Gregorian mission

Encyclopedia

Pope Gregory I

Pope Gregory I , better known in English as Gregory the Great, was pope from 3 September 590 until his death...

to the Anglo-Saxons

Anglo-Saxons

Anglo-Saxon is a term used by historians to designate the Germanic tribes who invaded and settled the south and east of Great Britain beginning in the early 5th century AD, and the period from their creation of the English nation to the Norman conquest. The Anglo-Saxon Era denotes the period of...

in 596 AD. Headed by Augustine of Canterbury

Augustine of Canterbury

Augustine of Canterbury was a Benedictine monk who became the first Archbishop of Canterbury in the year 597...

, its goal was to convert the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity. By the death of the last missionary in 653, they had established Christianity in southern Britain. Along with Irish

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

and Frankish

Franks

The Franks were a confederation of Germanic tribes first attested in the third century AD as living north and east of the Lower Rhine River. From the third to fifth centuries some Franks raided Roman territory while other Franks joined the Roman troops in Gaul. Only the Salian Franks formed a...

missionaries, they converted Britain and helped influence the Hiberno-Scottish mission

Hiberno-Scottish mission

The Hiberno-Scottish mission was a mission led by Irish and Scottish monks which spread Christianity and established monasteries in Great Britain and continental Europe during the Middle Ages...

aries on the Continent.

By the time the Roman Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

recalled its legions

Roman legion

A Roman legion normally indicates the basic ancient Roman army unit recruited specifically from Roman citizens. The organization of legions varied greatly over time but they were typically composed of perhaps 5,000 soldiers, divided into maniples and later into "cohorts"...

from the province of Britannia

Britannia

Britannia is an ancient term for Great Britain, and also a female personification of the island. The name is Latin, and derives from the Greek form Prettanike or Brettaniai, which originally designated a collection of islands with individual names, including Albion or Great Britain. However, by the...

in 410, parts of the island had already been settled by pagan Germanic tribes

Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples are an Indo-European ethno-linguistic group of Northern European origin, identified by their use of the Indo-European Germanic languages which diversified out of Proto-Germanic during the Pre-Roman Iron Age.Originating about 1800 BCE from the Corded Ware Culture on the North...

who, later in the century, appear to have taken control of Kent and other coastal regions. In the late 6th century Pope Gregory sent a group of missionaries to Kent

Kingdom of Kent

The Kingdom of Kent was a Jutish colony and later independent kingdom in what is now south east England. It was founded at an unknown date in the 5th century by Jutes, members of a Germanic people from continental Europe, some of whom settled in Britain after the withdrawal of the Romans...

, to convert Æthelberht, King of Kent, whose wife, Bertha of Kent

Bertha of Kent

Saint Bertha was the Queen of Kent whose influence led to the introduction of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England. She was canonized as a saint for her role in its establishment during that period of English history.Bertha was the daughter of Charibert I, Merovingian King of Paris...

, was a Frankish princess and practising Christian. Augustine was the prior

Prior

Prior is an ecclesiastical title, derived from the Latin adjective for 'earlier, first', with several notable uses.-Monastic superiors:A Prior is a monastic superior, usually lower in rank than an Abbot. In the Rule of St...

of Gregory's own monastery in Rome and Gregory prepared the way for the mission by soliciting aid from the Frankish rulers along Augustine's route.

In 597 the forty missionaries arrived in Kent and were permitted by Æthelberht to preach freely in his capital of Canterbury

Canterbury

Canterbury is a historic English cathedral city, which lies at the heart of the City of Canterbury, a district of Kent in South East England. It lies on the River Stour....

. Soon the missionaries were able to write to Gregory telling him of their success and that conversions were taking place. A second group of monks and clergy was dispatched in 601 bearing books and other items for the new foundation. The exact date of Æthelberht's conversion is unknown but it occurred before 601. Gregory intended Augustine to be the metropolitan

Metropolitan bishop

In Christian churches with episcopal polity, the rank of metropolitan bishop, or simply metropolitan, pertains to the diocesan bishop or archbishop of a metropolis; that is, the chief city of a historical Roman province, ecclesiastical province, or regional capital.Before the establishment of...

archbishop of the southern part of the British Isles, and gave him authority over the British clergy but in a series of meetings with Augustine the local bishops refused to acknowledge this.

Before Æthelberht's death in 616 a number of other bishoprics had been established but after that date, a pagan backlash set in and the see

Episcopal See

An episcopal see is, in the original sense, the official seat of a bishop. This seat, which is also referred to as the bishop's cathedra, is placed in the bishop's principal church, which is therefore called the bishop's cathedral...

, or bishopric, of London was abandoned. Æthelberht's daughter, Æthelburg, married Edwin

Edwin of Northumbria

Edwin , also known as Eadwine or Æduini, was the King of Deira and Bernicia – which later became known as Northumbria – from about 616 until his death. He converted to Christianity and was baptised in 627; after he fell at the Battle of Hatfield Chase, he was venerated as a saint.Edwin was the son...

, the king of the Northumbria

Northumbria

Northumbria was a medieval kingdom of the Angles, in what is now Northern England and South-East Scotland, becoming subsequently an earldom in a united Anglo-Saxon kingdom of England. The name reflects the approximate southern limit to the kingdom's territory, the Humber Estuary.Northumbria was...

ns, and by 627 Paulinus

Paulinus of York

Paulinus was a Roman missionary and the first Bishop of York. A member of the Gregorian mission sent in 601 by Pope Gregory I to Christianize the Anglo-Saxons from their native Anglo-Saxon paganism, Paulinus arrived in England by 604 with the second missionary group...

, the bishop who accompanied her north, had converted Edwin and a number of other Northumbrians. When Edwin died, in about 633, his widow and Paulinus were forced to flee to Kent. Although the missionaries were unable to remain in all of the places they had evangelised, by the time the last of them died in 653 they had established Christianity in Kent and the surrounding countryside and contributed a Roman tradition to the practice of Christianity in Britain.

Background

Pelagius

Pelagius was an ascetic who denied the need for divine aid in performing good works. For him, the only grace necessary was the declaration of the law; humans were not wounded by Adam's sin and were perfectly able to fulfill the law apart from any divine aid...

. Britain sent three bishops to the Synod of Arles

Synod of Arles

Arles in the south of Roman Gaul hosted several councils or synods referred to as Concilium Arelatense in the history of the early Christian church.-Council of Arles in 314:...

in 314, and a Gaulish

Gauls

The Gauls were a Celtic people living in Gaul, the region roughly corresponding to what is now France, Belgium, Switzerland and Northern Italy, from the Iron Age through the Roman period. They mostly spoke the Continental Celtic language called Gaulish....

bishop went to the island in 396 to help settle disciplinary matters. Material remains such as objects inscribed with Christian symbols and lead basins used for baptism testify to a growing Christian presence at least until about 360.

After the withdrawal of the Roman legions from Britannia in 410 the natives of the island of Great Britain

Great Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

were left to defend themselves. Angles

Angles

The Angles is a modern English term for a Germanic people who took their name from the ancestral cultural region of Angeln, a district located in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany...

, Saxons

Saxons

The Saxons were a confederation of Germanic tribes originating on the North German plain. The Saxons earliest known area of settlement is Northern Albingia, an area approximately that of modern Holstein...

, and Jutes

Jutes

The Jutes, Iuti, or Iutæ were a Germanic people who, according to Bede, were one of the three most powerful Germanic peoples of their time, the other two being the Saxons and the Angles...

, generally referred to colllectively as Anglo-Saxons, settled the southern parts of the island after the legions left, but most of Britain remained Christian. A series of distinct practices collectively referred to as Celtic Christianity

Celtic Christianity

Celtic Christianity or Insular Christianity refers broadly to certain features of Christianity that were common, or held to be common, across the Celtic-speaking world during the Early Middle Ages...

developed in isolation from Rome,. Characteristic of Celtic Christianity were its emphasis on monasteries instead of bishoprics, its calculation of the date of Easter

Easter

Easter is the central feast in the Christian liturgical year. According to the Canonical gospels, Jesus rose from the dead on the third day after his crucifixion. His resurrection is celebrated on Easter Day or Easter Sunday...

and the style of the tonsure

Tonsure

Tonsure is the traditional practice of Christian churches of cutting or shaving the hair from the scalp of clerics, monastics, and, in the Eastern Orthodox Church, all baptized members...

