George IV of the United Kingdom

Encyclopedia

George IV was the King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

and also of Hanover

from the death of his father, George III

, on 29 January 1820 until his own death ten years later. From 1811 until his accession, he served as Prince Regent

during his father's relapse into mental illness.

George IV led an extravagant lifestyle that contributed to the fashions of the British Regency. He was a patron of new forms of leisure, style and taste. He commissioned John Nash

to build the Royal Pavilion

in Brighton

and remodel Buckingham Palace

, and Sir Jeffry Wyatville to rebuild Windsor Castle

. He was instrumental in the foundation of the National Gallery, London

and King's College London

.

He had a poor relationship with both his father and his wife, Caroline of Brunswick

, whom he even forbade to attend his coronation. He introduced the unpopular Pains and Penalties Bill in a desperate, unsuccessful, attempt to divorce his wife.

For most of George's regency and reign, Lord Liverpool

controlled the government as Prime Minister

. George's governments, with little help from the King, presided over victory in the Napoleonic Wars

, negotiated the peace settlement, and attempted to deal with the social and economic malaise that followed. He had to accept George Canning

as foreign minister and later prime minister, and drop his opposition to Catholic Emancipation

.

His charm and culture earned him the title "the first gentleman of England", but his bad relations with his father and wife, and his dissolute way of life earned him the contempt of the people and dimmed the prestige of the monarchy. Taxpayers were angry at his wasteful spending in time of war. He did not provide national leadership in time of crisis, nor a role model for his people. His ministers found his behaviour selfish, unreliable, and irresponsible. At all times he was much under the influence of favourites.

and Duke of Rothesay

at birth; he was created Prince of Wales

and Earl of Chester

a few days afterwards. On 18 September of the same year, he was baptised by Thomas Secker

, Archbishop of Canterbury

. His godparents were the Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

(his maternal uncle, for whom the Duke of Devonshire

, Lord Chamberlain

, stood proxy), the Duke of Cumberland (his twice-paternal great-uncle), and the Dowager Princess of Wales (his paternal grandmother). George was a talented student, quickly learning to speak French, German and Italian in addition to his native English.

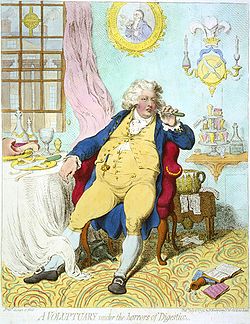

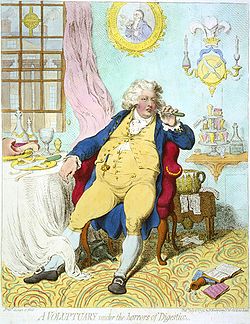

At the age of 18 he was given a separate establishment, and in dramatic contrast with his prosaic, scandal-free father threw himself with zest into a life of dissipation and wild extravagance involving heavy drinking and numerous mistresses and escapades. He was a witty conversationalist, drunk or sober, and showed good, but grossly expensive, taste in decorating his palace. This was particularly in poor judgement in light of the extraordinary poverty of many London residents including large numbers of children and adults living on the streets with no hope of shelter, freezing to death in winter or dying of starvation.

The Prince turned 21 in 1783, and obtained a grant of £60,000 (equal to £ today) from Parliament and an annual income of £50,000 (equal to £ today) from his father. It was far too little for his needs. (The stables alone cost £31,000 a year.) He then established his residence in Carlton House, where he lived a profligate life. Animosity developed between the Prince and his father, who desired more frugal behaviour on the part of the heir-apparent. The King, a political conservative, was also alienated by the Prince's adherence to Charles James Fox

and other radically inclined politicians.

Soon after he reached the age of 21, the Prince became infatuated with Maria Fitzherbert. She was a commoner, six years his elder, twice widowed, and a Roman Catholic. Despite her complete unsuitability, the Prince was determined to marry her. This was in spite of the Act of Settlement 1701

, which barred the spouse of a Catholic from succeeding to the throne, and the Royal Marriages Act 1772

, which prohibited his marriage without the consent of the King, which would never have been granted.

Nevertheless, the couple contracted a marriage on 15 December 1785 at her house in Park Street, Mayfair

. Legally the union was void, as the King's consent was not granted (and never even requested). However, Mrs. Fitzherbert believed that she was the Prince's canonical

and true wife, holding the law of the Church to be superior to the law of the State. For political reasons, the union remained secret and Mrs. Fitzherbert promised not to reveal it.

The Prince was plunged into debt by his exorbitant lifestyle. His father refused to assist him, forcing him to quit Carlton House and live at Mrs. Fitzherbert's residence. In 1787, the Prince's political allies proposed to relieve his debts with a parliamentary grant. The Prince's relationship with Mrs. Fitzherbert was suspected, and revelation of the illegal marriage would have scandalised the nation and doomed any parliamentary proposal to aid him. Acting on the Prince's authority, the Whig leader Charles James Fox declared that the story was a calumny. Mrs. Fitzherbert was not pleased with the public denial of the marriage in such vehement terms and contemplated severing her ties to the Prince. He appeased her by asking another Whig, Richard Brinsley Sheridan

, to restate Fox's forceful declaration in more careful words. Parliament, meanwhile, granted the Prince £161,000 (equal to £ today) to pay his debts and £60,000 (equal to £ today) for improvements to Carlton House.

. In the summer of 1788 his mental health deteriorated, but he was nonetheless able to discharge some of his duties and to declare Parliament prorogued from 25 September to 20 November. During the prorogation George III became deranged, posing a threat to his own life, and when Parliament reconvened in November the King could not deliver the customary Speech from the Throne

during the State Opening of Parliament

. Parliament found itself in an untenable position; according to long-established law it could not proceed to any business until the delivery of the King's Speech at a State Opening.

Although arguably barred from doing so, Parliament began debating a Regency. In the House of Commons, Charles James Fox declared his opinion that the Prince of Wales was automatically entitled to exercise sovereignty during the King's incapacity. A contrasting opinion was held by the Prime Minister, William Pitt the Younger

, who argued that, in the absence of a statute to the contrary, the right to choose a Regent belonged to Parliament alone. He even stated that, without parliamentary authority "the Prince of Wales had no more right...to assume the government, than any other individual subject of the country." Though disagreeing on the principle underlying a Regency, Pitt agreed with Fox that the Prince of Wales would be the most convenient choice for a Regent.

The Prince of Wales—though offended by Pitt's boldness—did not lend his full support to Fox's approach. The prince's brother, Prince Frederick, Duke of York, declared that the prince would not attempt to exercise any power without previously obtaining the consent of Parliament. Following the passage of preliminary resolutions Pitt outlined a formal plan for the Regency, suggesting that the powers of the Prince of Wales be greatly limited. Among other things, the Prince of Wales would not be able either to sell the King's property or to grant a peerage

to anyone other than a child of the King. The Prince of Wales denounced Pitt's scheme, declaring it a "project for producing weakness, disorder, and insecurity in every branch of the administration of affairs." In the interests of the nation, both factions agreed to compromise.

A significant technical impediment to any Regency Bill involved the lack of a Speech from the Throne, which was necessary before Parliament could proceed to any debates or votes. The Speech was normally delivered by the King, but could also be delivered by royal representatives known as Lords Commissioners

; but no document could empower the Lords Commissioners to act unless the Great Seal of the Realm

was affixed to it. The Seal could not be legally affixed without the prior authorisation of the Sovereign. Pitt and his fellow ministers ignored the last requirement and instructed the Lord Chancellor

to affix the Great Seal without the King's consent, as the act of affixing the Great Seal in itself gave legal force to the Bill. This legal fiction

was denounced by Edmund Burke

as a "glaring falsehood", as a "palpable absurdity", and even as a "forgery, fraud". The Prince of Wales's brother, the Duke of York, described the plan as "unconstitutional and illegal." Nevertheless, others in Parliament felt that such a scheme was necessary to preserve an effective government. Consequently on 3 February 1789, more than two months after it had convened, Parliament was formally opened by an "illegal" group of Lords Commissioners. The Regency Bill was introduced, but before it could be passed the King recovered. The King declared retroactively that the instrument authorising the Lords Commissioners to act was valid.

. In 1795, the Prince of Wales acquiesced, and they were married on 8 April 1795 at the Chapel Royal

, St James's Palace. The marriage, however, was disastrous; each party was unsuited to the other. The two were formally separated after the birth of their only child, Princess Charlotte, in 1796, and remained separated thereafter. The Prince of Wales remained attached to Mrs. Fitzherbert for the rest of his life, despite several periods of estrangement.

George's mistresses included Mary Robinson

, an actress who was bought off with a generous pension when she threatened to sell his letters to the newspapers; Grace Elliott

, the divorced wife of a physician; and Frances Villiers, Countess of Jersey

, who dominated his life for some years. In later life, his mistresses were the Marchioness of Hertford and the Marchioness Conyngham

, who were both married to aristocrats.

George may have fathered several illegitimate children. James Ord (born 1786)—who moved to the United States and became a Jesuit priest—was reportedly his son by Mrs. Fitzherbert. The King, late in life, told a friend that he had a son who was a naval officer in the West Indies, whose identity has been tentatively established as Capt. Henry A. F. Hervey (1786–1824), reportedly George's child by the songwriter Lady Anne Lindsay (later Barnard)

, a daughter of the 5th Earl of Balcarres

. Other reported offspring include Major G. S. Crole, the son of theatre manager's daughter Eliza Crole or Fox; William Hampshire, the son of publican's daughter Sarah Brown; and Charles "Beau" Candy, the son of a Frenchwoman with that surname. Anthony Camp, Director of Research at the Society of Genealogists

, has dismissed the claims that George IV was the father of Ord, Hervey, Hampshire and Candy as fictitious.

The problem of the Prince of Wales's debts, which amounted to the extraordinary sum of £630,000 (equal to £ today) in 1795, was solved (at least temporarily) by Parliament. Being unwilling to make an outright grant to relieve these debts, it provided him an additional sum of £65,000 (equal to £ today) per annum. In 1803, a further £60,000 (equal to £ today) was added, and the Prince of Wales's debts of 1795 were finally cleared in 1806, although the debts he had incurred since 1795 remained.

In 1804 a dispute arose over the custody of Princess Charlotte, which led to her being placed in the care of the King, George III. It also led to a Parliamentary Commission of Enquiry into Princess Caroline's conduct after the Prince of Wales accused her of having an illegitimate son. The investigation cleared Caroline of the charge but still revealed her behaviour to be extraordinarily indiscreet.

. Parliament agreed to follow the precedent of 1788; without the King's consent, the Lord Chancellor affixed the Great Seal of the Realm to letters patent

naming Lords Commissioners. The Lords Commissioners, in the name of the King, signified the granting of the Royal Assent

to a bill that became the Regency Act of 1811. Parliament restricted some of the powers of the Prince Regent (as the Prince of Wales became known). The constraints expired one year after the passage of the Act. The Prince of Wales became Prince Regent on 5 February 1811.

The Regent let his ministers take full charge of government affairs, playing a far lesser role than his father. The principle that the crown accepts as prime minister the person who controls a majority in the House of Commons, whether the king personally favours him or not, became established. His governments, with little help from the Regent, presided over victory in the Napoleonic Wars, negotiated the peace settlement, and attempted to deal with the social and economic malaise that followed. One of the most important political conflicts facing the country concerned Catholic emancipation

, the movement to relieve Roman Catholics of various political disabilities. The Tories, led by the Prime Minister, Spencer Perceval

, were opposed to Catholic emancipation, while the Whigs supported it. At the beginning of the Regency, the Prince of Wales was expected to support the Whig leader, William Wyndham Grenville, 1st Baron Grenville

. He did not, however, immediately put Lord Grenville and the Whigs in office. Influenced by his mother, he claimed that a sudden dismissal of the Tory government would exact too great a toll on the health of the King (a steadfast supporter of the Tories), thereby eliminating any chance of a recovery.

In 1812, when it appeared highly unlikely that the King would recover, the Prince of Wales again failed to appoint a new Whig administration. Instead, he asked the Whigs to join the existing ministry under Spencer Perceval. The Whigs, however, refused to co-operate because of disagreements over Catholic emancipation. Grudgingly, the Prince of Wales allowed Perceval to continue as Prime Minister.

In 1812, when it appeared highly unlikely that the King would recover, the Prince of Wales again failed to appoint a new Whig administration. Instead, he asked the Whigs to join the existing ministry under Spencer Perceval. The Whigs, however, refused to co-operate because of disagreements over Catholic emancipation. Grudgingly, the Prince of Wales allowed Perceval to continue as Prime Minister.

On 10 May 1812, Spencer Perceval was assassinated by John Bellingham

. The Prince Regent was prepared to reappoint all the members of the Perceval ministry under a new leader. The House of Commons formally declared its desire for a "strong and efficient administration", so the Prince Regent then offered leadership of the government to Richard Wellesley, 1st Marquess Wellesley

, and afterwards to Francis Rawdon-Hastings, 2nd Earl of Moira

. He doomed the attempts of both to failure, however, by forcing each to construct a bipartisan ministry at a time when neither party wished to share power with the other. Possibly using the failure of the two peers as a pretext, the Prince Regent immediately reappointed the Perceval administration, with Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool, as Prime Minister.

The Tories, unlike Whigs such as Earl Grey

, sought to continue the vigorous prosecution of the war in Continental Europe against the powerful and aggressive Emperor of the French, Napoleon I

. An anti-French alliance, which included Russia, Prussia

, Austria, Britain and several smaller countries, defeated Napoleon in 1814. In the subsequent Congress of Vienna

, it was decided that the Electorate of Hanover

, a state that had shared a monarch with Britain since 1714, would be raised to a Kingdom, known as the Kingdom of Hanover

. Napoleon returned from exile in 1815, but was defeated at the Battle of Waterloo

by Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

, brother of Marquess Wellesley. That same year the British-American War of 1812

came to an end, with neither side victorious.

During this period George took an active interest in matters of style and taste, and his associates such as the dandy Beau Brummell

and the architect John Nash

created the Regency style. In London Nash designed the Regency terraces of Regent's Park

and Regent Street

. George took up the new idea of the seaside spa and had the Brighton Pavilion developed as a fantastical seaside palace, adapted by Nash in the "Indian Gothic" style inspired loosely by the Taj Mahal

, with extravagant "Indian" and "Chinese" interiors.

When George III died in 1820, the Prince Regent ascended the throne as George IV, with no real change in his powers. By the time of his accession, he was obese and possibly addicted to laudanum

When George III died in 1820, the Prince Regent ascended the throne as George IV, with no real change in his powers. By the time of his accession, he was obese and possibly addicted to laudanum

.

George IV's relationship with his wife Caroline

had deteriorated by the time of his accession. They had lived separately since 1796, and both were having affairs. In 1814, Caroline left the United Kingdom for continental Europe, but she chose to return for her husband's coronation, and to publicly assert her rights as Queen Consort. However, George IV refused to recognise Caroline as Queen, and commanded British ambassadors to ensure that monarchs in foreign courts did the same. By royal command, Caroline's name was omitted from the Book of Common Prayer

, the liturgy

of the Church of England

. The King sought a divorce, but his advisors suggested that any divorce proceedings might involve the publication of details relating to the King's own adulterous relationships. Therefore, he requested and ensured the introduction of the Pains and Penalties Bill 1820

, under which Parliament could have imposed legal penalties without a trial in a court of law. The bill would have annulled the marriage and stripped Caroline of the title of Queen. The bill proved extremely unpopular with the public, and was withdrawn from Parliament. George IV decided, nonetheless, to exclude his wife from his coronation at Westminster Abbey

, on 19 July 1821. Caroline fell ill that day and died on 7 August; during her final illness she often stated that she thought she had been poisoned.

George's coronation was a magnificent and expensive affair, costing about £243,000 (approximately £ as of ), (for comparison, his father's coronation had only cost about £10,000, equal to £ today). Despite the enormous cost, it was a popular event. In 1821 the King became the first monarch to pay a state visit to Ireland since Richard II of England

George's coronation was a magnificent and expensive affair, costing about £243,000 (approximately £ as of ), (for comparison, his father's coronation had only cost about £10,000, equal to £ today). Despite the enormous cost, it was a popular event. In 1821 the King became the first monarch to pay a state visit to Ireland since Richard II of England

. The following year he visited Edinburgh

for "one and twenty daft days." His visit to Scotland

, organised by Sir Walter Scott

, was the first by a reigning British monarch since the mid-17th century.

George IV spent most of his later reign in seclusion at Windsor Castle

George IV spent most of his later reign in seclusion at Windsor Castle

, but he continued to intervene in politics. At first it was believed that he would support Catholic Emancipation

, as he had proposed a Catholic Emancipation Bill for Ireland in 1797, but his anti-Catholic views became clear in 1813 when he privately canvassed against the ultimately defeated Catholic Relief Bill of 1813. By 1824 he was denouncing Catholic emancipation in public. Having taken the coronation oath on his accession, George now argued that he had sworn to uphold the Protestant faith, and could not support any pro-Catholic measures. The influence of the Crown was so great, and the will of the Tories under Prime Minister Lord Liverpool

so strong, that Catholic emancipation seemed hopeless. In 1827, however, Lord Liverpool retired, to be replaced by the pro-emancipation Tory George Canning

. When Canning entered office, the King, hitherto content with privately instructing his ministers on the Catholic Question, thought it fit to make a public declaration to the effect that his sentiments on the question were those of his revered father, George III.

Canning's views on the Catholic Question were not well received by the most conservative Tories, including the Duke of Wellington. As a result the ministry was forced to include Whigs. Canning died later in that year, leaving Frederick John Robinson, 1st Viscount Goderich

to lead the tenuous Tory-Whig coalition. Lord Goderich left office in 1828, to be succeeded by the Duke of Wellington, who had by that time accepted that the denial of some measure of relief to Roman Catholics was politically untenable. With great difficulty Wellington obtained the King's consent to the introduction of a Catholic Relief Bill on 29 January 1829. Under pressure from his fanatically anti-Catholic brother, the Duke of Cumberland

, the King withdrew his approval and in protest the Cabinet resigned en masse on 4 March. The next day the King, now under intense political pressure, reluctantly agreed to the Bill and the ministry remained in power. Royal Assent was finally granted to the Catholic Relief Act

on 13 April.

George IV's heavy drinking and indulgent lifestyle had taken their toll of his health by the late 1820s. His taste for huge banquets and copious amounts of alcohol caused him to become obese, making him the target of ridicule on the rare occasions that he did appear in public. By 1797 his weight had reached 17 stone 7 pounds (111 kg or 245 lb), and by 1824 his corset was made for a waist of 50 inches (127 cm). He suffered from gout

, arteriosclerosis

, dropsy and possible porphyria

; he would spend whole days in bed and suffered spasms of breathlessness that would leave him half-asphyxiated. Some accounts claim that he showed signs of mental instability towards the end of his life, although less extreme than his father; for example, he sometimes claimed that he had been at the Battle of Waterloo

, which may have been a sign of dementia

or just a joke to annoy the Duke of Wellington

. He died at about half-past three in the morning of 26 June 1830 at Windsor Castle; he called out "Good God, what is this?" clasped his page's hand and said "my boy, this is death." He was buried in St George's Chapel, Windsor on 15 July.

His only legitimate child, Princess Charlotte Augusta of Wales

, had died from post-partum complications in 1817, after delivering a still-born son. The second son of George III, Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany

, had died in 1827. He was therefore succeeded by another brother, the third son of George III, Prince William, Duke of Clarence

, who reigned as William IV.

His last years were marked by increasing physical and mental decay and withdrawal from public affairs. Privately a senior aide to the king confided to his diary: "A more contemptible, cowardly, selfish, unfeeling dog does not exist....There have been good and wise kings but not many of them...and this I believe to be one of the worst."

His last years were marked by increasing physical and mental decay and withdrawal from public affairs. Privately a senior aide to the king confided to his diary: "A more contemptible, cowardly, selfish, unfeeling dog does not exist....There have been good and wise kings but not many of them...and this I believe to be one of the worst."

On George's death The Times

captured elite opinion succinctly: "There never was an individual less regretted by his fellow-creatures than this deceased king. What eye has wept for him? What heart has heaved one throb of unmercenary sorrow? ... If he ever had a friend – a devoted friend in any rank of life – we protest that the name of him or her never reached us."

During the political crisis caused by Catholic emancipation, the Duke of Wellington said that George was "the worst man he ever fell in with his whole life, the most selfish, the most false, the most ill-natured, the most entirely without one redeeming quality", but his eulogy delivered in the House of Lords

called George "the most accomplished man of his age" and praised his knowledge and talent. Wellington's true feelings probably lie somewhere between these two extremes; as he said later, George was "a magnificent patron of the arts ... the most extraordinary compound of talent, wit, buffoonery, obstinacy, and good feeling—in short a medley of the most opposite qualities, with a great preponderence of good—that I ever saw in any character in my life."

George IV was described as the "First Gentleman of England" on account of his style and manners. Certainly, he possessed many good qualities; he was bright, clever, and knowledgeable. However, his laziness and gluttony led him to squander much of his talent. As The Times once wrote, he would always prefer "a girl and a bottle to politics and a sermon."

There are many statues of George IV, a large number of which were erected during his reign. In the United Kingdom, they include a bronze

statue of him on horseback by Sir Francis Chantrey in Trafalgar Square

and another outside the Royal Pavilion in Brighton

.

In Edinburgh

, "George IV Bridge" is a main street linking the Old Town High Street to the north over the ravine of the Cowgate, designed by the architect Thomas Hamilton

in 1829 and completed in 1835. King's Cross, now a major transport hub sitting on the border of Camden

and Islington

in north London, takes its name from a short-lived monument erected to George IV in the early 1830s.

The Regency period saw a shift in fashion that was largely determined by George. After political opponents put a tax on wig powder, he abandoned wearing a powdered wig in favour of natural hair. He wore darker colours than had been previously fashionable as they helped to disguise his size, favoured pantaloons and trousers over knee breeches because they were looser, and popularised a high collar with neck cloth because it hid his double chin. His visit to Scotland in 1822 led to the revival, if not the creation, of Scottish tartan

dress as it is known today.

Under the Act of Parliament that instituted the Regency, the Prince's formal title as Regent was "Regent of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland", and thus, during the Regency period his formal style was "His Royal Highness The Prince of Wales, Regent of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland". The simplified style "His Royal Highness The Prince Regent" was more common even in official documents. George IV's official style as King of the United Kingdom was "George the Fourth, by the Grace of God, of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland King, Defender of the Faith". While heir apparent and before his accession as king, he was also the Crown Prince of Hanover.

(with an inescutcheon of Gules

plain in the Hanoverian quarter

), differenced by a label of three points Argent

. The arms included the royal crest

and supporters but with the single arched coronet

of his rank, all charged on the shoulder with a similar label

. His arms followed the change in the royal arms in 1801, when the Hanoverian quarter became an inescutcheon and the French quarter was dropped altogether. The 1816 alteration did not affect him as it only applied to the arms of the King.

