Edward VIII abdication crisis

Encyclopedia

Constitutional crisis

A constitutional crisis is a situation that the legal system's constitution or other basic principles of operation appear unable to resolve; it often results in a breakdown in the orderly operation of government...

in the British Empire

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

was caused by King-Emperor

King-Emperor

A king-emperor, the female equivalent being queen-empress, is a sovereign ruler who is simultaneously a king of one territory and emperor of another...

Edward VIII

Edward VIII of the United Kingdom

Edward VIII was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth, and Emperor of India, from 20 January to 11 December 1936.Before his accession to the throne, Edward was Prince of Wales and Duke of Cornwall and Rothesay...

's proposal to marry Wallis Simpson, a twice-divorced American

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

socialite

Socialite

A socialite is a person who participates in social activities and spends a significant amount of time entertaining and being entertained at fashionable upper-class events....

.

The marriage was opposed by the King's governments in the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

and the autonomous Dominions of the British Commonwealth

Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, normally referred to as the Commonwealth and formerly known as the British Commonwealth, is an intergovernmental organisation of fifty-four independent member states...

. Religious, legal, political, and moral objections were raised. As British monarch

Monarchy of the United Kingdom

The monarchy of the United Kingdom is the constitutional monarchy of the United Kingdom and its overseas territories. The present monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, has reigned since 6 February 1952. She and her immediate family undertake various official, ceremonial and representational duties...

, Edward was the nominal head of the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

, which did not allow divorced people to remarry if their ex-spouses were still alive; so it was widely believed that Edward could not marry Mrs Simpson and remain on the throne. Mrs Simpson was perceived to be politically and socially unsuitable as a consort because of her two failed marriages. It was widely assumed by the Establishment

The Establishment

The Establishment is a term used to refer to a visible dominant group or elite that holds power or authority in a nation. The term suggests a closed social group which selects its own members...

that she was driven by love of money or position rather than love for the King. Despite the opposition, Edward declared that he loved Mrs Simpson and intended to marry her whether the governments approved or not.

The widespread unwillingness to accept Mrs Simpson as the King's consort, and the King's refusal to give her up, led to Edward's abdication

Abdication

Abdication occurs when a monarch, such as a king or emperor, renounces his office.-Terminology:The word abdication comes derives from the Latin abdicatio. meaning to disown or renounce...

in December 1936. He remains the only British monarch to have voluntarily renounced the throne since the Anglo-Saxon period

Anglo-Saxons

Anglo-Saxon is a term used by historians to designate the Germanic tribes who invaded and settled the south and east of Great Britain beginning in the early 5th century AD, and the period from their creation of the English nation to the Norman conquest. The Anglo-Saxon Era denotes the period of...

. He was succeeded by his brother Albert, who took the regnal name

Regnal name

A regnal name, or reign name, is a formal name used by some monarchs and popes during their reigns. Since medieval times, monarchs have frequently chosen to use a name different from their own personal name when they inherit a throne....

George VI

George VI of the United Kingdom

George VI was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death...

. Edward was given the title His Royal Highness the Duke of Windsor

Duke of Windsor

The title Duke of Windsor was created in the Peerage of the United Kingdom in 1937 for Prince Edward, the former King Edward VIII, following his abdication in December 1936. The dukedom takes its name from the town where Windsor Castle, a residence of English monarchs since the Norman Conquest, is...

following his abdication, and he married Mrs Simpson the following year. They remained married until his death 35 years later.

Edward and Mrs Simpson

.jpg)

George V of the United Kingdom

George V was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 through the First World War until his death in 1936....

, as King-Emperor

King-Emperor

A king-emperor, the female equivalent being queen-empress, is a sovereign ruler who is simultaneously a king of one territory and emperor of another...

of the British Empire on 20 January 1936. He was a bachelor, but for the previous few years he had often been accompanied at private social events by Wallis Simpson, the American wife of British shipping executive Ernest Aldrich Simpson

Ernest Aldrich Simpson

Ernest Aldrich Simpson was a British shipping executive best known as the second husband of Wallis Simpson, who later would marry the former Edward VIII of the United Kingdom...

. Mr Simpson was Wallis's second husband; her first marriage, to U.S. Navy

United States Navy

The United States Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the seven uniformed services of the United States. The U.S. Navy is the largest in the world; its battle fleet tonnage is greater than that of the next 13 largest navies combined. The U.S...

pilot Win Spencer

Earl Winfield Spencer, Jr.

Commander Earl Winfield Spencer, Jr. was a pioneering U.S. Navy pilot who served as the first commanding officer of Naval Air Station, San Diego. He was the first husband of Wallis, Duchess of Windsor....

, had ended in divorce in 1927. During 1936, Mrs Simpson attended more official functions as the King's guest and, although her name appeared regularly in the Court Circular

Court Circular

The Court Circular is the official record that lists the engagements carried out by the Monarch of the United Kingdom and of the other Commonwealth Realms; the Royal Family; and appointments to their staff and to the court. It is issued by Buckingham Palace and printed a day in arrears at the back...

, the name of her husband was conspicuously absent. In the summer of that year, the King eschewed the traditional prolonged stay at Balmoral

Balmoral Castle

Balmoral Castle is a large estate house in Royal Deeside, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. It is located near the village of Crathie, west of Ballater and east of Braemar. Balmoral has been one of the residences of the British Royal Family since 1852, when it was purchased by Queen Victoria and her...