, or haircut, worn by its clerics. Evidence for the continued existence of Christianity in the eastern part of Britain during this time includes the survival of the cult of Saint Alban

Saint Alban

Saint Alban was the first British Christian martyr. Along with his fellow saints Julius and Aaron, Alban is one of three martyrs remembered from Roman Britain. Alban is listed in the Church of England calendar for 22 June and he continues to be venerated in the Anglican, Catholic, and Orthodox...

, and the occurrence of eccles—derived from the Latin for "church"—in place names. There is no evidence that these native Christians tried to convert the Anglo-Saxons.

The Anglo-Saxon invasions coincided with the disappearance of most remnants of Roman civilisation in the areas held by the Saxons and related tribes, including the economic and religious structures. Whether this was a result of the Angles themselves, as the early medieval writer Gildas

Gildas

Gildas was a 6th-century British cleric. He is one of the best-documented figures of the Christian church in the British Isles during this period. His renowned learning and literary style earned him the designation Gildas Sapiens...

argued, or mere coincidence is unclear. The archaeological evidence suggests much variation in the way that the tribes established themselves in Britain concurrently with the decline of urban Roman culture in Britain. The net effect was that when Augustine arrived in 597 the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms had little continuity with the preceding Roman civilisation. In the words of the historian John Blair, "Augustine of Canterbury began his mission with an almost clean slate."

Sources

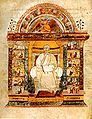

Most of the information available on the Gregorian mission comes from the medieval writer BedeBede

Bede , also referred to as Saint Bede or the Venerable Bede , was a monk at the Northumbrian monastery of Saint Peter at Monkwearmouth, today part of Sunderland, England, and of its companion monastery, Saint Paul's, in modern Jarrow , both in the Kingdom of Northumbria...

, especially his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum

Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum

The Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum is a work in Latin by Bede on the history of the Christian Churches in England, and of England generally; its main focus is on the conflict between Roman and Celtic Christianity.It is considered to be one of the most important original references on...

, or Ecclesiastical History of the English People. For this work Bede solicited help and information from many people including his contemporary abbot at Canterbury as well as a future Archbishop of Canterbury

Archbishop of Canterbury

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. In his role as head of the Anglican Communion, the archbishop leads the third largest group...

, Nothhelm, who forwarded Bede copies of papal letters and documents from Rome. Other sources are biographies of Pope Gregory, including one written in Northern England around 700 as well as a 9th-century life by a Roman writer. The early Life of Gregory is generally believed to have been based on oral traditions brought to northern England from either Canterbury or Rome, and was completed at Whitby Abbey

Whitby Abbey

Whitby Abbey is a ruined Benedictine abbey overlooking the North Sea on the East Cliff above Whitby in North Yorkshire, England. It was disestablished during the Dissolution of the Monasteries under the auspices of Henry VIII...

between 704 and 714. This view has been challenged by the historian Alan Thacker, who argues that the Life derives from earlier written works; Thacker suggests that much of the information it contains comes from a work written in Rome shortly after Gregory's death. Gregory's entry in the Liber Pontificalis

Liber Pontificalis

The Liber Pontificalis is a book of biographies of popes from Saint Peter until the 15th century. The original publication of the Liber Pontificalis stopped with Pope Adrian II or Pope Stephen V , but it was later supplemented in a different style until Pope Eugene IV and then Pope Pius II...

is short and of little use, but he himself was a writer whose work sheds light on the mission. In addition over 850 of Gregory's letters survive. A few later writings, such as letters from Boniface, an 8th-century Anglo-Saxon missionary, and royal letters to the papacy from the late 8th century, add additional detail. Some of these letters, however, are only preserved in Bede's work.

Bede represented the native British

Britons (historical)

The Britons were the Celtic people culturally dominating Great Britain from the Iron Age through the Early Middle Ages. They spoke the Insular Celtic language known as British or Brythonic...

church as wicked and sinful, in order to explain why Britain was conquered by the Anglo-Saxons: he drew on the polemic of Gildas and developed it further in his own works. Although he found some native British clergy worthy of praise he nevertheless condemned them for their failure to convert the invaders and for their resistance to Roman ecclesiastical authority. This bias may have resulted in his understating British missionary activity. Bede was from the north of England, and this may have led to a bias towards events near his own lands. Bede was writing over a hundred years after the events he was recording with little contemporary information on the actual conversion efforts. Nor did Bede completely divorce his account of the missionaries from his own early 8th-century concerns.

Although a few hagiographies

Hagiography

Hagiography is the study of saints.From the Greek and , it refers literally to writings on the subject of such holy people, and specifically to the biographies of saints and ecclesiastical leaders. The term hagiology, the study of hagiography, is also current in English, though less common...

, or saints' biographies, about native British saints survive from the period of the mission, none describes native Christians as active missionaries amongst the Anglo-Saxons. Most of the information about the British church at this time is concerned with the western regions of the island of Great Britain and does not deal with the Gregorian missionaries. Other sources of information include Bede's chronologies, the set of laws issued by Æthelberht in Kent, and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a collection of annals in Old English chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the Chronicle was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of Alfred the Great...

, which was compiled in the late 9th century.

Gregory the Great and his motivations

Immediate background

In 595, when Pope Gregory I decided to send a mission to the Anglo-Saxons, the Kingdom of Kent was ruled by Æthelberht. He had married a Christian princess named Bertha before 588, and perhaps earlier than 560. Bertha was the daughter of Charibert ICharibert I

Charibert I was the Merovingian King of Paris, the second-eldest son of Chlothar I and Ingund. His elder brother was Gunthar, who died sometime before their father's death....

, one of the Merovingian

Merovingian dynasty

The Merovingians were a Salian Frankish dynasty that came to rule the Franks in a region largely corresponding to ancient Gaul from the middle of the 5th century. Their politics involved frequent civil warfare among branches of the family...

kings of the Franks

Franks

The Franks were a confederation of Germanic tribes first attested in the third century AD as living north and east of the Lower Rhine River. From the third to fifth centuries some Franks raided Roman territory while other Franks joined the Roman troops in Gaul. Only the Salian Franks formed a...

. As one of the conditions of her marriage she had brought a bishop named Liudhard

Liudhard

Liudhard was a Frankish bishop – of where is unclear – and the chaplain of Queen Bertha of Kent, whom she brought with her from the continent upon her marriage to King Æthelberht of Kent...

with her to Kent as her chaplain. They restored a church in Canterbury that dated to Roman times, possibly the present-day St Martin's Church

St Martin's Church, Canterbury

The Church of St Martin in Canterbury, England, situated slightly beyond the city centre, is England's oldest parish church in continuous use. Since 1668 St Martin's has been part of the benefice of St Martin & St Paul Canterbury. Both St Martin's and nearby St Paul's churches are used for weekly...

. Æthelberht was at that time a pagan but he allowed his wife freedom of worship. Liudhard does not appear to have made many converts among the Anglo-Saxons, and if not for the discovery of a gold coin, the Liudhard medalet

Liudhard medalet

The Liudhard medalet is a gold Anglo-Saxon coin or small medal found some time before 1844 near St Martin's Church in Canterbury, England. It was part of the Canterbury-St Martin's hoard of six items. The coin, along with other items found with it, now resides in the World Museum Liverpool...

, bearing the inscription Leudardus Eps (Eps is an abbreviation of Episcopus, the Latin word for bishop) his existence may have been doubted. One of Bertha's biographers states that, influenced by his wife, Æthelberht requested Pope Gregory to send missionaries. The historian Ian Wood feels that the initiative came from the Kentish court as well as the queen.

