Gideon Mantell

Encyclopedia

Gideon Algernon Mantell MRCS

FRS (Lewes

, 3 February 1790 – London, 10 November 1852) was an English

obstetrician, geologist

and palaeontologist

. His attempts to reconstruct the structure and life of Iguanodon

began the scientific study of dinosaurs: in 1822 he was responsible for the discovery (and the eventual identification) of the first fossil

teeth, and later much of the skeleton, of Iguanodon

. Mantell's work on the Cretaceous

of southern England was also important.

, Sussex

as the fifth-born child of Thomas Mantell, a shoemaker, and Sarah Austen. He was raised in a small cottage in St. Mary's Lane with his two sisters and four brothers. As a youth, he showed a particular interest in the field of geology. He explored pits and quarries in the surrounding areas, discovering ammonite

s, shells of sea urchin

s, fish bones, coral, and worn-out remains of dead animals. The Mantell children could not study at local grammar schools because the elder Mantell was a follower of the Methodist church

and the 12 free schools were reserved for children who had been brought up in the Anglican

faith. As a result, Gideon was educated at a dame school

in St. Mary's Lane, and learned basic reading and writing from an old woman. After the death of his teacher, Mantell was schooled by John Button, a philosophically radical Whig

who shared similar political beliefs with Mantell's father. Mantell spent two years with Button, before being sent to his uncle, a Baptist minister, in Swindon

, for a period of private study.

Mantell returned to Lewes at age 15. With the help of a local Whig party leader, Mantell secured an apprenticeship

with a local surgeon named James Moore. He served as an apprentice to Moore in Lewes for a period of five years, in which he took care of Mantell's dining, lodging and medical issues. Mantell's early apprenticeship duties included cleaning vials, as well as separating and arranging drugs

. Soon, he learned how to make pills and other pharmaceutical products

. He delivered Moore's medicines, kept his accounts, wrote out bills and extracted teeth from his patients. On 11 July 1807, Thomas Mantell died at the age of 57. He left his son some money for his future studies. As his time in apprenticeship began to wind down, he began to anticipate his medical education. He began to teach himself human anatomy

, and he ultimately detailed his new-found knowledge in a volume entitled The Anatomy of the Bones, and the Circulation of Blood, which contained dozens of detailed drawings of fetal and adult skeletal features. Soon, Mantell began his formal medical education in London. He received his diploma as a Member of the Royal College of Surgeons

in 1811. Four days later, he received a certificate from the Lying-in Charity for Married Women at Their Own Habitations that allowed him to act in midwifery

duties.

He returned to Lewes, and immediately formed a partnership with his former master, James Moore. In the wake of the cholera, typhoid and smallpox epidemics, Mantell found himself quite busy attending to more than 50 patients a day and delivering between 200 and 300 babies a year. As he later recalled, he would have to stay up for "six or seven nights in succession" due to his overwhelming doctoral duties. He was also able to increase his practice's profits from ₤250 to ₤750 a year. Although mainly occupied with running his busy country medical practice, he spent his little free time pursuing his passion, geology

, often working into the early hours of the morning, identifying fossil specimens he found at the marl pits in Hamsey

. In 1813, Mantell began to correspond with James Sowerby

. Sowerby, a naturalist and illustrator who catalogued fossil shells, received from Mantell many fossilized specimens. In appreciation for the specimens Mantell had provided, Sowerby named one of the species Ammonites mantelli. On 7 December, Mantell was elected as a fellow of the Linnean Society of London

. Two years later, he published his first paper, on the characteristics of the fossils found in the Lewes area.

In 1816, he married Mary Ann Woodhouse, the 20-year-old daughter of one of his former patients who had died three years earlier. Since she was not 21 and still technically a minor under English law, she had to obtain permission from her mother and a special licence to marry Mantell. After obtaining consent and the licence, she married Mantell on 4 May at St. Marylebone Church. That year, he purchased his own medical practice and took up an appointment at the Royal Artillery Hospital, at Ringmer

, Lewes.

Inspired by Mary Anning

Inspired by Mary Anning

's sensational discovery of a fossilised animal resembling a huge crocodile

(later identified as an ichthyosaur

) at Lyme Regis

in Dorset

, Mantell became passionately interested in the study of the fossilised animals and plants found in his area. The fossils he had collected from the region, near The Weald in Sussex, were from the chalk downlands

covering the county. The chalk is part of the Upper Cretaceous

System and the fossils it contains are marine

in origin. But by 1819, Mantell had begun acquiring fossils from a quarry, at Whitemans Green

, near Cuckfield

. These included the remains of terrestrial and freshwater

ecosystem

s, at a time when all the known fossil remains from Cretaceous England, hitherto, were marine in origin. He named the new strata the Strata of Tilgate Forest

, after an historical wooded area and it was later shown to belong to the Lower Cretaceous.

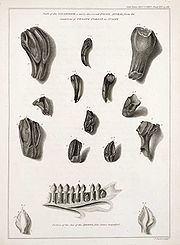

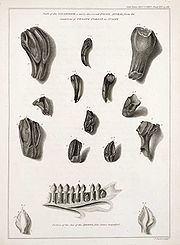

By 1820, he had started to find very large bones at Cuckfield, even larger than those discovered by William Buckland

, at Stonesfield

in Oxfordshire

. Then, in 1822, shortly before finishing his first book (The Fossils of South Downs), his wife found several large teeth (although some historians

contend that they were in fact discovered by himself), the origin of which he could not identify. In 1821 Mantell planned his next book on the geology of Sussex. It was an immediate success with two hundred subscribers including a letter from king George IV

at Carlton House Palace which read "His majesty is pleased to command that his name should be placed at the head of the subscription list for four copies."

How the king heard of Mantell is unknown, but Mantell's response is. Galvanised and encouraged, Mantell showed the teeth to other scientists but they were dismissed as belonging to a fish

or mammal

and from a more recent rock layer than the other Tilgate Forest fossils. The eminent French

anatomist, Georges Cuvier

, identified the teeth as those of a rhinoceros

.

Although according to Charles Lyell

, Cuvier made this statement after a late party and apparently had some doubts when reconsidering the matter when he awoke, fresh in the morning. "The next morning he told me that he was confident that it was something quite different." Strangely, this change of opinion did not make it back to Britain where Mantell was mocked for his error. Mantell was still convinced that the teeth had come from the Mesozoic

strata and finally recognized that they resembled those of the iguana

, but were twenty times larger. He surmised that the owner of the remains must have been at least 60 feet (18 metres) in length.

He tried in vain to convince his peers that the fossils were from Mesozoic strata, by carefully studying rock layers. William Buckland

He tried in vain to convince his peers that the fossils were from Mesozoic strata, by carefully studying rock layers. William Buckland

famously disputed Mantell's assertion, by claiming that the teeth were of fish.

When it was proved Mantell was correct the only question was what to call his new reptile. His original name was "Iguana-saurus" but he then received a letter from William Daniel Conybeare

, "Your discovery of the analogy between the Iguana and the fossil teeth is very interesting but the name you propose will hardly do, because it is equally applicable to the recent iguana. Iguanoides or Iguanodon would be better." Mantell took this advice to heart and called his creature Iguanodon.

Years later, Mantell had acquired enough fossil evidence to show that the dinosaur's forelimbs were much shorter than its hind legs, therefore proving they were not built like a mammal as claimed by Sir Richard Owen

. Mantell went on to demonstrate that fossil vertebrae, which Owen had attributed to a variety of different species, all belonged to Iguanodon. He also named a new genus of dinosaur called Hylaeosaurus

and as a result became an authority on prehistoric reptiles.

but his medical practice suffered. He was almost rendered destitute, but for the town's council who promptly transformed his house into a museum

. The museum in Brighton ultimately failed as a result of Mantell's habit of waiving the entrance fee. Finally destitute, Mantell offered to sell the entire collection to the British Museum, in 1838, for £

5,000, accepting the counter-offer of £4,000. He moved to Clapham Common

in South London, where he continued his work as a doctor.

Mary Mantell left her husband in 1839. That same year, Gideon's son Walter

emigrated to New Zealand

. Walter later sent his father some important fossils from New Zealand. Gideon's daughter, Hannah, died in 1840.

In 1841 Mantell was the victim of a terrible carriage accident on Clapham Common. Somehow he fell from his seat, became entangled in the reins and was dragged across the ground. Mantell suffered a debilitating spinal injury. Despite being bent, crippled and in constant pain, he continued to work with fossilized reptiles and published a number of scientific books and papers until his death. He moved to Pimlico

in 1844 and began to take opium

, as a painkiller, in 1845.

. Richard Owen, his long-time nemesis, had a section of Mantell's spine

removed, pickled and stored on a shelf at the Royal College of Surgeons of England. It remained there until 1969 when it was destroyed due to lack of space.

Mantell's surgery, on the south side of Clapham Common, is now a dental surgery.

At the time of his death Mantell was credited with discovering 4 of the 5 genera of dinosaurs then known.

In 2000, in commemoration of Mantell's discovery and his contribution to the science of palaeontology, the Mantell Monument was unveiled at Whiteman's Green, Cuckfield. The monument has been confirmed as the location of the Iguanodon fossils that Mantell first described in 1822.

He is buried at West Norwood Cemetery

within a sarcophagus

attributed to Amon Henry Wilds

that replicates the sanctuary of Natakamani

's Temple of Amun

(Coincidentally the name ammonite

is derived from Amun).

Membership of the Royal College of Surgeons

MRCS is a professional qualification for surgeons in the UK and IrelandIt means Member of the Royal College of Surgeons. In the United Kingdom, doctors who gain this qualification traditionally no longer use the title 'Dr' but start to use the title 'Mr', 'Mrs', 'Miss' or 'Ms'.There are 4 surgical...

FRS (Lewes

Lewes

Lewes is the county town of East Sussex, England and historically of all of Sussex. It is a civil parish and is the centre of the Lewes local government district. The settlement has a history as a bridging point and as a market town, and today as a communications hub and tourist-oriented town...

, 3 February 1790 – London, 10 November 1852) was an English

English people

The English are a nation and ethnic group native to England, who speak English. The English identity is of early mediaeval origin, when they were known in Old English as the Anglecynn. England is now a country of the United Kingdom, and the majority of English people in England are British Citizens...

obstetrician, geologist

Geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the solid and liquid matter that constitutes the Earth as well as the processes and history that has shaped it. Geologists usually engage in studying geology. Geologists, studying more of an applied science than a theoretical one, must approach Geology using...

and palaeontologist

Paleontology

Paleontology "old, ancient", ὄν, ὀντ- "being, creature", and λόγος "speech, thought") is the study of prehistoric life. It includes the study of fossils to determine organisms' evolution and interactions with each other and their environments...

. His attempts to reconstruct the structure and life of Iguanodon

Iguanodon

Iguanodon is a genus of ornithopod dinosaur that lived roughly halfway between the first of the swift bipedal hypsilophodontids and the ornithopods' culmination in the duck-billed dinosaurs...

began the scientific study of dinosaurs: in 1822 he was responsible for the discovery (and the eventual identification) of the first fossil

Fossil

Fossils are the preserved remains or traces of animals , plants, and other organisms from the remote past...

teeth, and later much of the skeleton, of Iguanodon

Iguanodon

Iguanodon is a genus of ornithopod dinosaur that lived roughly halfway between the first of the swift bipedal hypsilophodontids and the ornithopods' culmination in the duck-billed dinosaurs...

. Mantell's work on the Cretaceous

Cretaceous

The Cretaceous , derived from the Latin "creta" , usually abbreviated K for its German translation Kreide , is a geologic period and system from circa to million years ago. In the geologic timescale, the Cretaceous follows the Jurassic period and is followed by the Paleogene period of the...

of southern England was also important.

Early life and medical career

Mantell was born in LewesLewes

Lewes is the county town of East Sussex, England and historically of all of Sussex. It is a civil parish and is the centre of the Lewes local government district. The settlement has a history as a bridging point and as a market town, and today as a communications hub and tourist-oriented town...

, Sussex

Sussex

Sussex , from the Old English Sūþsēaxe , is an historic county in South East England corresponding roughly in area to the ancient Kingdom of Sussex. It is bounded on the north by Surrey, east by Kent, south by the English Channel, and west by Hampshire, and is divided for local government into West...

as the fifth-born child of Thomas Mantell, a shoemaker, and Sarah Austen. He was raised in a small cottage in St. Mary's Lane with his two sisters and four brothers. As a youth, he showed a particular interest in the field of geology. He explored pits and quarries in the surrounding areas, discovering ammonite

Ammonite

Ammonite, as a zoological or paleontological term, refers to any member of the Ammonoidea an extinct subclass within the Molluscan class Cephalopoda which are more closely related to living coleoids Ammonite, as a zoological or paleontological term, refers to any member of the Ammonoidea an extinct...

s, shells of sea urchin

Sea urchin

Sea urchins or urchins are small, spiny, globular animals which, with their close kin, such as sand dollars, constitute the class Echinoidea of the echinoderm phylum. They inhabit all oceans. Their shell, or "test", is round and spiny, typically from across. Common colors include black and dull...

s, fish bones, coral, and worn-out remains of dead animals. The Mantell children could not study at local grammar schools because the elder Mantell was a follower of the Methodist church

Methodism

Methodism is a movement of Protestant Christianity represented by a number of denominations and organizations, claiming a total of approximately seventy million adherents worldwide. The movement traces its roots to John Wesley's evangelistic revival movement within Anglicanism. His younger brother...

and the 12 free schools were reserved for children who had been brought up in the Anglican

Anglicanism

Anglicanism is a tradition within Christianity comprising churches with historical connections to the Church of England or similar beliefs, worship and church structures. The word Anglican originates in ecclesia anglicana, a medieval Latin phrase dating to at least 1246 that means the English...

faith. As a result, Gideon was educated at a dame school

Dame school

A Dame School was an early form of a private elementary school in English-speaking countries. They were usually taught by women and were often located in the home of the teacher.- Britain :...

in St. Mary's Lane, and learned basic reading and writing from an old woman. After the death of his teacher, Mantell was schooled by John Button, a philosophically radical Whig

British Whig Party

The Whigs were a party in the Parliament of England, Parliament of Great Britain, and Parliament of the United Kingdom, who contested power with the rival Tories from the 1680s to the 1850s. The Whigs' origin lay in constitutional monarchism and opposition to absolute rule...

who shared similar political beliefs with Mantell's father. Mantell spent two years with Button, before being sent to his uncle, a Baptist minister, in Swindon

Swindon

Swindon is a large town within the borough of Swindon and ceremonial county of Wiltshire, in South West England. It is midway between Bristol, west and Reading, east. London is east...

, for a period of private study.

Mantell returned to Lewes at age 15. With the help of a local Whig party leader, Mantell secured an apprenticeship

Apprenticeship

Apprenticeship is a system of training a new generation of practitioners of a skill. Apprentices or protégés build their careers from apprenticeships...

with a local surgeon named James Moore. He served as an apprentice to Moore in Lewes for a period of five years, in which he took care of Mantell's dining, lodging and medical issues. Mantell's early apprenticeship duties included cleaning vials, as well as separating and arranging drugs

Medication

A pharmaceutical drug, also referred to as medicine, medication or medicament, can be loosely defined as any chemical substance intended for use in the medical diagnosis, cure, treatment, or prevention of disease.- Classification :...

. Soon, he learned how to make pills and other pharmaceutical products

Pharmaceutical company

The pharmaceutical industry develops, produces, and markets drugs licensed for use as medications. Pharmaceutical companies are allowed to deal in generic and/or brand medications and medical devices...

. He delivered Moore's medicines, kept his accounts, wrote out bills and extracted teeth from his patients. On 11 July 1807, Thomas Mantell died at the age of 57. He left his son some money for his future studies. As his time in apprenticeship began to wind down, he began to anticipate his medical education. He began to teach himself human anatomy

Human anatomy

Human anatomy is primarily the scientific study of the morphology of the human body. Anatomy is subdivided into gross anatomy and microscopic anatomy. Gross anatomy is the study of anatomical structures that can be seen by the naked eye...

, and he ultimately detailed his new-found knowledge in a volume entitled The Anatomy of the Bones, and the Circulation of Blood, which contained dozens of detailed drawings of fetal and adult skeletal features. Soon, Mantell began his formal medical education in London. He received his diploma as a Member of the Royal College of Surgeons

Royal College of Surgeons of England

The Royal College of Surgeons of England is an independent professional body and registered charity committed to promoting and advancing the highest standards of surgical care for patients, regulating surgery, including dentistry, in England and Wales...

in 1811. Four days later, he received a certificate from the Lying-in Charity for Married Women at Their Own Habitations that allowed him to act in midwifery

Midwifery

Midwifery is a health care profession in which providers offer care to childbearing women during pregnancy, labour and birth, and during the postpartum period. They also help care for the newborn and assist the mother with breastfeeding....

duties.

He returned to Lewes, and immediately formed a partnership with his former master, James Moore. In the wake of the cholera, typhoid and smallpox epidemics, Mantell found himself quite busy attending to more than 50 patients a day and delivering between 200 and 300 babies a year. As he later recalled, he would have to stay up for "six or seven nights in succession" due to his overwhelming doctoral duties. He was also able to increase his practice's profits from ₤250 to ₤750 a year. Although mainly occupied with running his busy country medical practice, he spent his little free time pursuing his passion, geology

Geology

Geology is the science comprising the study of solid Earth, the rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which it evolves. Geology gives insight into the history of the Earth, as it provides the primary evidence for plate tectonics, the evolutionary history of life, and past climates...

, often working into the early hours of the morning, identifying fossil specimens he found at the marl pits in Hamsey

Hamsey

Hamsey is a civil parish in the Lewes District of East Sussex, England. It is located three miles north of Lewes on the Prime Meridian...

. In 1813, Mantell began to correspond with James Sowerby

James Sowerby

James Sowerby was an English naturalist and illustrator. Contributions to published works, such as A Specimen of the Botany of New Holland or English Botany, include his detailed and appealing plates...

. Sowerby, a naturalist and illustrator who catalogued fossil shells, received from Mantell many fossilized specimens. In appreciation for the specimens Mantell had provided, Sowerby named one of the species Ammonites mantelli. On 7 December, Mantell was elected as a fellow of the Linnean Society of London

Linnean Society of London

The Linnean Society of London is the world's premier society for the study and dissemination of taxonomy and natural history. It publishes a zoological journal, as well as botanical and biological journals...

. Two years later, he published his first paper, on the characteristics of the fossils found in the Lewes area.

In 1816, he married Mary Ann Woodhouse, the 20-year-old daughter of one of his former patients who had died three years earlier. Since she was not 21 and still technically a minor under English law, she had to obtain permission from her mother and a special licence to marry Mantell. After obtaining consent and the licence, she married Mantell on 4 May at St. Marylebone Church. That year, he purchased his own medical practice and took up an appointment at the Royal Artillery Hospital, at Ringmer

Ringmer

Ringmer is a village and civil parish in the Lewes District of East Sussex, England. The village is located three miles east of Lewes. Other small settlements in the parish include Upper Wellingham, Ashton Green, Broyle Side and Little Norlington....

, Lewes.

Geological research

Mary Anning

Mary Anning was a British fossil collector, dealer and palaeontologist who became known around the world for a number of important finds she made in the Jurassic age marine fossil beds at Lyme Regis where she lived...

's sensational discovery of a fossilised animal resembling a huge crocodile

Crocodile

A crocodile is any species belonging to the family Crocodylidae . The term can also be used more loosely to include all extant members of the order Crocodilia: i.e...

(later identified as an ichthyosaur

Ichthyosaur

Ichthyosaurs were giant marine reptiles that resembled fish and dolphins...

) at Lyme Regis

Lyme Regis

Lyme Regis is a coastal town in West Dorset, England, situated 25 miles west of Dorchester and east of Exeter. The town lies in Lyme Bay, on the English Channel coast at the Dorset-Devon border...

in Dorset

Dorset

Dorset , is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The county town is Dorchester which is situated in the south. The Hampshire towns of Bournemouth and Christchurch joined the county with the reorganisation of local government in 1974...

, Mantell became passionately interested in the study of the fossilised animals and plants found in his area. The fossils he had collected from the region, near The Weald in Sussex, were from the chalk downlands

Southern England Chalk Formation

The Chalk Formation of Southern England is a system of chalk downland in the south of England. The formation is perhaps best known for Salisbury Plain, the location of Stonehenge, the Isle of Wight and the twin ridgeways of the North Downs and South Downs....

covering the county. The chalk is part of the Upper Cretaceous

Cretaceous

The Cretaceous , derived from the Latin "creta" , usually abbreviated K for its German translation Kreide , is a geologic period and system from circa to million years ago. In the geologic timescale, the Cretaceous follows the Jurassic period and is followed by the Paleogene period of the...

System and the fossils it contains are marine

Ocean

An ocean is a major body of saline water, and a principal component of the hydrosphere. Approximately 71% of the Earth's surface is covered by ocean, a continuous body of water that is customarily divided into several principal oceans and smaller seas.More than half of this area is over 3,000...

in origin. But by 1819, Mantell had begun acquiring fossils from a quarry, at Whitemans Green

Whitemans Green

Whiteman's Green is a place in the north of the large village and civil parish of Cuckfield in the Mid Sussex District of West Sussex, England. It is located on the southern slopes of the Weald, two miles west of Haywards Heath and surrounded on other sides by Cuckfield Rural civil parish. The...

, near Cuckfield

Cuckfield

Cuckfield is a large village and civil parish in the Mid Sussex District of West Sussex, England, on the southern slopes of the Weald. It lies south of London, north of Brighton, and east northeast of the county town of Chichester. Nearby towns include Haywards Heath to the southeast and Burgess...

. These included the remains of terrestrial and freshwater

Freshwater

Fresh water is naturally occurring water on the Earth's surface in ice sheets, ice caps, glaciers, bogs, ponds, lakes, rivers and streams, and underground as groundwater in aquifers and underground streams. Fresh water is generally characterized by having low concentrations of dissolved salts and...

ecosystem

Ecosystem

An ecosystem is a biological environment consisting of all the organisms living in a particular area, as well as all the nonliving , physical components of the environment with which the organisms interact, such as air, soil, water and sunlight....

s, at a time when all the known fossil remains from Cretaceous England, hitherto, were marine in origin. He named the new strata the Strata of Tilgate Forest

Forest

A forest, also referred to as a wood or the woods, is an area with a high density of trees. As with cities, depending where you are in the world, what is considered a forest may vary significantly in size and have various classification according to how and what of the forest is composed...

, after an historical wooded area and it was later shown to belong to the Lower Cretaceous.

By 1820, he had started to find very large bones at Cuckfield, even larger than those discovered by William Buckland

William Buckland

The Very Rev. Dr William Buckland DD FRS was an English geologist, palaeontologist and Dean of Westminster, who wrote the first full account of a fossil dinosaur, which he named Megalosaurus...

, at Stonesfield

Stonesfield

Stonesfield is a village and civil parish about north of Witney in Oxfordshire.The village is on the crest of an escarpment. The parish extends mostly north and north-east of the village, in which directions the land rises gently and then descends to the Glyme at Glympton and Wootton about to the...

in Oxfordshire

Oxfordshire

Oxfordshire is a county in the South East region of England, bordering on Warwickshire and Northamptonshire , Buckinghamshire , Berkshire , Wiltshire and Gloucestershire ....

. Then, in 1822, shortly before finishing his first book (The Fossils of South Downs), his wife found several large teeth (although some historians

History

History is the discovery, collection, organization, and presentation of information about past events. History can also mean the period of time after writing was invented. Scholars who write about history are called historians...

contend that they were in fact discovered by himself), the origin of which he could not identify. In 1821 Mantell planned his next book on the geology of Sussex. It was an immediate success with two hundred subscribers including a letter from king George IV

George IV of the United Kingdom

George IV was the King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and also of Hanover from the death of his father, George III, on 29 January 1820 until his own death ten years later...

at Carlton House Palace which read "His majesty is pleased to command that his name should be placed at the head of the subscription list for four copies."

How the king heard of Mantell is unknown, but Mantell's response is. Galvanised and encouraged, Mantell showed the teeth to other scientists but they were dismissed as belonging to a fish

Fish

Fish are a paraphyletic group of organisms that consist of all gill-bearing aquatic vertebrate animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish, as well as various extinct related groups...

or mammal

Mammal

Mammals are members of a class of air-breathing vertebrate animals characterised by the possession of endothermy, hair, three middle ear bones, and mammary glands functional in mothers with young...

and from a more recent rock layer than the other Tilgate Forest fossils. The eminent French

French people

The French are a nation that share a common French culture and speak the French language as a mother tongue. Historically, the French population are descended from peoples of Celtic, Latin and Germanic origin, and are today a mixture of several ethnic groups...

anatomist, Georges Cuvier

Georges Cuvier

Georges Chrétien Léopold Dagobert Cuvier or Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric Cuvier , known as Georges Cuvier, was a French naturalist and zoologist...

, identified the teeth as those of a rhinoceros

Rhinoceros

Rhinoceros , also known as rhino, is a group of five extant species of odd-toed ungulates in the family Rhinocerotidae. Two of these species are native to Africa and three to southern Asia....

.

Although according to Charles Lyell

Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, Kt FRS was a British lawyer and the foremost geologist of his day. He is best known as the author of Principles of Geology, which popularised James Hutton's concepts of uniformitarianism – the idea that the earth was shaped by slow-moving forces still in operation...

, Cuvier made this statement after a late party and apparently had some doubts when reconsidering the matter when he awoke, fresh in the morning. "The next morning he told me that he was confident that it was something quite different." Strangely, this change of opinion did not make it back to Britain where Mantell was mocked for his error. Mantell was still convinced that the teeth had come from the Mesozoic

Mesozoic

The Mesozoic era is an interval of geological time from about 250 million years ago to about 65 million years ago. It is often referred to as the age of reptiles because reptiles, namely dinosaurs, were the dominant terrestrial and marine vertebrates of the time...

strata and finally recognized that they resembled those of the iguana

Iguana

Iguana is a herbivorous genus of lizard native to tropical areas of Central America and the Caribbean. The genus was first described in 1768 by Austrian naturalist Josephus Nicolaus Laurenti in his book Specimen Medicum, Exhibens Synopsin Reptilium Emendatam cum Experimentis circa Venena...

, but were twenty times larger. He surmised that the owner of the remains must have been at least 60 feet (18 metres) in length.

Recognition

William Buckland

The Very Rev. Dr William Buckland DD FRS was an English geologist, palaeontologist and Dean of Westminster, who wrote the first full account of a fossil dinosaur, which he named Megalosaurus...

famously disputed Mantell's assertion, by claiming that the teeth were of fish.

When it was proved Mantell was correct the only question was what to call his new reptile. His original name was "Iguana-saurus" but he then received a letter from William Daniel Conybeare

William Daniel Conybeare

William Daniel Conybeare FRS , dean of Llandaff, was an English geologist, palaeontologist and clergyman. He is probably best known for his ground-breaking work on marine reptile fossils in the 1820s, including important papers for the Geological Society of London on ichthyosaur anatomy and the...

, "Your discovery of the analogy between the Iguana and the fossil teeth is very interesting but the name you propose will hardly do, because it is equally applicable to the recent iguana. Iguanoides or Iguanodon would be better." Mantell took this advice to heart and called his creature Iguanodon.

Years later, Mantell had acquired enough fossil evidence to show that the dinosaur's forelimbs were much shorter than its hind legs, therefore proving they were not built like a mammal as claimed by Sir Richard Owen

Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen, FRS KCB was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and palaeontologist.Owen is probably best remembered today for coining the word Dinosauria and for his outspoken opposition to Charles Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection...

. Mantell went on to demonstrate that fossil vertebrae, which Owen had attributed to a variety of different species, all belonged to Iguanodon. He also named a new genus of dinosaur called Hylaeosaurus

Hylaeosaurus

Hylaeosaurus is the most obscure of the three animals used by Sir Richard Owen to first define the new group Dinosauria, in 1842. The original specimen, recovered by Gideon Mantell from the Tilgate Forest in the south of England in 1832, now resides in the Natural History Museum of London, where...

and as a result became an authority on prehistoric reptiles.

Later years

In 1833, Mantell relocated to BrightonBrighton

Brighton is the major part of the city of Brighton and Hove in East Sussex, England on the south coast of Great Britain...

but his medical practice suffered. He was almost rendered destitute, but for the town's council who promptly transformed his house into a museum

Museum

A museum is an institution that cares for a collection of artifacts and other objects of scientific, artistic, cultural, or historical importance and makes them available for public viewing through exhibits that may be permanent or temporary. Most large museums are located in major cities...

. The museum in Brighton ultimately failed as a result of Mantell's habit of waiving the entrance fee. Finally destitute, Mantell offered to sell the entire collection to the British Museum, in 1838, for £

Pound sterling

The pound sterling , commonly called the pound, is the official currency of the United Kingdom, its Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, British Antarctic Territory and Tristan da Cunha. It is subdivided into 100 pence...

5,000, accepting the counter-offer of £4,000. He moved to Clapham Common

Clapham Common

Clapham Common is an 89 hectare triangular area of grassland situated in south London, England. It was historically common land for the parishes of Battersea and Clapham, but was converted to parkland under the terms of the Metropolitan Commons Act 1878.43 hectares of the common are within the...

in South London, where he continued his work as a doctor.

Mary Mantell left her husband in 1839. That same year, Gideon's son Walter

Walter Mantell

Walter Baldock Durrant Mantell was a 19th century New Zealand scientist, politician, and Land Purchase Commissioner. He was a founder and first secretary of the New Zealand Institute, and discovered and collected Moa remains....

emigrated to New Zealand

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

. Walter later sent his father some important fossils from New Zealand. Gideon's daughter, Hannah, died in 1840.

