First Persian invasion of Greece

Encyclopedia

The first Persian

invasion of Greece

, during the Persian Wars, began in 492 BCE, and ended with the decisive Athenian victory at the Battle of Marathon

in 490 BCE. The invasion, consisting of two distinct campaigns, was ordered by the Persian king Darius I primarily in order to punish the city-states of Athens

and Eretria

. These cities had supported the cities of Ionia

during their revolt

against Persian rule, thus incurring the wrath of Darius. Darius also saw the opportunity to extend his empire into Europe, and to secure its western frontier.

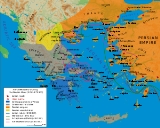

The first campaign in 492 BCE, led by Mardonius

, re-subjugated Thrace

and forced Macedon

to become a client kingdom of Persia. However, further progress was prevented when Mardonius's fleet was wrecked in a storm off the coast of Mount Athos

. The following year, having demonstrated his intentions, Darius sent ambassadors to all parts of Greece, demanding their submission. He received it from almost all of them, excepting Athens and Sparta

, both of whom executed the ambassadors. With Athens still defiant, and Sparta now effectively at war with him, Darius ordered a further military campaign for the following year.

The second campaign, in 490 BCE, was under the command of Datis

and Artaphernes

. The expedition headed first to the island Naxos, which it captured and burnt. It then island-hopped between the rest of the Cycladic Islands

, annexing each into the Persian empire. Reaching Greece, the expedition landed at Eretria, which it besieged, and after a brief time, captured. Eretria was razed and its citizens enslaved. Finally, the task force headed to Attica

, landing at Marathon

, en route for Athens. There, it was met by a smaller Athenian army, which nevertheless proceeded to win a remarkable victory at the Battle of Marathon

.

This defeat prevented the successful conclusion of the campaign, and the task force returned to Asia. Nevertheless, the expedition had fulfilled most of its aims, punishing Naxos and Eretria, and bringing much of the Aegean under Persian rule. The unfinished business from this campaign led Darius to prepare for a much larger invasion of Greece, to firmly subjugate it, and to punish Athens and Sparta. However, internal strife within the empire delayed this expedition, and Darius then died of old age. It was thus left to his son Xerxes I to lead the second Persian invasion of Greece

, beginning in 480 BCE

. Herodotus, who has been called the 'Father of History', was born in 484 BCE in Halicarnassus, Asia Minor (then under Persian overlordship). He wrote his 'Enquiries' (Greek—Historia; English—(The) Histories

) around 440–430 BCE, trying to trace the origins of the Greco-Persian Wars, which would still have been relatively recent history (the wars finally ending in 450 BCE). Herodotus's approach was entirely novel, and at least in Western society, he does seem to have invented 'history' as we know it. As Holland has it: "For the first time, a chronicler set himself to trace the origins of a conflict not to a past so remote so as to be utterly fabulous, nor to the whims and wishes of some god, nor to a people's claim to manifest destiny, but rather explanations he could verify personally."

Some subsequent ancient historians, despite following in his footsteps, criticised Herodotus, starting with Thucydides

. Nevertheless, Thucydides chose to begin his history where Herodotus left off (at the Siege of Sestos), and therefore evidently felt that Herodotus's history was accurate enough not to need re-writing or correcting. Plutarch

criticised Herodotus in his essay "On The Malignity of Herodotus", describing Herodotus as "Philobarbaros" (barbarian-lover), for not being pro-Greek enough, which suggests that Herodotus might actually have done a reasonable job of being even-handed. A negative view of Herodotus was passed on to Renaissance Europe, though he remained well read. However, since the 19th century his reputation has been dramatically rehabilitated by archaeological finds which have repeatedly confirmed his version of events. The prevailing modern view is that Herodotus generally did a remarkable job in his Historia, but that some of his specific details (particularly troop numbers and dates) should be viewed with skepticism. Nevertheless, there are still some historians who believe Herodotus made up much of his story.

The Sicilian historian Diodorus Siculus

, writing in the 1st century BCE in his Bibliotheca Historica

, also provides an account of the Greco-Persian wars, partially derived from the earlier Greek historian Ephorus

. This account is fairly consistent with Herodotus's. The Greco-Persian wars are also described in less detail by a number of other ancient historians including Plutarch, Ctesias of Cnidus, and are alluded by other authors, such as the playwright Aeschylus

. Archaeological evidence, such as the Serpent Column

, also supports some of Herodotus's specific claims.

, the earliest phase of the Greco-Persian Wars

. However, it was also the result of the longer-term interaction between the Greeks and Persians. In 500 BCE the Persian Empire was still relatively young and highly expansionistic, but prone to revolts amongst its subject peoples. Moreover, the Persian king Darius was a usurper, and had spent considerable time extinguishing revolts against his rule. Even before the Ionian Revolt, Darius had begun to expand the Empire into Europe, subjugating Thrace

, and forcing Macedon to become allied to Persia. Attempts at further expansion into the politically fractious world of Ancient Greece may have been inevitable. However, the Ionian Revolt had directly threatened the integrity of the Persian empire, and the states of mainland Greece remained a potential menace to its future stability. Darius thus resolved to subjugate and pacify Greece and the Aegean, and to punish those involved in the Ionian Revolt.

The Ionian revolt had begun with an unsuccessful expedition against Naxos

, a joint venture between the Persian satrap Artaphernes

and the Miletus

tyrant Aristagoras

. In the aftermath, Artaphernes decided to remove Aristagoras from power, but before he could do so, Aristagoras abdicated, and declared Miletus a democracy. The other Ionia

n cities, ripe for rebellion, followed suit, ejecting their Persian-appointed tyrants, and declaring themselves democracies. Artistagoras then appealed to the states of Mainland Greece for support, but only Athens

and Eretria

offered to send troops.

The involvement of Athens in the Ionian Revolt arose from a complex set of circumstances, beginning with the establishment of the Athenian Democracy

in the late 6th century BCE

In 510 BCE, with the aid of Cleomenes I

, King of Sparta

, the Athenian people had expelled Hippias, the tyrant

ruler of Athens. With Hippias's father Peisistratus

, the family had ruled for 36 out of the previous 50 years and fully intended to continue Hippias's rule. Hippias fled to Sardis

to the court of the Persian satrap

, Artaphernes

and promised control of Athens to the Persians if they were to help restore him. In the meantime, Cleomenes helped install a pro-Spartan tyranny under Isagoras

in Athens, in opposition to Cleisthenes

, the leader of the traditionally powerful Alcmaeonidae

family, who considered themselves the natural heirs to the rule of Athens. In a daring response, Cleisthenes proposed to the Athenian people that he would establish a 'democracy

' in Athens, much to the horror of the rest of the aristocracy. Cleisthenes's reasons for suggesting such a radical course of action, which would remove much of his own family's power, are unclear; perhaps he perceived that days of aristocratic rule were coming to an end anyway; certainly he wished to prevent Athens becoming a puppet of Sparta by whatever means necessary. However, as a result of this proposal, Cleisthenes and his family were exiled from Athens, in addition to other dissenting elements, by Isagoras. Having been promised democracy however, the Athenian people seized the moment and revolted, expelling Cleomenes and Isagoras. Cleisthenes was thus restored to Athens (507 BCE), and at breakneck speed began to establish democratic government. The establishment of democracy revolutionised Athens, which henceforth became one of the leading cities in Greece. The new found freedom and self-governance of the Athenians meant that they were thereafter exceptionally hostile to the return of the tyranny of Hippias, or any form of outside subjugation; by Sparta, Persia or anyone else.

Cleomenes, unsurprisingly, was not pleased with events, and marched on Athens with the Spartan army. Cleomenes's attempts to restore Isagoras to Athens ended in a debacle, but fearing the worst, the Athenians had by this point already sent an embassy to Artaphernes in Sardis, to request aid from the Persian Empire. Artaphernes requested that the Athenians give him a 'earth and water', a traditional token of submission, which the Athenian ambassadors acquiesced to. However, they were severely censured for this when they returned to Athens. At some point later Cleomenes instigated a plot to restore Hippias to the rule of Athens. This failed and Hippias again fled to Sardis and tried to persuade the Persians to subjugate Athens. The Athenians dispatched ambassadors to Artaphernes to dissuade him from taking action, but Artaphernes merely instructed the Athenians to take Hippias back as tyrant. Needless to say, the Athenians balked at this, and resolved instead to be openly at war with Persia. Having thus become the enemy of Persia, Athens was already in a position to support the Ionian cities when they began their revolt. The fact that the Ionian democracies were inspired by the example of Athens no doubt further persuaded the Athenians to support the Ionian Revolt; especially since the cities of Ionia were (supposedly) originally Athenian colonies.

