Charon's obol

Encyclopedia

Charon (mythology)

In Greek mythology, Charon or Kharon is the ferryman of Hades who carries souls of the newly deceased across the rivers Styx and Acheron that divided the world of the living from the world of the dead. A coin to pay Charon for passage, usually an obolus or danake, was sometimes placed in or on...

's obol is an allusive

Allusion

An allusion is a figure of speech that makes a reference to, or representation of, people, places, events, literary work, myths, or works of art, either directly or by implication. M. H...

term for the coin

Coin

A coin is a piece of hard material that is standardized in weight, is produced in large quantities in order to facilitate trade, and primarily can be used as a legal tender token for commerce in the designated country, region, or territory....

placed in or on the mouth of a dead person before burial. According to Greek

Ancient Greek literature

Ancient Greek literature refers to literature written in the Ancient Greek language until the 4th century.- Classical and Pre-Classical Antiquity :...

and Latin literary sources

Latin literature

Latin literature includes the essays, histories, poems, plays, and other writings of the ancient Romans. In many ways, it seems to be a continuation of Greek literature, using many of the same forms...

, the coin was a payment or bribe for the ferry

Ferry

A ferry is a form of transportation, usually a boat, but sometimes a ship, used to carry primarily passengers, and sometimes vehicles and cargo as well, across a body of water. Most ferries operate on regular, frequent, return services...

man who conveyed souls across the river that divided the world of the living from the world of the dead. Archaeological examples of these coins have been called "the most famous grave goods

Grave goods

Grave goods, in archaeology and anthropology, are the items buried along with the body.They are usually personal possessions, supplies to smooth the deceased's journey into the afterlife or offerings to the gods. Grave goods are a type of votive deposit...

from antiquity

Classical antiquity

Classical antiquity is a broad term for a long period of cultural history centered on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ancient Greece and ancient Rome, collectively known as the Greco-Roman world...

."

The custom is primarily associated with the ancient Greeks and Romans

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome was a thriving civilization that grew on the Italian Peninsula as early as the 8th century BC. Located along the Mediterranean Sea and centered on the city of Rome, it expanded to one of the largest empires in the ancient world....

, but is found also in the Near East

Near East

The Near East is a geographical term that covers different countries for geographers, archeologists, and historians, on the one hand, and for political scientists, economists, and journalists, on the other...

, and later in Western Europe, particularly in the regions inhabited by Celts of the Gallo-Roman

Gallo-Roman culture

The term Gallo-Roman describes the Romanized culture of Gaul under the rule of the Roman Empire. This was characterized by the Gaulish adoption or adaptation of Roman mores and way of life in a uniquely Gaulish context...

, Hispano-Roman

Hispania

Another theory holds that the name derives from Ezpanna, the Basque word for "border" or "edge", thus meaning the farthest area or place. Isidore of Sevilla considered Hispania derived from Hispalis....

and Romano-British

Roman Britain

Roman Britain was the part of the island of Great Britain controlled by the Roman Empire from AD 43 until ca. AD 410.The Romans referred to the imperial province as Britannia, which eventually comprised all of the island of Great Britain south of the fluid frontier with Caledonia...

cultures, and among Germanic peoples

Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples are an Indo-European ethno-linguistic group of Northern European origin, identified by their use of the Indo-European Germanic languages which diversified out of Proto-Germanic during the Pre-Roman Iron Age.Originating about 1800 BCE from the Corded Ware Culture on the North...

of late antiquity

Late Antiquity

Late Antiquity is a periodization used by historians to describe the time of transition from Classical Antiquity to the Middle Ages, in both mainland Europe and the Mediterranean world. Precise boundaries for the period are a matter of debate, but noted historian of the period Peter Brown proposed...

and the early Christian era

History of Christianity

The history of Christianity concerns the Christian religion, its followers and the Church with its various denominations, from the first century to the present. Christianity was founded in the 1st century by the followers of Jesus of Nazareth who they believed to be the Christ or chosen one of God...

, with sporadic examples into the early 20th century.

Although archaeology shows that the myth

Classical mythology

Classical mythology or Greco-Roman mythology is the cultural reception of myths from the ancient Greeks and Romans. Along with philosophy and political thought, mythology represents one of the major survivals of classical antiquity throughout later Western culture.Classical mythology has provided...

reflects an actual custom, the placement of coins with the dead was neither pervasive nor confined to a single coin in the deceased’s mouth. In many burials, inscribed metal-leaf tablets

Totenpass

Totenpass is a German term sometimes used for inscribed tablets or metal leaves found in burials primarily of those presumed to be initiates into Orphic, Dionysiac, and some ancient Egyptian and Semitic religions...

or exonumia

Exonumia

Exonumia are numismatic items other than coins and paper money. This includes "Good For" tokens, badges, counterstamped coins, elongated coins, encased coins, souvenir medallions, tags, wooden nickels and other similar items...

take the place of the coin, or gold-foil crosses in the early Christian era. The presence of coins or a coin-hoard

Hoard

In archaeology, a hoard is a collection of valuable objects or artifacts, sometimes purposely buried in the ground. This would usually be with the intention of later recovery by the hoarder; hoarders sometimes died before retrieving the hoard, and these surviving hoards may be uncovered by...

in Germanic ship-burials

Ship burial

A ship burial or boat grave is a burial in which a ship or boat is used either as a container for the dead and the grave goods, or as a part of the grave goods itself. If the ship is very small, it is called a boat grave...

suggests an analogous

Analogue (literature)

The term analogue is used in literary history in two related senses:* a work which resembles another in terms of one or more motifs, characters, scenes, phrases or events....

concept.

The phrase "Charon’s obol" as used by archaeologists sometimes can be understood as referring to a particular religious rite, but often serves as a kind of shorthand for coinage as grave goods presumed to further the deceased’s passage into the afterlife. In Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

, Charon's obol sometimes is called a viaticum

Viaticum

Viaticum is a term used especially in the Roman Catholic Church for the Eucharist administered, with or without anointing of the sick, to a person who is dying, and is thus a part of the last rites...

, or "sustenance for the journey"; the placement of the coin on the mouth has been explained also as a seal to protect the deceased's soul or to prevent it from returning.

Terminology

Obolus

The obol was an ancient silver coin. In Classical Athens, there were six obols to the drachma, lioterally "handful"; it could be excahnged for eight chalkoi...

(Greek

Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek is the stage of the Greek language in the periods spanning the times c. 9th–6th centuries BC, , c. 5th–4th centuries BC , and the c. 3rd century BC – 6th century AD of ancient Greece and the ancient world; being predated in the 2nd millennium BC by Mycenaean Greek...

obolos, ὀβολός), one of the basic denominations

Denomination (currency)

Denomination is a proper description of a currency amount, usually for coins or banknotes. Denominations may also be used with other means of payment like gift cards. See also Redenomination.-Subunit and super unit:...

of ancient Greek coinage

Ancient Greek coinage

The history of Ancient Greek coinage can be divided into three periods, the Archaic, the Classical, and the Hellenistic. The Archaic period extends from the introduction of coinage to the Greek world in about 600 BCE until the Persian Wars in about 480 BCE...

, worth one-sixth of a drachma. Among the Greeks, coins in actual burials are sometimes also a danakē

Danake

The danake or danace was a small silver coin of the Persian Empire , equivalent to the Greek obol and circulated among the eastern Greeks. Later it was used by the Greeks in other metals...

(δανάκη) or other relatively small-denomination gold

Gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au and an atomic number of 79. Gold is a dense, soft, shiny, malleable and ductile metal. Pure gold has a bright yellow color and luster traditionally considered attractive, which it maintains without oxidizing in air or water. Chemically, gold is a...

, silver

Silver

Silver is a metallic chemical element with the chemical symbol Ag and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it has the highest electrical conductivity of any element and the highest thermal conductivity of any metal...

