Phalanx formation

Encyclopedia

The phalanx is a rectangular mass military formation

, usually composed entirely of heavy infantry

armed with spear

s, pikes

, sarissa

s, or similar weapon

s. The term is particularly (and originally) used to describe the use of this formation in Ancient Greek

war

fare, although the ancient Greek writers used it to also describe any massed infantry formation, regardless of its equipment, as does Arrian

in his Array against the Allans when he refers to his legions. In Greek texts, the phalanx may be deployed for battle, on the march, even camped, thus describing the mass of infantry or cavalry that would deploy in line during battle. They used shields to block others from getting in. They marched forward as one entity, crushing opponents. The word phalanx is derived from the Greek word phalanx, meaning the finger.

While the Spartan phalanx used a shorter more versatile spear, the Macedonian phalanx that Alexander commanded used a "sarissa" which was a much longer and heavier spear which required the use of two hands.

The term itself, as used today, does not refer to a distinctive military unit or division (e.g., the Roman legion or the contemporary Western-type battalion) but to the general formation of an army's troops. Thus a phalanx does not have a standard combat strength or composition but includes the total number of infantry, which is or will be deployed in action in a single phalanx formation.

Many spear-armed troops historically fought in what might be termed phalanx-like formations. The word has come into use in common English to describe "a group of people standing, or moving forward closely together"; c.f. "a phalanx of police".

This article, however, focuses on the use of the military phalanx formation in Ancient Greece

, the Hellenistic world

, and other ancient states heavily influenced by Greek civilization.

The earliest known depiction of a phalanx-like formation occurs in a Sumerian stele

The earliest known depiction of a phalanx-like formation occurs in a Sumerian stele

from the 25th century BC

. Here the troops seem to have been equipped with spear

s, helmets, and large shields

covering the whole body. Ancient Egyptian infantry were known to have employed similar formations. The first usage of the term phalanx comes from Homer

's "(φαλαγξ)", used to describe hoplites fighting in an organized battle line. Homer used the term to differentiate the formation-based combat from the individual duel

s so often found in his poems.

Historian

s have not arrived at a consensus about the relationship between the Greek

formation and these predecessors. The principles of shield wall

and spear hedge were almost universally known among the armies of major civilizations throughout history, and so the similarities may be related to convergent evolution

instead of diffusion.

Traditionally historians date the origin of the hoplite

phalanx of ancient Greece to the 8th century BC in Sparta

, but this is under revision. It is perhaps more likely that the formation was devised in the 7th century BC after the introduction of the aspis

(a shield also known as the hoplon) by the city of Argos

, which would have made the formation possible. This is further evidenced by the Chigi vase

, dated to 650 BC, identifying hoplites armed with aspis, spear and panoply

.

Another possible theory as to the birth of Greek phalanx warfare stems from the idea that some of the basic aspects of the phalanx were present in earlier times yet were not fully developed due to the lack of appropriate technology. Two of the basic strategies seen in earlier warfare include the principle of cohesion and the use of large groups of soldiers. This would suggest that the Greek phalanx was rather the culmination and perfection of a slowly developed idea which originated many years earlier. As weaponry and armour advanced through the years in different city-states the phalanx became complex and effective.

The hoplite

The hoplite

phalanx of the Archaic

and Classical

periods in Greece (ca. 750–350 BC) was a formation in which the hoplites would line up in ranks in close order. The hoplites would lock their shields together, and the first few ranks of soldiers would project their spears out over the first rank of shields. The phalanx therefore presented a shield wall and a mass of spear points to the enemy, making frontal assaults much more difficult. It also allowed a higher proportion of the soldiers to be actively engaged in combat at a given time (rather than just those in the front rank).

Battles between two phalanxes usually took place in open, flat plains where it was easier to advance and stay in formation. Rough terrain or hilly regions would have made it difficult to maintain a steady line and would have defeated the purpose of employing the use of a phalanx. As a result, battles between Greek city-states would not take place in any possible location nor would they be limited to sometimes obvious strategic points. Rather, many times, the two opposing sides would find the most suitable piece of land where the conflict could be settled.

The phalanx usually advanced at a walking pace, although it is possible that they picked up speed during the last several yards. One of the main reasons for this slow approach was to maintain formation. If the phalanx lost its shape as it approached the enemy it would be rendered useless. If the hoplites of the phalanx were to pick up speed toward the latter part of the advance it would have been for the purpose of gaining momentum against the enemy in the initial collision. Herodotus states, of the Greeks at the Battle of Marathon

, that "They were the first Greeks we know of to charge their enemy at a run". Many historians believe that this innovation was precipitated by their desire to minimize their losses from Persian archery. The opposing sides would collide, possibly shivering many of the spears of the front row. The battle would then rely on the valour of the men in the front line; whilst those in the rear maintained forward pressure on the front ranks with their shields. When in combat, the whole formation would consistently press forward trying to break the enemy formation; thus when two phalanx formations engaged, the struggle essentially became a pushing match.

This "physical pushing match" theory is the most widely accepted interpretation of the ancient sources. Historians such as Victor Davis Hanson

point out that it is difficult to account for exceptionally deep phalanx formations unless they were necessary to facilitate the physical pushing depicted by this theory, as those behind the first two ranks could not take part in the actual spear thrusting.

Yet it should be noted that no Greek art ever depicts anything like a phalanx pushing match and this hypothesis is a product of educated speculation rather than explicit testimony from contemporary sources. The Greek term for "push" was used in the same metaphorical manner as the English word is (for example it was also used to describe the process of rhetorical arguments) and so cannot be said to necessarily describe a literal, physical, push of the enemy, although it is possible that it did. In short, the hypothesis is far from being academically resolved.

For instance, if Othismos was to accurately describe a physical pushing match, it would be logical to state that the deeper phalanx would always win an engagement, since the physical strength of individuals would not compensate for even one additional rank on the enemy side. However, there are numerous examples of shallow phalanxes holding off an opponent. For instance, at Delium in 424 the Athenian left flank, a formation eight men deep, held off a formation of Thebans twenty-five deep without immediate collapse. It is difficult with the physical pushing model to imagine eight men withstanding the pushing force of twenty-five opponents for a matter of seconds, let alone half the battle.

Such arguments have led to a wave of counter-criticism to physical shoving theorists. Adrian Goldsworthy, in his article "The Othismos, Myths and Heresies: The nature of Hoplite Battle" argues that the physical pushing match model does not fit with the average casualty figures of hoplite warfare, nor the practical realities of moving large formations of men in battle. This debate has yet to be resolved amongst scholars.

Each individual hoplite carried his shield on the left arm, protecting not only himself but the soldier to the left. This meant that the men at the extreme right of the phalanx were only half-protected. In battle, opposing phalanxes would exploit this weakness by attempting to overlap the enemy's right flank. It also meant that, in battle, a phalanx would tend to drift to the right (as hoplites sought to remain behind the shield of their neighbour). The most experienced hoplites were often placed on the right side of the phalanx, to avoid these problems. Some groups, such as the Spartans at Nemea, tried to use this phenomenon to their advantage. In this case the phalanx would sacrifice their left side, which typically consisted of allied troops, in an effort to overtake the enemy from the flank. It is unlikely that this strategy worked very often, as it is not mentioned frequently in ancient Greek literature.

There was a leader in each row of a phalanx, and a rear rank officer, the ouragos (meaning tail-leader), who kept order in the rear. The phalanx is thus an example of a military formation in which the individualistic elements of battle were suppressed for the good of the whole. The hoplites had to trust their neighbours to protect them, and be willing to protect their neighbour; a phalanx was thus only as strong as its weakest elements. The effectiveness of the phalanx therefore depended upon how well the hoplites could maintain this formation while in combat, and how well they could stand their ground, especially when engaged against another phalanx. For this reason, the formation was deliberately organized to group friends and family closely together, thus providing a psychological incentive to support one's fellows, and a disincentive through shame to panic or attempt to flee. The more disciplined and courageous the army the more likely it was to win – often engagements between the various city-states of Greece would be resolved by one side fleeing before the battle. The Greek word dynamis, the "will to fight", expresses the drive that kept hoplites in formation.