Motivations

Most historians take the view that Gregory initiated the mission, although exactly why remains unclear. A famous story recorded by Bede, an 8th-century monk who wrote a history of the British Church, relates that Gregory saw fair-haired Saxon slaves from Britain in the Roman slave market and was inspired to try to convert their people. Supposedly Gregory inquired about the identity of the slaves, and was told that they were Angles from the island of Great Britain. Gregory replied that they were not Angles, but Angels. The earliest version of this story is from an anonymous Life of Gregory written at Whitby Abbey about 705. Bede, as well as the Whitby Life of Gregory, records that Gregory himself had attempted to go on a missionary journey to Britain before becoming pope. In 595 Gregory wrote to one of the papal estate managers in southern Gaul, asking that he buy English slave boys in order that they might be educated in monasteries. Some historians have seen this as a sign that Gregory was already planning the mission to Britain at that time, and that he intended to send the slaves as missionaries, although the letter is also open to other interpretations.The historian N. J. Higham speculates that Gregory had originally intended to send the British slave boys as missionaries, until in 596 he received news that Liudhard had died, thus opening the way for more serious missionary activity. Higham argues that it was the lack of any bishop in Britain which allowed Gregory to send Augustine, with orders to be consecrated as a bishop if needed. Another consideration was that cooperation would be more easily obtained from the Frankish royal courts if they no longer had their own bishop and agent in place.

Higham theorises that Gregory believed that the end of the world was imminent, and that he was destined to be a major part of God's plan for the apocalypse

Apocalypse

An Apocalypse is a disclosure of something hidden from the majority of mankind in an era dominated by falsehood and misconception, i.e. the veil to be lifted. The Apocalypse of John is the Book of Revelation, the last book of the New Testament...

. His belief was rooted in the idea that the world would go through six ages

Six Ages of the World

The Six Ages of the World is a Christian historical periodization first written about by Saint Augustine circa 400 AD. It is based upon Christian religious events, from the creation of Adam to the events of Revelation...

, and that he was living at the end of the sixth age, a notion that may have played a part in Gregory's decision to dispatch the mission. Gregory not only targeted the British with his missionary efforts, but he also supported other missionary endeavours, encouraging bishops and kings to work together for the conversion of non-Christians within their territories. He urged the conversion of the heretical Arians

Arianism

Arianism is the theological teaching attributed to Arius , a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt, concerning the relationship of the entities of the Trinity and the precise nature of the Son of God as being a subordinate entity to God the Father...

in Italy and elsewhere, as well as the conversion of Jews. Also pagans in Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica were the subject of letters to officials, urging their conversion.

Some scholars suggest that Gregory's main motivation was to increase the number of Christians; others wonder if more political matters such as extending the primacy of the papacy to additional provinces and the recruitment of new Christians looking to Rome for leadership were also involved. Such considerations may have also played a part, as influencing the emerging power of the Kentish Kingdom under Æthelberht could have had some bearing on the choice of location. Also, the mission may have been an outgrowth of the missionary efforts against the Lombards

Lombards

The Lombards , also referred to as Longobards, were a Germanic tribe of Scandinavian origin, who from 568 to 774 ruled a Kingdom in Italy...

. At the time of the mission Britain was the only part of the former Roman Empire which remained in pagan hands and the historian Eric John argues that Gregory desired to bring the last remaining pagan area of the old empire back under Christian control.

Practical considerations

The choice of Kent and Æthelberht was almost certainly dictated by a number of factors, including that Æthelberht had allowed his Christian wife to worship freely. Trade between the Franks and Æthelberht's kingdom was well established,and the language barrier between the two regions was apparently only a minor obstacle as the interpreters for the mission came from the Franks. Another reason for the mission was the growing power of the Kentish kingdom. Since the eclipse of King Ceawlin of WessexCeawlin of Wessex

Ceawlin was a King of Wessex. He may have been the son of Cynric of Wessex and the grandson of Cerdic of Wessex, whom the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle represents as the leader of the first group of Saxons to come to the land which later became Wessex...

in 592, Æthelberht was the leading Anglo-Saxon ruler; Bede refers to Æthelberht as having imperium

Imperium

Imperium is a Latin word which, in a broad sense, translates roughly as 'power to command'. In ancient Rome, different kinds of power or authority were distinguished by different terms. Imperium, referred to the sovereignty of the state over the individual...

, or overlordship, south of the River Humber

Humber

The Humber is a large tidal estuary on the east coast of Northern England. It is formed at Trent Falls, Faxfleet, by the confluence of the tidal River Ouse and the tidal River Trent. From here to the North Sea, it forms part of the boundary between the East Riding of Yorkshire on the north bank...

. Lastly, the proximity of Kent to the Franks allowed for support from a Christian area. There is some evidence, including Gregory's letters to Frankish kings in support of the mission, that some of the Franks felt they had a claim to overlordship over some of the southern British kingdoms at this time. The presence of a Frankish bishop could also have lent credence to claims of overlordship, if Liudhard was felt to be acting as a representative of the Frankish Church and not merely as a spiritual adviser to the queen. Archaeological remains support the notion that there were cultural influences from Francia in England at that time.

Preparations

In 595, Gregory chose Augustine, prior of Gregory's own Abbey of St Anthony in Rome, to head the mission to Kent. Gregory selected monks to accompany Augustine and sought support from the Frankish kings. The pope wrote to a number of Frankish bishops on Augustine's behalf, introducing the mission and asking that Augustine and his companions be made welcome. Copies of letters to some of these bishops survive in Rome. The pope wrote to King Theuderic IITheuderic II

Theuderic II , king of Burgundy and Austrasia , was the second son of Childebert II...

of Burgundy

Kingdom of Burgundy

Burgundy is a historic region in Western Europe that has existed as a political entity in a number of forms with very different boundaries. Two of these entities - the first around the 6th century, the second around the 11th century - have been called the Kingdom of Burgundy; a third was very...

and to King Theudebert II

Theudebert II

Theudebert II , King of Austrasia , was the son and heir of Childebert II. He received the kingdom of Austrasia plus the cities of Poitiers, Tours, Vellay, Bordeaux, and Châteaudun, as well as the Champagne, the Auvergne, and Transjurane Alemannia, on the death of his father in 595, but was...

of Austrasia

Austrasia

Austrasia formed the northeastern portion of the Kingdom of the Merovingian Franks, comprising parts of the territory of present-day eastern France, western Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. Metz served as its capital, although some Austrasian kings ruled from Rheims, Trier, and...

, as well as their grandmother Brunhilda of Austrasia

Brunhilda of Austrasia

Brunhilda was a Visigothic princess, married to king Sigebert I of Austrasia who ruled the eastern kingdoms of Austrasia and Burgundy in the names of her sons and grandsons...

, seeking aid for the mission. Gregory thanked King Chlothar II of Neustria

Neustria

The territory of Neustria or Neustrasia, meaning "new [western] land", originated in 511, made up of the regions from Aquitaine to the English Channel, approximating most of the north of present-day France, with Paris and Soissons as its main cities...

for aiding Augustine. Besides hospitality, the Frankish bishops and kings provided interpreters and were asked to allow some Frankish priests to accompany the mission. By soliciting help from the Frankish kings and bishops, Gregory helped to ensure a friendly reception for Augustine in Kent, as Æthelbert was unlikely to mistreat a mission which enjoyed the evident support of his wife's relatives and people. The Franks at that time were attempting to extend their influence in Kent, and assisting Augustine's mission furthered that goal. Chlothar, in particular, needed a friendly realm across the Channel to help guard his kingdom's flanks against his fellow Frankish kings.

