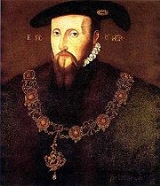

Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset

Encyclopedia

Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, 1st Earl of Hertford, 1st Viscount Beauchamp of Hache, KG

, Earl Marshal

(c. 1506 – 22 January 1552) was Lord Protector

of England

in the period between the death of Henry VIII

in 1547 and his own indictment in 1549.

. In 1514 he got an appointment in the household of Mary Tudor.

Edward's first marriage, about 1527, to Catherine Fillol

, was annulled; the reason is alleged to have been the discovery of a relationship between Catherine and Edward's father; however, this is disputed by the Dictionary of National Biography

. His second marriage was before 9 March 1534 to Anne Stanhope

.

Edward was the eldest brother of Jane Seymour

, who would become Henry VIII's third queen consort

. When Jane married the King in 1536, Seymour was created Viscount Beauchamp on 5 June, and on 15 October 1537 Earl of Hertford. He became Warden of the Scottish Marches

and continued in favour after his sister's death in 1537.

. Henry VIII's will

named sixteen executor

s, who were to act as Edward's Council until he reached the age of 18. These executors were supplemented by twelve men "of counsail" who would assist the executors when called on. The final state of Henry VIII's will has been the subject of controversy. Some historians suggest that those close to the king manipulated either him or the will itself to ensure a shareout of power to their benefit, both material and religious. In this reading, the composition of the Privy Chamber

shifted towards the end of 1546 in favour of the Protestant faction

. In addition, two leading conservative Privy Councillors were removed from the centre of power. Stephen Gardiner

was refused access to Henry during his last months. Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk

, found himself accused of treason

; the day before the king's death his vast estates were seized, making them available for redistribution, and he spent the whole of Edward's reign in the Tower of London

. Other historians have argued that Gardiner's exclusion was based on non-religious matters, that Norfolk was not noticeably conservative in religion, that conservatives remained on the Council, and that the radicalism of men such as Sir Anthony Denny

, who controlled the dry stamp that replicated the king's signature, is debatable. Whatever the case, Henry's death was followed by a lavish hand-out of lands and honours to the new power group. The will contained an "unfulfilled gifts" clause, added at the last minute, which allowed Henry's executors to freely distribute lands and honours to themselves and the court, particularly to Seymour, who became the Lord Protector of the Realm

and Governor of the King's Person, and who created himself Duke of Somerset

.

Henry VIII's will did not provide for the appointment of a Protector. It entrusted the government of the realm during his son's minority to a Regency Council that would rule collectively, by majority decision, with "like and equal charge". Nevertheless, a few days after Henry's death, on 4 February, the executors chose to invest almost regal power in the earl of Hertford. Thirteen out of the sixteen (the others being absent) agreed to his appointment as Protector, which they justified as their joint decision "by virtue of the authority" of Henry's will. Seymour may have done a deal with some of the executors, who almost all received hand-outs. He is known to have done so with William Paget

, private secretary to Henry VIII, and to have secured the support of Sir Anthony Browne

of the Privy Chamber.

Hertford's appointment was in keeping with historical precedent, and his eligibility for the role was reinforced by his military successes in Scotland and France. In March 1547, he secured letters patent

from King Edward granting him the almost monarchical right to appoint members to the Privy Council himself and to consult them only when he wished. In the words of historian G. R. Elton, "from that moment his autocratic system was complete". He proceeded to rule largely by proclamation

, calling on the Privy Council to do little more than rubber-stamp his decisions.

Somerset's takeover of power was smooth and efficient. The imperial ambassador

, Francis Van der Delft

, reported that he "governs everything absolutely", with Paget operating as his secretary, though he predicted trouble from John Dudley, Viscount Lisle

, who had recently been raised to Earl of Warwick

in the share-out of honours. In fact, in the early weeks of his Protectorate, Somerset was challenged only by the Chancellor, Thomas Wriothesley

, whom the Earldom of Southampton

had evidently failed to buy off, and by his own brother. Wriothesley, a religious conservative, objected to Somerset’s assumption of monarchical power over the Council. He then found himself abruptly dismissed from the chancellorship on charges of selling off some of his offices to delegates.

, who has been described as a "worm in the bud". As King Edward's uncle, Thomas Seymour demanded the governorship of the king’s person and a greater share of power. Somerset tried to buy his brother off with a baron

y, an appointment to the Lord Admiralship

, and a seat on the Privy Council—but Thomas was bent on scheming for power. He began smuggling pocket money to King Edward, telling him that Somerset held the purse strings too tight, making him a "beggarly king". He also urged him to throw off the Protector within two years and "bear rule as other kings do"; but Edward, schooled to defer to the Council, failed to co-operate.