, bronze

Bronze

Bronze is a metal alloy consisting primarily of copper, usually with tin as the main additive. It is hard and brittle, and it was particularly significant in antiquity, so much so that the Bronze Age was named after the metal...

or copper

Copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu and atomic number 29. It is a ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. Pure copper is soft and malleable; an exposed surface has a reddish-orange tarnish...

coin in local use. In Roman literary sources the coin is usually bronze or copper. From the 6th to the 4th centuries BC in the Black Sea

Black Sea

The Black Sea is bounded by Europe, Anatolia and the Caucasus and is ultimately connected to the Atlantic Ocean via the Mediterranean and the Aegean seas and various straits. The Bosphorus strait connects it to the Sea of Marmara, and the strait of the Dardanelles connects that sea to the Aegean...

region, low-value coins depicting arrowhead

Arrowhead

An arrowhead is a tip, usually sharpened, added to an arrow to make it more deadly or to fulfill some special purpose. Historically arrowheads were made of stone and of organic materials; as human civilization progressed other materials were used...

s or dolphin

Dolphin

Dolphins are marine mammals that are closely related to whales and porpoises. There are almost forty species of dolphin in 17 genera. They vary in size from and , up to and . They are found worldwide, mostly in the shallower seas of the continental shelves, and are carnivores, mostly eating...

s were in use, mainly for the purpose of "local exchange and to serve as ‘Charon’s obol.’” The payment is sometimes specified with a term for “boat fare” (in Greek naulon, ναῦλον, Latin naulum); “fee for ferrying” (porthmeion, πορθμήϊον or πορθμεῖον); or “waterway toll” (Latin portorium).

The word naulon (ναῦλον) is defined by the Christian-era lexicographer Hesychius of Alexandria

Hesychius of Alexandria

Hesychius of Alexandria , a grammarian who flourished probably in the 5th century CE, compiled the richest lexicon of unusual and obscure Greek words that has survived...

as the coin put into the mouth of the dead; one of the meanings of danakē (δανάκη) is given as “the obol for the dead”. The Suda

Suda

The Suda or Souda is a massive 10th century Byzantine encyclopedia of the ancient Mediterranean world, formerly attributed to an author called Suidas. It is an encyclopedic lexicon, written in Greek, with 30,000 entries, many drawing from ancient sources that have since been lost, and often...

defines danakē as a coin traditionally buried with the dead for paying the ferryman to cross the river Acheron

Acheron

The Acheron is a river located in the Epirus region of northwest Greece. It flows into the Ionian Sea in Ammoudia, near Parga.-In mythology:...

, and explicates the definition of porthmēïon (πορθμήϊον) as a ferryman’s fee with a quotation from the poet Callimachus

Callimachus

Callimachus was a native of the Greek colony of Cyrene, Libya. He was a noted poet, critic and scholar at the Library of Alexandria and enjoyed the patronage of the Egyptian–Greek Pharaohs Ptolemy II Philadelphus and Ptolemy III Euergetes...

, who notes the custom of carrying the porthmēïon in the “parched mouths of the dead.”

Charon's obol as viaticum

In Latin, Charon’s obol is sometimes called a viaticum, which in everyday usage means “provision for a journey” (from via, “way, road, journey”), encompassing food, money and other supplies. The same word can refer to the living allowance granted to those stripped of their property and condemned to exile, and by metaphorMetaphor

A metaphor is a literary figure of speech that uses an image, story or tangible thing to represent a less tangible thing or some intangible quality or idea; e.g., "Her eyes were glistening jewels." Metaphor may also be used for any rhetorical figures of speech that achieve their effects via...

ical extension to preparing for death at the end of life’s journey. Cicero

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero , was a Roman philosopher, statesman, lawyer, political theorist, and Roman constitutionalist. He came from a wealthy municipal family of the equestrian order, and is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.He introduced the Romans to the chief...

, in his philosophical dialogue On Old Age

On Old Age

On Old Age is an essay written by Cicero in 44 BC on the subject of aging and death. It has remained popular because of its profound subject matter as well as its clear and beautiful language. It is a standard text for teaching Latin to students in the second year.The Latin title of the piece is...

(44 BC), has the interlocutor

Interlocutor (linguistics)

An interlocutor is the person to whom speech is directed . In many Romance languages, the subject who is/are talking is/are the locutor. The use of the word 'locutor,' however, is not yet formally correct in the English language...

Cato the Elder

Cato the Elder

Marcus Porcius Cato was a Roman statesman, commonly referred to as Censorius , Sapiens , Priscus , or Major, Cato the Elder, or Cato the Censor, to distinguish him from his great-grandson, Cato the Younger.He came of an ancient Plebeian family who all were noted for some...

combine two metaphors — nearing the end of a journey, and ripening fruit — in speaking of the approach to death:

Drawing on this metaphorical sense of “provision for the journey into death,” ecclesiastical Latin

Ecclesiastical Latin

Ecclesiastical Latin is the Latin used by the Latin Rite of the Catholic Church in all periods for ecclesiastical purposes...

borrowed the term viaticum

Viaticum

Viaticum is a term used especially in the Roman Catholic Church for the Eucharist administered, with or without anointing of the sick, to a person who is dying, and is thus a part of the last rites...

for the form of Eucharist

Eucharist

The Eucharist , also called Holy Communion, the Sacrament of the Altar, the Blessed Sacrament, the Lord's Supper, and other names, is a Christian sacrament or ordinance...

that is placed in the mouth of a person who is dying as provision for the soul’s passage to eternal life. The earliest literary evidence of this Christian usage for viaticum appears in Paulinus

Paulinus of Nola

Saint Paulinus of Nola, also known as Pontificus Meropius Anicius Paulinus was a Roman senator who converted to a severe monasticism in 394...

’s account of the death of St. Ambrose

Ambrose

Aurelius Ambrosius, better known in English as Saint Ambrose , was a bishop of Milan who became one of the most influential ecclesiastical figures of the 4th century. He was one of the four original doctors of the Church.-Political career:Ambrose was born into a Roman Christian family between about...

in 397 AD. The 7th-century Synodus Hibernensis offers an etymological

Etymology

Etymology is the study of the history of words, their origins, and how their form and meaning have changed over time.For languages with a long written history, etymologists make use of texts in these languages and texts about the languages to gather knowledge about how words were used during...

explanation: “This word ‘viaticum’ is the name of communion

Eucharist

The Eucharist , also called Holy Communion, the Sacrament of the Altar, the Blessed Sacrament, the Lord's Supper, and other names, is a Christian sacrament or ordinance...

, that is to say, ‘the guardianship of the way,’ for it guards the soul until it shall stand before the judgment-seat of Christ

Christ

Christ is the English term for the Greek meaning "the anointed one". It is a translation of the Hebrew , usually transliterated into English as Messiah or Mashiach...

.” Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, O.P. , also Thomas of Aquin or Aquino, was an Italian Dominican priest of the Catholic Church, and an immensely influential philosopher and theologian in the tradition of scholasticism, known as Doctor Angelicus, Doctor Communis, or Doctor Universalis...

explained the term as “a prefiguration

Typology (theology)

Typology in Christian theology and Biblical exegesis is a doctrine or theory concerning the relationship between the Old and New Testaments...

of the fruit of God, which will be in the promised land

Promised land

The Promised Land is a term used to describe the land promised or given by God, according to the Hebrew Bible, to the Israelites, the descendants of Jacob. The promise is firstly made to Abraham and then renewed to his son Isaac, and to Isaac's son Jacob , Abraham's grandson...

. And because of this it is called the viaticum, since it provides us with the way of getting there”; the idea of Christians as “travelers in search of salvation

Salvation

Within religion salvation is the phenomenon of being saved from the undesirable condition of bondage or suffering experienced by the psyche or soul that has arisen as a result of unskillful or immoral actions generically referred to as sins. Salvation may also be called "deliverance" or...

” finds early expression in the Confessions

Confessions (St. Augustine)

Confessions is the name of an autobiographical work, consisting of 13 books, by St. Augustine of Hippo, written between AD 397 and AD 398. Modern English translations of it are sometimes published under the title The Confessions of St...

of St. Augustine

Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo , also known as Augustine, St. Augustine, St. Austin, St. Augoustinos, Blessed Augustine, or St. Augustine the Blessed, was Bishop of Hippo Regius . He was a Latin-speaking philosopher and theologian who lived in the Roman Africa Province...