"Now of those, who dare, abiding one beside another, to advance to the close fray, and the foremost champions, fewer die, and they save the people in the rear; but in men that fear, all excellence is lost. No one could ever in words go through those several ills, which befall a man, if he has been actuated by cowardice. For 'tis grievous to wound in the rear the back of a flying man in hostile war. Shameful too is a corpse lying low in the dust, wounded behind in the back by the point of a spear." Tyrtaeus

: The War Songs Of Tyrtaeus

The phalanx of the Ancient Macedonian kingdom

and the later Hellenistic successor states

was a development of the hoplite phalanx. The 'phalangites' were armed with much longer spears (the sarissa; see below), and less heavily armoured. Since the sarissa was wielded two-handed, phalangites carried much smaller shields that were strapped to their arms. Therefore, although a Macedonian phalanx would have formed up in a similar manner to the hoplite phalanx, it possessed very different tactical properties. With the extra spear length, up to five rows of phalangites could project their weapon beyond the front rank—keeping the enemy troops at a greater distance. The Macedonian phalanx was much less able to form a shield wall, but the lengthened spears would have compensated for this. Such a phalanx formation also reduces the likelihood that battles would degenerate into a pushing match.

See also Ancient Macedonian army.

provided their own equipment. The primary hoplite weapon was a spear

around 2.4 meters in length called a dory

. Although accounts of its length vary, it is usually now believed to have been seven to nine feet long (~2.1–2.7 m). It was held one-handed, with the other hand holding the hoplite's shield. The spearhead was usually a curved leaf shape, while the rear of the spear had a spike called a sauroter ('lizard-killer') which was used to stand the spear in the ground (hence the name). It was also used as a secondary weapon if the main shaft snapped. This was a common issue especially for soldiers who were involved with the initial clash with the enemy. Despite the snapping of the spear, Hoplites could easily switch to the sauroter without great consequence. The rear ranks also used the secondary end to finish off fallen opponents as the phalanx advanced over them. It is a matter of contention among historians whether the hoplite used the spear overarm or underarm. Held underarm, the thrusts would have been less powerful but under more control, and vice versa. It seems likely that both motions were used, depending on the situation. If attack was called for, an overarm motion was more likely to break through an opponent's defence. The upward thrust is more easily deflected by armour due to its lesser leverage. However, when defending, an underarm carry absorbed more shock and could be 'couched' under the shoulder for maximum stability. It should also be said that an underarm motion would allow more effective combination of the aspis

and doru if the shield wall had broken down, while the overarm motion would be more effective when the shield had to be interlocked with those of one's neighbours in the battle-line. Hoplites in the rows behind the lead would almost certainly have made overarm thrusts. The rear ranks held their spears underarm, and raised shields upwards at increasing angles. This was an effective defence against missiles, deflecting their force.

Throughout the hoplite era the standard hoplites' armour went through many cyclical changes. An Archaic hoplite typically wore a bronze

breastplate

, a bronze helmet

with cheekplates, as well as greave

s and other armour

. Later, in the classical period, the breastplate became less common, replaced instead with a mixture of linen padding and hanging strips of leather. Eventually even greaves became less commonly used, although degrees of heavier armour remained, as attested by Xenophon

as late as 401 BC.

Such changes reflected the balancing of mobility with protection, especially as cavalry became more prominent in the Peloponnesian War

and the need to combat light troops which were increasingly used to negate the hoplites role as the primary force in battle. Yet bronze armour remained in some form until the end of the hoplite era. Some archaeologists have pointed out bronze armour does not actually provide as much protection from direct blows as more extensive corselet padding, and have suggested its continued use was a matter of status for those who could afford it. Such theories remind us that practicality and cultural preference do not always correlate.

In classical Greek dialect there is, in fact, no word for swordsmen yet hoplites also carried a short sword called a xiphos. The short sword was a secondary weapon, used if the doru was broken or lost. Samples of the xiphos recovered at excavation sites typically were found to be around 2 ft in length. These swords were double sided and could therefore be used in both the swinging and thrusting motion.

Hoplites carried a circular shield called an aspis

(often referred to as a hoplon) made from wood and covered in bronze, measuring roughly 1 meter in diameter. It spanned from chin to knee and was very heavy (8–15 kg). This medium-sized shield (and indeed, large for the time) was made possible partly by its dish-like shape, which allowed it to be supported with the rim on the shoulder. This was quite an important feature of the shield especially for the hoplites that remained in the latter ranks. While these soldiers continued to help press forward they did not have the added burden of holding up their shield. But the circular shield was not without its disadvantages. Despite its mobility, protective curve, and double straps the circular shape created gaps in the shield wall at both its top and bottom. These gaps left parts of the hoplite exposed to potentially lethal spear thrusts and were always an area of concern for hoplites controlling the front lines.

was the pike used by the Ancient Macedonian army. The actual length of the sarissa is now unknown, but apparently it was twice as long as the doru. This makes it at least 14 feet (~4.3m), but 18 feet (~5.5m) appears more likely. (The cavalry xyston

was 12.5 feet (~3.8m) by comparison.) The great length of the pike was balanced by a counterweight at the rear end, which also functions as a butt-spike, allowing the sarissa to be planted into the ground. Because of its great length, weight and differing balance, a sarissa was wielded two-handed. This meant that the aspis was no longer a practical defence. Instead, the phalangites strapped a smaller pelte shield (usually reserved for light skirmishers – peltast

s) to their left forearm. Although this reduced the shield wall, the extreme length of the spear prevented most enemies from closing, as the pikes of the first three to five ranks could all be brought to bear in front of the front row. In addition, the last 6-18 ranks of soldiers held their spears in the air, making an effective barrier against missiles. This pike had to be held underhand, as the shield would have obscured the soldier's vision had it been held overhead. It would also be very hard to remove a sarissa from anything it stuck in (the earth, shields, and soldiers of the opposition) if it were thrust downwards, due to its length.

for the Spartans) was the greatest standard hoplitic formation of 500 to 1500 men, led by a strategos

(general). The entire army, a total of several taxeis or morae was led by a generals' council. The commander-in-chief was usually called a polemarchos or a strategos autocrator.

and Mantinea

, the Theban general Epaminondas

arranged the left wing of the phalanx into a "hammerhead" of 50 ranks of elite hoplites deep (see below) and when depth was less important, phalanxes just 4 deep are recorded, as at the battle of Marathon.

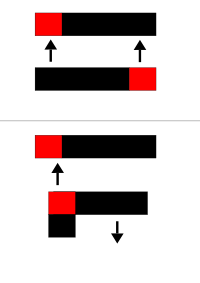

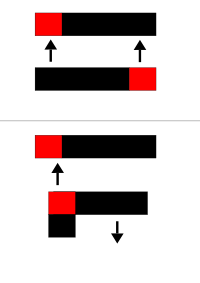

The phalanx depth could vary depending on the needs of the moment and plans of the general. While the phalanx was in march, an eis bathos formation (loose, meaning literally "in depth") was adopted in order to move more freely and maintain order. This was also the initial battle formation as, in addition, permitted friendly units to pass through either assaulting or retreating. In this status, the phalanx had double depth than the normal and each hoplite had to occupy about 1.8-2m in width (6–7 ft). When enemy infantry was approaching, a rapid switch to the pycne (spelled also pucne) formation (dense or tight formation) was necessary. In that case, each man's space was cut in half (0.9-1m or 3 ft in width) and the formation depth was turning on normal. A yet more dense formation used when the phalanx was to experience extra pressure, intense missile volleys or frontal cavalry charges, was the synaspismos or sunaspismos (ultra tight or locked shields formation). In synaspismos the rank depth was half of the normal and the width each men occupied was as small as 0.45 m (1.5 ft)

Ephodos: The hoplites stop singing their paeanes (battle hymns) and move towards the enemy, gradually picking up pace and momentum. In the instants before impact war cries (alalagmoe, sing. alalagmos) would be made. Notable war cries were the Athenian (elelelelef! elelelelef!) and the Macedonian (alalalalai! alalalalai!) alalagmoe.