In April 1547, using Edward’s support to circumvent Somerset’s opposition, Thomas Seymour secretly married Henry VIII's widow Catherine Parr

, whose Protestant household included the 11-year-old Lady Jane Grey

and the 13-year-old Princess Elizabeth

.

In summer 1548, a pregnant Catherine Parr discovered Thomas Seymour embracing Princess Elizabeth. As a result, Elizabeth was removed from Catherine Parr's household and transferred to Sir Anthony Denny's. That September, Catherine Parr died in childbirth, and Thomas Seymour promptly resumed his attentions to Elizabeth by letter, planning to marry her. Elizabeth was receptive, but, like Edward, unready to agree to anything unless permitted by the Council. In January 1549, the Council had Thomas Seymour arrested on various charges, including embezzlement

at the Bristol mint

. King Edward himself testified about the pocket money. Most importantly, Thomas Seymour had sought to officially receive the governorship of King Edward, as no earlier Lord Protectors, unlike Somerset, had ever held both functions. Lack of clear evidence for treason ruled out a trial, so Seymour was condemned instead by an Act of Attainder

and beheaded on 20 March 1549.

, and in the defence of Boulogne-sur-Mer

in 1546. From the first, his main interest as Protector was the war against Scotland. After a crushing victory at the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh

in September 1547, he set up a network of garrisons in Scotland, stretching as far north as Dundee

. His initial successes, however, were followed by a loss of direction, as his aim of uniting the realms through conquest became increasingly unrealistic. The Scots allied with France, who sent reinforcements for the defence of Edinburgh in 1548, while Mary, Queen of Scots was removed to France, where she was betrothed to the dauphin. The cost of maintaining the Protector's massive armies and his permanent garrisons in Scotland also placed an unsustainable burden on the royal finances. A French attack on Boulogne in August 1549 at last forced Somerset to begin a withdrawal from Scotland.

, arose mainly from the imposition of church services in English, and the second, led by a tradesman called Robert Kett

, mainly from the encroachment of landlords on common grazing ground. A complex aspect of the social unrest was that the protestors believed they were acting legitimately against enclosing

landlords with the Protector's support, convinced that the landlords were the lawbreakers.

The same justification for outbreaks of unrest was voiced throughout the country, not only in Norfolk and the west. The origin of the popular view of Somerset as sympathetic to the rebel cause lies partly in his series of sometimes liberal, often contradictory, proclamations, and partly in the uncoordinated activities of the commissions he sent out in 1548 and 1549 to investigate grievances about loss of tillage, encroachment of large sheep flocks on common land

, and similar issues. Somerset's commissions were led by the evangelical M.P. John Hales, whose socially liberal rhetoric linked the issue of enclosure with Reformation theology and the notion of a godly commonwealth

. Local groups often assumed that the findings of these commissions entitled them to act against offending landlords themselves. King Edward wrote in his Chronicle that the 1549 risings began "because certain commissions were sent down to pluck down enclosures".

Whatever the popular view of Somerset, the disastrous events of 1549 were taken as evidence of a colossal failure of government, and the Council laid the responsibility at the Protector's door. In July 1549, Paget wrote to Somerset: "Every man of the council have misliked your proceedings ... would to God, that, at the first stir you had followed the matter hotly, and caused justice to be ministered in solemn fashion to the terror of others ...".

. By 1 October, Somerset had been alerted that his rule faced a serious threat. He issued a proclamation calling for assistance, took possession of the king's person, and withdrew for safety to the fortified Windsor Castle

, where Edward wrote, "Me thinks I am in prison". Meanwhile, a united Council published details of Somerset's government mismanagement. They made clear that the Protector's power came from them, not from Henry VIII's will. On 11 October, the Council had Somerset arrested and brought the king to Richmond

. Edward summarised the charges against Somerset in his Chronicle: "ambition, vainglory, entering into rash wars in mine youth, negligent looking on Newhaven, enriching himself of my treasure, following his own opinion, and doing all by his own authority, etc." In February 1550, John Dudley, Earl of Warwick

, emerged as the leader of the Council and, in effect, as Somerset's successor. Although Somerset was released from the Tower and restored to the Council, he was executed for felony

in January 1552 after scheming to overthrow Dudley's regime. Edward noted his uncle's death in his Chronicle: "the duke of Somerset had his head cut off upon Tower Hill between eight and nine o'clock in the morning".

Historians contrast the efficiency of Somerset's takeover of power, in which they detect the organising skills of allies such as Paget, the "master of practices", with the subsequent ineptitude of his rule. By autumn 1549, his costly wars had lost momentum, the crown faced financial ruin, and riots and rebellions had broken out around the country. Until recent decades, Somerset's reputation with historians was high, in view of his many proclamations that appeared to back the common people against a rapacious landowning class. More recently, however, he has often been portrayed as an arrogant ruler, devoid of the political and administrative skills necessary for governing the Tudor state.