.

An equivalent word in Greek is ephodion (ἐφόδιον); like viaticum, the word is used in antiquity to mean “provision for a journey” (literally, “something for the road,” from the prefix ἐπ-, “on” + ὁδός, “road, way”) and later in Greek patristic

Church Fathers

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were early and influential theologians, eminent Christian teachers and great bishops. Their scholarly works were used as a precedent for centuries to come...

literature for the Eucharist administered on the point of death.

In literature

.jpg)

- it is a single, low-denomination coin;

- it is placed in the mouth;

- the placement occurs at the time of death;

- it represents a boat fare.

Greek epigram

Epigram

An epigram is a brief, interesting, usually memorable and sometimes surprising statement. Derived from the epigramma "inscription" from ἐπιγράφειν epigraphein "to write on inscribe", this literary device has been employed for over two millennia....

s that were literary versions of epitaph

Epitaph

An epitaph is a short text honoring a deceased person, strictly speaking that is inscribed on their tombstone or plaque, but also used figuratively. Some are specified by the dead person beforehand, others chosen by those responsible for the burial...

s refer to “the obol that pays the passage of the departed,” with some epigrams referring to the belief by mocking or debunking it. The satirist Lucian

Lucian

Lucian of Samosata was a rhetorician and satirist who wrote in the Greek language. He is noted for his witty and scoffing nature.His ethnicity is disputed and is attributed as Assyrian according to Frye and Parpola, and Syrian according to Joseph....

has Charon himself, in a dialogue of the same name, declare that he collects “an obol from everyone who makes the downward journey.” In an elegy

Elegy

In literature, an elegy is a mournful, melancholic or plaintive poem, especially a funeral song or a lament for the dead.-History:The Greek term elegeia originally referred to any verse written in elegiac couplets and covering a wide range of subject matter, including epitaphs for tombs...

of consolation spoken in the person of the dead woman, the Augustan

Augustan literature (ancient Rome)

Augustan literature is the period of Latin literature written during the reign of Augustus , the first Roman emperor. In literary histories of the first part of the 20th century and earlier, Augustan literature was regarded along with that of the Late Republic as constituting the Golden Age of...

poet Propertius expresses the finality of death by her payment of the bronze coin to the infernal toll collector (portitor). Several other authors mention the fee. Often, an author uses the low value of the coin to emphasize that death makes no distinction between rich and poor; all must pay the same because all must die, and a rich person can take no greater amount into death:

Admission to an event or establishment

Admission to a journey or other event or establishment may be subject to paying an entrance fee / buying a ticket. A pass may give admittance without a ticket for a given time period, or give the right to obtain free tickets. A discount pass allows buying tickets at a reduced price...

to Hell

Hell

In many religious traditions, a hell is a place of suffering and punishment in the afterlife. Religions with a linear divine history often depict hells as endless. Religions with a cyclic history often depict a hell as an intermediary period between incarnations...

encouraged a comic

Ancient Greek comedy

Ancient Greek comedy was one of the final three principal dramatic forms in the theatre of classical Greece . Athenian comedy is conventionally divided into three periods, Old Comedy, Middle Comedy, and New Comedy...

or satiric treatment, and Charon as a ferryman who must be persuaded, threatened, or bribed to do his job appears to be a literary construct that is not reflected in early classical art. Christiane Sourvinou-Inwood has shown that in 5th-century BC depictions of Charon, as on the funerary vases called lekythoi

Lekythos

A lekythos is a type of Greek pottery used for storing oil , especially olive oil. It has a narrow body and one handle attached to the neck of the vessel. The lekythos was used for anointing dead bodies of unmarried men and many lekythoi are found in tombs. The images on lekythoi were often...

, he is a non-threatening, even reassuring presence who guides women, adolescents, and children to the afterlife. Humor, as in Aristophanes

Aristophanes

Aristophanes , son of Philippus, of the deme Cydathenaus, was a comic playwright of ancient Athens. Eleven of his forty plays survive virtually complete...

’s comic catabasis

Descent to the underworld

The descent to the underworld is a mytheme of comparative mythology found in a diverse number of religions from around the world, including Christianity. The hero or upper-world deity journeys to the underworld or to the land of the dead and returns, often with a quest-object or a loved one, or...

The Frogs

The Frogs

The Frogs is a comedy written by the Ancient Greek playwright Aristophanes. It was performed at the Lenaia, one of the Festivals of Dionysus, in 405 BC, and received first place.-Plot:...

, “makes the journey to Hades less frightening by articulating it explicitly and trivializing it.” Aristophanes makes jokes about the fee, and a character complains that Theseus

Theseus

For other uses, see Theseus Theseus was the mythical founder-king of Athens, son of Aethra, and fathered by Aegeus and Poseidon, both of whom Aethra had slept with in one night. Theseus was a founder-hero, like Perseus, Cadmus, or Heracles, all of whom battled and overcame foes that were...

must have introduced it, characterizing the Athenian hero in his role of city organizer as a bureaucrat

Bureaucrat

A bureaucrat is a member of a bureaucracy and can comprise the administration of any organization of any size, though the term usually connotes someone within an institution of a government or corporation...

.

Lucian satirizes the obol in his essay “On Funerals”:

Archaeological evidence

The use of coins as grave goodsGrave goods

Grave goods, in archaeology and anthropology, are the items buried along with the body.They are usually personal possessions, supplies to smooth the deceased's journey into the afterlife or offerings to the gods. Grave goods are a type of votive deposit...

shows a variety of practice that casts doubt on the accuracy of the term “Charon’s obol” as an interpretational category. The phrase continues to be used, however, to suggest the ritual or religious significance of coinage in a funerary context.

Coins are found in Greek burials by the 5th century BC, as soon as Greece was monetized, and appear throughout the Roman Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

into the 5th century AD, with examples conforming to the Charon’s obol type as far west as the Iberian Peninsula

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula , sometimes called Iberia, is located in the extreme southwest of Europe and includes the modern-day sovereign states of Spain, Portugal and Andorra, as well as the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar...

, north into Britain

Roman Britain

Roman Britain was the part of the island of Great Britain controlled by the Roman Empire from AD 43 until ca. AD 410.The Romans referred to the imperial province as Britannia, which eventually comprised all of the island of Great Britain south of the fluid frontier with Caledonia...

, and east to the Vistula river in Poland

Poland in Antiquity

Peoples belonging to numerous archeological cultures identified with Celtic, Germanic and Baltic tribes, lived and migrated through various parts the territory that now constitutes Poland in Antiquity, an era that dates from about 400 BC to 450–500 AD...

. The jawbones of skulls found in certain burials in Roman Britain

Roman Britain

Roman Britain was the part of the island of Great Britain controlled by the Roman Empire from AD 43 until ca. AD 410.The Romans referred to the imperial province as Britannia, which eventually comprised all of the island of Great Britain south of the fluid frontier with Caledonia...

are stained greenish

Patina

Patina is a tarnish that forms on the surface of bronze and similar metals ; a sheen on wooden furniture produced by age, wear, and polishing; or any such acquired change of a surface through age and exposure...

from contact with a copper

Copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu and atomic number 29. It is a ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. Pure copper is soft and malleable; an exposed surface has a reddish-orange tarnish...

coin; Roman coins are found later in Anglo-Saxon

Anglo-Saxons

Anglo-Saxon is a term used by historians to designate the Germanic tribes who invaded and settled the south and east of Great Britain beginning in the early 5th century AD, and the period from their creation of the English nation to the Norman conquest. The Anglo-Saxon Era denotes the period of...

graves, but often pierced for wearing as a necklace or amulet

Amulet

An amulet, similar to a talisman , is any object intended to bring good luck or protection to its owner.Potential amulets include gems, especially engraved gems, statues, coins, drawings, pendants, rings, plants and animals; even words said in certain occasions—for example: vade retro satana—, to...