As king his arms were those of his two kingdoms, the United Kingdom and Hanover, superimposed: Quarterly, I and IV Gules three lions passant guardant in pale

Or

(for England); II Or a lion rampant rampant within a tressure flory-counter-flory Gules (for Scotland

); III Azure a harp Or stringed Argent (for Ireland

); overall an escutcheon tierced per pale and per chevron

(for Hanover), I Gules two lions passant guardant Or (for Brunswick), II Or a semy of hearts Gules a lion rampant Azure (for Lüneburg), III Gules a horse courant Argent (for Westphalia

), overall an inescutcheon Gules charged with the crown of Charlemagne Or, the whole escutcheon surmounted by a crown.

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

and also of Hanover

Kingdom of Hanover

The Kingdom of Hanover was established in October 1814 by the Congress of Vienna, with the restoration of George III to his Hanoverian territories after the Napoleonic era. It succeeded the former Electorate of Brunswick-Lüneburg , and joined with 38 other sovereign states in the German...

from the death of his father, George III

George III of the United Kingdom

George III was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of these two countries on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland until his death...

, on 29 January 1820 until his own death ten years later. From 1811 until his accession, he served as Prince Regent

Prince Regent

A prince regent is a prince who rules a monarchy as regent instead of a monarch, e.g., due to the Sovereign's incapacity or absence ....

during his father's relapse into mental illness.

George IV led an extravagant lifestyle that contributed to the fashions of the British Regency. He was a patron of new forms of leisure, style and taste. He commissioned John Nash

John Nash (architect)

John Nash was a British architect responsible for much of the layout of Regency London.-Biography:Born in Lambeth, London, the son of a Welsh millwright, Nash trained with the architect Sir Robert Taylor. He established his own practice in 1777, but his career was initially unsuccessful and...

to build the Royal Pavilion

Royal Pavilion

The Royal Pavilion is a former royal residence located in Brighton, England. It was built in three campaigns, beginning in 1787, as a seaside retreat for George, Prince of Wales, from 1811 Prince Regent. It is often referred to as the Brighton Pavilion...

in Brighton

Brighton

Brighton is the major part of the city of Brighton and Hove in East Sussex, England on the south coast of Great Britain...

and remodel Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace, in London, is the principal residence and office of the British monarch. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is a setting for state occasions and royal hospitality...

, and Sir Jeffry Wyatville to rebuild Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a medieval castle and royal residence in Windsor in the English county of Berkshire, notable for its long association with the British royal family and its architecture. The original castle was built after the Norman invasion by William the Conqueror. Since the time of Henry I it...

. He was instrumental in the foundation of the National Gallery, London

National Gallery, London

The National Gallery is an art museum on Trafalgar Square, London, United Kingdom. Founded in 1824, it houses a collection of over 2,300 paintings dating from the mid-13th century to 1900. The gallery is an exempt charity, and a non-departmental public body of the Department for Culture, Media...

and King's College London

King's College London

King's College London is a public research university located in London, United Kingdom and a constituent college of the federal University of London. King's has a claim to being the third oldest university in England, having been founded by King George IV and the Duke of Wellington in 1829, and...

.

He had a poor relationship with both his father and his wife, Caroline of Brunswick

Caroline of Brunswick

Caroline of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel was the Queen consort of King George IV of the United Kingdom from 29 January 1820 until her death...

, whom he even forbade to attend his coronation. He introduced the unpopular Pains and Penalties Bill in a desperate, unsuccessful, attempt to divorce his wife.

For most of George's regency and reign, Lord Liverpool

Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool

Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool KG PC was a British politician and the longest-serving Prime Minister of the United Kingdom since the Union with Ireland in 1801. He was 42 years old when he became premier in 1812 which made him younger than all of his successors to date...

controlled the government as Prime Minister

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and...

. George's governments, with little help from the King, presided over victory in the Napoleonic Wars

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars were a series of wars declared against Napoleon's French Empire by opposing coalitions that ran from 1803 to 1815. As a continuation of the wars sparked by the French Revolution of 1789, they revolutionised European armies and played out on an unprecedented scale, mainly due to...

, negotiated the peace settlement, and attempted to deal with the social and economic malaise that followed. He had to accept George Canning

George Canning

George Canning PC, FRS was a British statesman and politician who served as Foreign Secretary and briefly Prime Minister.-Early life: 1770–1793:...

as foreign minister and later prime minister, and drop his opposition to Catholic Emancipation

Catholic Emancipation

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in Great Britain and Ireland in the late 18th century and early 19th century which involved reducing and removing many of the restrictions on Roman Catholics which had been introduced by the Act of Uniformity, the Test Acts and the penal laws...

.

His charm and culture earned him the title "the first gentleman of England", but his bad relations with his father and wife, and his dissolute way of life earned him the contempt of the people and dimmed the prestige of the monarchy. Taxpayers were angry at his wasteful spending in time of war. He did not provide national leadership in time of crisis, nor a role model for his people. His ministers found his behaviour selfish, unreliable, and irresponsible. At all times he was much under the influence of favourites.

Early life

George was born at St James's Palace, London, on 12 August 1762. As the eldest son of a British sovereign, he automatically became Duke of CornwallDuke of Cornwall

The Duchy of Cornwall was the first duchy created in the peerage of England.The present Duke of Cornwall is The Prince of Wales, the eldest son of Queen Elizabeth II, the reigning British monarch .-History:...

and Duke of Rothesay

Duke of Rothesay

Duke of Rothesay was a title of the heir apparent to the throne of the Kingdom of Scotland before 1707, of the Kingdom of Great Britain from 1707 to 1801, and now of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland....

at birth; he was created Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales is a title traditionally granted to the heir apparent to the reigning monarch of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the 15 other independent Commonwealth realms...

and Earl of Chester

Earl of Chester

The Earldom of Chester was one of the most powerful earldoms in medieval England. Since 1301 the title has generally been granted to heirs-apparent to the English throne, and from the late 14th century it has been given only in conjunction with that of Prince of Wales.- Honour of Chester :The...

a few days afterwards. On 18 September of the same year, he was baptised by Thomas Secker

Thomas Secker

Thomas Secker , Archbishop of Canterbury, was born at Sibthorpe, Nottinghamshire.-Early life and studies:In 1699, Secker went to Richard Brown's free school in Chesterfield, staying with his half-sister and her husband, Elizabeth and Richard Milnes...

, Archbishop of Canterbury

Archbishop of Canterbury

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. In his role as head of the Anglican Communion, the archbishop leads the third largest group...

. His godparents were the Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

Adolf Friedrich IV, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

Adolphus Frederick IV was a Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz.-Biography:He was born in Mirow to Charles Louis Frederick of Mecklenburg and his wife Princess Elizabeth Albertine of Saxe-Hildburghausen...

(his maternal uncle, for whom the Duke of Devonshire

William Cavendish, 4th Duke of Devonshire

William Cavendish, 4th Duke of Devonshire, KG, PC , styled Lord Cavendish before 1729 and Marquess of Hartington between 1729 and 1755, was a British Whig statesman who was briefly nominal Prime Minister of Great Britain...

, Lord Chamberlain

Lord Chamberlain

The Lord Chamberlain or Lord Chamberlain of the Household is one of the chief officers of the Royal Household in the United Kingdom and is to be distinguished from the Lord Great Chamberlain, one of the Great Officers of State....

, stood proxy), the Duke of Cumberland (his twice-paternal great-uncle), and the Dowager Princess of Wales (his paternal grandmother). George was a talented student, quickly learning to speak French, German and Italian in addition to his native English.

At the age of 18 he was given a separate establishment, and in dramatic contrast with his prosaic, scandal-free father threw himself with zest into a life of dissipation and wild extravagance involving heavy drinking and numerous mistresses and escapades. He was a witty conversationalist, drunk or sober, and showed good, but grossly expensive, taste in decorating his palace. This was particularly in poor judgement in light of the extraordinary poverty of many London residents including large numbers of children and adults living on the streets with no hope of shelter, freezing to death in winter or dying of starvation.

The Prince turned 21 in 1783, and obtained a grant of £60,000 (equal to £ today) from Parliament and an annual income of £50,000 (equal to £ today) from his father. It was far too little for his needs. (The stables alone cost £31,000 a year.) He then established his residence in Carlton House, where he lived a profligate life. Animosity developed between the Prince and his father, who desired more frugal behaviour on the part of the heir-apparent. The King, a political conservative, was also alienated by the Prince's adherence to Charles James Fox

Charles James Fox

Charles James Fox PC , styled The Honourable from 1762, was a prominent British Whig statesman whose parliamentary career spanned thirty-eight years of the late 18th and early 19th centuries and who was particularly noted for being the arch-rival of William Pitt the Younger...

and other radically inclined politicians.

Soon after he reached the age of 21, the Prince became infatuated with Maria Fitzherbert. She was a commoner, six years his elder, twice widowed, and a Roman Catholic. Despite her complete unsuitability, the Prince was determined to marry her. This was in spite of the Act of Settlement 1701

Act of Settlement 1701

The Act of Settlement is an act of the Parliament of England that was passed in 1701 to settle the succession to the English throne on the Electress Sophia of Hanover and her Protestant heirs. The act was later extended to Scotland, as a result of the Treaty of Union , enacted in the Acts of Union...

, which barred the spouse of a Catholic from succeeding to the throne, and the Royal Marriages Act 1772

Royal Marriages Act 1772

The Royal Marriages Act 1772 is an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain which prescribes the conditions under which members of the British Royal Family may contract a valid marriage, in order to guard against marriages that could diminish the status of the Royal House...

, which prohibited his marriage without the consent of the King, which would never have been granted.

Nevertheless, the couple contracted a marriage on 15 December 1785 at her house in Park Street, Mayfair

Mayfair

Mayfair is an area of central London, within the City of Westminster.-History:Mayfair is named after the annual fortnight-long May Fair that took place on the site that is Shepherd Market today...

. Legally the union was void, as the King's consent was not granted (and never even requested). However, Mrs. Fitzherbert believed that she was the Prince's canonical

Canon law

Canon law is the body of laws & regulations made or adopted by ecclesiastical authority, for the government of the Christian organization and its members. It is the internal ecclesiastical law governing the Catholic Church , the Eastern and Oriental Orthodox churches, and the Anglican Communion of...

and true wife, holding the law of the Church to be superior to the law of the State. For political reasons, the union remained secret and Mrs. Fitzherbert promised not to reveal it.

The Prince was plunged into debt by his exorbitant lifestyle. His father refused to assist him, forcing him to quit Carlton House and live at Mrs. Fitzherbert's residence. In 1787, the Prince's political allies proposed to relieve his debts with a parliamentary grant. The Prince's relationship with Mrs. Fitzherbert was suspected, and revelation of the illegal marriage would have scandalised the nation and doomed any parliamentary proposal to aid him. Acting on the Prince's authority, the Whig leader Charles James Fox declared that the story was a calumny. Mrs. Fitzherbert was not pleased with the public denial of the marriage in such vehement terms and contemplated severing her ties to the Prince. He appeased her by asking another Whig, Richard Brinsley Sheridan

Richard Brinsley Sheridan

Richard Brinsley Butler Sheridan was an Irish-born playwright and poet and long-term owner of the London Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. For thirty-two years he was also a Whig Member of the British House of Commons for Stafford , Westminster and Ilchester...

, to restate Fox's forceful declaration in more careful words. Parliament, meanwhile, granted the Prince £161,000 (equal to £ today) to pay his debts and £60,000 (equal to £ today) for improvements to Carlton House.

Regency crisis of 1788

It is now conjectured that King George III suffered from the hereditary disease porphyriaPorphyria

Porphyrias are a group of inherited or acquired disorders of certain enzymes in the heme bio-synthetic pathway . They are broadly classified as acute porphyrias and cutaneous porphyrias, based on the site of the overproduction and accumulation of the porphyrins...

. In the summer of 1788 his mental health deteriorated, but he was nonetheless able to discharge some of his duties and to declare Parliament prorogued from 25 September to 20 November. During the prorogation George III became deranged, posing a threat to his own life, and when Parliament reconvened in November the King could not deliver the customary Speech from the Throne

Speech from the Throne

A speech from the throne is an event in certain monarchies in which the reigning sovereign reads a prepared speech to a complete session of parliament, outlining the government's agenda for the coming session...

during the State Opening of Parliament

State Opening of Parliament

In the United Kingdom, the State Opening of Parliament is an annual event that marks the commencement of a session of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is held in the House of Lords Chamber, usually in November or December or, in a general election year, when the new Parliament first assembles...

. Parliament found itself in an untenable position; according to long-established law it could not proceed to any business until the delivery of the King's Speech at a State Opening.

Although arguably barred from doing so, Parliament began debating a Regency. In the House of Commons, Charles James Fox declared his opinion that the Prince of Wales was automatically entitled to exercise sovereignty during the King's incapacity. A contrasting opinion was held by the Prime Minister, William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger was a British politician of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He became the youngest Prime Minister in 1783 at the age of 24 . He left office in 1801, but was Prime Minister again from 1804 until his death in 1806...

, who argued that, in the absence of a statute to the contrary, the right to choose a Regent belonged to Parliament alone. He even stated that, without parliamentary authority "the Prince of Wales had no more right...to assume the government, than any other individual subject of the country." Though disagreeing on the principle underlying a Regency, Pitt agreed with Fox that the Prince of Wales would be the most convenient choice for a Regent.

The Prince of Wales—though offended by Pitt's boldness—did not lend his full support to Fox's approach. The prince's brother, Prince Frederick, Duke of York, declared that the prince would not attempt to exercise any power without previously obtaining the consent of Parliament. Following the passage of preliminary resolutions Pitt outlined a formal plan for the Regency, suggesting that the powers of the Prince of Wales be greatly limited. Among other things, the Prince of Wales would not be able either to sell the King's property or to grant a peerage

Peerage

The Peerage is a legal system of largely hereditary titles in the United Kingdom, which constitute the ranks of British nobility and is part of the British honours system...

to anyone other than a child of the King. The Prince of Wales denounced Pitt's scheme, declaring it a "project for producing weakness, disorder, and insecurity in every branch of the administration of affairs." In the interests of the nation, both factions agreed to compromise.

A significant technical impediment to any Regency Bill involved the lack of a Speech from the Throne, which was necessary before Parliament could proceed to any debates or votes. The Speech was normally delivered by the King, but could also be delivered by royal representatives known as Lords Commissioners

Lords Commissioners

The Lords Commissioners are Privy Counsellors appointed by the Monarch of the United Kingdom to exercise, on his or her behalf, certain functions relating to Parliament which would otherwise require the monarch's attendance at the Palace of Westminster...