Cleomenes, unsurprisingly, was not pleased with events, and marched on Athens with the Spartan army. Cleomenes's attempts to restore Isagoras to Athens ended in a debacle, but fearing the worst, the Athenians had by this point already sent an embassy to Artaphernes in Sardis, to request aid from the Persian Empire. Artaphernes requested that the Athenians give him a 'earth and water', a traditional token of submission, which the Athenian ambassadors acquiesced to. However, they were severely censured for this when they returned to Athens. At some point later Cleomenes instigated a plot to restore Hippias to the rule of Athens. This failed and Hippias again fled to Sardis and tried to persuade the Persians to subjugate Athens. The Athenians dispatched ambassadors to Artaphernes to dissuade him from taking action, but Artaphernes merely instructed the Athenians to take Hippias back as tyrant. Needless to say, the Athenians balked at this, and resolved instead to be openly at war with Persia. Having thus become the enemy of Persia, Athens was already in a position to support the Ionian cities when they began their revolt. The fact that the Ionian democracies were inspired by the example of Athens no doubt further persuaded the Athenians to support the Ionian Revolt; especially since the cities of Ionia were (supposedly) originally Athenian colonies.

The city of Eretria also sent assistance to the Ionians for reasons that are not completely clear. Possibly commercial reasons were a factor; Eretria was a mercantile city, whose trade was threatened by Persian dominance of the Aegean. Herodotus suggests that the Eretrians supported the revolt in order to repay the support the Milesians

had given Eretria in a past war against Chalcis

.

The Athenians and Eretrians sent a task force of 25 triremes to Asia Minor. Whilst there, the Greek army surprised and outmaneuvered Artaphernes, marching to Sardis and there burning the lower city. However, this was as much as the Greeks achieved, and they were then pursued back to the coast by Persian horsemen, losing many men in the process. Despite the fact their actions were ultimately fruitless, the Eretrians and in particular the Athenians had earned Darius's lasting enmity, and he vowed to punish both cities. The Persian naval victory at the Battle of Lade

(494 BCE) all but ended the Ionian Revolt, and by 493 BCE, the last hold-outs were vanquished by the Persian fleet. The revolt was used as an opportunity by Darius to extend the empire's border to the islands of the East Aegean and the Propontis, which had not been part of the Persian dominions before. The completion of the pacification of Ionia allowed the Persians to begin planning their next moves; to extinguish the threat to the empire from Greece, and to punish Athens and Eretria.

In the spring of 492 BCE an expeditionary force, to be commanded by Darius's son-in-law Mardonius was assembled, consisting of a fleet and a land army. Whilst the ultimate aim was to punish Athens and Eretria, the expedition also aimed to subdue as many of the Greek cities as possible. Departing from Cilicia, Mardonius sent the army to march to the Hellespont, whilst he travelled with the fleet. He sailed round the coast of Asia Minor to Ionia, where he spent a short time abolishing the tyrannies that ruled the cities of Ionia. Ironically, since the establishment of democracies had been a key factor in the Ionian Revolt, he replaced the tyrannies with democracies.

In the spring of 492 BCE an expeditionary force, to be commanded by Darius's son-in-law Mardonius was assembled, consisting of a fleet and a land army. Whilst the ultimate aim was to punish Athens and Eretria, the expedition also aimed to subdue as many of the Greek cities as possible. Departing from Cilicia, Mardonius sent the army to march to the Hellespont, whilst he travelled with the fleet. He sailed round the coast of Asia Minor to Ionia, where he spent a short time abolishing the tyrannies that ruled the cities of Ionia. Ironically, since the establishment of democracies had been a key factor in the Ionian Revolt, he replaced the tyrannies with democracies.

From thence the fleet continued on to the Hellespont, and when all was ready, shipped the land forces across to Europe. The army then marched through Thrace, re-subjugating it, since these lands had already been added to the Persian empire in 512 BCE, during Darius's campaign against the Scythia

ns. Upon reaching Macedon, the Persians forced the Macedonians to become a client kingdom of the Persians; before they had been allied to, but independent of the Persians.

Meanwhile, the fleet crossed to Thassos, resulting in the Thasians submitting to the Persians. The fleet then rounded the coastline as far as Acanthus

in Chalcidice

, before attempting to round the headland of Mount Athos

. However, they were caught in a violent storm, which drove them against the coastline of Athos, wrecking (according to Herodotus) 300 ships, with the loss of 20,000 men.

Then, whilst the army was camped in Macedon, the Brygians, a local Thracian tribe, launched a night raid against the Persian camp, killing many of the Persians, and wounding Mardonius. Despite his injury, Mardonius made sure that the Brygians were defeated and subjugated, before leading his army back to the Hellespont; the remnants of the navy also retreated to Asia. Although this campaign ended ingloriously, the land approaches to Greece had been secured, and the Greeks had no doubt been made aware of Darius's intentions for them.

However, Sparta was then thrown into disarray by internal machinations. The citizens of Aegina

had submitted to the Persian ambassadors, and the Athenians, troubled by the possibility of Persia using Aegina as a naval base, asked Sparta to intervene. Cleomenes travelled to Aegina to confront the Aeginetans personally, but they appealed to Cleomenes's fellow king Demaratus

, who supported their stance. Cleomenes responded by having Demaratus declared illegitimate, with the help of the priests at Delphi

(whom he bribed); Demaratus was replaced by his cousin Leotychides. Now faced with two Spartan kings, the Aeginetans capitulated, and handed over hostages to the Athenians as a guarantee of their good behaviour. However, in Sparta news emerged of the bribes Cleomenes had given at Delphi, and he was expelled from the city. He then sought to rally the northern Peloponnesus to his cause, at which the Spartans relented, and invited him back to the city. By 491 BCE though, Cleomenes was widely considered insane and was sentenced to prison where he was found dead the following day. Cleomenes was succeeded by his half-brother Leonidas I

.

, and marched into Cilicia

, where a fleet had been gathered. Command of the expedition was given to Datis

the Mede and Artaphernes

, son of the satrap Artaphernes

.

s. There is no indication in the historical sources of how many transport ships accompanied them, if any. Herodotus claimed that 3,000 transport ships accompanied 1,207 triremes during Xerxes

's invasion

in 480 BCE. Amongst modern historians, some have accepted this number of ships as reasonable; it has been suggested either that the number 600 represents the combined number of triremes and transport ships, or that there were horse transports in addition to 600 triremes.

Herodotus does not estimate the size of the Persian army, only saying that they formed a "large infantry that was well packed". Among other ancient sources, the poet Simonides

, a near-contemporary, says the campaign force numbered 200,000, while a later writer, the Roman Cornelius Nepos

estimates 200,000 infantry and 10,000 cavalry. Plutarch

and Pausanias

both independently give 300,000, as does the Suda

dictionary; Plato

and Lysias

assert 500,000; and Justin 600,000.

Modern historians generally dismiss these numbers as exaggerations. One approach to estimate the number of troops is to calculate the number of marines carried by 600 triremes. Herodotus tells us that each trireme in the second invasion of Greece carried 30 extra marines, in addition to a probable 14 standard marines. Thus, 600 triremes could easily have carried 18,000–26,000 infantry. Numbers proposed for the Persian infantry are in the range 18,000–100,000. However, the consensus is probably somewhere in the range of 25,000.

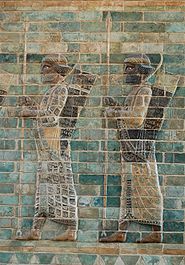

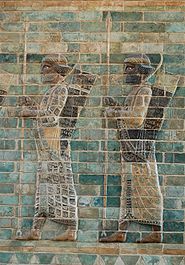

The Persian infantry used in the invasion was probably a heterogeneous group drawn from across the empire. However, according to Herodotus, there was at least a general conformity in the type of armour and style of fighting. The troops were, generally speaking, armed with a bow, 'short spear' and sword, carried a wicker shield, and wore at most a leather jerkin. The one exception to this may have been the ethnic Persian troops, who may have worn a corslet of scaled armour. Some of contingents would have been armed somewhat differently; for instance, the Saka

were renowned axemen. The 'elite' contingents of the Persian infantry seem to have been the ethnic Persians, Medians

, Cissians and the Saka; Herodotus specifically mentions the presence of Persians and Saka at Marathon. The style of fighting used by the Persians was probably to stand off from an enemy, using their bows (or equivalent) to wear down the enemy before closing in to deliver the coup de grace with spear and sword.

