John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland

Encyclopedia

John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland, KG (1504 – 22 August 1553) was an English general, admiral, and politician, who led the government of the young King Edward VI

from 1550 until 1553, and unsuccessfully tried to install Lady Jane Grey

on the English throne after the King's death. The son of Edmund Dudley

, a minister of Henry VII

executed by Henry VIII

, John Dudley became the ward

of Sir Edward Guildford

at the age of seven. He grew up in Guildford's household together with his future wife, Guildford's daughter Jane

, with whom he was to have 13 children. Dudley served as Vice-Admiral and Lord Admiral from 1537 until 1547, during which time he set novel standards of navy organization and was an innovative commander at sea. He also developed a strong interest in overseas exploration

. Dudley took part in the 1544 campaigns in Scotland and France and was one of Henry VIII's intimates in the last years of the reign. He was also a leader of the religious reform party at court.

In 1547 Dudley was created Earl of Warwick

and, with the Duke of Somerset

, England's Lord Protector

, distinguished himself in the renewed Scottish war

at the Battle of Pinkie. During the country-wide uprisings of 1549 Dudley put down Kett's Rebellion

in Norfolk

. Convinced of the Protector's incompetence, he and other privy councillors forced Somerset out of office in October 1549. Having averted a conservative reaction in religion and a plot to destroy him alongside Somerset, Dudley emerged in early 1550 as de facto

regent

for the 12-year-old Edward VI. He reconciled himself with Somerset, who nevertheless soon began to intrigue against him and his policies. Somerset was executed on largely fabricated charges, three months after Dudley had been raised to the Dukedom of Northumberland in October 1551.

As Lord President of the Council

, Dudley headed a distinctly conciliar

government and sought to introduce the adolescent King into business. Taking over an almost bankrupt administration, he ended the costly wars with France and Scotland and tackled finances in ways that led to some economic recovery. To prevent further uprisings he introduced countrywide policing on a local basis, appointing Lords Lieutenants

who were in close contact with the central authority. Dudley's religious policy was—in accordance with Edward's proclivities—decidedly Protestant, further enforcing the English Reformation

and promoting radical reformers to high Church positions.

The 15-year-old King fell ill in early 1553 and excluded his half-sisters Mary

and Elizabeth

, whom he regarded as illegitimate, from the succession, designating non-existent, hypothetical male heirs. As his death approached, Edward changed his will so that his Protestant cousin Jane Grey, Northumberland's daughter-in-law, could inherit the Crown. To what extent the Duke influenced this scheme is uncertain. The traditional view is that it was Northumberland's plot to maintain his power by placing his family on the throne. Many historians see the project as genuinely Edward's, enforced by Dudley after the King's death. The Duke did not prepare well for this occasion. Having marched to East Anglia

to capture Princess Mary, he surrendered on hearing that the Privy Council had changed sides and proclaimed Mary as Queen. Convicted of high treason

, Northumberland returned to Catholicism and abjured the Protestant faith before his execution. Having secured the contempt of both religious camps, popularly hated, and a natural scapegoat, he became the "wicked Duke"—in contrast to his predecessor Somerset, the "good Duke". Only since the 1970s has he also been seen as a Tudor Crown servant: self-serving, inherently loyal to the incumbent monarch, and an able statesman in difficult times.

, a councillor

of King Henry VII, and his second wife Elizabeth Grey, daughter of Edward Grey, 4th Viscount Lisle. His father was attainted and executed for high treason

in 1510, having been arrested immediately after Henry VIII

's accession because the new King needed scapegoats for his predecessor's unpopular financial policies. In 1512 the seven-year-old John became the ward

of Sir Edward Guildford and was taken into his household. At the same time Edmund Dudley's attainder was lifted and John Dudley was restored "in name and blood". The King was hoping for the good services "which the said John Dudley is likely to do". At about age 15 John Dudley probably went with his guardian to the Pale of Calais

to serve there for the next years. He took part in Cardinal Wolsey's diplomatic voyages of 1521 and 1527, and was knighted by Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk

during his first major military experience, the 1523 invasion of France. In 1524 Dudley became a Knight of the Body, a special mark of the King's favour, and from 1534 he was responsible for the King's body armour

as Master of the Tower Armoury. Being "the most skilful of his generation, both on foot and on horseback", he excelled in wrestling

, archery

, and the tournament

s of the royal court, as a French report stated as late as 1546.

In 1525 Dudley married Guildford's daughter Jane

, who was four years his junior and his former class-mate. The Dudleys belonged to the new evangelical

circles of the early 1530s, and their 13 children were educated in Renaissance humanism and science

. Sir Edward Guildford died in 1534 without a written will. His only son having predeceased him, Guildford's nephew, John Guildford

, asserted that his uncle had intended him to inherit. Dudley and his wife contested this claim. The parties went to court and Dudley, who had secured Thomas Cromwell's patronage

, won the case. In 1532 he lent his cousin, John Sutton, 3rd Baron Dudley

, over ₤

7,000 on the security of the baronial estate. Lord Dudley was unable to pay off any of his creditors, so when the mortgage was foreclosed in the late 1530s Sir John Dudley came into possession of Dudley Castle

.

Dudley was present at Henry VIII's meeting with Francis I of France

at Calais

in 1532. Another member of the entourage was Anne Boleyn

, who was soon to be queen. Dudley took part in the christenings of Princess Elizabeth and Prince Edward and, in connection with the announcement of the Prince's birth to the Emperor

, travelled to Spain via France in October 1537. He sat in the Reformation parliament in 1534–1536, and led one of the contingents sent against the Pilgrimage of Grace

in late 1536. In January 1537 Dudley was made Vice-Admiral and began to apply himself enthusiastically to naval matters. He was briefly Master of the Horse to Anne of Cleves

, and in 1542 was granted his grandfather's title of Viscount Lisle

—after the death of his stepfather Arthur Plantagenet and "by the right of his mother". Being now a peer

, Dudley became Lord Admiral and a Knight of the Garter in 1543; he was also admitted to the Privy Council

. In the aftermath of the Battle of Solway Moss

in 1542 he served as Warden of the Scottish Marches

, and in the 1544 campaign the English force under Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford

was supported by a fleet which Dudley commanded. Dudley joined the land force that destroyed Edinburgh

, after he had blown the main gate apart with a culverin

. In late 1544 he was appointed Governor of Boulogne, the siege of which had cost the life of his eldest son, Henry. His tasks were to rebuild the fortifications to King Henry's design and to fend off French attacks by sea and land.

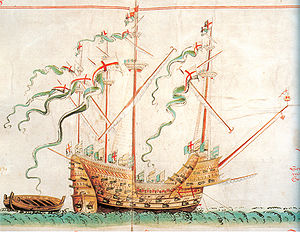

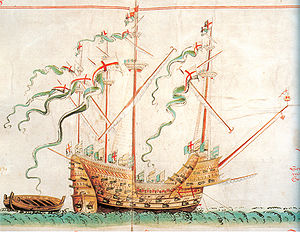

As Lord Admiral, Dudley was responsible for creating the Council for Marine Causes

As Lord Admiral, Dudley was responsible for creating the Council for Marine Causes

, which for the first time co-ordinated the various tasks of maintaining the navy functioning and thus made English naval administration the most efficient in Europe. At sea, Dudley's fighting orders were at the forefront of tactical

thinking: Squadrons of ships, ordered by size and firepower, were to manoeuvre in formation, using co-ordinated gunfire. These were all new developments in the English navy. In 1545 he directed the fleet's operations before, during, and after the Battle of the Solent

and entertained King Henry on the flagship Henri Grace a Dieu. A tragic loss was the sinking of the Mary Rose

with 500 men aboard. In 1546 John Dudley went to France for peace negotiations. When he suspected the Admiral of France

, Claude d'Annebault

, of manoeuvres which might have led to a renewal of hostilities, he suddenly put to sea in a show of English strength, before returning to the negotiating table. He then travelled to Fontainebleau

, where the English delegates were entertained by the Dauphin Henri

and King Francis. In the Peace of Camp, the French king acknowledged Henry VIII's title as "Supreme Head of the Church of England and Ireland", a success for both England and her Lord Admiral.