; but no document could empower the Lords Commissioners to act unless the Great Seal of the Realm

Great Seal of the Realm

The Great Seal of the Realm or Great Seal of the United Kingdom is a seal that is used to symbolise the Sovereign's approval of important state documents...

was affixed to it. The Seal could not be legally affixed without the prior authorisation of the Sovereign. Pitt and his fellow ministers ignored the last requirement and instructed the Lord Chancellor

Lord Chancellor

The Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, or Lord Chancellor, is a senior and important functionary in the government of the United Kingdom. He is the second highest ranking of the Great Officers of State, ranking only after the Lord High Steward. The Lord Chancellor is appointed by the Sovereign...

to affix the Great Seal without the King's consent, as the act of affixing the Great Seal in itself gave legal force to the Bill. This legal fiction

Legal fiction

A legal fiction is a fact assumed or created by courts which is then used in order to apply a legal rule which was not necessarily designed to be used in that way...

was denounced by Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke PC was an Irish statesman, author, orator, political theorist and philosopher who, after moving to England, served for many years in the House of Commons of Great Britain as a member of the Whig party....

as a "glaring falsehood", as a "palpable absurdity", and even as a "forgery, fraud". The Prince of Wales's brother, the Duke of York, described the plan as "unconstitutional and illegal." Nevertheless, others in Parliament felt that such a scheme was necessary to preserve an effective government. Consequently on 3 February 1789, more than two months after it had convened, Parliament was formally opened by an "illegal" group of Lords Commissioners. The Regency Bill was introduced, but before it could be passed the King recovered. The King declared retroactively that the instrument authorising the Lords Commissioners to act was valid.

Marriage and mistresses

The Prince of Wales's debts continued to climb, and his father refused to aid him unless he married his cousin Princess Caroline of BrunswickCaroline of Brunswick

Caroline of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel was the Queen consort of King George IV of the United Kingdom from 29 January 1820 until her death...

. In 1795, the Prince of Wales acquiesced, and they were married on 8 April 1795 at the Chapel Royal

Chapel Royal

A Chapel Royal is a body of priests and singers who serve the spiritual needs of their sovereign wherever they are called upon to do so.-Austria:...

, St James's Palace. The marriage, however, was disastrous; each party was unsuited to the other. The two were formally separated after the birth of their only child, Princess Charlotte, in 1796, and remained separated thereafter. The Prince of Wales remained attached to Mrs. Fitzherbert for the rest of his life, despite several periods of estrangement.

George's mistresses included Mary Robinson

Mary Robinson (poet)

Mary Robinson was an English poet and novelist. During her lifetime she is known as 'the English Sappho'...

, an actress who was bought off with a generous pension when she threatened to sell his letters to the newspapers; Grace Elliott

Grace Elliott

Grace Dalrymple Elliott was a Scottish socialite and courtesan who was resident in Paris at the time of the French Revolution and an eyewitness to events. She was once mistress of the Duke of Orléans, who was cousin to King Louis XVI....

, the divorced wife of a physician; and Frances Villiers, Countess of Jersey

Frances Villiers, Countess of Jersey

Frances Villiers, Countess of Jersey was one of the more notorious of the many mistresses of King George IV when he was Prince of Wales, "a scintillating society woman, a heady mix of charm, beauty, and sarcasm".-Early life:She was born Frances Twysden, second and posthumous daughter of the Rev...

, who dominated his life for some years. In later life, his mistresses were the Marchioness of Hertford and the Marchioness Conyngham

Elizabeth Conyngham, Marchioness Conyngham

Elizabeth Conyngham , Marchioness Conyngham , was an English courtier and noblewoman, and the last mistress of George IV of the United Kingdom.- Early life :...

, who were both married to aristocrats.

George may have fathered several illegitimate children. James Ord (born 1786)—who moved to the United States and became a Jesuit priest—was reportedly his son by Mrs. Fitzherbert. The King, late in life, told a friend that he had a son who was a naval officer in the West Indies, whose identity has been tentatively established as Capt. Henry A. F. Hervey (1786–1824), reportedly George's child by the songwriter Lady Anne Lindsay (later Barnard)

Lady Anne Barnard

Lady Anne Barnard , née Anne Lindsay, eldest daughter of James Lindsay, 5th Earl of Balcarres was born at Balcarres House, Fife, Scotland. She was author of the ballad Auld Robin Gray and an accomplished travel writer, artist and socialite of the period...

, a daughter of the 5th Earl of Balcarres

James Lindsay, 5th Earl of Balcarres

James Lindsay, 5th Earl of Balcarres was a Scottish peer, the son of Colin, 3rd Earl of Balcarres and Lady Margaret Campbell, daughter of the Earl of Loudoun...

. Other reported offspring include Major G. S. Crole, the son of theatre manager's daughter Eliza Crole or Fox; William Hampshire, the son of publican's daughter Sarah Brown; and Charles "Beau" Candy, the son of a Frenchwoman with that surname. Anthony Camp, Director of Research at the Society of Genealogists

Society of Genealogists

The Society of Genealogists is a UK-based educational charity, founded in 1911 to "promote, encourage and foster the study, science and knowledge of genealogy". The Society's Library is the largest specialist genealogical library outside North America. Membership is open to any adult who agrees to...

, has dismissed the claims that George IV was the father of Ord, Hervey, Hampshire and Candy as fictitious.

The problem of the Prince of Wales's debts, which amounted to the extraordinary sum of £630,000 (equal to £ today) in 1795, was solved (at least temporarily) by Parliament. Being unwilling to make an outright grant to relieve these debts, it provided him an additional sum of £65,000 (equal to £ today) per annum. In 1803, a further £60,000 (equal to £ today) was added, and the Prince of Wales's debts of 1795 were finally cleared in 1806, although the debts he had incurred since 1795 remained.

In 1804 a dispute arose over the custody of Princess Charlotte, which led to her being placed in the care of the King, George III. It also led to a Parliamentary Commission of Enquiry into Princess Caroline's conduct after the Prince of Wales accused her of having an illegitimate son. The investigation cleared Caroline of the charge but still revealed her behaviour to be extraordinarily indiscreet.

Regency

In late 1810, George III was once again overcome by his malady following the death of his youngest daughter, Princess AmeliaPrincess Amelia of the United Kingdom

Princess Amelia of the United Kingdom was a member of the British Royal Family as the youngest daughter of King George III of the United Kingdom and his queen consort Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz.-Early life:...

. Parliament agreed to follow the precedent of 1788; without the King's consent, the Lord Chancellor affixed the Great Seal of the Realm to letters patent

Letters patent

Letters patent are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch or president, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, title, or status to a person or corporation...

naming Lords Commissioners. The Lords Commissioners, in the name of the King, signified the granting of the Royal Assent

Royal Assent

The granting of royal assent refers to the method by which any constitutional monarch formally approves and promulgates an act of his or her nation's parliament, thus making it a law...

to a bill that became the Regency Act of 1811. Parliament restricted some of the powers of the Prince Regent (as the Prince of Wales became known). The constraints expired one year after the passage of the Act. The Prince of Wales became Prince Regent on 5 February 1811.

The Regent let his ministers take full charge of government affairs, playing a far lesser role than his father. The principle that the crown accepts as prime minister the person who controls a majority in the House of Commons, whether the king personally favours him or not, became established. His governments, with little help from the Regent, presided over victory in the Napoleonic Wars, negotiated the peace settlement, and attempted to deal with the social and economic malaise that followed. One of the most important political conflicts facing the country concerned Catholic emancipation

Catholic Emancipation

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in Great Britain and Ireland in the late 18th century and early 19th century which involved reducing and removing many of the restrictions on Roman Catholics which had been introduced by the Act of Uniformity, the Test Acts and the penal laws...

, the movement to relieve Roman Catholics of various political disabilities. The Tories, led by the Prime Minister, Spencer Perceval

Spencer Perceval

Spencer Perceval, KC was a British statesman and First Lord of the Treasury, making him de facto Prime Minister. He is the only British Prime Minister to have been assassinated...

, were opposed to Catholic emancipation, while the Whigs supported it. At the beginning of the Regency, the Prince of Wales was expected to support the Whig leader, William Wyndham Grenville, 1st Baron Grenville

William Wyndham Grenville, 1st Baron Grenville

William Wyndham Grenville, 1st Baron Grenville PC, PC was a British Whig statesman. He served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1806 to 1807 as head of the Ministry of All the Talents.-Background :...