Krousis: The opposing phalanxes meet each other almost simultaneously along their front. The promachoe (the front-liners) had to be physically and psychologically fit to sustain and survive the clash.

Doratismos: Repeated, rapid spear thrusts in order to disrupt the enemy formation.

Othismos: Literally "pushing" after most spears have been broken, the hoplites begin to push with their large shields and use their secondary weapon, the sword. This could be the longest phase.

Pararrhexis: "Breaching" the opposing phalanx, the enemy formation shatters and the battle ends.

The early history of the phalanx is largely one of combat between hoplite armies from competing Greek city-state

The early history of the phalanx is largely one of combat between hoplite armies from competing Greek city-state

s. The usual result was rather identical, inflexible formations pushing against each other until one broke. The potential of the phalanx to achieve something more was demonstrated at Battle of Marathon

(490 BC). Facing the much larger army of Darius I, the Athenians thinned out their phalanx and consequently lengthened their front, to avoid being outflanked. However, even a reduced-depth phalanx proved unstoppable to the lightly armed Persian infantry. After routing the Persian wings, the hoplites on the Athenian wings wheeled inwards, destroying the elite troop at the Persian centre, resulting in a crushing victory for Athens. Throughout the Greco-Persian Wars

the hoplite phalanx was to prove superior to the Persian infantry (e.g. The battles of Thermopylae

and Plataea

).

Perhaps the most prominent example of the phalanx's evolution was the oblique

advance, made famous in the Battle of Leuctra

. There, the Theban general Epaminondas

thinned out the right flank and centre of his phalanx, and deepened his left flank to an unheard-of 50 men deep. In doing so, Epaminondas reversed the convention by which the right flank of the phalanx was strongest. This allowed the Thebans to assault in strength the elite Spartan troops on the right flank of the opposing phalanx. Meanwhile, the centre and right flank of the Theban line were echeloned back, from the opposing phalanx, keeping the weakened parts of the formation from being engaged. Once the Spartan right had been routed by the Theban left, the remainder of the Spartan line also broke. Thus by localising the attacking power of the hoplites, Epaminondas was able to defeat an enemy previously thought invincible.

Philip II of Macedon

spent several years in Thebes as a hostage, and paid attention to Epaminondas' innovations. Upon return to his homeland, he raised a revolutionary new infantry force, which was to change the face of the Greek world. Phillip's phalangites were the first force of professional soldiers seen in Ancient Greece apart from Sparta. They were armed with longer spears and were drilled more thoroughly in more evolved, complicated tactics and manoeuvres. More importantly, though, Phillip's phalanx was part of a multi-faceted, combined force that included a variety of skirmisher

s and cavalry

, most notably the famous Companion cavalry

. The Macedonian phalanx now was used to pin the centre of the enemy line, while cavalry and more mobile infantry struck at the foe's flanks. Its supremacy over the more static armies fielded by the Greek city-states was shown at the Battle of Chaeronea

, where Philip II's army crushed the allied Theban and Athenian phalanxes.

, where an Athenian contingent led by Iphicrates

routed an entire Sparta

n mora (a unit of anywhere from 500 to 900 hoplites). The Athenian force had a considerable proportion of light missile troops armed with javelin

s and bows

which wore down the Spartans with repeated attacks, causing disarray in the Spartan ranks and an eventual rout

when they spotted Athenian heavy infantry reinforcements trying to flank them by boat.

The Macedonian Phalanx had weaknesses similar to its hoplitic predecessor. Theoretically indestructible from the front, its flanks and rear were very vulnerable, and once engaged it could probably not easily disengage or redeploy to face a threat from those directions. Thus, a phalanx facing non-phalangite formations required some sort of protection on its flanks—lighter or at least more mobile infantry, cavalry, etc. This was shown at the Battle of Magnesia

, where, once the Seleucid supporting infantry elements were driven off, the phalanx was helpless against its Roman opponents.

The Macedonian phalanx

could also lose its cohesion without proper coordination and/or while moving through broken terrain; doing so could create gaps between individual blocks/syntagmata, or could prevent a solid front within those sub-units as well, causing other sections of the line to bunch up. In this event, as in the battles of Cynoscephalae

and Pydna

, the phalanx became vulnerable to attacks by more flexible units—such as Roman legionary centuries, which were able to avoid the sarissae and engage in hand-to-hand combat with the phalangites.

Another important area that must be considered concerns the psychological tendencies of the hoplites. Because the strength of a phalanx was dependent on the ability of the hoplites to maintain their frontline it was crucial that a phalanx be able to quickly and efficiently replace fallen soldiers in the frontal ranks. If a phalanx failed to do this in a structured manner the opposing phalanx would have an opportunity to breach the line which, many times, would lead to a quick defeat. This then implies that the hoplites ranks closer to the front must be mentally prepared to replace their fallen comrade and adapt to his new position without disrupting the structure of the frontline.

Finally, most of the phalanx-centric armies tended to lack supporting echelons behind the main line of battle. This meant that breaking through the line of battle or compromising one of its flanks often ensured victory.

The decline of the diadochi

and the phalanx was inextricably linked with the rise of Rome and the Roman legion

, from the 3rd century BC. Before the formation of the Roman Republic

, the Romans had originally employed the phalanx themselves, but gradually evolved more flexible tactics resulting in the three-line Roman legion

of the mid-Roman Republic. The phalanx continued to be employed by the Romans as a tactic for their third military line or triarii

of veteran reserve troops armed with the hasta

e or spear. Rome would eventually conquer most of the Macedonian successor states, and the various Greek city-states and leagues. These territories were incorporated into the Roman Republic, and as these Hellenic states had ceased to exist, so did the armies which had used the traditional phalanx formation. Subsequently, troops raised from these regions by the Romans would have been equipped and fought in line on the Roman model.

However, the phalanx did not disappear as a military tactic altogether. There is some question as to whether the phalanx was actually obsolete by the end of its history. In some of the major battles between the Roman Army and Hellenistic phalanxes, Pydna (168 BC)

, Cynoscephalae (197 BC)

and Magnesia (190 BC)

, the phalanx performed relatively well against the Roman army, initially driving back the Roman infantry. However, at Cynoscephalae and Magnesia, failure to defend the flanks of the Phalanx led to defeat; whilst at Pydna, the loss of cohesion of the Phalanx when pursuing retreating Roman soldiers allowed the Romans to penetrate the formation, where the latter's close combat skills proved decisive.

Spear-armed troops continued to be important elements in many armies until the advent of reliable firearms, but did not necessarily fight in the manner of a phalanx. A meaningful comparison can be made between the Classical phalanx and late medieval pike formations

.

Particular parallels can be seen in the Middle Ages

and Renaissance

city-states of the Low Countries

(modern Holland and Belgium), the cantons of Switzerland

and the city-states of Northern Italy. Armies of the Low Countries were first armed with spears, then pikes, and were defeating French and Burgundian forces by the 14th century. The Swiss first used the halberd in the 14th century but—outreached by Austrian cavalry armed with lances—the Swiss gradually adopted pikes in the later 15th century. Swiss pike phalanxes of the Burgundian Wars

were dynamic and aggressive resulting in the destruction of the 'modern' Burgundian army and the death of Charles the Bold. It is tempting to suggest that Swiss military authorities had read Classical sources and were consciously copying Hellenistic practices. Some Italian states raised their own pike units as well as employing Swiss mercenary pikemen in the 15th and 16th century. The Swiss were also copied by German Landsknechts leading to bitterness and rivalry between competing mercenary units.

