Second Persian invasion of Greece

Encyclopedia

The second Persian

invasion of Greece

(480–479 BC) occurred during the Greco-Persian Wars

, as King Xerxes I of Persia sought to conquer all of Greece. The invasion was a direct, if delayed, response to the defeat of the first Persian invasion of Greece

(492–490 BC) at the Battle of Marathon

which ended Darius I's attempts to subjugate Greece. After Darius's death, his son Xerxes spent several years planning for the second invasion, mustering an enormous army and navy. The Athenians

and Sparta

ns led the Greek resistance, with some 70 city-states joining the 'Allied' effort. However, most of the Greek cities remained neutral or submitted to Xerxes.

The invasion began in spring 480 BC, when the Persian army crossed the Hellespont and marched through Thrace

and Macedon

to Thessaly

. The Persian advance was blocked at the pass of Thermopylae

by a small Allied force under King Leonidas I

of Sparta; simultaneously, the Persian fleet was blocked by an Allied fleet at the straits of Artemisium

. At the famous Battle of Thermopylae

, the Allied army held back the Persian army for seven days, before they were outflanked by a mountain path and the Allied rearguard was trapped in the pass and annihilated. The Allied fleet had also withstood two days of Persian attacks at the Battle of Artemisium

, but when news reached them of the disaster at Thermopylae, they withdrew to Salamis

.

After Thermopylae, all of Boeotia

and Attica

fell to the Persian army, who captured and burnt Athens

. However, a larger Allied army fortified the narrow Isthmus of Corinth

, protecting the Peloponnesus from Persian conquest. Both sides thus sought out a naval victory which might decisively alter the course of the war. The Athenian general Themistocles

succeeded in luring the Persian navy into the narrow Straits of Salamis, where the huge number of Persian ships became disorganised, and were soundly beaten by the Allied fleet. The Allied victory at Salamis prevented a quick conclusion to the invasion, and fearing becoming trapped in Europe, Xerxes retreated to Asia leaving his general Mardonius

to finish the conquest with the elite of the army.

The following Spring, the Allies assembled the largest ever hoplite

army, and marched north from the isthmus to confront Mardonius. At the ensuing Battle of Plataea

, the Greek infantry again proved its superiority, inflicting a severe defeat on the Persians, killing Mardonius in the process. On the same day, across the Aegean Sea

an Allied navy destroyed the remnants of the Persian navy at the Battle of Mycale

. With this double defeat, the invasion was ended, and Persian power in the Aegean severely dented. The Greeks would now move over to the offensive, eventually expelling the Persians from Europe, the Aegean islands and Ionia before the war finally came to an end in 479 BC.

. Herodotus, who has been called the 'Father of History', was born in 484 BC in Halicarnassus, Asia Minor (then under Persian overlordship). He wrote his 'Enquiries' (Greek—Historia; English—(The) Histories

) around 440–430 BC, trying to trace the origins of the Greco-Persian Wars, which would still have been relatively recent history (the wars finally ending in 450 BC). Herodotus's approach was entirely novel, and at least in Western society, he does seem to have invented 'history' as we know it. As Holland has it: "For the first time, a chronicler set himself to trace the origins of a conflict not to a past so remote so as to be utterly fabulous, nor to the whims and wishes of some god, nor to a people's claim to manifest destiny, but rather explanations he could verify personally."

Some subsequent ancient historians, despite following in his footsteps, criticised Herodotus, starting with Thucydides

. Nevertheless, Thucydides chose to begin his history where Herodotus left off (at the Siege of Sestos), and therefore evidently felt that Herodotus's history was accurate enough not to need re-writing or correcting. Plutarch

criticised Herodotus in his essay "On The Malignity of Herodotus", describing Herodotus as "Philobarbaros" (barbarian-lover), for not being pro-Greek enough, which suggests that Herodotus might actually have done a reasonable job of being even-handed. A negative view of Herodotus was passed on to Renaissance Europe, though he remained well read. However, since the 19th century his reputation has been dramatically rehabilitated by archaeological finds which have repeatedly confirmed his version of events. The prevailing modern view is that Herodotus generally did a remarkable job in his Historia, but that some of his specific details (particularly troop numbers and dates) should be viewed with skepticism. Nevertheless, there are still some historians who believe Herodotus made up much of his story.

The Sicilian historian Diodorus Siculus

, writing in the 1st century BC in his Bibliotheca Historica

, also provides an account of the Greco-Persian wars, partially derived from the earlier Greek historian Ephorus

. This account is fairly consistent with Herodotus's. The Greco-Persian wars are also described in less detail by a number of other ancient historians including Plutarch, Ctesias

, and are alluded by other authors, such as the playwright Aeschylus

. Archaeological evidence, such as the Serpent Column

, also supports some of Herodotus's specific claims.

had supported the unsuccessful Ionian Revolt

against the Persian Empire of Darius I in 499–494 BC. The Persian Empire was still relatively young, and prone to revolts amongst its subject peoples. Moreover, Darius was a usurper, and had spent considerable time extinguishing revolts against his rule. The Ionian revolt threatened the integrity of his empire, and Darius thus vowed to punish those involved (especially those not already part of the empire). Darius also saw the opportunity to expand his empire into the fractious world of Ancient Greece. A preliminary expedition under Mardonius, in 492 BC, to secure the land approaches to Greece ended with the re-conquest of Thrace

and forced Macedon

to become a client kingdom of Persia.

In 491 BC, Darius sent emissaries to all the Greek city-states, asking for a gift of 'earth and water' in token of their submission to him. Having had a demonstration of his power the previous year, the majority of Greek cities duly obliged. In Athens, however, the ambassadors were put on trial and then executed; in Sparta, they were simply thrown down a well. This meant that Sparta was also now effectively at war with Persia.

In 491 BC, Darius sent emissaries to all the Greek city-states, asking for a gift of 'earth and water' in token of their submission to him. Having had a demonstration of his power the previous year, the majority of Greek cities duly obliged. In Athens, however, the ambassadors were put on trial and then executed; in Sparta, they were simply thrown down a well. This meant that Sparta was also now effectively at war with Persia.

Darius thus put together an amphibious task force under Datis

and Artaphernes

in 490 BC, which attacked Naxos, before receiving the submission of the other Cycladic Islands

. The task force then moved on Eretria, which it besieged and destroyed. Finally, it moved to attack Athens, landing at the bay of Marathon

, where it was met by a heavily outnumbered Athenian army. At the ensuing Battle of Marathon, the Athenians won a remarkable victory, which resulted in the withdrawal of the Persian army to Asia.

Darius therefore began raising a huge new army with which he meant to completely subjugate Greece; however, in 486 BC, his Egyptian

subjects revolted, indefinitely postponing any Greek expedition. Darius then died whilst preparing to march on Egypt, and the throne of Persia passed to his son Xerxes I. Xerxes crushed the Egyptian revolt, and very quickly re-started the preparations for the invasion of Greece.

(rounding which headland, a Persian fleet had been destroyed in 492 BC). These were both feats of exceptional ambition, which would have been beyond any contemporary state. However, the campaign was delayed one year because of another revolt in Egypt and Babylonia

.

In 481 BC

, after roughly four years of preparation, Xerxes began to muster the troops for the invasion of Europe. Herodotus gives the names of 46 nations from which troops were drafted. The Persian army was gathered in Asia Minor

in the summer and autumn of 481 BC

. The armies from the Eastern satrapies was gathered in Kritala, Cappadocia

and were led by Xerxes to Sardis

where they passed the winter. Early in spring it moved to Abydos

where it was joined with the armies of the western satrapies. Then the army which Xerxes had mustered marched towards Europe, crossing the Hellespont on two pontoon bridge

s.

, who was a near-contemporary, talks of four million; Ctesias

gave 800,000 as the total number of the army that was assembled by Xerxes. Whilst it has been suggested that Herodotus or his sources had access to official Persian Empire records of the forces involved in the expedition, modern scholars tend to reject these figures based on knowledge of the Persian military systems, their logistical capabilities, the Greek countryside, and supplies available along the army's route.