, opting instead to holiday with Mrs Simpson in the Eastern Mediterranean on board the steam yacht Nahlin. The cruise was widely covered in the American and continental European press, but the British press maintained a self-imposed silence on the King's trip. Nevertheless, expatriate Britons and Canadians, who had access to the foreign reports, were largely scandalised by the coverage.

By October, it was rumoured in high society and abroad that Edward intended to marry Mrs Simpson as soon as she was free to do so. At the end of that month, the crisis came to a head when Mrs Simpson filed for divorce and the American press announced that marriage between her and the King was imminent. On 13 November, the King's private secretary, Alec Hardinge

Alexander Hardinge, 2nd Baron Hardinge of Penshurst

Alexander Henry Louis Hardinge, 2nd Baron Hardinge of Penshurst GCB GCVO MC PC was Private Secretary to the Sovereign during the Abdication Crisis of Edward VIII and during most of the Second World War....

, wrote to the King warning him that: "The silence in the British Press on the subject of Your Majesty's friendship with Mrs Simpson is not going to be maintained ... Judging by the letters from British subjects living in foreign countries where the Press has been outspoken, the effect will be calamitous." Senior British ministers knew that Hardinge had written to the King and may have helped him to draft the letter.

The following Monday, 16 November, the King invited the British prime minister

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and...

, Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, KG, PC was a British Conservative politician, who dominated the government in his country between the two world wars...

, to Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace, in London, is the principal residence and office of the British monarch. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is a setting for state occasions and royal hospitality...

and informed him that he intended to marry Mrs Simpson. Baldwin said in response that such a marriage would not be acceptable to the people, stating: "... the Queen becomes the Queen of the country. Therefore in the choice of a Queen the voice of the people must be heard." Baldwin's view was shared by the Australian High Commissioner

High Commissioner

High Commissioner is the title of various high-ranking, special executive positions held by a commission of appointment.The English term is also used to render various equivalent titles in other languages.-Bilateral diplomacy:...

in London, Stanley Bruce

Stanley Bruce

Stanley Melbourne Bruce, 1st Viscount Bruce of Melbourne, CH, MC, FRS, PC , was an Australian politician and diplomat, and the eighth Prime Minister of Australia. He was the second Australian granted an hereditary peerage of the United Kingdom, but the first whose peerage was formally created...

, who was a former Australian prime minister

Prime Minister of Australia

The Prime Minister of the Commonwealth of Australia is the highest minister of the Crown, leader of the Cabinet and Head of Her Majesty's Australian Government, holding office on commission from the Governor-General of Australia. The office of Prime Minister is, in practice, the most powerful...

. On the same day that Hardinge wrote to the King, Bruce met Hardinge and then wrote to Baldwin expressing horror at the idea of a marriage between the King and Mrs Simpson. Governor General of Canada

Governor General of Canada

The Governor General of Canada is the federal viceregal representative of the Canadian monarch, Queen Elizabeth II...

Lord Tweedsmuir

John Buchan, 1st Baron Tweedsmuir

John Buchan, 1st Baron Tweedsmuir was a Scottish novelist, historian and Unionist politician who served as Governor General of Canada, the 15th since Canadian Confederation....

conveyed to Buckingham Palace and Baldwin his observations of Canadians' deep affection for the King, but also that Canadian puritanism—both Catholic and Protestant—would be outraged if Edward married a divorcée.

Nevertheless, the British Press remained quiet on the subject, until Alfred Blunt

Alfred Blunt

Alfred Blunt , second bishop of Bradford . He is best known for a speech that exacerbated the Abdication Crisis of Edward VIII....

, Bishop of Bradford

Bishop of Bradford

The Bishop of Bradford is the Ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Bradford, in the Province of YorkThe diocese covers the extreme west of Yorkshire, and has its see in the city of Bradford where the seat is located at the Cathedral Church of Saint Peter.The Bishop's residence is...

, gave a speech to his Diocesan Conference on 1 December. In it he alluded to the King's need of divine grace

Divine grace

In Christian theology, grace is God’s gift of God’s self to humankind. It is understood by Christians to be a spontaneous gift from God to man - "generous, free and totally unexpected and undeserved" - that takes the form of divine favour, love and clemency. It is an attribute of God that is most...

saying: "We hope that he is aware of his need. Some of us wish that he gave more positive signs of his awareness." The press took this for the first public comment by a notable person on the crisis and it became front page news the following day. When asked about it later, however, the bishop claimed he had not heard of Mrs Simpson at the time he wrote the speech.

Acting on the advice of Edward's staff, Mrs Simpson left Britain for the south of France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

on 3 December in an attempt to escape intense press attention. Both she and the King were devastated by the separation. At a tearful farewell, the King told her, "I shall never give you up."

Societal

Edward's desire to modernise the monarchy and make it more accessible, though popular with many people, was feared by the British Establishment. Edward upset the aristocracy by treating their traditions and ceremonies with disdain, and many were offended by his abandonment of accepted social norms and mores.Religious

Edward was the first British monarch to propose marrying a divorced woman or marrying after divorce. Although Henry VIIIHenry VIII of England

Henry VIII was King of England from 21 April 1509 until his death. He was Lord, and later King, of Ireland, as well as continuing the nominal claim by the English monarchs to the Kingdom of France...

famously separated the Church of England from Rome in order to acquire an annulment of his first marriage, he never divorced; his marriages were annulled. At the time, the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

did not allow divorced persons to remarry in church while a former spouse was still living. The consensus view held that Edward could not stay on the throne if he married Wallis Simpson, a divorcée who would soon have two living ex-husbands, as it would conflict with his ex officio role as Supreme Governor of the Church of England

Supreme Governor of the Church of England

The Supreme Governor of the Church of England is a title held by the British monarchs which signifies their titular leadership over the Church of England. Although the monarch's authority over the Church of England is not strong, the position is still very relevant to the church and is mostly...

