Cortes Generales

Encyclopedia

The Cortes Generales (ˈkortes xeneˈɾales, General Courts) is the legislature

of Spain

. It is a bicameral parliament, composed of the Congress of Deputies (the lower house

) and the Senate

(the upper house

). The Cortes has power to enact any law

and to amend the constitution

. Moreover, the lower house has the power to confirm and dismiss the President of the Government

(or prime minister

).

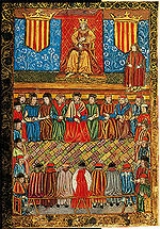

as part of feudalism

. A "Corte" was an advisory council made up of the most powerful feudal lords closest to the king. The Cortes of the Kingdom of León

date from 1188 AD, and formed part of the first Spanish government with some claim to being representative. The Cortes of León

were the first parliamentary body in Western Europe From 1230, the Cortes of Leon and Castile were merged, though the Cortes' power was decreasing. Prelates, nobles and commoners remained separated in the three estates within the Cortes. The king had the ability to call and dismiss the Cortes, but, as the lords of the Cortes headed the army and controlled the purse, the King usually signed treaties

with them to pass bills for war at the cost of concessions to the lords and the Cortes.

started to grow: people living in the cities were neither vassal

s (servants of feudal lords) nor nobles themselves. Furthermore, the nobles were experiencing very hard economic times due to the Reconquista

; so now the bourgeoisie

(Spanish burguesía, from burgo, city) had the money and thus the power. So the King started admitting representatives from the cities to the Cortes in order to get more money for the Reconquista. The frequent payoffs were the "Fuero

s", grants of autonomy to the cities and their inhabitants. At this time the Cortes already had the power to oppose the King's decisions, thus effectively vetoing them. In addition, some representatives (elected from the Cortes members by itself) were permanent advisors to the King, even when the Cortes was not.

and Ferdinand II of Aragon

, the Catholic Monarchs

, started a specific policy to diminish the power of the bourgeoisie and nobility. They greatly reduced the powers of the Cortes to the point where they simply rubberstamped

the monarch's acts, and brought the nobility to their side. One of the major points of friction between the Cortes and the monarchs was the power of raising and lowering taxes. It was the only matter that the Cortes had under some direct control; when Queen Isabella wanted to fund Christopher Columbus

's trip, she had a hard time battling with the bourgeoisie to get the Cortes' approval.

was mainly to rubberstamp the decisions of the ruling monarch. However, they had some power over economic and American affairs, especially taxes. The Siglo de oro, Spanish Golden Age of literacy, was a dark age in Spanish politics: the Netherlands

declared itself independent and started a war, while some of the last Habsburg

monarchs did not rule the country, leaving this task in the hands of viceroy

s governing in their name, the most famous being the Count-Duke of Olivares

, Philip IV

's viceroy. This allowed the Cortes to become more influential, even when they did not directly oppose the King's decisions (or viceroys' decisions in the name of the King).

The states of the Crown of Aragon

The states of the Crown of Aragon

(Aragon, Catalonia and Valencia) and the Kingdom of Navarre

were self-governing entities separate from Castile, until the Nueva Planta Decrees

of 1707 abolished this autonomy and united Aragon with Castile in a centralised Spanish state. The abolition in the realms of Aragon was completed by 1716, whilst Navarre retained its autonomy until the 1833 territorial division of Spain

. It is the only of the Spanish territories whose current status in the Spanish state is legally linked with the old Fuero

s: its Statute of Autonomy

specifically cites them and recognizes their special status, while also recognizing the supremacy of the Spanish Constitution.

A Cortes (or Corts in Catalonia and Valencia) existed in each of Aragon, Catalonia, Valencia and Navarre. It is thought that these legislatures exercised more real power over local affairs than the Castilian Cortes did. Executive councils also existed in each of these realms, which were initially tasked with overseeing the implementation of decisions made by the Cortes. However, throughout the rule of the Habsburg and Bourbon

dynasties the Crown pressed for more centralization, enforcing an unitary position in foreign affairs and empowering Councils outside the control of the Cortes of the several Kingdoms. Thus, the Cortes in Spain did not develop towards a parliamentary system as in the British case, but towards the mentioned rubberstamping of royal decrees. Nevertheless, from time to time the Cortes tried to assert their control over budgetary issues, with varying grades of success.

operated as a government in exile. France

under Napoleon

had taken control of most of Spain during the Peninsular War

after 1808. The Cortes found refuge in the fortified, coastal city of Cádiz

. General Cortes were assembled in Cádiz, but since many provinces could not send representatives due to the French occupation, substitutes were chosen among the people of the city - thus the name Congress of Deputies. Liberal factions dominated the body and pushed through the Spanish Constitution of 1812

. Ferdinand VII, however, tossed it aside upon his restoration in 1814 and pursued conservative policies, making the constitution an icon for liberal movements in Spain. Many military coups were attempted, and finally Col. Rafael del Riego

's one succeeded and forced the King to accept the liberal constitution, which resulted in the Three Liberal Years (Trienio Liberal). The monarch not only did everything he could to obstruct the Government (vetoing nearly every law, for instance), but also asked many powers, including the Holy Alliance

