Christianity in Cornwall

Encyclopedia

Western Christianity

Western Christianity is a term used to include the Latin Rite of the Catholic Church and groups historically derivative thereof, including the churches of the Anglican and Protestant traditions, which share common attributes that can be traced back to their medieval heritage...

was introduced into Cornwall

Cornwall

Cornwall is a unitary authority and ceremonial county of England, within the United Kingdom. It is bordered to the north and west by the Celtic Sea, to the south by the English Channel, and to the east by the county of Devon, over the River Tamar. Cornwall has a population of , and covers an area of...

along with the rest of Roman Britain

Roman Britain

Roman Britain was the part of the island of Great Britain controlled by the Roman Empire from AD 43 until ca. AD 410.The Romans referred to the imperial province as Britannia, which eventually comprised all of the island of Great Britain south of the fluid frontier with Caledonia...

. Over time it became the official religion, superseding previous Celtic and Roman practice

Religion in ancient Rome

Religion in ancient Rome encompassed the religious beliefs and cult practices regarded by the Romans as indigenous and central to their identity as a people, as well as the various and many cults imported from other peoples brought under Roman rule. Romans thus offered cult to innumerable deities...

. Early Christianity in Cornwall was spread largely by the saint

Saint

A saint is a holy person. In various religions, saints are people who are believed to have exceptional holiness.In Christian usage, "saint" refers to any believer who is "in Christ", and in whom Christ dwells, whether in heaven or in earth...

s, including Piran

Saint Piran

Saint Piran or Perran is an early 6th century Cornish abbot and saint, supposedly of Irish origin....

, the patron of the county. Cornwall, like other parts of Britain, is sometimes associated with the distinct collection of practices known as Celtic Christianity

Celtic Christianity

Celtic Christianity or Insular Christianity refers broadly to certain features of Christianity that were common, or held to be common, across the Celtic-speaking world during the Early Middle Ages...

but was always in communion with the wider Catholic Church. The Cornish saints are commemorated in legends, churches and placenames.

In contrast to Wales

Wales

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and the island of Great Britain, bordered by England to its east and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population of three million, and a total area of 20,779 km²...

, which produced Welsh Bible

Welsh Bible

Bible translations into Welsh have existed since at least the 15th century, but the most widely used translation of the Bible into Welsh for several centuries was the 1588 translation by William Morgan, as revised in 1620...

s, the churches of Cornwall never produced a translation of the Bible

Bible

The Bible refers to any one of the collections of the primary religious texts of Judaism and Christianity. There is no common version of the Bible, as the individual books , their contents and their order vary among denominations...

in the Cornish language

Cornish language

Cornish is a Brythonic Celtic language and a recognised minority language of the United Kingdom. Along with Welsh and Breton, it is directly descended from the ancient British language spoken throughout much of Britain before the English language came to dominate...

, which may have contributed to that language's demise.. During the English Reformation

English Reformation

The English Reformation was the series of events in 16th-century England by which the Church of England broke away from the authority of the Pope and the Roman Catholic Church....

, churches in Cornwall officially became affiliated with the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

. In 1549, the Prayer Book Rebellion

Prayer Book Rebellion

The Prayer Book Rebellion, Prayer Book Revolt, Prayer Book Rising, Western Rising or Western Rebellion was a popular revolt in Cornwall and Devon, in 1549. In 1549 the Book of Common Prayer, presenting the theology of the English Reformation, was introduced...

caused the deaths of thousands of people from Devon

Devon

Devon is a large county in southwestern England. The county is sometimes referred to as Devonshire, although the term is rarely used inside the county itself as the county has never been officially "shired", it often indicates a traditional or historical context.The county shares borders with...

and Cornwall. The Methodism

Methodism

Methodism is a movement of Protestant Christianity represented by a number of denominations and organizations, claiming a total of approximately seventy million adherents worldwide. The movement traces its roots to John Wesley's evangelistic revival movement within Anglicanism. His younger brother...

of John Wesley

John Wesley

John Wesley was a Church of England cleric and Christian theologian. Wesley is largely credited, along with his brother Charles Wesley, as founding the Methodist movement which began when he took to open-air preaching in a similar manner to George Whitefield...

proved to be very popular with the working classes in Cornwall in the 19th century. Methodist chapels became important social centres, with male voice choirs and other church-affiliated groups playing a central role in the social lives of working class Cornishmen. Methodism still plays a large part in the religious life of Cornwall today, although Cornwall has shared in the post-World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

decline in British religious feeling.

Early history and legend

Priscillian

Priscillian was bishop of Ávila and a theologian from Roman Gallaecia , the first person in the history of Christianity to be executed for heresy . He founded an ascetic group that, in spite of persecution, continued to subsist in Hispania and Gaul until the later 6th century...

and were banished after the Council of Bordeaux

Bordeaux

Bordeaux is a port city on the Garonne River in the Gironde department in southwestern France.The Bordeaux-Arcachon-Libourne metropolitan area, has a population of 1,010,000 and constitutes the sixth-largest urban area in France. It is the capital of the Aquitaine region, as well as the prefecture...

in 384. Toleration was granted to the Christians of the Roman Empire in 313 and there was some growth in the church in Roman Britain in the following hundred years, mainly in urban centres. There were no known cities (L castrum, OE caester, W caer, Br Ker ) west of Exeter so Cornwall may have remained pagan at least until the 5th century, the presumed period of the mythical Christian King of the Britons, Arthur Pendragon. During the 5th century the earliest inscribed stones have inscriptions in Latin or Ogham script and some have Christian symbols. Precise dating is impossible for these stones but they are thought to come from the 5th to 11th centuries. Both the inscriptions and the Ruin of Britain by Gildas

Gildas

Gildas was a 6th-century British cleric. He is one of the best-documented figures of the Christian church in the British Isles during this period. His renowned learning and literary style earned him the designation Gildas Sapiens...

suggest that the leading families of Dumnonia

Dumnonia

Dumnonia is the Latinised name for the Brythonic kingdom in sub-Roman Britain between the late 4th and late 8th centuries, located in the farther parts of the south-west peninsula of Great Britain...

were Christian in the 6th century.. Many early medieval settlements in the region were occupied by hermitage chapels which are often dedicated to St Michael

St Michael

St Michael was a brand that was owned and used by Marks & Spencer from 1928 until 2000.-History:The brand was introduced by Simon Marks in 1928, after his father and co-founder of Marks & Spencer, Michael Marks. By 1950, virtually all goods were sold under the St Michael brand...

as the conventional slayer of pagan demons, as at St Michaels Mount.

Many place names in Cornwall are associated with Christian missionaries described as coming from Ireland and Wales in the 5th century AD and usually called saints (See List of Cornish saints). The historicity of some of these missionaries is problematic and it has been pointed out by Canon Doble

Gilbert Hunter Doble

Gilbert Hunter Doble was an Anglican priest and Cornish historian and hagiographer.-Early life:G. H. Doble was born at Penzance, Cornwall on 26 November 1880. His father, John Medley Doble shared his enthusiasm for archaeology and local studies with his sons. He was a scholar of Exeter College,...

that it was customary in the Middle Ages to ascribe such geographic origins to saints. Some of these saints are not included in the early lists of saints.

The Saints' Way

Saints' Way

The Saints' Way is a long-distance footpath in Cornwall, in the United Kingdom.The footpath runs from Padstow in the north to Fowey in the south, a distance of 26 miles . The path is well marked and guide books are available....

, a long-distance footpath, follows the probable route of early Christian

Christian

A Christian is a person who adheres to Christianity, an Abrahamic, monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth as recorded in the Canonical gospels and the letters of the New Testament...

travellers making their way from Ireland

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

to the Continent. Rather than risk the difficult passage around Land's End

Land's End

Land's End is a headland and small settlement in west Cornwall, England, within the United Kingdom. It is located on the Penwith peninsula approximately eight miles west-southwest of Penzance....

they would disembark their ships on the North Cornish coast (in the Camel estuary) and progress to ports such as Fowey

Fowey

Fowey is a small town, civil parish and cargo port at the mouth of the River Fowey in south Cornwall, United Kingdom. According to the 2001 census it had a population of 2,273.-Early history:...

on foot.

