Economy of England in the Middle Ages

Encyclopedia

Norman conquest of England

The Norman conquest of England began on 28 September 1066 with the invasion of England by William, Duke of Normandy. William became known as William the Conqueror after his victory at the Battle of Hastings on 14 October 1066, defeating King Harold II of England...

in 1066, to the death of Henry VII

Henry VII of England

Henry VII was King of England and Lord of Ireland from his seizing the crown on 22 August 1485 until his death on 21 April 1509, as the first monarch of the House of Tudor....

in 1509, was fundamentally agricultural, though even before the invasion the market economy was important to producers. Norman institutions, including serfdom, were superimposed on an existing system of open fields

Open field system

The open field system was the prevalent agricultural system in much of Europe from the Middle Ages to as recently as the 20th century in some places, particularly Russia and Iran. Under this system, each manor or village had several very large fields, farmed in strips by individual families...

and mature, well-established towns involved in international trade. Over the next five centuries the economy would at first grow and then suffer an acute crisis, resulting in significant political and economic change. Despite economic dislocation in urban and extraction economies, including shifts in the holders of wealth and the location of these economies, the economic output of towns and mines developed and intensified over the period. By the end of the period, England had a weak government, by later standards, overseeing an economy dominated by rented farms controlled by gentry, and a thriving community of indigenous English merchants and corporations.

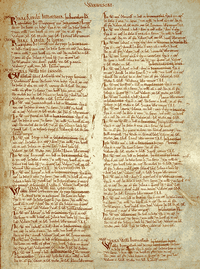

The 12th and 13th centuries saw a huge development of the English economy. This was partially driven by the growth in the population from around 1.5 million at the time of the creation of the Domesday Book

Domesday Book

Domesday Book , now held at The National Archives, Kew, Richmond upon Thames in South West London, is the record of the great survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086...

in 1086 to between 4 and 5 million in 1300. England remained a primarily agricultural economy, with the rights of major landowners and the duties of serfs increasingly enshrined in English law. More land, much of it at the expense of the royal forests, was brought into production to feed the growing population or to produce wool for export to Europe. Many hundreds of new towns, some of them planned

Planned community

A planned community, or planned city, is any community that was carefully planned from its inception and is typically constructed in a previously undeveloped area. This contrasts with settlements that evolve in a more ad hoc fashion. Land use conflicts are less frequent in planned communities since...

, sprung up across England, supporting the creation of guild

Guild

A guild is an association of craftsmen in a particular trade. The earliest types of guild were formed as confraternities of workers. They were organized in a manner something between a trade union, a cartel, and a secret society...

s, charter fair

Charter fair

A charter fair in England is a street fair or market which was established by Royal Charter. Many charter fairs date back to the Middle Ages, with their heyday occurring during the 13th century...

s and other important medieval institutions. The descendants of the Jewish financiers who had first come to England with William the Conqueror played a significant role in the growing economy, along with the new Cistercian and Augustinian

Augustinians

The term Augustinians, named after Saint Augustine of Hippo , applies to two separate and unrelated types of Catholic religious orders:...

religious orders that came to become major players in the wool trade of the north. Mining increased in England, with the silver boom of the 12th century helping to fuel a fast-expanding currency.

Economic growth began to falter by the end of the 13th century, owing to a combination of over-population, land shortages and depleted soils. The loss of life in the Great Famine

Great Famine of 1315–1317

The Great Famine of 1315–1317 was the first of a series of large scale crises that struck Northern Europe early in the fourteenth century...

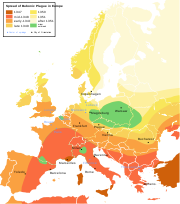

of 1315–17 shook the English economy severely and population growth ceased; the first outbreak of the Black Death

Black Death

The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, peaking in Europe between 1348 and 1350. Of several competing theories, the dominant explanation for the Black Death is the plague theory, which attributes the outbreak to the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Thought to have...

in 1348 then killed around half the English population, with major implications for the post-plague economy. The agricultural sector shrank, with higher wages, lower prices and shrinking profits leading to the final demise of the old demesne

Demesne

In the feudal system the demesne was all the land, not necessarily all contiguous to the manor house, which was retained by a lord of the manor for his own use and support, under his own management, as distinguished from land sub-enfeoffed by him to others as sub-tenants...

system and the advent of the modern farming system of cash rents for lands. The Peasants Revolt of 1381 shook the older feudal order and limited the levels of royal taxation considerably for a century to come. The 15th century saw the growth of the English cloth industry and the establishment of a new class of international English merchant, increasingly based in London and the South-West, prospering at the expense of the older, shrinking economy of the eastern towns. These new trading systems brought about the end of many of the international fairs and the rise of the chartered company

Livery Company

The Livery Companies are 108 trade associations in the City of London, almost all of which are known as the "Worshipful Company of" the relevant trade, craft or profession. The medieval Companies originally developed as guilds and were responsible for the regulation of their trades, controlling,...

. Together with improvements in metalworking

Metalworking

Metalworking is the process of working with metals to create individual parts, assemblies, or large scale structures. The term covers a wide range of work from large ships and bridges to precise engine parts and delicate jewelry. It therefore includes a correspondingly wide range of skills,...

and shipbuilding

Shipbuilding

Shipbuilding is the construction of ships and floating vessels. It normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation that traces its roots to before recorded history.Shipbuilding and ship repairs, both...

, this represents the end of the medieval economy, and the beginnings of the early modern period in English economics.

Invasion and the early Norman period (1066–1100)

William the Conqueror invaded England in 1066, defeating the Anglo-Saxon King Harold GodwinsonHarold Godwinson

Harold Godwinson was the last Anglo-Saxon King of England.It could be argued that Edgar the Atheling, who was proclaimed as king by the witan but never crowned, was really the last Anglo-Saxon king...

at the Battle of Hastings

Battle of Hastings

The Battle of Hastings occurred on 14 October 1066 during the Norman conquest of England, between the Norman-French army of Duke William II of Normandy and the English army under King Harold II...

and placing the country under Norman rule

Norman conquest of England

The Norman conquest of England began on 28 September 1066 with the invasion of England by William, Duke of Normandy. William became known as William the Conqueror after his victory at the Battle of Hastings on 14 October 1066, defeating King Harold II of England...

. This campaign was followed by fierce military operations known as the Harrying of the North

Harrying of the North

The Harrying of the North was a series of campaigns waged by William the Conqueror in the winter of 1069–1070 to subjugate Northern England, and is part of the Norman conquest of England...

in 1069–70, extending Norman authority across the north of England. William's system of government was broadly feudal

Feudalism

Feudalism was a set of legal and military customs in medieval Europe that flourished between the 9th and 15th centuries, which, broadly defined, was a system for ordering society around relationships derived from the holding of land in exchange for service or labour.Although derived from the...

in that the right to possess land was linked to service to the king, but in many other ways the invasion did little to alter the nature of the English economy. Most of the damage done in the invasion was in the north and the west of England, some of it still recorded as "wasteland" in 1086. Many of the key features of the English agricultural and financial system remained in place in the decades immediately after the conquest.

English agriculture

Agriculture formed the bulk of the English economy at the time of the Norman invasion. Twenty years after the invasion, 35% of England was covered in arableArable land

In geography and agriculture, arable land is land that can be used for growing crops. It includes all land under temporary crops , temporary meadows for mowing or pasture, land under market and kitchen gardens and land temporarily fallow...

land, 25% was put to pasture

Pasture

Pasture is land used for grazing. Pasture lands in the narrow sense are enclosed tracts of farmland, grazed by domesticated livestock, such as horses, cattle, sheep or swine. The vegetation of tended pasture, forage, consists mainly of grasses, with an interspersion of legumes and other forbs...

