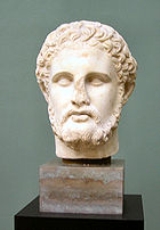

Philip II of Macedon

Encyclopedia

Philip II of Macedon was a king (basileus

) of Macedon from 359 BC until his assassination in 336 BC. He was the father of Alexander the Great and Philip III

.

and Eurydice I. In his youth, (c. 368–365 BC) Philip was held as a hostage in Thebes

, which was the leading city of Greece

during the Theban hegemony

. While a captive there, Philip received a military and diplomatic education from Epaminondas

, became eromenos of Pelopidas

, and lived with Pammenes

, who was an enthusiastic advocate of the Sacred Band of Thebes

. In 364 BC, Philip returned to Macedon. The deaths of Philip's elder brothers, King Alexander II

and Perdiccas III

, allowed him to take the throne in 359 BC. Originally appointed regent

for his infant nephew Amyntas IV

, who was the son of Perdiccas III, Philip managed to take the kingdom for himself that same year.

Philip's military skills and expansionist vision of Macedonian greatness brought him early success. He first had to re-establish a situation which had been greatly worsened by the defeat against the Illyrians

in which King Perdiccas himself had died. The Paionia

ns and the Thracians

had sacked and invaded the eastern regions of the country, while the Athenians

had landed, at Methoni

on the coast, a contingent under a Macedonian pretender called Argeus

. Using diplomacy, Philip pushed back Paionians and Thracians promising tributes, and crushed the 3,000 Athenian hoplite

s (359). Momentarily free from his opponents, he concentrated on strengthening his internal position and, above all, his army. His most important innovation was doubtless the introduction of the phalanx

infantry corps, armed with the famous sarissa

, an exceedingly long spear, at the time the most important army corps in Macedonia.

Philip had married Audata

, great-granddaughter of the Illyrian king of Dardania, Bardyllis

. However, this did not prevent him from marching against them in 358 and crushing them in a ferocious battle in which some 7,000 Illyrians died (357). By this move, Philip established his authority inland as far as Lake Ohrid

and the favour of the Epirotes.

He agreed with the Athenians, who had been so far unable to conquer Amphipolis

, which commanded the gold mines

of Mount Pangaion, to lease it to them after its conquest, in exchange for Pydna

(lost by Macedon in 363). However, after conquering Amphipolis, he kept both the cities (357). As Athens declared war against him, he allied with the Chalkidian League

of Olynthus

. He subsequently conquered Potidaea

, this time keeping his word and ceding it to the League in 356. One year before Philip had married the Epirote

princess Olympias

, who was the daughter of the king of the Molossians

.

In 356 BC, Philip also conquered the town of Crenides

and changed its name to Philippi

: he established a powerful garrison there to control its mines, which granted him much of the gold later used for his campaigns. In the meantime, his general Parmenion

defeated the Illyrians again. Also in 356 Alexander was born, and Philip's race horse won in the Olympic Games. In 355–354 he besieged Methone

, the last city on the Thermaic Gulf

controlled by Athens. During the siege, Philip lost an eye. Despite the arrival of two Athenians fleets, the city fell in 354. Philip also attacked Abdera

and Maronea, on the Thracian

seaboard (354–353).

Involved in the Third Sacred War

Involved in the Third Sacred War

which had broken out in Greece, in the summer of 353 he invaded Thessaly

, defeating 7,000 Phocians

under the brother of Onomarchus

. The latter however defeated Philip in the two succeeding battles. Philip returned to Thessaly the next summer, this time with an army of 20,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry including all Thessalian troops. In the Battle of Crocus Field

6,000 Phocians fell, while 3,000 were taken as prisoners and later drowned. This battle granted Philip an immense prestige, as well as the free acquisition of Pherae

. Philip was also tagus of Thessaly, and he claimed as his own Magnesia

, with the important harbour of Pagasae

. Philip did not attempt to advance into Central Greece

because the Athenians, unable to arrive in time to defend Pagasae, had occupied Thermopylae

.

Hostilities with Athens did not yet take place, but Athens was threatened by the Macedonian party which Philip's gold created in Euboea

. From 352 to 346 BC, Philip did not again come south. He was active in completing the subjugation of the Balkan

hill-country to the west and north, and in reducing the Greek cities of the coast as far as the Hebrus

. To the chief of these coastal cities, Olynthus

, Philip continued to profess friendship until its neighboring cities were in his hands.

In 349 BC, Philip started the siege of Olynthus, which, apart from its strategic position, housed his relatives Arrhidaeus and Menelaus

In 349 BC, Philip started the siege of Olynthus, which, apart from its strategic position, housed his relatives Arrhidaeus and Menelaus

, pretenders to the Macedonian throne. Olynthus had at first allied itself with Philip, but later shifted its allegiance to Athens. The latter, however, did nothing to help the city, its expeditions held back by a revolt in Euboea (probably paid by Philip's gold). The Macedonian

king finally took Olynthus in 348 BC and razed the city to the ground. The same fate was inflicted on other cities of the Chalcidian peninsula. Macedon and the regions adjoining it having now been securely consolidated, Philip celebrated his Olympic Games

at Dium

. In 347 BC, Philip advanced to the conquest of the eastern districts about Hebrus, and compelled the submission of the Thracian

prince Cersobleptes

. In 346 BC, he intervened effectively in the war between Thebes and the Phocians, but his wars with Athens continued intermittently. However, Athens had made overtures for peace, and when Philip again moved south, peace was sworn in Thessaly. With key Greek city-states in submission, Philip turned to Sparta

; he sent them a message, "You are advised to submit without further delay, for if I bring my army into your land, I will destroy your farms, slay your people, and raze your city." Their laconic reply: "If". Philip and Alexander would both leave them alone. Later, the Macedonian arms were carried across Epirus to the Adriatic Sea

.

In 345 B.C., Philip conducted a hard-fought campaign against the Ardiaioi (Ardiaei), under their king Pluratus, during which he was seriously wounded by an Ardian soldier in the lower right leg.

In 342 BC, Philip led a great military expedition north against the Scythians, conquering the Thracian fortified settlement Eumolpia to give it his name, Philippopolis (modern Plovdiv

).

In 340 BC, Philip started the siege of Perinthus

. Philip began another siege in 339 of the city of Byzantium

. After unsuccessful sieges of both cities, Philip's influence all over Greece was compromised. However, he successfully reasserted his authority in the Aegean

by defeating an alliance of Thebans and Athenians at the Battle of Chaeronea

in 338 BC, while in the same year, Philip destroyed Amfissa

because the residents had illegally cultivated part of the Crisaian plain which belonged to Delphi

. Philip created and led the League of Corinth

in 337 BC. Members of the League agreed never to wage war against each other, unless it was to suppress revolution

. Philip was elected as leader (hegemon

) of the army of invasion against the Persian Empire

. In 336 BC, when the invasion of Persia was in its very early stage, Philip was assassinated, and was succeeded on the throne of Macedon by his son Alexander III.

