Discovery Expedition

Encyclopedia

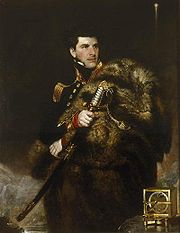

James Clark Ross

Sir James Clark Ross , was a British naval officer and explorer. He explored the Arctic with his uncle Sir John Ross and Sir William Parry, and later led his own expedition to Antarctica.-Arctic explorer:...

voyage sixty years earlier. Organized on a large scale under a joint committee of the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

and the Royal Geographical Society

Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society is a British learned society founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical sciences...

(RGS), the new expedition aimed to carry out scientific research and geographical exploration in what was then largely an untouched continent. It launched the Antarctic careers of many who would become leading figures in the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration

Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration

The Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration defines an era which extended from the end of the 19th century to the early 1920s. During this 25-year period the Antarctic continent became the focus of an international effort which resulted in intensive scientific and geographical exploration, sixteen...

, including Robert Falcon Scott

Robert Falcon Scott

Captain Robert Falcon Scott, CVO was a Royal Navy officer and explorer who led two expeditions to the Antarctic regions: the Discovery Expedition, 1901–04, and the ill-fated Terra Nova Expedition, 1910–13...

who led the expedition, Ernest Shackleton

Ernest Shackleton

Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton, CVO, OBE was a notable explorer from County Kildare, Ireland, who was one of the principal figures of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration...

, Edward Wilson

Edward Adrian Wilson

Edward Adrian Wilson was a notable English polar explorer, physician, naturalist, painter and ornithologist.-Early life:...

, Frank Wild

Frank Wild

Commander John Robert Francis Wild CBE, RNVR, FRGS , known as Frank Wild, was an explorer...

, Tom Crean and William Lashly

William Lashly

William Lashly was a Royal Navy seaman who was a member of both of Robert Falcon Scott's Antarctic expeditions.-Early life:The son of a farm worker, Lashly was born in Hambledon, Hampshire, a village near Portsmouth, England...

.

Its scientific results covered extensive ground in biology

Biology

Biology is a natural science concerned with the study of life and living organisms, including their structure, function, growth, origin, evolution, distribution, and taxonomy. Biology is a vast subject containing many subdivisions, topics, and disciplines...

, zoology

Zoology

Zoology |zoölogy]]), is the branch of biology that relates to the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinct...

, geology

Geology

Geology is the science comprising the study of solid Earth, the rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which it evolves. Geology gives insight into the history of the Earth, as it provides the primary evidence for plate tectonics, the evolutionary history of life, and past climates...

, meteorology

Meteorology

Meteorology is the interdisciplinary scientific study of the atmosphere. Studies in the field stretch back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did not occur until the 18th century. The 19th century saw breakthroughs occur after observing networks developed across several countries...

and magnetism

Magnetism

Magnetism is a property of materials that respond at an atomic or subatomic level to an applied magnetic field. Ferromagnetism is the strongest and most familiar type of magnetism. It is responsible for the behavior of permanent magnets, which produce their own persistent magnetic fields, as well...

. There were important geological and zoological discoveries, including those of the snow-free McMurdo Dry Valleys

McMurdo Dry Valleys

The McMurdo Dry Valleys are a row of snow-free valleys in Antarctica located within Victoria Land west of McMurdo Sound. The region is one of the world's most extreme deserts, and includes many interesting features including Lake Vida and the Onyx River, Antarctica's longest river.-Climate:The Dry...

and the Cape Crozier

Cape Crozier

Cape Crozier is the most easterly point of Ross Island in Antarctica. It was discovered in 1841 during James Clark Ross's expedition with HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, and was named after Francis Crozier, captain of HMS Terror...

Emperor Penguin

Emperor Penguin

The Emperor Penguin is the tallest and heaviest of all living penguin species and is endemic to Antarctica. The male and female are similar in plumage and size, reaching in height and weighing anywhere from . The dorsal side and head are black and sharply delineated from the white belly,...

colony. In the field of geographical exploration, achievements included the discoveries of King Edward VII Land, and the Polar Plateau via the western mountains

Transantarctic Mountains

The three largest mountain ranges on the Antarctic continent are the Transantarctic Mountains , the West Antarctica Ranges, and the East Antarctica Ranges. The Transantarctic Mountains compose a mountain range in Antarctica which extend, with some interruptions, across the continent from Cape Adare...

route. The expedition did not make a serious attempt on the South Pole

South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole or Terrestrial South Pole, is one of the two points where the Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on the surface of the Earth and lies on the opposite side of the Earth from the North Pole...

, its principal southern journey, only travelling to the Farthest South

Farthest South

Farthest South was the term used to denote the most southerly latitudes reached by explorers before the conquest of the South Pole in 1911. Significant steps on the road to the pole were the discovery of lands south of Cape Horn in 1619, Captain James Cook's crossing of the Antarctic Circle in...

mark at a reported 82°17′S.

As a trailbreaker for later ventures, the Discovery Expedition was a landmark in British Antarctic exploration history. After its return home it was celebrated as a success, despite having needed an expensive relief mission to free Discovery and its crew from the ice, and later disputes about the quality of some of its scientific records. It has been asserted that the expedition's main failure was its inability to master the techniques of efficient polar travel using skis and dogs

Dog sled

A dog sled is a sled pulled by one or more sled dogs used to travel over ice and through snow. Numerous types of sleds are used, depending on their function. They can be used for dog sled racing.-History:...

, a legacy that persisted in British Antarctic expeditions throughout the Heroic Age.

Forerunners

Between 1839 and 1843 Royal Naval Captain James Clark Ross, commanding his two ships HMS ErebusHMS Erebus (1826)

HMS Erebus was a Hecla-class bomb vessel designed by Sir Henry Peake and constructed by the Royal Navy in Pembroke dockyard, Wales in 1826. The vessel was named after the dark region in Hades of Greek mythology called Erebus...

and HMS Terror

HMS Terror (1813)

HMS Terror was a bomb vessel designed by Sir Henry Peake and constructed by the Royal Navy in the Davy shipyard in Topsham, Devon. The ship, variously listed as being of either 326 or 340 tons, carried two mortars, one and one .-War service:...

, completed three voyages to the Antarctic continent. During this time he discovered and explored a new sector of the Antarctic that would provide the field of work for many later British expeditions.

