Religion in ancient Rome

Encyclopedia

Religion in ancient Rome encompassed the religious belief

s and cult practices regarded by the Romans

as indigenous and central to their identity as a people, as well as the various and many cults imported from other peoples brought under Roman rule. Romans thus offered cult to innumerable deities who influenced every aspect of both the natural world and human affairs. Their temples

were the visible, sacred, and enduring manifestations of Rome's history and institutions.

Romans could offer cult to any deity or combination of deities, as long as it did not offend the mos maiorum

, the "custom of the ancestors," that is, Roman tradition. Good relations between mortals and the divine (pax deorum

) were maintained by piety through the correct offering of ritual and divine honours, especially in the form of sacrifice. The gods were supposed to provide benefits in return. Impieties such as religious negligence, superstition and self-indulgence could provoke divine wrath against the State.

Participation in traditional religious rituals was considered a practical and moral necessity in personal, domestic and public life. Religion was not confined to particular occasions nor sacred places, but permeated daily life and every aspect of society. Cult within the Roman home was served by the head of household (the paterfamilias) and his familia, a broader term than the English word "family" that included his wife, children, slaves, and others under the protection of his household. Some deities were served by women, others by freedmen and slaves. The imported mystery cults

were open only to initiates.

Some of Rome's cult practices were explained or justified by myths

, while others remained obscure in origin and purpose. Latin literature

preserves theological and philosophical speculation on the nature of the divine and its relation to human affairs. Even the most skeptical among Rome's intellectual elite such as Cicero

, who was an augur

, acknowledged the necessity of religion as a form of social order despite its obvious irrational elements. Religious law offered curbs to personal and factional ambition, and political and social changes had to be justified in religious terms.

The establishment of Rome's oldest form of religion, sometimes known as the "religion of Numa

," was attributed to Rome's divine ancestors, founders, and kings. Ancient Rome had no principle equivalent to the separation of "church and state"

. The priesthoods and cult maintenance of major deities, as well as the highest offices of state

, were originally the preserve of the patricians, the hereditary elite whose privileges were said to have been charter

ed by the founding father Romulus

himself. Quite early in Roman history, however, most priesthoods were opened to plebeians

, along with political office. Some Romans, both patricians and noble plebeians

, claimed divine ancestry to justify their position among the ruling elite, most notably Julius Caesar

, who asserted his descent from the goddess Venus

.

After the civil wars

and social upheavals that led to the collapse of the Roman Republic

, Caesar's heir Augustus

carried out a program of religious revivalism designed to frame his ascent to sole power as a restoration of peace, tradition, and rectitude in accordance with divine will. The Augustan institution of Imperial cult

put pious respect for tradition on display, and aimed to foster religious unity and mutual toleration among Rome's newly acquired provinces. The preservation of the "religion of Numa" remained the foundation of Rome's security and continued success.

But as Rome had extended its dominance throughout the Mediterranean world, its religious mode was to absorb the deities and cults of other peoples rather than to eradicate and replace them. Both fascinated by and deeply suspicious of religious novelty, Romans looked for ways to understand and reinterpret the divinities of others by means of their own, and acknowledged religion in the provinces or foreign territories as an expression of local identity and traditions. Some religious practices were embraced officially, others merely tolerated. A few were condemned as alien hysteria, magic or superstition, and thus unwanted at Rome. Attempts, sometimes brutal, were made periodically to suppress religionists who seemed to threaten traditional morality and unity. In the eyes of conservative Romans, the Dionysian mysteries

encouraged illicit behaviour and subversion; Christianity

was superstition, or atheism, or both; druidism employed human sacrifice. The monotheistic rigor of Judaism

led sometimes to compromise and the granting of special exemptions, and sometimes to intractable conflict. By the height of the Roman Empire

, however, numerous foreign cults were practiced at Rome and throughout even the most remote provinces, among them the mystery cult of the syncretized

Egyptian goddess Isis

and deities of solar monism

such as Mithras and Sol Invictus

, found as far north as Roman Britain

.

From the 2nd century onward, the Church Fathers

began to condemn the diverse religions practiced throughout the Empire collectively as "pagan." When the Roman Emperor

Constantine I

converted to Christianity in the 4th century, he launched the era of Christian hegemony

. Despite a short-lived attempt by the Emperor Julian

to revive and preserve traditional and Hellenistic religion

and to affirm the special status of Judaism, in 391 under Theodosius I

Christianity became the official state religion of Rome

, to the exclusion of all others. Pleas for religious tolerance from traditionalists such as the senator

Symmachus

(d. 402) were rejected, and Christian monotheism became a feature of Imperial domination. Other religions were gradually transformed, absorbed or strictly suppressed. Many forms of traditional religious practice, particularly festivals

and games (ludi

), which might be divorced from theological implications, retained their vitality through the 4th and 5th centuries. Rome's religious hierarchy and many aspects of ritual influenced Christian forms, and many pre-Christian beliefs and practices survived in Christian festivals and local traditions.

The Roman mythological tradition

The Roman mythological tradition

is particularly rich in historical myths, or legend

s, concerning the foundation and rise of the city. These narratives focus on human actors, with only occasional intervention from deities but a pervasive sense of divinely ordered destiny. For Rome's earliest period, history and myth are difficult to distinguish.

Rome had a semi-divine ancestor in the Trojan

refugee Aeneas

, son of Venus

, who was said to have established the nucleus of Roman religion when he brought the Palladium

, Lares

and Penates from Troy to Italy. These objects were believed in historical times to remain in the keeping of the Vestals

, Rome's female priesthood. Aeneas had been given refuge by King Evander

, a Greek exile from Arcadia

, to whom were attributed other religious foundations: he established the Ara Maxima, "Greatest Altar," to Hercules

at the site that would become the Forum Boarium

, and he was the first to celebrate the Lupercalia

, an archaic festival in February that was celebrated as late as the 5th century of the Christian era.

The myth of a Trojan founding with Greek influence was reconciled through an elaborate genealogy (see Latin kings of Alba Longa

) with the well-known legend of Rome's founding by Romulus and Remus

. The most common version of the twins' story displays several aspects of hero myth. Their mother, Rhea Silvia

, had been ordered by her uncle the king to remain a virgin, in order to preserve the throne he had usurped from her father. Through divine intervention, the rightful line was restored when Rhea Silvia was impregnated by the god Mars

. She gave birth to twins, who were duly exposed by order of the king but saved through a series of miraculous events.

Romulus and Remus regained their grandfather's throne and set out to build a new city, consulting with the gods through augury, a characteristic religious institution of Rome that is portrayed as existing from earliest times. Divine communication did not prevent brotherly disagreement, and Romulus kills Remus, an act that is sometimes seen as sacrificial. Fratricide thus became an integral part of Rome's founding myth.

Romulus was credited with several religious institutions. He founded the Consualia

festival, inviting the neighbouring Sabines to participate; the ensuing rape of the Sabine women by Romulus's men further embedded both violence and cultural assimilation in Rome's myth of origins. As a successful general, Romulus is also supposed to have founded Rome's first temple to Jupiter Feretrius and offered the spolia opima

, the prime spoils taken in war, in the celebration of the first Roman triumph

. Romulus became increasingly autocratic, but in popular tradition was spared a normal human death and instead was mysteriously spirited away and deified.

His Sabine successor Numa

was pious and peaceable, and credited with numerous political and religious foundations, including the first Roman calendar

; the priesthoods of the Salii

, flamen

s, and Vestals; the cults of Jupiter

, Mars, and Quirinus

; and the Temple of Janus

, whose doors stayed open in times of war but in Numa's time remained closed. After Numa's death, the doors to the Temple of Janus remained open until the reign of Augustus, or so the claim went.