.

Legal

Wallis's first divorce (in the United States on the grounds of "emotional incompatibility") was not recognised by the Church of England and, if challenged in the English courts, might not have been recognised under English law. At that time the church and English law considered adultery to be the only grounds for divorce. Consequently, under this argument, her second (and third) marriages would have been bigamous and invalid.Moral

Mary of Teck

Mary of Teck was the queen consort of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Empress of India, as the wife of King-Emperor George V....

, was even told that Mrs Simpson might have held some sort of sexual control over Edward, as she had released him from an undefined sexual dysfunction through practices learnt in a Chinese brothel. This view was partially shared by Dr. Alan Campbell Don

Alan Campbell Don

Alan Campbell Don KCVO was a trustee of the National Portrait Gallery author of the Scottish Book of Common Prayer, Chaplain and Secretary to Cosmo Lang, Archbishop of Canterbury between 1931 and 1941, Chaplain to the Speaker of the House of Commons between 1936 and 1946, and Dean of Westminster...

, Chaplain to the Archbishop of Canterbury

Archbishop of Canterbury

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. In his role as head of the Anglican Communion, the archbishop leads the third largest group...

, who wrote that he suspected the King "is sexually abnormal which may account for the hold Mrs. S. has over him". Even Edward VIII's official biographer, Philip Ziegler

Philip Ziegler

-Background:Born in Ringwood, Ziegler was educated at St Cyprian's School, Eastbourne, and went with the school when it merged with Summer Fields School, Oxford. He was afterwards at Eton College and New College, Oxford...

, noted that: "There must have been some sort of sadomachistic relationship ... [Edward] relished the contempt and bullying she bestowed on him."

Police detectives following Mrs Simpson reported back that while involved with Edward, she was also involved in another sexual relationship, with a married car mechanic and salesman named Guy Trundle. This may well have been passed on to senior figures in the Establishment, including members of the Royal Family. A third lover has also been suggested, the Duke of Leinster

Edward FitzGerald, 7th Duke of Leinster

Edward FitzGerald, 7th Duke of Leinster, etc. , known as Lord Edward FitzGerald before 1922 was Ireland's Premier Peer of the Realm.-Life:...

. Joseph Kennedy, the American ambassador, described her as a "tart", and his wife, Rose Kennedy, refused to dine with her. Edward, however, was either unaware of these allegations, or chose to ignore them.

Wallis was perceived to be pursuing Edward for his money; his equerry

Equerry

An equerry , and related to the French word "écuyer" ) is an officer of honour. Historically, it was a senior attendant with responsibilities for the horses of a person of rank. In contemporary use, it is a personal attendant, usually upon a Sovereign, a member of a Royal Family, or a national...

wrote that she would eventually leave him after "having secured the cash". The future prime minister Neville Chamberlain

Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain FRS was a British Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. Chamberlain is best known for his appeasement foreign policy, and in particular for his signing of the Munich Agreement in 1938, conceding the...

wrote in his diary that she was "an entirely unscrupulous woman who is not in love with the King but is exploiting him for her own purposes. She has already ruined him in money and jewels ..."

Political

When Edward visited depressedGreat Depression

The Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

mining villages in Wales

Wales

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and the island of Great Britain, bordered by England to its east and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population of three million, and a total area of 20,779 km²...

his comment that "something must be done" led to concerns amongst elected politicians that he would interfere in political matters, traditionally avoided by constitutional monarchs. Ramsay MacDonald

Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald, PC, FRS was a British politician who was the first ever Labour Prime Minister, leading a minority government for two terms....

, Lord President of the Council

Lord President of the Council

The Lord President of the Council is the fourth of the Great Officers of State of the United Kingdom, ranking beneath the Lord High Treasurer and above the Lord Privy Seal. The Lord President usually attends each meeting of the Privy Council, presenting business for the monarch's approval...

, wrote of the King's comments: "These escapades should be limited. They are an invasion into the field of politics & should be watched constitutionally." As Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales is a title traditionally granted to the heir apparent to the reigning monarch of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the 15 other independent Commonwealth realms...

, Edward had publicly referred to left-wing politicians as "cranks" and made speeches counter to government policy. During his reign as king, his refusal to accept the advice of ministers continued: he opposed the imposition of sanctions on Italy

Kingdom of Italy (1861–1946)

The Kingdom of Italy was a state forged in 1861 by the unification of Italy under the influence of the Kingdom of Sardinia, which was its legal predecessor state...

after its invasion of Ethiopia

Second Italo-Abyssinian War

The Second Italo–Abyssinian War was a colonial war that started in October 1935 and ended in May 1936. The war was fought between the armed forces of the Kingdom of Italy and the armed forces of the Ethiopian Empire...

(then known as "Abyssinia"), refused to receive the deposed Emperor of Ethiopia, and would not support the League of Nations

League of Nations

The League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. It was the first permanent international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace...

.