Like some other parts of Britain Cornwall derived much of its Christianity from post-Patrician Irish missions. Saint Ia of Cornwall

Ia of Cornwall

Saint Ia of Cornwall was a 5th or 6th century Cornish evangelist and martyr.Ia was said to have been an Irish princess, the sister of Saint Erc. She was a spiritual student of Saint Baricus and travelled as a missionary to Cornwall where she joined Saints Fingar and Piala...

and her companions, and Saint Piran, Saint Sennen

Sennen

Sennen is a coastal civil parish and a village in Cornwall, United Kingdom. Sennen village is situated approximately eight miles west-southwest of Penzance....

, Saint Petroc, and the rest of the saints who came to Cornwall in the late 5th century and early 6th century found there a population which had perhaps relapsed into paganism under the pagan King Teudar. When these saints introduced, or reintroduced, Christianity, they probably brought with them whatever rites they were accustomed to, and Cornwall certainly had its own separate ecclesiastical quarrel with Wessex in the days of Saint Aldhelm, which, as appears by a statement in the Leofric Missal

Leofric Missal

The Leofric Missal is an illuminated manuscript, not strictly a conventional missal, from the 10th and 11th century, now in the Bodleian Library at Oxford University where it is catalogued as Bodley 579....

, was still going on in the early 10th century, though the details of it are not specified.

It is notable that in Cornwall that most of the parish churches in existence in Norman times were generally not in the larger settlements and that the medieval towns which developed thereafter usually had only a chapel of ease with the right of burial remaining at the ancient parish church. Over a hundred holy wells exist in Cornwall, each associated with a particular saint, though not always the same one as the dedication of the church. In the Domesday Survey the church had considerable holdings of land but the Earl of Cornwall

Robert, Count of Mortain

Robert, Count of Mortain, 1st Earl of Cornwall was a Norman nobleman and the half-brother of William I of England. Robert was the son of Herluin de Conteville and Herleva of Falaise and was full brother to Odo of Bayeux. The exact year of Robert's birth is unknown Robert, Count of Mortain, 1st...

had appropriated a number of manors formerly held by monasteries. The monasteries of St Michael's Mount, Bodmin, and Tavistock

Tavistock Abbey

Tavistock Abbey, also known as the Abbey of Saint Mary and Saint Rumon, is a ruined Benedictine abbey in Tavistock, Devon. Nothing remains of the abbey except the refectory, two gateways and a porch. The abbey church, dedicated to Our Lady and St Rumon, was destroyed by Danish raiders in 997 and...

, and the canons of St Piran, St Keverne, Probus, Crantock, St Buryan and St Stephen's all had land at this time.

Various kinds of religious houses existed in medieval Cornwall though none of them were nunneries; the benefices of the parishes were in many cases appropriated to religious houses within Cornwall or elsewhere in England or France. There were also a number of peculiar

Royal Peculiar

A Royal Peculiar is a place of worship that falls directly under the jurisdiction of the British monarch, rather than under a bishop. The concept dates from Anglo-Saxon times, when a church could ally itself with the monarch and therefore not be subject to the bishop of the area...

s, areas outside the diocesan administration. Four of these were directly under the Bishop of Exeter, i.e. Lawhitton, St Germans, Pawton, and Penryn; Perranzabuloe was a peculiar of Exeter Cathedral and St Buryan of the Kings of England. From the time of Bishop William Warelwast

William Warelwast

William Warelwast, sometimes known as William de Warelwast was a medieval Norman cleric and Bishop of Exeter in England. Warelwast was a native of Normandy, but little is known about his background before 1087, when he appears as a royal clerk for King William II of England...

the administration of the remainder of Cornwall was in the hands of the Archdeacon of Cornwall and visits by the Bishop became more infrequent; only bishops could consecrate churches or conduct confirmations.

St Piran, after whom Perranporth

Perranporth

Perranporth is a small seaside resort on the north coast of Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is southwest of Newquay and northwest of Truro. Perranporth and its long beach face the Atlantic Ocean....

is named, is generally regarded as the patron saint of Cornwall.

However in earlier times it is likely that St Michael the Archangel was recognized as the patron saint and the title has also been claimed for St Petroc. (The cult of St Michael is found in Norman times and is seen in the naming of St Michael's Mount after the similarly named monastery in Normandy.

Diocese of Cornwall

The church in Cornwall until the time of Athelstan of Wessex observed more or less orthodox practices, being completely separate from the Anglo-Saxon church until then (and perhaps later). The See of Cornwall continued until much later: Bishop ConanConan of Cornwall

Conan was a medieval Bishop of Cornwall.He was nominated about 926 by King Athelstan. He was consecrated before 931. He died between 937 and 955.-References:...

apparently in place previously, but (re-?)consecrated in 931 AD by Athelstan. However, it is unclear whether he was the sole Bishop for Cornwall

Bishop of Cornwall

The Bishop of Cornwall was an episcopal title which was used by Anglo Saxons between the 9th and 11th centuries. The bishop's seat was located at the village of St Germans, Cornwall. Later bishops of Cornwall were sometimes referred to as the bishops of St Germans...

or the leading Bishop in the area. The situation in Cornwall may have been somewhat similar to Wales where each major religious house equated to a kevrang (cf. Welsh cantref), each under the control of a Bishop.

By the 880s the Church in Cornwall was having more Saxon priests appointed to it and they controlled some church estates like Polltun, Caellwic and Landwithan (Pawton, in St Breock

St Breock

St Breock is a village and a civil parish in north Cornwall, United Kingdom. St Breock village is 1 mile west of Wadebridge immediately to the south of the Royal Cornwall Showground. The village lies on the eastern slope of the wooded Nansent valley...

; perhaps Celliwig

Celliwig

Celliwig, Kelliwic or Gelliwic, is perhaps the earliest named location for the court of King Arthur. It may be translated as 'forest grove'.-Literary references:...

(Kellywick in Egloshayle

Egloshayle

Egloshayle is a civil parish and village in north Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The village is situated beside the River Camel immediately southeast of Wadebridge. The civil parish extends southeast from the village and includes Washaway and Sladesbridge.-History:Egloshayle was a Bronze Age...

?); and Lawhitton

Lawhitton

Lawhitton is a civil parish and village in east Cornwall, United Kingdom. The village is situated two miles southwest of Launceston and half-a-mile west of Cornwall's border with Devon at the River Tamar....

. Eventually they passed these over to Wessex kings. However according to Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great was King of Wessex from 871 to 899.Alfred is noted for his defence of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of southern England against the Vikings, becoming the only English monarch still to be accorded the epithet "the Great". Alfred was the first King of the West Saxons to style himself...

's will the amount of land he owned in Cornwall was very small. West of the Tamar Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great was King of Wessex from 871 to 899.Alfred is noted for his defence of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of southern England against the Vikings, becoming the only English monarch still to be accorded the epithet "the Great". Alfred was the first King of the West Saxons to style himself...

only owned a small area in the Stratton

Stratton, Cornwall

Stratton is a small town situated near the coastal resort of Bude in north Cornwall, UK. It was also the name of one of ten ancient administrative shires of Cornwall - see "Hundreds of Cornwall"...

region, plus a few other small estates around Lifton on Cornish soil east of the Tamar). These were provided to him illicitly through the Church whose Canterbury- appointed priesthood was increasingly English dominated.

William of Malmesbury

William of Malmesbury

William of Malmesbury was the foremost English historian of the 12th century. C. Warren Hollister so ranks him among the most talented generation of writers of history since Bede, "a gifted historical scholar and an omnivorous reader, impressively well versed in the literature of classical,...