Each of Rome's legendary or semi-legendary kings was associated with one or more religious institutions still known to the later Republic. Tullus Hostilius

and Ancus Marcius

instituted the fetial

priests. The first "outsider" Etruscan king, Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, founded a Capitoline temple to the triad

Jupiter, Juno

and Minerva

which served as the model for the highest official cult throughout the Roman world. The benevolent, divinely fathered Servius Tullius

established the Latin League

, its Aventine

Temple to Diana

, and the Compitalia

to mark his social reforms. Servius Tullius was murdered and succeeded by the arrogant Tarquinius Superbus, whose expulsion marked the beginning of Rome as a republic with annually elected magistrates

.

The Roman historians

regarded the essentials of Republican religion as complete by the end of Numa's reign, and confirmed as right and lawful by the Senate and people of Rome

: the sacred topography of the city

, its monuments and temples, the histories of Rome's leading families

, and equally important oral and ritual traditions. Rome's history was represented as a coherent and sacred continuity, imperiled by religious negligence and personal ambition. According to Cicero, the Romans considered themselves the most religious of all peoples; and their extraordinary success proved it.

to explain the character of its deities, their mutual relationships or their interactions with the human world, but Roman theology acknowledged that di immortales (immortal gods) ruled all realms of the heavens and earth. There were gods of the upper heavens, gods of the underworld and a myriad of lesser deities between. Some evidently favoured Rome because Rome honoured them, but none were intrinsically, irredeemably foreign or alien. The political, cultural and religious coherence of an emergent Roman super-state required a broad, inclusive and flexible network of lawful cults. At different times and in different places, the sphere of influence, character and functions of a divine being could expand, overlap with those of others, and be redefined as Roman. Change was embedded within existing traditions.

Several versions of a semi-official, structured pantheon

were developed during the political, social and religious instability of the Late Republican era. Jupiter, the most powerful of all gods and "the fount of the auspices upon which the relationship of the city with the gods rested", consistently personified the divine authority of Rome's highest offices, internal organization and external relations. During the archaic and early Republican eras, he shared his temple

, some aspects of cult and several divine characteristics with Mars

and Quirinus

, who were later replaced by Juno

and Minerva

. A conceptual tendency toward triads may be indicated by the later agricultural or plebeian

triad of Ceres, Liber

and Libera

, and by some of the complementary threefold deity-groupings of Imperial cult. Other major and minor deities could be single, coupled, or linked retrospectively through myths of divine marriage and sexual adventure. These later Roman pantheistic

hierarchies are part literary and mythographic, part philosophical creations, and often Greek in origin. The Hellenization

of Latin literature and culture

supplied literary and artistic models for reinterpreting

Roman deities in light of the Greek Olympians

, and promoted a sense that the two cultures had a shared heritage.

The impressive, costly, and centralised rites to the deities of the Roman state were vastly outnumbered in everyday life by commonplace religious observances pertaining to an individual's domestic and personal deities, the patron divinities of Rome's various neighborhoods

and communities, and the often idiosyncratic blends of official, unofficial, local and personal cults that characterised lawful Roman religion. In this spirit, a provincial Roman citizen who made the long journey from Bordeaux

to Italy to consult the Sibyl at Tibur

did not neglect his devotion to his own goddess from home:

Roman calendars show roughly forty annual religious festivals. Some lasted several days, others a single day or less: sacred days (dies fasti) outnumbered "non-sacred" days (dies nefasti). A comparison of surviving Roman religious calendars suggests that official festivals were organized according to broad seasonal groups that allowed for different local traditions. Some of the most ancient and popular festivals incorporated ludi

Roman calendars show roughly forty annual religious festivals. Some lasted several days, others a single day or less: sacred days (dies fasti) outnumbered "non-sacred" days (dies nefasti). A comparison of surviving Roman religious calendars suggests that official festivals were organized according to broad seasonal groups that allowed for different local traditions. Some of the most ancient and popular festivals incorporated ludi

("games," such as chariot races and theatrical performances

), with examples including those held at Palestrina in honour of Fortuna Primigenia during Compitalia

, and the Ludi Romani

in honour of Liber

. Other festivals may have required only the presence and rites of their priests and acolytes, or particular groups, such as women at the Bona Dea

rites.

Other public festivals were not required by the calendar, but occasioned by events. The triumph

of a Roman general was celebrated as the fulfillment of religious vows

, though these tended to be overshadowed by the political and social significance of the event. During the late Republic, the political elite competed to outdo each other in public display, and the ludi attendant on a triumph were expanded to include gladiator contests. Under the Principate

, all such spectacular displays came under Imperial control: the most lavish were subsidised by emperors, and lesser events were provided by magistrates as a sacred duty and privilege of office. Additional festivals and games celebrated Imperial accessions and anniversaries. Others, such as the traditional Republican Secular Games

to mark a new era (saeculum), became imperially funded to maintain traditional values and a common Roman identity. That the spectacles retained something of their sacral aura even in late antiquity

is indicated by the admonitions of the Church Fathers that Christians should not take part.

The meaning and origin of many archaic festivals baffled even Rome's intellectual elite, but the more obscure they were, the greater the opportunity for reinvention and reinterpretation — a fact lost neither on Augustus in his program of religious reform, which often cloaked autocratic innovation, nor on his only rival as mythmaker of the era, Ovid

. In his Fasti

, a long-form poem covering Roman holidays from January to June, Ovid presents a unique look at Roman antiquarian

lore, popular customs, and religious practice that is by turns imaginative, entertaining, high-minded, and scurrilous; not a priestly account, despite the speaker's pose as a vates

or inspired poet-prophet, but a work of description, imagination and poetic etymology that reflects the broad humor and burlesque spirit of such venerable festivals as the Saturnalia

, Consualia

, and feast of Anna Perenna

on the Ides of March

, where Ovid treats the assassination of the newly deified Julius Caesar as utterly incidental to the festivities among the Roman people. But official calendars preserved from different times and places also show a flexibility in omitting or expanding events, indicating that there was no single static and authoritative calendar of required observances. In the later Empire under Christian rule, the new Christian festivals were incorporated into the existing framework of the Roman calendar, alongside at least some of the traditional festivals.

"The architecture of the ancient Romans was, from first to last, an art of shaping space around ritual." Roman religion was not confined to temples and shrines.

Temple buildings and shrines within the city commemorated significant political settlements in its development: the Aventine Temple of Diana supposedly marked the founding of the Latin League under Servius Tullius.

declared that "a sacrifice without prayer is thought to be useless and not a proper consultation of the gods." Prayer by itself, however, had independent power. The spoken word was thus the single most potent religious action, and knowledge of the correct verbal formulas the key to efficacy. Accurate naming was vital for tapping into the desired powers of the deity invoked, hence the proliferation of cult epithets among Roman deities. Public prayers were offered loudly and clearly by a priest on behalf of the community. Public religious ritual had to be enacted by specialists and professionals faultlessly; a mistake might require that the action, or even the entire festival, be repeated from the start. The historian Livy

reports an occasion when the presiding magistrate at the Latin festival forgot to include the "Roman people" among the list of beneficiaries in his prayer; the festival had to be started over. Even private prayer by an individual was formulaic, a recitation rather than a personal expression, though selected by the individual for a particular purpose or occasion.

Oaths of business, clientage and service, patronage and protection

, state office, treaty and loyalty appealed to the witness and sanction of deities. Refusal to swear a lawful oath, and a sworn oath broken carried much the same penalty; both repudiated the fundamental bonds between the human and divine.

Offerings to household deities

were part of daily life. Lares

might be offered spelt wheat and grain-garlands, grapes and first fruits in due season, honey cakes and honeycombs, wine and incense, food that fell to the floor during any family meal, or at their Compitalia

festival, honey-cakes and a pig on behalf of the community. Their supposed underworld relatives, the malicious and vagrant Lemures, might be placated with midnight offerings of black beans and spring water.