Arrival and first efforts

Composition and arrival

The mission consisted of about forty missionaries, some of whom were monks. Soon after leaving Rome, the missionaries halted, daunted by the nature of the task before them. They sent Augustine back to Rome to request papal permission to return, which Gregory refused, and instead sending Augustine back with letters to encourage the missionaries to persevere. Another reason for the pause may have been the receipt of news of the death of King Childebert IIChildebert II

.Childebert II was the Merovingian king of Austrasia, which included Provence at the time, from 575 until his death in 595, the eldest and succeeding son of Sigebert I, and the king of Burgundy from 592 to his death, as the adopted and succeeding son of his uncle Guntram.-Childhood:When his father...

, who had been expected to help the missionaries; Augustine may have returned to Rome to secure new instructions and letters of introduction, as well as to update Gregory on the new political situation in Gaul. Most likely, they halted in the Rhone

Rhône

Rhone can refer to:* Rhone, one of the major rivers of Europe, running through Switzerland and France* Rhône Glacier, the source of the Rhone River and one of the primary contributors to Lake Geneva in the far eastern end of the canton of Valais in Switzerland...

valley. Gregory also took the opportunity to name Augustine as abbot of the mission. Augustine then returned to the rest of the missionaries, with new instructions, probably including orders to seek consecration as a bishop on the Continent if the conditions in Kent warranted it.

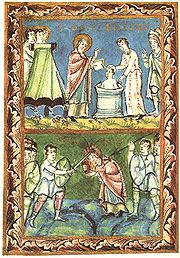

In 597 the mission landed in Kent, and it quickly achieved some initial success: Æthelberht permitted the missionaries to settle and preach in his capital of Canterbury, where they used the church of St. Martin's for services, and this church became the seat of the bishopric. Neither Bede nor Gregory mentions the date of Æthelberht's conversion, but it probably took place in 597.

Process of conversion

In the early medieval period, large-scale conversions required the ruler's conversion first, and large numbers of converts are recorded within a year of the mission's arrival in Kent. By 601, Gregory was writing to both Æthelberht and Bertha, calling the king his son and referring to his baptism. A late medieval tradition, recorded by the 15th-century chronicler Thomas ElmhamThomas Elmham

-Life:He was probably born at North Elmham in Norfolk. He may have been the Thomas Elmham who was a scholar at King's Hall, Cambridge from 1389 to 1394...

, gives the date of the king's conversion as Whit Sunday

Pentecost

Pentecost is a prominent feast in the calendar of Ancient Israel celebrating the giving of the Law on Sinai, and also later in the Christian liturgical year commemorating the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the disciples of Christ after the Resurrection of Jesus...

, or 2 June 597; there is no reason to doubt this date, but there is no other evidence for it. A letter of Gregory's to Patriarch Eulogius of Alexandria in June 598 mentions the number of converts made, but does not mention any baptism of the king in 597, although it is clear that by 601 he had been converted. The royal baptism probably took place at Canterbury but Bede does not mention the location.

Why Æthelberht chose to convert to Christianity is uncertain. Bede suggests that the king converted strictly for religious reasons, but most modern historians see other motives behind Æthelberht's decision. Certainly, given Kent's close contacts with Gaul, it is possible that Æthelberht sought baptism in order to smooth his relations with the Merovingian kingdoms, or to align himself with one of the factions then contending in Gaul. Another consideration may have been that new methods of administration often followed conversion, whether directly from the newly introduced church or indirectly from other Christian kingdoms.

Evidence from Bede suggests that, although Æthelberht encouraged conversion, he was unable to compel his subjects to become Christians. The historian R. A. Markus feels that this was due to a strong pagan presence in the kingdom that forced the king to rely on indirect means including royal patronage and friendship to secure conversions. For Markus this is demonstrated by the way in which Bede describes the king's conversion efforts which, when a subject converted, were to "rejoice at their conversion" and to "hold believers in greater affection".

Instructions and missionaries from Rome

After these conversions, Augustine sent Laurence back to Rome with a report of his success along with questions about the mission. Bede records the letter and Gregory's replies in chapter 27 of his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, this section of the History is usually known as the Libellus responsionumLibellus responsionum

The Libellus responsionum or Responsiones is a section of Bede's Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum that is a reply by Pope Gregory I to questions posed by Augustine of Canterbury about specifics of the Gregorian mission.-Creation:...

. Augustine asked for Gregory's advice on some issues, including how to organise the church, the punishment for church robbers, guidance on who was allowed to marry whom, and the consecration of bishops. Other topics were relations between the churches of Britain and Gaul, childbirth and baptism, and when it was lawful for people to receive communion and for a priest to celebrate mass. Other than the trip by Laurence, little is known of the activities of the missionaries in the period from their arrival until 601. Gregory mentions the mass conversions, and there is mention of Augustine working miracles that helped win converts, but there is little evidence of specific events.

According to Bede, further missionaries were sent from Rome in 601. They brought a pallium

Pallium

The pallium is an ecclesiastical vestment in the Roman Catholic Church, originally peculiar to the Pope, but for many centuries bestowed by him on metropolitans and primates as a symbol of the jurisdiction delegated to them by the Holy See. In that context it has always remained unambiguously...

for Augustine, gifts of sacred vessels, vestment

Vestment

Vestments are liturgical garments and articles associated primarily with the Christian religion, especially among Latin Rite and other Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, Anglicans, and Lutherans...

s, relic

Relic

In religion, a relic is a part of the body of a saint or a venerated person, or else another type of ancient religious object, carefully preserved for purposes of veneration or as a tangible memorial...

s, and books. The pallium was the symbol of metropolitan

Metropolitan bishop

In Christian churches with episcopal polity, the rank of metropolitan bishop, or simply metropolitan, pertains to the diocesan bishop or archbishop of a metropolis; that is, the chief city of a historical Roman province, ecclesiastical province, or regional capital.Before the establishment of...

status, and signified that Augustine was in union with the Roman papacy

Holy See

The Holy See is the episcopal jurisdiction of the Catholic Church in Rome, in which its Bishop is commonly known as the Pope. It is the preeminent episcopal see of the Catholic Church, forming the central government of the Church. As such, diplomatically, and in other spheres the Holy See acts and...

. Along with the pallium, a letter from Gregory directed the new archbishop to ordain twelve suffragan bishop

Suffragan bishop

A suffragan bishop is a bishop subordinate to a metropolitan bishop or diocesan bishop. He or she may be assigned to an area which does not have a cathedral of its own.-Anglican Communion:...

s as soon as possible, and to send a bishop to York

York

York is a walled city, situated at the confluence of the Rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. The city has a rich heritage and has provided the backdrop to major political events throughout much of its two millennia of existence...

. Gregory's plan was that there would be two metropolitan sees, one at York and one at London, with twelve suffragan bishops under each archbishop. Augustine was also instructed to transfer his archiepiscopal see to London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

from Canterbury, which never happened, perhaps because London was not part of Æthelberht's domain. Also, London remained a stronghold of paganism, as events after the death of Æthelberht revealed. London at that time was part of the Kingdom of Essex

Kingdom of Essex

The Kingdom of Essex or Kingdom of the East Saxons was one of the seven traditional kingdoms of the so-called Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy. It was founded in the 6th century and covered the territory later occupied by the counties of Essex, Hertfordshire, Middlesex and Kent. Kings of Essex were...

, which was ruled by Æthelberht's nephew Sæbert of Essex, who converted to Christianity in 604. The historian S. Brechter has suggested that the metropolitan see was indeed moved to London, and that it was only with the abandonment of London as a see after Æthelberht's death that Canterbury became the archiepiscopal see, contradicting Bede's version of events. The choice of London as Gregory's proposed southern archbishopric was probably was due to his understanding of how Britain was administered under the Romans, when London was the principal city of the province.

Along with the letter to Augustine, the returning missionaries brought a letter to Æthelberht that urged the king to act like the Roman Emperor Constantine I

Constantine I

Constantine the Great , also known as Constantine I or Saint Constantine, was Roman Emperor from 306 to 337. Well known for being the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity, Constantine and co-Emperor Licinius issued the Edict of Milan in 313, which proclaimed religious tolerance of all...

and force the conversion of his followers to Christianity. The king was also urged to destroy all pagan shrines. However, Gregory also wrote a letter to Mellitus

Mellitus

Mellitus was the first Bishop of London in the Saxon period, the third Archbishop of Canterbury, and a member of the Gregorian mission sent to England to convert the Anglo-Saxons from their native paganism to Christianity. He arrived in 601 AD with a group of clergymen sent to augment the mission,...