. He did not, however, immediately put Lord Grenville and the Whigs in office. Influenced by his mother, he claimed that a sudden dismissal of the Tory government would exact too great a toll on the health of the King (a steadfast supporter of the Tories), thereby eliminating any chance of a recovery.

On 10 May 1812, Spencer Perceval was assassinated by John Bellingham

John Bellingham

John Bellingham was the assassin of British Prime Minister Spencer Perceval. This murder was the only successful attempt on the life of a British Prime Minister...

. The Prince Regent was prepared to reappoint all the members of the Perceval ministry under a new leader. The House of Commons formally declared its desire for a "strong and efficient administration", so the Prince Regent then offered leadership of the government to Richard Wellesley, 1st Marquess Wellesley

Richard Wellesley, 1st Marquess Wellesley

Richard Colley Wesley, later Wellesley, 1st Marquess Wellesley, KG, PC, PC , styled Viscount Wellesley from birth until 1781, was an Anglo-Irish politician and colonial administrator....

, and afterwards to Francis Rawdon-Hastings, 2nd Earl of Moira

Francis Rawdon-Hastings, 1st Marquess of Hastings

Francis Edward Rawdon-Hastings, 1st Marquess of Hastings KG PC , styled The Honourable Francis Rawdon from birth until 1762 and as The Lord Rawdon between 1762 and 1783 and known as The Earl of Moira between 1793 and 1816, was an Irish-British politician and military officer who served as...

. He doomed the attempts of both to failure, however, by forcing each to construct a bipartisan ministry at a time when neither party wished to share power with the other. Possibly using the failure of the two peers as a pretext, the Prince Regent immediately reappointed the Perceval administration, with Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool, as Prime Minister.

The Tories, unlike Whigs such as Earl Grey

Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey

Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey, KG, PC , known as Viscount Howick between 1806 and 1807, was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 22 November 1830 to 16 July 1834. A member of the Whig Party, he backed significant reform of the British government and was among the...

, sought to continue the vigorous prosecution of the war in Continental Europe against the powerful and aggressive Emperor of the French, Napoleon I

Napoleon I of France

Napoleon Bonaparte was a French military and political leader during the latter stages of the French Revolution.As Napoleon I, he was Emperor of the French from 1804 to 1815...

. An anti-French alliance, which included Russia, Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

, Austria, Britain and several smaller countries, defeated Napoleon in 1814. In the subsequent Congress of Vienna

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna was a conference of ambassadors of European states chaired by Klemens Wenzel von Metternich, and held in Vienna from September, 1814 to June, 1815. The objective of the Congress was to settle the many issues arising from the French Revolutionary Wars, the Napoleonic Wars,...

, it was decided that the Electorate of Hanover

Electorate of Hanover

The Electorate of Brunswick-Lüneburg was the ninth Electorate of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation...

, a state that had shared a monarch with Britain since 1714, would be raised to a Kingdom, known as the Kingdom of Hanover

Kingdom of Hanover

The Kingdom of Hanover was established in October 1814 by the Congress of Vienna, with the restoration of George III to his Hanoverian territories after the Napoleonic era. It succeeded the former Electorate of Brunswick-Lüneburg , and joined with 38 other sovereign states in the German...

. Napoleon returned from exile in 1815, but was defeated at the Battle of Waterloo

Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815 near Waterloo in present-day Belgium, then part of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands...

by Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

Field Marshal Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, KG, GCB, GCH, PC, FRS , was an Irish-born British soldier and statesman, and one of the leading military and political figures of the 19th century...

, brother of Marquess Wellesley. That same year the British-American War of 1812

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was a military conflict fought between the forces of the United States of America and those of the British Empire. The Americans declared war in 1812 for several reasons, including trade restrictions because of Britain's ongoing war with France, impressment of American merchant...

came to an end, with neither side victorious.

During this period George took an active interest in matters of style and taste, and his associates such as the dandy Beau Brummell

Beau Brummell

Beau Brummell, born as George Bryan Brummell , was the arbiter of men's fashion in Regency England and a friend of the Prince Regent, the future King George IV...

and the architect John Nash

John Nash (architect)

John Nash was a British architect responsible for much of the layout of Regency London.-Biography:Born in Lambeth, London, the son of a Welsh millwright, Nash trained with the architect Sir Robert Taylor. He established his own practice in 1777, but his career was initially unsuccessful and...

created the Regency style. In London Nash designed the Regency terraces of Regent's Park

Regent's Park

Regent's Park is one of the Royal Parks of London. It is in the north-western part of central London, partly in the City of Westminster and partly in the London Borough of Camden...

and Regent Street

Regent Street

Regent Street is one of the major shopping streets in London's West End, well known to tourists and Londoners alike, and famous for its Christmas illuminations...

. George took up the new idea of the seaside spa and had the Brighton Pavilion developed as a fantastical seaside palace, adapted by Nash in the "Indian Gothic" style inspired loosely by the Taj Mahal

Taj Mahal

The Taj Mahal is a white Marble mausoleum located in Agra, India. It was built by Mughal emperor Shah Jahan in memory of his third wife, Mumtaz Mahal...

, with extravagant "Indian" and "Chinese" interiors.

Reign

Laudanum

Laudanum , also known as Tincture of Opium, is an alcoholic herbal preparation containing approximately 10% powdered opium by weight ....

.

George IV's relationship with his wife Caroline

Caroline of Brunswick

Caroline of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel was the Queen consort of King George IV of the United Kingdom from 29 January 1820 until her death...

had deteriorated by the time of his accession. They had lived separately since 1796, and both were having affairs. In 1814, Caroline left the United Kingdom for continental Europe, but she chose to return for her husband's coronation, and to publicly assert her rights as Queen Consort. However, George IV refused to recognise Caroline as Queen, and commanded British ambassadors to ensure that monarchs in foreign courts did the same. By royal command, Caroline's name was omitted from the Book of Common Prayer

Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer is the short title of a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion, as well as by the Continuing Anglican, "Anglican realignment" and other Anglican churches. The original book, published in 1549 , in the reign of Edward VI, was a product of the English...

, the liturgy

Liturgy

Liturgy is either the customary public worship done by a specific religious group, according to its particular traditions or a more precise term that distinguishes between those religious groups who believe their ritual requires the "people" to do the "work" of responding to the priest, and those...

of the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

. The King sought a divorce, but his advisors suggested that any divorce proceedings might involve the publication of details relating to the King's own adulterous relationships. Therefore, he requested and ensured the introduction of the Pains and Penalties Bill 1820

Pains and Penalties Bill 1820

The Pains and Penalties Bill 1820 was a bill introduced to the British Parliament in 1820, at the request of King George IV, which aimed to dissolve his marriage to Caroline of Brunswick, and deprive her of the title of Queen of the United Kingdom....

, under which Parliament could have imposed legal penalties without a trial in a court of law. The bill would have annulled the marriage and stripped Caroline of the title of Queen. The bill proved extremely unpopular with the public, and was withdrawn from Parliament. George IV decided, nonetheless, to exclude his wife from his coronation at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey

The Collegiate Church of St Peter at Westminster, popularly known as Westminster Abbey, is a large, mainly Gothic church, in the City of Westminster, London, United Kingdom, located just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is the traditional place of coronation and burial site for English,...

, on 19 July 1821. Caroline fell ill that day and died on 7 August; during her final illness she often stated that she thought she had been poisoned.

Richard II of England

Richard II was King of England, a member of the House of Plantagenet and the last of its main-line kings. He ruled from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. Richard was a son of Edward, the Black Prince, and was born during the reign of his grandfather, Edward III...

