Richard Owen

Encyclopedia

Sir Richard Owen, FRS

KCB

(20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English

biologist

, comparative anatomist

and palaeontologist

.

Owen is probably best remembered today for coining the word Dinosauria (meaning "Terrible Reptile

" or "Fearfully Great Reptile

") and for his outspoken opposition to Charles Darwin

's theory of evolution

by natural selection

. He agreed with Darwin that evolution occurred, but thought it was more complex than outlined in Darwin's Origin. Owen's approach to evolution can be seen as having anticipated the issues that have gained greater attention with the recent emergence of evolutionary developmental biology

. He was the driving force behind the establishment, in 1881, of the British Museum (Natural History) in London

. Bill Bryson

argues that, "by making the Natural History Museum an institution for everyone, Owen transformed our expectations of what museums are for".

in 1804, one of six children of a West Indian Merchant named Richard Owen (1754-1809). His mother, Catherine Parrin, was descended from Huguenot

s and he was educated at Lancaster Royal Grammar School

. In 1820, he was apprenticed to a local surgeon

and apothecary

and, in 1824, he proceeded as a medical student to the University of Edinburgh

. He left the university in the following year and completed his medical course in St Bartholomew's Hospital

, London

, where he came under the influence of the eminent surgeon, John Abernethy

.

In July 1835 Owen married Caroline Amelia Clift in St Pancras

by whom he had one son, William Owen. Richard sadly outlived both his wife and only son and on his death in 1892 he was survived by his three grandchildren and daughter-in-law Emily Owen, whom he left much of his £33,000 fortune to.

He then contemplated the usual professional career but his bent was evidently in the direction of anatomical research. He was induced by Abernethy to accept the position of assistant to William Clift

He then contemplated the usual professional career but his bent was evidently in the direction of anatomical research. He was induced by Abernethy to accept the position of assistant to William Clift

, conservator of the museum of the Royal College of Surgeons

. This congenial occupation soon led him to abandon his intention of medical practice and his life henceforth was devoted to purely scientific labours. He prepared an important series of catalogues of the Hunterian Collection

, in the Royal College of Surgeons and, in the course of this work, he acquired the unrivalled knowledge of comparative anatomy, which enabled him to enrich all departments of the science and especially facilitated his researches on the remains of extinct animals.

In 1836, Owen was appointed Hunterian professor, in the Royal College of Surgeons and, in 1849, he succeeded Clift as conservator. He held the latter office until 1856, when he became superintendent of the natural history department of the British Museum

In 1836, Owen was appointed Hunterian professor, in the Royal College of Surgeons and, in 1849, he succeeded Clift as conservator. He held the latter office until 1856, when he became superintendent of the natural history department of the British Museum

. He then devoted much of his energies to a great scheme for a National Museum of Natural History, which eventually resulted in the removal of the natural history collections of the British Museum to a new building at South Kensington

: the British Museum (Natural History) (now the Natural History Museum

). He retained office until the completion of this work, in December, 1883, when he was made a knight of the Order of the Bath

. He lived quietly in retirement at Sheen Lodge, Richmond Park

, until his death in 1892.

His career was tainted by accusations that he failed to give credit to the work of others and even tried to appropriate it in his own name. This came to a head in 1846, when he was awarded the Royal Medal

for a paper he had written on belemnites. Owen had failed to acknowledge that the belemnite had been discovered by Chaning Pearce, an amateur biologist, four years earlier. As a result of the ensuing scandal, he was voted off the councils of the Zoological Society

and the Royal Society

.

Owen always tended to support orthodox men of science and the status quo. The royal family presented him with the cottage in Richmond Park and Robert Peel

put him on the Civil List

. In 1843, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

.

's gardens and, when the Zoo began to publish scientific proceedings, in 1831, he was the most voluminous contributor of anatomical papers. His first notable publication, however, was his Memoir on the Pearly Nautilus

(London, 1832), which was soon recognized as a classic. Henceforth, he continued to make important contributions to every department of comparative anatomy and zoology

, for a period of over fifty years. In the sponges, Owen was the first to describe the now well-known Venus' Flower Basket

or Euplectella

(1841, 1857). Among Entozoa, his most noteworthy discovery was that of Trichina spiralis (1835), the parasite infesting the muscles of man in the disease now termed trichinosis

(see also, however, Sir James Paget

). Of Brachiopod

a he made very special studies, which much advanced knowledge and settled the classification, which has long been adopted. Among Mollusca, he not only described the pearly nautilus, but also Spirula (1850) and other Cephalopod

a, both living and extinct and it was he who proposed the universally-accepted subdivision of this class into the two orders of Dibranchiata and Tetrabranchiata (1832). The problematical Arthropod

Limulus

was also the subject of a special memoir by him, in 1873.

were still more numerous and extensive than those of the invertebrate

animals. His Comparative Anatomy and Physiology of Vertebrates (3 vols. London 1866–1868) was indeed the result of more personal research than any similar work since Georges Cuvier

's Leçons d'anatomie comparée. He not only studied existing forms but also devoted great attention to the remains of extinct groups, and followed Cuvier, the pioneer of vertebrate paleontology

. Early in his career, he made exhaustive studies of teeth of existing and extinct animals and published his profusely illustrated work on Odontography (1840–1845). He discovered and described the remarkably complex structure of the teeth of the extinct animals which he named Labyrinthodonts

. Among his writings on fish

, his memoir on the African lungfish, which he named Protopterus

, laid the foundations for the recognition of the Dipnoi

by Johannes Müller

. He also later pointed out the serial connection between the teleostean and ganoid fishes, grouping them in one sub-class, the Teleostomi

.

Most of his work on reptile

s related to the skeleton

s of extinct forms and his chief memoirs, on British specimens, were reprinted in a connected series in his History of British Fossil Reptiles (4 vols. London 1849–1884). He published the first important general account of the great group of Mesozoic

land-reptiles, and he coined the name Dinosauria from Greek

δεινός (deinos) "terrible, powerful, wondrous" + σαῦρος (sauros) "lizard". Owen used 3 genera to define the dinosaurs: the carnivorous Megalosaurus

, the herviborous Iguanodon

and armoured Hylaeosaurus

. He also first recognized the curious early Mesozoic land-reptiles, with affinities both to amphibians and mammal

s, which he termed Anomodontia (the mammal-like reptiles, Therapsida

). Most of these were obtained from South Africa

, beginning in 1845 (Dicynodon

) and eventually furnished materials for his Catalogue of the Fossil Reptilia of South Africa, issued by the British Museum

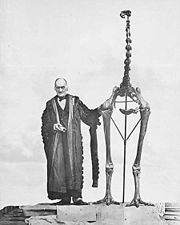

, in 1876. Among his writings on bird

s, his classical memoir on the kiwi

(1840–1846), a long series of papers on the extinct dinornithidae

of New Zealand

, other memoirs on aptornis

, the takahe

, the dodo

and the Great Auk

, may be especially mentioned. His monograph on Archaeopteryx

(1863), the long-tailed, toothed bird from the Bavaria

n lithographic stone, is also an epoch-making work.

With Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins

, Owen helped create the first life-size sculptures depicting dinosaurs as he thought they may have appeared. Some models were initially created for the Great Exhibition of 1851, but 33 were eventually produced when the Crystal Palace

was relocated to Sydenham

, in South London. Owen famously hosted a dinner for 21 prominent men of science inside the hollow concrete Iguanodon

on New Year's Eve 1853. However, in 1849, a few years before his death in 1852, Gideon Mantell

had realised that Iguanodon, of which he was the discoverer, was not a heavy, pachyderm

-like animal, as Owen was putting forward, but had slender forelimbs; his death left him unable to participate in the creation of the Crystal Palace dinosaur sculptures

, and so Owen's vision of dinosaurs became that seen by the public. He had nearly two dozen lifesize sculpture

s of various prehistoric animals built out of concrete

sculpted over a steel

and brick

framework; two Iguanodon, one standing and one resting on its belly, were included.

