Wilfrid

Encyclopedia

Wilfrid was an English bishop

and saint

. Born a Northumbria

n noble, he entered religious life as a teenager and studied at Lindisfarne

, at Canterbury, in Gaul

, and at Rome; he returned to Northumbria in about 660, and became the abbot of a newly founded monastery at Ripon

. In 664 Wilfrid acted as spokesman for the Roman "party" at the Council of Whitby

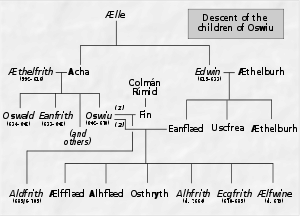

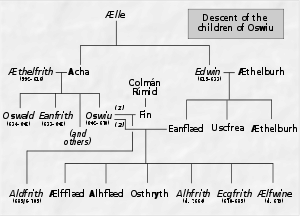

, and became famous for his speech advocating that the Roman method for calculating the date of Easter should be adopted. His success prompted the king's son, Alhfrith, to appoint him Bishop of Northumbria. Wilfrid chose to be consecrated in Gaul because of the lack of what he considered to be validly consecrated bishops in England at that time. During Wilfrid's absence Alhfrith seems to have led an unsuccessful revolt against his father, Oswiu

, leaving a question mark over Wilfrid's appointment as bishop. Before Wilfrid's return Oswiu had appointed Ceadda in his place, resulting in Wilfrid's retirement to Ripon for a few years following his arrival back in Northumbria.

After becoming Archbishop of Canterbury

in 668, Theodore of Tarsus

resolved the situation by deposing Ceadda and restoring Wilfrid as the Bishop of Northumbria. For the next nine years Wilfrid discharged his episcopal duties, founded monasteries, built churches, and improved the liturgy

. However his diocese

was very large, and Theodore wished to reform the English Church, a process which included breaking up some of the larger dioceses into smaller ones. When Wilfrid quarrelled with Ecgfrith, the Northumbrian king, Theodore took the opportunity to implement his reforms despite Wilfrid's objections. After Ecgfrith expelled him from York, Wilfrid travelled to Rome to appeal to the papacy. Pope Agatho

ruled in Wilfrid's favour, but Ecgfrith refused to honour the papal decree and instead imprisoned Wilfrid on his return to Northumbria before exiling him.

Wilfrid spent the next few years in Selsey

, where he founded an episcopal see

and converted the pagan inhabitants of the Kingdom of Sussex

to Christianity. Theodore and Wilfrid settled their differences, and Theodore urged the new Northumbrian king, Aldfrith

, to allow Wilfrid's return. Aldfrith agreed to do so, but in 691 he expelled Wilfrid again. Wilfrid went to Mercia, where he helped missionaries and acted as bishop for the Mercian king. Wilfrid appealed to the papacy about his expulsion in 700, and the pope ordered that an English council should be held to decide the issue. This council, held at Austerfield

in 702, attempted to confiscate all of Wilfrid's possessions, and so Wilfrid travelled to Rome to appeal against the decision. His opponents in Northumbria excommunicated him, but the papacy upheld Wilfrid's side, and he regained possession of Ripon and Hexham, his Northumbrian monasteries. Wilfrid died in 709 or 710. After his death, he was venerated as a saint.

Historians then and now have been divided over Wilfrid. His followers commissioned Stephen of Ripon to write a Vita Sancti Wilfrithi

(or Life of Wilfrid) shortly after his death, and the medieval historian Bede

also wrote extensively about him. Wilfrid lived ostentatiously, and travelled with a large retinue. He ruled a large number of monasteries, and claimed to be the first Englishman to introduce the Rule of Saint Benedict into English monasteries. Some modern historians see him mainly as a champion of Roman customs against the customs of the British and Irish churches

, others as an advocate for monasticism

.

During Wilfrid's lifetime the British Isles consisted of a number of small kingdoms. Traditionally the English people

were thought to have been divided into seven kingdoms, but modern historiography has shown that this is a simplification of a much more confused situation. A late 7th-century source, the Tribal Hidage

, lists the peoples south of the Humber river; among the largest groups of peoples are the West Saxons (later Wessex

), the East Angles

and Mercia

ns (later the Kingdom of Mercia), and the Kingdom of Kent

. Smaller groups who at that time had their own royalty but were later were absorbed into larger kingdoms include the peoples of Magonsæte, Lindsey, Hwicce

, the East Saxons

, the South Saxons, the Isle of Wight, and the Middle Angles

. Other even smaller groups had their own rulers, but their size means that they do not often appear in the histories. There were also native Britons in the west, in modern-day Wales

and Cornwall

, who formed kingdoms including those of Dumnonia

, Dyfed

, and Gwynedd

.

Between the Humber and Forth

the English had formed into two main kingdoms, Deira

and Bernicia, often united as the Kingdom of Northumbria. A number of Celtic kingdoms also existed in this region, including Craven

, Elmet

, Rheged

, and Gododdin

. A native British kingdom, later called the Kingdom of Strathclyde

, survived as an independent power into the 10th century in the area which became modern-day Dunbartonshire

and Clydesdale

. To the north-west of Strathclyde lay the Gaelic kingdom of Dál Riata

, and to the north-east a small number of Pictish kingdoms. Further north still lay the great Pictish kingdom of Fortriu

, which after the Battle of Dun Nechtain in 685 came to be the strongest power in the northern half of Britain. The Irish had always had contacts with the rest of the British Isles, and during the early 6th century they immigrated from the island of Ireland to form the kingdom of Dál Riata, although exactly how much conquest took place is a matter of dispute with historians. It also appears likely that the Irish settled in parts of Wales, and even after the period of Irish settlement, Irish missionaries were active in Britain.

Christianity had only recently arrived in some of these kingdoms. Some had been converted by the Gregorian mission

, a group of Roman missionaries who arrived in Kent in 597 and who mainly influenced southern Britain. Others had been converted by the Hiberno-Scottish mission, chiefly Irish missionaries working in Northumbria and neighbouring kingdoms. A few kingdoms, such as Dál Riata, became Christian but how they did so is unknown. The native Picts, according to the medieval writer Bede, were converted in two stages, initially by native Britons under Ninian

, and subsequently by Irish missionaries.

Bede also covers Wilfrid's life in his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum

, but this account is more measured and restrained than the Vita. In the Historia, Bede used Stephen's Vita as a source, reworking the information and adding new material when possible. Other, more minor, sources for Wilfrid's life include a mention of Wilfrid in one of Bede's letters. A poetical Vita Sancti Wilfrithi by Frithegod

written in the 10th century is essentially a rewrite of Stephen's Vita, produced in celebration of the movement of Wilfrid's relic

s to Canterbury. Wilfrid is also mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, but as the Chronicle was probably a 9th-century compilation, the material on Wilfrid may ultimately have derived either from Stephen's Vita or from Bede. Another, later, source is the Vita Sancti Wilfrithi written by Eadmer

, a 12th-century Anglo-Norman writer and monk from Canterbury. This source is higly influenced by the contemporary concerns of its writer, but does attempt to provide some new material besides reworking Bede.

Many historians, including the editor of Bede's works, Charles Plummer

, have seen in Bede's writings a dislike of Wilfrid. The historian Walter Goffart goes further, suggesting that Bede wrote his Historia as a reaction to Stephen's Vita Sancti Wilfrithi, and that Stephen's work was written as part of a propaganda campaign to defend a "Wilfridian" party in Northumbrian politics. Some historians, including James Fraser, find that a credible view, but others such as Nick Higham are less convinced of Bede's hostility to Wilfrid.

Queen Eanflæd became Wilfrid's patroness following his arrival at the court of her husband, King Oswiu. She sent him to study under Cudda, formerly one of her husband's retainers, but by that time in about 648 a monk on the island of Lindisfarne. The monastery on the island had recently been founded by Aidan

, who had been instrumental in converting Northumbria to Christianity. At Lindisfarne Wilfrid is said to have "learned the whole Psalter

by heart and several books". Wilfrid studied at Lindisfarne for a few years before going to the Kentish king's court at Canterbury

in 652, where he stayed with relatives of Queen Eanflæd. The queen had given Wilfrid a letter of introduction to pass to her cousin, King Eorcenberht

, in order to ensure that Wilfrid was received by the king. While in Kent, Wilfrid's career was advanced by Eanflæd's cousin Hlothere

, who was later the King of Kent from 673 to 685. The Kentish court included a number of visiting clergymen at that time, including Benedict Biscop

, a noted missionary. Wilfrid appears to have spent about a year in Kent, but the exact chronology is uncertain.

Wilfrid left Kent for Rome in the company of Benedict Biscop, another of Eanflæd's contacts. This is the first pilgrimage to Rome known to have been undertaken by English natives, and took place some time between 653 and 658. According to Wilfrid's later biographer, Stephen of Ripon, Wilfred left Biscop's company at Lyon

Wilfrid left Kent for Rome in the company of Benedict Biscop, another of Eanflæd's contacts. This is the first pilgrimage to Rome known to have been undertaken by English natives, and took place some time between 653 and 658. According to Wilfrid's later biographer, Stephen of Ripon, Wilfred left Biscop's company at Lyon

, where Wilfrid stayed under the patronage of Annemund

, the archbishop. Stephen says that Annemund wanted to marry Wilfrid to the archbishop's niece, and to make Wilfrid the governor of a Frankish province, but that Wilfrid refused and continued on his journey to Rome. There he learned the Roman method of calculating the date of Easter

, and studied the Roman practice of relic collecting. After an audience with the pope, Wilfrid returned to Lyon.

Stephen of Ripon says that Wilfrid stayed in Lyon for three years, leaving only after the archbishop's murder. However, Annemund's murder took place in 660 and Wilfrid returned to England in 658, suggesting that Stephen's chronology is awry. Stephen says that Annemund gave Wilfrid a clerical tonsure

, although this does not appear to mean that he became a monk, merely that he entered the clergy. Bede is silent on the subject of Wilfrid's monastic status, although Wilfrid probably became a monk during his time in Rome, or afterwards while he was in Gaul. Some historians, however, believe that Wilfrid was never a monk. While in Gaul, Wilfrid absorbed Frankish ecclesiastical practices, including some aspects from the monasteries founded by Columbanus

. This influence may be seen in Wilfrid's probable adoption of a Frankish ceremony in his consecration of churches later in his life, as well as in his employment of Frankish masons to build his churches. Wilfrid would also have learned of the Rule of Saint Benedict in Gaul, as Columbanus' monasteries followed that monastic rule.

, King of Wessex, recommended Wilfrid to Alhfrith, Oswiu's son, as a cleric well-versed in Roman customs and liturgy. Alhfrith was a sub-king of Deiria under his father's rule, and the most likely heir to his father's throne as his half-brothers were still young. Shortly before 664 Alhfrith gave Wilfrid a monastery he had recently founded at Ripon, formed around a group of monks from Melrose Abbey

, followers of the Irish monastic customs

. Wilfrid ejected the abbot, Eata, because he would not follow the Roman customs; Cuthbert, later a saint, was another of the monks expelled. Wilfrid introduced the Rule of Saint Benedict into Ripon, claiming that he was the first person in England to make a monastery follow it, but this claim rests on the Vita Sancti Wilfrithi and does not say where Wilfrid became knowledgeable about the Rule, nor exactly what form of the Rule was being referred to. Shortly afterwards Wilfrid was ordained a priest by Agilbert

, Bishop of Dorchester in the kingdom of the Gewisse, part of Wessex. Wilfrid was a protege of Agilbert, who later helped in Wilfrid's consecration as a bishop. The monk Ceolfrith was attracted to Ripon from Gilling Abbey

, which had recently been depopulated as a result of the plague. Ceolfrith later became Abbot of Wearmouth-Jarrow during the time the medieval chronicler and writer Bede was a monk there. Bede hardly mentions the relationship between Ceolfrith and Wilfrid, but it was Wilfrid who consecrated Ceolfrith a priest and who gave permission for him to transfer to Wearmouth-Jarrow.

, the second would be celebrating with feasting.

Oswiu called a church council held at Whitby Abbey

in 664 in an attempt to resolve this controversy

. Although Oswiu himself had been brought up in the "Celtic" tradition, political pressures may have influenced his decision to call a council, as well as fears that if dissent over the date of Easter continued in the Northumbrian church it could lead to internal strife. The historian Richard Abels speculates that the expulsion of Eata from Ripon may have been the spark that led to the king's decision to call the council. Regional tensions within Northumbria between the two traditional divisions, Bernicia

and Deira, appear to have played a part, as churchmen in Bernicia favoured the Celtic method of dating and those in Deira may have leaned towards the Roman method. Abels identifies several conflicts contributing to both the calling of the council and its outcome, including a generational conflict between Oswiu and Alhfrith and the death of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Deusdedit

. Political concerns unrelated to the dating problem, such as the decline of Oswiu's preeminence among the other English kingdoms and the challenge to that position by Mercia, were also factors.

, Agilbert, and Alhfrith. Those supporting the "Celtic" viewpoint were King Oswiu, Hilda, the Abbess of Whitby, Cedd

, a bishop, and Colmán of Lindisfarne

, the Bishop of Lindisfarne.

Wilfred was chosen to present the Roman position to the council; he also acted as Agilbert's interpreter, as the latter did not speak the local language. Bede describes Wilfrid as saying that those who did not calculate the date of Easter according to the Roman system were committing a sin. Wilfrid's speech in favour of adopting Roman church practices helped secure the eclipse of the "Celtic" party in 664, although most Irish churches did not adopt the Roman date of Easter until 704, and Iona

held out until 716. Many of the Irish monasteries did not observe the Roman Easter, but they were not isolated from the continent; by the time of Whitby the southern Irish were already observing the Roman Easter date, and Irish clergy were in contact with their continental counterparts. Those monks and clergy unable to accept the Whitby decision left Northumbria, some going to Ireland and others to Iona.

, and that he was a metropolitan bishop

, but York at that time was not a metropolitan diocese. Bede says that Alhfrith alone nominated Wilfrid, and that Oswiu subsequently proposed an alternative candidate, "imitating the actions of his son". Several theories have been suggested to explain the discrepancies between the two sources. One is that Alhfrith wished the seat to be at York, another is that Wilfrid was bishop only in Deira, a third supposes that Wilfrid was never bishop at York and that his diocese was only part of Deira. However, at that time the Anglo-Saxon dioceses were not strictly speaking geographical designations, rather they were bishoprics for the tribes or peoples.

Wilfrid refused to be consecrated in Northumbria at the hands of Anglo-Saxon bishops. Deusdedit had died shortly after Whitby, and as there were no other bishops in Britain whom Wilfrid considered to have been validly consecrated he travelled to Compiègne

, to be consecrated by Agilbert, the Bishop of Paris. During his time in Gaul Wilfrid was exposed to a higher level of ceremony than that practised in Northumbria, one example of which is that he was carried to his consecration ceremony on a throne supported by nine bishops.

, whether or not this was a Sunday. However, as the Irish church had never been Quartodecimans, Stephen in this instance was constructing a narrative to put Wilfrid in the best light.

During his return to Northumbria Wilfrid's ship was blown ashore on the Sussex coast, the inhabitants of which were at that time pagan. On being attacked by the locals, Wilfrid's party killed the head priest before refloating their ship and making their escape. The historian Marion Gibbs suggests that after this episode Wilfrid visited Kent

again, and took part in the diplomacy related to Wigheard

's appointment to the see of Canterbury. Wilfrid may also have taken part in negotiations to persuade King Cenwalh of Wessex to allow Agilbert to return to his see.

. The historian James Fraser argues that Wilfrid may not have been allowed to return to Northumbria and instead went into exile at the Mercian court, but most historians have argued that Wilfrid was at Ripon.

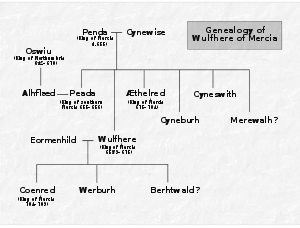

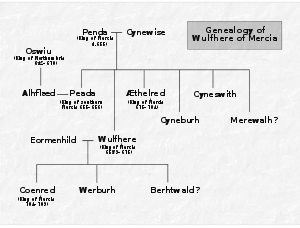

Wilfrid's monasteries in Mercia may date from this time, as King Wulfhere of Mercia

Wilfrid's monasteries in Mercia may date from this time, as King Wulfhere of Mercia

gave him large grants of land in Mercia. Wilfrid may have persuaded King Ecgberht of Kent

in 669 to build a church in an abandoned Roman fort at Reculver

. When Theodore, the newly appointed Archbishop of Canterbury, arrived in England in 669 it was clear that something had to be done about the situation in Northumbria. Ceadda's election to York was improper, and Theodore did not consider Ceadda's consecration to have been valid. Consequently Theodore deposed Ceadda, leaving the way open for Wilfrid, who was finally installed in his see in 669, the first Saxon to occupy the see of York. Wilfrid spent the next nine years building churches, including at the monastery at Hexham, and attending to diocesan business. He continued to exercise control over his monastic houses of Ripon and Hexham while he was bishop. Oswiu's death on 15 February 670 eliminated a source of friction and helped to assure Wilfrid's return.