John Dudley, popularly fêted and highly regarded by King Henry as a general, became a royal intimate who played cards with the ailing monarch. Next to Edward Seymour, Prince Edward's maternal uncle, Dudley was one of the leaders of the Reformed party at court, and both their wives were among the friends of Anne Askew

, the Protestant martyr destroyed by Bishop Stephen Gardiner

in July 1546. Dudley and the Queen's brother, William Parr

, tried to convince Anne Askew to conform to the Catholic doctrines of the Henrician church, yet she replied "it was great shame for them to counsel contrary to their knowledge". In September Dudley struck Gardiner in the face during a full meeting of the Council. This was a grave offence, and he was lucky to escape with a month's leave from court in disgrace. In the last weeks of the reign Seymour and Dudley played their parts in Henry's strike against the conservative House of Howard

, thus clearing the path for a Protestant minority rule. They were seen as the likely leaders of the impending regency

—"there are no other nobles of a fit age and ability for the task", Eustache Chapuys, the former Imperial ambassador, commented from his retirement.

s of Henry VIII's will also embodied the Regency Council that had been appointed to rule collectively during Edward VI's minority. The new Council agreed on making Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford Lord Protector

with full powers, which in effect were those of a prince. At the same time the Council awarded themselves a round of promotions based on Henry VIII's wishes; the Earl of Hertford became the Duke of Somerset and John Dudley was created Earl of Warwick

. The new Earl had to pass on his post of Lord Admiral to Somerset's brother, Thomas Seymour

, but advanced to Lord Great Chamberlain

. Perceived as the most important man next the Protector, he was on friendly terms with Somerset, who soon reopened the war with Scotland. Dudley accompanied him as second-in-command with a taste for personal combat. On one occasion he fought his way out of an ambush and, spear in hand, chased his Scottish counterpart for some 250 yards, nearly running him through. In the Battle of Pinkie Dudley led the vanguard, being "one of the key architects of the English victory".

The Protector's agrarian policy and proclamations were inspired by a group of intellectuals sometimes called "the commonwealth men". These were highly critical of landlords and left many commoners with the impression that enclosure

s were unlawful. As one of England's major landowners, Dudley soon feared that this would lead to serious trouble and discreetly tried to warn Somerset. By the summer of 1549 there was widespread unrest or even rebellion all over England. The Marquess of Northampton

had been unable to restore order in and around Norwich

, so John Dudley was sent to get hold of Kett's Rebellion

. Dudley offered Robert Kett a pardon on the condition that the peasant army disband at once. This was rejected and the next night Dudley stormed the rebel-held city with a small mercenary

contingent and drove the rebels out after fierce street fighting; 49 prisoners he had immediately hanged. Two days later Kett, who had his main camp outside the city, confronted the royal army, resulting in a slaughter of over 2,000 peasants. In the following weeks Dudley concucted courts martial which executed many rebels, perhaps up to 300. For the enraged and humiliated local gentry

this was still not enough punishment, so Dudley warned them: "Is there no place for pardon? ... What shall we then do? Shall we hold the plough ourselves, play the carters and labour the ground with our own hands?"

The Lord Protector, in his proclamation

s, appealed to the common people. To his colleagues, whom he hardly consulted, he displayed a distinctly autocratic and "increasingly contemptuous" face. By autumn 1549 the same councillors who had made him Protector were convinced that he had failed to exercise proper authority and was unwilling to listen to good counsel. Dudley still had the troops from the Norfolk campaign at his disposal, and in October 1549 he joined the Earl of Southampton

and the Earl of Arundel, prominent religious conservatives, to lead a coup of councillors to oust the Protector from office. They withdrew from court to London, meeting in Dudley's residence. Starting with the Protector, each side issued proclamations accusing the other of treason and declared to act in defence of the King's safety. Somerset tried in vain to raise a popular force and entrenched himself with the King at the fortress Windsor Castle

. Military force near Edward's presence was unthinkable and, apparently, Dudley and Archbishop Cranmer

brokered an unofficial deal with Somerset, who surrendered. To keep appearances, the 12-year-old King personally commanded his uncle's arrest. For a moment there was hope of a conservative restoration in some quarters. However, Dudley and Cranmer secured the Reformed agenda by persuading Edward to appoint additional Reformed-minded members to the Council and Privy Chamber

. In December 1549 Southampton tried to regain predominance by charging Dudley with treason, alongside Somerset, for having been an original ally of the Protector. The scheme misfired when Dudley invited the Council to his house and baffled the plotters by exclaiming, with his hand at his sword and "a warlike visage": "my lord, you seek his [Somerset's] blood and he that seeketh his blood would have mine also".

Dudley consolidated his power through institutional manoeuvres and by January 1550 was in effect the new regent. On 2 February 1550 he became Lord President of the Council

, with the capacity to debar councillors from the body and appoint new ones. He excluded Southampton and other conservatives, but arranged Somerset's release and his return to the Privy Council and Privy Chamber. In June 1550 Dudley's heir John

married Somerset's daughter Anne

as a mark of reconciliation. Yet Somerset soon attracted political sympathizers and hoped to re-establish his power by removing Dudley from the scene, "contemplating", as he later admitted, the Lord President's arrest and execution. Relying on his popularity with the masses, he campaigned against and tried to obstruct Dudley's policies. His behaviour increasingly threatened the cohesion vital within a minority regime. In that respect Warwick would take no chances, and he now also aspired to a dukedom. He needed to advertise his power and impress his followers; like his predecessor, he had to represent the King's honour. His elevation as Duke of Northumberland

came in October 1551 with the Duke of Somerset participating in the ceremony. Some days later Somerset was arrested, while rumours about supposed plots of his circulated. He was accused of having planned a "banquet massacre", in which the Council were to be assaulted and Dudley killed. Somerset was acquitted of treason

but then, in January 1552, executed on charges of felony

for raising a contingent of armed men without a licence. While this was technically lawful, these events contributed much to Northumberland's growing unpopularity. Dudley himself, according to a French eyewitness, confessed before his own end that "nothing had pressed so injuriously upon his conscience as the fraudulent scheme against the Duke of Somerset".

Instead of taking the title of Lord Protector, John Dudley set out to rule as primus inter pares

Instead of taking the title of Lord Protector, John Dudley set out to rule as primus inter pares

. "[He] is absolute master here", Francis van der Delft

, Imperial ambassador, commented. Nevertheless, as the same and other ambassadors noted, the working atmosphere had markedly changed from autocratic to conciliar. The new Lord President of the Council reshuffled some high offices, becoming Grand Master of the Household

himself and giving Somerset's former office of Lord Treasurer to William Paulet, 1st Marquess of Winchester

. The office of Grand Master entailed supervising the Royal Household

, which gave Dudley the means to control the Privy Chamber and thus the King's surroundings. This was done via his "special friends" (as he called them), Sir John Gates

and Lord Thomas Darcy

. Dudley also placed his son-in-law Sir Henry Sidney and his brother Sir Andrew Dudley

near the King. William Cecil

was still in the Duke of Somerset's service when he gradually shifted his loyalty to John Dudley, who made him Secretary of State

and thought him "a most faithful servant and by that term most witty [wise] councillor ... as was scarce like in this realm". In this position Cecil was Dudley's trusted right hand, who primed the Privy Council according to the Lord President's wishes. At the same time Cecil had intimate contact with the King because Edward worked closely with the secretaries of state.

