Fenian Brotherhood

Encyclopedia

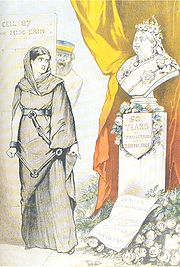

John O'Mahony

John O'Mahony may refer to:*John O'Mahony , founder of the Irish Republican Brotherhood *John O'Mahony , Irish Fine Gael politician representing Mayo and twice an All-Ireland winner managing the Galway Football Team*Sean Matgamna , also known as John O'Mahony, Trotskyist theorist*Seán O'Mahony ,...

and Michael Doheny

Michael Doheny

Michael Doheny was an Irish writer and member of the Young Ireland movement.-Early life:The third son of Michael Doheny, of Brookhill, he was born at Brookhill, near Fethard, Co. Tipperary, and married a Miss O'Dwyer of that county...

. It was a precursor to Clan na Gael

Clan na Gael

The Clan na Gael was an Irish republican organization in the United States in the late 19th and 20th centuries, successor to the Fenian Brotherhood and a sister organization to the Irish Republican Brotherhood...

, a sister organization to the Irish Republican Brotherhood

Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland during the second half of the 19th century and the start of the 20th century...

. Members were commonly known as "Fenians". O'Mahony, who was a Celt

Celt

The Celts were a diverse group of tribal societies in Iron Age and Roman-era Europe who spoke Celtic languages.The earliest archaeological culture commonly accepted as Celtic, or rather Proto-Celtic, was the central European Hallstatt culture , named for the rich grave finds in Hallstatt, Austria....

ic scholar, named his organization after the Fianna

Fianna

Fianna were small, semi-independent warrior bands in Irish mythology and Scottish mythology, most notably in the stories of the Fenian Cycle, where they are led by Fionn mac Cumhaill....

, the legendary band of Irish warriors led by Fionn mac Cumhaill

Fionn mac Cumhaill

Fionn mac Cumhaill , known in English as Finn McCool, was a mythical hunter-warrior of Irish mythology, occurring also in the mythologies of Scotland and the Isle of Man...

..

Background

The Fenian Brotherhood trace their origins back to 1798 and the United Irishmen, who had been an open political organization only to be suppressed and became a secret revolutionary organization, rose in rebellionIrish Rebellion of 1798

The Irish Rebellion of 1798 , also known as the United Irishmen Rebellion , was an uprising in 1798, lasting several months, against British rule in Ireland...

, seeking an end to British rule in Ireland and the establishment of an Irish Republic

Irish Republic

The Irish Republic was a revolutionary state that declared its independence from Great Britain in January 1919. It established a legislature , a government , a court system and a police force...

. The rebellion was suppressed, but the principles of the United Irishmen were to have a powerful influence on the course of Irish history.

Following the collapse of the rebellion, the British Prime Minister William Pitt

William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger was a British politician of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He became the youngest Prime Minister in 1783 at the age of 24 . He left office in 1801, but was Prime Minister again from 1804 until his death in 1806...

introduced a bill to abolish the Irish parliament and manufactured a Union

Act of Union 1800

The Acts of Union 1800 describe two complementary Acts, namely:* the Union with Ireland Act 1800 , an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain, and...

between Ireland and Britain. Opposition from the Protestant oligarchy that controlled the parliament was countered by the widespread and open use of bribery. The Act of Union

Act of Union 1800

The Acts of Union 1800 describe two complementary Acts, namely:* the Union with Ireland Act 1800 , an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain, and...

was passed, and became law on 1 January 1801. The Catholics, who had been excluded from the Irish parliament, were promised emancipation

Catholic Emancipation

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in Great Britain and Ireland in the late 18th century and early 19th century which involved reducing and removing many of the restrictions on Roman Catholics which had been introduced by the Act of Uniformity, the Test Acts and the penal laws...

under the Union. This promise was never kept, and caused a protracted and bitter struggle for civil liberties. It was not until 1829 that the British government reluctantly conceded Catholic emancipation

Catholic Emancipation

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in Great Britain and Ireland in the late 18th century and early 19th century which involved reducing and removing many of the restrictions on Roman Catholics which had been introduced by the Act of Uniformity, the Test Acts and the penal laws...