Ross Sea

The Ross Sea is a deep bay of the Southern Ocean in Antarctica between Victoria Land and Marie Byrd Land.-Description:The Ross Sea was discovered by James Ross in 1841. In the west of the Ross Sea is Ross Island with the Mt. Erebus volcano, in the east Roosevelt Island. The southern part is covered...

, the Great Ice Barrier (later renamed the Ross Ice Shelf

Ross Ice Shelf

The Ross Ice Shelf is the largest ice shelf of Antarctica . It is several hundred metres thick. The nearly vertical ice front to the open sea is more than 600 km long, and between 15 and 50 metres high above the water surface...

), Ross Island

Ross Island

Ross Island is an island formed by four volcanoes in the Ross Sea near the continent of Antarctica, off the coast of Victoria Land in McMurdo Sound.-Geography:...

, Cape Adare

Cape Adare

Cape Adare is the northeastern most peninsula in Victoria Land, East Antarctica. The cape separates the Ross Sea to the east from the Southern Ocean to the west, and is backed by the high Admiralty Mountains...

, Victoria Land

Victoria Land

Victoria Land is a region of Antarctica bounded on the east by the Ross Ice Shelf and the Ross Sea and on the west by Oates Land and Wilkes Land. It was discovered by Captain James Clark Ross in January 1841 and named after the UK's Queen Victoria...

, McMurdo Sound

McMurdo Sound

The ice-clogged waters of Antarctica's McMurdo Sound extend about 55 km long and wide. The sound opens into the Ross Sea to the north. The Royal Society Range rises from sea level to 13,205 feet on the western shoreline. The nearby McMurdo Ice Shelf scribes McMurdo Sound's southern boundary...

, Cape Crozier

Cape Crozier

Cape Crozier is the most easterly point of Ross Island in Antarctica. It was discovered in 1841 during James Clark Ross's expedition with HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, and was named after Francis Crozier, captain of HMS Terror...

and the twin volcanoes Mount Erebus

Mount Erebus

Mount Erebus in Antarctica is the southernmost historically active volcano on Earth, the second highest volcano in Antarctica , and the 6th highest ultra mountain on an island. With a summit elevation of , it is located on Ross Island, which is also home to three inactive volcanoes, notably Mount...

and Mount Terror

Mount Terror (Antarctica)

Mount Terror is a large shield volcano that forms the eastern part of Ross Island, Antarctica. It has numerous cinder cones and domes on the flanks of the shield and is mostly under snow and ice. It is the second largest of the four volcanoes which make up Ross Island and is somewhat overshadowed...

. He returned to the Barrier several times, hoping to penetrate it, but was unable to do so, achieving his Farthest South

Farthest South

Farthest South was the term used to denote the most southerly latitudes reached by explorers before the conquest of the South Pole in 1911. Significant steps on the road to the pole were the discovery of lands south of Cape Horn in 1619, Captain James Cook's crossing of the Antarctic Circle in...

in a small Barrier inlet at 78°10′, in February 1842. Ross suspected that land lay to the east of the Barrier, but was unable to confirm this.

After Ross there were no recorded voyages into this sector of the Antarctic for fifty years. Then, in January 1895, a Norwegian whaling trip made a brief landing at Cape Adare, the northernmost tip of Victoria Land. Four years later Carsten Borchgrevink, who had participated in that landing, took his own expedition to the region, in the Southern Cross. This expedition was financed by a donation of £35,000 from British publishing magnate Sir George Newnes

George Newnes

Sir George Newnes, 1st Baronet was a publisher and editor in England.-Background and education:...

, on condition that the venture be called the "British Antarctic Expedition". Borchgrevink landed at Cape Adare in February 1899, erected a small hut, and spent the 1899 winter there. The following summer he sailed south, landing at Ross's inlet on the Barrier. A party of three then sledged southward on the Barrier surface, and reached a new Furthest South at 78°50′.

The Discovery Expedition was planned during a surge of international interest in the Antarctic regions at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. A German expedition under Erich von Drygalski

Erich von Drygalski

Erich Dagobert von Drygalski was a German geographer, geophysicist and polar scientist, born in Königsberg, Province of Prussia....

was leaving at about the same time as Discovery, to explore the sector of the continent south of the Indian Ocean. The Swedish explorer Otto Nordenskiöld

Otto Nordenskiöld

Nils Otto Gustaf Nordenskjöld was a Finnish and Swedish geologist, geographer, and polar explorer.-Biography:...

was leading an expedition to Graham Land

Graham Land

Graham Land is that portion of the Antarctic Peninsula which lies north of a line joining Cape Jeremy and Cape Agassiz. This description of Graham Land is consistent with the 1964 agreement between the British Antarctic Place-names Committee and the US Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names, in...

, and a French expedition under Jean-Baptiste Charcot was going to the Antarctic Peninsula

Antarctic Peninsula

The Antarctic Peninsula is the northernmost part of the mainland of Antarctica. It extends from a line between Cape Adams and a point on the mainland south of Eklund Islands....

. Finally, the Scottish scientist William Speirs Bruce

William Speirs Bruce

William Speirs Bruce was a London-born Scottish naturalist, polar scientist and oceanographer who organised and led the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition to the South Orkney Islands and the Weddell Sea. Among other achievements, the expedition established the first permanent weather station...

was leading a scientific expedition to the Weddell Sea

Weddell Sea

The Weddell Sea is part of the Southern Ocean and contains the Weddell Gyre. Its land boundaries are defined by the bay formed from the coasts of Coats Land and the Antarctic Peninsula. The easternmost point is Cape Norvegia at Princess Martha Coast, Queen Maud Land. To the east of Cape Norvegia is...

.

Royal Navy, Markham and Scott

Under the influence of John BarrowSir John Barrow, 1st Baronet

Sir John Barrow, 1st Baronet, FRS, FRGS was an English statesman.-Career:He was born the son of Roger Barrow in the village of Dragley Beck, in the parish of Ulverston then in Lancashire, now in Cumbria...

, Second Secretary to the Admiralty

Admiralty

The Admiralty was formerly the authority in the Kingdom of England, and later in the United Kingdom, responsible for the command of the Royal Navy...

, polar exploration had become the province of the peacetime Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

after the Napoleonic War. Naval interest diminished after the disappearance in 1845 of the Franklin expedition

Franklin's lost expedition

Franklin's lost expedition was a doomed British voyage of Arctic exploration led by Captain Sir John Franklin that departed England in 1845. A Royal Navy officer and experienced explorer, Franklin had served on three previous Arctic expeditions, the latter two as commanding officer...