Dudley organized Edward's political education so that he should take an interest in affairs and at least appear to influence decisions. He wanted the King to grow into his authority as smoothly as possible. Disruptive conflicts when Edward took over government could thus be minimized, while Dudley's chances to continue as principal minister would be good. From the age of about 14 Edward's signature on documents no longer needed the Council's countersignatures, and the King was regularly debriefed in meetings with a Council of his own choosing—the principal administrators and the Duke of Northumberland were among the chosen. Dudley had a warm if respectful relationship with the teenager, who "loved and feared" him according to Jehan de Scheyfye, the Imperial ambassador. At a dinner Edward discussed with the envoy at length until Northumberland discreetly indicated to the King that he had said enough. Yet the Duke did not necessarily have his way in all things. In 1552–1553 the King's hand can be discerned behind decisions (and omissions) that directly contravened Dudley's wishes. At court, complex networks of influence were at work and Edward listened to more than one voice. Regarding the question to what extent Edward played a role in his own government, Stephen Alford writes:

s and alehouse talk, were generally disaffected to the men who ruled in the name of their king. Having inherited a failed government, Dudley set out to restore administrative efficiency and maintain public order to prevent renewed rebellion as seen in 1549. Equipped with a new law "for the punishment of unlawful assemblies", he built a united front of landholders and Privy Council, the government intervening locally at any sign of unrest. Dudley's methods were a mixture of old and new. He returned to the ancient practice of granting licences to retain

liveried

followers and installed Lord Lieutenant

s that represented the central government and were to keep ready small bands of cavalry

. These measures proved effective and the country was calm for the rest of the reign. In fact, in the summer of 1552—a year before the succession crisis—the cavalry bands were disbanded to save money and because they had never been actually needed.

In a more practical style than Somerset, John Dudley strove to alleviate the social situation. The 1547 "Act for the Punishment of Vagabonds", which had enacted that any unemployed man found loitering

was to be branded and given to the "presentor" as a slave, was abolished as too harsh in 1550. In 1552 Northumberland pushed a novel Poor Law

through parliament

which provided for weekly parish-based

collections for the "relief of the poor". Parishes were to register their needy inhabitants as well as the amounts people agreed to give for them, while unwilling contributors were to be "induced" by the parson and, if need be, by the bishop. The years 1549–1551 saw poor harvests and, accordingly, soaring food prices. Dudley tried to intervene against the "insatiable greediness" of middlemen

by searches for hidden corn and by fixing maximum prices for grain, meat, and other victuals. However, the set prices were so unrealisitic that farmers stopped to sell their produce at the open market and the regulations had to be rescinded. The regime's agrarian policy, while giving landlords much freedom to enclose common land, also distinguished between different forms of enclosure. Landlords guilty of illegal enclosures were increasingly prosecuted.

The financial legacy of the Protectorate consisted, apart from crippling Crown debts, of an unprecedentedly debased coinage. On the second day as Lord President of the Council, Dudley began a process to tackle the problems of the mint

; his declared aim was "to have his majesty out of debt". He set to work with Walter Mildmay

and Sir William Herbert, cracking down on peculation by the officers of the mint and other institutions. In 1551 they at the same time tried to yield profit and restore confidence in the coin by issuing yet further debased coinage and "crying it down" immediately afterwards. The result was panic and confusion and, to get hold of the situation, a coin of 92.3% silver content (against 25% silver content in the last debasement) was issued within months. The bad coin prevailed over the good, however, because people had lost confidence. Northumberland admitted to his colleagues that he found finance a puzzling and disagreeable thing, and told Lord Treasurer Winchester to find other experts to deal with it. Thomas Gresham

's services were called upon. After the first good harvest in four years, by late 1552 the currency was stable, prices for foodstuffs had dropped, and a basis for economic recovery had been laid. A process to centralize the administration of Crown revenue was underway and foreign debt had been eliminated.

became law in 1549. King Edward's half-sister, Mary Tudor

, de facto had licence to continue hearing mass

in private. So soon as he was in power, Dudley put pressure on her to stop the misuse of her privilege, as she allowed her entire household and flocks of visitors to attend. Mary, who in her turn did not tolerate the Book of Common Prayer in any of her residences, was not prepared to make any concessions. She planned to flee the country but then could not make up her mind in the last minute. Mary totally disregarded Edward's personal interest in the issue and fell into "an almost hysterical fear and hatred" of John Dudley. After a meeting with King and Council, in which she was told that the crux of the matter was not the nature of her faith but her disobedience to the law, she sent the Imperial ambassador de Scheyfye to threaten war on England. The English government could not swallow a war threat from an ambassador who had overstepped his commission, but at the same time would not risk all-important commercial ties with the Habsburg Netherlands

, so an embassy was sent to Brussels

and some of Mary's household officers were arrested. On his next visit to the Council de Scheyfye was informed by the Earl of Warwick that the King of England had as much authority at 14 as he had at 40—Dudley was alluding to Mary's refusal to accept Edward's demands on grounds of his young age. In the end a silent compromise came into effect: Mary continued to hear mass in a more private manner, while augmenting her landed property by exchanges with the Crown.

Appealing to the King's religious tastes, John Dudley became the chief backer of evangelical Protestants among the clergy, promoting several to bishopric

s—for example John Hooper

and John Ponet

. The English Reformation

went on apace, despite its widespread unpopularity. The 1552 revised edition of the Book of Common Prayer rejected the doctrine of transubstantiation

, and the Forty-two Articles

, issued in June 1553, proclaimed justification by faith and denied the existence of purgatory

. Despite these being cherished projects of Archbishop Thomas Cranmer

, he was displeased with the way the government handled their issue. By 1552 the relationship between the primate

and the Duke was icy. To prevent the Church from becoming independent of the state, Dudley was against Cranmer's reform of canon law

. He recruited the Scot John Knox

so that he should, in Northumberland's words, "be a whetstone to quicken and sharp the Bishop of Canterbury, whereof he hath need". Knox refused to collaborate, but joined fellow reformers in a concerted preaching campaign against covetous men in high places. Cranmer's canon law was finally wrecked by Northumberland's furious intervention during the spring parliament of 1553. On a personal level, though, the Duke was happy to help produce a schoolchildren's cathechism in Latin and English. In June 1553 he backed the Privy Council's invitation of Philip Melanchthon to become Regius Professor of Divinity

at Cambridge University. But for the King's death, Melanchthon would have come to England—his high travel costs had already been granted by Edward's government.

At the heart of Northumberland's problems with the episcopate lay the issue of the Church's wealth, from the confiscation of which the government and its officials had profited ever since the Dissolution of the Monasteries

. The most radical preachers thought that bishops, if needed at all, should be "unlorded". This attitude was attractive to Dudley, as it conveniently allowed him to fill up the Exchequer or distribute rewards with Church property. When new bishops were appointed—typically to the sees

of deprived conservative incumbents—they often had to surrender substantial land holdings to the Crown and were left with a much reduced income. The dire situation of the Crown finances made the Council resort to a further wave of Church expropriation in 1552–1553, targeting chantry

lands and Church plate. At the time and since, the break-up and reorganization of the Prince-Bishopric of Durham has been interpreted as Dudley's attempt to create himself a county palatine

of his own. However, as it turned out, Durham's entire revenue was allotted to the two successor bishoprics and the nearby border

garrison of Norham Castle

. Dudley received the stewardship

of the new "King's County Palatine" in the North (worth ₤50 p.a.), but there was no further gain for him. Overall, Northumberland's provisions for reorganized dioceses reveal a concern in him that "the preaching of the gospel" should not lack funds. Still, the confiscation of Church property as well as the lay

government's direction of Church affairs made the Duke disliked among clerics, whether Reformed or conservative. His relations with them were never worse than when the crisis of Edward's final illness approached.