Military historians have also suggested that the Scots, particularly under William Wallace

and Robert the Bruce, consciously imitated the Hellenistic phalanx to produce the Scots 'hedgehog' or schiltron

. However this ignores possible Dark Ages

use of long spears by Picts and others in Scotland. It is possible that long spear tactics (also found in North Wales) were an established part of more irregular warfare in parts of Britain prior to 1066. The Scots certainly used imported French pikes and dynamic tactics at the Battle of Flodden Field

. However this battle found the Scots pitted against effective light artillery and advancing over bad ground which disorganised the Scots phalanxes and left them easy prey to English longbow shooting and attacks by shorter but more effective English polearms called bills. Some have interpreted contemporary sources as describing the bills cutting off the heads of Scots pikes.

Pike and shot

became a military standard in the 16th and 17th century. With the development of the bayonet

the last major use of pike was the early 18th century with the weapon rapidly disappearing in Western European armies by the time of the Battle of Blenheim

. A few pikes or half pikes and a few halberds were retained among regimental colour guards but even these were fast disappearing by the time of Napoleon.

Pike was briefly reconsidered as a weapon by the Confederate Army at the time of the American Civil War

and some were even manufactured but these were probably never issued.

Comparable formations

Tactical formation

A tactical formation is the arrangement or deployment of moving military forces such as infantry, cavalry, AFVs, military aircraft, or naval vessels...

, usually composed entirely of heavy infantry

Heavy infantry

Heavy infantry refers to heavily armed and armoured ground troops, as opposed to medium or light infantry, in which the warriors are relatively lightly armoured. As modern infantry troops usually define their subgroups differently , 'heavy infantry' almost always is used to describe pre-gunpowder...

armed with spear

Spear

A spear is a pole weapon consisting of a shaft, usually of wood, with a pointed head.The head may be simply the sharpened end of the shaft itself, as is the case with bamboo spears, or it may be made of a more durable material fastened to the shaft, such as flint, obsidian, iron, steel or...

s, pikes

Pike (weapon)

A pike is a pole weapon, a very long thrusting spear used extensively by infantry both for attacks on enemy foot soldiers and as a counter-measure against cavalry assaults. Unlike many similar weapons, the pike is not intended to be thrown. Pikes were used regularly in European warfare from the...

, sarissa

Sarissa

The sarissa or sarisa was a 4 to 7 meter long spear used in the ancient Greek and Hellenistic warfare. It was introduced by Philip II of Macedon and was used in the traditional Greek phalanx formation as a replacement for the earlier dory, which was considerably shorter. The phalanxes of Philip...

s, or similar weapon

Weapon

A weapon, arm, or armament is a tool or instrument used with the aim of causing damage or harm to living beings or artificial structures or systems...

s. The term is particularly (and originally) used to describe the use of this formation in Ancient Greek

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

war

War

War is a state of organized, armed, and often prolonged conflict carried on between states, nations, or other parties typified by extreme aggression, social disruption, and usually high mortality. War should be understood as an actual, intentional and widespread armed conflict between political...

fare, although the ancient Greek writers used it to also describe any massed infantry formation, regardless of its equipment, as does Arrian

Arrian

Lucius Flavius Arrianus 'Xenophon , known in English as Arrian , and Arrian of Nicomedia, was a Roman historian, public servant, a military commander and a philosopher of the 2nd-century Roman period...

in his Array against the Allans when he refers to his legions. In Greek texts, the phalanx may be deployed for battle, on the march, even camped, thus describing the mass of infantry or cavalry that would deploy in line during battle. They used shields to block others from getting in. They marched forward as one entity, crushing opponents. The word phalanx is derived from the Greek word phalanx, meaning the finger.

While the Spartan phalanx used a shorter more versatile spear, the Macedonian phalanx that Alexander commanded used a "sarissa" which was a much longer and heavier spear which required the use of two hands.

The term itself, as used today, does not refer to a distinctive military unit or division (e.g., the Roman legion or the contemporary Western-type battalion) but to the general formation of an army's troops. Thus a phalanx does not have a standard combat strength or composition but includes the total number of infantry, which is or will be deployed in action in a single phalanx formation.

Many spear-armed troops historically fought in what might be termed phalanx-like formations. The word has come into use in common English to describe "a group of people standing, or moving forward closely together"; c.f. "a phalanx of police".

This article, however, focuses on the use of the military phalanx formation in Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

, the Hellenistic world

Hellenistic civilization

Hellenistic civilization represents the zenith of Greek influence in the ancient world from 323 BCE to about 146 BCE...

, and other ancient states heavily influenced by Greek civilization.

Stele

A stele , also stela , is a stone or wooden slab, generally taller than it is wide, erected for funerals or commemorative purposes, most usually decorated with the names and titles of the deceased or living — inscribed, carved in relief , or painted onto the slab...

from the 25th century BC

25th century BC

The 25th century BC is a century which lasted from the year 2500 BCE to 2401 BCE.-Events:*c. 2900 BCE – 2334 BCE: Mesopotamian wars of the Early Dynastic period.*c. 2500 BCE: Rice was first introduced to Malaysia...

. Here the troops seem to have been equipped with spear

Spear

A spear is a pole weapon consisting of a shaft, usually of wood, with a pointed head.The head may be simply the sharpened end of the shaft itself, as is the case with bamboo spears, or it may be made of a more durable material fastened to the shaft, such as flint, obsidian, iron, steel or...

s, helmets, and large shields

Shields

-United Kingdom:* North Shields, Tyneside, England* South Shields, Tyneside, England* Shields Road subway station, an underground station in Glasgow, Scotland-United States:* Shields, Indiana, an unincorporated community...

covering the whole body. Ancient Egyptian infantry were known to have employed similar formations. The first usage of the term phalanx comes from Homer

Homer

In the Western classical tradition Homer , is the author of the Iliad and the Odyssey, and is revered as the greatest ancient Greek epic poet. These epics lie at the beginning of the Western canon of literature, and have had an enormous influence on the history of literature.When he lived is...

's "(φαλαγξ)", used to describe hoplites fighting in an organized battle line. Homer used the term to differentiate the formation-based combat from the individual duel

Duel

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two individuals, with matched weapons in accordance with agreed-upon rules.Duels in this form were chiefly practised in Early Modern Europe, with precedents in the medieval code of chivalry, and continued into the modern period especially among...

s so often found in his poems.

Historian

Historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human race; as well as the study of all history in time. If the individual is...

s have not arrived at a consensus about the relationship between the Greek

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

formation and these predecessors. The principles of shield wall

Shield wall

The wall, is a military tactic that was common in many cultures in the Pre-Early Modern warfare age...

and spear hedge were almost universally known among the armies of major civilizations throughout history, and so the similarities may be related to convergent evolution

Convergent evolution

Convergent evolution describes the acquisition of the same biological trait in unrelated lineages.The wing is a classic example of convergent evolution in action. Although their last common ancestor did not have wings, both birds and bats do, and are capable of powered flight. The wings are...

instead of diffusion.

Traditionally historians date the origin of the hoplite

Hoplite

A hoplite was a citizen-soldier of the Ancient Greek city-states. Hoplites were primarily armed as spearmen and fought in a phalanx formation. The word "hoplite" derives from "hoplon" , the type of the shield used by the soldiers, although, as a word, "hopla" could also denote weapons held or even...

phalanx of ancient Greece to the 8th century BC in Sparta

Sparta

Sparta or Lacedaemon, was a prominent city-state in ancient Greece, situated on the banks of the River Eurotas in Laconia, in south-eastern Peloponnese. It emerged as a political entity around the 10th century BC, when the invading Dorians subjugated the local, non-Dorian population. From c...

, but this is under revision. It is perhaps more likely that the formation was devised in the 7th century BC after the introduction of the aspis

Aspis

"Aspis" is the generic term for the word shield. The aspis, which is carried by Greek infantry of various periods, is often referred to as a hoplon .According to Diodorus Siculus:-Construction:...