.jpg) Owen was granted right of first refusal

Owen was granted right of first refusal

on any freshly dead animal at the London Zoo. His wife once arrived home to find the carcass of a newly deceased rhinoceros in her front hallway.

With regard to living mammals, the more striking of Owen's contributions relate to the monotreme

s, marsupial

s and the anthropoid ape

s. He was also the first to recognize and name the two natural groups of typical Ungulate, the odd-toed (Perissodactyla

) and the even-toed (Artiodactyla

), while describing some fossil remains, in 1848. Most of his writings on mammals, however, deal with extinct forms, to which his attention seems to have been first directed by the remarkable fossils collected by Charles Darwin

, in South America

. Toxodon

, from the pampas, was then described and gave the earliest clear evidence of an extinct generalized hoof animal, a pachyderm with affinities to the Rodent

ia, Edentata and herbivorous Cetacea

. Owen's interest in South American extinct mammals then led to the recognition of the giant armadillo

, which he named Glyptodon

(1839) and to classic memoirs on the giant ground-sloth

s, Mylodon

(1842) and Megatherium

(1860), besides other important contributions.

At the same time, Sir Thomas Mitchell's discovery of fossil bones, in New South Wales

, provided material for the first of Owen's long series of papers on the extinct mammals of Australia

, which were eventually reprinted in book-form in 1877. He discovered Diprotodon and Thylacoleo, besides extinct kangaroo

s and wombat

s, of gigantic size. While occupied with so much material from abroad, Owen was also busily collecting facts for an exhaustive work on similar fossils from the British Isles and, in 1844-1846, he published his History of British Fossil Mammals and Birds, which was followed by many later memoirs, notably his Monograph of the Fossil Mammalia of the Mesozoic Formations (Palaeont. Soc., 1871). One of his latest publications was a little work entitled Antiquity of Man as deduced from the Discovery of a Human Skeleton during Excavations of the Docks at Tilbury (London, 1884).

Following the voyage of the Beagle

Following the voyage of the Beagle

, Darwin

had at his disposal a considerable collection of specimens and, on 29 October 1836, he was introduced by Charles Lyell

to Owen, who agreed to work on fossil bones collected in South America

. Owen's subsequent revelations, that the extinct giant creatures were rodents and sloths, showed that they were related to current species in the same locality, rather than being relatives of similarly sized creatures in Africa

, as Darwin had originally thought. This was one of the many influences which led Darwin to later formulate his own ideas on the concept of natural selection

.

At this time, Owen talked of his theories, influenced by Johannes Peter Müller

, that living matter had an "organising energy", a life-force that directed the growth of tissues and also determined the lifespan of the individual and of the species. Darwin was reticent about his own thoughts, understandably, when, on 19 December 1838, as secretary of the Geological Society of London

, he saw Owen and his allies ridicule the Lamarckian 'heresy' of Darwin's old tutor, Robert Edmund Grant. In 1841, when the recently married Darwin was ill, Owen was one of the few scientific friends to visit; however, Owen's opposition to any hint of transmutation

made Darwin keep quiet about his hypothesis.

Sometime during the 1840s Owen came to the conclusion that species arise as the result of some sort of evolutionary process. He believed that there was a total of six possible mechanisms: parthenogenesis, prolonged development, premature birth, congenital malformations, Lamarckian atrophy, Lamarckian hypertrophy and transmutation, of which he thought transmutation was the least likely. The historian of science Evelleen Richards has argued that Owen was likely sympathetic to developmental theories of evolution, but backed away from publicly proclaiming them after the critical reaction that had greeted the anonymously-published evolutionary book Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation

in 1844 (it was revealed only decades later that the book had been authored by publisher Robert Chambers

). Owen had been criticized for his own evolutionary remarks in his Nature of the Limbs in 1849. At the end of On the Nature of Limbs Owen had suggested that humans ultimately evolved from fish as the result of natural laws, which resulted in him getting criticized in the Manchester Spectator for denying species like humans were created by God.

During the development of Darwin's theory

, his investigation of barnacles showed, in 1849, how their segmentation related to other crustaceans, showing how they had diverged from their relatives. To both Darwin and Owen such "homologies" in comparative anatomy was evidence of descent. Owen demonstrated fossil evidence of an evolutionary sequence of horses, as supporting his idea of development from archetypes in "ordained continuous becoming" and, in 1854, gave a British Association

talk on the impossibility of bestial apes, such as the recently discovered gorilla

, standing erect and being transmuted into men, but Owen did not rule out the possibility that humans evolved from other extinct animals by evolutionary mechanisms other than transmutation. Working class militants were trumpeting man's monkey origins, and in 1861 Karl Marx

wrote: "Darwin's work is most important and suits my purpose in that it provides a basis in natural science for the historical class struggle." To crush these ideas, Owen, as President-elect of the Royal Association, announced his authoritative anatomical studies of primate brains, claiming that the human brain had structures that apes brains did not, and that therefore humans were a separate sub-class. Owen's main argument was that humans have much larger brains for their body size than other mammals including the great apes. Darwin wrote that "I cannot swallow Man [being that] distinct from a Chimpanzee". The combative Thomas Henry Huxley used his March 1858 Royal Institution

lecture to deny Owen's claim and affirmed that structurally, gorillas are as close to humans as they are to baboon

s. He believed that the "mental & moral faculties are essentially... the same kind in animals & ourselves". This was a clear denial of Owen's claim for human uniqueness, given at the same venue.

On the publication of Darwin's theory

On the publication of Darwin's theory

, in On The Origin of Species, he sent a complimentary copy to Owen, saying "it will seem 'an abomination'". Owen was the first to respond, courteously claiming that he had long believed that "existing influences" were responsible for the "ordained" birth of species. Darwin now had long talks with him and Owen said that the book offered the best explanation "ever published of the manner of formation of species", although he still had the gravest doubts that transmutation would bestialize man. It appears that Darwin had assured Owen that he was looking at everything as resulting from designed laws, which Owen interpreted as showing a shared belief in "Creative Power".

As head of the Natural History Collections at the British Museum

, Owen received numerous inquiries and complaints about the Origin. His own views remained unknown: when emphasising to a Parliamentary committee the need for a new Natural History museum, he pointed out that "The whole intellectual world this year has been excited by a book on the origin of species; and what is the consequence? Visitors come to the British Museum, and they say, "Let us see all these varieties of pigeons: where is the tumbler, where is the pouter?" and I am obliged with shame to say, I can show you none of them".... As to showing you the varieties of those species, or of any of those phenomena that would aid one in getting at that mystery of mysteries, the origin of species, our space does not permit; but surely there ought to be a space somewhere, and, if not in the British Museum, where is it to be obtained?"

However, Huxley's attacks were making their mark. In April 1860 the Edinburgh Review included Owen's anonymous review of the Origin. In it Owen showed his anger at what he saw as Darwin's caricature of the creationist position, and his ignoring Owen's "axiom of the continuous operation of the ordained becoming of living things". As well as attacking Darwin's "disciples", Hooker and Huxley, for their "short-sighted adherence", he thought that the book symbolised the sort of "abuse of science... to which a neighbouring nation, some seventy years since, owed its temporary degradation" in a reference to the French Revolution

. Darwin thought it "Spiteful, extremely malignant, clever, and... damaging" and later commented that "The Londoners say he is mad with envy because my book is so talked about. It is painful to be hated in the intense degree with which Owen hates me."

During the reaction to Darwin's theory

, Huxley's arguments with Owen continued. Owen tried to smear Huxley, by portraying him as an "advocate of man's origins from a transmuted ape" and one of his contributions to the Athenaeum was titled "Ape-Origin of Man as Tested by the Brain". In 1862 (and on other occasions) Huxley took the opportunity to arrange demonstrations of ape brain anatomy (e.g. at the BA meeting, where William Flower

performed the dissection). Visual evidence of the supposedly missing structures (posterior cornu and hippocampus minor) was used, in effect, to indict Owen for perjury. Owen had argued that the absence of those structures in apes were connected with the lesser size to which the ape brains grew, but he then conceded that a poorly developed version might be construed as present without preventing him from arguing that brain size was still the major way of distinguishing apes and humans. Huxley's campaign ran over two years and was devastatingly successful at persuading the overall scientific community, with each "slaying" being followed by a recruiting drive for the Darwinian cause. The spite lingered. While Owen had argued that humans were distinct from apes by virtue of having large brains, Huxley claimed that racial diversity blurred any such distinction. In his paper criticizing Owen, Huxley directly states: "if we place A, the European brain, B, the Bosjesman brain, and C, the orang brain, in a series, the differences between A and B, so far as they have been ascertained, are of the same nature as the chief of those between B and C". Owen countered Huxley by saying the brains of all human races were really of similar size and intellectual ability, and that the fact that humans had brains that were twice the size of large apes like male gorillas, even though humans had much smaller bodies, made humans distinguishable. When Huxley joined the Zoological Society Council, in 1861, Owen left and, in the following year, Huxley moved to stop Owen from being elected to the Royal Society Council, accusing him "of wilful & deliberate falsehood". (See also Thomas Henry Huxley.)

In January 1863, Owen bought the Archaeopteryx

fossil for the British Museum

. It fulfilled Darwin's prediction, that a proto-bird with unfused wing fingers would be found, although Owen described it unequivocally as a bird.

The feuding between Owen and Darwin's supporters continued. In 1871, Owen was found to be involved in a threat to end government funding of Joseph Dalton Hooker

's botanical collection, at Kew

, possibly trying to bring it under his British Museum

. Darwin commented that "I used to be ashamed of hating him so much, but now I will carefully cherish my hatred & contempt to the last days of my life".

and homology

. Owen's theory of the Archetype and Homologies of the Vertebrate Skeleton (1848), subsequently illustrated also by his little work On the Nature of Limbs (1849), regarded the vertebrate frame as consisting of a series of fundamentally identical segments, each modified according to its position and functions. Much of it was fanciful and failed when tested by the facts of embryology

, which Owen systematically ignored, throughout his work. However, though an imperfect and distorted view of certain great truths, it possessed a distinct value at the time of its conception.

To the discussion of the deeper problems of biological philosophy, he made scarcely any direct and definite contributions. His generalities rarely extended beyond strict comparative anatomy, the phenomena of adaptation to function and the facts of geographical or geological distribution. His lecture on virgin reproduction or parthenogenesis

, however, published in 1849, contained the essence of the germ plasm theory, elaborated later by August Weismann

and he made several vague statements concerning the geological succession of genera and species of animals and their possible derivation one from another. He referred, especially, to the changes exhibited by the successive forerunners of the crocodile

s (1884) and horse

s (1868) but it has never become clear how much of the modern doctrines of organic evolution he admitted. He contented himself with the bare remark that "the inductive demonstration of the nature and mode of operation of the laws governing life would henceforth be the great aim of the philosophical naturalist."

He was the first director in Natural History Museum

in London and his statue was in the main hall there until 2009, when it was replaced with a statue of Darwin.

Owen has been described by some as a malicious, dishonest and hateful individual. He has been described in one biography as being a "social experimenter with a penchant for sadism. Addicted to controversy and driven by arrogance and jealousy". Deborah Cadbury

stated that Owen possessed an "almost fanatical egoism with a callous delight in savaging his critics." Indeed, an Oxford University professor once described Owen as "a damned liar. He lied for God and for malice". Gideon Mantell

claimed it was "a pity a man so talented should be so dastardly and envious".

Owen famously credited himself and Georges Cuvier

with the discovery of the Iguanodon

, completely excluding any credit for the original discoverer of the dinosaur, Gideon Mantell

. This was not the first or last time Owen would deliberately claim a discovery as his own, when in fact it was not. It has also been suggested by some authors, including Bill Bryson

in A Short History of Nearly Everything

, that Owen even used his influence in the Royal Society

to ensure that many of Mantell’s research papers were never published. Owen was finally dismissed from the Royal Society's Zoological Council for plagiarism

.

When Mantell suffered an accident that left him permanently crippled, Owen exploited the opportunity by renaming several dinosaurs which had already been named by Mantell, even having the audacity to claim credit for their discovery himself. When Mantell finally died in 1852, an obituary carrying no byline derided Mantell as little more than a mediocre scientist, who brought forth few notable contributions. The obituary’s authorship was universally attributed to Owen by every geologist. The president of the Geological society claimed that it "bespeaks of the lamentable coldness of the heart of the writer". Owen was subsequently denied the presidency of the society for his repeated and pointed antagonism towards Gideon Mantell.

Even more extraordinary was the way Owen ignored the genuine scientific content of Mantell's work. For example, despite the paucity of finds Mantell had worked out that some dinosaurs were bipedal, including Iguanodon

. This remarkable insight was totally ignored by Owen, whose instructions for the Crystal Palace models by Waterhouse Hawkins portrayed Iguanodon as grossly overweight and quadrupedal, with its misidentified thumb on its nose. Mantell did not live to witness the discovery in 1878 of articulated skeletons in a Belgium coal-mine that showed Iguanodon was mostly bipedal (and in that stance could use its thumb for defence). Owen made no comment or retraction; he never did on any errors he made. Moreover, since the earliest known dinosaurs were bipedal, Mantell's idea was indeed perspicacious.

Despite originally starting out on good terms with Darwin, Owen was highly critical of the Origin in large part because Darwin did not refer much to the previous scientific theories of evolution that had been proposed by people like Chambers and himself, and instead compared the theory of evolution by natural selection with the unscientific theory in the Bible.

Despite originally starting out on good terms with Darwin, Owen was highly critical of the Origin in large part because Darwin did not refer much to the previous scientific theories of evolution that had been proposed by people like Chambers and himself, and instead compared the theory of evolution by natural selection with the unscientific theory in the Bible.

Another reason for his criticism of the Origin, some historians claim, was that Owen felt upstaged by Darwin and supporters such as Huxley, and his judgment was clouded by jealousy. Owen in Darwin's opinion was "Spiteful, extremely malignant, clever; the Londoners say he is mad with envy because my book is so talked about". "It is painful to be hated in the intense degree with which Owen hates me". Owen also resorted to the same subterfuge he used against Mantell, writing another anonymous article in the Edinburgh Review

in April 1860. In the article, Owen was critical of Darwin for not offering many new observations, and heaped praise (in the third person) upon himself, while being careful not to associate any particular comment with his own name. Owen did praise, however, the Origins description of Darwin's work on insect behavior and pigeon breeding as "real gems".

Owen was also a party to the threat to end government funding of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

botanical collection (see Joseph Dalton Hooker#Attacks on Hooker and on Kew), orchestrated by Acton Smee Ayrton

:

It has been suggested by some authors that the portrayal of Owen as a vindictive and treacherous man was fostered and encouraged by his rivals (particularly Darwin, Hooker and Huxley) and may be somewhat undeserved. In the first part of his career he was regarded rightly as one of the great scientific figures of the age. In the second part of his career his reputation slipped. This was not solely due to his underhanded dealings with colleagues; it was also due to the serious errors of scientific judgement which were discovered and publicized. A fine example was his decision to classify man in a separate sub-class of the Mammalia (see Man's place in nature). In this Owen had no supporters at all. Also, his unwillingness to come off the fence concerning evolution became increasingly damaging to his reputation as time went on. Owen continued working after his official retirement at the age of 79, but he never recovered the good opinions he had garnered in his younger days.

| url = http://books.google.com/?id=ftvbuluG7xQC

}}

| url = http://www.archive.org/details/liferichardowen00owengoog

| isbn = 0847811883

}}

| url = http://www.archive.org/details/liferichardowen01owengoog

| isbn = 0847811883

}}

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

KCB

Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate mediæval ceremony for creating a knight, which involved bathing as one of its elements. The knights so created were known as Knights of the Bath...

(20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English

English people

The English are a nation and ethnic group native to England, who speak English. The English identity is of early mediaeval origin, when they were known in Old English as the Anglecynn. England is now a country of the United Kingdom, and the majority of English people in England are British Citizens...

biologist

Biologist

A biologist is a scientist devoted to and producing results in biology through the study of life. Typically biologists study organisms and their relationship to their environment. Biologists involved in basic research attempt to discover underlying mechanisms that govern how organisms work...

, comparative anatomist

Comparative anatomy

Comparative anatomy is the study of similarities and differences in the anatomy of organisms. It is closely related to evolutionary biology and phylogeny .-Description:...

and palaeontologist

Paleontology

Paleontology "old, ancient", ὄν, ὀντ- "being, creature", and λόγος "speech, thought") is the study of prehistoric life. It includes the study of fossils to determine organisms' evolution and interactions with each other and their environments...

.

Owen is probably best remembered today for coining the word Dinosauria (meaning "Terrible Reptile

Reptile

Reptiles are members of a class of air-breathing, ectothermic vertebrates which are characterized by laying shelled eggs , and having skin covered in scales and/or scutes. They are tetrapods, either having four limbs or being descended from four-limbed ancestors...

" or "Fearfully Great Reptile

Reptile

Reptiles are members of a class of air-breathing, ectothermic vertebrates which are characterized by laying shelled eggs , and having skin covered in scales and/or scutes. They are tetrapods, either having four limbs or being descended from four-limbed ancestors...

") and for his outspoken opposition to Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin FRS was an English naturalist. He established that all species of life have descended over time from common ancestry, and proposed the scientific theory that this branching pattern of evolution resulted from a process that he called natural selection.He published his theory...

's theory of evolution

Evolution

Evolution is any change across successive generations in the heritable characteristics of biological populations. Evolutionary processes give rise to diversity at every level of biological organisation, including species, individual organisms and molecules such as DNA and proteins.Life on Earth...

by natural selection

Natural selection

Natural selection is the nonrandom process by which biologic traits become either more or less common in a population as a function of differential reproduction of their bearers. It is a key mechanism of evolution....

. He agreed with Darwin that evolution occurred, but thought it was more complex than outlined in Darwin's Origin. Owen's approach to evolution can be seen as having anticipated the issues that have gained greater attention with the recent emergence of evolutionary developmental biology

Evolutionary developmental biology

Evolutionary developmental biology is a field of biology that compares the developmental processes of different organisms to determine the ancestral relationship between them, and to discover how developmental processes evolved...

. He was the driving force behind the establishment, in 1881, of the British Museum (Natural History) in London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

. Bill Bryson

Bill Bryson

William McGuire "Bill" Bryson, OBE, is a best-selling American author of humorous books on travel, as well as books on the English language and on science. Born an American, he was a resident of Britain for most of his adult life before moving back to the US in 1995...

argues that, "by making the Natural History Museum an institution for everyone, Owen transformed our expectations of what museums are for".

Biography

Owen was born in LancasterLancaster, Lancashire

Lancaster is the county town of Lancashire, England. It is situated on the River Lune and has a population of 45,952. Lancaster is a constituent settlement of the wider City of Lancaster, local government district which has a population of 133,914 and encompasses several outlying towns, including...

in 1804, one of six children of a West Indian Merchant named Richard Owen (1754-1809). His mother, Catherine Parrin, was descended from Huguenot

Huguenot

The Huguenots were members of the Protestant Reformed Church of France during the 16th and 17th centuries. Since the 17th century, people who formerly would have been called Huguenots have instead simply been called French Protestants, a title suggested by their German co-religionists, the...

s and he was educated at Lancaster Royal Grammar School

Lancaster Royal Grammar School

Lancaster Royal Grammar School is a voluntary aided, selective grammar school for boys in Lancaster, England. The school has been awarded specialist Technology College and Language College status. Old boys belong to The Old Lancastrians...

. In 1820, he was apprenticed to a local surgeon

Surgery

Surgery is an ancient medical specialty that uses operative manual and instrumental techniques on a patient to investigate and/or treat a pathological condition such as disease or injury, or to help improve bodily function or appearance.An act of performing surgery may be called a surgical...

and apothecary

Apothecary

Apothecary is a historical name for a medical professional who formulates and dispenses materia medica to physicians, surgeons and patients — a role now served by a pharmacist and some caregivers....

and, in 1824, he proceeded as a medical student to the University of Edinburgh

University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh, founded in 1583, is a public research university located in Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland, and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The university is deeply embedded in the fabric of the city, with many of the buildings in the historic Old Town belonging to the university...

. He left the university in the following year and completed his medical course in St Bartholomew's Hospital

St Bartholomew's Hospital

St Bartholomew's Hospital, also known as Barts, is a hospital in Smithfield in the City of London, England.-Early history:It was founded in 1123 by Raherus or Rahere , a favourite courtier of King Henry I...

, London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, where he came under the influence of the eminent surgeon, John Abernethy

John Abernethy (surgeon)

John Abernethy FRS was an English surgeon, grandson of the Reverend John Abernethy.He was born in Coleman Street in the City of London, where his father was a merchant. Educated at Wolverhampton Grammar School, he was apprenticed in 1779 to Sir Charles Blicke , a surgeon at St Bartholomew's...

.

In July 1835 Owen married Caroline Amelia Clift in St Pancras

St Pancras

-Saints:* Pancras of Taormina, martyred in 40 AD in Sicily* Pancras of Rome, the saint martyred c.304 AD after whom the following are directly or indirectly named-United Kingdom:* St Pancras, London, a district of London...

by whom he had one son, William Owen. Richard sadly outlived both his wife and only son and on his death in 1892 he was survived by his three grandchildren and daughter-in-law Emily Owen, whom he left much of his £33,000 fortune to.

William Clift

William Clift, , British naturalist, born at Burcombe, about half a mile from the town of Bodmin in Cornwall, on 14 Feb. 1775, was the youngest of the seven children of Robert Clift, who died a few years later, leaving his wife and family in the depths of poverty.-Education:The boy was sent to...

, conservator of the museum of the Royal College of Surgeons

Royal College of Surgeons of England

The Royal College of Surgeons of England is an independent professional body and registered charity committed to promoting and advancing the highest standards of surgical care for patients, regulating surgery, including dentistry, in England and Wales...

. This congenial occupation soon led him to abandon his intention of medical practice and his life henceforth was devoted to purely scientific labours. He prepared an important series of catalogues of the Hunterian Collection

John Hunter (surgeon)

John Hunter FRS was a Scottish surgeon regarded as one of the most distinguished scientists and surgeons of his day. He was an early advocate of careful observation and scientific method in medicine. The Hunterian Society of London was named in his honour...