, the Epistola ad Mellitium of July 601, in which the pope took a different tack in regards to pagan shrines, suggesting that they be cleansed of idols and converted to Christian use rather than destroyed; the pope compared the Anglo-Saxons to the ancient Israelites, a recurring theme in Gregory's writings. He also suggested that the Anglo-Saxons build small huts much like those built during the Jewish festival of Sukkot

Sukkot

Sukkot is a Biblical holiday celebrated on the 15th day of the month of Tishrei . It is one of the three biblically mandated festivals Shalosh regalim on which Hebrews were commanded to make a pilgrimage to the Temple in Jerusalem.The holiday lasts seven days...

, to be used during the annual autumn slaughter festivals so as to gradually change the Anglo-Saxon pagan festivals into Christian ones.

The historian R. A. Markus suggests that the reason for the conflicting advice is that the letter to Æthelberht was written first, and sent off with the returning missionaries. Markus argues that the pope, after thinking further about the circumstances of the mission in Britain, then sent a follow-up letter, the Epistolae ad Mellitum, to Mellitus, then en route to Canterbury, which contained new instructions. Markus sees this as a turning point in missionary history, in that forcible conversion gave way to persuasion. This traditional view that the Epistola represents a contradiction of the letter to Æthelberht has been challenged by George Demacopoulos who argues that the letter to Æthelberht was mainly meant to encourage the king in spiritual matters, while the Epistola was sent to deal with purely practical matters, and thus the two do not contradict each other. Flora Spiegel, a writer on Anglo-Saxon literature

Anglo-Saxon literature

Old English literature encompasses literature written in Old English in Anglo-Saxon England, in the period from the 7th century to the Norman Conquest of 1066. These works include genres such as epic poetry, hagiography, sermons, Bible translations, legal works, chronicles, riddles, and others...

, suggests that the theme of comparing the Anglo-Saxons to the Israelites was part of a conversion strategy involving gradual steps, including an explicitly proto-Jewish one between paganism and Christianity. Spiegel sees this as an extension of Gregory's view of Judaism as halfway between Christianity and paganism. Thus, Gregory felt that first the Anglo-Saxons must be brought up to the equivalent of Jewish practices, then after that stage was reached they could be brought completely up to Christian practices.

Church building

Bede relates that after the mission's arrival in Kent and conversion of the king, they were allowed to restore and rebuild old Roman churches for their use. One such was Christ Church, Canterbury, which became Augustine's cathedral church. Archaeological evidence for other Roman churches having been rebuilt is slight, but the church of St Pancras in Canterbury has a Roman building at its core, although it is unclear whether that older building was a church during the Roman era. Another possible site is Lullingstone, in Kent, where a religious site dating to 300 was found underneath an abandoned church.Soon after his arrival, Augustine founded the monastery

Monastery

Monastery denotes the building, or complex of buildings, that houses a room reserved for prayer as well as the domestic quarters and workplace of monastics, whether monks or nuns, and whether living in community or alone .Monasteries may vary greatly in size – a small dwelling accommodating only...

of Saints Peter

Saint Peter

Saint Peter or Simon Peter was an early Christian leader, who is featured prominently in the New Testament Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles. The son of John or of Jonah and from the village of Bethsaida in the province of Galilee, his brother Andrew was also an apostle...

and Paul, which later became St Augustine's Abbey

St Augustine's Abbey

St Augustine's Abbey was a Benedictine abbey in Canterbury, Kent, England.-Early history:In 597 Saint Augustine arrived in England, having been sent by Pope Gregory I, on what might nowadays be called a revival mission. The King of Kent at this time was Æthelberht, who happened to be married to a...

, on land donated by the king. This foundation has often been claimed as the first Benedictine

Benedictine

Benedictine refers to the spirituality and consecrated life in accordance with the Rule of St Benedict, written by Benedict of Nursia in the sixth century for the cenobitic communities he founded in central Italy. The most notable of these is Monte Cassino, the first monastery founded by Benedict...

abbey outside Italy, and that by founding it Augustine introduced the Rule of St. Benedict into England, but there is no evidence that the abbey followed the Benedictine Rule at the time of its foundation.

Efforts in the south

Relations with the British Christians

Gregory had ordered that the native British bishops were to be governed by Augustine, and consequently Augustine arranged a meeting with some of the native clergy some time between 602 and 604. The meeting took place at a tree later given the name "Augustine's Oak", which by the time of Bede was on the border of the Kingdom of Kent, probably around the present-day boundary between SomersetSomerset

The ceremonial and non-metropolitan county of Somerset in South West England borders Bristol and Gloucestershire to the north, Wiltshire to the east, Dorset to the south-east, and Devon to the south-west. It is partly bounded to the north and west by the Bristol Channel and the estuary of the...

and Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire is a county in South West England. The county comprises part of the Cotswold Hills, part of the flat fertile valley of the River Severn, and the entire Forest of Dean....

. Augustine apparently argued that the British church should give up any of its customs not in accordance with Roman practices, including the dating of Easter

Easter controversy

The Easter controversy is a series of controversies about the proper date to celebrate the Christian holiday of Easter. To date, there are four distinct historical phases of the dispute and the dispute has yet to be resolved...

. He also urged them to help with the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons.

After some discussion, the local bishops stated that they needed to consult with their own people before agreeing to Augustine's requests, and left the meeting. Bede relates that a group of native bishops consulted an old hermit who said they should obey Augustine if, when they next met with him, Augustine rose when he greeted the natives. But if Augustine failed to stand up when they arrived for the second meeting, they should not submit. When Augustine failed to rise to greet the second delegation of British bishops at the next meeting, Bede says the native bishops refused to submit to Augustine. Bede then has Augustine proclaim a prophecy that because of lack of missionary effort towards the Anglo-Saxons from the British church, the native church would suffer at the hands of the Anglo-Saxons. This prophecy was seen as fulfilled when in 604 Æthelfrith of Northumbria supposedly killed 1200 native monks at the Battle of Chester

Battle of Chester

The Battle of Chester was a major victory for the Anglo Saxons over the native Britons near the city of Chester, England in the early 7th century. Æthelfrith of Northumbria annihilated a combined force from the Welsh kingdoms of Powys, Rhôs and possibly Mercia...

. Bede uses the story of Augustine's two meetings with two groups of British bishops as an example of how the native clergy refused to cooperate with the Gregorian mission. Later, Aldhelm, the abbot of Malmesbury

Malmesbury Abbey

Malmesbury Abbey, at Malmesbury in Wiltshire, England, was founded as a Benedictine monastery around 676 by the scholar-poet Aldhelm, a nephew of King Ine of Wessex. In 941 AD, King Athelstan was buried in the Abbey. By the 11th century it contained the second largest library in Europe and was...

, writing in the later part of the 7th century, claimed that the native clerks would not eat with the missionaries, nor would they perform Christian ceremonies with them. Laurence

Laurence of Canterbury

Laurence was the second Archbishop of Canterbury from about 604 to 619. He was a member of the Gregorian mission sent from Italy to England to Christianize the Anglo-Saxons from their native Anglo-Saxon paganism, although the date of his arrival is disputed...

, Augustine's successor, writing to the Irish bishops during his tenure of Canterbury, also stated that an Irish bishop, Dagan

Dagan (bishop)

Dagan was an Irish bishop in Britain during the early part of the 7th century.Dagan is known from a letter written by Archbishop Laurence of Canterbury to the Irish bishops and abbots, in which Laurence attempted to persuade the Irish clergy to accept the Roman method of calculating the date of...

, would not share meals with the missionaries.