. Among the ancient Greeks, only about 5 to 10 percent of known burials contain any coins at all; in some Roman cremation

Cremation

Cremation is the process of reducing bodies to basic chemical compounds such as gasses and bone fragments. This is accomplished through high-temperature burning, vaporization and oxidation....

cemeteries, however, as many as half the graves yield coins. Many if not most of these occurrences conform to the myth of Charon’s obol in neither the number of coins nor their positioning. Variety of placement and number, including but not limited to a single coin in the mouth, is characteristic of all periods and places.

Hellenized world

Ancient history of Cyprus

The ancient history of Cyprus, also known as Classical Antiquity, dates from the 8th century BC to the Middle Ages. The earliest written records relating to Cyprus date to the Middle Bronze Age , see Alasiya.-Assyrian Period:...

. In investigations reported 2001 by A. Destrooper-Georgiades, a specialist in Achaemenid

Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire , sometimes known as First Persian Empire and/or Persian Empire, was founded in the 6th century BCE by Cyrus the Great who overthrew the Median confederation...

numismatics

Numismatics

Numismatics is the study or collection of currency, including coins, tokens, paper money, and related objects. While numismatists are often characterized as students or collectors of coins, the discipline also includes the broader study of money and other payment media used to resolve debts and the...

, 33 tombs had yielded 77 coins. Although denomination varies, as does the number in any given burial, small coins predominate. Coins started to be placed in tombs almost as soon as they came into circulation

Circulation (currency)

The social system in which we live has usually developed to the stage for money to be used as the medium for the exchange of goods and services. Hence the money is an important aspect of the general social or macroeconomics system...

on the island in the 6th century, and some predate both the first issue of the obol and any literary reference to Charon’s fee.

Although only a small percentage of Greek burials contain coins, among these there are widespread examples of a single coin positioned in the mouth of a skull or with cremation remains. In cremation urns, the coin sometimes adheres to the jawbone of the skull. At Olynthus

Olynthus

Olynthus was an ancient city of Chalcidice, built mostly on two flat-topped hills 30–40m in height, in a fertile plain at the head of the Gulf of Torone, near the neck of the peninsula of Pallene, about 2.5 kilometers from the sea, and about 60 stadia Olynthus was an ancient city of...

, 136 coins, mostly bronze but some silver, were found with burials; in 1932, archaeologists reported that 20 graves had each contained four bronze coins, which they believed were intended for placement in the mouth. A few tombs at Olynthus have contained two coins, but more often a single bronze coin was positioned in the mouth or within the head of the skeleton. In Hellenistic-era

Hellenistic civilization

Hellenistic civilization represents the zenith of Greek influence in the ancient world from 323 BCE to about 146 BCE...

tombs at one cemetery in Athens, coins, usually bronze, were found most often in the dead person’s mouth, though sometimes in the hand, loose in the grave, or in a vessel. At Chania, an originally Minoan

Minoan civilization

The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age civilization that arose on the island of Crete and flourished from approximately the 27th century BC to the 15th century BC. It was rediscovered at the beginning of the 20th century through the work of the British archaeologist Arthur Evans...

settlement on Crete, a tomb dating from the second half of the 3rd century BC held a rich variety of grave goods, including fine gold jewelry, a gold tray with the image of a bird, a clay vessel, a bronze mirror

Bronze mirror

Bronze mirrors preceded the glass mirrors of today. This type of mirror has been found by archaeologists among elite assemblages from various cultures, from Etruscan Italy to China.-History:-Egypt:...

, a bronze strigil

Strigil

A strigil was a small, curved, metal tool used in ancient Greece and Rome to scrape dirt and sweat from the body before effective soaps became available. First perfumed oil was applied to the skin, and then it would be scraped off, along with the dirt. For wealthier people, this process was often...

, and a bronze “Charon coin” depicting Zeus

Zeus

In the ancient Greek religion, Zeus was the "Father of Gods and men" who ruled the Olympians of Mount Olympus as a father ruled the family. He was the god of sky and thunder in Greek mythology. His Roman counterpart is Jupiter and his Etruscan counterpart is Tinia.Zeus was the child of Cronus...

. In excavations of 91 tombs at a cemetery in Amphipolis

Amphipolis

Amphipolis was an ancient Greek city in the region once inhabited by the Edoni people in the present-day region of Central Macedonia. It was built on a raised plateau overlooking the east bank of the river Strymon where it emerged from Lake Cercinitis, about 3 m. from the Aegean Sea. Founded in...

during the mid- to late 1990s, a majority of the dead were found to have a coin in the mouth. The burials dated from the 4th to the late 2nd century BC.

A notable use of a danake

Danake

The danake or danace was a small silver coin of the Persian Empire , equivalent to the Greek obol and circulated among the eastern Greeks. Later it was used by the Greeks in other metals...

occurred in the burial of a woman in 4th-century BC Thessaly

Thessaly

Thessaly is a traditional geographical region and an administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, Thessaly was known as Aeolia, and appears thus in Homer's Odyssey....

, a likely initiate into the Orphic

Orphism (religion)

Orphism is the name given to a set of religious beliefs and practices in the ancient Greek and the Hellenistic world, as well as by the Thracians, associated with literature ascribed to the mythical poet Orpheus, who descended into Hades and returned...

or Dionysiac

Dionysus

Dionysus was the god of the grape harvest, winemaking and wine, of ritual madness and ecstasy in Greek mythology. His name in Linear B tablets shows he was worshipped from c. 1500—1100 BC by Mycenean Greeks: other traces of Dionysian-type cult have been found in ancient Minoan Crete...

mysteries

Greco-Roman mysteries

Mystery religions, sacred Mysteries or simply mysteries, were religious cults of the Greco-Roman world, participation in which was reserved to initiates....

. Her religious paraphernalia included gold tablets inscribed

Totenpass

Totenpass is a German term sometimes used for inscribed tablets or metal leaves found in burials primarily of those presumed to be initiates into Orphic, Dionysiac, and some ancient Egyptian and Semitic religions...

with instructions for the afterlife

Afterlife

The afterlife is the belief that a part of, or essence of, or soul of an individual, which carries with it and confers personal identity, survives the death of the body of this world and this lifetime, by natural or supernatural means, in contrast to the belief in eternal...

and a terracotta figure

Greek Terracotta Figurines

Terracotta figurines are a mode of artistic and religious expression frequently found in Ancient Greece. Cheap and easily produced, these figurines abound and provide an invaluable testimony to the everyday life and religion of the Ancient Greeks.-Modelling:...

of a Bacchic

Cult of Dionysus

The Cult of Dionysus is strongly associated with satyrs, centaurs, and sileni, and its characteristic symbols are the bull, the serpent, the ivy, and the wine. The Dionysia and Lenaia festivals in Athens were dedicated to Dionysus, as well as the Phallic processions...

worshipper. Upon her lips was placed a gold danake stamped with the Gorgon’s head

Gorgoneion

In Ancient Greece, the Gorgoneion was originally a horror-creating apotropaic pendant showing the Gorgon's head. It was assimilated by the Olympian deities Zeus and Athena: both are said to have worn it as a protective pendant...

. Coins begin to appear with greater frequency in graves during the 3rd century BC, along with gold wreaths and plain unguentaria

Unguentarium

An unguentarium is a small ceramic or glass bottle found frequently by archaeologists at Hellenistic and Roman sites, especially in cemeteries. Its most common use was probably as a container for oil, though it is also suited for storing and dispensing liquid and powdered substances. Some finds...

(small bottles for oil) in place of the earlier lekythoi

Lekythos

A lekythos is a type of Greek pottery used for storing oil , especially olive oil. It has a narrow body and one handle attached to the neck of the vessel. The lekythos was used for anointing dead bodies of unmarried men and many lekythoi are found in tombs. The images on lekythoi were often...

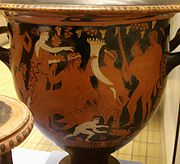

. Black-figure

Black-figure pottery

Black-figure pottery painting, also known as the black-figure style or black-figure ceramic is one of the most modern styles for adorning antique Greek vases. It was especially common between the 7th and 5th centuries BC, although there are specimens dating as late as the 2nd century BC...

lekythoi had often depicted Dionysiac

Cult of Dionysus

The Cult of Dionysus is strongly associated with satyrs, centaurs, and sileni, and its characteristic symbols are the bull, the serpent, the ivy, and the wine. The Dionysia and Lenaia festivals in Athens were dedicated to Dionysus, as well as the Phallic processions...

scenes; the later white-ground

White Ground Technique

White-ground technique is a style of ancient Greek vase painting in which figures appear on a white background. It developed in the region of Attica.-Technique and style:...

vessels often show Charon, usually with his pole, but rarely (or dubiously) accepting the coin.