, and the many fruitless searches that followed. After the problems encountered by the 1874–76 North Pole expedition led by George Nares

George Nares

Vice-Admiral Sir George Strong Nares KCB FRS was a British naval officer and Arctic explorer. He commanded both the Challenger Expedition and the British Arctic Expedition, and was highly thought of a leader and a scientific explorer...

, and Nares's own declaration that the North Pole was "impracticable", the Admiralty

Admiralty

The Admiralty was formerly the authority in the Kingdom of England, and later in the United Kingdom, responsible for the command of the Royal Navy...

decided that further polar quests would be dangerous, expensive and futile.

However, the Royal Geographical Society

Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society is a British learned society founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical sciences...

's Secretary (and later President) Sir Clements Markham was a former naval man who had served on one of the Franklin relief expeditions in 1851. He had also accompanied Nares for part of that expedition, and became a firm advocate for the navy's resuming its historic role. An opportunity to further this ambition arose in November 1893, when the prominent biologist Sir John Murray

John Murray (oceanographer)

Sir John Murray KCB FRS FRSE FRSGS was a pioneering Scottish oceanographer, marine biologist and limnologist.-Early life:...

, who had visited Antarctic waters as a biologist with the Challenger Expedition

Challenger expedition

The Challenger expedition of 1872–76 was a scientific exercise that made many discoveries to lay the foundation of oceanography. The expedition was named after the mother vessel, HMS Challenger....

in the 1870s, addressed the RGS. Murray presented a paper entitled "The Renewal of Antarctic Exploration", and called for a full-scale expedition for the benefit of British science. This was strongly supported, both by Markham and by the country's premier scientific body, the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

. A joint committee of the two Societies was established to decide the form which the expedition should take. Markham's vision of a full-blown naval affair after the style of Ross or Franklin was opposed by sections of the joint committee, but his tenacity was such that the expedition was eventually moulded largely to his wishes. His cousin and biographer later wrote that the expedition was "the creation of his brain, the product of his persistent energy".

It had long been Markham's practice to take note of promising young naval officers who might later be suitable for polar responsibilities, should the opportunity arise. He had first observed Midshipman

Midshipman

A midshipman is an officer cadet, or a commissioned officer of the lowest rank, in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, India, Pakistan, Singapore, Sri Lanka and Kenya...

Robert Falcon Scott in 1887, while the latter was serving with HMS Rover

HMS Rover (1874)

HMS Rover was an 18-gun iron screw corvette of the Royal Navy. She was built by the Thames Ironworks and Shipbuilding Company, Leamouth, London to a design by Edward James Reed and launched in 1874.-Design and construction:...

in St Kitts, and had remembered him. Thirteen years later, Scott, by now a Torpedo Lieutenant

Lieutenant

A lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer in many nations' armed forces. Typically, the rank of lieutenant in naval usage, while still a junior officer rank, is senior to the army rank...

on HMS Majestic

HMS Majestic (1895)

HMS Majestic was a Majestic-class predreadnought battleship of the Royal Navy.-Technical characteristics:HMS Majestic was laid down at Portsmouth Dockyard on 5 February 1894 and launched on 31 January 1895...

, was looking for a path to career advancement, and a chance meeting with Sir Clements in London led him to apply for the leadership of the expedition. Scott had long been in Markham's mind, though by no means always his first choice, but other favoured candidates had either become in his view too old, or were no longer available. With Markham's determined backing, Scott's appointment was secured by 25 May 1900, followed swiftly by his promotion to Commander

Commander

Commander is a naval rank which is also sometimes used as a military title depending on the individual customs of a given military service. Commander is also used as a rank or title in some organizations outside of the armed forces, particularly in police and law enforcement.-Commander as a naval...

.

Science versus adventure

The command structure of the expedition had still to be settled. Markham had been determined from the beginning that its overall leader should be a naval officer, not a scientist. Scott, writing to Markham after his appointment, reiterated that he "must have complete command of the ship and landing parties", and insisted on being consulted over all future appointments. However, the Joint Committee had, with Markham's acquiescence, secured the appointment of John Walter GregoryJohn Walter Gregory

John Walter Gregory, FRS, was a British geologist and explorer, known principally for his work on glacial geology and on the geography and geology of Australia and East Africa.-Early life:...

, Professor of Geology at the University of Melbourne

University of Melbourne

The University of Melbourne is a public university located in Melbourne, Victoria. Founded in 1853, it is the second oldest university in Australia and the oldest in Victoria...

and former assistant geologist at the British Museum

British Museum

The British Museum is a museum of human history and culture in London. Its collections, which number more than seven million objects, are amongst the largest and most comprehensive in the world and originate from all continents, illustrating and documenting the story of human culture from its...

, as the expedition's scientific director. Gregory's view, endorsed by the Royal Society faction of the Joint Committee, was that the organisation and command of the land party should be in his hands: "...The Captain would be instructed to give such assistance as required in dredging, tow-netting etc., to place boats where required at the disposal of the scientific staff." In the dispute that followed, Markham argued that Scott's command of the whole expedition must be total and unambiguous, and Scott himself was insistent on this to the point of resignation. Markham's and Scott's view prevailed, and Gregory resigned, saying that the scientific work should not be "subordinated to naval adventure".

This controversy soured relations between the Societies, which lingered after the conclusion of the expedition and was reflected in criticism of the extent and quality of some of the published results. Markham claimed that his insistence on a naval command was primarily a matter of tradition and style, rather than indicating disrespect for science. He had made clear his belief that, on its own, the mere attainment of higher latitude than someone else was "unworthy of support."

Personnel

Charles Royds

Vice-Admiral Sir Charles William Rawson Royds KBE CMG ADC FRGS was a career Royal Navy officer who later served as Assistant Commissioner "A" of the London Metropolitan Police from 1926 to 1931...

, and later allowed Michael Barne

Michael Barne

Michael Barne was an officer of the 1901-04 Discovery Expedition and was the last survivor of the expedition.-Early life:...

and Reginald Skelton

Reginald William Skelton

Reginald William Skelton was the Chief Engineer and Official Photographer of the 1901-1904 Discovery Expedition to Antarctica.-Early life:...

to join the expedition. The remaining officers were from the Merchant Marine, including Albert Armitage

Albert Armitage

Albert Borlase Armitage was a Scottish explorer of Antarctica and captain in the Royal Navy.He was first a member of the Jackson-Harmsworth Expedition exploring Franz Josef Land...