Estimates for the cavalry are usually in the 1,000–3,000 range. The Persian cavalry was usually provided by the ethnic Persians, Bactria

ns, Medes, Cissians and Saka; most of these probably fought as lightly armed missile cavalry. The fleet must have had at least some proportion of transport ships, since the cavalry was carried by ship; whilst Herodotus claims the cavalry was carried in the triremes, this is improbable. Lazenby estimates 30–40 transport ships would be required to carry 1,000 cavalry.

. A Lindian Temple Chronicle records that Datis

besieged the city of Lindos

, but was unsuccessful.

, before abruptly turning west into the Aegean Sea. The fleet sailed next to Naxos, in order to punish the Naxians for their resistance to the failed expedition that the Persians had mounted there a decade earlier. Many of the inhabitants fled to the mountains; those that the Persians caught were enslaved. The Persians then burnt the city and temples of the Naxians.

Moving on, the Persian fleet approached Delos

Moving on, the Persian fleet approached Delos

, whereupon the Delians also fled from their homes. Having demonstrated Persian power at Naxos, Datis now intended to show clemency to the other islands, if they submitted to him. He sent a herald to the Delians, proclaiming:

on Delos, to show his respect for one of the gods of the island. The fleet then proceeded to island-hop across the rest of Aegean on its way to Eretria, taking hostages and troops from each island.

. The citizens of Karystos refused to give hostages to the Persians, so they were besieged, and their land ravaged, until they submitted to the Persians.

The Persian fleet next headed south down the coast of Attica, landing at the bay of Marathon, roughly 25 miles (40.2 km) from Athens, on the advice of Hippias, son of the former tyrant of Athens Peisistratus. The Athenians, joined by a small force from Plataea

The Persian fleet next headed south down the coast of Attica, landing at the bay of Marathon, roughly 25 miles (40.2 km) from Athens, on the advice of Hippias, son of the former tyrant of Athens Peisistratus. The Athenians, joined by a small force from Plataea

, marched to Marathon, and succeeded in blocking the two exits from the plain of Marathon. At the same time, Athens' greatest runner, Pheidippides

(or Philippides) was sent to Sparta to request that the Spartan army march to Athens' aid. Pheidippides arrived during the festival of Carneia, a sacrosanct period of peace, and was informed that the Spartan army could not march to war until the full moon rose; Athens could not expect reinforcement for at least ten days. They decided to hold out at Marathon for the time being, and they were reinforced by a contingent of hoplites from Plataea.

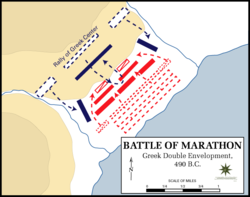

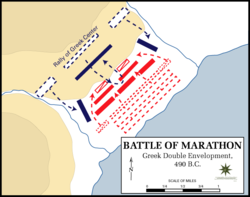

Stalemate ensued for five days, before the Athenians (for reasons that are not completely clear) decided to attack the Persians. Despite the numerical advantage of the Persians, the hoplites proved devastatingly effective, routing the Persians wings before turning in on the centre of the Persian line; the remnants of the Persian army left the battle and fled to their ships. Herodotus records that 6,400 Persian bodies were counted on the battlefield; the Athenians lost just 192 men and the Plataeans 11.

In the immediate aftermath of the battle, Herodotus says that the Persian fleet sailed around Cape Sunium to attack Athens directly, although some modern historians place this attempt just before the battle. Either way, the Athenians evidently realised that their city was still under threat, and marched as quickly as possible back to Athens. The Athenians arrived in time to prevent the Persians from securing a landing, and seeing that the opportunity was lost, the Persians turned about and returned to Asia. On the next day, the Spartan army arrived, having covered the 220 kilometres (136.7 mi) in only three days. The Spartans toured the battlefield at Marathon, and agreed that the Athenians had won a great victory.

The defeat at Marathon ended for the time being the Persian invasion of Greece. However, Thrace and the Cycladic islands had been absorbed into the Persian empire, and Macedon reduced to a Persian vassal. Darius was still fully intent on conquering Greece, to secure the western part of his empire. Moreover, Athens remained unpunished for its role in the Ionian Revolt, and both Athens and Sparta were unpunished for their treatment of the Persian ambassadors.

The defeat at Marathon ended for the time being the Persian invasion of Greece. However, Thrace and the Cycladic islands had been absorbed into the Persian empire, and Macedon reduced to a Persian vassal. Darius was still fully intent on conquering Greece, to secure the western part of his empire. Moreover, Athens remained unpunished for its role in the Ionian Revolt, and both Athens and Sparta were unpunished for their treatment of the Persian ambassadors.

Darius therefore began raising a huge new army with which he meant to completely subjugate Greece; however, in 486 BCE, his Egyptian

subjects revolted, indefinitely postponing any Greek expedition. Darius then died whilst preparing to march on Egypt, and the throne of Persia passed to his son Xerxes I. Xerxes crushed the Egyptian revolt, and very quickly re-started the preparations for the invasion of Greece. This expedition was finally ready by 480 BCE, and the second Persian invasion of Greece

thereby began, under the command of Xerxes himself.

The victory at Marathon was a defining moment for the young Athenian democracy, showing what might be achieved through unity and self-belief; indeed, the battle effectively marks the start of a 'golden age' for Athens. This was also applicable to Greece as a whole; "their victory endowed the Greeks with a faith in their destiny that was to endure for three centuries, during which western culture was born". John Stuart Mill

's famous opinion was that "the Battle of Marathon, even as an event in British history, is more important than the Battle of Hastings

".

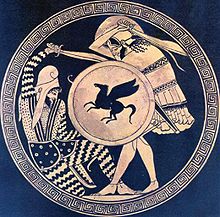

Militarily, a major lesson for the Greeks was the potential of the hoplite phalanx. This style had developed during internecine warfare amongst the Greeks; since each city-state fought in the same way, the advantages and disadvantages of the hoplite phalanx had not been obvious. Marathon was the first time a phalanx faced more lightly armed troops, and revealed how devastating the hoplites could be in battle. The phalanx formation was still vulnerable to cavalry (the cause of much caution by the Greek forces at the Battle of Plataea

), but used in the right circumstances, it was now shown to be a potentially devastating weapon. The Persians seem to have more-or-less disregarded the military lessons of Marathon. The composition of infantry for the second invasion seems to have been the same as during the first, despite the availability of hoplites and other heavy infantry in Persian-ruled lands. Having won battles against hoplites previously, the Persians may simply have regarded Marathon as an aberration.

Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire , sometimes known as First Persian Empire and/or Persian Empire, was founded in the 6th century BCE by Cyrus the Great who overthrew the Median confederation...

invasion of Greece

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

, during the Persian Wars, began in 492 BCE, and ended with the decisive Athenian victory at the Battle of Marathon

Battle of Marathon

The Battle of Marathon took place in 490 BC, during the first Persian invasion of Greece. It was fought between the citizens of Athens, aided by Plataea, and a Persian force commanded by Datis and Artaphernes. It was the culmination of the first attempt by Persia, under King Darius I, to subjugate...

in 490 BCE. The invasion, consisting of two distinct campaigns, was ordered by the Persian king Darius I primarily in order to punish the city-states of Athens

Athens

Athens , is the capital and largest city of Greece. Athens dominates the Attica region and is one of the world's oldest cities, as its recorded history spans around 3,400 years. Classical Athens was a powerful city-state...

and Eretria

Eretria

Erétria was a polis in Ancient Greece, located on the western coast of the island of Euboea, south of Chalcis, facing the coast of Attica across the narrow Euboean Gulf. Eretria was an important Greek polis in the 6th/5th century BC. However, it lost its importance already in antiquity...

. These cities had supported the cities of Ionia

Ionia

Ionia is an ancient region of central coastal Anatolia in present-day Turkey, the region nearest İzmir, which was historically Smyrna. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements...

during their revolt

Ionian Revolt

The Ionian Revolt, and associated revolts in Aeolis, Doris, Cyprus and Caria, were military rebellions by several regions of Asia Minor against Persian rule, lasting from 499 BC to 493 BC...

against Persian rule, thus incurring the wrath of Darius. Darius also saw the opportunity to extend his empire into Europe, and to secure its western frontier.