, to invade his own country and restore his absolutist powers. He finally received a French army (The Hundred Thousand Sons of St. Louis

) which only met resistance in the liberal cities, but easily crushed the National Militia and forced many liberals to exile to, ironically, France. In his second absolutist period up to his death in 1833, Ferdinand VII was more cautious and did not try a full restoration of the Ancien Regime.

was abolished because of its royally appointed nature. A republic was proclaimed and the Congress of Deputies members started writing a Constitution, supposedly that of a federal republic

, with the power of Parliament being nearly supreme (see parliamentary supremacy, although Spain did not use the Westminster system

). However, due to many problems (mainly illiteracy of the people) Spain was not ready to become a republic; after several crises the republic collapsed, and the monarchy was restored in 1874.

, with the monarch as a rubberstamp to the Cortes' acts but with some reserve powers, such as appointing and dismissing the Prime Minister and appointing senators for the new Senate

, remade as an elected House.

Soon after the Soviet revolution

(1917), the Spanish political parties started polarizing, and the left-wing Communist Party (PCE) and Spanish Socialist Workers' Party

(PSOE) blamed the Government for supposed election fraud in small towns (caciquismo), which was incorrectly supposed to have been wiped out in the 1900s by the failed regenerationist movement. In the meantime, spiralling violence started with the murders of many leaders by both sides. Deprived of those leaders, the regime entered a general crisis, with extreme police measures which led to a dictatorship (1921–1930) during which the Senate was again abolished.

, called for local elections. The results were overwhelmingly favorable to the monarchist cause nationally, but most provincial capitals and other sizable cities sided heavily with the republicans. This was interpreted as a victory, as the rural results were under the always-present suspicion of caciquismo and other irregularities while the urban results were harder to influence. The King left Spain, and a Republic was declared on April 14, 1931.

The Second Spanish Republic was established as a presidential republic, with an unicameral

Parliament and a President of the Republic as the Head of State

. Among his powers were the appointment and dismissal of the Prime Minister

, either on the advice of Parliament or just having consulted it before, and a limited power to dissolve the Parliament and call for new elections.

The first term was the constituent term charged with creating the new Constitution

, with the ex-monarchist leader Niceto Alcalá Zamora as President of the Republic and the left-wing leader Manuel Azaña

as Prime Minister. The election

gave a majority in the Cortes and thus, the Government, to a coalition between Azaña's party and the PSOE. A remarkable deed is universal suffrage

, allowing women to vote, a provision highly criticized by Socialist leader Indalecio Prieto

, who said the Republic had been backstabbed. Also, for the second time in Spanish history, some regions were granted autonomous governments within the unitary state. Many on the extreme right rose up with General José Sanjurjo

in 1932 against the Government's social policies, but the coup was quickly defeated.

The elections for the second term were held in 1933

and won by the coalition between the Radical Party (center

) and the Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas (CEDA) (right

). Initially, only the Radical Party entered the Government, with the parliamentary support of the CEDA. However, in the middle of the term, several corruption scandals (among them the Straperlo

affair) sunk the Radical Party and the CEDA entered the Government in 1934. This led to uprisings by some leftist parties that were quickly suffocated. In one of them, the left wing government of Catalonia, which had been granted home rule, formally rebelled against the central government, denying its power. This provoked the dissolution of the Generalitat de Catalunya

and the imprisonment of their leaders. The leftist minority in the Cortes then pressed Alcalá Zamora for a dissolution, arguing that the uprising were the consequence of social rejection of the right-wing government. The President, a former monarchist Minister wary of the authoritarism of the right, dissolved Parliament.

The next election

was held in 1936. It was hotly contested, with all parties converging into three coalitions: the leftist Popular Front

, the right-winged National Front

and a Centre coalition. In the end, the Popular Front won with a small edge in votes over the runner-up National Front, but achieved a solid majority due to the new electoral system introduced by the CEDA government hoping that they would get the edge in votes. The new Parliament then dismissed Alcalá-Zamora and installed Manuel Azaña

in his place. During the third term, the extreme polarisation of the Spanish society was more evident than ever in Parliament, with confrontation reaching the level of death threats. The already bad political and social climate created by the long term left-right confrontation worsened, and many right-wing rebellions were started. Then, in 1936, the Army's failed coup degenerated into the Spanish Civil War

, putting an end to the Second Republic.

's intention was to replace the unstable party system

with an "organic democracy", where the people could participate directly in the nation's politics without any parties.

During the period 1939 to 1942, the legislature of Spain worked essentially without constitution, with the 100 member National Council of the Falange

(similar to the politburo

of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

or the Grand Council of Fascism

in Italy

) replacing the General Assembly indefinitely. The Organic law

of 1942 effectively formed a de facto dictatorship, establishing a unicameral legislature ("Cortes"), made up of more than 400 "representatives" (Spanish: procuradores, singular procurador), with a majority to be appointed from the Falangist Party. The Cortes was un-elected and exercised only symbolic power, with legislative powers vested in the Franco-led government, but there was the possibility of referendums in cases of "serious alterations" of the constitution, in which case only the family heads

(including widows) were allowed to vote. Virtually powerless city councils were appointed through similar procedure.