, 15% was covered by woodlands and the remaining 25% was predominantly moorland, fens and heaths. Wheat formed the single most important arable crop, but rye

Rye

Rye is a grass grown extensively as a grain and as a forage crop. It is a member of the wheat tribe and is closely related to barley and wheat. Rye grain is used for flour, rye bread, rye beer, some whiskeys, some vodkas, and animal fodder...

, barley

Barley

Barley is a major cereal grain, a member of the grass family. It serves as a major animal fodder, as a base malt for beer and certain distilled beverages, and as a component of various health foods...

and oats

OATS

OATS - Open Source Assistive Technology Software - is a source code repository or "forge" for assistive technology software. It was launched in 2006 with the goal to provide a one-stop “shop” for end users, clinicians and open-source developers to promote and develop open source assistive...

were also cultivated extensively. In the more fertile parts of the country, such as the Thames valley

Thames Valley

The Thames Valley Region is a loose term for the English counties and towns roughly following the course of the River Thames as it flows from Oxfordshire in the west to London in the east. It includes parts of Buckinghamshire, Berkshire, North Hampshire, Surrey and west London...

, the Midlands

English Midlands

The Midlands, or the English Midlands, is the traditional name for the area comprising central England that broadly corresponds to the early medieval Kingdom of Mercia. It borders Southern England, Northern England, East Anglia and Wales. Its largest city is Birmingham, and it was an important...

and the east of England, legumes and beans were also cultivated. Sheep, cattle

Cattle

Cattle are the most common type of large domesticated ungulates. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae, are the most widespread species of the genus Bos, and are most commonly classified collectively as Bos primigenius...

, ox

Ox

An ox , also known as a bullock in Australia, New Zealand and India, is a bovine trained as a draft animal. Oxen are commonly castrated adult male cattle; castration makes the animals more tractable...

en and pigs were kept on English holdings, although most of these breeds were much smaller than modern equivalents and most would have been slaughtered in winter.

Manorial system

In the century prior to the Norman invasion, England's great estates, owned by the king, bishops, monasteries and thegnThegn

The term thegn , from OE þegn, ðegn "servant, attendant, retainer", is commonly used to describe either an aristocratic retainer of a king or nobleman in Anglo-Saxon England, or as a class term, the majority of the aristocracy below the ranks of ealdormen and high-reeves...

s, had been slowly broken up as a consequence of inheritance, wills, marriage settlements or church purchases. Most of the smaller landowning nobility lived on their properties and managed their own estates. The pre-Norman landscape had seen a trend away from isolated hamlets and towards larger villages engaged in arable cultivation in a band running north–south across England. These new villages had adopted an open field system

Open field system

The open field system was the prevalent agricultural system in much of Europe from the Middle Ages to as recently as the 20th century in some places, particularly Russia and Iran. Under this system, each manor or village had several very large fields, farmed in strips by individual families...

in which fields were divided into small strips of land, individually owned, with crops rotated between the field each year and the local woodlands and other common land

Common land

Common land is land owned collectively or by one person, but over which other people have certain traditional rights, such as to allow their livestock to graze upon it, to collect firewood, or to cut turf for fuel...

s carefully managed. Agricultural land on a manor was divided between some fields that the landowner would manage and cultivate directly, called demesne

Demesne

In the feudal system the demesne was all the land, not necessarily all contiguous to the manor house, which was retained by a lord of the manor for his own use and support, under his own management, as distinguished from land sub-enfeoffed by him to others as sub-tenants...

land, and the majority of the fields that would be cultivated by local peasants, who would pay rent to the landowner either through agricultural labour on the lord's demesne fields or through cash or produce. Around 6,000 watermill

Watermill

A watermill is a structure that uses a water wheel or turbine to drive a mechanical process such as flour, lumber or textile production, or metal shaping .- History :...

s of varying power and efficiency had been built in order to grind flour, freeing up peasant labour for other more productive agricultural tasks. The early English economy was not a subsistence economy and many crops were grown by peasant farmers for sale to the early English towns.

The Normans initially did not significantly alter the operation of the manor or the village economy. William reassigned large tracts of land amongst the Norman elite, creating vast estates in some areas, particularly along the Welsh border

Welsh Marches

The Welsh Marches is a term which, in modern usage, denotes an imprecisely defined area along and around the border between England and Wales in the United Kingdom. The precise meaning of the term has varied at different periods...

and in Sussex

Sussex

Sussex , from the Old English Sūþsēaxe , is an historic county in South East England corresponding roughly in area to the ancient Kingdom of Sussex. It is bounded on the north by Surrey, east by Kent, south by the English Channel, and west by Hampshire, and is divided for local government into West...

. The biggest change in the years after the invasion was the rapid reduction in the number of slaves being held in England. In the 10th century slaves had been very numerous, although their number had begun to diminish as a result of economic and religious pressure. Nonetheless, the new Norman aristocracy proved harsh landlords. The wealthier, formerly more independent Anglo-Saxon peasants found themselves rapidly sinking down the economic hierarchy, swelling the numbers of unfree workers, or serfs, forbidden to leave their manor and seek alternative employment. Those Anglo-Saxon nobles who had survived the invasion itself were rapidly assimilated into the Norman elite or economically crushed.

Creation of the forests

Royal forest

A royal forest is an area of land with different meanings in England, Wales and Scotland; the term forest does not mean forest as it is understood today, as an area of densely wooded land...

s. In Anglo-Saxon times there had been special woods for hunting called "hays", but the Norman forests were much larger and backed by legal mandate. The new forests were not necessarily heavily wooded but were defined instead by their protection and exploitation by the crown. The Norman forests were subject to special royal jurisdiction; forest law was "harsh and arbitrary, a matter purely for the King's will". Forests were expected to supply the king with hunting grounds, raw materials, goods and money. Revenue from forest rents and fines came to become extremely significant and forest wood was used for castles and royal ship building. Several forests played a key role in mining, such as the iron mining and working in the Forest of Dean

Forest of Dean

The Forest of Dean is a geographical, historical and cultural region in the western part of the county of Gloucestershire, England. The forest is a roughly triangular plateau bounded by the River Wye to the west and north, the River Severn to the south, and the City of Gloucester to the east.The...

and lead mining in the Forest of High Peak

Forest of High Peak

The Forest of High Peak was, in medieval times, a moorland forest covering most of the North West of Derbyshire, in England as far south as Tideswell and Buxton....

. Several other groups bound up economically with forests; many monasteries had special rights in particular forests, for example for hunting or tree felling. The royal forests were accompanied by the rapid creation of locally owned parks

Medieval deer park

A medieval deer park was an enclosed area containing deer. It was bounded by a ditch and bank with a wooden park pale on top of the bank. The ditch was typically on the inside, thus allowing deer to enter the park but preventing them from leaving.-History:...

and chases

Chase (land)

In the United Kingdom a chase is a type of common land used for hunting to which there are no specifically designated officers and laws, but there are reserved hunting rights for one or more persons. Similarly, a Royal Chase is a type of Crown Estate by the same description, but where certain...

.

Trade, manufacturing and the towns

Although primarily rural, England had a number of old, economically important towns in 1066. A large amount of trade came through the Eastern towns, including London, York

York

York is a walled city, situated at the confluence of the Rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. The city has a rich heritage and has provided the backdrop to major political events throughout much of its two millennia of existence...