Although Edward's comments had made him popular in Wales, he became extremely unpopular with the public in Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

following his refusal to open a new wing of Aberdeen Royal Infirmary

Aberdeen Royal Infirmary

Aberdeen Royal Infirmary or ARI is a teaching hospital on the Foresterhill site in Aberdeen, Scotland. It is run by NHS Grampian and has around 900 beds. ARI is a tertiary referral hospital serving a population of over 600,000 across the North of Scotland...

, claiming he could not do so because he was in mourning for his father. On the day after the opening he was pictured in the newspapers cavorting on holiday: he had turned down the public event in favour of meeting Mrs Simpson.

Members of the British government became further dismayed by the proposed marriage after being told that Wallis Simpson was an agent of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

. The Foreign Office obtained leaked dispatches from the German Reich's Ambassador to the United Kingdom, Joachim von Ribbentrop

Joachim von Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop was Foreign Minister of Germany from 1938 until 1945. He was later hanged for war crimes after the Nuremberg Trials.-Early life:...

, which revealed his strong view that opposition to the marriage was motivated by the wish "to defeat those Germanophile forces which had been working through Mrs. Simpson". It was rumoured that Wallis had access to confidential government papers sent to Edward, which he notoriously left unguarded at his Fort Belvedere residence. While Edward was abdicating, the personal protection officers guarding Mrs Simpson in exile in France sent reports to Downing Street

Downing Street

Downing Street in London, England has for over two hundred years housed the official residences of two of the most senior British cabinet ministers: the First Lord of the Treasury, an office now synonymous with that of Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, and the Second Lord of the Treasury, an...

suggesting that she might "flit to Germany".

Files from the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation

Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation is an agency of the United States Department of Justice that serves as both a federal criminal investigative body and an internal intelligence agency . The FBI has investigative jurisdiction over violations of more than 200 categories of federal crime...

, written after the abdication, reveal a further series of claims. The most damaging allege that in 1936, during her affair with King Edward, she was simultaneously having an affair with Ambassador Ribbentrop. The Bureau's source (Duke Carl Alexander of Württemberg, a distant relative of Queen Mary then living as a monk in the US) claimed that Simpson and Ribbentrop had a relationship, and that Ribbentrop sent her 17 carnations every day, one for each occasion they had slept together. The FBI claims were symptomatic of the extremely damaging gossip circulating about the woman who could become queen.

Nationalistic

Relations between the United Kingdom and the United States were strained during the inter-war years and the majority of Britons were reluctant to accept an American as queen consort. At the time, some members of the British upper class looked down on Americans with disdain and considered them socially inferior. In contrast, the American public was clearly in favour of the marriage, as was most of the American press.Options considered

Cabinet of Canada

The Cabinet of Canada is a body of ministers of the Crown that, along with the Canadian monarch, and within the tenets of the Westminster system, forms the government of Canada...

advised Edward against the marriage and urged him to put his duty as king before his feelings for Mrs Simpson, while the British prime minister

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and...

, Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, KG, PC was a British Conservative politician, who dominated the government in his country between the two world wars...

, explicitly advised Edward that the people would be opposed to his marrying Mrs Simpson, indicating that if he did, in direct contravention of his ministers' advice, the government would resign en masse. The King responded, according to his own account later: "I intend to marry Mrs. Simpson as soon as she is free to marry ... if the Government opposed the marriage, as the Prime Minister had given me reason to believe it would, then I was prepared to go." Under pressure from the King, and "startled" at the suggested abdication, Baldwin agreed to take further soundings and suggest three options to the prime ministers of the five Dominion

Dominion

A dominion, often Dominion, refers to one of a group of autonomous polities that were nominally under British sovereignty, constituting the British Empire and British Commonwealth, beginning in the latter part of the 19th century. They have included Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland,...

s of which Edward was also king: Canada

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

, Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

, New Zealand

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

, South Africa

Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa is the historic predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into being on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the previously separate colonies of the Cape, Natal, Transvaal and the Orange Free State...

and the Irish Free State

Irish Free State

The Irish Free State was the state established as a Dominion on 6 December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty, signed by the British government and Irish representatives exactly twelve months beforehand...

. The options were:

- Edward and Mrs Simpson marry and she become queen (a royal marriage);

- Edward and Mrs Simpson marry, but she not become queen, instead receiving some courtesy title (a morganatic marriageMorganatic marriageIn the context of European royalty, a morganatic marriage is a marriage between people of unequal social rank, which prevents the passage of the husband's titles and privileges to the wife and any children born of the marriage...

); or - AbdicationAbdicationAbdication occurs when a monarch, such as a king or emperor, renounces his office.-Terminology:The word abdication comes derives from the Latin abdicatio. meaning to disown or renounce...

for Edward and any potential heirs he might father, allowing him to make any marital decisions without further constitutional implications.

The second option had European precedents, including Edward's own great-grandfather, Duke Alexander of Württemberg

Duke Alexander of Württemberg

Duke Alexander of Württemberg was the father of Prince Francis of Teck and the grandfather of Adolphus Cambridge, 1st Marquess of Cambridge and Queen Mary of Great Britain, wife of King George V....

, but no parallel in British constitutional history. The Commonwealth's prime ministers were consulted, and the majority agreed that there was "no alternative to course (3)". William Lyon Mackenzie King

William Lyon Mackenzie King

William Lyon Mackenzie King, PC, OM, CMG was the dominant Canadian political leader from the 1920s through the 1940s. He served as the tenth Prime Minister of Canada from December 29, 1921 to June 28, 1926; from September 25, 1926 to August 7, 1930; and from October 23, 1935 to November 15, 1948...