, the second-in-command, who had experience with the Jackson–Harmsworth Arctic expedition, 1894–97

Frederick George Jackson

Frederick George Jackson , British Arctic explorer, was educated at Denstone College and Edinburgh University.-Biography:...

, and Ernest Shackleton

Ernest Shackleton

Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton, CVO, OBE was a notable explorer from County Kildare, Ireland, who was one of the principal figures of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration...

, designated Third Officer

Third Mate

A Third Mate or Third Officer is a licensed member of the deck department of a merchant ship. The third mate is a watchstander and customarily the ship's safety officer and fourth-in-command...

in charge of holds, stores and provisions, and responsible for arranging the entertainments. The Admiralty also released around twenty petty officers

Petty Officer

A petty officer is a non-commissioned officer in many navies and is given the NATO rank denotion OR-6. They are equal in rank to sergeant, British Army and Royal Air Force. A Petty Officer is superior in rank to Leading Rate and subordinate to Chief Petty Officer, in the case of the British Armed...

and seamen, the rest of the crew being from the merchant service, or from civilian employment. Among the lower deck complement were some who became Antarctic veterans, including Frank Wild

Frank Wild

Commander John Robert Francis Wild CBE, RNVR, FRGS , known as Frank Wild, was an explorer...

, William Lashly

William Lashly

William Lashly was a Royal Navy seaman who was a member of both of Robert Falcon Scott's Antarctic expeditions.-Early life:The son of a farm worker, Lashly was born in Hambledon, Hampshire, a village near Portsmouth, England...

, Thomas Crean (who joined the expedition following the desertion of a seaman in New Zealand), Edgar Evans

Edgar Evans

Petty Officer Edgar Evans was a member of the Polar Party on Robert Falcon Scott's companions on his ill-fated Terra Nova Expedition to the South Pole in 1911–1912...

and Ernest Joyce

Ernest Joyce

Ernest Edward Mills Joyce AM was a Royal Naval seaman and explorer who participated in four Antarctic expeditions during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, early in the early 20th century. He served under both Robert Falcon Scott and Ernest Shackleton...

. Although the expedition was not a formal Navy project, Scott proposed to run the expedition on naval lines, and secured the crew's voluntary agreement to work under the Naval Discipline Act.

The scientific team was inexperienced. Dr George Murray, Gregory's successor as chief scientist, was due to travel only as far as Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

(in fact he left the ship at Cape Town

Cape Town

Cape Town is the second-most populous city in South Africa, and the provincial capital and primate city of the Western Cape. As the seat of the National Parliament, it is also the legislative capital of the country. It forms part of the City of Cape Town metropolitan municipality...

), using the voyage to train the scientists, but with no part to play in the detailed work of the expedition. The only scientist with previous Antarctic experience was Louis Bernacchi

Louis Bernacchi

Louis Charles Bernacchi , a physicist and astronomer, is best known for his role in several expeditions to the Antarctic.-Early life:...

, who had been with Borchgrevink as magnetic observer and meteorologist. The geologist, Hartley Ferrar, was a 22-year-old recent Cambridge graduate who Markham thought "might be made into a man." Marine biologist Thomas Vere Hodgson

Thomas Vere Hodgson

Thomas Vere Hodgson was a biologist aboard the H.M.S. Discovery during the Discovery Expedition of 1901–1904, known by the nickname Muggins. He pursued his interest in marine biology initially in his spare time, but eventually found work at the Marine Biological Station in Plymouth...

, from Plymouth Museum, was a more mature figure, as was the senior of the two doctors, Reginald Koettlitz

Reginald Koettlitz

Reginald Koettlitz was a British physician and polar explorer. He participated in the Jackson-Harmsworth Expedition to Franz Josef Land and in the Discovery Expedition to Antarctica....

, who, at 39, was the oldest member of the expedition. He, like Armitage, had been with the Jackson–Harmsworth expedition. The junior doctor and zoologist was Edward Wilson

Edward Adrian Wilson

Edward Adrian Wilson was a notable English polar explorer, physician, naturalist, painter and ornithologist.-Early life:...

, who became close to Scott and provided the qualities of calmness, patience and detachment that the captain reportedly lacked.

Finance

The total cost of the expedition was estimated at £90,000 (2009 equivalent about £7.25 million), of which £45,000 was offered by the British Government provided that the two Societies could raise a matching sum. They achieved this, thanks largely to a donation of £25,000 from wealthy RGS member Sir Llewellyn W. LongstaffLlewellyn W. Longstaff

Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Llewellyn Wood Longstaff OBE was an English industrialist and member of the Royal Geographical Society. He is best known for being the chief private-sector patron and financial angel of the Discovery Expedition to the Antarctic.-Antarctic patron:Llewellyn Longstaff was born...

. The RGS itself contributed £8,000, its largest single contribution to any expedition to that date, and £5,000 came from Alfred Harmsworth, later Lord Northcliffe, who had earlier financed the Jackson-Harmsworth expedition to the Arctic, 1894–97. The rest was raised from smaller donations. The expedition also benefited from significant commercial sponsorship: Colman's

Colman's

Colman's is a UK manufacturer of mustard and various other sauces, based at Carrow, in Norwich, Norfolk. Presently an operational division of the multinational Unilever company, Colman's is one of the oldest existing food brands, famous for a limited range of products, almost all varieties of...

provided mustard and flour, Cadbury's

Cadbury Schweppes

Cadbury is a confectionery company owned by Kraft Foods and is the industry's second-largest globally after Mars, Incorporated. Headquartered in Uxbridge, London, United Kingdom, the company operates in more than 50 countries worldwide....

gave 3,500 lb (1,600 kg) of chocolate, Jaeger gave a 40% discount on special clothing, and Bird's

Bird's Custard

Bird's Custard is the original version of what is known generically as custard powder. It is a cornflour -based powder which thickens to form a custard-like sauce when mixed with milk and heated to a sufficient temperature...

(baking powders), Bovril

Bovril

Bovril is the trademarked name of a thick, salty meat extract, developed in the 1870s by John Lawson Johnston and sold in a distinctive, bulbous jar. It is made in Burton upon Trent, Staffordshire, owned and distributed by Unilever UK....

(beef extract) and others all made significant contributions.

Ship

George Nares

Vice-Admiral Sir George Strong Nares KCB FRS was a British naval officer and Arctic explorer. He commanded both the Challenger Expedition and the British Arctic Expedition, and was highly thought of a leader and a scientific explorer...

expedition, and certain features of this older vessel were incorporated into the design of the new ship. She was launched by Lady Markham on 21 March 1901 as SS Discovery (the Royal Research Ship designation was acquired in the 1920s).