The murder occurred during October of 336 BC, at Aegae

The murder occurred during October of 336 BC, at Aegae

, the ancient capital of the kingdom of Macedon. The court had gathered there for the celebration of the marriage between Alexander I of Epirus

and Philip's daughter, by his fourth wife Olympias

, Cleopatra. While the king was entering unprotected into the town's theater (highlighting his approachability to the Greek diplomats present), he was killed by Pausanias of Orestis, one of his seven bodyguards. The assassin immediately tried to escape and reach his associates who were waiting for him with horses at the entrance of Aegae. He was pursued by three of Philip's bodyguards and died by their hands.

The reasons for Pausanias' assassination of Philip are difficult to fully expound, since there was controversy already among ancient historians. The only contemporary account in our possession is that of Aristotle

, who states rather tersely that Philip was killed because Pausanias had been offended by the followers of Attalus

, the king's father-in-law.

Fifty years later, the historian Cleitarchus

expanded and embellished the story. Centuries later, this version was to be narrated by Diodorus Siculus

and all the historians who used Cleitarchus. In the sixteenth book of Diodorus' history, Pausanias had been a lover of Philip, but became jealous when Philip turned his attention to a younger man, also called Pausanias. His taunting of the new lover caused the youth to throw away his life, which turned his friend, Attalus, against Pausanias. Attalus took his revenge by inviting Pausanias to dinner, getting him drunk, then subjecting him to sexual assault.

When Pausanias complained to Philip the king felt unable to chastise Attalus, as he was about to send him to Asia with Parmenion

, to establish a bridgehead for his planned invasion. He also married Attalus's niece, or daughter, Eurydice

. Rather than offend Attalus, Philip attempted to mollify Pausanius by elevating him within the bodyguard. Pausanias' desire for revenge seems to have turned towards the man who had failed to avenge his damaged honour; so he planned to kill Philip, and some time after the alleged rape, while Attalus was already in Asia fighting the Persians, put his plan in action.

Other historians (e.g., Justin 9.7) suggested that Alexander and/or his mother Olympias

were at least privy to the intrigue, if not themselves instigators. The latter seems to have been anything but discreet in manifesting her gratitude to Pausanias, according to Justin's report: he says that the same night of her return from exile she placed a crown on the assassin's corpse and erected a tumulus

to his memory, ordering annual sacrifices to the memory of Pausanias.

Many modern historians have observed that all the accounts are improbable. In the case of Pausanias, the stated motive of the crime hardly seems adequate. On the other hand, the implication of Alexander and Olympias seems specious: to act as they did would have required brazen effrontery in the face of a military machine personally loyal to Philip. What appears to be recorded in this are the natural suspicions that fell on the chief beneficiaries of the murder; their actions after the murder, however sympathetic they might appear (if actual), cannot prove their guilt in the deed itself. Further convoluting the case is the possible role of propaganda in the surviving accounts: Attalus was executed in Alexander's consolidation of power after the murder; one might wonder if his enrollment among the conspirators was not for the effect of introducing political expediency in an otherwise messy purge (Attalus had publicly declared his hope that Alexander would not succeed Philip, but rather that a son of his own niece Eurydice, recently married to Philip and brutally murdered by Olympias after Philip's death, would gain the throne of Macedon).

Many modern historians have observed that all the accounts are improbable. In the case of Pausanias, the stated motive of the crime hardly seems adequate. On the other hand, the implication of Alexander and Olympias seems specious: to act as they did would have required brazen effrontery in the face of a military machine personally loyal to Philip. What appears to be recorded in this are the natural suspicions that fell on the chief beneficiaries of the murder; their actions after the murder, however sympathetic they might appear (if actual), cannot prove their guilt in the deed itself. Further convoluting the case is the possible role of propaganda in the surviving accounts: Attalus was executed in Alexander's consolidation of power after the murder; one might wonder if his enrollment among the conspirators was not for the effect of introducing political expediency in an otherwise messy purge (Attalus had publicly declared his hope that Alexander would not succeed Philip, but rather that a son of his own niece Eurydice, recently married to Philip and brutally murdered by Olympias after Philip's death, would gain the throne of Macedon).

, 13.557b–e:

On November 8, 1977, Greek archaeologist Manolis Andronikos

On November 8, 1977, Greek archaeologist Manolis Andronikos

found, among other royal tombs, an unopened tomb at Vergina

in the Greek prefecture of Imathia

. The finds from this tomb were later included in the travelling exhibit The Search for Alexander displayed at four cities in the United States

from 1980 to 1982. It is generally accepted that the site at Vergina

was the burial site of the kings of Macedon, including Philip, but the debate about the unopened tomb is ongoing among archaeologists.

The initial suggestion that the tomb might belong to Philip II was indicated by the greaves, one of which indicated that the owner had a leg injury which distorted the natural alignment of the tibia (Philip II was recorded as having broken his tibia). What is viewed as possible proof that the tomb indeed did belong to Philip II and that the surviving bone fragments are in fact the body of Philip II comes from forensic reconstruction of the skull of Philip II by the wax casting and reconstruction of the skull which shows the damage to the right eye caused by the penetration of an object (historically recorded to be an arrow).

Eugene Borza and others have suggested that the unopened tomb actually belonged to Philip's son, Philip Arrhidaeus

, and Philip was probably buried in the simpler adjacent tomb, which had been looted in antiquity. Disputations often relied on contradictions between "the body" or "skeleton" of Philip II and reliable historical accounts of his life (and injuries), as well as analyses of the paintings, pottery, and other artifacts found there.

Musgrave, et al. (2010) showed that there is no valid evidence Arrhidaeus could have been buried in the unopened tomb, hence those who made those claims, like Borza, Palagia and Bartsiokas, had actually misunderstood certain scientific facts which led them to invalid conclusions. Musgrave's study of the bones of Tomb II of Vergina found that the cranium of the male was deformed possibly by a trauma, a finding that is consistent with the history of Philip II.

According to a new study published in the April 21 edition of the journal Science, the style of the artifacts of the royal tomb date 317 B.C., a generation after Philip II's assassinations. Moreover, according to paleoanthropologist Antonis Bartsiokas of the Anaximandrian Institute of Human Evolution at the Democritus University of Thrace in Voula, Greece, and assistant professor at the Democritus who used a technique called macrophotography to study the skeleton in meticulous detail, the features identified by Musgrave, Prag, and Neave are simply normal anatomical quirks, accentuated by the effects of cremation and a poor reassembly of the remains. "The bump, for example," says Bartsiokas, "is part of the opening in the skull's frontal bone called the supraorbital notch, through which a bundle of nerves and blood vessels pass." Most people can feel this notch by pressing their fingers underneath the ridge of bone beneath the eyebrow. The bone at the site of the "injury" is simply the frontal notch and also shows no signs of healing in the bone fabric, a problem for Bartsiokas given that the wound was inflicted 18 years before Philip II's death.

at Vergina

in Greek Macedonia (the ancient city of Aegae

– Αἰγαί) is thought to have been dedicated to the worship of the family of Alexander the Great and may have housed the cult statue of Philip. It is probable that he was regarded as a hero or deified on his death. Though the Macedonians did not consider Philip a god, he did receive other forms of recognition by the Greeks, such as at Eresos

(altar to Zeus Philippeios), Ephesos (his statue was placed in the temple of Artemis

), and Olympia, where the Philippeion

was built.

Isocrates once wrote to Philip that if he defeated Persia, there was nothing left for him to do but to become a god; and Demades

proposed that Philip be regarded as the thirteenth god; however, there is no clear evidence that Philip was raised to the divine status accorded his son Alexander.

Basileus

Basileus is a Greek term and title that has signified various types of monarchs in history. It is perhaps best known in English as a title used by the Byzantine Emperors, but also has a longer history of use for persons of authority and sovereigns in ancient Greece, as well as for the kings of...

) of Macedon from 359 BC until his assassination in 336 BC. He was the father of Alexander the Great and Philip III

Philip III of Macedon

Philip III Arrhidaeus was the king of Macedonia from after June 11, 323 BC until his death. He was a son of King Philip II of Macedonia by Philinna of Larissa, allegedly a Thessalian dancer, and a half-brother of Alexander the Great...

.

Biography

Philip was the youngest son of the king Amyntas IIIAmyntas III of Macedon

Amyntas III son of Arrhidaeus and father of Philip II, was king of Macedon in 393 BC, and again from 392 to 370 BC. He was also a paternal grandfather of Alexander the Great....

and Eurydice I. In his youth, (c. 368–365 BC) Philip was held as a hostage in Thebes

Thebes, Greece

Thebes is a city in Greece, situated to the north of the Cithaeron range, which divides Boeotia from Attica, and on the southern edge of the Boeotian plain. It played an important role in Greek myth, as the site of the stories of Cadmus, Oedipus, Dionysus and others...

, which was the leading city of Greece

Greece

Greece , officially the Hellenic Republic , and historically Hellas or the Republic of Greece in English, is a country in southeastern Europe....

during the Theban hegemony

Theban hegemony

The Theban Hegemony lasted from the Theban victory over the Spartans at Leuctra in 371 BC to their defeat of a coalition of Peloponnesian armies at Mantinea in 362 BC, though Thebes sought to maintain its position until finally eclipsed by the rising power of Macedon in 346 BC.Externally, the way...

. While a captive there, Philip received a military and diplomatic education from Epaminondas

Epaminondas

Epaminondas , or Epameinondas, was a Theban general and statesman of the 4th century BC who transformed the Ancient Greek city-state of Thebes, leading it out of Spartan subjugation into a preeminent position in Greek politics...

, became eromenos of Pelopidas

Pelopidas

Pelopidas was an important Theban statesman and general in Greece.-Athlete and warrior:He was a member of a distinguished family, and possessed great wealth which he expended on his friends, while content to lead the life of an athlete...

, and lived with Pammenes

Pammenes of Thebes

Pammenes was a Theban general of considerable celebrity. He was connected with Epaminondas by political and friendly ties. When Philip, the future king of Macedonia, was sent as hostage to Thebes, he was placed under the care of Pammenes...

, who was an enthusiastic advocate of the Sacred Band of Thebes

Sacred Band of Thebes

The Sacred Band of Thebes was a troop of picked soldiers, consisting of 150 male couples which formed the elite force of the Theban army in the 4th century BC. It was organised by the Theban commander Gorgidas in 378 BC and played a crucial role in the Battle of Leuctra...

. In 364 BC, Philip returned to Macedon. The deaths of Philip's elder brothers, King Alexander II

Alexander II of Macedon

Alexander II was king of Macedon from 371 – 369 BC, following the death of his father Amyntas VI. He was the eldest of the three sons of Amyntas and Eurydice....

and Perdiccas III

Perdiccas III of Macedon

Perdiccas III was king of Macedonia from 368 to 359 BC, succeeding his brother Alexander II.Son of Amyntas III and Eurydice, he was underage when Alexander II was killed by Ptolemy of Aloros, who then ruled as regent. In 365, Perdiccas killed Ptolemy and assumed government.Of the reign of...

, allowed him to take the throne in 359 BC. Originally appointed regent

Regent

A regent, from the Latin regens "one who reigns", is a person selected to act as head of state because the ruler is a minor, not present, or debilitated. Currently there are only two ruling Regencies in the world, sovereign Liechtenstein and the Malaysian constitutive state of Terengganu...

for his infant nephew Amyntas IV

Amyntas IV of Macedon

Amyntas IV was a titular king of Macedonia in 359 BC and member of the Argead dynasty.- Biography :Amyntas was a son of King Perdiccas III of Macedon. He was born in about 365 BC. After his father's death in 359 BC he became king, but he was only an infant. Philip II of Macedon, Perdiccas'...

, who was the son of Perdiccas III, Philip managed to take the kingdom for himself that same year.

Philip's military skills and expansionist vision of Macedonian greatness brought him early success. He first had to re-establish a situation which had been greatly worsened by the defeat against the Illyrians

Illyrians

The Illyrians were a group of tribes who inhabited part of the western Balkans in antiquity and the south-eastern coasts of the Italian peninsula...

in which King Perdiccas himself had died. The Paionia

Paionia

In ancient geography, Paeonia or Paionia was the land of the Paeonians . The exact original boundaries of Paeonia, like the early history of its inhabitants, are very obscure, but it is believed that they lay in the region of Thrace...

ns and the Thracians

Thracians

The ancient Thracians were a group of Indo-European tribes inhabiting areas including Thrace in Southeastern Europe. They spoke the Thracian language – a scarcely attested branch of the Indo-European language family...

had sacked and invaded the eastern regions of the country, while the Athenians

Athens

Athens , is the capital and largest city of Greece. Athens dominates the Attica region and is one of the world's oldest cities, as its recorded history spans around 3,400 years. Classical Athens was a powerful city-state...

had landed, at Methoni

Methoni, Pieria

Methoni is a village and a former municipality in Pieria regional unit, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Pydna-Kolindros, of which it is a municipal unit...

on the coast, a contingent under a Macedonian pretender called Argeus

Argeus

-Greek mythology:* Argeus * Argeus, a surname of Pan and Aristaeus* Argeus, one of the sons of Phineus and Danaë, the other being Argus* Argeus, son of Deiphontes and Hyrnetho* Argeus, one of the Niobids...

. Using diplomacy, Philip pushed back Paionians and Thracians promising tributes, and crushed the 3,000 Athenian hoplite

Hoplite

A hoplite was a citizen-soldier of the Ancient Greek city-states. Hoplites were primarily armed as spearmen and fought in a phalanx formation. The word "hoplite" derives from "hoplon" , the type of the shield used by the soldiers, although, as a word, "hopla" could also denote weapons held or even...

s (359). Momentarily free from his opponents, he concentrated on strengthening his internal position and, above all, his army. His most important innovation was doubtless the introduction of the phalanx

Phalanx formation

The phalanx is a rectangular mass military formation, usually composed entirely of heavy infantry armed with spears, pikes, sarissas, or similar weapons...

infantry corps, armed with the famous sarissa

Sarissa

The sarissa or sarisa was a 4 to 7 meter long spear used in the ancient Greek and Hellenistic warfare. It was introduced by Philip II of Macedon and was used in the traditional Greek phalanx formation as a replacement for the earlier dory, which was considerably shorter. The phalanxes of Philip...

, an exceedingly long spear, at the time the most important army corps in Macedonia.

Philip had married Audata

Audata

Audata was an Illyrian princess and later a Macedonian queen when she married Philip II of Macedon in 359 BC. She was the daughter or niece daughter of Bardyllis, the Illyrian king of the Dardanian State...

, great-granddaughter of the Illyrian king of Dardania, Bardyllis

Bardyllis

Bardyllis was a king of the Dardanian Kingdom and probably its founder.Bardyllis created one of the most powerful Illyrian states, that of the Dardanians...

. However, this did not prevent him from marching against them in 358 and crushing them in a ferocious battle in which some 7,000 Illyrians died (357). By this move, Philip established his authority inland as far as Lake Ohrid

Lake Ohrid

Lake Ohrid straddles the mountainous border between the southwestern Macedonia and eastern Albania. It is one of Europe's deepest and oldest lakes, preserving a unique aquatic ecosystem with more than 200 endemic species that is of worldwide importance...

and the favour of the Epirotes.

He agreed with the Athenians, who had been so far unable to conquer Amphipolis

Amphipolis

Amphipolis was an ancient Greek city in the region once inhabited by the Edoni people in the present-day region of Central Macedonia. It was built on a raised plateau overlooking the east bank of the river Strymon where it emerged from Lake Cercinitis, about 3 m. from the Aegean Sea. Founded in...

, which commanded the gold mines

Gold mining

Gold mining is the removal of gold from the ground. There are several techniques and processes by which gold may be extracted from the earth.-History:...

of Mount Pangaion, to lease it to them after its conquest, in exchange for Pydna

Pydna

Pydna was a Greek city in ancient Macedon, the most important in Pieria. Modern Pydna is a small town and a former municipality in the northeastern part of Pieria regional unit, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Pydna-Kolindros, of which it is a...

(lost by Macedon in 363). However, after conquering Amphipolis, he kept both the cities (357). As Athens declared war against him, he allied with the Chalkidian League

Chalkidian League

The Chalkidian League was a federal state that existed on the shores of the north west Aegean from around 430 BCE until it was destroyed by Philip II of Macedon in 348 BCE.-History:...

of Olynthus

Olynthus

Olynthus was an ancient city of Chalcidice, built mostly on two flat-topped hills 30–40m in height, in a fertile plain at the head of the Gulf of Torone, near the neck of the peninsula of Pallene, about 2.5 kilometers from the sea, and about 60 stadia Olynthus was an ancient city of...

. He subsequently conquered Potidaea

Potidaea

Potidaea was a colony founded by the Corinthians around 600 BC in the narrowest point of the peninsula of Pallene, the westernmost of three peninsulas at the southern end of Chalcidice in northern Greece....

, this time keeping his word and ceding it to the League in 356. One year before Philip had married the Epirote

Epirus

The name Epirus, from the Greek "Ήπειρος" meaning continent may refer to:-Geographical:* Epirus - a historical and geographical region of the southwestern Balkans, straddling modern Greece and Albania...

princess Olympias

Olympias

Olympias was a Greek princess of Epirus, daughter of king Neoptolemus I of Epirus, the fourth wife of the king of Macedonia, Philip II, and mother of Alexander the Great...

, who was the daughter of the king of the Molossians

Molossians

The Molossians were an ancient Greek tribe that inhabited the region of Epirus since the Mycenaean era. On their northeast frontier they had the Chaonians and to their southern frontier the kingdom of the Thesprotians, to their north were the Illyrians. The Molossians were part of the League of...

.

In 356 BC, Philip also conquered the town of Crenides

Krinides

Krinides or Crenides is a town and an ancient site that includes the archaeological site of Philippi in the Kavala Prefecture in eastern Macedonia. Krinides is the seat of the municipality of Filippoi south of the Pangaion hills...

and changed its name to Philippi

Philippi

Philippi was a city in eastern Macedonia, established by Philip II in 356 BC and abandoned in the 14th century after the Ottoman conquest...

: he established a powerful garrison there to control its mines, which granted him much of the gold later used for his campaigns. In the meantime, his general Parmenion

Parmenion

Parmenion was a Macedonian general in the service of Philip II of Macedon and Alexander the Great, murdered on a suspected false charge of treason....

defeated the Illyrians again. Also in 356 Alexander was born, and Philip's race horse won in the Olympic Games. In 355–354 he besieged Methone

Methoni, Pieria

Methoni is a village and a former municipality in Pieria regional unit, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Pydna-Kolindros, of which it is a municipal unit...

, the last city on the Thermaic Gulf

Thermaic Gulf

The Thermaic Gulf is a gulf of the Aegean Sea located immediately south of Thessaloniki, east of Pieria and Imathia, and west of Chalkidiki . It was named after the ancient town of Therma, which was situated on the northeast coast of the gulf...

controlled by Athens. During the siege, Philip lost an eye. Despite the arrival of two Athenians fleets, the city fell in 354. Philip also attacked Abdera

Abdera, Thrace

Abdera was a city-state on the coast of Thrace 17 km east-northeast of the mouth of the Nestos, and almost opposite Thasos. The site now lies in the Xanthi peripheral unit of modern Greece. The municipality of Abdera, or Ávdira , has 18,573 inhabitants...

and Maronea, on the Thracian

Thrace

Thrace is a historical and geographic area in southeast Europe. As a geographical concept, Thrace designates a region bounded by the Balkan Mountains on the north, Rhodope Mountains and the Aegean Sea on the south, and by the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara on the east...

seaboard (354–353).

Third Sacred War

The Third Sacred War was fought between the forces of the Delphic Amphictyonic League, principally represented by Thebes, and latterly by Philip II of Macedon, and the Phocians...

which had broken out in Greece, in the summer of 353 he invaded Thessaly

Thessaly

Thessaly is a traditional geographical region and an administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, Thessaly was known as Aeolia, and appears thus in Homer's Odyssey....

, defeating 7,000 Phocians

Phocis

Phocis is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the administrative region of Central Greece. It stretches from the western mountainsides of Parnassus on the east to the mountain range of Vardousia on the west, upon the Gulf of Corinth...

under the brother of Onomarchus

Onomarchus

Onomarchus was general of the Phocians in the Third Sacred War, brother of Philomelus and son of Theotimus.Onomarchus commanded a division of the Phocian army under Philomelus in the action at Tithorea, in which Philomelus perished. After the battle Onomarchus gathered the remains of the Phocian...

. The latter however defeated Philip in the two succeeding battles. Philip returned to Thessaly the next summer, this time with an army of 20,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry including all Thessalian troops. In the Battle of Crocus Field

Battle of Crocus Field

The Battle of Crocus Field was a battle in the Third Sacred War, fought between the armies of Phocis, under Onomarchos, and the combined Thessalian and Macedonian army under Philip II of Macedon. In the bloodiest battle recorded in Ancient Greek history, the Phocians were decisively defeated by...

6,000 Phocians fell, while 3,000 were taken as prisoners and later drowned. This battle granted Philip an immense prestige, as well as the free acquisition of Pherae

Pherae

Pherae was an ancient Greek town in southeastern Thessaly. It bordered Lake Boebeïs. In mythology, it was the home of King Admetus, whose wife, Alcestis, Heracles went into Hades to rescue. In history, it was more famous as the home of the fourth-century B.C...

. Philip was also tagus of Thessaly, and he claimed as his own Magnesia

Magnesia Prefecture

Magnesia Prefecture was one of the prefectures of Greece. Its capital was Volos. It was established in 1899 from the Larissa Prefecture. The prefecture was disbanded on 1 January 2011 by the Kallikratis programme, and split into the peripheral units of Magnesia and the Sporades.The toponym is...

, with the important harbour of Pagasae

Pagasae

Pagasae was a coastal city in ancient Magnesia , now a suburb of the modern city of Volos. It flourished in the 400s and 300s BC. The only usable harbor in Thessaly was located on the Gulf of Pagasae, as it was known in antiquity...

. Philip did not attempt to advance into Central Greece

Central Greece

Continental Greece or Central Greece , colloquially known as Roúmeli , is a geographical region of Greece. Its territory is divided into the administrative regions of Central Greece, Attica, and part of West Greece...

because the Athenians, unable to arrive in time to defend Pagasae, had occupied Thermopylae

Thermopylae

Thermopylae is a location in Greece where a narrow coastal passage existed in antiquity. It derives its name from its hot sulphur springs. "Hot gates" is also "the place of hot springs and cavernous entrances to Hades"....

.

Hostilities with Athens did not yet take place, but Athens was threatened by the Macedonian party which Philip's gold created in Euboea

Euboea

Euboea is the second largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete. The narrow Euripus Strait separates it from Boeotia in mainland Greece. In general outline it is a long and narrow, seahorse-shaped island; it is about long, and varies in breadth from to...

. From 352 to 346 BC, Philip did not again come south. He was active in completing the subjugation of the Balkan

Balkans

The Balkans is a geopolitical and cultural region of southeastern Europe...

hill-country to the west and north, and in reducing the Greek cities of the coast as far as the Hebrus

Maritza

Maritza may refer to:*Maritza Correia , a Puerto Rican swimmer*Maritza Salas , a Puerto Rican track and field athlete*Maritza Olivares, a Mexican actress*Maritza Rodríguez, a Mexican actress...

. To the chief of these coastal cities, Olynthus

Olynthus

Olynthus was an ancient city of Chalcidice, built mostly on two flat-topped hills 30–40m in height, in a fertile plain at the head of the Gulf of Torone, near the neck of the peninsula of Pallene, about 2.5 kilometers from the sea, and about 60 stadia Olynthus was an ancient city of...

, Philip continued to profess friendship until its neighboring cities were in his hands.

Menelaus (son of Amyntas III)

For other uses, see Menelaus of MacedonMenelaus was son of Amyntas III of Macedon by his second wife Gygaea. According to Justin, he was put to death by his stepbrother Philip II in 347 BC after the capture of Olynthus. ....

, pretenders to the Macedonian throne. Olynthus had at first allied itself with Philip, but later shifted its allegiance to Athens. The latter, however, did nothing to help the city, its expeditions held back by a revolt in Euboea (probably paid by Philip's gold). The Macedonian

Ancient Macedonians

The Macedonians originated from inhabitants of the northeastern part of the Greek peninsula, in the alluvial plain around the rivers Haliacmon and lower Axios...

king finally took Olynthus in 348 BC and razed the city to the ground. The same fate was inflicted on other cities of the Chalcidian peninsula. Macedon and the regions adjoining it having now been securely consolidated, Philip celebrated his Olympic Games

Olympic Games

The Olympic Games is a major international event featuring summer and winter sports, in which thousands of athletes participate in a variety of competitions. The Olympic Games have come to be regarded as the world’s foremost sports competition where more than 200 nations participate...

at Dium

Dion, Greece

Dion or Dio is a village and a former municipality in the Pieria regional unit, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it is part of the municipality Dio-Olympos, of which it is a municipal unit. It is best known for its archaeological site and archaeological museum. Zeus was honored at...

. In 347 BC, Philip advanced to the conquest of the eastern districts about Hebrus, and compelled the submission of the Thracian

Odrysian kingdom

The Odrysian kingdom was a union of Thracian tribes that endured between the 5th and 3rd centuries BC. It consisted largely of present-day Bulgaria, spreading to parts of Northern Dobruja, parts of Northern Greece and modern-day European Turkey...

prince Cersobleptes

Cersobleptes

Cersobleptes was son of Cotys, king of Thrace, on whose death in 358 BC he inherited the kingdom in conjunction with Berisades and Amadocus II, who were probably his brothers. He was very young at the time, and the whole management of his affairs was assumed by the Euboean adventurer, Charidemus,...

. In 346 BC, he intervened effectively in the war between Thebes and the Phocians, but his wars with Athens continued intermittently. However, Athens had made overtures for peace, and when Philip again moved south, peace was sworn in Thessaly. With key Greek city-states in submission, Philip turned to Sparta

Sparta

Sparta or Lacedaemon, was a prominent city-state in ancient Greece, situated on the banks of the River Eurotas in Laconia, in south-eastern Peloponnese. It emerged as a political entity around the 10th century BC, when the invading Dorians subjugated the local, non-Dorian population. From c...

; he sent them a message, "You are advised to submit without further delay, for if I bring my army into your land, I will destroy your farms, slay your people, and raze your city." Their laconic reply: "If". Philip and Alexander would both leave them alone. Later, the Macedonian arms were carried across Epirus to the Adriatic Sea

Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan peninsula, and the system of the Apennine Mountains from that of the Dinaric Alps and adjacent ranges...

.

In 345 B.C., Philip conducted a hard-fought campaign against the Ardiaioi (Ardiaei), under their king Pluratus, during which he was seriously wounded by an Ardian soldier in the lower right leg.

In 342 BC, Philip led a great military expedition north against the Scythians, conquering the Thracian fortified settlement Eumolpia to give it his name, Philippopolis (modern Plovdiv

Plovdiv

Plovdiv is the second-largest city in Bulgaria after Sofia with a population of 338,153 inhabitants according to Census 2011. Plovdiv's history spans some 6,000 years, with traces of a Neolithic settlement dating to roughly 4000 BC; it is one of the oldest cities in Europe...

).

In 340 BC, Philip started the siege of Perinthus

Marmara Eregli

Marmara Ereğlisi is a town and district of Tekirdağ Province in the Marmara region of Turkey. The mayor is İbrahim Uyan .-Facts:Ereğli is 30 km east of the town of Tekirdağ, and 90 km west of Istanbul near a small pointed headland on the north shore of the Marmara Sea...

. Philip began another siege in 339 of the city of Byzantium

Byzantium

Byzantium was an ancient Greek city, founded by Greek colonists from Megara in 667 BC and named after their king Byzas . The name Byzantium is a Latinization of the original name Byzantion...

. After unsuccessful sieges of both cities, Philip's influence all over Greece was compromised. However, he successfully reasserted his authority in the Aegean

Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea[p] is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea located between the southern Balkan and Anatolian peninsulas, i.e., between the mainlands of Greece and Turkey. In the north, it is connected to the Marmara Sea and Black Sea by the Dardanelles and Bosporus...

by defeating an alliance of Thebans and Athenians at the Battle of Chaeronea

Battle of Chaeronea (338 BC)

The Battle of Chaeronea was fought in 338 BC, near the city of Chaeronea in Boeotia, between the forces of Philip II of Macedon and an alliance of Greek city-states...

in 338 BC, while in the same year, Philip destroyed Amfissa

Amfissa

Amfissa is a town and a former municipality in Phocis, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Delphi, of which it is the seat and a municipal unit. It is also the capital of the regional unit of Phocis...

because the residents had illegally cultivated part of the Crisaian plain which belonged to Delphi

Delphi

Delphi is both an archaeological site and a modern town in Greece on the south-western spur of Mount Parnassus in the valley of Phocis.In Greek mythology, Delphi was the site of the Delphic oracle, the most important oracle in the classical Greek world, and a major site for the worship of the god...

. Philip created and led the League of Corinth

League of Corinth

The League of Corinth, also sometimes referred to as Hellenic League was a federation of Greek states created by Philip II of Macedon during the winter of 338 BC/337 BC after the Battle of Chaeronea, to facilitate his use of military forces in his war against Persia...

in 337 BC. Members of the League agreed never to wage war against each other, unless it was to suppress revolution

Revolution

A revolution is a fundamental change in power or organizational structures that takes place in a relatively short period of time.Aristotle described two types of political revolution:...

. Philip was elected as leader (hegemon

Hegemony

Hegemony is an indirect form of imperial dominance in which the hegemon rules sub-ordinate states by the implied means of power rather than direct military force. In Ancient Greece , hegemony denoted the politico–military dominance of a city-state over other city-states...

) of the army of invasion against the Persian Empire

Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire , sometimes known as First Persian Empire and/or Persian Empire, was founded in the 6th century BCE by Cyrus the Great who overthrew the Median confederation...

. In 336 BC, when the invasion of Persia was in its very early stage, Philip was assassinated, and was succeeded on the throne of Macedon by his son Alexander III.

Assassination

Vergina

Vergina is a small town in northern Greece, located in the peripheral unit of Imathia, Central Macedonia. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Veroia, of which it is a municipal unit...

, the ancient capital of the kingdom of Macedon. The court had gathered there for the celebration of the marriage between Alexander I of Epirus

Alexander I of Epirus

Alexander I of Epirus , also known as Alexander Molossus , was a king of Epirus of the Aeacid dynasty. As the son of Neoptolemus I and brother of Olympias, he was an uncle of Alexander the Great...

and Philip's daughter, by his fourth wife Olympias

Olympias

Olympias was a Greek princess of Epirus, daughter of king Neoptolemus I of Epirus, the fourth wife of the king of Macedonia, Philip II, and mother of Alexander the Great...

, Cleopatra. While the king was entering unprotected into the town's theater (highlighting his approachability to the Greek diplomats present), he was killed by Pausanias of Orestis, one of his seven bodyguards. The assassin immediately tried to escape and reach his associates who were waiting for him with horses at the entrance of Aegae. He was pursued by three of Philip's bodyguards and died by their hands.

The reasons for Pausanias' assassination of Philip are difficult to fully expound, since there was controversy already among ancient historians. The only contemporary account in our possession is that of Aristotle

Aristotle

Aristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology...

, who states rather tersely that Philip was killed because Pausanias had been offended by the followers of Attalus

Attalus (general)

Attalus , important courtier of Macedonian king Philip II of Macedonia.In 339 BC, Attalus' niece Cleopatra Eurydice married king Philip II of Macedonia. In spring of 336 BC, Philip II appointed Attalus and Parmenion as commanders of the advance force that would invade the Persian Empire in Asia Minor...

, the king's father-in-law.

Fifty years later, the historian Cleitarchus

Cleitarchus

Cleitarchus or Clitarchus , one of the historians of Alexander the Great, son of the historian Dinon of Colophon, was possibly a native of Egypt, or at least spent a considerable time at the court of Ptolemy Lagus.Quintilian Cleitarchus or Clitarchus , one of the historians of Alexander the Great,...

expanded and embellished the story. Centuries later, this version was to be narrated by Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus was a Greek historian who flourished between 60 and 30 BC. According to Diodorus' own work, he was born at Agyrium in Sicily . With one exception, antiquity affords no further information about Diodorus' life and doings beyond what is to be found in his own work, Bibliotheca...

and all the historians who used Cleitarchus. In the sixteenth book of Diodorus' history, Pausanias had been a lover of Philip, but became jealous when Philip turned his attention to a younger man, also called Pausanias. His taunting of the new lover caused the youth to throw away his life, which turned his friend, Attalus, against Pausanias. Attalus took his revenge by inviting Pausanias to dinner, getting him drunk, then subjecting him to sexual assault.

When Pausanias complained to Philip the king felt unable to chastise Attalus, as he was about to send him to Asia with Parmenion

Parmenion

Parmenion was a Macedonian general in the service of Philip II of Macedon and Alexander the Great, murdered on a suspected false charge of treason....

, to establish a bridgehead for his planned invasion. He also married Attalus's niece, or daughter, Eurydice

Cleopatra Eurydice of Macedon

Eurydice , born Cleopatra was a mid. 4th century BCE Macedonian noblewoman, niece of Attalus, and 5th wife of Philip II of Macedon.- Biography :...

. Rather than offend Attalus, Philip attempted to mollify Pausanius by elevating him within the bodyguard. Pausanias' desire for revenge seems to have turned towards the man who had failed to avenge his damaged honour; so he planned to kill Philip, and some time after the alleged rape, while Attalus was already in Asia fighting the Persians, put his plan in action.

Other historians (e.g., Justin 9.7) suggested that Alexander and/or his mother Olympias

Olympias

Olympias was a Greek princess of Epirus, daughter of king Neoptolemus I of Epirus, the fourth wife of the king of Macedonia, Philip II, and mother of Alexander the Great...

were at least privy to the intrigue, if not themselves instigators. The latter seems to have been anything but discreet in manifesting her gratitude to Pausanias, according to Justin's report: he says that the same night of her return from exile she placed a crown on the assassin's corpse and erected a tumulus

Tumulus

A tumulus is a mound of earth and stones raised over a grave or graves. Tumuli are also known as barrows, burial mounds, Hügelgrab or kurgans, and can be found throughout much of the world. A tumulus composed largely or entirely of stones is usually referred to as a cairn...

to his memory, ordering annual sacrifices to the memory of Pausanias.

Marriages

The dates of Philip's multiple marriages and the names of some of his wives are contested. Below is the order of marriages offered by AthenaeusAthenaeus

Athenaeus , of Naucratis in Egypt, Greek rhetorician and grammarian, flourished about the end of the 2nd and beginning of the 3rd century AD...

, 13.557b–e:

- AudataAudataAudata was an Illyrian princess and later a Macedonian queen when she married Philip II of Macedon in 359 BC. She was the daughter or niece daughter of Bardyllis, the Illyrian king of the Dardanian State...

, the daughter of IllyrianIllyriansThe Illyrians were a group of tribes who inhabited part of the western Balkans in antiquity and the south-eastern coasts of the Italian peninsula...

King BardyllisBardyllisBardyllis was a king of the Dardanian Kingdom and probably its founder.Bardyllis created one of the most powerful Illyrian states, that of the Dardanians...

. Mother of CynaneCynaneCynane was half-sister to Alexander the Great, and daughter of Philip II by Audata, an Illyrian princess....

. - Phila of ElimeiaPhila of ElimeiaFor other persons named Phila, see Phila.Phila , sister of Derdas and Machatas of Elimeia, was the first or second wife of Philip II of Macedon. She appears to have remained childless.-References:*Dicaearchus ap. Aflien. xiii. p. 557, c....

, the sister of DerdasDerdasDerdas was archon of Elimiotis during the time of Philip II of Macedon. His daughter, Phila, married Philip. He had two sons, Derdas and Machatas. Machatas was father of Machatas, Harpalus and Philip, who became the satrap of India. In 380 BC, Derdas and King Amyntas of Macedon supported the...

and Machatas of ElimiotisElimiotisElimiotis or Elimeia or Elimaea was a region of Upper Macedonia that was located along the Haliacmon, north of Perrhaebia/Thessaly, west of Pieria, east of Parauaea, and south of Orestis. In earlier times, it was independent, but later was incorporated into the Argead kingdom of Macedon...

. - NicesipolisNicesipolisNicesipolis or Nicasipolis of Pherae , was a Thessalian woman, native of the city Pherae, wife or concubine of king Philip II of Macedon and mother of Thessalonica of Macedon. There is not much surviving evidence about her background and life but she is likely to have been of noble Thessalian...

of PheraePheraePherae was an ancient Greek town in southeastern Thessaly. It bordered Lake Boebeïs. In mythology, it was the home of King Admetus, whose wife, Alcestis, Heracles went into Hades to rescue. In history, it was more famous as the home of the fourth-century B.C...

, ThessalyThessalyThessaly is a traditional geographical region and an administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, Thessaly was known as Aeolia, and appears thus in Homer's Odyssey....

, mother of ThessalonicaThessalonica of MacedonThessalonike was a Macedonian princess, the daughter of king Philip II of Macedon by his Thessalian wife or concubine, Nicesipolis, from Pherae. History links her to three of the most powerful men in Macedon—daughter of King Philip II, half sister of Alexander the Great and wife of...

. - OlympiasOlympiasOlympias was a Greek princess of Epirus, daughter of king Neoptolemus I of Epirus, the fourth wife of the king of Macedonia, Philip II, and mother of Alexander the Great...

of EpirusEpirusThe name Epirus, from the Greek "Ήπειρος" meaning continent may refer to:-Geographical:* Epirus - a historical and geographical region of the southwestern Balkans, straddling modern Greece and Albania...

, mother of Alexander the Great and Cleopatra - Philinna of LarissaLarissaLarissa is the capital and biggest city of the Thessaly region of Greece and capital of the Larissa regional unit. It is a principal agricultural centre and a national transportation hub, linked by road and rail with the port of Volos, the city of Thessaloniki and Athens...

, mother of Arrhidaeus later called Philip III of MacedonPhilip III of MacedonPhilip III Arrhidaeus was the king of Macedonia from after June 11, 323 BC until his death. He was a son of King Philip II of Macedonia by Philinna of Larissa, allegedly a Thessalian dancer, and a half-brother of Alexander the Great...

. - Meda of OdessaMeda of OdessaMeda of Odessa , was a Thracian princess, daughter of the king Cothelas of Getae and wife of king Philip II of Macedon. Philip married her after Olympias. When Philip died, Meda committed suicide so that she would follow Philip to the Ades...

, daughter of the king Cothelas, of ThraceThraceThrace is a historical and geographic area in southeast Europe. As a geographical concept, Thrace designates a region bounded by the Balkan Mountains on the north, Rhodope Mountains and the Aegean Sea on the south, and by the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara on the east...

. - Cleopatra, daughter of Hippostratus and niece of general Attalus of MacedoniaAttalus (general)Attalus , important courtier of Macedonian king Philip II of Macedonia.In 339 BC, Attalus' niece Cleopatra Eurydice married king Philip II of Macedonia. In spring of 336 BC, Philip II appointed Attalus and Parmenion as commanders of the advance force that would invade the Persian Empire in Asia Minor...

. Philip renamed her Cleopatra Eurydice of MacedonCleopatra Eurydice of MacedonEurydice , born Cleopatra was a mid. 4th century BCE Macedonian noblewoman, niece of Attalus, and 5th wife of Philip II of Macedon.- Biography :...

.

Archaeological findings

Manolis Andronikos

Manolis Andronikos was a Greek archaeologist and a professor at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. He was born on October 23, 1919 at Bursa . Later, his family moved to Thessaloniki....

found, among other royal tombs, an unopened tomb at Vergina

Vergina

Vergina is a small town in northern Greece, located in the peripheral unit of Imathia, Central Macedonia. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Veroia, of which it is a municipal unit...

in the Greek prefecture of Imathia

Imathia Prefecture

Imathia is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of Central Macedonia. The capital of Imathia is the city of Veroia.-Administration:The regional unit Imathia is subdivided into 3 municipalities...

. The finds from this tomb were later included in the travelling exhibit The Search for Alexander displayed at four cities in the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

from 1980 to 1982. It is generally accepted that the site at Vergina

Vergina

Vergina is a small town in northern Greece, located in the peripheral unit of Imathia, Central Macedonia. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Veroia, of which it is a municipal unit...

was the burial site of the kings of Macedon, including Philip, but the debate about the unopened tomb is ongoing among archaeologists.

The initial suggestion that the tomb might belong to Philip II was indicated by the greaves, one of which indicated that the owner had a leg injury which distorted the natural alignment of the tibia (Philip II was recorded as having broken his tibia). What is viewed as possible proof that the tomb indeed did belong to Philip II and that the surviving bone fragments are in fact the body of Philip II comes from forensic reconstruction of the skull of Philip II by the wax casting and reconstruction of the skull which shows the damage to the right eye caused by the penetration of an object (historically recorded to be an arrow).

Eugene Borza and others have suggested that the unopened tomb actually belonged to Philip's son, Philip Arrhidaeus

Philip III of Macedon

Philip III Arrhidaeus was the king of Macedonia from after June 11, 323 BC until his death. He was a son of King Philip II of Macedonia by Philinna of Larissa, allegedly a Thessalian dancer, and a half-brother of Alexander the Great...

, and Philip was probably buried in the simpler adjacent tomb, which had been looted in antiquity. Disputations often relied on contradictions between "the body" or "skeleton" of Philip II and reliable historical accounts of his life (and injuries), as well as analyses of the paintings, pottery, and other artifacts found there.

Musgrave, et al. (2010) showed that there is no valid evidence Arrhidaeus could have been buried in the unopened tomb, hence those who made those claims, like Borza, Palagia and Bartsiokas, had actually misunderstood certain scientific facts which led them to invalid conclusions. Musgrave's study of the bones of Tomb II of Vergina found that the cranium of the male was deformed possibly by a trauma, a finding that is consistent with the history of Philip II.

According to a new study published in the April 21 edition of the journal Science, the style of the artifacts of the royal tomb date 317 B.C., a generation after Philip II's assassinations. Moreover, according to paleoanthropologist Antonis Bartsiokas of the Anaximandrian Institute of Human Evolution at the Democritus University of Thrace in Voula, Greece, and assistant professor at the Democritus who used a technique called macrophotography to study the skeleton in meticulous detail, the features identified by Musgrave, Prag, and Neave are simply normal anatomical quirks, accentuated by the effects of cremation and a poor reassembly of the remains. "The bump, for example," says Bartsiokas, "is part of the opening in the skull's frontal bone called the supraorbital notch, through which a bundle of nerves and blood vessels pass." Most people can feel this notch by pressing their fingers underneath the ridge of bone beneath the eyebrow. The bone at the site of the "injury" is simply the frontal notch and also shows no signs of healing in the bone fabric, a problem for Bartsiokas given that the wound was inflicted 18 years before Philip II's death.

Cult

The heroonHeroon

A heroon , also called heroum, was a shrine dedicated to an ancient Greek or Roman hero and used for the commemoration or cult worship of the hero. It was often erected over his supposed tomb or cenotaph....

at Vergina

Vergina

Vergina is a small town in northern Greece, located in the peripheral unit of Imathia, Central Macedonia. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Veroia, of which it is a municipal unit...

in Greek Macedonia (the ancient city of Aegae

Vergina

Vergina is a small town in northern Greece, located in the peripheral unit of Imathia, Central Macedonia. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Veroia, of which it is a municipal unit...

– Αἰγαί) is thought to have been dedicated to the worship of the family of Alexander the Great and may have housed the cult statue of Philip. It is probable that he was regarded as a hero or deified on his death. Though the Macedonians did not consider Philip a god, he did receive other forms of recognition by the Greeks, such as at Eresos

Eresos

Eresos and its twin beach village Skala Eresou are located in the southwest part of the Greek island of Lesbos. They are villages visited by considerable number of tourists...

(altar to Zeus Philippeios), Ephesos (his statue was placed in the temple of Artemis

Temple of Artemis

The Temple of Artemis , also known less precisely as the Temple of Diana, was a Greek temple dedicated to a goddess Greeks identified as Artemis and was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. It was situated at Ephesus , and was completely rebuilt three times before its eventual destruction...

), and Olympia, where the Philippeion

Philippeion

The Philippeion in the Altis of Olympia was an Ionic circular memorial of ivory and gold, which contained statues of Philip's family, Alexander the Great, Olympias, Amyntas III and Eurydice I. It was made by the Athenian sculptor Leochares in celebration of Philip's victory at the battle of Chaeronea...

was built.

Isocrates once wrote to Philip that if he defeated Persia, there was nothing left for him to do but to become a god; and Demades

Demades

-Background and early life:He was born into a poor family of ancient Paeania and was employed at one time as a common sailor, but he rose partly by his eloquence and partly by his unscrupulous character to a prominent position at Athens...

proposed that Philip be regarded as the thirteenth god; however, there is no clear evidence that Philip was raised to the divine status accorded his son Alexander.

In historical fiction

- Thomas Sundell, Bloodline of Kings: a Novel of Philip of' Macedon, a historical epic beginning with Philip's birth and ending with that of his son, Alexander. Published by Crow Woods, 2002.

External links

- A family tree focusing on his ancestors

- A family tree focusing on his descedants

- Plutarch: Life of Alexander

- Philip II of Macedonia biography by Jona Lendering on Livius: Articles in Ancient History

- Pothos.org, Death of Philip: Murder or Assassination?

- Philip II of Macedon entry in historical sourcebook by Mahlon H. Smith

- Facial reconstruction expert revealed how technique brings past to life, press release of the University of Leicester, with a portrait of Philip based on a reconstruction of his face.

- Reconstruction of the face of Philip II by Richard Neave

- Twilight of the Polis and the rise of Macedon (Philip, Demosthenes and the Fall of the Polis). Yale University courses, Lecture 24. (Introduction to Ancient Greek History)

- The Burial of the Dead (at Vergina) or The Unending Controversy on the Identity of the Occupants of Tomb II