(Prime Minister of Canada

Prime Minister of Canada

The Prime Minister of Canada is the primary minister of the Crown, chairman of the Cabinet, and thus head of government for Canada, charged with advising the Canadian monarch or viceroy on the exercise of the executive powers vested in them by the constitution...

), Joseph Lyons

Joseph Lyons

Joseph Aloysius Lyons, CH was an Australian politician. He was Labor Premier of Tasmania from 1923 to 1928 and a Minister in the James Scullin government from 1929 until his resignation from the Labor Party in March 1931...

(Prime Minister of Australia

Prime Minister of Australia

The Prime Minister of the Commonwealth of Australia is the highest minister of the Crown, leader of the Cabinet and Head of Her Majesty's Australian Government, holding office on commission from the Governor-General of Australia. The office of Prime Minister is, in practice, the most powerful...

) and J. B. M. Hertzog (Prime Minister of South Africa) opposed options 1 and 2. Michael Joseph Savage

Michael Joseph Savage

Michael Joseph Savage was the first Labour Prime Minister of New Zealand.- Early life :Born in Tatong, Victoria, Australia, Savage first became involved in politics while working in that state. He emigrated to New Zealand in 1907. There he worked in a variety of jobs, as a miner, flax-cutter and...

(Prime Minister of New Zealand

Prime Minister of New Zealand

The Prime Minister of New Zealand is New Zealand's head of government consequent on being the leader of the party or coalition with majority support in the Parliament of New Zealand...

) rejected option 1 but thought that option 2 "might be possible ... if some solution along these lines were found to be practicable" but "would be guided by the decision of the Home government". Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera was one of the dominant political figures in twentieth century Ireland, serving as head of government of the Irish Free State and head of government and head of state of Ireland...

(prime minister of the Irish Free State

President of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State

The President of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State was the head of government or prime minister of the Irish Free State which existed from 1922 to 1937...

) claimed to be uninterested while also remarking that, as a Roman Catholic country, the Irish Free State did not recognise divorce. He supposed that if the British people would not accept Mrs Simpson then abdication was the only possible solution. On 24 November, Baldwin consulted the three leading opposition politicians in Britain: Leader of the Opposition Clement Attlee

Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, KG, OM, CH, PC, FRS was a British Labour politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951, and as the Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955...

, Liberal

Liberal Party (UK)

The Liberal Party was one of the two major political parties of the United Kingdom during the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a third party of negligible importance throughout the latter half of the 20th Century, before merging with the Social Democratic Party in 1988 to form the present day...

leader Sir Archibald Sinclair

Archibald Sinclair, 1st Viscount Thurso

Archibald Henry Macdonald Sinclair, 1st Viscount Thurso KT, CMG, PC , known as Sir Archibald Sinclair, Bt between 1912 and 1952, and often as Archie Sinclair, was a British politician and leader of the Liberal Party....

and Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

. Sinclair and Attlee agreed that options 1 and 2 were unacceptable and Churchill pledged to support the government.

Churchill did not support the government, however. In July he had advised the King's legal counsel, Walter Monckton

Walter Monckton, 1st Viscount Monckton of Brenchley

Walter Turner Monckton, 1st Viscount Monckton of Brenchley, GCVO, KCMG, MC, PC was a British politician.-Early years:...

, against the divorce but his advice was ignored. As soon as the affair became public knowledge, Churchill started to pressure Baldwin and the King to delay any decisions until parliament and the people had been consulted. In a private letter to Geoffrey Dawson

Geoffrey Dawson

George Geoffrey Dawson was editor of The Times from 1912 to 1919 and again from 1923 until 1941. His original last name was Robinson, but he changed it in 1917.-Early life:...

, the editor of The Times

The Times

The Times is a British daily national newspaper, first published in London in 1785 under the title The Daily Universal Register . The Times and its sister paper The Sunday Times are published by Times Newspapers Limited, a subsidiary since 1981 of News International...

newspaper, Churchill suggested that a delay would be beneficial because, given time, the King might fall out of love with Mrs Simpson. Baldwin rejected the request for delay, presumably because he preferred to resolve the crisis quickly. Supporters of the King alleged a conspiracy between Baldwin, Geoffrey Dawson, and Cosmo Gordon Lang, the Archbishop of Canterbury

Archbishop of Canterbury

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. In his role as head of the Anglican Communion, the archbishop leads the third largest group...

. The royal physician Bertrand Dawson

Bertrand Dawson, 1st Viscount Dawson of Penn

Bertrand Edward Dawson, 1st Viscount Dawson of Penn, GCVO, KCB, KCMG, PC, FRCP was a physician to the British Royal Family and President of the Royal College of Physicians.-Early life and education:...

was possibly involved in a plan to force the prime minister to retire on the grounds of heart disease, but he eventually accepted, on the evidence of an early electrocardiograph, that Baldwin's heart was sound.

Political support for the King was scattered, and comprised politicians outside of the mainstream parties such as Churchill, Oswald Mosley

Oswald Mosley

Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley, 6th Baronet, of Ancoats, was an English politician, known principally as the founder of the British Union of Fascists...

, and the Communists

Communist Party of Great Britain

The Communist Party of Great Britain was the largest communist party in Great Britain, although it never became a mass party like those in France and Italy. It existed from 1920 to 1991.-Formation:...