The Black Sea region has also produced examples of Charon’s obol. At Apollonia Pontica

Sozopol

Sozopol is an ancient seaside town located 35 km south of Burgas on the southern Bulgarian Black Sea Coast. Today it is one of the major seaside resorts in the country, known for the Apollonia art and film festival that is named after one of the town's ancient names.The busiest times of the year...

, the custom had been practiced from the mid-4th century BC; in one cemetery, for instance, 17 percent of graves contained small bronze local coins in the mouth or hand of the deceased. During 1998 excavations of Pichvnari, on the coast of present-day Georgia

Georgia (country)

Georgia is a sovereign state in the Caucasus region of Eurasia. Located at the crossroads of Western Asia and Eastern Europe, it is bounded to the west by the Black Sea, to the north by Russia, to the southwest by Turkey, to the south by Armenia, and to the southeast by Azerbaijan. The capital of...

, a single coin was found in seven burials, and a pair of coins in two. The coins, silver triobols

Obolus

The obol was an ancient silver coin. In Classical Athens, there were six obols to the drachma, lioterally "handful"; it could be excahnged for eight chalkoi...

of the local Colchian currency, were located near the mouth, with the exception of one that was near the hand. It is unclear whether the dead were Colchians or Greeks. The investigating archaeologists did not regard the practice as typical of the region, but speculate that the local geography lent itself to adapting the Greek myth, as bodies of the dead in actuality had to be ferried across a river from the town to the cemetery.

Near East

Hellenization

Hellenization is a term used to describe the spread of ancient Greek culture, and, to a lesser extent, language. It is mainly used to describe the spread of Hellenistic civilization during the Hellenistic period following the campaigns of Alexander the Great of Macedon...

, but the practice may be independent of Greek influence in some regions. The placing of a coin in the mouth of the deceased is found also during Parthian

Parthian Empire

The Parthian Empire , also known as the Arsacid Empire , was a major Iranian political and cultural power in ancient Persia...

and Sasanian

Sassanid Empire

The Sassanid Empire , known to its inhabitants as Ērānshahr and Ērān in Middle Persian and resulting in the New Persian terms Iranshahr and Iran , was the last pre-Islamic Persian Empire, ruled by the Sasanian Dynasty from 224 to 651...

times in what is now Iran

Iran

Iran , officially the Islamic Republic of Iran , is a country in Southern and Western Asia. The name "Iran" has been in use natively since the Sassanian era and came into use internationally in 1935, before which the country was known to the Western world as Persia...

. Curiously, the coin was not the danake

Danake

The danake or danace was a small silver coin of the Persian Empire , equivalent to the Greek obol and circulated among the eastern Greeks. Later it was used by the Greeks in other metals...

of Persian origin, as it was sometimes among the Greeks, but usually a Greek drachma

Greek drachma

Drachma, pl. drachmas or drachmae was the currency used in Greece during several periods in its history:...

. In the Yazdi region, objects consecrated in graves may include a coin or piece of silver; the custom is thought to be perhaps as old as the Seleucid

Seleucid Empire

The Seleucid Empire was a Greek-Macedonian state that was created out of the eastern conquests of Alexander the Great. At the height of its power, it included central Anatolia, the Levant, Mesopotamia, Persia, today's Turkmenistan, Pamir and parts of Pakistan.The Seleucid Empire was a major centre...

era and may be a form of Charon’s obol.

Discoveries of a single coin near the skull in tombs of the Levant

Levant

The Levant or ) is the geographic region and culture zone of the "eastern Mediterranean littoral between Anatolia and Egypt" . The Levant includes most of modern Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Israel, the Palestinian territories, and sometimes parts of Turkey and Iraq, and corresponds roughly to the...

suggest a similar practice among Phoenicia

Phoenicia

Phoenicia , was an ancient civilization in Canaan which covered most of the western, coastal part of the Fertile Crescent. Several major Phoenician cities were built on the coastline of the Mediterranean. It was an enterprising maritime trading culture that spread across the Mediterranean from 1550...

ns in the Persian period. Jewish ossuaries

Ossuary

An ossuary is a chest, building, well, or site made to serve as the final resting place of human skeletal remains. They are frequently used where burial space is scarce. A body is first buried in a temporary grave, then after some years the skeletal remains are removed and placed in an ossuary...

sometimes contain a single coin; for example, in an ossuary bearing the inscriptional name “Miriam, daughter of Simeon,” a coin minted during the reign of Herod Agrippa I

Agrippa I

Agrippa I also known as Herod Agrippa or simply Herod , King of the Jews, was the grandson of Herod the Great, and son of Aristobulus IV and Berenice. His original name was Marcus Julius Agrippa, so named in honour of Roman statesman Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, and he is the king named Herod in the...

, dated 42/43 AD, was found in the skull’s mouth. Although the placement of a coin within the skull is uncommon in Jewish antiquity and was potentially an act of idolatry

Idolatry

Idolatry is a pejorative term for the worship of an idol, a physical object such as a cult image, as a god, or practices believed to verge on worship, such as giving undue honour and regard to created forms other than God. In all the Abrahamic religions idolatry is strongly forbidden, although...

, rabbinic literature

Rabbinic literature

Rabbinic literature, in its broadest sense, can mean the entire spectrum of rabbinic writings throughout Jewish history. However, the term often refers specifically to literature from the Talmudic era, as opposed to medieval and modern rabbinic writing, and thus corresponds with the Hebrew term...

preserves an allusion to Charon in a lament

Lament

A lament or lamentation is a song, poem, or piece of music expressing grief, regret, or mourning.-History:Many of the oldest and most lasting poems in human history have been laments. Laments are present in both the Iliad and the Odyssey, and laments continued to be sung in elegiacs accompanied by...

for the dead “tumbling aboard the ferry and having to borrow his fare.” Boats are sometimes depicted on ossuaries or the walls of Jewish crypt

Crypt

In architecture, a crypt is a stone chamber or vault beneath the floor of a burial vault possibly containing sarcophagi, coffins or relics....

s, and one of the coins found within a skull may have been chosen because it depicted a ship.

Western Europe

Cemeteries in the Western Roman Empire vary widely: in a 1st-century BC community in Cisalpine GaulCisalpine Gaul

Cisalpine Gaul, in Latin: Gallia Cisalpina or Citerior, also called Gallia Togata, was a Roman province until 41 BC when it was merged into Roman Italy.It bore the name Gallia, because the great body of its inhabitants, after the expulsion of the Etruscans, consisted of Gauls or Celts...

, coins were included in more than 40 percent of graves, but none was placed in the mouth of the deceased; the figure is only 10 percent for cremations at Empúries

Empúries

Empúries , formerly known by its Spanish name Ampurias , was a town on the Mediterranean coast of the Catalan comarca of Alt Empordà in Catalonia, Spain. It was founded in 575 BC by Greek colonists from Phocaea with the name of Ἐμπόριον...

in Spain and York

York

York is a walled city, situated at the confluence of the Rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. The city has a rich heritage and has provided the backdrop to major political events throughout much of its two millennia of existence...

in Britain. On the Iberian Peninsula

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula , sometimes called Iberia, is located in the extreme southwest of Europe and includes the modern-day sovereign states of Spain, Portugal and Andorra, as well as the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar...

, evidence interpreted as Charon's obol has been found at Tarragona

Hispania Tarraconensis

Hispania Tarraconensis was one of three Roman provinces in Hispania. It encompassed much of the Mediterranean coast of Spain along with the central plateau. Southern Spain, the region now called Andalusia, was the province of Hispania Baetica...