(a shield also known as the hoplon) by the city of Argos

Argos

Argos is a city and a former municipality in Argolis, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Argos-Mykines, of which it is a municipal unit. It is 11 kilometres from Nafplion, which was its historic harbour...

, which would have made the formation possible. This is further evidenced by the Chigi vase

Chigi vase

The Chigi vase is a Protocorinthian olpe, or pitcher, that is the name vase of the Chigi Painter. It was found in an Etruscan tomb at Monte Aguzzo, near Cesena, on Prince Mario Chigi’s estate in 1881. The vase has been variously assigned to the middle and late protocorinthian periods and given a...

, dated to 650 BC, identifying hoplites armed with aspis, spear and panoply

Panoply

A panoply is a complete suit of armour. The word represents the ancient Greek πανοπλια. The word παν means "all", and όπλον, "arms". Thus "panoply" refers to the full armour of a hoplite or heavy-armed soldier, i.e...

.

Another possible theory as to the birth of Greek phalanx warfare stems from the idea that some of the basic aspects of the phalanx were present in earlier times yet were not fully developed due to the lack of appropriate technology. Two of the basic strategies seen in earlier warfare include the principle of cohesion and the use of large groups of soldiers. This would suggest that the Greek phalanx was rather the culmination and perfection of a slowly developed idea which originated many years earlier. As weaponry and armour advanced through the years in different city-states the phalanx became complex and effective.

Overview

Hoplite

A hoplite was a citizen-soldier of the Ancient Greek city-states. Hoplites were primarily armed as spearmen and fought in a phalanx formation. The word "hoplite" derives from "hoplon" , the type of the shield used by the soldiers, although, as a word, "hopla" could also denote weapons held or even...

phalanx of the Archaic

Archaic period in Greece

The Archaic period in Greece was a period of ancient Greek history that followed the Greek Dark Ages. This period saw the rise of the polis and the founding of colonies, as well as the first inklings of classical philosophy, theatre in the form of tragedies performed during Dionysia, and written...

and Classical

Classical Greece

Classical Greece was a 200 year period in Greek culture lasting from the 5th through 4th centuries BC. This classical period had a powerful influence on the Roman Empire and greatly influenced the foundation of Western civilizations. Much of modern Western politics, artistic thought, such as...

periods in Greece (ca. 750–350 BC) was a formation in which the hoplites would line up in ranks in close order. The hoplites would lock their shields together, and the first few ranks of soldiers would project their spears out over the first rank of shields. The phalanx therefore presented a shield wall and a mass of spear points to the enemy, making frontal assaults much more difficult. It also allowed a higher proportion of the soldiers to be actively engaged in combat at a given time (rather than just those in the front rank).

Battles between two phalanxes usually took place in open, flat plains where it was easier to advance and stay in formation. Rough terrain or hilly regions would have made it difficult to maintain a steady line and would have defeated the purpose of employing the use of a phalanx. As a result, battles between Greek city-states would not take place in any possible location nor would they be limited to sometimes obvious strategic points. Rather, many times, the two opposing sides would find the most suitable piece of land where the conflict could be settled.

The phalanx usually advanced at a walking pace, although it is possible that they picked up speed during the last several yards. One of the main reasons for this slow approach was to maintain formation. If the phalanx lost its shape as it approached the enemy it would be rendered useless. If the hoplites of the phalanx were to pick up speed toward the latter part of the advance it would have been for the purpose of gaining momentum against the enemy in the initial collision. Herodotus states, of the Greeks at the Battle of Marathon

Battle of Marathon

The Battle of Marathon took place in 490 BC, during the first Persian invasion of Greece. It was fought between the citizens of Athens, aided by Plataea, and a Persian force commanded by Datis and Artaphernes. It was the culmination of the first attempt by Persia, under King Darius I, to subjugate...

, that "They were the first Greeks we know of to charge their enemy at a run". Many historians believe that this innovation was precipitated by their desire to minimize their losses from Persian archery. The opposing sides would collide, possibly shivering many of the spears of the front row. The battle would then rely on the valour of the men in the front line; whilst those in the rear maintained forward pressure on the front ranks with their shields. When in combat, the whole formation would consistently press forward trying to break the enemy formation; thus when two phalanx formations engaged, the struggle essentially became a pushing match.

This "physical pushing match" theory is the most widely accepted interpretation of the ancient sources. Historians such as Victor Davis Hanson

Victor Davis Hanson

Victor Davis Hanson is an American military historian, columnist, political essayist and former classics professor, notable as a scholar of ancient warfare. He has been a commentator on modern warfare and contemporary politics for National Review and other media outlets...

point out that it is difficult to account for exceptionally deep phalanx formations unless they were necessary to facilitate the physical pushing depicted by this theory, as those behind the first two ranks could not take part in the actual spear thrusting.

Yet it should be noted that no Greek art ever depicts anything like a phalanx pushing match and this hypothesis is a product of educated speculation rather than explicit testimony from contemporary sources. The Greek term for "push" was used in the same metaphorical manner as the English word is (for example it was also used to describe the process of rhetorical arguments) and so cannot be said to necessarily describe a literal, physical, push of the enemy, although it is possible that it did. In short, the hypothesis is far from being academically resolved.

For instance, if Othismos was to accurately describe a physical pushing match, it would be logical to state that the deeper phalanx would always win an engagement, since the physical strength of individuals would not compensate for even one additional rank on the enemy side. However, there are numerous examples of shallow phalanxes holding off an opponent. For instance, at Delium in 424 the Athenian left flank, a formation eight men deep, held off a formation of Thebans twenty-five deep without immediate collapse. It is difficult with the physical pushing model to imagine eight men withstanding the pushing force of twenty-five opponents for a matter of seconds, let alone half the battle.

Such arguments have led to a wave of counter-criticism to physical shoving theorists. Adrian Goldsworthy, in his article "The Othismos, Myths and Heresies: The nature of Hoplite Battle" argues that the physical pushing match model does not fit with the average casualty figures of hoplite warfare, nor the practical realities of moving large formations of men in battle. This debate has yet to be resolved amongst scholars.

Each individual hoplite carried his shield on the left arm, protecting not only himself but the soldier to the left. This meant that the men at the extreme right of the phalanx were only half-protected. In battle, opposing phalanxes would exploit this weakness by attempting to overlap the enemy's right flank. It also meant that, in battle, a phalanx would tend to drift to the right (as hoplites sought to remain behind the shield of their neighbour). The most experienced hoplites were often placed on the right side of the phalanx, to avoid these problems. Some groups, such as the Spartans at Nemea, tried to use this phenomenon to their advantage. In this case the phalanx would sacrifice their left side, which typically consisted of allied troops, in an effort to overtake the enemy from the flank. It is unlikely that this strategy worked very often, as it is not mentioned frequently in ancient Greek literature.

There was a leader in each row of a phalanx, and a rear rank officer, the ouragos (meaning tail-leader), who kept order in the rear. The phalanx is thus an example of a military formation in which the individualistic elements of battle were suppressed for the good of the whole. The hoplites had to trust their neighbours to protect them, and be willing to protect their neighbour; a phalanx was thus only as strong as its weakest elements. The effectiveness of the phalanx therefore depended upon how well the hoplites could maintain this formation while in combat, and how well they could stand their ground, especially when engaged against another phalanx. For this reason, the formation was deliberately organized to group friends and family closely together, thus providing a psychological incentive to support one's fellows, and a disincentive through shame to panic or attempt to flee. The more disciplined and courageous the army the more likely it was to win – often engagements between the various city-states of Greece would be resolved by one side fleeing before the battle. The Greek word dynamis, the "will to fight", expresses the drive that kept hoplites in formation.