. David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor OM, PC was a British Liberal politician and statesman...

also supported the King, although he disliked Mrs Simpson. He was, however, unable to take any active role in the crisis because he was on holiday in Jamaica

Jamaica

Jamaica is an island nation of the Greater Antilles, in length, up to in width and 10,990 square kilometres in area. It is situated in the Caribbean Sea, about south of Cuba, and west of Hispaniola, the island harbouring the nation-states Haiti and the Dominican Republic...

with his mistress. In early December, rumours circulated that the King's supporters would join together in a "King's Party" led by Churchill. However, there was no concerted effort to form an organised movement and Churchill had no intention of leading one. Nevertheless, the rumours damaged the King and Churchill severely, as Members of Parliament were horrified at the idea of the King interfering in politics.

The letters and diaries of working-class people and ex-servicemen generally demonstrate support for the King, while those from the middle and upper classes tend to express indignation and distaste. The Times

The Times

The Times is a British daily national newspaper, first published in London in 1785 under the title The Daily Universal Register . The Times and its sister paper The Sunday Times are published by Times Newspapers Limited, a subsidiary since 1981 of News International...

, The Morning Post, the Daily Herald, and newspapers owned by Lord Kemsley, such as The Daily Telegraph

The Daily Telegraph

The Daily Telegraph is a daily morning broadsheet newspaper distributed throughout the United Kingdom and internationally. The newspaper was founded by Arthur B...

, opposed the marriage. On the other hand, the Express

Daily Express

The Daily Express switched from broadsheet to tabloid in 1977 and was bought by the construction company Trafalgar House in the same year. Its publishing company, Beaverbrook Newspapers, was renamed Express Newspapers...

and Mail

Daily Mail

The Daily Mail is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper owned by the Daily Mail and General Trust. First published in 1896 by Lord Northcliffe, it is the United Kingdom's second biggest-selling daily newspaper after The Sun. Its sister paper The Mail on Sunday was launched in 1982...

newspapers, owned by Lord Beaverbrook

Max Aitken, 1st Baron Beaverbrook

William Maxwell "Max" Aitken, 1st Baron Beaverbrook, Bt, PC, was a Canadian-British business tycoon, politician, and writer.-Early career in Canada:...

and Lord Rothermere, respectively, appeared to support a morganatic marriage. The King estimated that the newspapers in favour had a circulation of 12.5 million, and those against had 8.5 million.

Backed by Churchill and Beaverbrook, Edward proposed to broadcast a speech indicating his desire to remain on the throne or to be recalled to it if forced to abdicate, while marrying Mrs Simpson morganatically. In one section, Edward proposed to say:

Baldwin and the British Cabinet

Cabinet of the United Kingdom

The Cabinet of the United Kingdom is the collective decision-making body of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom, composed of the Prime Minister and some 22 Cabinet Ministers, the most senior of the government ministers....

blocked the speech, saying that it would shock many people and would be a grave breach of constitutional principles. By modern convention, the sovereign could only act with the advice and counsel of ministers drawn from, or approved by, the King's various parliaments. In seeking the people's support against the government, Edward was opting to oppose the binding advice of his ministers, and instead act as a private individual. Edward's British ministers felt that, in proposing the speech, Edward had revealed his disdainful attitude towards constitutional conventions and threatened the political neutrality of the Crown.

On 5 December, having in effect been told that he could not keep the throne and marry Mrs Simpson, and having had his request to broadcast to the Empire to explain "his side of the story" blocked on constitutional grounds, Edward chose the third option.

Legal manoeuvres

Following Mrs Simpson's divorce hearing on 27 October 1936, her solicitor, John Theodore GoddardTheodore Goddard

Theodore Goddard was an English law firm based in London. The firm merged with Addleshaw Booth & Co on 1 May 2003 to become Addleshaw Goddard...

, became concerned that there would be a "patriotic" citizen's intervention (a legal device to block the divorce), and that such an intervention would be successful. The courts could not grant a collaborative divorce (a dissolution of marriage consented to by both parties), and so the case was being handled as if it were an undefended at-fault divorce brought against Mr Simpson, with Mrs Simpson as the innocent, injured party. The divorce action would fail if the citizen's intervention showed that Mrs Simpson had colluded with her husband by, for example, conniving in

Connivance

A legal finding of connivance may be made when an accuser has assisted in the act about which they are complaining. In some legal jurisdictions, and for certain behaviors, it may prevent the accuser from prevailing....

or staging the appearance of his adultery so that she could marry someone else. On Monday 7 December 1936, the King heard that Goddard planned to fly to the south of France to see his client. The King summoned him and expressly forbade him to make the journey, fearing the visit might put doubts in Mrs Simpson's mind. Goddard went straight to Downing Street

10 Downing Street

10 Downing Street, colloquially known in the United Kingdom as "Number 10", is the headquarters of Her Majesty's Government and the official residence and office of the First Lord of the Treasury, who is now always the Prime Minister....

to see Baldwin, as a result of which he was provided with an aeroplane to take him directly to Cannes

Cannes

Cannes is one of the best-known cities of the French Riviera, a busy tourist destination and host of the annual Cannes Film Festival. It is a Commune of France in the Alpes-Maritimes department....

.

Upon his arrival, Goddard warned his client that a citizen's intervention, should it arise, was likely to succeed. It was, according to Goddard, his duty to advise her to withdraw her divorce petition. Mrs Simpson refused, but they both telephoned the King to inform him that she was willing to give him up so that he could remain King. It was, however, too late; the King had already made up his mind to go, even if he could not marry Mrs Simpson. Indeed, as the belief that the abdication was inevitable gathered strength, Goddard stated that: "[his] client was ready to do anything to ease the situation but the other end of the wicket [Edward VIII] was determined".