).

The Congress is composed of 350 deputies (although that figure may change in the future as the constitution establishes a maximum of 400 and a minimum of 300) directly elected by universal suffrage approximately

every four years.

The Senate is partly directly elected (four senators per province as a general rule) and partly appointed (by the legislative assemblies of the autonomous communities

, two for each community and another one for every million inhabitants in their territory). Although the Senate was conceived as a territorial upper house, it has been argued by nationalist parties and the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party

that it doesn't accomplish such a task. Proposals to reform the Senate have been discussed for at least ten years as of November 2007.

Legislature

A legislature is a kind of deliberative assembly with the power to pass, amend, and repeal laws. The law created by a legislature is called legislation or statutory law. In addition to enacting laws, legislatures usually have exclusive authority to raise or lower taxes and adopt the budget and...

of Spain

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

. It is a bicameral parliament, composed of the Congress of Deputies (the lower house

Lower house

A lower house is one of two chambers of a bicameral legislature, the other chamber being the upper house.Despite its official position "below" the upper house, in many legislatures worldwide the lower house has come to wield more power...

) and the Senate

Spanish Senate

The Senate of Spain is the upper house of Spain's parliament, the . It is made up of 264 members: 208 elected by popular vote, and 56 appointed by the regional legislatures. All senators serve four-year terms, though regional legislatures may recall their appointees at any time.The last election...

(the upper house

Upper house

An upper house, often called a senate, is one of two chambers of a bicameral legislature, the other chamber being the lower house; a legislature composed of only one house is described as unicameral.- Possible specific characteristics :...

). The Cortes has power to enact any law

Law

Law is a system of rules and guidelines which are enforced through social institutions to govern behavior, wherever possible. It shapes politics, economics and society in numerous ways and serves as a social mediator of relations between people. Contract law regulates everything from buying a bus...

and to amend the constitution

Spanish Constitution of 1978

-Structure of the State:The Constitution recognizes the existence of nationalities and regions . Preliminary Title As a result, Spain is now composed entirely of 17 Autonomous Communities and two autonomous cities with varying degrees of autonomy, to the extent that, even though the Constitution...

. Moreover, the lower house has the power to confirm and dismiss the President of the Government

Prime Minister of Spain

The President of the Government of Spain , sometimes known in English as the Prime Minister of Spain, is the head of Government of Spain. The current office is established under the Constitution of 1978...

(or prime minister

Prime minister

A prime minister is the most senior minister of cabinet in the executive branch of government in a parliamentary system. In many systems, the prime minister selects and may dismiss other members of the cabinet, and allocates posts to members within the government. In most systems, the prime...

).

Origins: the Feudal Age (8th-12th centuries)

The system of Cortes arose in the Middle AgesMiddle Ages

The Middle Ages is a periodization of European history from the 5th century to the 15th century. The Middle Ages follows the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 and precedes the Early Modern Era. It is the middle period of a three-period division of Western history: Classic, Medieval and Modern...

as part of feudalism

Feudalism

Feudalism was a set of legal and military customs in medieval Europe that flourished between the 9th and 15th centuries, which, broadly defined, was a system for ordering society around relationships derived from the holding of land in exchange for service or labour.Although derived from the...

. A "Corte" was an advisory council made up of the most powerful feudal lords closest to the king. The Cortes of the Kingdom of León

Kingdom of León

The Kingdom of León was an independent kingdom situated in the northwest region of the Iberian Peninsula. It was founded in AD 910 when the Christian princes of Asturias along the northern coast of the peninsula shifted their capital from Oviedo to the city of León...

date from 1188 AD, and formed part of the first Spanish government with some claim to being representative. The Cortes of León

León's Spanish Parliament

The Spanish Parliament of the Kingdom of León was the first sample of modern parliamentarism in the history of Western Europe The Spanish Parliament of the Kingdom of León (1188) was the first sample of modern parliamentarism in the history of Western Europe The Spanish Parliament of the Kingdom...

were the first parliamentary body in Western Europe From 1230, the Cortes of Leon and Castile were merged, though the Cortes' power was decreasing. Prelates, nobles and commoners remained separated in the three estates within the Cortes. The king had the ability to call and dismiss the Cortes, but, as the lords of the Cortes headed the army and controlled the purse, the King usually signed treaties

Treaty

A treaty is an express agreement under international law entered into by actors in international law, namely sovereign states and international organizations. A treaty may also be known as an agreement, protocol, covenant, convention or exchange of letters, among other terms...

with them to pass bills for war at the cost of concessions to the lords and the Cortes.

