Elamite language

Encyclopedia

Extinct language

An extinct language is a language that no longer has any speakers., or that is no longer in current use. Extinct languages are sometimes contrasted with dead languages, which are still known and used in special contexts in written form, but not as ordinary spoken languages for everyday communication...

spoken by the ancient Elamites. Elamite was the primary language in present day Iran from 2800–550 BCE. The last written records in Elamite appear about the time of the conquest of the Persian Empire by Alexander the Great.

Elamite scripts

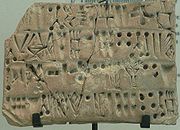

Over the centuries, three distinct Elamite scripts developed.- Proto-ElamiteProto-ElamiteThe Proto-Elamite period is the time of ca. 3200 BC to 2700 BC when Susa, the later capital of the Elamites, began to receive influence from the cultures of the Iranian plateau. In archaeological terms this corresponds to the late Banesh period...

is the oldest known writing system from Iran. It was used during a brief period of time (ca. 3100 – 2900 BC); clay tablets with Proto-Elamite writing have been found at different sites across Iran. The Proto-Elamite script is thought to have developed from early cuneiformCuneiformCuneiform can refer to:*Cuneiform script, an ancient writing system originating in Mesopotamia in the 4th millennium BC*Cuneiform , three bones in the human foot*Cuneiform Records, a music record label...

(proto-cuneiform). The Proto-Elamite script consists of more than 1,000 signs and is thought to be partly logographicLogogramA logogram, or logograph, is a grapheme which represents a word or a morpheme . This stands in contrast to phonograms, which represent phonemes or combinations of phonemes, and determinatives, which mark semantic categories.Logograms are often commonly known also as "ideograms"...

. Since it has not yet been deciphered, it is not known whether the language it represents is Elamite or another language. It has been suggested that some early writing systems, including Proto-Elamite, may not relate to spoken languages in the way that modern writing systems do.

- Linear ElamiteLinear ElamiteLinear Elamite is a Bronze Age writing system used in Elam, known from a few monumental inscriptions only. It was used contemporarily with Elamite Cuneiform and likely records the Elamite language....

is a writing system from Iran attested in a few monumental inscriptions only. It is often claimed that Linear Elamite is a syllabic writing system derived from Proto-Elamite, although this cannot be proven. Linear-Elamite was used for a very brief period of time during the last quarter of the third millennium BC. Linear-Elamite has not been deciphered. Several scholars have attempted to decipher linear-Elamite, most notably Walther Hinz and Piero Meriggi.

- The Elamite CuneiformElamite CuneiformElamite cuneiform was a logo-syllabic script used to write the Elamite Language.- History and Decipherment:The Elamite Language is the now extinct language spoken by Elamites, who inhabited the regions of Khuzistān and Fārs in Southern Iran...

script was used from about 2500 to 331 BC, and was adapted from the AkkadAkkadThe Akkadian Empire was an empire centered in the city of Akkad and its surrounding region in Mesopotamia....

ian Cuneiform. The Elamite Cuneiform script consisted of about 130 symbols, far fewer than most other cuneiform scripts.

Linguistic typology

Elamite was an agglutinative languageAgglutinative language

An agglutinative language is a language that uses agglutination extensively: most words are formed by joining morphemes together. This term was introduced by Wilhelm von Humboldt in 1836 to classify languages from a morphological point of view...

, and Elamite grammar

Grammar

In linguistics, grammar is the set of structural rules that govern the composition of clauses, phrases, and words in any given natural language. The term refers also to the study of such rules, and this field includes morphology, syntax, and phonology, often complemented by phonetics, semantics,...

was characterized by a well-developed and pervasive nominal class system, where animate nouns had separate markers for 1st, 2nd, and 3rd person – the latter being a rather unusual feature. It can be said to display a kind of Suffixaufnahme

Suffixaufnahme

Suffixaufnahme is a linguistic phenomenon used in forming a genitive construction, whereby prototypically a genitive noun agrees with its head noun...

in that the nominal class markers of the head were also attached to any modifiers, including adjectives, noun adjunct

Noun adjunct

In grammar, a noun adjunct or attributive noun or noun premodifier is a noun that modifies another noun and is optional — meaning that it can be removed without changing the grammar of the sentence; it is a noun functioning as an adjective. For example, in the phrase "chicken soup" the noun adjunct...

s, possessor nouns, and even entire clauses.