Modern scholars thus generally attribute the numbers given in the ancient sources to the result of miscalculations or exaggerations on the part of the victors, or disinformation by the Persians in the run up to the war. The topic has been hotly debated but the modern consensus revolves around the figure of 200–250,000. Nevertheless, whatever the real numbers were, it is clear that Xerxes was anxious to ensure a successful expedition by mustering overwhelming numerical superiority by land and by sea, and also that much of the army died of starvation and disease, never returning to Asia.

Herodotus tells us that the army and navy, whilst moving through Thrace, was halted at Doriskos

for an inspection by Xerxes, and he recounts the numbers of troops found to be present:

Herodotus doubles this number to account for support personnel and thus he reports that the whole army numbered 5,283,220 men. Other ancient sources give similarly large numbers. The poet Simonides

, who was a near-contemporary, talks of four million; Ctesias

gave 800,000 as the total number of the army that assembled in Doriskos.

An early and very influential modern historian, George Grote

, set the tone by expressing incredulity at the numbers given by Herodotus: "To admit this overwhelming total, or anything near to it, is obviously impossible." Grote's main objection is the supply problem, though he does not analyse the problem in detail. He did not reject Herodotus's account altogether, citing the latter's reporting of the Persians' careful methods of accounting and their stockpiling of supply caches for three years, but drew attention to the contradictions in the ancient sources. A major limiting factor for the size of the Persian army, first suggested by Sir Frederick Maurice (a British transport officer) is the supply of water. Maurice suggested in the region of 200,000 men and 70,000 animals could have been supported by the rivers in that region of Greece. He further suggested that Herodotus may have confused the Persian terms for chiliarchy (1,000) and myriarchy (10,000), leading to an exaggeration by a factor of ten. Other early modern scholars estimated that the land forces participating in the invasion at 100,000 soldiers or less, based on the logistical systems available to the Ancients.

Munro and Macan

note Herodotus giving the names of six major commanders and 29 myriarchs (leaders of a baivabaram, the basic unit of the Persian infantry, which numbered about 10,000-strong); this would give a land force of roughly 300,000 men. Other proponents of larger numbers suggest figures from 250,000 to 700,000 One historian, Kampouris, even accepts as realistic Herodotus' 1,700,000 for the infantry plus 80,000 cavalry (including support) for various reasons including the size of the area from which the army was drafted (from modern-day Libya

to Pakistan

), the ratios of land troops to fleet troops, of infantry to cavalry and Persian troops to Greek troops.

Herodotus also records that this was the number at the Battle of Salamis, despite the losses earlier in storms off Sepia and Euboea, and at the battle of Artemisium. He claims that the losses where replenished with reinforcements, though he only records 120 triremes from the Greeks of Thrace and an unspecified number of ships from the Greek islands. Aeschylus

, who fought at Salamis, also claims that he faced there 1,207 warships, of which 1,000 were triremes and 207 fast ships. Diodorus

and Lysias

independently claim there were 1,200 at Doriskos. The number of 1,207 (for the outset only) is also given by Ephorus

, while his teacher Isocrates

claims there were 1,300 at Doriskos and 1,200 at Salamis. Ctesias gives another number, 1,000 ships, while Plato

, speaking in general terms refers to 1,000 ships and more.

These numbers are (by ancient standards) consistent, and this could be interpreted that a number around 1,200 is correct. Among modern scholars some have accepted this number, although suggesting that the number must have been lower by the Battle of Salamis. Other recent works on the Persian Wars reject this number, 1,207 being seen as more of a reference to the combined Greek fleet in the Iliad

generally claim that the Persians could have launched no more than around 600 warships into the Aegean.

in late autumn of 481 BC, and a confederate alliance of Greek city-states

was formed. This confederation had the power to send envoys asking for assistance and to dispatch troops from the member states to defensive points after joint consultation. Herodotus does not formulate an abstract name for the union but simply calls them "" (the Greeks) and "the Greeks who had sworn alliance" (Godley translation) or "the Greeks who had banded themselves together" (Rawlinson translation). Hereafter, they will be referred to as the 'Allies'. Sparta and Athens had a leading role in the congress but interests of all the states played a part in determining defensive strategy. Little is known about the internal workings of the congress or the discussions during its meetings. Only 70 of the approximately 700 Greek cities sent representatives. Nevertheless, this was remarkable for the disjointed Greek world, especially since many of the city-states in attendance were still technically at war with each other.

The majority of other city-states remained more-or-less neutral, awaiting the outcome of the confrontation. Thebes was a major absentee, and was suspected of being willing to aid the Persians once the invasion force arrived. Not all Thebans agreed with this policy, and 400 "loyalist" hoplites joined the Allied force at Thermopylae (at least according to one possible interpretation). The most notable city which actively sided with the Persians ("Medised") was Argos

, in the otherwise Spartan-dominated Peloponnese. However, the Argives had been severely weakened in 494 BC, when a Spartan-force led by Cleomenes I

had annihilated the Argive army in Battle of Sepeia

and then massacred the fugitives.

, at Doriskos at the Evros river estuary where the Asian army was linked up with the Balkan allies, at Eion

on the Strymon river and at Therme, modern-day Thessaloniki

. There, food had been sent from Asia for several years in preparation for the campaign. Animals had been bought and fattened, while the local populations had, for several months, been ordered to grind the grains into flour. The Persian army took roughly 3 months to travel unopposed from the Hellespont to Therme, a journey of about 360 miles (600 km). It paused at Doriskos where it was joined by the fleet. Xerxes reorganized the troops into tactical units replacing the national formations used earlier for the march.

The Allied 'congress' met again in the spring of 480 BC. A Thessalian delegation suggested that the allies could muster in the narrow Vale of Tempe

, on the borders of Thessaly, and thereby block Xerxes's advance. A force of 10,000 Allies led by the Spartan polemarch

Euenetus and Themistocles was thus despatched to the pass. However, once there, they were warned by Alexander I of Macedon

that the vale could be bypassed by at least two other passes, and that the army of Xerxes was overwhelming; the Allies therefore retreated. Shortly afterwards, they received the news that Xerxes had crossed the Hellespont. The abandonment of Tempe meant that all of Thessaly submitted to the Persians, as did many cities to the north of the pass of Thermopylae when it seemed help was not forthcoming.

A second strategy was therefore suggested to the Allies by Themistocles. The route to southern Greece (Boeotia, Attica and the Peloponnesus) would require the army of Xerxes to travel through the very narrow pass of Thermopylae

. This could easily be blocked by the Allies, despite the overwhelming number of Persians. Furthermore, to prevent the Persians bypassing Thermopylae by sea, the allied navy could block the straits of Artemisium. This dual strategy was adopted by the congress. However, the Peloponnesian cities made fall-back plans to defend the Isthmus of Corinth should it come to it, whilst the women and children of Athens were evacuated en masse to the Peloponnesian city of Troezen

.

, and thus intending to march towards Thermopylae, it was both the period of truce which accompanied the Olympic games, and the Spartan festival of Carneia, during both of which warfare was considered sacrilegious. Nevertheless, the Spartans considered the threat so grave that they despatched their king Leonidas I

with his personal bodyguard (the Hippeis) of 300 men (in this case, the elite young soldiers in the Hippeis were replaced by veterans who already had children). Leonidas was supported by contingents from the Peloponnesian cities allied to Sparta, and other forces which were picked up en route to Thermopylae. The Allies proceeded to occupy the pass, rebuilt the wall the Phocians had built at the narrowest point of the pass, and waited for Xerxes's arrival.