English garrison at Boulogne. The high costs of the garrison could thus be saved and French payments of redemption of roughly ₤180,000 were a most welcome cash income. The peace with France was concluded in the Treaty of Boulogne in March 1550. There was both public rejoicing and anger at the time, and some historians have condemned the peace as a shameful surrender of English-held territory. A year later it was agreed that King Edward was to have a French bride, the six-year-old Elisabeth of Valois

. The threat of war with Scotland was also neutralized, England giving up some isolated garrisons in exchange. In the peace treaty with Scotland of June 1551, a joint commission, one of the first of its kind in history, was installed to agree upon the exact boundary

between the two countries. This matter was concluded in August 1552 by French arbitration. Despite the cessation of hostilities, English defences were kept on a high level: nearly ₤200,000 p.a. were spent on the navy and the garrisons at Calais and on the Scottish border. In his capacity as Warden-General of the Scottish Marches, Northumberland arranged for the building of a new Italianate

fortress at Berwick-upon-Tweed

.

The war between France and the Emperor broke out once again in September 1551. In due course Northumberland rejected requests for English help from both sides, which in the case of the Empire consisted of a demand for full-scale war based on an Anglo-Imperial treaty of 1542. The Duke pursued a policy of neutrality

, a balancing act that made peace between the two great powers attractive. In late 1552 he undertook to bring about a European peace by English mediation. These moves were taken seriously by the rival resident ambassadors, but were ended in June 1553 by the belligerents, the continuance of war being more advantageous to them.

in May 1550, yet never lost his keen interest in maritime affairs. Henry VIII had revolutionized the English navy, mainly in military terms. Dudley encouraged English voyages to far-off coasts, ignoring Spanish threats. He even contemplated a raid on Peru

with Sebastian Cabot

in 1551. Expeditions to Morocco and the Guinea coast

in 1551 and 1552 were actually realized. A planned voyage to China via the Northeast passage under Hugh Willoughby sailed in May 1553—King Edward watched their departure from his window. Northumberland was at the centre of a "maritime revolution", a policy in which, increasingly, the English Crown sponsored long-distance trade directly.

, the fervently Protestant daughter of the Duke of Suffolk and, through her mother Frances Brandon, a grandniece of Henry VIII. Her sister Catherine

was matched with the heir of the Earl of Pembroke, and another Katherine

, Guildford's younger sister, was promised to Henry Hastings

, heir of the Earl of Huntingdon

. Within a month the first of these marriages turned out to be highly significant. Although marked by magnificent festivities, at the time they took place the alliances were not seen as politically important, not even by the Imperial ambassador Jehan de Scheyfye, who was the most suspicious observer. Often perceived as proof of a conspiracy to bring the Dudley family to the throne, they have also been described as routine matches between aristocrats.

At some point during his illness Edward wrote a draft document headed "My devise for the Succession". Due to his ardent Protestantism Edward did not want his Catholic sister Mary to succeed, but he was also preoccupied with male succession and with legitimacy, which in Mary's and Elizabeth's case was questionable as a result of Henry VIII's legislation. In the first version of his "devise", written before he knew he was mortally ill, Edward bypassed his half-sisters and provided for the succession of male heirs only. Around the end of May or early June Edward's condition worsened dramatically and he corrected his draft such that Lady Jane Grey herself, not just her putative sons, could inherit the Crown. To what extent Edward's document—especially this last change—was influenced by Northumberland, his confidant John Gates

, or still other members of the Privy Chamber like Edward's tutor John Cheke

or Secretary William Petre

, is unclear.

Edward fully endorsed it. He personally supervised the copying of his will and twice summoned lawyers to his bedside to give them orders. On the second occasion, 15 June, Northumberland kept a watchful eye over the proceedings. Days before, the Duke had intimidated the judges who were raising legal objections to the "devise": In full Council he had lost his temper, "being in a great rage and fury, trembling for anger" and saying "that he would fight in his shirt with any man in that quarrel". So Judge Montague remembered in his petition to Queen Mary; he also recalled that, in Edward's chamber, the Lords of the Council declared it would be open treason

to disobey their sovereign's explicit command. The next step was an engagement to perform the King's will after his death, signed in his presence by Northumberland and 23 others. Finally, the King's official "declaration", issued as letters patent

, was signed by 102 notables, among them the whole Privy Council, peers, bishops, judges, and London aldermen. Edward also announced to have it passed in parliament

in September, and the necessary writs were prepared.

It was now common knowledge that Edward was dying. The Imperial ambassador, Jehan de Scheyfye, had been convinced for years that Dudley was engaged in some "mighty plot" to settle the Crown on his own head. As late as 12 June, though, he still knew nothing specific, despite having inside information about Edward's sickness. Instead he had recently reported that Northumberland would divorce his wife so as to marry Princess Elizabeth. France, which found the prospect of the Emperor's cousin on the English throne disagreeable, gave indications of support to Northumberland. Since the Duke did not rule out an armed intervention from Charles V

, he came back on the French offer after the King's death, sending a secret and non-committal mission to King Henry II

. After Jane's accession in July the ambassadors of both powers were convinced she would prevail, although they were in no doubt that the common people backed Mary. Antoine de Noailles wrote of Guildford Dudley as "the new King", while the Emperor instructed his envoys to arrange themselves with the Duke and to discourage Mary from undertaking anything dangerous.

Whether altering the succession was Edward's own idea or not, he was determinedly at work to exclude his half-sisters in favour of what he perceived as his jeopardized legacy. The original provisions of the "devise" have been described as bizarre and obsessive and as typical of a teenager, while incompatible with the mind and needs of a pragmatical politician. Mary's accession could cost Northumberland his head, but not necessarily so. He tried hard to please her during 1553, and may have shared the general assumption that she would succeed to the Crown as late as early June. At a meeting with the French ambassadors he asked them out of the blue what they would do in his place. Faced with Edward's express royal will and perseverance, John Dudley submitted to his master's wishes—either seeing his chance to retain his power beyond the boy's lifetime or out of loyalty.

Edward VI died on 6 July 1553. The next morning Northumberland sent his son Robert

Edward VI died on 6 July 1553. The next morning Northumberland sent his son Robert

into Hertfordshire

with 300 men to secure the person of Mary Tudor. Aware of her half-brother's condition, the Princess had only days before moved to East Anglia

, where she was the greatest landowner. She began to assemble an armed following and sent a letter to the Council, demanding to be recognized as queen. It arrived on 10 July, the day Jane Grey was proclaimed as queen. The Duke of Northumberland's detailed oration, held kneeling before Jane the previous day, did not move her to accept the Crown—her parents' assistance was required for that. Dudley had not prepared for resolute action on Mary's part and needed a week to build up a larger force. He was in a dilemma over who should lead the troops. He was the most experienced general in the kingdom, but he did not want to leave the government in the hands of his colleagues, in some of whom he had little confidence. Queen Jane decided the issue by demanding that her father, the Duke of Suffolk, should remain with her and the Council. On 14 July Northumberland headed for Cambridge

with 1,500 troops and some artillery

, having reminded his colleagues of the gravity of the cause, "what chance of variance soever might grow amongst you in my absence".

Supported by gentry and nobility in East Anglia and the Thames Valley

, Mary's military camp was gathering strength daily and, through luck, came into possession of powerful artillery from the royal navy. In the circumstances the Duke deemed fighting a campaign hopeless. The army proceeded from Cambridge to Bury St Edmunds and retreated again to Cambridge. On 20 July a letter from the Council in London arrived, declaring that they had proclaimed Queen Mary and commanding Northumberland to disband the army and await events. Dudley did not contemplate resistance. He explained to his fellow-commanders that they had acted on the Council's orders all the time and that he did not now wish "to combat the Council's decisions, supposing that they have been moved by good reasons ... and I beg your lordships to do the same." Proclaiming Mary Tudor at the market place, he threw up his cap and "so laughed that the tears ran down his cheeks for grief." The next morning the Earl of Arundel arrived to arrest him. A week earlier Arundel had assured Northumberland of his wish to spill his blood even at the Duke's feet; now Dudley went down on his knees as soon as he caught sight of him.