He was interred at St. Peter ad Vincula, Tower of London

.

Edward's suspicions about the fathering of Catherine Fillol's sons led him to have enacted in 1540, during his term as Lord Protector

, an Act of Parliament

entailing his estates away from the children of his first wife in preference of the children of Anne Seymour, his second wife

Together Edward and his second wife Anne had ten children. They were:

The Hertford/Somerset line of Edward and Anne died out with the seventh Duke of Somerset in 1750; the descendents of Edward Seymour by his first wife, Catherine Fillol, then inherited the Somerset dukedom in accordance with the original letters of patent.

Edward Seymour had, in total, four sons who bore the name "Edward;" one by his first wife, and three by his second wife. Of these four, the Edward of his first wife, and two of the Edwards of his second wife, survived him.

Order of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter, founded in 1348, is the highest order of chivalry, or knighthood, existing in England. The order is dedicated to the image and arms of St...

, Earl Marshal

Earl Marshal

Earl Marshal is a hereditary royal officeholder and chivalric title under the sovereign of the United Kingdom used in England...

(c. 1506 – 22 January 1552) was Lord Protector

Lord Protector

Lord Protector is a title used in British constitutional law for certain heads of state at different periods of history. It is also a particular title for the British Heads of State in respect to the established church...

of England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

in the period between the death of Henry VIII

Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII was King of England from 21 April 1509 until his death. He was Lord, and later King, of Ireland, as well as continuing the nominal claim by the English monarchs to the Kingdom of France...

in 1547 and his own indictment in 1549.

Early career

Edward Seymour was born in about 1506, to Sir John Seymour and Margery WentworthMargery Wentworth

Margery Wentworth, also known as Margaret Wentworth was the wife of Sir John Seymour and the mother of Queen Jane Seymour, the third wife of Henry VIII of England. She was the grandmother of King Edward VI of England.-Family:...

. In 1514 he got an appointment in the household of Mary Tudor.

Edward's first marriage, about 1527, to Catherine Fillol

Catherine Fillol

Catherine Fillol was the daughter and co-heiress of Sir William Fillol, of Woodlands, Horton, Dorset, and of Fillol's Hall, Essex ....

, was annulled; the reason is alleged to have been the discovery of a relationship between Catherine and Edward's father; however, this is disputed by the Dictionary of National Biography

Dictionary of National Biography

The Dictionary of National Biography is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published from 1885...

. His second marriage was before 9 March 1534 to Anne Stanhope

Anne Stanhope

Anne Seymour, Duchess of Somerset was the second wife of Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, who held the office of Lord Protector during the first part of the reign of his nephew King Edward VI, through whom Anne was briefly the most powerful woman in England...

.

Edward was the eldest brother of Jane Seymour

Jane Seymour

Jane Seymour was Queen of England as the third wife of King Henry VIII. She succeeded Anne Boleyn as queen consort following the latter's execution for trumped up charges of high treason, incest and adultery in May 1536. She died of postnatal complications less than two weeks after the birth of...

, who would become Henry VIII's third queen consort

Queen consort

A queen consort is the wife of a reigning king. A queen consort usually shares her husband's rank and holds the feminine equivalent of the king's monarchical titles. Historically, queens consort do not share the king regnant's political and military powers. Most queens in history were queens consort...

. When Jane married the King in 1536, Seymour was created Viscount Beauchamp on 5 June, and on 15 October 1537 Earl of Hertford. He became Warden of the Scottish Marches

Scottish Marches

Scottish Marches was the term used for the Anglo-Scottish border during the late medieval and early modern eras—from the late 13th century, with the creation by Edward I of England of the first Lord Warden of the Marches to the early 17th century and the creation of the Middle Shires, promulgated...

and continued in favour after his sister's death in 1537.

Council of Regency

Upon the death of Henry VIII, Seymour's nephew became king as Edward VIEdward VI of England

Edward VI was the King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death. He was crowned on 20 February at the age of nine. The son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour, Edward was the third monarch of the Tudor dynasty and England's first monarch who was raised as a Protestant...