The rise of the bourgeoisie (12th-15th centuries)

With the reappearance of the cities near the 12th century, a new social classSocial class

Social classes are economic or cultural arrangements of groups in society. Class is an essential object of analysis for sociologists, political scientists, economists, anthropologists and social historians. In the social sciences, social class is often discussed in terms of 'social stratification'...

started to grow: people living in the cities were neither vassal

Vassal

A vassal or feudatory is a person who has entered into a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. The obligations often included military support and mutual protection, in exchange for certain privileges, usually including the grant of land held...

s (servants of feudal lords) nor nobles themselves. Furthermore, the nobles were experiencing very hard economic times due to the Reconquista

Reconquista

The Reconquista was a period of almost 800 years in the Middle Ages during which several Christian kingdoms succeeded in retaking the Muslim-controlled areas of the Iberian Peninsula broadly known as Al-Andalus...

; so now the bourgeoisie

Bourgeoisie

In sociology and political science, bourgeoisie describes a range of groups across history. In the Western world, between the late 18th century and the present day, the bourgeoisie is a social class "characterized by their ownership of capital and their related culture." A member of the...

(Spanish burguesía, from burgo, city) had the money and thus the power. So the King started admitting representatives from the cities to the Cortes in order to get more money for the Reconquista. The frequent payoffs were the "Fuero

Fuero

Fuero , Furs , Foro and Foru is a Spanish legal term and concept.The word comes from Latin forum, an open space used as market, tribunal and meeting place...

s", grants of autonomy to the cities and their inhabitants. At this time the Cortes already had the power to oppose the King's decisions, thus effectively vetoing them. In addition, some representatives (elected from the Cortes members by itself) were permanent advisors to the King, even when the Cortes was not.

The Catholic Monarchs (15th century)

Isabella I of CastileIsabella I of Castile

Isabella I was Queen of Castile and León. She and her husband Ferdinand II of Aragon brought stability to both kingdoms that became the basis for the unification of Spain. Later the two laid the foundations for the political unification of Spain under their grandson, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor...

and Ferdinand II of Aragon

Ferdinand II of Aragon

Ferdinand the Catholic was King of Aragon , Sicily , Naples , Valencia, Sardinia, and Navarre, Count of Barcelona, jure uxoris King of Castile and then regent of that country also from 1508 to his death, in the name of...

, the Catholic Monarchs

Catholic Monarchs

The Catholic Monarchs is the collective title used in history for Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon. They were both from the House of Trastámara and were second cousins, being both descended from John I of Castile; they were given a papal dispensation to deal with...

, started a specific policy to diminish the power of the bourgeoisie and nobility. They greatly reduced the powers of the Cortes to the point where they simply rubberstamped

Rubber stamp (politics)

A rubber stamp, as a political metaphor, refers to a person or institution with considerable de jure power but little de facto power; one that rarely disagrees with more powerful organs....

the monarch's acts, and brought the nobility to their side. One of the major points of friction between the Cortes and the monarchs was the power of raising and lowering taxes. It was the only matter that the Cortes had under some direct control; when Queen Isabella wanted to fund Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus was an explorer, colonizer, and navigator, born in the Republic of Genoa, in northwestern Italy. Under the auspices of the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, he completed four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean that led to general European awareness of the American continents in the...

's trip, she had a hard time battling with the bourgeoisie to get the Cortes' approval.

The Imperial Cortes (16th-17th centuries)

The role of the Cortes during the Spanish EmpireSpanish Empire

The Spanish Empire comprised territories and colonies administered directly by Spain in Europe, in America, Africa, Asia and Oceania. It originated during the Age of Exploration and was therefore one of the first global empires. At the time of Habsburgs, Spain reached the peak of its world power....

was mainly to rubberstamp the decisions of the ruling monarch. However, they had some power over economic and American affairs, especially taxes. The Siglo de oro, Spanish Golden Age of literacy, was a dark age in Spanish politics: the Netherlands

Netherlands

The Netherlands is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, located mainly in North-West Europe and with several islands in the Caribbean. Mainland Netherlands borders the North Sea to the north and west, Belgium to the south, and Germany to the east, and shares maritime borders...

declared itself independent and started a war, while some of the last Habsburg

Habsburg

The House of Habsburg , also found as Hapsburg, and also known as House of Austria is one of the most important royal houses of Europe and is best known for being an origin of all of the formally elected Holy Roman Emperors between 1438 and 1740, as well as rulers of the Austrian Empire and...

monarchs did not rule the country, leaving this task in the hands of viceroy

Viceroy

A viceroy is a royal official who runs a country, colony, or province in the name of and as representative of the monarch. The term derives from the Latin prefix vice-, meaning "in the place of" and the French word roi, meaning king. A viceroy's province or larger territory is called a viceroyalty...

s governing in their name, the most famous being the Count-Duke of Olivares

Gaspar de Guzmán, Count-Duke of Olivares

Don Gaspar de Guzmán y Pimentel Ribera y Velasco de Tovar, Count-Duke of Olivares and Duke of San Lúcar la Mayor , was a Spanish royal favourite of Philip IV and minister. As prime minister from 1621 to 1643, he over-exerted Spain in foreign affairs and unsuccessfully attempted domestic reform...

, Philip IV

Philip IV of Spain

Philip IV was King of Spain between 1621 and 1665, sovereign of the Spanish Netherlands, and King of Portugal until 1640...