The first campaign in 492 BCE, led by Mardonius

Mardonius

Mardonius was a leading Persian military commander during the Persian Wars with Greece in the early 5th century BC.-Early years:Mardonius was the son of Gobryas, a Persian nobleman who had assisted the Achaemenid prince Darius when he claimed the throne...

, re-subjugated Thrace

Thrace

Thrace is a historical and geographic area in southeast Europe. As a geographical concept, Thrace designates a region bounded by the Balkan Mountains on the north, Rhodope Mountains and the Aegean Sea on the south, and by the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara on the east...

and forced Macedon

Macedon

Macedonia or Macedon was an ancient kingdom, centered in the northeastern part of the Greek peninsula, bordered by Epirus to the west, Paeonia to the north, the region of Thrace to the east and Thessaly to the south....

to become a client kingdom of Persia. However, further progress was prevented when Mardonius's fleet was wrecked in a storm off the coast of Mount Athos

Mount Athos

Mount Athos is a mountain and peninsula in Macedonia, Greece. A World Heritage Site, it is home to 20 Eastern Orthodox monasteries and forms a self-governed monastic state within the sovereignty of the Hellenic Republic. Spiritually, Mount Athos comes under the direct jurisdiction of the...

. The following year, having demonstrated his intentions, Darius sent ambassadors to all parts of Greece, demanding their submission. He received it from almost all of them, excepting Athens and Sparta

Sparta

Sparta or Lacedaemon, was a prominent city-state in ancient Greece, situated on the banks of the River Eurotas in Laconia, in south-eastern Peloponnese. It emerged as a political entity around the 10th century BC, when the invading Dorians subjugated the local, non-Dorian population. From c...

, both of whom executed the ambassadors. With Athens still defiant, and Sparta now effectively at war with him, Darius ordered a further military campaign for the following year.

The second campaign, in 490 BCE, was under the command of Datis

Datis

For other uses of the word Dati, see Dati .Datis or Datus was a Median admiral who served the Persian Empire, under Darius the Great...

and Artaphernes

Artaphernes (son of Artaphernes)

Artaphernes, son of Artaphernes, was the nephew of Darius the Great, and a general of the Achaemenid Empire.He was appointed, together with Datis, to take command of the expedition sent by Darius to punish Athens and Eretria for their support for the Ionian Revolt. Artaphernes and Datis besieged...

. The expedition headed first to the island Naxos, which it captured and burnt. It then island-hopped between the rest of the Cycladic Islands

Cyclades

The Cyclades is a Greek island group in the Aegean Sea, south-east of the mainland of Greece; and a former administrative prefecture of Greece. They are one of the island groups which constitute the Aegean archipelago. The name refers to the islands around the sacred island of Delos...

, annexing each into the Persian empire. Reaching Greece, the expedition landed at Eretria, which it besieged, and after a brief time, captured. Eretria was razed and its citizens enslaved. Finally, the task force headed to Attica

Attica

Attica is a historical region of Greece, containing Athens, the current capital of Greece. The historical region is centered on the Attic peninsula, which projects into the Aegean Sea...

, landing at Marathon

Marathon, Greece

Marathon is a town in Greece, the site of the battle of Marathon in 490 BC, in which the heavily outnumbered Athenian army defeated the Persians. The tumulus or burial mound for the 192 Athenian dead that was erected near the battlefield remains a feature of the coastal plain...

, en route for Athens. There, it was met by a smaller Athenian army, which nevertheless proceeded to win a remarkable victory at the Battle of Marathon

Battle of Marathon

The Battle of Marathon took place in 490 BC, during the first Persian invasion of Greece. It was fought between the citizens of Athens, aided by Plataea, and a Persian force commanded by Datis and Artaphernes. It was the culmination of the first attempt by Persia, under King Darius I, to subjugate...

.

This defeat prevented the successful conclusion of the campaign, and the task force returned to Asia. Nevertheless, the expedition had fulfilled most of its aims, punishing Naxos and Eretria, and bringing much of the Aegean under Persian rule. The unfinished business from this campaign led Darius to prepare for a much larger invasion of Greece, to firmly subjugate it, and to punish Athens and Sparta. However, internal strife within the empire delayed this expedition, and Darius then died of old age. It was thus left to his son Xerxes I to lead the second Persian invasion of Greece

Second Persian invasion of Greece

The second Persian invasion of Greece occurred during the Greco-Persian Wars, as King Xerxes I of Persia sought to conquer all of Greece. The invasion was a direct, if delayed, response to the defeat of the first Persian invasion of Greece at the Battle of Marathon which ended Darius I's attempts...

, beginning in 480 BCE

Sources

The main source for the Greco-Persian Wars is the Greek historian HerodotusHerodotus

Herodotus was an ancient Greek historian who was born in Halicarnassus, Caria and lived in the 5th century BC . He has been called the "Father of History", and was the first historian known to collect his materials systematically, test their accuracy to a certain extent and arrange them in a...

. Herodotus, who has been called the 'Father of History', was born in 484 BCE in Halicarnassus, Asia Minor (then under Persian overlordship). He wrote his 'Enquiries' (Greek—Historia; English—(The) Histories

Histories (Herodotus)

The Histories of Herodotus is considered one of the seminal works of history in Western literature. Written from the 450s to the 420s BC in the Ionic dialect of classical Greek, The Histories serves as a record of the ancient traditions, politics, geography, and clashes of various cultures that...

) around 440–430 BCE, trying to trace the origins of the Greco-Persian Wars, which would still have been relatively recent history (the wars finally ending in 450 BCE). Herodotus's approach was entirely novel, and at least in Western society, he does seem to have invented 'history' as we know it. As Holland has it: "For the first time, a chronicler set himself to trace the origins of a conflict not to a past so remote so as to be utterly fabulous, nor to the whims and wishes of some god, nor to a people's claim to manifest destiny, but rather explanations he could verify personally."

Some subsequent ancient historians, despite following in his footsteps, criticised Herodotus, starting with Thucydides

Thucydides

Thucydides was a Greek historian and author from Alimos. His History of the Peloponnesian War recounts the 5th century BC war between Sparta and Athens to the year 411 BC...

. Nevertheless, Thucydides chose to begin his history where Herodotus left off (at the Siege of Sestos), and therefore evidently felt that Herodotus's history was accurate enough not to need re-writing or correcting. Plutarch

Plutarch

Plutarch then named, on his becoming a Roman citizen, Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus , c. 46 – 120 AD, was a Greek historian, biographer, essayist, and Middle Platonist known primarily for his Parallel Lives and Moralia...

criticised Herodotus in his essay "On The Malignity of Herodotus", describing Herodotus as "Philobarbaros" (barbarian-lover), for not being pro-Greek enough, which suggests that Herodotus might actually have done a reasonable job of being even-handed. A negative view of Herodotus was passed on to Renaissance Europe, though he remained well read. However, since the 19th century his reputation has been dramatically rehabilitated by archaeological finds which have repeatedly confirmed his version of events. The prevailing modern view is that Herodotus generally did a remarkable job in his Historia, but that some of his specific details (particularly troop numbers and dates) should be viewed with skepticism. Nevertheless, there are still some historians who believe Herodotus made up much of his story.

The Sicilian historian Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus was a Greek historian who flourished between 60 and 30 BC. According to Diodorus' own work, he was born at Agyrium in Sicily . With one exception, antiquity affords no further information about Diodorus' life and doings beyond what is to be found in his own work, Bibliotheca...

, writing in the 1st century BCE in his Bibliotheca Historica

Bibliotheca historica

Bibliotheca historica , is a work of universal history by Diodorus Siculus. It consisted of forty books, which were divided into three sections. The first six books are geographical in theme, and describe the history and culture of Egypt , of Mesopotamia, India, Scythia, and Arabia , of North...

, also provides an account of the Greco-Persian wars, partially derived from the earlier Greek historian Ephorus

Ephorus

Ephorus or Ephoros , of Cyme in Aeolia, in Asia Minor, was an ancient Greek historian. Information on his biography is limited; he was the father of Demophilus, who followed in his footsteps as a historian, and to Plutarch's claim that Ephorus declined Alexander the Great's offer to join him on his...