When the Persians arrived at Thermopylae in mid-August, they initially waited for three days for the Allies to disperse. When Xerxes was eventually persuaded that the Allies intended to contest the pass, he sent his troops to attack. However, the Greek position was ideally suited to hoplite

When the Persians arrived at Thermopylae in mid-August, they initially waited for three days for the Allies to disperse. When Xerxes was eventually persuaded that the Allies intended to contest the pass, he sent his troops to attack. However, the Greek position was ideally suited to hoplite

warfare, the Persian contingents being forced to attack the phalanx

head on. The Allies thus withstood two full days of battle and everything Xerxes could throw at them. However, at the end of the second day, they were betrayed by a local resident named Ephialtes who revealed a mountain path that led behind the Allied lines to Xerxes. Xerxes then sent his elite guards, the Immortals on a night march to outflank the Allied. When he was made aware of this manoeuver (whilst the Immortals were still en route), Leonidas dismissed the bulk of the Allied army, remaining to guard the rear with 300 Spartans, 700 Thespians, 400 Thebans and perhaps a few hundred others. On the third day of the battle, the remaining Allies sallied forth from the wall to meet the Persians and slaughter as many as they could. Ultimately, however, the Allied rearguard was annihilated, and the pass of Thermopylae opened to the Persians.

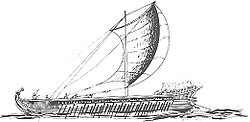

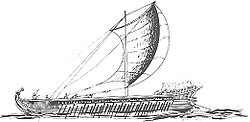

Simultaneous with the battle at Thermopylae, an Allied naval force of 271 triremes defended the Straits of Artemisium against the Persians. Directly before Artemisium, the Persian fleet had been caught in a gale off the coast of Magnesia

, losing many ships, but could still probably muster over 800 ships at the start of the battle. On the first day (also the first of the Battle of Thermopylae), the Persians detached 200 seaworthy ships, which were sent to sail around the eastern coast of Euboea

. These ships were to round Euboea and block the line of retreat for the Allied fleet. Meanwhile, the Allies and the remaining Persians engaged in the late afternoon, the Allies having the better of the engagement and capturing 30 vessels. That evening, another storm occurred, wrecking the majority of the Persian detachment which had been sent around Euboea.

On the second day of the battle, news reached the Allies that their lines of retreat were no longer threatened; they therefore resolved to maintain their position. They staged a hit-and-run attack on some Cilicia

On the second day of the battle, news reached the Allies that their lines of retreat were no longer threatened; they therefore resolved to maintain their position. They staged a hit-and-run attack on some Cilicia

n ships, capturing and destroying them. On the third day, however, the Persian fleet attacked the Allies lines in full force. In a day of savage fighting, the Allies held on to their position, but suffered severe losses (half the Athenian fleet was damaged); nevertheless, the Allies inflicted equal losses on the Persian fleet. That evening, the Allies received news of the fate of Leonidas and the Allies at Thermopylae. Since the Allied fleet was badly damaged, and since it no longer needed to defend the flank of Thermopylae, they retreated from Artemisium to the island of Salamis

.

and Plataea

, were captured and razed. Attica was also left open to invasion, and the remaining population of Athens was thus evacuated, with the aid of the Allied fleet, to Salamis. The Peloponnesian Allies began to prepare a defensive line across the Isthmus of Corinth, building a wall, and demolishing the road from Megara

, thereby abandoning Athens to the Persians. Athens thus fell; the small number of Athenians who had barricaded themselves on the Acropolis

were eventually defeated, and Xerxes then ordered Athens to be torched.

The Persians had now captured most of Greece, but Xerxes had perhaps not expected such defiance from the Greeks; his priority was now to complete the war as quickly as possible; the huge invasion force could not be supplied indefinitely, and probably Xerxes did not wish to be at the fringe of his empire for so long. Thermopylae had shown that a frontal assault against a well defended Greek position had little chance of success; with the Allies now dug in across the isthmus, there was therefore little chance of the Persians conquering the rest of Greece by land. However, if the isthmus's defensive line could be outflanked, the Allies could be defeated. Such an outflanking of the isthmus required the use of the Persian navy, and thus the neutralisation of the Allied navy. In summary, if Xerxes could destroy the Allied navy, he would be in a strong position to force a Greek surrender; this seemed the only hope of concluding the campaign in that season. Conversely by avoiding destruction, or as Themistocles hoped, by destroying the Persian fleet, the Greeks could avoid conquest. In the final reckoning, both sides were prepared to stake everything on a naval battle, in the hope of decisively altering the course of the war.

Thus it was that the Allied fleet remained off the coast of Salamis into September, despite the imminent arrival of the Persians. Even after Athens fell to the advancing Persian army, the Allied fleet still remained off the coast of Salamis, trying to lure the Persian fleet to battle. Partly as a result of subterfuge on the part of Themistocles, the navies finally engaged in the cramped Straits of Salamis. There, the large Persian numbers were an active hindrance, as ships struggled to manoeuvre and became disorganised. Seizing the opportunity, the Greek fleet attacked, and scored a decisive victory, sinking or capturing at least 200 Persian ships, and thus ensuring the Peloponnessus would not be outflanked.

Thus it was that the Allied fleet remained off the coast of Salamis into September, despite the imminent arrival of the Persians. Even after Athens fell to the advancing Persian army, the Allied fleet still remained off the coast of Salamis, trying to lure the Persian fleet to battle. Partly as a result of subterfuge on the part of Themistocles, the navies finally engaged in the cramped Straits of Salamis. There, the large Persian numbers were an active hindrance, as ships struggled to manoeuvre and became disorganised. Seizing the opportunity, the Greek fleet attacked, and scored a decisive victory, sinking or capturing at least 200 Persian ships, and thus ensuring the Peloponnessus would not be outflanked.

According to Herodotus, after this loss Xerxes attempted to build a causeway across the straits to attack Salamis (although Strabo

and Ctesias place this attempt before the battle). In any case this project was soon abandoned. With the Persians' naval superiority removed, Xerxes feared that the Greeks might sail to the Hellespont and destroy the pontoon bridges. According to Herodotus, Mardonius volunteered to remain in Greece and complete the conquest with a hand-picked group of troops, whilst advising Xerxes to retreat to Asia with the bulk of the army. All of the Persian forces abandoned Attica, with Mardonius over-wintering in Boeotia and Thessaly. The Athenians were thus able to return to their burnt-out city for the winter.

,

, which was also in revolt. The town was held by the Bottiaean tribe, who had been driven out of Macedon

. Having taken the town, he massacred the defenders, and handed over the town to the Chalcidian people.

, whilst the remnants of the Persian fleet skulked off Samos

, both sides unwilling to risk battle. Similarly, Mardonius remained in Thessaly, knowing an attack on the isthmus was pointless, whilst the Allies refused to send an army outside the Peloponessus.

Mardonius moved to break the stalemate, by offering peace, self-government and territorial expansion to the Athenians (with the aim of thereby removing their fleet from the Allied forces), using Alexander I of Macedon as intermediate. The Athenians made sure that a Spartan delegation was on hand to hear the offer, but rejected it. Athens was thus evacuated again, and the Persians marched south and re-took possession of it. Mardonius now repeated his offer of peace to the Athenian refugees on Salamis. Athens, along with Megara and Plataea, sent emissaries to Sparta demanding assistance, and threatening to accept the Persian terms if not. The Spartans, who were at that time celebrating the festival of Hyacinth

us, delayed making a decision for 10 days. However, when the Athenian emissaries then delivered an ultimatum to the Spartans, they were amazed to hear that a task force was in fact already marching to meet the Persians.

