Joseph Dalton Hooker

Encyclopedia

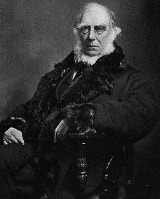

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker OM

, GCSI

, CB

, MD

, FRS (30 June 1817 – 10 December 1911) was one of the greatest British botanists and explorers of the 19th century. Hooker was a founder of geographical botany, and Charles Darwin's closest friend. He was Director of the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew, for twenty years, in succession to his father, William Jackson Hooker

, and was awarded the highest honours of British science.

, Suffolk

, England

. He was the second son of the famous botanist Sir William Jackson Hooker

and Maria Sarah Turner, eldest daughter of the banker Dawson Turner

and sister-in-law of Francis Palgrave

. From age seven, Hooker attended his father's lectures at Glasgow University where he was Regius Professor of Botany

. Joseph formed an early interest in plant distribution and the voyages of explorers like Captain James Cook

. He was educated at the Glasgow High School

and went on to study medicine at Glasgow University, graduating M.D.

in 1839. This degree qualified him for employment in the Naval Medical Service: he joined renowned polar explorer Captain James Clark Ross

's Antarctic

expedition to the South Magnetic Pole after receiving a commission as Assistant-Surgeon on HMS Erebus.

. They had four sons and three daughters:

After his first wife's death in 1874, in 1876 he married Hyacinth Jardine (1842–1921), daughter of William Samuel Symonds

and the widow of Sir William Jardine. They had two sons:

offered a grave near Darwin's in the nave

but also insisted that Hooker be cremated

before. His widow, Hyacinth, declined the proposal and eventually Hooker's body was buried, as he wished to be, alongside his father in the churchyard of St. Anne's Church, Kew

, on Kew Green, within short distance of Kew Gardens.

. This position included duties at the Royal Botanic Gardens of Scotland

, and so the appointment was influenced by local politicians. An unusually protracted struggle ensued, resulting in the election of the locally born and bred botanist, John Hutton Balfour

. The Darwin correspondence

, now public, makes clear Darwin's sense of shock at this unexpected outcome. Hooker declined a chair at Glasgow University which became vacant on Balfour's appointment. Instead, he took a position as botanist to the Geological Survey of Great Britain in 1846. He began work on palaeobotany, searching for fossil plants in the coal-beds of Wales

, eventually discovering the first coal ball

in 1855. He became engaged to Frances Henslow, daughter of Charles Darwin

's botany tutor John Stevens Henslow

, but he was keen to continue to travel and gain more experience in the field. He wanted to travel to India

and the Himalayas

. In 1847 his father nominated him to travel to India

and collect plants for Kew

.

When Hooker returned to England, his father had been appointed director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

, and so was now a prominent man of science. William Hooker, through his connections, secured an Admiralty grant of £1000 to defray the cost of plates for his son's Botany of the Antarctic Voyages, and an annual stipend of £200 for Joseph while he worked on the flora. Hooker's flora was also to include that collected on the voyages of Cook and Menzies held by the British Museum and collections made on the Beagle. The floras were illustrated by Walter Hood Fitch

(trained in botanical illustration by William Hooker), who would go on to become the most prolific Victorian botanical artist.

Hooker's collections from the voyage were described eventually in one of two volumes published as the Flora Antarctica (1844–47). In the Flora he wrote about island

s and their role in plant geography: the work made Hooker's reputation as a systemist and plant geographer. His works on the voyage were completed with Flora Novae-Zelandiae (1851–53) and Flora Tasmaniae (1853–59).

and HMS Terror

; it was the last major voyage of exploration made entirely under sail. Hooker was the youngest of the 128 man crew. He sailed on the Erebus and was assistant to Robert McCormick

, who in addition to being the ship's Surgeon was instructed to collect zoological and geological specimens. The ships sailed on 30 September 1839. Before journeying to Antarctica they visited Madeira

, Tenerife

, Santiago

and Quail Island in the Cape Verde

archipelago, St Paul Rocks

, Trinidade

east of Brazil, St Helena, and the Cape of Good Hope

. Hooker made plant

collections at each location and while travelling drew these and specimens of algae

and sea life pulled aboard using tow nets.

From the Cape they entered the southern ocean. Their first stop was the Crozet Islands

where they set down on Possession Island to deliver coffee to sealers. They departed for the Kerguelen Islands

where they would spend several days. Hooker identified 18 flowering plants, 35 moss

es and liverwort

s, 25 lichen

s and 51 algae, including some that were not described by surgeon William Anderson when James Cook had visited the islands in 1772. The expedition spent some time in Hobart

, Van Diemen's Land

, and then moved on to the Auckland Islands

and Campbell Island

, and onward to Antarctica to locate the South Magnetic Pole. After spending 5 months in the Antarctic they returned to resupply in Hobart, then went on to Sydney

, and the Bay of Islands

in New Zealand

. They left New Zealand to return to Antarctica. After spending 138 days at sea, and a collision between the Erebus and Terror, they sailed to the Falkland Islands

, to Tierra del Fuego

, back to the Falklands and onward to their third sortie into the Antarctic. They made a landing at Cockburn Island

and after leaving the Antarctic, stopped at the Cape, St Helena and Ascension Island

. The ships arrived back in England on 4 September 1843; the voyage had been a success for Ross as it was the first to confirm the existence of the southern continent and chart much of its coastline.

On 11 November 1847 Hooker left England for his three year long Himalayan

On 11 November 1847 Hooker left England for his three year long Himalayan

expedition; he would be the first European to collect plants in the Himalaya. He received free passage on HMS Sidon

, to the Nile

and then travelled overland to Suez

where he boarded a ship to India. He arrived in Calcutta

on 12 January 1848, then travelled by elephant to Mirzapur

, up the Ganges by boat to Siliguri

and overland by pony to Darjeeling, arriving on 16 April 1848.

Hooker's expedition was based in Darjeeling where he stayed with naturalist Brian Houghton Hodgson

. Through Hodgson he met British East India Company representative Archibald Campbell

who negotiated Hooker's admission to Sikkim

, which was finally approved in 1849 (He was to be briefly taken prisoner by the Raja of Sikkim). Meanwhile, Hooker wrote to Darwin relaying to him the habits of animals in India, and collected plants in Bengal

. He explored with local resident Charles Barnes, then travelled along the Great Runjeet river to its junction with the Tista River and Tonglu mountain in the Singalila range on the border with Nepal

. Hooker and a sizable party of local assistants departed for eastern Nepal on 27 October 1848. They travelled to Zongri, west over the spurs of Kangchenjunga

Hooker and a sizable party of local assistants departed for eastern Nepal on 27 October 1848. They travelled to Zongri, west over the spurs of Kangchenjunga

, and north west along Nepal's passes into Tibet

. In April 1849 he planned a longer expedition into Sikkim. Leaving on 3 May, he travelled north west up the Lachen Valley

to the Kongra Lama Pass and then to the Lachoong Pass. Campbell and Hooker were imprisoned by the Dewan of Sikkim

when they were travelling towards the Chola Pass in Tibet

. A British team was sent to negotiate with the king of Sikkim. However, they were released without any bloodshed and Hooker returned to Darjeeling where he spent January and February 1850 writing his journals, replacing specimens lost during his detention and planning a journey for his last year in India.

Reluctant to return to Sikkim, and unenthusiastic about travelling in Bhutan

, he chose to make his last Himalayan expedition to Sylhet

and the Khasi Hills

in Assam

. He was accompanied by Thomas Thomson, a fellow student from Glasgow University. They left Darjeeling on 1 May 1850, then sailed to the Bay of Bengal

and travelled overland by elephant to the Khasi Hills and established a headquarters for their studies in Churra where they stayed until 9 December, when they began their trip back to England.

Hooker's survey of hitherto unexplored regions, the Himalayan Journals, dedicated to Charles Darwin

, was published by the Calcutta Trigonometrical Survey

Office in 1854, abbreviated again in 1855 and later by (The Minerva Library of Famous Books) Ward, Lock, Bowden & Co., 1891.

, the leading American botanist of the day. They wished to investigate the connection between the floras of eastern United States and those of eastern continental Asia and Japan; and the line of demarkation between Arctic floras of America and Greenland. As probable causes they considered the Glacial periods and an earlier land connection with an Arctic continent. "A difficult question was why in the great mountain chains of the Western United States there appeared to be only a few botanical enclaves of plants of eastern-Asiatic afinities among plants of Mexican and more southern types."

Hooker visited a number of cities and botanical institutions before moving west and climbing to 9,000 ft to camp at La Veta. From Fort Garland

they climbed the Sierra Blanca

at 14,500 ft. After returning to La Veta, they went beyond Colorado Springs to Pike's Peak. Next to Denver and Salt Lake City for an excursion into the Wasatch mountains. A journey of 29 hours took them to Reno

and Carson City, then Silver City

and ten days by wagon across the Sierra Nevada. Thus they came to the Yosemite and Calaveras Grove, and ended up in San Francisco. Hooker was back in Kew with 1,000 dried specimens by October.

Some idea of the delights he encountered (trivia from his journal & letters):

His views on the flora of Colorado and Utah: There are two temperate, and two cold or mountain floras, viz: 1. a prairie flora derived from the eastward; 2. a so-called desert and saline flora derived from the west; 3. a sub-alpine; 4. an alpine flora

, the two latter of widely different origin, and in one sense proper to the Rocky Mountain ranges.

His overview of North American flora contained these elements:

's Voyage of the Beagle

provided by Charles Lyell

and had been very impressed by Darwin's skill as a naturalist. They had met once, before the Antarctic voyage embarked. After Hooker's return to England, he was approached by Darwin who invited him to classify the plants that Darwin had collected in South America

and the Galápagos Islands

. Hooker agreed and the pair began a life-long friendship. On 11 January 1844 Darwin mentioned to Hooker his early ideas on the transmutation of species

and natural selection

, and Hooker showed interest. In 1847 he agreed to read Darwin's "Essay" explaining the theory, and responded with notes giving Darwin calm critical feedback. Their correspondence continued throughout the development of Darwin's theory

and in 1858 Darwin wrote that Hooker was "the one living soul from whom I have constantly received sympathy".

Richard Freeman wrote: "Hooker was Charles Darwin's greatest friend and confidant". Certainly they had extensive correspondence, and they also met face-to-face (Hooker visiting Darwin). Hooker and Lyell were the two people Darwin consulted (by letter) when Wallace's famous letter arrived at Down House, enclosing his paper on natural selection. Hooker was instrumental in creating the device whereby the Wallace paper was accompanied by Darwin's notes and his letter to Asa Gray

(showing his prior realization of natural selection) in a presentation to the Linnean Society. Hooker was the one who formally presented this material to the Linnean Society meeting in 1858. In 1859 the author of The Origin of Species

recorded his indebtedness to Hooker's wide knowledge and balanced judgment.

In December 1859, Hooker published the Introductory Essay to the Flora Tasmaniae, the final part of the Botany of the Antarctic Voyage. It was in this essay (which appeared just one month after the publication of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species), that Hooker announced his support for the theory of evolution by natural selection, thus becoming the first recognised man of science to publicly back Darwin.

At the historic debate on evolution

held at the Oxford University Museum

on 30 June 1860, Bishop Samuel Wilberforce

, Benjamin Brodie and Robert FitzRoy

spoke against Darwin's theory, and Hooker and Thomas Henry Huxley defended it. According to Hooker's own account, it was he and not Huxley who delivered the most effective reply to Wilberforce's arguments.

Hooker acted as president of the British Association

at its Norwich

meeting of 1868, when his address was remarkable for its championship of Darwinian theories. He was a close friend of Thomas Henry Huxley, a member of the X-Club (which dominated the Royal Society

in the 1870s and early 1880s), and the first of the three X-Clubbers in succession to become President of the Royal Society

. In 1862, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

.

By his travels and his publications, Hooker built up a high scientific reputation at home. In 1855 he was appointed Assistant-Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

By his travels and his publications, Hooker built up a high scientific reputation at home. In 1855 he was appointed Assistant-Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

, and in 1865 he succeeded his father as full Director, holding the post for twenty years. Under the directorship of father and son Hooker, the Royal Botanical gardens of Kew rose to world renown. At the age of thirty, Hooker was elected a fellow of the Royal Society

, and in 1873 he was chosen its President (till 1877). He received three of its medals: the Royal Medal

in 1854, the Copley

in 1887 and the Darwin Medal

in 1892. He continued to intersperse work at Kew with foreign exploration and collecting. His journeys to Palestine, Morocco and the United States all produced valuable information and specimens for Kew.

He started the series Flora Indica in 1855, together with Thomas Thompson

. Their botanical observations and the publication of the Rhododendrons of Sikkim-Himalaya (1849–51), formed the basis of elaborate works on the rhododendron

s of the Sikkim

Himalaya and on the flora of India. His works were illustrated with lithographs by Walter Hood Fitch

.

His greatest botanical work was the Flora of British India, published in seven volumes starting in 1872. On the publication of the last part in 1897, he was promoted Knight Grand Commander of the Star of India

, the highest rank of the Order (he had been made a Knight Commander of the Order of the Star of India in 1877). Ten years later, on attaining the age of ninety in 1907, he was awarded the Order of Merit

.

He was the author of numerous scientific papers and monographs, and his larger books included, in addition to those already mentioned, a standard Students Flora of the British Isles and a monumental work, the Genera plantarum (1860–83), based on the collections at Kew, in which he had the assistance of George Bentham

. His collaboration with George Bentham was especially important. Bentham, an amateur botanist who worked at Kew for many years, was perhaps the leading botanical systematist of the 19th century. The Handbook of the British flora, begun by Bentham and completed by Hooker, was the standard text for a hundred years. It was always known as 'Bentham & Hooker'.

In 1904, at the age of 87, Hooker published A sketch of the Vegetation of the Indian Empire. He continued the compilation of his father Sir William Jackson Hooker

's project, Icones Plantarum

(Illustrations of Plants), producing volumes eleven through nineteen.

at Kew was founded in 1853, and quickly grew in size and importance. At the time, Richard Owen

was the Superintendent of the natural history departments of the British Museum

, reporting only to the Head of the British Museum. Hooker, appointed in 1855 as Assistant Director of Kew, was the man most responsible for bringing foreign specimens to Kew.

The relationship between the two men continued to deteriorate after Hooker became a supporter of Darwin’s views and a member of the X-Club, who set out to get their way with the Royal Society. In 1868 Hooker had proposed that the whole of the huge herbarium collection of Joseph Banks

should be moved from the British Museum to Kew, a reasonable idea, but a threat to Owen's plans for a museum in South Kensigton to house the natural history collections. Hooker cited mismanagement at the British Museum as a justification.

After Joseph had succeeded his father as Director, in 1865, the independence of Kew was seriously threatened by the machinations of a Member of Parliament

, Acton Smee Ayrton

, whose appointment as First Commissioner of Works by Gladstone

in 1869 was greeted in The Times

with the prophecy that it would prove "another instance of Mr. Ayrton's unfortunate tendency to carry out what he thinks right in as unpleasant a manner as possible". This was relevant because Kew was funded by the Board of Works, and the Director of Kew reported to the First Commissioner. The conflict between the two men lasted from 1870 to 1872, and there is a voluminous correspondence on the Ayrton Episode held at Kew.

Ayrton behaved in an extraordinary way, interfering and approaching Hooker’s colleagues behind his back, apparently with the aim of getting Hooker to resign, when the expenditure on Kew could be curtailed and diverted. Ayrton actually took staff appointments out of Hooker's hands. He seemed not to value the scientific work, and to believe Kew should be just an amusement park.

Finally, Hooker asked to be put in communication with Gladstone’s private secretary, Algernon West

. A full statement was drawn up over the signatures of Darwin

, Lyell

, Huxley, Tyndall

, Bentham

and others. It was laid before Parliament by John Lubbock

, and additional papers laid before the House of Lords. Lord Derby

called for all the correspondence on the matter. The Treasury supported Hooker and criticised Ayrton’s behaviour.

One extraordinary fact emerged. There had been an official report on Kew which had not previously been seen in public. Ayrton had caused this to be written by Richard Owen. Hooker had not seen it, and so had not been given right of reply. However, the report was amongst the papers laid before Parliament, and it contained the most unscrupulous attack on both the Hookers, and suggested (amongst much else) that they had mismanaged the care of their trees, and that their systematic botany was nothing more than "attaching barbarous binomials to foreign weeds". The discovery of this report no doubt helped to sway opinion in favour of Hooker and Kew (there was debate in the press as well as Parliament). Hooker replied to the Owen report point by point in a factual manner, and his reply placed with the other papers on the case. When Ayrton was questioned about it in the debate led by Lubbock, he replied that “Hooker was too low an official to raise questions of matter with a Minister of the Crown”.

The outcome was not a vote in the Commons, but a kind of truce until, in August 1874, Gladstone transferred Ayrton from the Board of Works to the office of Judge Advocate-General, just before his government fell. Ayrton failed to get re-elected to Parliament. From that moment to this, the value of the Botanic Gardens has never been seriously questioned again. In the midst of his troubles, Hooker had been elected as President of the Royal Society in 1873. This showed publicly the high regard which Hooker's fellow scientists had for him

and the great importance they attached to his work.

Order of Merit

The Order of Merit is a British dynastic order recognising distinguished service in the armed forces, science, art, literature, or for the promotion of culture...

, GCSI

Order of the Star of India

The Most Exalted Order of the Star of India is an order of chivalry founded by Queen Victoria in 1861. The Order includes members of three classes:# Knight Grand Commander # Knight Commander # Companion...

, CB

Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate mediæval ceremony for creating a knight, which involved bathing as one of its elements. The knights so created were known as Knights of the Bath...

, MD

Doctor of Medicine

Doctor of Medicine is a doctoral degree for physicians. The degree is granted by medical schools...

, FRS (30 June 1817 – 10 December 1911) was one of the greatest British botanists and explorers of the 19th century. Hooker was a founder of geographical botany, and Charles Darwin's closest friend. He was Director of the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew, for twenty years, in succession to his father, William Jackson Hooker

William Jackson Hooker

Sir William Jackson Hooker, FRS was an English systematic botanist and organiser. He held the post of Regius Professor of Botany at Glasgow University, and was the first Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. He enjoyed the friendship and support of Sir Joseph Banks for his exploring,...

, and was awarded the highest honours of British science.

Early years

Hooker was born in HalesworthHalesworth

Halesworth is a small market town in the northeastern corner of Suffolk, England. It is located south west of Lowestoft, and straddles the River Blyth, 9 miles upstream from Southwold. The town is served by Halesworth railway station on the Ipswich-Lowestoft East Suffolk Line...

, Suffolk

Suffolk

Suffolk is a non-metropolitan county of historic origin in East Anglia, England. It has borders with Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south. The North Sea lies to the east...

, England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

. He was the second son of the famous botanist Sir William Jackson Hooker

William Jackson Hooker

Sir William Jackson Hooker, FRS was an English systematic botanist and organiser. He held the post of Regius Professor of Botany at Glasgow University, and was the first Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. He enjoyed the friendship and support of Sir Joseph Banks for his exploring,...

and Maria Sarah Turner, eldest daughter of the banker Dawson Turner

Dawson Turner

Dawson Turner was an English banker, botanist and antiquary.-Life:Turner was the son of James Turner, head of the Gurney and Turner's Yarmouth Bank and Elizabeth Cotman, the only daughter of the mayor of Yarmouth, John Cotman. He was educated at North Walsham Grammar School, Norfolk and at Barton...

and sister-in-law of Francis Palgrave

Francis Palgrave

Sir Francis Palgrave FRS, born Francis Ephraim Cohen, was an English historian.- Early life :He was born in London, the son of Meyer Cohen, a Jewish stockbroker by his wife Rachel Levien Cohen . He was initially articled as a clerk to a London solicitor's firm, and remained there as chief clerk...

. From age seven, Hooker attended his father's lectures at Glasgow University where he was Regius Professor of Botany

Regius Professor of Botany, Glasgow

University of GlasgowThe Regius Chair of Botany at Glasgow University is a Regius Professorship established in 1818.A lectureship in botany had been founded in 1704. From 1718 to 1818, the subject was combined with Anatomy...

. Joseph formed an early interest in plant distribution and the voyages of explorers like Captain James Cook

James Cook

Captain James Cook, FRS, RN was a British explorer, navigator and cartographer who ultimately rose to the rank of captain in the Royal Navy...

. He was educated at the Glasgow High School

High School of Glasgow

The High School of Glasgow is an independent, co-educational day school in Glasgow, Scotland. Founded as the Choir School of Glasgow Cathedral in around 1124, it is the oldest school in Scotland, and the twelfth oldest in the United Kingdom. It remained part of the Church as the city's grammar...

and went on to study medicine at Glasgow University, graduating M.D.

Doctor of Medicine

Doctor of Medicine is a doctoral degree for physicians. The degree is granted by medical schools...

in 1839. This degree qualified him for employment in the Naval Medical Service: he joined renowned polar explorer Captain James Clark Ross

James Clark Ross

Sir James Clark Ross , was a British naval officer and explorer. He explored the Arctic with his uncle Sir John Ross and Sir William Parry, and later led his own expedition to Antarctica.-Arctic explorer:...

's Antarctic

Antarctic

The Antarctic is the region around the Earth's South Pole, opposite the Arctic region around the North Pole. The Antarctic comprises the continent of Antarctica and the ice shelves, waters and island territories in the Southern Ocean situated south of the Antarctic Convergence...

expedition to the South Magnetic Pole after receiving a commission as Assistant-Surgeon on HMS Erebus.

Marriages and children

In 1851 he married Frances Harriet Henslow (1825–1874), daughter of John Stevens HenslowJohn Stevens Henslow

John Stevens Henslow was an English clergyman, botanist and geologist. He is best remembered as friend and mentor to his pupil Charles Darwin.- Early life :...

. They had four sons and three daughters:

- William Henslow Hooker (1853–1942)

- Harriet Anne HookerHarriet Anne Hooker Thiselton-DyerHarriet Anne Hooker Thiselton-Dyer was a British botanical illustrator. She studied with Walter Hood Fitch. After Fitch resigned from Curtis's Botanical Magazine, she rendered almost 100 illustrations for publication during the period 1878-1880, helping to keep the magazine viable...

(1854–1945) married William Turner Thiselton-DyerWilliam Turner Thiselton-DyerSir William Turner Thiselton-Dyer KCMG FRS FLS was a leading British botanist, and the third director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.- Life and career :Thiselton-Dyer was born in Westminster, London... - Charles Paget Hooker (1855–1933)

- Marie Elizabeth Hooker (1857–1863) died aged 6.

- Brian Harvey Hodgson Hooker (1860–1932)

- Reginald Hawthorn HookerReginald Hawthorn HookerReginald Hawthorn Hooker English civil servant, statistician and meteorologist. Hooker was a pioneer in the application of correlation analysis to economics and agricultural meteorology.- Biography :...

(1867–1944) statistician - Grace Ellen Hooker (1868–1955) Did not marry.

After his first wife's death in 1874, in 1876 he married Hyacinth Jardine (1842–1921), daughter of William Samuel Symonds

William Samuel Symonds

William Samuel Symonds , English geologist, was born in Hereford.He was educated at Cheltenham College and Christ's College, Cambridge, where he graduated BA in 1842. Having taken holy orders he was appointed curate of Offenham, near Evesham in 1843, and two years later he was presented to the...

and the widow of Sir William Jardine. They had two sons:

- Joseph Symonds Hooker (1877–1940)

- Richard Symonds Hooker (1885–1950).

Death and burial

Joseph Hooker died in his sleep at midnight at home (the Camp, Sunningdale) on 10 December 1911 after a short and apparently minor illness. The Dean and Chapter of Westminster AbbeyWestminster Abbey

The Collegiate Church of St Peter at Westminster, popularly known as Westminster Abbey, is a large, mainly Gothic church, in the City of Westminster, London, United Kingdom, located just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is the traditional place of coronation and burial site for English,...

offered a grave near Darwin's in the nave

Nave

In Romanesque and Gothic Christian abbey, cathedral basilica and church architecture, the nave is the central approach to the high altar, the main body of the church. "Nave" was probably suggested by the keel shape of its vaulting...

but also insisted that Hooker be cremated

Cremation

Cremation is the process of reducing bodies to basic chemical compounds such as gasses and bone fragments. This is accomplished through high-temperature burning, vaporization and oxidation....

before. His widow, Hyacinth, declined the proposal and eventually Hooker's body was buried, as he wished to be, alongside his father in the churchyard of St. Anne's Church, Kew

St. Anne's Church, Kew

St Anne's Church, Kew is the parish church of Kew, London, situated on Kew Green.-History:Originally built in 1714, on land given by Queen Anne as a church within the parish of Kingston, St. Anne's Church has been extended several times since, as the settlement of Kew grew with royal patronage. In...

, on Kew Green, within short distance of Kew Gardens.

Geological Survey of Great Britain

In 1845, Hooker applied for the Chair of Botany at the University of EdinburghUniversity of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh, founded in 1583, is a public research university located in Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland, and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The university is deeply embedded in the fabric of the city, with many of the buildings in the historic Old Town belonging to the university...

. This position included duties at the Royal Botanic Gardens of Scotland

Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh

The Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh is a scientific centre for the study of plants, their diversity and conservation, as well as a popular tourist attraction. Originally founded in 1670 as a physic garden to grow medicinal plants, today it occupies four sites across Scotland — Edinburgh,...

, and so the appointment was influenced by local politicians. An unusually protracted struggle ensued, resulting in the election of the locally born and bred botanist, John Hutton Balfour

John Hutton Balfour

John Hutton Balfour was a Scottish botanist. Balfour became a Professor of Botany, first at the University of Glasgow in 1841, moving to Edinburgh University and also becoming Regius Keeper of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh and Her Majesty's Botanist in Scotland in 1845...

. The Darwin correspondence

Correspondence of Charles Darwin

The British naturalist Charles Darwin had correspondence with numerous other luminaries of his age and members of his family. These have provided many insights about the nineteenth century, from scientific exploration and travel to religious debate and discussion...

, now public, makes clear Darwin's sense of shock at this unexpected outcome. Hooker declined a chair at Glasgow University which became vacant on Balfour's appointment. Instead, he took a position as botanist to the Geological Survey of Great Britain in 1846. He began work on palaeobotany, searching for fossil plants in the coal-beds of Wales

Wales

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and the island of Great Britain, bordered by England to its east and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population of three million, and a total area of 20,779 km²...

, eventually discovering the first coal ball

Coal ball

Coal balls, despite their name, are calcium-rich masses of permineralised life forms, generally having a round shape. Coal balls were formed roughly , during the Carboniferous Period...

in 1855. He became engaged to Frances Henslow, daughter of Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin FRS was an English naturalist. He established that all species of life have descended over time from common ancestry, and proposed the scientific theory that this branching pattern of evolution resulted from a process that he called natural selection.He published his theory...

's botany tutor John Stevens Henslow

John Stevens Henslow

John Stevens Henslow was an English clergyman, botanist and geologist. He is best remembered as friend and mentor to his pupil Charles Darwin.- Early life :...

, but he was keen to continue to travel and gain more experience in the field. He wanted to travel to India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

and the Himalayas

Himalayas

The Himalaya Range or Himalaya Mountains Sanskrit: Devanagari: हिमालय, literally "abode of snow"), usually called the Himalayas or Himalaya for short, is a mountain range in Asia, separating the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau...

. In 1847 his father nominated him to travel to India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

and collect plants for Kew

Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, usually referred to as Kew Gardens, is 121 hectares of gardens and botanical glasshouses between Richmond and Kew in southwest London, England. "The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew" and the brand name "Kew" are also used as umbrella terms for the institution that runs...

.

When Hooker returned to England, his father had been appointed director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, usually referred to as Kew Gardens, is 121 hectares of gardens and botanical glasshouses between Richmond and Kew in southwest London, England. "The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew" and the brand name "Kew" are also used as umbrella terms for the institution that runs...

, and so was now a prominent man of science. William Hooker, through his connections, secured an Admiralty grant of £1000 to defray the cost of plates for his son's Botany of the Antarctic Voyages, and an annual stipend of £200 for Joseph while he worked on the flora. Hooker's flora was also to include that collected on the voyages of Cook and Menzies held by the British Museum and collections made on the Beagle. The floras were illustrated by Walter Hood Fitch

Walter Hood Fitch

Walter Hood Fitch was a botanical illustrator, born in Glasgow, Scotland, who executed some 10,000 drawings for various publications...

(trained in botanical illustration by William Hooker), who would go on to become the most prolific Victorian botanical artist.

Hooker's collections from the voyage were described eventually in one of two volumes published as the Flora Antarctica (1844–47). In the Flora he wrote about island

Island

An island or isle is any piece of sub-continental land that is surrounded by water. Very small islands such as emergent land features on atolls can be called islets, cays or keys. An island in a river or lake may be called an eyot , or holm...

s and their role in plant geography: the work made Hooker's reputation as a systemist and plant geographer. His works on the voyage were completed with Flora Novae-Zelandiae (1851–53) and Flora Tasmaniae (1853–59).

Voyage to the Antarctic 1839–1843

The expedition consisted of two ships, HMS ErebusHMS Erebus (1826)

HMS Erebus was a Hecla-class bomb vessel designed by Sir Henry Peake and constructed by the Royal Navy in Pembroke dockyard, Wales in 1826. The vessel was named after the dark region in Hades of Greek mythology called Erebus...

and HMS Terror

HMS Terror (1813)

HMS Terror was a bomb vessel designed by Sir Henry Peake and constructed by the Royal Navy in the Davy shipyard in Topsham, Devon. The ship, variously listed as being of either 326 or 340 tons, carried two mortars, one and one .-War service:...

; it was the last major voyage of exploration made entirely under sail. Hooker was the youngest of the 128 man crew. He sailed on the Erebus and was assistant to Robert McCormick

Robert McCormick (explorer)

Robert McCormick was a British Royal Navy surgeon, explorer and naturalist.McCormick was born in Great Yarmouth, England...

, who in addition to being the ship's Surgeon was instructed to collect zoological and geological specimens. The ships sailed on 30 September 1839. Before journeying to Antarctica they visited Madeira

Madeira

Madeira is a Portuguese archipelago that lies between and , just under 400 km north of Tenerife, Canary Islands, in the north Atlantic Ocean and an outermost region of the European Union...

, Tenerife

Tenerife

Tenerife is the largest and most populous island of the seven Canary Islands, it is also the most populated island of Spain, with a land area of 2,034.38 km² and 906,854 inhabitants, 43% of the total population of the Canary Islands. About five million tourists visit Tenerife each year, the...

, Santiago

Santiago, Cape Verde

Santiago , or Santiagu in Cape Verdean Creole, is the largest island of Cape Verde, its most important agricultural centre and home to half the nation’s population. At the time of Darwin's voyage it was called St. Jago....

and Quail Island in the Cape Verde

Cape Verde

The Republic of Cape Verde is an island country, spanning an archipelago of 10 islands located in the central Atlantic Ocean, 570 kilometres off the coast of Western Africa...

archipelago, St Paul Rocks

Saint Peter and Paul Rocks

The Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago is a group of 15 small islets and rocks in the central equatorial Atlantic Ocean. It lies in the Intertropical Convergence Zone, a region of severe storms...

, Trinidade

Trindade and Martim Vaz

Trindade and Martim Vaz is an archipelago located about 1,200 kilometers east of Vitória in the Southern Atlantic Ocean, belonging to the State of Espírito Santo, Brazil. The archipelago has a total area of 10.4 km² and a population of 32...

east of Brazil, St Helena, and the Cape of Good Hope

Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula, South Africa.There is a misconception that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Africa, because it was once believed to be the dividing point between the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. In fact, the...

. Hooker made plant

Plant

Plants are living organisms belonging to the kingdom Plantae. Precise definitions of the kingdom vary, but as the term is used here, plants include familiar organisms such as trees, flowers, herbs, bushes, grasses, vines, ferns, mosses, and green algae. The group is also called green plants or...

collections at each location and while travelling drew these and specimens of algae

Algae

Algae are a large and diverse group of simple, typically autotrophic organisms, ranging from unicellular to multicellular forms, such as the giant kelps that grow to 65 meters in length. They are photosynthetic like plants, and "simple" because their tissues are not organized into the many...

and sea life pulled aboard using tow nets.

From the Cape they entered the southern ocean. Their first stop was the Crozet Islands

Crozet Islands

The Crozet Islands are a sub-antarctic archipelago of small islands in the southern Indian Ocean. They form one of the five administrative districts of the French Southern and Antarctic Lands.-Geography:...

where they set down on Possession Island to deliver coffee to sealers. They departed for the Kerguelen Islands

Kerguelen Islands

The Kerguelen Islands , also known as the Desolation Islands, are a group of islands in the southern Indian Ocean constituting the emerged part of the otherwise submerged Kerguelen Plateau. The islands, along with Adélie Land, the Crozet Islands and the Amsterdam and Saint Paul Islands are part of...

where they would spend several days. Hooker identified 18 flowering plants, 35 moss

Moss

Mosses are small, soft plants that are typically 1–10 cm tall, though some species are much larger. They commonly grow close together in clumps or mats in damp or shady locations. They do not have flowers or seeds, and their simple leaves cover the thin wiry stems...

es and liverwort

Marchantiophyta

The Marchantiophyta are a division of bryophyte plants commonly referred to as hepatics or liverworts. Like other bryophytes, they have a gametophyte-dominant life cycle, in which cells of the plant carry only a single set of genetic information....

s, 25 lichen

Lichen

Lichens are composite organisms consisting of a symbiotic organism composed of a fungus with a photosynthetic partner , usually either a green alga or cyanobacterium...

s and 51 algae, including some that were not described by surgeon William Anderson when James Cook had visited the islands in 1772. The expedition spent some time in Hobart

Hobart

Hobart is the state capital and most populous city of the Australian island state of Tasmania. Founded in 1804 as a penal colony,Hobart is Australia's second oldest capital city after Sydney. In 2009, the city had a greater area population of approximately 212,019. A resident of Hobart is known as...

, Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the original name used by most Europeans for the island of Tasmania, now part of Australia. The Dutch explorer Abel Tasman was the first European to land on the shores of Tasmania...

, and then moved on to the Auckland Islands

Auckland Islands

The Auckland Islands are an archipelago of the New Zealand Sub-Antarctic Islands and include Auckland Island, Adams Island, Enderby Island, Disappointment Island, Ewing Island, Rose Island, Dundas Island and Green Island, with a combined area of...

and Campbell Island

Campbell Island, New Zealand

Campbell Island is a remote, subantarctic island of New Zealand and the main island of the Campbell Island group. It covers of the group's , and is surrounded by numerous stacks, rocks and islets like Dent Island, Folly Island , Isle de Jeanette Marie, and Jacquemart Island, the latter being the...

, and onward to Antarctica to locate the South Magnetic Pole. After spending 5 months in the Antarctic they returned to resupply in Hobart, then went on to Sydney

Sydney

Sydney is the most populous city in Australia and the state capital of New South Wales. Sydney is located on Australia's south-east coast of the Tasman Sea. As of June 2010, the greater metropolitan area had an approximate population of 4.6 million people...

, and the Bay of Islands

Bay of Islands

The Bay of Islands is an area in the Northland Region of the North Island of New Zealand. Located 60 km north-west of Whangarei, it is close to the northern tip of the country....

in New Zealand

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

. They left New Zealand to return to Antarctica. After spending 138 days at sea, and a collision between the Erebus and Terror, they sailed to the Falkland Islands

Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands are an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean, located about from the coast of mainland South America. The archipelago consists of East Falkland, West Falkland and 776 lesser islands. The capital, Stanley, is on East Falkland...

, to Tierra del Fuego

Tierra del Fuego

Tierra del Fuego is an archipelago off the southernmost tip of the South American mainland, across the Strait of Magellan. The archipelago consists of a main island Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego divided between Chile and Argentina with an area of , and a group of smaller islands including Cape...

, back to the Falklands and onward to their third sortie into the Antarctic. They made a landing at Cockburn Island

Cockburn Island, Antarctica

Cockburn Island is a circular island in diameter, consisting of a high plateau with steep slopes surmounted on the northwest side by a pyramidal peak high, lying in the northeast entrance to Admiralty Sound, south of the northeast end of Antarctic Peninsula...

and after leaving the Antarctic, stopped at the Cape, St Helena and Ascension Island

Ascension Island

Ascension Island is an isolated volcanic island in the equatorial waters of the South Atlantic Ocean, around from the coast of Africa and from the coast of South America, which is roughly midway between the horn of South America and Africa...

. The ships arrived back in England on 4 September 1843; the voyage had been a success for Ross as it was the first to confirm the existence of the southern continent and chart much of its coastline.

Voyage to the Himalayas and India 1847–1851

Himalayas

The Himalaya Range or Himalaya Mountains Sanskrit: Devanagari: हिमालय, literally "abode of snow"), usually called the Himalayas or Himalaya for short, is a mountain range in Asia, separating the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau...

expedition; he would be the first European to collect plants in the Himalaya. He received free passage on HMS Sidon

HMS Sidon (1846)

HMS Sidon was a first-class paddle frigate designed by Sir Charles Napier: her name commemorated his attack on the port of Sidon in 1840 during the Syrian War. Her keel was laid down May 26, 1845 at Deptford Dockyard, and she was launched on May 26, 1846...

, to the Nile

Nile

The Nile is a major north-flowing river in North Africa, generally regarded as the longest river in the world. It is long. It runs through the ten countries of Sudan, South Sudan, Burundi, Rwanda, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania, Kenya, Ethiopia, Uganda and Egypt.The Nile has two major...

and then travelled overland to Suez

Suez

Suez is a seaport city in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez , near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal, having the same boundaries as Suez governorate. It has three harbors, Adabya, Ain Sokhna and Port Tawfiq, and extensive port facilities...

where he boarded a ship to India. He arrived in Calcutta

Kolkata

Kolkata , formerly known as Calcutta, is the capital of the Indian state of West Bengal. Located on the east bank of the Hooghly River, it was the commercial capital of East India...

on 12 January 1848, then travelled by elephant to Mirzapur

Mirzapur

Mirzapur is a city in the heart of North India, nearly 650 km between Delhi and Kolkata and also equidistant from Allahabad and Varanasi. Located in the state of Uttar Pradesh, Mirzapur has a population of a little over 205,264 and is renowned for its famous carpet and brassware industry...

, up the Ganges by boat to Siliguri

Siliguri

Siliguri is a city in the Indian state of West Bengal. It is located in the Siliguri Corridor or Chicken's Neck - a very narrow strip of land linking mainland India to its north-eastern states. It is also the transit point for air, road and rail traffic to the neighbouring countries of Nepal,...

and overland by pony to Darjeeling, arriving on 16 April 1848.

Hooker's expedition was based in Darjeeling where he stayed with naturalist Brian Houghton Hodgson

Brian Houghton Hodgson

Brian Houghton Hodgson was an early naturalist and ethnologist working in British India and Nepal where he was an English civil servant. He described many species, especially birds and mammals from the Himalayas, and several birds were named after him by others such as Edward Blyth...

. Through Hodgson he met British East India Company representative Archibald Campbell

Arthur Campbell (British East India Company)

Archibald Campbell of the Bengal Medical Service was the first superintendent of the sanitarium of Darjeeling town in India. Sources differ regarding his first name. While some say that the "A" in "Dr A...

who negotiated Hooker's admission to Sikkim

Sikkim

Sikkim is a landlocked Indian state nestled in the Himalayan mountains...

, which was finally approved in 1849 (He was to be briefly taken prisoner by the Raja of Sikkim). Meanwhile, Hooker wrote to Darwin relaying to him the habits of animals in India, and collected plants in Bengal

Bengal

Bengal is a historical and geographical region in the northeast region of the Indian Subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal. Today, it is mainly divided between the sovereign land of People's Republic of Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal, although some regions of the previous...

. He explored with local resident Charles Barnes, then travelled along the Great Runjeet river to its junction with the Tista River and Tonglu mountain in the Singalila range on the border with Nepal

Nepal

Nepal , officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal, is a landlocked sovereign state located in South Asia. It is located in the Himalayas and bordered to the north by the People's Republic of China, and to the south, east, and west by the Republic of India...

.

Kangchenjunga

Kangchenjunga is the third highest mountain of the world with an elevation of and located along the India-Nepal border in the Himalayas.Kangchenjunga is also the name of the section of the Himalayas and means "The Five Treasures of Snows", as it contains five peaks, four of them over...

, and north west along Nepal's passes into Tibet

Tibet

Tibet is a plateau region in Asia, north-east of the Himalayas. It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people as well as some other ethnic groups such as Monpas, Qiang, and Lhobas, and is now also inhabited by considerable numbers of Han and Hui people...

. In April 1849 he planned a longer expedition into Sikkim. Leaving on 3 May, he travelled north west up the Lachen Valley

Lachen River

Lachen River is a tributary of the Teesta River....

to the Kongra Lama Pass and then to the Lachoong Pass. Campbell and Hooker were imprisoned by the Dewan of Sikkim

Sikkim

Sikkim is a landlocked Indian state nestled in the Himalayan mountains...

when they were travelling towards the Chola Pass in Tibet

Tibet

Tibet is a plateau region in Asia, north-east of the Himalayas. It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people as well as some other ethnic groups such as Monpas, Qiang, and Lhobas, and is now also inhabited by considerable numbers of Han and Hui people...

. A British team was sent to negotiate with the king of Sikkim. However, they were released without any bloodshed and Hooker returned to Darjeeling where he spent January and February 1850 writing his journals, replacing specimens lost during his detention and planning a journey for his last year in India.

Reluctant to return to Sikkim, and unenthusiastic about travelling in Bhutan

Bhutan

Bhutan , officially the Kingdom of Bhutan, is a landlocked state in South Asia, located at the eastern end of the Himalayas and bordered to the south, east and west by the Republic of India and to the north by the People's Republic of China...

, he chose to make his last Himalayan expedition to Sylhet

Sylhet

Sylhet , is a major city in north-eastern Bangladesh. It is the main city of Sylhet Division and Sylhet District, and was granted metropolitan city status in March 2009. Sylhet is located on the banks of the Surma Valley and is surrounded by the Jaintia, Khasi and Tripura hills...

and the Khasi Hills

Khasi Hills

The Khasi Hills are part of the Garo-Khasi range in the Indian state of Meghalaya, and is part of the Patkai range and of the Meghalaya subtropical forests ecoregion...

in Assam

Assam

Assam , also, rarely, Assam Valley and formerly the Assam Province , is a northeastern state of India and is one of the most culturally and geographically distinct regions of the country...

. He was accompanied by Thomas Thomson, a fellow student from Glasgow University. They left Darjeeling on 1 May 1850, then sailed to the Bay of Bengal

Bay of Bengal

The Bay of Bengal , the largest bay in the world, forms the northeastern part of the Indian Ocean. It resembles a triangle in shape, and is bordered mostly by the Eastern Coast of India, southern coast of Bangladesh and Sri Lanka to the west and Burma and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands to the...

and travelled overland by elephant to the Khasi Hills and established a headquarters for their studies in Churra where they stayed until 9 December, when they began their trip back to England.

Hooker's survey of hitherto unexplored regions, the Himalayan Journals, dedicated to Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin FRS was an English naturalist. He established that all species of life have descended over time from common ancestry, and proposed the scientific theory that this branching pattern of evolution resulted from a process that he called natural selection.He published his theory...

, was published by the Calcutta Trigonometrical Survey

Great Trigonometric Survey

The Great Trigonometric Survey was a project of the Survey of India throughout most of the 19th century. It was piloted in its initial stages by William Lambton, and later by George Everest. Among the many accomplishments of the Survey were the demarcation of the British territories in India and...

Office in 1854, abbreviated again in 1855 and later by (The Minerva Library of Famous Books) Ward, Lock, Bowden & Co., 1891.

Voyage to Palestine 1860

This trip was taken in the autumn of 1860, with Daniel Hanbury. They visited and collected in Syria and Palestine; no full-length report was published, but a number of papers were written. Hooker recognised three phytogeograpical divisions: Western Syria and Palestine; Eastern Syria and Palestine; Middle and Upper mountain regions of Syria.Voyage to Morocco 1871

Hooker visited Morocco from April to June 1871, in the company of John Ball, George Maw and a young gardener from Kew, called Crump.Voyage to Western United States 1877

This was undertaken with his friend Asa GrayAsa Gray

-References:*Asa Gray. Dictionary of American Biography. American Council of Learned Societies, 1928–1936.*Asa Gray. Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2nd ed. 17 Vols. Gale Research, 1998.*Asa Gray. Plant Sciences. 4 vols. Macmillan Reference USA, 2001....

, the leading American botanist of the day. They wished to investigate the connection between the floras of eastern United States and those of eastern continental Asia and Japan; and the line of demarkation between Arctic floras of America and Greenland. As probable causes they considered the Glacial periods and an earlier land connection with an Arctic continent. "A difficult question was why in the great mountain chains of the Western United States there appeared to be only a few botanical enclaves of plants of eastern-Asiatic afinities among plants of Mexican and more southern types."

Hooker visited a number of cities and botanical institutions before moving west and climbing to 9,000 ft to camp at La Veta. From Fort Garland

Fort Garland

Fort Garland , Colorado, USA, was designed to house two companies of soldiers to protect settlers in the San Luis Valley, which was the Territory of New Mexico...

they climbed the Sierra Blanca

Sierra Blanca

Sierra Blanca is a range of volcanic mountains in Lincoln and Otero counties of south-central New Mexico. The range is about from north to south and wide, and is dominated by Sierra Blanca Peak, whose highest point is at...

at 14,500 ft. After returning to La Veta, they went beyond Colorado Springs to Pike's Peak. Next to Denver and Salt Lake City for an excursion into the Wasatch mountains. A journey of 29 hours took them to Reno

Reno

Reno is the fourth most populous city in Nevada, US.Reno may also refer to:-Places:Italy*The Reno River, in Northern ItalyCanada*Reno No...

and Carson City, then Silver City

Silver City

-Places:United States*Silver City, California*Silver City, Gulf County, Florida*Silver City, Idaho, a ghost town*Silver City, Iowa*Silver City, Michigan*Silver City, Mississippi*Silver City, New Mexico*Silver City, North Carolina*Silver City, Nevada...

and ten days by wagon across the Sierra Nevada. Thus they came to the Yosemite and Calaveras Grove, and ended up in San Francisco. Hooker was back in Kew with 1,000 dried specimens by October.

Some idea of the delights he encountered (trivia from his journal & letters):

- Hooker met and talked to Brigham YoungBrigham YoungBrigham Young was an American leader in the Latter Day Saint movement and a settler of the Western United States. He was the President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints from 1847 until his death in 1877, he founded Salt Lake City, and he served as the first governor of the Utah...

, whom he described as respectable and well-spoken. The new religion did not meet with Hooker's approval: "All the school children are brought up to believe in him [Brigham Young], and in a lot of scripture history as useless and idle as that taught in our schools."

- Of GeorgetownGeorgetown, Washington, D.C.Georgetown is a neighborhood located in northwest Washington, D.C., situated along the Potomac River. Founded in 1751, the port of Georgetown predated the establishment of the federal district and the City of Washington by 40 years...

: the "finger-tip of civilisation" where "the people sleep without locks to their doors, the fire-engines are well-manned and in capital order, and there is no end of food".

- "The New EnglandNew EnglandNew England is a region in the northeastern corner of the United States consisting of the six states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut...

ers are most like us in language, speech and habits... The Americans are great and promiscuous eaters... beds are remarkably clean and good, but the pillows are too soft."

His views on the flora of Colorado and Utah: There are two temperate, and two cold or mountain floras, viz: 1. a prairie flora derived from the eastward; 2. a so-called desert and saline flora derived from the west; 3. a sub-alpine; 4. an alpine flora

Alpine tundra

Alpine tundra is a natural region that does not contain trees because it is at high altitude. Alpine tundra is distinguished from arctic tundra, because alpine soils are generally better drained than arctic soils...

, the two latter of widely different origin, and in one sense proper to the Rocky Mountain ranges.

His overview of North American flora contained these elements:

- Polar area, from the Behring Strait to GreenlandGreenlandGreenland is an autonomous country within the Kingdom of Denmark, located between the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Though physiographically a part of the continent of North America, Greenland has been politically and culturally associated with Europe for...

. - British North American flora, south of the Arctic flora, in five meridional belts.

- United States flora, in belts:

- The Great Eastern Forest region, from the Atlantic to beyond the MississippiMississippiMississippi is a U.S. state located in the Southern United States. Jackson is the state capital and largest city. The name of the state derives from the Mississippi River, which flows along its western boundary, whose name comes from the Ojibwe word misi-ziibi...

. - The Prairie region.

- The Sink region, confined to gullies of the mountains.

- The Sierra Nevada.

- The Great Eastern Forest region, from the Atlantic to beyond the Mississippi

Darwin and evolution

While on the Erebus, Hooker had read proofs of Charles DarwinCharles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin FRS was an English naturalist. He established that all species of life have descended over time from common ancestry, and proposed the scientific theory that this branching pattern of evolution resulted from a process that he called natural selection.He published his theory...

's Voyage of the Beagle

The Voyage of the Beagle

The Voyage of the Beagle is a title commonly given to the book written by Charles Darwin and published in 1839 as his Journal and Remarks, bringing him considerable fame and respect...

provided by Charles Lyell

Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, Kt FRS was a British lawyer and the foremost geologist of his day. He is best known as the author of Principles of Geology, which popularised James Hutton's concepts of uniformitarianism – the idea that the earth was shaped by slow-moving forces still in operation...

and had been very impressed by Darwin's skill as a naturalist. They had met once, before the Antarctic voyage embarked. After Hooker's return to England, he was approached by Darwin who invited him to classify the plants that Darwin had collected in South America

South America

South America is a continent situated in the Western Hemisphere, mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere. The continent is also considered a subcontinent of the Americas. It is bordered on the west by the Pacific Ocean and on the north and east...

and the Galápagos Islands

Galápagos Islands

The Galápagos Islands are an archipelago of volcanic islands distributed around the equator in the Pacific Ocean, west of continental Ecuador, of which they are a part.The Galápagos Islands and its surrounding waters form an Ecuadorian province, a national park, and a...

. Hooker agreed and the pair began a life-long friendship. On 11 January 1844 Darwin mentioned to Hooker his early ideas on the transmutation of species

Transmutation of species

Transmutation of species was a term used by Jean Baptiste Lamarck in 1809 for his theory that described the altering of one species into another, and the term is often used to describe 19th century evolutionary ideas that preceded Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection...

and natural selection

Natural selection

Natural selection is the nonrandom process by which biologic traits become either more or less common in a population as a function of differential reproduction of their bearers. It is a key mechanism of evolution....

, and Hooker showed interest. In 1847 he agreed to read Darwin's "Essay" explaining the theory, and responded with notes giving Darwin calm critical feedback. Their correspondence continued throughout the development of Darwin's theory

Development of Darwin's theory

Following the inception of Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection in 1838, the development of Darwin's theory to explain the "mystery of mysteries" of how new species originated was his "prime hobby" in the background to his main occupation of publishing the scientific results of the Beagle...

and in 1858 Darwin wrote that Hooker was "the one living soul from whom I have constantly received sympathy".

Richard Freeman wrote: "Hooker was Charles Darwin's greatest friend and confidant". Certainly they had extensive correspondence, and they also met face-to-face (Hooker visiting Darwin). Hooker and Lyell were the two people Darwin consulted (by letter) when Wallace's famous letter arrived at Down House, enclosing his paper on natural selection. Hooker was instrumental in creating the device whereby the Wallace paper was accompanied by Darwin's notes and his letter to Asa Gray

Asa Gray

-References:*Asa Gray. Dictionary of American Biography. American Council of Learned Societies, 1928–1936.*Asa Gray. Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2nd ed. 17 Vols. Gale Research, 1998.*Asa Gray. Plant Sciences. 4 vols. Macmillan Reference USA, 2001....

(showing his prior realization of natural selection) in a presentation to the Linnean Society. Hooker was the one who formally presented this material to the Linnean Society meeting in 1858. In 1859 the author of The Origin of Species

The Origin of Species

Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species, published on 24 November 1859, is a work of scientific literature which is considered to be the foundation of evolutionary biology. Its full title was On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the...

recorded his indebtedness to Hooker's wide knowledge and balanced judgment.

In December 1859, Hooker published the Introductory Essay to the Flora Tasmaniae, the final part of the Botany of the Antarctic Voyage. It was in this essay (which appeared just one month after the publication of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species), that Hooker announced his support for the theory of evolution by natural selection, thus becoming the first recognised man of science to publicly back Darwin.

At the historic debate on evolution

1860 Oxford evolution debate

The 1860 Oxford evolution debate took place at the Oxford University Museum on 30 June 1860, seven months after the publication of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species. Several prominent British scientists and philosophers participated, including Thomas Henry Huxley, Bishop Samuel...

held at the Oxford University Museum

Oxford University Museum of Natural History

The Oxford University Museum of Natural History, sometimes known simply as the Oxford University Museum, is a museum displaying many of the University of Oxford's natural history specimens, located on Parks Road in Oxford, England. It also contains a lecture theatre which is used by the...

on 30 June 1860, Bishop Samuel Wilberforce

Samuel Wilberforce

Samuel Wilberforce was an English bishop in the Church of England, third son of William Wilberforce. Known as "Soapy Sam", Wilberforce was one of the greatest public speakers of his time and place...

, Benjamin Brodie and Robert FitzRoy

Robert FitzRoy

Vice-Admiral Robert FitzRoy RN achieved lasting fame as the captain of HMS Beagle during Charles Darwin's famous voyage, and as a pioneering meteorologist who made accurate weather forecasting a reality...

spoke against Darwin's theory, and Hooker and Thomas Henry Huxley defended it. According to Hooker's own account, it was he and not Huxley who delivered the most effective reply to Wilberforce's arguments.

Hooker acted as president of the British Association

British Association for the Advancement of Science

frame|right|"The BA" logoThe British Association for the Advancement of Science or the British Science Association, formerly known as the BA, is a learned society with the object of promoting science, directing general attention to scientific matters, and facilitating interaction between...

at its Norwich

Norwich

Norwich is a city in England. It is the regional administrative centre and county town of Norfolk. During the 11th century, Norwich was the largest city in England after London, and one of the most important places in the kingdom...

meeting of 1868, when his address was remarkable for its championship of Darwinian theories. He was a close friend of Thomas Henry Huxley, a member of the X-Club (which dominated the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

in the 1870s and early 1880s), and the first of the three X-Clubbers in succession to become President of the Royal Society

President of the Royal Society

The president of the Royal Society is the elected director of the Royal Society of London. After informal meetings at Gresham College, the Royal Society was founded officially on 15 July 1662 for the encouragement of ‘philosophical studies’, by a royal charter which nominated William Brouncker as...

. In 1862, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences or Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien is one of the Royal Academies of Sweden. The Academy is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization which acts to promote the sciences, primarily the natural sciences and mathematics.The Academy was founded on 2...

.

Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew

Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, usually referred to as Kew Gardens, is 121 hectares of gardens and botanical glasshouses between Richmond and Kew in southwest London, England. "The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew" and the brand name "Kew" are also used as umbrella terms for the institution that runs...

, and in 1865 he succeeded his father as full Director, holding the post for twenty years. Under the directorship of father and son Hooker, the Royal Botanical gardens of Kew rose to world renown. At the age of thirty, Hooker was elected a fellow of the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

, and in 1873 he was chosen its President (till 1877). He received three of its medals: the Royal Medal

Royal Medal

The Royal Medal, also known as The Queen's Medal, is a silver-gilt medal awarded each year by the Royal Society, two for "the most important contributions to the advancement of natural knowledge" and one for "distinguished contributions in the applied sciences" made within the Commonwealth of...

in 1854, the Copley

Copley Medal

The Copley Medal is an award given by the Royal Society of London for "outstanding achievements in research in any branch of science, and alternates between the physical sciences and the biological sciences"...

in 1887 and the Darwin Medal

Darwin Medal

The Darwin Medal is awarded by the Royal Society every alternate year for "work of acknowledged distinction in the broad area of biology in which Charles Darwin worked, notably in evolution, population biology, organismal biology and biological diversity". First awarded in 1890, it was created in...

in 1892. He continued to intersperse work at Kew with foreign exploration and collecting. His journeys to Palestine, Morocco and the United States all produced valuable information and specimens for Kew.

He started the series Flora Indica in 1855, together with Thomas Thompson

Thomas Thomson (1817-1878)

Thomas Thomson was a Scottish surgeon with the British East India Company before becoming a botanist. He was a friend of Joseph Dalton Hooker and helped write the first volume of Flora Indica....

. Their botanical observations and the publication of the Rhododendrons of Sikkim-Himalaya (1849–51), formed the basis of elaborate works on the rhododendron

Rhododendron

Rhododendron is a genus of over 1 000 species of woody plants in the heath family, most with showy flowers...

s of the Sikkim

Sikkim

Sikkim is a landlocked Indian state nestled in the Himalayan mountains...

Himalaya and on the flora of India. His works were illustrated with lithographs by Walter Hood Fitch

Walter Hood Fitch

Walter Hood Fitch was a botanical illustrator, born in Glasgow, Scotland, who executed some 10,000 drawings for various publications...

.

His greatest botanical work was the Flora of British India, published in seven volumes starting in 1872. On the publication of the last part in 1897, he was promoted Knight Grand Commander of the Star of India

Order of the Star of India

The Most Exalted Order of the Star of India is an order of chivalry founded by Queen Victoria in 1861. The Order includes members of three classes:# Knight Grand Commander # Knight Commander # Companion...

, the highest rank of the Order (he had been made a Knight Commander of the Order of the Star of India in 1877). Ten years later, on attaining the age of ninety in 1907, he was awarded the Order of Merit

Order of Merit

The Order of Merit is a British dynastic order recognising distinguished service in the armed forces, science, art, literature, or for the promotion of culture...

.

He was the author of numerous scientific papers and monographs, and his larger books included, in addition to those already mentioned, a standard Students Flora of the British Isles and a monumental work, the Genera plantarum (1860–83), based on the collections at Kew, in which he had the assistance of George Bentham

George Bentham

George Bentham CMG FRS was an English botanist, characterized by Duane Isely as "the premier systematic botanist of the nineteenth century".- Formative years :...

. His collaboration with George Bentham was especially important. Bentham, an amateur botanist who worked at Kew for many years, was perhaps the leading botanical systematist of the 19th century. The Handbook of the British flora, begun by Bentham and completed by Hooker, was the standard text for a hundred years. It was always known as 'Bentham & Hooker'.

In 1904, at the age of 87, Hooker published A sketch of the Vegetation of the Indian Empire. He continued the compilation of his father Sir William Jackson Hooker

William Jackson Hooker

Sir William Jackson Hooker, FRS was an English systematic botanist and organiser. He held the post of Regius Professor of Botany at Glasgow University, and was the first Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. He enjoyed the friendship and support of Sir Joseph Banks for his exploring,...

's project, Icones Plantarum

Icones Plantarum

Icones Plantarum is an extensive series of published volumes of botanical illustration, initiated by Sir William Jackson Hooker. The Latin name of the work means "Illustrations of Plants". The illustrations are drawn from herbarium specimens of Hooker's herbarium, and subsequently the herbarium of...

(Illustrations of Plants), producing volumes eleven through nineteen.

Attacks on Hooker and on Kew

The HerbariumHerbarium

In botany, a herbarium – sometimes known by the Anglicized term herbar – is a collection of preserved plant specimens. These specimens may be whole plants or plant parts: these will usually be in a dried form, mounted on a sheet, but depending upon the material may also be kept in...

at Kew was founded in 1853, and quickly grew in size and importance. At the time, Richard Owen

Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen, FRS KCB was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and palaeontologist.Owen is probably best remembered today for coining the word Dinosauria and for his outspoken opposition to Charles Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection...

was the Superintendent of the natural history departments of the British Museum

British Museum

The British Museum is a museum of human history and culture in London. Its collections, which number more than seven million objects, are amongst the largest and most comprehensive in the world and originate from all continents, illustrating and documenting the story of human culture from its...

, reporting only to the Head of the British Museum. Hooker, appointed in 1855 as Assistant Director of Kew, was the man most responsible for bringing foreign specimens to Kew.

- “There is no doubt that rivalry resulted between the British Museum, where there was the very important Herbarium of the Department of Botany, and Kew. The rivalry at times became extremely personal, especially between Joseph Hooker and Owen… At the root was Owen’s feeling that Kew should be subordinate to the British Museum (and to Owen) and should not be allowed to develop as an independent scientific institution with the advantage of a great botanic garden.”

The relationship between the two men continued to deteriorate after Hooker became a supporter of Darwin’s views and a member of the X-Club, who set out to get their way with the Royal Society. In 1868 Hooker had proposed that the whole of the huge herbarium collection of Joseph Banks

Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, GCB, PRS was an English naturalist, botanist and patron of the natural sciences. He took part in Captain James Cook's first great voyage . Banks is credited with the introduction to the Western world of eucalyptus, acacia, mimosa and the genus named after him,...

should be moved from the British Museum to Kew, a reasonable idea, but a threat to Owen's plans for a museum in South Kensigton to house the natural history collections. Hooker cited mismanagement at the British Museum as a justification.