Northumberland rode through the City of London

to the Tower on 25 July, with his guards struggling to protect him against the hostile populace. A pamphlet appearing shortly after his arrest illustrated the general hatred of him: "the great devil Dudley ruleth, Duke I should have said". He was now commonly thought to have poisoned King Edward while Mary "would have been as glad of her brother's life, as the ragged bear is glad of his death". Dumbfounded by the turn of events, the French ambassador Noailles wrote: "I have witnessed the most sudden change believable in men, and I believe that God alone worked it." David Loades

, biographer of both Queen Mary and John Dudley, concludes that the lack of fighting clouds the fact that this outcome was a close-run affair, and warns

. Answered that the Great Seal of a usurper was worth nothing, he asked "whether any such persons as were equally culpable of that crime ... might be his judges". After sentence was passed, he begged the Queen's mercy for his five sons, the eldest of whom was condemned with him, the rest waiting for their trials. He also asked to "confess to a learned divine" and was visited by Bishop Stephen Gardiner, who had passed most of Edward's reign in the Tower and was now Mary's Lord Chancellor

. The Duke's execution was planned for 21 August at eight in the morning; however, it was suddenly cancelled. Northumberland was instead escorted to St Peter ad Vincula, where he took the Catholic communion

and professed that "the plagues that is upon the realm and upon us now is that we have erred from the faith these sixteen years." A great propaganda coup for the new government, Dudley's words were officially distributed—especially in the territories of the Emperor Charles V. In the evening the Duke learnt "that I must prepare myself against tomorrow to receive my deadly stroke", as he wrote in a desperate plea to the Earl of Arundel: "O my good lord remember how sweet life is and how bitter ye contrary." On the scaffold, before 10,000 people, Dudley confessed his guilt but maintained:

about the Duke of Northumberland was already in the making when he was still in power, the more after his fall. From the last days of Henry VIII he was to have planned, years in advance, the destruction of both King Edward's Seymour uncles—Lord Thomas

and the Protector—as well as Edward himself. He also served as an indispensable scapegoat: It was the most practical thing for Queen Mary to believe that Dudley had been acting all alone and it was in nobody's interest to doubt it. Further questions were unwelcome, as Charles V's ambassadors found out: "it was thought best not to inquire too closely into what had happened, so as to make no discoveries that might prejudice those [who tried the duke]". By renouncing the Protestantism he had so conspicuously stood for, Northumberland lost every respect and became ineligible for rehabilitation in a world dominated by thinking along sectarian

lines. Protestant writers like John Foxe

and John Ponet

concentrated on the pious King Edward's achievements and reinvented Somerset as the "good Duke"—it followed that there had also to be a "wicked Duke". This interpretation was enhanced by the High and Late Victorian

historians, James Anthony Froude

and A. F. Pollard, who saw Somerset as a champion of political liberty whose desire "to do good" was thwarted by, in Pollard's phrase, "the subtlest intriguer in English History".

As late as 1968/1970, W.K. Jordan embraced this good duke/bad duke dichotomy in a two-volume study of Edward VI's reign. However, he saw the King on the verge of assuming full authority at the beginning of 1553 (with Dudley contemplating retirement) and ascribed the succession alteration to Edward's resolution, Northumberland playing the part of the loyal and tragic enforcer instead of the original instigator. Many historians have since seen the "devise" as Edward's very own project. Others, while remarking upon the plan's sloppy implementation, have seen Northumberland as behind the scheme, yet in concord with Edward's convictions; the Duke acting out of despair for his own survival, or to rescue political and religious reform and save England from Habsburg domination.

Since the 1970s, critical reassessments of the Duke of Somerset's policies and government style led to acknowledgment that Northumberland revitalized and reformed the Privy Council as a central part of the administration, and that he "took the necessary but unpopular steps to hold the minority regime together". Stability and reconstruction have been made out as the mark of most of his policies; the scale of his motivation ranging from "determined ambition" with Geoffrey Rudolph Elton

in 1977 to "idealism of a sort" with Diarmaid MacCulloch

in 1999. Dale Hoak concluded in 1980: "given the circumstances which he inherited in 1549, the duke of Northumberland appears to have been one of the most remarkably able governors of any European state during the sixteenth century."

of his Protestant faith before his execution delighted Queen Mary and enraged Lady Jane Grey. The general opinion, especially among Protestants, was that he tried to seek a pardon by this move. Historians have often believed that he had no faith whatsoever, being a mere cynic. Further explanations—both contemporary and modern—have been that Northumberland sought to rescue his family from the axe, that, in the face of catastrophe, he found a spiritual home in the church of his childhood, or that he saw the hand of God in Mary's success. Although he endorsed the Reformation from at least the mid-1530s, Dudley may not have understood theological subtleties, being a "simple man in such matters". The Duke was stung by an outspoken letter he received from John Knox, whom he had invited to preach before the King and in vain had offered a bishopric. William Cecil was informed:

Northumberland was not an old-style peer, despite his aristocratic ancestry and existence as a great lord. He acquired, sold, and exchanged lands, but never strove to build himself a territorial power base or a large armed force of retainer

s (which proved fatal in the end). His maximum income of ₤4,300 p.a. from land and a ₤2,000 p.a. from annuities

and fee

s, was appropriate to his rank and figured well below the annuity of ₤5,333 p.a. the Duke of Somerset had granted himself, thus reaching an income of over ₤10,000 p.a. while in office. John Dudley was a typical Tudor Crown servant, self-interested but absolutely loyal to the incumbent sovereign: The monarch's every wish was law. This uncritical stance may have played a decisive role in Northumberland's decision to implement Edward's succession device, as it did in his attitude towards Mary when she had become Queen. The fear his services could be inadequate or go unacknowledged by the monarch was constant in Dudley, who also was very sensitive on what he called "estimation", meaning status. Edmund Dudley

was unforgotten: "my poor father's fate who, after his master was gone, suffered death for doing his master's commandments", the Duke wrote to Cecil nine months before his own end.

John Dudley was an imposing figure, capable both of terrifying outbursts of temper and of shedding tears. He also charmed people with his courtesy and a graceful presence. He was a family man, an understanding father and husband who was passionately loved by his wife. Frequent phases of illness, partly due to a stomach ailment, occasioned long absences from court but did not reduce his high output of paperwork, and may have had an element of hypochondria

in them. The English diplomat Richard Morrison

wrote of his onetime superior: "This Earl had such a head that he seldom went about anything but he had three or four purposes beforehand." A French eyewitness of 1553 described him as "an intelligent man who could explain his ideas and who displayed an impressive dignity. Others, who did not know him, would have considered him worthy of a kingdom." The Venetian

ambassador's assessment after Dudley's execution was: "the friends of England must lament the loss of all his qualities with that single exception (his last rashness)".

|-

|-

|-

|-

|-

|-

|-

|-

Edward VI of England

Edward VI was the King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death. He was crowned on 20 February at the age of nine. The son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour, Edward was the third monarch of the Tudor dynasty and England's first monarch who was raised as a Protestant...

from 1550 until 1553, and unsuccessfully tried to install Lady Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey , also known as The Nine Days' Queen, was an English noblewoman who was de facto monarch of England from 10 July until 19 July 1553 and was subsequently executed...

on the English throne after the King's death. The son of Edmund Dudley

Edmund Dudley

Edmund Dudley was an English administrator and a financial agent of King Henry VII. He served as Speaker of the House of Commons and President of the King's Council. After the accession of Henry VIII, he was imprisoned in the Tower of London and executed the next year on a treason charge...

, a minister of Henry VII

Henry VII of England

Henry VII was King of England and Lord of Ireland from his seizing the crown on 22 August 1485 until his death on 21 April 1509, as the first monarch of the House of Tudor....

executed by Henry VIII

Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII was King of England from 21 April 1509 until his death. He was Lord, and later King, of Ireland, as well as continuing the nominal claim by the English monarchs to the Kingdom of France...