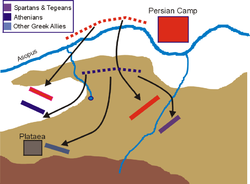

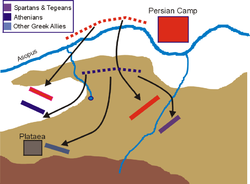

When Mardonius heard that the Allied army was on the march, he retreated into Boeotia, near Plataea, trying to draw the Allies into open terrain where he could use his cavalry. The Allied army however, under the command of the Spartan regent Pausanias

When Mardonius heard that the Allied army was on the march, he retreated into Boeotia, near Plataea, trying to draw the Allies into open terrain where he could use his cavalry. The Allied army however, under the command of the Spartan regent Pausanias

, stayed on high ground above Plataea to protect themselves against such tactics. Mardonius ordered a hit-and-run cavalry attack on the Greek lines, but the attack was unsuccessful and the cavalry commander killed. The outcome prompted the Allies to move to a position nearer the Persian camp, still on high ground. As a result the Allied lines of communication were exposed. The Persian cavalry began to intercept food deliveries and finally managed to destroy the only spring of water available to the Allies. The Allied position now undermined, Pausanias ordered a night-time retreat towards their original positions. This went awry, leaving the Athenians, and Spartans and Tegeans isolated on separate hills, with the other contingents scattered further away, near Plataea itself. Seeing that he might never have a better opportunity to attack, Mardonius ordered his whole army forward. However as at Thermopylae, the Persian infantry proved no match for the heavily armoured Greek hoplites, and the Spartans broke through to Mardonius's bodyguard and killed him. The Persian force thus dissolved in rout; 40,000 troops managed to escape via the road to Thessaly, but the rest fled to the Persian camp where they were trapped and slaughtered by the Allies, thus finalising their victory.

On the afternoon of the Battle of Plataea, Herodotus tells us that rumour of the Allied victory reached the Allied navy, at that time off the coast of Mount Mycale

in Ionia

. Their morale boosted, the Allied marines fought and won a decisive victory at the Battle of Mycale that same day, destroying the remnants of the Persian fleet. As soon as the Peloponnesians had marched north of the isthmus, the Athenian fleet under Xanthippus

had joined up with the rest of the Allied fleet. The fleet, now able to match the Persians, had first sailed to Samos, where the Persian fleet was based. The Persians, whose ships were in a poor state of repair, had decided not to risk fighting, and instead drew their ships up on the beach under Mycale. An army of 60,000 men had been left there by Xerxes, and the fleet joined with them, building a pallisade around the camp to protect the ships. However, Leotychides decided to attack the camp with the Allied fleet's marines. Seeing the small size of the Allied force, the Persians emerged from the camp, but the hoplites again proved superior, and destroyed much of the Persian force. The ships were abandoned to the Allies, who burnt them, crippling Xerxes' sea power, and marking the ascendancy of the Allied fleet.

With the twin victories of Plataea and Mycale, the second Persian invasion of Greece was over. Moreover, the threat of future invasion was abated; although the Greeks remained worried that Xerxes would try again, over time it became apparent that the Persian desire to conquer Greece was much diminished.

With the twin victories of Plataea and Mycale, the second Persian invasion of Greece was over. Moreover, the threat of future invasion was abated; although the Greeks remained worried that Xerxes would try again, over time it became apparent that the Persian desire to conquer Greece was much diminished.

In many ways Mycale represents the start of a new phase of the conflict, the Greek counterattack. After the victory at Mycale, the Allied fleet sailed to the Hellespont to break down the pontoon bridges, but found that this was already done. The Peloponnesians sailed home, but the Athenians remained to attack the Chersonesos

, still held by the Persians. The Persians in the region, and their allies made for Sestos

, the strongest town in the region, which the Athenians then laid siege to; after a protracted siege, it fell to the Athenians. Herodotus ended his Historia after the Siege of Sestos. Over the next 30 years, the Greeks, primarily the Athenian-dominated Delian League

, would expel the Persians from Macedon, Thrace, the Aegean islands and Ionia. Peace with Persia came in 449 BC with the Peace of Callias, finally ending the half-century of warfare.

, members of the middle-classes (the zeugites) who could afford the armour necessary to fight in this manner. The hoplite was, by the standards of the time, heavily armoured, with a breastplate (originally bronze, but probably by this stage a more flexible leather version), greaves, a full helmet, and a large round shield (the aspis). Hoplites were armed with a long spear (the doru), which was evidently significantly longer than Persian spears, and a sword (the xiphoi). Hoplites fought in the phalanx formation; the exact details are not completely clear, but it was a close-knit formation, presenting a uniform front of overlapping shields, and spears, to the enemy. Properly assembled, the phalanx was a formidable offensive and defensive weapon; on occasions when it is recorded to have happened, it took a huge number of light infantry to defeat a relatively small phalanx. The phalanx was vulnerable to being outflanked by cavalry, if caught on the wrong terrain, however. The hoplite's heavy armour and long spears made them excellent troops in hand-to-hand combat and gave them significant protection against ranged attacks by light troops and skirmishers. Even if the shield did not stop a missile, there was a reasonable chance the armour would.

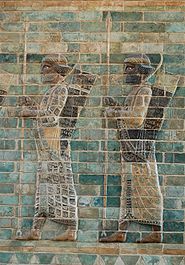

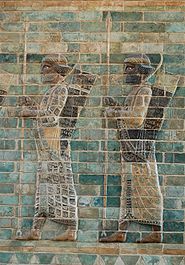

The Persian infantry used in the invasion were a heterogeneous group drawn from across the empire. However, according to Herodotus, there was at least a general conformity in the type of armour and style of fighting. The troops were, generally speaking, armed with a bow, 'short spear' and sword, carried a wicker shield, and wore at most a leather jerkin. The one exception to this may have been the ethnic Persian troops, who may have worn a corslet of scaled armour. Some of contingents may have been armed somewhat differently; for instance, the Saka

The Persian infantry used in the invasion were a heterogeneous group drawn from across the empire. However, according to Herodotus, there was at least a general conformity in the type of armour and style of fighting. The troops were, generally speaking, armed with a bow, 'short spear' and sword, carried a wicker shield, and wore at most a leather jerkin. The one exception to this may have been the ethnic Persian troops, who may have worn a corslet of scaled armour. Some of contingents may have been armed somewhat differently; for instance, the Saka

were renowned axemen. The 'elite' contingents of the Persian infantry seem to have been the ethnic Persians, Medians

, Cissians and the Saka. The foremost of the infantry were the royal guards, the Immortals

, although they were still armed in the aforementioned style. Cavalry was provided by the Persians, Bactria

ns, Medes, Cissians and Saka; most of these probably fought as lightly armed missile cavalry. The style of fighting used by the Persians was probably to stand off from an enemy, using their bows (or equivalent) to wear down the enemy before closing in to deliver the coup de grace with spear and sword.

The Persians had encountered hoplites in battle before at Ephesus, where their cavalry had easily routed the (probably exhausted) Greeks. However, at the battle of Marathon, the Athenian hoplites had shown their superiority over the Persian infantry, albeit in the absence of any cavalry. It is therefore slightly surprising that the Persians did not bring any hoplites from the Greek regions, especially Ionia, under their control in Asia. Equally, Herodotus tells us that the Egyptian marines serving in the navy were well armed, and performed well against the Greek marines; yet no Egyptian contingent served in the army. The Persians may not have completely trusted the Ionians and Egyptians, since both had recently revolted against Persian rule. However, if this is the case, then it must be questioned why there were Greek and Egyptian contingents in the navy. The Allies evidently tried to play on the Persian fears about the reliability of the Ionians in Persian service; but, as far as we can tell, both the Ionians and Egyptians performed particularly well for the Persian navy. It may therefore simply be that neither the Ionians nor Egyptians were included in the army because they were serving in the fleet — none of the coastal regions of the Persian empire appear to have sent contingents with the army.

The Persians had encountered hoplites in battle before at Ephesus, where their cavalry had easily routed the (probably exhausted) Greeks. However, at the battle of Marathon, the Athenian hoplites had shown their superiority over the Persian infantry, albeit in the absence of any cavalry. It is therefore slightly surprising that the Persians did not bring any hoplites from the Greek regions, especially Ionia, under their control in Asia. Equally, Herodotus tells us that the Egyptian marines serving in the navy were well armed, and performed well against the Greek marines; yet no Egyptian contingent served in the army. The Persians may not have completely trusted the Ionians and Egyptians, since both had recently revolted against Persian rule. However, if this is the case, then it must be questioned why there were Greek and Egyptian contingents in the navy. The Allies evidently tried to play on the Persian fears about the reliability of the Ionians in Persian service; but, as far as we can tell, both the Ionians and Egyptians performed particularly well for the Persian navy. It may therefore simply be that neither the Ionians nor Egyptians were included in the army because they were serving in the fleet — none of the coastal regions of the Persian empire appear to have sent contingents with the army.