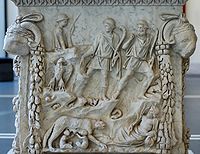

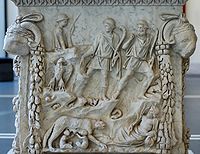

The most potent offering was animal sacrifice

, typically of domesticated animals such as cattle, sheep and pigs. Each was the best specimen of its kind, cleansed, clad in sacrificial regalia and garlanded; the horns of oxen might be gilded. Sacrifice sought the harmonisation of the earthly and divine, so the victim must seem willing to offer its own life on behalf of the community; it must remain calm and be quickly and cleanly despatched.

Sacrifice to deities of the heavens (di superi, "gods above") was performed in daylight, and under the public gaze. Deities of the upper heavens required white, infertile victims of their own sex: Juno

a white heifer (possibly a white cow); Jupiter

a white, castrated ox (bos mas) for the annual oath-taking by the consuls

. Di superi with strong connections to the earth, such as Mars, Janus, Neptune and various genii

– including the Emperor's – were offered fertile victims. After the sacrifice, a banquet was held; in state cults, the images of honoured deities took pride of place on banqueting couches and by means of the sacrificial fire consumed their proper portion (exta, the innards). Rome's officials and priests reclined in order of precedence alongside and ate the meat; lesser citizens may have had to provide their own.

Underworld (chthonic

) gods such as Dis pater

and the collective shades of the departed (di Manes

) were given dark, fertile victims in nighttime rituals; there was no shared banquet, as "the living cannot share a meal with the dead". Ceres

and other underworld goddesses of fruitfulness were sometimes offered pregnant female animals; Tellus was given a pregnant cow at the Fordicidia

festival. Color seems to have had a symbolic value generally for sacrifices. Demigods and heroes, who belonged to the heavens and the underworld, were sometimes given black-and-white victims. Robigo (or Robigus) was given red dogs and libations of red wine at the Robigalia

for the protection of crops from blight and red mildew.

Extraordinary circumstances called for extraordinary sacrifice: in one of the many crises of the Second Punic War

, Jupiter Capitolinus was promised every animal born that spring, to be rendered after five more years of protection from Hannibal and his allies. Had the gods failed to keep their side of the bargain, sacrifice would have been withheld. In the imperial period, sacrifice was withheld following Trajan

's death because the gods had not kept the Emperor safe for the stipulated period. In Pompeii

, the Genius of the living emperor was offered a bull: presumably a standard practise in Imperial cult, though minor offerings (incense and wine) were also made.

two Gauls and two Greeks were buried under the Forum Boarium

, in a stone chamber "which had on a previous occasion [228 BC] also been polluted by human victims, a practice most repulsive to Roman feelings". Livy avoids the word "sacrifice" in connection with this bloodless human life-offering; Plutarch does not. The rite was apparently repeated in 113 BC, preparatory to an invasion of Gaul. Its religious dimensions and purpose remain uncertain.

In the early stages of the First Punic War

(264 BC) the first known Roman gladiatorial munus

was held, described as a funeral blood-rite to the manes

of a Roman military aristocrat. The gladiator munus was never explicitly acknowledged as a human sacrifice, probably because death was not its inevitable outcome or purpose. Even so, the gladiators swore their lives to the infernal gods, and the combat was dedicated as an offering to the di manes or other gods. The event was therefore a sacrificium in the strict sense of the term, and Christian writers later condemned it as human sacrifice.

The small woolen dolls called Maniae, hung on the Compitalia shrines, were thought a symbolic replacement for child-sacrifice to Mania, as Mother of the Lares

. The Junii took credit for its abolition by their ancestor L. Junius Brutus

, traditionally Rome's Republican founder and first consul. Political or military executions were sometimes conducted in such a way that they evoked human sacrifice, whether deliberately or in the perception of witnesses; for a gruesome example, see Marcus Marius Gratidianus

.

Officially, human sacrifice was obnoxious "to the laws of gods and men." The practice was a mark of the "Other

", attributed to Rome's traditional enemies such as the Carthaginians and Gauls. Rome banned it on several occasions under extreme penalty, notably in 81 BC. Its alleged practice helped justify the conquest of Gaul and both invasions of Britain as righteous acts of war in suppression of the Druids, the elite priestly class among the Gauls: according to Pliny the Elder

, the British clung to the practice for as long as they could. Despite an empire-wide ban under Hadrian

, human sacrifice may have continued covertly in North Africa and elsewhere.

The mos maiorum established the dynastic authority and obligations of the citizen-paterfamilias ("the father of the family" or the "owner of the family estate"). He had priestly duties to his lares

The mos maiorum established the dynastic authority and obligations of the citizen-paterfamilias ("the father of the family" or the "owner of the family estate"). He had priestly duties to his lares

, domestic penates, ancestral Genius and any other deities with whom he or his family held an interdependent relationship. His own dependents, who included his slaves and freedmen, owed cult to his Genius

.

Genius was the essential spirit and generative power – depicted as a serpent or as a perennial youth, often winged – within an individual and their clan (gens

(pl. gentes). A paterfamilias could confer his name, a measure of his genius and a role in his household rites, obligations and honours upon those he fathered or adopted. His freed slaves owed him similar obligations.

A pater familias was the senior priest of his household. He offered daily cult to his lares and penates, and to his di parentes/divi parentes at his domestic shrines and in the fires of the household hearth. His wife (mater familias) was responsible for the household's cult to Vesta. In rural estates, bailiffs seem to have been responsible for at least some of the household shrines (lararia) and their deities. Household cults had state counterparts. In Vergil's Aeneid, Aeneas brought the Trojan cult of the lares

and penates from Troy, along with the Palladium

which was later installed in the temple of Vesta

.

(the customs and traditions "of the ancestors").

Religious law centered on the ritualised system of honours and sacrifice that brought divine blessings, according to the principle do ut des ("I give, that you might give"). Proper, respectful religio brought social harmony and prosperity. Religious neglect was a form of atheism

: impure sacrifice and incorrect ritual were vitia (impious errors). Excessive devotion, fearful grovelling to deities and the improper use or seeking of divine knowledge were superstitio. Any of these moral deviations could cause divine anger (ira deorum) and therefore harm the State. The official deities of the state were identified with its lawful offices and institutions, and Romans of every class were expected to honour the beneficence and protection of mortal and divine superiors. Participation in public rites showed a personal commitment to their community and its values.

Official cults were state funded as a "matter of public interest" (res publica

). Non-official but lawful cults were funded by private individuals for the benefit of their own communities. The difference between public and private cult is often unclear. Individuals or collegial associations could offer funds and cult to state deities. The public Vestals prepared ritual substances for use in public and private cults, and held the state-funded (thus public) opening ceremony for the Parentalia

festival, which was otherwise a private rite to household ancestors. Some rites of the domus (household) were held in public places but were legally defined as privata in part or whole. All cults were ultimately subject to the approval and regulation of the censor and pontifices.

Rome had no separate priestly caste or class. The highest authority within a community usually sponsored its cults and sacrifices, officiated as its priest and promoted its assistants and acolytes. Specialists from the religious colleges, and professionals such as haruspices and oracles were available for consultation. In household cult, the paterfamilias functioned as priest, and members of his familia as acolytes and assistants. Public cults required greater knowledge and expertise. The earliest public priesthoods were probably the flamines

Rome had no separate priestly caste or class. The highest authority within a community usually sponsored its cults and sacrifices, officiated as its priest and promoted its assistants and acolytes. Specialists from the religious colleges, and professionals such as haruspices and oracles were available for consultation. In household cult, the paterfamilias functioned as priest, and members of his familia as acolytes and assistants. Public cults required greater knowledge and expertise. The earliest public priesthoods were probably the flamines

(singular, flamen), attributed to king Numa: the major flamines, dedicated to Jupiter, Mars and Quirinus, and later, to Capitoline Jupiter, Juno and Minerva, were traditionally drawn from patrician families. Twelve lesser flamines were each dedicated to a single deity. Flamines were constrained by the requirements of ritual purity; Jupiter's flamen in particular had virtually no simultaneous capacity for a political or military career.