, writing around 1120, says that King Athelstan of England (924–939) fixed Cornwall's eastern boundary at the east bank of the Tamar

River Tamar

The Tamar is a river in South West England, that forms most of the border between Devon and Cornwall . It is one of several British rivers whose ancient name is assumed to be derived from a prehistoric river word apparently meaning "dark flowing" and which it shares with the River Thames.The...

and the remaining Cornish were evicted from Exeter

Exeter

Exeter is a historic city in Devon, England. It lies within the ceremonial county of Devon, of which it is the county town as well as the home of Devon County Council. Currently the administrative area has the status of a non-metropolitan district, and is therefore under the administration of the...

and perhaps the rest of Devon: "Exeter was cleansed of its defilement by wiping out that filthy race". These British speakers were deported across the Tamar, which was fixed as the border of the Cornish; they were left under their own dynasty to regulate themselves with west Welsh tribal law and customs, rather like the Indian princes under the Raj in the 19th century and early 20th century. By 944 Athelstan's successor, Edmund I of England

Edmund I of England

Edmund I , called the Elder, the Deed-doer, the Just, or the Magnificent, was King of England from 939 until his death. He was a son of Edward the Elder and half-brother of Athelstan. Athelstan died on 27 October 939, and Edmund succeeded him as king.-Military threats:Shortly after his...

, styled himself 'King of the English and ruler of this province of the Britons', an indication of how that accommodation was understood at the time.

The early organisation and affiliations of the Church in Cornwall are unclear, but in the mid-9th century it was led by a Bishop Kenstec

Kenstec

Kenstec was a medieval Bishop of Cornwall.He was consecrated between 833 and 870. His death date is unknown.-References:* Powicke, F. Maurice and E. B. Fryde Handbook of British Chronology 2nd. ed. London:Royal Historical Society 1961-External links:...

with his see at Dinurrin, a location which has sometimes been identified as Bodmin

Bodmin

Bodmin is a civil parish and major town in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is situated in the centre of the county southwest of Bodmin Moor.The extent of the civil parish corresponds fairly closely to that of the town so is mostly urban in character...

and sometimes as Gerrans

Gerrans

Gerrans is a coastal civil parish and village on the Roseland Peninsula in Cornwall, United Kingdom. The village adjoins Portscatho on the east side of the peninsula...

. Kenstec acknowledged the authority of Ceolnoth

Ceolnoth

-Biography:Gervase of Canterbury says that Ceolnoth was Dean of the see of Canterbury previous to being elected to the archiepiscopal see of Canterbury, but this story has no confirmation in contemporary records. Ceolnoth was consecrated archbishop on 27 July 833...

, bringing Cornwall under the jurisdiction of the Archbishop of Canterbury

Archbishop of Canterbury

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. In his role as head of the Anglican Communion, the archbishop leads the third largest group...

. In the 920s or 930s King Athelstan established a bishopric at St Germans to cover the whole of Cornwall, which seems to have been initially subordinated to the see of Sherborne

Sherborne

Sherborne is a market town in northwest Dorset, England. It is sited on the River Yeo, on the edge of the Blackmore Vale, east of Yeovil. The A30 road, which connects London to Penzance, runs through the town. The population of the town is 9,350 . 27.1% of the population is aged 65 or...

but emerged as a full bishopric (with a Bishop of Cornwall) in its own right by the end of the 10th century. The first few bishops here were native Cornish, but those appointed from 963 onwards were all English. From around 1027 the see was held jointly with that of Crediton

Bishop of Crediton

The Bishop of Crediton was originally a prelate who administered an Anglo-Saxon diocese in the 10th and 11th centuries, and is presently a suffragan bishop who assists the diocesan bishop.-Diocesan Bishops of Crediton:...

, and in 1050 they were merged to become the diocese of Exeter

Bishop of Exeter

The Bishop of Exeter is the Ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Exeter in the Province of Canterbury. The incumbent usually signs his name as Exon or incorporates this in his signature....

.

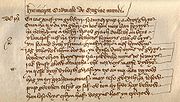

The Bodmin Gospels

Bodmin manumissions

The Bodmin manumissions or Bodmin Gospels is a manuscript supposed to be of the 9th century. The document is of interest to language scholars as it contains writing in Latin, Saxon and Cornish texts....

is believed to be the only original record relating to Cornwall

Cornwall

Cornwall is a unitary authority and ceremonial county of England, within the United Kingdom. It is bordered to the north and west by the Celtic Sea, to the south by the English Channel, and to the east by the county of Devon, over the River Tamar. Cornwall has a population of , and covers an area of...

, or its Bishopric

Diocese

A diocese is the district or see under the supervision of a bishop. It is divided into parishes.An archdiocese is more significant than a diocese. An archdiocese is presided over by an archbishop whose see may have or had importance due to size or historical significance...

, predating the Norman Conquest.

Liturgy

There is a Mass in Bodl. MS. 572 (at Oxford), in honour of St. Germanus, which appears to be Cornish and relates to "Ecclesia Lanaledensis", which has been considered to be the monastery of St. GermanusSt German's Priory

St German's Priory is a large Norman church in the village of St Germans in south-east Cornwall, in the United Kingdom.-History:According to a credible tradition the church here was founded by St Germanus himself ca. 430 AD. The first written record however is of Conan being made Bishop in the...

, in Cornwall. There is no other evidence of the name, which was also the Breton name of Aleth, now part of Saint-Malo. The manuscript, which contains also certain glosses, possibly Cornish or Breton—it would be impossible to distinguish between them at that date—but held by Professor Loth to be Welsh, is probably of the 9th century, and the Mass is quite Roman in type, being probably written after that part of Cornwall had come under Saxon influence. There is a very interesting Proper Preface.

Joseph of Arimathea

Ding Dong mine, reputedly one of the oldest in Cornwall, in the parish of GulvalGulval

Gulval is a village in the former Penwith district of Cornwall, United Kingdom. Although historically a parish in its own right, Gulval was incorporated into the parishes of Penzance, Madron and Ludgvan in 1934, and like Heamoor, is now considered to be a suburb of Penzance...

is said in local legend to have been visited by Joseph of Arimathea

Joseph of Arimathea

Joseph of Arimathea was, according to the Gospels, the man who donated his own prepared tomb for the burial of Jesus after Jesus' Crucifixion. He is mentioned in all four Gospels.-Gospel references:...

, a tin trader, and that he brought a young Jesus to address the miners, although there is no evidence to support this.

Sixteenth and seventeenth centuries

Tudor period, 1509–1603

The failure to translate the first Prayer Book into the Cornish languageCornish language

Cornish is a Brythonic Celtic language and a recognised minority language of the United Kingdom. Along with Welsh and Breton, it is directly descended from the ancient British language spoken throughout much of Britain before the English language came to dominate...

and the imposition of English liturgy over the Latin rite in the whole of Cornwall, was one of the reasons which led to the Prayer Book Rebellion

Prayer Book Rebellion

The Prayer Book Rebellion, Prayer Book Revolt, Prayer Book Rising, Western Rising or Western Rebellion was a popular revolt in Cornwall and Devon, in 1549. In 1549 the Book of Common Prayer, presenting the theology of the English Reformation, was introduced...

of 1549. There had already been dissent in Cornwall from the changes in the church enacted by the government of Edward VI abolishing chantries and reforming some aspects of the liturgy. The Cornish

Cornish people

The Cornish are a people associated with Cornwall, a county and Duchy in the south-west of the United Kingdom that is seen in some respects as distinct from England, having more in common with the other Celtic parts of the United Kingdom such as Wales, as well as with other Celtic nations in Europe...

, amongst other reasons, objected to the English language Book of Common Prayer

Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer is the short title of a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion, as well as by the Continuing Anglican, "Anglican realignment" and other Anglican churches. The original book, published in 1549 , in the reign of Edward VI, was a product of the English...

, protesting that the English language was still unknown to many at the time. Edward Seymour

Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset

Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, 1st Earl of Hertford, 1st Viscount Beauchamp of Hache, KG, Earl Marshal was Lord Protector of England in the period between the death of Henry VIII in 1547 and his own indictment in 1549....