. Henry VIII's will

Will (law)

A will or testament is a legal declaration by which a person, the testator, names one or more persons to manage his/her estate and provides for the transfer of his/her property at death...

named sixteen executor

Executor

An executor, in the broadest sense, is one who carries something out .-Overview:...

s, who were to act as Edward's Council until he reached the age of 18. These executors were supplemented by twelve men "of counsail" who would assist the executors when called on. The final state of Henry VIII's will has been the subject of controversy. Some historians suggest that those close to the king manipulated either him or the will itself to ensure a shareout of power to their benefit, both material and religious. In this reading, the composition of the Privy Chamber

Privy chamber

A Privy chamber was the private apartment of a royal residence in England. The gentlemen of the Privy chamber were servants to the Crown who would wait and attend on the King and Queen at court during their various activities, functions and entertainments....

shifted towards the end of 1546 in favour of the Protestant faction

Political faction

A political faction is a grouping of individuals, such as a political party, a trade union, or other group with a political purpose. A faction or political party may include fragmented sub-factions, “parties within a party," which may be referred to as power blocs, or voting blocs. The individuals...

. In addition, two leading conservative Privy Councillors were removed from the centre of power. Stephen Gardiner

Stephen Gardiner

Stephen Gardiner was an English Roman Catholic bishop and politician during the English Reformation period who served as Lord Chancellor during the reign of Queen Mary I of England.-Early life:...

was refused access to Henry during his last months. Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk

Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk

Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, KG, Earl Marshal was a prominent Tudor politician. He was uncle to Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard, two of the wives of King Henry VIII, and played a major role in the machinations behind these marriages...

, found himself accused of treason

Treason

In law, treason is the crime that covers some of the more extreme acts against one's sovereign or nation. Historically, treason also covered the murder of specific social superiors, such as the murder of a husband by his wife. Treason against the king was known as high treason and treason against a...

; the day before the king's death his vast estates were seized, making them available for redistribution, and he spent the whole of Edward's reign in the Tower of London

Tower of London

Her Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress, more commonly known as the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, separated from the eastern edge of the City of London by the open space...

. Other historians have argued that Gardiner's exclusion was based on non-religious matters, that Norfolk was not noticeably conservative in religion, that conservatives remained on the Council, and that the radicalism of men such as Sir Anthony Denny

Anthony Denny

Sir Anthony Denny was a confidant of Henry VIII of England. Denny was the most prominent member of the Privy chamber in Henry's last years having, together with his brother-in-law John Gates, charge of the "dry stamp" of Henry's signature, and attended Henry on his deathbed. He also served as...

, who controlled the dry stamp that replicated the king's signature, is debatable. Whatever the case, Henry's death was followed by a lavish hand-out of lands and honours to the new power group. The will contained an "unfulfilled gifts" clause, added at the last minute, which allowed Henry's executors to freely distribute lands and honours to themselves and the court, particularly to Seymour, who became the Lord Protector of the Realm

Lord Protector

Lord Protector is a title used in British constitutional law for certain heads of state at different periods of history. It is also a particular title for the British Heads of State in respect to the established church...

and Governor of the King's Person, and who created himself Duke of Somerset

Duke of Somerset

Duke of Somerset is a title in the peerage of England that has been created several times. Derived from Somerset, it is particularly associated with two families; the Beauforts who held the title from the creation of 1448 and the Seymours, from the creation of 1547 and in whose name the title is...

.

Henry VIII's will did not provide for the appointment of a Protector. It entrusted the government of the realm during his son's minority to a Regency Council that would rule collectively, by majority decision, with "like and equal charge". Nevertheless, a few days after Henry's death, on 4 February, the executors chose to invest almost regal power in the earl of Hertford. Thirteen out of the sixteen (the others being absent) agreed to his appointment as Protector, which they justified as their joint decision "by virtue of the authority" of Henry's will. Seymour may have done a deal with some of the executors, who almost all received hand-outs. He is known to have done so with William Paget

William Paget, 1st Baron Paget

William Paget, 1st Baron Paget of Beaudesert , was an English statesman and accountant who held prominent positions in the service of Henry VIII, Edward VI and Mary I.-Early life:...

, private secretary to Henry VIII, and to have secured the support of Sir Anthony Browne

Sir Anthony Browne (d.1548)

Sir Anthony Browne was an English courtier and Knight of the Shire.He was the son of Sir Anthony Browne, Standard Bearer of England and Governor of Queenborough Castle, by his wife Lucy Nevill, daughter of John Neville, 1st Marquess of Montagu and widow of Sir Thomas Fitzwilliam...

of the Privy Chamber.

Hertford's appointment was in keeping with historical precedent, and his eligibility for the role was reinforced by his military successes in Scotland and France. In March 1547, he secured letters patent

Letters patent

Letters patent are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch or president, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, title, or status to a person or corporation...

from King Edward granting him the almost monarchical right to appoint members to the Privy Council himself and to consult them only when he wished. In the words of historian G. R. Elton, "from that moment his autocratic system was complete". He proceeded to rule largely by proclamation

Proclamation

A proclamation is an official declaration.-England and Wales:In English law, a proclamation is a formal announcement , made under the great seal, of some matter which the King in Council or Queen in Council desires to make known to his or her subjects: e.g., the declaration of war, or state of...