. This account is fairly consistent with Herodotus's. The Greco-Persian wars are also described in less detail by a number of other ancient historians including Plutarch, Ctesias of Cnidus, and are alluded by other authors, such as the playwright Aeschylus

Aeschylus

Aeschylus was the first of the three ancient Greek tragedians whose work has survived, the others being Sophocles and Euripides, and is often described as the father of tragedy. His name derives from the Greek word aiskhos , meaning "shame"...

. Archaeological evidence, such as the Serpent Column

Serpent Column

The Serpent Column — also known as the Serpentine Column, Delphi Tripod or Plataean Tripod — is an ancient bronze column at the Hippodrome of Constantinople in what is now Istanbul, Turkey...

, also supports some of Herodotus's specific claims.

Background

The first Persian invasion of Greece had its immediate roots in the Ionian RevoltIonian Revolt

The Ionian Revolt, and associated revolts in Aeolis, Doris, Cyprus and Caria, were military rebellions by several regions of Asia Minor against Persian rule, lasting from 499 BC to 493 BC...

, the earliest phase of the Greco-Persian Wars

Greco-Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire of Persia and city-states of the Hellenic world that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of the Greeks and the enormous empire of the Persians began when Cyrus...

. However, it was also the result of the longer-term interaction between the Greeks and Persians. In 500 BCE the Persian Empire was still relatively young and highly expansionistic, but prone to revolts amongst its subject peoples. Moreover, the Persian king Darius was a usurper, and had spent considerable time extinguishing revolts against his rule. Even before the Ionian Revolt, Darius had begun to expand the Empire into Europe, subjugating Thrace

Thrace

Thrace is a historical and geographic area in southeast Europe. As a geographical concept, Thrace designates a region bounded by the Balkan Mountains on the north, Rhodope Mountains and the Aegean Sea on the south, and by the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara on the east...

, and forcing Macedon to become allied to Persia. Attempts at further expansion into the politically fractious world of Ancient Greece may have been inevitable. However, the Ionian Revolt had directly threatened the integrity of the Persian empire, and the states of mainland Greece remained a potential menace to its future stability. Darius thus resolved to subjugate and pacify Greece and the Aegean, and to punish those involved in the Ionian Revolt.

The Ionian revolt had begun with an unsuccessful expedition against Naxos

Naxos (island)

Naxos is a Greek island, the largest island in the Cyclades island group in the Aegean. It was the centre of archaic Cycladic culture....

, a joint venture between the Persian satrap Artaphernes

Artaphernes

Artaphernes , was the brother of the king of Persia, Darius I of Persia, and satrap of Sardis.In 497 BC, Artaphernes received an embassy from Athens, probably sent by Cleisthenes, and subsequently advised the Athenians that they should receive back the tyrant Hippias.Subsequently he took an...

and the Miletus

Miletus

Miletus was an ancient Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia , near the mouth of the Maeander River in ancient Caria...

tyrant Aristagoras

Aristagoras

Aristagoras was the leader of Miletus in the late 6th century BC and early 5th century BC.- Background :Aristagoras served as deputy governor of Miletus, a polis on the western coast of Anatolia around 500 BC. He was the son of Molpagoras, and son-in-law of Histiaeus, whom the Persians had set up...

. In the aftermath, Artaphernes decided to remove Aristagoras from power, but before he could do so, Aristagoras abdicated, and declared Miletus a democracy. The other Ionia

Ionia

Ionia is an ancient region of central coastal Anatolia in present-day Turkey, the region nearest İzmir, which was historically Smyrna. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements...

n cities, ripe for rebellion, followed suit, ejecting their Persian-appointed tyrants, and declaring themselves democracies. Artistagoras then appealed to the states of Mainland Greece for support, but only Athens

History of Athens

Athens is one of the oldest named cities in the world, having been continuously inhabited for at least 7000 years. Situated in southern Europe, Athens became the leading city of Ancient Greece in the first millennium BCE and its cultural achievements during the 5th century BCE laid the foundations...

and Eretria

Eretria

Erétria was a polis in Ancient Greece, located on the western coast of the island of Euboea, south of Chalcis, facing the coast of Attica across the narrow Euboean Gulf. Eretria was an important Greek polis in the 6th/5th century BC. However, it lost its importance already in antiquity...

offered to send troops.

The involvement of Athens in the Ionian Revolt arose from a complex set of circumstances, beginning with the establishment of the Athenian Democracy

Athenian democracy

Athenian democracy developed in the Greek city-state of Athens, comprising the central city-state of Athens and the surrounding territory of Attica, around 508 BC. Athens is one of the first known democracies. Other Greek cities set up democracies, and even though most followed an Athenian model,...

in the late 6th century BCE

In 510 BCE, with the aid of Cleomenes I

Cleomenes I

Cleomenes or Kleomenes was an Agiad King of Sparta in the late 6th and early 5th centuries BC. During his reign, which started around 520 BC, he pursued an adventurous and at times unscrupulous foreign policy aimed at crushing Argos and extending Sparta's influence both inside and outside the...

, King of Sparta

Sparta

Sparta or Lacedaemon, was a prominent city-state in ancient Greece, situated on the banks of the River Eurotas in Laconia, in south-eastern Peloponnese. It emerged as a political entity around the 10th century BC, when the invading Dorians subjugated the local, non-Dorian population. From c...

, the Athenian people had expelled Hippias, the tyrant

Tyrant

A tyrant was originally one who illegally seized and controlled a governmental power in a polis. Tyrants were a group of individuals who took over many Greek poleis during the uprising of the middle classes in the sixth and seventh centuries BC, ousting the aristocratic governments.Plato and...

ruler of Athens. With Hippias's father Peisistratus

Peisistratos (Athens)

Peisistratos was a tyrant of Athens from 546 to 527/8 BC. His legacy lies primarily in his institution of the Panathenaic Festival and the consequent first attempt at producing a definitive version for Homeric epics. Peisistratos' championing of the lower class of Athens, the Hyperakrioi, can be...

, the family had ruled for 36 out of the previous 50 years and fully intended to continue Hippias's rule. Hippias fled to Sardis

Sardis

Sardis or Sardes was an ancient city at the location of modern Sart in Turkey's Manisa Province...

to the court of the Persian satrap

Satrap

Satrap was the name given to the governors of the provinces of the ancient Median and Achaemenid Empires and in several of their successors, such as the Sassanid Empire and the Hellenistic empires....

, Artaphernes

Artaphernes

Artaphernes , was the brother of the king of Persia, Darius I of Persia, and satrap of Sardis.In 497 BC, Artaphernes received an embassy from Athens, probably sent by Cleisthenes, and subsequently advised the Athenians that they should receive back the tyrant Hippias.Subsequently he took an...

and promised control of Athens to the Persians if they were to help restore him. In the meantime, Cleomenes helped install a pro-Spartan tyranny under Isagoras

Isagoras

Isagoras , son of Tisander, was an Athenian aristocrat in the late 6th century BC.He had remained in Athens during the tyranny of Hippias, but after Hippias was overthrown, he became involved in a struggle for power with Cleisthenes, a fellow aristocrat. In 508 BC he was elected archon eponymous,...

in Athens, in opposition to Cleisthenes

Cleisthenes

Cleisthenes was a noble Athenian of the Alcmaeonid family. He is credited with reforming the constitution of ancient Athens and setting it on a democratic footing in 508/7 BC...

, the leader of the traditionally powerful Alcmaeonidae

Alcmaeonidae

The Alcmaeonidae or Alcmaeonids were a powerful noble family of ancient Athens, a branch of the Neleides who claimed descent from the mythological Alcmaeon, the great-grandson of Nestor....

family, who considered themselves the natural heirs to the rule of Athens. In a daring response, Cleisthenes proposed to the Athenian people that he would establish a 'democracy

Democracy

Democracy is generally defined as a form of government in which all adult citizens have an equal say in the decisions that affect their lives. Ideally, this includes equal participation in the proposal, development and passage of legislation into law...

' in Athens, much to the horror of the rest of the aristocracy. Cleisthenes's reasons for suggesting such a radical course of action, which would remove much of his own family's power, are unclear; perhaps he perceived that days of aristocratic rule were coming to an end anyway; certainly he wished to prevent Athens becoming a puppet of Sparta by whatever means necessary. However, as a result of this proposal, Cleisthenes and his family were exiled from Athens, in addition to other dissenting elements, by Isagoras. Having been promised democracy however, the Athenian people seized the moment and revolted, expelling Cleomenes and Isagoras. Cleisthenes was thus restored to Athens (507 BCE), and at breakneck speed began to establish democratic government. The establishment of democracy revolutionised Athens, which henceforth became one of the leading cities in Greece. The new found freedom and self-governance of the Athenians meant that they were thereafter exceptionally hostile to the return of the tyranny of Hippias, or any form of outside subjugation; by Sparta, Persia or anyone else.