. Though leading to general emancipation, this process simultaneously disenfranchised the small tenants, known as ‘forty shilling freeholders’

Forty Shilling Freeholders

Forty shilling freeholders were a group of landowners who had the Parliamentary franchise to vote in county constituencies in various parts of the British Isles. In England it was the only such qualification from 1430 until 1832...

, who were mainly Catholics.

Daniel O’Connell, who had led the emancipation campaign, then attempted the same methods in his campaign, to have the Act of Union

Act of Union 1800

The Acts of Union 1800 describe two complementary Acts, namely:* the Union with Ireland Act 1800 , an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain, and...

with Britain repealed. Despite the use of petitions and public meetings which attracted vast popular support, the government thought the Union was more important than Irish public opinion.

Repeal Association

The Repeal Association was an Irish mass membership political movement set up by Daniel O'Connell to campaign for a repeal of the Act of Union of 1800 between Great Britain and Ireland....

, became impatient with O’Connell’s over-cautious policies, and began to question his intentions. Later they were what became to known as the Young Ireland

Young Ireland

Young Ireland was a political, cultural and social movement of the mid-19th century. It led changes in Irish nationalism, including an abortive rebellion known as the Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848. Many of the latter's leaders were tried for sedition and sentenced to penal transportation to...

movement. In 1842 three of the Young Ireland

Young Ireland

Young Ireland was a political, cultural and social movement of the mid-19th century. It led changes in Irish nationalism, including an abortive rebellion known as the Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848. Many of the latter's leaders were tried for sedition and sentenced to penal transportation to...

leaders, Thomas Davis

Thomas Osborne Davis (Irish politician)

Thomas Osborne Davis was a revolutionary Irish writer who was the chief organizer and poet of the Young Ireland movement.-Early life:...

, Charles Gavan Duffy

Charles Gavan Duffy

Additional Reading*, Allen & Unwin, 1973.*John Mitchel, A Cause Too Many, Aidan Hegarty, Camlane Press.*Thomas Davis, The Thinker and Teacher, Arthur Griffith, M.H. Gill & Son 1922....

and John Blake Dillon

John Blake Dillon

John Blake Dillon was an Irish writer and Politician who was one of the founding members of the Young Ireland movement....

, launched the Nation newspaper

The Nation (Irish newspaper)

The Nation was an Irish nationalist weekly newspaper, published in the 19th century. The Nation was printed first at 12 Trinity Street, Dublin, on 15 October 1842, until 6 January 1844...

. In the paper they set out to create a spirit of pride and an identity based on nationality rather than on social status or religion. Following the collapse of the Repeal Association

Repeal Association

The Repeal Association was an Irish mass membership political movement set up by Daniel O'Connell to campaign for a repeal of the Act of Union of 1800 between Great Britain and Ireland....

and with the arrival of famine, the Young Irelanders broke away completely from O’Connell in 1846.

The blight that destroyed the potato harvest between 1845 and 1849 was an unprecedented human tragedy. An entire social class of small farmers and labourers were to be virtually wiped out by hunger, disease and emigration. The laissez –faire economic thinking of the government ensured that help was slow, hesitant and insufficient. Between 1845 and 1851 the population fell by almost two million.

That the people starved while livestock and grain continued to be exported, quite often under military escort, would leave a legacy of bitterness and resentment among the survivors. The waves of emigration because of the famine and in the years following also ensured that such feelings would not be confined to Ireland, but spread to England, the United States, Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

and every country where Irish emigrants gathered.

Shocked by the scenes of starvation and greatly influenced by the revolutions then sweeping Europe, the Young Ireland

Young Ireland

Young Ireland was a political, cultural and social movement of the mid-19th century. It led changes in Irish nationalism, including an abortive rebellion known as the Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848. Many of the latter's leaders were tried for sedition and sentenced to penal transportation to...

ers moved from agitation to armed rebellion in 1848

Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848

The Young Irelander Rebellion was a failed Irish nationalist uprising led by the Young Ireland movement. It took place on 29 July 1848 in the village of Ballingarry, County Tipperary. After being chased by a force of Young Irelanders and their supporters, an Irish Constabulary unit raided a house...

. The attempted rebellion failed after a small skirmish in Ballingary, Co Tipperary

Tipperary

Tipperary is a town and a civil parish in South Tipperary in Ireland. Its population was 4,415 at the 2006 census. It is also an ecclesiastical parish in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Cashel and Emly, and is in the historical barony of Clanwilliam....