, 1st Duke of Somerset

Duke of Somerset

Duke of Somerset is a title in the peerage of England that has been created several times. Derived from Somerset, it is particularly associated with two families; the Beauforts who held the title from the creation of 1448 and the Seymours, from the creation of 1547 and in whose name the title is...

on behalf of the Crown, expressed no sympathy pointing out that the old rites and prayers had been in Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

—also a foreign language—and there was thus no reason for the Cornish to complain. The Prayer Book Rebellion was a cultural and social disaster for Cornwall, the reprisals taken by the forces of the Crown have been estimated to account for 10-11% of the civilian population of Cornwall. Culturally speaking, it saw the beginning of the slow "death" of the Cornish language

Cornish language

Cornish is a Brythonic Celtic language and a recognised minority language of the United Kingdom. Along with Welsh and Breton, it is directly descended from the ancient British language spoken throughout much of Britain before the English language came to dominate...

.

Penal laws against Roman Catholics were enacted by the English government in 1571 and 1581. By this time people of papal sympathies were a small minority but they included the two powerful families of Arundell and Tregian. A priest (Cuthbert Mayne

Cuthbert Mayne

'Saint Cuthbert Mayne was an English Roman Catholic priest and martyr of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation.- Early life :...

) harboured by the Tregians was arrested and eventually executed at Launceston in 1577. Francis Tregian

Francis Tregian the Elder

Francis Tregian the Elder was the son of Thomas Tregian of Wolvenden of Probus, Cornwall and Catherine Arundell. A staunch Catholic, he inherited substantial estates on the death of his father, including the manors of Bedock, Landegy, Lanner and Carvolghe, and the family home, 'Golden', in the...

was punished by imprisonment and the loss of some of his lands. Others who were adherents of the old faith went into exile, including the rectors of St Michael Penkevil and St Just in Roseland

St Just in Roseland

St Just in Roseland is a civil parish and village in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The village is situated six miles south of Truro and two miles north of St Mawes....

, Thomas Bluett and John Vivian respectively. Among laymen the most notable was Nicholas Roscarrock, who was imprisoned and compiled while in prison a register of British saints.

From that time Christianity in Cornwall was in the main within the Church of England and subject to the national events which affected it in the next century and a half. Roman Catholicism never became extinct, though openly practised by very few. Also at this period there was an increase in adherents of the Puritan position as evidenced by the acquisition of large communion cups in many parishes in the 1570s.

Stuart period, 1603–1714

In the reign of Charles I, the leading gentry of the Puritan party were the Robarteses of Lanhydrock, the Bullers of Morval, the Boscawens of Tregothnan and the Rouses of Halton, while Puritan clergy were to be found at Blisland, Morval, Landrake, and Mylor. However during the Civil War there was much more support in Cornwall for the Anglican and Royalist position and the military successes of the Royalist army delayed any imposition of Presbyteriansim in church administration. The Parliamentary success in 1645 led to the ejection of the Bishop of Exeter and the depriving of the cathedral chapter. In 1646 the 72 clergy regarded as unacceptable to the county committee were required to subscribe to the new order. Some submitted while others were obstinate and so were deprived of their benefices. Civil marriage was instituted in 1653 but was not popular; much iconoclasm took place in churches such as the destruction of the stained glass at St Agnes and the rood screen at St Ives. The church organs at Launceston and St Ives were also destroyed.During the 17th century, adherents of Roman Catholicism tended to diminish since only a few could afford the penalties exacted by the government. Lanherne, the Cornish home of the Arundells in Mawgan in Pydar, was the most important centre, while the religious census of 1671 recorded recusants also in the parishes of Treneglos, Cardinham, Newlyn East and St Ervan. In the Civil War the recusants were firmly of Royalist sympathies since they had more to fear from a Parliament opposed to prelacy and popery. Sir John Arundell (born ca. 1625) fought gallantly for King Charles in the Cornish campaign, which he joined in 1644, and continued to live at Lanherne until his death in 1701.

At the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, ministers unwilling to conform to the Church of England were ejected from the benefices. Under the Conventicle Act of 1664

Conventicle Act 1664

The Conventicle Act of 1664 was an Act of the Parliament of England that forbade conventicles...

non-Anglican services were only permitted in private houses and only with five persons attending apart from the household. In Cornwall, there were about 50 ejected ministers, some of whom persisted in conducting meetings in out of the way places: these included Thomas Tregosse

Thomas Tregosse

Rev. Thomas Tregosse of Cornwall was a Puritan minister and vicar of the Rebellion period who was silenced for being a Nonconformist.-Early years:He was born in St Ives, the son of William Tregosse...

, formerly vicar of Mylor and Mabe, Joseph Sherwood of Penzance, and Henry Flamank of Lanivet.

A number of prominent men holding Baptist views were to be found in Cornwall in the 1650s, such as John Pendarves

John Pendarves

-Life:The son of John Pendarves of Crowan in Cornwall, John Pendarves was born at Skewes in that parish. He was admitted a servitor of Exeter College, Oxford, on 11 December 1637. He matriculated on 9 February 1638, on the same day as his elder brother, Ralph Pendarves, and became a competent...

, John Carew and Hugh Courtney. At the restoration of the monarchy such people became dissenters and they were only found in a few settlements such as Falmouth and Looe. George Fox, the founder of the Quakers, visited Cornwall in 1655 and found followers in Loveday Hambly, of Tregongreeves near St Austell, and Thomas Mounce, of Liskeard. The early Cornish Quakers endured much persecution but after 1675 they made many converts. Once the opening of meeting houses became legal in 1689 their position became much easier and by 1700 there were altogether 27 societies with about 400 adherents. The most influential Cornish Quakers were the Foxes of Falmouth

Fox family of Falmouth

The Fox family of Falmouth, Cornwall, UK were very influential in the development of the town of Falmouth in the 19th century and of the Cornish Industrial Revolution...

.

The last church services conducted in Cornish

Cornish language

Cornish is a Brythonic Celtic language and a recognised minority language of the United Kingdom. Along with Welsh and Breton, it is directly descended from the ancient British language spoken throughout much of Britain before the English language came to dominate...

were in the far west (Penwith

Penwith

Penwith was a local government district in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom, whose council was based in Penzance. The district covered all of the Penwith peninsula, the toe-like promontory of land at the western end of Cornwall and which included an area of land to the east that fell outside the...

) in the late 17th century: Towednack

Towednack

Towednack is a village and civil parish in Cornwall, United Kingdom. The parish is bounded by those of Zennor in the west, Gulval in the south, Ludgvan in the east and St Ives in the north...

is recorded as the place (in 1678) and the claim is also made for Ludgvan

Ludgvan

Ludgvan is a civil parish and village in Cornwall, England, UK. The village is situated 2½ miles northeast of Penzance.The parish includes the villages of Ludgvan, Crowlas, Canon's Town and Long Rock...

.

1714 - 1800

- Remains to be written

The few Roman Catholics, Baptists and Quakers were now largely free of persecution. During the remainder of the 18th century Cornish Anglicanism was very much in the same state as Anglicanism in most of England. Wesleyan Methodist missions began during John Wesley's lifetime and had great success over a long period during which Methodism itself divided into a number of sects and established a definite separation from the Church of England.

19th and 20th centuries

From the early nineteenth to the mid-20th century MethodismMethodism

Methodism is a movement of Protestant Christianity represented by a number of denominations and organizations, claiming a total of approximately seventy million adherents worldwide. The movement traces its roots to John Wesley's evangelistic revival movement within Anglicanism. His younger brother...

was the leading form of Christianity in Cornwall but is now in decline. The Church of England was in the majority from the reign of Queen Elizabeth until the Methodist revival of the 19th century: before the Wesleyan missions dissenters were very few in Cornwall. The episcopate of Henry Phillpotts

Henry Phillpotts

Henry Phillpotts , often called "Henry of Exeter", was the Anglican Bishop of Exeter from 1830 to 1869. He was England's longest serving bishop since the 14th century and a striking figure of the 19th century Church.- Early life :...