In the two major land battles of the invasion, the Allies clearly adjusted their tactics to nullify the Persian advantage in numbers and cavalry, by occupying the pass at Thermopyale, and by staying on high ground at Plataea. At the Thermopylae, until the path outflanking the Allied position was revealed, the Persians signally failed to adjust their tactics to the situation, although the position was well chosen to limit the Persian options. At Plataea, the harassing of the Allied positions by cavalry was a successful tactic, forcing the precipitous (and nearly disastrous) retreat; however, Mardonius then brought about a general melee between the infantry which resulted in the Persian defeat. The events at Mycale reveal a similar story; Persian infantry committing themselves to a melee with hoplites, with disastrous results. It has been suggested that there is little evidence of complex tactics in the Greco-Persian wars. However, as simple as the Greek tactics were, they played to their strengths; the Persians however, may have seriously underestimated the strength of the hoplite, and their failure to adapt to facing the Allied infantry contributed to the eventual Persian defeat.

The Persian strategy for 480 BC was probably to simply progress through Greece in overwhelming force. The cities in any territory that the army passed through would be forced to submit or risk destruction; and indeed this happened with the Thessalian, Locrian and Phocian cities who initially resisted the Persians but then were forced to submit as the Persians advanced. Conversely, the Allied strategy was probably to try and stop the Persian advance as far north as possible, and thus prevent the submission of as many potential Allies as possible. Beyond this, the Allies seem to have realised that given the Persians' overwhelming numbers, they had little chance in open battle, and thus they opted to try and defend geographical bottle-necks, where the Persian numbers would count for less. The whole Allied campaign for 480 BC can be seen in this context. Initially they attempted to defend the Tempe pass to prevent the loss of Thessaly. After they realised that they could not defend this position, they chose the next-most northerly position, the Thermopylae/Artemisium axis. The Allied performance at Thermopylae was initially effective; however, the failure to properly guard the path that outflanked Thermopylae undermined their strategy, and led to defeat. At Artemisium the fleet also scored some successes, but withdrew due to the losses they had sustained, and since the defeat of Thermopylae made the position irrelevant. Thus far, the Persian strategy had succeeded, whilst the Allied strategy, though not a disaster, had failed.

The defence of the Isthmus of Corinth by the Allies changed the nature of the war. The Persians did not attempt to attack the isthmus by land, realising they probably could not breach it. This essentially reduced the conflict to a naval one. Themistocles now proposed what was in hindsight the strategic masterstroke in the Allied campaign; to lure the Persian fleet to battle in the straits of Salamis. However, as successful as this was, there was no need for the Persians to fight at Salamis to win the war; it has been suggested that the Persians were either over-confident, or over-eager to finish the campaign. Thus, the Allied victory at Salamis must at least partially be ascribed to a Persian strategic blunder. After Salamis, the Persian strategy changed. Mardonius sought to exploit dissensions between the Allies in order to fracture the alliance. In particular, he sought to win over the Athenians, which would leave the Allied fleet unable to oppose Persian landings on the Peloponnesus. Although Herodotus tells us that Mardonius was keen to fight a decisive battle, his actions in the run-up to Plataea are not particularly consistent with this. He seems to have been willing to accept battle on his terms, but he waited either for the Allies to attack, or for the alliance to collapse ignominiously. The Allied strategy for 479 BC was something of a mess; the Peloponnesians only agreed to march north in order to save the alliance, and it appears that the Allied leadership had little idea how to force a battle that they could win. It was the botched attempt to retreat from Plataea that finally delivered the Allies battle on their terms. Mardonius may have been over-eager for victory; there was no need to attack the Allies, and by doing so he played to the main Allied tactical strength, combat in the melee. The Allied victory at Plataea can also therefore be seen as partially the result of a Persian mistake.

Thus, the Persian failure may be seen partly as a result of two strategic mistakes which handed the Allies tactical advantages, and resulted in decisive defeats for the Persians. The Allied success is often seen as the result of "free men fighting for their freedom". This may have played a part, and certainly the Greeks seem to have interpreted their victory in those terms. One crucial factor in the Allied success was that, having formed an alliance, however fractious, they remained true to it, despite the odds. There appear to have been many occasions when the alliance seemed in doubt, but ultimately it withstood; and whilst this alone did not defeat the Persians, it meant that even after the occupation of most of Greece, the Allies were not themselves defeated. This is exemplified by the remarkable fact that the citizens of Athens, Thespiae and Plataea chose to carry on fighting from exile rather than submit to the Persians. Ultimately, the Allies succeeded because they avoided catastrophic defeats, stuck to their alliance, took advantage of Persian mistakes, and because in the hoplite they possessed an advantage (perhaps their only real advantage at the start of the conflict) which, at Plataea, allowed them to destroy the Persian invasion force.

The second Persian invasion of Greece was an event of major significance in European history. A large number of historians hold that, had Greece been conquered, the Ancient Greek culture which forms much of the basis of 'western civilization' would never have developed (and by extension western civilization per se). Whilst this may be an exaggeration (it is obviously impossible to know), it is clear that even at the time the Greeks understood that something very significant had happened.

The second Persian invasion of Greece was an event of major significance in European history. A large number of historians hold that, had Greece been conquered, the Ancient Greek culture which forms much of the basis of 'western civilization' would never have developed (and by extension western civilization per se). Whilst this may be an exaggeration (it is obviously impossible to know), it is clear that even at the time the Greeks understood that something very significant had happened.

Militarily, there was not much in the way of tactical or strategic innovation during the Persian invasion, one commentator suggesting it was something of "a soldier's war" (i.e. it was the soldiers rather than generals that won the war). Thermopylae is often used as a good example of the use of terrain as a force multiplier; whilst Themistocles's ruse before Salamis is a good example of the use of deception in warfare (one of Sun Tzu's 'extraordinary forces'). The major lesson of the invasion, reaffirming the events at the Battle of Marathon, was the superiority of the hoplite in close-quarters fighting over the more-lightly armed Persian infantry. Taking on this lesson the Persian empire would later, after the Peloponnesian War

, start recruiting and relying on Greek mercenaries.

Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire , sometimes known as First Persian Empire and/or Persian Empire, was founded in the 6th century BCE by Cyrus the Great who overthrew the Median confederation...

invasion of Greece

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

(480–479 BC) occurred during the Greco-Persian Wars

Greco-Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire of Persia and city-states of the Hellenic world that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of the Greeks and the enormous empire of the Persians began when Cyrus...

, as King Xerxes I of Persia sought to conquer all of Greece. The invasion was a direct, if delayed, response to the defeat of the first Persian invasion of Greece

First Persian invasion of Greece

The first Persian invasion of Greece, during the Persian Wars, began in 492 BCE, and ended with the decisive Athenian victory at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE. The invasion, consisting of two distinct campaigns, was ordered by the Persian king Darius I primarily in order to punish the...

(492–490 BC) at the Battle of Marathon

Battle of Marathon

The Battle of Marathon took place in 490 BC, during the first Persian invasion of Greece. It was fought between the citizens of Athens, aided by Plataea, and a Persian force commanded by Datis and Artaphernes. It was the culmination of the first attempt by Persia, under King Darius I, to subjugate...

which ended Darius I's attempts to subjugate Greece. After Darius's death, his son Xerxes spent several years planning for the second invasion, mustering an enormous army and navy. The Athenians

History of Athens

Athens is one of the oldest named cities in the world, having been continuously inhabited for at least 7000 years. Situated in southern Europe, Athens became the leading city of Ancient Greece in the first millennium BCE and its cultural achievements during the 5th century BCE laid the foundations...

and Sparta

Sparta

Sparta or Lacedaemon, was a prominent city-state in ancient Greece, situated on the banks of the River Eurotas in Laconia, in south-eastern Peloponnese. It emerged as a political entity around the 10th century BC, when the invading Dorians subjugated the local, non-Dorian population. From c...

ns led the Greek resistance, with some 70 city-states joining the 'Allied' effort. However, most of the Greek cities remained neutral or submitted to Xerxes.