"Now of those, who dare, abiding one beside another, to advance to the close fray, and the foremost champions, fewer die, and they save the people in the rear; but in men that fear, all excellence is lost. No one could ever in words go through those several ills, which befall a man, if he has been actuated by cowardice. For 'tis grievous to wound in the rear the back of a flying man in hostile war. Shameful too is a corpse lying low in the dust, wounded behind in the back by the point of a spear." Tyrtaeus

Tyrtaeus

Tyrtaeus was a Greek poet who composed verses in Sparta around the time of the Second Messenian War, the date of which isn't clearly establishedsometime in the latter part of the seventh century BC...

: The War Songs Of Tyrtaeus

The phalanx of the Ancient Macedonian kingdom

Macedon

Macedonia or Macedon was an ancient kingdom, centered in the northeastern part of the Greek peninsula, bordered by Epirus to the west, Paeonia to the north, the region of Thrace to the east and Thessaly to the south....

and the later Hellenistic successor states

Diadochi

The Diadochi were the rival generals, family and friends of Alexander the Great who fought for the control of Alexander's empire after his death in 323 BC...

was a development of the hoplite phalanx. The 'phalangites' were armed with much longer spears (the sarissa; see below), and less heavily armoured. Since the sarissa was wielded two-handed, phalangites carried much smaller shields that were strapped to their arms. Therefore, although a Macedonian phalanx would have formed up in a similar manner to the hoplite phalanx, it possessed very different tactical properties. With the extra spear length, up to five rows of phalangites could project their weapon beyond the front rank—keeping the enemy troops at a greater distance. The Macedonian phalanx was much less able to form a shield wall, but the lengthened spears would have compensated for this. Such a phalanx formation also reduces the likelihood that battles would degenerate into a pushing match.

See also Ancient Macedonian army.

Hoplite armament

Each hopliteHoplite

A hoplite was a citizen-soldier of the Ancient Greek city-states. Hoplites were primarily armed as spearmen and fought in a phalanx formation. The word "hoplite" derives from "hoplon" , the type of the shield used by the soldiers, although, as a word, "hopla" could also denote weapons held or even...

provided their own equipment. The primary hoplite weapon was a spear

Spear

A spear is a pole weapon consisting of a shaft, usually of wood, with a pointed head.The head may be simply the sharpened end of the shaft itself, as is the case with bamboo spears, or it may be made of a more durable material fastened to the shaft, such as flint, obsidian, iron, steel or...

around 2.4 meters in length called a dory

Dory (spear)

The dory or doru - ie not pronounced like the fish - is a spear that was the chief armament of hoplites in Ancient Greece. The word "dory" is first attested in Homer with the meanings of "wood" and "spear". Homeric heroes hold two dorys...

. Although accounts of its length vary, it is usually now believed to have been seven to nine feet long (~2.1–2.7 m). It was held one-handed, with the other hand holding the hoplite's shield. The spearhead was usually a curved leaf shape, while the rear of the spear had a spike called a sauroter ('lizard-killer') which was used to stand the spear in the ground (hence the name). It was also used as a secondary weapon if the main shaft snapped. This was a common issue especially for soldiers who were involved with the initial clash with the enemy. Despite the snapping of the spear, Hoplites could easily switch to the sauroter without great consequence. The rear ranks also used the secondary end to finish off fallen opponents as the phalanx advanced over them. It is a matter of contention among historians whether the hoplite used the spear overarm or underarm. Held underarm, the thrusts would have been less powerful but under more control, and vice versa. It seems likely that both motions were used, depending on the situation. If attack was called for, an overarm motion was more likely to break through an opponent's defence. The upward thrust is more easily deflected by armour due to its lesser leverage. However, when defending, an underarm carry absorbed more shock and could be 'couched' under the shoulder for maximum stability. It should also be said that an underarm motion would allow more effective combination of the aspis

Aspis

"Aspis" is the generic term for the word shield. The aspis, which is carried by Greek infantry of various periods, is often referred to as a hoplon .According to Diodorus Siculus:-Construction:...

and doru if the shield wall had broken down, while the overarm motion would be more effective when the shield had to be interlocked with those of one's neighbours in the battle-line. Hoplites in the rows behind the lead would almost certainly have made overarm thrusts. The rear ranks held their spears underarm, and raised shields upwards at increasing angles. This was an effective defence against missiles, deflecting their force.

Throughout the hoplite era the standard hoplites' armour went through many cyclical changes. An Archaic hoplite typically wore a bronze

Bronze

Bronze is a metal alloy consisting primarily of copper, usually with tin as the main additive. It is hard and brittle, and it was particularly significant in antiquity, so much so that the Bronze Age was named after the metal...

breastplate

Breastplate

A breastplate is a device worn over the torso to protect it from injury, as an item of religious significance, or as an item of status. A breastplate is sometimes worn by mythological beings as a distinctive item of clothing.- Armour :...

, a bronze helmet

Helmet

A helmet is a form of protective gear worn on the head to protect it from injuries.Ceremonial or symbolic helmets without protective function are sometimes used. The oldest known use of helmets was by Assyrian soldiers in 900BC, who wore thick leather or bronze helmets to protect the head from...

with cheekplates, as well as greave

Greave

A greave is a piece of armour that protects the leg.-Description:...

s and other armour

Armour

Armour or armor is protective covering used to prevent damage from being inflicted to an object, individual or a vehicle through use of direct contact weapons or projectiles, usually during combat, or from damage caused by a potentially dangerous environment or action...

. Later, in the classical period, the breastplate became less common, replaced instead with a mixture of linen padding and hanging strips of leather. Eventually even greaves became less commonly used, although degrees of heavier armour remained, as attested by Xenophon

Xenophon

Xenophon , son of Gryllus, of the deme Erchia of Athens, also known as Xenophon of Athens, was a Greek historian, soldier, mercenary, philosopher and a contemporary and admirer of Socrates...

as late as 401 BC.

Such changes reflected the balancing of mobility with protection, especially as cavalry became more prominent in the Peloponnesian War

Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War, 431 to 404 BC, was an ancient Greek war fought by Athens and its empire against the Peloponnesian League led by Sparta. Historians have traditionally divided the war into three phases...

and the need to combat light troops which were increasingly used to negate the hoplites role as the primary force in battle. Yet bronze armour remained in some form until the end of the hoplite era. Some archaeologists have pointed out bronze armour does not actually provide as much protection from direct blows as more extensive corselet padding, and have suggested its continued use was a matter of status for those who could afford it. Such theories remind us that practicality and cultural preference do not always correlate.

In classical Greek dialect there is, in fact, no word for swordsmen yet hoplites also carried a short sword called a xiphos. The short sword was a secondary weapon, used if the doru was broken or lost. Samples of the xiphos recovered at excavation sites typically were found to be around 2 ft in length. These swords were double sided and could therefore be used in both the swinging and thrusting motion.

Hoplites carried a circular shield called an aspis

Aspis

"Aspis" is the generic term for the word shield. The aspis, which is carried by Greek infantry of various periods, is often referred to as a hoplon .According to Diodorus Siculus:-Construction:...

(often referred to as a hoplon) made from wood and covered in bronze, measuring roughly 1 meter in diameter. It spanned from chin to knee and was very heavy (8–15 kg). This medium-sized shield (and indeed, large for the time) was made possible partly by its dish-like shape, which allowed it to be supported with the rim on the shoulder. This was quite an important feature of the shield especially for the hoplites that remained in the latter ranks. While these soldiers continued to help press forward they did not have the added burden of holding up their shield. But the circular shield was not without its disadvantages. Despite its mobility, protective curve, and double straps the circular shape created gaps in the shield wall at both its top and bottom. These gaps left parts of the hoplite exposed to potentially lethal spear thrusts and were always an area of concern for hoplites controlling the front lines.