, Winchester

Winchester

Winchester is a historic cathedral city and former capital city of England. It is the county town of Hampshire, in South East England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government district, and is located at the western end of the South Downs, along the course of...

, Lincoln

Lincoln, Lincolnshire

Lincoln is a cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England.The non-metropolitan district of Lincoln has a population of 85,595; the 2001 census gave the entire area of Lincoln a population of 120,779....

, Norwich

Norwich

Norwich is a city in England. It is the regional administrative centre and county town of Norfolk. During the 11th century, Norwich was the largest city in England after London, and one of the most important places in the kingdom...

, Ipswich

Ipswich

Ipswich is a large town and a non-metropolitan district. It is the county town of Suffolk, England. Ipswich is located on the estuary of the River Orwell...

and Thetford

Thetford

Thetford is a market town and civil parish in the Breckland district of Norfolk, England. It is on the A11 road between Norwich and London, just south of Thetford Forest. The civil parish, covering an area of , has a population of 21,588.-History:...

. Much of this trade was with France, the Low Countries

Low Countries

The Low Countries are the historical lands around the low-lying delta of the Rhine, Scheldt, and Meuse rivers, including the modern countries of Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and parts of northern France and western Germany....

and Germany, but the North-East of England traded with partners as far away as Sweden. Cloth was already being imported to England before the invasion through the mercery

Mercery

Mercery initially referred to silk, linen, and fustian textiles imported to England in the 12th century.The term later extended to goods made of these and the sellers of those goods.-Mercer:...

trade.

Some towns, such as York, suffered from Norman sacking during William's northern campaigns. Other towns saw the widespread demolition of houses to make room for new motte and bailey fortifications, as was the case in Lincoln. The Norman invasion also brought significant economic changes with the arrival of the first Jews to English cities. William I brought over wealthy Jews from the Rouen

Rouen

Rouen , in northern France on the River Seine, is the capital of the Haute-Normandie region and the historic capital city of Normandy. Once one of the largest and most prosperous cities of medieval Europe , it was the seat of the Exchequer of Normandy in the Middle Ages...

community in Normandy to settle in London, apparently to carry out financial services for the crown. In the years immediately after the invasion, a lot of wealth was drawn out of England in various ways by the Norman rulers and reinvested in Normandy, making William immensely wealthy as an individual ruler.

The minting

Mint (coin)

A mint is an industrial facility which manufactures coins for currency.The history of mints correlates closely with the history of coins. One difference is that the history of the mint is usually closely tied to the political situation of an era...

of coins was decentralised in the Saxon period; every borough was mandated to have a mint and therefore a centre for trading in bullion. Nonetheless, there was strict royal control over these moneyer

Moneyer

A moneyer is someone who physically creates money. Moneyers have a long tradition, dating back at least to ancient Greece. They became most prominent in the Roman Republic, continuing into the empire.-Roman Republican moneyers:...

s, and coin dies

Die (manufacturing)

A die is a specialized tool used in manufacturing industries to cut or shape material using a press. Like molds, dies are generally customized to the item they are used to create...

could only be made in London. William retained this process and generated a high standard of Norman coins, leading to the use of the term "sterling" as the name for the Norman silver coins.

Governance and taxation

William I inherited the Anglo-Saxon system in which the king drew his revenues from: a mixture of customs; profits from re-minting coinage; fines; profits from his own demesne lands; and the system of English land-based taxation called the geldDanegeld

The Danegeld was a tax raised to pay tribute to the Viking raiders to save a land from being ravaged. It was called the geld or gafol in eleventh-century sources; the term Danegeld did not appear until the early twelfth century...

. William reaffirmed this system, enforcing collection of the geld through his new system of sheriffs and increasing the taxes on trade. William was also famous for commissioning the Domesday Book

Domesday Book

Domesday Book , now held at The National Archives, Kew, Richmond upon Thames in South West London, is the record of the great survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086...

in 1086, a vast document which attempted to record the economic condition of his new kingdom.

Mid-medieval growth (1100–1290)

The 12th and 13th centuries were a period of huge economic growth in England. The population of England rose from around 1.5 million in 1086 to around 4 or 5 million in 1300, stimulating increased agricultural outputs and the export of raw materials to Europe. In contrast to the previous two centuries, England was relatively secure from invasion. Except for the years of the AnarchyThe Anarchy

The Anarchy or The Nineteen-Year Winter was a period of English history during the reign of King Stephen, which was characterised by civil war and unsettled government...

, most military conflicts either had only localised economic impact or proved only temporarily disruptive. English economic thinking remained conservative, seeing the economy as consisting of three groups: the ordines, those who fought, or the nobility; laboratores, those who worked, in particular the peasantry; and oratores, those who prayed, or the clerics. Trade and merchants played little part in this model and were frequently vilified at the start of the period, although they were increasingly tolerated towards the end of the 13th century.

English agriculture and the landscape

Weald

The Weald is the name given to an area in South East England situated between the parallel chalk escarpments of the North and the South Downs. It should be regarded as three separate parts: the sandstone "High Weald" in the centre; the clay "Low Weald" periphery; and the Greensand Ridge which...

, for example, agriculture centred on grazing animals on the woodland pastures, whilst in the Fens

The Fens

The Fens, also known as the , are a naturally marshy region in eastern England. Most of the fens were drained several centuries ago, resulting in a flat, damp, low-lying agricultural region....

fishing and bird-hunting was supplemented by basket-making

Basket weaving

Basket weaving is the process of weaving unspun vegetable fibres into a basket or other similar form. People and artists who weave baskets are called basketmakers and basket weavers.Basketry is made from a variety of fibrous or pliable materials•anything that will bend and form a shape...

and peat

Peat

Peat is an accumulation of partially decayed vegetation matter or histosol. Peat forms in wetland bogs, moors, muskegs, pocosins, mires, and peat swamp forests. Peat is harvested as an important source of fuel in certain parts of the world...

-cutting. In some locations, such as Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire is a county in the east of England. It borders Norfolk to the south east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south west, Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire to the west, South Yorkshire to the north west, and the East Riding of Yorkshire to the north. It also borders...

and Droitwich, salt manufacture was important, including production for the export market. Fishing became an important trade along the English coast, especially in Great Yarmouth

Great Yarmouth

Great Yarmouth, often known to locals as Yarmouth, is a coastal town in Norfolk, England. It is at the mouth of the River Yare, east of Norwich.It has been a seaside resort since 1760, and is the gateway from the Norfolk Broads to the sea...

and Scarborough, and the herring

Herring

Herring is an oily fish of the genus Clupea, found in the shallow, temperate waters of the North Pacific and the North Atlantic oceans, including the Baltic Sea. Three species of Clupea are recognized. The main taxa, the Atlantic herring and the Pacific herring may each be divided into subspecies...

was a particularly popular catch; salted at the coast, it could then be shipped inland or exported to Europe. Piracy between competing English fishing fleets was not unknown during the period. Sheep were the most common farm animal in England during the period, their numbers doubling by the 14th century. Sheep became increasingly widely used for wool, particularly in the Welsh borders

Welsh Marches

The Welsh Marches is a term which, in modern usage, denotes an imprecisely defined area along and around the border between England and Wales in the United Kingdom. The precise meaning of the term has varied at different periods...

, Lincolnshire and the Pennines

Pennines

The Pennines are a low-rising mountain range, separating the North West of England from Yorkshire and the North East.Often described as the "backbone of England", they form a more-or-less continuous range stretching from the Peak District in Derbyshire, around the northern and eastern edges of...