As she was not a Royal Naval vessel the Admiralty would not allow Discovery to fly the White Ensign

White Ensign

The White Ensign or St George's Ensign is an ensign flown on British Royal Navy ships and shore establishments. It consists of a red St George's Cross on a white field with the Union Flag in the upper canton....

. She eventually sailed under the Merchant Shipping Act, flying the RGS house flag and the Blue Ensign

Blue Ensign

The Blue Ensign is a flag, one of several British ensigns, used by certain organisations or territories associated with the United Kingdom. It is used either plain, or defaced with a badge or other emblem....

and burgee of the Royal Harwich Yacht Club.

Objectives

The Discovery Expedition, like those of Ross and Borchgrevink before it, was to work in the Ross Sea sector of Antarctica. Other areas of the continent had been considered, but the principle followed was that "in going for the unknown they should start from the known".The two main objectives of the expedition were summarised in the joint committee's "Instructions to the Commander" as: "to determine, as far as possible, the nature, condition and extent of that portion of the south polar lands which is included in the scope of your expedition", and "to make a magnetic survey in the southern regions to the south of the fortieth parallel and to carry out meteorological, oceanographic, geological, biological and physical investigations and researches". The instructions stipulated that "neither of these objectives was to be sacrificed to the other".

The instructions concerning the geographical objective became more specific: "The chief points of geographical interest are [...] to explore the ice barrier of Sir James Ross to its eastern extremity; to discover the land which was believed by Ross to flank the barrier to the eastward, or to ascertain that it does not exist [...] If you should decide to winter in the ice...your efforts as regards geographical exploration should be directed to [...] an advance to the western mountains, an advance to the south, and an exploration of the volcanic region".

First year

Outward journey

Discovery left CardiffCardiff

Cardiff is the capital, largest city and most populous county of Wales and the 10th largest city in the United Kingdom. The city is Wales' chief commercial centre, the base for most national cultural and sporting institutions, the Welsh national media, and the seat of the National Assembly for...

on 6 August 1901, and arrived in New Zealand

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

via Cape Town on 29 November after a detour below 40°S for a magnetic survey. After three weeks of final preparation she was ready for the journey south. On 21 December, as the ship was leaving Lyttelton Harbour

Lyttelton Harbour

Lyttelton Harbour is one of two major inlets in Banks Peninsula, on the coast of Canterbury, New Zealand. The other is Akaroa Harbour.Approximately 15 km in length from its mouth to Teddington, the harbour was formed from a series of ancient volcanic eruptions that created a caldera, the...

to the cheers of large crowds, a young Able Seaman, Charles Bonner, fell to his death from the top of the mainmast, which he had climbed so as to return the crowd's applause. He was buried at Port Chalmers

Port Chalmers

Port Chalmers is a suburb and the main port of the city of Dunedin, New Zealand, with a population of 3,000. Port Chalmers lies ten kilometres inside Otago Harbour, some 15 kilometres northeast from Dunedin's city centre....

, two days later.

Discovery then sailed south, arriving at Cape Adare on 9 January 1902. After a brief landing and examination of the remains of Borchgrevink's camp, the ship continued southwards along the Victoria Land

Victoria Land

Victoria Land is a region of Antarctica bounded on the east by the Ross Ice Shelf and the Ross Sea and on the west by Oates Land and Wilkes Land. It was discovered by Captain James Clark Ross in January 1841 and named after the UK's Queen Victoria...

coast. At McMurdo Sound

McMurdo Sound

The ice-clogged waters of Antarctica's McMurdo Sound extend about 55 km long and wide. The sound opens into the Ross Sea to the north. The Royal Society Range rises from sea level to 13,205 feet on the western shoreline. The nearby McMurdo Ice Shelf scribes McMurdo Sound's southern boundary...

Discovery turned eastward, touching land again at Cape Crozier

Cape Crozier

Cape Crozier is the most easterly point of Ross Island in Antarctica. It was discovered in 1841 during James Clark Ross's expedition with HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, and was named after Francis Crozier, captain of HMS Terror...

where a pre-arranged message point was set up so that relief ships would be able to locate the expedition. She then followed the Barrier to its eastern extremity where, on 30 January, the land predicted by Ross was confirmed, and named King Edward VII Land.

On 4 February, Scott landed on the Barrier and unpacked an observation balloon which he had acquired for aerial surveys. Scott climbed aboard and rapidly ascended to above 600 feet (180 m) in the firmly tethered balloon. Shackleton followed with a second flight. All either could see was unending Barrier surface. Wilson privately thought the flights "perfect madness".

Winter Quarters Bay

Discovery then proceeded westward in search of permanent quarters. On 8 February she entered McMurdo Sound and later that day anchored in a spot near its southern limit which was afterwards christened Winter Quarters BayWinter Quarters Bay

Winter Quarters Bay is a small cove of McMurdo Sound, Antarctica, located 2,200 miles due south of New Zealand at 77°50'S. The harbor is the southern-most port in the Southern Ocean and features a floating ice pier for summer cargo operations. The bay is approximately 250m wide and long, with a...

. Wilson wrote: "We all realized our extreme good fortune in being led to such a winter quarter as this, safe for the ship, with perfect shelter from all ice pressure." Stoker Lashly, however, thought it looked "a dreary place." Work began ashore with the erection of the expedition's huts on a rocky peninsula designated Hut Point. Scott had decided that the expedition should continue to live and work aboard ship, and he allowed Discovery to be frozen into the sea ice, leaving the main hut to be used as a storeroom and shelter.

Manhauling

Manhauling, often expressed as man-hauling, means the pulling forward of sledges, trucks or other load-carrying vehicles by human power unaided by animals or machines...

. The dangers of the unfamiliar conditions were confirmed when, on 11 March, a party returning from an attempted journey to Cape Crozier became stranded on an icy slope during a blizzard. In their attempts to find safer ground, one of the group, Able Seaman

Able seaman

An able seaman is an unlicensed member of the deck department of a merchant ship. An AB may work as a watchstander, a day worker, or a combination of these roles.-Watchstander:...

George Vince, slid over the edge of a cliff and was killed. His body was never recovered; a cross with a simple inscription, erected in his memory, still stands at the summit of the Hut Point promontory.