In the Regal era, a rex sacrorum

(king of the sacred rites) supervised regal and state rites in conjunction with the king (rex) or in his absence, and announced the public festivals. He had little or no civil authority. With the abolition of monarchy, the collegial power and influence of the Republican pontifices increased. By the late Republican era, the flamines were supervised by the pontifical collegia. The rex sacrorum had become a relatively obscure priesthood with an entirely symbolic title: his religious duties still included the daily, ritual announcement of festivals and priestly duties within two or three of the latter but his most important priestly role – the supervision of the Vestals and their rites – fell to the more politically powerful and influential pontifex maximus

.

Public priests were appointed by the collegia. Once elected, a priest held permanent religious authority from the eternal divine, which offered him lifetime influence, privilege and immunity. Therefore civil and religious law limited the number and kind of religious offices allowed an individual and his family. Religious law was collegial and traditional; it informed political decisions, could overturn them, and was difficult to exploit for personal gain. Priesthood was a costly honour: in traditional Roman practice, a priest drew no stipend. Cult donations were the property of the deity, whose priest must provide cult regardless of shortfalls in public funding – this could mean subsidy of acolytes and all other cult maintenance from personal funds. For those who had reached their goal in the Cursus honorum

, permanent priesthood was best sought or granted after a lifetime's service in military or political life, or preferably both: it was a particularly honourable and active form of retirement which fulfilled an essential public duty. For a freedman or slave, promotion as one of the Compitalia seviri offered a high local profile, and opportunities in local politics; and therefore business.

During the Imperial era, priesthood of the Imperial cult offered provincial elites full Roman citizenship and public prominence beyond their single year in religious office; in effect, it was the first step in a provincial cursus honorum. In Rome, the same Imperial cult role was performed by the Arval Brethren

, once an obscure Republican priesthood dedicated to several deities, then co-opted by Augustus as part of his religious reforms. The Arvals offered prayer and sacrifice to Roman state gods at various temples for the continued welfare of the Imperial family on their birthdays, accession anniversaries and to mark extraordinary events such as the quashing of conspiracy or revolt. Every January 3 they consecrated the annual vows and rendered any sacrifice promised in the previous year, provided the gods had kept the Imperial family safe for the contracted time.

The Vestals

The Vestals

were a public priesthood of six women devoted to the cultivation of Vesta

, goddess of the hearth of the Roman state and its vital flame

. A girl chosen to be a Vestal achieved unique religious distinction, public status and privileges, and could exercise considerable political influence. Upon entering her office, a Vestal was emancipated from her father's authority. In archaic Roman society, these priestesses were the only women not required to be under the legal guardianship of a man, instead answering directly to the Pontifex Maximus.

A Vestal's dress represented her status outside the usual categories that defined Roman women, with elements of both virgin bride and daughter, and Roman matron and wife. Unlike male priests, Vestals were freed of the traditional obligations of marrying and producing children, and were required to take a vow of chastity that was strictly enforced: a Vestal polluted by the loss of her chastity while in office was buried alive. Thus the exceptional honor accorded a Vestal was religious rather than personal or social; her privileges required her to be fully devoted to the performance of her duties, which were considered essential to the security of Rome.

The Vestals embody the profound connection between domestic cult and the religious life of the community. Any householder could rekindle their own household fire from Vesta's flame. The Vestals cared for the Lares

and Penates of the state that were the equivalent of those enshrined in each home. Besides their own festival of Vestalia, they participated directly in the rites of Parilia

, Parentalia

and Fordicidia

. Indirectly, they played a role in every official sacrifice; among their duties was the preparation of the mola salsa

, the salted flour that was sprinkled on every sacrificial victim as part of its immolation.

One mythological tradition held that the mother of Romulus and Remus was a Vestal virgin of royal blood. A tale of miraculous birth also attended on Servius Tullius

, sixth king of Rome, son of a virgin slave-girl impregnated by a disembodied phallus

arising mysteriously on the royal hearth; the story was connected to the fascinus

that was among the cult objects under the guardianship of the Vestals.

Augustus' religious reformations raised the funding and public profile of the Vestals. They were given high-status seating at games and theatres. The emperor Claudius

appointed them as priestesses to the cult of the deified Livia

, wife of Augustus. They seem to have retained their religious and social distinctions well into the 4th century, after political power within the Empire had shifted to the Christians. When the Christian emperor Gratian

refused the office of pontifex maximus, he took steps toward the dissolution of the order. His successor Theodosius I

extinguished Vesta's sacred fire and vacated her temple.

. The original meaning of the Latin word templum was this sacred space, and only later referred to a building. Rome itself was an intrinsically sacred space; its ancient boundary (pomerium

) had been marked by Romulus himself with oxen and plough; what lay within was the earthly home and protectorate of the gods of the state. In Rome, the central references for the establishment of an augural templum appear to have been the Via Sacra

(Sacred Way) and the pomerium. Magistrates sought divine opinion of proposed official acts through an augur, who read the divine will through observations made within the templum before, during and after an act of sacrifice. Divine disapproval could arise through unfit sacrifice, errant rites (vitium) or an unacceptable plan of action. If an unfavourable sign was given, the magistrate could repeat the sacrifice until favourable signs were seen, consult with his augural colleagues, or abandon the project. Magistrates could use their right of augury (ius augurum) to adjourn and overturn the process of law, but were obliged to base their decision on the augur's observations and advice. For Cicero, himself an augur, this made the augur the most powerful authority in the Late Republic. By his time (mid 1st century BC) augury was supervised by the college of pontifices, whose powers were increasingly woven into the magistracies of the cursus honorum

.

was also used in public cult, under the supervision of the augur or presiding magistrate. The haruspices divined the will of the gods through examination of entrails after sacrifice, particularly the liver. They also interpreted omens, prodigies and portents, and formulated their expiation. Most Roman authors describe haruspicy as an ancient, ethnically Etruscan "outsider" religious profession, separate from Rome's internal and largely unpaid priestly hierarchy, essential but never quite respectable. During the mid-to-late Republic, the reformist Gaius Gracchus

, the populist politician-general Gaius Marius

and his antagonist Sulla, and the "notorious Verres

" justified their very different policies by the divinely inspired utterances of private diviners. The senate and armies used the public haruspices: at some time during the late Republic, the Senate decreed that Roman boys of noble family be sent to Etruria for training in haruspicy and divination. Being of independent means, they would be better motivated to maintain a pure, religious practice for the public good. The motives of private haruspices – especially females – and their clients were officially suspect: none of this seems to have troubled Marius, who employed a Syrian prophetess.

Prodigies were transgressions in the natural, predictable order of the cosmos – signs of divine anger that portended conflict and misfortune. The Senate decided whether a reported prodigy was false, or genuine and in the public interest, in which case it was referred to the public priests, augurs and haruspices for ritual expiation. In 207 BC, during one of the Punic Wars' worst crises, the Senate dealt with an unprecedented number of confirmed prodigies whose expiation would have involved "at least twenty days" of dedicated rites.

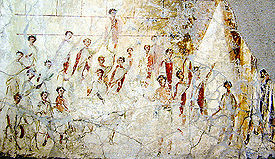

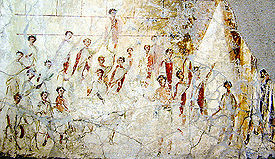

Livy presents these as signs of widespread failure in Roman religio. The major prodigies included the spontaneous combustion of weapons, the apparent shrinking of the sun's disc, two moons in a daylit sky, a cosmic battle between sun and moon, a rain of red-hot stones, a bloody sweat on statues, and blood in fountains and on ears of corn: all were expiated by sacrifice of "greater victims". The minor prodigies were less warlike but equally unnatural; sheep become goats, a hen become a cock (and vice-versa) – these were expiated with "lesser victims". The discovery of an androgynous four-year old child was expiated by its drowning and the holy procession of 27 virgins to the temple of Juno Regina, singing a hymn to avert disaster: a lightning strike during the hymn rehearsals required further expiation. Religious restitution is proved only by Rome's victory.