History

The history of Elamite is periodized as follows:- Old Elamite (c. 2600–1500 BC)

- Middle Elamite (c. 1500–1000 BC)

- Neo-Elamite (1000–550 BC)

- Achaemenid Elamite (550–330 BC)

Middle Elamite is considered the “classical” period of Elamite, whereas the best attested variety is Achaemenid Elamite, which was widely used by the Achaemenid Persian state for official inscriptions as well as administrative records and displays significant Old Persian influence. Documents from the Old Elamite and early Neo-Elamite stages are rather scarce. Neo-Elamite can be regarded as a transition between Middle and Achaemenid Elamite with respect to language structure.

Sound system

Because of the limitations of the scripts, Elamite phonology is not well understood. In terms of consonants, it had at least the stops /p/, /t/ and /k/, the sibilants /s/, /š/ and /z/ (with uncertain pronunciation), the nasals /m/ and /n/, the liquids /l/ and /r/, and a fricative /h/, which was lost in late Neo-Elamite. Some peculiarities of spelling have been interpreted as suggesting that there was a contrast between two series of stops (/p/, /t/, /k/ vs /b/, /d/, /g/), but in general such a distinction is not consistently indicated by written Elamite as we know it. As for the vowels, Elamite had at least /a/, /i/, and /u/, and may also have had an /e/, which is, however, not generally expressed unambiguously.Roots are generally of the forms CV, (C)VC, (C)VCV, and more rarely CVCCV (where the first C is usually a nasal).

Grammar

Elamite is agglutinative (but with fewer morphemes per word than, say, SumerianSumerian language

Sumerian is the language of ancient Sumer, which was spoken in southern Mesopotamia since at least the 4th millennium BC. During the 3rd millennium BC, there developed a very intimate cultural symbiosis between the Sumerians and the Akkadians, which included widespread bilingualism...

or Hurrian

Hurrian language

Hurrian is a conventional name for the language of the Hurrians , a people who entered northern Mesopotamia around 2300 BC and had mostly vanished by 1000 BC. Hurrian was the language of the Mitanni kingdom in northern Mesopotamia, and was likely spoken at least initially in Hurrian settlements in...

and Urartian

Urartian language

Urartian, Vannic, and Chaldean are conventional names for the language spoken by the inhabitants of the ancient kingdom of Urartu that was located in the region of Lake Van, with its capital near the site of the modern town of Van, in the Armenian Highland, modern-day Eastern Anatolia region of...

), and predominantly suffixing.

Nominal morphology

The Elamite nominal system is thoroughly pervaded by a noun class distinction which combines a gender distinction between animate and inanimate with a personal class distinction corresponding to the three persons of verbal inflection (first, second, third, plural).The suffixes are as follows:

Animate:

1st person singular: -k

2nd person singular: -t

3rd person singular: -r or Ø

3rd person plural: -p

Inanimate:

-Ø, -me, -n, -t

The animate 3rd person suffix -r can serve as a nominalizing suffix and indicate nomen agentis or just members of a class. The inanimate 3rd singular -me forms abstracts. Some examples are sunki-k “a king (1st person)” i.e. “I, a king”, sunki-r “a king (3rd person)”, nap-Ø or nap-ir “a god (3rd person)”, sunki-p “kings”, nap-ip “gods”, sunki-me “kingdom, kingship”, hal-Ø “town, land”, siya-n “temple”, hala-t “mud brick”.

Modifiers follow their (nominal) heads. In noun phrases and pronoun phrases, the suffixes referring to the head are appended to the modifier, regardless of whether the modifier is another noun (such as a possessor) or an adjective. Sometimes the suffix is preserved on the head as well.

Examples:

u šak X-k(i) = “I, the son of X”

X šak Y-r(i) = “X, the son of Y”

u sunki-k Hatamti-k = “I, the king of Elam”

sunki Hatamti-p (or, sometimes, sunki-p Hatamti-p) = “the kings of Elam”

temti riša-r = “great lord” (lit. “lord great”)

riša-r nap-ip-ir = “greatest of the gods” (lit. “great of the gods)

nap-ir u-ri = my god (lit. “god of me”)

hiya-n nap-ir u-ri-me = the throne hall of my god

takki-me puhu nika-me-me = “the life of our children”

sunki-p uri-p u-p(e) = ”kings, my predecessors” (lit. “kings, predecessors of me”)

This elegant system, in which the noun class suffixes function as derivational morphemes as well as agreement markers and indirectly as subordinating morphemes, is best seen in Middle Elamite. It is, to a great extent, broken down in Achaemenid Elamite, where possession and, sometimes, attributive relationships are uniformly expressed with the “genitive case

Genitive case

In grammar, genitive is the grammatical case that marks a noun as modifying another noun...