, coupled with a few minor incidents elsewhere. The reasons for the failure were obvious: the people were totally despondent after three years of famine, and being prompted to rise up early resulted in an inadequacy of military preparations, which caused disunity among the leaders.

The Government quickly rounded up many of the instigators. Those who could fled across the seas, and their followers dispersed. A last flicker of revolt in 1849, led by among others James Fintan Lalor

James Fintan Lalor

James Fintan Lalor was an Irish revolutionary, journalist, and “one of the most powerful writers of his day.” A leading member of the Irish Confederation , he was to play an active part in both the Rebellion in July 1848 and the attempted Rising in September of that same year...

, was equally unsuccessful.

John Mitchel

John Mitchel

John Mitchel was an Irish nationalist activist, solicitor and political journalist. Born in Camnish, near Dungiven, County Londonderry, Ireland he became a leading member of both Young Ireland and the Irish Confederation...

, the most committed advocate of revolution, had been arrested early in 1848 and transported to Australia on the purposefully created charge of Treason-felony

Treason Felony Act 1848

The Treason Felony Act 1848 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The Act is still in force. It is a law which protects HM the Queen and the Crown....

. He was to be joined by other leaders, such as William Smith O'Brien

William Smith O'Brien

William Smith O'Brien was an Irish Nationalist and Member of Parliament and leader of the Young Ireland movement. He was convicted of sedition for his part in the Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848, but his sentence of death was commuted to deportation to Van Diemen's Land. In 1854, he was...

and Thomas Francis Meagher

Thomas Francis Meagher

-Young Ireland:Meagher returned to Ireland in 1843, with undecided plans for a career in the Austrian army, a tradition among a number of Irish families. In 1844 he traveled to Dublin with the intention of studying for the bar. He became involved in the Repeal Association, which worked for repeal...

who had both been arrested after Ballingary. John Blake Dillon

John Blake Dillon

John Blake Dillon was an Irish writer and Politician who was one of the founding members of the Young Ireland movement....

escaped to France, as did three of the younger members, James Stephens

James Stephens (Irish nationalist)

James Stephens was an Irish Republican and the founding member of an originally unnamed revolutionary organisation in Dublin on 17 March 1858, later to become known as the Irish Republican Brotherhood , also referred to as the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood by contemporaries.-Early...

, John O'Mahony

John O'Mahony

John O'Mahony may refer to:*John O'Mahony , founder of the Irish Republican Brotherhood *John O'Mahony , Irish Fine Gael politician representing Mayo and twice an All-Ireland winner managing the Galway Football Team*Sean Matgamna , also known as John O'Mahony, Trotskyist theorist*Seán O'Mahony ,...

and Michael Doheny

Michael Doheny

Michael Doheny was an Irish writer and member of the Young Ireland movement.-Early life:The third son of Michael Doheny, of Brookhill, he was born at Brookhill, near Fethard, Co. Tipperary, and married a Miss O'Dwyer of that county...

.

Founding

After the collapse of the '48 rebellionYoung Irelander Rebellion of 1848

The Young Irelander Rebellion was a failed Irish nationalist uprising led by the Young Ireland movement. It took place on 29 July 1848 in the village of Ballingarry, County Tipperary. After being chased by a force of Young Irelanders and their supporters, an Irish Constabulary unit raided a house...

James Stephens

James Stephens (Irish nationalist)

James Stephens was an Irish Republican and the founding member of an originally unnamed revolutionary organisation in Dublin on 17 March 1858, later to become known as the Irish Republican Brotherhood , also referred to as the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood by contemporaries.-Early...

and John O'Mahony

John O'Mahony

John O'Mahony may refer to:*John O'Mahony , founder of the Irish Republican Brotherhood *John O'Mahony , Irish Fine Gael politician representing Mayo and twice an All-Ireland winner managing the Galway Football Team*Sean Matgamna , also known as John O'Mahony, Trotskyist theorist*Seán O'Mahony ,...

went to the Continent to avoid arrest. In Paris they supported themselves by teaching and translation work and planned the next stage of "the fight to overthrow British rule in Ireland." In 1856 O'Mahony went to America and founded the Fenian Brotherhood in 1858. Stephens returned to Ireland and in Dublin on St. Patrick's Day 1858, following an organizing tour through the length and breadth of the country, founded the Irish counterpart of the American Fenians, the Irish Republican Brotherhood.