(1830–1869) was a period of great Anglican activity with the establishment of many new parishes and parish churches and the first unsuccessful attempts to create a Cornish diocese. The county remained within the Diocese of Exeter

Diocese of Exeter

The Diocese of Exeter is a Church of England diocese covering the county of Devon. It is one of the largest dioceses in England. The Cathedral Church of Saint Peter in Exeter is the seat of the diocesan bishop, the Right Reverend Michael Langrish, Bishop of Exeter. It is part of the Province of...

until 1876 when the Anglican Diocese of Truro

Diocese of Truro

The Diocese of Truro is a Church of England diocese in the Province of Canterbury.-Geography and history:The diocese's area is that of the county of Cornwall including the Isles of Scilly. It was formed on 15 December 1876 from the Archdeaconry of Cornwall in the Diocese of Exeter, it is thus one...

was created (the first Bishop was appointed in 1877). Roman Catholicism was virtually extinct in Cornwall after the 17th century except for a few families such as the Arundells of Lanherne. From the mid-19th century the church reestablished episcopal sees in England, one of these being at Plymouth

Plymouth

Plymouth is a city and unitary authority area on the coast of Devon, England, about south-west of London. It is built between the mouths of the rivers Plym to the east and Tamar to the west, where they join Plymouth Sound...

. Since then immigration to Cornwall has brought more Roman Catholics into the population. Religious houses have been established at several locations including Bodmin, and Roman Catholic churches have been built where the need for them is apparent.

Other significant trends during the 20th century were the spread of Anglo-Catholicism

Anglo-Catholicism

The terms Anglo-Catholic and Anglo-Catholicism describe people, beliefs and practices within Anglicanism that affirm the Catholic, rather than Protestant, heritage and identity of the Anglican churches....

in Church of England parishes and the movement towards unification of the Anglican and Methodist Churches in the 1960s. As the bishops were sometimes High Church

High church

The term "High Church" refers to beliefs and practices of ecclesiology, liturgy and theology, generally with an emphasis on formality, and resistance to "modernization." Although used in connection with various Christian traditions, the term has traditionally been principally associated with the...

(e.g. W. H. Frere) and sometimes Low

Low church

Low church is a term of distinction in the Church of England or other Anglican churches initially designed to be pejorative. During the series of doctrinal and ecclesiastic challenges to the established church in the 16th and 17th centuries, commentators and others began to refer to those groups...

(e.g. Joseph Hunkin) administration of the diocese could vary from each episcopate to the next. The usage of Cornish as a liturgical language has become much more common.

The Cornish diaspora has contributed to the international spread of Methodism

Methodism

Methodism is a movement of Protestant Christianity represented by a number of denominations and organizations, claiming a total of approximately seventy million adherents worldwide. The movement traces its roots to John Wesley's evangelistic revival movement within Anglicanism. His younger brother...

, a movement within Protestant

Protestantism

Protestantism is one of the three major groupings within Christianity. It is a movement that began in Germany in the early 16th century as a reaction against medieval Roman Catholic doctrines and practices, especially in regards to salvation, justification, and ecclesiology.The doctrines of the...

Christianity that was popular with the Cornish people at the time of their mass migration.

Recent developments

Celtic Christianity

Celtic Christianity or Insular Christianity refers broadly to certain features of Christianity that were common, or held to be common, across the Celtic-speaking world during the Early Middle Ages...

. The group was founded by Andrew Phillips in 2006 and membership is open to baptised Christians in good standing in their local community who support the aims of the group.

In 2003, a campaign group was formed called Fry an Spyrys

Fry an Spyrys

Fry an Spyrys is a group based in Cornwall, UK, who are campaigning for the disestablishment of the Church of England there...

(Free the Spirit in Cornish). It is dedicated to disestablishing the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

in Cornwall and to forming an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion - a Church of Cornwall. Its chairman is Dr Garry Tregidga

Garry Tregidga

Garry Harcourt Tregidga is an academic at the Institute of Cornish Studies in the United Kingdom.-Academic career:Garry Tregidga undertook both his MPhil and PhD degrees with the University of Exeter. He was appointed as the Assistant Director of the Institute of Cornish Studies in October 1997...

of the Institute of Cornish Studies

Institute of Cornish Studies

The Institute of Cornish Studies is a research institute in west Cornwall: it started in 1970/71 as a research centre jointly funded by Exeter University and Cornwall County Council, with three core staff being employees of the University of Exeter...

. The Anglican Church was disestablished in Wales to form the Church in Wales

Church in Wales

The Church in Wales is the Anglican church in Wales, composed of six dioceses.As with the primus of the Scottish Episcopal Church, the Archbishop of Wales serves concurrently as one of the six diocesan bishops. The current archbishop is Barry Morgan, the Bishop of Llandaff.In contrast to the...

in 1920 and in Ireland to form the Church of Ireland

Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland is an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. The church operates in all parts of Ireland and is the second largest religious body on the island after the Roman Catholic Church...

in 1872.

Works in verse

Pascon agan ArluthEarly Cornish Texts

Specimens of Middle Cornish texts are given here in Cornish and English. Both texts have been dated within the period 1370-1410 and the Charter Fragment is given in two Cornish orthographies. -Background:The absorption of Cornwall within the Kingdom of England was not immediate...

(The Passion of our Lord), a poem of 259 eight-line verses probably composed around 1375, is one of the earliest surviving works of Cornish literature. The most important work of literature surviving from the Middle Cornish period is the Cornish Ordinalia

Ordinalia

The Ordinalia are three medieval mystery plays written in Cornish from the late fourteenth century. The three plays are Origo Mundi, , Passio Christi and Resurrexio Domini...

, a 9000-line religious verse drama

Drama

Drama is the specific mode of fiction represented in performance. The term comes from a Greek word meaning "action" , which is derived from "to do","to act" . The enactment of drama in theatre, performed by actors on a stage before an audience, presupposes collaborative modes of production and a...

which had probably reached its present form by 1400. The Ordinalia consists of three miracle plays, Origo Mundi, Passio Christi and Resurrexio Domini, meant to be performed on successive days. Such plays were performed in a 'Plain an Gwarry' (i.e. Playing Place).

The longest single surviving work of Cornish literature is Beunans Meriasek

Beunans Meriasek

Beunans Meriasek is a Cornish play completed in 1504. Its subject is the legends of the life of Saint Meriasek or Meriadoc, patron saint of Camborne, whose veneration was popular in Cornwall, Brittany, and elsewhere...

(The Life of Meriasek), a two-day verse drama dated 1504, but probably copied from an earlier manuscript. (This has been studied since the 1890s whereas the only other known Cornish drama portraying events in a saint's legend, Beunans Ke, was only found in the early years of the 21st century.)

Other notable pieces of Cornish literature include the Creation of the World (with Noah's Flood) which is a miracle play similar to Origo Mundi but in a much later manuscript (1611); the Charter Fragment, a short poem about marriage, believed to be the earliest connected text in the language; and the recently-discovered Beunans Ke, another saint's play, notable for containing a long Arthurian

King Arthur

King Arthur is a legendary British leader of the late 5th and early 6th centuries, who, according to Medieval histories and romances, led the defence of Britain against Saxon invaders in the early 6th century. The details of Arthur's story are mainly composed of folklore and literary invention, and...

section.

Works in prose

The earliest surviving examples of Cornish prose are the Tregear Homilies, a series of 12 Catholic sermonSermon

A sermon is an oration by a prophet or member of the clergy. Sermons address a Biblical, theological, religious, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law or behavior within both past and present contexts...

s written in English and translated by John Tregear around 1555-1557, to which a thirteenth homily The Sacrament of the Alter, was added by another hand. Twelve of Edmund Bonner

Edmund Bonner

Edmund Bonner , Bishop of London, was an English bishop. Initially an instrumental figure in the schism of Henry VIII from Rome, he was antagonized by the Protestant reforms introduced by Somerset and reconciled himself to Roman Catholicism...

