispersal of a legislature at the call of an election.Usually there is a maximum length of a legislature, and a dissolution must happen before the maximum time...

, but Mulgrave refused and invited William Young to form a government. Tupper was outraged and petitioned the British government, asking them to recall Mulgrave.

For the next three years, Tupper was ferocious in his denunciations of the Liberal government, first Young, and then Joseph Howe, who took over from Young later in 1860. This came to a head in 1863 when the Liberals introduced legislation to restrict the Nova Scotia franchise

Suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply the franchise, distinct from mere voting rights, is the civil right to vote gained through the democratic process...

, a move which Johnston and Tupper successfully blocked.

Tupper continued practicing medicine throughout this period. He established a successful medical practice in Halifax, rising to become the city medical officer. In 1863, he was elected president of the Medical Society of Nova Scotia.

In the June 1863 election, the Conservatives campaigned on a platform of railroad construction and expanded access to public education. The Conservatives won a huge majority, with 44 of the House of Assembly's 55 seats. Johnston resumed his duties as premier and Tupper again became provincial secretary. As a further sign of the Conservatives' commitment to non-sectarianism, in 1863, after a 20-year hiatus, Dalhousie College was re-opened as a non-denominational institution of higher learning.

In May 1864, Johnston retired from politics, accepting an appointment as a judge

Judge

A judge is a person who presides over court proceedings, either alone or as part of a panel of judges. The powers, functions, method of appointment, discipline, and training of judges vary widely across different jurisdictions. The judge is supposed to conduct the trial impartially and in an open...

, and Tupper was chosen as his successor as premier of Nova Scotia.

Premier of Nova Scotia, 1864–1867

Theodore Harding Rand

Theodore Harding Rand was a Canadian educator and poet.Rand was born in Cornwallis, Nova Scotia in 1835. A Baptist, Rand attended Acadia College in Wolfville, Nova Scotia, which had been founded by the Baptist community in 1838...

as Nova Scotia's first superintendent of education. This in turn aroused concern among Catholics, led by Archbishop Thomas-Louis Connolly

Thomas-Louis Connolly

Thomas-Louis Connolly was a Canadian Roman Catholic priest, Capuchin, vicar general of the diocese of Halifax, Bishop of Saint John, and Archbishop of Halifax from 1859 to 1876....

, who demanded state-funded Catholic schools. Tupper reached a compromise with Archbishop Connolly whereby Catholic-run schools could receive public funding, so long as they provided their religious instruction after hours.

Making good on his promise for expanded railroad construction, in 1864, Tupper appointed Sandford Fleming

Sandford Fleming

Sir Sandford Fleming, was a Scottish-born Canadian engineer and inventor, proposed worldwide standard time zones, designed Canada's first postage stamp, a huge body of surveying and map making, engineering much of the Intercolonial Railway and the Canadian Pacific Railway, and was a founding...

as the chief engineer of the Nova Scotia Railway

Nova Scotia Railway

The Nova Scotia Railway is a historic Canadian railway. It was composed of two lines, one connecting Richmond with Windsor, the other connecting Richmond with Pictou via Truro....

in order to expand the line from Truro

Truro, Nova Scotia

-Education:Truro has one high school, Cobequid Educational Centre. Post-secondary options include a campus of the Nova Scotia Community College, as well as the Nova Scotia Agricultural College in the neighboring town of Bible Hill.- Sports :...

to Pictou Landing

Pictou Landing, Nova Scotia

Pictou Landing is a community in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, located in Pictou County .-References:*...

. He would later (Jan. 1866) award Fleming the contract to complete the line after local contractors proved too slow. Though this decision was controversial, it did result in the line from being successfully completed by May 1867. A second proposed line, from Annapolis Royal

Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia