Geostrategy

Encyclopedia

Geostrategy, a subfield of geopolitics

, is a type of foreign policy

guided principally by geographical

factors as they inform, constrain, or affect political and military planning. As with all strategies

, geostrategy is concerned with matching means to ends — in this case, a country's resources (whether they are limited or extensive) with its geopolitical objectives (which can be local, regional, or global). Strategy is as intertwined with geography as geography is with nation

hood, or as Gray

and Sloan state it, "[geography is] the mother of strategy."

Geostrategists, as distinct from geopoliticians, advocate proactive strategies, and approach geopolitics from a nationalist point-of-view. As with all political theories, geostrategies are relevant principally to the context in which they were devised: the nationality of the strategist, the strength of his or her country's resources, the scope of his or her country's goals, the political geography of the time period, and the technological factors that affect military, political, economic, and cultural engagement. Geostrategy can function normatively, advocating foreign policy based on geographic factors, analytical, describing how foreign policy is shaped by geography, or predictive, predicting a country's future foreign policy decisions on the basis of geographic factors.

Many geostrategists are also geographers, specializing in subfields of geography

, such as human geography

, political geography

, economic geography

, cultural geography

, military geography

, and strategic geography

. Geostrategy is most closely related to strategic geography.

Especially following World War II

, some scholars divide geostrategy into two schools: the uniquely German organic state theory; and, the broader Anglo-American

geostrategies.

Critics of geostrategy have asserted that it is a pseudoscientific

gloss used by dominant nations to justify imperialist

or hegemonic

aspirations, or that it has been rendered irrelevant because of technological advances, or that its essentialist

focus on geography leads geostrategists to incorrect conclusions about the conduct of foreign policy.

considerations with geopolitical factors. While geopolitics is ostensibly neutral, examining the geographic and political features of different regions, especially the impact of geography on politics, geostrategy involves comprehensive planning, assigning means for achieving national goals or securing assets of military

or political significance.

in his 1942 article "Let Us Learn Our Geopolitics." It was a translation of the German

term "Wehrgeopolitik" as used by German geostrategist Karl Haushofer

. Previous translations had been attempted, such as "defense-geopolitics." Robert Strausz-Hupé

had coined and popularized "war geopolitics" as another alternate translation.

, observers saw strategy as heavily influenced by the geographic setting of the actors. In History

, Herodotus describes a clash of civilizations between the Egyptians

, Persians

, Scythia

ns, and Greeks

—all of which he believed were heavily influenced by the physical geographic setting.

Dietrich Heinrich von Bülow proposed a geometrical science of strategy in the 1799 The Spirit of the Modern System of War. His system predicted that the larger states would swallow the smaller ones, resulting in eleven large states. Mackubin Thomas Owens notes the similarity between von Bülow's predictions and the map of Europe after the unification of Germany

and of Italy.

s, many with global reach. There were no new frontier

s for the great powers to explore

or colonize—the entire world was divided between the empires and colonial powers. From this point forward, international politics would feature the struggles of state against state.

Two strains of geopolitical thought gained prominence: an Anglo-American school, and a German school. Alfred Thayer Mahan

and Halford J. Mackinder outlined the American and British conceptions of geostrategy, respectively, in their works The Problem of Asia and "The Geographical Pivot of History

". Friedrich Ratzel

and Rudolf Kjellén

developed an organic theory of the state

which laid the foundation for Germany's unique school of geostrategy.

The most prominent German

The most prominent German

geopolitician was General Karl Haushofer

. After World War II

, during the Allied occupation of Germany

, the United States

investigated many officials and public figures to determine if they should face charges of war crimes at the Nuremberg trials

. Haushofer

, an academic primarily, was interrogated by Father Edmund A. Walsh

, a professor of geopolitics from the Georgetown

School of Foreign Service

, at the request of the U.S. authorities. Despite his involvement in crafting one of the justifications for Nazi aggression, Fr. Walsh determined that Haushofer ought not stand trial.

, the term "geopolitics" fell into disrepute, because of its association with Nazi

geopolitik

. Virtually no books published between the end of World War II and the mid-1970s used the word "geopolitics" or "geostrategy" in their

titles, and geopoliticians did not label themselves or their works as such. German theories prompted a number of critical examinations of geopolitik by American geopoliticians such as Robert Strausz-Hupé

, Derwent Whittlesey, and Andrew Gyorgy.

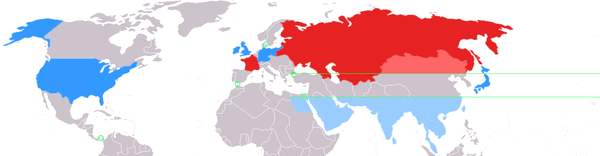

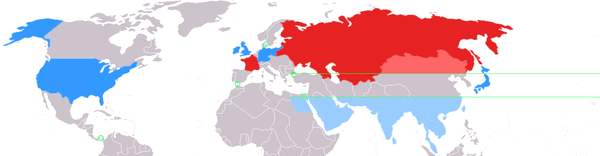

As the Cold War

began, N.J. Spykman and George F. Kennan

laid down the foundations for the U.S. policy of containment

, which would dominate Western

geostrategic thought for the next forty years.

Alexander de Seversky

would propose that airpower had fundamentally changed geostrategic considerations and thus proposed a "geopolitics of airpower." His ideas had some influence on the administration of President Dwight D. Eisenhower

, but the ideas of Spykman and Kennan would exercise greater weight. Later during the Cold War, Colin Gray

would decisively reject the idea that airpower changed geostrategic considerations, while Saul B. Cohen

examined the idea of a "shatterbelt", which would eventually inform the domino theory

.

countries, Geopolitical strategies have generally followed the course of either solidifying security obligations or accesses to global resources; however, the strategies of other countries have not been as palpable.

s in the discipline's history. While there have been many other geostrategists, these have been the most influential in shaping and developing the field as a whole.

was an American Navy

officer and president of the U.S. Naval War College. He is best known for his Influence of Sea Power upon History

series of books, which argued that naval supremacy was the deciding factor in great power

warfare. In 1900, Mahan's book The Problem of Asia was published. In this volume he laid out the first geostrategy of the modern era.

The Problem of Asia divides the continent of Asia into 3 zones:

The Debated and Debatable zone, Mahan observed, contained two peninsula

s on either end (Asia Minor

and Korea

), the Isthmus of Suez

, Palestine

, Syria

, Mesopotamia

, two countries marked by their mountain ranges (Persia and Afghanistan

), the Pamir Mountains

, the Tibet

an Himalayas

, the Yangtze Valley, and Japan

. Within this zone, Mahan asserted that there were no strong states capable of withstanding outside influence or capable even of maintaining stability within their own borders. So whereas the political situations to the north and south were relatively stable and determined, the middle remained "debatable and debated ground."

North of the 40th parallel, the vast expanse of Asia was dominated by the Russian Empire

. Russia possessed a central position on the continent, and a wedge-shaped projection into Central Asia

, bounded by the Caucasus mountains

and Caspian Sea

on one side and the mountains of Afghanistan and Western China on the other side. To prevent Russian expansionism and achievement of predominance on the Asian continent, Mahan believed pressure on Asia's flanks could be the only viable strategy pursued by sea powers.

South of the 30th parallel lay areas dominated by the sea powers—Britain

, the United States

, Germany

, and Japan

. To Mahan, the possession of India

by Britain was of key strategic importance, as India was best suited for exerting balancing pressure against Russia in Central Asia. Britain's predominance in Egypt

, China

, Australia

, and the Cape of Good Hope

was also considered important.

The strategy of sea powers, according to Mahan, ought to be to deny Russia the benefits of commerce that come from sea commerce. He noted that both the Dardanelles

and Baltic straits

could be closed by a hostile power, thereby denying Russia access to the sea. Further, this disadvantageous position would reinforce Russia's proclivity toward expansionism in order to obtain wealth or warm water ports. Natural geographic targets for Russian expansionism in search of access to the sea would therefore be the Chinese seaboard, the Persian Gulf

, and Asia Minor.

In this contest between land power and sea power, Russia would find itself allied with France

(a natural sea power, but in this case necessarily acting as a land power), arrayed against Germany, Britain, Japan, and the United States as sea powers. Further, Mahan conceived of a unified, modern state composed of Turkey

, Syria, and Mesopotamia

, possessing an efficiently organized army and navy to stand as a counterweight to Russian expansion.

Further dividing the map by geographic features, Mahan stated that the two most influential lines of division would be the Suez and Panama canal

s. As most developed nations and resources lay above the North-South division

, politics and commerce north of the two canals would be of much greater importance than those occurring south of the canals. As such, the great progress of historical development would not flow from north to south, but from east to west, in this case leading toward Asia as the locus of advance.

Halford J. Mackinder

Halford J. Mackinder

His major work, Democratic ideals and reality: a study in the politics of reconstruction, appeared in 1919.[12] It presented his theory of the Heartland and made a case for fully taking into account geopolitical factors at the Paris Peace conference and contrasted (geographical) reality with Woodrow Wilson's idealism. The book's most famous quote was: "Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland; Who rules the Heartland commands the World Island; Who rules the World Island commands the World." This message was composed to convince the world statesmen at the Paris Peace conference of the crucial importance of Eastern Europe as the strategic route to the Heartland was interpreted as requiring a strip of buffer state to separate Germany and Russia. These were created by the peace negotiators but proved to be ineffective bulwarks in 1939 (although this may be seen as a failure of other, later statesmen during the interbellum). The principal concern of his work was to warn of the possibility of another major war (a warning also given by economist John Maynard Keynes).

Mackinder was anti-Bolshevik, and as British High Commissioner in Southern Russia in late 1919 and early 1920, he stressed the need for Britain to continue her support to the White Russian forces, which he attempted to unite.[13]

[edit] Significance of Mackinder

Mackinder's work paved the way for the establishment of geography as a distinct discipline in the United Kingdom. His role in fostering the teaching of geography is probably greater than that of any other single British geographer.

Whilst Oxford did not appoint a professor of Geography until 1934, both the University of Liverpool and University of Wales, Aberystwyth established professorial chairs in Geography in 1917. Mackinder himself became a full professor in Geography in the University of London (London School of Economics) in 1923.

Mackinder is often credited with introducing two new terms into the English language : "manpower", "heartland".

[edit] Influence on Nazi strategy

The Heartland Theory was enthusiastically taken up by the German school of Geopolitik, in particular by its main proponent Karl Haushofer. Whilst Geopolitik was later embraced by the German Nazi regime in the 1930s, Mackinder was always extremely critical of the German exploitation of his ideas. The German interpretation of the Heartland Theory is referred to explicitly (without mentioning the connection to Mackinder) in The Nazis Strike, the second of Frank Capra's Why We Fight series of American World War II propaganda films.

[edit] Influence on American strategy

The Heartland theory and more generally classical geopolitics and geostrategy were extremely influential in the making of US strategic policy during the period of the Cold War.[14]

[edit] Influence on later academics

Evidence of Mackinder’s Heartland Theory can be found in the works of geopolitician Dimitri Kitsikis, particularly in his geopolitical model "Intermediate Region".

Influenced by the works of Alfred Thayer Mahan, as well as the German geographers Karl Ritter

Influenced by the works of Alfred Thayer Mahan, as well as the German geographers Karl Ritter

and Alexander von Humboldt

, Friedrich Ratzel

would lay the foundations for geopolitik

, Germany

's unique strain of geopolitics

.

Ratzel wrote on the natural division between land powers and sea powers, agreeing with Mahan that sea power was self-sustaining, as the profit from trade

would support the development of a merchant marine. However, his key contribution were the development of the concepts of raum

and the organic theory of the state

. He theorized that states were organic

and growing, and that border

s were only temporary, representing pauses in their natural movement. Raum was the land, spiritual

ly connected to a nation

(in this case, the German peoples), from which the people could draw sustenance, find adjacent inferior nations which would support them, and which would be fertilized by their kultur (culture).

Ratzel's ideas would influence the works of his student Rudolf Kjellén, as well as those of General Karl Haushofer.

was a Swedish

political scientist and student of Friedrich Ratzel. He first coined the term "geopolitics." His writings would play a decisive role in influencing General Karl Haushofer's geopolitik, and indirectly the future Nazi

foreign policy.

His writings focused on five central concepts that would underlie German geopolitik:

's geopolitik expanded upon that of Ratzel and Kjellén. While the latter two conceived of geopolitik as the state-as-an-organism-in-space put to the service of a leader, Haushofer's Munich school specifically studied geography as it related to war and designs for empire. The behavioral rules of previous geopoliticians were thus turned into dynamic normative

doctrine

s for action on lebensraum and world power.

Haushofer defined geopolitik in 1935 as "the duty to safeguard the right to the soil, to the land in the widest sense, not only the land within the frontiers of the Reich, but the right to the more extensive Volk

and cultural lands." Culture itself was seen as the most conducive element to dynamic expansion. Culture provided a guide as to the best areas for expansion, and could make expansion safe, whereas solely military or commercial power could not.

To Haushofer, the existence of a state depended on living space, the pursuit of which must serve as the basis for all policies. Germany had a high population density

, whereas the old colonial powers had a much lower density: a virtual mandate for German expansion into resource-rich areas. A buffer zone of territories or insignificant states on one's borders would serve to protect Germany. Closely linked to this need was Haushofer's assertion that the existence of small states was evidence of political regression and disorder in the international system. The small states surrounding Germany ought to be brought into the vital German order. These states were seen as being too small to maintain practical autonomy (even if they maintained large colonial possessions) and would be better served by protection and organization within Germany. In Europe, he saw Belgium

, the Netherlands

, Portugal

, Denmark

, Switzerland

, Greece

and the "mutilated alliance" of Austro-Hungary as supporting his assertion.

Haushofer and the Munich school of geopolitik would eventually expand their conception of lebensraum and autarky well past a restoration of the German borders of 1914

and "a place in the sun." They set as goals a New European Order, then a New Afro-European Order, and eventually to a Eurasian Order. This concept became known as a pan-region

, taken from the American Monroe Doctrine

, and the idea of national and continental self-sufficiency. This was a forward-looking refashioning of the drive for colonies

, something that geopoliticians did not see as an economic necessity, but more as a matter of prestige, and of putting pressure on older colonial powers. The fundamental motivating force was not be economic, but cultural and spiritual.

Beyond being an economic concept, pan-regions were a strategic concept as well. Haushofer acknowledged the strategic concept of the Heartland

put forward by the Halford Mackinder. If Germany could control Eastern Europe

and subsequently Russian territory

, it could control a strategic area to which hostile sea power could be denied. Allying with Italy

and Japan

would further augment German strategic control of Eurasia, with those states becoming the naval arms protecting Germany's insular position.

was an Dutch

-American geostrategist, known as the "godfather of containment

." His geostrategic work, The Geography of the Peace (1944), argued that the balance of power in Eurasia

directly affected United States security.

N.J. Spykman based his geostrategic ideas on those of Sir Halford Mackinder's Heartland theory. Spykman's key contribution was to alter the strategic valuation of the Heartland vs. the "Rimland" (a geographic area analogous to Mackinder's "Inner or Marginal Crescent"). Spykman does not see the heartland as a region which will be unified by powerful transport

or communication

infrastructure in the near future. As such, it won't be in a position to compete with the United States' sea power, despite its uniquely defensive position. The rimland possessed all of the key resources and populations—its domination was key to the control of Eurasia. His strategy was for Offshore powers, and perhaps Russia as well, to resist the consolidation of control over the rimland by any one power. Balanced power would lead to peace.

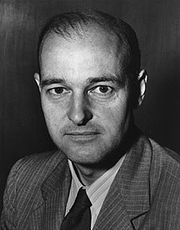

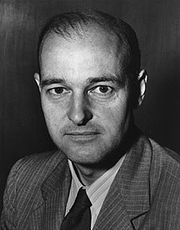

George F. Kennan

George F. Kennan

, U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union, laid out the seminal Cold War geostrategy in his Long Telegram and The Sources of Soviet Conduct. He coined the term "containment

", which would become the guiding idea for U.S. grand strategy

over the next forty years, although the term would come to mean something significantly different from Kennan's original formulation.

Kennan advocated what was called "strongpoint containment." In his view, the United States and its allies needed to protect the productive industrial areas of the world from Soviet domination. He noted that of the five centers of industrial strength in the world—the United States, Britain, Japan, Germany, and Russia—the only contested area was that of Germany. Kennan was concerned about maintaining the balance of power

between the U.S. and the USSR, and in his view, only these few industrialized areas mattered.

Here Kennan differed from Paul Nitze

, whose seminal Cold War document, NSC-68

, called for "undifferentiated or global containment," along with a massive military buildup. Kennan saw the Soviet Union as an ideological

and political challenger rather than a true military threat. There was no reason to fight the Soviets throughout Eurasia

, because those regions were not productive, and the Soviet Union was already exhausted from World War II

, limiting its ability to project power abroad. Therefore, Kennan disapproved of U.S. involvement in Vietnam

, and later spoke out critically against Reagan

's military buildup.

Henry Kissinger

Henry Kissinger

implemented two geostrategic objectives when in office: the deliberate move to shift the polarity

of the international system from bipolar to tripolar; and, the designation of regional stabilizing states in connection with the Nixon Doctrine

. In Chapter 28 of his long work, Diplomacy

, Kissinger discusses the "opening of China" as a deliberate strategy to change the balance of power

in the international system, taking advantage of the split within the Sino-Soviet bloc

. The regional stabilizers were pro-American states which would receive significant U.S. aid in exchange for assuming responsibility for regional stability. Among the regional stabilizers designated by Kissinger were Zaire

, Iran

, and Indonesia

.

laid out his most significant contribution to post-Cold War

geostrategy in his 1997 book The Grand Chessboard. He defined four regions of Eurasia

, and in which ways the United States ought to design its policy toward each region in order to maintain its global primacy. The four regions (echoing Mackinder and Spykman) are:

In his subsequent book, The Choice, Brzezinski updates his geostrategy in light of globalization

, 9/11

and the intervening six years between the two books.

Geostrategy encounters a wide variety of criticisms. It has been called a crude form of geographic determinism

. It is seen as a gloss used to justify international aggression and expansionism

—it is linked to Nazi war plans, and to a perceived U.S. creation of Cold War divisions through its containment strategy. Marxists

and critical theorists

believe geostrategy is simply a justification for American imperialism.

Some political scientists argue that as the importance of non-state actor

s rises, the importance of geopolitics concomitantly falls. Similarly, those who see the rise of economic issues in priority over security issues argue that geoeconomics

is more relevant to the modern era than geostrategy.

Most international relations theory

that is critical of realism in international relations is likewise critical of geostrategy because of the assumptions it makes about the hierarchy of the international system based on power

.

Further, the relevance of geography to international politics is questioned because advances in technology alter the importance of geographical features, and in some cases make those features irrelevant. Thus some geographic factors do not have the permanent importance that some geostrategists ascribe to them.

Geostrategy by country:

Geostrategy by region:

Geostrategy by topic:

Related fields:

Geopolitics

Geopolitics, from Greek Γη and Πολιτική in broad terms, is a theory that describes the relation between politics and territory whether on local or international scale....

, is a type of foreign policy

Foreign policy

A country's foreign policy, also called the foreign relations policy, consists of self-interest strategies chosen by the state to safeguard its national interests and to achieve its goals within international relations milieu. The approaches are strategically employed to interact with other countries...

guided principally by geographical

Geography

Geography is the science that studies the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. A literal translation would be "to describe or write about the Earth". The first person to use the word "geography" was Eratosthenes...

factors as they inform, constrain, or affect political and military planning. As with all strategies

Strategy

Strategy, a word of military origin, refers to a plan of action designed to achieve a particular goal. In military usage strategy is distinct from tactics, which are concerned with the conduct of an engagement, while strategy is concerned with how different engagements are linked...

, geostrategy is concerned with matching means to ends — in this case, a country's resources (whether they are limited or extensive) with its geopolitical objectives (which can be local, regional, or global). Strategy is as intertwined with geography as geography is with nation

Nation

A nation may refer to a community of people who share a common language, culture, ethnicity, descent, and/or history. In this definition, a nation has no physical borders. However, it can also refer to people who share a common territory and government irrespective of their ethnic make-up...

hood, or as Gray

Colin S. Gray

Colin S. Gray is a British-American strategic thinker and professor of International Relations and Strategic Studies at the University of Reading, where he is the director of the Centre for Strategic Studies. In addition, he is a Senior Associate to the National Institute for Public Policy.Gray...

and Sloan state it, "[geography is] the mother of strategy."

Geostrategists, as distinct from geopoliticians, advocate proactive strategies, and approach geopolitics from a nationalist point-of-view. As with all political theories, geostrategies are relevant principally to the context in which they were devised: the nationality of the strategist, the strength of his or her country's resources, the scope of his or her country's goals, the political geography of the time period, and the technological factors that affect military, political, economic, and cultural engagement. Geostrategy can function normatively, advocating foreign policy based on geographic factors, analytical, describing how foreign policy is shaped by geography, or predictive, predicting a country's future foreign policy decisions on the basis of geographic factors.