. Pigs remained popular on holdings because of their ability to scavenge for food. Oxen remained the primary plough animal, with horses used more widely on farms in the south of England towards the end of the 12th century. Rabbits were introduced from France in the 13th century and farmed for their meat in special warrens.

The underlying productivity of English agriculture remained low, despite the increases in food production. Wheat prices fluctuated heavily year to year, depending on local harvests; up to a third of the grain produced in England was potentially for sale, and much of it ended up in the growing towns. Despite their involvement in the market, even the wealthiest peasants prioritised spending on housing and clothing, with little left for other personal consumption. Records of household belongings show most possessing only "old, worn-out and mended utensils" and tools.

The royal forests grew in size for much of the 12th century, before contracting in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. Henry I

Henry I of England

Henry I was the fourth son of William I of England. He succeeded his elder brother William II as King of England in 1100 and defeated his eldest brother, Robert Curthose, to become Duke of Normandy in 1106...

extended the size and scope of royal forests, especially in Yorkshire

Yorkshire

Yorkshire is a historic county of northern England and the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its great size in comparison to other English counties, functions have been increasingly undertaken over time by its subdivisions, which have also been subject to periodic reform...

; after the Anarchy of 1135–53, Henry II

Henry II of England

Henry II ruled as King of England , Count of Anjou, Count of Maine, Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Duke of Gascony, Count of Nantes, Lord of Ireland and, at various times, controlled parts of Wales, Scotland and western France. Henry, the great-grandson of William the Conqueror, was the...

continued to expand the forests until they comprised around 20% of England. In 1217 the Charter of the Forest

Charter of the forest

The Charter of the Forest is a charter originally sealed in England by King Henry III. It was first issued in 1217 as a complementary charter to the Magna Carta from which it had evolved. It was reissued in 1225 with a number of minor changes to wording, and then was joined with Magna Carta in the...

was enacted, in part to mitigate the worst excesses of royal jurisdiction, and established a more structured range of fines and punishments for peasants who illegally hunted or felled trees in the forests. By the end of the century the king had come under increasing pressure to reduce the size of the royal forests, leading to the "Great Perambulation" around 1300; this significantly reduced the extent to the forests, and by 1334 they were only around two-thirds the size they had been in 1250. Royal revenue streams from the shrinking forests diminished considerably in the early 14th century.

Development of estate management

Demesne

In the feudal system the demesne was all the land, not necessarily all contiguous to the manor house, which was retained by a lord of the manor for his own use and support, under his own management, as distinguished from land sub-enfeoffed by him to others as sub-tenants...

and peasant lands paid for in agricultural labour. Landowners could profit from the sales of goods from their demesne lands and a local lord could also expect to receive income from fines and local customs, whilst more powerful nobles profited from their own regional courts and rights.

During the 12th century major landowners tended to rent out their demesne lands for money, motivated by static prices for produce and the chaos of the Anarchy between 1135 and 1153. This practice began to alter in the 1180s and '90s, spurred by the greater political stability. In the first years of John's reign, agricultural prices almost doubled, at once increasing the potential profits on the demesne estates and also increasing the cost of living for the landowners themselves. Landowners now attempted wherever possible to bring their demesne lands back into direct management, creating a system of administrators and officials to run their new system of estates.

New land was brought into cultivation to meet demand for food, including drained marshes and fens, such as Romney Marsh

Romney Marsh

Romney Marsh is a sparsely populated wetland area in the counties of Kent and East Sussex in the south-east of England. It covers about 100 mi ² .-Quotations:*“As Egypt was the gift of the Nile, this level tract .....

, the Somerset Levels

Somerset Levels

The Somerset Levels, or the Somerset Levels and Moors as they are less commonly but more correctly known, is a sparsely populated coastal plain and wetland area of central Somerset, South West England, between the Quantock and Mendip Hills...

and the Fens; royal forests from the late 12th century onwards; and poorer lands in the north, south-west and in the Welsh Marches

Welsh Marches

The Welsh Marches is a term which, in modern usage, denotes an imprecisely defined area along and around the border between England and Wales in the United Kingdom. The precise meaning of the term has varied at different periods...

. The first windmill

Windmill

A windmill is a machine which converts the energy of wind into rotational energy by means of vanes called sails or blades. Originally windmills were developed for milling grain for food production. In the course of history the windmill was adapted to many other industrial uses. An important...

s in England began to appear along the south and east coasts in the 12th century, expanding in number in the 13th, adding to the mechanised power available to the manors. By 1300 it has been estimated that there were more than 10,000 watermills in England, used both for grinding corn and for fulling

Fulling

Fulling or tucking or walking is a step in woolen clothmaking which involves the cleansing of cloth to eliminate oils, dirt, and other impurities, and making it thicker. The worker who does the job is a fuller, tucker, or walker...

cloth. Fish ponds were created on most estates to provide freshwater fish for the consumption of the nobility and church; these ponds were extremely expensive to create and maintain. Improved ways of running estates began to be circulated and were popularised in Walter de Henley's famous book Le Dite de Hosebondrie, written around 1280. In some regions and under some landowners, investment and innovation increased yields significantly through improved ploughing and fertilisers – particularly in Norfolk, where yields eventually equalled later 18th-century levels.

Role of the Church in agriculture

The Church in England was a major landowner throughout the medieval period and played an important part in the development of agriculture and rural trade in the first two centuries of Norman rule. The Cistercian order first arrived in England in 1128, establishing around 80 new monastic housesMonastery

Monastery denotes the building, or complex of buildings, that houses a room reserved for prayer as well as the domestic quarters and workplace of monastics, whether monks or nuns, and whether living in community or alone .Monasteries may vary greatly in size – a small dwelling accommodating only...

over the next few years; the wealthy Augustinians

Augustinians

The term Augustinians, named after Saint Augustine of Hippo , applies to two separate and unrelated types of Catholic religious orders:...

also established themselves and expanded to occupy around 150 houses, all supported by agricultural estates, many of them in the north of England. By the 13th century these and other orders were acquiring new lands and had become major economic players both as landowners and as middlemen in the expanding wool trade. In particular, the Cistercians led the development of the grange system. Granges were separate manors in which the fields were all cultivated by the monastic officials, rather than being divided up between demesne and rented fields, and became known for trialling new agricultural techniques during the period. Elsewhere, many monasteries had significant economic impact on the landscape, such as the monks of Glastonbury

Glastonbury Abbey

Glastonbury Abbey was a monastery in Glastonbury, Somerset, England. The ruins are now a grade I listed building, and a Scheduled Ancient Monument and are open as a visitor attraction....

, responsible for the draining of the Somerset Levels

Somerset Levels

The Somerset Levels, or the Somerset Levels and Moors as they are less commonly but more correctly known, is a sparsely populated coastal plain and wetland area of central Somerset, South West England, between the Quantock and Mendip Hills...

to create new pasture land.

The military crusading order of the Knights Templar

Knights Templar

The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon , commonly known as the Knights Templar, the Order of the Temple or simply as Templars, were among the most famous of the Western Christian military orders...

also held extensive property in England, bringing in around £2,200 per annum by the time of their fall. It comprised primarily rural holdings rented out for cash, but also included some urban properties in London. Following the dissolution of the Templar order in France by Philip IV of France

Philip IV of France

Philip the Fair was, as Philip IV, King of France from 1285 until his death. He was the husband of Joan I of Navarre, by virtue of which he was, as Philip I, King of Navarre and Count of Champagne from 1284 to 1305.-Youth:A member of the House of Capet, Philip was born at the Palace of...