's viceroy. This allowed the Cortes to become more influential, even when they did not directly oppose the King's decisions (or viceroys' decisions in the name of the King).

Cortes in the kingdoms of Aragon and Navarre

Crown of Aragon

The Crown of Aragon Corona d'Aragón Corona d'Aragó Corona Aragonum controlling a large portion of the present-day eastern Spain and southeastern France, as well as some of the major islands and mainland possessions stretching across the Mediterranean as far as Greece...

(Aragon, Catalonia and Valencia) and the Kingdom of Navarre

Kingdom of Navarre

The Kingdom of Navarre , originally the Kingdom of Pamplona, was a European kingdom which occupied lands on either side of the Pyrenees alongside the Atlantic Ocean....

were self-governing entities separate from Castile, until the Nueva Planta Decrees

Nueva Planta decrees

The Nueva Planta decrees were a number of decrees signed between 1707 and 1716 by Philip V—the first Bourbon king of Spain—during and shortly after the end of the War of the Spanish Succession which he won....

of 1707 abolished this autonomy and united Aragon with Castile in a centralised Spanish state. The abolition in the realms of Aragon was completed by 1716, whilst Navarre retained its autonomy until the 1833 territorial division of Spain

1833 territorial division of Spain

The 1833 territorial division of Spain divided Spain into provinces, classified into "historic regions" . on the official web site of the government of the Canary Islands, accessed 2009-12-31...

. It is the only of the Spanish territories whose current status in the Spanish state is legally linked with the old Fuero

Fuero

Fuero , Furs , Foro and Foru is a Spanish legal term and concept.The word comes from Latin forum, an open space used as market, tribunal and meeting place...

s: its Statute of Autonomy

Statute of Autonomy

Nominally, a Statute of Autonomy is a law hierarchically located under the constitution of a country, and over any other form of legislation...

specifically cites them and recognizes their special status, while also recognizing the supremacy of the Spanish Constitution.

A Cortes (or Corts in Catalonia and Valencia) existed in each of Aragon, Catalonia, Valencia and Navarre. It is thought that these legislatures exercised more real power over local affairs than the Castilian Cortes did. Executive councils also existed in each of these realms, which were initially tasked with overseeing the implementation of decisions made by the Cortes. However, throughout the rule of the Habsburg and Bourbon

House of Bourbon

The House of Bourbon is a European royal house, a branch of the Capetian dynasty . Bourbon kings first ruled Navarre and France in the 16th century. By the 18th century, members of the Bourbon dynasty also held thrones in Spain, Naples, Sicily, and Parma...

dynasties the Crown pressed for more centralization, enforcing an unitary position in foreign affairs and empowering Councils outside the control of the Cortes of the several Kingdoms. Thus, the Cortes in Spain did not develop towards a parliamentary system as in the British case, but towards the mentioned rubberstamping of royal decrees. Nevertheless, from time to time the Cortes tried to assert their control over budgetary issues, with varying grades of success.

Cádiz Cortes (1808-14) and the Three Liberal Years (1820-23)

Cádiz CortesCádiz Cortes

The Cádiz Cortes were sessions of the national legislative body which met in the safe haven of Cádiz during the French occupation of Spain during the Napoleonic Wars...

operated as a government in exile. France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

under Napoleon

Napoleon I of France

Napoleon Bonaparte was a French military and political leader during the latter stages of the French Revolution.As Napoleon I, he was Emperor of the French from 1804 to 1815...

had taken control of most of Spain during the Peninsular War

Peninsular War

The Peninsular War was a war between France and the allied powers of Spain, the United Kingdom, and Portugal for control of the Iberian Peninsula during the Napoleonic Wars. The war began when French and Spanish armies crossed Spain and invaded Portugal in 1807. Then, in 1808, France turned on its...

after 1808. The Cortes found refuge in the fortified, coastal city of Cádiz

Cádiz

Cadiz is a city and port in southwestern Spain. It is the capital of the homonymous province, one of eight which make up the autonomous community of Andalusia....

. General Cortes were assembled in Cádiz, but since many provinces could not send representatives due to the French occupation, substitutes were chosen among the people of the city - thus the name Congress of Deputies. Liberal factions dominated the body and pushed through the Spanish Constitution of 1812

Spanish Constitution of 1812

The Spanish Constitution of 1812 was promulgated 19 March 1812 by the Cádiz Cortes, the national legislative assembly of Spain, while in refuge from the Peninsular War...

. Ferdinand VII, however, tossed it aside upon his restoration in 1814 and pursued conservative policies, making the constitution an icon for liberal movements in Spain. Many military coups were attempted, and finally Col. Rafael del Riego

Rafael del Riego

Rafael del Riego y Nuñez was a Spanish general and liberal politician, who played a key role in the outbreak of the Liberal Triennium .-Early life and action in the Peninsular War:...