In the wider context of Graeco-Roman religious culture, Rome's earliest reported portents and prodigies stand out as atypically dire. Whereas for Romans, a comet presaged misfortune, for Greeks it might equally signal a divine or exceptionally fortunate birth. In the late Republic, a daytime comet at the murdered Julius Caesar's funeral games confirmed his deification; a discernable Greek influence on Roman interpretation.

Funeral and commemorative rites varied according to wealth, status and religious context. In Cicero's time, the better-off sacrificed a sow at the funeral pyre before cremation. The dead consumed their portion in the flames of the pyre, Ceres her portion through the flame of her altar, and the family at the site of the cremation. For the less well-off, inhumation with "a libation of wine, incense, and fruit or crops was sufficient". Ceres functioned as an intermediary between the realms of the living and the dead: the deceased had not yet fully passed to the world of the dead and could share a last meal with the living. The ashes (or body) were entombed or buried. On the eighth day of mourning, the family offered further sacrifice, this time on the ground; the shade of the departed was assumed to have passed entirely into the underworld. They had become one of the di Manes, who were collectively celebrated and appeased at the Parentalia

Funeral and commemorative rites varied according to wealth, status and religious context. In Cicero's time, the better-off sacrificed a sow at the funeral pyre before cremation. The dead consumed their portion in the flames of the pyre, Ceres her portion through the flame of her altar, and the family at the site of the cremation. For the less well-off, inhumation with "a libation of wine, incense, and fruit or crops was sufficient". Ceres functioned as an intermediary between the realms of the living and the dead: the deceased had not yet fully passed to the world of the dead and could share a last meal with the living. The ashes (or body) were entombed or buried. On the eighth day of mourning, the family offered further sacrifice, this time on the ground; the shade of the departed was assumed to have passed entirely into the underworld. They had become one of the di Manes, who were collectively celebrated and appeased at the Parentalia

, a multi-day festival of remembrance in February.

A standard Roman funerary inscription is Dis Manibus (to the Manes-gods). Regional variations include its Greek equivalent, theoîs katachthoníois and Lugdunum

's commonplace but mysterious "dedicated under the trowel" (sub ascia dedicare).

In the later Imperial era, the burial and commemorative practises of Christian and non-Christians overlapped. Tombs were shared by Christian and non-Christian family members, and the traditional funeral rites and feast of novemdialis found a part-match in the Christian Consitutio Apostolica. The customary offers of wine and food to the dead continued; St Augustine (following St Ambrose) feared that this invited the "drunken" practices of Parentalia but commended funeral feasts as a Christian opportunity to give alms of food to the poor. Christians attended Parentalia and its accompanying Feralia

and Caristia

in sufficient numbers for the Council of Tours

to forbid them in AD 567. Other funerary and commemorative practices were very different. Traditional Roman practice spurned the corpse as a ritual pollution; inscriptions noted the day of birth and duration of life. The Christian Church fostered the veneration of saintly relic

s, and inscriptions marked the day of death as a transition to "new life".

Roman commanders offered vows to be fulfilled after success in battle or siege; and further vows to expiate their failures. Camillus

promised Veii's goddess Juno a temple in Rome as incentive for her desertion, conquered the city in her name, brought her cult statue to Rome "with miraculous ease" and dedicated a temple to her on the Aventine Hill.

Roman camps followed a standard pattern for defense and religious ritual; in effect they were Rome in miniature. The commander's headquarters stood at the centre; he took the auspices on a dais in front. A small building behind housed the legionary standards, the divine images used in religious rites and in the Imperial era, the image of the ruling emperor. In one camp, this shrine is even called Capitolium. The most important camp-offering appears to have been the suovetaurilia performed before a major, set battle. A ram, a boar and a bull were ritually garlanded, led around the outer perimeter of the camp (a lustratio exercitus) and in through a gate, then sacrificed: Trajan's column shows three such events from his Dacian wars. The perimeter procession and sacrifice suggest the entire camp as a divine templum; all within are purified and protected.

Each camp had its own religious personnel; standard bearers, priestly officers and their assistants, including a haruspex, and housekeepers of shrines and images. A senior magistrate-commander (sometimes even a consul) headed it, his chain of subordinates ran it and a ferocious system of training and discipline ensured that every citizen-soldier knew his duty. As in Rome, whatever gods he served in his own time seem to have been his own business; legionary forts and vici included shrines to household gods, personal deities and deities otherwise unknown. From the earliest Imperial era, citizen legionaries and provincial auxiliaries gave cult to the emperor and his familia on Imperial accessions, anniversaries and their renewal of annual vows. They celebrated Rome's official festivals in absentia, and had the official triads appropriate to their function – in the Empire, Jupiter, Victoria

and Concordia

were typical. By the early Severan era, the military also offered cult to the Imperial divi, the current emperor's numen, genius and domus (or familia), and special cult to the Empress as "mother of the camp." The near ubiquitous legionary shrines to Mithras of the later Imperial era were not part of official cult until Mithras was absorbed into Solar

and Stoic Monism

as a focus of military concordia

and Imperial loyalty.

The devotio was the most extreme offering a Roman general could make, promising to offer his own life in battle along with the enemy as an offering to the underworld gods. Livy offers a detailed account of the devotio carried out by Decius Mus; family tradition maintained that his son and grandson, all bearing the same name, also devoted themselves. Before the battle, Decius is granted a prescient dream that reveals his fate. When he offers sacrifice, the victim's liver appears "damaged where it refers to his own fortunes". Otherwise, the haruspex tells him, the sacrifice is entirely acceptable to the gods. In a prayer recorded by Livy, Decius commits himself and the enemy to the dii Manes

and Tellus

, charges alone and headlong into the enemy ranks, and is killed; his action cleanses the sacrificial offering. Had he failed to die, his sacrificial offering would have been tainted and therefore void, with possibly disastrous consequences. The act of devotio is a link between military ethics and those of the Roman gladiator.

The efforts of military commanders to channel the divine will were on occasion less successful. In the early days of Rome's war against Carthage, the commander Publius Claudius Pulcher (consul 249 BC) launched a sea campaign "though the sacred chickens would not eat when he took the auspices." In defiance of the omen, he threw them into the sea, "saying that they might drink, since they would not eat. He was defeated, and on being bidden by the senate to appoint a dictator, he appointed his messenger Glycias, as if again making a jest of his country's peril." His impiety not only lost the battle but ruined his career.

Roman women were present at most festivals and cult observances. Some rituals specifically required the presence of women, but their active participation was limited. As a rule women did not perform animal sacrifice, the central rite of most major public ceremonies. In addition to the public priesthood of the Vestals, some cult practices were reserved for women only. The rites of the Bona Dea

excluded men entirely. Because women enter the public record less frequently than men, their religious practices are less known, and even family cults were headed by the paterfamilias. A host of deities, however, are associated with motherhood. Juno

, Diana

, Lucina, and specialized divine attendants presided over the life-threatening act of giving birth and the perils of caring for a baby at a time when the infant mortality rate was as high as 40 percent.

Literary sources vary in their depiction of women's religiosity: some represent women as paragons of Roman virtue and devotion, but also inclined by temperament to self-indulgent religious enthusiasms, novelties and the seductions of superstitio.

, in the sense of "doing or believing more than was necessary"; to which women and foreigners were considered particularly prone. The boundaries between religio and superstitio were negotiable.

"In vulgar tradition (more vulgari)...a magician is someone who, because of his community of speech with the immortal gods, has an incredible power of spells (vi cantaminum) for everything he wishes to." Apuleius, Apologia, 26.6.