One probable reason for the British clergy's refusal to cooperate with the Gregorian missionaries was the ongoing conflict between the natives and the Anglo-Saxons, who still were encroaching upon British lands at the time of the mission. The British were unwilling to preach to the invaders of their country, and the invaders saw the natives as second-class citizens, and would have been unwilling to listen to any conversion efforts. There was also a political dimension, as the missionaries were seen not as agents of the invaders; because Augustine was protected by Æthelberht, submitting to Augustine would have been seen as submitting to Æthelberht's authority, which the British bishops would have been unwilling to do.

Most of the information on the Gregorian mission comes from Bede's narrative, and this reliance on one source necessarily leaves the picture of native missionary efforts skewed. First, Bede's information is mainly from the north and the east of Britain. The western areas, where the native clergy was strongest, was an area little covered by Bede's informants. In addition, although Bede presents the native church as one entity, in reality the native British were divided into a number of small political units, which makes Bede's generalisations suspect. The historian Ian Wood argues that the existence of the Libellus points to more contact between Augustine and the native Christians because the topics covered in the work are not restricted to conversion from paganism, but also dealt with relations between differing styles of Christianity. Besides the text of the Libellus contained within Bede's work, other versions of the letter circulated, some of which included a question omitted from Bede's version. Wood argues that the question, which dealt with the cult of a native Christian saint, is only understandable if this cult impacted Augustine's mission, which would imply that Augustine had more relations with the local Christians than those related by Bede.

Spread of bishoprics and church affairs

In 604, another bishopric was founded, this time at RochesterDiocese of Rochester

The Diocese of Rochester is a Church of England diocese in South-East England and forms part of the Province of Canterbury. It is an ancient diocese, having been established in 604; only the neighbouring Diocese of Canterbury is older in the Church of England....

, where Justus

Justus

Justus was the fourth Archbishop of Canterbury. He was sent from Italy to England by Pope Gregory the Great, on a mission to Christianize the Anglo-Saxons from their native Anglo-Saxon paganism, probably arriving with the second group of missionaries despatched in 601...

was consecrated as bishop. The king of Essex was converted in the same year, allowing another see to be established at London

Diocese of London

The Anglican Diocese of London forms part of the Province of Canterbury in England.Historically the diocese covered a large area north of the Thames and bordered the dioceses of Norwich and Lincoln to the north and west. The present diocese covers and 17 London boroughs, covering most of Greater...

, with Mellitus as bishop. Rædwald, the king of the East Angles

Kingdom of the East Angles

The Kingdom of East Anglia, also known as the Kingdom of the East Angles , was a small independent Anglo-Saxon kingdom that comprised what are now the English counties of Norfolk and Suffolk and perhaps the eastern part of the Fens...

also was converted, but no see was established in his territory. Rædwald had been converted while visiting Æthelberht in Kent, but when he returned to his own court he worshiped pagan gods as well as the Christian God. Bede relates that Rædwald's backsliding was because of his still-pagan wife, but the historian S. D. Church sees political implications of overlordship behind the vacillation about conversion. When Augustine died in 604, Laurence, another missionary, succeeded him as archbishop.

The historian N. J. Higham suggests that a synod

Synod

A synod historically is a council of a church, usually convened to decide an issue of doctrine, administration or application. In modern usage, the word often refers to the governing body of a particular church, whether its members are meeting or not...

, or ecclesiastical conference to discuss church affairs and rules, was held at London during the early years of the mission, possibly shortly after 603. Boniface

Saint Boniface

Saint Boniface , the Apostle of the Germans, born Winfrid, Wynfrith, or Wynfryth in the kingdom of Wessex, probably at Crediton , was a missionary who propagated Christianity in the Frankish Empire during the 8th century. He is the patron saint of Germany and the first archbishop of Mainz...

, a Anglo-Saxon native who became a missionary to the continental Saxons, mentions such a synod being held at London. Boniface says that the synod legislated on marriage, which he discussed with Pope Gregory III

Pope Gregory III

Pope Saint Gregory III was pope from 731 to 741. A Syrian by birth, he succeeded Gregory II in March 731. His pontificate, like that of his predecessor, was disturbed by the iconoclastic controversy in the Byzantine Empire, in which he vainly invoked the intervention of Charles Martel.Elected by...

in 742. Higham argues that because Augustine had asked for clarifications on the subject of marriage from Gregory the Great, it is likely that he could have held a synod to deliberate on the issue. Nicholas Brooks, another historian, is not so sure that there was such a synod, but does not completely rule out the possibility. He suggests it might have been that Boniface was influenced by a recent reading of Bede's work.

The rise of Æthelfrith of Northumbria

Æthelfrith of Northumbria

Æthelfrith was King of Bernicia from c. 593 until c. 616; he was also, beginning c. 604, the first Bernician king to also rule Deira, to the south of Bernicia. Since Deira and Bernicia were the two basic components of what would later be defined as Northumbria, Æthelfrith can be considered, in...

in the north of Britain limited Æthelbertht's ability to expand his kingdom as well as limiting the spread of Christianity. Æthelfrith took over Deira

Deira

Deira was a kingdom in Northern England during the 6th century AD. Itextended from the Humber to the Tees, and from the sea to the western edge of the Vale of York...

about 604, adding it to his own realm of Bernicia

Bernicia

Bernicia was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom established by Anglian settlers of the 6th century in what is now southeastern Scotland and North East England....

. However, the Frankish kings in Gaul were increasingly involved in internal power struggles, leaving Æthelbertht free to continue to promote Christianity within his own lands. The Kentish Church sent Justus, then Bishop of Rochester, and Peter, the abbot of Sts Peter and Paul Abbey in Canterbury, to the Council of Paris

Edict of Paris

The Edict of Paris of Chlothar II, the Merovingian king of the Franks, promulgated October 18 614 , is one of the most important royal instruments of the Merovingian period in Frankish history and a hallmark in the history of the development of the Frankish monarchy...

in 614, probably with Æthelbertht's support. Æthelbertht also promulgated a code of laws, which was probably influenced by the missionaries.

Pagan reactions

A pagan reaction set in following Æthelbert's death in 616; Mellitus was expelled from London never to return, and Justus was expelled from Rochester, although he eventually managed to return after spending some time with Mellitus in Gaul. Bede relates a story that Laurence was preparing to join Mellitus and Justus in Francia when he had a dream in which Saint PeterSaint Peter

Saint Peter or Simon Peter was an early Christian leader, who is featured prominently in the New Testament Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles. The son of John or of Jonah and from the village of Bethsaida in the province of Galilee, his brother Andrew was also an apostle...

appeared and whipped Laurence as a rebuke for his plans to leave his mission. When Laurence woke whip marks had miraculously appeared on his body. He showed these to the new Kentish king, who promptly was converted and recalled the exiled bishops.

The historian N. J. Higham sees political factors at work in the expulsion of Mellitus, as it was Sæberht's sons who banished Mellitus. Bede said that the sons had never been converted, and after Æthelberht's death they attempted to force Mellitus to give them the Eucharist without ever becoming Christians, seeing the Eucharist as magical. Although Bede does not give details of any political factors surrounding the event, it is likely that by expelling Mellitus the sons were demonstrating their independence from Kent, and repudiating the overlordship that Æthelberht had exercised over the East Saxons. There is no evidence that Christians among the East Saxons were mistreated or oppressed after Mellitus' departure.

Æthelberht was succeeded in Kent by his son Eadbald

Eadbald of Kent

Eadbald was King of Kent from 616 until his death in 640. He was the son of King Æthelberht and his wife Bertha, a daughter of the Merovingian king Charibert. Æthelberht made Kent the dominant force in England during his reign and became the first Anglo-Saxon king to convert to Christianity from...