, in the Royal College of Surgeons and, in the course of this work, he acquired the unrivalled knowledge of comparative anatomy, which enabled him to enrich all departments of the science and especially facilitated his researches on the remains of extinct animals.

British Museum

The British Museum is a museum of human history and culture in London. Its collections, which number more than seven million objects, are amongst the largest and most comprehensive in the world and originate from all continents, illustrating and documenting the story of human culture from its...

. He then devoted much of his energies to a great scheme for a National Museum of Natural History, which eventually resulted in the removal of the natural history collections of the British Museum to a new building at South Kensington

South Kensington

South Kensington is a district in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in London. It is a built-up area located 2.4 miles west south-west of Charing Cross....

: the British Museum (Natural History) (now the Natural History Museum

Natural History Museum

The Natural History Museum is one of three large museums on Exhibition Road, South Kensington, London, England . Its main frontage is on Cromwell Road...

). He retained office until the completion of this work, in December, 1883, when he was made a knight of the Order of the Bath

Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate mediæval ceremony for creating a knight, which involved bathing as one of its elements. The knights so created were known as Knights of the Bath...

. He lived quietly in retirement at Sheen Lodge, Richmond Park

Richmond Park

Richmond Park is a 2,360 acre park within London. It is the largest of the Royal Parks in London and Britain's second largest urban walled park after Sutton Park, Birmingham. It is close to Richmond, Ham, Kingston upon Thames, Wimbledon, Roehampton and East Sheen...

, until his death in 1892.

His career was tainted by accusations that he failed to give credit to the work of others and even tried to appropriate it in his own name. This came to a head in 1846, when he was awarded the Royal Medal

Royal Medal

The Royal Medal, also known as The Queen's Medal, is a silver-gilt medal awarded each year by the Royal Society, two for "the most important contributions to the advancement of natural knowledge" and one for "distinguished contributions in the applied sciences" made within the Commonwealth of...

for a paper he had written on belemnites. Owen had failed to acknowledge that the belemnite had been discovered by Chaning Pearce, an amateur biologist, four years earlier. As a result of the ensuing scandal, he was voted off the councils of the Zoological Society

Zoological Society of London

The Zoological Society of London is a charity devoted to the worldwide conservation of animals and their habitats...

and the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

.

Owen always tended to support orthodox men of science and the status quo. The royal family presented him with the cottage in Richmond Park and Robert Peel

Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet was a British Conservative statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 10 December 1834 to 8 April 1835, and again from 30 August 1841 to 29 June 1846...

put him on the Civil List

Civil list

-United Kingdom:In the United Kingdom, the Civil List is the name given to the annual grant that covers some expenses associated with the Sovereign performing their official duties, including those for staff salaries, State Visits, public engagements, ceremonial functions and the upkeep of the...

. In 1843, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences or Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien is one of the Royal Academies of Sweden. The Academy is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization which acts to promote the sciences, primarily the natural sciences and mathematics.The Academy was founded on 2...

.

Work on invertebrates

While occupied with the cataloguing of the Hunterian collection, Owen did not confine his attention to the preparations before him but also seized every opportunity to dissect fresh subjects. He was allowed to examine all animals which died in London ZooZoological Society of London

The Zoological Society of London is a charity devoted to the worldwide conservation of animals and their habitats...

's gardens and, when the Zoo began to publish scientific proceedings, in 1831, he was the most voluminous contributor of anatomical papers. His first notable publication, however, was his Memoir on the Pearly Nautilus

Nautilus

Nautilus is the common name of marine creatures of cephalopod family Nautilidae, the sole extant family of the superfamily Nautilaceae and of its smaller but near equal suborder, Nautilina. It comprises six living species in two genera, the type of which is the genus Nautilus...

(London, 1832), which was soon recognized as a classic. Henceforth, he continued to make important contributions to every department of comparative anatomy and zoology

Zoology

Zoology |zoölogy]]), is the branch of biology that relates to the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinct...

, for a period of over fifty years. In the sponges, Owen was the first to describe the now well-known Venus' Flower Basket

Venus' Flower Basket

The Venus' Flower Basket, or Euplectella aspergillum is a hexactinellid sponge in the phylum Porifera inhabiting the deep ocean. In traditional Asian cultures, this particular sponge was given as a wedding gift because the sponge symbiotically houses two small shrimp, a male and a female, who live...

or Euplectella

Euplectella

Euplectella is a genus of glass sponges which includes the well-known Venus' Flower Basket, E. aspergillum.-Species:*Euplectella aspera*Euplectella aspergillum*Euplectella crassistellata*Euplectella cucumer...

(1841, 1857). Among Entozoa, his most noteworthy discovery was that of Trichina spiralis (1835), the parasite infesting the muscles of man in the disease now termed trichinosis

Trichinosis

Trichinosis, also called trichinellosis, or trichiniasis, is a parasitic disease caused by eating raw or undercooked pork or wild game infected with the larvae of a species of roundworm Trichinella spiralis, commonly called the trichina worm. There are eight Trichinella species; five are...

(see also, however, Sir James Paget

James Paget

Sir James Paget, 1st Baronet was a British surgeon and pathologist who is best remembered for Paget's disease and who is considered, together with Rudolf Virchow, as one of the founders of scientific medical pathology. His famous works included Lectures on Tumours and Lectures on Surgical Pathology...

). Of Brachiopod

Brachiopod

Brachiopods are a phylum of marine animals that have hard "valves" on the upper and lower surfaces, unlike the left and right arrangement in bivalve molluscs. Brachiopod valves are hinged at the rear end, while the front can be opened for feeding or closed for protection...

a he made very special studies, which much advanced knowledge and settled the classification, which has long been adopted. Among Mollusca, he not only described the pearly nautilus, but also Spirula (1850) and other Cephalopod

Cephalopod

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan class Cephalopoda . These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral body symmetry, a prominent head, and a set of arms or tentacles modified from the primitive molluscan foot...

a, both living and extinct and it was he who proposed the universally-accepted subdivision of this class into the two orders of Dibranchiata and Tetrabranchiata (1832). The problematical Arthropod

Arthropod

An arthropod is an invertebrate animal having an exoskeleton , a segmented body, and jointed appendages. Arthropods are members of the phylum Arthropoda , and include the insects, arachnids, crustaceans, and others...

Limulus

Horseshoe crab

The Atlantic horseshoe crab, Limulus polyphemus, is a marine chelicerate arthropod. Despite its name, it is more closely related to spiders, ticks, and scorpions than to crabs. Horseshoe crabs are most commonly found in the Gulf of Mexico and along the northern Atlantic coast of North America...

was also the subject of a special memoir by him, in 1873.

Fish, reptiles, birds, and naming of dinosaurs

Owen's technical descriptions of the VertebrataVertebrate

Vertebrates are animals that are members of the subphylum Vertebrata . Vertebrates are the largest group of chordates, with currently about 58,000 species described. Vertebrates include the jawless fishes, bony fishes, sharks and rays, amphibians, reptiles, mammals, and birds...

were still more numerous and extensive than those of the invertebrate

Invertebrate

An invertebrate is an animal without a backbone. The group includes 97% of all animal species – all animals except those in the chordate subphylum Vertebrata .Invertebrates form a paraphyletic group...

animals. His Comparative Anatomy and Physiology of Vertebrates (3 vols. London 1866–1868) was indeed the result of more personal research than any similar work since Georges Cuvier

Georges Cuvier

Georges Chrétien Léopold Dagobert Cuvier or Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric Cuvier , known as Georges Cuvier, was a French naturalist and zoologist...

's Leçons d'anatomie comparée. He not only studied existing forms but also devoted great attention to the remains of extinct groups, and followed Cuvier, the pioneer of vertebrate paleontology

Vertebrate paleontology

Vertebrate paleontology is a large subfield to paleontology seeking to discover the behavior, reproduction and appearance of extinct animals with vertebrae or a notochord, through the study of their fossilized remains...

. Early in his career, he made exhaustive studies of teeth of existing and extinct animals and published his profusely illustrated work on Odontography (1840–1845). He discovered and described the remarkably complex structure of the teeth of the extinct animals which he named Labyrinthodonts

Labyrinthodontia

Labyrinthodontia is an older term for any member of the extinct subclass of amphibians, which constituted some of the dominant animals of Late Paleozoic and Early Mesozoic times . The group is ancestral to all extant landliving vertebrates, and as such constitutes an evolutionary grade rather...

. Among his writings on fish

Fish

Fish are a paraphyletic group of organisms that consist of all gill-bearing aquatic vertebrate animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish, as well as various extinct related groups...

, his memoir on the African lungfish, which he named Protopterus

Protopterus

The African lungfishes are the genus Protopterus and constitute the four species of lungfish found in Africa. Protopterus is the sole genus in the family Protopteridae.-Description:...

, laid the foundations for the recognition of the Dipnoi

Lungfish

Lungfish are freshwater fish belonging to the Subclass Dipnoi. Lungfish are best known for retaining characteristics primitive within the Osteichthyes, including the ability to breathe air, and structures primitive within Sarcopterygii, including the presence of lobed fins with a well-developed...

by Johannes Müller

Johannes Peter Müller

Johannes Peter Müller , was a German physiologist, comparative anatomist, and ichthyologist not only known for his discoveries but also for his ability to synthesize knowledge.-Early years and education:...

. He also later pointed out the serial connection between the teleostean and ganoid fishes, grouping them in one sub-class, the Teleostomi

Teleostomi

Teleostomi is a clade of jawed vertebrates that includes the tetrapods, bony fish, and the wholly extinct acanthodian fish. Key characters of this group include an operculum and a single pair of respiratory openings, features which were lost or modified in some later representatives...

.

Most of his work on reptile

Reptile

Reptiles are members of a class of air-breathing, ectothermic vertebrates which are characterized by laying shelled eggs , and having skin covered in scales and/or scutes. They are tetrapods, either having four limbs or being descended from four-limbed ancestors...

s related to the skeleton

Skeleton

The skeleton is the body part that forms the supporting structure of an organism. There are two different skeletal types: the exoskeleton, which is the stable outer shell of an organism, and the endoskeleton, which forms the support structure inside the body.In a figurative sense, skeleton can...

s of extinct forms and his chief memoirs, on British specimens, were reprinted in a connected series in his History of British Fossil Reptiles (4 vols. London 1849–1884). He published the first important general account of the great group of Mesozoic

Mesozoic

The Mesozoic era is an interval of geological time from about 250 million years ago to about 65 million years ago. It is often referred to as the age of reptiles because reptiles, namely dinosaurs, were the dominant terrestrial and marine vertebrates of the time...

land-reptiles, and he coined the name Dinosauria from Greek

Greek language

Greek is an independent branch of the Indo-European family of languages. Native to the southern Balkans, it has the longest documented history of any Indo-European language, spanning 34 centuries of written records. Its writing system has been the Greek alphabet for the majority of its history;...

δεινός (deinos) "terrible, powerful, wondrous" + σαῦρος (sauros) "lizard". Owen used 3 genera to define the dinosaurs: the carnivorous Megalosaurus

Megalosaurus

Megalosaurus is a genus of large meat-eating theropod dinosaurs of the Middle Jurassic period of Europe...

, the herviborous Iguanodon

Iguanodon

Iguanodon is a genus of ornithopod dinosaur that lived roughly halfway between the first of the swift bipedal hypsilophodontids and the ornithopods' culmination in the duck-billed dinosaurs...

and armoured Hylaeosaurus

Hylaeosaurus

Hylaeosaurus is the most obscure of the three animals used by Sir Richard Owen to first define the new group Dinosauria, in 1842. The original specimen, recovered by Gideon Mantell from the Tilgate Forest in the south of England in 1832, now resides in the Natural History Museum of London, where...

. He also first recognized the curious early Mesozoic land-reptiles, with affinities both to amphibians and mammal

Mammal

Mammals are members of a class of air-breathing vertebrate animals characterised by the possession of endothermy, hair, three middle ear bones, and mammary glands functional in mothers with young...

s, which he termed Anomodontia (the mammal-like reptiles, Therapsida

Therapsida

Therapsida is a group of the most advanced synapsids, and include the ancestors of mammals. Many of the traits today seen as unique to mammals had their origin within early therapsids, including hair, lactation, and an erect posture. The earliest fossil attributed to Therapsida is believed to be...

). Most of these were obtained from South Africa

South Africa

The Republic of South Africa is a country in southern Africa. Located at the southern tip of Africa, it is divided into nine provinces, with of coastline on the Atlantic and Indian oceans...

, beginning in 1845 (Dicynodon

Dicynodon

Dicynodon is a type of dicynodont therapsid that flourished during the Permian period between 251 and 299 million years ago. Like all dicynodonts, it was herbivorous. This animal was toothless, except for prominent tusks, hence the name...

) and eventually furnished materials for his Catalogue of the Fossil Reptilia of South Africa, issued by the British Museum

British Museum

The British Museum is a museum of human history and culture in London. Its collections, which number more than seven million objects, are amongst the largest and most comprehensive in the world and originate from all continents, illustrating and documenting the story of human culture from its...

, in 1876. Among his writings on bird

Bird

Birds are feathered, winged, bipedal, endothermic , egg-laying, vertebrate animals. Around 10,000 living species and 188 families makes them the most speciose class of tetrapod vertebrates. They inhabit ecosystems across the globe, from the Arctic to the Antarctic. Extant birds range in size from...

s, his classical memoir on the kiwi

Kiwi

Kiwi are flightless birds endemic to New Zealand, in the genus Apteryx and family Apterygidae.At around the size of a domestic chicken, kiwi are by far the smallest living ratites and lay the largest egg in relation to their body size of any species of bird in the world...

(1840–1846), a long series of papers on the extinct dinornithidae

Moa

The moa were eleven species of flightless birds endemic to New Zealand. The two largest species, Dinornis robustus and Dinornis novaezelandiae, reached about in height with neck outstretched, and weighed about ....

of New Zealand

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

, other memoirs on aptornis

Adzebill

The adzebills, genus Aptornis, were two closely related bird species, the North Island Adzebill, Aptornis otidiformis, and the South Island Adzebill, Aptornis defossor, of the extinct family Aptornithidae. The family was endemic to New Zealand.They have been placed in the Gruiformes but this is not...

, the takahe

Takahe

The Takahē or South Island Takahē, Porphyrio hochstetteri is a flightless bird indigenous to New Zealand and belonging to the rail family. It was thought to be extinct after the last four known specimens were taken in 1898...

, the dodo

Dodo

The dodo was a flightless bird endemic to the Indian Ocean island of Mauritius. Related to pigeons and doves, it stood about a meter tall, weighing about , living on fruit, and nesting on the ground....

and the Great Auk

Great Auk

The Great Auk, Pinguinus impennis, formerly of the genus Alca, was a large, flightless alcid that became extinct in the mid-19th century. It was the only modern species in the genus Pinguinus, a group of birds that formerly included one other species of flightless giant auk from the Atlantic Ocean...

, may be especially mentioned. His monograph on Archaeopteryx

Archaeopteryx

Archaeopteryx , sometimes referred to by its German name Urvogel , is a genus of theropod dinosaur that is closely related to birds. The name derives from the Ancient Greek meaning "ancient", and , meaning "feather" or "wing"...

(1863), the long-tailed, toothed bird from the Bavaria

Bavaria

Bavaria, formally the Free State of Bavaria is a state of Germany, located in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the largest state by area, forming almost 20% of the total land area of Germany...

n lithographic stone, is also an epoch-making work.

With Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins was an English sculptor and natural history artist renowned for combining both in his work on the life-size models of dinosaurs in the Crystal Palace Park, Sydenham, south London...

, Owen helped create the first life-size sculptures depicting dinosaurs as he thought they may have appeared. Some models were initially created for the Great Exhibition of 1851, but 33 were eventually produced when the Crystal Palace

The Crystal Palace

The Crystal Palace was a cast-iron and glass building originally erected in Hyde Park, London, England, to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. More than 14,000 exhibitors from around the world gathered in the Palace's of exhibition space to display examples of the latest technology developed in...

was relocated to Sydenham

Sydenham

Sydenham is an area and electoral ward in the London Borough of Lewisham; although some streets towards Crystal Palace Park, Forest Hill and Penge are outside the ward and in the London Borough of Bromley, and some streets off Sydenham Hill are in the London Borough of Southwark. Sydenham was in...

, in South London. Owen famously hosted a dinner for 21 prominent men of science inside the hollow concrete Iguanodon

Iguanodon

Iguanodon is a genus of ornithopod dinosaur that lived roughly halfway between the first of the swift bipedal hypsilophodontids and the ornithopods' culmination in the duck-billed dinosaurs...

on New Year's Eve 1853. However, in 1849, a few years before his death in 1852, Gideon Mantell

Gideon Mantell

Gideon Algernon Mantell MRCS FRS was an English obstetrician, geologist and palaeontologist...

had realised that Iguanodon, of which he was the discoverer, was not a heavy, pachyderm

Pachydermata

Pachydermata is an obsolete order of mammals described by Gottlieb Storr, Georges Cuvier and others, at one time recognized by many systematists...

-like animal, as Owen was putting forward, but had slender forelimbs; his death left him unable to participate in the creation of the Crystal Palace dinosaur sculptures

Crystal Palace Dinosaurs

The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, also known as Dinosaur Court, are a series of sculptures of dinosaurs and extinct mammals located in Crystal Palace, London. Commissioned in 1852 and unveiled in 1854, they were the first dinosaur sculptures in the world, pre-dating the publication of Charles Darwin's...

, and so Owen's vision of dinosaurs became that seen by the public. He had nearly two dozen lifesize sculpture

Sculpture

Sculpture is three-dimensional artwork created by shaping or combining hard materials—typically stone such as marble—or metal, glass, or wood. Softer materials can also be used, such as clay, textiles, plastics, polymers and softer metals...

s of various prehistoric animals built out of concrete

Concrete

Concrete is a composite construction material, composed of cement and other cementitious materials such as fly ash and slag cement, aggregate , water and chemical admixtures.The word concrete comes from the Latin word...

sculpted over a steel

Steel

Steel is an alloy that consists mostly of iron and has a carbon content between 0.2% and 2.1% by weight, depending on the grade. Carbon is the most common alloying material for iron, but various other alloying elements are used, such as manganese, chromium, vanadium, and tungsten...

and brick

Brick

A brick is a block of ceramic material used in masonry construction, usually laid using various kinds of mortar. It has been regarded as one of the longest lasting and strongest building materials used throughout history.-History:...

framework; two Iguanodon, one standing and one resting on its belly, were included.

Work on mammals

.jpg)

Right of first refusal

Right of first refusal is a contractual right that gives its holder the option to enter a business transaction with the owner of something, according to specified terms, before the owner is entitled to enter into that transaction with a third party...

on any freshly dead animal at the London Zoo. His wife once arrived home to find the carcass of a newly deceased rhinoceros in her front hallway.

With regard to living mammals, the more striking of Owen's contributions relate to the monotreme

Monotreme

Monotremes are mammals that lay eggs instead of giving birth to live young like marsupials and placental mammals...

s, marsupial

Marsupial

Marsupials are an infraclass of mammals, characterized by giving birth to relatively undeveloped young. Close to 70% of the 334 extant species occur in Australia, New Guinea, and nearby islands, with the remaining 100 found in the Americas, primarily in South America, but with thirteen in Central...

s and the anthropoid ape

Ape

Apes are Old World anthropoid mammals, more specifically a clade of tailless catarrhine primates, belonging to the biological superfamily Hominoidea. The apes are native to Africa and South-east Asia, although in relatively recent times humans have spread all over the world...

s. He was also the first to recognize and name the two natural groups of typical Ungulate, the odd-toed (Perissodactyla

Odd-toed ungulate

An odd-toed ungulate is a mammal with hooves that feature an odd number of toes. Odd-toed ungulates comprise the order Perissodactyla . The middle toe on each hoof is usually larger than its neighbours...

) and the even-toed (Artiodactyla

Even-toed ungulate

The even-toed ungulates are ungulates whose weight is borne about equally by the third and fourth toes, rather than mostly or entirely by the third as in odd-toed ungulates such as horses....

), while describing some fossil remains, in 1848. Most of his writings on mammals, however, deal with extinct forms, to which his attention seems to have been first directed by the remarkable fossils collected by Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin FRS was an English naturalist. He established that all species of life have descended over time from common ancestry, and proposed the scientific theory that this branching pattern of evolution resulted from a process that he called natural selection.He published his theory...

, in South America

South America

South America is a continent situated in the Western Hemisphere, mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere. The continent is also considered a subcontinent of the Americas. It is bordered on the west by the Pacific Ocean and on the north and east...

. Toxodon

Toxodon

Toxodon is an extinct mammal of the late Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs about 2.6 million to 16,500 years ago. It was indigenous to South America, and was probably the most common large-hoofed mammal in South America at the time of its existence....

, from the pampas, was then described and gave the earliest clear evidence of an extinct generalized hoof animal, a pachyderm with affinities to the Rodent

Rodent

Rodentia is an order of mammals also known as rodents, characterised by two continuously growing incisors in the upper and lower jaws which must be kept short by gnawing....

ia, Edentata and herbivorous Cetacea

Cetacea

The order Cetacea includes the marine mammals commonly known as whales, dolphins, and porpoises. Cetus is Latin and is used in biological names to mean "whale"; its original meaning, "large sea animal", was more general. It comes from Ancient Greek , meaning "whale" or "any huge fish or sea...

. Owen's interest in South American extinct mammals then led to the recognition of the giant armadillo

Armadillo

Armadillos are New World placental mammals, known for having a leathery armor shell. Dasypodidae is the only surviving family in the order Cingulata, part of the superorder Xenarthra along with the anteaters and sloths. The word armadillo is Spanish for "little armored one"...

, which he named Glyptodon

Glyptodon

Glyptodon was a large, armored mammal of the family Glyptodontidae, a relative of armadillos that lived during the Pleistocene Epoch. It was roughly the same size and weight as a Volkswagen Beetle, though flatter in shape...

(1839) and to classic memoirs on the giant ground-sloth

Ground sloth

Ground sloths are a diverse group of extinct sloths, in the mammalian superorder Xenarthra. Their most recent survivors lived in the Antilles, where it has been proposed they may have survived until 1550 CE; however, the youngest AMS radiocarbon date reported is 4190 BP, calibrated to c. 4700 BP...

s, Mylodon

Mylodon

Mylodon is an extinct genus of giant ground sloth that lived in the Patagonia area of South America until roughly 10,000 years ago.Mylodon weighed about and stood up to tall when raised up on its hind legs. Preserved dung has shown it was a herbivore. It had very thick hide and had osteoderms...