's one succeeded and forced the King to accept the liberal constitution, which resulted in the Three Liberal Years (Trienio Liberal). The monarch not only did everything he could to obstruct the Government (vetoing nearly every law, for instance), but also asked many powers, including the Holy Alliance

Holy Alliance

The Holy Alliance was a coalition of Russia, Austria and Prussia created in 1815 at the behest of Czar Alexander I of Russia, signed by the three powers in Paris on September 26, 1815, in the Congress of Vienna after the defeat of Napoleon.Ostensibly it was to instill the Christian values of...

, to invade his own country and restore his absolutist powers. He finally received a French army (The Hundred Thousand Sons of St. Louis

The Hundred Thousand Sons of St. Louis

The Hundred Thousand Sons of Saint Louis was the popular name for a French army mobilized by the Bourbon King of France, Louis XVIII to restore King's Ferdinand VII of Spain absolute power of which he had been deprived during the Liberal Triennium. Despite the name, the actual number of troops was...

) which only met resistance in the liberal cities, but easily crushed the National Militia and forced many liberals to exile to, ironically, France. In his second absolutist period up to his death in 1833, Ferdinand VII was more cautious and did not try a full restoration of the Ancien Regime.

The First Republic Parliament (1873–1874)

When the monarchy was overthrown in 1873, the King of Spain was forced into exile. The SenateSpanish Senate

The Senate of Spain is the upper house of Spain's parliament, the . It is made up of 264 members: 208 elected by popular vote, and 56 appointed by the regional legislatures. All senators serve four-year terms, though regional legislatures may recall their appointees at any time.The last election...

was abolished because of its royally appointed nature. A republic was proclaimed and the Congress of Deputies members started writing a Constitution, supposedly that of a federal republic

Federal republic

A federal republic is a federation of states with a republican form of government. A federation is the central government. The states in a federation also maintain the federation...

, with the power of Parliament being nearly supreme (see parliamentary supremacy, although Spain did not use the Westminster system

Westminster System

The Westminster system is a democratic parliamentary system of government modelled after the politics of the United Kingdom. This term comes from the Palace of Westminster, the seat of the Parliament of the United Kingdom....

). However, due to many problems (mainly illiteracy of the people) Spain was not ready to become a republic; after several crises the republic collapsed, and the monarchy was restored in 1874.

The Restoration Cortes (1874–1930)

The regime just after the First Republic is called the Restoration. It was formally a constitutional monarchyConstitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy is a form of government in which a monarch acts as head of state within the parameters of a constitution, whether it be a written, uncodified or blended constitution...

, with the monarch as a rubberstamp to the Cortes' acts but with some reserve powers, such as appointing and dismissing the Prime Minister and appointing senators for the new Senate

Spanish Senate

The Senate of Spain is the upper house of Spain's parliament, the . It is made up of 264 members: 208 elected by popular vote, and 56 appointed by the regional legislatures. All senators serve four-year terms, though regional legislatures may recall their appointees at any time.The last election...

, remade as an elected House.

Soon after the Soviet revolution

October Revolution

The October Revolution , also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution , Red October, the October Uprising or the Bolshevik Revolution, was a political revolution and a part of the Russian Revolution of 1917...

(1917), the Spanish political parties started polarizing, and the left-wing Communist Party (PCE) and Spanish Socialist Workers' Party

Spanish Socialist Workers' Party

The Spanish Socialist Workers' Party is a social-democratic political party in Spain. Its political position is Centre-left. The PSOE is the former ruling party of Spain, until beaten in the elections of November 2011 and the second oldest, exceeded only by the Partido Carlista, founded in...

(PSOE) blamed the Government for supposed election fraud in small towns (caciquismo), which was incorrectly supposed to have been wiped out in the 1900s by the failed regenerationist movement. In the meantime, spiralling violence started with the murders of many leaders by both sides. Deprived of those leaders, the regime entered a general crisis, with extreme police measures which led to a dictatorship (1921–1930) during which the Senate was again abolished.

The Second Republic Parliament (1931–1939)

The dictatorship, now ruled by Admiral Aznar-CabañasJuan Bautista Aznar-Cabañas

Admiral Juan Bautista Aznar-Cabañas was the Prime Minister of Spain from the resignation of Dámaso Berenguer y Fusté on to the deposition of King Alfonso XIII and the proclamation of the Spanish Second Republic on April 14, 1931.In Aznar's government, there were disagreements between absolutist...

, called for local elections. The results were overwhelmingly favorable to the monarchist cause nationally, but most provincial capitals and other sizable cities sided heavily with the republicans. This was interpreted as a victory, as the rural results were under the always-present suspicion of caciquismo and other irregularities while the urban results were harder to influence. The King left Spain, and a Republic was declared on April 14, 1931.

The Second Spanish Republic was established as a presidential republic, with an unicameral

Unicameralism

In government, unicameralism is the practice of having one legislative or parliamentary chamber. Thus, a unicameral parliament or unicameral legislature is a legislature which consists of one chamber or house...

Parliament and a President of the Republic as the Head of State

Head of State

A head of state is the individual that serves as the chief public representative of a monarchy, republic, federation, commonwealth or other kind of state. His or her role generally includes legitimizing the state and exercising the political powers, functions, and duties granted to the head of...