. Bede states that after Æthelberht's death Eadbald he refused to be baptised and married his stepmother, an act forbidden by the teachings of the Roman Church. Although Bede's account makes Laurence's miraculous flogging the trigger for Eadbald's baptism, this completely ignores the political and diplomatic problems facing Eadbald. There are also chronological problems with Bede's narrative, as surviving papal letters contradict Bede's account. Historians differ on the exact date of Eadbald's conversion. D. P. Kirby argues that papal letters imply that Eadbald was converted during the time that Justus was Archbishop of Canterbury, which was after Laurence's death, and long after the death of Æthelberht. Henry Mayr-Harting

Henry Mayr-Harting

Professor Henry Maria Robert Egmont Mayr-Harting was Regius Professor of Ecclesiastical History in the University of Oxford and Lay Canon of Christ Church, Oxford from 1997 until 2003....

accepts the Bedan chronology as correct, and feels that Eadbald was baptised soon after his father's death. Higham agrees with Kirby that Eadbald did not convert immediately, contending that the king supported Christianity but did not convert for at least eight years after his father's death.

Spread of Christianity to Northumbria

The spread of Christianity in the north of Britain gained ground when Edwin of NorthumbriaEdwin of Northumbria

Edwin , also known as Eadwine or Æduini, was the King of Deira and Bernicia – which later became known as Northumbria – from about 616 until his death. He converted to Christianity and was baptised in 627; after he fell at the Battle of Hatfield Chase, he was venerated as a saint.Edwin was the son...

married Æthelburg, a daughter of Æthelbert, and agreed to allow her to continue to worship as a Christian. He also agreed to allow Paulinus of York to accompany her as a bishop, and for Paulinus to preach to the court. By 627, Paulinus had converted Edwin, and on Easter, 627, Edwin was baptised. Many others were baptised after the king's conversion. The exact date when Paulinus went north is unclear; some historians argue for 625, the traditional date, whereas others believe that it was closer to 619. Higham argues that the marriage alliance was part of an attempt by Eadbald, brother of the bride, to capitalise on the death of Rædwald in about 624, in an attempt to regain the overkingship his father had once enjoyed. According to Higham, Rædwald's death also removed one of the political factors keeping Eadbald from converting, and Higham dates Eadbald's baptism to the time that his sister was sent to Northumbria. Although Bede's account gives all the initiative to Edwin, it is likely that Eadbald also was active in seeking such an alliance. Edwin's position in the north also was helped by the Rædwald's death, and Edwin seems to have held some authority over other kingdoms until his death.

Paulinus was active not only in Deira, which was Edwin's powerbase, but also in Bernicia and Lindsey

Kingdom of Lindsey

Lindsey or Linnuis is the name of a petty Anglo-Saxon kingdom, absorbed into Northumbria in the 7th century.It lay between the Humber and the Wash, forming its inland boundaries from the course of the Witham and Trent rivers , and the Foss Dyke between...

. Edwin planned to set up a northern archbishopric at York, following Gregory the Great's plan for two archdioceses in Britain. Both Edwin and Eadbald sent to Rome to request a pallium for Paulinus, which was sent in July 634. Many of the East Angles, whose king, Eorpwald

Eorpwald of East Anglia

Eorpwald; also Erpenwald or Earpwald, , succeeded his father Rædwald as ruler of the independent Kingdom of the East Angles...

appears to have converted to Christianity, were also converted by the missionaries. Following Edwin's death in battle, in either 633 or 634, Paulinus returned to Kent with Edwin's widow and daughter. Only one member of Paulinus' group stayed behind, James the Deacon

James the Deacon

James the Deacon was an Italian deacon who accompanied Paulinus of York on his mission to Northumbria. He was a member of the Gregorian mission which came to England to Christianize the Anglo-Saxons from their native Anglo-Saxon paganism, although when he arrived in England is unknown...

. After Justus' departure from Northumbria, a new king, Oswald

Oswald of Northumbria

Oswald was King of Northumbria from 634 until his death, and is now venerated as a Christian saint.Oswald was the son of Æthelfrith of Bernicia and came to rule after spending a period in exile; after defeating the British ruler Cadwallon ap Cadfan, Oswald brought the two Northumbrian kingdoms of...

, invited missionaries from the Irish monastery of Iona

Iona

Iona is a small island in the Inner Hebrides off the western coast of Scotland. It was a centre of Irish monasticism for four centuries and is today renowned for its tranquility and natural beauty. It is a popular tourist destination and a place for retreats...

, who worked to convert the kingdom.

About the time that Edwin died in 633, a member of the East Anglian royal family, Sigeberht

Sigeberht of East Anglia

Sigeberht of East Anglia , was a saint and a king of East Anglia, the Anglo-Saxon kingdom which today includes the English counties of Norfolk and Suffolk. He was the first English king to receive a Christian baptism and education before his succession and the first to abdicate in order to enter...

, returned to Britain after his conversion while in exile in Francia. He asked Honorius, one of the Gregorian missionaries who was then Archbishop of Canterbury, to send him a bishop, and Honorius sent Felix of Burgundy

Felix of Burgundy

Felix of Burgundy, also known as Felix of Dunwich , was a saint and the first bishop of the East Angles. He is widely credited as the man who introduced Christianity to the kingdom of East Anglia...

, who was already a consecrated bishop; Felix succeeded in converting the East Angles.

Other aspects

The Gregorian missionaries focused their efforts in areas where Roman settlement had been concentrated. It is possible that Gregory, when he sent the missionaries, was attempting to restore a form of Roman civilisation to England, modelling the church's organisation after that of the church in Francia at that time. Another aspect of the mission was how little of it was based on monasticism. One monastery was established at Canterbury, which later became St Augustine's Abbey, but although Augustine and some of his missionaries had been monks, they do not appear to have lived as monks at Canterbury. Instead, they lived more as secular clergySecular clergy

The term secular clergy refers to deacons and priests who are not monastics or members of a religious order.-Catholic Church:In the Catholic Church, the secular clergy are ministers, such as deacons and priests, who do not belong to a religious order...

serving a cathedral

Cathedral

A cathedral is a Christian church that contains the seat of a bishop...

church, and it appears likely that the sees established at Rochester and London were organised along similar lines. The Gaulish and Italian churches were organised around cities and the territories controlled by those cities. Pastoral services were centralised, and churches were built in the larger villages of the cities' territorial rule. The seat of the bishopric was established in the city and all churches belonged to the diocese, staffed by the bishop's clergy.

Most modern historians have noted how the Gregorian missionaries come across in Bede's account as colourless and boring, compared to the Irish missionaries in Northumbria, and this is related directly to the way Bede gathered his information. The historian Henry Mayr-Harting argues that in addition, most of the Gregorian missionaries were concerned with the Roman virtue of gravitas

Gravitas

Gravitas was one of the Roman virtues, along with pietas, dignitas and virtus. It may be translated variously as weight, seriousness, dignity, or importance, and connotes a certain substance or depth of personality.-See also:*Auctoritas...

, or personal dignity not given to emotional displays, and this would have limited the colourful stories available about them.

One reason for the mission's success was that it worked by example. Also important was Gregory's flexibility and willingness to allow the missionaries to adjust their liturgies and behaviour. Another reason was the willingness of Æthelberht to be baptised by a non-Frank. The king would have been wary of allowing the Frankish bishop Liudhard to convert him, as that might open Kent up to Frankish claims of overlordship. But being converted by an agent of the distant Roman pontiff was not only safer, it allowed the added prestige of accepting baptism from the central source of the Latin Church. As the Roman Church was considered part of the Roman Empire in Constantinople, this also would gain Æthelberht acknowledgement from the emperor. Other historians have attributed the success of the mission to the substantial resources Gregory invested in its success; he sent over forty missionaries in the first group, with more joining them later, a quite significant number.

Legacy

Deusdedit of Canterbury

Deusdedit , perhaps originally named Frithona, Frithuwine or Frithonas, was a medieval Archbishop of Canterbury, the first native-born holder of the see of Canterbury. By birth an Anglo-Saxon, he became archbishop in 655 and held the office for more than nine years until his death, probably from...

, a native Englishman.