. In Belgic Gaul

Gallia Belgica

Gallia Belgica was a Roman province located in what is now the southern part of the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, northeastern France, and western Germany. The indigenous population of Gallia Belgica, the Belgae, consisted of a mixture of Celtic and Germanic tribes...

, varying deposits of coins are found with the dead for the 1st through 3rd centuries, but are most frequent in the late 4th and early 5th centuries. Thirty Gallo-Roman burials near the Pont de Pasly, Soissons

Arrondissement of Soissons

The arrondissement of Soissons is an arrondissement of France, located in the Aisne département, in the Picardie région. It has 7 cantons and 159 communes.-Cantons:The cantons of the arrondissement of Soissons are:# Braine# Oulchy-le-Château...

, each contained a coin for Charon. Germanic

Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples are an Indo-European ethno-linguistic group of Northern European origin, identified by their use of the Indo-European Germanic languages which diversified out of Proto-Germanic during the Pre-Roman Iron Age.Originating about 1800 BCE from the Corded Ware Culture on the North...

burials show a preference for gold coins, but even within a single cemetery and a narrow time period, their disposition varies.

In one Merovingian cemetery of Frénouville

Frénouville

-References:*...

, Normandy

Normandy

Normandy is a geographical region corresponding to the former Duchy of Normandy. It is in France.The continental territory covers 30,627 km² and forms the preponderant part of Normandy and roughly 5% of the territory of France. It is divided for administrative purposes into two régions:...

, which was in use for four centuries in the early Common Era

Common Era

Common Era ,abbreviated as CE, is an alternative designation for the calendar era originally introduced by Dionysius Exiguus in the 6th century, traditionally identified with Anno Domini .Dates before the year 1 CE are indicated by the usage of BCE, short for Before the Common Era Common Era...

, coins are found in a minority of the graves. At one time, the cemetery was regarded as exhibiting two distinct phases: an earlier Gallo-Roman

Gallo-Roman culture

The term Gallo-Roman describes the Romanized culture of Gaul under the rule of the Roman Empire. This was characterized by the Gaulish adoption or adaptation of Roman mores and way of life in a uniquely Gaulish context...

period when the dead were buried with vessels, notably of glass

Roman glass

Roman glass objects have been recovered across the Roman Empire in domestic, industrial and funerary contexts. Glass was used primarily for the production of vessels, although mosaic tiles and window glass were also produced. Roman glass production developed from Hellenistic technical traditions,...

, and Charon’s obol; and later, when they were given funerary dress and goods according to Frankish

Franks

The Franks were a confederation of Germanic tribes first attested in the third century AD as living north and east of the Lower Rhine River. From the third to fifth centuries some Franks raided Roman territory while other Franks joined the Roman troops in Gaul. Only the Salian Franks formed a...

custom. This neat division, however, has been shown to be misleading. In the 3rd- to 4th-century area of the cemetery, coins were placed near the skulls or hands, sometimes protected by a pouch or vessel, or were found in the grave-fill as if tossed in. Bronze coins usually numbered one or two per grave, as would be expected from the custom of Charon’s obol, but one burial contained 23 bronze coins, and another held a gold solidus and a semissis

Solidus (coin)

The solidus was originally a gold coin issued by the Romans, and a weight measure for gold more generally, corresponding to 4.5 grams.-Roman and Byzantine coinage:...

. The latter examples indicate that coins might have represented relative social status

Social status

In sociology or anthropology, social status is the honor or prestige attached to one's position in society . It may also refer to a rank or position that one holds in a group, for example son or daughter, playmate, pupil, etc....

. In the newer part of the cemetery, which remained in use through the 6th century, the deposition patterns for coinage were similar, but the coins themselves were not contemporaneous with the burials, and some were pierced for wearing. The use of older coins may reflect a shortage of new currency, or may indicate that the old coins held a traditional symbolic meaning apart from their denominational value. “The varied placement of coins of different values … demonstrates at least partial if not complete loss of understanding of the original religious function of Charon’s obol,” remarks Bonnie Effros, a specialist in Merovingian burial customs. “These factors make it difficult to determine the rite’s significance.”

.jpg)

Kent

Kent is a county in southeast England, and is one of the home counties. It borders East Sussex, Surrey and Greater London and has a defined boundary with Essex in the middle of the Thames Estuary. The ceremonial county boundaries of Kent include the shire county of Kent and the unitary borough of...

, a young man had been buried with a Merovingian gold tremissis

Tremissis

Tremissis was a currency of the Late Ancient Rome, equal to one-third of a solidus. Tremissis coins continued to be minted by descendants of the Roman Empire, such as Anglo-Saxon Britain or the Eastern Roman Empire.-External links:*...

(ca. 575) in his mouth. A gold-plated coin was found in the mouth of a young man buried on the Isle of Wight

Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight is a county and the largest island of England, located in the English Channel, on average about 2–4 miles off the south coast of the county of Hampshire, separated from the mainland by a strait called the Solent...

in the mid-6th century; his other grave goods included vessels, a drinking horn

Drinking horn

A drinking horn is the horn of a bovid used as a drinking vessel. Drinking horns are known from Classical Antiquity especially in Thrace and the Balkans, and remained in use for ceremonial purposes throughout the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period in some parts of Europe, notably in Germanic...

, a knife, and gaming-counters of ivory

Ivory

Ivory is a term for dentine, which constitutes the bulk of the teeth and tusks of animals, when used as a material for art or manufacturing. Ivory has been important since ancient times for making a range of items, from ivory carvings to false teeth, fans, dominoes, joint tubes, piano keys and...

with one cobalt-blue glass

Cobalt glass

Cobalt glass is a deep blue colored glass prepared by adding cobalt compounds to the molten glass. It is appreciated for its attractive color. It is also used as an optical filter in flame tests to filter out the yellow flame caused by the contamination of sodium, and expand the ability to see...

piece.

Scandinavia

Scandinavia

Scandinavia is a cultural, historical and ethno-linguistic region in northern Europe that includes the three kingdoms of Denmark, Norway and Sweden, characterized by their common ethno-cultural heritage and language. Modern Norway and Sweden proper are situated on the Scandinavian Peninsula,...

n and Germanic gold bracteates

Bracteate

A bracteate is a flat, thin, single-sided gold medal worn as jewelry that was produced in Northern Europe predominantly during the Migration Period of the Germanic Iron Age...

found in burials of the 5th and 6th centuries, particularly those in Britain, have also been interpreted in light of Charon’s obol. These gold disks, similar to coins though generally single-sided, were influenced by late Roman imperial coins and medallions but feature iconography

Iconography

Iconography is the branch of art history which studies the identification, description, and the interpretation of the content of images. The word iconography literally means "image writing", and comes from the Greek "image" and "to write". A secondary meaning is the painting of icons in the...

from Norse myth

Norse mythology

Norse mythology, a subset of Germanic mythology, is the overall term for the myths, legends and beliefs about supernatural beings of Norse pagans. It flourished prior to the Christianization of Scandinavia, during the Early Middle Ages, and passed into Nordic folklore, with some aspects surviving...

and runic

Runic alphabet

The runic alphabets are a set of related alphabets using letters known as runes to write various Germanic languages before the adoption of the Latin alphabet and for specialized purposes thereafter...

inscriptions. The stamping process created an extended rim that forms a frame with a loop for threading; the bracteates often appear in burials as a woman’s necklace. A function comparable to that of Charon’s obol is suggested by examples such as a man’s burial at Monkton in Kent and a group of several male graves on Gotland

Gotland

Gotland is a county, province, municipality and diocese of Sweden; it is Sweden's largest island and the largest island in the Baltic Sea. At 3,140 square kilometers in area, the region makes up less than one percent of Sweden's total land area...

, Sweden, for which the bracteate was deposited in a pouch beside the body. In the Gotland burials, the bracteates lack rim and loop, and show no traces of wear, suggesting that they had not been intended for everyday use.