The city of Eretria also sent assistance to the Ionians for reasons that are not completely clear. Possibly commercial reasons were a factor; Eretria was a mercantile city, whose trade was threatened by Persian dominance of the Aegean. Herodotus suggests that the Eretrians supported the revolt in order to repay the support the Milesians

Miletus

Miletus was an ancient Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia , near the mouth of the Maeander River in ancient Caria...

had given Eretria in a past war against Chalcis

Chalcis

Chalcis or Chalkida , the chief town of the island of Euboea in Greece, is situated on the strait of the Evripos at its narrowest point. The name is preserved from antiquity and is derived from the Greek χαλκός , though there is no trace of any mines in the area...

.

The Athenians and Eretrians sent a task force of 25 triremes to Asia Minor. Whilst there, the Greek army surprised and outmaneuvered Artaphernes, marching to Sardis and there burning the lower city. However, this was as much as the Greeks achieved, and they were then pursued back to the coast by Persian horsemen, losing many men in the process. Despite the fact their actions were ultimately fruitless, the Eretrians and in particular the Athenians had earned Darius's lasting enmity, and he vowed to punish both cities. The Persian naval victory at the Battle of Lade

Battle of Lade

The Battle of Lade was a naval battle which occurred during the Ionian Revolt, in 494 BC. It was fought between an alliance of the Ionian cities and the Persian Empire of Darius the Great, and resulted in a decisive victory for the Persians which all but ended the revolt.The Ionian Revolt was...

(494 BCE) all but ended the Ionian Revolt, and by 493 BCE, the last hold-outs were vanquished by the Persian fleet. The revolt was used as an opportunity by Darius to extend the empire's border to the islands of the East Aegean and the Propontis, which had not been part of the Persian dominions before. The completion of the pacification of Ionia allowed the Persians to begin planning their next moves; to extinguish the threat to the empire from Greece, and to punish Athens and Eretria.

492 BCE: Mardonius's Campaign

From thence the fleet continued on to the Hellespont, and when all was ready, shipped the land forces across to Europe. The army then marched through Thrace, re-subjugating it, since these lands had already been added to the Persian empire in 512 BCE, during Darius's campaign against the Scythia

Scythia

In antiquity, Scythian or Scyths were terms used by the Greeks to refer to certain Iranian groups of horse-riding nomadic pastoralists who dwelt on the Pontic-Caspian steppe...

ns. Upon reaching Macedon, the Persians forced the Macedonians to become a client kingdom of the Persians; before they had been allied to, but independent of the Persians.

Meanwhile, the fleet crossed to Thassos, resulting in the Thasians submitting to the Persians. The fleet then rounded the coastline as far as Acanthus

Acanthus (Greece)

Ierissos Modern Greek: or Acanthus was an ancient Greek city on the Athos peninsula. It was located on the north-east side of Akti, on the most eastern peninsula of Chalcidice...

in Chalcidice

Chalcidice

Chalkidiki, also Halkidiki, Chalcidice or Chalkidike , is a peninsula in northern Greece, and one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of Central Macedonia. The autonomous Mount Athos region is part of the peninsula, but not of the regional unit...

, before attempting to round the headland of Mount Athos

Mount Athos

Mount Athos is a mountain and peninsula in Macedonia, Greece. A World Heritage Site, it is home to 20 Eastern Orthodox monasteries and forms a self-governed monastic state within the sovereignty of the Hellenic Republic. Spiritually, Mount Athos comes under the direct jurisdiction of the...

. However, they were caught in a violent storm, which drove them against the coastline of Athos, wrecking (according to Herodotus) 300 ships, with the loss of 20,000 men.

Then, whilst the army was camped in Macedon, the Brygians, a local Thracian tribe, launched a night raid against the Persian camp, killing many of the Persians, and wounding Mardonius. Despite his injury, Mardonius made sure that the Brygians were defeated and subjugated, before leading his army back to the Hellespont; the remnants of the navy also retreated to Asia. Although this campaign ended ingloriously, the land approaches to Greece had been secured, and the Greeks had no doubt been made aware of Darius's intentions for them.

491 BCE: Diplomacy

Perhaps reasoning that the expedition of the previous year may have made his plans for Greece obvious, and weakened the resolve of the Greek cities, Darius turned to diplomacy in 491 BCE He sent ambassadors to all the Greek city states, asking for "earth and water", a traditional token of submission. The vast majority of cities did as asked, fearing the wrath of Darius. In Athens, however, the ambassadors were put on trial and then executed; in Sparta, they were simply thrown down a well. This firmly and finally drew the battle-lines for the coming conflict; Sparta and Athens, despite their recent enmity, would together fight the Persians.However, Sparta was then thrown into disarray by internal machinations. The citizens of Aegina

Aegina

Aegina is one of the Saronic Islands of Greece in the Saronic Gulf, from Athens. Tradition derives the name from Aegina, the mother of Aeacus, who was born in and ruled the island. During ancient times, Aegina was a rival to Athens, the great sea power of the era.-Municipality:The municipality...

had submitted to the Persian ambassadors, and the Athenians, troubled by the possibility of Persia using Aegina as a naval base, asked Sparta to intervene. Cleomenes travelled to Aegina to confront the Aeginetans personally, but they appealed to Cleomenes's fellow king Demaratus

Demaratus

Demaratus was a king of Sparta from 515 until 491 BC, of the Eurypontid line, successor to his father Ariston. As king, he is known chiefly for his opposition to the other, co-ruling Spartan king, Cleomenes I.-Biography:...

, who supported their stance. Cleomenes responded by having Demaratus declared illegitimate, with the help of the priests at Delphi

Delphi

Delphi is both an archaeological site and a modern town in Greece on the south-western spur of Mount Parnassus in the valley of Phocis.In Greek mythology, Delphi was the site of the Delphic oracle, the most important oracle in the classical Greek world, and a major site for the worship of the god...

(whom he bribed); Demaratus was replaced by his cousin Leotychides. Now faced with two Spartan kings, the Aeginetans capitulated, and handed over hostages to the Athenians as a guarantee of their good behaviour. However, in Sparta news emerged of the bribes Cleomenes had given at Delphi, and he was expelled from the city. He then sought to rally the northern Peloponnesus to his cause, at which the Spartans relented, and invited him back to the city. By 491 BCE though, Cleomenes was widely considered insane and was sentenced to prison where he was found dead the following day. Cleomenes was succeeded by his half-brother Leonidas I

Leonidas I

Leonidas I was a hero-king of Sparta, the 17th of the Agiad line, one of the sons of King Anaxandridas II of Sparta, who was believed in mythology to be a descendant of Heracles, possessing much of the latter's strength and bravery...

.

490 BCE: Datis and Artaphernes' Campaign

Taking advantage of the chaos in Sparta, which effectively left Athens isolated, Darius decided to launch an amphibious expedition to finally punish Athens and Eretria. An army was assembled in SusaSusa

Susa was an ancient city of the Elamite, Persian and Parthian empires of Iran. It is located in the lower Zagros Mountains about east of the Tigris River, between the Karkheh and Dez Rivers....

, and marched into Cilicia

Cilicia

In antiquity, Cilicia was the south coastal region of Asia Minor, south of the central Anatolian plateau. It existed as a political entity from Hittite times into the Byzantine empire...

, where a fleet had been gathered. Command of the expedition was given to Datis

Datis

For other uses of the word Dati, see Dati .Datis or Datus was a Median admiral who served the Persian Empire, under Darius the Great...

the Mede and Artaphernes

Artaphernes (son of Artaphernes)

Artaphernes, son of Artaphernes, was the nephew of Darius the Great, and a general of the Achaemenid Empire.He was appointed, together with Datis, to take command of the expedition sent by Darius to punish Athens and Eretria for their support for the Ionian Revolt. Artaphernes and Datis besieged...

, son of the satrap Artaphernes

Artaphernes

Artaphernes , was the brother of the king of Persia, Darius I of Persia, and satrap of Sardis.In 497 BC, Artaphernes received an embassy from Athens, probably sent by Cleisthenes, and subsequently advised the Athenians that they should receive back the tyrant Hippias.Subsequently he took an...