During the winter months of May–August the scientists were busy in their laboratories, while elsewhere equipment and stores were prepared for the next season's work. For relaxation there were amateur theatricals, and educational activities in the form of lectures. A newspaper, the South Polar Times, was edited by Shackleton. Outside pursuits did not cease altogether; there was football on the ice, and the schedule of magnetic and meteorological observations was maintained. As winter ended, trial sledge runs resumed, to test equipment and rations in advance of the planned southern journey which Scott, Wilson and Shackleton were to undertake. Meanwhile, a party under Royds travelled to Cape Crozier to leave a message at the post there, and discovered an Emperor Penguin

Emperor Penguin

The Emperor Penguin is the tallest and heaviest of all living penguin species and is endemic to Antarctica. The male and female are similar in plumage and size, reaching in height and weighing anywhere from . The dorsal side and head are black and sharply delineated from the white belly,...

colony. Another group, under Armitage, reconnoitred in the mountains to the west, returning in October with the expedition's first symptoms of scurvy

Scurvy

Scurvy is a disease resulting from a deficiency of vitamin C, which is required for the synthesis of collagen in humans. The chemical name for vitamin C, ascorbic acid, is derived from the Latin name of scurvy, scorbutus, which also provides the adjective scorbutic...

. Armitage later blamed the outbreak on Scott's "sentimental objection" to the slaughter of animals for fresh meat. The entire expedition's diet was quickly revised, and the trouble was thereafter contained.

Southern journey

Scott, Wilson and Shackleton left on 2 November 1902 with dogs and supporting parties. Their goal was "to get as far south in a straight line on the Barrier ice as we can, reach the Pole if possible, or find some new land". The first significant milestone was passed on 11 November, when a supporting party passed Borchgrevink's Farthest SouthFarthest South

Farthest South was the term used to denote the most southerly latitudes reached by explorers before the conquest of the South Pole in 1911. Significant steps on the road to the pole were the discovery of lands south of Cape Horn in 1619, Captain James Cook's crossing of the Antarctic Circle in...

record of 78°50′. However, the lack of skill with dogs was soon evident, and progress was slow. After the support parties had returned, on 15 November, Scott's group began relaying their loads (taking half loads forward, then returning for the other half), thus travelling three miles for every mile of southward progress. Mistakes had been made with the dogs' food, and as the dogs grew weaker, Wilson was forced to kill the weakest as food for the others. The men, too, were struggling, afflicted by snow blindness

Snow blindness

Photokeratitis or ultraviolet keratitis is a painful eye condition caused by exposure of insufficiently protected eyes to the ultraviolet rays from either natural or artificial sources. Photokeratitis is akin to a sunburn of the cornea and conjunctiva, and is not usually noticed until several...

, frostbite

Frostbite

Frostbite is the medical condition where localized damage is caused to skin and other tissues due to extreme cold. Frostbite is most likely to happen in body parts farthest from the heart and those with large exposed areas...

and symptoms of early scurvy, but they continued southwards in line with the mountains to the west. Christmas Day was celebrated with double rations, and a Christmas pudding that Shackleton has kept for the occasion, hidden with his socks. On 30 December 1902, without having left the Barrier, they reached their Furthest South at 82°17′S. Troubles multiplied on the home journey, as the remaining dogs died and Shackleton collapsed with scurvy. Wilson's diary entry for 14 January 1903 acknowledged that "we all have slight, though definite symptoms of scurvy". Scott and Wilson struggled on, with Shackleton, who was unable to pull, walking alongside and occasionally carried on the sledge. The party eventually reached the ship on 3 February 1903 after covering 960 miles (1,545 km) including relays, in 93 days' travel at a daily average of just over 10 miles (16.1 km).

Arrival of relief ship

During the southern party's absence the relief ship MorningSY Morning

SY Morning is most famous for her role as a relief vessel to Scott's British National Antarctic Expedition . She made two voyages to the Antarctic to resupply the expedition.-Acquisition for the British National Antarctic Expedition:...

arrived, bringing fresh supplies. The expedition's organisers had assumed that the Discovery would be free from the ice in early 1903, enabling Scott to carry out further seaborne exploration and survey work before winter set in. It was intended that Discovery would return to New Zealand in March or April, then home to England via the Pacific, continuing its magnetic survey en route. Morning would provide any assistance that Scott might require during this period.

This plan was frustrated, as Discovery remained firmly icebound. Markham had privately anticipated this, and Mornings captain, William Colbeck, was carrying a secret letter to Scott authorising another year in the ice. This now being inevitable, the relief ship provided an opportunity for some of the party to return home. Among these, against his will, was the convalescent Shackleton, who Scott decided "ought not to risk further hardships in his present state of health". Stories of a Scott-Shackleton rift date from this point, or from a supposed falling-out during the southern journey which had provoked an angry exchange of words. Some of these details were supplied by Armitage, whose relationship with Scott had broken down and who, after Scott, Wilson and Shackleton were all dead, chose to reveal details which tended to show Scott in a poor light. Other evidence indicates that Scott and Shackleton remained on generally good terms for some while; Shackleton met the expedition on its return home in 1904, and later wrote a very cordial letter to Scott.

Second year

After the 1903 winter had passed, Scott prepared for the second main journey of the expedition: an ascent of the western mountains and exploration of the interior of Victoria Land. Armitage's reconnaissance party of the previous year had pioneered a route up to altitude 8900 feet (2,712.7 m) before returning, but Scott wished to march west from this point, if possible to the location of the South Magnetic PoleSouth Magnetic Pole

The Earth's South Magnetic Pole is the wandering point on the Earth's surface where the geomagnetic field lines are directed vertically upwards...

. After a false start due to faulty sledges, a party including Scott, Lashly and Edgar Evans set out from Discovery on 26 October 1903.

Ferrar Glacier

The Ferrar Glacier is an Antarctic glacier about long, flowing from the plateau of Victoria Land west of the Royal Society Range to New Harbour in McMurdo Sound. The glacier makes a right turn northeast of Knobhead, where it is apposed, i.e., joined in Siamese-twin fashion, to Taylor Glacier...