Goddard had a weak heart and had never flown before, so he asked his doctor, William Kirkwood, to accompany him on the trip. As Kirkwood was a resident at a maternity hospital, his presence led to false speculation that Mrs Simpson was pregnant, and even that she was having an abortion. The press excitedly reported that the solicitor had flown to Mrs Simpson accompanied by a gynaecologist and an anaesthetist (who was actually the lawyer's clerk).

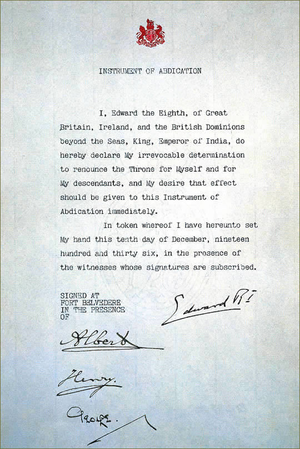

Abdication

Fort Belvedere, Surrey

Fort Belvedere is a country house on Shrubs Hill in Windsor Great Park, England, very near Sunningdale, Berkshire, but actually over the border in the borough of Runnymede in Surrey. It is a former royal residence - from 1750 to 1976 - and is most famous for being the home of King Edward VIII. It...

, on 10 December, Edward VIII's written abdication notice was witnessed by his three younger brothers: Prince Albert, Duke of York (who succeeded Edward as George VI

George VI of the United Kingdom

George VI was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death...

); Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester

Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester

The Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester was a soldier and member of the British Royal Family, the third son of George V of the United Kingdom and Queen Mary....

; and Prince George, Duke of Kent

Prince George, Duke of Kent

Prince George, Duke of Kent was a member of the British Royal Family, the fourth son of George V and Mary of Teck, and younger brother of Edward VIII and George VI...

. The following day, it was given legislative form by special Act of Parliament

Act of Parliament

An Act of Parliament is a statute enacted as primary legislation by a national or sub-national parliament. In the Republic of Ireland the term Act of the Oireachtas is used, and in the United States the term Act of Congress is used.In Commonwealth countries, the term is used both in a narrow...

(His Majesty's Declaration of Abdication Act 1936

His Majesty's Declaration of Abdication Act 1936

His Majesty's Declaration of Abdication Act 1936 was the Act of the British Parliament that allowed King Edward VIII to abdicate the throne, and passed succession to his brother Prince Albert, Duke of York . The Act also excluded any possible future descendants of Edward from the line of succession...

). Under changes introduced in 1931 by the Statute of Westminster

Statute of Westminster 1931

The Statute of Westminster 1931 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Passed on 11 December 1931, the Act established legislative equality for the self-governing dominions of the British Empire with the United Kingdom...

, a single Crown

The Crown

The Crown is a corporation sole that in the Commonwealth realms and any provincial or state sub-divisions thereof represents the legal embodiment of governance, whether executive, legislative, or judicial...

for the entire empire had been replaced by multiple crowns, one for each Dominion

Dominion

A dominion, often Dominion, refers to one of a group of autonomous polities that were nominally under British sovereignty, constituting the British Empire and British Commonwealth, beginning in the latter part of the 19th century. They have included Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland,...

, worn by a single monarch in an organisation then known as the British Commonwealth

Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, normally referred to as the Commonwealth and formerly known as the British Commonwealth, is an intergovernmental organisation of fifty-four independent member states...

. Edward's abdication required the consent of each Commonwealth state, which was duly given; by the parliament of Australia, which was at the time in session, and by the governments of the other Dominions, whose parliaments were in recess. However, the government of the Irish Free State

Irish Free State

The Irish Free State was the state established as a Dominion on 6 December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty, signed by the British government and Irish representatives exactly twelve months beforehand...

, taking the opportunity presented by the crisis and in a major step towards its eventual transition to a republic

Republic of Ireland

Ireland , described as the Republic of Ireland , is a sovereign state in Europe occupying approximately five-sixths of the island of the same name. Its capital is Dublin. Ireland, which had a population of 4.58 million in 2011, is a constitutional republic governed as a parliamentary democracy,...

, passed an amendment to its constitution to remove references to the Crown. The King's abdication was recognised a day later in the External Relations Act of the Irish Free State and legislation eventually passed in South Africa declared that the abdication took effect there on 10 December. It was Edward's Royal Assent

Royal Assent

The granting of royal assent refers to the method by which any constitutional monarch formally approves and promulgates an act of his or her nation's parliament, thus making it a law...

to these Acts, rather than his abdication notice, which gave legal effect to the abdication. As Edward VIII had not been crowned, his planned coronation

Coronation of the British monarch

The coronation of the British monarch is a ceremony in which the monarch of the United Kingdom is formally crowned and invested with regalia...

date became that of his brother Albert, now styled George VI

George VI of the United Kingdom

George VI was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death...

, instead.

Edward's supporters felt that he had "been hounded from the throne by that arch humbug Baldwin", but many members of the Establishment were relieved by Edward's departure. As Edward's own Assistant Private Secretary, Alan Lascelles

Alan Lascelles

Sir Alan Frederick "Tommy" Lascelles, GCB, GCVO, CMG, MC was a British courtier and civil servant who held several positions in the first half of the twentieth century, culminating in his position as Private Secretary to both King George VI and to Queen Elizabeth II...

, had told Baldwin as early as 1927: "I can't help thinking that the best thing that could happen to him, and to the country, would be for him to break his neck."