Many geostrategists are also geographers, specializing in subfields of geography

Geography

Geography is the science that studies the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. A literal translation would be "to describe or write about the Earth". The first person to use the word "geography" was Eratosthenes...

, such as human geography

Human geography

Human geography is one of the two major sub-fields of the discipline of geography. Human geography is the study of the world, its people, communities, and cultures. Human geography differs from physical geography mainly in that it has a greater focus on studying human activities and is more...

, political geography

Political geography

Political geography is the field of human geography that is concerned with the study of both the spatially uneven outcomes of political processes and the ways in which political processes are themselves affected by spatial structures...

, economic geography

Economic geography

Economic geography is the study of the location, distribution and spatial organization of economic activities across the world. The subject matter investigated is strongly influenced by the researcher's methodological approach. Neoclassical location theorists, following in the tradition of Alfred...

, cultural geography

Cultural geography

Cultural geography is a sub-field within human geography. Cultural geography is the study of cultural products and norms and their variations across and relations to spaces and places...

, military geography

Military geography

Military geography is a sub-field of geography that is used by, not only the military, but also academics and politicians to understand the geopolitical sphere through the militaristic lens...

, and strategic geography

Strategic geography

Strategic geography is concerned with the control of, or access to, spatial areas that have an impact on the security and prosperity of nations. Spatial areas that concern strategic geography change with human needs and development. This field is a subset of human geography, itself a subset of the...

. Geostrategy is most closely related to strategic geography.

Especially following World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, some scholars divide geostrategy into two schools: the uniquely German organic state theory; and, the broader Anglo-American

Anglo-American relations

British–American relations encompass many complex relations over the span of four centuries, beginning in 1607 with England's first permanent colony in North America called Jamestown, to the present day, between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the United States of...

geostrategies.

Critics of geostrategy have asserted that it is a pseudoscientific

Pseudoscience

Pseudoscience is a claim, belief, or practice which is presented as scientific, but which does not adhere to a valid scientific method, lacks supporting evidence or plausibility, cannot be reliably tested, or otherwise lacks scientific status...

gloss used by dominant nations to justify imperialist

Imperialism

Imperialism, as defined by Dictionary of Human Geography, is "the creation and/or maintenance of an unequal economic, cultural, and territorial relationships, usually between states and often in the form of an empire, based on domination and subordination." The imperialism of the last 500 years,...

or hegemonic

Hegemony

Hegemony is an indirect form of imperial dominance in which the hegemon rules sub-ordinate states by the implied means of power rather than direct military force. In Ancient Greece , hegemony denoted the politico–military dominance of a city-state over other city-states...

aspirations, or that it has been rendered irrelevant because of technological advances, or that its essentialist

Essentialism

In philosophy, essentialism is the view that, for any specific kind of entity, there is a set of characteristics or properties all of which any entity of that kind must possess. Therefore all things can be precisely defined or described...

focus on geography leads geostrategists to incorrect conclusions about the conduct of foreign policy.

Defining geostrategy

Academics, theorists, and practitioners of geopolitics have agreed upon no standard definition for "geostrategy." Most all definitions, however, emphasize the merger of strategicStrategy

Strategy, a word of military origin, refers to a plan of action designed to achieve a particular goal. In military usage strategy is distinct from tactics, which are concerned with the conduct of an engagement, while strategy is concerned with how different engagements are linked...

considerations with geopolitical factors. While geopolitics is ostensibly neutral, examining the geographic and political features of different regions, especially the impact of geography on politics, geostrategy involves comprehensive planning, assigning means for achieving national goals or securing assets of military

Military

A military is an organization authorized by its greater society to use lethal force, usually including use of weapons, in defending its country by combating actual or perceived threats. The military may have additional functions of use to its greater society, such as advancing a political agenda e.g...

or political significance.

Coining the term

The term "geo-strategy" was first used by Frederick L. SchumanFrederick L. Schuman

Frederick Lewis Schuman , was a historian, an American political scientist and international relations scholar. He was a professor of history at Williams College, an analyst of international relations, and social scientist, focusing on the period between World War I and World War II.-Publications: ...

in his 1942 article "Let Us Learn Our Geopolitics." It was a translation of the German

German language

German is a West Germanic language, related to and classified alongside English and Dutch. With an estimated 90 – 98 million native speakers, German is one of the world's major languages and is the most widely-spoken first language in the European Union....

term "Wehrgeopolitik" as used by German geostrategist Karl Haushofer

Karl Haushofer

Karl Ernst Haushofer was a German general, geographer and geopolitician. Through his student Rudolf Hess, Haushofer's ideas may have influenced the development of Adolf Hitler's expansionist strategies, although Haushofer denied direct influence on the Nazi regime.-Biography:Haushofer belonged to...

. Previous translations had been attempted, such as "defense-geopolitics." Robert Strausz-Hupé

Robert Strausz-Hupé

Robert Strausz-Hupé was a U.S. diplomat and geopolitician.In 1923 he immigrated to the United States. Serving as an advisor on foreign investment to American financial institutions, he watched the Depression spread political misery across America and Europe...

had coined and popularized "war geopolitics" as another alternate translation.

Modern definitions

- "[G]eostrategy is about the exercise of power over particularly critical spaces on the Earth’s surface; about crafting a political presence over the international system. It is aimed at enhancing one’s security and prosperity; about making the international system more prosperous; about shaping rather than being shaped. A geostrategy is about securing access to certain trade routes, strategic bottlenecks, rivers, islands and seas. It requires an extensive military presence, normally coterminous with the opening of overseas military stations and the building of warships capable of deep oceanic power projection. It also requires a network of alliances with other great powers who share one’s aims or with smaller ‘lynchpin states’ that are located in the regions one deems important."

- —James Rogers and Luis Simón, "Think Again: European Geostrategy"

- "[T]he words geopolitical, strategic, and geostrategic are used to convey the following meanings: geopolitical reflects the combination of geographic and political factors determining the condition of a state or region, and emphasizing the impact of geography on politics; strategic refers to the comprehensive and planned application of measures to achieve a central goal or to vital assets of military significance; and geostrategic merges strategic consideration with geopolitical ones."

- —Zbigniew BrzezinskiZbigniew BrzezinskiZbigniew Kazimierz Brzezinski is a Polish American political scientist, geostrategist, and statesman who served as United States National Security Advisor to President Jimmy Carter from 1977 to 1981....

, Game Plan (emphasis in original)

- "For the United StatesUnited StatesThe United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, EurasiaEurasiaEurasia is a continent or supercontinent comprising the traditional continents of Europe and Asia ; covering about 52,990,000 km2 or about 10.6% of the Earth's surface located primarily in the eastern and northern hemispheres...

n geostrategy involves the purposeful management of geostrategically dynamic states and the careful handling of geopolitically catalytic states, in keeping with the twin interests of America in the short-term preservation of its unique global power and in the long-run transformation of it into increasingly institutionalizedInstitutionalism in international relationsInstitutionalism in international relations comprises a group of differing theories on international relations . Functionalist and neofunctionalist approaches, regime theory, and state cartel theory have in common their focus on the structures of the international system, but they substantially...

global cooperation. To put it in a terminology that hearkens back to the more brutal age of ancient empires, the three grand imperatives of imperialImperialismImperialism, as defined by Dictionary of Human Geography, is "the creation and/or maintenance of an unequal economic, cultural, and territorial relationships, usually between states and often in the form of an empire, based on domination and subordination." The imperialism of the last 500 years,...

geostrategy are to prevent collusionCollusionCollusion is an agreement between two or more persons, sometimes illegal and therefore secretive, to limit open competition by deceiving, misleading, or defrauding others of their legal rights, or to obtain an objective forbidden by law typically by defrauding or gaining an unfair advantage...

and maintain security dependence among the vassalVassalA vassal or feudatory is a person who has entered into a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. The obligations often included military support and mutual protection, in exchange for certain privileges, usually including the grant of land held...

s, to keep tributariesTributaryA tributary or affluent is a stream or river that flows into a main stem river or a lake. A tributary does not flow directly into a sea or ocean...

pliantComplianceCompliance can mean:*In mechanical science, the inverse of stiffness*Compliance , a patient's adherence to a recommended course of treatment...

and protected, and to keep the barbarianBarbarianBarbarian and savage are terms used to refer to a person who is perceived to be uncivilized. The word is often used either in a general reference to a member of a nation or ethnos, typically a tribal society as seen by an urban civilization either viewed as inferior, or admired as a noble savage...

s from coming together."

- —Zbigniew Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard

- Geostrategy is the geographic direction of a state's foreign policy. More precisely, geostrategy describes where a state concentrates its efforts by projecting military power and directing diplomatic activity. The underlying assumption is that states have limited resources and are unable, even if they are willing, to conduct a tous asimuths foreign policy. Instead they must focus politically and militarily on specific areas of the world. Geostrategy describes this foreign-policy thrust of a state and does not deal with motivation or decision-making processes. The geostrategy of a state, therefore, is not necessarily motivated by geographic or geopolitical factors. A state may project power to a location because of ideological reasons, interest groups, or simply the whim of its leader.

- —Jakub J. GrygielJakub J. GrygielJakub J. Grygiel is the George H. W. Bush Associate Professor at The Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies . He was awarded the 2005 Rear Admiral Ernest M...

, Great Powers and Geopolitical Change (emphasis in original)

- "It is recognized that the term 'geo-strategy' is more often used, in current writing, in a global context, denoting the consideration of global land-sea distribution, distances, and accessibility among other geographical factors in strategic planning and action... Here the definition of geo-strategy is used in a more limited regional frame wherein the sum of geographic factors interact to influence or to give advantage to one adversary, or intervene to modify strategic planning as well as political and military venture."

- —Lim Joo-Jock, Geo-Strategy and the South China Sea Basin. (emphasis in original)

- "A science named "geo-strategy" would be unimaginable in any other period of history but ours. It is the characteristic product of turbulent twentieth-century world politics."

- -Andrew Gyorgi, The Geopolitics of War: Total War and Geostrategy (1943).

- "'Geostrategy,'—a word of uncertain meaning—has... been avoided."

- —Stephen B. Jones, "The Power Inventory and National Strategy"

Precursors

As early as HerodotusHerodotus

Herodotus was an ancient Greek historian who was born in Halicarnassus, Caria and lived in the 5th century BC . He has been called the "Father of History", and was the first historian known to collect his materials systematically, test their accuracy to a certain extent and arrange them in a...

, observers saw strategy as heavily influenced by the geographic setting of the actors. In History

Histories (Herodotus)

The Histories of Herodotus is considered one of the seminal works of history in Western literature. Written from the 450s to the 420s BC in the Ionic dialect of classical Greek, The Histories serves as a record of the ancient traditions, politics, geography, and clashes of various cultures that...

, Herodotus describes a clash of civilizations between the Egyptians

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt was an ancient civilization of Northeastern Africa, concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in what is now the modern country of Egypt. Egyptian civilization coalesced around 3150 BC with the political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaoh...

, Persians

Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire , sometimes known as First Persian Empire and/or Persian Empire, was founded in the 6th century BCE by Cyrus the Great who overthrew the Median confederation...

, Scythia

Scythia

In antiquity, Scythian or Scyths were terms used by the Greeks to refer to certain Iranian groups of horse-riding nomadic pastoralists who dwelt on the Pontic-Caspian steppe...

ns, and Greeks

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

—all of which he believed were heavily influenced by the physical geographic setting.

Dietrich Heinrich von Bülow proposed a geometrical science of strategy in the 1799 The Spirit of the Modern System of War. His system predicted that the larger states would swallow the smaller ones, resulting in eleven large states. Mackubin Thomas Owens notes the similarity between von Bülow's predictions and the map of Europe after the unification of Germany

Unification of Germany

The formal unification of Germany into a politically and administratively integrated nation state officially occurred on 18 January 1871 at the Versailles Palace's Hall of Mirrors in France. Princes of the German states gathered there to proclaim Wilhelm of Prussia as Emperor Wilhelm of the German...

and of Italy.

Golden age

Between 1890 and 1919 the world became a geostrategist's paradise, leading to the formulation of the classical geopolitical theories. The international system featured rising and falling great powerGreat power

A great power is a nation or state that has the ability to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength and diplomatic and cultural influence which may cause small powers to consider the opinions of great powers before taking actions...

s, many with global reach. There were no new frontier

Frontier

A frontier is a political and geographical term referring to areas near or beyond a boundary. 'Frontier' was absorbed into English from French in the 15th century, with the meaning "borderland"--the region of a country that fronts on another country .The use of "frontier" to mean "a region at the...

s for the great powers to explore

Exploration

Exploration is the act of searching or traveling around a terrain for the purpose of discovery of resources or information. Exploration occurs in all non-sessile animal species, including humans...

or colonize—the entire world was divided between the empires and colonial powers. From this point forward, international politics would feature the struggles of state against state.

Two strains of geopolitical thought gained prominence: an Anglo-American school, and a German school. Alfred Thayer Mahan

Alfred Thayer Mahan

Alfred Thayer Mahan was a United States Navy flag officer, geostrategist, and historian, who has been called "the most important American strategist of the nineteenth century." His concept of "sea power" was based on the idea that countries with greater naval power will have greater worldwide...

and Halford J. Mackinder outlined the American and British conceptions of geostrategy, respectively, in their works The Problem of Asia and "The Geographical Pivot of History

The Geographical Pivot of History

"The Geographical Pivot of History" was an article submitted by Halford John Mackinder in 1904 to the Royal Geographical Society that advanced his Heartland Theory...

". Friedrich Ratzel

Friedrich Ratzel

Friedrich Ratzel was a German geographer and ethnographer, notable for first using the term Lebensraum in the sense that the National Socialists later would.-Life:...

and Rudolf Kjellén

Rudolf Kjellén

Johan Rudolf Kjellén was a Swedish political scientist and politician who first coined the term "geopolitics". His work was influenced by Friedrich Ratzel...

developed an organic theory of the state

Organic theory of the state

The Organic Theory of the State is a species of political collectivism which maintains that the state transcends individuals within the State in power, right, or priority...

which laid the foundation for Germany's unique school of geostrategy.

World War II

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

geopolitician was General Karl Haushofer

Karl Haushofer

Karl Ernst Haushofer was a German general, geographer and geopolitician. Through his student Rudolf Hess, Haushofer's ideas may have influenced the development of Adolf Hitler's expansionist strategies, although Haushofer denied direct influence on the Nazi regime.-Biography:Haushofer belonged to...

. After World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, during the Allied occupation of Germany

Allied Control Council

The Allied Control Council or Allied Control Authority, known in the German language as the Alliierter Kontrollrat and also referred to as the Four Powers , was a military occupation governing body of the Allied Occupation Zones in Germany after the end of World War II in Europe...

, the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

investigated many officials and public figures to determine if they should face charges of war crimes at the Nuremberg trials

Nuremberg Trials

The Nuremberg Trials were a series of military tribunals, held by the victorious Allied forces of World War II, most notable for the prosecution of prominent members of the political, military, and economic leadership of the defeated Nazi Germany....

. Haushofer

Haushofer

Haushofer may refer to* Karl Haushofer, German politician and soldier, famous geographer* Albrecht Haushofer, German geographer, son of previous* Marlen Haushofer, Austrian author...

, an academic primarily, was interrogated by Father Edmund A. Walsh

Edmund A. Walsh

Fr. Edmund Aloysius Walsh, S.J. was an American Jesuit Catholic priest, professor of geopolitics and founder of the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service, which he founded in 1919–six years before the U.S...

, a professor of geopolitics from the Georgetown

Georgetown University

Georgetown University is a private, Jesuit, research university whose main campus is in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C. Founded in 1789, it is the oldest Catholic university in the United States...

School of Foreign Service

Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service

The Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service is a school within Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., United States. Jesuit priest Edmund A...

, at the request of the U.S. authorities. Despite his involvement in crafting one of the justifications for Nazi aggression, Fr. Walsh determined that Haushofer ought not stand trial.

Cold War

After the Second World WarWorld War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, the term "geopolitics" fell into disrepute, because of its association with Nazi

Nazism

Nazism, the common short form name of National Socialism was the ideology and practice of the Nazi Party and of Nazi Germany...

geopolitik

Geopolitik

Geopolitik is the branch of uniquely German geostrategy. It developed as a distinct strain of thought after Otto von Bismarck's unification of the German states but began its development in earnest only under Emperor Wilhelm II...

. Virtually no books published between the end of World War II and the mid-1970s used the word "geopolitics" or "geostrategy" in their

titles, and geopoliticians did not label themselves or their works as such. German theories prompted a number of critical examinations of geopolitik by American geopoliticians such as Robert Strausz-Hupé

Robert Strausz-Hupé

Robert Strausz-Hupé was a U.S. diplomat and geopolitician.In 1923 he immigrated to the United States. Serving as an advisor on foreign investment to American financial institutions, he watched the Depression spread political misery across America and Europe...

, Derwent Whittlesey, and Andrew Gyorgy.

As the Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

began, N.J. Spykman and George F. Kennan

George F. Kennan

George Frost Kennan was an American adviser, diplomat, political scientist and historian, best known as "the father of containment" and as a key figure in the emergence of the Cold War...

laid down the foundations for the U.S. policy of containment

Containment

Containment was a United States policy using military, economic, and diplomatic strategies to stall the spread of communism, enhance America’s security and influence abroad, and prevent a "domino effect". A component of the Cold War, this policy was a response to a series of moves by the Soviet...

, which would dominate Western

Western world

The Western world, also known as the West and the Occident , is a term referring to the countries of Western Europe , the countries of the Americas, as well all countries of Northern and Central Europe, Australia and New Zealand...

geostrategic thought for the next forty years.

Alexander de Seversky

Alexander Procofieff de Seversky

Alexander Nikolaievich Prokofiev de Seversky was a Russian-American aviation pioneer, inventor, and influential advocate of strategic air power.-Early life:...

would propose that airpower had fundamentally changed geostrategic considerations and thus proposed a "geopolitics of airpower." His ideas had some influence on the administration of President Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower was the 34th President of the United States, from 1953 until 1961. He was a five-star general in the United States Army...

, but the ideas of Spykman and Kennan would exercise greater weight. Later during the Cold War, Colin Gray

Colin Gray

Colin Gray may refer to:* Colin Falkland Gray, World War II New Zealand fighter ace* Colin S. Gray, contemporary British-American scholar of international relations...

would decisively reject the idea that airpower changed geostrategic considerations, while Saul B. Cohen

Saul B. Cohen

Saul B. Cohen is an American human geographer.Cohen graduated at Harvard University just before the faculty closed its Department of Geography . He is President emeritus of the Queens College and was Professor of Geography at the Hunter College in New York.- Publications :*Israel's Fishing...

examined the idea of a "shatterbelt", which would eventually inform the domino theory

Domino theory

The domino theory was a reason for war during the 1950s to 1980s, promoted at times by the government of the United States, that speculated that if one state in a region came under the influence of communism, then the surrounding countries would follow in a domino effect...

.

Post-Cold War

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, for most NATO or former Warsaw PactWarsaw Pact

The Warsaw Treaty Organization of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance , or more commonly referred to as the Warsaw Pact, was a mutual defense treaty subscribed to by eight communist states in Eastern Europe...

countries, Geopolitical strategies have generally followed the course of either solidifying security obligations or accesses to global resources; however, the strategies of other countries have not been as palpable.

Notable geostrategists

The below geostrategists were instrumental in founding and developing the major geostrategic doctrineDoctrine

Doctrine is a codification of beliefs or a body of teachings or instructions, taught principles or positions, as the body of teachings in a branch of knowledge or belief system...

s in the discipline's history. While there have been many other geostrategists, these have been the most influential in shaping and developing the field as a whole.

Alfred Thayer Mahan

Alfred Thayer MahanAlfred Thayer Mahan

Alfred Thayer Mahan was a United States Navy flag officer, geostrategist, and historian, who has been called "the most important American strategist of the nineteenth century." His concept of "sea power" was based on the idea that countries with greater naval power will have greater worldwide...

was an American Navy

United States Navy

The United States Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the seven uniformed services of the United States. The U.S. Navy is the largest in the world; its battle fleet tonnage is greater than that of the next 13 largest navies combined. The U.S...

officer and president of the U.S. Naval War College. He is best known for his Influence of Sea Power upon History

The Influence of Sea Power upon History

The Influence of Sea Power Upon History: 1660-1783 is a history of naval warfare written in 1890 by Alfred Thayer Mahan. It details the role of sea power throughout history and discusses the various factors needed to support and achieve sea power, with emphasis on having the largest and most...

series of books, which argued that naval supremacy was the deciding factor in great power

Great power

A great power is a nation or state that has the ability to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength and diplomatic and cultural influence which may cause small powers to consider the opinions of great powers before taking actions...

warfare. In 1900, Mahan's book The Problem of Asia was published. In this volume he laid out the first geostrategy of the modern era.

The Problem of Asia divides the continent of Asia into 3 zones:

- A northern zone, located above the 40th parallel north40th parallel northThe 40th parallel north is a circle of latitude that is 40 degrees north of the Earth's equatorial plane. It crosses Europe, the Mediterranean Sea, Asia, the Pacific Ocean, North America, and the Atlantic Ocean....

, characterized by its cold climate, and dominated by land power; - The "Debatable and Debated" zone, located between the 40th and 30th parallels30th parallel northThe 30th parallel north is a circle of latitude that is 30 degrees north of the Earth's equatorial plane. It stands one-third of the way between the equator and the North Pole and crosses Africa, Asia, the Pacific Ocean, North America and the Atlantic Ocean....

, characterized by a temperate climate; and, - A southern zone, located below the 30th parallel north, characterized by its hot climate, and dominated by sea power.

The Debated and Debatable zone, Mahan observed, contained two peninsula

Peninsula

A peninsula is a piece of land that is bordered by water on three sides but connected to mainland. In many Germanic and Celtic languages and also in Baltic, Slavic and Hungarian, peninsulas are called "half-islands"....

s on either end (Asia Minor

Asia Minor

Asia Minor is a geographical location at the westernmost protrusion of Asia, also called Anatolia, and corresponds to the western two thirds of the Asian part of Turkey...

and Korea

Korean Peninsula

The Korean Peninsula is a peninsula in East Asia. It extends southwards for about 684 miles from continental Asia into the Pacific Ocean and is surrounded by the Sea of Japan to the south, and the Yellow Sea to the west, the Korea Strait connecting the first two bodies of water.Until the end of...

), the Isthmus of Suez

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal , also known by the nickname "The Highway to India", is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea. Opened in November 1869 after 10 years of construction work, it allows water transportation between Europe and Asia without navigation...

, Palestine

Palestine

Palestine is a conventional name, among others, used to describe the geographic region between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River, and various adjoining lands....

, Syria

Syria

Syria , officially the Syrian Arab Republic , is a country in Western Asia, bordering Lebanon and the Mediterranean Sea to the West, Turkey to the north, Iraq to the east, Jordan to the south, and Israel to the southwest....

, Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a toponym for the area of the Tigris–Euphrates river system, largely corresponding to modern-day Iraq, northeastern Syria, southeastern Turkey and southwestern Iran.Widely considered to be the cradle of civilization, Bronze Age Mesopotamia included Sumer and the...

, two countries marked by their mountain ranges (Persia and Afghanistan

Afghanistan

Afghanistan , officially the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located in the centre of Asia, forming South Asia, Central Asia and the Middle East. With a population of about 29 million, it has an area of , making it the 42nd most populous and 41st largest nation in the world...

), the Pamir Mountains

Pamir Mountains

The Pamir Mountains are a mountain range in Central Asia formed by the junction or knot of the Himalayas, Tian Shan, Karakoram, Kunlun, and Hindu Kush ranges. They are among the world’s highest mountains and since Victorian times they have been known as the "Roof of the World" a probable...

, the Tibet

Tibet

Tibet is a plateau region in Asia, north-east of the Himalayas. It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people as well as some other ethnic groups such as Monpas, Qiang, and Lhobas, and is now also inhabited by considerable numbers of Han and Hui people...

an Himalayas

Himalayas

The Himalaya Range or Himalaya Mountains Sanskrit: Devanagari: हिमालय, literally "abode of snow"), usually called the Himalayas or Himalaya for short, is a mountain range in Asia, separating the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau...

, the Yangtze Valley, and Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

. Within this zone, Mahan asserted that there were no strong states capable of withstanding outside influence or capable even of maintaining stability within their own borders. So whereas the political situations to the north and south were relatively stable and determined, the middle remained "debatable and debated ground."

North of the 40th parallel, the vast expanse of Asia was dominated by the Russian Empire

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

. Russia possessed a central position on the continent, and a wedge-shaped projection into Central Asia

Central Asia

Central Asia is a core region of the Asian continent from the Caspian Sea in the west, China in the east, Afghanistan in the south, and Russia in the north...

, bounded by the Caucasus mountains

Caucasus Mountains

The Caucasus Mountains is a mountain system in Eurasia between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea in the Caucasus region .The Caucasus Mountains includes:* the Greater Caucasus Mountain Range and* the Lesser Caucasus Mountains....

and Caspian Sea

Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the largest enclosed body of water on Earth by area, variously classed as the world's largest lake or a full-fledged sea. The sea has a surface area of and a volume of...

on one side and the mountains of Afghanistan and Western China on the other side. To prevent Russian expansionism and achievement of predominance on the Asian continent, Mahan believed pressure on Asia's flanks could be the only viable strategy pursued by sea powers.

South of the 30th parallel lay areas dominated by the sea powers—Britain

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

, the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

, and Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

. To Mahan, the possession of India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

by Britain was of key strategic importance, as India was best suited for exerting balancing pressure against Russia in Central Asia. Britain's predominance in Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

, China

China

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

, Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

, and the Cape of Good Hope

Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula, South Africa.There is a misconception that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Africa, because it was once believed to be the dividing point between the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. In fact, the...

was also considered important.

The strategy of sea powers, according to Mahan, ought to be to deny Russia the benefits of commerce that come from sea commerce. He noted that both the Dardanelles

Dardanelles

The Dardanelles , formerly known as the Hellespont, is a narrow strait in northwestern Turkey connecting the Aegean Sea to the Sea of Marmara. It is one of the Turkish Straits, along with its counterpart the Bosphorus. It is located at approximately...

and Baltic straits

Danish straits

The Danish straits are the three channels connecting the Baltic Sea to the North Sea through the Kattegat and Skagerrak. They transect Denmark, and are not to be confused with the Denmark Strait between Greenland and Iceland...

could be closed by a hostile power, thereby denying Russia access to the sea. Further, this disadvantageous position would reinforce Russia's proclivity toward expansionism in order to obtain wealth or warm water ports. Natural geographic targets for Russian expansionism in search of access to the sea would therefore be the Chinese seaboard, the Persian Gulf

Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, in Southwest Asia, is an extension of the Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.The Persian Gulf was the focus of the 1980–1988 Iran-Iraq War, in which each side attacked the other's oil tankers...

, and Asia Minor.

In this contest between land power and sea power, Russia would find itself allied with France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

(a natural sea power, but in this case necessarily acting as a land power), arrayed against Germany, Britain, Japan, and the United States as sea powers. Further, Mahan conceived of a unified, modern state composed of Turkey

Turkey

Turkey , known officially as the Republic of Turkey , is a Eurasian country located in Western Asia and in East Thrace in Southeastern Europe...

, Syria, and Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a toponym for the area of the Tigris–Euphrates river system, largely corresponding to modern-day Iraq, northeastern Syria, southeastern Turkey and southwestern Iran.Widely considered to be the cradle of civilization, Bronze Age Mesopotamia included Sumer and the...

, possessing an efficiently organized army and navy to stand as a counterweight to Russian expansion.

Further dividing the map by geographic features, Mahan stated that the two most influential lines of division would be the Suez and Panama canal

Panama Canal

The Panama Canal is a ship canal in Panama that joins the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean and is a key conduit for international maritime trade. Built from 1904 to 1914, the canal has seen annual traffic rise from about 1,000 ships early on to 14,702 vessels measuring a total of 309.6...

s. As most developed nations and resources lay above the North-South division

North-South divide

The north–south divide is a socio-economic and political division that exists between the wealthy developed countries, known collectively as "the north", and the poorer developing countries , or "the south." Although most nations comprising the "North" are in fact located in the Northern Hemisphere ,...

, politics and commerce north of the two canals would be of much greater importance than those occurring south of the canals. As such, the great progress of historical development would not flow from north to south, but from east to west, in this case leading toward Asia as the locus of advance.

Halford J. Mackinder

His major work, Democratic ideals and reality: a study in the politics of reconstruction, appeared in 1919.[12] It presented his theory of the Heartland and made a case for fully taking into account geopolitical factors at the Paris Peace conference and contrasted (geographical) reality with Woodrow Wilson's idealism. The book's most famous quote was: "Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland; Who rules the Heartland commands the World Island; Who rules the World Island commands the World." This message was composed to convince the world statesmen at the Paris Peace conference of the crucial importance of Eastern Europe as the strategic route to the Heartland was interpreted as requiring a strip of buffer state to separate Germany and Russia. These were created by the peace negotiators but proved to be ineffective bulwarks in 1939 (although this may be seen as a failure of other, later statesmen during the interbellum). The principal concern of his work was to warn of the possibility of another major war (a warning also given by economist John Maynard Keynes).

Mackinder was anti-Bolshevik, and as British High Commissioner in Southern Russia in late 1919 and early 1920, he stressed the need for Britain to continue her support to the White Russian forces, which he attempted to unite.[13]

[edit] Significance of Mackinder

Mackinder's work paved the way for the establishment of geography as a distinct discipline in the United Kingdom. His role in fostering the teaching of geography is probably greater than that of any other single British geographer.

Whilst Oxford did not appoint a professor of Geography until 1934, both the University of Liverpool and University of Wales, Aberystwyth established professorial chairs in Geography in 1917. Mackinder himself became a full professor in Geography in the University of London (London School of Economics) in 1923.

Mackinder is often credited with introducing two new terms into the English language : "manpower", "heartland".

[edit] Influence on Nazi strategy

The Heartland Theory was enthusiastically taken up by the German school of Geopolitik, in particular by its main proponent Karl Haushofer. Whilst Geopolitik was later embraced by the German Nazi regime in the 1930s, Mackinder was always extremely critical of the German exploitation of his ideas. The German interpretation of the Heartland Theory is referred to explicitly (without mentioning the connection to Mackinder) in The Nazis Strike, the second of Frank Capra's Why We Fight series of American World War II propaganda films.

[edit] Influence on American strategy

The Heartland theory and more generally classical geopolitics and geostrategy were extremely influential in the making of US strategic policy during the period of the Cold War.[14]

[edit] Influence on later academics

Evidence of Mackinder’s Heartland Theory can be found in the works of geopolitician Dimitri Kitsikis, particularly in his geopolitical model "Intermediate Region".

Friedrich Ratzel

Karl Ritter

Karl Ritter was a German diplomat, ambassador to Brazil, a member of the Nazi Party, Special Envoy to the Munich Agreement, a senior official in the Foreign Office during World War II, and convicted war criminal in the Ministries Trial.-Life:Karl Ritter was a graduate in law, and was appointed to...

and Alexander von Humboldt

Alexander von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander Freiherr von Humboldt was a German naturalist and explorer, and the younger brother of the Prussian minister, philosopher and linguist Wilhelm von Humboldt...

, Friedrich Ratzel

Friedrich Ratzel

Friedrich Ratzel was a German geographer and ethnographer, notable for first using the term Lebensraum in the sense that the National Socialists later would.-Life:...

would lay the foundations for geopolitik

Geopolitik

Geopolitik is the branch of uniquely German geostrategy. It developed as a distinct strain of thought after Otto von Bismarck's unification of the German states but began its development in earnest only under Emperor Wilhelm II...

, Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

's unique strain of geopolitics

Geopolitics

Geopolitics, from Greek Γη and Πολιτική in broad terms, is a theory that describes the relation between politics and territory whether on local or international scale....

.

Ratzel wrote on the natural division between land powers and sea powers, agreeing with Mahan that sea power was self-sustaining, as the profit from trade

International trade

International trade is the exchange of capital, goods, and services across international borders or territories. In most countries, such trade represents a significant share of gross domestic product...

would support the development of a merchant marine. However, his key contribution were the development of the concepts of raum

Lebensraum

was one of the major political ideas of Adolf Hitler, and an important component of Nazi ideology. It served as the motivation for the expansionist policies of Nazi Germany, aiming to provide extra space for the growth of the German population, for a Greater Germany...

and the organic theory of the state

Organic theory of the state

The Organic Theory of the State is a species of political collectivism which maintains that the state transcends individuals within the State in power, right, or priority...

. He theorized that states were organic

Organic (model)

Organic describes forms, methods and patterns found in living systems such as the organisation of cells, to populations, communities, and ecosystems.Typically organic models stress the interdependence of the component parts, as well as their differentiation...

and growing, and that border

Border

Borders define geographic boundaries of political entities or legal jurisdictions, such as governments, sovereign states, federated states and other subnational entities. Some borders—such as a state's internal administrative borders, or inter-state borders within the Schengen Area—are open and...

s were only temporary, representing pauses in their natural movement. Raum was the land, spiritual

Spirituality

Spirituality can refer to an ultimate or an alleged immaterial reality; an inner path enabling a person to discover the essence of his/her being; or the “deepest values and meanings by which people live.” Spiritual practices, including meditation, prayer and contemplation, are intended to develop...

ly connected to a nation

Nation

A nation may refer to a community of people who share a common language, culture, ethnicity, descent, and/or history. In this definition, a nation has no physical borders. However, it can also refer to people who share a common territory and government irrespective of their ethnic make-up...

(in this case, the German peoples), from which the people could draw sustenance, find adjacent inferior nations which would support them, and which would be fertilized by their kultur (culture).

Ratzel's ideas would influence the works of his student Rudolf Kjellén, as well as those of General Karl Haushofer.

Rudolf Kjellén

Rudolf KjellénRudolf Kjellén

Johan Rudolf Kjellén was a Swedish political scientist and politician who first coined the term "geopolitics". His work was influenced by Friedrich Ratzel...

was a Swedish

Sweden

Sweden , officially the Kingdom of Sweden , is a Nordic country on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. Sweden borders with Norway and Finland and is connected to Denmark by a bridge-tunnel across the Öresund....

political scientist and student of Friedrich Ratzel. He first coined the term "geopolitics." His writings would play a decisive role in influencing General Karl Haushofer's geopolitik, and indirectly the future Nazi

Nazism

Nazism, the common short form name of National Socialism was the ideology and practice of the Nazi Party and of Nazi Germany...

foreign policy.

His writings focused on five central concepts that would underlie German geopolitik:

- Reich was a territorial concept that was composed of Raum (LebensraumLebensraumwas one of the major political ideas of Adolf Hitler, and an important component of Nazi ideology. It served as the motivation for the expansionist policies of Nazi Germany, aiming to provide extra space for the growth of the German population, for a Greater Germany...