's Homelies to be read within his diocese of London of all Parsons, vycars and curates (1555; nine of these were by John Harpsfield

John Harpsfield

-Life:Harpsfield was educated in Winchester College and New College, Oxford . He was perpetual fellow of New College from 1534 until 1551 and was appointed the first Regius Professor of Greek...

) were translated into Cornish by Tregear; they are the largest single work of traditional Cornish prose.

Church architecture and monuments

Celtic artCeltic art

Celtic art is the art associated with the peoples known as Celts; those who spoke the Celtic languages in Europe from pre-history through to the modern period, as well as the art of ancient peoples whose language is uncertain, but have cultural and stylistic similarities with speakers of Celtic...

is found in Cornwall, often in the form of Celtic cross

Celtic cross

A Celtic cross is a symbol that combines a cross with a ring surrounding the intersection. In the Celtic Christian world it was combined with the Christian cross and this design was often used for high crosses – a free-standing cross made of stone and often richly decorated...

es. Cornwall boasts the highest density of traditional 'Celtic crosses' of any nation. In modern times many crosses were erected as war memorials and to celebrate events such as the millennium

Millennium

A millennium is a period of time equal to one thousand years —from the Latin phrase , thousand, and , year—often but not necessarily related numerically to a particular dating system....

.

The church architecture of Cornwall and Devon typically differs from that of the rest of southern England: most medieval churches in the larger parishes were rebuilt in the later medieval period with one or two aisles and a western tower, the aisles being the same width as the nave and the piers of the arcades being of one of a few standard types. Wagon roofs often survive in these churches. The typical tower is of three stages, often with buttresses set back from the angles.

Churches of the Decorated period are relatively rare, as are those with spires. There are very few churches from the 17th and 18th centuries. There is a distinctive type of Norman font in many Cornish churches which is sometimes called the Altarnun type. The style of carving in benchends is also recognisably Cornish.

Church plate

Nearly 100 pieces of communion plate in Cornish churches were made in the Elizabethan period, that is between the years 1570 and 1577. Only one piece of pre-Reformation plate survives, an unremarkable paten at MorvalMorval, Cornwall

Morval is a rural civil parish and hamlet in south Cornwall, United Kingdom. The hamlet is approximately two miles north of Looe and five miles south of Liskeard....

dated 1528-29. Most of the Elizabethan pieces were made by Westcountry goldsmiths who include John Jons of Exeter (about 25). There are 47 pieces of communion plate from the Stuart period (up to 1685). 22 examples of flagons for the wine made in the 17th century still exist, and there are two at Minster dated 1588. At Kea is a French chalice and paten (1514 or 1537) donated by Susannah Haweis and at Antony three foreign chalices, two of these are Sienese of the 14th century and one is Flemish and dated 1582.

Biblical translations

There have also been BibleBible

The Bible refers to any one of the collections of the primary religious texts of Judaism and Christianity. There is no common version of the Bible, as the individual books , their contents and their order vary among denominations...

translations into Cornish. This redresses a perceived handicap unique to Cornish, in that of all the Celtic languages, it was only Cornish that did not have its own translation of the Bible.

- The first complete edition of the New Testament in Cornish, Nicholas WilliamsNicholas WilliamsNicholas Jonathan Anselm Williams , writing as Nicholas Williams or sometimes N.J.A...

's translation of the Testament Noweth agan Arluth ha Savyour Jesu Cryst, was published at Easter 2002 by Spyrys a Gernow (ISBN 0-9535975-4-7); it uses Unified Cornish Revised orthography. The translation was made from the Greek text, and incorporated John Tregear's existing translations with slight revisions. - In August 2004, Kesva an Taves Kernewek published its edition of the New Testament in Cornish (ISBN 1-902917-33-2), translated by Keith Syed and Ray Edwards; it uses Kernewek Kemmyn orthography. It was launched in a ceremony in Truro Cathedral attended by the Archbishop of Canterbury. A translation of the Old Testament is currently under preparation.

East Cornwall

After founding a monastery at Padstow Saint PetrocSaint Petroc

Saint Petroc is a 6th century Celtic Christian saint. He was born in Wales but primarily ministered to the Britons of Dumnonia which included the modern counties of Devon , Cornwall , and parts of Somerset and Dorset...

founded another monastery

Bodmin Parish Church

Bodmin Parish Church is an Anglican church in Bodmin, Cornwall, United Kingdom.The existing church building is dated 1469-72 and was until the building of Truro Cathedral the largest church in Cornwall...

in Bodmin

Bodmin

Bodmin is a civil parish and major town in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is situated in the centre of the county southwest of Bodmin Moor.The extent of the civil parish corresponds fairly closely to that of the town so is mostly urban in character...

in the 6th century and gave the town its alternative name of Petrockstow. The monastery was deprived of some of its lands at the Norman Conquest but at the time of Domesday still held 18 manors, including Bodmin, Padstow and Rialton. Bodmin is one of the oldest towns in Cornwall, and the only large Cornish settlement recorded in the Domesday Book

Domesday Book

Domesday Book , now held at The National Archives, Kew, Richmond upon Thames in South West London, is the record of the great survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086...

of the late 11th century. In the 15th century the Norman church of St Petroc was largely rebuilt and stands as one of the largest churches in Cornwall (the largest after the cathedral at Truro).

At Bodmin are remains from the substantial Franciscan Friary established ca. 1240: a gateway in Fore Street and two pillars elsewhere in the town. The Roman Catholic Abbey of St Mary and St Petroc was built in 1965 next to the already existing seminary.

St German's Priory

St German's Priory

St German's Priory is a large Norman church in the village of St Germans in south-east Cornwall, in the United Kingdom.-History:According to a credible tradition the church here was founded by St Germanus himself ca. 430 AD. The first written record however is of Conan being made Bishop in the...

was built over a Saxon building which was the cathedral of the Bishops of Cornwall

Bishop of Cornwall

The Bishop of Cornwall was an episcopal title which was used by Anglo Saxons between the 9th and 11th centuries. The bishop's seat was located at the village of St Germans, Cornwall. Later bishops of Cornwall were sometimes referred to as the bishops of St Germans...

. The monastery was reorganized by the Bishop of Exeter between 1161 and 1184 as an Augustinian priory and the new church was built on a grand scale, with two western towers and a nave of 102 ft.

Saint Petroc

Petroc

Petroc is a further education college in Devon, England, with a catchment area covering more than . It serves up to 20,000 students each year—including distance and work-based learners all over the UK—from entry level courses, through FE, higher education and beyond. The college employs...

founded monasteries at Padstow

Padstow

Padstow is a town, civil parish and fishing port on the north coast of Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The town is situated on the west bank of the River Camel estuary approximately five miles northwest of Wadebridge, ten miles northwest of Bodmin and ten miles northeast of Newquay...

and Bodmin: Padstow, which is named after him (Pedroc-stowe, or 'Petrock's Place'), appears to have been his base for some time before he moved to Bodmin. The monastery suffered raids from Viking pirates and the monks moved to Bodmin.

At St Stephens by Launceston the parish church, dedicated to St Stephen

Saint Stephen

Saint Stephen The Protomartyr , the protomartyr of Christianity, is venerated as a saint in the Roman Catholic, Anglican, Lutheran, Oriental Orthodox and Eastern Orthodox Churches....

, is on the northern outskirts of the town of Launceston. The church was built in the early 13th century after the monastery which had been on this site had moved into the valley near the castle

Launceston Castle

Launceston Castle is located in the town of Launceston, Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. .-Early history:The castle is a Norman motte and bailey earthwork castle raised by Robert, Count of Mortain, half-brother of William the Conqueror shortly after the Norman conquest, possibly as early as 1067...