The invasion began in spring 480 BC, when the Persian army crossed the Hellespont and marched through Thrace

Thrace

Thrace is a historical and geographic area in southeast Europe. As a geographical concept, Thrace designates a region bounded by the Balkan Mountains on the north, Rhodope Mountains and the Aegean Sea on the south, and by the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara on the east...

and Macedon

Macedon

Macedonia or Macedon was an ancient kingdom, centered in the northeastern part of the Greek peninsula, bordered by Epirus to the west, Paeonia to the north, the region of Thrace to the east and Thessaly to the south....

to Thessaly

Thessaly

Thessaly is a traditional geographical region and an administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, Thessaly was known as Aeolia, and appears thus in Homer's Odyssey....

. The Persian advance was blocked at the pass of Thermopylae

Thermopylae

Thermopylae is a location in Greece where a narrow coastal passage existed in antiquity. It derives its name from its hot sulphur springs. "Hot gates" is also "the place of hot springs and cavernous entrances to Hades"....

by a small Allied force under King Leonidas I

Leonidas I

Leonidas I was a hero-king of Sparta, the 17th of the Agiad line, one of the sons of King Anaxandridas II of Sparta, who was believed in mythology to be a descendant of Heracles, possessing much of the latter's strength and bravery...

of Sparta; simultaneously, the Persian fleet was blocked by an Allied fleet at the straits of Artemisium

Artemisium

Artemisium is a cape north of Euboea, Greece. The legendary hollow cast bronze statue of a debatable Zeus or Poseidon was found off this cape in a sunken ship.-See also:* Temple of Artemis...

. At the famous Battle of Thermopylae

Battle of Thermopylae

The Battle of Thermopylae was fought between an alliance of Greek city-states, led by King Leonidas of Sparta, and the Persian Empire of Xerxes I over the course of three days, during the second Persian invasion of Greece. It took place simultaneously with the naval battle at Artemisium, in August...

, the Allied army held back the Persian army for seven days, before they were outflanked by a mountain path and the Allied rearguard was trapped in the pass and annihilated. The Allied fleet had also withstood two days of Persian attacks at the Battle of Artemisium

Battle of Artemisium

The Battle of Artemisium was a series of naval engagements over three days during the second Persian invasion of Greece. The battle took place simultaneously with the more famous land battle at Thermopylae, in August or September 480 BC, off the coast of Euboea and was fought between an alliance of...

, but when news reached them of the disaster at Thermopylae, they withdrew to Salamis

Salamis Island

Salamis , is the largest Greek island in the Saronic Gulf, about 1 nautical mile off-coast from Piraeus and about 16 km west of Athens. The chief city, Salamina , lies in the west-facing core of the crescent on Salamis Bay, which opens into the Saronic Gulf...

.

After Thermopylae, all of Boeotia

Boeotia

Boeotia, also spelled Beotia and Bœotia , is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of Central Greece. It was also a region of ancient Greece. Its capital is Livadeia, the second largest city being Thebes.-Geography:...

and Attica

Attica

Attica is a historical region of Greece, containing Athens, the current capital of Greece. The historical region is centered on the Attic peninsula, which projects into the Aegean Sea...

fell to the Persian army, who captured and burnt Athens

Athens

Athens , is the capital and largest city of Greece. Athens dominates the Attica region and is one of the world's oldest cities, as its recorded history spans around 3,400 years. Classical Athens was a powerful city-state...

. However, a larger Allied army fortified the narrow Isthmus of Corinth

Isthmus of Corinth

The Isthmus of Corinth is the narrow land bridge which connects the Peloponnese peninsula with the rest of the mainland of Greece, near the city of Corinth. The word "isthmus" comes from the Ancient Greek word for "neck" and refers to the narrowness of the land. The Isthmus was known in the ancient...

, protecting the Peloponnesus from Persian conquest. Both sides thus sought out a naval victory which might decisively alter the course of the war. The Athenian general Themistocles

Themistocles

Themistocles ; c. 524–459 BC, was an Athenian politician and a general. He was one of a new breed of politicians who rose to prominence in the early years of the Athenian democracy, along with his great rival Aristides...

succeeded in luring the Persian navy into the narrow Straits of Salamis, where the huge number of Persian ships became disorganised, and were soundly beaten by the Allied fleet. The Allied victory at Salamis prevented a quick conclusion to the invasion, and fearing becoming trapped in Europe, Xerxes retreated to Asia leaving his general Mardonius

Mardonius

Mardonius was a leading Persian military commander during the Persian Wars with Greece in the early 5th century BC.-Early years:Mardonius was the son of Gobryas, a Persian nobleman who had assisted the Achaemenid prince Darius when he claimed the throne...

to finish the conquest with the elite of the army.

The following Spring, the Allies assembled the largest ever hoplite

Hoplite

A hoplite was a citizen-soldier of the Ancient Greek city-states. Hoplites were primarily armed as spearmen and fought in a phalanx formation. The word "hoplite" derives from "hoplon" , the type of the shield used by the soldiers, although, as a word, "hopla" could also denote weapons held or even...

army, and marched north from the isthmus to confront Mardonius. At the ensuing Battle of Plataea

Battle of Plataea

The Battle of Plataea was the final land battle during the second Persian invasion of Greece. It took place in 479 BC near the city of Plataea in Boeotia, and was fought between an alliance of the Greek city-states, including Sparta, Athens, Corinth and Megara, and the Persian Empire of Xerxes...

, the Greek infantry again proved its superiority, inflicting a severe defeat on the Persians, killing Mardonius in the process. On the same day, across the Aegean Sea

Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea[p] is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea located between the southern Balkan and Anatolian peninsulas, i.e., between the mainlands of Greece and Turkey. In the north, it is connected to the Marmara Sea and Black Sea by the Dardanelles and Bosporus...

an Allied navy destroyed the remnants of the Persian navy at the Battle of Mycale

Battle of Mycale

The Battle of Mycale was one of the two major battles that ended the second Persian invasion of Greece during the Greco-Persian Wars. It took place on or about August 27, 479 BC on the slopes of Mount Mycale, on the coast of Ionia, opposite the island of Samos...

. With this double defeat, the invasion was ended, and Persian power in the Aegean severely dented. The Greeks would now move over to the offensive, eventually expelling the Persians from Europe, the Aegean islands and Ionia before the war finally came to an end in 479 BC.

Sources

The main source for the Great Greco-Persian Wars is the Greek historian HerodotusHerodotus

Herodotus was an ancient Greek historian who was born in Halicarnassus, Caria and lived in the 5th century BC . He has been called the "Father of History", and was the first historian known to collect his materials systematically, test their accuracy to a certain extent and arrange them in a...

. Herodotus, who has been called the 'Father of History', was born in 484 BC in Halicarnassus, Asia Minor (then under Persian overlordship). He wrote his 'Enquiries' (Greek—Historia; English—(The) Histories

Histories (Herodotus)

The Histories of Herodotus is considered one of the seminal works of history in Western literature. Written from the 450s to the 420s BC in the Ionic dialect of classical Greek, The Histories serves as a record of the ancient traditions, politics, geography, and clashes of various cultures that...

) around 440–430 BC, trying to trace the origins of the Greco-Persian Wars, which would still have been relatively recent history (the wars finally ending in 450 BC). Herodotus's approach was entirely novel, and at least in Western society, he does seem to have invented 'history' as we know it. As Holland has it: "For the first time, a chronicler set himself to trace the origins of a conflict not to a past so remote so as to be utterly fabulous, nor to the whims and wishes of some god, nor to a people's claim to manifest destiny, but rather explanations he could verify personally."