While at York, Wilfrid was considered the "bishop of the Northumbrian peoples"; Bede records that Wilfrid's diocese was contiguous with the area ruled by Oswiu. The diocese was restricted to north of the Humber, however. Wilfrid may also have sought to exercise some ecclesiastical functions in the Pictish kingdom

, as he is accorded the title "bishop of the Northumbrians and the Picts" in 669. Further proof of attempted Northumbrian influence in the Pictish regions is provided by the establishment for the Picts in 681 of a diocese centred on Abercorn

, in the old territory of the British kingdom of Gododdin. The grants of land to Wilfrid west of the Pennines

testify to Northumbrian expansion in that area. The Vita Sancti Wilfrithi claims that Wilfrid had ecclesiastical rule over Britons and Gaels. In 679, while Wilfrid was in Rome, he claimed authority over "all the northern part of Britain, Ireland and the islands, which are inhabited by English and British peoples, as well as by Gaelic and Pictish peoples".

held in September 672, but he did send representatives. Among the council's resolutions was one postponing a decision on the creation of new dioceses, which affected Wilfrid later. Another ruling confirmed that the Roman calculation for the date of Easter should be adopted, and that bishops should act only in their own dioceses. During the middle 670s Wilfrid acted as middleman in the negotiations to return a Merovingian

prince, Dagobert II

, from his exile in Ireland to Gaul. Wilfrid was one of the first churchmen in Northumbria to utilise written charter

s as records of gifts to his churches. He ordered the creation of a listing of all benefactions received by Ripon, which was recited at the dedication ceremony.

Wilfrid was an advocate for the use of music in ecclesiastical ceremonies. He sent to Kent for a singing master to instruct his clergy in the Roman style of church music, which involved a double choir who sang in antiphon

s and responses. Bede says that this singing master was named Æddi (or Eddius in Latin) and had the surname Stephen. Traditionally historians have identified Æddi as Stephen of Ripon, author of the Vita Sancti Wilfrithi, which has led to the assumption that the Vita was based on the recollections of one of Wilfrid's long-time companions. However, recent scholarship has come to believe that the Vita was not authored by the singing master, but by someone who joined Wilfrid in the last years of Wilfrid's life, not a close companion.

Wilfrid introduced the Rule of Saint Benedict into the monasteries he founded. It appears likely that he was the first to introduce the Benedictine Rule into England, as evidence is lacking that Augustine

's monastery at Canterbury followed the Rule. He also was one of the first Anglo-Saxon bishops to record the gifts of land and property to his church, which he did at Ripon. Easter tables, used to calculate the correct date to celebrate Easter, were brought in from Rome where the Dionysiac Easter tables

had been recently introduced. He set up schools and became a religious advisor to the Northumbrian queen Æthelthryth

, first wife of Ecgfrith. Æthelthryth donated the land at Hexham

where Wilfrid founded a monastery and built a church using some recycled stones from the Roman town of Corbridge

. When Wilfrid arrived in York as bishop the cathedral's roof was on the point of collapse; he had it repaired and covered in lead, and had glass set in the windows.

The historian Barbara Yorke

says of Wilfrid at this time that he "seems to have continued a campaign against any survival of 'Irish errors' and distrusted any communities that remained in contact with Iona or other Irish religious houses which did not follow the Roman Easter". He also worked to combat pagan practices, building a church at Melrose on a pagan site. Contemporaries said of him that he was the first native bishop to "introduce the Catholic way of life to the churches of the English". He did not neglect his pastoral duties in his diocese, making visits throughout the diocese to baptise and perform other episcopal functions, such as consecrating new churches. Some of the monasteries in his diocese were put under his protection by their abbots or abbesses, who were seeking someone to help protect their endowments. In ruling over such monasteries, Wilfrid may have been influenced by the Irish model of a group of monasteries all ruled by one person, sometimes while holding episcopal office.

Wilfrid was criticised for dressing his household and servants in clothing fit for royalty. He was accompanied on his travels by a retinue of warriors, one of whom, while at York, Wilfrid sent to abduct a young boy who had been promised to the church but whose family had changed their mind. Wilfrid also educated young men, both for clerical and secular careers.

was a leader in a faction of the Northumbrian church that disliked Wilfrid, and her close ties with Theodore helped to undermine Wilfrid's position in Northumbria. Another contributory factor in Wilfrid's expulsion was his encouragement of Æthelthryth's entry into a nunnery; he had personally given her the veil, the ceremony of entering a nunnery, on her retirement to Ely Abbey. Æthelthryth had donated the lands Wilfrid used to found Hexham Abbey, and the historian N. J. Higham argues that they had been part of the queen's dower lands

, which, when Ecgfrith remarried, his new queen wanted to recover. The historian Eric John feels that Wilfrid's close ties with the Mercian kingdom also contributed to his troubles with Egfrith, although John points out that these ties were necessary for Wilfrid's monastic foundations, some of which were in Mercia. Wilfrid not only lost his diocese, he lost control of his monasteries as well.

Theodore took advantage of the situation to implement decrees of some councils on dividing up large dioceses. Theodore set up new bishoprics from Wilfrid's diocese, with seats at York

, Hexham, Lindisfarne, and one in the region of Lindsey

. The Lindsey see was quickly absorbed by the Diocese of Lichfield

, but the other three remained separate. The bishops chosen for these sees, Eata

at Hexham, Eadhæd at Lindsey, and Bosa at York, had all either been supporters of the "Celtic" party at Whitby, or been trained by those who were. Eata had also been ejected from Ripon by Wilfrid. The new bishops were unacceptable to Wilfrid, who claimed they were not truly members of the Church because of their support for the "Celtic" method of dating Easter, and thus he could not serve alongside them. Another possible problem for Wilfrid was that the three new bishops did not come from Wilfrid's monastic houses nor from the communities where the bishops' seats were based. This was contrary to the custom of the time, which was to promote bishoprics from within the locality. Wilfrid's deposition became tangled up in a dispute over whether or not the Gregorian plan for Britain, with two metropolitan sees, the northern one set at York, would be followed through or abandoned. Wilfrid seems to have felt that he had metropolitan authority over the northern part of England, but Theodore never acknowledged that claim, instead claiming authority over the whole of the island of Britain.

, the Frisian king in Utrecht

for most of 678. Wilfrid had been blown off course on his trip from England to the continent, and ended up in Frisia according to some historians. Others state that he intended to journey via Frisia to avoid Neustria

, whose mayor of the palace

, Ebroin

, disliked Wilfrid. He wintered in Frisia, avoiding the diplomatic efforts of Ebroin, who according to Stephen attempted to have Wilfrid killed. During his stay, Wilfrid attempted to convert the Frisians, who were still pagan at that time. Wilfrid's biographer says that most of the nobles converted, but the success was short-lived. After Frisia, he stopped at the court of Dagobert II in Austrasia, where the king offered Wilfrid the Bishopric of Strasbourg

, which Wilfrid refused. Once in Italy, Wilfrid was received by Perctarit

, a Lombard king, who gave him a place at his court.

Pope Agatho held a synod in October 679, which although it ordered Wilfrid's restoration and the return of the monasteries to his control, also directed that the new dioceses should be retained. Wilfrid was, however, given the right to replace any bishop in the new dioceses to whom he objected. The council had been called to deal with the Monothelete controversy

, and Wilfrid's concerns were not the sole focus of the council. In fact, the historian Henry Chadwick

thought that one reason Wilfrid secured the mostly favourable outcome was that Agatho wished for Wilfrid's support and testimony that the English Church was free of the monothelete heresy. Although Wilfrid did not win a complete victory, he did secure a papal decree limiting the number of dioceses in England to 12. Wilfrid also secured the right for his monasteries of Ripon and Hexham to be directly supervised by the pope, preventing any further interference in their affairs by the diocesan bishops.

Wilfrid returned to England after the council via Gaul. According to Stephen of Ripon, after the death of Dagobert II, Ebroin wished to imprison Wilfrid, but Wilfrid miraculously escaped. In 680 Wilfrid returned to Northumbria and appeared before a royal council. He produced the papal decree ordering his restoration, but was instead briefly imprisoned and then exiled by the king. Wilfrid stayed for a short time in the kingdom of the Middle Angles and at Wessex, but soon took refuge in Sussex with King Æthelwealh of Sussex.