, Edward II

Edward II of England

Edward II , called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England from 1307 until he was deposed by his wife Isabella in January 1327. He was the sixth Plantagenet king, in a line that began with the reign of Henry II...

ordered their properties to be seized and passed to the Hospitaller

Knights Hospitaller

The Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem of Rhodes and of Malta , also known as the Sovereign Military Order of Malta , Order of Malta or Knights of Malta, is a Roman Catholic lay religious order, traditionally of military, chivalrous, noble nature. It is the world's...

order in 1313, but in practice many properties were taken by local landowners and the Hospital was still attempting to reclaim them twenty-five years later.

The Church was responsible for the system of tithe

Tithe

A tithe is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash, cheques, or stocks, whereas historically tithes were required and paid in kind, such as agricultural products...

s, a levy of 10% on "all agrarian produce... other natural products gained via labour... wages received by servants and labourers, and to the profits of rural merchants". Tithes gathered in the form of produce could be either consumed by the recipient, or sold on and bartered for other resources. The tithe was relatively onerous for the typical peasant, although in many instances the actual levy fell below the desired 10%. Many clergy moved to the towns as part of the urban growth of the period, and by 1300 around one in twenty city dwellers was a clergyman. One effect of the tithe was to transfer a considerable amount of agriculture wealth into the cities, where it was then spent by these urban clergy. The need to sell tithe produce that could not be consumed by the local clergy also spurred the growth of trade.

Expansion of mining

Mining did not make up a large part of the English medieval economy, but the 12th and 13th centuries saw an increased demand for metals in the country, thanks to the considerable population growth and building construction, including the great cathedrals and churches. Four metals were mined commercially in England during the period, namely iron, tin

Tin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn and atomic number 50. It is a main group metal in group 14 of the periodic table. Tin shows chemical similarity to both neighboring group 14 elements, germanium and lead and has two possible oxidation states, +2 and the slightly more stable +4...

, lead and silver; coal was also mined from the 13th century onwards, using a variety of refining techniques.

Iron mining occurred in several locations, including the main English centre in the Forest of Dean

Forest of Dean

The Forest of Dean is a geographical, historical and cultural region in the western part of the county of Gloucestershire, England. The forest is a roughly triangular plateau bounded by the River Wye to the west and north, the River Severn to the south, and the City of Gloucester to the east.The...

, as well as in Durham

Durham

Durham is a city in north east England. It is within the County Durham local government district, and is the county town of the larger ceremonial county...

and the Weald

Weald

The Weald is the name given to an area in South East England situated between the parallel chalk escarpments of the North and the South Downs. It should be regarded as three separate parts: the sandstone "High Weald" in the centre; the clay "Low Weald" periphery; and the Greensand Ridge which...

. Some iron to meet English demand was also imported from the continent, especially by the late 13th century. By end of the 12th century, the older method of acquiring iron ore through strip mining

Surface mining

Surface mining , is a type of mining in which soil and rock overlying the mineral deposit are removed...

was being supplemented by more advanced techniques, including tunnels, trenches and bell-pits. Iron ore was usually locally processed at a bloomery

Bloomery

A bloomery is a type of furnace once widely used for smelting iron from its oxides. The bloomery was the earliest form of smelter capable of smelting iron. A bloomery's product is a porous mass of iron and slag called a bloom. This mix of slag and iron in the bloom is termed sponge iron, which...

, and by the 14th century the first water-powered iron forge in England was built at Chingley

River Bewl

The River Bewl is a tributary of the River Teise in Kent, England. Its headwaters are in the High Weald, in Sussex between Lamberhurst, Wadhurst and Flimwell. The valley is deeply incised into Tunbridge Wells red sandstone, with a base of alluvium on Wadhurst clay.Between 1973 and 1975, a was...

. As a result of the diminishing woodlands and consequent increases in the cost of both wood and charcoal

Charcoal

Charcoal is the dark grey residue consisting of carbon, and any remaining ash, obtained by removing water and other volatile constituents from animal and vegetation substances. Charcoal is usually produced by slow pyrolysis, the heating of wood or other substances in the absence of oxygen...

, demand for coal increased in the 12th century and it began to be commercially produced from bell-pits and strip mining.

A silver boom occurred in England after the discovery of silver near Carlisle in 1133. Huge quantities of silver were produced from a semicircle of mines reaching across Cumberland

Cumberland

Cumberland is a historic county of North West England, on the border with Scotland, from the 12th century until 1974. It formed an administrative county from 1889 to 1974 and now forms part of Cumbria....

, Durham and Northumberland

Northumberland

Northumberland is the northernmost ceremonial county and a unitary district in North East England. For Eurostat purposes Northumberland is a NUTS 3 region and is one of three boroughs or unitary districts that comprise the "Northumberland and Tyne and Wear" NUTS 2 region...

– up to three to four tonnes of silver were mined each year, more than ten times the previous annual production across the whole of Europe. The result was a local economic boom and a major uplift to 12th-century royal finances. Tin mining was centred in Cornwall

Cornwall

Cornwall is a unitary authority and ceremonial county of England, within the United Kingdom. It is bordered to the north and west by the Celtic Sea, to the south by the English Channel, and to the east by the county of Devon, over the River Tamar. Cornwall has a population of , and covers an area of...

and Devon

Devon

Devon is a large county in southwestern England. The county is sometimes referred to as Devonshire, although the term is rarely used inside the county itself as the county has never been officially "shired", it often indicates a traditional or historical context.The county shares borders with...

, exploiting alluvial deposits and governed by the special Stannary Courts and Parliaments

Stannary Courts and Parliaments

The Stannary Parliaments and Stannary Courts were legislative and legal institutions in Cornwall and in Devon , England. The Stannary Courts administered equity for the region's tin-miners and tin mining interests, and they were also courts of record for the towns dependent on the mines...

. Tin formed a valuable export good, initially to Germany and then later in the 14th century to the Low Countries

Low Countries

The Low Countries are the historical lands around the low-lying delta of the Rhine, Scheldt, and Meuse rivers, including the modern countries of Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and parts of northern France and western Germany....

. Lead was usually mined as a by-product of mining for silver, with mines in Yorkshire

Yorkshire

Yorkshire is a historic county of northern England and the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its great size in comparison to other English counties, functions have been increasingly undertaken over time by its subdivisions, which have also been subject to periodic reform...

, Durham and the north, as well as in Devon. Economically fragile, the lead mines usually survived as a result of being subsidised by silver production.

Growth of English towns

Planned community

A planned community, or planned city, is any community that was carefully planned from its inception and is typically constructed in a previously undeveloped area. This contrasts with settlements that evolve in a more ad hoc fashion. Land use conflicts are less frequent in planned communities since...

: Richard I

Richard I of England

Richard I was King of England from 6 July 1189 until his death. He also ruled as Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Duke of Gascony, Lord of Cyprus, Count of Anjou, Count of Maine, Count of Nantes, and Overlord of Brittany at various times during the same period...

created Portsmouth

Portsmouth

Portsmouth is the second largest city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire on the south coast of England. Portsmouth is notable for being the United Kingdom's only island city; it is located mainly on Portsea Island...

, John founded Liverpool

Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough of Merseyside, England, along the eastern side of the Mersey Estuary. It was founded as a borough in 1207 and was granted city status in 1880...