Fenian raids into Canada

- See main article Fenian raidsFenian raidsBetween 1866 and 1871, the Fenian raids of the Fenian Brotherhood who were based in the United States; on British army forts, customs posts and other targets in Canada, were fought to bring pressure on Britain to withdraw from Ireland. They divided many Catholic Irish-Canadians, many of whom were...

In the United States, O'Mahony's presidency over the Fenian Brotherhood was being increasingly challenged by William R. Roberts

William R. Roberts

William Randall Roberts was a diplomat, Fenian Society member, and United States Representative from New York . Born in County Cork, Ireland, he immigrated to the United States in July 1849, received a limited schooling, and was a merchant in New York City until 1869, until he retired.In 1865,...

. Both Fenian factions raised money by the issue of bonds in the name of the "Irish Republic," which were bought by the faithful in the expectation of their being honored when Ireland should be "a nation once again

A Nation Once Again

"A Nation Once Again" is a song, written in the early to mid-1840s by Thomas Osborne Davis . Davis was a founder of an Irish movement whose aim was the independence of Ireland....

". These bonds were to be redeemed "six months after the recognition of the independence of Ireland." Hundreds of thousands of Irish immigrants subscribed.

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

, which the United States government took no major steps to prevent. Many in the U.S. administration were not indisposed to the movement because of Britain's failure to support the Union during the civil war. Roberts' "Secretary for War" was General T. W. Sweeny

Thomas William Sweeny

Thomas William Sweeny was an Irish soldier who served in the Mexican-American War and then was a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War.-Birth and early years:...

, who was struck off the American army list from January 1866 to November 1866 to allow him to organize the raids. The purpose of these raids was to seize the transportation network of Canada, with the idea that this would force the British to exchange Ireland's freedom for possession of their Province of Canada. Before the invasion, the Fenians had received some intelligence from like-minded supporters within Canada but did not receive support from all Irish Catholics there who saw the invasions as threatening the emerging Canadian sovereignty.

The command of the expedition in Buffalo, New York

Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second most populous city in the state of New York, after New York City. Located in Western New York on the eastern shores of Lake Erie and at the head of the Niagara River across from Fort Erie, Ontario, Buffalo is the seat of Erie County and the principal city of the...

, was entrusted by Roberts to Colonel John O'Neill

John O'Neill (Fenian)

General John O'Neill was a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood .He was born in Ireland, moved to the US, and served in the Union Army in the Civil War....

, who crossed the Niagara River

Niagara River

The Niagara River flows north from Lake Erie to Lake Ontario. It forms part of the border between the Province of Ontario in Canada and New York State in the United States. There are differing theories as to the origin of the name of the river...

(the Niagara is the international border) at the head of at least 800 (O'Neill's figure; usually reported as up to 1,500 in Canadian sources) men on the night and morning of 31 May/1 June 1866, and briefly captured Fort Erie

Fort Erie

Fort Erie was the first British fort to be constructed as part of a network developed after the Seven Years' War was concluded by the Treaty of Paris at which time all of New France had been ceded to Great Britain...

, defeating a Canadian force at Ridgeway

Battle of Ridgeway

The Battle of Ridgeway was fought in the vicinity of the town of Fort Erie across the Niagara River from Buffalo, NY near the village of Ridgeway, Canada West, currently Ontario, Canada on June 2, 1866, between Canadian troops and an irregular army of Irish-American invaders, the Fenians...

. Many of these men, including O'Neill, were battle-hardened veterans of the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

. In the end the invasion had been broken by the US authorities’ subsequent interruption of Fenian supply lines across the Niagara River and the arrests of Fenian reinforcements attempting to cross the river into Canada. It is unlikely that with such a small force that they would have ever achieved their goal.

Other Fenian attempts to invade occurred throughout the next week in the St. Lawrence Valley. As many of the weapons had in the meantime been confiscated by the US army, relatively few of these men actually became involved in the fighting. There even was a small Fenian raid on a storage building that successfully got back some weapons that had been seized by the US Army. Many were eventually returned anyway by sympathetic officers.