. Among his powers were the appointment and dismissal of the Prime Minister

Prime Minister of Spain

The President of the Government of Spain , sometimes known in English as the Prime Minister of Spain, is the head of Government of Spain. The current office is established under the Constitution of 1978...

, either on the advice of Parliament or just having consulted it before, and a limited power to dissolve the Parliament and call for new elections.

The first term was the constituent term charged with creating the new Constitution

Spanish Constitution of 1931

The Spanish Constitution of 1931 meant the beginning of the Second Spanish Republic, the second period of Spanish history to date in which the election of both the positions of Head of State and Head of government were democratic. It was effective from 1931 until 1939...

, with the ex-monarchist leader Niceto Alcalá Zamora as President of the Republic and the left-wing leader Manuel Azaña

Manuel Azaña

Manuel Azaña Díaz was a Spanish politician. He was the first Prime Minister of the Second Spanish Republic , and later served again as Prime Minister , and then as the second and last President of the Republic . The Spanish Civil War broke out while he was President...

as Prime Minister. The election

Spanish general election, 1931

-Background:General Primo de Rivera, who had run a military dictatorship in Spain since 1923, resigned as head of government in January 1930. There was little support for a return to the pre-1923 system, and the monarchy had lost credibility by backing the military government...

gave a majority in the Cortes and thus, the Government, to a coalition between Azaña's party and the PSOE. A remarkable deed is universal suffrage

Universal suffrage

Universal suffrage consists of the extension of the right to vote to adult citizens as a whole, though it may also mean extending said right to minors and non-citizens...

, allowing women to vote, a provision highly criticized by Socialist leader Indalecio Prieto

Indalecio Prieto

Indalecio Prieto Tuero was a Spanish politician, one of the leading figures of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party in the years before and during the Second Spanish Republic.-Early years:...

, who said the Republic had been backstabbed. Also, for the second time in Spanish history, some regions were granted autonomous governments within the unitary state. Many on the extreme right rose up with General José Sanjurjo

José Sanjurjo

General José Sanjurjo y Sacanell, 1st Marquis of the Rif was a General in the Spanish Army who was one of the chief conspirators in the military uprising that led to the Spanish Civil War.-Early life:...

in 1932 against the Government's social policies, but the coup was quickly defeated.

The elections for the second term were held in 1933

Spanish general election, 1933

Elections to Spain’s legislature, the Cortes Generales, were held on 19 November 1933 for all 473 seats in the unicameral Cortes of the Second Spanish Republic. Since the previous elections of 1931, a new constitution had been ratified, and the franchise extended to more than six million women...

and won by the coalition between the Radical Party (center

Liberalism

Liberalism is the belief in the importance of liberty and equal rights. Liberals espouse a wide array of views depending on their understanding of these principles, but generally, liberals support ideas such as constitutionalism, liberal democracy, free and fair elections, human rights,...

) and the Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas (CEDA) (right

Conservatism

Conservatism is a political and social philosophy that promotes the maintenance of traditional institutions and supports, at the most, minimal and gradual change in society. Some conservatives seek to preserve things as they are, emphasizing stability and continuity, while others oppose modernism...

). Initially, only the Radical Party entered the Government, with the parliamentary support of the CEDA. However, in the middle of the term, several corruption scandals (among them the Straperlo

Straperlo

Straperlo was a business which tried to introduce in Spain in the 1930s a fraudulent roulette which could be controlled electrically with the push of a button...

affair) sunk the Radical Party and the CEDA entered the Government in 1934. This led to uprisings by some leftist parties that were quickly suffocated. In one of them, the left wing government of Catalonia, which had been granted home rule, formally rebelled against the central government, denying its power. This provoked the dissolution of the Generalitat de Catalunya

Generalitat de Catalunya

The Generalitat of Catalonia is the institution under which the autonomous community of Catalonia is politically organised. It consists of the Parliament, the President of the Generalitat of Catalonia and the Government of Catalonia....

and the imprisonment of their leaders. The leftist minority in the Cortes then pressed Alcalá Zamora for a dissolution, arguing that the uprising were the consequence of social rejection of the right-wing government. The President, a former monarchist Minister wary of the authoritarism of the right, dissolved Parliament.

The next election

Spanish general election, 1936

Legislative elections were held in Spain on February 16, 1936. At stake were all 473 seats in the unicameral Cortes Generales. The winners of the 1936 elections were the Popular Front, a left-wing coalition of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party , Republican Left , Esquerra Republicana de...

was held in 1936. It was hotly contested, with all parties converging into three coalitions: the leftist Popular Front

Popular Front (Spain)

The Popular Front in Spain's Second Republic was an electoral coalition and pact signed in January 1936 by various left-wing political organisations, instigated by Manuel Azaña for the purpose of contesting that year's election....