(1842) and Megatherium

Megatherium

Megatherium was a genus of elephant-sized ground sloths endemic to Central America and South America that lived from the Pliocene through Pleistocene existing approximately...

(1860), besides other important contributions.

At the same time, Sir Thomas Mitchell's discovery of fossil bones, in New South Wales

New South Wales

New South Wales is a state of :Australia, located in the east of the country. It is bordered by Queensland, Victoria and South Australia to the north, south and west respectively. To the east, the state is bordered by the Tasman Sea, which forms part of the Pacific Ocean. New South Wales...

, provided material for the first of Owen's long series of papers on the extinct mammals of Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

, which were eventually reprinted in book-form in 1877. He discovered Diprotodon and Thylacoleo, besides extinct kangaroo

Kangaroo

A kangaroo is a marsupial from the family Macropodidae . In common use the term is used to describe the largest species from this family, especially those of the genus Macropus, Red Kangaroo, Antilopine Kangaroo, Eastern Grey Kangaroo and Western Grey Kangaroo. Kangaroos are endemic to the country...

s and wombat

Wombat

Wombats are Australian marsupials; they are short-legged, muscular quadrupeds, approximately in length with a short, stubby tail. They are adaptable in their habitat tolerances, and are found in forested, mountainous, and heathland areas of south-eastern Australia, including Tasmania, as well as...

s, of gigantic size. While occupied with so much material from abroad, Owen was also busily collecting facts for an exhaustive work on similar fossils from the British Isles and, in 1844-1846, he published his History of British Fossil Mammals and Birds, which was followed by many later memoirs, notably his Monograph of the Fossil Mammalia of the Mesozoic Formations (Palaeont. Soc., 1871). One of his latest publications was a little work entitled Antiquity of Man as deduced from the Discovery of a Human Skeleton during Excavations of the Docks at Tilbury (London, 1884).

Owen, Darwin, and the theory of evolution

Second voyage of HMS Beagle

The second voyage of HMS Beagle, from 27 December 1831 to 2 October 1836, was the second survey expedition of HMS Beagle, under captain Robert FitzRoy who had taken over command of the ship on its first voyage after her previous captain committed suicide...

, Darwin

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin FRS was an English naturalist. He established that all species of life have descended over time from common ancestry, and proposed the scientific theory that this branching pattern of evolution resulted from a process that he called natural selection.He published his theory...

had at his disposal a considerable collection of specimens and, on 29 October 1836, he was introduced by Charles Lyell

Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, Kt FRS was a British lawyer and the foremost geologist of his day. He is best known as the author of Principles of Geology, which popularised James Hutton's concepts of uniformitarianism – the idea that the earth was shaped by slow-moving forces still in operation...

to Owen, who agreed to work on fossil bones collected in South America

South America

South America is a continent situated in the Western Hemisphere, mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere. The continent is also considered a subcontinent of the Americas. It is bordered on the west by the Pacific Ocean and on the north and east...

. Owen's subsequent revelations, that the extinct giant creatures were rodents and sloths, showed that they were related to current species in the same locality, rather than being relatives of similarly sized creatures in Africa

Africa

Africa is the world's second largest and second most populous continent, after Asia. At about 30.2 million km² including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of the Earth's total surface area and 20.4% of the total land area...

, as Darwin had originally thought. This was one of the many influences which led Darwin to later formulate his own ideas on the concept of natural selection

Natural selection

Natural selection is the nonrandom process by which biologic traits become either more or less common in a population as a function of differential reproduction of their bearers. It is a key mechanism of evolution....

.

At this time, Owen talked of his theories, influenced by Johannes Peter Müller

Johannes Peter Müller

Johannes Peter Müller , was a German physiologist, comparative anatomist, and ichthyologist not only known for his discoveries but also for his ability to synthesize knowledge.-Early years and education:...

, that living matter had an "organising energy", a life-force that directed the growth of tissues and also determined the lifespan of the individual and of the species. Darwin was reticent about his own thoughts, understandably, when, on 19 December 1838, as secretary of the Geological Society of London

Geological Society of London

The Geological Society of London is a learned society based in the United Kingdom with the aim of "investigating the mineral structure of the Earth"...

, he saw Owen and his allies ridicule the Lamarckian 'heresy' of Darwin's old tutor, Robert Edmund Grant. In 1841, when the recently married Darwin was ill, Owen was one of the few scientific friends to visit; however, Owen's opposition to any hint of transmutation

Transmutation of species

Transmutation of species was a term used by Jean Baptiste Lamarck in 1809 for his theory that described the altering of one species into another, and the term is often used to describe 19th century evolutionary ideas that preceded Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection...

made Darwin keep quiet about his hypothesis.

Sometime during the 1840s Owen came to the conclusion that species arise as the result of some sort of evolutionary process. He believed that there was a total of six possible mechanisms: parthenogenesis, prolonged development, premature birth, congenital malformations, Lamarckian atrophy, Lamarckian hypertrophy and transmutation, of which he thought transmutation was the least likely. The historian of science Evelleen Richards has argued that Owen was likely sympathetic to developmental theories of evolution, but backed away from publicly proclaiming them after the critical reaction that had greeted the anonymously-published evolutionary book Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation

Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation

Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation is a unique work of speculative natural history published anonymously in England in 1844. It brought together various ideas of stellar evolution with the progressive transmutation of species in an accessible narrative which tied together numerous...

in 1844 (it was revealed only decades later that the book had been authored by publisher Robert Chambers

Robert Chambers

Robert Chambers was a Scottish publisher, geologist, proto-evolutionary thinker, author and journal editor who, like his elder brother and business partner William Chambers, was highly influential in mid-19th century scientific and political circles.Chambers was an early phrenologist, and was the...

). Owen had been criticized for his own evolutionary remarks in his Nature of the Limbs in 1849. At the end of On the Nature of Limbs Owen had suggested that humans ultimately evolved from fish as the result of natural laws, which resulted in him getting criticized in the Manchester Spectator for denying species like humans were created by God.

During the development of Darwin's theory

Development of Darwin's theory

Following the inception of Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection in 1838, the development of Darwin's theory to explain the "mystery of mysteries" of how new species originated was his "prime hobby" in the background to his main occupation of publishing the scientific results of the Beagle...

, his investigation of barnacles showed, in 1849, how their segmentation related to other crustaceans, showing how they had diverged from their relatives. To both Darwin and Owen such "homologies" in comparative anatomy was evidence of descent. Owen demonstrated fossil evidence of an evolutionary sequence of horses, as supporting his idea of development from archetypes in "ordained continuous becoming" and, in 1854, gave a British Association

British Association for the Advancement of Science

frame|right|"The BA" logoThe British Association for the Advancement of Science or the British Science Association, formerly known as the BA, is a learned society with the object of promoting science, directing general attention to scientific matters, and facilitating interaction between...

talk on the impossibility of bestial apes, such as the recently discovered gorilla

Gorilla

Gorillas are the largest extant species of primates. They are ground-dwelling, predominantly herbivorous apes that inhabit the forests of central Africa. Gorillas are divided into two species and either four or five subspecies...

, standing erect and being transmuted into men, but Owen did not rule out the possibility that humans evolved from other extinct animals by evolutionary mechanisms other than transmutation. Working class militants were trumpeting man's monkey origins, and in 1861 Karl Marx

Karl Marx