On the day his reign officially ended, 11 December 1936, Edward made a BBC radio broadcast from Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a medieval castle and royal residence in Windsor in the English county of Berkshire, notable for its long association with the British royal family and its architecture. The original castle was built after the Norman invasion by William the Conqueror. Since the time of Henry I it...

; no longer king, he was introduced by Sir John Reith

John Reith, 1st Baron Reith

John Charles Walsham Reith, 1st Baron Reith, KT, GCVO, GBE, CB, TD, PC was a Scottish broadcasting executive who established the tradition of independent public service broadcasting in the United Kingdom...

as "His Royal Highness Prince Edward". The official address had been polished by Churchill and was moderate in tone, speaking about Edward's inability to do his job "as I would have wished" without the support of "the woman I love". Edward's reign had lasted 327 days, the shortest of any British monarch since the disputed reign of Lady Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey , also known as The Nine Days' Queen, was an English noblewoman who was de facto monarch of England from 10 July until 19 July 1553 and was subsequently executed...

over 380 years earlier. The day following the broadcast he left Britain for Austria

Austria

Austria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

.

Duke and Duchess of Windsor

George VI gave his elder brother the title of Duke of WindsorDuke of Windsor

The title Duke of Windsor was created in the Peerage of the United Kingdom in 1937 for Prince Edward, the former King Edward VIII, following his abdication in December 1936. The dukedom takes its name from the town where Windsor Castle, a residence of English monarchs since the Norman Conquest, is...

with the style His Royal Highness on 12 December 1936. On 3 May the following year, Mrs Simpson's divorce was made final. The case was handled quietly, and it barely featured in some newspapers. The Times

The Times

The Times is a British daily national newspaper, first published in London in 1785 under the title The Daily Universal Register . The Times and its sister paper The Sunday Times are published by Times Newspapers Limited, a subsidiary since 1981 of News International...

was especially disingenuous, printing a single sentence below a seemingly unconnected report announcing the Duke's departure from Austria. When the Duke married Mrs Simpson in France on 3 June 1937, she became the Duchess of Windsor, but, much to Edward's disgust, was not styled Her Royal Highness.

The Duke of Windsor lived in retirement in France for most of the rest of his life. His brother gave him a tax-free allowance, which the Duke supplemented by writing his memoirs and by illegal currency trading. He also profited from the sale of Balmoral Castle

Balmoral Castle

Balmoral Castle is a large estate house in Royal Deeside, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. It is located near the village of Crathie, west of Ballater and east of Braemar. Balmoral has been one of the residences of the British Royal Family since 1852, when it was purchased by Queen Victoria and her...

and Sandringham House

Sandringham House

Sandringham House is a country house on of land near the village of Sandringham in Norfolk, England. The house is privately owned by the British Royal Family and is located on the royal Sandringham Estate, which lies within the Norfolk Coast Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.-History and current...

to George VI. Both estates are private property and not part of the Royal Estate, and were therefore inherited and owned by Edward, regardless of the abdication.

During World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, Edward served as Governor of the Bahamas, where he was plagued by rumours and accusations that he was pro-Nazi. He reportedly told an acquaintance: "After the war is over and Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

will crush the Americans ... we'll take over ... They [the Commonwealth] don't want me as their king, but I'll soon be back as their leader." He also told a journalist that "it would be a tragic thing for the world if Hitler was overthrown". Comments like these reinforced the belief that the Duke and Duchess held Nazi sympathies and the effect of the abdication crisis of 1936 was to force off the throne a man with extreme political views. The Duke explained his views in the New York

New York

New York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

Daily News of 13 December 1966: "... it was in Britain's interest and in Europe's too, that Germany be encouraged to strike east and smash Communism forever ... I thought the rest of us could be fence-sitters while the Nazis and the Reds slogged it out." However, claims that Edward would have been a threat or that he was removed by a political conspiracy to dethrone him remain speculative, and "persist largely because since 1936 the contemporary public considerations have lost most of their force and so seem, wrongly, to provide insufficient explanation for the King's departure".

Cultural influence

In 2005, the wedding of Charles, Prince of Wales, and Camilla Parker BowlesWedding of Charles, Prince of Wales and Camilla Parker Bowles

The wedding of Charles, Prince of Wales, and Camilla Parker Bowles took place in a civil ceremony at Windsor Guildhall, on 9 April 2005. The ceremony, conducted in the presence of the couples' families, was followed by a Church of England service of blessing at St George's Chapel...

had similarities to that of Edward and Wallis. Just like Mrs Simpson in 1936, Mrs Parker Bowles was a divorcée whose previous husband, Andrew Parker Bowles

Andrew Parker Bowles

Brigadier Andrew Henry Parker Bowles OBE is a retired British Army officer. He is the former husband of the Duchess of Cornwall , who is now married to the Prince of Wales....

, was still living.

Edward and Wallis's romance captured the imagination and interest of multiple artists. Cultural depictions of the abdication and its aftermath

Cultural depictions of Edward VIII of the United Kingdom

There have been a number of depictions of King Edward VIII in popular culture, both biographical and fictional, following his abdication in 1936.-Literature:...

are extensive, and encompass a variety of media.

External links

- Pathé Newsreel recording of Edward's abdication speech (requires FlashAdobe FlashAdobe Flash is a multimedia platform used to add animation, video, and interactivity to web pages. Flash is frequently used for advertisements, games and flash animations for broadcast...

)