In 1841 Mantell was the victim of a terrible carriage accident on Clapham Common. Somehow he fell from his seat, became entangled in the reins and was dragged across the ground. Mantell suffered a debilitating spinal injury. Despite being bent, crippled and in constant pain, he continued to work with fossilized reptiles and published a number of scientific books and papers until his death. He moved to Pimlico

Pimlico

Pimlico is a small area of central London in the City of Westminster. Like Belgravia, to which it was built as a southern extension, Pimlico is known for its grand garden squares and impressive Regency architecture....

in 1844 and began to take opium

Opium

Opium is the dried latex obtained from the opium poppy . Opium contains up to 12% morphine, an alkaloid, which is frequently processed chemically to produce heroin for the illegal drug trade. The latex also includes codeine and non-narcotic alkaloids such as papaverine, thebaine and noscapine...

, as a painkiller, in 1845.

Death and legacy

In 1852, Mantell took an overdose of opium and later lapsed into a coma. He died that afternoon. His post-mortem showed that he had been suffering from scoliosisScoliosis

Scoliosis is a medical condition in which a person's spine is curved from side to side. Although it is a complex three-dimensional deformity, on an X-ray, viewed from the rear, the spine of an individual with scoliosis may look more like an "S" or a "C" than a straight line...

. Richard Owen, his long-time nemesis, had a section of Mantell's spine

Vertebral column

In human anatomy, the vertebral column is a column usually consisting of 24 articulating vertebrae, and 9 fused vertebrae in the sacrum and the coccyx. It is situated in the dorsal aspect of the torso, separated by intervertebral discs...

removed, pickled and stored on a shelf at the Royal College of Surgeons of England. It remained there until 1969 when it was destroyed due to lack of space.

Mantell's surgery, on the south side of Clapham Common, is now a dental surgery.

At the time of his death Mantell was credited with discovering 4 of the 5 genera of dinosaurs then known.

In 2000, in commemoration of Mantell's discovery and his contribution to the science of palaeontology, the Mantell Monument was unveiled at Whiteman's Green, Cuckfield. The monument has been confirmed as the location of the Iguanodon fossils that Mantell first described in 1822.

He is buried at West Norwood Cemetery

West Norwood Cemetery

West Norwood Cemetery is a cemetery in West Norwood in London, England. It was also known as the South Metropolitan Cemetery.One of the first private landscaped cemeteries in London, it is one of the Magnificent Seven cemeteries of London, and is a site of major historical, architectural and...

within a sarcophagus

Sarcophagus

A sarcophagus is a funeral receptacle for a corpse, most commonly carved or cut from stone. The word "sarcophagus" comes from the Greek σαρξ sarx meaning "flesh", and φαγειν phagein meaning "to eat", hence sarkophagus means "flesh-eating"; from the phrase lithos sarkophagos...

attributed to Amon Henry Wilds

Amon Henry Wilds

Amon Henry Wilds was an English architect. He was part of a team of three architects and builders who—working together or independently at different times—were almost solely responsible for a surge in residential construction and development in early 19th-century Brighton, which until then had...

that replicates the sanctuary of Natakamani

Natakamani

Natakamani was a King of Kush who reigned from around or earlier than 1 BC to circa AD 20. Natakamani is the best attested ruler of the Meroitic period. He was born to queen Amanishakheto....

's Temple of Amun

Amun

Amun, reconstructed Egyptian Yamānu , was a god in Egyptian mythology who in the form of Amun-Ra became the focus of the most complex system of theology in Ancient Egypt...

(Coincidentally the name ammonite

Ammonite

Ammonite, as a zoological or paleontological term, refers to any member of the Ammonoidea an extinct subclass within the Molluscan class Cephalopoda which are more closely related to living coleoids Ammonite, as a zoological or paleontological term, refers to any member of the Ammonoidea an extinct...

is derived from Amun).

External links

- A History of Dinosaur Hunting and Reconstruction

- Schedule of Mantell related tours and events in and around Lewes and Brighton

- NNDB

- Gideon Mantell Biography at Strange Science.net

- Mantell and Wilds by the Friends of West Norwood Cemetery

- The Medals of Creation (1844) First Lessons in Geology and in the Study of Organic Remains by Gideon Mantell