, the right-winged National Front

National Front (Spain)

In Spain, the National Front was a far right political party. The National Front was founded and directed by Blas Piñar as a successor to the Fuerza Nueva...

and a Centre coalition. In the end, the Popular Front won with a small edge in votes over the runner-up National Front, but achieved a solid majority due to the new electoral system introduced by the CEDA government hoping that they would get the edge in votes. The new Parliament then dismissed Alcalá-Zamora and installed Manuel Azaña

Manuel Azaña

Manuel Azaña Díaz was a Spanish politician. He was the first Prime Minister of the Second Spanish Republic , and later served again as Prime Minister , and then as the second and last President of the Republic . The Spanish Civil War broke out while he was President...

in his place. During the third term, the extreme polarisation of the Spanish society was more evident than ever in Parliament, with confrontation reaching the level of death threats. The already bad political and social climate created by the long term left-right confrontation worsened, and many right-wing rebellions were started. Then, in 1936, the Army's failed coup degenerated into the Spanish Civil War

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil WarAlso known as The Crusade among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War among Carlists, and The Rebellion or Uprising among Republicans. was a major conflict fought in Spain from 17 July 1936 to 1 April 1939...

, putting an end to the Second Republic.

The Cortes Generales under the Franco regime (1939–1978)

Attending to his words, Francisco FrancoFrancisco Franco

Francisco Franco y Bahamonde was a Spanish general, dictator and head of state of Spain from October 1936 , and de facto regent of the nominally restored Kingdom of Spain from 1947 until his death in November, 1975...

's intention was to replace the unstable party system

Party system

A party system is a concept in comparative political science concerning the system of government by political parties in a democratic country. The idea is that political parties have basic similarities: they control the government, have a stable base of mass popular support, and create internal...

with an "organic democracy", where the people could participate directly in the nation's politics without any parties.

During the period 1939 to 1942, the legislature of Spain worked essentially without constitution, with the 100 member National Council of the Falange

Falange

The Spanish Phalanx of the Assemblies of the National Syndicalist Offensive , known simply as the Falange, is the name assigned to several political movements and parties dating from the 1930s, most particularly the original fascist movement in Spain. The word means phalanx formation in Spanish....

(similar to the politburo

Politburo

Politburo , literally "Political Bureau [of the Central Committee]," is the executive committee for a number of communist political parties.-Marxist-Leninist states:...

of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union was the only legal, ruling political party in the Soviet Union and one of the largest communist organizations in the world...

or the Grand Council of Fascism

Grand Council of Fascism

The Grand Council of Fascism was the main body of Mussolini's Fascist government in Italy. A body which held and applied great power to control the institutions of government, it was created as a party body in 1923 and became a state body on 9 December 1928....

in Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

) replacing the General Assembly indefinitely. The Organic law

Organic law

An organic or fundamental law is a law or system of laws which forms the foundation of a government, corporation or other organization's body of rules. A constitution is a particular form of organic law for a sovereign state....

of 1942 effectively formed a de facto dictatorship, establishing a unicameral legislature ("Cortes"), made up of more than 400 "representatives" (Spanish: procuradores, singular procurador), with a majority to be appointed from the Falangist Party. The Cortes was un-elected and exercised only symbolic power, with legislative powers vested in the Franco-led government, but there was the possibility of referendums in cases of "serious alterations" of the constitution, in which case only the family heads

Patriarchy

Patriarchy is a social system in which the role of the male as the primary authority figure is central to social organization, and where fathers hold authority over women, children, and property. It implies the institutions of male rule and privilege, and entails female subordination...

(including widows) were allowed to vote. Virtually powerless city councils were appointed through similar procedure.

The Cortes today (1978 Constitution)

The Cortes are a bicameral parliament composed of a lower house (Congreso de los Diputados, congress of deputies) and an upper house (Senado, senate). Although they share legislative power, the Congress holds the power to ultimately override any decision of the Senate by a sufficient majority (usually absolute majority or three-fifths majoritySupermajority

A supermajority or a qualified majority is a requirement for a proposal to gain a specified level or type of support which exceeds a simple majority . In some jurisdictions, for example, parliamentary procedure requires that any action that may alter the rights of the minority has a supermajority...

).

The Congress is composed of 350 deputies (although that figure may change in the future as the constitution establishes a maximum of 400 and a minimum of 300) directly elected by universal suffrage approximately

every four years.

The Senate is partly directly elected (four senators per province as a general rule) and partly appointed (by the legislative assemblies of the autonomous communities

Autonomous communities of Spain

An autonomous community In other languages of Spain:*Catalan/Valencian .*Galician .*Basque . The second article of the constitution recognizes the rights of "nationalities and regions" to self-government and declares the "indissoluble unity of the Spanish nation".Political power in Spain is...

, two for each community and another one for every million inhabitants in their territory). Although the Senate was conceived as a territorial upper house, it has been argued by nationalist parties and the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party

Spanish Socialist Workers' Party

The Spanish Socialist Workers' Party is a social-democratic political party in Spain. Its political position is Centre-left. The PSOE is the former ruling party of Spain, until beaten in the elections of November 2011 and the second oldest, exceeded only by the Partido Carlista, founded in...

that it doesn't accomplish such a task. Proposals to reform the Senate have been discussed for at least ten years as of November 2007.