, which they named after the party's geologist Ferrar, they reached a height of 7000 feet (2,133.6 m) before being held in camp for a week by blizzards. This prevented them from reaching the glacier summit until 13 November. They then marched on beyond Armitage's furthest point, discovered the Polar Plateau and became the first party to travel on it. After the return of geological and supporting parties, Scott, Evans and Lashly continued westward across the featureless plain for another eight days, covering a distance of about 150 miles to reach their most westerly point on 30 November. Having lost their navigational tables in a gale during the glacier ascent, they did not know exactly where they were, and had no landmarks to help them fix a position. The return journey to the Ferrar Glacier was undertaken in conditions which limited them to no more than a mile an hour, with supplies running low and dependent on Scott's rule of thumb navigation. On the descent of the glacier Scott and Evans survived a potentially fatal fall into a crevasse, before the discovery of a snow-free area or dry valley

McMurdo Dry Valleys

The McMurdo Dry Valleys are a row of snow-free valleys in Antarctica located within Victoria Land west of McMurdo Sound. The region is one of the world's most extreme deserts, and includes many interesting features including Lake Vida and the Onyx River, Antarctica's longest river.-Climate:The Dry...

, a rare Antarctic phenomenon. Lashly described the dry valley as "a splendid place for growing spuds". The party reached Discovery on 24 December, after a round trip of seven hundred miles covered in 59 days. Their daily average of over 14 miles on this man-hauling journey was significantly better than that achieved with dogs on the previous season's southern journey, a fact which further strengthened Scott's prejudices against dogs. Polar historian David Crane calls the western journey "one of the great journeys of polar history".

Several other journeys were completed during Scott's absence. Royds and Bernacchi travelled for 31 days on the Barrier in a SE direction, observing its uniformly flat character and making further magnetic readings. Another party had explored the Koettlitz Glacier

Koettlitz Glacier

The Koettlitz Glacier is a large Antarctic glacier lying west of Mount Morning and Mount Discovery, flowing from the vicinity of Mount Cocks northeastward between Brown Peninsula and the mainland into the ice shelf of McMurdo Sound....

to the south-west, and Wilson had travelled to Cape Crozier to observe the Emperor Penguin colony at close quarters.

Second relief expedition

Scott had hoped on his return to find Discovery free from the ice, but she remained held fast. Work had begun with ice saws, but after 12 days' labour only two short parallel cuts of 450 feet (137.2 m) had been carved, with the ship still 20 miles (32.2 km) from open water. On 5 January 1904 the relief ship Morning returned, this time with a second ship, the Terra NovaTerra Nova (ship)

The Terra Nova was built in 1884 for the Dundee whaling and sealing fleet. She worked for 10 years in the annual seal fishery in the Labrador Sea, proving her worth for many years before she was called upon for expedition work.Terra Nova was ideally suited to the polar regions...

. Colbeck was carrying firm instructions from the Admiralty that, if Discovery could not be freed by a certain date she was to be abandoned and her complement brought home on the two relief ships. This ultimatum resulted from Markham's dependence on the Treasury for meeting the costs of this second relief expedition, since the expedition's coffers were empty. The Admiralty would foot the bill only on their own terms. The deadline agreed between the three captains was 25 February, and it became a race against time for the relief vessels to reach Discovery, still held fast at Hut Point. As a precaution Scott began the transfer of his scientific specimens to the other ships. Explosives were used to break up the ice, and the sawing parties resumed work, but although the relief ships were able to edge closer, by the end of January Discovery remained icebound, two miles (approx. 3 km) from the rescuers. On 10 February Scott accepted that he would have to abandon her, but on 14 February most of the ice suddenly broke up, and Morning and Terra Nova were at last able to sail alongside Discovery. A final explosive charge removed the remaining ice on 16 February, and the following day, after a last scare when she became temporarily grounded on a shoal, Discovery began the return journey to New Zealand.

Homecoming

Captain (naval)

Captain is the name most often given in English-speaking navies to the rank corresponding to command of the largest ships. The NATO rank code is OF-5, equivalent to an army full colonel....

, and invited to Balmoral Castle

Balmoral Castle

Balmoral Castle is a large estate house in Royal Deeside, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. It is located near the village of Crathie, west of Ballater and east of Braemar. Balmoral has been one of the residences of the British Royal Family since 1852, when it was purchased by Queen Victoria and her...

to meet King Edward VII, who invested him as a Commander of the Royal Victorian Order

Royal Victorian Order

The Royal Victorian Order is a dynastic order of knighthood and a house order of chivalry recognising distinguished personal service to the order's Sovereign, the reigning monarch of the Commonwealth realms, any members of her family, or any of her viceroys...

(CVO). He also received a cluster of medals and awards from overseas, including the French Légion d'honneur

Légion d'honneur

The Legion of Honour, or in full the National Order of the Legion of Honour is a French order established by Napoleon Bonaparte, First Consul of the Consulat which succeeded to the First Republic, on 19 May 1802...

. Polar Medal

Polar Medal

The Polar Medal is a medal awarded by the Sovereign of the United Kingdom. It was instituted in 1857 as the Arctic Medal and renamed the Polar Medal in 1904.-History:...

s and promotions were given to other officers and crew members.

The main geographical results of the expedition were the discovery of King Edward VII Land; the ascent of the western mountains and the discovery of the Polar Plateau; the first sledge journey on the plateau; the Barrier journey to a Furthest South of 82°17′S. The island nature of Ross Island was established, the Transantarctic Mountains were charted to 83°S, and the positions and heights of more than 200 individual mountains were calculated. Many other features and landmarks were also identified and named, and there was extensive coastal survey work.

There were also discoveries of major scientific importance. These included the snow-free Dry Valleys in the western mountains, the Emperor Penguin colony at Cape Crozier, scientific evidence that the Ice Barrier was a floating ice shelf, and a leaf fossil discovered by Ferrar which helped to establish Antarctica's relation to the Gondwana

Gondwana

In paleogeography, Gondwana , originally Gondwanaland, was the southernmost of two supercontinents that later became parts of the Pangaea supercontinent. It existed from approximately 510 to 180 million years ago . Gondwana is believed to have sutured between ca. 570 and 510 Mya,...

super-continent. Thousands of geological and biological specimens had been collected and new marine species identified. The location of the South Magnetic Pole had been calculated with reasonable accuracy.

A general endorsement of the scientific results from the navy's Chief Hydrographer (and former Scott opponent) Sir William Wharton

William Wharton (hydrographer)

Admiral Sir William James Lloyd Wharton KCB FRS was a British admiral and Hydrographer of the Navy.-Early life:He was born in London, the second son of Robert Wharton, County Court Judge of York. He was educated at Barney's Academy, Gosport and the Royal Naval Academy.-Royal Navy service:He joined...

was encouraging. However, when the meteorological data were published their accuracy was disputed within the scientific establishment, including by the President of the Physical Society of London, Dr Charles Chree

Charles Chree

Charles Chree was a British physicist.He was born in Lintrathen, Forfarshire, Scotland and educated at the Grammar School, Old Aberdeen, the University of Aberdeen where he graduated MA in 1879 and the University of Cambridge...