” suffix -na appended to the modifier: e.g. šak X-na “son of X”. The suffix -na, which probably originated from the inanimate agreement suffix -n followed by the nominalizing particle -a (see below), appeared already in Neo-Elamite.

The personal pronouns distinguish nominative and accusative case forms. They are as follows:

| Case | 1st sg. | 2nd sg. | 3rd sg. | 1st pl. | 2nd pl. | 3rd pl. | Inanimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | u | ni/nu | i/hi | nika/nuku | num/numi | ap/appi | i/in |

| Accusative | un | nun | ir/in | nukun | numun | appin | i/in |

In general, no special possessive pronouns are needed in view of the construction with the noun class suffixes. Nevertheless, surprisingly, a set of separate third-person animate possessives -e (sing.) / appi-e (plur.) is occasionally used already in Middle Elamite: puhu-e “her children”, hiš-api-e “their name”. The relative pronouns are akka “who” and appa “what, which”.

Verbal morphology

The verb base can be simple (e.g. ta- “put”) or “reduplicated” (e.g. beti > bepti “rebel”). The pure verb base can function as a verbal noun or “infinitive”.The verb distinguishes three forms functioning as finite verb

Finite verb

A finite verb is a verb that is inflected for person and for tense according to the rules and categories of the languages in which it occurs. Finite verbs can form independent clauses, which can stand on their own as complete sentences....

s, known as “conjugations”. Conjugation I is the only one that has special endings characteristic of finite verbs as such, as shown below. Its use is mostly associated with active voice, transitivity (or verbs of motion), neutral aspect and past tense meaning. Conjugations II and III can be regarded as periphrastic constructions with participles; they are formed by the addition of the nominal personal class suffixes to a passive perfective participle in -k and to an active imperfective participle in -n, respectively. Accordingly, Conjugation II expresses a perfective aspect, hence usually past tense, and an intransitive or passive voice, whereas Conjugation III expresses an imperfective non-past action.

The Middle Elamite Conjugation I is formed with the following suffixes:

1st singular: -h

2nd singular: -t

3rd singular: -š

1st plural: -hu

2nd plural: -h-t

2rd plural: -h-š

Examples: kulla-h ”I prayed”, hap-t ”you heard”, hutta-š “he did”, kulla-hu “we prayed”, hutta-h-t “you (plur.) did”, hutta-h-š “they did”.

In Achaemenid Elamite, the loss of the /h/ phoneme reduces the transparency of the Conjugation I endings and leads to the merger of the singular and plural except in the first person; in addition, the first person plural changes from -hu to -ut.

The participles can be exemplified as follows: perfective participle hutta-k “done”, kulla-k “something prayed”, i.e. “a prayer”; imperfective particple hutta-n “doing” or “who will do”, also serving as a non-past infinitive. The corresponding conjugation is, for the perfective, 1st person singular hutta-k-k, 2nd person singular hutta-k-t, 3rd person singular hutta-k-r, 3rd person plural hutta-k-p; and for the imperfective, 1st person singular hutta-n-k, 2nd person singular hutta-n-t, 3rd person singular hutta-n-r, 3rd person plural hutta-n-p.

In Achaemenid Elamite, the Conjugation 2 endings are somewhat changed: 1st person singular hutta-k-ut, 2nd person singular hutta-k-t, 3rd person singular hutta-k (hardly ever attested in predicative use), 3rd person plural hutta-p.

There is also a periphrastic construction with an auxiliary verb

Auxiliary verb

In linguistics, an auxiliary verb is a verb that gives further semantic or syntactic information about a main or full verb. In English, the extra meaning provided by an auxiliary verb alters the basic meaning of the main verb to make it have one or more of the following functions: passive voice,...

ma- following either Conjugation II and III stems (i.e. the perfective and imperfective participles), or nomina agentis in -r, or a verb base directly. In Achaemenid Elamite, only the third option exists. There is no consensus on the exact meaning of the periphrastic forms with ma-, although durative, intensive or volitional interpretations have been suggested.

Optative mood is expressed by the addition of the suffix -ni to Conjugations I and II. The imperative is identical to the second person of Conjugation I in Middle Elamite. In Achaemenid Elamite, it is the third person that coincides with the imperative. The prohibitative is formed by the particle ani/ani preceding Conjugation III.

Verbal forms can be converted into the heads of subordinate clauses through the addition of the suffix -a, much as in Sumerian

Sumerian language

Sumerian is the language of ancient Sumer, which was spoken in southern Mesopotamia since at least the 4th millennium BC. During the 3rd millennium BC, there developed a very intimate cultural symbiosis between the Sumerians and the Akkadians, which included widespread bilingualism...