, calling on the Privy Council to do little more than rubber-stamp his decisions.

Somerset's takeover of power was smooth and efficient. The imperial ambassador

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a realm that existed from 962 to 1806 in Central Europe.It was ruled by the Holy Roman Emperor. Its character changed during the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, when the power of the emperor gradually weakened in favour of the princes...

, Francis Van der Delft

Francis Van der Delft

François van der Delft , was Imperial ambassador to the court of Henry VIII of England from 1545 to 1550, when he was followed by Jehan de Scheyfye.Van der Delft came to England in 1545 to represent Charles V...

, reported that he "governs everything absolutely", with Paget operating as his secretary, though he predicted trouble from John Dudley, Viscount Lisle

John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland

John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland, KG was an English general, admiral, and politician, who led the government of the young King Edward VI from 1550 until 1553, and unsuccessfully tried to install Lady Jane Grey on the English throne after the King's death...

, who had recently been raised to Earl of Warwick

Earl of Warwick

Earl of Warwick is a title that has been created four times in British history and is one of the most prestigious titles in the peerages of the British Isles.-1088 creation:...

in the share-out of honours. In fact, in the early weeks of his Protectorate, Somerset was challenged only by the Chancellor, Thomas Wriothesley

Thomas Wriothesley, 1st Earl of Southampton

Thomas Wriothesley, 1st Earl of Southampton, KG , known as The Lord Wriothesley between 1544 and 1547, was a politician of the Tudor period born in London to William Wrythe and Agnes Drayton....

, whom the Earldom of Southampton

Earl of Southampton

Earl of Southampton was a title that was created three times in the Peerage of England. The first creation came in 1537 in favour of the courtier William Fitzwilliam. He was childless and the title became extinct on his death in 1542. The second creation came in 1547 in favour of the politician...

had evidently failed to buy off, and by his own brother. Wriothesley, a religious conservative, objected to Somerset’s assumption of monarchical power over the Council. He then found himself abruptly dismissed from the chancellorship on charges of selling off some of his offices to delegates.

Thomas Seymour

Somerset faced less manageable opposition from his younger brother ThomasThomas Seymour, 1st Baron Seymour of Sudeley

Thomas Seymour, 1st Baron Seymour of Sudeley, KG was an English politician.Thomas spent his childhood in Wulfhall, outside Savernake Forest, in Wiltshire. Historian David Starkey describes Thomas thus: 'tall, well-built and with a dashing beard and auburn hair, he was irresistible to women'...

, who has been described as a "worm in the bud". As King Edward's uncle, Thomas Seymour demanded the governorship of the king’s person and a greater share of power. Somerset tried to buy his brother off with a baron

Baron

Baron is a title of nobility. The word baron comes from Old French baron, itself from Old High German and Latin baro meaning " man, warrior"; it merged with cognate Old English beorn meaning "nobleman"...

y, an appointment to the Lord Admiralship

Admiralty

The Admiralty was formerly the authority in the Kingdom of England, and later in the United Kingdom, responsible for the command of the Royal Navy...

, and a seat on the Privy Council—but Thomas was bent on scheming for power. He began smuggling pocket money to King Edward, telling him that Somerset held the purse strings too tight, making him a "beggarly king". He also urged him to throw off the Protector within two years and "bear rule as other kings do"; but Edward, schooled to defer to the Council, failed to co-operate.

In April 1547, using Edward’s support to circumvent Somerset’s opposition, Thomas Seymour secretly married Henry VIII's widow Catherine Parr

Catherine Parr

Catherine Parr ; 1512 – 5 September 1548) was Queen consort of England and Ireland and the last of the six wives of King Henry VIII of England. She married Henry VIII on 12 July 1543. She was the fourth commoner Henry had taken as his consort, and outlived him...

, whose Protestant household included the 11-year-old Lady Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey , also known as The Nine Days' Queen, was an English noblewoman who was de facto monarch of England from 10 July until 19 July 1553 and was subsequently executed...

and the 13-year-old Princess Elizabeth

Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death. Sometimes called The Virgin Queen, Gloriana, or Good Queen Bess, Elizabeth was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty...

.