, and successive monarchs followed with Harwich

Harwich

Harwich is a town in Essex, England and one of the Haven ports, located on the coast with the North Sea to the east. It is in the Tendring district. Nearby places include Felixstowe to the northeast, Ipswich to the northwest, Colchester to the southwest and Clacton-on-Sea to the south...

, Stony Stratford

Stony Stratford

Stony Stratford is a constituent town of Milton Keynes and is a civil parish with a town council within the Borough of Milton Keynes. It is in the north west corner of Milton Keynes, bordering Northamptonshire and separated from it by the River Great Ouse...

, Dunstable

Dunstable

Dunstable is a market town and civil parish located in Bedfordshire, England. It lies on the eastward tail spurs of the Chiltern Hills, 30 miles north of London. These geographical features form several steep chalk escarpments most noticeable when approaching Dunstable from the north.-Etymology:In...

, Royston

Royston, Hertfordshire

Royston is a town and civil parish in the District of North Hertfordshire and county of Hertfordshire in England.It is situated on the Greenwich Meridian, which brushes the towns western boundary, and at the northernmost apex of the county on the same latitude of towns such as Milton Keynes and...

, Baldock

Baldock

Baldock is a historic market town in the local government district of North Hertfordshire in the ceremonial county of Hertfordshire, England where the River Ivel rises. It lies north of London, southeast of Bedford, and north northwest of the county town of Hertford...

, Wokingham

Wokingham

Wokingham is a market town and civil parish in Berkshire in South East England about west of central London. It is about east-southeast of Reading and west of Bracknell. It spans an area of and, according to the 2001 census, has a population of 30,403...

, Maidenhead

Maidenhead

Maidenhead is a town and unparished area within the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead, in Berkshire, England. It lies on the River Thames and is situated west of Charing Cross in London.-History:...

and Reigate

Reigate

Reigate is a historic market town in Surrey, England, at the foot of the North Downs, and in the London commuter belt. It is one of the main constituents of the Borough of Reigate and Banstead...

. The new towns were usually located with access to trade routes in mind, rather than defence, and the streets were laid out to make access to the town's market convenient. A growing percentage of England's population lived in urban areas; estimates suggest that this rose from around 5.5% in 1086 to up to 10% in 1377.

London held a special status within the English economy. The nobility purchased and consumed many luxury goods and services in the capital, and as early as the 1170s the London markets were providing exotic products such as spices, incense

Incense

Incense is composed of aromatic biotic materials, which release fragrant smoke when burned. The term "incense" refers to the substance itself, rather than to the odor that it produces. It is used in religious ceremonies, ritual purification, aromatherapy, meditation, for creating a mood, and for...

, palm oil

Palm oil

Palm oil, coconut oil and palm kernel oil are edible plant oils derived from the fruits of palm trees. Palm oil is extracted from the pulp of the fruit of the oil palm Elaeis guineensis; palm kernel oil is derived from the kernel of the oil palm and coconut oil is derived from the kernel of the...

, gems, silks, furs and foreign weapons. London was also an important hub for industrial activity; it had many blacksmiths making a wide range of goods, including decorative ironwork and early clocks. Pewter-working

Pewter

Pewter is a malleable metal alloy, traditionally 85–99% tin, with the remainder consisting of copper, antimony, bismuth and lead. Copper and antimony act as hardeners while lead is common in the lower grades of pewter, which have a bluish tint. It has a low melting point, around 170–230 °C ,...

, using English tin and lead, was also widespread in London during the period. The provincial towns also had a substantial number of trades by the end of the 13th century – a large town like Coventry

Coventry

Coventry is a city and metropolitan borough in the county of West Midlands in England. Coventry is the 9th largest city in England and the 11th largest in the United Kingdom. It is also the second largest city in the English Midlands, after Birmingham, with a population of 300,848, although...

, for example, contained over three hundred different specialist occupations, and a smaller town such as Durham

Durham

Durham is a city in north east England. It is within the County Durham local government district, and is the county town of the larger ceremonial county...

could support some sixty different professions. The increasing wealth of the nobility and the church was reflected in the widespread building of cathedral

Cathedral

A cathedral is a Christian church that contains the seat of a bishop...

s and other prestigious buildings in the larger towns, in turn making use of lead from English mines for roofing.

Land transport remained much more expensive than river or sea transport during the period. Many towns in this period, including York

York

York is a walled city, situated at the confluence of the Rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. The city has a rich heritage and has provided the backdrop to major political events throughout much of its two millennia of existence...

, Exeter

Exeter

Exeter is a historic city in Devon, England. It lies within the ceremonial county of Devon, of which it is the county town as well as the home of Devon County Council. Currently the administrative area has the status of a non-metropolitan district, and is therefore under the administration of the...

and Lincoln

Lincoln, Lincolnshire

Lincoln is a cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England.The non-metropolitan district of Lincoln has a population of 85,595; the 2001 census gave the entire area of Lincoln a population of 120,779....

, were linked to the oceans by navigable rivers and could act as seaports, with Bristol

Bristol

Bristol is a city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, with an estimated population of 433,100 for the unitary authority in 2009, and a surrounding Larger Urban Zone with an estimated 1,070,000 residents in 2007...

's port coming to dominate the lucrative trade in wine with Gascony

Gascony

Gascony is an area of southwest France that was part of the "Province of Guyenne and Gascony" prior to the French Revolution. The region is vaguely defined and the distinction between Guyenne and Gascony is unclear; sometimes they are considered to overlap, and sometimes Gascony is considered a...

by the 13th century, but shipbuilding generally remained on a modest scale and economically unimportant to England at this time. Transport remained very costly in comparison to the overall price of products. By the 13th century, groups of common carriers ran carting businesses, and carting brokers existed in London to link traders and carters. These used the four major land routes crossing England: Ermine Street

Ermine Street

Ermine Street is the name of a major Roman road in England that ran from London to Lincoln and York . The Old English name was 'Earninga Straete' , named after a tribe called the Earningas, who inhabited a district later known as Armingford Hundred, around Arrington, Cambridgeshire and Royston,...

, the Fosse Way

Fosse Way

The Fosse Way was a Roman road in England that linked Exeter in South West England to Lincoln in Lincolnshire, via Ilchester , Bath , Cirencester and Leicester .It joined Akeman Street and Ermin Way at Cirencester, crossed Watling Street at Venonis south...

, Icknield Street

Icknield Street

Icknield Street or Ryknild Street is a Roman road in Britain that runs from the Fosse Way at Bourton on the Water in Gloucestershire to Templeborough in South Yorkshire...

and Watling Street

Watling Street

Watling Street is the name given to an ancient trackway in England and Wales that was first used by the Britons mainly between the modern cities of Canterbury and St Albans. The Romans later paved the route, part of which is identified on the Antonine Itinerary as Iter III: "Item a Londinio ad...

. A large number of bridges were built during the 12th century to improve the trade network.

In the 13th century, England was still primarily supplying raw materials for export to Europe, rather than finished or processed goods. There were some exceptions, such as very high-quality cloths from Stamford

Stamford, Lincolnshire

Stamford is a town and civil parish within the South Kesteven district of the county of Lincolnshire, England. It is approximately to the north of London, on the east side of the A1 road to York and Edinburgh and on the River Welland...

and Lincoln, including the famous "Lincoln Scarlet" dyed cloth. Despite royal efforts to encourage it, however, barely any English cloth was being exported by 1347.