To get the Fenians out of the area, both in the St. Lawrence and Buffalo, the US government purchased rail tickets for the Fenians to return to their homes if the individuals involved would promise not to invade any more countries from the United States. Many of the arms were returned later if the person claiming them could post bond that they were not going to be used to invade Canada again, although some were possibly used in the raids that followed.

In December 1867, O'Neill became president of the Roberts faction of the Fenian Brotherhood, which in the following year held a great convention in Philadelphia attended by over 400 properly accredited delegates, while 6,000 Fenian soldiers, armed and in uniform, paraded the streets. At this convention a second invasion of Canada was determined upon; while the news of the Clerkenwell explosion was a strong incentive to a vigorous policy. Henri Le Caron

Thomas Miller Beach

Thomas Miller Beach was an English spy.His services enabled the British Government to take measures which led to the fiasco of the Canadian invasion of 1870 and Kiel's surrender in 1871, and he supplied full details concerning the various Irish-American associations, in which he himself was a...

, who, while acting as a secret agent of the British government, held the position of "Inspector-General of the Irish Republican Army," asserts that he distributed fifteen thousand stands of arms and almost three million rounds of ammunition in the care of the many trusted men stationed between Ogdensburg, New York

Ogdensburg, New York

Ogdensburg is a city in St. Lawrence County, New York, United States. The population was 11,128 at the 2010 census. In the late 18th century, European-American settlers named the community after American land owner and developer Samuel Ogden....

and St. Albans, Vermont

St. Albans (town), Vermont

St. Albans is a town in Franklin County, Vermont. The population was 6,392 at the 2010 census. The town completely surrounds the city of St. Albans, which was separated from the town and incorporated in 1902. References to "St. Albans" prior to this date generally refer to the town center, which...

, in preparation for the intended raid. It took place in April 1870, and proved a failure just as rapid and complete as the attempt of 1866. The Fenians under O'Neill's command crossed the Canadian frontier near Franklin, Vermont

Franklin, Vermont

Franklin is a town in Franklin County, Vermont, United States. The population was 1,268 at the 2000 census.The original name was Huntsburgh but the name was changed to Franklin in 1817.-Geography:...

, but were dispersed by a single volley from Canadian volunteers; while O'Neill himself was promptly arrested by the United States authorities acting under the orders of President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant was the 18th President of the United States as well as military commander during the Civil War and post-war Reconstruction periods. Under Grant's command, the Union Army defeated the Confederate military and ended the Confederate States of America...

. Yet another attempt and failure would take place in 1871 near the Red River in Manitoba

Manitoba

Manitoba is a Canadian prairie province with an area of . The province has over 110,000 lakes and has a largely continental climate because of its flat topography. Agriculture, mostly concentrated in the fertile southern and western parts of the province, is vital to the province's economy; other...

.

The Fenian threat prompted calls for Canadian confederation

Canadian Confederation

Canadian Confederation was the process by which the federal Dominion of Canada was formed on July 1, 1867. On that day, three British colonies were formed into four Canadian provinces...

. Confederation had been in the works for years but was only implemented in 1867, the year following the first raids. In 1868, a Fenian sympathizer assassinated Irish-Canadian politician Thomas D'Arcy McGee in Ottawa

Ottawa

Ottawa is the capital of Canada, the second largest city in the Province of Ontario, and the fourth largest city in the country. The city is located on the south bank of the Ottawa River in the eastern portion of Southern Ontario...

for his condemnation of the raids.

Fear of Fenian attack plagued the Lower Mainland

Lower Mainland

The Lower Mainland is a name commonly applied to the region surrounding and including Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. As of 2007, 2,524,113 people live in the region; sixteen of the province's thirty most populous municipalities are located there.While the term Lower Mainland has been...

of British Columbia

British Columbia

British Columbia is the westernmost of Canada's provinces and is known for its natural beauty, as reflected in its Latin motto, Splendor sine occasu . Its name was chosen by Queen Victoria in 1858...

during the 1880s, as the Fenian Brotherhood was actively organizing in Washington and Oregon

Oregon

Oregon is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is located on the Pacific coast, with Washington to the north, California to the south, Nevada on the southeast and Idaho to the east. The Columbia and Snake rivers delineate much of Oregon's northern and eastern...