In summer 1548, a pregnant Catherine Parr discovered Thomas Seymour embracing Princess Elizabeth. As a result, Elizabeth was removed from Catherine Parr's household and transferred to Sir Anthony Denny's. That September, Catherine Parr died in childbirth, and Thomas Seymour promptly resumed his attentions to Elizabeth by letter, planning to marry her. Elizabeth was receptive, but, like Edward, unready to agree to anything unless permitted by the Council. In January 1549, the Council had Thomas Seymour arrested on various charges, including embezzlement

Embezzlement

Embezzlement is the act of dishonestly appropriating or secreting assets by one or more individuals to whom such assets have been entrusted....

at the Bristol mint

Mint (coin)

A mint is an industrial facility which manufactures coins for currency.The history of mints correlates closely with the history of coins. One difference is that the history of the mint is usually closely tied to the political situation of an era...

. King Edward himself testified about the pocket money. Most importantly, Thomas Seymour had sought to officially receive the governorship of King Edward, as no earlier Lord Protectors, unlike Somerset, had ever held both functions. Lack of clear evidence for treason ruled out a trial, so Seymour was condemned instead by an Act of Attainder

Bill of attainder

A bill of attainder is an act of a legislature declaring a person or group of persons guilty of some crime and punishing them without benefit of a judicial trial.-English law:...

and beheaded on 20 March 1549.

War

Somerset’s only undoubted skill was as a soldier, which he had proved on expeditions to Scotland, burning Edinburgh in May 1544Burning of Edinburgh (1544)

The Burning of Edinburgh in 1544 by an English sea-borne army was the first major action of the war of the Rough Wooing. A Scottish army observed the landing on 3 May 1544 but did not engage with the English force. The Provost of Edinburgh was compelled to allow the English to sack Leith and...

, and in the defence of Boulogne-sur-Mer

Boulogne-sur-Mer

-Road:* Metropolitan bus services are operated by the TCRB* Coach services to Calais and Dunkerque* A16 motorway-Rail:* The main railway station is Gare de Boulogne-Ville and located in the south of the city....

in 1546. From the first, his main interest as Protector was the war against Scotland. After a crushing victory at the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh

Battle of Pinkie Cleugh

The Battle of Pinkie Cleugh, on the banks of the River Esk near Musselburgh, Scotland on 10 September 1547, was part of the War of the Rough Wooing. It was the last pitched battle between Scottish and English armies, and is seen as the first modern battle in the British Isles...

in September 1547, he set up a network of garrisons in Scotland, stretching as far north as Dundee

Dundee

Dundee is the fourth-largest city in Scotland and the 39th most populous settlement in the United Kingdom. It lies within the eastern central Lowlands on the north bank of the Firth of Tay, which feeds into the North Sea...

. His initial successes, however, were followed by a loss of direction, as his aim of uniting the realms through conquest became increasingly unrealistic. The Scots allied with France, who sent reinforcements for the defence of Edinburgh in 1548, while Mary, Queen of Scots was removed to France, where she was betrothed to the dauphin. The cost of maintaining the Protector's massive armies and his permanent garrisons in Scotland also placed an unsustainable burden on the royal finances. A French attack on Boulogne in August 1549 at last forced Somerset to begin a withdrawal from Scotland.

Rebellion

During 1548, England was subject to social unrest. After April 1549, a series of armed revolts broke out, fuelled by various religious and agrarian grievances. The two most serious rebellions, which required major military intervention to put down, were in Devon and Cornwall and in Norfolk. The first, sometimes called the Prayer Book RebellionPrayer Book Rebellion

The Prayer Book Rebellion, Prayer Book Revolt, Prayer Book Rising, Western Rising or Western Rebellion was a popular revolt in Cornwall and Devon, in 1549. In 1549 the Book of Common Prayer, presenting the theology of the English Reformation, was introduced...

, arose mainly from the imposition of church services in English, and the second, led by a tradesman called Robert Kett

Kett's Rebellion

Kett's Rebellion was a revolt in Norfolk, England during the reign of Edward VI. The rebellion was in response to the enclosure of land. It began in July 1549 but was eventually crushed by forces loyal to the English crown....

, mainly from the encroachment of landlords on common grazing ground. A complex aspect of the social unrest was that the protestors believed they were acting legitimately against enclosing

Enclosure

Enclosure or inclosure is the process which ends traditional rights such as mowing meadows for hay, or grazing livestock on common land. Once enclosed, these uses of the land become restricted to the owner, and it ceases to be common land. In England and Wales the term is also used for the...

landlords with the Protector's support, convinced that the landlords were the lawbreakers.

The same justification for outbreaks of unrest was voiced throughout the country, not only in Norfolk and the west. The origin of the popular view of Somerset as sympathetic to the rebel cause lies partly in his series of sometimes liberal, often contradictory, proclamations, and partly in the uncoordinated activities of the commissions he sent out in 1548 and 1549 to investigate grievances about loss of tillage, encroachment of large sheep flocks on common land

Common land

Common land is land owned collectively or by one person, but over which other people have certain traditional rights, such as to allow their livestock to graze upon it, to collect firewood, or to cut turf for fuel...