Wilfrid spent the next five years preaching to, and converting the pagan inhabitants of Sussex, the South Saxons. He also founded Selsey Abbey

Wilfrid spent the next five years preaching to, and converting the pagan inhabitants of Sussex, the South Saxons. He also founded Selsey Abbey

, on an estate near Selsey of 87 hides

, given to Wilfrid by Æthelwealh, king of the South Saxons. Bede attributes Wilfrid's ability to convert the South Saxons to his teaching them how to fish, and contrasts it with the lack of success of the Irish monk Dicuill. Bede also says that the Sussex area had been experiencing a drought for three years before Wilfrid's arrival, but miraculously when Wilfrid arrived, and started baptising converts, rain began to fall. Wilfrid worked with Bishop Erkenwald of London, helping to set up the church in Sussex. Erkenwald also helped reconcile Wilfrid and Theodore before Theodore's death in 690. The mission was jeopardised when King Æthelwealh died during an invasion of his kingdom by Cædwalla of Wessex. Wilfrid previously had contact with Cædwalla, and may have served as his spiritual advisor before Cædwalla's invasion of Sussex. After Æthelwealh's death and Cædwalla's accession to the throne of Wessex, Wilfrid became one of the new king's advisors, and the king was converted. Cædwalla confirmed Æthelwealh's grant of land in the Selsey area and Wilfrid built his cathedral church

near the entrance to Pagham Harbour

believed to be what is now Church Norton.

Cædwalla sent Wilfrid to the Isle of Wight

, which was still pagan, with the aim of converting the inhabitants. The king also gave Wilfrid a quarter of the land on the island as a gift. In 688, the king relinquished his throne and went on a pilgrimage to Rome to be baptised, but died shortly after the ceremony. Wilfrid was probably influential in Cædwalla's decision to be baptised in Rome.

During his time in Sussex Wilfrid was reconciled with Archbishop Theodore; the Vita Sancti Wilfrithi says that Theodore expressed a desire for Wilfrid to succeed him at Canterbury. Wilfrid may have been involved in founding monasteries near Bath as well as in other parts of Sussex, but the evidence backing this is based on the wording used in the founding charters resembling wording used by Wilfrid in other charters, not on any concrete statements that Wilfrid was involved.

Wilfrid appears to have lived at Ripon, and for a time he acted as administrator of the see of Lindisfarne after Cuthbert's death in 687. In 691, the subdivision issue arose once more, along with quarrels with King Aldfrith over lands, and attempts were made to make Wilfrid either give up all his lands or to stay confined to Ripon. A proposal to turn Ripon into a bishopric was also a source of dispute. When no compromise was possible Wilfrid left Northumbria for Mercia, and Bosa was returned to York.

Something of the reception to Wilfrid's expulsion can be picked up in a Latin letter which has survived only in an incomplete quotation by William of Malmesbury

in his Gesta Pontificum. We have it on William's authority that the letter was written by Aldhelm of Malmesbury and addressed to Wilfrid's abbots. In it, Aldhelm asks the clergymen to remember the exiled bishop "who, nourishing, teaching, reproving, raised you in fatherly love" and appealing to lay aristocratic ideals of loyalty, urges them not to abandon their superior. Neither William nor the citation itself gives a date, but the letter has been assigned to Wilfrid's exile under Aldfrith in the 690s.

, which he had started in 678 during his stay in Frisia. Wilfrid helped the missionary efforts of Willibrord

, which were more successful than his own earlier attempts. Willibrord was a monk of Ripon who was also a native of Northumbria.

Wilfrid was present at the exhumation of the body of Queen Æthelthryth at Ely Abbey in 695. He had been her spiritual advisor in the 670s, and had helped the queen become a nun against the wishes of her husband King Ecgfrith of Northumbria

. The queen had joined Ely Abbey, where she died in 679. The ceremony in 695 found that her body had not decayed, which led to her being declared a saint. Wilfrid's testimony as to the character and virginity of Æthelthryth was recorded by Bede.

In about 700, Wilfrid appealed once more to Pope Sergius I

over his expulsion from York, and the pope referred the issue back to a council in England. In 702 King Aldfrith held a council

at Austerfield

that upheld Wilfrid's expulsion, and once more Wilfrid travelled to Rome to appeal to the pope. The Vita Sancti Wilfrithi gives a speech, supposedly delivered by Wilfrid there, in defence of Wilfrid's record over the previous 40 years. The council was presided over by Berhtwald, the new Archbishop of Canterbury, and the decision of the council was that Wilfrid should be deprived of all his monasteries but Ripon, and that he should cease to perform episcopal functions. When Wilfrid continued his appeal to the papacy, his opponents had him and his supporters excommunicated.

spoke Greek, and his biographer noted that Wilfrid was displeased when the pope discussed the appeal with advisers in a language Wilfrid could not understand. The pope also ordered another council to be held in Britain to decide the issue, and ordered the attendance of Bosa, Berhtwald and Wilfrid. On his journey back to England Wilfrid had a seizure at Meaux

, but he had returned to Kent by 705.

Aldfrith died soon after Wilfrid's arrival back in England. The new king, Eadwulf, had been considered one of Wilfrid's friends, but after his accession to the throne he ordered Wilfrid to stay out of Northumbria. Eadwulf's reign lasted only a few months however, before he was expelled to make way for Aldfrith's son Osred

, to whom Wilfrid acted as spiritual adviser. Wilfrid may have been one of Osred's chief supporters, along with Oswiu's daughter Abbess Ælfflæd of Whitby, and the nobleman Beornhæth

. Once Osred was secure on the throne Wilfrid was restored to Ripon and Hexham in 706. When Bosa of York died, however, Wilfrid did not contest the decision to appoint John of Beverley to York. This appointment meant John's transfer from Hexham, leaving Wilfrid free to perform episcopal functions at Hexham, which he did until his death.

to Bardney Abbey

by Osthryth

between 675 and 679, Wilfrid, along with Hexham Abbey, began to encourage and promote the cult of the dead king. Barbara Yorke sees this advocacy as a major factor in the prominence given to Oswald in Bede's Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum

. Historian D. P. Kirby regards Wilfrid's championing of Oswald as being a contributing factor in Wilfrid's expulsion from York in 678. Kirby believes that Ecgfrith felt Wilfrid was promoting Oswald's branch of the Northumbrian royal family over his own. One of Wilfrid's proteges, Willibrord, became a missionary to the Frisians in 695, perhaps inspired by Wilfrid's example. Willibrord may have felt it expedient to leave Northumbria, where he was known as one of Wilfrid's followers.

, Brixworth

, Evesham

, Wing

, and Withington

. At his monasteries and dioceses he built churches in a style akin to that of the continent and Rome, travelling between them with a large entourage of up to 120 followers. He made many contacts and friends, not only in Northumbria and the other English kingdoms, but also in Gaul, Frisia, and Italy. Nobles sent their sons to him for fostering

, and Wilfrid was known to help his proteges, no matter if they became clerics or not. The historian Peter Brown

speculated that one reason for Wilfrid's exile in 678 was that he was overshadowing the king as a patron. His contacts extended to the Lombard kingdom

in Italy, where they included King Perctarit and his son Cunipert

.

Wilfrid was a prolific founder of churches, which he then controlled until his death, and was a great fundraiser, acquiring lands and money from many of the kings he was in contact with. He was also noted for his ability to attract support from powerful women, especially queens. Queen Eanflæd, his first patron, introduced him to a number of helpful contacts, and he later attracted the support of Queen Æthelthryth, who gave the endowment for Hexham Abbey. Ælfflæd

, sister of King Aldfrith of Northumbria and daughter of Wilfrid's old patron Queen Eanflæd, helped to persuade the Northumbrians to allow Wilfrid to return from his last exile.

. The 12th-century writer Ailred of Rievaulx

, whose family helped restore Hexham, credited Wilfrid as the designer of a church beautifully embellished with paintings and sculpture. It appears that the churches at Hexham and Ripon (which Wilfrid also built) were aisled basilica

s, of the type that was common on the continent. Ripon was the first church in Northumbria to incorporate a porticus

, similar to those of churches in Kent. 12th-century pilgrims' accounts declared that the church at Hexham rivalled those of Rome. The crypts at both Ripon and Hexham are unusual, and perhaps were intended by Wilfrid to mimic the Roman catacombs

which he had seen on his travels. They are still extant, although the fabric of Wilfrid's churches above ground has been replaced by later structures. The churches were finished with glazed windows, made by glassmakers brought over from the continent.

As well as his building projects Wilfrid also commissioned works to embellish the churches, including altar cloths made of silk woven with gold threads, and a gospel book

written on parchment dyed purple

, with gold lettering. The gospels were then enclosed in a gold book cover set with gems. When the church he had built at Ripon was consecrated, a three-day feast was held to accompany the ceremony.