.

Size of the Persian force

According to Herodotus, the fleet sent by Darius consisted of 600 triremeTrireme

A trireme was a type of galley, a Hellenistic-era warship that was used by the ancient maritime civilizations of the Mediterranean, especially the Phoenicians, ancient Greeks and Romans.The trireme derives its name from its three rows of oars on each side, manned with one man per oar...

s. There is no indication in the historical sources of how many transport ships accompanied them, if any. Herodotus claimed that 3,000 transport ships accompanied 1,207 triremes during Xerxes

Xerxes I of Persia

Xerxes I of Persia , Ḫšayāršā, ), also known as Xerxes the Great, was the fifth king of kings of the Achaemenid Empire.-Youth and rise to power:...

's invasion

Second Persian invasion of Greece

The second Persian invasion of Greece occurred during the Greco-Persian Wars, as King Xerxes I of Persia sought to conquer all of Greece. The invasion was a direct, if delayed, response to the defeat of the first Persian invasion of Greece at the Battle of Marathon which ended Darius I's attempts...

in 480 BCE. Amongst modern historians, some have accepted this number of ships as reasonable; it has been suggested either that the number 600 represents the combined number of triremes and transport ships, or that there were horse transports in addition to 600 triremes.

Herodotus does not estimate the size of the Persian army, only saying that they formed a "large infantry that was well packed". Among other ancient sources, the poet Simonides

Simonides of Ceos

Simonides of Ceos was a Greek lyric poet, born at Ioulis on Kea. The scholars of Hellenistic Alexandria included him in the canonical list of nine lyric poets, along with Bacchylides and Pindar...

, a near-contemporary, says the campaign force numbered 200,000, while a later writer, the Roman Cornelius Nepos

Cornelius Nepos

Cornelius Nepos was a Roman biographer. He was born at Hostilia, a village in Cisalpine Gaul not far from Verona. His Gallic origin is attested by Ausonius, and Pliny the Elder calls him Padi accola...

estimates 200,000 infantry and 10,000 cavalry. Plutarch

Plutarch

Plutarch then named, on his becoming a Roman citizen, Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus , c. 46 – 120 AD, was a Greek historian, biographer, essayist, and Middle Platonist known primarily for his Parallel Lives and Moralia...

and Pausanias

Pausanias (geographer)

Pausanias was a Greek traveler and geographer of the 2nd century AD, who lived in the times of Hadrian, Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius. He is famous for his Description of Greece , a lengthy work that describes ancient Greece from firsthand observations, and is a crucial link between classical...

both independently give 300,000, as does the Suda

Suda

The Suda or Souda is a massive 10th century Byzantine encyclopedia of the ancient Mediterranean world, formerly attributed to an author called Suidas. It is an encyclopedic lexicon, written in Greek, with 30,000 entries, many drawing from ancient sources that have since been lost, and often...

dictionary; Plato

Plato

Plato , was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Along with his mentor, Socrates, and his student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the...

and Lysias

Lysias

Lysias was a logographer in Ancient Greece. He was one of the ten Attic orators included in the "Alexandrian Canon" compiled by Aristophanes of Byzantium and Aristarchus of Samothrace in the third century BC.-Life:According to Dionysius of Halicarnassus and the author of the life ascribed to...

assert 500,000; and Justin 600,000.

Modern historians generally dismiss these numbers as exaggerations. One approach to estimate the number of troops is to calculate the number of marines carried by 600 triremes. Herodotus tells us that each trireme in the second invasion of Greece carried 30 extra marines, in addition to a probable 14 standard marines. Thus, 600 triremes could easily have carried 18,000–26,000 infantry. Numbers proposed for the Persian infantry are in the range 18,000–100,000. However, the consensus is probably somewhere in the range of 25,000.

The Persian infantry used in the invasion was probably a heterogeneous group drawn from across the empire. However, according to Herodotus, there was at least a general conformity in the type of armour and style of fighting. The troops were, generally speaking, armed with a bow, 'short spear' and sword, carried a wicker shield, and wore at most a leather jerkin. The one exception to this may have been the ethnic Persian troops, who may have worn a corslet of scaled armour. Some of contingents would have been armed somewhat differently; for instance, the Saka

Saka

The Saka were a Scythian tribe or group of tribes....

were renowned axemen. The 'elite' contingents of the Persian infantry seem to have been the ethnic Persians, Medians

Medes

The MedesThe Medes...

, Cissians and the Saka; Herodotus specifically mentions the presence of Persians and Saka at Marathon. The style of fighting used by the Persians was probably to stand off from an enemy, using their bows (or equivalent) to wear down the enemy before closing in to deliver the coup de grace with spear and sword.

Estimates for the cavalry are usually in the 1,000–3,000 range. The Persian cavalry was usually provided by the ethnic Persians, Bactria

Bactria

Bactria and also appears in the Zend Avesta as Bukhdi. It is the ancient name of a historical region located between south of the Amu Darya and west of the Indus River...

ns, Medes, Cissians and Saka; most of these probably fought as lightly armed missile cavalry. The fleet must have had at least some proportion of transport ships, since the cavalry was carried by ship; whilst Herodotus claims the cavalry was carried in the triremes, this is improbable. Lazenby estimates 30–40 transport ships would be required to carry 1,000 cavalry.

Lindos

Once assembled, the Persian force sailed from Cilicia firstly to the island of RhodesRhodes

Rhodes is an island in Greece, located in the eastern Aegean Sea. It is the largest of the Dodecanese islands in terms of both land area and population, with a population of 117,007, and also the island group's historical capital. Administratively the island forms a separate municipality within...

. A Lindian Temple Chronicle records that Datis

Datis

For other uses of the word Dati, see Dati .Datis or Datus was a Median admiral who served the Persian Empire, under Darius the Great...

besieged the city of Lindos

Lindos

Lindos is an archaeological site, a town and a former municipality on the island of Rhodes, in the Dodecanese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Rhodes, of which it is a municipal unit. It lies on the east coast of the island...

, but was unsuccessful.

Naxos

The fleet then moved north along the Ionian coast towards SamosSamos Island

Samos is a Greek island in the eastern Aegean Sea, south of Chios, north of Patmos and the Dodecanese, and off the coast of Asia Minor, from which it is separated by the -wide Mycale Strait. It is also a separate regional unit of the North Aegean region, and the only municipality of the regional...

, before abruptly turning west into the Aegean Sea. The fleet sailed next to Naxos, in order to punish the Naxians for their resistance to the failed expedition that the Persians had mounted there a decade earlier. Many of the inhabitants fled to the mountains; those that the Persians caught were enslaved. The Persians then burnt the city and temples of the Naxians.

The Cyclades

Delos

The island of Delos , isolated in the centre of the roughly circular ring of islands called the Cyclades, near Mykonos, is one of the most important mythological, historical and archaeological sites in Greece...

, whereupon the Delians also fled from their homes. Having demonstrated Persian power at Naxos, Datis now intended to show clemency to the other islands, if they submitted to him. He sent a herald to the Delians, proclaiming:

"Holy men, why have you fled away, and so misjudged my intent? It is my own desire, and the king's command to me, to do no harm to the land where the two gods were born, neither to the land itself nor to its inhabitants. So return now to your homes and dwell on your island."Datis then burned 300 talents of frankincense on the altar of Apollo

Apollo

Apollo is one of the most important and complex of the Olympian deities in Greek and Roman mythology...

on Delos, to show his respect for one of the gods of the island. The fleet then proceeded to island-hop across the rest of Aegean on its way to Eretria, taking hostages and troops from each island.

Karystos

The Persians finally arrived off the southern tip of Euboea, at KarystosKarystos

Karystos is a small coastal town on the Greek island of Euboea. It has about 7,000 inhabitants. It lies 129 km south of Chalkis. From Athens it is accessible by ferry via Marmari from the Rafina port...

. The citizens of Karystos refused to give hostages to the Persians, so they were besieged, and their land ravaged, until they submitted to the Persians.