, and similar issues. Somerset's commissions were led by the evangelical M.P. John Hales, whose socially liberal rhetoric linked the issue of enclosure with Reformation theology and the notion of a godly commonwealth

Commonwealth

Commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has sometimes been synonymous with "republic."More recently it has been used for fraternal associations of some sovereign nations...

. Local groups often assumed that the findings of these commissions entitled them to act against offending landlords themselves. King Edward wrote in his Chronicle that the 1549 risings began "because certain commissions were sent down to pluck down enclosures".

Whatever the popular view of Somerset, the disastrous events of 1549 were taken as evidence of a colossal failure of government, and the Council laid the responsibility at the Protector's door. In July 1549, Paget wrote to Somerset: "Every man of the council have misliked your proceedings ... would to God, that, at the first stir you had followed the matter hotly, and caused justice to be ministered in solemn fashion to the terror of others ...".

Fall of Somerset

The sequence of events that led to Somerset's removal from power has often been called a coup d'étatCoup d'état

A coup d'état state, literally: strike/blow of state)—also known as a coup, putsch, and overthrow—is the sudden, extrajudicial deposition of a government, usually by a small group of the existing state establishment—typically the military—to replace the deposed government with another body; either...

. By 1 October, Somerset had been alerted that his rule faced a serious threat. He issued a proclamation calling for assistance, took possession of the king's person, and withdrew for safety to the fortified Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a medieval castle and royal residence in Windsor in the English county of Berkshire, notable for its long association with the British royal family and its architecture. The original castle was built after the Norman invasion by William the Conqueror. Since the time of Henry I it...

, where Edward wrote, "Me thinks I am in prison". Meanwhile, a united Council published details of Somerset's government mismanagement. They made clear that the Protector's power came from them, not from Henry VIII's will. On 11 October, the Council had Somerset arrested and brought the king to Richmond

Richmond Palace

Richmond Palace was a Thameside royal residence on the right bank of the river, upstream of the Palace of Westminster, to which it lay 9 miles SW of as the crow flies. It it was erected c. 1501 within the royal manor of Sheen, by Henry VII of England, formerly known by his title Earl of Richmond,...

. Edward summarised the charges against Somerset in his Chronicle: "ambition, vainglory, entering into rash wars in mine youth, negligent looking on Newhaven, enriching himself of my treasure, following his own opinion, and doing all by his own authority, etc." In February 1550, John Dudley, Earl of Warwick

John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland

John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland, KG was an English general, admiral, and politician, who led the government of the young King Edward VI from 1550 until 1553, and unsuccessfully tried to install Lady Jane Grey on the English throne after the King's death...

, emerged as the leader of the Council and, in effect, as Somerset's successor. Although Somerset was released from the Tower and restored to the Council, he was executed for felony

Felony

A felony is a serious crime in the common law countries. The term originates from English common law where felonies were originally crimes which involved the confiscation of a convicted person's land and goods; other crimes were called misdemeanors...

in January 1552 after scheming to overthrow Dudley's regime. Edward noted his uncle's death in his Chronicle: "the duke of Somerset had his head cut off upon Tower Hill between eight and nine o'clock in the morning".

Historians contrast the efficiency of Somerset's takeover of power, in which they detect the organising skills of allies such as Paget, the "master of practices", with the subsequent ineptitude of his rule. By autumn 1549, his costly wars had lost momentum, the crown faced financial ruin, and riots and rebellions had broken out around the country. Until recent decades, Somerset's reputation with historians was high, in view of his many proclamations that appeared to back the common people against a rapacious landowning class. More recently, however, he has often been portrayed as an arrogant ruler, devoid of the political and administrative skills necessary for governing the Tudor state.

He was interred at St. Peter ad Vincula, Tower of London

Tower of London

Her Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress, more commonly known as the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, separated from the eastern edge of the City of London by the open space...

.

Ancestry

Descendants

Edward Seymour and his first wife Catherine Fillol had two sons:- John Seymour (1527 – 19 December 1552)

- Sir Edward Seymour, of Berry PomeroySir Edward Seymour, of Berry PomeroySir Edward Seymour, of Berry Pomeroy was High Sheriff of Devon for 1583. and was knighted by his father on the battlefield of Pinkie Cleugh....

, Devonshire, England (1529–1593)

Edward's suspicions about the fathering of Catherine Fillol's sons led him to have enacted in 1540, during his term as Lord Protector

Lord Protector

Lord Protector is a title used in British constitutional law for certain heads of state at different periods of history. It is also a particular title for the British Heads of State in respect to the established church...