, where he lived until his death during a visit to Oundle, at the age of 75. A little over a year before his death in either 709 or 710 Wilfrid suffered another stroke or seizure, which led him to make arrangements for the disposition of his monasteries and possessions. He was buried near the altar of his church in Ripon. Bede records the epitaph that was placed on the tomb. Wilfrid was succeeded at Hexham by Acca of Hexham, a protege who had accompanied him to Rome in 703. The monastery at Ripon celebrated the first anniversary of Wilfrid's death with a commemoration service attended by all the abbots of his monasteries and a spectacular white arc was said to have appeared in the sky starting from the gables of the basilica where his bones were laid to rest.

Wilfrid left large sums of money to his monastic foundations, enabling them to purchase royal favour. Soon after his death a Vita Sancti Wilfrithi, was written by Stephen of Ripon, a monk of Ripon. The first version appeared in about 715 followed by a later revision in the 730s, the first biography written by a contemporary to appear in England. It was commissioned by two of Wilfrid's followers, Acca of Hexham, and the Abbot of Ripon, Tatbert. Stephen's Vita is concerned with vindicating Wilfrid and making a case for his sainthood, and so is used with caution by historians, although it is nevertheless an invaluable source for Wilfrid's life and the history of the time.

Wilfrid's feast day

Wilfrid's feast day

is 12 October or 24 April. Both dates were celebrated in early medieval England, but the April date appears first in the liturgical calendars. The April date is usually celebrated as his translation date, or the date when his relics were translated to a new shrine. Immediately after his death his body was venerated as a cult object, and miracles were alleged to have happened at the spot where the water used to wash his body was discarded. A cult grew up at Ripon after his death and remained active until 948, when King Eadred destroyed the church at Ripon; after the destruction, Wilfrid's relics were taken by Archbishop Oda of Canterbury, and held in Canterbury Cathedral

. This account appears in a foreword written by Oda for Frithegod

's later poem on Wilfrid's life. However, according to Byrhtferth

's Vita Sancti Oswaldi, or Life of Saint Oswald, Oda's nephew, Oswald, Archbishop of York

, preserved the relics at Ripon and restored the community there to care for them. The two differing accounts are not easily reconciled, but it is possible that Oswald collected secondary relics that had been overlooked by his uncle and installed those at Ripon. The relics that were held at Canterbury were originally placed in the High Altar in 948, but after the fire at Canterbury Cathedral in 1067, Wilfrid's relics were placed in their own shrine.

After the Norman Conquest of England

, devotion continued to be paid to Wilfrid, with 48 churches dedicated to him and relics distributed between 11 sites. During the 19th century, the feast of Wilfrid was celebrated on the Sunday following Lammas

in the town of Ripon with a parade and horse racing, a tradition which continued until at least 1908. He is venerated in the Roman Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox Church and the Anglican Communion. He is usually depiction either as a bishop preaching and baptizing or else as a robed bishop holding an episcopal staff.

Wilfrid was one of the first bishops to bring relics of saints back from Rome. The papacy was trying to prevent the removal of actual body parts from Rome, restricting collectors to things that had come in contact with the bodily remains such as dust and cloth. Wilfrid was known as an advocate of Benedictine monasticism, and regarded it as a tool in his efforts to "root out the poisonous weeds planted by the Scots". He built at Ripon and Hexham, and lived a majestic lifestyle. As a result of his various exiles, he founded monastic communities that were widely scattered over the British Isles, over which he kept control until his death. These monastic foundations, especially Hexham, contributed to the blending of the Gaelic and Roman strains of Christianity in Northumbria, which inspired a great surge of learning and missionary activity; Bede and Alcuin were among the scholars who emerged from Northumbrian monasteries influenced by Wilfrid. Missionaries inspired by his example went from Northumbria to the continent, where they converted pagans in Germany and elsewhere.

One commentator has said that Wilfrid "came into conflict with almost every prominent secular and ecclesiastical figure of the age". Hindley, a historian of the Anglo-Saxons, states that "Wilfrid would not win his sainthood through the Christian virtue of humility". The historian Barbara Yorke said of him that "Wilfrid's character was such that he seems to have been able to attract and infuriate in equal measure". His contemporary, Bede, although a partisan of the Roman dating of Easter, was a monk and always treats Wilfrid a little uneasily, showing some concern about how Wilfrid conducted himself as a clergyman and as a bishop. The historian Eric John feels that it was Wilfrid's devotion to monasticism that led him to believe that the only way for the Church to be improved was through monasticism. John traces Wilfrid's many appeals to Rome to his motivation to hold together his monastic empire, rather than to self-interest. John also challenges the belief that Wilfrid was fond of pomp, pointing out that the comparison between the Irish missionaries who walked and Wilfrid who rode ignores the reality that the quickest method of travel in the Middle Ages was on horseback.

The historian Peter Hunter Blair

summarises Wilfrid's life as follows: "Wilfrid left a distinctive mark on the character of the English church in the seventh century. He was not a humble man, nor, so far as we can see, was he a man greatly interested in learning, and perhaps he would have been more at home as a member of the Gallo-Roman episcopate where the wealth which gave him enemies in England would have passed unnoticed and where his interference in matters of state would have been less likely to take him to prison." R. W. Southern

, another modern historian, says that Wilfrid was "the greatest papal enthusiast of the century". James Campbell, a historian specialising in the Anglo-Saxon period, said of him "He was certainly one of the greatest ecclesiastics of his day. Ascetic, deemed a saint by some, the founder of several monasteries according to the rule of St Benedict, he established Christianity in Sussex and attempted to do so in Frisia. At the same time, his life and conduct were in some respects like those of a great Anglo-Saxon nobleman."

Bishop

A bishop is an ordained or consecrated member of the Christian clergy who is generally entrusted with a position of authority and oversight. Within the Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox Churches, in the Assyrian Church of the East, in the Independent Catholic Churches, and in the...

and saint

Saint

A saint is a holy person. In various religions, saints are people who are believed to have exceptional holiness.In Christian usage, "saint" refers to any believer who is "in Christ", and in whom Christ dwells, whether in heaven or in earth...

. Born a Northumbria

Northumbria

Northumbria was a medieval kingdom of the Angles, in what is now Northern England and South-East Scotland, becoming subsequently an earldom in a united Anglo-Saxon kingdom of England. The name reflects the approximate southern limit to the kingdom's territory, the Humber Estuary.Northumbria was...

n noble, he entered religious life as a teenager and studied at Lindisfarne

Lindisfarne

Lindisfarne is a tidal island off the north-east coast of England. It is also known as Holy Island and constitutes a civil parish in Northumberland...

, at Canterbury, in Gaul

Gaul

Gaul was a region of Western Europe during the Iron Age and Roman era, encompassing present day France, Luxembourg and Belgium, most of Switzerland, the western part of Northern Italy, as well as the parts of the Netherlands and Germany on the left bank of the Rhine. The Gauls were the speakers of...

, and at Rome; he returned to Northumbria in about 660, and became the abbot of a newly founded monastery at Ripon

Ripon

Ripon is a cathedral city, market town and successor parish in the Borough of Harrogate, North Yorkshire, England, located at the confluence of two streams of the River Ure in the form of the Laver and Skell. The city is noted for its main feature the Ripon Cathedral which is architecturally...

. In 664 Wilfrid acted as spokesman for the Roman "party" at the Council of Whitby

Synod of Whitby

The Synod of Whitby was a seventh century Northumbriansynod where King Oswiu of Northumbria ruled that his kingdom would calculate Easter and observe the monastic tonsure according to the customs of Rome, rather than the customs practised by Iona and its satellite institutions...

, and became famous for his speech advocating that the Roman method for calculating the date of Easter should be adopted. His success prompted the king's son, Alhfrith, to appoint him Bishop of Northumbria. Wilfrid chose to be consecrated in Gaul because of the lack of what he considered to be validly consecrated bishops in England at that time. During Wilfrid's absence Alhfrith seems to have led an unsuccessful revolt against his father, Oswiu

Oswiu of Northumbria

Oswiu , also known as Oswy or Oswig , was a King of Bernicia. His father, Æthelfrith of Bernicia, was killed in battle, fighting against Rædwald, King of the East Angles and Edwin of Deira at the River Idle in 616...

, leaving a question mark over Wilfrid's appointment as bishop. Before Wilfrid's return Oswiu had appointed Ceadda in his place, resulting in Wilfrid's retirement to Ripon for a few years following his arrival back in Northumbria.