Pagan practices

The missionaries were forced to proceed slowly, and were unable to do much about eliminating pagan practices, or destroying temples or other sacred sites, unlike the missionary efforts that had taken place in Gaul under St MartinMartin of Tours

Martin of Tours was a Bishop of Tours whose shrine became a famous stopping-point for pilgrims on the road to Santiago de Compostela. Around his name much legendary material accrued, and he has become one of the most familiar and recognizable Christian saints...

. There was little fighting or bloodshed during the mission. Paganism was still practised in Kent until the 630s, and it was not declared illegal until 640. Although Honorius sent Felix to the East Angles, it appears that most of the impetus for conversion came from the East Anglian king.

With the Gregorian missionaries, a third strand of Christian practice was added to the British Isles, to combine with the Gaulish and the Hiberno-British strands already present. Although it is often suggested that the Gregorian missionaries introduced the Rule of Saint Benedict into England, there is no supporting evidence. The early archbishops at Canterbury claimed supremacy over all the bishops in the British Isles, but their claim was not acknowledged by most of the rest of the bishops. The Gregorian missionaries appear to have played no part in the conversion of the West Saxon

Wessex

The Kingdom of Wessex or Kingdom of the West Saxons was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the West Saxons, in South West England, from the 6th century, until the emergence of a united English state in the 10th century, under the Wessex dynasty. It was to be an earldom after Canute the Great's conquest...

s, who were converted by a missionary sent directly by Pope Honorius I

Pope Honorius I

Pope Honorius I was pope from 625 to 638.Honorius, according to the Liber Pontificalis, came from Campania and was the son of the consul Petronius. He became pope on October 27, 625, two days after the death of his predecessor, Boniface V...

. Neither did they have much lasting influence in Northumbria, where after Edwin's death the conversion of the Northumbrians was achieved by missionaries from Iona, not Canterbury.

Papal aspects

An important by-product of the Gregorian mission was the close relationship it fostered between the Anglo-Saxon Church and the Roman Church. Although Gregory had intended for the southern archiepiscopal see to be located at London, that never happened. A later tradition, dating from 797, when an attempt was made to move the archbishopric from Canterbury to London by King Coenwulf of MerciaCoenwulf of Mercia

Coenwulf was King of Mercia from December 796 to 821. He was a descendant of a brother of King Penda, who had ruled Mercia in the middle of the 7th century. He succeeded Ecgfrith, the son of Offa; Ecgfrith only reigned for five months, with Coenwulf coming to the throne in the same year that Offa...

, stated that on the death of Augustine, the "wise men" of the Anglo-Saxons met and decided that the see should remain at Canterbury, for that was where Augustine had preached. The idea that an archbishop needed a pallium in order to exercise his archiepiscopal authority derives from the Gregorian mission, which established the custom at Canterbury from where it was spread to the Continent by later Anglo-Saxon missionaries such as Willibrord

Willibrord

__notoc__Willibrord was a Northumbrian missionary saint, known as the "Apostle to the Frisians" in the modern Netherlands...

and Boniface. The close ties between the Anglo-Saxon church and Rome were strengthened later in the 7th century when Theodore of Tarsus

Theodore of Tarsus

Theodore was the eighth Archbishop of Canterbury, best known for his reform of the English Church and establishment of a school in Canterbury....

was appointed to Canterbury by the papacy.

The mission was part of a movement by Gregory to turn away from the East, and look to the Western parts of the old Roman Empire. After Gregory, a number of his successors as pope continued in the same vein, and maintained papal support for the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons. The missionary efforts of Augustine and his companions, along with those of the Hiberno-Scottish mission

Hiberno-Scottish mission

The Hiberno-Scottish mission was a mission led by Irish and Scottish monks which spread Christianity and established monasteries in Great Britain and continental Europe during the Middle Ages...

aries, were the model for the later Anglo-Saxon mission

Anglo-Saxon mission

Anglo-Saxon missionaries were instrumental in the spread of Christianity in the Frankish Empire during the 8th century, continuing the work of Hiberno-Scottish missionaries which had been spreading Celtic Christianity across the Frankish Empire as well as in Scotland and Anglo-Saxon England itself...

aries to Germany. The historian R. A. Markus suggests that the Gregorian mission was a turning point in papal missionary strategy, marking the beginnings of a policy of persuasion rather than coercion.

Cults of the saints

Another effect of the mission was the promotion of the cult of Pope Gregory the Great by the Northumbrians amongst others; the first Life of Gregory is from Whitby Abbey in Northumbria. Gregory was not popular in Rome, and it was not until Bede's Ecclesisastical History began to circulate that Gregory's cult also took root there. Gregory, in Bede's work, is the driving force behind the Gregorian mission, and Augustine and the other missionaries are portrayed as depending on him for advice and help in their endeavours. Bede also gives a leading role in the conversion of Northumbria to Gregorian missionaries, especially in his Chronica Maiora, in which no mention is made of any Irish missionaries. By putting Gregory at the centre of the mission, even though he did not take part in it, Bede helped to spread the cult of Gregory, who not only became one of the major saints in Anglo-Saxon England, but continued to overshadow Augustine even in the afterlife; an Anglo-Saxon church council of 747 ordered that Augustine should always be mentioned in the liturgy right after Gregory.A number of the missionaries were considered saints, including Augustine, who became another cult figure; the monastery he founded in Canterbury was eventually rededicated to him. Honorius, James the Deacon, Justus, Lawrence, Mellitus, Paulinus, and Peter, were also considered saints, along with Æthelberht, of whom Bede said that he continued to protect his people even after death.

Art, architecture, and music

Psalter

A psalter is a volume containing the Book of Psalms, often with other devotional material bound in as well, such as a liturgical calendar and litany of the Saints. Until the later medieval emergence of the book of hours, psalters were the books most widely owned by wealthy lay persons and were...

as being associated with Augustine, which the antiquary John Leland saw it at the Dissolution of the Monasteries

Dissolution of the Monasteries

The Dissolution of the Monasteries, sometimes referred to as the Suppression of the Monasteries, was the set of administrative and legal processes between 1536 and 1541 by which Henry VIII disbanded monasteries, priories, convents and friaries in England, Wales and Ireland; appropriated their...

in the 1530s, but it has since disappeared.

Augustine built a church at his foundation of Sts Peter and Paul Abbey at Canterbury, later renamed St Augustine's Abbey. This church was destroyed after the Norman Conquest

Norman conquest of England

The Norman conquest of England began on 28 September 1066 with the invasion of England by William, Duke of Normandy. William became known as William the Conqueror after his victory at the Battle of Hastings on 14 October 1066, defeating King Harold II of England...

to make way for a new abbey church. The mission also established Augustine's cathedral at Canterbury, which became Christ Church Priory. This church has not survived, and it is unclear if the church that was destroyed in 1067 and described by the medieval writer Eadmer

Eadmer

Eadmer, or Edmer , was an English historian, theologian, and ecclesiastic. He is known for being a contemporary biographer of his contemporary archbishop and companion, Saint Anselm, in his Vita Anselmi, and for his Historia novorum in Anglia, which presents the public face of Anselm...

as Augustine's church, was built by Augustine. Another medieval chronicler, Florence of Worcester

John of Worcester

John of Worcester was an English monk and chronicler. He is usually held to be the author of the Chronicon ex chronicis.-Chronicon ex chronicis:...

, claimed that the priory was destroyed in 1011, and Eadmer himself had contradictory stories about the events of 1011, in one place claiming that the church was destroyed by fire and in another claiming only that it was looted. A cathedral was also established in Rochester; although the building was destroyed in 676, the bishopric continued in existence. Other church buildings were erected by the missionaries in London, York, and possibly Lincoln, although none of them survive.

The missionaries introduced a musical form of chant

Chant

Chant is the rhythmic speaking or singing of words or sounds, often primarily on one or two pitches called reciting tones. Chants may range from a simple melody involving a limited set of notes to highly complex musical structures Chant (from French chanter) is the rhythmic speaking or singing...

into Britain, similar to that used in Rome during the mass

Mass