, John Dudley became the ward

Ward (law)

In law, a ward is someone placed under the protection of a legal guardian. A court may take responsibility for the legal protection of an individual, usually either a child or incapacitated person, in which case the ward is known as a ward of the court, or a ward of the state, in the United States,...

of Sir Edward Guildford

Edward Guilford

Sir Edward Guildford was an English courtier and Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports and Marshal of Calais in 1519.-Family:...

at the age of seven. He grew up in Guildford's household together with his future wife, Guildford's daughter Jane

Jane Dudley, Duchess of Northumberland

Jane Dudley , Duchess of Northumberland was an English noblewoman, the wife of John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland and mother of Guildford Dudley and Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester. Having grown up with her future husband, who was her father's ward, she married at about age 16. They had...

, with whom he was to have 13 children. Dudley served as Vice-Admiral and Lord Admiral from 1537 until 1547, during which time he set novel standards of navy organization and was an innovative commander at sea. He also developed a strong interest in overseas exploration

Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery, also known as the Age of Exploration and the Great Navigations , was a period in history starting in the early 15th century and continuing into the early 17th century during which Europeans engaged in intensive exploration of the world, establishing direct contacts with...

. Dudley took part in the 1544 campaigns in Scotland and France and was one of Henry VIII's intimates in the last years of the reign. He was also a leader of the religious reform party at court.

In 1547 Dudley was created Earl of Warwick

Earl of Warwick

Earl of Warwick is a title that has been created four times in British history and is one of the most prestigious titles in the peerages of the British Isles.-1088 creation:...

and, with the Duke of Somerset

Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset

Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, 1st Earl of Hertford, 1st Viscount Beauchamp of Hache, KG, Earl Marshal was Lord Protector of England in the period between the death of Henry VIII in 1547 and his own indictment in 1549....

, England's Lord Protector

Lord Protector

Lord Protector is a title used in British constitutional law for certain heads of state at different periods of history. It is also a particular title for the British Heads of State in respect to the established church...

, distinguished himself in the renewed Scottish war

The Rough Wooing

The War of the Rough Wooing was fought between Scotland and England. War was declared by Henry VIII of England, in an attempt to force the Scots to agree to a marriage between his son Edward and Mary, Queen of Scots. Scotland benefited from French military aid. Edward VI continued the war until...

at the Battle of Pinkie. During the country-wide uprisings of 1549 Dudley put down Kett's Rebellion

Kett's Rebellion

Kett's Rebellion was a revolt in Norfolk, England during the reign of Edward VI. The rebellion was in response to the enclosure of land. It began in July 1549 but was eventually crushed by forces loyal to the English crown....

in Norfolk

Norfolk

Norfolk is a low-lying county in the East of England. It has borders with Lincolnshire to the west, Cambridgeshire to the west and southwest and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the North Sea coast and to the north-west the county is bordered by The Wash. The county...

. Convinced of the Protector's incompetence, he and other privy councillors forced Somerset out of office in October 1549. Having averted a conservative reaction in religion and a plot to destroy him alongside Somerset, Dudley emerged in early 1550 as de facto

De facto

De facto is a Latin expression that means "concerning fact." In law, it often means "in practice but not necessarily ordained by law" or "in practice or actuality, but not officially established." It is commonly used in contrast to de jure when referring to matters of law, governance, or...

regent

Regent

A regent, from the Latin regens "one who reigns", is a person selected to act as head of state because the ruler is a minor, not present, or debilitated. Currently there are only two ruling Regencies in the world, sovereign Liechtenstein and the Malaysian constitutive state of Terengganu...

for the 12-year-old Edward VI. He reconciled himself with Somerset, who nevertheless soon began to intrigue against him and his policies. Somerset was executed on largely fabricated charges, three months after Dudley had been raised to the Dukedom of Northumberland in October 1551.

As Lord President of the Council

Lord President of the Council

The Lord President of the Council is the fourth of the Great Officers of State of the United Kingdom, ranking beneath the Lord High Treasurer and above the Lord Privy Seal. The Lord President usually attends each meeting of the Privy Council, presenting business for the monarch's approval...

, Dudley headed a distinctly conciliar

Privy council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a nation, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the monarch's closest advisors to give confidential advice on...

government and sought to introduce the adolescent King into business. Taking over an almost bankrupt administration, he ended the costly wars with France and Scotland and tackled finances in ways that led to some economic recovery. To prevent further uprisings he introduced countrywide policing on a local basis, appointing Lords Lieutenants

Lord Lieutenant

The title Lord Lieutenant is given to the British monarch's personal representatives in the United Kingdom, usually in a county or similar circumscription, with varying tasks throughout history. Usually a retired local notable, senior military officer, peer or business person is given the post...

who were in close contact with the central authority. Dudley's religious policy was—in accordance with Edward's proclivities—decidedly Protestant, further enforcing the English Reformation

English Reformation

The English Reformation was the series of events in 16th-century England by which the Church of England broke away from the authority of the Pope and the Roman Catholic Church....

and promoting radical reformers to high Church positions.

The 15-year-old King fell ill in early 1553 and excluded his half-sisters Mary

Mary I of England

Mary I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from July 1553 until her death.She was the only surviving child born of the ill-fated marriage of Henry VIII and his first wife Catherine of Aragon. Her younger half-brother, Edward VI, succeeded Henry in 1547...

and Elizabeth

Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death. Sometimes called The Virgin Queen, Gloriana, or Good Queen Bess, Elizabeth was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty...

, whom he regarded as illegitimate, from the succession, designating non-existent, hypothetical male heirs. As his death approached, Edward changed his will so that his Protestant cousin Jane Grey, Northumberland's daughter-in-law, could inherit the Crown. To what extent the Duke influenced this scheme is uncertain. The traditional view is that it was Northumberland's plot to maintain his power by placing his family on the throne. Many historians see the project as genuinely Edward's, enforced by Dudley after the King's death. The Duke did not prepare well for this occasion. Having marched to East Anglia

East Anglia

East Anglia is a traditional name for a region of eastern England, named after an ancient Anglo-Saxon kingdom, the Kingdom of the East Angles. The Angles took their name from their homeland Angeln, in northern Germany. East Anglia initially consisted of Norfolk and Suffolk, but upon the marriage of...

to capture Princess Mary, he surrendered on hearing that the Privy Council had changed sides and proclaimed Mary as Queen. Convicted of high treason

High treason

High treason is criminal disloyalty to one's government. Participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplomats, or its secret services for a hostile and foreign power, or attempting to kill its head of state are perhaps...

, Northumberland returned to Catholicism and abjured the Protestant faith before his execution. Having secured the contempt of both religious camps, popularly hated, and a natural scapegoat, he became the "wicked Duke"—in contrast to his predecessor Somerset, the "good Duke". Only since the 1970s has he also been seen as a Tudor Crown servant: self-serving, inherently loyal to the incumbent monarch, and an able statesman in difficult times.

Career under Henry VIII

John Dudley was the eldest of three sons of Edmund DudleyEdmund Dudley

Edmund Dudley was an English administrator and a financial agent of King Henry VII. He served as Speaker of the House of Commons and President of the King's Council. After the accession of Henry VIII, he was imprisoned in the Tower of London and executed the next year on a treason charge...

, a councillor

Privy council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a nation, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the monarch's closest advisors to give confidential advice on...

of King Henry VII, and his second wife Elizabeth Grey, daughter of Edward Grey, 4th Viscount Lisle. His father was attainted and executed for high treason

High treason

High treason is criminal disloyalty to one's government. Participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplomats, or its secret services for a hostile and foreign power, or attempting to kill its head of state are perhaps...

in 1510, having been arrested immediately after Henry VIII

Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII was King of England from 21 April 1509 until his death. He was Lord, and later King, of Ireland, as well as continuing the nominal claim by the English monarchs to the Kingdom of France...