Superstitio was often "seen to be motivated by an inappropriate desire for knowledge"; in effect, this was an abuse of religio. Secretive consultations between private diviners and their clients were suspect. So were divinatory techniques such as astrology when used for illicit, subversive or magical purposes. Astrologers and magicians were officially expelled from Rome at various times, notably in 139 BC and 33 BC. In 16 BC Tiberius expelled them under extreme penalty because an astrologer had predicted his death. "Egyptian rites" were particularly suspect: Augustus banned them within the pomerium to doubtful effect; Tiberius repeated and extended the ban with extreme force in AD 19. The Twelve Tables forbade any harmful incantation (Malum Carmen, or 'noisome metrical charm'); this included the "charming of crops from one field to another" (excantatio frugum) and any rite that sought harm or death to others. Despite several Imperial bans, magic and astrology persisted among all social classes. In the late 1st century AD, Tacitus could claim that astrologers "would always be banned and always retained at Rome".

In the Graeco-Roman world, practitioners of magic were known as magi

(s. magus) – a "foreign" title of Persian priests. Pliny the Elder

offers a thoroughly skeptical "History of magical arts" from their supposed Persian origins to the ill-fated emperor Nero's vast and futile expenditure on research into magical practices, in an attempt to control the gods. Lucan

's Pharsalia

has Pompey

's doomed and wretched son

await the battle of Pharsalus

. Convinced that "the gods of heaven knew too little" of the outcome; he resorts to the "disgusting" necromancy of Erichtho

, the Thessalian

witch who inhabits deserted graves and feeds on rotting corpses. She can arrest "the rotation of the heavens and the flow of rivers" and make "austere old men blaze with illicit passions"; an ideal, stereotypical witch – a female foreigner from Thessaly, notorious for its witchcraft and wizardry. She and her clients clearly undermine the natural order of gods, mankind and destiny. Philostratus

takes pains to point out that the celebrated Apollonius of Tyana

was definitely not a magician (magus) – "despite his special knowledge of the future, his miraculous cures, and his ability to vanish into thin air".

In the everyday world, many individuals sought to divine the future, influence it through magic, seek vengeance with help from "private" diviners; chthonic

deities functioned at the margins of Rome's divine and human communities, and the living might gain their favour and help – somewhat less dramatically than Lucan's Erictho, but usually away from the public gaze, during the hours of darkness. Burial grounds and isolated crossroads were among the likely portals, but Ovid gives a vivid account of what might be magical rites at the fringes of the public Feralia

festival: an old woman squats among a circle of younger women, sews up a fish-head, smears it with pitch, then pierces and roasts it to "bind hostile tongues to silence": she thus invokes Tacita, the underworld's "silent one". Archaeological evidence confirms the widespread use of so-called curse tablets (defixiones or "binding spells"), magical papyri and so-called "voodoo dolls" from a very early era. Around 250 defixiones have been recovered from urban and rural Britain; some seek straightforward, usually gruesome revenge, often for a lover's offense or rejection. Others appeal for divine redress of wrongs, in terms familiar to any Roman magistrate and promise a portion of the value of lost or stolen property in return for its restoration. In general, the values involved are quite low. None of these defixiones seem produced by, or on behalf of elite Romano-Britons; presumably, those without ready resort to human law and justice must hope to persuade the gods to act directly on their behalf. The archaeology suggests similar traditions throughout the empire, persisting until around the 7th century AD, well into the Christian era.

The links between religious and political life were vital to Rome's internal governance, diplomacy and development from kingdom, to Republic and to Empire. Post-regal politics dispersed the civil and religious authority of the kings more or less equitably among the patrician elite: kingship was replaced by two annually elected consular offices. In the early Republic, as presumably in the regal era, plebeians were excluded from high religious and civil office, and could be punished for offenses against laws of which they had no knowledge. They resorted to strikes and violence

to break the oppressive patrician monopolies of high office, public priesthood, and knowledge of civil and religious law. The senate appointed Camillus

as dictator

to handle the emergency; he negotiated a settlement, and sanctified it by the dedication of a temple to Concordia

. The religious calendars and laws

were eventually made public. Plebeian tribunes were appointed, with sacrosanct status and the right of veto in legislative debate. In principle, the augural and pontifical colleges were now open to plebians. In reality, the patrician and to a lesser extent, plebeian nobility dominated religious and civil office throughout the Republican era and beyond.

While the new plebeian nobility made social, political and religious inroads on traditionally patrician preserves, their electorate maintained their distinctive political traditions and religious cults. During the Punic crisis, popular cult to Dionysus

emerged from southern Italy; Dionysus was equated with Father Liber

, the inventor of plebeian augury and personification of plebeian freedoms, and with Roman Bacchus

. Official consternation at these enthusiastic, unofficial Bacchanalia

cults was expressed as moral outrage at their supposed subversion, and was followed by ferocious suppression. Much later, a statue of Marsyas, the silen

of Dionysus flayed by Apollo

, became a focus of brief symbolic resistance to Augustus' censorship. Augustus himself claimed the patronage of Venus and Apollo; but his settlement appealed to all classes. Where loyalty was implicit, no divine hierarchy need be politically enforced; Liber's festival

continued.

The Augustan settlement built upon a cultural shift in Roman society. In the middle Republican era, even Scipio

's tentative hints that he might be Jupiter's special protege sat ill with his colleagues. Politicians of the later Republic were less equivocal; both Sulla and Pompey

claimed special relationships with Venus

. Julius Caesar went further, and claimed her as his ancestress. Such claims suggested personal character and policy as divinely inspired; an appointment to priesthood offered divine validation. In 63 BC, Julius Caesar's appointment as pontifex maximus "signaled his emergence as a major player in Roman politics". Likewise, political candidates could sponsor temples, priesthoods and the immensely popular, spectacular public ludi and munera whose provision became increasingly indispensable to the factional politics of the Late Republic. Under the principate

, such opportunities were limited by law; priestly and political power were consolidated in the person of the princeps ("first citizen").

Rome had developed into a city-state, with a large plebeian, artisan class excluded from the old patrician gentes

and from the state priesthoods. The city had commercial and political treaties with its neighbours; according to tradition, Rome's Etruscan

connections established a temple to Minerva

on the predominantly plebeian Aventine

; she became part of a new Capitoline triad of Jupiter, Juno and Minerva, installed in a Capitoline temple, built in an Etruscan style and dedicated in a new September festival, Epulum Jovis

. These are supposedly the first Roman deities whose images were adorned, as if noble guests, at their own inaugural banquet.

Rome's diplomatic agreement with her neighbours of Latium

confirmed the Latin league

and brought the cult of Diana

from Aricia

to the Aventine. and established on the Aventine in the "commune Latinorum Dianae templum": At about the same time, the temple of Jupiter Latiaris was built on the Alban mount

, its stylistic resemblance to the new Capitoline temple pointing to Rome's inclusive hegemony. Rome's affinity to the Latins allowed two Latin cults within the pomoerium

: and the cult to Hercules

at the ara maxima

in the Forum Boarium

was established through commercial connections with Tibur. and the Tusculan

cult of Castor as the patron of cavalry found a home close to the Forum Romanum: Juno Sospes and Juno Regina were brought from Italy, and Fortuna Primigenia from Praeneste. In 217, Venus

was brought from Sicily and installed in a temple on the Capitoline hill.

were attributed, in Livy's account, to a growth of superstitious cults, errors in augury and the neglect of Rome's traditional gods, whose anger was expressed directly in Rome's defeat at Cannae

(216 BC). The Sibilline books were consulted. They recommended a general vowing of the ver sacrum and in the following year, the burial of two Greeks and two Gauls; not the first or the last of its kind, according to Livy.