After becoming Archbishop of Canterbury

Archbishop of Canterbury

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. In his role as head of the Anglican Communion, the archbishop leads the third largest group...

in 668, Theodore of Tarsus

Theodore of Tarsus

Theodore was the eighth Archbishop of Canterbury, best known for his reform of the English Church and establishment of a school in Canterbury....

resolved the situation by deposing Ceadda and restoring Wilfrid as the Bishop of Northumbria. For the next nine years Wilfrid discharged his episcopal duties, founded monasteries, built churches, and improved the liturgy

Liturgy

Liturgy is either the customary public worship done by a specific religious group, according to its particular traditions or a more precise term that distinguishes between those religious groups who believe their ritual requires the "people" to do the "work" of responding to the priest, and those...

. However his diocese

Diocese

A diocese is the district or see under the supervision of a bishop. It is divided into parishes.An archdiocese is more significant than a diocese. An archdiocese is presided over by an archbishop whose see may have or had importance due to size or historical significance...

was very large, and Theodore wished to reform the English Church, a process which included breaking up some of the larger dioceses into smaller ones. When Wilfrid quarrelled with Ecgfrith, the Northumbrian king, Theodore took the opportunity to implement his reforms despite Wilfrid's objections. After Ecgfrith expelled him from York, Wilfrid travelled to Rome to appeal to the papacy. Pope Agatho

Pope Agatho

-Background and early life:Little is known of Agatho before his papacy. A letter written by St. Gregory the Great to the abbot of St. Hermes in Palermo mentions an Agatho, a Greek born in Sicily to wealthy parents. He wished to give away his inheritance and join a monastery, and in this letter...

ruled in Wilfrid's favour, but Ecgfrith refused to honour the papal decree and instead imprisoned Wilfrid on his return to Northumbria before exiling him.

Wilfrid spent the next few years in Selsey

Selsey

Selsey is a seaside town and civil parish, about seven miles south of Chichester, in the Chichester District of West Sussex, England. Selsey lies at the southernmost point of the Manhood Peninsula, almost cut off from mainland Sussex by the sea...

, where he founded an episcopal see

Episcopal See

An episcopal see is, in the original sense, the official seat of a bishop. This seat, which is also referred to as the bishop's cathedra, is placed in the bishop's principal church, which is therefore called the bishop's cathedral...

and converted the pagan inhabitants of the Kingdom of Sussex

Kingdom of Sussex

The Kingdom of Sussex or Kingdom of the South Saxons was a Saxon colony and later independent kingdom of the Saxons, on the south coast of England. Its boundaries coincided in general with those of the earlier kingdom of the Regnenses and the later county of Sussex. A large part of its territory...

to Christianity. Theodore and Wilfrid settled their differences, and Theodore urged the new Northumbrian king, Aldfrith

Aldfrith of Northumbria

Aldfrith sometimes Aldfrid, Aldfridus , or Flann Fína mac Ossu , was king of Northumbria from 685 until his death. He is described by early writers such as Bede, Alcuin and Stephen of Ripon as a man of great learning, and some of his works, as well as letters written to him, survive...

, to allow Wilfrid's return. Aldfrith agreed to do so, but in 691 he expelled Wilfrid again. Wilfrid went to Mercia, where he helped missionaries and acted as bishop for the Mercian king. Wilfrid appealed to the papacy about his expulsion in 700, and the pope ordered that an English council should be held to decide the issue. This council, held at Austerfield

Austerfield

Austerfield is a village and civil parish in the Metropolitan Borough of Doncaster , on the border with Nottinghamshire. It lies to the north-east of Bawtry on the A614 road to Finningley, and is located at 53° 26' 30" North, 1° 0' West, at an elevation of around 7 metres above sea level...

in 702, attempted to confiscate all of Wilfrid's possessions, and so Wilfrid travelled to Rome to appeal against the decision. His opponents in Northumbria excommunicated him, but the papacy upheld Wilfrid's side, and he regained possession of Ripon and Hexham, his Northumbrian monasteries. Wilfrid died in 709 or 710. After his death, he was venerated as a saint.

Historians then and now have been divided over Wilfrid. His followers commissioned Stephen of Ripon to write a Vita Sancti Wilfrithi

Vita Sancti Wilfrithi

The Vita Sancti Wilfrithi or Life of St Wilfrid is an early 8th-century hagiographic text recounting the life of the Northumbrian bishop, Wilfrid. Although a hagiography, it has few miracles, while its main concerns are with the politics of the Northumbrian church and the history of the...

(or Life of Wilfrid) shortly after his death, and the medieval historian Bede

Bede

Bede , also referred to as Saint Bede or the Venerable Bede , was a monk at the Northumbrian monastery of Saint Peter at Monkwearmouth, today part of Sunderland, England, and of its companion monastery, Saint Paul's, in modern Jarrow , both in the Kingdom of Northumbria...

also wrote extensively about him. Wilfrid lived ostentatiously, and travelled with a large retinue. He ruled a large number of monasteries, and claimed to be the first Englishman to introduce the Rule of Saint Benedict into English monasteries. Some modern historians see him mainly as a champion of Roman customs against the customs of the British and Irish churches

Celtic Christianity

Celtic Christianity or Insular Christianity refers broadly to certain features of Christianity that were common, or held to be common, across the Celtic-speaking world during the Early Middle Ages...

, others as an advocate for monasticism

Monasticism

Monasticism is a religious way of life characterized by the practice of renouncing worldly pursuits to fully devote one's self to spiritual work...

.

Background

During Wilfrid's lifetime the British Isles consisted of a number of small kingdoms. Traditionally the English people

English people

The English are a nation and ethnic group native to England, who speak English. The English identity is of early mediaeval origin, when they were known in Old English as the Anglecynn. England is now a country of the United Kingdom, and the majority of English people in England are British Citizens...

were thought to have been divided into seven kingdoms, but modern historiography has shown that this is a simplification of a much more confused situation. A late 7th-century source, the Tribal Hidage

Tribal Hidage

Image:Tribal Hidage 2.svg|thumb|400px|alt=insert description of map here|The tribes of the Tribal Hidage. Where an appropriate article exists, it can be found by clicking on the name.rect 275 75 375 100 Elmetrect 375 100 450 150 Hatfield Chase...

, lists the peoples south of the Humber river; among the largest groups of peoples are the West Saxons (later Wessex

Wessex

The Kingdom of Wessex or Kingdom of the West Saxons was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the West Saxons, in South West England, from the 6th century, until the emergence of a united English state in the 10th century, under the Wessex dynasty. It was to be an earldom after Canute the Great's conquest...

), the East Angles

Kingdom of the East Angles

The Kingdom of East Anglia, also known as the Kingdom of the East Angles , was a small independent Anglo-Saxon kingdom that comprised what are now the English counties of Norfolk and Suffolk and perhaps the eastern part of the Fens...

and Mercia

Mercia

Mercia was one of the kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy. It was centred on the valley of the River Trent and its tributaries in the region now known as the English Midlands...

ns (later the Kingdom of Mercia), and the Kingdom of Kent

Kingdom of Kent

The Kingdom of Kent was a Jutish colony and later independent kingdom in what is now south east England. It was founded at an unknown date in the 5th century by Jutes, members of a Germanic people from continental Europe, some of whom settled in Britain after the withdrawal of the Romans...

. Smaller groups who at that time had their own royalty but were later were absorbed into larger kingdoms include the peoples of Magonsæte, Lindsey, Hwicce

Hwicce

The Hwicce were one of the peoples of Anglo-Saxon England. The exact boundaries of their kingdom are uncertain, though it is likely that they coincided with those of the old Diocese of Worcester, founded in 679–80, the early bishops of which bore the title Episcopus Hwicciorum...

, the East Saxons

Kingdom of Essex

The Kingdom of Essex or Kingdom of the East Saxons was one of the seven traditional kingdoms of the so-called Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy. It was founded in the 6th century and covered the territory later occupied by the counties of Essex, Hertfordshire, Middlesex and Kent. Kings of Essex were...

, the South Saxons, the Isle of Wight, and the Middle Angles

Middle Angles

The Middle Angles were an important ethnic or cultural group within the larger kingdom of Mercia in England in the Anglo-Saxon period.-Origins and territory:...

. Other even smaller groups had their own rulers, but their size means that they do not often appear in the histories. There were also native Britons in the west, in modern-day Wales

Wales

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and the island of Great Britain, bordered by England to its east and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population of three million, and a total area of 20,779 km²...

and Cornwall

Cornwall

Cornwall is a unitary authority and ceremonial county of England, within the United Kingdom. It is bordered to the north and west by the Celtic Sea, to the south by the English Channel, and to the east by the county of Devon, over the River Tamar. Cornwall has a population of , and covers an area of...