's accession because the new King needed scapegoats for his predecessor's unpopular financial policies. In 1512 the seven-year-old John became the ward

Ward (law)

In law, a ward is someone placed under the protection of a legal guardian. A court may take responsibility for the legal protection of an individual, usually either a child or incapacitated person, in which case the ward is known as a ward of the court, or a ward of the state, in the United States,...

of Sir Edward Guildford and was taken into his household. At the same time Edmund Dudley's attainder was lifted and John Dudley was restored "in name and blood". The King was hoping for the good services "which the said John Dudley is likely to do". At about age 15 John Dudley probably went with his guardian to the Pale of Calais

Pale of Calais

The Pale of Calais is a historical region of France that was controlled by the Kingdom of England until 1558.- History :After the Battle of Crécy in 1346, Edward III of England, having renounced the throne of France, kept some territory within France, namely Aquitaine and the area around Calais,...

to serve there for the next years. He took part in Cardinal Wolsey's diplomatic voyages of 1521 and 1527, and was knighted by Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk

Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk

Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk, 1st Viscount Lisle, KG was the son of Sir William Brandon and Elizabeth Bruyn. Through his third wife Mary Tudor he was brother-in-law to Henry VIII. His father was the standard-bearer of Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond and was slain by Richard III in person at...

during his first major military experience, the 1523 invasion of France. In 1524 Dudley became a Knight of the Body, a special mark of the King's favour, and from 1534 he was responsible for the King's body armour

Plate armour

Plate armour is a historical type of personal armour made from iron or steel plates.While there are early predecessors such the Roman-era lorica segmentata, full plate armour developed in Europe during the Late Middle Ages, especially in the context of the Hundred Years' War, from the coat of...

as Master of the Tower Armoury. Being "the most skilful of his generation, both on foot and on horseback", he excelled in wrestling

Wrestling

Wrestling is a form of grappling type techniques such as clinch fighting, throws and takedowns, joint locks, pins and other grappling holds. A wrestling bout is a physical competition, between two competitors or sparring partners, who attempt to gain and maintain a superior position...

, archery

Archery

Archery is the art, practice, or skill of propelling arrows with the use of a bow, from Latin arcus. Archery has historically been used for hunting and combat; in modern times, however, its main use is that of a recreational activity...

, and the tournament

Tournament

A tournament is a competition involving a relatively large number of competitors, all participating in a sport or game. More specifically, the term may be used in either of two overlapping senses:...

s of the royal court, as a French report stated as late as 1546.

In 1525 Dudley married Guildford's daughter Jane

Jane Dudley, Duchess of Northumberland

Jane Dudley , Duchess of Northumberland was an English noblewoman, the wife of John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland and mother of Guildford Dudley and Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester. Having grown up with her future husband, who was her father's ward, she married at about age 16. They had...

, who was four years his junior and his former class-mate. The Dudleys belonged to the new evangelical

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led...

circles of the early 1530s, and their 13 children were educated in Renaissance humanism and science

Renaissance humanism

Renaissance humanism was an activity of cultural and educational reform engaged by scholars, writers, and civic leaders who are today known as Renaissance humanists. It developed during the fourteenth and the beginning of the fifteenth centuries, and was a response to the challenge of Mediæval...

. Sir Edward Guildford died in 1534 without a written will. His only son having predeceased him, Guildford's nephew, John Guildford

John Guilford

Sir John Guildford was an English Member of Parliament for Gatton, New Romney and Kent and was appointed Sheriff of Kent in 1552.-Life:...

, asserted that his uncle had intended him to inherit. Dudley and his wife contested this claim. The parties went to court and Dudley, who had secured Thomas Cromwell's patronage

Patronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows to another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings or popes have provided to musicians, painters, and sculptors...

, won the case. In 1532 he lent his cousin, John Sutton, 3rd Baron Dudley

John Sutton, 3rd Baron Dudley

John Sutton, 3rd Baron Dudley , commonly known as Lord Quondam, was the eldest son and heir of Sir Edward Sutton, 2nd Baron Dudley and his wife Lady Cicely Sutton, a descendant of Edward III of England....

, over ₤

Pound sterling

The pound sterling , commonly called the pound, is the official currency of the United Kingdom, its Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, British Antarctic Territory and Tristan da Cunha. It is subdivided into 100 pence...

7,000 on the security of the baronial estate. Lord Dudley was unable to pay off any of his creditors, so when the mortgage was foreclosed in the late 1530s Sir John Dudley came into possession of Dudley Castle

Dudley Castle

Dudley Castle is a ruined castle in the town of Dudley, West Midlands, England. Dudley Zoo is located in its grounds. The location, Castle Hill, is an outcrop of Wenlock Group limestone that was extensively quarried during the Industrial Revolution, and which now along with Wren's Nest Hill is a...

.

Dudley was present at Henry VIII's meeting with Francis I of France

Francis I of France

Francis I was King of France from 1515 until his death. During his reign, huge cultural changes took place in France and he has been called France's original Renaissance monarch...

at Calais

Calais

Calais is a town in Northern France in the department of Pas-de-Calais, of which it is a sub-prefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's capital is its third-largest city of Arras....

in 1532. Another member of the entourage was Anne Boleyn

Anne Boleyn

Anne Boleyn ;c.1501/1507 – 19 May 1536) was Queen of England from 1533 to 1536 as the second wife of Henry VIII of England and Marquess of Pembroke in her own right. Henry's marriage to Anne, and her subsequent execution, made her a key figure in the political and religious upheaval that was the...

, who was soon to be queen. Dudley took part in the christenings of Princess Elizabeth and Prince Edward and, in connection with the announcement of the Prince's birth to the Emperor

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a realm that existed from 962 to 1806 in Central Europe.It was ruled by the Holy Roman Emperor. Its character changed during the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, when the power of the emperor gradually weakened in favour of the princes...

, travelled to Spain via France in October 1537. He sat in the Reformation parliament in 1534–1536, and led one of the contingents sent against the Pilgrimage of Grace

Pilgrimage of Grace

The Pilgrimage of Grace was a popular rising in York, Yorkshire during 1536, in protest against Henry VIII's break with the Roman Catholic Church and the Dissolution of the Monasteries, as well as other specific political, social and economic grievances. It was done in action against Thomas Cromwell...

in late 1536. In January 1537 Dudley was made Vice-Admiral and began to apply himself enthusiastically to naval matters. He was briefly Master of the Horse to Anne of Cleves

Anne of Cleves

Anne of Cleves was a German noblewoman and the fourth wife of Henry VIII of England and as such she was Queen of England from 6 January 1540 to 9 July 1540. The marriage was never consummated, and she was not crowned queen consort...

, and in 1542 was granted his grandfather's title of Viscount Lisle

Viscount Lisle

The title of Viscount Lisle has been created six times in the Peerage of England. The first creation, on 30 October 1451, was for John Talbot, 1st Baron Lisle. Upon the death of his son Thomas at the Battle of Nibley Green in 1470, the viscountcy became extinct and the barony abeyant.In 1475, the...

—after the death of his stepfather Arthur Plantagenet and "by the right of his mother". Being now a peer

Peerage

The Peerage is a legal system of largely hereditary titles in the United Kingdom, which constitute the ranks of British nobility and is part of the British honours system...

, Dudley became Lord Admiral and a Knight of the Garter in 1543; he was also admitted to the Privy Council

Privy Council of the United Kingdom

Her Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, usually known simply as the Privy Council, is a formal body of advisers to the Sovereign in the United Kingdom...

. In the aftermath of the Battle of Solway Moss

Battle of Solway Moss

The Battle of Solway Moss took place on Solway Moss near the River Esk on the English side of the Anglo-Scottish Border in November 1542 between forces from England and Scotland.-Background:...

in 1542 he served as Warden of the Scottish Marches

Scottish Marches

Scottish Marches was the term used for the Anglo-Scottish border during the late medieval and early modern eras—from the late 13th century, with the creation by Edward I of England of the first Lord Warden of the Marches to the early 17th century and the creation of the Middle Shires, promulgated...