According to one interpretation, the purse-hoard

Hoard

In archaeology, a hoard is a collection of valuable objects or artifacts, sometimes purposely buried in the ground. This would usually be with the intention of later recovery by the hoarder; hoarders sometimes died before retrieving the hoard, and these surviving hoards may be uncovered by...

in the Sutton Hoo

Sutton Hoo

Sutton Hoo, near to Woodbridge, in the English county of Suffolk, is the site of two 6th and early 7th century cemeteries. One contained an undisturbed ship burial including a wealth of Anglo-Saxon artefacts of outstanding art-historical and archaeological significance, now held in the British...

ship burial

Ship burial

A ship burial or boat grave is a burial in which a ship or boat is used either as a container for the dead and the grave goods, or as a part of the grave goods itself. If the ship is very small, it is called a boat grave...

(Suffolk

Suffolk

Suffolk is a non-metropolitan county of historic origin in East Anglia, England. It has borders with Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south. The North Sea lies to the east...

, East Anglia

East Anglia

East Anglia is a traditional name for a region of eastern England, named after an ancient Anglo-Saxon kingdom, the Kingdom of the East Angles. The Angles took their name from their homeland Angeln, in northern Germany. East Anglia initially consisted of Norfolk and Suffolk, but upon the marriage of...

), which contained a variety of Merovingian gold coins, unites the traditional Germanic voyage to the afterlife with “an unusually splendid form of Charon’s obol.” The burial yielded 37 gold tremisses

Tremissis

Tremissis was a currency of the Late Ancient Rome, equal to one-third of a solidus. Tremissis coins continued to be minted by descendants of the Roman Empire, such as Anglo-Saxon Britain or the Eastern Roman Empire.-External links:*...

dating from the late 6th and early 7th century, three unstruck coin blanks, and two small gold ingot

Ingot

An ingot is a material, usually metal, that is cast into a shape suitable for further processing. Non-metallic and semiconductor materials prepared in bulk form may also be referred to as ingots, particularly when cast by mold based methods.-Uses:...

s. It has been conjectured that the coins were to pay the oarsmen who would row the ship into the next world, while the ingots were meant for the steersmen. Although Charon is usually a lone figure in depictions from both antiquity and the modern era, there is some slight evidence that his ship might be furnished with oarsmen. A fragment of 6th century BC pottery has been interpreted as Charon sitting in the stern as steersman of a boat fitted with ten pairs of oars and rowed by eidola (εἴδωλα), shades of the dead. A reference in Lucian seems also to imply that the shades might row the boat.

In Scandinavia, scattered examples of Charon’s obol have been documented from the Roman Iron Age

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the archaeological period generally occurring after the Bronze Age, marked by the prevalent use of iron. The early period of the age is characterized by the widespread use of iron or steel. The adoption of such material coincided with other changes in society, including differing...

and the Migration Period

Migration Period

The Migration Period, also called the Barbarian Invasions , was a period of intensified human migration in Europe that occurred from c. 400 to 800 CE. This period marked the transition from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages...

; in the Viking

Viking

The term Viking is customarily used to refer to the Norse explorers, warriors, merchants, and pirates who raided, traded, explored and settled in wide areas of Europe, Asia and the North Atlantic islands from the late 8th to the mid-11th century.These Norsemen used their famed longships to...

period, eastern Sweden produces the best evidence, Denmark rarely, and Norway and Finland inconclusively. In the 13th and 14th centuries, Charon’s obol appears in graves in Sweden, Scania

History of Scania

The history of the province of Scania has, for many centuries, been marked by the struggle between the two Scandinavian kingdoms of Denmark and Sweden.-Viking Age history:...

, and Norway. Swedish folklore

Folklore

Folklore consists of legends, music, oral history, proverbs, jokes, popular beliefs, fairy tales and customs that are the traditions of a culture, subculture, or group. It is also the set of practices through which those expressive genres are shared. The study of folklore is sometimes called...

documents the custom from the 18th into the 20th century.

Among Christians

The custom of Charon’s obol not only continued into the Christian era, but was adopted by Christians, as a single coin was sometimes placed in the mouth for ChristianChristianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

burials. At Arcy-Sainte-Restitue

Arcy-Sainte-Restitue

Arcy-Sainte-Restitue is a commune in the department of Aisne in Picardy in northern France.-Population:-References:*...

in Picardie

Picardie

Picardy is one of the 27 regions of France. It is located in the northern part of France.-History:The historical province of Picardy stretched from north of Noyon to Calais, via the whole of the Somme department and the north of the Aisne department...

, a Merovingian grave yielded a coin of Constantine I

Constantine I

Constantine the Great , also known as Constantine I or Saint Constantine, was Roman Emperor from 306 to 337. Well known for being the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity, Constantine and co-Emperor Licinius issued the Edict of Milan in 313, which proclaimed religious tolerance of all...

, the first Christian emperor, used as Charon’s obol. In Britain, the practice was just as frequent, if not more so, among Christians, and persisted even to the end of the 19th century. A folklorist writing in 1914 was able to document a witness in Britain who had seen a penny placed in the mouth of an old man as he lay in his coffin. In 1878, Pope Pius IX

Pope Pius IX

Blessed Pope Pius IX , born Giovanni Maria Mastai-Ferretti, was the longest-reigning elected Pope in the history of the Catholic Church, serving from 16 June 1846 until his death, a period of nearly 32 years. During his pontificate, he convened the First Vatican Council in 1869, which decreed papal...

was entombed with coin. The practice was widely documented around the turn of the 19th–20th centuries in Greece, where the coin was sometimes accompanied by a key.

'Ghost' coins and crosses

- See also ExonumiaExonumiaExonumia are numismatic items other than coins and paper money. This includes "Good For" tokens, badges, counterstamped coins, elongated coins, encased coins, souvenir medallions, tags, wooden nickels and other similar items...

.

Demeter

In Greek mythology, Demeter is the goddess of the harvest, who presided over grains, the fertility of the earth, and the seasons . Her common surnames are Sito as the giver of food or corn/grain and Thesmophoros as a mark of the civilized existence of agricultural society...

/Kore

Persephone

In Greek mythology, Persephone , also called Kore , is the daughter of Zeus and the harvest-goddess Demeter, and queen of the underworld; she was abducted by Hades, the god-king of the underworld....

, was found in the skeleton’s mouth. In a marble cremation

Cremation

Cremation is the process of reducing bodies to basic chemical compounds such as gasses and bone fragments. This is accomplished through high-temperature burning, vaporization and oxidation....

box from the mid-2nd century BC, the "Charon's piece" took the form of a bit of gold foil stamped with an owl; in addition to the charred bone fragments, the box also contained gold leaves from a wreath of the type sometimes associated with the mystery religions

Greco-Roman mysteries

Mystery religions, sacred Mysteries or simply mysteries, were religious cults of the Greco-Roman world, participation in which was reserved to initiates....

. Within an Athenian family burial plot of the 2nd century BC, a thin gold disk similarly stamped with the owl of Athens had been placed in the mouth of each male.

These examples of the "Charon's piece" resemble in material and size the tiny inscribed tablet or funerary amulet called a lamella (Latin for a metal-foil sheet) or a Totenpass

Totenpass

Totenpass is a German term sometimes used for inscribed tablets or metal leaves found in burials primarily of those presumed to be initiates into Orphic, Dionysiac, and some ancient Egyptian and Semitic religions...

, a “passport for the dead” with instructions on navigating the afterlife, conventionally regarded as a form of Orphic or Dionysiac devotional. Several of these prayer sheets have been found in positions that indicate placement in or on the deceased's mouth. A functional equivalence with the Charon's piece is further suggested by the evidence of flattened coins used as mouth coverings (epistomia) from graves in Crete. A gold phylactery with a damaged inscription invoking the syncretic

Syncretism

Syncretism is the combining of different beliefs, often while melding practices of various schools of thought. The term means "combining", but see below for the origin of the word...

god Sarapis

Serapis

Serapis or Sarapis is a Graeco-Egyptian name of God. Serapis was devised during the 3rd century BC on the orders of Ptolemy I of Egypt as a means to unify the Greeks and Egyptians in his realm. The god was depicted as Greek in appearance, but with Egyptian trappings, and combined iconography...

was found within the skull in a burial from the late 1st century AD in southern Rome. The gold tablet may have served both as a protective amulet during the deceased’s lifetime and then, with its insertion into the mouth, possibly on the model of Charon’s obol, as a Totenpass

Totenpass

Totenpass is a German term sometimes used for inscribed tablets or metal leaves found in burials primarily of those presumed to be initiates into Orphic, Dionysiac, and some ancient Egyptian and Semitic religions...