: siyan in-me kuši-hš(i)-me-a “the temple which they did not build”. -ti/-ta can be suffixed to verbs, chiefly of conjugation I, expressing possibly a meaning of anteriority (perfect and pluperfect tense).

The negative particle is in-; it takes nominal class suffixes that agree with the subject of attention (which may or may not coincide with the grammatical subject), e.g. first person singular in-ki, third person singular animate in-ri, third person singular inanimate in-ni/in-me. In Achaemenid Elamite, the inanimate form in-ni has been generalized to all persons, so that concord has been lost.

Syntax

As already mentioned, nominal heads are normally followed by their modifiers, although there are occasional inversions of this word order. The word order is subject–object–verb (SOV), with indirect objects preceding direct objects, although the word order becomes more flexible in Achaemenid Elamite. There are often resumptive pronouns before the verb – often long sequences, especially in Middle Elamite (ap u in duni-h "to-them I it gave").The language uses postpositions such as -ma "in" and -na "of", but spatial and temporal relationships are generally expressed in Middle Elamite by means of "directional words" originating as nouns or verbs. These "directional words" either precede or follow the governed nouns, and tend to exhibit noun class agreement with whatever noun is described by the prepositional phrase: e.g. i-r pat-r u-r ta-t-ni "may you place him under me", lit. "him inferior of-me place-you-may". In Achaemenid Elamite, postpositions become more common and partly, but not entirely, displace this type of constructions.

A common conjunction is ak "and, or". Achaemenid Elamite also uses a number of subordinating conjunctions such as anka "if, when", sap "as, when", etc. Subordinate clauses usually precede the verb of the main clause. In Middle Elamite, the most common way to construct a relative clause is to attach a nominal class suffix to the clause-final verb, optionally followed by the relativizing suffix -a: thus, lika-me i-r hani-š-r(i) "whose reign he loves", or optionally lika-me i-r hani-š-r-a. The alternative construction by means of the relative pronouns akka "who" and appa "which" is uncommon in Middle Elamite, but gradually becomes dominant at the expense of the nominal class suffix construction in Achaemenid Elamite.

Language samples

Middle Elamite (Šutruk-Nahhunte I, 1200–1160 BC; EKI 18, IRS 33):Transliteration:

(1) ú DIŠšu-ut-ru-uk-d.nah-hu-un-te ša-ak DIŠhal-lu-du-uš-din-šu-ši-

(2) -na-ak-gi-ik su-un-ki-ik an-za-an šu-šu-un-ka4 e-ri-en-

(3) -tu4-um ti-pu-uh a-ak hi-ya-an din-šu-ši-na-ak na-pír

(4) ú-ri-me a-ha-an ha-li-ih-ma hu-ut-tak ha-li-ku-me

(5) din-šu-ši-na-ak na-pír ú-ri in li-na te-la-ak-ni

Transcription:

U Šutruk-Nahhunte, šak Halluduš-Inšušinak-ik, sunki-k Anzan Šušun-ka. Erientum tipu-h ak hiya-n Inšušinak nap-ir u-ri-me ahan hali-h-ma. hutta-k hali-k u-me Inšušinak nap-ir u-ri in lina tela-k-ni.

Translation:

I, Šutruk-Nahhunte, son of Halluduš-Inšušinak, king of Anshan

Anshan (Persia)

Anshan - History :Before 1973, when it was identified as Tall-i Malyan, Anshan had been assumed by scholars to be somewhere in the central Zagros mountain range....

and Susa

Susa

Susa was an ancient city of the Elamite, Persian and Parthian empires of Iran. It is located in the lower Zagros Mountains about east of the Tigris River, between the Karkheh and Dez Rivers....

. I moulded bricks and made the throne hall of my god Inšušinak with them. May my work come as an offering to my god Inšušinak.

Achaemenid Elamite (Xerxes I

Xerxes I of Persia

Xerxes I of Persia , Ḫšayāršā, ), also known as Xerxes the Great, was the fifth king of kings of the Achaemenid Empire.-Youth and rise to power:...