, who formed kingdoms including those of Dumnonia

Dumnonia

Dumnonia is the Latinised name for the Brythonic kingdom in sub-Roman Britain between the late 4th and late 8th centuries, located in the farther parts of the south-west peninsula of Great Britain...

, Dyfed

Kingdom of Dyfed

The Kingdom of Dyfed is one of several Welsh petty kingdoms that emerged in 5th-century post-Roman Britain in south-west Wales, based on the former Irish tribal lands of the Déisi from c 350 until it was subsumed into Deheubarth in 920. In Latin, the country of the Déisi was Demetae, eventually to...

, and Gwynedd

Kingdom of Gwynedd

Gwynedd was one petty kingdom of several Welsh successor states which emerged in 5th-century post-Roman Britain in the Early Middle Ages, and later evolved into a principality during the High Middle Ages. It was based on the former Brythonic tribal lands of the Ordovices, Gangani, and the...

.

Between the Humber and Forth

Firth of Forth

The Firth of Forth is the estuary or firth of Scotland's River Forth, where it flows into the North Sea, between Fife to the north, and West Lothian, the City of Edinburgh and East Lothian to the south...

the English had formed into two main kingdoms, Deira

Deira

Deira was a kingdom in Northern England during the 6th century AD. Itextended from the Humber to the Tees, and from the sea to the western edge of the Vale of York...

and Bernicia, often united as the Kingdom of Northumbria. A number of Celtic kingdoms also existed in this region, including Craven

Craven

Craven is a local government district in North Yorkshire, England that came into being in 1974, centred on the market town of Skipton. In the changes to British local government of that year this district was formed as the merger of Skipton urban district, Settle Rural District and most of Skipton...

, Elmet

Elmet

Elmet was an independent Brythonic kingdom covering a broad area of what later became the West Riding of Yorkshire during the Early Middle Ages, between approximately the 5th century and early 7th century. Although its precise boundaries are unclear, it appears to have been bordered by the River...

, Rheged

Rheged

Rheged is described in poetic sources as one of the kingdoms of the Hen Ogledd , the Brythonic-speaking region of what is now northern England and southern Scotland, during the Early Middle Ages...

, and Gododdin

Gododdin

The Gododdin were a Brittonic people of north-eastern Britain in the sub-Roman period, the area known as the Hen Ogledd or Old North...

. A native British kingdom, later called the Kingdom of Strathclyde

Kingdom of Strathclyde

Strathclyde , originally Brythonic Ystrad Clud, was one of the early medieval kingdoms of the celtic people called the Britons in the Hen Ogledd, the Brythonic-speaking parts of what is now southern Scotland and northern England. The kingdom developed during the post-Roman period...

, survived as an independent power into the 10th century in the area which became modern-day Dunbartonshire

Dunbartonshire

Dunbartonshire or the County of Dumbarton is a lieutenancy area and registration county in the west central Lowlands of Scotland lying to the north of the River Clyde. Until 1975 it was a county used as a primary unit of local government with its county town and administrative centre at the town...

and Clydesdale

Clydesdale

Clydesdale was formerly one of nineteen local government districts in the Strathclyde region of Scotland.The district was formed by the Local Government Act 1973 from part of the former county of Lanarkshire: namely the burghs of Biggar and Lanark and the First, Second and Third Districts...

. To the north-west of Strathclyde lay the Gaelic kingdom of Dál Riata

Dál Riata

Dál Riata was a Gaelic overkingdom on the western coast of Scotland with some territory on the northeast coast of Ireland...

, and to the north-east a small number of Pictish kingdoms. Further north still lay the great Pictish kingdom of Fortriu

Fortriu

Fortriu or the Kingdom of Fortriu is the name given by historians for an ancient Pictish kingdom, and often used synonymously with Pictland in general...

, which after the Battle of Dun Nechtain in 685 came to be the strongest power in the northern half of Britain. The Irish had always had contacts with the rest of the British Isles, and during the early 6th century they immigrated from the island of Ireland to form the kingdom of Dál Riata, although exactly how much conquest took place is a matter of dispute with historians. It also appears likely that the Irish settled in parts of Wales, and even after the period of Irish settlement, Irish missionaries were active in Britain.

Christianity had only recently arrived in some of these kingdoms. Some had been converted by the Gregorian mission

Gregorian mission

The Gregorian mission, sometimes known as the Augustinian mission, was the missionary endeavour sent by Pope Gregory the Great to the Anglo-Saxons in 596 AD. Headed by Augustine of Canterbury, its goal was to convert the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity. By the death of the last missionary in 653, they...

, a group of Roman missionaries who arrived in Kent in 597 and who mainly influenced southern Britain. Others had been converted by the Hiberno-Scottish mission, chiefly Irish missionaries working in Northumbria and neighbouring kingdoms. A few kingdoms, such as Dál Riata, became Christian but how they did so is unknown. The native Picts, according to the medieval writer Bede, were converted in two stages, initially by native Britons under Ninian

Saint Ninian

Saint Ninian is a Christian saint first mentioned in the 8th century as being an early missionary among the Pictish peoples of what is now Scotland...

, and subsequently by Irish missionaries.

Sources

The main sources for knowledge of Wilfrid are the medieval Vita Sancti Wilfrithi, written by Stephen of Ripon soon after Wilfrid's death, and the works of the medieval historian Bede, who knew Wilfrid during the bishop's lifetime. Stephen's Vita is a hagiography, intended to show Wilfrid as a saintly man, and to buttress claims that he was a saint. The Vita is selective in its coverage, and gives short shrift to Wilfrid's activities outside of Northumbria. Two-thirds of the work deals with Wilfrid's attempts to return to Northumbria, and is a defence and vindication of his Northumbrian career. Stephen's work is flattering and highly favourable to Wilfrid, making its use as a source problematic; despite its shortcomings however, the Vita is the main source of information on Wilfrid's life. It views the events in Northumbria in the light of Wilfrid's reputation and from his point of view, and is highly partisan. Another concern is that hagiographies were usually full of conventional material, often repeated from earlier saints' lives, as was the case with Stephen's work. It appears that the Vita Sancti Wilfrithi was not well known in the Middle Ages, as only two manuscripts of the work survive.Bede also covers Wilfrid's life in his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum

Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum

The Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum is a work in Latin by Bede on the history of the Christian Churches in England, and of England generally; its main focus is on the conflict between Roman and Celtic Christianity.It is considered to be one of the most important original references on...

, but this account is more measured and restrained than the Vita. In the Historia, Bede used Stephen's Vita as a source, reworking the information and adding new material when possible. Other, more minor, sources for Wilfrid's life include a mention of Wilfrid in one of Bede's letters. A poetical Vita Sancti Wilfrithi by Frithegod

Frithegod

Freithegod, sometimes Frithegode or Fredegaud was a poet and clergyman in the middle 10th-century who served Oda of Canterbury, an Archbishop of Canterbury....

written in the 10th century is essentially a rewrite of Stephen's Vita, produced in celebration of the movement of Wilfrid's relic

Relic

In religion, a relic is a part of the body of a saint or a venerated person, or else another type of ancient religious object, carefully preserved for purposes of veneration or as a tangible memorial...

s to Canterbury. Wilfrid is also mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a collection of annals in Old English chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the Chronicle was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of Alfred the Great...

, but as the Chronicle was probably a 9th-century compilation, the material on Wilfrid may ultimately have derived either from Stephen's Vita or from Bede. Another, later, source is the Vita Sancti Wilfrithi written by Eadmer

Eadmer

Eadmer, or Edmer , was an English historian, theologian, and ecclesiastic. He is known for being a contemporary biographer of his contemporary archbishop and companion, Saint Anselm, in his Vita Anselmi, and for his Historia novorum in Anglia, which presents the public face of Anselm...

, a 12th-century Anglo-Norman writer and monk from Canterbury. This source is higly influenced by the contemporary concerns of its writer, but does attempt to provide some new material besides reworking Bede.

Many historians, including the editor of Bede's works, Charles Plummer

Charles Plummer

Charles Plummer was an English historian, best known for editing Sir John Fortescue's The Governance of England, and for coining the term 'bastard feudalism'....

, have seen in Bede's writings a dislike of Wilfrid. The historian Walter Goffart goes further, suggesting that Bede wrote his Historia as a reaction to Stephen's Vita Sancti Wilfrithi, and that Stephen's work was written as part of a propaganda campaign to defend a "Wilfridian" party in Northumbrian politics. Some historians, including James Fraser, find that a credible view, but others such as Nick Higham are less convinced of Bede's hostility to Wilfrid.