. (The name of Launceston belonged originally to the monastery and town here, but was transferred to the town of Dunheved.)

It was formerly believed that a monastery existed on the site of Tintagel Castle

Tintagel Castle

Tintagel Castle is a medieval fortification located on the peninsula of Tintagel Island, adjacent to the village of Tintagel in Cornwall, United Kingdom. The site was possibly occupied in the Romano-British period, due to an array of artefacts dating to this period which have been found on the...

but modern discoveries have refuted this. There was however a pre-Conquest monastery at Minster

Forrabury and Minster parish churches

The parishes to which the Forrabury and Minster parish churches belong were united in 1779 to form Forrabury and Minster ecclesiastical parish, within Cornwall, England, UK. The main settlement in the parish is Boscastle....

near Boscastle.

At St Endellion the church is a rare example of a collegiate church not abolished at the Reformation.

West Cornwall and Scilly

At St BuryanSt Buryan

St Buryan is a civil parish and village in Cornwall, United Kingdom.The village of St Buryan is situated approximately five miles west of Penzance along the B3283 towards Land's End...

King Athelstan endowed the building of collegiate buildings and the establishment of one of the earliest monasteries in Cornwall, and this was subsequently enlarged and rededicated to the saint in 1238 by Bishop William Briwere

William Briwere

William Briwere was a medieval Bishop of Exeter.- Early life :Briwere was the nephew of William Brewer, a baron and political leader during King Henry III of England's minority. Nothing else is known of the younger Briwere's family or where he was educated...

. The collegiate establishment consisted of a dean and three prebendaries.

Glasney College

Glasney College

Glasney College was founded in 1265 at Penryn, Cornwall, by Bishop Bronescombe and was a centre of ecclesiastical power in medieval Cornwall and probably the best known and most important of Cornwall's religious institutions.-History:...

was founded at Penryn

Penryn, Cornwall

Penryn is a civil parish and town in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is situated on the Penryn River about one mile northwest of Falmouth...

, Cornwall

Cornwall

Cornwall is a unitary authority and ceremonial county of England, within the United Kingdom. It is bordered to the north and west by the Celtic Sea, to the south by the English Channel, and to the east by the county of Devon, over the River Tamar. Cornwall has a population of , and covers an area of...

in 1265 by Bishop Bronescombe

Walter Branscombe

Walter Branscombe was Bishop of Exeter from 1258 to 1280.-Life:...

and was the centre of ecclesiastical power in Cornwall's Middle Ages

Middle Ages

The Middle Ages is a periodization of European history from the 5th century to the 15th century. The Middle Ages follows the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 and precedes the Early Modern Era. It is the middle period of a three-period division of Western history: Classic, Medieval and Modern...

and probably the best known and most important of Cornwall's monastic institutions. Henry VIII's dissolution of the monasteries

Dissolution of the Monasteries

The Dissolution of the Monasteries, sometimes referred to as the Suppression of the Monasteries, was the set of administrative and legal processes between 1536 and 1541 by which Henry VIII disbanded monasteries, priories, convents and friaries in England, Wales and Ireland; appropriated their...

, between 1536 and 1545, signalled the end of the big Cornish priories but as a Chantry Church

Chantry

Chantry is the English term for a fund established to pay for a priest to celebrate sung Masses for a specified purpose, generally for the soul of the deceased donor. Chantries were endowed with lands given by donors, the income from which maintained the chantry priest...

, Glasney held on until 1548 when it suffered the same fate. The smashing and looting of Cornish colleges such as Glasney and Crantock

Crantock

Crantock is a coastal civil parish and a village in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The village is approximately two miles southwest of Newquay....

brought an end to the formal scholarship that had helped sustain the Cornish language and Cornish cultural identity.

St Mawgan

St Mawgan in Pydar is a civil parish in Cornwall, United Kingdom. The village of St Mawgan is situated four miles northeast of Newquay....

Lanherne House, mainly built in the 16th and 17th centuries, became a convent for Roman Catholic nuns from Belgium

Belgium

Belgium , officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a federal state in Western Europe. It is a founding member of the European Union and hosts the EU's headquarters, and those of several other major international organisations such as NATO.Belgium is also a member of, or affiliated to, many...

in 1794.

St Michael's Mount

St Michael's Mount

St Michael's Mount is a tidal island located off the Mount's Bay coast of Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is a civil parish and is united with the town of Marazion by a man-made causeway of granite setts, passable between mid-tide and low water....

may have been the site of a monastery in the 8th - early 11th centuries and Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor also known as St. Edward the Confessor , son of Æthelred the Unready and Emma of Normandy, was one of the last Anglo-Saxon kings of England and is usually regarded as the last king of the House of Wessex, ruling from 1042 to 1066....

gave it to the Norman

Normandy

Normandy is a geographical region corresponding to the former Duchy of Normandy. It is in France.The continental territory covers 30,627 km² and forms the preponderant part of Normandy and roughly 5% of the territory of France. It is divided for administrative purposes into two régions:...

abbey of Mont Saint Michel. It was a priory

Priory

A priory is a house of men or women under religious vows that is headed by a prior or prioress. Priories may be houses of mendicant friars or religious sisters , or monasteries of monks or nuns .The Benedictines and their offshoots , the Premonstratensians, and the...

of that abbey until the dissolution of the alien houses by Henry V

Henry V of England

Henry V was King of England from 1413 until his death at the age of 35 in 1422. He was the second monarch belonging to the House of Lancaster....

, when it was given to the abbess and Convent of Syon at Isleworth

Isleworth

Isleworth is a small town of Saxon origin sited within the London Borough of Hounslow in west London, England. It lies immediately east of the town of Hounslow and west of the River Thames and its tributary the River Crane. Isleworth's original area of settlement, alongside the Thames, is known as...

, Middlesex

Middlesex

Middlesex is one of the historic counties of England and the second smallest by area. The low-lying county contained the wealthy and politically independent City of London on its southern boundary and was dominated by it from a very early time...

. It was a resort of pilgrim

Pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a journey or search of great moral or spiritual significance. Typically, it is a journey to a shrine or other location of importance to a person's beliefs and faith...

s, whose devotions were encouraged by an indulgence granted by Pope Gregory

Pope Gregory VII

Pope St. Gregory VII , born Hildebrand of Sovana , was Pope from April 22, 1073, until his death. One of the great reforming popes, he is perhaps best known for the part he played in the Investiture Controversy, his dispute with Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor affirming the primacy of the papal...

in the 11th century. The monastic buildings were built during the 12th century but in 1425 as an alien monastery it was suppressed.

During Anglo-Saxon times the oratory site in Perranzabuloe

Perranzabuloe

Perranzabuloe is a coastal civil parish and a hamlet in Cornwall, United Kingdom. The hamlet is situated just over a mile south of the principal settlement of the parish, Perranporth; the hamlet is also seven miles south-southwest of Newquay...

was the site of an important monastery known as Lanpiran or Lamberran. It was disendowed ca. 1085 by Robert of Mortain. The later church preserved the relics of St Piran and was a major centre of pilgrimage: the relics are recorded in an inventory made in 1281 and were still venerated in the reign of Queen Mary I according to Nicholas Roscarrock's account. It is believed that Saint Piran founded the church near to Perranporth

Perranporth

Perranporth is a small seaside resort on the north coast of Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is southwest of Newquay and northwest of Truro. Perranporth and its long beach face the Atlantic Ocean....

(the "Lost Church") in the 7th century.

In early times the Isles of Scilly

Isles of Scilly

The Isles of Scilly form an archipelago off the southwestern tip of the Cornish peninsula of Great Britain. The islands have had a unitary authority council since 1890, and are separate from the Cornwall unitary authority, but some services are combined with Cornwall and the islands are still part...

were in the possession of a confederacy of hermits. King Henry I gave the hermits' territory to the abbey of Tavistock

Tavistock Abbey

Tavistock Abbey, also known as the Abbey of Saint Mary and Saint Rumon, is a ruined Benedictine abbey in Tavistock, Devon. Nothing remains of the abbey except the refectory, two gateways and a porch. The abbey church, dedicated to Our Lady and St Rumon, was destroyed by Danish raiders in 997 and...