. Scott defended his team's work, while privately acknowledging that Royds's paperwork in this field had been "dreadfully slipshod".

The failure to avoid scurvy was the result of medical ignorance of the causes of the disease rather than the fault of the expedition. At that time it was known that a fresh meat diet could provide a cure, but not that lack of it was a cause. Thus, fresh seal meat was taken on the southern journey "in case we find ourselves attacked by scurvy", On his 1907–09 Nimrod expedition Shackleton avoided the disease through careful dietary provision, including extra penguin and seal meat. However, Lieutenant Edward Evans

Edward Evans, 1st Baron Mountevans

Admiral Edward Ratcliffe Garth Russell Evans, 1st Baron Mountevans, KCB, DSO , known as "Teddy" Evans, was a British naval officer and Antarctic explorer...

almost died of it during the 1910–13 Terra Nova expedition, and scurvy was particularly devastating to the Ross Sea party

Ross Sea Party

The Ross Sea party was a component of Sir Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition 1914–17. Its task was to lay a series of supply depots across the Great Ice Barrier from the Ross Sea to the Beardmore Glacier, along the polar route established by earlier Antarctic expeditions...

during 1915–16. It remained a danger until its causes were finally established, some 25 years after the Discovery expedition.

Aftermath

Scott was given leave from the Navy to write the official expedition account, The Voyage of the Discovery; this was published in 1905, and sold well. However, Scott's account in the book of Shackleton's breakdown during the southern journey led to disagreement between the two men, particularly over Scott's version of the extent to which his companion had been carried on the sledge. The implication was that Shackleton's breakdown had caused the relatively unimpressive southern record.Scott eventually resumed his naval career, first as an assistant to the Director of Naval Intelligence and then, in August 1906, as Flag-captain to Rear-Admiral George Egerton on HMS Victorious

HMS Victorious (1895)

HMS Victorious was one of nine Majestic-class predreadnought battleships of the British Royal Navy.-Technical characteristics:HMS Victorious was laid down at Chatham Dockyard on 28 May 1894 and launched on 19 October 1895...

. He had by this time become a national hero, despite his aversion to the limelight, and the expedition was being presented to the public as a triumph. This euphoria was not conducive to objective analysis, or to thoughtful appraisal of the expedition's strengths and weaknesses. In particular, the glorification by Scott of man-hauling as something intrinsically more noble than other ice travel techniques led to a general distrust of methods involving ski and dogs, a mindset that was carried forward into later expeditions. This mystified seasoned ice travellers such as Fridtjof Nansen

Fridtjof Nansen

Fridtjof Wedel-Jarlsberg Nansen was a Norwegian explorer, scientist, diplomat, humanitarian and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. In his youth a champion skier and ice skater, he led the team that made the first crossing of the Greenland interior in 1888, and won international fame after reaching a...

, whose advice on such matters was usually sought, but often set aside.

The Discovery Expedition launched the Antarctic careers of several who became stalwarts or leaders of expeditions in the following fifteen years. Apart from Scott and Shackleton, Frank Wild and Ernest Joyce from the lower deck returned repeatedly to the ice, apparently unable to settle back into normal life. William Lashly and Edgar Evans, Scott's companions on the 1903 western journey, aligned themselves with their leader's future plans and became his regular sledging partners. Tom Crean followed both Scott and Shackleton on later expeditions. Lieutenant "Teddy" Evans

Edward Evans, 1st Baron Mountevans

Admiral Edward Ratcliffe Garth Russell Evans, 1st Baron Mountevans, KCB, DSO , known as "Teddy" Evans, was a British naval officer and Antarctic explorer...

, first officer on the relief ship Morning, began plans to lead an expedition of his own, before teaming up with Scott in 1910.

Soon after resuming his naval duties, Scott revealed to the Royal Geographical Society his intention to return to Antarctica, but the information was not at that stage made public. Scott was forestalled by Shackleton, who early in 1907 announced his plans to lead an expedition with the twin objectives of reaching the geographic and magnetic South Poles. Under duress, Shackleton agreed not to work from McMurdo Sound, which Scott was claiming as his own sphere of work. In the event, unable to find a safe landing elsewhere, Shackleton was forced to break this promise. His expedition was highly successful, its southern march ending at 88°23′, less than 100 geographical miles from the South Pole, while its northern party reached the location of the South Magnetic Pole. However, Shackleton's breach of his undertaking caused a significant break in relations between the two men, with Scott dismissing his former companion as a liar and a rogue.

Scott's plans gradually came to fruition – a large-scale scientific and geographical expedition with the conquest of the South Pole as its principal objective. Scott was anxious to avoid the amateurism that had been associated with the Discovery Expedition's scientific work. He appointed Edward Wilson as his chief scientist, and Wilson selected an experienced team. The expedition set off in June 1910 in Terra Nova, one of Discovery's relief ships. Its programme was complicated by the simultaneous arrival in the Antarctic of Roald Amundsen

Roald Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen was a Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He led the first Antarctic expedition to reach the South Pole between 1910 and 1912 and he was the first person to reach both the North and South Poles. He is also known as the first to traverse the Northwest Passage....

's Norwegian expedition. Amundsen's party reached the South Pole on 14 December 1911 and returned safely. Scott and four companions, including Wilson, arrived at the Pole on 17 January 1912; all five perished on the return journey.

Sources

}}}}

}}

}}

}}

}}

}}

}}

}}

}}

}}

}}

}}

}}

Online sources

}}

Further reading

- Landis, M: Antarctica: Exploring the Extreme: 400 Years of Adventure. Chicago Review Press 2003 ISBN 1-55652-480-3

- Seaver, George: Edward Wilson of the Antarctic John Murray 1933

- Skelton, J V & Wilson, D W: Discovery Illustrated: Pictures from Captain Scott's First Antarctic Expedition Reardon Publishing 2001 ISBN 1-873877-48-X

- Skelton, Judy (ed) The Antarctic Journals of Reginald Skelton: 'Another Little Job for the Tinker. Reardon Publishing 2004 ISBN 1-873877-68-4

External links

- Expedition information at CoolAntarctica.com Additional images and brief account of expedition

- Scott Polar Research Institute Provides extensive Antarctic information, with comprehensive list of expeditions.

- A biography of Scott