The introduction of new or equivalent deities coincided with Rome's most significant aggressive and defensive military forays. In 206 BC the Sibylline books commended the introduction of cult to the aniconic Magna Mater (Great Mother) from Pessinus

, installed on the Palatine

in 191 BC. The mystery cult to Bacchus

followed; it was suppressed as subversive and unruly by decree of the Senate

in 186 BC. Greek deities were brought within the sacred pomerium: temples were dedicated to Juventas (Hebe

) in 191 BC, Diana

(Artemis

) in 179 BC, Mars

(Ares

) in 138 BC), and to Bona Dea

, equivalent to Fauna

, the female counterpart of the rural Faunus

, supplemented by the Greek goddess Damia

. Further Greek influences on cult images and types represented the Roman Penates as forms of the Greek Dioscuri. The military-political adventurers of the Later Republic introduced the Phrygian goddess Ma (identified with Roman Bellona

, the Egyptian mystery-goddess Isis

and Persian Mithras.

The spread of Greek literature, mythology and philosophy offered Roman poets and antiquarians a model for the interpretation of Rome's festivals and rituals, and the embellishment of its mythology. Ennius

translated the work of Graeco-Sicilian Euhemerus

, who explained the genesis of the gods as apotheosized

mortals. In the last century of the Republic, Epicurean

and particularly Stoic

interpretations were a preoccupation of the literate elite, most of whom held - or had held - high office and traditional Roman priesthoods; notably, Scaevola

and the polymath Varro

. For Varro - well versed in Euhemerus' theory - popular religious observance was based on a necessary fiction; what the people believed was not itself the truth, but their observance led them to as much higher truth as their limited capacity could deal with. Whereas in popular belief deities held power over mortal lives, the skeptic might say that mortal devotion had made gods of mortals, and these same gods were only sustained by devotion and cult.

Just as Rome itself claimed the favour of the gods, so did some individual Romans. In the mid-to-late Republican era, and probably much earlier, many of Rome's leading clans acknowledged a divine or semi-divine ancestor and laid personal claim to their favour and cult, along with a share of their divinity. Most notably in the very late Republic, the Julii claimed Venus Genetrix

as ancestor; this would be one of many foundations for the Imperial cult. The claim was further elaborated and justified in Vergil's poetic, Imperial vision of the past.

In the late Republic, the Marian

reforms lowered an existing property bar on conscription and increased the efficiency of Rome's armies but made them available as instruments of political ambition and factional conflict. The consequent civil wars led to changes at every level of Roman society. Augustus' principate

established peace and subtly transformed Rome's religious life – or, in the new ideology of Empire, restored it (see below).

Towards the end of the Republic, religious and political offices became more closely intertwined; the office of pontifex maximus

became a de facto consular prerogative. Augustus was personally vested with an extraordinary breadth of political, military and priestly powers; at first temporarily, then for his lifetime. He acquired or was granted an unprecedented number of Rome's major priesthoods, including that of ponifex maximus; as he invented none, he could claim them as traditional honours. His reforms were represented as adaptive, restorative and regulatory, rather than innovative; most notably his elevation (and membership) of the ancient Arvales

, his timely promotion of the plebeian Compitalia shortly before his election and his patronage of the Vestals as a visible restoration of Roman morality. Augustus obtained the pax deorum, maintained it for the rest of his reign and adopted a successor to ensure its continuation. This remained a primary religious and social duty of emperors.

built a Capitolium near its existing temple to Liber Pater and Serapis

. Autonomy and concord were official policy, but new foundations by Roman citizens or their Romanised allies were likely to follow Roman cultic models. Romanisation offered distinct political and practical advantages, especially to local elites. All the known effigies from the 2nd century AD forum at Cuicul are of emperors or Concordia

. By the middle of the 1st century AD, Gaulish Vertault

seems to have abandoned its native cultic sacrifice of horses and dogs in favour of a newly established, Romanised cult nearby: by the end of that century, Sabratha’s so-called tophet

was no longer in use. Colonial and later Imperial provincial dedications to Rome's Capitoline Triad were a logical choice, not a centralised legal requirement. Major cult centres to "non-Roman" deities continued to prosper: notable examples include the magnificent Alexandrian Serapium, the temple of Aesculapeus at Pergamum and Apollo's sacred wood at Antioch.

The overall scarcity of evidence for smaller or local cults does not always infer their neglect; votive inscriptions are inconsistently scattered throughout Rome's geography and history. Inscribed dedications were an expensive public declaration, one to be expected within the Graeco-Roman cultural ambit but by no means universal. Innumerable smaller, personal or more secretive cults would have persisted and left no trace.

Military settlement within the empire and at its borders broadened the context of Romanitas. Rome's citizen-soldiers set up altars to multiple deities, including their traditional gods, the Imperial genius and local deities – sometimes with the usefully open-ended dedication to the diis deabusque omnibus (all the gods and goddesses). They also brought Roman "domestic" deities and cult practices with them. By the same token, the later granting of citizenship to provincials and their conscription into the legions brought their new cults into the Roman military.

Traders, legions and other travellers brought home cults originating from Egypt, Greece, Iberia, India and Persia. The cults of Cybele

, Isis

, Mithras, and Sol Invictus

were particularly important. Some of those were initiatory religions of intense personal significance, similar to Christianity in those respects.

(lit. "first head of the Senate) was offered genius-cult as the symbolic paterfamilias of Rome. His cult had further precedents: popular, unofficial cult offered to powerful benefactors in Rome: the kingly, god-like honours granted a Roman general on the day of his triumph

; and in the divine honours paid to Roman magnates in the Greek East from at least 195 BC.

The deification of deceased emperors had precedent in Roman domestic cult to the dii parentes (deified ancestors) and the mythic apotheosis

of Rome's founders. A deceased emperor granted apotheosis by his successor and the Senate became an official State divus (divinity). Members of the Imperial family could be granted similar honours and cult; an Emperor's deceased wife, sister or daughter could be promoted to diva (female divinity).

The first and last Roman known as a living divus was Julius Caesar

, who seems to have aspired to divine monarchy; he was murdered soon after. Greek allies had their own traditional cults to rulers as divine benefactors, and offered similar cult to Caesar's successor, Augustus, who accepted with the cautious proviso that expatriate Roman citizens refrain from such worship; it might prove fatal. By the end of his reign, Augustus had appropriated Rome's political apparatus – and most of its religious cults – within his "reformed" and thoroughly integrated system of government. Towards the end of his life, he cautiously allowed cult to his numen. By then the Imperial cult apparatus was fully developed, first in the Eastern Provinces, then in the West. Provincial Cult centres offered the amenities and opportunities of a major Roman town within a local context; bathhouses, shrines and temples to Roman and local deities, amphitheatres and festivals. In the early Imperial period, the promotion of local elites to Imperial priesthood gave them Roman citizenship.

In an empire of great religious and cultural diversity, the Imperial cult offered a common Roman identity and dynastic stability. In Rome, the framework of government was recognisably Republican. In the Provinces, this would not have mattered; in Greece, the emperor was "not only endowed with special, super-human abilities, but... he was indeed a visible god" and the little Greek town of Akraiphia could offer official cult to "liberating Zeus Nero for all eternity".

In Rome, state cult to a living emperor acknowledged his rule as divinely approved and constitutional. As princeps

(first citizen) he must respect traditional Republican mores; given virtually monarchic powers, he must restrain them. He was not a living divus but father of his country (pater patriae), its pontifex maximus (greatest priest) and at least notionally, its leading Republican. When he died, his ascent to heaven, or his descent to join the dii manes was decided by a vote in the Senate. As a divus, he could receive much the same honours as any other state deity – libations of wine, garlands, incense, hymns and sacrificial oxen at games and festivals. What he did in return for these favours is unknown, but literary hints and the later adoption of divus as a title for Christian Saints suggest him as a heavenly intercessor. In Rome, official cult to a living emperor was directed to his genius; a small number refused this honour and there is no evidence of any emperor receiving more than that. In the crises leading up to the Dominate, Imperial titles and honours multiplied, reaching a peak under Diocletian. Emperors before him had attempted to guarantee traditional cults as the core of Roman identity and well-being; refusal of cult undermined the state and was treasonous.

had much in common with the overwhelmingly Hellenic or Hellenised communities that surrounded them. Early Italian synagogues have left few traces; but one was dedicated in Ostia around the mid-1st century BC and several more are attested during the Imperial period. Judaea's enrollment as a client kingdom in 63 BC increased the Jewish diaspora; in Rome, this led to closer official scrutiny of their religion. Their synagogues were recognised as legitimate collegia by Julius Caesar. By the Augustan era, the city of Rome was home to several thousand Jews. In some periods under Roman rule, Jews were legally exempt from official sacrifice, under certain conditions. Judaism was a superstitio to Cicero, but the Church Father Tertullian

described it as religio licita

(an officially permitted religion) in contrast to Christianity.