. The following year he visited Edinburgh

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland, the second largest city in Scotland, and the eighth most populous in the United Kingdom. The City of Edinburgh Council governs one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas. The council area includes urban Edinburgh and a rural area...

for "one and twenty daft days." His visit to Scotland

Visit of King George IV to Scotland

The 1822 visit of King George IV to Scotland was the first visit of a reigning monarch to Scotland since 1650. Government ministers had pressed the King to bring forward a proposed visit to Scotland, to divert him from diplomatic intrigue at the Congress of Verona.The visit increased his popularity...

, organised by Sir Walter Scott

Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet was a Scottish historical novelist, playwright, and poet, popular throughout much of the world during his time....

, was the first by a reigning British monarch since the mid-17th century.

Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a medieval castle and royal residence in Windsor in the English county of Berkshire, notable for its long association with the British royal family and its architecture. The original castle was built after the Norman invasion by William the Conqueror. Since the time of Henry I it...

, but he continued to intervene in politics. At first it was believed that he would support Catholic Emancipation

Catholic Emancipation

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in Great Britain and Ireland in the late 18th century and early 19th century which involved reducing and removing many of the restrictions on Roman Catholics which had been introduced by the Act of Uniformity, the Test Acts and the penal laws...

, as he had proposed a Catholic Emancipation Bill for Ireland in 1797, but his anti-Catholic views became clear in 1813 when he privately canvassed against the ultimately defeated Catholic Relief Bill of 1813. By 1824 he was denouncing Catholic emancipation in public. Having taken the coronation oath on his accession, George now argued that he had sworn to uphold the Protestant faith, and could not support any pro-Catholic measures. The influence of the Crown was so great, and the will of the Tories under Prime Minister Lord Liverpool

Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool

Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool KG PC was a British politician and the longest-serving Prime Minister of the United Kingdom since the Union with Ireland in 1801. He was 42 years old when he became premier in 1812 which made him younger than all of his successors to date...

so strong, that Catholic emancipation seemed hopeless. In 1827, however, Lord Liverpool retired, to be replaced by the pro-emancipation Tory George Canning

George Canning

George Canning PC, FRS was a British statesman and politician who served as Foreign Secretary and briefly Prime Minister.-Early life: 1770–1793:...

. When Canning entered office, the King, hitherto content with privately instructing his ministers on the Catholic Question, thought it fit to make a public declaration to the effect that his sentiments on the question were those of his revered father, George III.

Canning's views on the Catholic Question were not well received by the most conservative Tories, including the Duke of Wellington. As a result the ministry was forced to include Whigs. Canning died later in that year, leaving Frederick John Robinson, 1st Viscount Goderich

Frederick John Robinson, 1st Viscount Goderich

Frederick John Robinson, 1st Earl of Ripon PC , styled The Honourable F. J. Robinson until 1827 and known as The Viscount Goderich between 1827 and 1833, the name by which he is best known to history, was a British statesman...

to lead the tenuous Tory-Whig coalition. Lord Goderich left office in 1828, to be succeeded by the Duke of Wellington, who had by that time accepted that the denial of some measure of relief to Roman Catholics was politically untenable. With great difficulty Wellington obtained the King's consent to the introduction of a Catholic Relief Bill on 29 January 1829. Under pressure from his fanatically anti-Catholic brother, the Duke of Cumberland

Ernest Augustus I of Hanover

Ernest Augustus I was King of Hanover from 20 June 1837 until his death. He was the fifth son and eighth child of George III, who reigned in both the United Kingdom and Hanover...

, the King withdrew his approval and in protest the Cabinet resigned en masse on 4 March. The next day the King, now under intense political pressure, reluctantly agreed to the Bill and the ministry remained in power. Royal Assent was finally granted to the Catholic Relief Act

Catholic Relief Act 1829

The Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829 was passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom on 24 March 1829, and received Royal Assent on 13 April. It was the culmination of the process of Catholic Emancipation throughout the nation...

on 13 April.

George IV's heavy drinking and indulgent lifestyle had taken their toll of his health by the late 1820s. His taste for huge banquets and copious amounts of alcohol caused him to become obese, making him the target of ridicule on the rare occasions that he did appear in public. By 1797 his weight had reached 17 stone 7 pounds (111 kg or 245 lb), and by 1824 his corset was made for a waist of 50 inches (127 cm). He suffered from gout

Gout

Gout is a medical condition usually characterized by recurrent attacks of acute inflammatory arthritis—a red, tender, hot, swollen joint. The metatarsal-phalangeal joint at the base of the big toe is the most commonly affected . However, it may also present as tophi, kidney stones, or urate...

, arteriosclerosis

Arteriosclerosis

Arteriosclerosis refers to a stiffening of arteries.Arteriosclerosis is a general term describing any hardening of medium or large arteries It should not be confused with "arteriolosclerosis" or "atherosclerosis".Also known by the name "myoconditis" which is...

, dropsy and possible porphyria

Porphyria

Porphyrias are a group of inherited or acquired disorders of certain enzymes in the heme bio-synthetic pathway . They are broadly classified as acute porphyrias and cutaneous porphyrias, based on the site of the overproduction and accumulation of the porphyrins...

; he would spend whole days in bed and suffered spasms of breathlessness that would leave him half-asphyxiated. Some accounts claim that he showed signs of mental instability towards the end of his life, although less extreme than his father; for example, he sometimes claimed that he had been at the Battle of Waterloo

Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815 near Waterloo in present-day Belgium, then part of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands...

, which may have been a sign of dementia

Dementia

Dementia is a serious loss of cognitive ability in a previously unimpaired person, beyond what might be expected from normal aging...

or just a joke to annoy the Duke of Wellington

Duke of Wellington

The Dukedom of Wellington, derived from Wellington in Somerset, is a hereditary title in the senior rank of the Peerage of the United Kingdom. The first holder of the title was Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington , the noted Irish-born career British Army officer and statesman, and...

. He died at about half-past three in the morning of 26 June 1830 at Windsor Castle; he called out "Good God, what is this?" clasped his page's hand and said "my boy, this is death." He was buried in St George's Chapel, Windsor on 15 July.

His only legitimate child, Princess Charlotte Augusta of Wales

Princess Charlotte Augusta of Wales

Princess Charlotte of Wales was the only child of George, Prince of Wales and Caroline of Brunswick...

, had died from post-partum complications in 1817, after delivering a still-born son. The second son of George III, Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany

Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany

The Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany was a member of the Hanoverian and British Royal Family, the second eldest child, and second son, of King George III...

, had died in 1827. He was therefore succeeded by another brother, the third son of George III, Prince William, Duke of Clarence

William IV of the United Kingdom

William IV was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and of Hanover from 26 June 1830 until his death...

, who reigned as William IV.

Legacy

On George's death The Times

The Times

The Times is a British daily national newspaper, first published in London in 1785 under the title The Daily Universal Register . The Times and its sister paper The Sunday Times are published by Times Newspapers Limited, a subsidiary since 1981 of News International...

captured elite opinion succinctly: "There never was an individual less regretted by his fellow-creatures than this deceased king. What eye has wept for him? What heart has heaved one throb of unmercenary sorrow? ... If he ever had a friend – a devoted friend in any rank of life – we protest that the name of him or her never reached us."

During the political crisis caused by Catholic emancipation, the Duke of Wellington said that George was "the worst man he ever fell in with his whole life, the most selfish, the most false, the most ill-natured, the most entirely without one redeeming quality", but his eulogy delivered in the House of Lords

House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster....

called George "the most accomplished man of his age" and praised his knowledge and talent. Wellington's true feelings probably lie somewhere between these two extremes; as he said later, George was "a magnificent patron of the arts ... the most extraordinary compound of talent, wit, buffoonery, obstinacy, and good feeling—in short a medley of the most opposite qualities, with a great preponderence of good—that I ever saw in any character in my life."