, which established a priory on Tresco that was abolished at the Reformation.

In Truro

Truro

Truro is a city and civil parish in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The city is the centre for administration, leisure and retail in Cornwall, with a population recorded in the 2001 census of 17,431. Truro urban statistical area, which includes parts of surrounding parishes, has a 2001 census...

, Bishop Wilkinson founded a community of nuns, the Community of the Epiphany. George Wilkinson

George Wilkinson (bishop)

George Howard Wilkinson was Bishop of Truro and then of St Andrews, Dunkeld and Dunblane, in the last quarter of the 19th century and the early part of the 20th...

was afterwards Bishop of St Andrews. The sisters were involved in pastoral and educational work and the care of the cathedral.

Theological library

The Bishop Phillpotts Library in Truro, Cornwall, founded by Bishop Henry PhillpottsHenry Phillpotts

Henry Phillpotts , often called "Henry of Exeter", was the Anglican Bishop of Exeter from 1830 to 1869. He was England's longest serving bishop since the 14th century and a striking figure of the 19th century Church.- Early life :...

in 1856 for the benefit of the clergy of Cornwall, continues to be an important centre for theological and religious studies, with its more than 10,000 volumes, mainly theological, open to access by clergy and students of all denominations. It was opened in 1871 and almost doubled in size in 1872 by the bequest of the collection of Prebendary Ford.

Hagiography

- Baring-Gould, S.Sabine Baring-GouldThe Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould was an English hagiographer, antiquarian, novelist and eclectic scholar. His bibliography consists of more than 1240 publications, though this list continues to grow. His family home, Lew Trenchard Manor near Okehampton, Devon, has been preserved as he had it...

; Fisher, John (1907) Lives of the British Saints: the saints of Wales and Cornwall and such Irish saints as have dedications in Britain. 4 vols. London: For the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, by C. J. Clark, 1907–1913 - Borlase, W. C.William Copeland BorlaseWilliam Copeland Borlase FSA was an antiquarian and Liberal politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1880 until 1887 when he was ruined by bankruptcy and scandal....

(1895) The Age of Saints in Cornwall: early Christianity in Cornwall with legends of the Cornish saints. Truro: Joseph Pollard - Bowen, E. G. (1954) The Settlements of the Celtic Saints in Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press

- Lewis, H. A. (ca. 1939) Christ in Cornwall?: legends of St. Just-in-Roseland and other parts. Falmouth: J. H. Lake

- Rees, W. J. (ed.) (1853) Lives of the Cambro British Saints: of the fifth and immediate succeeding centuries, from ancient Welsh & Latin mss. in the British Museum and elsewhere, with English translations and explanatory notes. Llandovery: W. Rees

- Wade-Evans, A. W. (ed.) (1944). Vitae Sanctorum Britanniae et Genealogiae. Cardiff: University of Wales Press Board. (Lives of saints: Bernachius, Brynach. Beuno. Cadocus, Cadog. Carantocus (I and II), Carannog. David, Dewi sant. Gundleius, Gwynllyw. Iltutus, Illtud. Kebius, Cybi. Paternus, Padarn. Tatheus. Wenefred, Gwenfrewi.--Genealogies: De situ Brecheniauc. Cognacio Brychan. Ach Knyauc sant. Generatio st. Egweni. Progenies Keredic. Bonedd y saint.)

Church history

- Brown, H. Miles (1980) The Catholic Revival in Cornish Anglicanism: a study of the Tractarians of Cornwall 1833-1906. St Winnow: H. M. Brown

- Brown, H. Miles (1964) The Church in Cornwall. Truro: Blackford

- Henderson, Charles (1962) The Ecclesiastical History of Western Cornwall. 2 vols. Truro: Royal Institution of Cornwall; D. Bradford Barton, 1962

- Hingeston-Randolph, F. C., ed. Episcopal Registers: Diocese of Exeter. 10 vols. London: George Bell, 1886-1915 (for the period 1257 to 1455)

- Jenkin, A. K. HamiltonKenneth Hamilton JenkinAlfred Kenneth Hamilton Jenkin was best known as a historian with a particular interest in Cornish mining, publishing The Cornish Miner, now a classic, in 1927.-Birth and education:...

(1933) Cornwall and the Cornish: the story, religion and folk-lore of ’The Western Land’. London: J. M. Dent (chapter: The Coming of Wesley) - Oliver, George (1846) Monasticon Dioecesis Exoniensis: being a collection of records and instruments illustrating the ancient conventual, collegiate, and eleemosynary foundations, in the Counties of Cornwall and Devon, with historical notices, and a supplement, comprising a list of the dedications of churches in the Diocese, an amended edition of the taxation of Pope NicholasNicholas IVNicholas IV can refer to:* Pope Nicholas IV * Patriarch Nicholas IV of Constantinople * Patriarch Nicholas IV of Alexandria...

, and an abstract of the Chantry Rolls [with supplement and index]. Exeter: P. A. Hannaford, 1846, 1854, 1889 - Olson, Lynette (1989) Early Monasteries in Cornwall (Studies in Celtic History series). Woodbridge: Boydell Press ISBN 0-85115-478-6

- Orme, NicholasNicholas OrmeNicholas Orme is a British historian specialising in the Middle Ages and Tudor period, specialising in the history of children, and ecclesiastical history, with a particular interest in South West England....

(1996) English Church Dedications: with a survey of Cornwall and Devon. Exeter: University of Exeter Press ISBN 0859895165 - Orme, Nicholas (2007) Cornwall and the Cross: Christianity, 500-1560. Chichester: Phillimore in association with the Institute of Historical Research at the University of London ISBN 1860774687

- Orme, Nicholas, ed. (1991) Unity and Variety: a history of the church in Devon and Cornwall. Exeter: University of Exeter Press ISBN 0859893553 (A collection of essays examining the character of church life in Devon and Cornwall)

- Pearce, Susan M., ed. (1982) The Early Church in Western Britain and Ireland: studies presented to C. A. Ralegh Radford; arising from a conference organised in his honour by the Devon Archaeological Society and Exeter City Museum. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports

Antiquities and architecture

- Blight, John ThomasJohn Thomas BlightJohn Thomas Blight FSA was a Cornish archaeological artist born near Redruth in Cornwall.His father, Robert, a teacher, moved the family to Penzance and introduced his sons to the study of nature, antiquities and folk lore. John Blight was a natural draughtsman...

(1872) Ancient Crosses and Other Antiquities in the East of Cornwall 3rd ed. (1872) - Blight, John Thomas (1856) Ancient Crosses and Other Antiquities in the West of Cornwall (1856), 2nd edition 1858. (A reprint is offered online at Men-an-Tol Studios) (3rd ed. Penzance: W. Cornish, 1872) (facsimile ed. reproducing 1856 ed.: Blight's Cornish Crosses; Penzance : Oakmagic Publications, 1997)

- Brown, H. Miles (1973) What to Look for in Cornish Churches

- Langdon, Arthur G. (1896) Old Cornish Crosses. Truro: J. Pollard

- Okasha, Elisabeth (1993) Corpus of Early Christian Inscribed Stones of South-west Britain. Leicester: University Press

- Sedding, Edmund HEdmund Harold SeddingEdmund Harold Sedding was an English architect who practised in Devon and Cornwall. He was the son of Edmund Sedding and the nephew of J. D. Sedding. He was articled to his uncle, and initially employed by him, later setting up his own independent practice in Plymouth in 1891...

. (1909) Norman Architecture in Cornwall: a handbook to old ecclesiastical architecture. With over 160 plates. London: Ward & Co. - Straffon, Cheryl (1998) Fentynyow Kernow : in search of Cornwall's holy wells. Penzance: Meyn Mamvro ISBN 0-9518859-5-2