, and in the 1544 campaign the English force under Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford

Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset

Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, 1st Earl of Hertford, 1st Viscount Beauchamp of Hache, KG, Earl Marshal was Lord Protector of England in the period between the death of Henry VIII in 1547 and his own indictment in 1549....

was supported by a fleet which Dudley commanded. Dudley joined the land force that destroyed Edinburgh

Burning of Edinburgh (1544)

The Burning of Edinburgh in 1544 by an English sea-borne army was the first major action of the war of the Rough Wooing. A Scottish army observed the landing on 3 May 1544 but did not engage with the English force. The Provost of Edinburgh was compelled to allow the English to sack Leith and...

, after he had blown the main gate apart with a culverin

Culverin

A culverin was a relatively simple ancestor of the musket, and later a medieval cannon, adapted for use by the French in the 15th century, and later adapted for naval use by the English in the late 16th century. The culverin was used to bombard targets from a distance. The weapon had a...

. In late 1544 he was appointed Governor of Boulogne, the siege of which had cost the life of his eldest son, Henry. His tasks were to rebuild the fortifications to King Henry's design and to fend off French attacks by sea and land.

Navy Board

The Navy Board is today the body responsible for the day-to-day running of the British Royal Navy. Its composition is identical to that of the Admiralty Board of the Defence Council of the United Kingdom, except that it does not include any of Her Majesty's Ministers.From 1546 to 1831, the Navy...

, which for the first time co-ordinated the various tasks of maintaining the navy functioning and thus made English naval administration the most efficient in Europe. At sea, Dudley's fighting orders were at the forefront of tactical

Military tactics

Military tactics, the science and art of organizing an army or an air force, are the techniques for using weapons or military units in combination for engaging and defeating an enemy in battle. Changes in philosophy and technology over time have been reflected in changes to military tactics. In...

thinking: Squadrons of ships, ordered by size and firepower, were to manoeuvre in formation, using co-ordinated gunfire. These were all new developments in the English navy. In 1545 he directed the fleet's operations before, during, and after the Battle of the Solent

Battle of the Solent

The naval Battle of the Solent took place on 18 and 19 July 1545 during the Italian Wars, fought between the fleets of Francis I of France and Henry VIII of England, in the Solent channel off the south coast of England between Hampshire and the Isle of Wight...

and entertained King Henry on the flagship Henri Grace a Dieu. A tragic loss was the sinking of the Mary Rose

Mary Rose

The Mary Rose was a carrack-type warship of the English Tudor navy of King Henry VIII. After serving for 33 years in several wars against France, Scotland, and Brittany and after being substantially rebuilt in 1536, she saw her last action on 1545. While leading the attack on the galleys of a...

with 500 men aboard. In 1546 John Dudley went to France for peace negotiations. When he suspected the Admiral of France

Admiral of France

The title Admiral of France is one of the Great Officers of the Crown of France, the naval equivalent of Marshal of France.The title was created in 1270 by Louis IX of France, during the Eighth Crusade. At the time it was equivalent to the office of Constable of France. The Admiral was responsible...

, Claude d'Annebault

Claude d'Annebault

Claude d'Annebault was a French military officer; Marshall of France ; Admiral of France ; and Governor of Piedmont in 1541. He led the French invasion of the Isle of Wight in 1545...

, of manoeuvres which might have led to a renewal of hostilities, he suddenly put to sea in a show of English strength, before returning to the negotiating table. He then travelled to Fontainebleau

Fontainebleau

Fontainebleau is a commune in the metropolitan area of Paris, France. It is located south-southeast of the centre of Paris. Fontainebleau is a sub-prefecture of the Seine-et-Marne department, and it is the seat of the arrondissement of Fontainebleau...

, where the English delegates were entertained by the Dauphin Henri

Henry II of France

Henry II was King of France from 31 March 1547 until his death in 1559.-Early years:Henry was born in the royal Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, near Paris, the son of Francis I and Claude, Duchess of Brittany .His father was captured at the Battle of Pavia in 1525 by his sworn enemy,...

and King Francis. In the Peace of Camp, the French king acknowledged Henry VIII's title as "Supreme Head of the Church of England and Ireland", a success for both England and her Lord Admiral.

John Dudley, popularly fêted and highly regarded by King Henry as a general, became a royal intimate who played cards with the ailing monarch. Next to Edward Seymour, Prince Edward's maternal uncle, Dudley was one of the leaders of the Reformed party at court, and both their wives were among the friends of Anne Askew

Anne Askew

Anne Askew was an English poet and Protestant who was condemned as a heretic...

, the Protestant martyr destroyed by Bishop Stephen Gardiner

Stephen Gardiner

Stephen Gardiner was an English Roman Catholic bishop and politician during the English Reformation period who served as Lord Chancellor during the reign of Queen Mary I of England.-Early life:...

in July 1546. Dudley and the Queen's brother, William Parr

William Parr, 1st Marquess of Northampton

William Parr, 1st Marquess of Northampton, 1st Earl of Essex and 1st Baron Parr, KG was the son of Sir Thomas Parr and his wife, Maud Green, daughter of Sir Thomas Green, of Broughton and Greens Norton...

, tried to convince Anne Askew to conform to the Catholic doctrines of the Henrician church, yet she replied "it was great shame for them to counsel contrary to their knowledge". In September Dudley struck Gardiner in the face during a full meeting of the Council. This was a grave offence, and he was lucky to escape with a month's leave from court in disgrace. In the last weeks of the reign Seymour and Dudley played their parts in Henry's strike against the conservative House of Howard

Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk

Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, KG, Earl Marshal was a prominent Tudor politician. He was uncle to Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard, two of the wives of King Henry VIII, and played a major role in the machinations behind these marriages...

, thus clearing the path for a Protestant minority rule. They were seen as the likely leaders of the impending regency

Regent

A regent, from the Latin regens "one who reigns", is a person selected to act as head of state because the ruler is a minor, not present, or debilitated. Currently there are only two ruling Regencies in the world, sovereign Liechtenstein and the Malaysian constitutive state of Terengganu...

—"there are no other nobles of a fit age and ability for the task", Eustache Chapuys, the former Imperial ambassador, commented from his retirement.

From Earl of Warwick to Duke of Northumberland

The 16 executorExecutor

An executor, in the broadest sense, is one who carries something out .-Overview:...

s of Henry VIII's will also embodied the Regency Council that had been appointed to rule collectively during Edward VI's minority. The new Council agreed on making Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford Lord Protector

Lord Protector

Lord Protector is a title used in British constitutional law for certain heads of state at different periods of history. It is also a particular title for the British Heads of State in respect to the established church...

with full powers, which in effect were those of a prince. At the same time the Council awarded themselves a round of promotions based on Henry VIII's wishes; the Earl of Hertford became the Duke of Somerset and John Dudley was created Earl of Warwick

Earl of Warwick

Earl of Warwick is a title that has been created four times in British history and is one of the most prestigious titles in the peerages of the British Isles.-1088 creation:...

. The new Earl had to pass on his post of Lord Admiral to Somerset's brother, Thomas Seymour

Thomas Seymour, 1st Baron Seymour of Sudeley

Thomas Seymour, 1st Baron Seymour of Sudeley, KG was an English politician.Thomas spent his childhood in Wulfhall, outside Savernake Forest, in Wiltshire. Historian David Starkey describes Thomas thus: 'tall, well-built and with a dashing beard and auburn hair, he was irresistible to women'...

, but advanced to Lord Great Chamberlain

Lord Great Chamberlain

The Lord Great Chamberlain of England is the sixth of the Great Officers of State, ranking beneath the Lord Privy Seal and above the Lord High Constable...

. Perceived as the most important man next the Protector, he was on friendly terms with Somerset, who soon reopened the war with Scotland. Dudley accompanied him as second-in-command with a taste for personal combat. On one occasion he fought his way out of an ambush and, spear in hand, chased his Scottish counterpart for some 250 yards, nearly running him through. In the Battle of Pinkie Dudley led the vanguard, being "one of the key architects of the English victory".