Some subsequent ancient historians, despite following in his footsteps, criticised Herodotus, starting with Thucydides

Thucydides

Thucydides was a Greek historian and author from Alimos. His History of the Peloponnesian War recounts the 5th century BC war between Sparta and Athens to the year 411 BC...

. Nevertheless, Thucydides chose to begin his history where Herodotus left off (at the Siege of Sestos), and therefore evidently felt that Herodotus's history was accurate enough not to need re-writing or correcting. Plutarch

Plutarch

Plutarch then named, on his becoming a Roman citizen, Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus , c. 46 – 120 AD, was a Greek historian, biographer, essayist, and Middle Platonist known primarily for his Parallel Lives and Moralia...

criticised Herodotus in his essay "On The Malignity of Herodotus", describing Herodotus as "Philobarbaros" (barbarian-lover), for not being pro-Greek enough, which suggests that Herodotus might actually have done a reasonable job of being even-handed. A negative view of Herodotus was passed on to Renaissance Europe, though he remained well read. However, since the 19th century his reputation has been dramatically rehabilitated by archaeological finds which have repeatedly confirmed his version of events. The prevailing modern view is that Herodotus generally did a remarkable job in his Historia, but that some of his specific details (particularly troop numbers and dates) should be viewed with skepticism. Nevertheless, there are still some historians who believe Herodotus made up much of his story.

The Sicilian historian Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus was a Greek historian who flourished between 60 and 30 BC. According to Diodorus' own work, he was born at Agyrium in Sicily . With one exception, antiquity affords no further information about Diodorus' life and doings beyond what is to be found in his own work, Bibliotheca...

, writing in the 1st century BC in his Bibliotheca Historica

Bibliotheca historica

Bibliotheca historica , is a work of universal history by Diodorus Siculus. It consisted of forty books, which were divided into three sections. The first six books are geographical in theme, and describe the history and culture of Egypt , of Mesopotamia, India, Scythia, and Arabia , of North...

, also provides an account of the Greco-Persian wars, partially derived from the earlier Greek historian Ephorus

Ephorus

Ephorus or Ephoros , of Cyme in Aeolia, in Asia Minor, was an ancient Greek historian. Information on his biography is limited; he was the father of Demophilus, who followed in his footsteps as a historian, and to Plutarch's claim that Ephorus declined Alexander the Great's offer to join him on his...

. This account is fairly consistent with Herodotus's. The Greco-Persian wars are also described in less detail by a number of other ancient historians including Plutarch, Ctesias

Ctesias

Ctesias of Cnidus was a Greek physician and historian from Cnidus in Caria. Ctesias, who lived in the 5th century BC, was physician to Artaxerxes Mnemon, whom he accompanied in 401 BC on his expedition against his brother Cyrus the Younger....

, and are alluded by other authors, such as the playwright Aeschylus

Aeschylus

Aeschylus was the first of the three ancient Greek tragedians whose work has survived, the others being Sophocles and Euripides, and is often described as the father of tragedy. His name derives from the Greek word aiskhos , meaning "shame"...

. Archaeological evidence, such as the Serpent Column

Serpent Column

The Serpent Column — also known as the Serpentine Column, Delphi Tripod or Plataean Tripod — is an ancient bronze column at the Hippodrome of Constantinople in what is now Istanbul, Turkey...

, also supports some of Herodotus's specific claims.

Background

The Greek city-states of Athens and EretriaEretria

Erétria was a polis in Ancient Greece, located on the western coast of the island of Euboea, south of Chalcis, facing the coast of Attica across the narrow Euboean Gulf. Eretria was an important Greek polis in the 6th/5th century BC. However, it lost its importance already in antiquity...

had supported the unsuccessful Ionian Revolt

Ionian Revolt

The Ionian Revolt, and associated revolts in Aeolis, Doris, Cyprus and Caria, were military rebellions by several regions of Asia Minor against Persian rule, lasting from 499 BC to 493 BC...

against the Persian Empire of Darius I in 499–494 BC. The Persian Empire was still relatively young, and prone to revolts amongst its subject peoples. Moreover, Darius was a usurper, and had spent considerable time extinguishing revolts against his rule. The Ionian revolt threatened the integrity of his empire, and Darius thus vowed to punish those involved (especially those not already part of the empire). Darius also saw the opportunity to expand his empire into the fractious world of Ancient Greece. A preliminary expedition under Mardonius, in 492 BC, to secure the land approaches to Greece ended with the re-conquest of Thrace

Thrace

Thrace is a historical and geographic area in southeast Europe. As a geographical concept, Thrace designates a region bounded by the Balkan Mountains on the north, Rhodope Mountains and the Aegean Sea on the south, and by the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara on the east...

and forced Macedon

Macedon

Macedonia or Macedon was an ancient kingdom, centered in the northeastern part of the Greek peninsula, bordered by Epirus to the west, Paeonia to the north, the region of Thrace to the east and Thessaly to the south....

to become a client kingdom of Persia.

Darius thus put together an amphibious task force under Datis

Datis

For other uses of the word Dati, see Dati .Datis or Datus was a Median admiral who served the Persian Empire, under Darius the Great...

and Artaphernes

Artaphernes (son of Artaphernes)

Artaphernes, son of Artaphernes, was the nephew of Darius the Great, and a general of the Achaemenid Empire.He was appointed, together with Datis, to take command of the expedition sent by Darius to punish Athens and Eretria for their support for the Ionian Revolt. Artaphernes and Datis besieged...

in 490 BC, which attacked Naxos, before receiving the submission of the other Cycladic Islands

Cyclades

The Cyclades is a Greek island group in the Aegean Sea, south-east of the mainland of Greece; and a former administrative prefecture of Greece. They are one of the island groups which constitute the Aegean archipelago. The name refers to the islands around the sacred island of Delos...

. The task force then moved on Eretria, which it besieged and destroyed. Finally, it moved to attack Athens, landing at the bay of Marathon

Marathon, Greece

Marathon is a town in Greece, the site of the battle of Marathon in 490 BC, in which the heavily outnumbered Athenian army defeated the Persians. The tumulus or burial mound for the 192 Athenian dead that was erected near the battlefield remains a feature of the coastal plain...

, where it was met by a heavily outnumbered Athenian army. At the ensuing Battle of Marathon, the Athenians won a remarkable victory, which resulted in the withdrawal of the Persian army to Asia.

Darius therefore began raising a huge new army with which he meant to completely subjugate Greece; however, in 486 BC, his Egyptian

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt was an ancient civilization of Northeastern Africa, concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in what is now the modern country of Egypt. Egyptian civilization coalesced around 3150 BC with the political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaoh...

subjects revolted, indefinitely postponing any Greek expedition. Darius then died whilst preparing to march on Egypt, and the throne of Persia passed to his son Xerxes I. Xerxes crushed the Egyptian revolt, and very quickly re-started the preparations for the invasion of Greece.

Persian preparations

Since this was to be a full scale invasion, it required long-term planning, stock-piling and conscription. Xerxes decided that the Hellespont would be bridged to allow his army to cross to Europe, and that a canal should be dug across the isthmus of Mount AthosMount Athos

Mount Athos is a mountain and peninsula in Macedonia, Greece. A World Heritage Site, it is home to 20 Eastern Orthodox monasteries and forms a self-governed monastic state within the sovereignty of the Hellenic Republic. Spiritually, Mount Athos comes under the direct jurisdiction of the...

(rounding which headland, a Persian fleet had been destroyed in 492 BC). These were both feats of exceptional ambition, which would have been beyond any contemporary state. However, the campaign was delayed one year because of another revolt in Egypt and Babylonia

Babylonia

Babylonia was an ancient cultural region in central-southern Mesopotamia , with Babylon as its capital. Babylonia emerged as a major power when Hammurabi Babylonia was an ancient cultural region in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq), with Babylon as its capital. Babylonia emerged as...