Siege of Eretria

The task force then sailed around Euboea to the first major target, Eretria. According to Herodotus, the Eretrians were divided amongst themselves as to the best course of action; whether to flee to the highlands, or undergo a siege, or to submit to the Persians. In the event, the majority decision was to remain in the city. The Eretrians made no attempt to stop the Persians landing, or advancing, and thus allowed themselves to be besieged. For six days the Persians attacked the walls, with losses on both sides; however, on the seventh day two reputable Eretrians opened the gates and betrayed the city to the Persians. The city was razed, and temples and shrines were looted and burned. Furthermore, according to Darius's commands, the Persians enslaved all the remaining townspeople.Battle of Marathon

Plataea

Plataea or Plataeae was an ancient city, located in Greece in southeastern Boeotia, south of Thebes. It was the location of the Battle of Plataea in 479 BC, in which an alliance of Greek city-states defeated the Persians....

, marched to Marathon, and succeeded in blocking the two exits from the plain of Marathon. At the same time, Athens' greatest runner, Pheidippides

Pheidippides

Pheidippides , hero of Ancient Greece, is the central figure in a story which was the inspiration for a modern sporting event, the marathon.-The story:...

(or Philippides) was sent to Sparta to request that the Spartan army march to Athens' aid. Pheidippides arrived during the festival of Carneia, a sacrosanct period of peace, and was informed that the Spartan army could not march to war until the full moon rose; Athens could not expect reinforcement for at least ten days. They decided to hold out at Marathon for the time being, and they were reinforced by a contingent of hoplites from Plataea.

Stalemate ensued for five days, before the Athenians (for reasons that are not completely clear) decided to attack the Persians. Despite the numerical advantage of the Persians, the hoplites proved devastatingly effective, routing the Persians wings before turning in on the centre of the Persian line; the remnants of the Persian army left the battle and fled to their ships. Herodotus records that 6,400 Persian bodies were counted on the battlefield; the Athenians lost just 192 men and the Plataeans 11.

In the immediate aftermath of the battle, Herodotus says that the Persian fleet sailed around Cape Sunium to attack Athens directly, although some modern historians place this attempt just before the battle. Either way, the Athenians evidently realised that their city was still under threat, and marched as quickly as possible back to Athens. The Athenians arrived in time to prevent the Persians from securing a landing, and seeing that the opportunity was lost, the Persians turned about and returned to Asia. On the next day, the Spartan army arrived, having covered the 220 kilometres (136.7 mi) in only three days. The Spartans toured the battlefield at Marathon, and agreed that the Athenians had won a great victory.

Aftermath

Darius therefore began raising a huge new army with which he meant to completely subjugate Greece; however, in 486 BCE, his Egyptian

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt was an ancient civilization of Northeastern Africa, concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in what is now the modern country of Egypt. Egyptian civilization coalesced around 3150 BC with the political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaoh...

subjects revolted, indefinitely postponing any Greek expedition. Darius then died whilst preparing to march on Egypt, and the throne of Persia passed to his son Xerxes I. Xerxes crushed the Egyptian revolt, and very quickly re-started the preparations for the invasion of Greece. This expedition was finally ready by 480 BCE, and the second Persian invasion of Greece

Second Persian invasion of Greece

The second Persian invasion of Greece occurred during the Greco-Persian Wars, as King Xerxes I of Persia sought to conquer all of Greece. The invasion was a direct, if delayed, response to the defeat of the first Persian invasion of Greece at the Battle of Marathon which ended Darius I's attempts...

thereby began, under the command of Xerxes himself.

Significance

For the Persians, the two expeditions to Greece had been largely successful; new territories had been added to their empire and Eretria had been punished. It was only a minor setback that the invasion had met defeat at Marathon; that defeat barely dented the enormous resources of the Persian empire. Yet, for the Greeks, it was an enormously significant victory. It was the first time that Greeks had beaten the Persians, and showed them that the Persians were not invincible, and that resistance, rather than subjugation, was possible.The victory at Marathon was a defining moment for the young Athenian democracy, showing what might be achieved through unity and self-belief; indeed, the battle effectively marks the start of a 'golden age' for Athens. This was also applicable to Greece as a whole; "their victory endowed the Greeks with a faith in their destiny that was to endure for three centuries, during which western culture was born". John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill was a British philosopher, economist and civil servant. An influential contributor to social theory, political theory, and political economy, his conception of liberty justified the freedom of the individual in opposition to unlimited state control. He was a proponent of...

's famous opinion was that "the Battle of Marathon, even as an event in British history, is more important than the Battle of Hastings

Battle of Hastings

The Battle of Hastings occurred on 14 October 1066 during the Norman conquest of England, between the Norman-French army of Duke William II of Normandy and the English army under King Harold II...

".

Militarily, a major lesson for the Greeks was the potential of the hoplite phalanx. This style had developed during internecine warfare amongst the Greeks; since each city-state fought in the same way, the advantages and disadvantages of the hoplite phalanx had not been obvious. Marathon was the first time a phalanx faced more lightly armed troops, and revealed how devastating the hoplites could be in battle. The phalanx formation was still vulnerable to cavalry (the cause of much caution by the Greek forces at the Battle of Plataea

Battle of Plataea

The Battle of Plataea was the final land battle during the second Persian invasion of Greece. It took place in 479 BC near the city of Plataea in Boeotia, and was fought between an alliance of the Greek city-states, including Sparta, Athens, Corinth and Megara, and the Persian Empire of Xerxes...

), but used in the right circumstances, it was now shown to be a potentially devastating weapon. The Persians seem to have more-or-less disregarded the military lessons of Marathon. The composition of infantry for the second invasion seems to have been the same as during the first, despite the availability of hoplites and other heavy infantry in Persian-ruled lands. Having won battles against hoplites previously, the Persians may simply have regarded Marathon as an aberration.

Ancient sources

- HerodotusHerodotusHerodotus was an ancient Greek historian who was born in Halicarnassus, Caria and lived in the 5th century BC . He has been called the "Father of History", and was the first historian known to collect his materials systematically, test their accuracy to a certain extent and arrange them in a...

, The Histories - ThucydidesThucydidesThucydides was a Greek historian and author from Alimos. His History of the Peloponnesian War recounts the 5th century BC war between Sparta and Athens to the year 411 BC...

, History of The Peloponnesian Wars - Diodorus SiculusDiodorus SiculusDiodorus Siculus was a Greek historian who flourished between 60 and 30 BC. According to Diodorus' own work, he was born at Agyrium in Sicily . With one exception, antiquity affords no further information about Diodorus' life and doings beyond what is to be found in his own work, Bibliotheca...

, Library - LysiasLysiasLysias was a logographer in Ancient Greece. He was one of the ten Attic orators included in the "Alexandrian Canon" compiled by Aristophanes of Byzantium and Aristarchus of Samothrace in the third century BC.-Life:According to Dionysius of Halicarnassus and the author of the life ascribed to...

, Funeral Oration - PlatoPlatoPlato , was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Along with his mentor, Socrates, and his student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the...

, Menexenus - XenophonXenophonXenophon , son of Gryllus, of the deme Erchia of Athens, also known as Xenophon of Athens, was a Greek historian, soldier, mercenary, philosopher and a contemporary and admirer of Socrates...

Anabasis - Cornelius NeposCornelius NeposCornelius Nepos was a Roman biographer. He was born at Hostilia, a village in Cisalpine Gaul not far from Verona. His Gallic origin is attested by Ausonius, and Pliny the Elder calls him Padi accola...

Lives of the Eminent Commanders (Miltiades) - PlutarchPlutarchPlutarch then named, on his becoming a Roman citizen, Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus , c. 46 – 120 AD, was a Greek historian, biographer, essayist, and Middle Platonist known primarily for his Parallel Lives and Moralia...

Parallel Lives (Aristides, Themistocles), On the Malice of Herodotus - PausaniasPausanias (geographer)Pausanias was a Greek traveler and geographer of the 2nd century AD, who lived in the times of Hadrian, Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius. He is famous for his Description of Greece , a lengthy work that describes ancient Greece from firsthand observations, and is a crucial link between classical...

, Description of Greece - Marcus Junianus JustinusJunianus JustinusJustin was a Latin historian who lived under the Roman Empire. His name is mentioned only in the title of his own history, and there it is in the genitive, which would be M. Juniani Justini no matter which nomen he bore.Of his personal history nothing is known...

Epitome of the Phillipic History of Pompeius Trogus - Photius, Bibliotheca or Myriobiblon: Epitome of Persica by CtesiasCtesiasCtesias of Cnidus was a Greek physician and historian from Cnidus in Caria. Ctesias, who lived in the 5th century BC, was physician to Artaxerxes Mnemon, whom he accompanied in 401 BC on his expedition against his brother Cyrus the Younger....