Expansion of the money supply

There was a gradual reduction in the number of locations allowed to mint coins in England; under Henry IIHenry II of England

Henry II ruled as King of England , Count of Anjou, Count of Maine, Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Duke of Gascony, Count of Nantes, Lord of Ireland and, at various times, controlled parts of Wales, Scotland and western France. Henry, the great-grandson of William the Conqueror, was the...

, only 30 boroughs were still able to use their own moneyers, and the tightening of controls continued throughout the 13th century. By the reign of Edward I

Edward I of England

Edward I , also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England from 1272 to 1307. The first son of Henry III, Edward was involved early in the political intrigues of his father's reign, which included an outright rebellion by the English barons...

there were only nine mints outside London and the king created a new official called the Master of the Mint

Master of the Mint

Master of the Mint was an important office in the governments of Scotland and England, and later Great Britain, between the 16th and 19th centuries. The Master was the highest officer in the Royal Mint. Until 1699, appointment was usually for life. Its holder occasionally sat in the cabinet...

to oversee these and the thirty furnaces operating in London to meet the demand for new coins. The amount of money in circulation hugely increased in this period; before the Norman invasion there had been around £50,000 in circulation as coin, but by 1311 this had risen to more than £1 million. At any particular point in time, though, much of this currency might be being stored prior to being used to support military campaigns or to be sent overseas to meet payments, resulting in bursts of temporary deflation as coins ceased to circulate within the English economy. One physical consequence of the growth in the coinage was that coins had to be manufactured in large numbers, being moved in barrels and sacks to be stored in local treasuries for royal use as the king travelled.

Rise of the guilds

The first English guildGuild

A guild is an association of craftsmen in a particular trade. The earliest types of guild were formed as confraternities of workers. They were organized in a manner something between a trade union, a cartel, and a secret society...

s emerged during the early 12th century. These guilds were fraternities of craftsmen that set out to manage their local affairs including "prices, workmanship, the welfare of its workers, and the suppression of interlopers and sharp practices". Amongst these early guilds were the "guilds merchants", who ran the local markets in towns and represented the merchant community in discussions with the crown. Other early guilds included the "craft guilds", representing specific trades. By 1130 there were major weavers

Weaving

Weaving is a method of fabric production in which two distinct sets of yarns or threads are interlaced at right angles to form a fabric or cloth. The other methods are knitting, lace making and felting. The longitudinal threads are called the warp and the lateral threads are the weft or filling...

' guilds in six English towns, as well as a fullers

Fulling

Fulling or tucking or walking is a step in woolen clothmaking which involves the cleansing of cloth to eliminate oils, dirt, and other impurities, and making it thicker. The worker who does the job is a fuller, tucker, or walker...

' guild in Winchester

Winchester

Winchester is a historic cathedral city and former capital city of England. It is the county town of Hampshire, in South East England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government district, and is located at the western end of the South Downs, along the course of...

. Over the following decades more guilds were created, often becoming increasingly involved in both local and national politics, although the guilds merchants were largely replaced by official groups established by new royal charters.

The craft guilds required relatively stable markets and a relative equality of income and opportunity amongst their members to function effectively. By the 14th century these conditions were increasingly uncommon. The first strains were seen in London, where the old guild system began to collapse – more trade was being conducted at a national level, making it hard for craftsmen to both manufacture goods and trade in them, and there were growing disparities in incomes between the richer and poorer craftsmen. As a result, under Edward III

Edward III of England

Edward III was King of England from 1327 until his death and is noted for his military success. Restoring royal authority after the disastrous reign of his father, Edward II, Edward III went on to transform the Kingdom of England into one of the most formidable military powers in Europe...

many guilds became companies or livery companies

Livery Company

The Livery Companies are 108 trade associations in the City of London, almost all of which are known as the "Worshipful Company of" the relevant trade, craft or profession. The medieval Companies originally developed as guilds and were responsible for the regulation of their trades, controlling,...

, chartered companies focusing on trade and finance, leaving the guild structures to represent the interests of the smaller, poorer manufacturers.

Merchants and the development of the charter fairs

The period also saw the development of charter fairCharter fair

A charter fair in England is a street fair or market which was established by Royal Charter. Many charter fairs date back to the Middle Ages, with their heyday occurring during the 13th century...

s in England, which reached their heyday in the 13th century. From the 12th century onwards, many English towns acquired a charter from the Crown allowing them to hold an annual fair, usually serving a regional or local customer base and lasting for two or three days. The practice increased in the next century and over 2,200 charters were issued to markets and fairs by English kings between 1200 to 1270. Fairs grew in popularity as the international wool trade increased: the fairs allowed English wool producers and ports on the east coast to engage with visiting foreign merchants, circumnavigating those English merchants in London keen to make a profit as middlemen. At the same time, wealthy magnate

Magnate

Magnate, from the Late Latin magnas, a great man, itself from Latin magnus 'great', designates a noble or other man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or other qualities...

consumers in England began to use the new fairs as a way to buy goods like spices, wax, preserved fish and foreign cloth in bulk from the international merchants at the fairs, again bypassing the usual London merchants.

Some fairs grew into major international events, falling into a set sequence during the economic year, with the Stamford

Stamford, Lincolnshire

Stamford is a town and civil parish within the South Kesteven district of the county of Lincolnshire, England. It is approximately to the north of London, on the east side of the A1 road to York and Edinburgh and on the River Welland...

fair in Lent, St Ives

St Ives, Cambridgeshire

St Ives is a market town in Cambridgeshire, England, around north-west of the city of Cambridge and north of London. It lies within the historic county boundaries of Huntingdonshire.-History:...

' in Easter, Boston

Boston, Lincolnshire

Boston is a town and small port in Lincolnshire, on the east coast of England. It is the largest town of the wider Borough of Boston local government district and had a total population of 55,750 at the 2001 census...

's in July, Winchester's in September and Northampton

Northampton

Northampton is a large market town and local government district in the East Midlands region of England. Situated about north-west of London and around south-east of Birmingham, Northampton lies on the River Nene and is the county town of Northamptonshire. The demonym of Northampton is...

's in November, with the many smaller fairs falling in-between. Although not as large as the famous Champagne fairs

Champagne fairs

The Champagne fairs were an annual cycle of trading fairs held in towns in the Champagne and Brie regions of France in the Middle Ages. From their origins in local agricultural and stock fairs, the Champagne fairs became an important engine in the reviving economic history of medieval Europe,...

in France, these English "great fairs" were still huge events; St Ives' Great Fair, for example, drew merchants from Flanders

Flanders

Flanders is the community of the Flemings but also one of the institutions in Belgium, and a geographical region located in parts of present-day Belgium, France and the Netherlands. "Flanders" can also refer to the northern part of Belgium that contains Brussels, Bruges, Ghent and Antwerp...

, Brabant

Duchy of Brabant

The Duchy of Brabant was a historical region in the Low Countries. Its territory consisted essentially of the three modern-day Belgian provinces of Flemish Brabant, Walloon Brabant and Antwerp, the Brussels-Capital Region and most of the present-day Dutch province of North Brabant.The Flag of...

, Norway, Germany and France for a four-week event each year, turning the normally small town into "a major commercial emporium".

The structure of the fairs reflected the importance of foreign merchants in the English economy and by 1273 only one-third of the English wool trade was actually controlled by English merchants. Between 1280 and 1320 the trade was primarily dominated by Italian merchants, but by the early 14th century German merchants had begun to present serious competition to the Italians. The Germans formed a self-governing alliance of merchants in London called the "Hanse of the Steelyard

Merchants of the Steelyard

The Merchants of the Steelyard was the English name for the merchants of the Hanseatic League who established their London Kontor in 1320. Located just west of London Bridge near Upper Thames Street. Cannon Street station occupies the site now...