, 486-465 BC; XPa):

Transliteration:

(01) [sect 01] dna-ap ir-šá-ir-ra du-ra-mas-da ak-ka4 AŠmu-ru-un

(02) hi pè-iš-tá ak-ka4 dki-ik hu-ip-pè pè-iš-tá ak-ka4 DIŠ

(03) LÚ.MEŠ-ir-ra ir pè-iš-tá ak-ka4 ši-ia-ti-iš pè-iš-tá DIŠ

(04) LÚ.MEŠ-ra-na ak-ka4 DIŠik-še-ir-iš-šá DIŠEŠŠANA ir hu-ut-taš-

(05) tá ki-ir ir-še-ki-ip-in-na DIŠEŠŠANA ki-ir ir-še-ki-ip-

(06) in-na pír-ra-ma-ut-tá-ra-na-um

Transcription:

Nap irša-rra Uramasda, akka muru-n hi pe-š-ta, akka kik hupe pe-š-ta, akka ruh(?)-irra ir pe-š-ta, akka šiatiš pe-š-ta ruh(?)-ra-na, akka Ikšerša sunki(?) ir hutta-š-ta kir iršeki-pi-na sunki(?), kir iršeki-pi-na piramataram.

Translation:

A great god is Ahura Mazda

Ahura Mazda

Ahura Mazdā is the Avestan name for a divinity of the Old Iranian religion who was proclaimed the uncreated God by Zoroaster, the founder of Zoroastrianism...

, who created this earth, who created that sky, who created man, who created happiness of man, who made Xerxes

Xerxes I of Persia

Xerxes I of Persia , Ḫšayāršā, ), also known as Xerxes the Great, was the fifth king of kings of the Achaemenid Empire.-Youth and rise to power:...

king, one king of many, one lord of many.

Relations to other language families

Elamite is regarded as a language isolateLanguage isolate

A language isolate, in the absolute sense, is a natural language with no demonstrable genealogical relationship with other languages; that is, one that has not been demonstrated to descend from an ancestor common with any other language. They are in effect language families consisting of a single...

and has no close relation to the neighboring Semitic languages

Semitic languages

The Semitic languages are a group of related languages whose living representatives are spoken by more than 270 million people across much of the Middle East, North Africa and the Horn of Africa...

, to the Indo-European languages

Indo-European languages

The Indo-European languages are a family of several hundred related languages and dialects, including most major current languages of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and South Asia and also historically predominant in Anatolia...

, or to Sumerian

Sumerian language

Sumerian is the language of ancient Sumer, which was spoken in southern Mesopotamia since at least the 4th millennium BC. During the 3rd millennium BC, there developed a very intimate cultural symbiosis between the Sumerians and the Akkadians, which included widespread bilingualism...

, even though it adopted the Sumerian syllabic script. David McAlpin proposed an Elamo-Dravidian family with the Dravidian languages

Dravidian languages

The Dravidian language family includes approximately 85 genetically related languages, spoken by about 217 million people. They are mainly spoken in southern India and parts of eastern and central India as well as in northeastern Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, Afghanistan, Iran, and...

, Vaclav Blazek

Václav Blažek

Václav Blažek is a historical linguist. He is a professor at Masaryk University and also teaches at the University of West Bohemia ....

proposed a relation with Afroasiatic, and George Starostin published lexicostatistics

Lexicostatistics

Lexicostatistics is an approach to comparative linguistics that involves quantitative comparison of lexical cognates. Lexicostatistics is related to the comparative method but does not reconstruct a proto-language...

finding Elamite to be approximately equidistant from Nostratic and Afroasiatic but more distant from Sino-Caucasian.

External links

- Ancient Scripts: Elamite

- An overview of Elamite (in German) by Ernst Kausen

- Elamite grammar, glossary, and a very comprehensive text corpus (in Spanish), by Enrique Quintana (in some respects, the author's views deviate from those generally accepted in the field)

- Эламский язык, a detailed description (in Russian), by Igor DiakonovIgor DiakonovIgor Mikhailovich Diakonov was a Russian historian, linguist, and translator and a renowned expert in the Ancient Near East and its languages....

- Persepolis Fortification Archive (requires Java)

- Achaemenid Royal Inscriptions project (the project is discontinued, but the texts, the translations and the glossaries remain accessible on the Internet ArchiveInternet ArchiveThe Internet Archive is a non-profit digital library with the stated mission of "universal access to all knowledge". It offers permanent storage and access to collections of digitized materials, including websites, music, moving images, and nearly 3 million public domain books. The Internet Archive...

through the options "Corpus Catalogue" and "Browse Lexicon") - On the genetic affiliation of the Elamite language by George Starostin (the Nostratic theoryNostratic languagesNostratic is a proposed language family that includes many of the indigenous language families of Eurasia, including the Indo-European, Uralic and Altaic as well as Kartvelian languages...

; also with glossary) - http://www.kavehfarrokh.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/07/elamitedravidian.pdf by David McAlpin