, an Act of Parliament

Act of Parliament

An Act of Parliament is a statute enacted as primary legislation by a national or sub-national parliament. In the Republic of Ireland the term Act of the Oireachtas is used, and in the United States the term Act of Congress is used.In Commonwealth countries, the term is used both in a narrow...

entailing his estates away from the children of his first wife in preference of the children of Anne Seymour, his second wife

Together Edward and his second wife Anne had ten children. They were:

- Edward Seymour, Viscount Beauchamp of Hache (12 October 1537–1539)

- Edward Seymour, 1st Earl of HertfordEdward Seymour, 1st Earl of HertfordSir Edward Seymour, 1st Baron Beauchamp of Hache and 1st Earl of Hertford, KG was the son of Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, by his second wife Anne Stanhope....

(second creation of that title) (22 May 1539–1621), married firstly in November 1560, Lady Catherine GreyLady Catherine GreyLady Catherine Grey , Countess of Hertford, was the younger sister of Lady Jane Grey. A granddaughter of Henry VIII's sister Mary, she was a potential successor to her cousin, Queen Elizabeth I of England, but incurred Elizabeth's wrath by her secret marriage to Edward Seymour, 1st Earl of Hertford...

, by whom he had two sons; he married secondly in 1582, Frances Howard; and thirdly in 1601, Frances PrannellFrances Howard, Duchess of RichmondFrances Stewart, Duchess of Richmond and Lennox, née Howard was the daughter of a younger son of the Duke of Norfolk. An orphan of small fortune, she rose to be the only duchess at the court of James I of England. She married the son of a London alderman who died in 1599, leaving her a wealthy...

. - Lady Anne SeymourAnne Dudley, Countess of WarwickAnne Dudley Countess of Warwick was a writer during the sixteenth century in England, along with her sisters Lady Margaret Seymour and Lady Jane Seymour....

(1540–1588), married firstly John Dudley, 2nd Earl of WarwickJohn Dudley, 2nd Earl of WarwickJohn Dudley, 2nd Earl of Warwick, KG, KB was an English nobleman and the heir of John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland, leading minister and de facto ruler under Edward VI of England from 1550–1553. As his father's career progressed, John Dudley respectively assumed his father's former...

; she married secondly Sir Edward Unton, MPMember of ParliamentA Member of Parliament is a representative of the voters to a :parliament. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, the term applies specifically to members of the lower house, as upper houses often have a different title, such as senate, and thus also have different titles for its members,...

, by whom she had issue. - Lord Henry Seymour (1540–?) married Lady Joan Percy, daughter of Thomas Percy, 7th Earl of NorthumberlandThomas Percy, 7th Earl of NorthumberlandBlessed Thomas Percy, 7th Earl of Northumberland, 1st Baron Percy, KG , led the Rising of the North and was executed for treason. He was later beatified by the Catholic Church.-Early life:...

- Lady Margaret SeymourLady Margaret SeymourLady Margaret Seymour was an influential writer during the sixteenth century in England, along with her sisters, Anne Seymour, Countess of Warwick and Lady Jane Seymour. She was the daughter of Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, who from 1547 was the Lord Protector of England after the death of...

(1540 - ?) noted Elizabethan author - Lady Jane SeymourLady Jane SeymourLady Jane Seymour was an influential writer during the sixteenth century in England, along with her sisters, Lady Margaret Seymour and Anne Seymour, Countess of Warwick. She was the daughter of Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, who from 1547 was the Lord Protector of England after the death of...

(1541–1561) Maid of Honour to Queen Elizabeth I, noted Elizabethan author - Lady Catherine Seymour

- Lord Edward Seymour (1548–1574), unmarried and without issue

- Lady Mary Seymour (born 1552) married three times (Andrew Rogers, of Bryanstone, Dorset; Sir Henry Peyton; General Francis Cosbie)

- Lady Elizabeth Seymour (1552 – 3 June 1602), married Sir Richard Knightley, of NorthamptonshireNorthamptonshireNorthamptonshire is a landlocked county in the English East Midlands, with a population of 629,676 as at the 2001 census. It has boundaries with the ceremonial counties of Warwickshire to the west, Leicestershire and Rutland to the north, Cambridgeshire to the east, Bedfordshire to the south-east,...

The Hertford/Somerset line of Edward and Anne died out with the seventh Duke of Somerset in 1750; the descendents of Edward Seymour by his first wife, Catherine Fillol, then inherited the Somerset dukedom in accordance with the original letters of patent.

Edward Seymour had, in total, four sons who bore the name "Edward;" one by his first wife, and three by his second wife. Of these four, the Edward of his first wife, and two of the Edwards of his second wife, survived him.