Phalangite armament

The sarissaSarissa

The sarissa or sarisa was a 4 to 7 meter long spear used in the ancient Greek and Hellenistic warfare. It was introduced by Philip II of Macedon and was used in the traditional Greek phalanx formation as a replacement for the earlier dory, which was considerably shorter. The phalanxes of Philip...

was the pike used by the Ancient Macedonian army. The actual length of the sarissa is now unknown, but apparently it was twice as long as the doru. This makes it at least 14 feet (~4.3m), but 18 feet (~5.5m) appears more likely. (The cavalry xyston

Xyston

Not to be confused with XystosThe xyston |javelin]]; pointed stick, goad") was a type of a long thrusting lance in ancient Greece. It measured about long and was probably held by the cavalryman with both hands, although the depiction of Alexander the Great's xyston on the Alexander Mosaic in...

was 12.5 feet (~3.8m) by comparison.) The great length of the pike was balanced by a counterweight at the rear end, which also functions as a butt-spike, allowing the sarissa to be planted into the ground. Because of its great length, weight and differing balance, a sarissa was wielded two-handed. This meant that the aspis was no longer a practical defence. Instead, the phalangites strapped a smaller pelte shield (usually reserved for light skirmishers – peltast

Peltast

A peltast was a type of light infantry in Ancient Thrace who often served as skirmishers.-Description:Peltasts carried a crescent-shaped wicker shield called pelte as their main protection, hence their name. According to Aristotle the pelte was rimless and covered in goat or sheep skin...

s) to their left forearm. Although this reduced the shield wall, the extreme length of the spear prevented most enemies from closing, as the pikes of the first three to five ranks could all be brought to bear in front of the front row. In addition, the last 6-18 ranks of soldiers held their spears in the air, making an effective barrier against missiles. This pike had to be held underhand, as the shield would have obscured the soldier's vision had it been held overhead. It would also be very hard to remove a sarissa from anything it stuck in (the earth, shields, and soldiers of the opposition) if it were thrust downwards, due to its length.

Phalanx composition and strength

The basic combat element of the Greek armies was the stichos (meaning "file") or enomotia (meaning "sworn"), usually 8–16 men strong, led by a decadarchos who was assisted by a dimoerites and two decasteroe (sing. decasteros). Four to a maximum of 32 enomotiae (depending on the era in question or the city) were forming a lochos led by a lochagos, who in this way was in command of initially 100 hoplites to a maximum of ca. 500 in the late Hellenistic armies. Here, it has to be noted that the military manuals of Asclepiodotus and Aelian use the term lochos to denote a file in the phalanx. A taxis (moraMora (military unit)

A mora was an ancient Spartan military unit of about a sixth of the Spartan army, at approx. 600 men by modern estimates, although Xenophon places it at 6000. This can be reconciled by the nature of the Spartan army with an organisation based on year classes, with only the younger troops being...

for the Spartans) was the greatest standard hoplitic formation of 500 to 1500 men, led by a strategos

Strategos

Strategos, plural strategoi, is used in Greek to mean "general". In the Hellenistic and Byzantine Empires the term was also used to describe a military governor...

(general). The entire army, a total of several taxeis or morae was led by a generals' council. The commander-in-chief was usually called a polemarchos or a strategos autocrator.

Phalanx front and depth

Hoplite phalanxes usually deployed in ranks of 8 men or more deep; The Macedonian phalanxes were usually 16 men deep, sometimes reported to have been arrayed 32 men deep. There are some notable extremes; at the battles of LeuctraBattle of Leuctra

The Battle of Leuctra was a battle fought on July 6, 371 BC, between the Boeotians led by Thebans and the Spartans along with their allies amidst the post-Corinthian War conflict. The battle took place in the neighbourhood of Leuctra, a village in Boeotia in the territory of Thespiae...

and Mantinea

Battle of Mantinea

Battle of Mantinea may refer to one of three battles fought at Mantinea:*Battle of Mantinea *Battle of Mantinea *Battle of Mantinea...

, the Theban general Epaminondas

Epaminondas

Epaminondas , or Epameinondas, was a Theban general and statesman of the 4th century BC who transformed the Ancient Greek city-state of Thebes, leading it out of Spartan subjugation into a preeminent position in Greek politics...

arranged the left wing of the phalanx into a "hammerhead" of 50 ranks of elite hoplites deep (see below) and when depth was less important, phalanxes just 4 deep are recorded, as at the battle of Marathon.

The phalanx depth could vary depending on the needs of the moment and plans of the general. While the phalanx was in march, an eis bathos formation (loose, meaning literally "in depth") was adopted in order to move more freely and maintain order. This was also the initial battle formation as, in addition, permitted friendly units to pass through either assaulting or retreating. In this status, the phalanx had double depth than the normal and each hoplite had to occupy about 1.8-2m in width (6–7 ft). When enemy infantry was approaching, a rapid switch to the pycne (spelled also pucne) formation (dense or tight formation) was necessary. In that case, each man's space was cut in half (0.9-1m or 3 ft in width) and the formation depth was turning on normal. A yet more dense formation used when the phalanx was to experience extra pressure, intense missile volleys or frontal cavalry charges, was the synaspismos or sunaspismos (ultra tight or locked shields formation). In synaspismos the rank depth was half of the normal and the width each men occupied was as small as 0.45 m (1.5 ft)

Stages of combat

Several stages in hoplite combat can be defined:Ephodos: The hoplites stop singing their paeanes (battle hymns) and move towards the enemy, gradually picking up pace and momentum. In the instants before impact war cries (alalagmoe, sing. alalagmos) would be made. Notable war cries were the Athenian (elelelelef! elelelelef!) and the Macedonian (alalalalai! alalalalai!) alalagmoe.

Krousis: The opposing phalanxes meet each other almost simultaneously along their front. The promachoe (the front-liners) had to be physically and psychologically fit to sustain and survive the clash.

Doratismos: Repeated, rapid spear thrusts in order to disrupt the enemy formation.

Othismos: Literally "pushing" after most spears have been broken, the hoplites begin to push with their large shields and use their secondary weapon, the sword. This could be the longest phase.

Pararrhexis: "Breaching" the opposing phalanx, the enemy formation shatters and the battle ends.

Tactics

City-state

A city-state is an independent or autonomous entity whose territory consists of a city which is not administered as a part of another local government.-Historical city-states:...

s. The usual result was rather identical, inflexible formations pushing against each other until one broke. The potential of the phalanx to achieve something more was demonstrated at Battle of Marathon

Battle of Marathon

The Battle of Marathon took place in 490 BC, during the first Persian invasion of Greece. It was fought between the citizens of Athens, aided by Plataea, and a Persian force commanded by Datis and Artaphernes. It was the culmination of the first attempt by Persia, under King Darius I, to subjugate...

(490 BC). Facing the much larger army of Darius I, the Athenians thinned out their phalanx and consequently lengthened their front, to avoid being outflanked. However, even a reduced-depth phalanx proved unstoppable to the lightly armed Persian infantry. After routing the Persian wings, the hoplites on the Athenian wings wheeled inwards, destroying the elite troop at the Persian centre, resulting in a crushing victory for Athens. Throughout the Greco-Persian Wars

Greco-Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire of Persia and city-states of the Hellenic world that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of the Greeks and the enormous empire of the Persians began when Cyrus...

the hoplite phalanx was to prove superior to the Persian infantry (e.g. The battles of Thermopylae

Battle of Thermopylae

The Battle of Thermopylae was fought between an alliance of Greek city-states, led by King Leonidas of Sparta, and the Persian Empire of Xerxes I over the course of three days, during the second Persian invasion of Greece. It took place simultaneously with the naval battle at Artemisium, in August...

and Plataea

Battle of Plataea

The Battle of Plataea was the final land battle during the second Persian invasion of Greece. It took place in 479 BC near the city of Plataea in Boeotia, and was fought between an alliance of the Greek city-states, including Sparta, Athens, Corinth and Megara, and the Persian Empire of Xerxes...

).

Perhaps the most prominent example of the phalanx's evolution was the oblique

Oblique order

The Oblique Order is a military tactic where an attacking army focuses its forces to attack a single enemy flank. The force commander concentrates the majority of his strength on one flank and uses the remainder to fix the enemy line. This allows a commander with weaker or equal forces to...

advance, made famous in the Battle of Leuctra

Battle of Leuctra

The Battle of Leuctra was a battle fought on July 6, 371 BC, between the Boeotians led by Thebans and the Spartans along with their allies amidst the post-Corinthian War conflict. The battle took place in the neighbourhood of Leuctra, a village in Boeotia in the territory of Thespiae...