Childhood and early education

Wilfrid was born in Northumbria in about 633. James Fraser argues that Wilfrid's family were aristocrats from Deira, pointing out that most of Wilfrid's early contacts were from that area. A conflict with his stepmother when he was about 14 years old drove Wilfrid to leave home, probably without his father's consent. Wilfrid's background is never explicitly described as noble, but the king's retainers were frequent guests at his father's house, and on leaving home Wilfrid equipped his party with horses and clothes fit for a royal court.Queen Eanflæd became Wilfrid's patroness following his arrival at the court of her husband, King Oswiu. She sent him to study under Cudda, formerly one of her husband's retainers, but by that time in about 648 a monk on the island of Lindisfarne. The monastery on the island had recently been founded by Aidan

Aidan of Lindisfarne

Known as Saint Aidan of Lindisfarne, Aidan the Apostle of Northumbria , was the founder and first bishop of the monastery on the island of Lindisfarne in England. A Christian missionary, he is credited with restoring Christianity to Northumbria. Aidan is the Anglicised form of the original Old...

, who had been instrumental in converting Northumbria to Christianity. At Lindisfarne Wilfrid is said to have "learned the whole Psalter

Psalter

A psalter is a volume containing the Book of Psalms, often with other devotional material bound in as well, such as a liturgical calendar and litany of the Saints. Until the later medieval emergence of the book of hours, psalters were the books most widely owned by wealthy lay persons and were...

by heart and several books". Wilfrid studied at Lindisfarne for a few years before going to the Kentish king's court at Canterbury

Canterbury

Canterbury is a historic English cathedral city, which lies at the heart of the City of Canterbury, a district of Kent in South East England. It lies on the River Stour....

in 652, where he stayed with relatives of Queen Eanflæd. The queen had given Wilfrid a letter of introduction to pass to her cousin, King Eorcenberht

Eorcenberht of Kent

Eorcenberht of Kent was king of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Kent from 640 until his death, succeeding his father Eadbald....

, in order to ensure that Wilfrid was received by the king. While in Kent, Wilfrid's career was advanced by Eanflæd's cousin Hlothere

Hlothhere of Kent

Hlothhere was a King of Kent who ruled from 673 to 685.He succeeded his brother Ecgberht I in 673. He must have come into conflict with Mercia, since in 676 the Mercian king Æthelred invaded Kent and caused great destruction; according to Bede, even churches and monasteries were not spared, and...

, who was later the King of Kent from 673 to 685. The Kentish court included a number of visiting clergymen at that time, including Benedict Biscop

Benedict Biscop

Benedict Biscop , also known as Biscop Baducing, was an Anglo-Saxon abbot and founder of Monkwearmouth-Jarrow Priory and was considered a saint after his death.-Early career:...

, a noted missionary. Wilfrid appears to have spent about a year in Kent, but the exact chronology is uncertain.

Time at Rome and Lyon

Lyon

Lyon , is a city in east-central France in the Rhône-Alpes region, situated between Paris and Marseille. Lyon is located at from Paris, from Marseille, from Geneva, from Turin, and from Barcelona. The residents of the city are called Lyonnais....

, where Wilfrid stayed under the patronage of Annemund

Annemund

Saint Annemund, also known as Annemundus, Aunemundus and Chamond, was Archbishop of Lyon. His father, Sigon, was a prefect in Lyon, while his brother, Dalfin, was Count of Lyons....

, the archbishop. Stephen says that Annemund wanted to marry Wilfrid to the archbishop's niece, and to make Wilfrid the governor of a Frankish province, but that Wilfrid refused and continued on his journey to Rome. There he learned the Roman method of calculating the date of Easter

Computus

Computus is the calculation of the date of Easter in the Christian calendar. The name has been used for this procedure since the early Middle Ages, as it was one of the most important computations of the age....

, and studied the Roman practice of relic collecting. After an audience with the pope, Wilfrid returned to Lyon.

Stephen of Ripon says that Wilfrid stayed in Lyon for three years, leaving only after the archbishop's murder. However, Annemund's murder took place in 660 and Wilfrid returned to England in 658, suggesting that Stephen's chronology is awry. Stephen says that Annemund gave Wilfrid a clerical tonsure

Tonsure

Tonsure is the traditional practice of Christian churches of cutting or shaving the hair from the scalp of clerics, monastics, and, in the Eastern Orthodox Church, all baptized members...

, although this does not appear to mean that he became a monk, merely that he entered the clergy. Bede is silent on the subject of Wilfrid's monastic status, although Wilfrid probably became a monk during his time in Rome, or afterwards while he was in Gaul. Some historians, however, believe that Wilfrid was never a monk. While in Gaul, Wilfrid absorbed Frankish ecclesiastical practices, including some aspects from the monasteries founded by Columbanus

Columbanus

Columbanus was an Irish missionary notable for founding a number of monasteries on the European continent from around 590 in the Frankish and Lombard kingdoms, most notably Luxeuil and Bobbio , and stands as an exemplar of Irish missionary activity in early medieval Europe.He spread among the...

. This influence may be seen in Wilfrid's probable adoption of a Frankish ceremony in his consecration of churches later in his life, as well as in his employment of Frankish masons to build his churches. Wilfrid would also have learned of the Rule of Saint Benedict in Gaul, as Columbanus' monasteries followed that monastic rule.

Abbot of Ripon

After Wilfrid's return to Northumbria in about 658, CenwalhCenwalh of Wessex

Cenwalh, also Cenwealh or Coenwalh, was King of Wessex from c. 643 to c. 645 and from c. 648 unto his death, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, in c. 672.-Penda and Anna:...

, King of Wessex, recommended Wilfrid to Alhfrith, Oswiu's son, as a cleric well-versed in Roman customs and liturgy. Alhfrith was a sub-king of Deiria under his father's rule, and the most likely heir to his father's throne as his half-brothers were still young. Shortly before 664 Alhfrith gave Wilfrid a monastery he had recently founded at Ripon, formed around a group of monks from Melrose Abbey

Melrose Abbey

Melrose Abbey is a Gothic-style abbey in Melrose, Scotland. It was founded in 1136 by Cistercian monks, on the request of King David I of Scotland. It was headed by the Abbot or Commendator of Melrose. Today the abbey is maintained by Historic Scotland...

, followers of the Irish monastic customs

Hiberno-Scottish mission

The Hiberno-Scottish mission was a mission led by Irish and Scottish monks which spread Christianity and established monasteries in Great Britain and continental Europe during the Middle Ages...

. Wilfrid ejected the abbot, Eata, because he would not follow the Roman customs; Cuthbert, later a saint, was another of the monks expelled. Wilfrid introduced the Rule of Saint Benedict into Ripon, claiming that he was the first person in England to make a monastery follow it, but this claim rests on the Vita Sancti Wilfrithi and does not say where Wilfrid became knowledgeable about the Rule, nor exactly what form of the Rule was being referred to. Shortly afterwards Wilfrid was ordained a priest by Agilbert

Agilbert

Agilbert was the second Bishop of the West Saxon kingdom and later Bishop of Paris. Son of a Neustrian noble named Betto, he was a first cousin of Audoin and related to the Faronids and Agilolfings, and less certainly to the Merovingians...

, Bishop of Dorchester in the kingdom of the Gewisse, part of Wessex. Wilfrid was a protege of Agilbert, who later helped in Wilfrid's consecration as a bishop. The monk Ceolfrith was attracted to Ripon from Gilling Abbey

Gilling Abbey

Gilling Abbey was a medieval Anglo-Saxon monastery established in Yorkshire.It was founded at Gilling in what is currently Yorkshire by Queen Eanflæd, the wife of King Oswiu of Northumbria, who persuaded her husband to found it at the site where Oswiu had killed a rival and kinsman, King Oswine of...

, which had recently been depopulated as a result of the plague. Ceolfrith later became Abbot of Wearmouth-Jarrow during the time the medieval chronicler and writer Bede was a monk there. Bede hardly mentions the relationship between Ceolfrith and Wilfrid, but it was Wilfrid who consecrated Ceolfrith a priest and who gave permission for him to transfer to Wearmouth-Jarrow.

Background

The Roman churches and those in the British Isles (often called "Celtic churches") used different methods to calculate the date of Easter. The church in Northumbria had traditionally used the former calculation, and that was the date observed by King Oswiu. His wife Eanflæd and a son, Alhfrith, celebrated Easter on the Roman date however, which meant that while one part of the royal court was still observing the Lenten fastLent

In the Christian tradition, Lent is the period of the liturgical year from Ash Wednesday to Easter. The traditional purpose of Lent is the preparation of the believer – through prayer, repentance, almsgiving and self-denial – for the annual commemoration during Holy Week of the Death and...