" – the eventual Hanseatic League

Hanseatic League

The Hanseatic League was an economic alliance of trading cities and their merchant guilds that dominated trade along the coast of Northern Europe...

– and their role was confirmed under the Great Charter of 1303, which exempted them from paying the customary tolls for foreign merchants.Hanse is the old English word for "group". One response to this was the creation of the Company of the Staple

Merchants of the Staple

The Merchants of the Staple, also known as the Merchant Staplers, was an English company which controlled the export of wool to the continent during the late medieval period....

, a group of merchants established in English-held Calais

Calais

Calais is a town in Northern France in the department of Pas-de-Calais, of which it is a sub-prefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's capital is its third-largest city of Arras....

in 1314 with royal approval, who were granted a monopoly on wool sales to Europe.

Jewish contribution to the English economy

The Jewish community in England continued to provide essential money-lending and banking services that were otherwise banned by the usuryUsury

Usury Originally, when the charging of interest was still banned by Christian churches, usury simply meant the charging of interest at any rate . In countries where the charging of interest became acceptable, the term came to be used for interest above the rate allowed by law...

laws, and grew in the 12th century by Jewish immigrants fleeing the fighting around Rouen

Rouen

Rouen , in northern France on the River Seine, is the capital of the Haute-Normandie region and the historic capital city of Normandy. Once one of the largest and most prosperous cities of medieval Europe , it was the seat of the Exchequer of Normandy in the Middle Ages...

. The Jewish community spread beyond London to eleven major English cities, primarily the major trading hubs in the east of England with functioning mints, all with suitable castles for protection of the often persecuted Jewish minority. By the time of the Anarchy and the reign of Stephen, the communities were flourishing and providing financial loans to the king.

Under Henry II, the Jewish financial community continued to grow richer still. All major towns had Jewish centres, and even smaller towns, such as Windsor, saw visits by travelling Jewish merchants. Henry II used the Jewish community as "instruments for the collection of money for the Crown", and placed them under royal protection. The Jewish community at York

York

York is a walled city, situated at the confluence of the Rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. The city has a rich heritage and has provided the backdrop to major political events throughout much of its two millennia of existence...

lent extensively to fund the Cistercian order's acquisition of land and prospered considerably. Some Jewish merchants grew extremely wealthy, Aaron of Lincoln

Aaron of Lincoln

Aaron of Lincoln was an English Jewish financier . He is believed to have been the wealthiest man in 12th century Britain; it is estimated that his wealth exceeded that of the King. He is first mentioned in the English pipe-roll of 1166 as creditor of King Henry II for sums amounting to £616 12s...

so much that upon his death a special royal department had to be established to unpick his financial holdings and affairs.

By the end of Henry's reign the king ceased to borrow from the Jewish community and instead turned to an aggressive campaign of tallage

Tallage

Tallage or talliage may have signified at first any tax, but became in England and France a land use or land tenure tax. Later in England it was further limited to assessments by the crown upon cities, boroughs, and royal domains...

taxation and fines. Financial and anti-Semite violence grew under Richard I. After the massacre of the York community

York Castle

York Castle in the city of York, England, is a fortified complex comprising, over the last nine centuries, a sequence of castles, prisons, law courts and other buildings on the south side of the River Foss. The now-ruinous keep of the medieval Norman castle is sometimes referred to as Clifford's...

, in which numerous financial records were destroyed, seven towns were nominated to separately store Jewish bonds and money records and this arrangement ultimately evolved into the Exchequer of the Jews

Exchequer of the Jews

The Exchequer of the Jews was a division of the Court of Exchequer at Westminster, which recorded and regulated the taxes and the law-cases of the Jews in England...

. After an initially peaceful start to John's reign, the king again began to extort money from the Jewish community, imprisoning the wealthier members, including Isaac of Norwich

Isaac of Norwich

Isaac of Norwich or Isaac ben Eliav was a Jewish-English financier of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. He was among the Jews imprisoned by King John of England in 1210. It is possible that at this time a house of his in London fell into the hands of the king and was afterward transferred to...

, until a huge, new taillage was paid. During the Baron's War

First Barons' War

The First Barons' War was a civil war in the Kingdom of England, between a group of rebellious barons—led by Robert Fitzwalter and supported by a French army under the future Louis VIII of France—and King John of England...

of 1215–17, the Jews were subjected to fresh anti-Semitic attacks. Henry III

Henry III of England

Henry III was the son and successor of John as King of England, reigning for 56 years from 1216 until his death. His contemporaries knew him as Henry of Winchester. He was the first child king in England since the reign of Æthelred the Unready...

restored some order and Jewish money-lending became sufficiently successful again to allow fresh taxation. The Jewish community became poorer towards the end of the century and was finally expelled from England in 1290 by Edward I, being largely replaced by foreign merchants.

Governance and taxation

During the 12th century the Norman kings attempted to formalise the feudal governance system initially created after the invasion. After the invasion the king had enjoyed a combination of income from his own demesne lands, the Anglo-Saxon geld tax and fines. Successive kings found that they needed additional revenues, especially in order to pay for mercenaryMercenary

A mercenary, is a person who takes part in an armed conflict based on the promise of material compensation rather than having a direct interest in, or a legal obligation to, the conflict itself. A non-conscript professional member of a regular army is not considered to be a mercenary although he...

forces. One way of doing this was to exploit the feudal system, and kings adopted the French feudal aid

Feudal aid

Feudal aid, or just plain aid is the legal term for one of the financial duties required of a tenant or vassal to his lord. Variations on the feudal aid were collected in England, France, Germany and Italy during the Middle Ages, although the exact circumstances varied.-Origin:The term originated...

model, a levy of money imposed on feudal subordinates when necessary; another method was to exploit the scutage

Scutage

The form of taxation known as scutage, in the law of England under the feudal system, allowed a knight to "buy out" of the military service due to the Crown as a holder of a knight's fee held under the feudal land tenure of knight-service. Its name derived from shield...

system, in which feudal military service could be transmuted to a cash payment to the king. Taxation was also an option, although the old geld tax was increasingly ineffective due to a growing number of exemptions. Instead, a succession of kings created alternative land taxes, such as the tallage

Tallage

Tallage or talliage may have signified at first any tax, but became in England and France a land use or land tenure tax. Later in England it was further limited to assessments by the crown upon cities, boroughs, and royal domains...

and carucage

Carucage

Carucage was a medieval English land tax introduced by King Richard I in 1194, based on the size—variously calculated—of the estate owned by the taxpayer. It was a replacement for the danegeld, last imposed in 1162, which had become difficult to collect because of an increasing number of exemptions...

taxes. These were increasingly unpopular and, along with the feudal charges, were condemned and constrained in the Magna Carta

Magna Carta

Magna Carta is an English charter, originally issued in the year 1215 and reissued later in the 13th century in modified versions, which included the most direct challenges to the monarch's authority to date. The charter first passed into law in 1225...

of 1215. As part of the formalisation of the royal finances, Henry I created the Chancellor of the Exchequer

Chancellor of the Exchequer

The Chancellor of the Exchequer is the title held by the British Cabinet minister who is responsible for all economic and financial matters. Often simply called the Chancellor, the office-holder controls HM Treasury and plays a role akin to the posts of Minister of Finance or Secretary of the...

, a post which would lead to the maintenance of the Pipe rolls

Pipe Rolls