.

Douris (Baalbek)

Douris is a village located approximately 3 km. southwest of Baalbek in the Bekaa Valley, Lebanon. It is the site of a necropolis from the late Roman Imperial period that is currently undergoing archaeological investigation.-External links:...

, near Baalbek

Baalbek

Baalbek is a town in the Beqaa Valley of Lebanon, altitude , situated east of the Litani River. It is famous for its exquisitely detailed yet monumentally scaled temple ruins of the Roman period, when Baalbek, then known as Heliopolis, was one of the largest sanctuaries in the Empire...

, Lebanon

Lebanon

Lebanon , officially the Republic of LebanonRepublic of Lebanon is the most common term used by Lebanese government agencies. The term Lebanese Republic, a literal translation of the official Arabic and French names that is not used in today's world. Arabic is the most common language spoken among...

, the forehead, nose, and mouth of the deceased — a woman, in so far as skeletal remains can indicate — were covered with sheets of gold-leaf. She wore a wreath made from gold oak leaves, and her clothing had been sewn with gold-leaf ovals decorated with female faces. Several glass vessels

Roman glass

Roman glass objects have been recovered across the Roman Empire in domestic, industrial and funerary contexts. Glass was used primarily for the production of vessels, although mosaic tiles and window glass were also produced. Roman glass production developed from Hellenistic technical traditions,...

were arranged at her feet, and her discoverers interpreted the bronze coin close to her head as an example of Charon’s obol.

Textual evidence also exists for covering portions of the deceased’s body with gold foil. One of the accusations of heresy

Heresy

Heresy is a controversial or novel change to a system of beliefs, especially a religion, that conflicts with established dogma. It is distinct from apostasy, which is the formal denunciation of one's religion, principles or cause, and blasphemy, which is irreverence toward religion...

against the Phrygia

Phrygia

In antiquity, Phrygia was a kingdom in the west central part of Anatolia, in what is now modern-day Turkey. The Phrygians initially lived in the southern Balkans; according to Herodotus, under the name of Bryges , changing it to Phruges after their final migration to Anatolia, via the...

n Christian movement known as the Montanists

Montanism

Montanism was an early Christian movement of the late 2nd century, later referred to by the name of its founder, Montanus, but originally known by its adherents as the New Prophecy...

was that they sealed the mouths of their dead with plates of gold like initiates into the mysteries

Greco-Roman mysteries

Mystery religions, sacred Mysteries or simply mysteries, were religious cults of the Greco-Roman world, participation in which was reserved to initiates....

; factual or not, the charge indicates an anxiety that Christian practice be distinguished from that of other religions, and again suggests that Charon’s obol and the “Orphic” gold tablets could fulfill a similar purpose. The early Christian

Early Christianity

Early Christianity is generally considered as Christianity before 325. The New Testament's Book of Acts and Epistle to the Galatians records that the first Christian community was centered in Jerusalem and its leaders included James, Peter and John....

poet Prudentius

Prudentius

Aurelius Prudentius Clemens was a Roman Christian poet, born in the Roman province of Tarraconensis in 348. He probably died in Spain, as well, some time after 405, possibly around 413...

seems to be referring either to these inscribed gold-leaf tablets or to the larger gold-foil coverings in one of his condemnations of the mystery religions. Prudentius says that auri lammina (“sheets of gold”) were placed on the bodies of initiates as part of funeral rites. This practice may or may not be distinct from the funerary use of gold leaf inscribed with figures and placed on the eyes, mouths, and chests of warriors in Macedon

Macedon

Macedonia or Macedon was an ancient kingdom, centered in the northeastern part of the Greek peninsula, bordered by Epirus to the west, Paeonia to the north, the region of Thrace to the east and Thessaly to the south....

ian burials during the late Archaic period

Archaic period in Greece

The Archaic period in Greece was a period of ancient Greek history that followed the Greek Dark Ages. This period saw the rise of the polis and the founding of colonies, as well as the first inklings of classical philosophy, theatre in the form of tragedies performed during Dionysia, and written...

(580–460 BC); in September 2008, archaeologists working near Pella

Pella

Pella , an ancient Greek city located in Pella Prefecture of Macedonia in Greece, was the capital of the ancient kingdom of Macedonia.-Etymology:...

in northern Greece publicized the discovery of twenty warrior graves in which the deceased wore bronze helmets and were supplied with iron swords and knives along with these gold-leaf coverings.

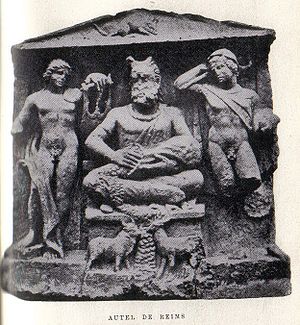

Goldblattkreuze

Alamanni

The Alamanni, Allemanni, or Alemanni were originally an alliance of Germanic tribes located around the upper Rhine river . One of the earliest references to them is the cognomen Alamannicus assumed by Roman Emperor Caracalla, who ruled the Roman Empire from 211 to 217 and claimed thereby to be...

territory, Christian graves of the Merovingian period reveal an analogous Christianized

Christianization

The historical phenomenon of Christianization is the conversion of individuals to Christianity or the conversion of entire peoples at once...

practice in the form of gold or gold-alloy leaf shaped like a cross, imprinted with designs, and deposited possibly as votives or amulets for the deceased. These paper-thin, fragile gold crosses are sometimes referred to by scholars with the German

German language

German is a West Germanic language, related to and classified alongside English and Dutch. With an estimated 90 – 98 million native speakers, German is one of the world's major languages and is the most widely-spoken first language in the European Union....

term Goldblattkreuze. They appear to have been sown onto the deceased’s garment just before burial, not worn during life, and in this practice are comparable to the pierced Roman coins found in Anglo-Saxon graves that were attached to clothing instead of or in addition to being threaded onto a necklace.

The crosses are characteristic of Lombardic Italy

Lombardy

Lombardy is one of the 20 regions of Italy. The capital is Milan. One-sixth of Italy's population lives in Lombardy and about one fifth of Italy's GDP is produced in this region, making it the most populous and richest region in the country and one of the richest in the whole of Europe...

(Cisalpine Gaul

Cisalpine Gaul

Cisalpine Gaul, in Latin: Gallia Cisalpina or Citerior, also called Gallia Togata, was a Roman province until 41 BC when it was merged into Roman Italy.It bore the name Gallia, because the great body of its inhabitants, after the expulsion of the Etruscans, consisted of Gauls or Celts...

of the Roman imperial era), where they were fastened to veils and placed over the deceased's mouth in a continuation of Byzantine

Byzantine

Byzantine usually refers to the Roman Empire during the Middle Ages.Byzantine may also refer to:* A citizen of the Byzantine Empire, or native Greek during the Middle Ages...

practice. Throughout the Lombardic realm and north into Germanic territory, the crosses gradually replaced bracteate

Bracteate

A bracteate is a flat, thin, single-sided gold medal worn as jewelry that was produced in Northern Europe predominantly during the Migration Period of the Germanic Iron Age...

s during the 7th century. The transition is signalled by Scandinavian bracteates found in Kent

Kent

Kent is a county in southeast England, and is one of the home counties. It borders East Sussex, Surrey and Greater London and has a defined boundary with Essex in the middle of the Thames Estuary. The ceremonial county boundaries of Kent include the shire county of Kent and the unitary borough of...

that are stamped with cross motifs resembling the Lombardic crosses. Two plain gold-foil crosses of Latin form, found in the burial of a 7th-century East Saxon king

Kingdom of Essex

The Kingdom of Essex or Kingdom of the East Saxons was one of the seven traditional kingdoms of the so-called Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy. It was founded in the 6th century and covered the territory later occupied by the counties of Essex, Hertfordshire, Middlesex and Kent. Kings of Essex were...