.

In 481 BC

481 BC

Year 481 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Vibulanus and Fusus...

, after roughly four years of preparation, Xerxes began to muster the troops for the invasion of Europe. Herodotus gives the names of 46 nations from which troops were drafted. The Persian army was gathered in Asia Minor

Asia Minor

Asia Minor is a geographical location at the westernmost protrusion of Asia, also called Anatolia, and corresponds to the western two thirds of the Asian part of Turkey...

in the summer and autumn of 481 BC

481 BC

Year 481 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Vibulanus and Fusus...

. The armies from the Eastern satrapies was gathered in Kritala, Cappadocia

Cappadocia

Cappadocia is a historical region in Central Anatolia, largely in Nevşehir Province.In the time of Herodotus, the Cappadocians were reported as occupying the whole region from Mount Taurus to the vicinity of the Euxine...

and were led by Xerxes to Sardis

Sardis

Sardis or Sardes was an ancient city at the location of modern Sart in Turkey's Manisa Province...

where they passed the winter. Early in spring it moved to Abydos

Abydos, Hellespont

For other uses, see Abydos Abydos , an ancient city of Mysia, in Asia Minor, situated at Nara Burnu or Nagara Point on the best harbor on the Asiatic shore of the Hellespont. Across Abydos lies Sestus on the European side marking the shortest point in the Dardanelles, scarcely a mile broad...

where it was joined with the armies of the western satrapies. Then the army which Xerxes had mustered marched towards Europe, crossing the Hellespont on two pontoon bridge

Pontoon bridge

A pontoon bridge or floating bridge is a bridge that floats on water and in which barge- or boat-like pontoons support the bridge deck and its dynamic loads. While pontoon bridges are usually temporary structures, some are used for long periods of time...

s.

Army

The numbers of troops which Xerxes mustered for the second invasion of Greece have been the subject of endless dispute, because the numbers given in ancient sources are very large indeed. Herodotus claimed that there were, in total, 2.5 million military personnel, accompanied by an equivalent number of support personnel. The poet SimonidesSimonides of Ceos

Simonides of Ceos was a Greek lyric poet, born at Ioulis on Kea. The scholars of Hellenistic Alexandria included him in the canonical list of nine lyric poets, along with Bacchylides and Pindar...

, who was a near-contemporary, talks of four million; Ctesias

Ctesias

Ctesias of Cnidus was a Greek physician and historian from Cnidus in Caria. Ctesias, who lived in the 5th century BC, was physician to Artaxerxes Mnemon, whom he accompanied in 401 BC on his expedition against his brother Cyrus the Younger....

gave 800,000 as the total number of the army that was assembled by Xerxes. Whilst it has been suggested that Herodotus or his sources had access to official Persian Empire records of the forces involved in the expedition, modern scholars tend to reject these figures based on knowledge of the Persian military systems, their logistical capabilities, the Greek countryside, and supplies available along the army's route.

Modern scholars thus generally attribute the numbers given in the ancient sources to the result of miscalculations or exaggerations on the part of the victors, or disinformation by the Persians in the run up to the war. The topic has been hotly debated but the modern consensus revolves around the figure of 200–250,000. Nevertheless, whatever the real numbers were, it is clear that Xerxes was anxious to ensure a successful expedition by mustering overwhelming numerical superiority by land and by sea, and also that much of the army died of starvation and disease, never returning to Asia.

Herodotus tells us that the army and navy, whilst moving through Thrace, was halted at Doriskos

Doriskos

Doriskos was an ancient Greek city located in Thrace, located in the region between the river Nestos to the river Hebros. It was a fortified stronghold located in the homonymous plain and beach extending west of the Hebros delta and east of the peraia of Samothrace, actually located in the river...

for an inspection by Xerxes, and he recounts the numbers of troops found to be present:

| Units | Numbers |

|---|---|

| 1,207 trireme Trireme A trireme was a type of galley, a Hellenistic-era warship that was used by the ancient maritime civilizations of the Mediterranean, especially the Phoenicians, ancient Greeks and Romans.The trireme derives its name from its three rows of oars on each side, manned with one man per oar... s with 200-man crews from 12 ethnic group Ethnic group An ethnic group is a group of people whose members identify with each other, through a common heritage, often consisting of a common language, a common culture and/or an ideology that stresses common ancestry or endogamy... s: Phoenicia Phoenicia Phoenicia , was an ancient civilization in Canaan which covered most of the western, coastal part of the Fertile Crescent. Several major Phoenician cities were built on the coastline of the Mediterranean. It was an enterprising maritime trading culture that spread across the Mediterranean from 1550... ns of Palestine Palestine Palestine is a conventional name, among others, used to describe the geographic region between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River, and various adjoining lands.... , Egyptians Ancient Egypt Ancient Egypt was an ancient civilization of Northeastern Africa, concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in what is now the modern country of Egypt. Egyptian civilization coalesced around 3150 BC with the political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaoh... , Cyprians Greek Cypriots Greek Cypriots are the ethnic Greek population of Cyprus, forming the island's largest ethnolinguistic community at 77% of the population. Greek Cypriots are mostly members of the Church of Cyprus, an autocephalous Greek Orthodox Church within the wider communion of Orthodox Christianity... , Cilicia Cilicia In antiquity, Cilicia was the south coastal region of Asia Minor, south of the central Anatolian plateau. It existed as a political entity from Hittite times into the Byzantine empire... ns, Pamphylia Pamphylia In ancient geography, Pamphylia was the region in the south of Asia Minor, between Lycia and Cilicia, extending from the Mediterranean to Mount Taurus . It was bounded on the north by Pisidia and was therefore a country of small extent, having a coast-line of only about 75 miles with a breadth of... ns, Lycia Lycia Lycia Lycian: Trm̃mis; ) was a region in Anatolia in what are now the provinces of Antalya and Muğla on the southern coast of Turkey. It was a federation of ancient cities in the region and later a province of the Roman Empire... ns, Dorians of Asia, Caria Caria Caria was a region of western Anatolia extending along the coast from mid-Ionia south to Lycia and east to Phrygia. The Ionian and Dorian Greeks colonized the west of it and joined the Carian population in forming Greek-dominated states there... ns, Ionia Ionia Ionia is an ancient region of central coastal Anatolia in present-day Turkey, the region nearest İzmir, which was historically Smyrna. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements... ns, Aegean islanders Aegean Islands The Aegean Islands are the group of islands in the Aegean Sea, with mainland Greece to the west and north and Turkey to the east; the island of Crete delimits the sea to the south, those of Rhodes, Karpathos and Kasos to the southeast... , Aeolians Aeolis Aeolis or Aeolia was an area that comprised the west and northwestern region of Asia Minor, mostly along the coast, and also several offshore islands , where the Aeolian Greek city-states were located... , Greeks from Pontus Pontus Pontus or Pontos is a historical Greek designation for a region on the southern coast of the Black Sea, located in modern-day northeastern Turkey. The name was applied to the coastal region in antiquity by the Greeks who colonized the area, and derived from the Greek name of the Black Sea: Πόντος... |

241,400 |

| 30 marines per triremefrom the Persians Persian people The Persian people are part of the Iranian peoples who speak the modern Persian language and closely akin Iranian dialects and languages. The origin of the ethnic Iranian/Persian peoples are traced to the Ancient Iranian peoples, who were part of the ancient Indo-Iranians and themselves part of... , Medes Medes The MedesThe Medes... or Sacae |

36,210 |

| 3,000 Galleys, including 50-oar penteconters Penteconter (ship) The penteconter, alt. spelling pentekonter, also transliterated as pentecontor or pentekontor was an ancient Greek galley in use since the archaic period.... (80-man crew), 30-oared ships, light galleys and heavy horse-transports |

240,000b |

| Total of ships' complements | 517,610 |