, but raids never actually materialized . At the inauguration of the mainline of the Canadian Pacific Railway

Canadian Pacific Railway

The Canadian Pacific Railway , formerly also known as CP Rail between 1968 and 1996, is a historic Canadian Class I railway founded in 1881 and now operated by Canadian Pacific Railway Limited, which began operations as legal owner in a corporate restructuring in 2001...

in 1885, photos taken of the occasion show three large British warships sat in the harbor just off the railhead and its docks. Their presence was explicitly because of the threat of Fenian attack or terrorism, as were the large numbers of troops on the first train.

1867 and after

- See main article Fenian RisingFenian RisingThe Fenian Rising of 1867 was a rebellion against British rule in Ireland, organised by the Irish Republican Brotherhood .After the suppression of the Irish People newspaper, disaffection among Irish radical nationalists had continued to smoulder, and during the later part of 1866 IRB leader James...

During the latter part of 1866 Stephens endeavored to raise funds in America for a fresh rising planned for the following year. He issued a bombastic proclamation in America announcing an imminent general rising in Ireland; but he was himself soon afterwards deposed by his confederates, among whom dissension had broken out.

The Fenian Rising proved to be a "doomed rebellion," poorly organized and with minimal public support. Most of the Irish-American officers who landed at Cork

Cork (city)

Cork is the second largest city in the Republic of Ireland and the island of Ireland's third most populous city. It is the principal city and administrative centre of County Cork and the largest city in the province of Munster. Cork has a population of 119,418, while the addition of the suburban...

, in the expectation of commanding an army against England, were imprisoned; sporadic disturbances around the country were easily suppressed by the police, army

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

and local militias.

After the 1867 rising, IRB headquarters in Manchester opted to support neither of the dueling American factions, promoting instead a new organization in America, Clan na Gael

Clan na Gael

The Clan na Gael was an Irish republican organization in the United States in the late 19th and 20th centuries, successor to the Fenian Brotherhood and a sister organization to the Irish Republican Brotherhood...

. The Fenian Brotherhood itself, however, continued to exist until voting to disband in 1880.

In 1881, the submarine

Submarine

A submarine is a watercraft capable of independent operation below the surface of the water. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability...

Fenian Ram

Fenian Ram

Fenian Ram is a submarine designed by John Philip Holland for use by the Fenian Brotherhood, American counterpart to the Irish Republican Brotherhood, against the British...

, designed by John Philip Holland

John Philip Holland

John Philip Holland was an Irish engineer who developed the first submarine to be formally commissioned by the U.S...

for use against the British, was launched by the Delamater Iron Company in New York

New York

New York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

.

Sources

- The IRB: The Irish Republican Brotherhood from The Land League to Sinn Féin, Owen McGee, Four Courts Press, 2005, ISBN 1-85182-972-5

- Fenian Fever: An Anglo-American Delemma, Leon Ó Broin, Chatto & Windus, London, 1971, ISBN 0-7011-1749-4.

- The McGarrity Papers, Sean Cronin, Anvil Books, Ireland, 1972

- Fenian Memories, Dr. Mark F. Ryan, Edited by T.F. O'Sullivan, M. H. Gill & Son, LTD, Dublin, 1945

- The Fenians, Michael Kenny, The National Museum of Ireland in association with Country House, Dublin, 1994, ISBN 0-946172-42-0

See also

- FenianFenianThe Fenians , both the Fenian Brotherhood and Irish Republican Brotherhood , were fraternal organisations dedicated to the establishment of an independent Irish Republic in the 19th and early 20th century. The name "Fenians" was first applied by John O'Mahony to the members of the Irish republican...

- Hunter Patriots

- Catalpa RescueCatalpa rescueThe Catalpa rescue was the escape, in 1876, of six Irish Fenian prisoners from what was then the British penal colony of Western Australia.-Fenians and plans to escape:...

- John Boyle O'ReillyJohn Boyle O'ReillyJohn Boyle O'Reilly was an Irish-born poet, journalist and fiction writer. As a youth in Ireland, he was a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, or Fenians, for which he was transported to Western Australia...

External links

- Fenians.org

- Fenian Brotherhood Collection

- Fenian Brotherhood Collection at the American Catholic Historical Society, digitized by Villanova University's Digital Library

- "Torn Between Brothers: A Look at the Internal Divisions that Weakened the Fenian Brotherhood" - Jean Turner for Villanova University's Digital Library