After the Great Fire of Rome

in 64 AD, Emperor Nero

accused the Christians as convenient scapegoats who were later persecuted and killed. From that point on, Roman official policy towards Christianity tended towards persecution. During the various Imperial crises of the 3rd century, “contemporaries were predisposed to decode any crisis in religious terms”, regardless of their allegiance to particular practices or belief systems. Christianity drew its traditional base of support from the powerless, who seemed to have no religious stake in the well-being of the Roman State, and therefore threatened its existence. The majority of Rome’s elite continued to observe various forms of inclusive Hellenistic monism; Neoplatonism in particular accommodated the miraculous and the ascetic within a traditional Graeco-Roman cultic framework. Christians saw these ungodly practices as a primary cause of economic and political crisis.

In the wake of religious riots in Egypt, the emperor Decius

decreed that all subjects of the Empire must actively seek to benefit the state through witnessed and certified sacrifice to "ancestral gods" or suffer a penalty: only Jews were exempt. Decius' edict appealed to whatever common mos maiores might reunite a politically and socially fractured Empire and its multitude of cults; no ancestral gods were specified by name. The fulfillment of sacrificial obligation by loyal subjects would define them and their gods as Roman. Roman oaths of loyalty were traditionally collective; the Decian oath has been interpreted as a design to root out individual subversives and suppress their cults, but apostasy

was sought, rather than capital punishment. A year after its due deadline, the edict expired.

Valerian

's first religious edict singled out Christianity as a particularly self-interested and subversive foreign cult, outlawed its assemblies and urged Christians to sacrifice to Rome's traditional gods. His second edict acknowledged a Christian threat to the Imperial system – not yet at its heart but close to it, among Rome’s equites and Senators. Christian apologists interpreted his disgraceful capture and death as divine judgement. The next forty years were peaceful; the Christian church grew stronger and its literature and theology gained a higher social and intellectual profile, due in part to its own search for political toleration and theological coherence. Origen

discussed theological issues with traditionalist elites in a common Neoplatonist frame of reference – he had written to Decius' predecessor Philip the Arab

in similar vein – and Hippolytus recognised a “pagan” basis in Christian heresies. The Christian churches were disunited; Paul of Samosata, Bishop of Antioch was deposed by a synod of 268 for "dogmatic reasons – his doctrine on the human nature of Christ was rejected – and for his lifestyle, which reminded his brethren of the habits of the administrative elite". The reasons for his deposition were widely circulated among the churches. Meanwhile Aurelian

(270-75) appealed for harmony among his soldiers (concordia militum), stabilised the Empire and its borders and successfully established an official, Hellenic form of unitary cult to the Palmyrene

Sol Invictus

in Rome's Campus Martius

.

In 295, a certain Maximilian refused military service; in 298 Marcellus

renounced his military oath. Both were executed for treason; both were Christians. At some time around 302, a report of ominous haruspicy in Diocletian

's domus and a subsequent (but undated) dictat of placatory sacrifice by the entire military triggered a series of edicts against Christianity. The first (303 AD) "ordered the destruction of church buildings and Christian texts, forbade services to be held, degraded officials who were Christians, re-enslaved imperial freedmen who were Christians, and reduced the legal rights of all Christians... [Physical] or capital punishments were not imposed on them" but soon after, several Christians suspected of attempted arson in the palace were executed. The second edict threatened Christian priests with imprisonment and the third offered them freedom if they performed sacrifice. An edict of 304 enjoined universal sacrifice to traditional gods, in terms that recall the Decian edict.

In some cases and in some places the edicts were strictly enforced: some Christians resisted and were imprisoned or martyred. Others complied. Some local communities were not only pre-dominantly Christian, but powerful and influential; and some provincial authorities were lenient. Diocletian's successor Galerius maintained anti-Christian policy until his deathbed revocation in 311, when he asked Christians to pray for him. "This meant an official recognition of their importance in the religious world of the Roman empire, although one of the tetrarchs, Maximinus Daia, still oppressed Christians in his part of the empire up to 313."

With the abatement of persecution, St. Jerome acknowledged Empire as a bulwark against evil but insisted that "imperial honours" were contrary to Christian teaching. His was an authoritative but minority voice: most Christians showed no qualms in the veneration of even "pagan" emperors. The peace of the emperors was the peace of God; as far as the Church was concerned, internal dissent and doctrinal schism were a far greater problem. The solution came from a hitherto unlikely source: as pontifex maximus Constantine I

favoured the "Catholic Church of the Christians" against the Donatists because:

Constantine successfully balanced his own role as an instrument of the pax deorum with the power of the Christian priesthoods in determining what was (in traditional Roman terms) auspicious - or in Christian terms, what was orthodox. The edict of Milan (313) redefined Imperial ideology as one of mutual toleration. Constantine had triumphed under the signum (sign) of the Christ: Christianity was therefore officially embraced along with traditional religions and from his new Eastern capital

, Constantine could be seen to embody both Christian and Hellenic religious interests. He may have officially ended – or attempted to end – blood sacrifices to the genius of living emperors but his Imperial iconography and court ceremonial outstripped Diocletian's in their supra-human elevation of the Imperial hierarch. His later direct intervention

in Church affairs proved a political masterstroke. Constantine united and re-founded the empire as an absolute head of state by divine dispensation and on his death, he was honoured as a Christian, Imperial and apostolic divus. Granted apotheosis, he ascended to heaven; Philostorgius

later criticised Christians who offered sacrifice at statues of the divus Constantine.

and Constans

, took over the leadership of the empire and re-divided their Imperial inheritance. Constantius was an Arian

and his brothers were Nicene Christians.

Constantine's nephew Julian

, however, rejected the "Galilean madness" of his upbringing for an idiosyncratic synthesis of neo-Platonism, Stoic asceticism and universal solar cult. Julian became Augustus in 361 and actively but vainly fostered a religious and cultural pluralism, attempting a restitution of non-Christian practices and rights. He proposed the rebuilding of Jerusalem's temple as an Imperial project and argued fulsomely against the "irrational impieties" of Christian doctrine. His attempt to restore an Augustan form of principate, with himself as primus inter pares

ended with his death in 363 in Persia, after which his reforms were reversed or abandoned. The empire once again fell under Christian control, this time permanently.

The Western emperor Gratian

refused the office of pontifex maximus, and against the protests of the senate, removed the altar of Victory

from the senate house and began the disestablishment of the Vestals. Theodosius I

briefly re-united the Empire: in 391 he officially adopted Nicene Christianity as the Imperial religion and ended official support for all other creeds and cults. He not only refused to restore Victory to the senate-house, but extinguished the Sacred fire of the Vestals and vacated their temple: the senatorial protest was expressed in a letter by Quintus Aurelius Symmachus

to the Western and Eastern emperors. Ambrose

, the influential Bishop of Milan and future saint, wrote on their behalf to reject Symmachus's request for tolerance. Yet Theodosius accepted comparison with Hercules and Jupiter as a living divinity in the panegyric of Pacatus, and despite his active dismantling of Rome's traditional cults and priesthoods could commend his heirs to its overwhelmingly Hellenic senate in traditional Hellenic terms. He was the last emperor of both East and West. When the Western Roman Empire ended with the abdication of Emperor Romulus Augustus

in 476, Christianity survived.

Religious belief