. There, the Theban general Epaminondas

Epaminondas

Epaminondas , or Epameinondas, was a Theban general and statesman of the 4th century BC who transformed the Ancient Greek city-state of Thebes, leading it out of Spartan subjugation into a preeminent position in Greek politics...

thinned out the right flank and centre of his phalanx, and deepened his left flank to an unheard-of 50 men deep. In doing so, Epaminondas reversed the convention by which the right flank of the phalanx was strongest. This allowed the Thebans to assault in strength the elite Spartan troops on the right flank of the opposing phalanx. Meanwhile, the centre and right flank of the Theban line were echeloned back, from the opposing phalanx, keeping the weakened parts of the formation from being engaged. Once the Spartan right had been routed by the Theban left, the remainder of the Spartan line also broke. Thus by localising the attacking power of the hoplites, Epaminondas was able to defeat an enemy previously thought invincible.

Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon "friend" + ἵππος "horse" — transliterated ; 382 – 336 BC), was a king of Macedon from 359 BC until his assassination in 336 BC. He was the father of Alexander the Great and Philip III.-Biography:...

spent several years in Thebes as a hostage, and paid attention to Epaminondas' innovations. Upon return to his homeland, he raised a revolutionary new infantry force, which was to change the face of the Greek world. Phillip's phalangites were the first force of professional soldiers seen in Ancient Greece apart from Sparta. They were armed with longer spears and were drilled more thoroughly in more evolved, complicated tactics and manoeuvres. More importantly, though, Phillip's phalanx was part of a multi-faceted, combined force that included a variety of skirmisher

Skirmisher

Skirmishers are infantry or cavalry soldiers stationed ahead or alongside a larger body of friendly troops. They are usually placed in a skirmish line to harass the enemy.-Pre-modern:...

s and cavalry

Cavalry

Cavalry or horsemen were soldiers or warriors who fought mounted on horseback. Cavalry were historically the third oldest and the most mobile of the combat arms...

, most notably the famous Companion cavalry

Companion cavalry

The Companions were the elite cavalry of the Macedonian army from the time of king Philip II of Macedon and reached the most prestige under Alexander the Great, and have been regarded as the best cavalry in the ancient world and the first shock cavalry...

. The Macedonian phalanx now was used to pin the centre of the enemy line, while cavalry and more mobile infantry struck at the foe's flanks. Its supremacy over the more static armies fielded by the Greek city-states was shown at the Battle of Chaeronea

Battle of Chaeronea (338 BC)

The Battle of Chaeronea was fought in 338 BC, near the city of Chaeronea in Boeotia, between the forces of Philip II of Macedon and an alliance of Greek city-states...

, where Philip II's army crushed the allied Theban and Athenian phalanxes.

Weaknesses

The Hoplite Phalanx was weakest when facing an enemy fielding lighter and more flexible troops without its own such supporting troops. An example of this would be the Battle of LechaeumBattle of Lechaeum

The Battle of Lechaeum was an Athenian victory in the Corinthian War. In the battle, the Athenian general Iphicrates took advantage of the fact that a Spartan hoplite regiment operating near Corinth was moving in the open without the protection of any missile throwing troops. He decided to ambush...

, where an Athenian contingent led by Iphicrates

Iphicrates

Iphicrates was an Athenian general, the son of a shoemaker, who flourished in the earlier half of the 4th century BC....

routed an entire Sparta

Sparta

Sparta or Lacedaemon, was a prominent city-state in ancient Greece, situated on the banks of the River Eurotas in Laconia, in south-eastern Peloponnese. It emerged as a political entity around the 10th century BC, when the invading Dorians subjugated the local, non-Dorian population. From c...

n mora (a unit of anywhere from 500 to 900 hoplites). The Athenian force had a considerable proportion of light missile troops armed with javelin

Javelin throw

The javelin throw is a track and field athletics throwing event where the object to be thrown is the javelin, a spear approximately 2.5 metres in length. Javelin is an event of both the men's decathlon and the women's heptathlon...

s and bows

Bow (weapon)

The bow and arrow is a projectile weapon system that predates recorded history and is common to most cultures.-Description:A bow is a flexible arc that shoots aerodynamic projectiles by means of elastic energy. Essentially, the bow is a form of spring powered by a string or cord...

which wore down the Spartans with repeated attacks, causing disarray in the Spartan ranks and an eventual rout

Rout

A rout is commonly defined as a chaotic and disorderly retreat or withdrawal of troops from a battlefield, resulting in the victory of the opposing party, or following defeat, a collapse of discipline, or poor morale. A routed army often degenerates into a sense of "every man for himself" as the...

when they spotted Athenian heavy infantry reinforcements trying to flank them by boat.

The Macedonian Phalanx had weaknesses similar to its hoplitic predecessor. Theoretically indestructible from the front, its flanks and rear were very vulnerable, and once engaged it could probably not easily disengage or redeploy to face a threat from those directions. Thus, a phalanx facing non-phalangite formations required some sort of protection on its flanks—lighter or at least more mobile infantry, cavalry, etc. This was shown at the Battle of Magnesia

Battle of Magnesia

The Battle of Magnesia was fought in 190 BC near Magnesia ad Sipylum, on the plains of Lydia , between the Romans, led by the consul Lucius Cornelius Scipio and his brother, the famed general Scipio Africanus, with their ally Eumenes II of Pergamum against the army of Antiochus III the Great of the...

, where, once the Seleucid supporting infantry elements were driven off, the phalanx was helpless against its Roman opponents.

The Macedonian phalanx

Macedonian phalanx

The Macedonian phalanx is an infantry formation developed by Philip II and used by his son Alexander the Great to conquer the Persian Empire and other armies...

could also lose its cohesion without proper coordination and/or while moving through broken terrain; doing so could create gaps between individual blocks/syntagmata, or could prevent a solid front within those sub-units as well, causing other sections of the line to bunch up. In this event, as in the battles of Cynoscephalae

Battle of Cynoscephalae

The Battle of Cynoscephalae was an encounter battle fought in Thessaly in 197 BC between the Roman army, led by Titus Quinctius Flamininus, and the Antigonid dynasty of Macedon, led by Philip V.- Prelude :...

and Pydna

Battle of Pydna

The Battle of Pydna in 168 BC between Rome and the Macedonian Antigonid dynasty saw the further ascendancy of Rome in the Hellenic/Hellenistic world and the end of the Antigonid line of kings, whose power traced back to Alexander the Great.Paul K...

, the phalanx became vulnerable to attacks by more flexible units—such as Roman legionary centuries, which were able to avoid the sarissae and engage in hand-to-hand combat with the phalangites.

Another important area that must be considered concerns the psychological tendencies of the hoplites. Because the strength of a phalanx was dependent on the ability of the hoplites to maintain their frontline it was crucial that a phalanx be able to quickly and efficiently replace fallen soldiers in the frontal ranks. If a phalanx failed to do this in a structured manner the opposing phalanx would have an opportunity to breach the line which, many times, would lead to a quick defeat. This then implies that the hoplites ranks closer to the front must be mentally prepared to replace their fallen comrade and adapt to his new position without disrupting the structure of the frontline.

Finally, most of the phalanx-centric armies tended to lack supporting echelons behind the main line of battle. This meant that breaking through the line of battle or compromising one of its flanks often ensured victory.

Decline

After reaching its zenith in the conquests of Alexander the Great, the phalanx as a military formation began a slow decline, mirrored by the decline in the Macedonian successor states themselves. The combined arms tactics used by Alexander and his father were gradually replaced by a return to the simpler frontal charge tactics of the hoplite phalanx.The decline of the diadochi